Background: The bZIP-type transcription factors are widely distributed in eukaryotes to control an array of biological activities.

Results: MBZ1 from Metarhizium robertsii regulates fungal growth, cell wall integrity, spore adherence, and virulence against insects.

Conclusion: MBZ1 is required for development and virulence of insect pathogenic fungi.

Significance: The orthologs of bZIP-type transcription factors are functionally divergent in different organisms.

Keywords: Cell Wall, Fungi, Insect, Transcription Factor, Virulence Factor, Basic Leucine Zipper Domain, Metarhizium robertsii, Cell Adherence, Cell Autolysis, Cell Wall Integrity

Abstract

Transcription factors (TFs) containing the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domain are widely distributed in eukaryotes and display an array of distinct functions. In this study, a bZIP-type TF gene (MBZ1) was deleted and functionally characterized in the insect pathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii. The deletion mutant (ΔMBZ1) showed defects in cell wall integrity, adhesion to hydrophobic surfaces, and topical infection of insects. Relative to the WT, ΔMBZ1 was also impaired in growth and conidiogenesis. Examination of putative target gene expression indicated that the genes involved in chitin biosynthesis were differentially transcribed in ΔMBZ1 compared with the WT, which led to the accumulation of a higher level of chitin in mutant cell walls. MBZ1 exhibited negative regulation of subtilisin proteases, but positive control of an adhesin gene, which is consistent with the observation of effects on cell autolysis and a reduction in spore adherence to hydrophobic surfaces in ΔMBZ1. Promoter binding assays indicated that MBZ1 can bind to different target genes and suggested the possibility of heterodimer formation to increase the diversity of the MBZ1 regulatory network. The results of this study advance our understanding of the divergence of bZIP-type TFs at both intra- and interspecific levels.

Introduction

Much of our knowledge about the features and functions of transcription factors (TFs),2 including a group of structurally and functionally related members containing the conserved basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domain, comes from the discovery and study of AP-1 (activating protein 1) (1). The bZIP TFs are one of the largest families of dimerizing TFs and are widely distributed in the genomes of all eukaryotes (2). The prototypical bZIP TF was first discovered over 30 years ago in humans (3), and members are now classified into 19 families regulating a plethora of biological functions, including the cell cycle, development, reproduction, metabolism, and programmed cell death (2). Besides animals, bZIP-type TFs have also been well characterized in plants by mediating pathogen defense, abiotic stress response, hormone signaling, energy metabolism, and senescence (4).

In fungi, a bZIP-type TF was first characterized as YAP1 (yeast activating protein 1) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (5), and then members of the family (YAP1–YAP8) were found and verified to be functionally distinct in yeast (6). Different bZIP-type TFs have also been characterized in various filamentous fungal species, including Aspergillus nidulans (7, 8), Neurospora crassa (9), and the plant pathogens Fusarium graminearum (10–12) and Magnaporthe oryzae (13–15). Deletions and functional characterizations of these genes revealed that bZIP-type TFs are involved in mediating fungal development, sexuality, stress responses, secondary metabolisms, and especially the virulence of plant pathogens. For example, the bZIP-type TF FGZIF1 was identified to be involved in the control of mycotoxin deoxynivalenol production, sexuality, and virulence in F. graminearum (11). MOAP1 of M. oryzae was functionally verified as a positive regulator of different target genes involved in growth, development, and pathogenicity (14). Genome analyses of insect fungal pathogens such as Metarhizium robertsii (16), Cordyceps militaris (17), and Beauveria bassiana (18) also identified an array of bZIP-type TFs present in their genomes. However, none of these has been functionally studied.

Insect pathogenic fungi such as M. robertsii, Metarhizium acridum, and B. bassiana diverged after mammalian and plant pathogens (19) and have been developed as promising and environmentally friendly mycoinsecticides (20, 21). Molecular pathogenesis studies have revealed the functions of genes involved in insect cuticle adherence, degradation, penetration, immune invasion, and production of insecticidal mycotoxins (22, 23). However, the TFs involved in regulation of virulence-related genes are still unknown.

In this study, the bZIP-type TF gene MAA_01736, designated MBZ1, was deleted and functionally characterized in the insect pathogen M. robertsii. This gene was previously found to be highly transcribed by the fungus during early infection (16). Our functional studies showed that MBZ1 mediates both positive and negative regulation of different target genes involved in growth, sporulation, cell wall integrity, spore adherence, and virulence against insect hosts in M. robertsii.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fungal Strains and Culturing Conditions

The WT strain and mutants of M. robertsii ARSEF 2575 were routinely maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Difco) or on complete mineral medium for the conidiation assays at 25 °C (24). In addition, the PDA medium was buffered with final concentrations of 1 μg/ml tunicamycin (Sigma), 200 μg/ml Calcofluor White (Sigma), 300 μg/ml amphotericin B (Biosharp), 4 mm CuSO4, 0.5 m sorbitol, 1 mm DTT, or 0.01% SDS for cell well stress challenges (25, 26). For liquid incubation, fungi were grown in Sabouraud dextrose broth (SDB; Difco) with or without 50 μg/ml Congo red (Bio Basic Inc.) at 25 °C for 18 h in a rotary shaker. To induce protease expression, fungal cultures were grown in a minimum medium containing 1% silkworm pupa homogenate at 25 °C in a rotary shaker (27). For mycotoxin production assays, the WT and mutants were grown in Czapek Dox broth at 25 °C for 1 week in a rotary shaker (28). Yeast strains AH109 (MATa, TRP1-901, LEU2-3,112, URA3-52, HIS3-200, GAL4Δ, GAL80Δ, LYS2::GAL1UAS-GAL1TATA-HIS3, MEL1 GAL2UAS-GAL2TATA-ADE2, URA3::MEL1UAS-MEL1TATA-LACZ) and EGY48 (MATα, TRP1, HIS3−, URA3−, LEU2::6 LEX-AOPS-LEU2) (Invitrogen) were used for yeast one-hybrid transcriptional activation tests. The yeast cells were cultured in 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose, and 2 mg/liter adenine; 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose; or synthetic dropout medium (24, 29).

Bioinformatics Analysis

Genome-wide surveys for bZIP domain-containing TFs were performed by BLASTp searches of the genomes of M. robertsii and other fungi. The protein sequences of functionally verified bZIP-type TFs from yeast and other species were found and aligned with those from M. robertsii with ClustalX 2.0 (30). A maximum likelihood tree was generated using a Dayhoff model with 1000 replicates for bootstrapping using the program MEGA6 (31). For analysis of the putative MBZ1-binding site, the promoter regions (∼1.5 kb upstream of each start codon) of selected genes were retrieved and analyzed using the weight matrix-based program Match (version 1.0).

Subcellular Localization and Transcriptional Activation Assays

For the subcellular localization assay of MBZ1, the HSP70 gene (MAA_02081) promoter, GFP, and full-length MBZ1 genes were amplified individually by PCR, and the cassette was generated by fusion PCR with different primer pairs (Table 1). The product was cloned into binary vector pDHT-BAR to produce plasmid pBAR-HSP70p-GFP-linker-MBZ1 with a ClonExpress kit (Vazyme). The resulting vector was used for transformation of the M. robertsii strain. For the transcriptional activation test, full-length cDNA of MBZ1 was amplified from a cDNA library with primers 1736CF and 1736CR and cloned into the NdeI and BamHI sites of the yeast vector pBKT7 (Invitrogen) under the control of the GAL4 promoter to generate plasmid pBKT7-MBZ1 for transformation into the AH109 yeast strain. Putative prototrophic transformants were selected using a Trp-free synthetic dropout medium and further transferred into Trp/His/Ade-free synthetic dropout plates for transcriptional activation assays. The negative control was made by transforming yeast with the blank vector, and the positive control yeast was transformed with the pBKT7 vector containing the GAL4 activation domain sequence (29).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| TF1736DF | GCTCTAGAACTCCGTACAGCCACAATCC | For construction of gene disruption vector pBAR-MBZ1 |

| TF1736DR | GCTCTAGATCAGTGTCTGGGTCGTTGAG | |

| TF1736UF | GGAATTCCCCAAGGACATTGACACAGA | |

| TF1736UR | CCGCTCGAGCGGTCCGACGTATTCTTGTT | |

| TF1736F | GCCTGTGATGGCAGTTACAA | For RT-PCR verification |

| TF1736R | ACACAACGGAGTCAATGCTG | |

| TubF | GATCTTGAACCTGGCACCAT | Used as an internal control for RT-PCR |

| TubR | CCATGAAGAAGTGCAGACGA | |

| 1736SF | GCTCTAGATGGGCAGGTACGGAGTAGTT | For construction of gene complementation vector pBEN-MBZ1 |

| 1736SR | GCTCTAGAATTGGTCGAGTGGCGTAAAG | |

| 1736CF | GGAATTCCATATGATGTCGACTTCTAGCCAAAC | For testing transcription activation |

| 1736CR | CGGGATCCTTATATGTCCATGGTCAAAAG | |

| Hsp70F | CGGGCCCCCCCTCGAGGCAGTAGAGGTGTAGTTG | For generating plasmid pBAR-HSP70p-GFP-linker-MBZ1 |

| Hsp70R | TGTGGTGGTTGTGATGCG | |

| 1736GF | ATCACAACCACCACAATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGA | |

| 1736GR | CTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGC | |

| 1736CfusionF | GACGAGCTGTACAAGGGCGGAGCTGGTGCGGGCGCAGGCATGTCGACTTCTAGCCAAAC | |

| 1736CfusionR | CGGGCTGCAGGAATTCTTATATGTCCATGGTCAAAA | |

| 1794F | TCATAGACACGGAACAAT | For RT-PCR and qRT-PCR analyses |

| 1794R | GAGTAGCCGATAGGGATA | |

| 2558F | TAGAGGTCAAAGGCAACG | |

| 2558R | TGTGACGGCACGAAGATA | |

| 2062F | TGGTTCCTTCCACACGTACA | |

| 2062R | CTTGGAGAAGTCGGTGAAGC | |

| 4636F | TACTTCCAGAGCGTCGAGGT | |

| 4636R | AAAAACCACACCAGGCAAAG | |

| 2408F | AGAGAAGACGTACGGTGTCG | |

| 2408R | CTTGCACATCTTCGTCTGTG | |

| 5675F | ACCAAGGAGGAGCTGAAGAT | |

| 5675R | TGATACCGGAGTAGGAACCA | |

| 10246F | CGGTCCTTCCAGATAAAC | |

| 10246R | CAGAGTCAACTTTGTTTGGT | |

| 10260F | ACCACCATAGCTGGATTCAA | |

| 10260R | GAGAACCTTGACGGCATAGA | |

| 7202F | GACGGAGACAAGAAGAACG | |

| 7202R | AATAACAAGCGGCGAACC | |

| 3775F | CAGGCTTCTGCTACCTTTGG | |

| 3775R | TGTCGAAGCTGTCAATGGAG | |

| 1736HF | GACTAGTTGTCGACTTCTAGCCAAACC | For construction of plasmid pPC86-MBZ1 |

| 1736HR | CGAGCTCTTATATGTCCATGGTCAAAA | |

| pPC86F | TATAACGCGTTTGGAATCACT | |

| pPC86R | GTAAATTTCTGGCAAGGTAGAC | |

| 1794YF | AGTTATTACCCTCGAGCGTCCAATGCTGCAAGACTA | For generating p178-Xpromoter plasmids for yeast one-hybrid tests |

| 1794YR | GGCGGATCTGCTCGAGATGAAATGAGGCCGTAGTGG | |

| 2558YF | AGTTATTACCCTCGAGGGAGGGGGTTTGTTAATGT | |

| 2558YR | GGCGGATCTGCTCGAGGTATCACCCCTGCAAATGA | |

| 2062YF | AGTTATTACCCTCGAGTGGAGCTTCAAGTGTCATG | |

| 2062YR | GGCGGATCTGCTCGAGGAGCGGGATATGTCAAGGA | |

| 4636YF | AGTTATTACCCTCGAGAGCCCCCTTTTCTTTGTGTT | |

| 4636YR | GGCGGATCTGCTCGAGACCTCGACGCTCTGGAAGTA | |

| 2408YF | AGTTATTACCCTCGAGCAGCCAAAAGCCAAATCAAC | |

| 2408YR | GGCGGATCTGCTCGAGGGTCTTGTTGGGCACATTCT | |

| 5675YF | AGTTATTACCCTCGAGAGAGGGCAGGTTCAAAGACA | |

| 5675YR | GGCGGATCTGCTCGAGGTACGGGACCAAAGACCAGA | |

| 10246YF | AGTTATTACCCTCGAGTGTTGTAGACCCCTCCAAGG | |

| 10246YR | GGCGGATCTGCTCGAGTTGCTGCAGGACGATGTTAG | |

| 10260YF | AGTTATTACCCTCGAGTGGTCAGTGGTGGTCACTGT | |

| 10260YR | GGCGGATCTGCTCGAGCTTGGTAGGAGCGAGAATCG | |

| 7202YF | CCGCTCGAGACCCAGCCGAGTTAAGGTTT | |

| 7202YR | CCGCTCGAGACCGCAACTGGGAATAATTG | |

| 3775YF | AGTTATTACCCTCGAGCTGGCTGTCATGGAGTCTG | |

| 3775YR | GGCGGATCTGCTCGAGTGGATGTCAGGCACGTAAA |

Gene Deletion and Complementation

Targeted gene deletion of the MBZ1 gene was performed by homologous recombination via Agrobacterium-mediated fungal transformation as described previously (32, 33). In brief, the 5′- and 3′-flanking sequences were amplified using the genomic DNA as a template with primer pairs TF1736UF/TF1736UR and TF1736DF/TF1736DR, respectively (Table 1). The respective products were digested with the restriction enzymes EcoRI, XhoI, and XbaI and then inserted into the corresponding sites of the binary vector pDHT-BAR (conferring ammonium glufosinate resistance) to produce plasmid pBAR-MBZ1-KO for fungal transformation. For null mutant complementation, the ORF of the MBZ1 gene was amplified with its promoter and terminator regions using primer pairs 1736SF and 1736SR. The product was digested with XbaI and then inserted into vector pDHT-BEN to generate pBEN-MBZ1 (conferring resistance to benomyl) (34). The mutants were verified by PCR and RT-PCR analyses with primers TF1736F and TF1736R (Table 1). The complemented mutant was designated Comp.

Extraction and Quantification of Cell Wall Chitin

To quantify the chitin component of fungal cell walls, mycelia were harvested from SDB cultures; washed twice with sterile-distilled water; ground in liquid nitrogen; extracted with buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 2% SDS, 0.3 m β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mm EDTA; and incubated at 100 °C for 15 min. After centrifugation at 8000 × g, the pellet was washed three times with water and completely dried. The samples were dissolved in water to make a solution of 25 mg/ml. In total, 5 mg each of cell wall samples were acidified in 6 m HCl at 100 °C for 4 h. Quantification of chitin was conducted by measuring the acid-released glucosamine from chitin using the substrate p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde as a chromogen (35). The absorbance was measured at 520 nm using a BioPhotometer (Eppendorf), and the quantity of glucosamine was calculated in reference to the standard curve established using pure glucosamine (Sigma) (36).

Lectin Binding Assays

To further examine fungal cell well integrity, fungal germlings of the WT and mutants were treated with different fluorescent lectins, including Alexa Fluor 488-labeled concanavalin A (60 μg/ml) for binding α-mannopyranosyl and α-glucopyranosyl residues, lectin II isolated from the legume Griffonia simplicifolia (20 μg/ml; Invitrogen) for binding α- or β-linked GlcNAc, and fluorescein-labeled Galanthus nivalis lectin (20 μg/ml; Vector Labs) for binding α-1,3-mannose (25). Images were taken with a BX51-33P fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Conidial Adhesion and Hydrophobicity Assays

Quantitative adhesion assays were conducted by labeling the fungal spores with FITC and incubating the microtiter plates in the dark for 1 h (25). After removing the unbound cells, the fluorescence of each sample was measured with a Varioskan Flash microplate reader (Thermo Scientific). Variation in spore surface hydrophobicity between the WT and mutants was examined using hexadecane as described previously (26).

Insect Bioassays

Virulence tests were conducted for the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp against newly emerged last-instar larvae of silkworms (Bombyx mori) and wax moths (Galleria mellonella). Topical infections were performed by immersing insect larvae for 30 s in a spore suspension containing 1 × 107 conidia/ml. Each treatment had three replicates with 15 insects each, and the experiments were repeated three times. Mortality was recorded every 12 h. For injection assays to bypass insect cuticle barriers, each insect was injected in the second proleg with 10 μl of a spore suspension containing 1 × 106 conidia/ml. The median lethal time (LT50) was calculated as described previously (34). Dead insects were removed and placed on moist filter paper in Petri dishes. To determine and compare the differences in fungal penetration processes between the WT and mutants, insect cadavers were fixed in Carnoy's solution (60% ethanol, 30% chloroform, and 10% glacial acetic acid), dehydrated in alcohol, and embedded in paraffin wax for cutting (10 μm thick) with a rotary microtome (Leica) (32).

Appressorium Induction and Mycotoxin Quantification

To examine MBZ1 regulation of fungal differentiation, conidia of the WT and mutants were used for infection structure induction. The hind wings from cicada (Cryptotympana atrata) were collected and surface-sterilized in 37% H2O2 for 5 min, washed twice in sterile water, and immersed in a conidial suspension (2 × 107 spores/ml) for 20 s. The inoculated wings were incubated on 0.8% water agar at 25 °C for 24 h. Appressoria were induced on a hydrophobic surface in 1% glycerol-buffered minimum medium (34). To examine whether MBZ1 is involved in regulation of secondary metabolism, the induction, extraction, and quantification of cyclopeptide destruxins were performed as described previously (37).

Protease Activity Assay and Western Blotting

For protease activity assays, conidia of the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp were inoculated in SDB at a final concentration of 106 conidia/ml and incubated at 25 °C for 48 h at 180 rpm. The mycelia were then washed twice with sterile-distilled water, transferred to a basal salt medium supplemented with 1% (w/v) homogenized silkworm pupae, and incubated at 25 °C for 48 h at 180 rpm (27). The alkaline protease activities were assayed using the substrate N-succinyl-Ala2-Pro-Phe p-nitroanilide (Sigma) as described previously (38). The protein concentration of each sample was determined using the Bradford method (34). All experiments were repeated twice, and each sample had three replicates. To confirm protease expression, Western blot analysis was conducted using an antibody against Metarhizium protease PR1A as described previously (39).

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

To compare the differences in cell surface structure between the WT and mutants, fungal conidia were incubated in SDB at 25 °C for 7 days. The harvested mycelia were washed and fixed overnight in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing a final concentration of 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The samples were dehydrated with a series of ethanol solutions (50–100%, v/v) and coated with platinum. Observations were conducted using a field emission scanning electron microscope (Zeiss) operating at 3 kV (40).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

The mycelia from the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp that were harvested from 2-day old SDB cultures and from protease induction medium were used for RNA extraction. The samples were homogenized in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with DNase I (Takara) in a column. cDNA of each sample was generated using an AffinityScript multiple-temperature cDNA synthesis kit (Toyobo). Using the primers for different target genes (Table 1), qRT-PCR analyses were performed using a SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (Takara) with an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The relative expression of each gene was normalized with reference to the expression of the β-tubulin gene (32).

Yeast One-hybrid Tests

For yeast one-hybrid tests, the cDNA sequence of MBZ1 was amplified from a cDNA library with primers 1736HF and 1736HR (Table 1) and cloned into the SpeI and SacI sites of vector pPC86 under the control of the GAL4 promoter to generate plasmid pPC86-MBZ1. To test the ability of MBZ1 to bind to the promoter regions of selected genes, promoter fragments were individually amplified by PCR with different primer pairs (Table 1) and inserted into the XhoI site of the p178 vector to control the lacZ reporter gene (29). The resultant plasmids were named p178-Xpromoter (where X represents each selected gene). pPC86-MBZ1 and each individual p178-Xpromoter were transformed into yeast strain EGY48 using a small-scale yeast transformation protocol (24). To examine the effect of autoactivation, the yeast cells were transformed only with each p178-Xpromoter vector. Positive colonies were selected on appropriate selection plates (Ura/Trp-free synthetic dropout medium with X-gal). A negative control was generated by transforming the yeast cells with vector pPC86-MBZ1 and a blank vector (p178). A positive control was generated by transforming the yeast cells with vector pPC86-OSBZIP58 and p178-HA2, as used in a previous study (29). The blue colonies obtained indicated positive interactions, whereas the white colonies indicated no binding.

RESULTS

Characteristics of MBZ1

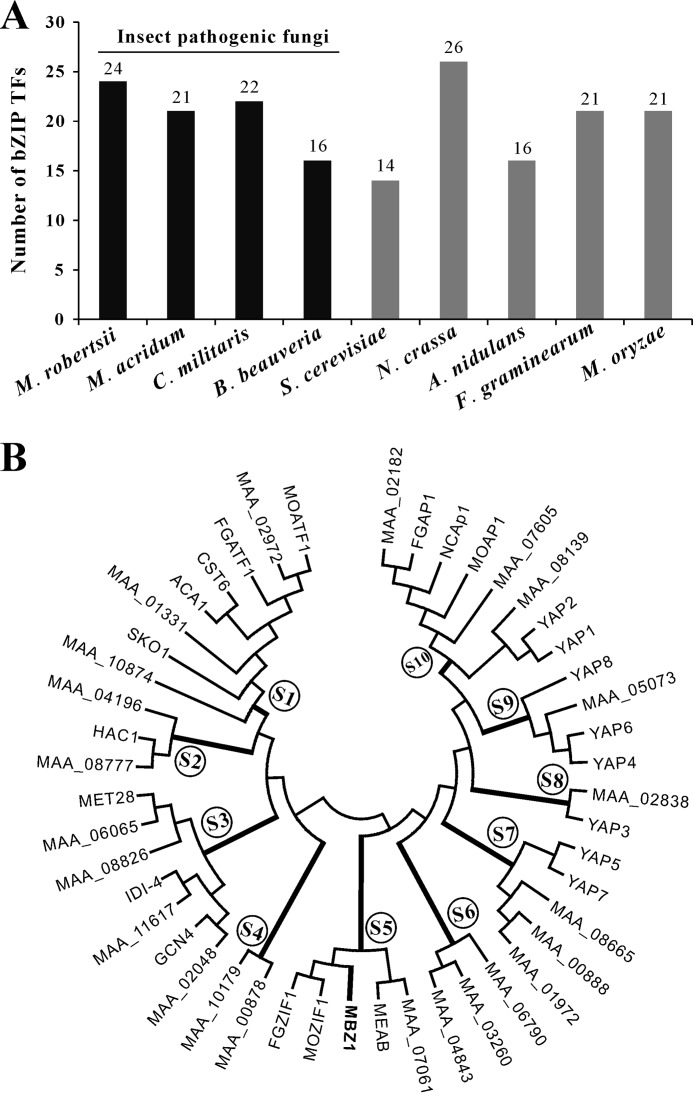

Genome-wide analysis indicated that there are 24 bZIP domain-containing TFs encoded in the genome of M. robertsii, whereas 14–26 bZIP-type TFs are present in yeast and other fungi (Fig. 1A). Overall, the number of bZIP TFs present in fungi are >2-fold fewer than those found in humans (56 bZIP genes) and plants (e.g. 75 in Arabidopsis, 89 in rice, and 125 in maize) (4). A phylogenetic analysis based on the bZIP domain sequences indicated that M. robertsii bZIP-type TFs could be classified into at least 10 subfamilies (Fig. 1B). Subfamilies 4–6 have no homologs in yeast. The MBZ1 protein belongs to subfamily 5 and shares higher homology with its counterparts FGZIF1 (FGSG_01555, 57% identity) of F. graminearum and MOZIF1 (MGG_03288, 45% identity) of M. oryzae (10), but is only moderately homologous to MeaB (AN4900, 11% identity) of A. nidulans (7). All these TFs belong to subfamily 5 (Fig. 1B). In particular, subfamily 1 contains the yeast proteins CST6, ACA1, and SKO1 (Fig. 1B), which belong to the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) family of bZIP-type TFs that bind the consensus palindromic site 5′-TGACGTCA-3′ (41).

FIGURE 1.

Genome-wide distribution and phylogeny analysis of bZIP-type TFs. A, distribution of bZIP-type TFs in the genomes of selected fungal species. black bars indicate insect pathogenic fungi, whereas gray bars indicate non-insect pathogenic fungi. B, phylogenetic analysis of bZIP-type TFs from M. robertsii and S. cerevisiae and those that have been functionally studied in different fungi.

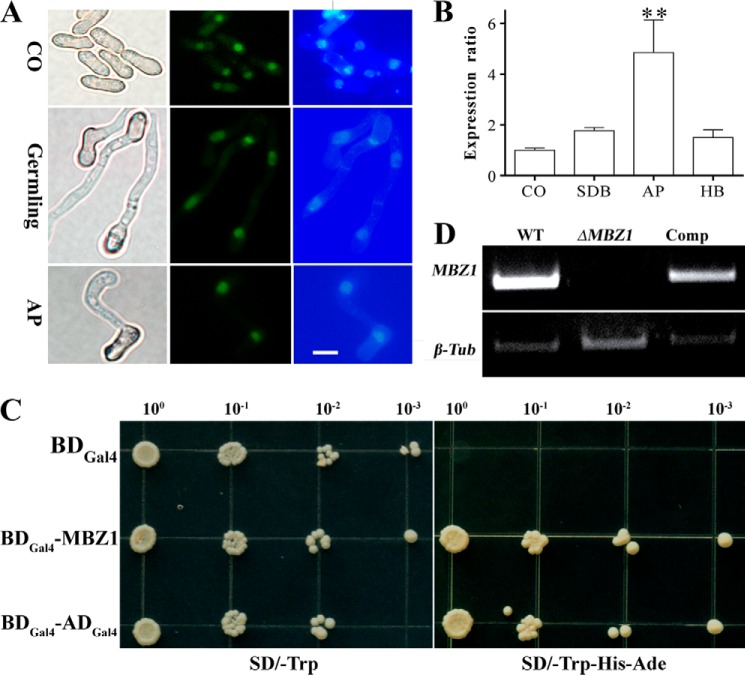

To verify the nuclear localization of MBZ1, a GFP gene was fused with the 5′ terminus of MBZ1 for transformation of M. robertsii. Fluorescence microscopy examinations verified that the GFP signal could be detected only in the nuclei of fungal spores, germlings, and appressoria of M. robertsii (Fig. 2A). Consistent with our previous RNA-seq analysis (16), a qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that MBZ1 was most highly transcribed by the fungus during infection structure appressorium formation compared with the stages of fungal conidiation, saprophytic growth, and differentiation of hyphal bodies (blastospores formed in the insect body cavity) (Fig. 2B). A transcriptional activation test indicated that, relative to a negative control, yeast cells transformed with a vector containing MBZ1 cDNA could survive on an auxotrophic medium, as could the positive control yeast cells engineered with a GAL4 activation domain (Fig. 2C). The results thereby confirmed the typical TF characteristics of MBZ1: nuclear localization and transcriptional activation.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of MBZ1 and verification of gene deletion. A, localization assay of the MBZ1 protein in M. robertsii. GFP-MBZ1 is localized in the nuclei of conidia (CO), germlings (spores germinated in SDB for 18 h), and appressoria (AP; formed on hydrophobic surface 18 h post-inoculation) as shown by co-localization with florescent Hoechst staining. Scale bar = 5 μm. B, qRT-PCR analyses of MBZ1 expression by the fungus at the stages of conidiation, saprophytic growth in SDB, appressorium formation, and hyphal body (HB) formation in insect hemolymph. **, p < 0.01. C, transcriptional activation tests in yeast. Yeast strain AH109 carrying fusion cassettes of the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBGal4; negative control), the GAL4 DNA-binding and activation domains (DBGal4-ADGal4; positive control), or MBZ1 were cultured on synthetic dropout (SD) medium at 30 °C for 3 days. D, verification of MBZ1 gene deletion by RT-PCR. The fungi were grown in SDB for 48 h and used for RNA extraction for analysis. A β-tubulin gene (β-Tub) was used as a reference.

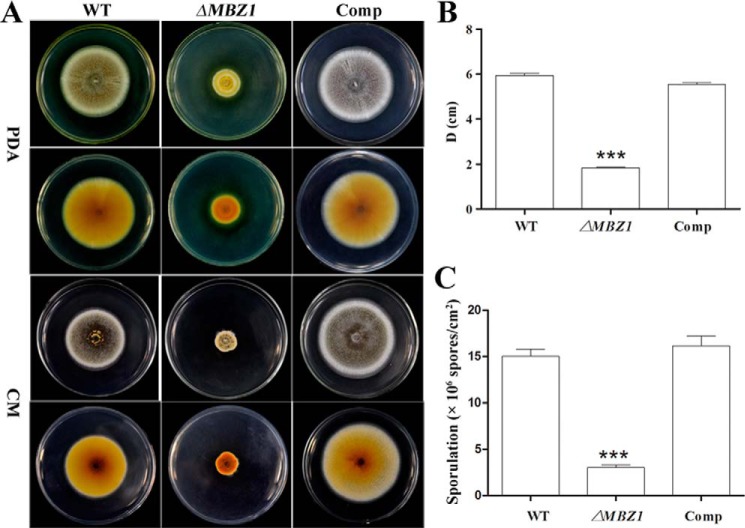

Gene Deletion and Phenotype Characterization

To study gene function, MBZ1 was disrupted via homologous replacement. The null mutant was complemented with the full MBZ1 ORF and designated Comp, which was verified by PCR and RT-PCR analyses. In contrast to the WT and Comp strains, MBZ1 gene transcription was eliminated in ΔMBZ1 (Fig. 2D). Growth assays revealed that ΔMBZ1 showed impaired growth and sporulation on PDA and complete mineral medium after 2 weeks of growth (Fig. 3A). Relative to the WT (5.93 ± 0.75 cm) and Comp (5.53 ± 1.04 cm), the colony diameter of ΔMBZ1 (1.83 ± 0.27 cm) was reduced significantly (p < 0.001) after incubation on PDA (Fig. 3B). In addition, the sporulation of ΔMBZ1 ((3.03 ± 0.04) × 106 conidia/cm2) was also significantly impaired (p < 0.001) compared with the WT ((14.99 ± 0.09) × 106 conidia/cm2) and Comp ((16.14 ± 0.09) × 106 conidia/cm2) (Fig. 3C). Deletion of MBZ1 also altered culture pigmentation, i.e. ΔMBZ1 (but not the WT and Comp) accumulated yellow pigments in its mycelia when grown on PDA (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 3.

MBZ1 is required for normal growth and sporulation in M. robertsii. A, phenotypic variation. Cultures of the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp were grown on PDA and complete mineral medium (CM) for 14 days. B, colony diameter (D) variations among different cultures. Error bars represent S.E. from three replicates. C, variation in spore production by the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp after growing the fungi on PDA for 2 weeks. ***, p < 0.001.

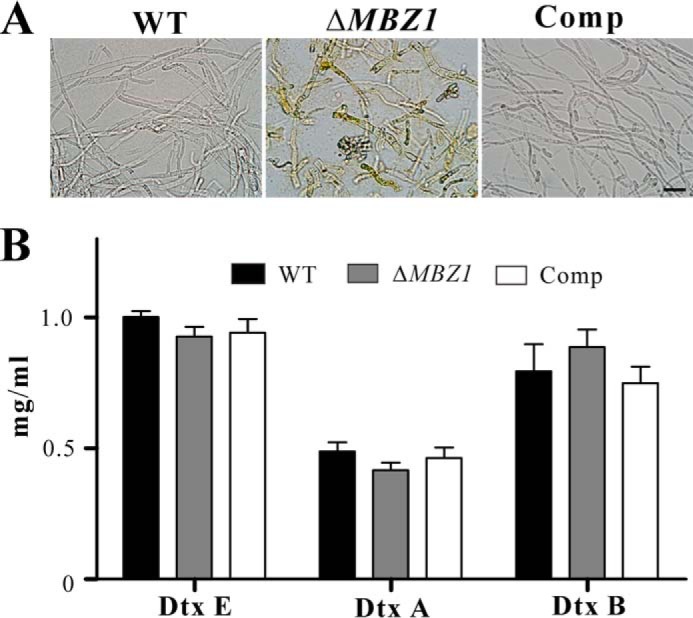

FIGURE 4.

A, mycelia of the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp on PDA after 2 weeks of growth. Scale bar = 20 μm. B, quantification and comparison of cyclopeptide destruxins (Dtx) produced by the WT and mutants. The results indicate no significant differences between the WT and mutants, suggesting that MBZ1 is not involved in controlling destruxin production.

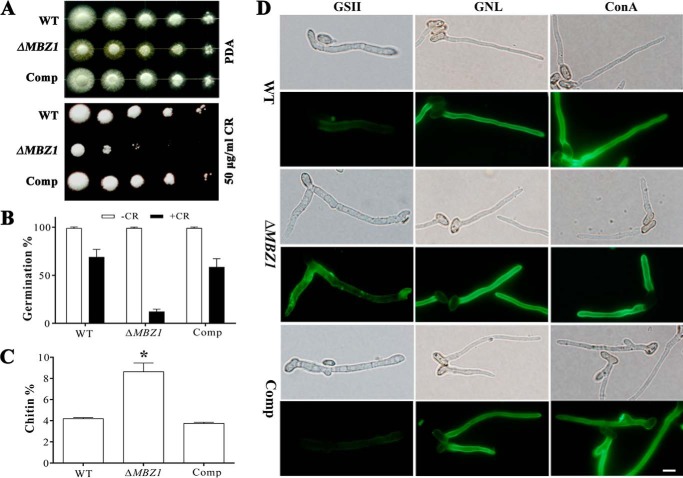

Deletion of MBZ1 Impairs Cell Wall integrity

We performed experiments to test the sensitivities of the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp in response to different cell wall stressors or biosynthesis inhibitors. The observations indicated that the MBZ1 null mutant (but not the WT and Comp) lost the ability to grow on PDA supplemented with Congo red (Fig. 5A). However, no significant differences were found between the WT and mutants regarding growth in the presence of tunicamycin, Calcofluor White, amphotericin B, CuSO4, sorbitol, DTT, or SDS (data not shown). Congo red also inhibited mutant spore germination in SDB. Relative to the WT (68.89 ± 7.83%) and Comp (58.40 ± 8.90%), the germination rates of ΔMBZ1 spores (11.95 ± 2.80%) were significantly reduced (p < 0.001) after incubation for 24 h (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Impairment of cell wall integrity. A, effect of the cell wall inhibitor Congo red (CR) on fungal growth. Two microliters of 10-fold serial dilutions of spore suspensions (5 × 107 conidia/ml) were inoculated on PDA plates with or without Congo red and incubated at 28 °C for 72 h. B, germination rates of the WT and mutants in SDB with or without Congo red (50 μg/ml) 24 h post-inoculation. Error bars represent S.E. from three replicates. C, chitin quantification. Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. from two independent experiments, and each treatment had three replicates. *, p < 0.05. D, fluorescence lectin staining. Conidia of the WT and mutants were germinated in SDB for 12 h before staining with G. simplicifolia lectin II (GSII), G. nivalis lectin (GNL), and concanavalin A (ConA). Scale bar = 5 μm.

As indicated above, ΔMBZ1 became sensitive to Congo red, but not Calcofluor White. We speculated that the cell wall components, especially the chitin content, would be altered in the MBZ1 null mutant. To test this, we performed a chitin quantification assay, which revealed that the level of chitin in the ΔMBZ1 cell wall (8.62 ± 0.82%) was significantly increased (p < 0.05) compared with the WT (4.19 ± 0.95%) and Comp (3.74 ± 0.11%) (Fig. 5C). In addition, we performed cell wall binding assays with concanavalin A, G. simplicifolia lectin II, and G. nivalis lectin (24, 25). The results demonstrated a stronger fluorescent signal for ΔMBZ1 cells when stained with G. simplicifolia lectin II, suggesting again a higher level of chitin accumulation compared with the WT and Comp. No apparent differences were found between the WT and mutants for the treatments with concanavalin A and G. nivalis lectin (Fig. 5D).

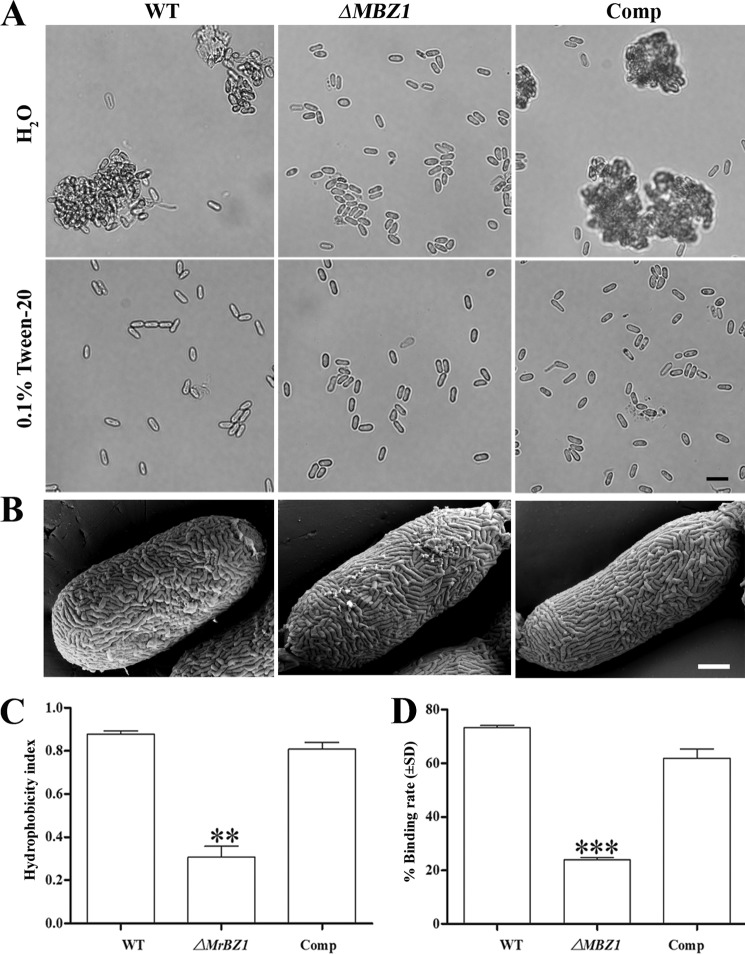

Impairment of Conidial Hydrophobicity and Adherence to Hydrophobic Surface

Consistent with the impairment of cell wall integrity, the hydrophobicity defect in the ΔMBZ1 spores was also found during the preparation of spore suspensions. Thus, unlike the WT and Comp, ΔMBZ1 conidia were more readily dispersible in water without the detergent Tween 20 (Fig. 6A). Ultrastructure examinations of spore surface features did not reveal any morphological difference between the WT and mutants (Fig. 6B). However, the measurements of cell surface hydrophobicity indicated that the hydrophobicity index of ΔMBZ1 spores (0.39 ± 0.09) was significantly reduced (p < 0.01) compared with the WT (0.88 ± 0.02) and Comp (0.81 ± 0.05) (Fig. 6C). In addition, a quantitative assay of cell adhesion ability demonstrated that ΔMBZ1 had a significantly impaired capacity (p < 0.001) to bind to a hydrophobic surface compared with the WT and Comp (Fig. 6D).

FIGURE 6.

Analyses of spore hydrophobicity and adherence ability. A, variation in spore dispersal ability between the WT and mutants in water and 0.1% Tween 20. Scale bar = 10 μm. B, spore surface structures examined by field emission scanning electron microscopy analysis. Scale bar = 1 μm. C, variation in spore surface hydrophobicity between the WT and mutants. **, p < 0.01, WT (or Comp) versus ΔMBZ1. D, variation in spore ability to adhere to hydrophobic surfaces between the WT and mutants. ***, p < 0.001, WT (or Comp) versus ΔMBZ1.

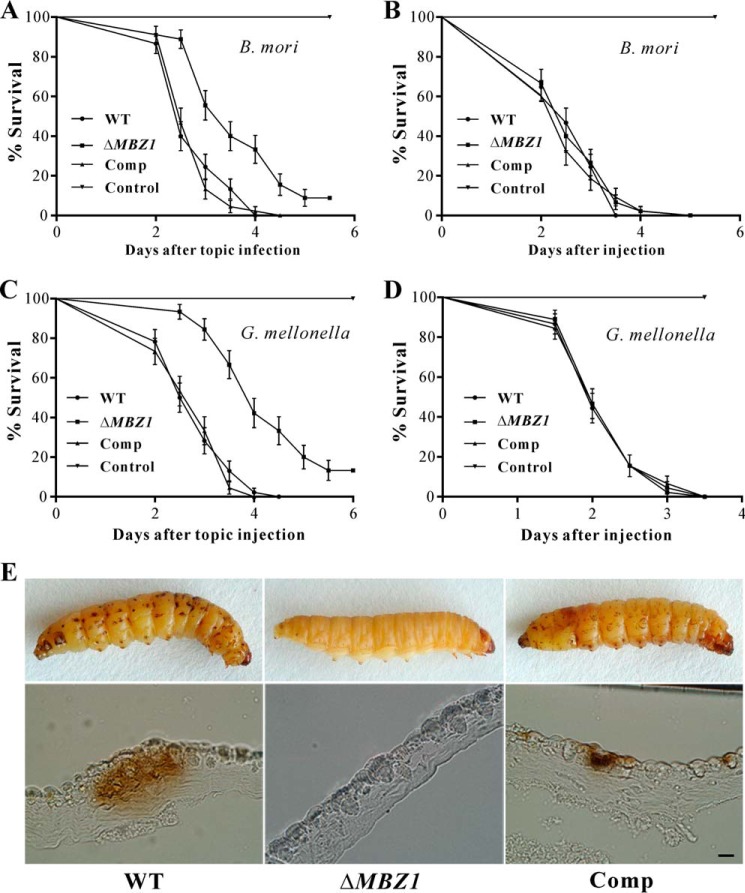

Deletion of MBZ1 Impairs Fungal Virulence

To examine the effect of MBZ1 deletion on fungal virulence, we performed both topical infection and injection bioassays with last-instar silkworm and wax moth larvae. The LT50 values were estimated and compared among the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp. After topical infection of silkworms, the differences were significant between the WT (LT50 = 2.8 ± 0.09 days) and ΔMBZ1 (LT50 = 3.9 ± 0.13 days) (χ2 = 25.12, p < 0.0001) and between ΔMBZ1 and Comp (LT50 = 2.8 ± 0.08 days) (χ2 = 29.33, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 7A). However, there was no significant difference in injection assays among the WT (LT50 = 2.8 ± 0.10 days), ΔMBZ1 (LT50 = 2.7 ± 0.10 days), and Comp (LT50 = 2.7 ± 0.10 days) (p > 0.5) (Fig. 7B). Similar patterns were observed during the topical infection and injection assays using the wax moth larvae (Fig. 7, C and D). Thus, MBZ1 is required for the virulence of M. robertsii by playing a role in fungal adhesion to and penetration of the insect cuticle. The results are consistent with the qRT-PCR data that the expression of MBZ1 was highly activated by the fungus during early infection, but not during growth in insect blood (Fig. 2B). In support of this, the melanization spots characteristic of fungal penetration were not evident on the insects topically treated with the ΔMBZ1 spores, but were abundant on the insects treated with the WT and Comp conidia 48 h post-inoculation (Fig. 7E).

FIGURE 7.

Insect bioassays. A, survival of silkworm larvae following topical infection with the spore suspensions (1 × 107 spores/ml) of the WT and mutants. B, survival of silkworm larvae following injection with the spore suspensions (10 μl, 1 × 106 spores/ml) of the WT and mutants. Control insects were treated with sterile water. C, survival of wax moth larvae following topical infection with the spore suspensions (1 × 107 spores/ml). D, survival of wax moth larvae following injection with the spore suspensions (10 μl, 1 × 106 spores/ml). Control insects were treated with sterile water. Error bars represent S.D. E, impairment of topical infection in ΔMBZ1. The wax moth larvae were topically infected for 48 h and embedded for cutting and microscopic observations. Relative to the WT and Comp, many fewer melanization spots were observed on the insects treated with ΔMBZ1 spores. Scale bar = 1 mm.

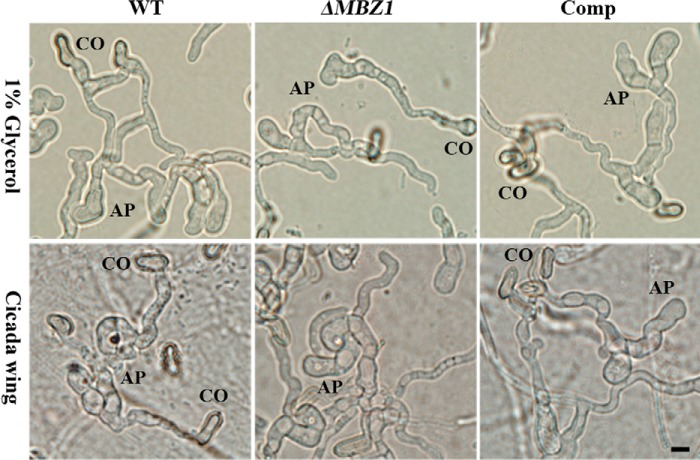

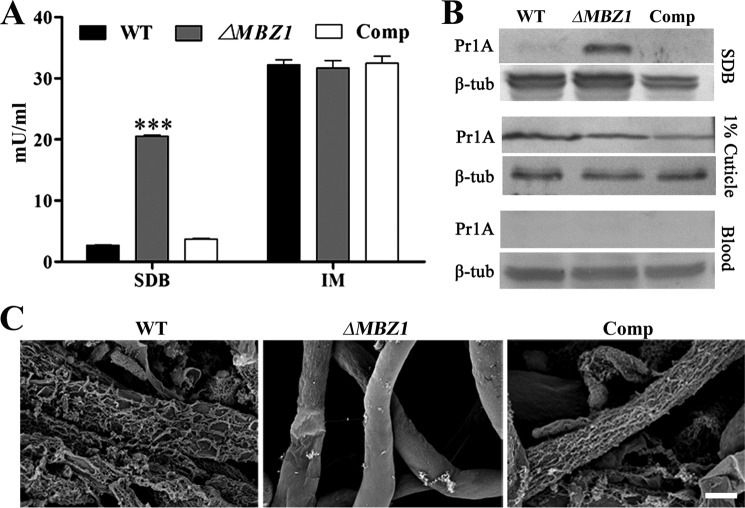

Negative Regulation of Protease Activity

The impact of MBZ1 deletion on spore adhesion and hydrophobicity contributes to virulence defects in ΔMBZ1. To examine whether any other virulence factors were affected, we performed infection structure induction. The results indicated that the spores of ΔMBZ1 could similarly form appressoria like the WT and Comp on both hydrophobic surfaces and insect cuticles (Fig. 8). In addition, we found that the biosynthesis of insecticidal cyclopeptide destruxins was not affected in ΔMBZ1 compared with the WT and Comp (Fig. 4B). We also tested the expression of cuticular degradation proteases. After growth in SDB for 48 h, unexpectedly, the subtilisin-like protease activity of ΔMBZ1 was significantly increased (p < 0.001) compared with the WT and Comp. However, the differences were not significant among the isolates when they were grown in the inductive medium containing insect homogenates (Fig. 9A). These observations were confirmed by Western blot analysis using an antibody against PR1A, an extracellular protease (Fig. 9B). In addition, consistent with a previous analysis (42), the expression of proteases was switched off in both the WT and ΔMBZ1 when the fungi were grown in insect blood (Fig. 9B). These findings suggest that MBZ1 is involved only in the negative control of protease expression during fungal saprophytic growth in artificial and nutrient-rich media, but not in insect component-containing substrates. This was further evidenced when the cell surface mucilage-like structures found in ΔMBZ1 (but not in the WT and Comp) were self-digested when grown in SDB (Fig. 9C). This phenotype is similar to fungal cell autolysis (43).

FIGURE 8.

Appressorium induction. The conidia (CO) of the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp were inoculated on hydrophobic surfaces (upper panels) or cicada hind wings (lower panels) and incubated for 24 h for appressorium (AP) induction. Scale bar = 5 μm.

FIGURE 9.

Up-regulation of proteases in ΔMBZ1. A, protease activity assay. The spores of the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp were cultured in SDB and inductive medium (IM; 1% cuticle) for 48 h, and the supernatants were harvested for protease activity assay. ***, p < 0.001. B, Western blot analysis. The supernatant samples from A and insect blood (hemolymph) collected 48 h after injection with fungal spores were used for analysis with the anti-PR1A protease polyclonal antibody. C, Examination of cell surface structure. The spores of the WT, ΔMBZ1, and Comp were cultured in SDB for 7 days, and the mycelia were harvested, washed twice with distilled water, and used for field emission scanning electron microscopy microscope analysis. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Verification of Transcriptional Control of Target Genes

As indicated above, the cell wall integrity of ΔMBZ1 was impaired, and expression of proteases was activated in artificial medium. To verify the control of downstream genes by MBZ1, the putatively targeted genes were selected for qRT-PCR analysis and yeast one-hybrid tests for promoter binding. These included the cell wall biosynthesis-related genes, protease genes, and the adhesin gene MAD1 (Table 2). After growth in SDB for 48 h, the putative β-1,3-glucanosyltransglycosylases (MAA_01794, similar to yeast GAS2, 39% identity; and MAA_02558, similar to yeast GAS3, 39% identity) and cell wall glucanosyltransferases (MAA_02062 and MAA_04636, both similar to the yeast chitin transglycosylase CRH1 with 44 and 31% identities, respectively) were significantly down-regulated in ΔMBZ1 compared with the WT (Table 3). In contrast, the gene MAA_07202, which is highly similar to the yeast glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase GFA1 (60% identity) involved in chitin biosynthesis (44, 45), was up-regulated by >6-fold in ΔMBZ1 (Table 3). The adhesin MAD1 (MAA_03775) mediates conidial adherence to hydrophobic surface in Metarhizium (46). Relative to the WT, the MAD1 gene was down-regulated by 4-fold in ΔMBZ1. This was therefore consistent with the defect of spore adherence ability in ΔMBZ1 (Fig. 6C). Consistent with the increase in protease activity in SDB (Fig. 9, A and B), the subtilisin-like protease genes, e.g. the PR1A gene (MAA_05675), were significantly up-regulated in ΔMBZ1 compared with the WT (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Information of selected putative target genes for qRT-PCR and yeast one-hybrid analyses

NA, not available.

| Gene | Description | Yeast homolog (% identity) | Primers for qRT-PCR/yeast one-hybrid analyses |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAA_01794 | β-1,3-Glucanosyltransglycosylases | GAS2 (39%), GAS1 (36%) | 1794F, 1794R/1794YF, 1794YR |

| MAA_02558 | β-1,3-Glucanosyltransglycosylases | GAS3 (39%), GAS4 (38%), GAS5 (35%) | 2558F, 2558R/2558YF, 2558YR |

| MAA_04636 | Cell wall glucanosyltransferase | CRH1 (44%) | 4636F, 4636R/4636YF, 4636YR |

| MAA_02062 | Cell wall glucanosyltransferase | CRH1 (31%) | 2062F, 2062R/2062YF, 2062YR |

| MAA_07202 | Glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase | GFA1 (60%) | 7202F, 7202R/7202YF, 7202YR |

| MAA_02408 | Subtilisin-like serine protease PR1J | NA | 2408F,2408R/2408YF, 2408YR |

| MAA_05675 | Subtilisin-like serine protease PR1A | NA | 5675F, 5675R/5675YF, 5675YR |

| MAA_10246 | Subtilisin-like protease | NA | 10246F, 10246R/10246YF, 10246YR |

| MAA_10260 | Subtilisin-like protease PR1H | NA | 10260F, 10260R/10260YF, 10260YR |

| MAA_03775 | Adhesin protein MAD1 | NA | 3775F, 3775R/3775YF, 3775YR |

TABLE 3.

Differential expression of selected genes by the WT and mutants of M. robertsii

The fungi were grown in SDB, or newly harvested conidia were used for RNA extraction and subsequent qRT-PCR analysis. A β-tubulin gene was used as a reference.

| Gene | WT | ΔMBZ1 | Comp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell wall-associated genes | |||

| MAA_02558 | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 0.079 ± 0.048a | 1.36 ± 0.51 |

| MAA_01794 | 0.013 ± 0.0013 | 0.0021 ± 0.00016a | 0.020 ± 0.0023 |

| MAA_07404 | 0.22 ± 0.057 | 0.019 ± 0.00060a | 0.29 ± 0.013 |

| MAA_04636 | 10.08 ± 0.75 | 0.82 ± 0.042a | 16.20 ± 3.97 |

| MAA_07202 | 0.70 ± 0.12 | 4.73 ± 0.81a | 0.92 ± 0.27 |

| Adhesin MAD1 | |||

| MAA_03775 | 1.00 ± 0.21 | 0.25 ± 0.095a | 1.78 ± 0.94 |

| Subtilisin protease genes | |||

| MAA_02048 | 1.00 ± 0.18 | 6.58 ± 0.65b | 2.97 ± 0.62 |

| MAA_05675 | 2.44 ± 0.25 | 26.13 ± 2.36b | 6.23 ± 1.02 |

| MAA_10246 | 0 | 0.33 ± 0.04b | 0 |

| MAA_10260 | 0 | 11.88 ± 1.36b | 0 |

a p < 0.05 between ΔMBZ1 and WT or between ΔMBZ1 and Comp.

b p < 0.01 between ΔMBZ1 and WT or between ΔMBZ1 and Comp.

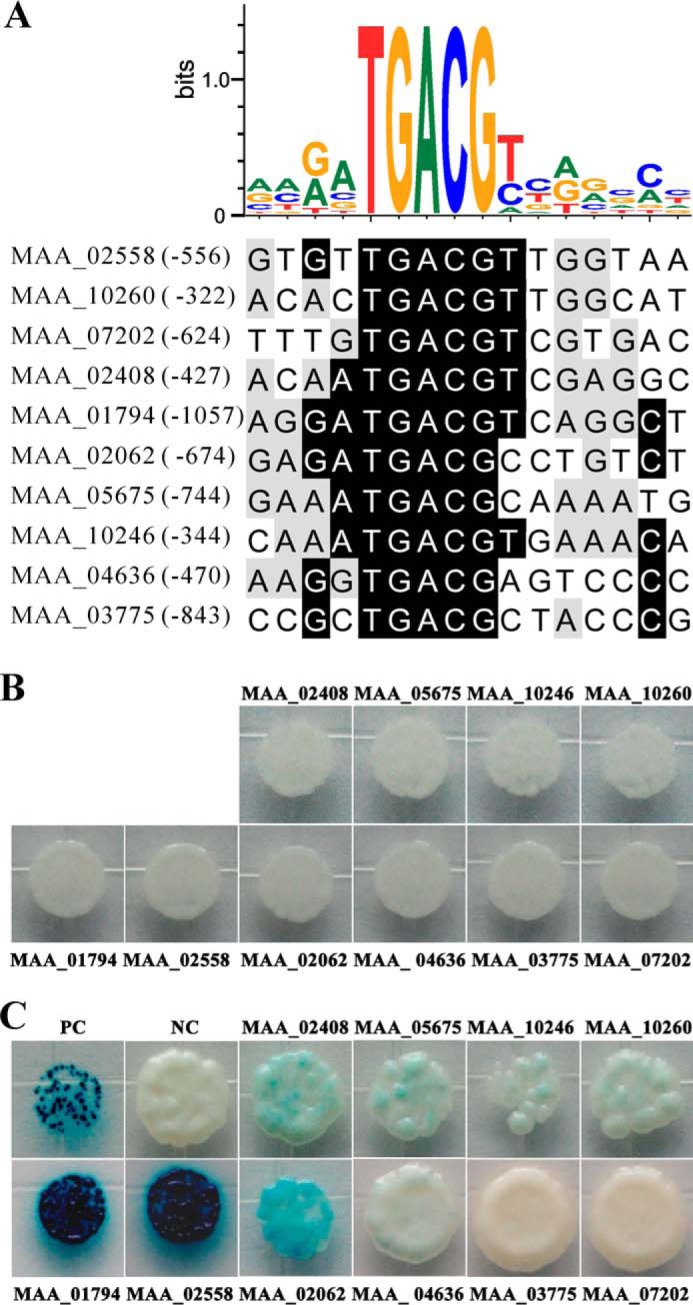

In silico analysis identified the presence of the conserved motif 5′-TGACG-3′ in the promoter regions of all selected genes (Fig. 10A), which is the functional half-site of the CREB-targeting palindrome (5′-TGACGTCA-3′) (47), suggesting that MBZ1 is also the CREB site or half-site activator. Heterologous expression of MBZ1 in Escherichia coli failed to obtain soluble protein for the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. To verify the binding of MBZ1 to the promoter regions of these target genes, we performed yeast one-hybrid assays. The yeast cells transformed with only the individual promoter region could not express β-galactosidase, i.e. the preclusion of self-activation (Fig. 10B). Except for the promoters of MAD1 and the GFA1-like gene (MAA_07202), the β-galactosidase activity was activated by MBZ1 when under the control of the selected gene promoters (Fig. 10C). However, consistent with a previous report (28), the reporter enzyme activity varied among the controls with different gene promoters. The highest binding and activation activities were observed for MBZ1 toward the GAS2 (MAA_01794) and GAS3-like (MAA_02558) genes (Fig. 10C). Interestingly, the full CREB site is present in the promoter of MAA_01794, but it is the 5′-TGACGTTG-3′ for MAA_02558 (Fig. 10A).

FIGURE 10.

Analysis of putative MBZ1-binding site and yeast one-hybrid tests. A, identification of the consensus binding site present in the promoter regions of target genes. B, autoactivation tests. Yeast cells transformed with only the p178 vector containing each individual promoter did not show autoactivation activities. C, verification of transcription control of target genes by MBZ1 in yeast. Yeast cells were transformed with both the p178 vector containing each individual promoter and plasmid pPC86-MBZ1 containing MBZ1 cDNA. PC, positive control; NC, negative control.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized the functions of the bZIP-type TF MBZ1 in the insect pathogenic fungus M. robertsii. Gene deletion, biochemical analyses, and insect bioassays indicated that MBZ1 contributes to the regulation of fungal growth, conidiation, cell wall integrity, and virulence. Enzyme activity, Western blotting, and qRT-PCR analyses demonstrated that MBZ1 is involved in both the positive and negative transcriptional control of various target genes, which is similar to the regulation pattern of the C2H2-type pH-responsive regulator of M. robertsii (32). Similar to virulence defects in gene deletion mutants of FGZIF1 in F. graminearum and MOZIF1 in M. oryzae (10), ΔMBZ1 was impaired in killing insects. Interestingly, ΔFGZIF1 does not show defects in maintenance of cell wall integrity (i.e. not sensitive to Congo red), conidiation, and growth (10). This is in contrast to our observations for ΔMBZ1, which suggests that, in addition to the functional divergence of paralogous bZIP-type TFs (15), the orthologous TFs could play divergent roles in different organisms. Deletion of the bZIP-type TF gene FGAP1 does not affect the pathogenicity of F. graminearum to wheat (11), but loss of the orthologous gene MOAP1 in M. oryzae completely abolishes its pathogenicity to rice (14). Likewise, other studies have found that the null mutants of MOATF1 of M. oryzae and FGATF1 of F. graminearum have reduced virulence, but the former are more sensitive to oxidative stress (12, 13). We also observed that deletion of MBZ1 affected fungal pigmentation (Figs. 3A and 4A), but not production of insecticidal mycotoxin destruxins (Fig. 4B). In F. graminearum, however, deletion of FGZIF1 significantly impairs fungal production of the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol (a type B trichothecene) (10). Thus, the functional divergence of these orthologs in the different fungal species would question the assumption of ortholog conjecture, which suggests that orthologous genes carry out equivalent biological functions in different organisms (48). However, it remains to be determined whether the orthologs from plant pathogens could fully complement the phenotypes of ΔMBZ1 in M. robertsii.

The teleomorph of Metarhizium spp. is considered to be Metacordyceps spp.; however, their heterothallic sexual cycles are largely cryptic (49). Future studies are still required to investigate whether MBZ1 is involved in controlling sexuality in M. robertsii as FGZIF1 and FGATF1 control sex cycles in F. graminearum (10, 12). The fungal cell wall plays essential roles in mediating growth, stress resistance, cell adhesion to hosts, and infection (50). We found that deletion of MBZ1 led to the down-regulation of GH72-like genes (MAA_01794 and MAA_02558) and yeast CRH1-like genes (MAA_02062 and MAA_04636), but led to the up-regulation of the GFA1-like gene MAA_07202. The GH72 family of glycosidases/transglycosidases plays important roles in cell wall maintenance (51). Deletion mutants of these genes have defects in cell adherence to hydrophobic surfaces and increases in chitin in the cell wall (52, 53). The yeast chitin transglycosylase CRH1 acts to transfer chitin and cross-link it to β-1,3- and β-1,6-glucans in the cell wall (54), and GFA1 contributes to the first step of chitin biosynthesis (44). Relative to the WT, differential regulation of these genes would be responsible for chitin accumulation in the ΔMBZ1 cell wall and therefore the increased sensitivity to the chitin-specific dye Congo red (Fig. 5A). However, the Congo red sensitivity was not observed for ΔFGZIF1 (10), but it was observed for ΔFGATF1 of F. graminearum (12). This is again suggestive of the functional divergence of orthologous bZIP TFs among different species. In Candida albicans, deletion of the GH72-like PHR2 gene (homologous to yeast GAS2 and GAS3) additionally results in sporulation failure (52, 53). Thus, the down-regulation of GH72-like genes could contribute, at least in part, to the defective conidiogenesis in ΔMBZ1 (Fig. 3). However, it remains to be determined how MBZ1 is involved in mediating mycelial growth in M. robertsii; the effect has not been observed for its counterpart FGZIF1 in F. graminearum (10).

We tested virulence via both topical infection and injection assays against two different insect species and found that differences were observed only between the WT and ΔMBZ1 with topical infections (Fig. 7), suggesting that the null mutant can evade host immunity within the insect hemocoel as well as the WT. Because ΔMBZ1 could successfully produce the infection structure appressorium (Fig. 8), failure to bind to the insect cuticle would be mainly responsible for the defective virulence in ΔMBZ1 due to the reduction of its surface hydrophobicity and adherence ability. This resembles the effect of deletion of the adhesin MAD1 gene in M. robertsii (46). The subtilisin proteases are the key virulence factors of insect pathogenic fungi for degradation of insect cuticular proteins (42). Overexpression of the protease PR1A increases fungal virulence and causes extensive melanization of infected insects due to the activation of insect prophenoloxidases (39, 55). Interestingly, the up-regulation of proteases in ΔMBZ1 was observed only when the fungus was grown in artificial medium, but not in insect component-related conditions. This was particularly clear when proteases were successfully switched off in insect hemolymph (Fig. 9B). The result suggests that there are additional TFs involved in fine-tuning protease expression in M. robertsii. In filamentous fungi, the Zn2Cys6 domain-containing TF PrtT has been characterized as an activator of extracellular proteases (56). A homolog of Aspergillus PrtT is also present in the genome of M. robertsii (MAA_09737, 24% identity) (16). Thus, the mechanisms used by MBZ1 to regulate protease expression, as well as the possible interactions between MBZ1 and other TFs, remain to be clarified.

The formation of either homodimers or heterodimers is the hallmark of bZIP-type TFs, which allows them to increase the complexity of regulatory networks (2). Our results indicate that deletion of MBZ1 resulted in up-regulation of a GFA1-like gene (MAA_07202) and down-regulation of the adhesin gene in M. robertsii (Table 3). Cell adhesion assays also revealed the significantly reduced ability of ΔMBZ1 spores to bind to hydrophobic surfaces (Fig. 6D). The CREB half-site is present in the promoter regions (Fig. 10A); however, yeast one-hybrid assays showed that MBZ1 did not bind to the promoter regions of MAD1 and the GFA1-like gene (Fig. 10C). Precluding the possibility of a technical false-negative or false-positive issue, the findings suggest the possible formation of heterodimerized MBZ1 in the regulation of these genes, i.e. the indirect control of these target genes. The putative partner involved in dimerization with MBZ1 remains to be determined.

In conclusion, we characterized the bZIP-type TF MBZ1 in an insect pathogenic fungal model and established that the MBZ1 gene is required for virulence against insects by mediating cell wall integrity, cell surface hydrophobicity, and adherence to hydrophobic surfaces. Both negative and positive regulation of various target genes was evident, indicating that MBZ1 can function as either an activator or a suppressor. The results of this study also reveal the functional divergence of orthologous bZIP-type TFs in different fungal species, highlighting the need to elucidate orthologous gene function in different organisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian R. Lovett (University of Maryland) for critical reading of this manuscript and Xiaoyan Gao for help with the imaging analyses.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 31225023 and Chinese Academy of Sciences Strategic Priority Research Program Grant XDB11030100.

- TF

- transcription factor

- bZIP

- basic leucine zipper

- PDA

- potato dextrose agar

- SDB

- Sabouraud dextrose broth

- Comp

- complemented mutant

- LT50

- median lethal time

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- CREB

- cAMP response element-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wagner E. F. (2001) AP-1–introductory remarks. Oncogene 20, 2334–2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amoutzias G. D., Veron A. S., Weiner J., 3rd, Robinson-Rechavi M., Bornberg-Bauer E., Oliver S. G., Robertson D. L. (2007) One billion years of bZIP transcription factor evolution: conservation and change in dimerization and DNA-binding site specificity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 827–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Landschulz W. H., Johnson P. F., McKnight S. L. (1988) The leucine zipper: a hypothetical structure common to a new class of DNA binding proteins. Science 240, 1759–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Llorca C. M., Potschin M., Zentgraf U. (2014) bZIPs and WRKYs: two large transcription factor families executing two different functional strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moye-Rowley W. S., Harshman K. D., Parker C. S. (1989) Yeast YAP1 encodes a novel form of the Jun family of transcriptional activator proteins. Genes Dev. 3, 283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fernandes L., Rodrigues-Pousada C., Struhl K. (1997) Yap, a novel family of eight bZIP proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae with distinct biological functions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 6982–6993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Polley S. D., Caddick M. X. (1996) Molecular characterisation of meaB, a novel gene affecting nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. FEBS Lett. 388, 200–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yin W. B., Reinke A. W., Szilágyi M., Emri T., Chiang Y. M., Keating A. E., Pócsi I., Wang C. C., Keller N. P. (2013) bZIP transcription factors affecting secondary metabolism, sexual development and stress responses in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiology 159, 77–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tian C., Li J., Glass N. L. (2011) Exploring the bZIP transcription factor regulatory network in Neurospora crassa. Microbiology 157, 747–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Y., Liu W., Hou Z., Wang C., Zhou X., Jonkers W., Ding S., Kistler H. C., Xu J. R. (2011) A novel transcriptional factor important for pathogenesis and ascosporogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24, 118–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Montibus M., Ducos C., Bonnin-Verdal M. N., Bormann J., Ponts N., Richard-Forget F., Barreau C. (2013) The bZIP transcription factor Fgap1 mediates oxidative stress response and trichothecene biosynthesis but not virulence in Fusarium graminearum. PLoS ONE 8, e83377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jiang C., Zhang S., Zhang Q., Tao Y., Xu J. R. (2014) FgSKN7 and FgATF1 have overlapping functions in ascosporogenesis, pathogenesis, and stress responses in Fusarium graminearum. Environ. Microbiol. 10.1111/1462-2920.12561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo M., Guo W., Chen Y., Dong S., Zhang X., Zhang H., Song W., Wang W., Wang Q., Lv R., Zhang Z., Wang Y., Zheng X. (2010) The basic leucine zipper transcription factor Moatf1 mediates oxidative stress responses and is necessary for full virulence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 1053–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo M., Chen Y., Du Y., Dong Y., Guo W., Zhai S., Zhang H., Dong S., Zhang Z., Wang Y., Wang P., Zheng X. (2011) The bZIP transcription factor MoAP1 mediates the oxidative stress response and is critical for pathogenicity of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1001302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang W., Ru Y., Hong L., Zhu Q., Zuo R., Guo X., Wang J., Zhang H., Zheng X., Wang P., Zhang Z. (2014) System-wide characterization of bZIP transcription factor proteins involved in infection-related morphogenesis of Magnaporthe oryzae. Environ. Microbiol. 10.1111/1462-2920.12618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gao Q., Jin K., Ying S. H., Zhang Y., Xiao G., Shang Y., Duan Z., Hu X., Xie X. Q., Zhou G., Peng G., Luo Z., Huang W., Wang B., Fang W., Wang S., Zhong Y., Ma L. J., St. Leger R. J., Zhao G. P., Pei Y., Feng M. G., Xia Y., Wang C. (2011) Genome sequencing and comparative transcriptomics of the model entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium anisopliae and M. acridum. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zheng P., Xia Y., Xiao G., Xiong C., Hu X., Zhang S., Zheng H., Huang Y., Zhou Y., Wang S., Zhao G. P., Liu X., St. Leger R. J., Wang C. (2011) Genome sequence of the insect pathogenic fungus Cordyceps militaris, a valued traditional Chinese medicine. Genome Biol. 12, R116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiao G., Ying S. H., Zheng P., Wang Z. L., Zhang S., Xie X. Q., Shang Y., St. Leger R. J., Zhao G. P., Wang C., Feng M. G. (2012) Genomic perspectives on the evolution of fungal entomopathogenicity in Beauveria bassiana. Sci. Rep. 2, 483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu X., Xiao G., Zheng P., Shang Y., Su Y., Zhang X., Liu X., Zhan S., St. Leger R. J., Wang C. (2014) Trajectory and genomic determinants of fungal-pathogen speciation and host adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 16796–16801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Faria M. R., Wraight S. P. (2007) Mycoinsecticides and mycoacaricides: a comprehensive list with worldwide coverage and international classification of formulation types. Biol. Control 43, 237–256 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang C., Feng M. G. (2014) Advances in fundamental and applied studies in China of fungal biocontrol agents for use against arthropod pests. Biol. Control 68, 129–135 [Google Scholar]

- 22. St. Leger R. J., Wang C. (2010) Genetic engineering of fungal biocontrol agents to achieve greater efficacy against insect pests. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 901–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boomsma J. J., Jensen A. B., Meyling N. V., Eilenberg J. (2014) Evolutionary interaction networks of insect pathogenic fungi. Annu Rev. Entomol. 59, 467–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Duan Z., Chen Y., Huang W., Shang Y., Chen P., Wang C. (2013) Linkage of autophagy to fungal development, lipid storage and virulence in Metarhizium robertsii. Autophagy 9, 538–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wanchoo A., Lewis M. W., Keyhani N. O. (2009) Lectin mapping reveals stage-specific display of surface carbohydrates in in vitro and haemolymph-derived cells of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Microbiology 155, 3121–3133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang S., Xia Y. X., Kim B., Keyhani N. O. (2011) Two hydrophobins are involved in fungal spore coat rodlet layer assembly and each play distinct roles in surface interactions, development and pathogenesis in the entomopathogenic fungus, Beauveria bassiana. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 811–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang C., Typas M. A., Butt T. M. (2002) Detection and characterisation of pr1 virulent gene deficiencies in the insect pathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 213, 251–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang C., Skrobek A., Butt T. M. (2004) Investigations on the destruxin production of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 85, 168–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang J. C., Xu H., Zhu Y., Liu Q. Q., Cai X. L. (2013) OsbZIP58, a basic leucine zipper transcription factor, regulates starch biosynthesis in rice endosperm. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3453–3466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) ClustalW and ClustalX version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang W., Shang Y., Chen P., Gao Q., Wang C. (2014) MrpacC regulates sporulation, insect cuticle penetration and immune evasion in Metarhizium robertsii. Environ. Microbiol. 10.1111/1462-2920.12451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Duan Z., Shang Y., Gao Q., Zheng P., Wang C. (2009) A phosphoketolase Mpk1 of bacterial origin is adaptively required for full virulence in the insect-pathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2351–2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gao Q., Shang Y., Huang W., Wang C. (2013) Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase contributes to triacylglycerol biosynthesis, lipid droplet formation, and host invasion in Metarhizium robertsii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 7646–7653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Selvaggini S., Munro C. A., Paschoud S., Sanglard D., Gow N. A. (2004) Independent regulation of chitin synthase and chitinase activity in Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology 150, 921–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yago J. I., Lin C. H., Chung K. R. (2011) The SLT2 mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated signalling pathway governs conidiation, morphogenesis, fungal virulence and production of toxin and melanin in the tangerine pathotype of Alternaria alternata. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 653–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang B., Kang Q., Lu Y., Bai L., Wang C. (2012) Unveiling the biosynthetic puzzle of destruxins in Metarhizium species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1287–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. St. Leger R. J., Bidochka M. J., Roberts D. W. (1994) Isoforms of the cuticle-degrading Pr1 proteinase and production of a metalloproteinase by Metarhizium anisopliae. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 313, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu D., Pava-Ripoll M., Li Z., Wang C. (2008) Insecticidal evaluation of Beauveria bassiana engineered to express a scorpion neurotoxin and a cuticle degrading protease. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 81, 515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen Y., Feng P., Shang Y., Xu Y.J., Wang C. (2014) Biosynthesis of non-melanin pigment by a divergent polyketide synthase in Metarhizium robertsii. Fungal Genet. Biol. 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Spode I., Maiwald D., Hollenberg C. P., Suckow M. (2002) ATF/CREB sites present in sub-telomeric regions of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomes are part of promoters and act as UAS/URS of highly conserved COS genes. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 407–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang C., Hu G., St. Leger R. J. (2005) Differential gene expression by Metarhizium anisopliae growing in root exudate and host (Manduca sexta) cuticle or hemolymph reveals mechanisms of physiological adaptation. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42, 704–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Emri T., Molnár Z., Szilágyi M., Pócsi I. (2008) Regulation of autolysis in Aspergillus nidulans. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 151, 211–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Orlean P. (1997) Biogenesis of yeast wall and surface components. Cold Spring Harb. Monograph Arch. 21, 229–362 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lagorce A., Le Berre-Anton V., Aguilar-Uscanga B., Martin-Yken H., Dagkessamanskaia A., François J. (2002) Involvement of GFA1, which encodes glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase, in the activation of the chitin synthesis pathway in response to cell-wall defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 1697–1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang C., St. Leger R. J. (2007) The MAD1 adhesin of Metarhizium anisopliae links adhesion with blastospore production and virulence to insects, and the MAD2 adhesin enables attachment to plants. Eukaryot. Cell 6, 808–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Conkright M. D., Guzmán E., Flechner L., Su A. I., Hogenesch J. B., Montminy M. (2003) Genome-wide analysis of CREB target genes reveals a core promoter requirement for cAMP responsiveness. Mol. Cell 11, 1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gabaldón T., Koonin E. V. (2013) Functional and evolutionary implications of gene orthology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 360–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zheng P., Xia Y., Zhang S., Wang C. (2013) Genetics of Cordyceps and related fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 2797–2804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ramana K. V., Kandi S., Bharatkumar V., Sharada C. V., Rao R., Mani R., Rao S. D. (2013) Invasive fungal infections: a comprehensive review. Am. J. Infect. Dis. Microbiol. 1, 64–69 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ragni E., Fontaine T., Gissi C., Latgè J. P., Popolo L. (2007) The Gas family of proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: characterization and evolutionary analysis. Yeast 24, 297–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alberti-Segui C., Morales A. J., Xing H., Kessler M. M., Willins D. A., Weinstock K. G., Cottarel G., Fechtel K., Rogers B. (2004) Identification of potential cell-surface proteins in Candida albicans and investigation of the role of a putative cell surface glycosidase in adhesion and virulence. Yeast 21, 285–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Calderon J., Zavrel M., Ragni E., Fonzi W. A., Rupp S., Popolo L. (2010) PHR1, a pH-regulated gene of Candida albicans encoding a glucan-remodelling enzyme, is required for adhesion and invasion. Microbiology 156, 2484–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cabib E., Farkas V., Kosík O., Blanco N., Arroyo J., McPhie P. (2008) Assembly of the yeast cell wall. Crh1p and Crh2p act as transglycosylases in vivo and in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29859–29872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. St. Leger R. J., Joshi L., Bidochka M. J., Roberts D. W. (1996) Construction of an improved mycoinsecticide overexpressing a toxic protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 6349–6354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen L., Zou G., Zhang L., de Vries R. P., Yan X., Zhang J., Liu R., Wang C., Qu Y., Zhou Z. (2014) The distinctive regulatory roles of PrtT in the cell metabolism of Penicillium oxalicum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 63, 42–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]