Abstract

Diarrhea is the second leading cause of child mortality in India. Most deaths are cheaply preventable with the use of oral rehydration salts (ORS), yet many health providers still fail to provide ORS to children seeking diarrheal care. In this study, we use survey data to assess whether children visiting private providers for diarrheal care were less likely to use ORS than those visiting public providers. Results suggest that children who visited private providers were 9.5 percentage points less likely to have used ORS than those who visited public providers (95% CI 5–14). We complimented these results with in-depth interviews of 21 public and 17 private doctors in Gujarat, India, assessing potential drivers of public–private disparities in ORS use. Interview results suggested that lack of direct medication dispensing in the private sector might be a key barrier to ORS use in the private sector.

Keywords: private sector, India, ORS, ORT, child health, global health, child diarrhea

INTRODUCTION

Diarrheal diseases are the second leading cause of death in India for children under 5 years old [1]. Nearly all of these deaths are from dehydration, which is cheaply preventable with the use of oral rehydration salts (ORS) [2–6]. Despite the success of ORS in reducing child mortality [7, 8], usage rates in India remain dangerously low [9, 10].

One explanation for low usage of ORS is the lack of access to health infrastructure, making acquisition of ORS difficult. However, over 60% of children with diarrhea visit a health provider, and only 40% of these children are treated with ORS [11]. Evidently, even when children have access to health care, many diarrheal cases still fail to be treated with ORS.

There are several barriers that may lead health-care providers to underprovide ORS. First, due to supply and distribution issues, ORS might not always be available [12, 13]. Second, providers might not have adequate knowledge of treatment guidelines and regulation of treatment is inadequate [14–16]. Third, providers that directly dispense medicines may prefer to sell treatments with larger profit margins. Since ORS is relatively inexpensive and is often subsidized at government facilities, private providers may have limited ability to generate profit from ORS relative to other treatments [17–19]. Fourth, although ORS effectively treats the dehydration resulting from diarrhea, it does not reduce the volume of diarrhea, which may instill a false perception that ORS is not efficacious [20–22].

Several studies suggest that private providers perform worse than public providers in adhering to public health guidelines, and barriers to using ORS might be stronger in the private sector [23, 24]. One recent study shows that in sub-Saharan Africa, private providers were 22% less likely to treat child diarrhea with ORS than public providers [25]. Other studies show similar findings [26–28]. However, no study to date has assessed public–private differences in ORS use in India, where a quarter of all diarrheal mortalities occur and over 75% of diarrheal cases seeking treatment are handled by the private sector [11]. Moreover, prior work has not assessed potential drivers of public–private differences in diarrheal treatment, and there remains a deficient understanding of why such differences occur.

This study is the first to assess public–private differences in ORS use in India. We did so using a mixed-methods approach. In the first phase, we used India Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data to assess public–private differences in ORS use at the national level. In the second phase, we conducted a health provider survey in Gujarat, India, to qualitatively assess potential mechanisms of public–private differences.

METHODS

Phase 1: Public–private differences in ORS use

Data and sample:

We used DHS data for 2679 children from all 28 states of India. The DHSs are nationally representative household surveys. We used child-level DHS data (aged 0–59 months), and included only children who had a diarrhea episode in the prior 2 weeks (10% of all children) and sought treatment from health providers including hospitals, clinics, pharmacies and private doctors.

Diarrheal treatment:

Appropriate diarrheal treatment should include some form of oral rehydration therapy, regardless of the illness severity [29]. We distinguished between three categories of diarrheal treatment as reported by mothers. The first represented whether the child was treated with ORS. The second represented whether the child received any non-ORS medication—pills/syrups, antibiotics, injections, herbal remedy and antimotility medicines—many of which are unnecessary and often harmful. However, if non-ORS medications are provided along with ORS, then this may not be a problem in regards to preventing dehydration-related mortality. To address this, the third category represented whether a child received any non-ORS medication without receiving ORS. In some cases, other treatments can be provided in compliment to ORS, but besides other forms of rehydration, no treatments should be provided in place of ORS [30].

Facility ownership:

We used mother reports to identify whether children went to private-for-profit providers, public providers and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). We separately analyzed for-profit providers and private NGOs, as they might have had different incentives for providing ORS.

Analysis approach:

We used probit models to assess the relationship between provider ownership and the probability of receiving each treatment category. We controlled for a range of confounders that may have affected both the facility choice and the probability of receiving different types of diarrheal treatment. Child and household controls included child’s age and gender, whether the child had a cough or fever in addition to diarrhea, height-for-age (a proxy for stunting), weight-for-age (a proxy for underweight), mother’s age and education, gender of household head, number of children in the family, household drinking water source and household wealth. We controlled for wealth using quintiles of the DHS wealth index, a composite measure of a household’s cumulative living standard [31]. We controlled for treatment facility type since the composition of facility types may be different between the private and public sectors. We controlled for geographic confounders by including a rural/urban indicator variable and a set of indicators for each state.

We used the model to estimate the probability that a child received each treatment category if he/she visited a for-profit private facility or a public facility while holding all other factors constant. Standard errors were estimated using the delta method and clustered at the state level. In accordance with DHS recommendations, we did not use sampling weights in the regression models presented [32].

Phase 2: Provider survey

The second phase of this study aimed to better understand potential sources of low usage of ORS in the private sector. We conducted a health provider survey in Gujarat, India—a state with particularly high rates of child diarrhea and large public–private differences in the ORS use—where we interviewed 17 private and 21 public health providers. Facilities were chosen based on a convenience sample of contacts acquired by the research team. We asked respondents a series of questions on facility resources, services provided, preferred methods of diarrhea treatment and barriers to providing ORS. In addition, the interview included a vignette describing a case of viral diarrhea, and respondents were asked to detail the treatment course they would recommend. Cases of viral diarrhea should be treated with ORS and not antibiotics.

RESULTS

Phase 1 results

In all, 23% of children visited public facilities, 76% visited for-profit private facilities and 0.4% visited NGO facilities (Table 1). Private doctors were the most frequently visited type of provider (44%). Government hospitals were the most frequently visited public facilities. Since so few children visited NGO facilities, we exclude them from the rest of the results discussion.

Table 1.

Distribution of facility types used for diarrheal treatment

| Facility type | Frequency | Total % |

|---|---|---|

| Within sector % | ||

| Public | 625 | 23% |

| Dispensary | 55 | 9% |

| Government hospital | 508 | 81% |

| Government sub center | 49 | 8% |

| Other public sector | 13 | 2% |

| For-Profit private | 2042 | 76% |

| Private hospital/clinic | 385 | 19% |

| Pharmacy | 274 | 13% |

| Private doctor | 1181 | 58% |

| Other private sector | 202 | 10% |

| NGO | 12 | 0.4% |

| NGO health facility | 12 | 100% |

| Total | 2679 |

Table 2 presents mean characteristics by whether the child visited a for-profit or public provider. Children that visited for-profit providers were less likely to receive ORS and more likely to receive non-ORS medications without ORS. Also, children who visited for-profit private providers were more likely to have had a fever, less likely to have been stunted, had more access to protected water sources and were from wealthier households.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of child characteristics by ownership type of facility where treatment was sought

| Dependent variable | For-profit private (n = 2042) | Public (n = 637) |

|---|---|---|

| ORS | 36%*** | 52% |

| Other treatments | 63% | 60% |

| Other treatments & no ORS | 41%** | 31% |

| Rural | 56%*** | 67% |

| Age of child (Months) | 21.8 | 22.5 |

| Male | 56% | 56% |

| Number of children in HH | 1.83** | 1.72 |

| Age of mother | 26.0 | 25.8 |

| Female household head | 11% | 11% |

| Education of mother | ||

| No education | 37% | 35% |

| Primary | 13% | 15% |

| Secondary | 50% | 49% |

| Health of child | ||

| Fever in prior 2 weeks | 39%** | 33% |

| Cough in prior 2 weeks | 38% | 36% |

| Severely stunteda | 13%* | 16% |

| Moderately stuntedb | 19% | 20% |

| Severely underweightc | 12%** | 16% |

| Moderately underweightd | 26% | 24% |

| Source of water | ||

| Piped water | 41% | 42% |

| Protected well/borehole | 40%*** | 32% |

| Unprotected well/natural source | 19%*** | 26% |

| Wealth status | ||

| Poorest | 13% | 15% |

| Poorer | 16%** | 20% |

| Middle | 20%*** | 27% |

| Richer | 26% | 24% |

| Richest | 26%*** | 14% |

Statistical significance is assessed using ordinary least squares, regressing each dependent variable on for-profit private and NGO with the public sector as the reference, thus testing whether characteristics of for-profit private and NGO characteristics are statistically different from public sector characteristics.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05, standard errors are clustered at the country level.

aHeight for age z-score ≤−3.

bHeight for age z-score >−3 & ≤−2.

cWeight for age z-score ≤−3.

dWeight for age z-score >−3 & ≤−2.

After adjusting for confounders, children that went to the private sector were 9.5 percentage points less likely to receive ORS (95% CI 5%–14%) (Table 3). We found no statistical difference in the use of non-ORS medications with or without ORS, although the direction of the difference was consistent with unadjusted results.

Table 3.

Probability of treatment by ownership type

| Type of Treatment | For-profit private | Public | Differencea (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORS | 37.4% | 46.9% | −9.5%*** (−14, −5) |

| Other treatments | 61.6% | 65.1% | −3.5% (−8, 1) |

| Other treatments & No ORS | 40.0% | 36.7% | 3.2% (−1, 8) |

aDifferences are average marginal effects.

Probabilities are predicted from probit regressions, each controlling for child age, sex of child, child health, mother’s age, number of children in the household, if the mother was the head of the household, access to clean water, wealth, rural/urban, facility type, country-region, and year.

Standard errors were estimated using the delta method and clustered at the state level.

N = 2675.

***p < 0.01.

Phase 2 results

We interviewed 21 public doctors and 17 private doctors in Gujarat, India. Gujarat had a particularly large public–private difference in ORS use—29.1 percentage points, the 5th largest difference we found of all Indian states.

All private doctors reported treating patients that had ‘middle’ or ‘high’ income, whereas two-thirds of public doctors reported treating patients with ‘low-income’. On average, public and private doctors reported a similar number of patients and diarrheal cases per week. Most private doctors ran small practices, often out of their homes. Public doctors on the other hand generally worked at larger, multi-doctor facilities.

Contrary to expectations, there was no evidence that private doctors were any less likely than public doctors to prescribe ORS. All providers, both public and private, reported ORS as a key element to their treatment plan for a child with diarrhea. All doctors also accurately reported only using antibiotics for bacterial diarrhea. Moreover, almost all doctors, public and private, reported that they did not believe private doctors would be any less likely to prescribe ORS.

These findings were echoed in the vignette. All doctors, both public and private, correctly diagnosed the hypothetical case in the vignette as viral diarrhea and indicated that they would treat this case with ORS.

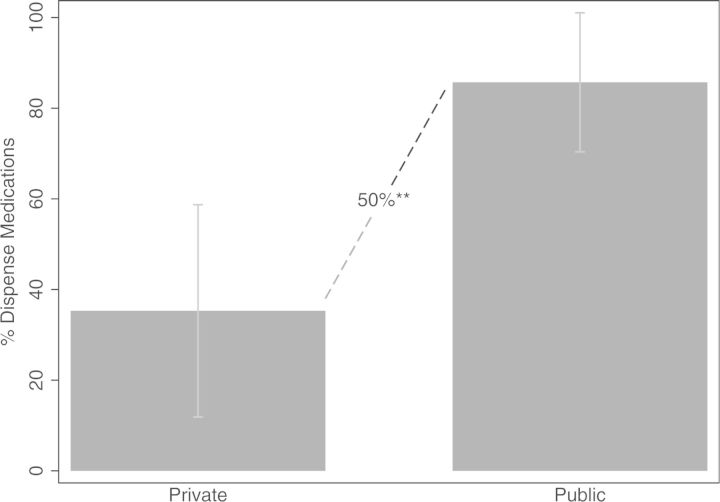

One key difference found between public and private doctors was that private doctors were much less likely to dispense medications (See Fig. 1). In all, 85% of public doctors dispensed medications at their facility, whereas only 35% of private sector doctors dispensed medications (p < 0.05). This creates an extra barrier for patients seeking care in the private sector, requiring an additional trip to a pharmacy and might explain why public–private differences in ORS use exist, although preferred treatment plans are similar. Several private doctors interviewed noted that, although they recommend ORS to their patients, they have no way of knowing if patients ever retrieved the treatment.

Fig. 1.

Share of facilities that dispensed their own medications.

If our suggestion that lack of dispensation of medications is a reason for the underuse of ORS is valid, we would expect to find lower ORS use among children who sought care from private doctors—whom generally do not dispense medications—relative to private hospitals—where medications are usually dispensed. Indeed, in the DHS we found that only 36% of children who sought care from private doctors received ORS relative to 49% of children that sought care from private hospitals (p < 1%).

DISCUSSION

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that children that seek diarrheal care from private providers are less likely to be treated with ORS than children that seek care from public providers [25–28]. In this study, we show that this problem is also present in India. However, our provider interviews show no evidence that private doctors are any less likely to prescribe ORS for child diarrhea. Instead, the survey suggests that lack of dispensation of medications by private doctors might explain why children that seek care from private doctors are less likely to receive ORS.

Private doctors in India tend to be small scale, single doctor establishment, which might be why they are less likely to dispense medication. These doctors do not benefit from economies of scale and may not have the time or expertise to navigate the Indian drug supplier network.

There are several reasons why seeking care from doctors that do not dispense medication decreases the probability that a child receives ORS. First, the requirement of going to an additional facility to retrieve ORS creates an extra barrier for parents, creating more opportunity to decide to forgo the purchase of ORS. Second, parents may be more inclined to purchase ORS for their child when they are still in a doctor’s presence. Finally, even if parents visit a pharmacy to retrieve treatments, pharmacists may have a preference for selling more profitable treatments than ORS [17].

The results of this study suggest that interventions to improve ORS use in the private sector should focus on closing the gap between ORS prescription rates and ORS usage rates. One way of doing this could be through public sector or donor provision of ORS to private doctors for direct dispensation. Other ways could involve encouraging parents to place more value on ORS retrieval through informational campaigns that emphasize the importance of ORS or rewards to parents for retrieving ORS. The latter method has worked for childhood immunizations in India in the past [33].

This study is not without limitations. First, our results are based on self-report data, which could suffer from measurement error. Second, our sample of doctors for the qualitative interviews was small and not randomly selected. Future work should conduct a similar survey with a larger, more representative sample. Third, this survey recorded stated behavior, which may be inconsistent with the actual behavior. Some providers might overstate the frequency of ORS prescription to appease interviewers. Fourth, our analysis of DHS data could be biased by unobservable confounders that affect both facility choice and ORS use.

Underuse of ORS is a key driver of child mortality in India. This study is the first to suggest that underuse may arise from lack of medication dispensation among private doctors. These findings have crucial implications for increasing ORS use in India.

FUNDING

National Institute on Aging (T32-AG000246).

REFERENCES

- 1.Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1969–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cash RA, Nalin DR, Rochat R, et al. A clinical trial of oral therapy in a rural cholera-treatment center. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1970;19:653–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierce NF, Sack RB, Mitra RC, et al. Replacement of water and electrolyte losses in cholera by an oral glucose-electrolyte solution. Ann Intern Med 1969;70:1173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santosham M. Oral rehydration therapy of infantile diarrhea a controlled study of well-nourished children hospitalized in the United States and panama. N Engl J Med 1982;306:1070–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spandorfer PR, Alessandrini EA, Joffe MD, et al. Oral versus intravenous rehydration of moderately dehydrated children: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2005;115:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munos MK, Walker CLF, Black RE. The effect of oral rehydration solution and recommended home fluids on diarrhoea mortality. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39(Suppl. 1):i75–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Victora CG, Bryce J, Fontaine O, et al. Reducing deaths from diarrhoea through oral rehydration therapy. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 2012;379:2151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsberg BC, Petzold MG, Tomson G, et al. Diarrhoea case management in low- and middle-income countries: an unfinished agenda. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:42–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharya S. Progress in the prevention and control of diarrhoeal diseases since Independence. Natl Med J India 2002;16:15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montague D. Oxfam must shed its ideological bias to be taken seriously. BMJ 2009;338:b1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill CJ, Young M, Schroder K, et al. Childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea 3 bottlenecks, barriers, and solutions: results from multicountry consultations focused on reduction of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea deaths. Lancet 2013;381:1487–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gitanjali B, Weerasuriya K. The curious case of zinc for diarrhea: unavailable, unprescribed: unused. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2011;2:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konde-Lule JK, Elasu S, Musonge DL. Knowledge, attitudes, practices and their policy implications in childhood diarrhoea in Uganda. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res 1992;10:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haak H, Claeson ME. Regulatory actions to enhance appropriate drug use: the case of antidiarrhoeal drugs. Soc Sci Med 1996;42:1011–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittal S, Mathew JL. Regulating the use of drugs in diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001;33:S26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Igun UA. Reported and actual prescription of oral rehydration therapy for childhood diarrhoeas by retail pharmacists in Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 1994;39:797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomson G, Sterky G. Self-prescribing by way of pharmacies in three Asian developing countries. Lancet 1986;2:620–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ickx P. Central Asia Infectious Diseases Program, Simulated Purchase Survey, Rational Pharmaceutical Management, Kazakhstan. Arlington, VA: BASICS, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howteerakul N, Higginbotham N, Freeman S, et al. ORS is never enough: physician rationales for altering standard treatment guidelines when managing childhood diarrhoea in Thailand. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1031–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baqui AH, Black RE, El Arifeen S, et al. Zinc therapy for diarrhoea increased the use of oral rehydration therapy and reduced the use of antibiotics in Bangladeshi children. J Health Popul Nutr 2004;22:440–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aung T, McFarland W, Khin HSS, et al. Incidence of pediatric diarrhea and public–private preferences for treatment in rural Myanmar: a randomized cluster survey. J Trop Pediatr 2012;59:10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basu S, Andrews J, Kishore S, et al. Comparative performance of private and public healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sood N, Wagner Z. For-profit sector immunization service provision: does low provision create a barrier to take-up? Health Policy Plan 2013;28:730–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sood N, Wagner Z. Private sector provision of oral rehydration therapy for child diarrhea in Sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;90:939–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muhuri PK, Anker M, Bryce J. Treatment patterns for childhood diarrhoea: evidence from demographic and health surveys. Bull World Health Organ 1996;74:135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langsten R, Hill K. Treatment of childhood diarrhea in rural Egypt. Soc Sci Med 1995;40:989–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waters HR, Hatt LE, Black RE. The role of private providers in treating child diarrhoea in Latin America. Health Econ 2008;17:21–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.USAID. Diarrhoea Treatment Guidelines: Including New Recommendations for the Use of ORS and Zinc Supplementation for Clinic-based Healthcare Workers. Arlington, VA: USAID Micronutrient Program, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO, UNICEF. Diarrhoea: why children are still dying and what can be done. Geneva: UNICEF/WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS Wealth Index. Calverton, Maryland: Demographic and Health Surveys, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutstein SO, Rojas G. Guide to DHS Statistics. Calverton, Maryland: Demographic and Health Surveys, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee AV, Duflo E, Glennerster R, et al. Improving immunisation coverage in rural India: clustered randomised controlled evaluation of immunisation campaigns with and without incentives. BMJ 2010;340:c2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]