Abstract

Growth of microorganisms in environments containing CO2 above its critical point is unexpected due to a combination of deleterious effects, including cytoplasmic acidification and membrane destabilization. Thus, supercritical CO2 (scCO2) is generally regarded as a sterilizing agent. We report isolation of bacteria from three sites targeted for geologic carbon dioxide sequestration (GCS) that are capable of growth in pressurized bioreactors containing scCO2. Analysis of 16S rRNA genes from scCO2 enrichment cultures revealed microbial assemblages of varied complexity, including representatives of the genus Bacillus. Propagation of enrichment cultures under scCO2 headspace led to isolation of six strains corresponding to Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subterraneus, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus safensis, and Bacillus megaterium. Isolates are spore-forming, facultative anaerobes and capable of germination and growth under an scCO2 headspace. In addition to these isolates, several Bacillus type strains grew under scCO2, suggesting that this may be a shared feature of spore-forming Bacillus spp. Our results provide direct evidence of microbial activity at the interface between scCO2 and an aqueous phase. Since microbial activity can influence the key mechanisms for permanent storage of sequestered CO2 (i.e., structural, residual, solubility, and mineral trapping), our work suggests that during GCS microorganisms may grow and catalyze biological reactions that influence the fate and transport of CO2 in the deep subsurface.

INTRODUCTION

Geologic carbon dioxide sequestration (GCS) is an emerging strategy to abate CO2 emissions associated with the burning of fossil fuels by capture, compression, and subsurface injection of generated CO2 (1, 2). Although many subsurface geologic formations targeted for storage of compressed CO2 are known to be biologically active environments (3–6), the extent to which biological processes may play a role in the fate and transport of CO2 remains unknown (7). CO2 exists as a supercritical fluid (scCO2) at the temperature and pressures of the vast majority of reservoirs targeted for sequestration (i.e., >31°C and 72.9 atm). scCO2 has generally been regarded as a microbial sterilizing agent due to a combination of factors, including cytoplasm acidification, increased CO2 anion concentration, osmotic stress, membrane permeabilization and leakage via CO2 extraction, and physical cell rupture (8–14).

While there has been no direct evidence that microorganisms can sustain metabolic activity and grow in environments containing scCO2, previous work indicates this possibility. Survival of spores and biofilms after short-term scCO2 exposure (i.e., minutes to hours) (8, 9, 15, 16) is well documented, and recent studies show that mineral matrices may enhance microbial survival of scCO2 exposure by providing substrates for biofilm formation and/or by creating buffered microenvironments (10, 17). Biogeochemical models also suggest that diverse forms of microbial metabolism are thermodynamically favorable under reservoir conditions post-CO2 injection (3, 18), where an aqueous phase in direct contact with scCO2 may have dissolved CO2 concentrations exceeding 2.5 M (3). Furthermore, high-pressure incubations to simulate reservoir conditions with elevated (but not supercritical) CO2 have demonstrated activity of acetoclastic methanogens (under 49.3-atm pressure with 86.4 mM CO2) (19) and homoacetogens (under 395-atm total pressure with 126 mM CO2) (20). Recently, field studies at the Ketzin CO2 sequestration site in Germany and the Otway Basin site in Australia provided evidence that changes in microbial community composition occur following CO2 injection, suggesting that a combination of processes, including differential survival and possibly growth, occurs in the subsurface after exposure to near- and supercritical levels of CO2 (21, 22).

Whether microorganisms survive and remain active post-CO2 injection is relevant for predicting the fate and stability of the injected CO2. Microbial activity can influence the various trapping mechanisms that are crucial to permanent storage of sequestered CO2. Prior work has documented that microbial biofilms can be employed to plug pore spaces and impede the flow of scCO2 through sandstone cores, providing a means of “structural trapping” for a mobile CO2 phase (15, 23). Trapping of CO2 residuals in pore spaces by capillary forces (residual trapping) may be affected by biosurfactant effects on wetting (24). Bacterial surfaces may provide sites for carbonate mineral nucleation, while bacterial activity can increase the rate of mineral weathering and therefore liberate the metal cations necessary for incorporation of CO2 into carbonate minerals (mineral trapping) (25–27). Finally, increased dissolution of CO2 into an aqueous phase (solubility trapping) has been demonstrated by pH increases induced by bacterial ureolysis under high partial CO2 pressure (pCO2) (28).

In this study, we tested whether environmental microbes could be isolated with the ability to survive and exhibit microbial activity (growth) during exposure to scCO2. We performed a series of experimental enrichment cultures inoculated with subsurface fluid filtrate or well core samples from three subsurface environments targeted for CO2 sequestration: the Frio-2 site near Liberty, TX (29); the Otway Basin site in southeastern Australia (22, 30, 31); and the King Island site near Stockton, CA (32). These three sites are geologically attractive as prospective CO2 injection zones because they consist of high-porosity/permeability sandstone formations overlaid by low-permeability sealing layers capable of structurally trapping buoyant scCO2 in the underlying zone. Enrichment cultivation was followed by isolation and characterization of strains able to grow under scCO2. Microbial growth under scCO2 is surprising given its inhibitory properties and indicates the possibility that microbial activities will influence CO2 trapping during geologic carbon dioxide sequestration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subsurface sample collection and storage.

Samples from GCS sites were utilized as inocula for microbial enrichment cultures using scCO2 as the selective agent. Samples from the Frio-2 site were collected as part of the Frio-2 project and shared courtesy of Tommy Phelps (Oak Ridge National Laboratory). For sample collection, 10 to 20 liters of formation fluids was collected by U-tube from the Frio-2 CO2 sequestration site near Liberty, TX, before, during, and after CO2 injection (29, 33). Frio-2 formation fluids from 1,528- to 1,534-m depth were filtered through borosilicate glass filters (nominal pore size, 0.8 μm) and frozen on site. Three samples screened for this study correspond to samples collected prior to CO2 injection, 7.5 h after injection, and 372 days postinjection. Otway Basin samples consisted of rock cores from 929- to 1,530-m depth from the Pemble, Paaratte, and Skull Creek formations (30). Otway cores were collected as part of the CO2CRC project in Southeast Australia (www.co2crc.com.au). The King Island core sample was obtained from the Mokelumne River formation at ∼1,447-m depth during drilling of the Citizen Green #1 deep-characterization well by the West Coast Regional Sequestration Partnership (WESTCARB), San Joaquin County, CA. Rock cores were kept refrigerated at 4°C prior to analysis.

Enrichment cultivation.

Inocula for enrichment cultures were prepared in an anaerobic glove bag with an O2 and H2 monitor (95% CO2-5% H2) and added to 4- or 10-ml pressure vessels containing a 50% volume of growth medium (below). For Frio-2 samples, inocula consisted of 10 μl of hydrocarbon and particulate residue from the surface of glass fiber filters, collected with a sterile scalpel. For Otway Basin cores, drilling fluid tracer penetration data were used to guide collection from the core interior where contamination was least likely. The selected regions of Otway cores were pulverized with a stainless steel mortar and pestle, and 1 g of crushed rock was used as inoculum. For the King Island formation core, no tracer-free interior could be identified, as the sediment was highly permeable and unconsolidated. Thus, a representative sample from the center of the King Island core was used as inoculum and processed in the same manner as Otway cores.

Medium for enrichment cultivation of Frio-2 samples was modified GYP sodium acetate mineral salts broth (GYP) consisting of (in g/liter) 2.0 glucose, 1.0 yeast extract, 1.0 tryptic peptone, 1.0 sodium acetate, 0.2 MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 NaCl, 0.01 MnSO4·4H2O, and 0.01 FeSO4·7H2O. Both GYP and MS media were used for enrichment cultivation from the Otway Basin and King Island cores with supplements targeting different microbial functional groups added to MS medium (34). MS medium consisted of (in g/liter) 0.5 yeast extract, 0.5 tryptic peptone, 10.0 NaCl, 1.0 NH4Cl, 1.0 MgCl2·6H2O, 0.4 K2HPO4, 0.4 CaCl2, 0.0025 EDTA, 0.00025 CoCl2·6H2O, 0.0005 MnCl2·4H2O, 0.0005 FeSO4·7H2O, 0.0005 ZnCl2, 0.0002 AlCl3·6H2O, 0.00015 Na2WoO4·2H2O, 0.0001 NiSO4·6H2O, 0.00005 H2SeO3, 0.00005 H3BO3, and 0.00005 NaMoO4·2H2O. MS medium supplements consisted of 0.5 g/liter glucose for fermenters; 1.3 g/liter MnO2, 2.14 g/liter Fe(OH)3, and 1.64 g/liter sodium acetate for metal reducers; 0.87 g/liter K2SO4, 0.83 g/liter FeSO4, and 0.82 g/liter sodium acetate for sulfate reducers; or 1.3 ml trimethylamine and 0.82 g/liter sodium acetate to target methanogens (34). Culture media were added to serum bottles and degassed with a stream of 100% CO2 or 100% N2 gas for 30 min prior to pressurization. Na2S (at 0.25 g/liter), a reducing agent to maintain anaerobicity, and resazurin (at 0.001 g/liter), a visual redox indicator, were added to culture media. Following inoculation, vessels were pressurized and incubated for 2 to 4 weeks at 37°C for Frio-2 samples and 37 and 60°C for Otway Basin and King Island samples, respectively. In addition to the above media, Luria-Bertani broth (LB) (Difco) and LB agar were used for strain cultivation at 37°C under ambient aerobic conditions.

The pH of ambient and CO2-saturated medium was measured at 1 atm and 21°C using an Orion model 520A pH meter. The pH of medium under an scCO2 headspace was measured by visualization of a pH indicator strip (EMD Chemicals) through the sapphire window of a 25-ml view cell (Thar Technologies; 05422-2). In addition, PhreeqC version 2 was used to predict the equilibrium pH and potential precipitation of chemical species in the growth medium (Table 1) under a CO2 or N2 atmosphere and as a function of temperature and pressure. Thermodynamic data were obtained from the Lawrence Livermore National Library (LLNL) database.

TABLE 1.

Observed and predicted pH and predicted CO2 concentration as a function of GYP culture medium composition,a headspace gas, and pressure at 37°C

| Headspace | Pressure (atm) | Predicted pHb | Observed pHc | Predicted [CO2] (M)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | 1 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 0.026 |

| 100 | 3.6 | 3.9–4.5 | 2.7 | |

| N2 | 1 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 0 |

| 100 | 7.0 | NDd | 0 |

Growth medium components (g/kg): 0.72 acetate, 0.431 Na+, 0.607 Cl−, 0.002 Fe2+, 0.0025 Mn2+, 0.0196 Mg2+, 0.08575 SO42−, 0.1028 S2−. Buffering of pH by the acetate system in GYP maintained the final pH above the value predicted for deionized water alone.

Geochemical modeling performed in PhreeqC calling the LLNL database.

pH measured by Orion model 520A pH meter (P = 1 atm) or visualized (P = 120 atm) via indicator strip (EMD Chemicals).

ND, not determined.

High-pressure incubation.

Vessels for high-pressure growth (see Fig. S10 in the supplemental material) were 316 stainless steel high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column bodies or 316 stainless steel tubing (4- and 10-ml capacity). Vessels were fitted with ball valves (Supelco) or quarter-turn plug valves (Swagelok or Hylok). Vessels were filled to one-half capacity (2 or 5 ml) with cultivation medium, and following inoculation, the headspace of the stainless steel culture vessels, representing 50% of the total vessel volume, was pressurized at a rate of 2 to 3 atm min−1 to 100 to 136 atm with industrial-grade N2 gas (Airgas) or with extraction-grade CO2 gas (Airgas) with a helium (He) head pressure such that the final gas mixture was 97 to 99% CO2. Pressurized vessels were incubated in a 37°C warm room, with shaking at 100 rpm to increase mixing of media and subsurface inocula. Following incubation, the vessels were connected with 316 stainless steel tubing and fittings to Swagelok pressure gauges to measure the final vessel pressure before samples were depressurized at a rate of 3 to 5 atm min−1 over approximately 30 min. Generally, culture vessels with initial headspace pressures of >100 atm lost between 5 and 25 atm of pressure, due to slow leakage through fittings, over the course of a multiple-week incubation, with greater losses associated with longer incubations. Unless specifically noted, all vessel incubation data reported here maintained scCO2 headspace pressures of >72.9 atm, the critical pressure for CO2 mixed with ≤3% inert helium at 37°C (35), or for incubations at lower pressures, final pressure (Pfinal) was ≥70% of Pinitial. All pressures were measured at room temperature (21°C). Based on the ideal gas law, we can estimate a maximum pressure increase of 6% associated with incubation of reactors at 37°C, although since scCO2 is a nonideal gas, this may be an overestimate. Following depressurization, cultures were transferred to an anaerobic chamber (Coy Lab Products) containing a 95% CO2-5% H2 atmosphere for subsampling and passaging. All pressure vessels and valves were cleaned and autoclaved between uses, and high-pressure tubing was flushed before use with 10% bleach for 30 min, rinsed with MilliQ H2O, rinsed with 100% ethanol, and dried with CO2 gas.

Enrichment cultures from the Frio-2, Otway, and King Island sites were serially passaged by diluting 10% (vol/vol) of the previous culture in fresh growth medium under a 95% CO2-5% H2 atmosphere, with pressurization to 120 atm with CO2, followed by incubation at 37°C. The contents of enrichment vessels were analyzed for cell abundance at the end of passages and in the inocula prior to incubations. Frio-2 passages 1 to 3 were incubated for 15 days each, while passage 4 was incubated for 60 days; subsequent passages were incubated for 9 to 15 days (Table 2). Otway and King Island passages were incubated for longer time periods (i.e., 1 to 2 months) to increase the likelihood of cellular growth based on earlier observations. Samples from each passage were subjected to microscopic enumeration and archived as glycerol stocks at −80°C.

TABLE 2.

ScCO2 enrichment cultivation summary

| Sample origin (incubation time [days] for initial enrichment and passages 1–3, respectively) | Growth mediuma | Biomass (cells/ml) observed for enrichment/passage at temp (°C)c |

Isolateb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|||||||

| 37 | 60 | 37 | 60 | 37 | 60 | 37 | 60 | |||

| Frio-2; formation water particles; 1,500 m (15, 14, 15, 15) | GYP | +++ | NDd | +++ | +++ | +++ | MIT0214 | |||

| Otway core 2; 1,164.12–1,164.33 m; silty claystone (21, 33, 61, 41) | MS + fermenter | − | + | + | ||||||

| MS + metal reducer | − | + | − | |||||||

| MS + sulfate reducer | − | + | + | |||||||

| MS + methanogen | − | + | + | + | ||||||

| GYP | − | − | ||||||||

| Otway core 3; 1,193.59–1,193.69 m; sandstone (14, 28, 81, 40) | MS + fermenter | + | + | + | + | − | − | |||

| MS + metal reducer | + | − | + | +++ | +++ | MITOT1 | ||||

| MS + sulfate reducer | + | − | − | |||||||

| MS + methanogen | − | − | ||||||||

| GYP | − | − | ||||||||

| Otway core 4; 1,239.31–1,239.48 m; silty claystone (28, 81, 41, ND) | MS + fermenter | + | + | + | + | − | − | |||

| MS + metal reducer | + | + | − | + | − | |||||

| MS + sulfate reducer | + | + | − | − | ||||||

| MS + methanogen | − | + | − | |||||||

| GYP | − | − | ||||||||

| Otway core 5; 1,273.86–1,273.95 m; sandstone (29, 42, 49, ND) | MS + fermenter | + | − | + | − | |||||

| MS + metal reducer | − | − | ||||||||

| MS + sulfate reducer | − | − | ||||||||

| MS + methanogen | − | − | ||||||||

| GYP | − | − | ||||||||

| King Island core; 1,447 m; unconsolidated sandstone (29, 38, 49, 37) | MS + fermenter | + | + | + | − | ++ | ++ | |||

| MS + metal reducer | + | − | + | +++ | +++ | WMR1 | ||||

| MS + sulfate reducer | − | − | ||||||||

| MS + methanogen | + | − | + | +++ | +++ | WMe1, WMe2 | ||||

| GYP | + | − | + | +++ | +++ | WG1 | ||||

Growth medium consisted of GYP or basal MS medium with supplementation targeting various microbial metabolic groups (see Materials and Methods).

Strain identification by 16S rRNA gene BLASTN: MIT0214, B. cereus; MITOT1, B. subterraneus; WMR1, B. safensis; WMe1, B. safensis; WMe2, B. megaterium; WG1, B. amyloliquefaciens.

+, ++, and +++, biomass observed at <104, 104 to 105, and >105 cells/ml, respectively. −, biomass not observed.

ND, not determined.

Enumeration of cell density.

To quantify biomass, we used a combination of methods, including direct cell counts, viable cell counts, and optical density. Cell density at the beginning and end of incubations was determined by microscopic epifluorescent cell staining using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma) or SYTO9 (Invitrogen) with shaking for 10 min in the dark. Five hundred microliters to 1 ml of sample was then filtered onto 25-mm, 0.2-μm-pore-size, black polycarbonate filters (Nuclepore), followed by 2 washes with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). PBS was incubated on the filtered sample for 1 min to help wash off excess dye. Filters were laid on slides under microscope immersion oil with a coverslip (Thermo Scientific) and were stored at 4°C in the dark until counting. The cell density (in cells/ml) was calculated by multiplying the mean cell counts (in one 10-by-10 microscope grid) by the dilution factor and then by 3.46 × 104 (as one 10-by-10 grid at ×1,000 magnification corresponds to 1/3.46 × 104 of a 25-mm filter). Samples were visualized on a Zeiss Axioplan fluorescence microscope. Images were captured on a Nikon D100 camera using the NKRemote live imaging software. Viability counts, i.e., CFU plating, were performed using Luria broth agar. Viable spore counts were carried out by heating aliquots to 80°C for 10 min to kill vegetative cells (36) prior to plating on Luria broth agar. Culture optical density (600 nm [OD600]) was measured on a Bausch and Lomb spectrophotometer (1-cm path length) or via a 96-well microplate reader (BioTek Synergy 2) (200 μl per well). Optical density was not measured for incubations using metal reducer medium due to confounded readings from solid particulate content.

For MIT0214, growth was defined by increased cell density and evidence of vegetative cell morphologies by microscopy. Growth-positive cultures had at least 45-fold-increased direct cell counts relative to initial inocula of less than 1 × 106 spores/ml, or at least a 5-fold increase in direct cell counts for cultures with inocula greater than 1 × 106 spores/ml, as MIT0214 final cell densities generally varied between 1 × 107 and 1 × 108 cells/ml. For MITOT1, growth was defined by observation of culture turbidity accompanied by at least a 4-fold increase in viable cell counts (CFU/ml) above the initial spore density (on average, increases were >50-fold) and at least 25-fold-higher viable counts compared to replicates without observed turbidity since samples without evident growth all showed a decline in viable counts relative to the initial viable counts of the inoculated cultures, presumably due to a loss of spore viability during the incubation period.

Extraction of DNA and analysis of 16S rRNA gene diversity in enrichment cultures.

DNA extraction from Frio-2 sample enrichment passages was performed using a protocol modified for Gram-positive bacteria (37). DNA extraction from Otway Basin project passages was performed using two methods, the Qiagen Blood and Tissue DNA extraction kit protocol for Gram-positive cells (Qiagen) or the MoBio soil DNA extraction kit (MoBio). Amplification of 16S rRNA genes from extracted DNA was performed using universal bacterial primers 515F 5′-GTG CCA GCM GCC GCG GTA A-3′ and 1406R 5′-ACG GGC GGT GWG TRC AA-3′ (Frio-2 passages 1, 2, and 7) and 27F 5′-AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG-3′ and 1492R 5′-TAC GGY TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3′ (Frio-2 passage 9, Otway passage 3, and colony-purified isolates). PCR mixtures (20 μl per reaction mixture) contained 25 to 75 ng of genomic DNA, 1× Phusion polymerase buffer, 0.4 μM (each) primer (IDT), 0.4 μM deoxynucleotide mixture, and 1 U Phusion polymerase (New England BioLabs). Thermal cycling conditions consisted of an initial 3 min at 95°C followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s, followed by a final extension time of 5 min. Every PCR included negative and positive controls.

Amplified 16S rRNA gene fragments from Frio-2 samples were gel purified (Qiagen gel extraction kit) and ligated into the pJET1.2 vector (Fermentas) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Ligation products were transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α or E. coli Top10 cells, and clones were selected for sequencing (using LacZ/isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG] plating). For the Frio-2 enrichment, sequencing reaction mixtures were prepared using BigDye Terminator 3.1 according to the manufacturer's instructions and sequencing was performed on an ABI 3130 platform. Otway project 16S rRNA gene fragments were gel purified (Qiagen gel extraction kit) and sequenced commercially (Genewiz, Cambridge, MA). Removal of vector and primer sequences and manual editing and clustering of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 99% nucleotide identity were performed using Sequencher 4.5 (Gene Codes Corp.). Chimeric sequences were identified by Chimera Check 2.7 (RDP II Database) software and removed from analysis. 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from passages of the scCO2 enrichments from the Frio-2 and Otway Basin sites and from all colony-purified isolates were uploaded to the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) server (38) for multiple-sequence alignment using their weighted neighbor-joining tree-building algorithm. The stability of the groupings was estimated by bootstrapping on 100 trees, and phylogenetic tree files were downloaded and visualized with MABL (39).

Isolation of strains and preparation of spores.

Samples from passages 2, 5, and 3 of the enrichment cultures from Frio-2 (sample 9-26-1039-20L), Otway Basin (core 3), and the King Island core, respectively, were plated on LB agar and incubated aerobically at ambient pressure at 37°C to obtain colonies, followed by colony purification by restreaking on LB agar and identification using DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Since isolates had 16S rRNA sequence types matching cloned sequences corresponding to endospore-forming bacteria, spores were prepared as described in reference 40 to serve as inocula for subsequent characterization. For spore preparation, overnight stationary-phase cultures grown under aerobic ambient conditions in LB medium were diluted 1:50 into modified G medium which consists of the following (in g/liter): 2.0 yeast extract, 0.025 CaCl2·2H2O, 0.5 K2HPO4, 0.2 MgSO4·7H2O, 0.05 MnSO4·4H2O, 0.005 ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.005 CuSO4·5H2O, 0.0005 FeSO4·7H2O, 2.0 (NH4)2SO4, adjusted to pH 7.1 after autoclaving. Cells were incubated with shaking for 72 h to induce sporulation and then centrifuged for 15 min at 4,000 × g. Samples were resuspended and centrifuged 5 times in autoclaved wash buffer containing 0.058 g/liter NaH2PO4·H2O and 0.155 g/liter Na2HPO4·7H2O with 0.01% (vol/vol) Tween 20 to prevent aggregation of spores. Spore preparations were heat treated at 80°C for 10 min to kill residual vegetative cells. Spores for each isolated strain were stored in wash buffer at 4°C until further use.

Physiological characterization.

Physiological tests for isolates displayed in Table 3 were conducted in triplicate. LB medium was used for assaying temperature, pH, and salinity ranges, with positive growth scored by an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of greater than 0.05. Medium pH was adjusted with NaOH or HCl followed by incubation at 37°C. Salinity was adjusted with NaCl in LB medium followed by incubation at 37°C. LB agar was used for colony morphology determination after 20 h of incubation at 37°C. Spore formation was determined by confirming viability after heat-killing cultures grown in modified G sporulation medium and by microscopic evaluation after staining for spores (41).

TABLE 3.

ScCO2 enrichment isolate physiology

| Bacillus sp. strain | 16S rRNA BLAST identification (% identity) | Isolation environment | O2 requirement | Spore formation | Temp range (°C)a | pH rangeb | Salinity range (g/liter)c | Colony morphologyd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MITOT1 | B. subterraneus (98.6) | Sandstone core, 1,193.6 m, 39°C; Otway Basin, Australia | Facultative anaerobe | + | 23–37 | 4–8 | 0.5–50 | 0.2 mm, circular, entire, raised, smooth, grayish |

| MIT0214 | B. cereus (99.8) | Formation water, 1,528–1,534 m, 55°C; Frio-2, Texas | Facultative anaerobe | + | 23–45 | 4–10 | 0–40 | 5 mm, circular, undulate, raised, smooth, off-white |

| WG1 | B. amyloliquefaciens (98.6) | Unconsolidated sandstone core, 1,447 m; King Island, CA | Facultative anaerobe | + | 23–55 | 2–10 | 0–60 | 4 mm, circular, undulate, umbonate, wrinkly, off-white |

| WMR1 | B. safensis (99.2) | Unconsolidated sandstone core, 1,447 m; King Island, CA | Facultative anaerobe | + | 23–55 | 4–12 | 0–60 | 2 mm, circular, entire, raised, smooth, yellow-white |

| WMe1 | B. safensis (99.1) | Unconsolidated sandstone core, 1,447 m; King Island, CA | Facultative anaerobe | + | 23–45 | 4–12 | 0–60 | 2 mm, circular, entire, raised, smooth, yellow-white |

| WMe2 | B. megaterium (99.4) | Unconsolidated sandstone core, 1,447 m; King Island, CA | Facultative anaerobe | + | 23–45 | 4–10 | 0–60 | 2 mm, circular, entire, convex, smooth, yellow-white |

Temperatures tested were 9, 23, 30, 37, 45, 55, and 65°C over 72 h.

pHs tested were 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, and 12 over 123 h.

Salinities tested were 0, 0.5, 1, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 g/liter over 72 h.

Colony morphologies were determined after 20 h of growth on LB agar.

Measuring growth and survival in anaerobic CO2 and N2 atmospheres at variable pressure.

The dynamics of growth and survival of strains isolated from CO2 sequestration sites and the type strains Bacillus subtilis PY79, Bacillus mojavensis JF-2 (ATCC 39307), and Bacillus cereus (ATCC 14579) were investigated under variable headspace gas composition and pressures. Inocula consisted of either cells or spores; vegetative cell cultures were grown overnight to stationary phase under aerobic conditions and diluted approximately 100-fold to 107 cells/ml in fresh growth medium while spores maintained in wash buffer were diluted to approximately 105 spores/ml unless otherwise specified. Media for MIT0214 and MITOT1 were GYP and MS media with the metal reducer supplement, respectively. Incubations at pressures from 3 to 136 atm were conducted in 316 stainless steel pressure vessels at 37°C with shaking at 100 rpm. Pressurization was achieved by regulating backpressure from the CO2-He tank. Determination of growth dynamics under 1 atm N2 or 1 atm 95% CO2-5% H2 was conducted in 100-ml serum bottles at 37°C with shaking at 100 rpm.

To test whether Bacillus spores could tolerate indirect or direct exposure to scCO2, spores of B. cereus MIT0214 (Frio-2 isolate), B. subtilis PY79, and B. mojavensis JF-2 were aliquoted into Durham vials in equal volumes of spore storage buffer corresponding to 5 × 107, 7 × 105, and 1 × 108 spores, respectively, and dried for 2 to 3 days at 70°C to achieve a desiccated state. Dried spores were either covered in 2 ml of fresh spore storage buffer or left desiccated and then incubated under scCO2 (100 atm, 37°C) in a 1-liter High Pressure Equipment Company (HIP) vessel for 2 weeks. After depressurization, samples were plated for viable counts on LB medium. Desiccated samples were resuspended in 2 ml of buffer before plating.

Antibiotic-amended control experiments were used to confirm growth under scCO2. We amended reactors containing spores with both kanamycin and chloramphenicol antibiotics at 100 and 10 μg/ml, respectively, in parallel with reactors without antibiotics. Additionally, we included no-cell controls for all experiments. Presence or absence of growth was assessed with a combination of metrics, including direct cell counts, changes in cell morphology from spores to vegetative cells, viable cell counts, and optical density.

Statistical methods.

Logistic regression analyses were performed using JMP Pro v. 10 where growth outcome (growth/no growth) was the dependent variable and incubation time and inoculating spore density were the independent variables. Student's t tests were performed in Microsoft Excel.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

16S rRNA gene sequences from isolates and clones characterized in this study have been deposited in the NCBI database with accession numbers KP873174 to KP873199.

RESULTS

Enrichment cultivation under scCO2.

Enrichment cultivation of subsurface samples in bioreactors containing nutrients, water, and scCO2 yielded isolates from all three GCS sites examined in this study (Fig. 1; Table 2). Enrichment cultures inoculated with filtered formation fluid (Frio-2) or crushed rock cores (Otway or King Island) were evaluated for growth under an scCO2 headspace after 14 to 30 days as evidenced in some cases by an increase in the turbidity of culture medium. All samples were evaluated by epifluorescence microscopy to confirm biomass in turbid cultures and to screen for microbial cells in nonturbid samples (Fig. 1). Microscopy and extraction of total nucleic acids confirmed biomass generation after successive rounds of dilution and growth (Table 2).

FIG 1.

Epifluorescent microscopy of enrichment cultures grown under scCO2, filter concentrated onto 25-mm 0.2-μm-pore-size membranes, and stained with DAPI (A) or SYTO9 (B to H). Bars, 10 μm. (A) Cells from Frio-2 initial enrichment. (B) Cells from Frio-2, passage 1, counterstained with propidium iodide (red) to identify membrane-compromised cells. (C) Cells from Otway core 3, passage 3, showing larger vegetative cells and smaller cells that may be spores observed within the same sample. (D) King Island initial enrichment, metal reducer medium. (E to H) Images correspond to cultures of MIT0214, MITOT1, WMe2, and WG1, respectively. Cultures in panels E to H were inoculated with spores, with a mixture of mostly vegetative cells and some spores visible after 30 days of growth under scCO2. Black particles (denoted by white arrowheads in panel F) correspond to metal solids from the growth medium for metal reducers.

The composition of microbial assemblages enriched under an scCO2 atmosphere was determined by analysis of cloned 16S rRNA gene sequences for enrichments from the Frio-2 and Otway samples achieving cell biomass greater than approximately 105 cells/ml. The libraries from the initial enrichment and first passage of the Frio-2 sample revealed a mixed community of microbes dominated by members of the Bacillus genera (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). DNA isolated from Frio-2 passages 7 and 9 revealed a single dominant Bacillus sequence type sharing 99.8% 16S rRNA sequence identity (1,463/1,465 nucleotides) with B. cereus ATCC 14579 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Biomass was detected in enrichment cultures inoculated with four different core samples from the Otway Basin under a variety of media and environmental conditions (Table 2). However, sparse cell densities (≤104 cells/ml) did not yield PCR-amplifiable DNA. Subsequent rounds of dilution and incubation in scCO2 bioreactors were performed, leading to increased biomass consisting of a mixture of vegetative and spore-like cells for core 3 in MS medium with an oxidized metal supplement (Fig. 1C; Table 2). The 16S rRNA gene was amplified and cloned from DNA extracted from passage 3 of Otway core 3, yielding 26 clones of a single ribotype matching B. subterraneus with 98.5% identity (1,502/1,521 nucleotides) (Table 3; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). scCO2 enrichment cultures inoculated with material from the King Island core revealed positive growth in 5 out of 8 incubations (Table 2). 16S rRNA clone libraries of King Island enrichments were not pursued as the core was unconsolidated and thus fully permeated by drilling tracer fluid, which likely contaminated the microbial diversity. The 16S rRNA gene of isolates from the scCO2 enrichment of King Island core material was sequenced following colony purification (Table 3).

Colony purification and strain characterization.

Since the Bacillus spp. identified in clone libraries are known to be predominantly aerobic and heterotrophic/copiotrophic, we attempted to isolate Bacillus strains as colonies on LB agar plates from scCO2 enrichment passages of all samples with significant growth (>105 cells/ml). When growth under scCO2 was observed, depressurized cultures were used as inocula and subsequent colony formation under ambient aerobic conditions (37°C) was observed after 1 to 3 days. Individual colonies with distinct morphologies were colony purified and identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and corresponded to B. cereus (Frio-2 sample, passages 2 and 7, isolate MIT0214); Bacillus subterraneus (Otway core 3, passage 5, isolate MITOT1); and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus megaterium, and Bacillus safensis (2 strains) (King Island core, passage 3, isolates WG1, WMe2, WMe1, and WMR1, respectively) (Table 3; also see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Isolates were subjected to physiological characterization and were facultative anaerobes with variable ranges of pH, temperature, and salinity similar to previously characterized Bacillus spp. (Table 3). Isolates were subjected to regrowth experiments to confirm bacterial growth under scCO2.

Growth of Bacillus strains MIT0214 and MITOT1 and Bacillus type strains under scCO2.

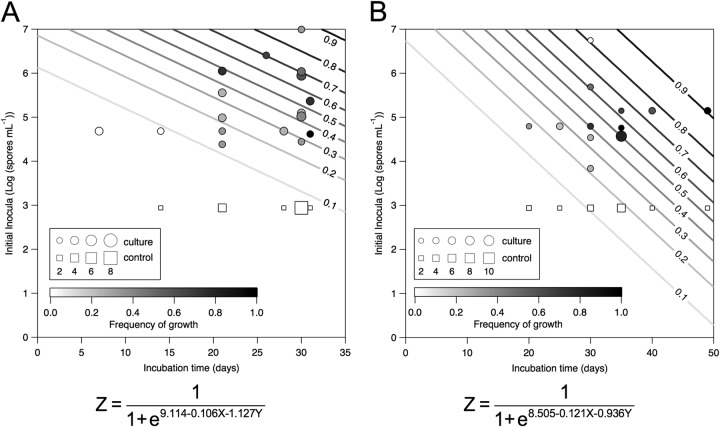

Based on our observations of biomass increases in enrichment cultures, spore formation in isolated strains, and the lethal effects of scCO2 on vegetative cells of isolates and type strains grown under ambient conditions (see Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material), we hypothesized that spores but not vegetative cells would germinate and grow under scCO2. To test our hypothesis, we inoculated growth medium with a range of spore concentrations (2.4 × 104 to 9.9 × 106 spores/ml for isolate MIT0214 and 6.9 × 103 to 5.6 × 106 spores/ml for isolate MITOT1), followed by incubation under scCO2 from 1 week to 49 days (Fig. 2), accompanied by antibiotic (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material) and no-cell controls. As we observed highly variable outcomes (i.e., growth/no growth) in replicate cultures of MIT0214 and MITOT1 incubated under an scCO2 headspace, we used logistic regression (Fig. 2A and B) to determine the relationship between frequency of growth under scCO2, incubation time, and initial spore density. For >20-day incubations of strain MIT0214, 26/78 cultures exhibited increased cell density (average final cell density of 5.6 × 107 cells/ml), while 0/15 no-cell controls and 0/30 antibiotic controls displayed growth (Fig. 2A; see also Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). For ≥20-day incubations of strain MITOT1, 32/58 cultures exhibited increased cell density (average final cell density of 1.2 × 107 cells/ml), while no increase in cell density was seen for no-cell controls (0/15) or antibiotic controls (0/4) (Fig. 2B; see also Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). For logistic regression analysis, no-cell controls were input at half the detection level (i.e., at 870 cells/ml), while antibiotic controls were excluded from the model. As expected, growth under scCO2 is significantly affected by both initial inoculum concentration and incubation time (Fig. 2A: P = 0.045 and P = 0.0005, respectively, for MIT0214, n = 78; Fig. 2B: P = 0.0014 and P = 0.023, respectively, for MITOT1, n = 73). We noted that growth of MITOT1 consistently accompanied more reduced conditions in growth medium that contained the resazurin redox indicator dye and oxidized metal supplements (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The incubation times associated with a 50% likelihood of growth in cultures inoculated with at least 1 × 104 spores/ml are 33 days for MIT0214 and 36 days for MITOT1.

FIG 2.

Logistic regressions of MIT0214 (A) and MITOT1 (B) growth outcomes under scCO2 show a significant increase in the frequency of observed growth with increasing incubation time (MIT0214, P = 0.0005; MITOT1, P = 0.023) and increasing density of spore inocula (MIT0214, P = 0.045; MITOT1, P = 0.0014). Model results predicting frequency of growth are represented by contour lines. Experimental data (MIT0214, n = 78; MITOT1, n = 73) are overlaid on top of the contours with symbol shade indicating frequency of growth and symbol size proportional to number of replicates represented by each point. Circles are cell-containing samples, and squares are no-cell controls that were entered into the model at half the detection limit (870 cells/ml).

Growth of Bacillus type strains and King Island isolates under scCO2.

After observing growth under scCO2 of isolates MIT0214 and MITOT1, we investigated whether other Bacillus strains, including subsurface isolates from the King Island site and additional Bacillus type strains, could germinate and grow under scCO2. Spores of three isolates from the King Island core (WG1, WMe1, and WMe2) and three Bacillus type strains, B. mojavensis JF-2, B. subtilis PY79, and B. cereus ATCC 14579, were inoculated into growth medium and incubated under scCO2 for 30 days. King Island isolates and Bacillus type strains yielded increased cell densities after incubation (Fig. 3A and B, respectively). However, growth patterns were variable between replicates as previously observed during experiments with strains MIT0214 and MITOT1 (Fig. 2). This unexpected result appears to indicate that the ability to grow in environments containing scCO2 may be widespread among Bacillus spp.

FIG 3.

Microscopic enumeration of cell abundance in cultures grown under scCO2 for King Island isolates (A) and three Bacillus type strains (B. subtilis PY79, B. mojavensis JF-2, and B. cereus ATCC 14579) (B). Data shown are total direct cell counts after 30 days of incubation, with horizontal lines representing initial cell counts. Initial spore densities ranged from 3.2 × 105 to 9.5 × 105 spores/ml.

Variable survival of cells and spores after exposure to scCO2.

In contrast to the observed germination and growth of spores in bioreactors containing scCO2, vegetative cells grown under aerobic conditions and ambient pressure were not able to acclimate to scCO2 exposure and grow in our experimental system. Vegetative cells from overnight stationary-phase cultures of isolate B. cereus MIT0214 and type strains B. cereus ATCC 14579, B. subtilis PY79, and B. mojavensis JF-2 were exposed to scCO2 for 6 h at 37°C. Reductions in viable cell counts of 4 to 8 orders of magnitude were observed for all strains exposed to scCO2 relative to controls incubated under ambient conditions (see Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material). Cells surviving exposure to scCO2 were most likely spores based on similar proportions of cells surviving heat-kill treatments (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

Spores from B. cereus MIT0214, B. subtilis PY79, and B. mojavensis JF-2 were robust to scCO2 exposure under both aqueous and desiccated conditions. Spores that were dried and then resuspended in aqueous buffer and exposed to scCO2 showed no significant change in viability after 2 weeks relative to the initial viable count or controls incubated under ambient conditions (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4A). While dried spores directly exposed to scCO2 were more susceptible to the killing effect, 14 to 24% of spores remained viable after 2 weeks relative to ambient-incubated controls for B. mojavensis and B. cereus (P < 0.05) and for B. subtilis (P = 0.08) (Fig. 4B). Strain B. cereus MIT0214, isolated early in the project, was used as a model scCO2-tolerant isolate for most analyses. Anecdotally, spores of strain B. subterraneus MITOT1 appeared to be less robust than spores of other Bacillus spp. tested. In the spore tolerance experiment, the pretreatment protocol to desiccate the spores resulted in total loss in viability for MITOT1, and thus, no data are available for this strain. Overall, this experiment indicated that spores from diverse Bacillus strains can withstand both direct and indirect exposure to scCO2, with enhanced survival of spores under aqueous conditions (Fig. 4; also see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material).

FIG 4.

Change in viable cell count (CFU/ml, final/initial) in spores from three Bacillus species exposed to scCO2 for 2 weeks. (A) Spores resuspended in spore preparation buffer (dark triangles) revealed no decrease in viability upon exposure to scCO2 relative to starting spore counts and ambient-atmosphere-incubated controls (open circles). B. subtilis spores may have germinated and grown during the incubation periods under ambient conditions. (B) Spores exposed to dry scCO2 (dark triangles) decreased in viability by 66 to 86%.

Growth of MIT0214 under variable CO2 and N2 pressure.

We incubated strain MIT0214 under subcritical pressures (<72.9 atm) of N2 and CO2 to observe whether more consistent growth outcomes (growth/no growth) would accompany more permissive growth conditions. At 1-atm pressure, anaerobic growth under CO2 or N2 was reproducible among triplicate incubations with increases in turbidity and viable cell counts revealing lag, log, stationary, and decline phases over a 1-week time frame (see Fig. S8A and B in the supplemental material). Considerably lower germination frequencies were observed under 1-atm CO2 (<19%) than 1-atm N2 (>99%) (see Fig. S8A in the supplemental material). In contrast to reproducible growth observed at ambient pressure, growth at all pressures above 1 atm under either N2 or CO2 revealed positive growth but variability in outcome (i.e., growth/no-growth) between replicates over 1- and 2-week time frames, respectively, similar to the variability observed for cultures incubated under scCO2 (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that bacterial growth under an scCO2 atmosphere is possible using strains isolated through enrichment cultivation of samples from three sites targeted for geologic sequestration of CO2: filtrate samples from the Frio-2 project in Texas; consolidated rock cores from the Paaratte formation in the Otway Basin, Australia; and an unconsolidated core from the Mokelumne formation at the King Island site in California. In addition, we observed germination and growth under scCO2 of three Bacillus type strains isolated from subsurface (B. mojavensis JF-2) and surface (B. subtilis PY79 and B. cereus ATCC 14579) environments. These observations of microbial growth under scCO2 have several implications for geological carbon dioxide sequestration (GCS). (i) Microbial survival and activity are possible, and perhaps likely, at the CO2 plume-water interface, even in areas previously exposed to pure-phase scCO2. (ii) Engineering biofilm barriers or stimulating biomineralization in situ at the CO2 plume-water interface may be feasible, despite previously documented lethal properties of scCO2 for nonacclimated microorganisms. (iii) Organisms likely to survive and proliferate after CO2 injection include spore-forming microbes that can withstand the initial CO2 stresses.

Phylogenetic and physiological analyses reveal that strains isolated from the three GCS sites are similar to previously described Bacillus isolates that are readily cultured copiotrophs. Anaerobic enrichment medium formulations, although supplemented to target diverse metabolic groups, contained a base of organic carbon (yeast extract and peptone), potentially explaining the dominance of Bacillus spp. in our enrichments. While the catabolic pathways for different strains recovered were not determined in this study, previous studies suggest that closely related Bacillus spp. may grow anaerobically by fermentation and/or anaerobic respiration. Strain MIT0214 is most closely related to B. cereus—a widely distributed bacterium that has been isolated from a diverse range of environments, including sites characterized by heavy metals, deep oil reservoirs, and/or hypersaline conditions (42–45). Strain MITOT1 is closely related to strains B. subterraneus and Bacillus infernus, both of which were isolated from deep subsurface environments (46, 47). King Island isolates are closely related to strains of B. megaterium, B. safensis, and B. amyloliquefaciens, which have all been isolated from diverse terrestrial environments (48–53). In light of the diversity of Bacillus strains able to grow under scCO2, we hypothesize that the ability to grow under high pCO2 is a widespread feature of Bacillus spp. and possibly other organisms.

All Bacillus spp. isolated in this study were sporeformers capable of facultative anaerobic growth under both N2 and CO2 atmospheres. Notably, we have observed that all strains exhibit the fastest growth under aerobic conditions and atmospheric pressure but are also able to grow anaerobically at elevated pressures beyond the critical point for CO2 (greater than 37°C and 73 atm). Growth dynamics of strain MIT0214 at 1 atm are consistent with anaerobic growth via fermentation where end product inhibition leads to a reduction of cell and spore viability in stationary phase (see Fig. S8A and B in the supplemental material). In strain MITOT1, the observed change in culture oxidation state that accompanied cell growth (as demonstrated by the resazurin indicator) suggests that MITOT1 may be capable of Fe(III) or Mn(IV) reduction (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material), although whether oxidation state changes occur via fermentation or respiration has not been established in this study. We note that several close phylogenetic relatives of strain MITOT1 are anaerobic metal reducers capable of Fe(III), Mn(IV), Se(VI), and As(V) respiration (46, 47, 54).

Spores of three Bacillus strains, including isolate B. cereus MIT0214, are tolerant of both direct and indirect exposure to scCO2. Direct exposure of dried spores to scCO2 proved to be a more severe stress, resulting in a 66 to 86% loss in spore viability over a 2-week interval, while no significant loss was observed in spores indirectly exposed via aqueous phase (Fig. 4; also see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). The decrease in viability of spores directly exposed to scCO2 may be due to its solvating and desiccating properties, as spores in the aqueous phase do not experience the same degree of contact with scCO2 and are protected from dehydration. While it remains to be determined whether the viability decrease is time dependent, our observation of a decrease of <1 order of magnitude in survival of desiccated spores exposed to scCO2 suggests that spores in subsurface environments will likely be able to tolerate at least brief periods of direct exposure to pure-phase scCO2. This finding is especially relevant in the GCS context because as buoyant scCO2 migrates toward the cap-rock interface, spores may experience fluctuations in scCO2 contact in areas where formation fluids have been displaced, creating local areas of more extreme and desiccating conditions. Persistence of a subpopulation of spores after direct scCO2 exposure suggests that scCO2 injection during GCS may not effectively sterilize the subsurface, enabling the resumption of microbial activities upon return of an aqueous phase. Our results, and previous demonstrations of spore resistance to scCO2 sterilization (9), suggest that spore-forming microbial taxa may be able to survive and acclimate to in situ conditions post-CO2 injection during geologic carbon dioxide sequestration.

Previous work suggests that several features of Bacillus physiology are likely responsible for the variable, but predictable, time- and density-dependent growth observed under scCO2. First, germination frequencies under CO2 headspaces are known to be significantly lower than those under aerobic or anaerobic nitrogen headspaces, with only 10 to 30% of B. cereus spores germinating under 1 atm CO2 (55). Growth dynamics for isolate B. cereus MIT0214 (see Fig. S8A in the supplemental material) were consistent with these findings, displaying a germination frequency at 1 atm CO2 no greater than 19%, in contrast to a 99% germination frequency under 1 atm N2 (see Fig. S8A in the supplemental material). Second, it has been shown that certain stresses, such as pH and oxidative stresses, significantly extend the lag time for germination of Bacillus spores (55, 56). We have observed extended lag phases for growth of MIT0214 under 1 atm CO2 compared to 1 atm N2 (see Fig. S8A and B in the supplemental material) and have also observed extended lag times for growth of all isolates at low pH (pH <6) (data not shown) during physiological tests (Table 3). The third mechanism that may explain the observed variability in growth has been termed the “microbial scout hypothesis,” where activation of cells from dormant bacterial populations (e.g., spores) is stochastic but occurs at a constant low frequency (i.e., ∼0.01% per day) independent of environmental cues. This behavior would allow a clonal population to sense and respond to permissive growth conditions without risking activation of the entire dormant population (57). Fourth, it has been shown that modulation of the sporulation conditions has a significant effect on spore physiology and resistance to stress (58, 59), and we suggest that a population of spores may contain a range of this physiological plasticity where some, but not all, spores are able to grow following germination under stressful conditions. Finally, microenvironments within cultures (e.g., associated with biofilms or mineral surfaces) may influence the degree to which cells are exposed to stresses associated with scCO2 (17, 60). Thus, variability in exposure and stress tolerance of spores in combination with extended lag times under conditions of high pCO2 and low pH, and inherently stochastic and suppressed germination frequencies, may account for observed variability of growth under scCO2.

Microbial biomass obtained from ongoing GCS projects supports the notion that spore-forming Firmicutes populations, such as Bacillus spp., persist and potentially grow in the subsurface after scCO2 injection. Recovery of phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) from Frio-2 groundwater samples indicated the presence of viable microorganisms after CO2 injection, especially Firmicutes, as indicated by the observation of characteristic terminally branched saturated fatty acids. In particular, i15:0, i17:0, and a17:0, which are prominent fatty acids in B. cereus (61, 62), were observed in the sample from the Frio-2 project from which B. cereus strain MIT0214 was isolated and in samples following CO2 breakthrough (S. Pfiffner, personal communication). Microbial communities recovered in formation waters of the Otway Basin (Australia) and Ketzin (Germany) GCS sites (10 to 12 days and 2 days to 10 months post-CO2 injection, respectively) include taxa of the Firmicutes (e.g., Bacilli and Clostridia) among the detectable diversity. Finally, in experimental incubation of formation fluids under scCO2, enrichment of Firmicutes (Clostridiales) was observed after removal of scCO2, demonstrating the resilience of native Firmicutes populations to scCO2 exposure (63).

While some populations of Bacillus are well established as members of subsurface biospheres (46, 47), others may be introduced to the subsurface through drilling activities. Although sampling methods for Frio-2 formation water and Otway cores were designed to reduce the possibility of drilling fluid contamination through use of a U-tube sampling device (33) or fluorescein drilling fluid penetration data, respectively, drilling activities remain a potential source for some of the strains recovered in this study. Indeed, the King Island core, which yielded the highest number of scCO2-tolerant isolates, was unconsolidated sandstone and fully penetrated by drilling fluid based on tracer data. Notably, drilling fluid characterized by Mu et al. (22) was dominated by sequences of Bacilli.

High concentrations of local dissolved organic carbon at the edges of injected CO2 plumes, as observed during the Frio-2 project (29, 64), may stimulate growth of native or introduced bacteria. Enrichment of dissolved organic carbon near the plume may be due to extraction of the subsurface organic matrix by the nonpolar solvent-like properties of scCO2. We suggest that these enrichments of dissolved organic carbon at the leading edge of the CO2 plume may serve as potential hot spots for microbial activity fueled by anaerobic metabolism. Previous observations that DNA and lipid biomass from Firmicutes populations persist in scCO2-exposed environments (21, 22), coupled with the presented evidence that a diverse set of Bacillus strains and isolates may grow in the presence of scCO2, water, and nutrients, suggest that microbially mediated processes may continue to occur up to the scCO2 plume-water interface during geologic carbon dioxide sequestration. Understanding how CO2 injection shifts the balance of microbial community structure, metabolic potential, and associated biogeochemical processes is therefore necessary to predict the long-term fate of injected CO2.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tommy Phelps and Susan Pfiffner for providing access to Frio-2 samples, for sharing associated data, and for helpful comments throughout the project. We are grateful to Peter Cook for arranging access to Otway samples through the CO2CRC project and to Joanne Emerson for collection of core materials from the King Island site. In addition, we thank Martin Polz for feedback on the manuscript, Eric D. Hill for advice on statistical analyses, and Roger Summons and Mike Timko for project advice.

Funding for experimental work was provided to J.R.T. by the Department of Energy Office of Fossil Energy under award number DE-FE0002128 and by the MIT Energy Initiative. C.B. published with the permission of the CEO, Geoscience Australia. Drilling and coring activities were carried out through the Frio-2 project (U.S. Department of Energy), CO2CRC project (Australian Government), and the WESTCARB project at King Island (U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231; secondary sampling supported by the Center for Nanoscale Control of Geologic CO2, an Energy Frontier Research Center, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy under award number DE-AC02-05CH11231).

This publication was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof.

The authors declare no conflict of interest with this work.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03162-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Metz B, Davidson O, De Coninck H, Loos M, Meyer L (ed). 2005. The IPCC special report on carbon dioxide capture and storage. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lal R. 2008. Carbon sequestration. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 363:815–830. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onstott TC. 2005. Impact of CO2 injections on deep subsurface microbial ecosystems and potential ramifications for the surface biosphere, p 1217–1249. In Benson SM. (ed), Carbon dioxide capture for storage in deep geologic formation—results from the CO2 capture project, vol 2 Geologic storage of carbon dioxide with monitoring and verification Elsevier, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kieft TL, McCuddy SM, Onstott TC, Davidson M, Lin L-H, Mislowack B, Pratt L, Boice E, Lollar BS, Lippmann-Pipke J, Pfiffner SM, Phelps TJ, Gihring T, Moser D, Heerden AV. 2005. Geochemically generated, energy-rich substrates and indigenous microorganisms in deep, ancient groundwater. Geomicrobiol J 22:325–335. doi: 10.1080/01490450500184876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapelle FH, O'Neill K, Bradley PM, Methé BA, Ciufo SA, Knobel LL, Lovley DR. 2002. A hydrogen-based subsurface microbial community dominated by methanogens. Nature 415:312–315. doi: 10.1038/415312a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavalleur HJ, Colwell FS. 2013. Microbial characterization of basalt formation waters targeted for geological carbon sequestration. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 85:62–73. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaus I. 2010. Role and impact of CO2-rock interactions during CO2 storage in sedimentary rocks. Int J Greenhouse Gas Control 4:73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijggc.2009.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillow A, Dehghani F, Hrkach J, Foster N. 1999. Bacterial inactivation by using near- and supercritical carbon dioxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:10344–10348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Davis T, Matthews M, Drews M, LaBerge M, An Y. 2006. Sterilization using high-pressure carbon dioxide. J Supercrit Fluids 38:354–372. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2005.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu B, Shao H, Wang Z, Hu Y, Tang Y, Jun Y. 2010. Viability and metal reduction of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 under CO2 stress: implications for ecological effects of CO2 leakage from geologic CO2 sequestration. Environ Sci Technol 44:9213–9218. doi: 10.1021/es102299j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertoloni G, Bertucco A, De Cian V, Parton T. 2006. A study on the inactivation of micro-organisms and enzymes by high pressure CO2. Biotechnol Bioeng 95:155–160. doi: 10.1002/bit.21006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong S, Pyun Y. 1999. Inactivation kinetics of Lactobacillus plantarum by high pressure carbon dioxide. J Food Sci 64:728–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1999.tb15120.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spilimbergo S, Mantoan D, Quaranta A, Della Mea G. 2009. Real-time monitoring of cell membrane modification during supercritical CO2 pasteurization. J Supercrit Fluids 48:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2008.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamihira M, Taniguchi M, Kobayashi T. 1987. Sterilization of microorganisms with supercritical carbon dioxide. Agric Biol Chem 51:407–412. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.51.407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell AC, Phillips AJ, Hamilton MA, Gerlach R, Hollis WK, Kaszuba JP, Cunningham AB. 2008. Resilience of planktonic and biofilm cultures to supercritical CO2. J Supercrit Fluids 47:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2008.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballestra P, Cuq J-L. 1998. Influence of pressurized carbon dioxide on the thermal inactivation of bacterial and fungal spores. LWT Food Sci Technol 31:84–88. doi: 10.1006/fstl.1997.0299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santillan EU, Kirk MF, Altman SJ, Bennett PC. 2013. Mineral influence on microbial survival during carbon sequestration. Geomicrobiol J 30:578–592. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2013.767396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirk MF. 2011. Variation in energy available to populations of subsurface anaerobes in response to geological carbon storage. Environ Sci Technol 45:6676–6682. doi: 10.1021/es201279e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayumi D, Dolfing J, Sakata S, Maeda H, Miyagawa Y, Ikarashi M, Tamaki H, Takeuchi M, Nakatsu CH, Kamagata Y. 2013. Carbon dioxide concentration dictates alternative methanogenic pathways in oil reservoirs. Nat Commun 4:1998. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohtomo Y, Ijiri A, Ikegawa Y, Tsutsumi M, Imachi H, Uramoto G-I, Hoshino T, Morono Y, Sakai S, Saito Y, Tanikawa W, Hirose T, Inagaki F. 2013. Biological CO2 conversion to acetate in subsurface coal-sand formation using a high-pressure reactor system. Front Microbiol 4:361. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morozova D, Zettlitzer M, Let D, Würdemann H, CO2SINK Group. 2011. Monitoring of the microbial community composition in deep subsurface saline aquifers during CO2 storage in Ketzin, Germany. Energy Procedia 4:4362–4370. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2011.02.388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mu A, Boreham C, Leong HX, Haese RR, Moreau JW. 2014. Changes in the deep subsurface microbial biosphere resulting from a field-scale CO2 geosequestration experiment. Front Microbiol 5:209. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell AC, Phillips AJ, Hiebert R, Gerlach R, Spangler LH, Cunningham AB. 2009. Biofilm enhanced geologic sequestration of supercritical CO2. Int J Greenhouse Gas Control 3:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijggc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenneman GE, McInerney MJ, Knapp RM, Clark JB, Feero JM, Revus DE, Menzie DE. 1983. Halotolerant, biosurfactant-producing Bacillus species potentially useful for enhanced oil recovery. Dev Ind Microbiol 24:485–492. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMahon P, Chapelle F. 1991. Microbial production of organic acids in aquitard sediments and its role in aquifer geochemistry. Nature 349:233–235. doi: 10.1038/349233a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferris FG, Stehmeier LG, Kantzas A, Mourits FM. 1996. Bacteriogenic mineral plugging. J Can Pet Technol 35(8):56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barker W, Welch S, Chu S, Banfield J. 1998. Experimental observations of the effects of bacteria on aluminosilicate weathering. Am Mineral 83:1551–1563. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell A, Dideriksen K, Spangler L, Cunningham A, Gerlach R. 2010. Microbially enhanced carbon capture and storage by mineral-trapping and solubility-trapping. Environ Sci Technol 44:5270–5276. doi: 10.1021/es903270w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hovorka SD, Benson SM, Doughty C, Freifeld BM, Sakurai S, Daley TM, Kharaka YK, Holtz MH, Trautz RC, Nance HS, Myer LR, Knauss KG. 2006. Measuring permanence of CO2 storage in saline formations: the Frio experiment. Environ Geosci 13:105–121. doi: 10.1306/eg.11210505011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma S, Cook P, Jenkins C, Steeper T, Lees M, Ranasinghe N. 2011. The CO2CRC Otway project: leveraging experience and exploiting new opportunities at Australia's first CCS project site. Energy Procedia 4:5447–5454. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2011.02.530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dance T, Spencer L, Xu J-Q. 2009. Geological characterisation of the Otway project pilot site: what a difference a well makes. Energy Procedia 1:2871–2878. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2009.02.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Downey C, Clinkenbeard J. 2010. Preliminary geologic assessment of the carbon sequestration potential of the Upper Cretaceous Mokelumne River, Starkey, and Winters Formations—Southern Sacramento Basin, California: PIER collaborative report. California Energy Commission, Sacramento, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freifeld BM, Trautz RC, Kharaka YK, Phelps TJ, Myer LR, Hovorka SD, Collins DJ. 2005. The U-tube: a novel system for acquiring borehole fluid samples from a deep geologic CO2 sequestration experiment. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 110:B110. doi: 10.1029/2005JB003735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colwell F, Onstott T, Delwiche M, Chandler D, Fredrickson J, Yao Q, McKinley J, Boone D, Griffiths R, Phelps T, Ringelberg D, White D, LaFreniere L, Balkwill D, Lehman R, Konisky J, Long P. 1997. Microorganisms from deep, high temperature sandstones: constraints on microbial colonization. FEMS Microbiol Rev 20:425–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00327.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roth M. 1998. Helium head pressure carbon dioxide in supercritical fluid extraction and chromatography: thermodynamic analysis of the effects of helium. Anal Chem 70:2104–2109. doi: 10.1021/ac971168e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Setlow P. 2006. Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to and killing by radiation, heat and chemicals. J Appl Microbiol 101:514–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lessard PA, O'Brien XM, Currie DH, Sinskey AJ. 2004. pB264, a small, mobilizable, temperature sensitive plasmid from Rhodococcus. BMC Microbiol 4:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, Fish J, Chai B, Farris RJ, Kulam-Syed-Mohideen AS, McGarrell DM, Marsh T, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM. 2009. The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D141–D145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard J-F, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, Claverie J-M, Gascuel O. 2008. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W465–W469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim H, Goepfert J. 1974. A sporulation medium for Bacillus anthracis. J Appl Microbiol 37:265–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashby GK. 1938. Simplified Schaeffer spore stain. Science 87:443. doi: 10.1126/science.87.2263.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiong Z, Jiang Y, Qi D, Lu H, Yang F, Yang J, Chen L, Sun L, Xu X, Xue Y, Zhu Y, Jin Q. 2009. Complete genome sequence of the extremophilic Bacillus cereus strain Q1 with industrial applications. J Bacteriol 191:1120–1121. doi: 10.1128/JB.01629-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh SK, Tripathi VR, Jain RK, Vikram S, Garg SK. 2010. An antibiotic, heavy metal resistant and halotolerant Bacillus cereus SIU1 and its thermoalkaline protease. Microb Cell Fact 9:59. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pandey S, Saha P, Biswas S, Maiti TK. 2011. Characterization of two metal resistant Bacillus strains isolated from slag disposal site at Burnpur, India. J Environ Biol 32:773–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sriram MI, Kalishwaralal K, Deepak V, Gracerosepat R, Srisakthi K, Gurunathan S. 2011. Biofilm inhibition and antimicrobial action of lipopeptide biosurfactant produced by heavy metal tolerant strain Bacillus cereus NK1. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 85:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanso S, Greene A, Patel B. 2002. Bacillus subterraneus sp. nov., an iron-and manganese-reducing bacterium from a deep subsurface Australian thermal aquifer. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52:869–874. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.01842-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boone D, Liu Y, Zhao Z, Balkwill D, Drake G, Stevens T, Aldrich H. 1995. Bacillus infernus sp. nov., an Fe(III)- and Mn(IV)-reducing anaerobe from the deep terrestrial subsurface. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 45:441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vary PS, Biedendieck R, Fuerch T, Meinhardt F, Rohde M, Deckwer W-D, Jahn D. 2007. Bacillus megaterium—from simple soil bacterium to industrial protein production host. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 76:957–967. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mori T, Sakimoto M, Kagi T, Sakai T. 1996. Isolation and characterization of a strain of Bacillus megaterium that degrades poly(vinyl alcohol). Bioscience 60:330–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raja CE, Omine K. 2012. Arsenic, boron and salt resistant Bacillus safensis MS11 isolated from Mongolia desert soil. Afr J Biotechnol 11:2267–2275. doi: 10.5897/AJB11.3131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Satomi M, La Duc MT, Venkateswaran K. 2006. Bacillus safensis sp. nov., isolated from spacecraft and assembly-facility surfaces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 56:1735–1740. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Idriss EE, Makarewicz O, Farouk A, Rosner K, Greiner R, Bochow H, Richter T, Borriss R. 2002. Extracellular phytase activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB45 contributes to its plant-growth-promoting effect. Microbiology 148:2097–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida S, Hiradate S, Tsukamoto T, Hatakeda K, Shirata A. 2001. Antimicrobial activity of culture filtrate of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens RC-2 isolated from mulberry leaves. Phytopathology 91:181–187. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2001.91.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamura S, Yamashita M, Fujimoto N, Kuroda M, Kashiwa M, Sei K, Fujita M, Ike M. 2007. Bacillus selenatarsenatis sp. nov., a selenate- and arsenate-reducing bacterium isolated from the effluent drain of a glass-manufacturing plant. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 57:1060–1064. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64667-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Setlow B, Yu J, Li YQ, Setlow P. 2013. Analysis of the germination kinetics of individual Bacillus subtilis spores treated with hydrogen peroxide or sodium hypochlorite. Lett Appl Microbiol 57:259–265. doi: 10.1111/lam.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee JK, Movahedi S, Harding SE, Waites WM. 2003. The effect of acid shock on sporulating Bacillus subtilis cells. J Appl Microbiol 94:184–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buerger S, Spoering A, Gavrish E, Leslin C, Ling L, Epstein SS. 2012. Microbial scout hypothesis, stochastic exit from dormancy, and the nature of slow growers. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:3221–3228. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07307-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Russell AD. 1990. Bacterial spores and chemical sporicidal agents. Clin Microbiol Rev 3:99–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Condon S, Bayarte M, Sala FJ. 1992. Influence of the sporulation temperature upon the heat resistance of Bacillus subtilis. J Appl Bacteriol 73:251–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb02985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stewart PS, Franklin MJ. 2008. Physiological heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:199–210. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaneda T. 1972. Positional preference of fatty acids in phospholipids of Bacillus cereus and its relation to growth temperature. Biochim Biophys Acta 280:297–305. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(72)90097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haque M, Russell N. 2004. Strains of Bacillus cereus vary in the phenotypic adaptation of their membrane lipid composition in response to low water activity, reduced temperature and growth in rice starch. Microbiology 150:1397. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26767-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frerichs J, Rakoczy J, Ostertag-Henning C, Krüger M. 2014. Viability and adaptation potential of indigenous microorganisms from natural gas field fluids in high pressure incubations with supercritical CO2. Environ Sci Technol 48:1306–1314. doi: 10.1021/es4027985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kharaka YK, Cole DR, Thordsen JJ, Kakouros E, Pfiffner SM, Hovorka SD. 2006. Environmental implications of toxic metals and dissolved organics released as a result of CO2 injection into the Frio Formation, Texas, USA, p 214–218. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Site Characterization for CO2 Geologic Storage, 20 to 22 March 2006, Berkeley, CA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.