Abstract

Background

Little is known about rates and determinants of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, an infection that is etiologically linked with oropharyngeal cancers.

Methods

A cohort of male university students (18–24 years of age) was examined every 4 months (212 men; 704 visits). Oral specimens were collected via gargle/rinse and swabbing of the oropharynx. Genotyping for HPV type 16 (HPV-16) and 36 other alpha-genus types was performed by PCR-based assay. Data on potential determinants was gathered via clinical examination, in-person questionnaire, and biweekly online diary. Hazard ratios (HR) were used to measure associations with incident infection.

Results

Prevalence of oral HPV infection at enrollment was 7.5% and 12-month cumulative incidence was 12.3% (95% confidence interval (CI): 7.0, 21.3). Prevalence of oral HPV-16 was 2.8% and 12-month cumulative incidence was 0.8% (CI: 0.1, 5.7). 28.6% of prevalent and none of incident oral HPV infections were detected more than once. In a multivariate model, incident oral HPV infection was associated with recent frequency of performing oral sex (≥1 per week: HR=3.7; CI: 1.4, 9.8), recent anal sex with men (HR=42.9; CI: 8.8, 205.5), current infection with the same HPV type in the genitals (HR=6.2; CI: 2.4, 16.4) and hyponychium (HR=11.8, CI: 4.1; 34.2).

Conclusions

Although nearly 20% of sexually active male university students had evidence of oral HPV infection within 12 months, most infections were transient. HPV-16 was not common. Sexual contact and autoinoculation appeared to play independent roles in the transmission of alpha-genus HPV to the oral cavity of young men.

Keywords: HPV, oral HPV, young men, epidemiology

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is an etiologic agent for oropharyngeal cancers, with the strongest associations observed for cancer of the tonsils.1 Among HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers, up to 90% are associated with HPV type 16 (HPV-16).2 Although head and neck cancers are rare in the United States, there has been a significant increase in HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer in the last 30 years.3 This increase has been especially notable in the last 10 years and has occurred predominately in males, among whom oropharyngeal cancer is more common.4 If current trends continue, the annual number of new HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer cases in the United States could surpass that of cervical cancer by 2020.5

Prevalence estimates for HPV in the oral cavity or oropharynx, known collectively as oral HPV infection, vary substantially from study to study (<1%6 to >50%7). The variability has been attributed to differences in study populations and approaches to specimen collection, processing, and testing. A recent population-based study estimated oral HPV prevalence among 14–69 year-olds in the US as 6.9%.8 No such estimate is available for incidence.

Although transmission of HPV to the oral cavity and oropharynx is hypothesized to occur mainly through sexual contact, determinants of acquisition have not been fully established through longitudinal studies. Cross-sectional associations between prevalent oral HPV infection and sexual behaviors, such as higher numbers of vaginal sex partners or oral sex partners, have been observed in some studies,8–11 but not others.12,13 Prevalent oral HPV infection also has been linked with male sex, increasing age, cigarette smoking, and cervical HPV infection.8–12,14,15

We conducted a longitudinal study to determine the prevalence and incidence of oral alpha-genus HPV infection (overall and by HPV type) in young men, and to examine factors associated with new infection.

METHODS

Study population

Participants were recruited between September, 2008 and April, 2010 from an ongoing male HPV cohort study at the University of Washington, Seattle Washington.16 The study protocol was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division.

Men were eligible for the oral HPV study if they were (1) 18–25 years of age; (2) permanent residents of Washington state; (3) in general good health and immune competent; (4) able to provide informed consent; and (5) sexually active with women. Of the 214 men eligible from the parent study, none refused to participate in the oral HPV study. Two men however were excluded because they reported receiving the HPV vaccine prior to September 2008.

Data collection

Participants were seen every 4 months for up to 1.5 years for the oral HPV study (3 years for the parent study). Clinic visit procedures for the parent study have been described elsewhere.16 Briefly, at each visit, the research nurse practitioner administered a medical- and sexual-history interview followed by genital examination. The examination included collection of exfoliated cell specimens for HPV genotyping from the penile shaft, glans and scrotum. The exfoliated cells were placed in site-specific vials that contained 1 ml of Specimen Transport Medium (STM) (Qiagen, formerly Digene, Gaithersburg MD). At each visit, urine was collected for detection of HPV DNA from the internal urethral meatus.16 If clinically indicated, urine was tested for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (ATPIMA, Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA). Hyponychial specimens were self-collected on both hands using a cytology brush to rub the underside of each fingernail tip. Between visits, participants completed biweekly online diaries in which they recorded sexual behaviors for each day and each sex partner.

After completing the parent study visit procedures, men were recruited for the oral HPV study. All interested men underwent the informed consent process. At enrollment and at each 4-monthly follow-up visit, the nurse practitioner administered an additional questionnaire. It included questions on oral sex, open-mouth kissing, respiratory tract infections, tobacco use, marijuana use, tonsillectomy, mononucleosis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), GERD-like symptoms, nail biting, and dental hygiene.

The nurse practitioner then oversaw collection of 2 types of oral specimens for HPV genotyping: a gargle/rinse and 2 self-collected oropharyngeal swabs. For the gargle/rinse, participants rinsed and gargled 10 ml of Scope™ mouthwash (Proctor & Gamble, Cincinnati, Ohio) for 30 seconds. Following collection, the mouthwash was poured into a separate vial and centrifuged for 5 minutes. The resulting cell pellet was stored in 1mL STM. The participant was then instructed and supervised in mirror-assisted self-collection with a polyester fiber-tipped swab, first from the tonsils or palatine arches and then from the back of the tongue and pharynx. The swabs were stored in 1mL STM.

Alpha-Genus HPV DNA Detection and Genotyping

The STM samples were digested with 20 μg/ml protease K at 37°C for 1 hour. For each sample, 400 μl was used to isolate DNA by QIAamp DNA blood mini kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Cat. No. 51104). Each sample was digested with protease K at 56°C for 10 min and then loaded onto 1 QIAamp column. The column was washed and DNA eluted in 50 μl heated TE (Tris, EDTA buffer, 70°C). HPV specific DNA was PCR amplified and detected by dot blot hybridization using the MY-09-MY11-HMB01 primers and probes. HPV positive samples were subsequently genotyped for 37 alpha-genus HPV types (HPV-6/-11/-16/-18/-26/-31/-33/-35/-39/-40/-42/-45/-51/-52/-53/-54/-55/-56/-58/-59/-61/-62/-64/-66/-67/-68/-69/-70/-71/-72/-73/-81/-82/-83/-84/-IS39/-CP6108) using a liquid bead microarray assay based on Luminex technology, as described in detail by Feng et al17 Specimens negative for both β-globin and HPV DNA were considered insufficient for HPV DNA testing. HPV-61 and HPV-71 were excluded from the analyses due to quality control issues with those specific HPV types.

Statistical analysis

A positive HPV DNA test result for the swab or gargle/rinse was considered to be a detection of oral HPV infection. Prevalent infection was defined as detection of oral HPV infection at enrollment. Incident oral HPV infection of any HPV, or of a specific type, was defined as the first oral HPV detection after observed negative result(s) for all types, or for the specific type, respectively. The time of incident infection was defined as the visit at which it was first detected. We estimated cumulative probabilities of incident type-specific oral HPV infection using Kaplan-Meier analysis with any HPV infection measured as the first infection of any HPV type. We measured concordance between oral collection methods using an unweighted kappa (κ) statistic and percentile bootstrap methods with 1000 repetitions to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for κ while accounting for correlation within participants.

To examine potential determinants of incident oral HPV infection, we estimated hazard ratios (HR) using marginal Cox proportional hazards models.18 Data on all HPV types were included in the models, with stratification by type and correlation within participants accounted for using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with robust standard errors.19 With the exception of age and self-reported race, we modeled potential determinants as time-varying covariates, which were assessed for the 4 months prior to visit date (e.g. number of oral sex partners in the last 4 months). For characteristics measured continuously, we created categories by quartile or tertile. Characteristics associated with oral HPV infection in unadjusted analyses (p 0.05) were considered for the multivariate model.

RESULTS

The 212 men (median age of 20 years) enrolled in the oral HPV study were predominately white and mostly non-smokers (Table 1). The median lifetime number of vaginal sex partners was 3 and the median number of female partners on whom the participants performed oral sex was 2. Four men reported a history of sex with men. The median follow-up time was 10.7 months (interquartile range (IQR): 4.4–13.2) and the total number of study visits was 704. The median time between visits was 3.9 months (IQR: 3.4–4.4).

Table 1.

Enrollment characteristics of the male participants in the University of Washington Oral Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Cohort, September, 2008-April, 2010 (n=212)

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 20 (19–21) |

| Race/Ethnicity, no. (%) | |

| Caucasian | 175 (82.6) |

| Black | 4 (1.9) |

| Asian | 19 (9.0) |

| Hispanic | 6 (2.8) |

| Other | 8 (3.8) |

| Cigarette smoking, no. (%) | |

| Never | 186 (87.7) |

| Former | 14 (6.6) |

| Current | 12 (5.7) |

| Lifetime no. of vaginal sex partners, no. (%) | |

| 0 | 2 (0.9) |

| 1 | 62 (29.3) |

| 2 to 4 | 89 (42.0) |

| ≥5 | 59 (27.8) |

| Lifetime no. of females on whom performed oral sex, no. (%) | |

| 0 | 11 (5.2) |

| 1 | 63 (29.7) |

| 2 to 4 | 95 (44.8) |

| ≥5 | 43 (20.3) |

| History of sex with males (%) | |

| 0 | 208 (98.1) |

| ≥1 | 4 (1.9) |

During study visits, 75 type-specific oral HPV infections (prevalent, incident, or persistent infection) were detected in 33 men; 37 (49%) by gargle/rinse only, 29 (39%) by self-collected swab only and 9 (12%) by both methods (κ=0.21; CI: 0.07, 0.34) (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which enumerates HPV type-specific agreement between methods). Insufficiency (absence of β-globin DNA) for the gargle/rinse was 0.2% (2/702) and 0.1% (1/704) for the self-collected swab. At these same visits, 628 type-specific genital HPV infections were detected in 126 men and 192 type-specific hyponychial HPV infections were detected in 78 men. Among the 75 type-specific oral HPV infections, the same HPV type was detected concurrently in the genitals of 15 men (40.0% of infections) and the same type detected in a hyponychial site of 22 men (21.3% of infections).

Prevalence of oral HPV infection at enrollment was 7.5%, with just over half of infected men positive for >1 HPV type (Table 2). Among the 34 type-specific prevalent infections, the most common were HPV-16 (2.8%), HPV-18 (2.4%), HPV-33 (1.9%), and HPV-39 (1.9%). Eight (28.6%) of 28 men with prevalent infection and at least 1 follow-up visit had the same HPV type detected at 1 or more follow-up visits. As we did not sample men at shorter intervals, infections with durations shorter than 4 months would be missed.

Table 2.

Prevalence at enrollment and 12-month cumulative incidence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in young men, overall and by type,* University of Washington Oral Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Cohort

| HPV type(s)# | Prevalence, no. (%) | Incidence at 12 mo., no. of infections/person-yr | Cumulative incidence at 12 mo., % (95% CI) | Total no. of incident infections |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any type$ | 16 (7.5) | 12/134 | 12.3 (7.0, 21.3) | 17 |

| By swab | 8 (3.8) | 11/144 | 9.3 (5.0, 16.7) | 15 |

| By gargle/rinse | 11 (5.2) | 7/136 | 6.3 (2.9, 13.3) | 8 |

| Multiple types& | 9 (4.2) | 4/145 | 3.3 (1.2, 8.9) | 6 |

| 6£ | 1 (0.5) | 0/146 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 6 (2.8) | 1/142 | 0.8 (0.1, 5.7) | 2 |

| 18 | 5 (2.4) | 2/144 | 2.7 (0.7, 10.2) | 2 |

| 31 | 3 (1.4) | 1/143 | 1.3 (0.2, 8.8) | 1 |

| 33 | 4 (1.9) | 0/144 | 0 | 1 |

| 35 | 1 (0.5) | 1/144 | 0.6 (0.1, 3.9) | 1 |

| 39 | 4 (1.9) | 3/142 | 2.3 (0.7, 7.1) | 3 |

| 45 | 1 (0.5) | 0/146 | 0 | 1 |

| 51 | 2 (0.9) | 2/144 | 2 (0.5, 8.6) | 3 |

| 52 | 1 (0.5) | 2/146 | 1.9 (0.4, 7.9) | 2 |

| 53 | 0 (0) | 1/146 | 0.9 (0.1, 6.0) | 1 |

| 55 | 2 (0.9) | 0/145 | 0 | 0 |

| 59 | 1 (0.5) | 0/145 | 0 | 0 |

| 62 | 1 (0.5) | 0/146 | 0 | 2 |

| 66 | 1 (0.5) | 0/145 | 0 | 2 |

| 81 | 1 (0.5) | 0/145 | 0 | 1 |

| 83 | 0 (0) | 1/146 | 0.9 (0.1, 6.0) | 1 |

| 84 | 0 (0) | 2/146 | 1.2 (0.3, 4.6) | 2 |

There were no prevalent or incident infections of HPV types 11, 26, 40, 42, 54, 56, 58, 64, 68, 69, 70, 72, 73, 82, cp6108, and is39.

Detected by swab or gargle/rinse unless otherwise indicated

Participants with any oral HPV infection at baseline were excluded from the calculation of incidence for “Any type”

Among prevalent and incident infections, respectively

Participants were excluded from the calculation of oral HPV incidence by type if they were positive for that HPV type at baseline

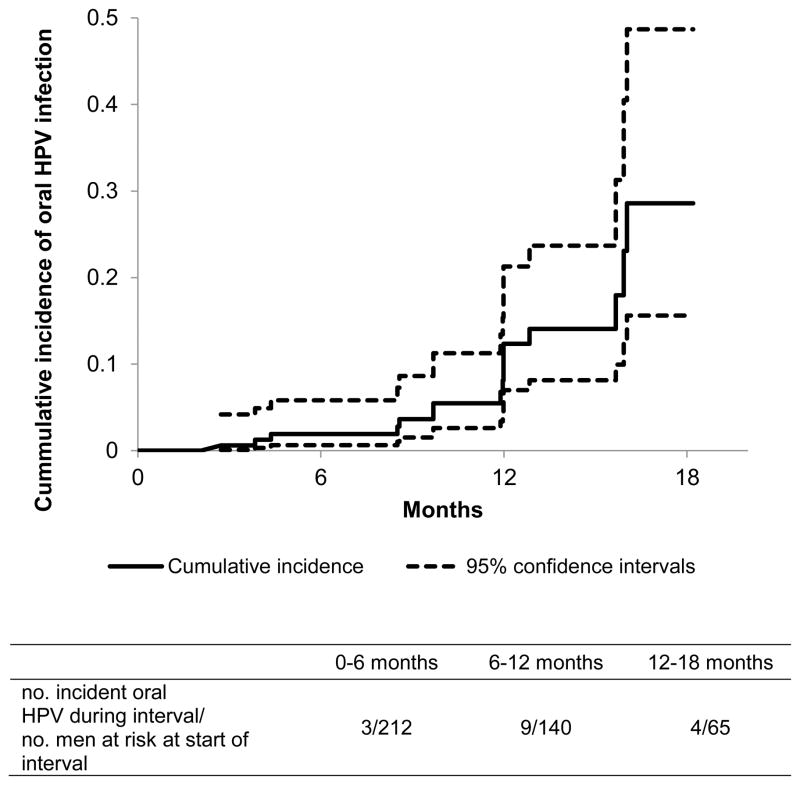

The 12-month cumulative incidence of any oral HPV infection was 12.3% (Figure 1) and it was 3.3% for multiple concurrent oral HPV infections, 0.8% for HPV-16, 2.7% for HPV-18, and 2.3% for HPV-39 (Table 2). Seven of 26 men with incident oral HPV infection had ≥ 1 visit after the initial detection and none were repeatedly positive for the same HPV type.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in young men, University of Washington Oral HPV Cohort

Tables 3 and 4 contain HRs for univariate and multivariate associations with incident oral HPV infection that were estimated using data on all HPV types and GEE modeling techniques.

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (HRs) for univariate associations with incident oral HPV infection in young men, University of Washington Oral Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Cohort

| Characteristic | # infections/person-years | Unadjusted HR* | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline (years) | |||

| 18 to 20 | 17/4032 | ||

| 21 to 24 | 9/1656 | 1.91 | (0.7, 5.24) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 19/4672 | 1 | |

| Non-White | 7/1015 | 1.39 | (0.41, 4.73) |

| Smoked cigarettes | |||

| Never | 19/4891 | 1 | |

| Former | 5/450 | 2.60 | (0.66, 10.14) |

| Currently | 2/346 | 0.70 | (0.17, 2.89) |

| Smoked cigars# | |||

| Never | 20/4803 | 1 | |

| Former | 1/473 | 0.35 | (0.04, 2.78) |

| Currently | 5/411 | 2.51 | (0.57, 11.10) |

| Smoked a pipe# | |||

| Never | 20/5103 | 1 | |

| Former | 4/294 | 1.61 | (0.26, 10.11) |

| Currently | 2/290 | 2.12 | (0.59, 7.60) |

| Smoked marijuana# | |||

| Never | 11/3038 | 1 | |

| Former | 2/431 | 0.90 | (0.11, 7.42) |

| Currently | 13/2219 | 1.49 | (0.53, 4.20) |

| Teeth-brushing per week | |||

| ≤7 | 9/1373 | 1 | |

| 7 to 13 | 5/1420 | 0.50 | (0.13, 1.94) |

| ≥14 | 12/2866 | 0.68 | (0.23, 2.01) |

| Number of females on whom performed oral sex in the last 4 months | |||

| 0 | 9/2522 | 1 | |

| 1 | 17/3166 | 1.55$ | (0.59, 4.10) |

| ≥2 | 0/210 | ||

| New female partner on whom performed oral sex in the last 4 months | |||

| No new partner | 24/4594 | 1 | |

| New partner | 2/1094 | 0.42 | (0.05, 3.31) |

| Frequency of performing oral sex on female in the last 4 months& | |||

| No oral sex | 9/2522 | 1 | |

| <Once per month | 1/1034 | 0.32 | (0.04, 2.74) |

| ~1–2 times per month | 5/1297 | 0.97 | (0.26, 3.61) |

| ≥1 time per week | 11/835 | 4.16 | (1.36, 12.72) |

| Number of females open mouth kissed in the last 4 months | |||

| 0 | 3/604 | 1 | |

| 1 | 19/3252 | 1.38 | (0.30, 6.37) |

| ≥2 | 4/1803 | 0.62 | (0.11, 3.57) |

| Open mouth kissing frequency in the last 4 months £ | |||

| 0 to 1 per month | 3/1439 | 1 | |

| 2 to 9 per month | 5/1619 | 1.72 | (0.28, 10.39) |

| 10 to 30 per month | 3/1049 | 1.50 | (0.20, 11.44) |

| ≥31 per month | 15/1552 | 4.54 | (0.93, 22.17) |

| Number of vaginal sex partners in the last 4 months | |||

| 0 | 4/1502 | 1 | |

| 1 | 18/2901 | 2.32 | (0.75, 7.15) |

| ≥2 | 3/819 | 1.89 | (0.32, 11.14) |

| New vaginal sex partner in the last 4 months | |||

| No | 19/4149 | 1 | |

| Yes | 7/1538 | 0.96 | (0.31, 2.96) |

| Number of vaginal sex acts in the last 4 months | |||

| 0 | 5/1740 | 1 | |

| 1 to 4 | 4/1011 | 1.82 | (0.33, 9.95) |

| 5 to 16 | 7/1343 | 2.12 | (0.54, 8.28) |

| ≥17 | 10/1426 | 2.40 | (0.72, 8.06) |

| Number of female digital sex partners in the last 4 months | |||

| 0 | 3/1120 | 1 | |

| 1 | 19/3459 | 2.10 | (0.42, 10.37) |

| ≥2 | 4/1097 | 1.53 | (0.24, 9.62) |

| Frequency of digital sex with a female in last 4 months | |||

| No digital sex | 3/1120 | 1 | |

| <Once per month | 2/1002 | 1.15 | (0.10, 13.25) |

| 1–2 times per month | 3/1170 | 0.83 | (0.14, 4.82) |

| ≥1 time per week | 18/2384 | 2.83 | (0.58, 13.95) |

| Anal sex with a male in the last 4 months& | |||

| No | 24/5610 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2/67 | 10.67 | (3.02, 37.65) |

| Current genital HPV infection with same HPV type& | |||

| No | 15/5542 | 1 | |

| Yes | 11/146 | 10.38 | (3.72, 28.97) |

| Genital HPV infection with same HPV type 1 visit prior& | |||

| No | 23/5565 | 1 | |

| Yes | 3/123 | 3.28 | (1.00, 10.76) |

| Current hyponychial HPV infection with same HPV type& | |||

| No | 17/5645 | 1 | |

| Yes | 9/42 | 24.68 | (5.31, 114.65) |

| Hyponychial HPV infection with same HPV type 1 visit prior& | |||

| No | 23/5656 | 1 | |

| Yes | 3/31 | 18.64 | (3.64, 95.53) |

Based on models containing data on all HPV types with stratification by type and correlation accounted for using GEE with robust standard errors

To be considered a smoker of cigars, pipes or marijuana a participant must have smoked at least once a month for >1 year

With no incident oral HPV infections in the ≥ 2 category, the 1 and ≥ 2 categories were combined

p-value ≤ 0.05 for characteristic

p-value ≤ 0.05 for trend by categories given (quartiles)

Table 4.

Multivariate model for independent associations with incident oral HPV infection in young men, University of Washington Oral Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Cohort.

| Characteristic | # infections/person-years | Unadjusted HR* | 95% CI | Adjusted HR*,# | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of performing oral sex on a woman in the last 4 months$ | |||||

| <1 per time per week | 15/4853 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥1 per time per week | 11/835 | 4.85 | (1.7, 13.83) | 3.66 | (1.38, 9.75) |

| Frequency of open mouth kissing a woman in the last 4 months | |||||

| 0 to 30 times per month | 11/4107 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥31 times per month | 15/1552 | 3.32 | (1.24, 8.87) | 1.91 | (0.68, 5.38) |

| Anal sex with a man in the last 4 months$ | |||||

| No | 24/5610 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2/67 | 10.67 | (3.02, 37.65) | 42.9 | (8.95, 205.54) |

| Current genital HPV infection$ | |||||

| No | 15/5542 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 11/146 | 10.38 | (3.72, 28.97) | 6.24 | (2.37, 16.44) |

| Current hyponychial HPV infection$ | |||||

| No | 17/5645 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 9/42 | 24.68 | (5.31, 114.65) | 11.8 | (4.07, 34.21) |

Based on models containing data on all HPV types with stratification by type and correlation accounted for using GEE with robust standard errors

All characteristics presented in table are included in the multivariate model

p-value≤0.05 for characteristic in the multivariate model

Age and race/ethnicity were not associated with incident oral HPV infection (Table 3). Although the likelihood of incident oral HPV infection was higher for some forms of smoking, none of these associations were statistically significant (Table 3). No incident infections were detected in men who chewed tobacco, though the practice was uncommon (2% at enrollment). Higher frequency of teeth brushing was associated with a non-statistically significant lower likelihood of incident oral HPV infection. Number of alcoholic drinks when examined by beverage type (beer, wine or liquor) or in total, history of GERD, symptoms of GERD, and recent upper respiratory tract infection were not associated with incident oral HPV infection (data not shown). Although none of 20 men who reported having a tonsillectomy at enrollment developed a new oral HPV infection during follow-up, 8 (40%) had an oral HPV infection at enrollment.

Higher frequencies of performing oral sex and open mouth kissing, and report of any anal sex with a man in the last 4 months were statistically significantly associated with incident oral HPV infection, whereas recent number of oral, vaginal or digital sex partners, and frequency of vaginal or digital sex were not (Table 3). No incident oral HPV infections were detected in men who used dental dams while performing oral sex, though use was rare among participants (<1% of visits). There were no incident oral HPV infections among men with genital HSV-2, Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections, but these were also rare among participants (combined <1% of visits).

Concurrent HPV infection of a genital or hyponychial site was associated with incident oral HPV infection with the same HPV type (Table 3). Genital or hyponychial HPV infection 1 visit prior was also associated with incident oral HPV infection. However, among men with incident oral HPV infection, none within the subset that had had a prior genital or hyponychial HPV infection with the same HPV type had cleared that infection(s) at the time of incident oral HPV infection detection. Other factors potentially related to autoinoculation, including masturbation, fingernail biting, current genital warts, and circumcision status, were not associated with incident oral HPV infection (data not shown).

Independent associations observed in the multivariate model indicated that risk of incident oral HPV infection was elevated for men who (1) performed oral sex ≥ 1 time/week versus <1 time/week in the last 4 months (HR=3.6; CI: 1.4, 9.8; p=0.009), (2) reported recent anal sex with men versus no anal sex with men (HR=42.9; CI: 9.0, 205.5; p<0.0001), (3) had current infection with the same HPV type at a genital site versus no/other HPV type genital infection (HR=6.2; CI: 2.4, 16.4; p=0.0002) and (4) had current infection with the same HPV type at a hyponychial site versus no/other type HPV hyponychial infection (HR=11.8; CI: 4.1, 34.2; p<0.0001) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

In a cohort of sexually active young men, 7.5% were infected in the oral cavity or oropharynx with alpha-genus HPV at enrollment and an additional 12.3% became infected over the next 12 months. HPV-16 was one of the more common HPV types, though its prevalence (2.8%) and 12-month cumulative incidence (0.8%) were low. The prevalence of oral HPV infection in this study was similar to the estimate of 6.5% for US males aged 18–24 years in 2009–10,8 though greater than an estimated 3% reported for 2 studies with >200 men in this age range.11,12 These estimates, however, used only gargle/rinse specimens, which would have reduced our prevalence estimate to 5%. Similarly, the 12-month cumulative incidence observed among Finnish fathers-to-be (average age of 29 years) was approximately 5% as compared to our estimate of 12.3%, but oral specimens were collected by cytobrush only and tested only for 12 HPV types.13 Collection by both gargle/rinse and directed swab/cytobrush appears to be more sensitive than collection by a single method.20 The poor to fair agreement between the gargle/rinse and swabs targeting the oropharynx observed in our study (κ=0.21) has been reported by others (κ=0.16).14

The duration of most oral HPV infections appeared to be short with 72% of prevalent infections no longer detected, or “cleared”, within approximately 4 months. This is a higher rate of clearance than observed in the Finnish fathers-to-be study,13 which included older married men, and testing for fewer HPV types (clearance rates vary by type for genital infections21,22). That the prevalence of oral HPV infection observed in this study was lower than the cumulative incidence at 12 months, also suggests a short duration of infection given that prevalence can be estimated as product of incidence and duration. In fact, one might expect the prevalence to be lower based on the clearance we observed in our study population. However, because of the small number of infections for which we could observe duration (n=15) and the length of time between study visits (4 months) further research is needed to assess duration of oral HPV infection and its correlates.

Our findings support the hypothesis that alpha-genus HPV types exhibit a decreased tropism for epithelial cells of the oral cavity and hyponychium compared to the genitals. For this young male cohort, the published 12-month cumulative incidence of genital HPV infection was about 35%,16 which is similar to the estimate (39.3%) for a large multinational study of men (mean age: 32 years)21 and about 3-fold higher than was estimated in the present study for oral HPV infection (12.3%). Among men with oral HPV infection, 45% had the same type detected in the genitals concurrently. Concurrency was higher than that which has been observed between the oral cavity and the cervix in females,9,15 which could be due to anatomical differences. The published 12-month cumulative incidence of hyponychial HPV infection (15%)16 was similar to the estimate for oral infection (12.3%) in the present study and among men with an oral HPV infection, two-thirds were infected in a hyponychial site.

We found that risk of oral HPV infection was more strongly associated with frequency of sexual contact than with number of new sex partners. For example, frequency of performing oral sex but not number of oral sex partners within the last 4 months was associated with oral HPV infection. Other studies that have examined the relationship between oral sex and oral HPV infection have had mixed results.8,11–14,23 Reasons for not observing an association could include not capturing information on oral sex type (performing versus receiving), frequency, or relevant time frame.

It was difficult to discern whether sexual behaviors other than performing oral sex were independently associated with oral HPV because level of concurrency for all sexual behaviors was high. More than any other sexual behavior measured, men who recently performed oral sex were most likely to report recent deep kissing, vaginal sex, and digital sex with females (data not shown). Although the association we observed between having anal sex with men and incident oral HPV infection was strong, it lacked precision because of small numbers and the absence of information on oral sex with men. A more focused study of men who have sex with men is warranted, given our results and similar associations reported for prevalent infection.8,11,23

The strong associations between incident oral HPV infection and infection with the same HPV type at other sites indicate that transmission may occur through autoinoculation. However, even though these associations were independent of recent frequency of sexual contact (oral sex or open-mouth kissing) it is possible that HPV acquisition at each anatomical site occurred independently through an infected partner at some point between study visits. We did not have enough men without some form of sexual contact between visits to investigate this further. It is also possible that there are other unmeasured genetic or environmental factors that make some men more susceptible to alpha-genus HPV infection at any site.

In men, current smoking has been associated with prevalent oral HPV infection,11,12 though not in all studies,8 and it was not associated with incident infection in our study. It is possible that smoking is related to oral HPV infection persistence9 and not acquisition. Further study of oral HPV risk in populations with higher smoking rates may be warranted. Marijuana use has been reported as a risk factor for HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer,24 though not prevalent oral HPV infection.8 We found risk estimates for marijuana use and for current cigar and pipe smoking that were modestly elevated but were not statistically significant.

Our study was not without limitations. There is no gold standard for oral HPV specimen collection.25 and though the HPV type-specific assay used in this study has performed well in comparative analyses of test results for cervical specimens and purified plasmid samples,17,26 similar analyses have not yet been completed for specimens collected for oral HPV DNA detection. By using a swab that targeted the oropharynx and a gargle at the back of the throat we aimed to improve sensitivity. Our relatively small sample size affected the precision of our measure of oral sampling agreement and our risk estimates, as well as potentially limited our ability to detect more modest associations and the extent to which we could separate out correlated behaviors. Lastly, our findings pertain to young men who have sex with women and they might not generalize to older men, men with different sexual behaviors, women, or immuno-compromised men and women.

In summary, about 1 in 5 young men enrolled in this study had evidence of at least 1 oral HPV infection within a 12-month interval. Notably, most infections were transient and HPV-16, the type most often detected in oropharyngeal cancer, was not common. Frequent performance of oral sex, sex with another man, and infection of the same HPV type at another site were independently associated with incident oral HPV infection, but attribution of transmission to specific behaviors was undoubtedly incomplete. Skin-to-skin contact between multiple anatomical sites is an important, but difficult to measure aspect of sexual activity and personal hygiene. Looking beyond oral HPV infection to the natural history of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer is essential but complicated because characteristics of precancerous oral lesions and their relationship to oral HPV infection are still being defined.27,28 The increasing rate of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer (especially in men), the lack of early detection methods similar to those for cervical cancer, the uncertain benefits of promoting less skin-to-skin contact for prevention of HPV infection, and the high efficacy of HPV vaccines for preventing infections at different sites,29–31 all suggest that it is time to investigate and implement cost-effective adolescent HPV vaccination programs to prevent oral HPV-16 infection.

Summary.

In a study of oral HPV infection among young men, 12-month incidence was 12.3%, though HPV-16 was uncommon. Incident infection was independently associated with measures of sexual contact and autoinoculation.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to L.A.K. [grant numbers: R01 CA105181, R03 CA141493]. The study was conducted at University of Washington. However, the article was prepared in part while the first author [Z.R.E.] was at the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute, where she was supported by National Institute of Mental Health at National Institutes of Health [T32 MH019139]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: All authors: No reported conflicts.

References

- 1.Human papillomaviruses. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2007;90:1–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:612–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fast Stats: An interactive tool for access to SEER cancer statistics. [online database] Bethesda, MD: Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute; [Accessed on December 10, 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eike A, Buchwald C, Rolighed J, Lindeberg H. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is rarely present in normal oral and nasal mucosa. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1995;20:171–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1995.tb00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terai M, Hashimoto K, Yoda K, Sata T. High prevalence of human papillomaviruses in the normal oral cavity of adults. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1999;14:201–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.1999.140401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, et al. Prevalence of Oral HPV Infection in the United States, 2009–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:693–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Souza G, Fakhry C, Sugar EA, et al. Six-month natural history of oral versus cervical human papillomavirus infection. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:143–50. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith E, Swarnavel S, Ritchie J, Wang D, Haugen T, Turek L. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in the oral cavity/oropharynx in a large population of children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:836–40. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318124a4ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Souza G, Agrawal Y, Halpern J, Bodison S, Gillison M. Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1263–9. doi: 10.1086/597755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreimer AR, Villa A, Nyitray AG, et al. The epidemiology of oral HPV infection among a multinational sample of healthy men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:172–82. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rintala M, Grénman S, Puranen M, Syrjänen S. Natural history of oral papillomavirus infections in spouses: a prospective Finnish HPV Family Study. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreimer A, Alberg A, Daniel R, et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection in adults is associated with sexual behavior and HIV serostatus. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:686–98. doi: 10.1086/381504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fakhry C, D’souza G, Sugar E, et al. Relationship between prevalent oral and cervical human papillomavirus infections in human immunodeficiency virus-positive and -negative women. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4479–85. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01321-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Partridge JM, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Genital human papillomavirus infection in men: incidence and risk factors in a cohort of university students. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1128–36. doi: 10.1086/521192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Q, Cherne S, Winer R, et al. Development and evaluation of a liquid bead microarray assay for genotyping genital human papillomaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:547–53. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01707-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei L, Lin D, Weissfeld L. Regression analysis of multivariate incomplete failure time data by modeling marginal distributions. Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1065–73. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin D. Cox regression analysis of multivariate failure time data: the marginal approach. Stat Med. 1994;13:2233–47. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780132105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawton G, Thomas S, Schonrock J, Monsour F, Frazer I. Human papillomaviruses in normal oral mucosa: a comparison of methods for sample collection 1. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:265–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giuliano AR, Lee JH, Fulp W, et al. Incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:932–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trottier H, Franco EL. The epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. Vaccine. 2006;24 (Suppl 1):S1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coutlée F, Trottier AM, Ghattas G, et al. Risk factors for oral human papillomavirus in adults infected and not infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:23–31. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199701000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gillison ML, D’Souza G, Westra W, et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers 1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:407–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braakhuis B, Brakenhoff R, Meijer C, Snijders P, Leemans C. Human papilloma virus in head and neck cancer: The need for a standardised assay to assess the full clinical importance. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2935–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eklund C, Forslund O, Wallin KL, Zhou T, Dillner J for the WHO Human Papillomavirus Laboratory Network. The 2010 Global Proficiency Study of Human Papillomavirus Genotyping in Vaccinology. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2289–98. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00840-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller C, White D. Human papillomavirus expression in oral mucosa, premalignant conditions, and squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varnai A, Bollmann M, Bankfalvi A, et al. The prevalence and distribution of human papillomavirus genotypes in oral epithelial hyperplasia: proposal of a concept. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:181–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV Infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:401–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The FUTURE II Study Group. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1576–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]