Abstract

The preservation of packaged food against oxidative degradation is essential to establish and improve food shelf life, customer acceptability, and increase food security. Oxygen absorbers have an important role in the removal of dissolved oxygen, preserving the colour, texture and aroma of different food products, and importantly inhibition of food spoilage microbes. Active packaging technology in food preservation has improved over decades mostly due to the sealing of foods in oxygen impermeable package material and the quality of oxygen absorber. Ferrous iron oxides are the most reliable and commonly used oxygen absorbers within the food industry. Oxygen absorbers have been transformed from sachets of dried iron-powder to simple self-adhesive patches to accommodate any custom size, capacity and application. Oxygen concentration can be effectively lowered to 100 ppm, with applications spanning a wide range of food products and beverages across the world (i.e. bread, meat, fish, fruit, and cheese). Newer molecules that preserve packaged food materials from all forms of degradation are being developed, however oxygen absorbers remain a staple product for the preservation of food and pharmaceutical products to reduce food wastage in developed nations and increased food security in the developing & third world.

Keywords: Food packaging, Food preservation, Oxidation-reduction, Food industry, Food and beverages

Introduction

Food preservation is an essential science since time immemorial. Salting and drying of foods were used as techniques in the past that persist until today. However some foods are served fresh without the use of harmful and unwanted food preservatives. Ironically, oxygen is required for the survival of most of the organisms i.e. oxidative phosphorylation, but also the growth of microbes which contributes to the spoilage of preserved food and beverages. Thus, the oxygen level is integral in influencing the quality of the stored food product. Other components such as anaerobic microbial growth, variations in moisture levels, light, enzymatic activity and non-oxidative reactions, individually or collectively can deteriorate packaged food-products (Brody et al. 2001).

The various effects of oxygen on preserved foods and beverages includes rancidity of unsaturated fats (i.e. ‘off-flavours’ and toxic end-products), darkening of fresh meat pigments by promoting the growth of aerobic bacteria and fungi, stale odour of soft bakery foods and phenolic browning of fruit/vegetables. Moreover, the deterioration of flavour of beer, loss of vitamin C (ascorbic acid) and acceleration of respiration in fruit and vegetable based foods, with the loss of aroma of beverages (coffee and tea) through oxidation of aroma oils and discoloration of processed foods such as fresh meat, fruit and vegetables has a strong influence on consumer purchasing in the retail food industry. Economic loss due to spoiled food is enormous (Brody et al. 2001) and often a hidden cost of production, estimated at 1.3 billion tons per year in a study conducted for the FAO (van Otterdijk and Meybeck 2011). Further, aerobic bacterial and fungal growth are unwanted in most food products such as breads, with Rhizopus stolonifer, and Mucor spp. being common fungal species, and Bacillus subtilis a common bacteria causing bread spoilage (Saranraj and Geetha 2012). Thus technological packaging solutions are warranted for the determent of microbial growth and also rancidity of food products without using preservatives.

The shelf life of packaged foods under chilled or ambient temperatures can be improved with the food product itself being processed, preservatives added or other auxiliary agents used to stabilize against biochemical, microbiological, and enzymatic activity. The protection against enzymes or microorganisms which can deteriorate or infect respectively, is usually achieved by hermetic sealing in a modified atmospheric packaging (MAP), that usually consists of a high gas-barrier structure that is hermetically closed (i.e. low oxygen transmission rate – OTR); and thus low oxygen environment. However, residual oxygen is inherent in packed environment, i.e. void-space between food particles and headspace in packaging, and the dissolved and occluded air within food, which may hamper the use of gas flushing or vacuum sealing to create a low oxygen concentration after packaging. Removal of void-space (space not occupied by food particles) and the dissolved oxygen in food is crucial to provide extended shelf-life of various foods and beverages that may otherwise become deteriorated chiefly through enzymatic, microbiological and biochemical mechanisms (Mexis et al. 2012). Further, an internal system is required to continually absorb the oxygen that passes through a ‘high oxygen barrier’ such as polymers like PVdC (Polyvinylidene chloride) 10 μm on PET (Polyethylene terephthalate) 60 μm, which commonly displays a combined OTR of 12–18 cc O2/m2/per 24 h at 25 °C.

To overcome the loss due to adverse effects of oxygen on packaged foods, a variety of materials can be used to absorb residual oxygen in the packaging or the oxygen that transmits through the packaging itself. As mentioned, oxygen radicals (i.e. peroxide radicals or singlet oxygen) can react with lipids, whereas anti-oxidants are compounds that nullify the effects of oxygen radicals. Anti-oxidants include β carotene, butylated hydroxyanisole, tocopherols, and ascorbic acid can be added to the food mixture to nullify the effects of oxygen degradation on food molecules such as lipids. However, they cannot absorb the oxygen in the void-space of the packaging or between food particles (Brody et al. 2001). Oxygen interceptors are compounds found in both the food product and package materials that prevent oxygen from reaching the food product by auto-oxidation. Oxygen absorbers/or Oxygen scavengers (interchangeable name herein used) are materials usually contained within a satchel that is added to MAP to remove the oxygen from void space around the food particles. They react with oxygen and moisture; via oxidation of a salt such as iron carbonate (Brody et al. 2001). The present review focuses on characteristics and applications of oxygen absorbers/scavengers in the food industry.

History of oxygen absorbers/scavengers

Earlier in the 20th century, a number of chemicals were incorporated into food products to absorb residual oxygen, including ascorbic acid and glucose oxidase/catalase (Brody et al. 2001). During the 1960s dithionite, calcium hydroxide, activated carbon, and water were incorporated into a system and used in Japan for oxygen scavenging properties which was also patented (Bloch 1965). By the 1970s, the use of plastic packaging varying in oxygen permeability started to be widely used. Concerns regarding the oxidation by residual oxygen and also the oxygen which transmits through the packaging material lead to the development of chemical means of oxygen removal by using packets or sachets within the package, which saw the beginnings of new category of packaging called active packaging, including oxygen absorbers.

In 1977, the Ageless® oxygen absorber was launched by the Mitsubishi Gas Company (Mitsubishi 2009), which consisted of reduced iron salts, activated by moisture placed in sealed gas-barrier food packages where the iron oxidised to a ferric state. These reduced iron-containing sachets were used with active-packaging oxygen scavenging technology to help preserve contained foods in larger packages. With the success of this packaging, the Toppan Printing Company from Japan introduced ascorbic acid–based oxygen scavenger systems. This success led to more commercial production of oxygen scavenger brands in Japan (>10), USA (2) and Taiwan. Oxygen absorbers can lower the internal oxygen concentration to <0.0001 % when the scavenging chemical material and high barrier packaging are employed (Brody et al. 2001).

Further, Australia’s CSIRO developed a sachet-free technology of polymer films that contained a photosensitizing dye and a singlet-oxygen acceptor, which is activated upon illumination. Oxygen is continuously scavenged as a function of lux intensity and available acceptor material (Rooney 1982, 1984). During the 1990s, developments undertaken by Toyo Seikan Kaisha, Ltd (Oxyguard® using ferrous oxygen scavenger) (Abe 1990), W. R. Grace and Company (Daraform® 6490 using ascorbic acid and Cryovac® OS1000 using unsaturated hydrocarbons in plastic films), Multisorb Technologies Inc., (FreshMax® using a large adhesive label) (Idol 1991, 1993a, b) have influenced the market of oxygen scavengers with current oxygen absorbers such as OxySorb™ by Wholesale Group International Pty. Ltd (Australia) (Wholesale Group International 2013).

Types of oxygen absorbers

A variety of oxygen scavenging systems and related systems are available that can be used to match the requirement of different package-foods (Table 1) adapted from (Brody et al. 2001).

Table 1.

Types of commercially available oxygen absorbers

| Satchel system | Compounds | Activators | Indicated application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidants | t-butyl hydroquinone, butylated hydroxytoluene | Deep-fried noodles | |

| Sulfites | Sulfites and analogues | Adjunct palletized powders and Promoter metals i.e. chromium, lead, tin, palladium, cobalt, nickel, and platinum | Foods containing oils/fats, fresh foods, and pharmaceuticals |

| Boron | Boron/Boric acid | Alkaline substances (i.e. NaCO3 −) carrier (activated carbon and diatomaceous earth) | Rice |

| Sugar alcohols and glycols | Sugar alcohols (xylitol, sorbitol, mannitol) 1,2-glycols (propylene or ethylene glycol) | Transition metal (nickel halides and sulfates/cobalt/iron) or alkaline substances or phenolic compounds (catechol/tannic acid) or a quinone (benzoquinone) | Rice (brown), cakes |

| Unsaturated fatty acids and hydrocarbons | Unsaturated fatty acids (linseed oil) and hydrocarbons (isoprene, butadiene, and squalene) | Catalysts and carriers of iron and cobalt | All types of packaged food |

| Palladium catalysts | Palladium catalyst/hydrogen gas | All types of packaged food | |

| Enzymes | Glucose oxidase | All types of packaged food | |

| Yeast | Immobilized yeast | Beverages: beer | |

| Package material | Any metal reactive with oxygen (Fe/Zn/Mn) or plastic film with thin metallic layer | All types of packaged food | |

| Ascorbic acid based scavengers | Vitamin C | Fruits and fresh vegetables | |

| Ferrous iron based oxygen absorbers/scavengers | Ferrous iron oxide | All types of dry packaged food |

Abbreviations: NaCO 3 sodium bicarbonate, Fe iron, Zn zinc, Mn manganese

Chemical, physical properties, toxicity

The ferrous iron based oxygen scavengers are most widely used in the preservation of packaged foods. The scavenger molecule, ferrous iron powder along with activated carbon and salt is available as small, highly oxygen-permeable sachets that can be packed separately from the food product. The packaging of the absorber usually consists of paper and polyethylene. Oxygen scavengers are completely safe to use, are not edible (choking hazard) and non-toxic. No harmful gases are released during oxygen absorption. A new (ready to use) sachet appears black, its powder is loose with a warm feeling from the exterior indicating oxygen absorbing activity, whereas an old or expired product can be distinguished from its red rusty colour, particulate nature and is harder to feel from the exterior (Cichello 2010).

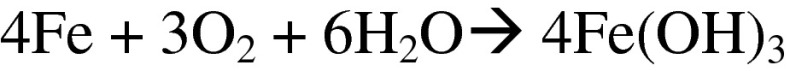

The basic compound of ferrous iron oxide (Iron II Oxide; FeO) becomes activated with moisture from the environment and automatically commences absorbing the residual oxygen within the headspace of package becomes hydrated with atmospheric moisture to oxidize to a ferric state; hydrated iron (III) oxide (ferric oxide; Fe2O3). Under ideal conditions, approximately 2.2 g of ferrous carbonate is used to absorb 100 cc of oxygen. The chemical reaction of the ferrous based oxygen absorber is shown below in Fig. 1 and is identical to the rusting process.

Fig. 1.

Chemical reaction of ferrous based oxygen absorber (rusting process)

Further, the LD50 for ferrous iron has been determined as 16 g/kg body weight, and thus a standard oxygen absorber of 100 cc, weighs 2.5 g (Brody et al. 2001). The average human weighing 70 kg would have to eat 448 × 100 cc oxygen absorbers before the LD50 for toxicity is reached. For instance the printing inks used in the packaging material of the OxySorb™ brand, use non-toxic contents, food edible soy based products, rendering the total oxygen absorber safe to come into contact with food items, even though it should not be eaten as it presents a choking hazard. The contents can be added to the garden by the consumer to provide carbon and iron nutrient supply for plants when evenly spread, with the PE and paper portion completely recyclable.

Applications of oxygen absorbers

To obtain the maximum removal of oxygen from the inner packaging environment, it is essential to understand the appropriate usage of oxygen absorbers. For food products packaged in high barrier packaging and under hermetic seals the recommended initial oxygen level in the headspace is calculated and also the oxygen between food particles and absorbed onto and absorbed into the food. The dissolved oxygen in food, void space and also oxygen that can permeate through the film must all be considered in determining the amount of ferrous iron to be used in the oxygen absorber. This will then determine the correct sized oxygen absorber to be used. As 20.9 % of atmospheric air is oxygen, and there is 478 ml (cc) of headspace ‘void’, and estimated residual oxygen between the food particles, then approximately 100 cc oxygen absorber would be recommended. In addition, as mentioned, the potential oxygen transmission must also be calculated, and adsorbed oxygen on food particles, which is normally calculated by expert consultants in their field and thus a larger oxygen absorber would be required as a function of dissolved oxygen, shelf-life, and packaging film transmission rate. In the following section the implementation of oxygen absorbers in various food products will be discussed.

Bread and biscuits products

The implementation of oxygen absorbers extends to a wide variety of food types including bread, cakes and cereal. In a study of military ration crackers over 52 weeks, the implementation of oxygen absorbers at various storage temperatures (i.e. 15, 25 and 35 °C) reduced lipid oxidation (i.e. hexanal generation) and the development of oxidative rancid odours, which were strongly correlated (Berenzon and Saguyf 1998). Moreover, in more moist (higher available water Aw) cereal based foods, oxygen absorbers have been shown to decrease spoilage organisms such as Penicillium commune, P. roqueforti. However Aspergillus flavus and Endomyces fibuliger persisted at oxygen levels of 0.03 %, with E. fibuliger further surviving anaerobically (facultative anaerobe) even with an oxygen absorber with high CO2 levels only suspending growth (Nielsen and Rios 2000). Instead oxygen absorbers were used in combination with essential oils and oleoresins from several herbs with concentration varying from 1 to 100 μl per Petri dish). The highest activity was shown with essential oils from mustard (Brassica spp.), cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.), garlic (Allium sativum), clove (Syzygium aromaticum) mostly attributed to allyl isothiocyanate at 3.5 μg/ml in gas phase (Nielsen and Rios 2000). Moreover, the use of an oxygen absorber that also emitted alcohol has been shown to be highly effective and a good alternative to chemical preservatives such as calcium propionate (282) or potassium sorbate (E202). When combined with an ethanol emitter, the oxygen absorber significantly decreased the growth of yeasts, moulds and Bacillus cereus, and inhibited lipid peroxidation and rancid odours for 30 days treatment (Latou et al. 2010). Moreover, oxygen absorbers reduced microorganism growth by 1–1.5 log (i.e. moulds and yeasts and Staphylococcus spp) in fresh lasagna pasta stored at 10 ± 2 °C, however coliforms were not altered (Cruz et al. 2006). Thus oxygen absorbers appear highly relevant for the preservative free preservation of cereal and bread products via inhibition of food spoilage bacteria and fungi.

Fruit and vegetables

Moreover, Charles et al. 2003, showed that implementation of oxygen absorbers in packaging with tomatoes extended shelf-life (Charles et al. 2003). They accounted for variables such as vegetable respiration rate, gas transmission rate of packaging such as OTR, and oxygen absorption kinetic of the absorber. Using a LDPE (Low-Density Polyethylene) in conjunction with an iron-based oxygen absorber, suppressed the CO2 peak and transient period characteristics due to rapid oxygen depletion. Further, oxygen absorbers have successfully impeded the oxidation of β-carotene in dried sweet potato flakes. Researchers used a high barrier polypropylene film and nylon laminate film; low oxygen permeability with vacuum sealed with an oxygen absorber. The use of oxygen absorbers with a high barrier, flexible oxygen barrier film provided the highest level of β-carotene retention over a 210 days trial period (Emenhiser et al. 1999). Moreover, the red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum (Herbst)) had a 100 % mortality rate) in 500 g packs of sultana raisins packed in metalized polyester polymer at 30 °C, 22.5 °C, and 15 °C for 9, 20 and 45 days respectively, and also fruit colour was maintained using an oxygen absorber and low storage temperature (15 °C) (Tarr and Clingeleffer 2005). In fruit and vegetable preservation, oxygen absorbers impede macroscopic organisms and also maintain the nutritional status of the food such as vitamin levels.

Nut products

Oxygen absorbers have been successfully implemented in roasted and ground soybeans to prevent lipid oxidation (Takenaga et al. 1987), improving walnuts storage and quality at 11 °C over a 13 month period, by reducing hexanal formation and rancidity of taste, by using a very low oxygen permeability packaging material such as laminate with EVOH (Ethylene vinyl alcohol) in addition to nitrogen flushing (Jensen et al. 2003). The use of oxygen absorbers with almond kernels (Prunus dulcis) provides a 12 month shelf life irrespective of container oxygen barrier:

polyethylene terephthalate//low-density polyethylene, or

low-density polyethylene/ethylene vinyl alcohol/low-density polyethylene pouches. Both pouch types were flushed with N2, in combination with or without an oxygen absorber), differing lighting conditions and also differing temperature for storage. Moreover, an oxygen absorber decreased the formation of hexanal content, degradation of colour; however the an increase in the concentration of saturated fatty acids and decrease in monounsaturated fatty acids was observed over the 12 month period at storage of 20 °C (Mexis and Kontominas 2011). It appears that oxygen absorbers are crucial for packaging of nuts and seeds to protect against degradation of fatty acid composition, an important nutritional characteristic and determinant of market value.

Fish and seafood products

Oxygen absorbers were also shown to be useful in decreasing sardine oil degradation. Over a 1 month period and storage temperature of 22 °C, ω3 polyunsaturated fatty acids of fish did not degrade during storage when packed with an oxygen absorber (Suzuki et al. 1985). Moreover, using an O2 absorber in combination with oregano essential oil (0.4 % v/w) extended the shelf life of rainbow trout fillets (Onchorynchus mykiss) stored at 4 °C. Shelf-life and fillet quality were shown to be superior using the combination of oxygen absorber and oregano oil extract (i.e. day 12 versus day 4 for control TVC >7 log cfu/g, partial inhibition of Pseudomonas spp., Enterobacteriaceae, pH stabilizing effect with reduced protein degradation products, and sensory rejection of product at day 4 versus a day 17 period. The day 17 contained both an oxygen absorber and oregano oil extract (Mexis et al. 2009). Besides food spoilage and pathogenic bacteria suppression, oxygen absorbers contribute to the nutritional stability of fish products much like nuts and seeds, and maintain the quality and market price of a packaged fish product.

Meat products

Oxygen absorbers have also been used in packaged meat and processed meat products (Renerre et al. 1996) to extend the shelf-life of stored grains (non-chemical insect repellent) (Ohguchi et al. 1983) and prevent transient discolouration (Gill and McGinnis 1995) by use of oxygen absorber (<O2 ppm to <10 ppm), and temperature 2 °C. Further, natural anti-oxidant substances have been used with beef patties and oxygen absorbers to extend shelf-life by 5–6 days, i.e. chitosan 1 % (Chounou et al. 2013), and a citrus extract at a concentration of either 0.1 or 0.2 ml/100 g of ground chicken meat) with an oxygen absorber extended shelf-life by up to 4–5 days (Mexis et al. 2012).

Regulatory aspects

Various commercial suppliers manufacture oxygen absorbers, and have demonstrated in trials that there are significant improvements in shelf life of packaged foods with different levels of water activity or oil content and type. In addition to the established products for oxygen scavenging from USA, Europe and Japan, brands such as OxySorb™ (Wholesale Group International Pty. Ltd. Australia) also maintains the highest level of quality in manufacturing oxygen absorbers.

Oxygen absorbers must meet with food safety regulatory compliance which includes Australian Standard 2070–1999, U.S. FDA document MAPP 5015.5 (Office of Pharmaceutical Sciences), and E.C. Directive 2002/72/EC and amendments, and HACCP requirements for articles that come into contact with food products. Further, shelf-life experiments are conducted to determine stability of the oxygen absorbers using third party laboratories accredited through ILAC (International Laboratory Accreditation Co-operative). The benefits of oxygen absorbers are ascribed to their correct usage.

In summary, the benefits of oxygen absorbers include but not limited to:

inhibiting the formation of aerobic pathogens, spoilage organisms and mould in dairy, breads, cakes, nuts, fish, and beef jerky products

significant improvement in maintaining the quality of polyunsaturated fats and oils in high fat- foods without causing rancidity (i.e. nuts and fish products)

retaining the fresh-roasted aroma of coffee and nuts

delaying non-enzymatic discolouration and darkening of fruits and some vegetables

extending the shelf-life of nutraceutical and pharmaceutical products

preventing oxidation of water and fat soluble vitamins i.e. tomatoes

inhibiting oxidation and condensation of berries

minimizing the need for some additives/preservatives (i.e. calcium propionate ‘E282’), which may be linked to changes in child behavior (Dengate and Ruben 2002).

Conclusions

The use of active packaging is an important development in preserving and enhancing the shelf life of packaged food materials. Up to date technology has not only improved the methods of food preservation but has also developed into new fields of food preservation which were previously seen as impractical. However, the real benefits are perceived by the consumer as an end user of the food. The increased number of preservative free foods available in supermarkets, with longer shelf-life, adds to the perception of a ‘fresh food’ shopping experience. Further, supermarkets and retails have a vested interest in increasing the shelf-life of food products naturally as consumers are becoming increasing aware of the harmful effects of some chemical preservatives. Moreover, the use of oxygen absorbers to extend the shelf-life of food decreases the land fill space (i.e. less food wastage), both of which need to be considered in the long run. Food security is also an important issue in the third world and developing nations, where an oxygen absorber and packaging cost but a few cents, but would ensure food security all year round, especially storing foods for use during drought. Similarly achieving environmental and sustainability advantages is a continuous challenge in food preservation both for the manufacturers and end users. Improved oxygen absorber systems in combination with moisture removal and active packaging technology help to reduce food product loss at the supermarket, as well as to enhance the recyclability and elimination of environmentally unfriendly materials which can now be recycled, especially for food manufacturers and processors. Newer agents that can preserve packaged food not only from oxidative degradation but other forms of degradation are continually being developed, but oxygen absorbers remain an integral, well established and utilized global food preservation system with high barrier packaging.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

Simon Cichello is the managing director and shareholder of Wholesale Group International Pty Ltd, a manufacturer and distributor of oxygen absorbers. He is a member of the Australian Institute of Food Science and Technology, Nutrition Society of Australia, and American Society for Nutrition. Other oxygen trademarks have been discussed in an equitable manner and it is my belief that the review acts as an academic review of the application of oxygen absorbers in food preservation.

He is also a nutritionist and western herbal medicine practitioner and advocate of a natural, preservative free, whole-foods diet. He is a consultant to over 100 national and international food manufacturers and government agencies (P.R. China) regarding the implementation of oxygen absorbers and desiccants in food, pharmaceuticals products to reduce synthetic preservative use.

References

- Abe Y (1990) Active packaging—A Japanese perspective. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Modified Atmosphere Packaging. Stratford-upon-Avon, United Kingdom October 15–17

- Berenzon S, Saguyf IS. Oxygen absorbers for extension of crackers shelf-life. LWT Food Sci Technol. 1998;31(1):1–5. doi: 10.1006/fstl.1997.0286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch F (1965) Preservative of oxygen-labile substances, e.g., Foods. U.S. Patent 3,169,068 February 9

- Brody AL, Strupinsky ER, Kline LR. Active packaging for food application. New York: CRC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Charles F, Sanchez J, Gontard N. Active modified atmosphere packaging of fresh fruits and vegetables: modeling with tomatoes and oxygen absorber. J Food Sci. 2003;68(5):1736–1742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb12321.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chounou N, Chouliara E, Mexis SF, Stavros K, Georgantelis D, Kontominas MG. Shelf life extension of ground meat stored at 4 °C using chitosan and an oxygen absorber. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2013;48(1):89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2012.03162.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cichello SA (2010) A guide to oxygen absorbers. Wholesale Group International Pty Ltd Publication. Available at www.wholesalegroup.com.au [Accessed August 16 2013]

- Cruz RS, Soares NFF, Andrade NJ. Evaluation of oxygen absorber on antimicrobial preservation of lasagna–type fresh pasta under vacuum packed. Ciênc Agrotec. 2006;30(6):1135–1138. doi: 10.1590/S1413-70542006000600015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dengate S, Ruben A. Controlled trial of cumulative behavioural effects of a common bread preservative. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38(4):373–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emenhiser C, Watkins RH, Simunovic N, Solomons N, Bulux J, Barrows J, Schwartz SJ. Packaging preservation of β-Carotene in sweet potato flakes using flexible film and an oxygen absorber. J Food Qual. 1999;22(1):63–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4557.1999.tb00927.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gill CO, McGinnis JC. The use of oxygen scavengers to prevent the transient discolouration of ground beef packaged under controlled, oxygen-depleted atmospheres. Meat Sci. 1995;41(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/0309-1740(94)00064-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idol RC (1991) A critical review of in-package oxygen scavengers. In: Sixth International Conference on Controlled/Modified Atmosphere/Vacuum Packaging, Scotland Business Research Princeton, New Jersey, USA

- Idol RC. A retail application for oxygen absorbers in Europe. Pack Alimentaire’93. Princeton: Scotland Business Research, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Idol RC. Oxygen absorbing labels. Packag Week. 1993;9:16. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PN, Sørensen G, Brockhoff P, Bertelsen G. Investigation of packaging systems for shelled walnuts based on oxygen absorbers. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(17):4941–4947. doi: 10.1021/jf021206h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latou E, Mexis SF, Badeka AV, Kontominas MG. Shelf life extension of sliced wheat bread using either an ethanol emitter or an ethanol emitter combined with an oxygen absorber as alternatives to chemical preservatives. J Cereal Sci. 2010;52(3):457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2010.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mexis SF, Kontominas MG. Effect of oxygen absorber, nitrogen flushing, packaging material oxygen transmission rate and storage conditions on quality retention of raw whole unpeeled almond kernels (Prunus dulcis) J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91(4):634–649. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mexis SF, Chouliara E, Kontominas MG. Combined effect of an oxygen absorber and oregano essential oil on shelf life extension of rainbow trout fillets stored at 4 degrees C. Food Microbiol. 2009;26(6):598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mexis SF, Chouliara E, Kontominas MG. Shelf life extension of ground chicken meat using an oxygen absorber and a citrus extract. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2012;49(1):21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsubishi (2009) MGC oxygen absorbers – oxygen absorber, keep products fresh. Available at http://www.mgc-a.com/AGELESS/AboutUs.html [Accessed January 09 2014]

- Nielsen PV, Rios R. Inhibition of fungal growth on bread by volatile components from spices and herbs, and the possible application in active packaging, with special emphasis on mustard essential oil. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;60(2–3):219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohguchi Y, Suzuki H, Tatsuki S, Fukami J. Lethal effect of an oxygen absorber on several stored grain and clothes pest insects. Japan J Appl Entomol Zool. 1983;27:270–275. doi: 10.1303/jjaez.27.270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renerre M, Gatellier P, Minard A, Roussel X, Lapinte M. Preservation in CO2 with oxygen absorber for improvement of shelflife of beef. Viandes Produits Carnes. 1996;17(6):297–299. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney ML. Oxygen scavenging from air in package headspaces by singlet oxygen reactions in polymer media. J Food Sci. 1982;47(1):291–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1982.tb11081.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney ML. Photosensitive oxygen scavenger films: an alternative to vacuum packaging. CSIRO Food Res. 1984;43:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Saranraj P, Geetha M. Microbial spoilage of bakery products and its control by preservatives. Int J Pharm Biol Arch. 2012;3(1):38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Wada S, Hayakawa S, Tamura S. Effects of oxygen absorber and temperature on ω3 polyunsaturated fatty acids of sardine oil during storage. J Food Sci. 1985;50(2):358–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1985.tb13401.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaga F, Itoh S, Tsuyuki H. Prevention of lipid oxidation in roasted and ground soybean with oxygen absorber during storage. J Jpn Soc Food Sci Tech. 1987;34:705–713. doi: 10.3136/nskkk1962.34.11_705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr CR, Clingeleffer PR. Use of an oxygen absorber for disinfestation of consumer packages of dried vine fruit and its effect on fruit colour. J Stored Prod Res. 2005;41(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2004.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Otterdijk R, Meybeck A (2011) Global food losses and food waste. Swedish Institute for Food and Biotechnology (SIK) Gothenburg, Sweden, and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy

- Wholesale Group International Pty. Ltd (2013) Available at http://www.wholesalegroup.com.au/oxygen_absorbers.html [Accessed January 09 2014]