Abstract

Dissociation-induced apoptosis of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) hampers their large-scale culture. Herein we leveraged the mechanosensitivity of hESCs and employed, to our knowledge, a novel technique, acoustic tweezing cytometry (ATC), for subcellular mechanical stimulation of disassociated single hESCs to improve their survival. By acoustically actuating integrin-bound microbubbles (MBs) to live cells, ATC increased the survival rate and cloning efficiency of hESCs by threefold. A positive correlation was observed between the increased hESC survival rate and total accumulative displacement of integrin-anchored MBs during ATC stimulation. ATC may serve as a promising biocompatible tool to improve hESC culture.

Main Text

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) hold indefinite self-renewing capacity in vitro. However, their large-scale maintenance and expansion are significantly hindered by dissociation-induced apoptosis, leading to extremely low single-cell cloning efficiency (<1%). Although the discovery that inhibition of Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) can significantly improve survival of dissociated hESCs may offer a solution (1), long-term effects of treatments of hESCs with ROCK inhibitors are unclear, and such inhibitors have been associated with aneuploidy, which is implicated in cell transformation. In addition, because myosin II activity, a downstream effector of ROCK, is involved in formation of cleavage furrow and cytokinesis, long-term exposure to ROCK inhibitors can inhibit cell division to negatively impact hESC cloning efficiency (2,3). Consequently, passaging hESCs by mechanically cutting large colonies into small clumps is still a routine practice used in stem cell laboratories.

Recently, we and others have demonstrated that hESCs are intrinsically mechanosensitive and that their self-renewal and differentiation are influenced by biophysical signals including mechanical forces and matrix rigidity (4–6). Here we leveraged a newly developed technique, acoustic tweezing cytometry (ATC), to explore whether mechanobiology might be exploited for improving hESC culture. We specifically examined whether subcellular mechanical forces exerted by ATC might improve survival of disassociated single hESCs (7). In ATC, ultrasound pulses are utilized to acoustically excite functionalized lipid-encapsulated microbubbles (MBs) targeted to cell-surface integrin receptors to apply subcellular forces through MB-integrin-actin cytoskeleton linkage (Fig. 1 a) (7) and cell membrane (8).

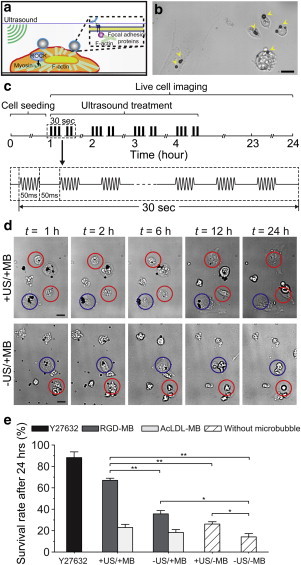

Figure 1.

(a) ATC stimulation by acoustic excitation of MBs attached to cells. (b) Bright-field image showing hESCs attached with MBs. Scale bar, 20 μm. (c) Illustration of ultrasound protocol. (d) Live cell imaging showing hESCs exposed to ATC. Rounded hESCs (red circles) with spread hESCs (blue circles). Scale bar, 10 μm. (e) Survival rate of hESCs exposed to ATC treatments with RGD-MBs, AcLDL-MBs, and without MB (n = 5, number of cells in each experiment > 200). Error bars, mean ± SE; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, Student’s t-test. To see this figure in color, go online.

For ATC stimulation of hESCs, disassociated single hESCs were first seeded on tissue culture plates at a density of 10,000 cells cm−2 for 1 h followed by 10-min incubation with MBs (3 × 107 mL−1) functionalized with Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptides (RGD-MBs) using avidin-biotin conjugation chemistry to allow specific integrin binding. Ultrasound pulses (center frequency 10 MHz, pulse duration 50 ms, pulse repetition frequency 10 Hz, acoustic pressure 0.08 MPa) were then applied to hESCs bound with RGD-MBs for 30 s every hour for 4 h, consecutively (Fig. 1, b and c, and see the Supporting Material).

Live cell imaging was performed using a synchronized high-speed camera to monitor dynamic changes of cell morphology and activities of MBs during and after ATC applications (see Methods in the Supporting Material; and see Fig. 1 d). MBs exhibited robust responses to ultrasound pulses, including displacements due to the acoustic radiation forces (9) acting on MBs (7) (see Movie S1). As expected, for negative controls without MBs and without ultrasound (US) treatments (−US/−MB), most hESCs upon cell seeding exhibited marked changes in cell morphology that included cell body contraction and membrane blebbing before undergoing apoptosis within 24 h after disassociation, resulting in a limited survival rate of 16.8 ± 3.1% (n = 5) (Fig. 1 e). Notably, for hESCs attached with RGD-MBs, ATC treatments elicited spreading of the originally rounded hESCs and their adherence to tissue culture plates. As a result, 67.0 ± 2.0% (n = 5) of such cells survived within 24 h after disassociation (+US/+MB; Fig. 1, d and e; Movie S2). hESCs that have already spread before ATC treatments also survived for at least 24 h regardless of the presence of MBs or US treatment (Fig. 1 d), suggesting that cell spreading and adhesion might be critical for promoting hESC survival. Interestingly, ultrasound application alone (+US/−MB) or the presence of RGD-MBs alone (−US/+MB) had marginal but significant effect in enhancing hESC survival, resulting in a survival rate of 28.6 ± 2.2% (n = 5) for hESCs without MBs but treated with ultrasound (+US/−MB) (Fig. 1 e), and 35.7 ± 3.0% (n = 5) for hESCs with RGD-MBs but without ultrasound treatment (−US/+MB; Fig. 1 e). These results suggest that binding of RGD-MBs may trigger adhesion signaling and promote hESC survival.

To further investigate the role of integrin-mediated adhesion in hESC survival, we conducted experiments to apply ATC treatments to hESCs conjugated with MBs coated with acetylated low-density lipoprotein (AcLDL; AcLDL-MBs), a ligand for transmembrane metabolic receptors that does not bind integrins. Under the same ATC treatments, the survival rate of hESCs with AcLDL-MBs was unchanged compared to cells without MBs (−US/−MB and +US/−MB; Fig. 1 e), even though AcLDL-MBs exhibited significantly greater displacements than RGD-MBs (data not shown). These data suggested that integrin-mediated adhesion was required for improved hESC survival by acoustic actuation of integrin-anchored RGD-MBs.

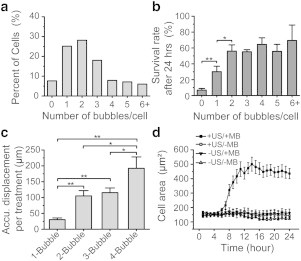

To ascertain details of acoustic actuation of integrin-anchored RGD-MBs on hESCs, we divided originally rounded single hESCs into different subgroups based on the initial number of RGD-MBs attached to each cell (Fig. 2 a). We examined hESC survival rate and the corresponding MB displacements for each subgroup. hESCs with two or more RGD-MBs per cell exhibited a significantly greater survival rate than cells with no or only one RGD-MB under ATC treatments (Fig. 2 b). The total accumulative RGD-MB displacement per cell for hESCs with two to four RGD-MBs was also significantly greater than that for hESCs with only one RGD-MB per cell (Fig. 2 c). It should be noted that the heightened total accumulative displacement of RGD-MBs was not only due to the greater number of RGD-MBs per cell, but also from the secondary acoustic radiation forces between MBs (9), which could efficiently displace MBs toward each other (Movie S3). For hESCs with three RGD-MBs per cell, the total accumulative MB displacement was similar to two-bubble cases (Fig. 2 c), because one of the three MBs often exhibited a minimal movement (Movie S4) with balance of forces in the presence of multiple MBs and mutual interactions among them. Four-MB cases could be considered as a combination of one-, two-, and/or three-MB cases with variations in the patterns of individual MB movements depending on their relative locations with each other on the cells (Fig. 2 c; Movie S5). In addition, initially rounded hESCs bound with RGD-MBs and treated with ATC stimulations (+US/+MB) initiated their spreading ∼5 h after cell seeding and became fully spread by 12 h (Fig. 2 d), significantly slower than conventional cell-spreading processes (10). Areas of hESCs without MBs (+US/−MB) or with MBs but without ultrasound treatments (−US/+MB) remained unchanged during the first 24 hours after cell seeding (Fig. 2 d), corresponding to low survival rates for these groups.

Figure 2.

(a) Distribution of MBs per cell (five independent experiments, n > 200 cells for each). (b) Survival rate of hESCs with different initial numbers of RGD-MBs/cell; n > 200 cells for each experiment, n > 20 cells for each subgroup with different number of MBs per cell. Error bars, mean ± SE; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, Student’s t-test. (c) Accumulative MB displacement per ATC treatment. Error bars, mean ± SE; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05, Student’s t-test. (d) Change of cell area for different subgroups.

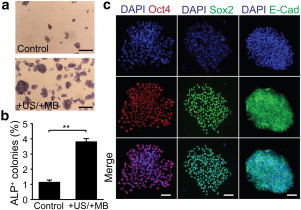

To evaluate possible long-term effects of ATC treatment, we conducted an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) assay to determine hESC cloning efficiency. Consistent with improved initial survival rate, cloning efficiency of ATC-treated hESCs increased approximately threefold compared to untreated −US/−MB controls (Fig. 3, a and b), suggesting that the effect of ATC was mainly the improvement of initial survival of disassociated hESCs rather than cell proliferation or migration (11,12). ATC treatments did not adversely impact hESC stemness marker expression, as shown by positive immunostaining of pluripotency markers Oct4, Sox2, and E-cadherin 7 days after ATC treatments (Fig. 3 c).

Figure 3.

(a) ALP assay for dissociated hESCs with or without ATC treatments as indicated. Scale bar, 1 mm. (b) Relative ratio of ALP+ colonies to the number of hESCs initially seeded. (c) Immunostaining with anti-Oct4, anti-Sox2, and anti-E-cadherin antibodies for hESC colonies 7 days after ATC treatments. Scale bar, 100 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Collectively, our data indicate that ATC stimulations improve the clonogenicity of disassociated hESCs by increasing their initial survival rate. While the molecular mechanism underlying such mechanosensitive behavior of hESCs requires further study, our results suggest that integrin-mediated adhesion formation and strengthening by ATC stimulations may facilitate spreading of disassociated hESCs, which in turn rescues the cells from hyperactivated actomyosin activities triggering downstream caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling pathways.

Compared to established methods for applying subcellular forces using solid microbeads (i.e., optical and magnetic tweezers), ATC utilizes MBs that do not exhibit cellular internalization and can be easily removed from hESCs without leaving behind exogenous materials, providing a promising biocompatible platform for large-scale hESC culture.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by the National Science Foundation (grants No. CMMI 1129611 and No. CBET 1149401), the National Institutes of Health (grants No. R21 HL114011 and No. R21 EB017078), and the American Heart Association (grant No. 12SDG12180025).

Footnotes

Di Chen and Yubing Sun contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Cheri X. Deng, Email: cxdeng@umich.edu.

Jianping Fu, Email: jpfu@umich.edu.

Supporting Material

First 3 s, 500 frame/s. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Scale bar, 10 μm.

First 3 s, 500 frame/s. Scale bar, 10 μm.

First 3 s, 500 frame/s. Scale bar, 10 μm.

First 3 s, 500 frame/s. Scale bar, 10 μm.

References

- 1.Watanabe K., Ueno M., Sasai Y. A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:681–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen G., Hou Z., Thomson J.A. Actin-myosin contractility is responsible for the reduced viability of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohgushi M., Matsumura M., Sasai Y. Molecular pathway and cell state responsible for dissociation-induced apoptosis in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:225–239. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun Y., Villa-Diaz L.G., Fu J. Mechanics regulates fate decisions of human embryonic stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keung A.J., Asuri P., Schaffer D.V. Soft microenvironments promote the early neurogenic differentiation but not self-renewal of human pluripotent stem cells. Integr. Biol. (Camb) 2012;4:1049–1058. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20083j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Y., Yong K.M., Fu J. Hippo/YAP-mediated rigidity-dependent motor neuron differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nmat3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan Z., Sun Y., Fu J. Acoustic tweezing cytometry for live-cell subcellular modulation of intracellular cytoskeleton contractility. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2176. doi: 10.1038/srep02176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heureaux J., Chen D., Liu A.P. Activation of a bacterial mechanosensitive channel in mammalian cells by cytoskeletal stress. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2014;7:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12195-014-0337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayton P.A., Morgan K.E., Ferrara K.W. A preliminary evaluation of the effects of primary and secondary radiation forces on acoustic contrast agents. IEEE Trans. 1997;44:1264–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bardsley W.G., Aplin J.D. Kinetic analysis of cell spreading. I. Theory and modeling of curves. J. Cell Sci. 1983;61:365–373. doi: 10.1242/jcs.61.1.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbaric I., Biga V., Andrews P.W. Time-lapse analysis of human embryonic stem cells reveals multiple bottlenecks restricting colony formation and their relief upon culture adaptation. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:142–155. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L., Wang B.H., Wang L. Individual cell movement, asymmetric colony expansion, rho-associated kinase, and E-cadherin impact the clonogenicity of human embryonic stem cells. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2442–2451. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

First 3 s, 500 frame/s. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Scale bar, 10 μm.

First 3 s, 500 frame/s. Scale bar, 10 μm.

First 3 s, 500 frame/s. Scale bar, 10 μm.

First 3 s, 500 frame/s. Scale bar, 10 μm.