Abstract

The fenugreek seed is the richest source of soluble and insoluble fiber and also known for its medicinal and functional properties. The major objective of this present study is fractionation of the fenugreek by roller milling method and characterization of roller milled fractions. The effects of moisture conditioning on fenugreek roller milling were studied using standard methods. The results observed were increase in coarse husk from 33.75–42.46 % and decrease in flour yield from 49.52–41.62 % with increase in addition of moisture from 12–20 %. At 16 % conditioning moisture, the yield of coarse husk was 40.87 % with dietary fiber and protein content of 73.4 % and 6.96 % respectively. The yellowness value (b) for the coarse husk (29.68) found to be lowest at 16 % conditioning moisture compared to the other coarse husk samples, showing maximum clean separation. The fiber fractions showed the viscosity of 6,392 cps at 2 % w/v concentration. The flour fraction was higher in protein (41.83 %) and fat (13.22 %) content. Roller milling process of fenugreek was able to produce > 40 % of coarse husk with 73.4 % dietary fiber (25.56 % soluble & 47.84 % insoluble) and > 48 % flour with 41.83 % protein content, where as the whole fenugreek contained 22.5 % protein & 51.25 % dietary fiber. Thus roller milling has proved to be a valuable method for the fractionation of fenugreek to obtain fiber and protein rich fractions.

Keywords: Roller milling, Fenugreek, Fractionation, Dietary fiber, Protein, Viscosity

Introduction

Fenugreek (Trigonellafoenum-graecum) is an annual crop belonging to legume family and commonly grown in many parts of world. Fenugreek is native of southeastern Europe and Western Asia, but at present it is grown in India, Northern Africa, and United States (Altuntas et al. 2005). Fenugreek has been used as a spice to enhance the sensory quality of foods and also known for its medicinal properties. Fenugreek is reported to have anti-diabetic effect in animals and humans (Gupta et al. 2001; Mondal et al. 2004; Murthy et al. 1990; Neeraja and Rajyalakshmi 1996; Ribes et al. 1984, 1986; Sharma et al. 1990; Vats et al. 2002). The other health benefits of the fenugreek are its ability to lower plasma cholesterol levels (Stark and Madar 1993; Rao 1996), antioxidant activity (Ravikumar and Anuradha 1999) and possess antineoplastic and anti-inflammatory properties (Sur et al. 2001).

India is one of the major producer and exporter of Fenugreek. According to Edison (1995), India claims 70–80 % of worlds export in fenugreek. Fenugreek seeds are about 2.5–6 mm long, 2–4 mm wide and 2 mm thick (Fazli and Hardman 1968). Fenugreek seed is dicotyledonous and consists of outer yellowish brown seed coat or husk. The seed coat is separated from the embryo by whitish translucent endosperm, mainly composed of soluble galactomannan gum. The centre portion contains hard, yellowish embryo, which is composed of good quality edible protein and fat. Fenugreek seed is very bitter and the bitterness is mainly due to the oil, steroidal saponins and alkaloids (Srinivasan 2006). The major portion of the seed (50 %) constitutes unavailable carbohydrates (Shankaracharya et al. 1973). The major constituents of fenugreek seeds are proteins 20 to 25 %, dietary fiber 45 to 50 %, fats 6 to 8 % and steroidal saponins 2 to 5 %.

Dietary fibres are indigestible carbohydrates found in plant foods and contain soluble and insoluble fibers. Soluble fiber increases the viscosity of the stomach contents that lowers the absorption of released glucose. It also lowers serum cholesterol and helps to reduce the risk of heart attack and colon cancer. Dietary fiber intake is shown to reduce the risk of diseases such as cardiovascular disease, colon cancer and obesity. A fenugreek seed is the richest source of soluble and insoluble fiber. The fenugreek seed contains about 30 % gel forming soluble fiber like the other soluble fiber of guar seeds, psyllium husk etc. The insoluble fiber is about 20 % of fenugreek seed, is bulk-forming like wheat bran (Chatterjee and Prakashi 1995). The dietary fiber from fenugreek is very stable, with a long shelf life and withstands frying, baking, cooking and freezing. The intake of 30 g fenugreek dietary fiber a day and appropriate physical activity leads to gradual and significant weight-loss without adverse protein-calorie malnutrition and other ill effects of dieting (Chadha 1985).

The roller milling process involves break opening the grain, gradual scraping the endosperm from bran by break rolls and then gradually reducing the chunk of the endosperm into flour by a series of grindings by reduction rolls, with intermediate separation of products by sifters & purifiers (Bass 1988). Roller milling process is traditionally used to fractionate wheat into bran, germ and various flour streams. The nutrients in fenugreek seed are not uniformly distributed into the seed components, giving scope for the physical separation by roller milling method. The embryo has higher content of protein and lipids, while dietary fibres are concentrated in husk.

Literature survey shows that fenugreek seeds are not fractionated by roller milling and the fractions derived by this process have not yet been standardized. In view of the growing interest in using fenugreek fractions as functional food ingredients, this study was initiated to evaluate the milling potential of fenugreek. The effects of conditioning moisture on fenugreek roller milling were studied to establish the best compromise between yield and refinement of fractions. The distribution of nutrients in roller milled fractions of fenugreek was reported. The fractions subjected to scanning electronic microscopic study to observe the changes that occur in the milled fractions during roller milling.

Materials and methods

Raw material

A commercial fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) seeds procured from the local market of Mysore city, India were used for the present study.

Physical characterization of fenugreek seeds

Seed dimensions

The fenugreek seed dimensions such as length, width and thickness were measured by a digital vernier caliper in randomly selected 100 seeds.

Thousand seed weight

The thousand seed mass was determined by randomly selected 100 seeds and converted to 1,000 seed basis.

Bulk density

The bulk density is the ratio of the mass of the seeds to its total volume. It was determined by filling a 1,000 ml container with seeds from a height of about 15 cm, striking the top level and weighing the contents (Akaaimo and Raji 2006; Mwithiga and Sifuna 2006).

Nutritional characterization of fenugreek

The fenugreek sample was analyzed for moisture content (method 44–15), ash (method 08–01), protein (method 46–10), fat (method 30–10) according to the standard methods (AACC 2000) and dietary fiber (AOAC 1999).

Roller milling of fenugreek

The fenugreek seeds were cleaned by using the standard apparatus labofix the mini cleaner (Schmidt-Seeger GmbH, Germany) and than manually to remove all foreign matters, dust, dirt and broken seeds. To study the effect of conditioning moisture, fenugreek samples were conditioned to the different desired moisture content (12, 14, 16, 18 and 20 %) and rested for 24 h before milling. The required water quantity was calculated using following equation.

Where:

- Q

is the amount of water (L).

- W

is the weight of seed at initial moisture content (kg).

- M2

is the desired moisture content of seed (%).

- M1

is the initial moisture content of seed (%).

The samples of cleaned fenugreek were weighed and poured in to the batch rotary drum mixer and total quantity of water for the batch was divided into 2–4 fractions and sprinkled on the grains. After each sprinkling, the mixture was rotated for about 5 min and about 30 min in the end and rested for 24 h. All the conditioned fenugreek samples milled in duplicate using Buhler laboratory-scale roller mill (MLU-202). The Buhler laboratory-scale mill, which is a six passages roller mill, consists of three breaks (B1 – B3) and three reduction rolls (C1 – C3). Each of the passage was followed by the sifter with two size separation. The laboratory bran duster was used for dusting of coarse and fine husk to remove any attached embryo portion.

Nutritional characterization of milled fractions

The fractions from rolled milled fenugreek were analysed for their nutrient contents as explained in the “Nutritional characterization of fenugreek” section.

Colour measurement

The color of the milled fractions of fenugreek was measured using the Hunter Lab color measuring system, Model Labscan, XE (Reston USA). The L a b colour scale was used where L is the degree of lightness value, a is intensity of colour in the direction of green to red color and b is intensity of colour in the direction of blue to yellow. A white board made from barium sulfate with 100 % reflectance was used as a standard. Milled fractions were placed in the sample holder and the reflectance was auto recorded for the wavelength ranging from 360 to 800 nm. The test was done in quadruplicates and the average value was reported.

Viscosity of fenugreek roller milled fractions and whole fenugreek flour

Roller milled coarse fractions of fenugreek and whole grain is milled using lab mill to produce the flour of <200 μm and used for the viscosity analysis. Aqueous solutions of 2 % w/v were prepared using a magnetic stirrer, at a medium speed and subjected to viscosity measurement at ambient temperature in a Brookfield viscometer model LVT using spindle no. 3 at 20 rpm.. Readings were recorded from 0 min to 24 h at regular intervals of time. Each determination was done in triplicate and the mean value was reported.

Electron microscopic studies of fenugreek seed and the milled fractions

The scanning electron microscopy studies of fenugreek seed and milled fractions were carried out using Leo Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) model 435VP (UK) (Prabhasankar et al. 2003). Samples were placed on a specimen holder with the help of double-sided scotch tape and sputter-coated with gold (2 min, 2 mbar). Finally each sample was transferred to a microscope where it was observed at 15 kV and a vacuum of 9.75 × 10 −5 Torr.

Results and discussion

Physico-chemical characteristics of fenugreek

The fenugreek selected for the study had the following physico-chemical characteristics: moisture content 9.23 %, length 4.2 mm, width 3.8 mm, thickness 1.9 mm, thousand kernel weight- 18 g, bulk density- 685.42 Kg/m3, ash – 3.06 %, protein – 22.12 %, dietary fiber – 52.94 % and fat – 6.56 %.

Roller milling of fenugreek

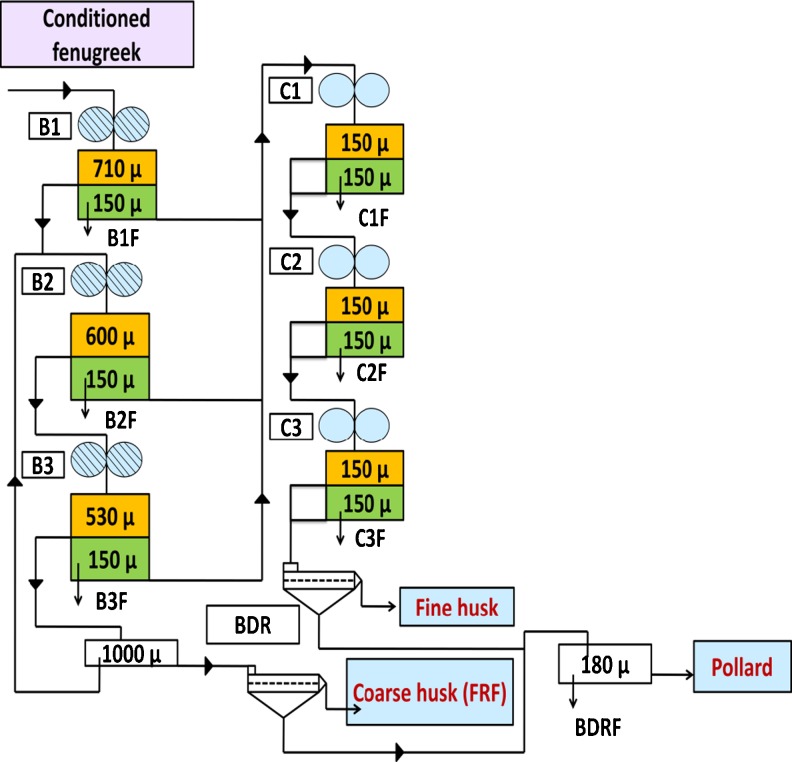

The conditioned samples of fenugreek were milled by using lab mill. The milling flow sheet developed for fenugreek is shown in Fig. 1. The lab mill with three breaks and three reduction passages produces six streams of flour. To obtain the high quality of husk with less protein and high fiber content, cleanness of husk is extremely important. In milling of fenugreek the stock going to the end reduction passage is relatively high. Hence two bran dusters were incorporated in the flow sheet for cleaning of coarse and fine husk. The throughs of the bran dusters further sifted to obtain the flour. All the flour streams obtained by the roller milling of fenugreek were mixed to get straight run flour. The roller milled fractions were mixed based on the colour values, which resulted into production four milled products (coarse husk, fine husk, flour and pollard). The pollard is the mixture of husk and the embryo.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of laboratory mill for the roller milling of fenugreek. B- Break rolls, C – Reduction roll, BDR- Bran duster

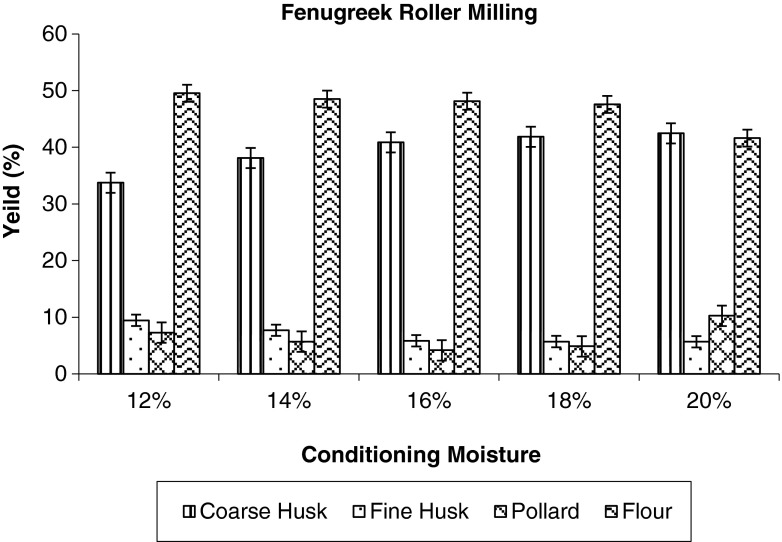

The yields of the rolled milled fractions of fenugreek at different pre conditioned moisture are shown in Fig. 2 and photographs in Fig. 3. The objective of the break rolls is to cut open the grain and gradually scrap the embryo from the husk (seed coat and endosperm) to produce coarse clean husk with least damage. The breaks rolls were adjusted to produce the clean intact husk with least damage. The results show that the yield of coarse husk increases with increase in the conditioning moisture and yield of fine husk decreases at the same time. The increase in the yield of coarse husk was because of toughening of husk at higher moisture content which reduces the husk friability. The coarse husk yield was found to be less at 12 and 14 % conditioning moisture as compared to higher moisture. The higher conditioning moisture content (16, 18 and 20 %) showed little influence on the yield of coarse husk content. As shown by the results the yield of the flour decreased with increasing conditioning moisture from 12 to 20 %. The yield of pollard decreased from 7.28 to 4. 17 % with increase in moisture content from 12 to 16 % and then increased to 10.28 % for 20 % moisture content. At higher moisture content of 18 and 20 %, the clean separation of husk and germ was not efficient and also the embryo was sticky, difficult to grind and sift. This has resulted into higher pollard and less flour yield. At lower moisture content coarse husk yield was less with more damage to husk and embryo was hard, difficult to ground.

Fig. 2.

Effect of conditioning moisture on yield of roller milled fractions of fenugreek

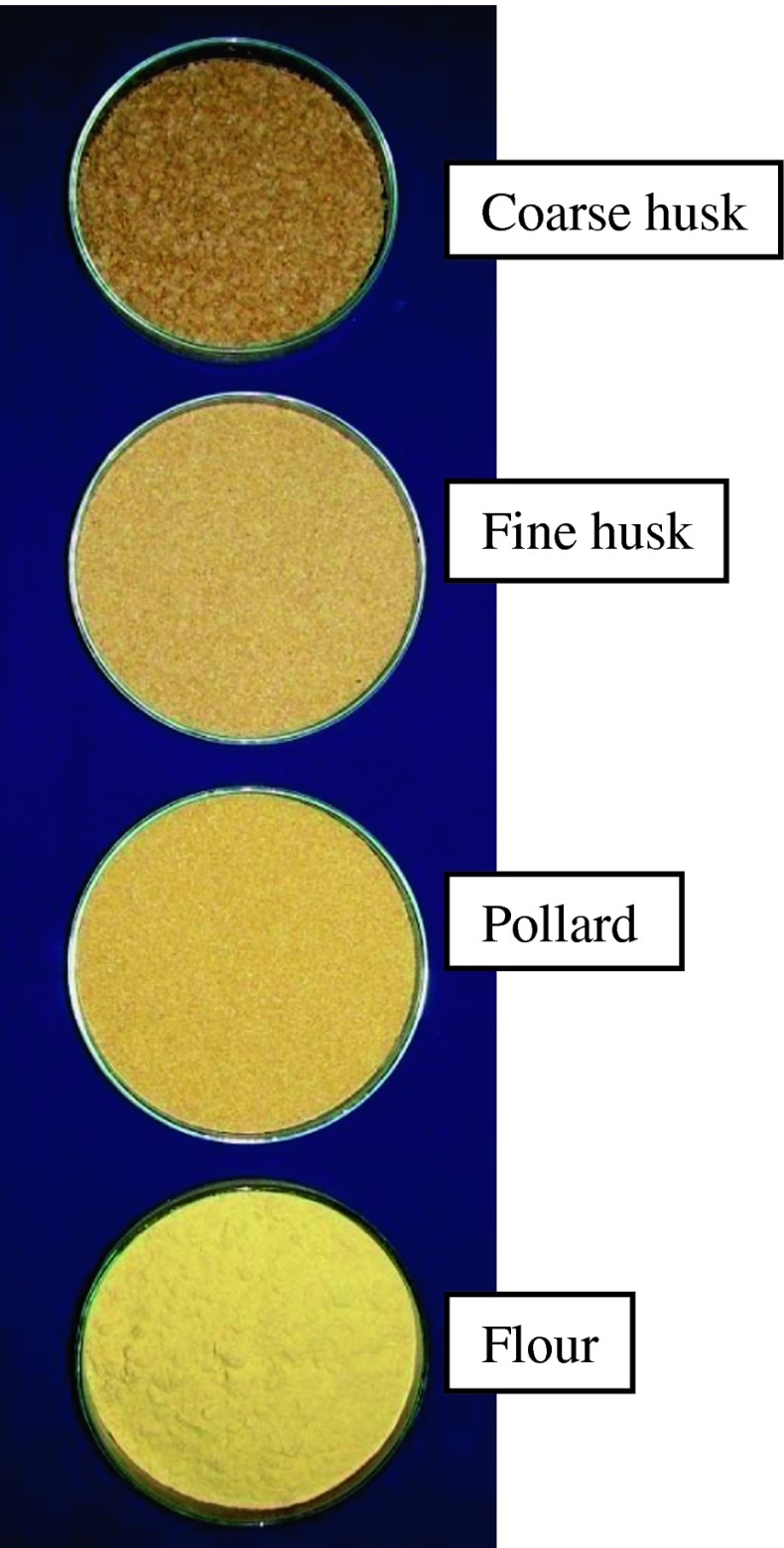

Fig. 3.

Photograph of roller milled fenugreek fractions

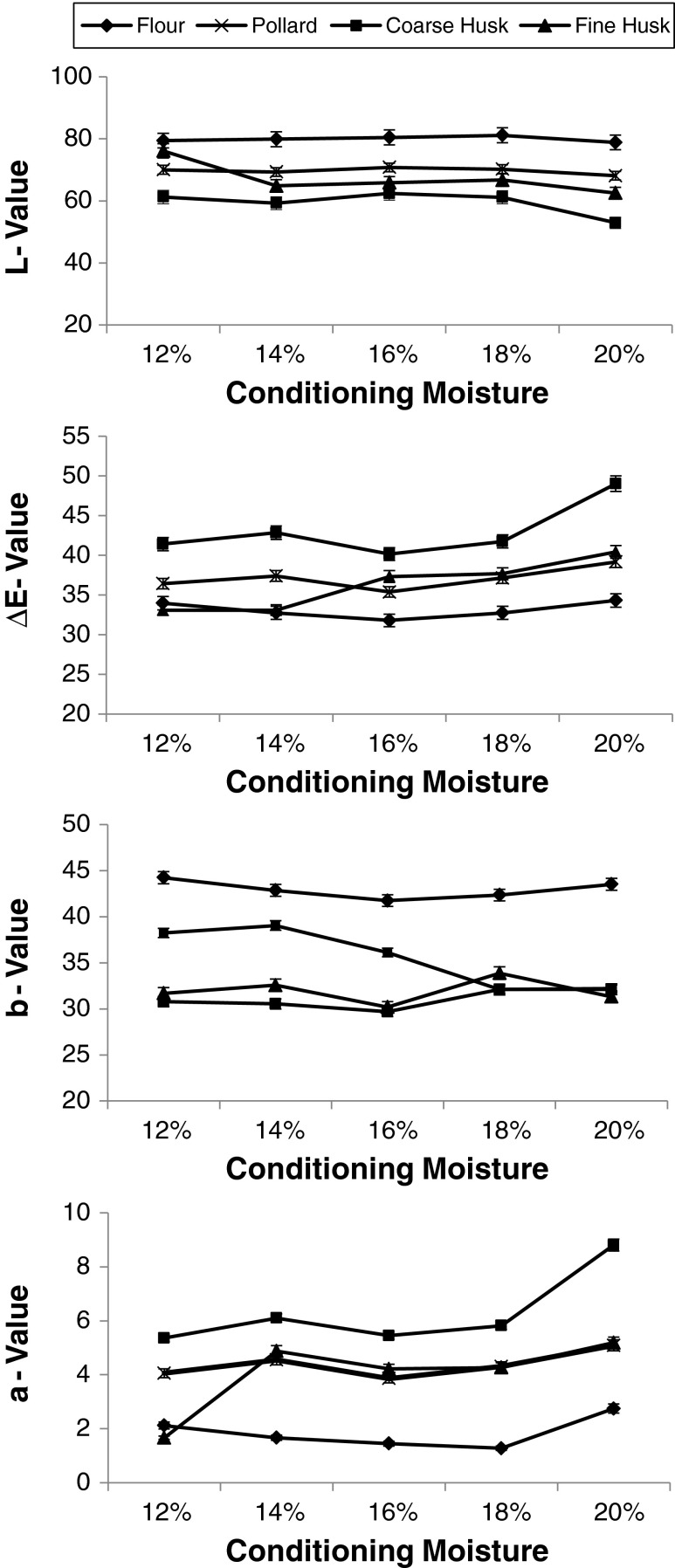

Colour measurement

The colour values in term of lightness (L) and colour (+ a: red, -a: green, +b: yellow, -b: blue) of roller milled fractions of fenugreek are summarized in Fig. 4. The L values for the flour increased from 79.45 to 81.16 with increase in conditioning moisture from 12 to 18 % and then decreased to 78.82. The higher brightness value is the indication of clean separation of husk and the embryo. The L value of 62.42 was found to be the highest for the coarse husk for all the moisture levels. The yellowness value (+b) which indicate the presence of embryo in the husk fraction was found to be a useful parameter to decide the milling efficiency. The yellowness value for the coarse husk (29.68) found to be lowest at 16 % moisture level compared to the other coarse husk. The yellowness value for coarse husk increased at 18 and 20 % moisture content indicating the higher amount of embryo content in it. The results indicate that roller milling of fenugreek at 16 % conditioning moisture gives better separation of husk and embryo. Hence the yellowness value (+b) is found to be important parameter for the evaluation of fenugreek roller milling. The redness value (+a) of flour fraction decreased with increase in conditioning moisture from 12 to 16 % and then increased for 18 & 20 %. The redness value is the indication of presence of husk in the flour. The colour difference (ΔE) values were lower for flour, coarse husk and pollard obtained at 16 % moisture milling. At higher moisture content of 20 % all the roller milled fractions observed higher ΔE values, showing larger colour difference.

Fig. 4.

Colour measurement of roller milled fenugreek fractions at different conditioning moisture

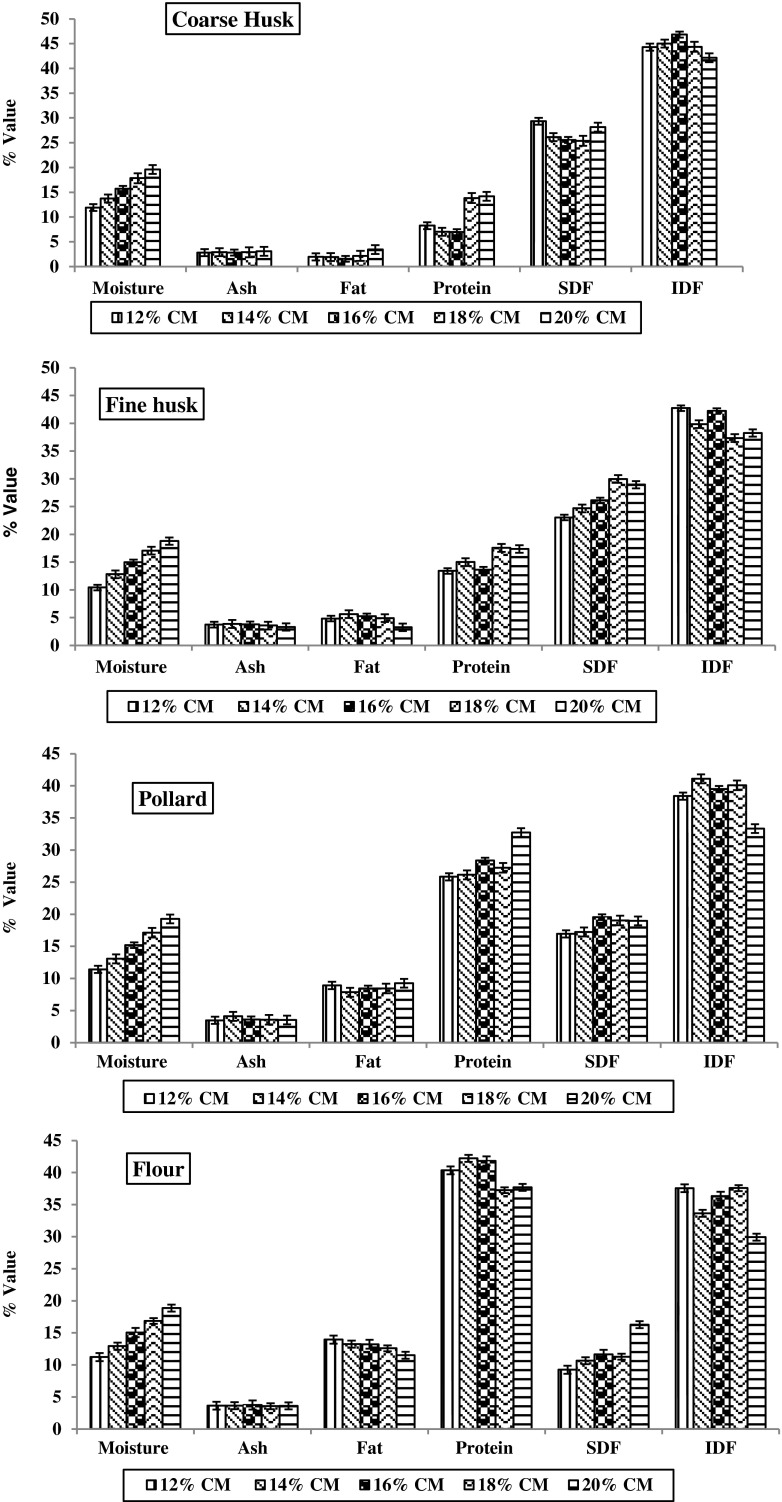

Nutritional characterization of milled fractions

Chemical analyses of roller milled fractions of fenugreek are summarized in Fig. 5. The moisture content of coarse husk was found to be higher as compared to other roller milled fractions. The coarse husk comes at early stage of milling process resulting into lower moisture loss. Higher moisture loss was observed in the flour fraction. Reduction passages ground embryo into flour with pressure and transported by more pneumatic lift, which resulted into higher moisture loss. The ash content was found less in coarse bran as compared to the other fractions. Among the coarse husks, the lowest ash content of 2.81 % was observed at 16 % moisture milling. The distribution of fat was uneven among the roller milled fractions of fenugreek. It was observed from results that the highest fat content was found in flour fraction followed by the pollard, fine husk and coarse husk. The fat content of coarse husk ranged from 1.56 to 3.45 % by milling at different moisture content. The lowest fat content of 1.56 % for coarse husk was at 16 % moisture level. The fat content of 5.23, 8.43 and 13.22 % were observed for fine husk, pollard and flour fraction respectively milled at 16 % moisture content. The results shows that the fat content is concentrated in embryo (flour fractions). The protein content of flour fraction was highest among all roller milled fractions of fenugreek. The flour fractions exhibited higher protein content when milled at low moisture level; whereas the protein content decreased at high moisture milling (18 and 20 %). This could be because of the loss of protein rich embryo into other fractions such as pollard and husk. The protein content of coarse husk is indicator of separation of husk from embryo during the milling. The protein content of 6.96 % was found lowest in coarse husk milled at 16 % moisture with yield of 40.87 %, indicating the clean separation of husk fraction. This result is in accordance with lowest yellowness value (+b) of 29.68 for coarse husk fractions at 16 % conditioning moisture. The protein content of pollard, which is the combination of husk and embryo, ranged from 25.83 to 32.71 %. The fenugreek coarse husk was rich in total dietary fiber (72.4 %) of which soluble and insoluble dietary fiber were 25.56 % and 46.84 % respectively at 16 % moisture. The ratio of the insoluble dietary fiber to soluble dietary fiber was greater than 1.4 for all coarse bran obtained at different milling moisture. The fine husks showed the total dietary fiber content of above 65 %. Thus the roller milling process was able to produce the fiber rich fraction (coarse and fine husk) with the yield of about 45 %. Naidu et al. (2011) reported that fenugreek husk containing the highest level of dietary fiber and phenolic acids, whereas embryo is enriched in saponins and protein. Srichamroen et al. (2011) observed that the fenugreek husk separated by dry milling substantially improves the aqueous recovery of galactomannans from fenugreek seeds compared to whole seeds.

Fig. 5.

Chemical characteristics of roller milled fractions of fenugreek. Except moisture, all values are on dry weight basis

Viscosity of fenugreek roller milled fractions and whole fenugreek flour

The viscosity of roller milled fraction and whole fenugreek flour are shown in Table 1. The viscosity of coarse husk was found to be highest among the milled fractions. The viscosity of coarse husk increased from 576 cps at 0 min to 6,392 cps at 24 h. This shows the gelling properties of coarse husk with gum content. Pilgaonkar et al. (2004) showed in their patent that the fiber rich fraction (husk) of fenugreek are useful as excipient for pharmaceutical dosage forms for various routs of administration, and can be used as disinterment, filler, binder, coating agent, thickener and like, for preparation of variety of dosage forms. The fenugreek husk with maximum concentrate of 4–6 % of dosage form can be used as a tablet binder (Avachat et al. 2007). The SRF from the embryo observed no viscosity, where as the viscosity of fenugreek whole grain flour 150 cps at 24 h.

Table 1.

Viscosity of fenugreek roller milled fractions and whole fenugreek flour

| Time (hours) | Roller milled fenugreek fractions and whole fenugreek flour viscosity (cps) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse husk | Fine husk | Pollard | SRF | Whole Fenugreek flour | |

| 0 | 576 ± 25 | 304 ± 45 | 144 ± 20 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| 0.5 | 1,390 ± 40 | 352 ± 25 | 240 ± 15 | 0 ± 0 | 16 ± 0 |

| 1 | 2,432 ± 35 | 400 ± 20 | 256 ± 25 | 0 ± 0 | 32 ± 10 |

| 1.5 | 2,772 ± 20 | 432 ± 35 | 288 ± 20 | 0 ± 0 | 48 ± 15 |

| 2 | 3,472 ± 25 | 432 ± 20 | 272 ± 15 | 0 ± 0 | 64 ± 10 |

| 4 | 4,640 ± 30 | 432 ± 20 | 320 ± 30 | 0 ± 0 | 112 ± 25 |

| 8 | 5,560 ± 50 | 432 ± 25 | 304 ± 20 | 0 ± 0 | 160 ± 20 |

| 24 | 6,392 ± 30 | 464 ± 20 | 400 ± 30 | 0 ± 0 | 152 ± 15 |

Electron microscopic studies of fenugreek seed and the milled fractions

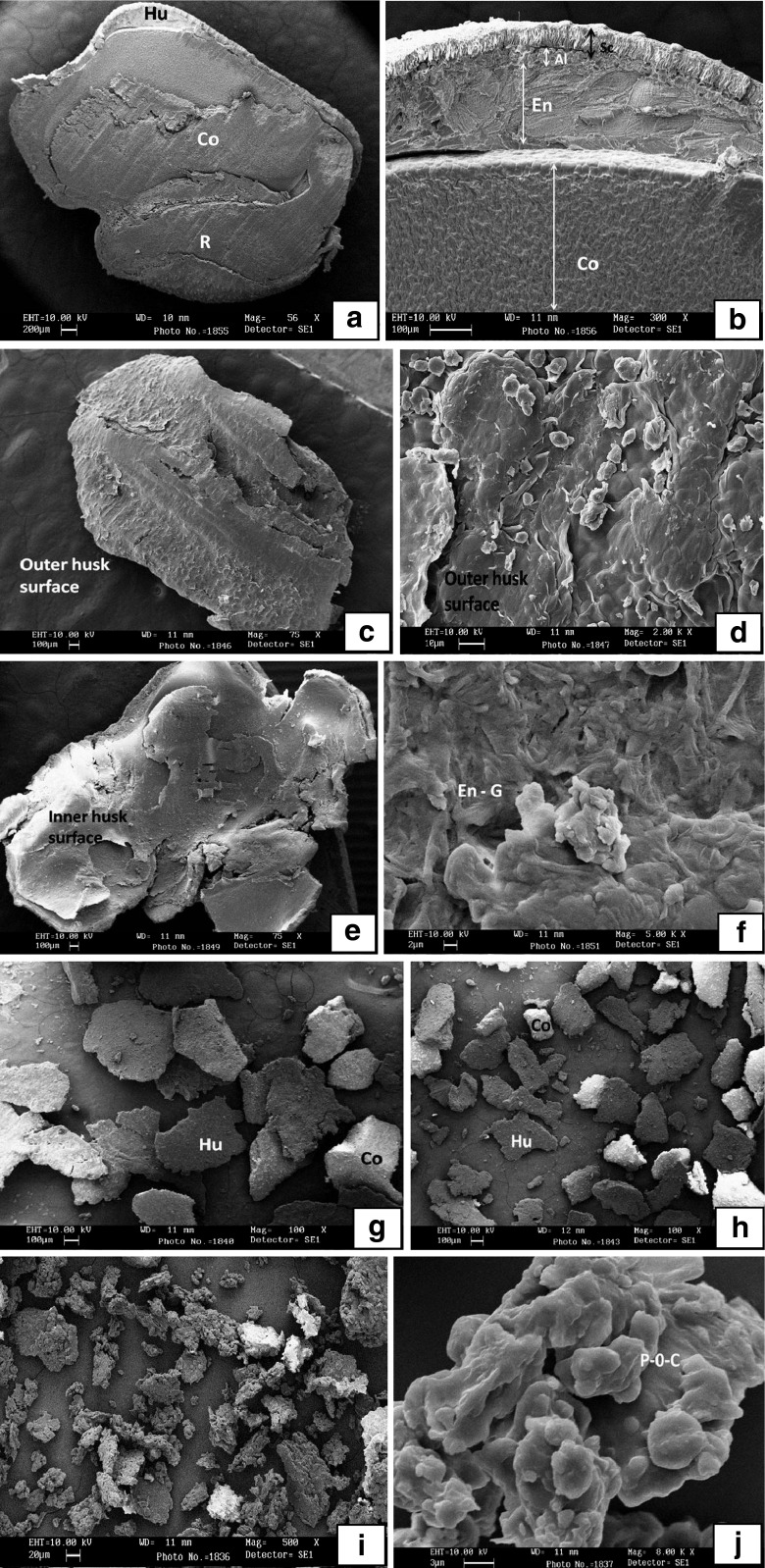

Figure 6a is the scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of transversely dissected fenugreek seed showing the cotyledon, radical and husk. The embryo is relatively large and completely surrounded by the endosperm, which in turn surrounded by seed coat (Fig. 6b). SEM of fenugreek seed obtained is in agreement with Srichamroen et al. (2011), Gong et al. (2005), Reid (1985) and Reid and Bewley (1979). In the mature seed majority of endosperm cells are nonliving, the cytoplasmic content of which are occluded by the store reserve of glactomannan. The aleurone layer is sandwiched between the endosperm and seed coat, which is one cell layer of living tissue. During the roller milling process the outer husk was removed by the break rolls in the form of coarse husk. The fenugreek husk removed by roller milling process is the combination of seed coat, aleurone layer and endosperm. The coarse husk micrograph (Fig. 6c) contains the thick protective cuticle covering from outside. The inside micrograph (Fig. 6d and e) of coarse husk shows the gum of endosperm. The chemical analysis of coarse husk shows higher content of soluble and insoluble fibers. The micrograph of fine husk samples showed smaller particle size containing the embryo, which could also be proven by protein content of fine husk. The pollard fraction contained embryo and husk. The flour fraction, which mainly comes from the embryo showed sticky clusters of protein and oil.

Fig. 6.

Scanning electron micrographs of rolled milled fenugreek fractions. Co-Cotyledon; Hu-Husk; R-Radical; En-Endosperm; Sc-Seed coat; Al-Aleurone layer; En-G- Endosperm gum; P-O-C– Protein oil complex. a (56X) b (300X) – fenugreek seed; c (75X) D (2000X) e (75X) F (2000X)– coarse husk; g (100X)– fine husk; h (100X) – pollard; i (500X) j (8000X) – flour

Conclusions

We have first time showed that the roller milling as a valuable process for the fractionation of fenugreek. The results showed that the conditioning moisture level has significant influence on the yield and composition of milled fractions. At lower moisture milling the husk was readily damaged resulting in lower yield of coarse husk fractions while at higher moisture level it was observed that embryo fraction was mixing with husk. The clean separation of husk and embryo was reported at 16 % conditioning moisture, thus conditioning to medium moisture is recommended. It was observed that roller milling of fenugreek generated fractions contained varied nutrient composition. The soluble and insoluble fibers are highly concentrated in the coarse and fine husk fractions. The coarse husk fraction observed higher viscosity, making it useful as binding ingredient for food and pharmaceutical. The flour fraction had higher protein and oil content, which is useful for extraction of neutracceuticals such as fenugreek oleoresin, saponins and, 4-hydroxy-isoleucine (4-HIL).

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Mr. Anabalagan, CIFS, CFTRI, and Mysore, India for his help in carrying out scanning electron microscopy.

References

- AACC . American Association of Cereal Chemists. Approved methods. St. Paul: AACC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Akaaimo DI, Raji AO. Some physical and engineering properties of prosopisafricana seed. Biosyst Eng. 2006;95(2):197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2006.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altuntas E, Engin Ozgoz O, Taser F. Some physical properties of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graceum) seeds. J Food Eng. 2005;71:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis of AOAC International, method 991.43. 16. Maryland: AOAC International; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Avachat AM, Gujar KN, Kotwal VB, Patil S. Isolation and evaluation of fenugreek husk as granulating agent. Ind J Pharm Sci. 2007;69(5):667–679. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.38475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bass EJ. Wheat flour milling. In: Pomeranz Y, editor. Wheat: chemistry and technology (Vol. 2) 3. St Paul: American Association of Cereal Chemists; 1988. pp. 230–257. [Google Scholar]

- Chadha YR. The wealth of India. Council of Scientific and Industrial Research: New Delhi; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A, Prakashi SC (eds) (1995) Treatise on Indian medicinal plants, Vol. 2. Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi

- Edison S. Spices research support to productivity. In: Ravi N, editor. The Hindu survey of Indian agriculture. Madras: Kasturi & Sons Ltd., National Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fazli FRY, Hardman R. The spice, Fenugreek,(Trigonella foenum graecum L.): its commercial varieties of seed as a source of Diosgenin. Trop Sci. 1968;10:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Bassel GW, Wang A, Greenwood JS, Bewley JD. The emergence of embryos from hard seeds is related to the structure of the cell walls of the micropylar endosperm, and not to endo-ß-mannanase activity. Ann Bot. 2005;96:1165–1173. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Gupta R, Lal B. Effect of Trigonellafoenum-graecum (fenugreek) seeds on glycaemic control and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a double blind placebo controlled study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:1055–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal DK, Yousuf BM, Banu LA, Ferdousi R, Khalil M, Shamim KM. Effect of fenugreek seeds on the fasting blood glucose level in the streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Mymensingh Med J. 2004;13:161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy RR, Murthy PS, Prabhu K. Effects on blood glucose and serum insulin levels in alloxan induced diabetic rabbits by fraction GII of T. foenum-graecum. Biomedicine. 1990;10:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mwithiga G, Sifuna MM. Effect of moisture content on the physical properties of three varieties of sorghum seeds. J Food Eng. 2006;75:480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.04.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu MM, Shyamala BN, Naik JP, Sulochanamma G, Srinivas P. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of the husk and endosperm of fenugreek seeds. J Food Sci Technol. 2011;44(2):451–456. [Google Scholar]

- Neeraja A, Rajyalakshmi P. Hypoglycaemic effect of processed fenugreek seeds in humans. J Food Sci Technol. 1996;33:427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgaonkar PS, Rustomjee MT, Gandhi AS, Bhumra VS (2004) Fiber rich fraction of Trigonella foenum graecum seed and its use as a pharmaceutical excipient. States patent US 2005/0084549

- Prabhasankar P, Indrani D, Jyotsna R, Venkateswara Rao G. Scanning electron microscopic and electrophoretic studies of the baking process of south Indian parotta—an unleavened flat bread. Food Chem. 2003;82:603–609. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00017-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PU. Nutrient composition and biological evaluation of mesta (Hibiscus sabdariffa) seeds. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1996;49:27–34. doi: 10.1007/BF01092519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar P, Anuradha CV. Effect of fenugreek seeds on blood lipid peroxidation and antioxidants in diabetic rats. Phytother Res. 1999;13:197–201. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199905)13:3<197::AID-PTR413>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JSG. Cell wall storage carbohydrates in seeds-biochemistry. Adv Bot Res. 1985;11:125–155. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60170-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JSG, Bewley JD. A dual role for the endosperm and its galactomannan reserves in the germinative physiology of fenugreek (Trigonellafoenum-graecumL.), an endospermic leguminous seed. Planta. 1979;147:145–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00389515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribes G, Sauvaire Y, Baccou JC, Valette G, Chenon D, Trimble ER, Loubatieres- Mariani MM. Effects of fenugreek seeds on endocrine pancreatic secretion in dogs. Ann Nutr Metab. 1984;28:37–43. doi: 10.1159/000176780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribes G, Sauvaire Y, Costa CD, Baccou JC, Loubatieres-Mariani MM. Antidiabetic effects of subfractions from fenugreek seeds in diabetic dogs. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986;82:159–166. doi: 10.3181/00379727-182-42322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaracharya NB, Anandaraman S, Natarajan CP. Chemical composition of raw and roasted fenugreek. J Food Sci Technol. 1973;10:179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma RD, Raghuram TC, SudhakarRao N. Effect of fenugreek seeds on blood glucose and serum lipids in type I diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1990;44:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srichamroen A, Vasanthan T, Acharya SN, Basu TK. Dry-milling improves the aqueous recovery of Galactomannans from Fenugreek seeds. Curr Nutr Food Sci. 2011;7:63–72. doi: 10.2174/157340111794941067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan K. Fenugreek (Trigonellafoenum-graecum): a review of health beneficial physiological effects. Food Rev Int. 2006;22(2):203–224. doi: 10.1080/87559120600586315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, Madar Z. The effect of an ethanol extract derived from fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) on bile acid absorption and cholesterol levels in rats. Brit J Nutr. 1993;69:277–287. doi: 10.1079/BJN19930029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur P, Das M, Gomes A, Vedasiromoni JR, Sahu NP, Banerjee S, Sharma RM, Ganguly DK. Trigonella foenum graecum (fenugreek) seed extract as an antineoplastic agent. Phytother Res. 2001;15:257–259. doi: 10.1002/ptr.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vats V, Grover JK, Rathi SS. Evaluation of antihyperglycaemic and hypoglycemic effect of T.foenum-graecumL., Ocimum sanctum L., Pterocorpusmarsupium Linn in normal and alloxanized diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79:95–100. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]