Abstract

The bacterial outer membrane comprises two main classes of components, lipids and membrane proteins. These nonsoluble compounds are conveyed across the aqueous periplasm along specific molecular transport routes: the lipid lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is shuttled by the Lpt system, whereas outer membrane proteins (Omps) are transported by chaperones, including the periplasmic Skp. In this study, we revisit the specificity of the chaperone-lipid interaction of Skp and LPS. High-resolution NMR spectroscopy measurements indicate that LPS interacts with Skp nonspecifically, accompanied by destabilization of the Skp trimer and similar to denaturation by the nonnatural detergent lauryldimethylamine-N-oxide (LDAO). Bioinformatic analysis of amino acid conservation, structural analysis of LPS-binding proteins, and MD simulations further confirm the absence of a specific LPS binding site on Skp, making a biological relevance of the interaction unlikely. Instead, our analysis reveals a highly conserved salt-bridge network, which likely has a role for Skp function.

Introduction

The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria includes lipids and integral membrane proteins as the two main component classes. For these insoluble molecules, specific molecular biogenesis systems are responsible for transport and assembly from the cytosolic point of synthesis to their final location. The lipid lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a key component of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane, with high relevance for the structural integrity and chemical protection of bacteria (1). LPS contains the hydrophobic moiety lipid A that is covalently attached to a polysaccharide and that elicits strong immune responses in mammalians (2,3). LPS is transported to the cell surface by the lipopolysaccharide transport (Lpt) system, which consists of seven essential proteins (1).

The biogenesis machinery for β-barrel outer membrane proteins (Omps) comprises multiple chaperones (4,5), including the cytosolic proteins trigger factor, SecB, and SecA (6–8); the SecYEG-translocon in the bacterial inner membrane (9); and the periplasmic proteins Skp and SurA, for transport across the periplasmic space toward the Bam-complex (β-barrel assembly machinery) (4,5,10). Whereas many chaperones in all kingdoms of life fulfill their tasks including protein disaggregation and folding in an ATP-dependent manner (11–14), the periplasmic chaperones pursue transport and release of aggregation-prone membrane proteins independent of ATP (15,16).

The periplasmic chaperone Skp was initially identified as a component of the cytoplasm (17,18), the outer membrane (19), or located on the cell surface (20), and was found to be associated with DNA (17,18), ribosomes (19), and LPS (20). Subsequently, the DNA and ribosome affinities could be attributed to nonspecific electrostatic interactions, arising from the basic nature of Skp (20), and the main functional role of Skp as a periplasmic Omp-folding factor was established (21,22). Skp is a homotrimeric protein exhibiting a jellyfish-like structure, and featuring a central cavity confined by helical coiled-coils (23,24). Skp interacts with a wide diversity of unfolded Omps during their periplasmic transport (25,26). Typical chaperone-Omp dissociation constants are in the nanomolar range (27), arising by avidity from multiple transient local interactions (28). These short-lived chaperone-Omp contacts are based on a combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions (29,30). Positive charges cluster mainly at the tips of the cavity-forming helices, favoring Skp-dependent Omp insertion into negatively charged membranes in vitro (30,31).

Three lines of evidence have led to a proposed specific effect of LPS on Skp function. First, the skp gene maps in a gene cluster involved in lipid A biosynthesis, pointing toward a possible functional correlation of the two molecules (18,32,33). Second, biochemical refolding experiments have suggested the requirement of LPS for an efficient assembly of trimeric PhoE and monomeric OmpA in the outer membrane (34,35). Third, a structural comparison of the known LPS binding sites on the β-barrel outer membrane proteins FhuA and OmpT showed certain similarities (36,37), leading to a proposition of residues E29, K77, Q79, R87, and R88 as a conserved LPS binding site on Skp (23). Two possible roles of the Skp-LPS interaction were suggested: either LPS might be involved in an intermediate state of Omp folding, where it forms a complex with Skp-Omp to initiate subsequent membrane insertion (30,33,38), or Skp might have a functional role during LPS biogenesis, by transporting LPS molecules toward the outer membrane (39).

In this study, we use high-resolution NMR spectroscopy to investigate the nature of the LPS-Skp interaction in a residue-specific manner. We characterize the effects of the amphiphilic LPS on Skp structure and compare it with the nonnatural detergent lauryldimethylamine-N-oxide (LDAO). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are employed to characterize the specificity of the Skp-LPS interactions in silico. Furthermore, we perform an extended sequence alignment to identify the most-conserved residues within Skp.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification of Skp

Skp containing an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag and lacking its signal sequence was expressed and purified as described previously (28).

Lipid titrations

Rough-type LPS from Escherichia coli (E. coli) EH100 (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in NMR buffer (25 mM MES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 6.5) at a concentration of 20 mg/ml, corresponding to 3.6 mM (40,41). To solubilize the LPS-powder, five cycles of vortexing, warming to 80°C for 10 min, and subsequent cooling on ice for 15 min were done, yielding a slightly hazy solution, which was directly used for the NMR-titrations. LDAO (Anatrace, Maumee, OH) was dissolved in NMR-buffer as a 20% (w/v) stock solution.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR measurements were performed on a Bruker AscendII 700 MHz spectrometer and a Bruker Avance 800 MHz spectrometer equipped with cryogenically cooled triple-resonance probes. For all titration measurements, two-dimensional (2D) [15N,1H]-TROSY spectra were recorded (42). All spectra were recorded with 1024 and 300 complex points in the direct and indirect dimensions, respectively. The titration spectra at 13.6 and 18.2 mM LPS concentration were recorded with 16 and 92 scans per increment, respectively, whereas all other spectra were accumulated with eight scans per increment. For quantitative analysis of signal intensities, the amplitudes were corrected by differences in 1H-90° pulse-length, the number of scans, and the dilution factor (43). For the characterization of Skp in the presence of high LPS concentration, 15N-filtered bipolar pulse pairs-longitudinal eddy current delay (LED) diffusion was measured (44). All spectra were acquired at 37°C. NMR data were processed using PROSA (45), analyzed with CARA (46) and Topspin 3.2 (Bruker Biospin, Fällanden, Switzerland).

The residue-specific interaction analysis of apo Skp was based on published assignments (Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank: 19407) (28). The chemical shift changes for the amide moiety were calculated as follows.

Chemical shift changes upon LDAO titration were fitted by nonlinear regression analysis as follows.

The population equilibrium of LDAO-induced Skp unfolding was calculated from ratios of NMR signal intensities in folded and unfolded Skp. The average signal-intensities of 133 nonoverlapping peaks of the folded and 130 nonoverlapping peaks of the unfolded species were determined at each titration step. Error bars were calculated from the spectral noise.

Microscale thermophoresis

Skp was labeled on the amino-terminus using the NHS-ester Dylight488 (ThermoPierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The labeling ratio of 0.2 dye:1 Skp monomer was confirmed by ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy. Samples for microscale thermophoresis were prepared with a constant Skp concentration of 466 nM labeled Skp (99nM DyLight488) and varying the LPS concentration from 2 to 1000 nM. Microscale thermophoresis data were acquired using a Nanotemper Monolith (München, Germany) NT.115 instrument with blue-channel detection. The LED power was 100%, laser power was 60%, laser-on time was 30s, and laser-off time 5 s.

Sequence conservation analysis

The ConSurf (Tel Aviv University, Israel) server (47,48) was used with the E. coli Skp crystal structure (PDB ID 1SP2, chain A (24)) as an input for a CSI-Blast homology search (49,50) against the UNIREF-90 database (51) with standard parameters. This homology search yielded 55 nonredundant Skp sequences (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). These sequences were used for analysis on the ConSurf server using Bayesian methods for the calculation of amino acid conversation scores (47,48).

Molecular dynamics simulations

A crystal structure of Skp (PDB ID 1SG2 (24)) was used as the initial configuration for all simulations. The missing tips of partially unresolved subunits were modeled via superimposition of the resolved chains. Simulations of Skp in the presence of a major hexa-acylated 1-pyrophosphate form of lipid A and with the addition of two KDO-sugars (termed lipid-A-KDO) from E. coli (52) were performed with the Nanoscale Molecular Dynamics program package v2.7b2 (53) using the CHARMM27 force field parameter set incorporating the CMAP potential corrections (54,55). The lipid A parameters were based on a previously reported simulation study (56). Analysis of trajectories was performed using the GROMACS simulation package version 4.6.5 (57–59), VMD (60), and locally written code. The trajectories, originally in dcd format, were made GROMACS-readable using catdcd. Initially, three lipid molecules per Skp trimer were positioned with a minimum-distance of ≤5 Å between the lipid phosphate groups and the charged side-chain atoms originally proposed as part of an LPS binding site, and with the acyl tails oriented away from the protein. A protein-restrained simulation was then run during which the lipid A molecules spontaneously adsorbed to the protein surface. Subsequently, 500 ns of protein-unrestrained simulation sampling were generated for trimeric Skp, split into five simulation replicas to improve conformational sampling. The cutoff distance for the quantification of salt bridge formation within Skp was set to 4.5 Å.

Results

Denaturation of the Skp trimer by LDAO

As a reference point for the LPS interaction, we characterize the interaction of the nonnatural detergent LDAO with Skp. A stepwise titration of LDAO to [U-2H,15N]-Skp was performed and the effects on the structure were monitored by 2D NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 1). In buffer solution, Skp populates a two-state chemical equilibrium between a trimeric and a monomeric, unfolded form, with a population of ∼5% monomers at 37°C. The identification of the lowly populated monomeric species, devoid of secondary structure, is based on the analysis of 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY NMR spectra, which feature a second complete set of resonances for the tentacle as well as the basal multimerization domain besides the trimeric Skp, with chemical shifts in the random-coil region (Fig. 1 A). The two conformations are in slow exchange on the NMR timescale, i.e., with kinetic exchange rate constants <1 s−1. Importantly, the monomeric form is flexibly unfolded and vanishes below the detection sensitivity upon binding of an outer membrane protein substrate (28). Upon titration of LDAO to [U-2H,15N]-Skp, the equilibrium between the two species is shifted toward monomeric Skp, with an unfolding transition midpoint at 60 ± 10 mM LDAO (Fig. 1 B).

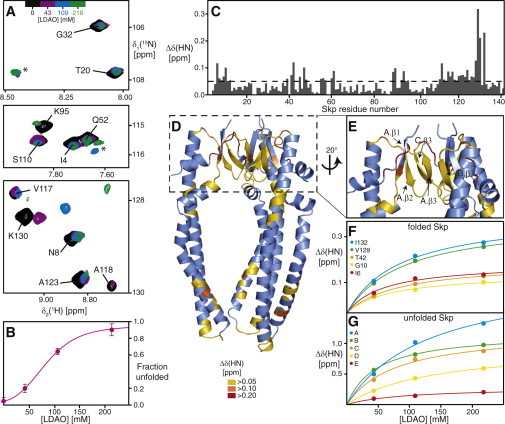

Figure 1.

Denaturation of Skp by the detergent LDAO. (A) Overlay of 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY NMR fingerprint spectra of [U-15N,2H]-Skp (black, 190 μM trimer concentration) in NMR buffer, with increasing LDAO-concentrations as indicated. Sequence-specific resonance assignments of folded Skp are indicated. Resonances of unfolded Skp are marked by asterisks. (B) Population equilibrium of LDAO-induced Skp unfolding. Experimental data points are shown as circles, the magenta line shows a nonlinear least-squares fit of the data to a two-state model of chemical unfolding (61). (C) Combined amide chemical shift differences δΔ(HN) of folded Skp in 218 mM LDAO relative to 0 mM LDAO. The dashed line indicates the significance level of 0.05 ppm. (D and E) Skp crystal structure (blue, PDB 1SG2 (24)) with the significant chemical shift changes of the amide moiety at 218 mM LDAO marked yellow-orange-red, as indicated. (F and G) Backbone amide chemical shift perturbations for selected residues of (F) folded Skp and (G) unfolded Skp upon titration with LDAO. Experimental data points are shown as circles, the lines represent a simultaneous nonlinear least-squares fit to all data, using a bimolecular equilibrium binding model. To see this figure in color, go online.

In addition to shifting the folding equilibrium, LDAO molecules bind to both the folded and unfolded forms of Skp, as evidenced by chemical shift changes to a subset of resonances of each species. In the folded state, these are residues located in two main interaction sites: one LDAO interaction site comprises strands β2 and β3 as well as the linker to helix α4. These elements are all part of the basal trimerization interface. The second LDAO interaction site is located in the lower parts of helices α2 and α3 toward the tip, and in the kink in helix α3 (Fig. 1, C–E). Thereby, the concentration-dependence of the chemical shift changes follow a two-state binding model with a dissociation constant of KD = 77 ± 12 mM (Fig. 1 F; Table S1). Binding of LDAO is also observed for a subset of the residues of unfolded Skp, for which currently no sequence-specific resonance assignments are available, with a divergence of local dissociation constants in the range of 47 to 138 mM (Fig. 1 G; Table S2). Overall, the detergent LDAO thus destabilizes and unfolds trimeric Skp, both by interfering with hydrophobic regions in the trimer interface, as well as by stabilizing the unfolded Skp monomer polypeptide. These effects lead to a full disassembly of Skp into its monomeric subunits at LDAO concentrations above 250 mM.

Skp is denatured by LPS and interacts with LPS-aggregates

For the characterization of the LPS-Skp interaction, a stepwise titration of LPS to [U-2H,15N]-Skp was performed and the effects on the structure were monitored by 2D NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 2). The addition of the lipid LPS shifted the monomer-trimer equilibrium toward the unfolded monomer species, similar to the LDAO denaturation. Analysis of the signal intensity of the C-terminal residue K141 in folded and unfolded Skp in 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY spectra showed that trimeric Skp is stable up to a concentration of 0.7 mM LPS (Fig. 2 B). The midpoint of the unfolding transition is at ∼1.7 mM LPS, indicating a stronger denaturing effect of LPS compared with LDAO (Fig. 2 C). Importantly, while causing this denaturation of trimeric Skp, LPS did not lead to any significant chemical shift changes on Skp, consistent with the absence of a specific binding site. In particular, residues E29, K77, Q79, and R88, which are part of a previously proposed LPS binding site, do not feature LPS-dependent chemical shifts (Fig. 2 D). Rather, the addition of LPS caused a general decrease of the Skp signal intensities (Fig. 3 A). This decrease is significantly enhanced at increasing LPS concentrations, up to a signal loss of ∼90% at 1.8 mM LPS (Fig. 3 B). The magnitude of this line-broadening effect is uniform over the sequence of Skp, in agreement with a nonspecific interaction (Fig. S2).

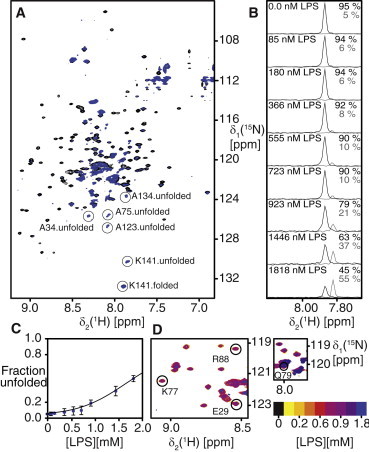

Figure 2.

Denaturation of Skp by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). (A) Overlay of 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY NMR fingerprint spectra of [U-15N,2H]-Skp (200 μM trimer concentration) in NMR buffer in absence of LPS (black) and in the presence of 1.8 mM LPS (blue). The C-terminal residue K141 in the folded as well as unfolded state, and additional alanine residues belonging to the unfolded species are encircled. (B) δ1[15N]-1D cross-sections of 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY NMR spectra at variable LPS concentration, taken at the positions of residue K141. The relative signal intensities of K141 in folded and unfolded Skp are indicated in black and gray, respectively. (C) Population of unfolded Skp as a function of the LPS concentration. The circles are experimental data points, the line is a nonlinear fit to the data. (D) Two spectral regions from 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY NMR spectra of [U-15N,2H]-Skp during an LPS titration (yellow-red-blue, as indicated). The amide resonances of E29, K77, Q79, and R88 are indicated. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 3.

Unspecific interaction of Skp with LPS-preaggregates. (A) δ1[15N]-1D cross-sections from 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY spectra of a titration of [U-15N,2H]-Skp (200 μM trimer concentration) in NMR buffer with variable LPS concentration, as indicated by the color gradient. The red and blue dashed lines indicate the integration limits for folded Skp and all protein signals, respectively. (B) NMR signal intensity of the spectra in A as a function of the LPS concentration. Values for the complete spectrum are shown in blue and for the β-sheet region in red. (C) Measurement of effective molecular diffusion constants of Skp in the presence of 1.8 mM LPS by a 15N-filtered diffusion bipolar pulse pairs-LED NMR experiment (44). The blue circles are measurements of the signal intensity as a function of the field gradient strength. The black line represents the linear fit to the measured data. To see this figure in color, go online.

In aqueous solution at 37°C, LPS forms large preaggregate oligomers of ∼60 nm size, with a critical aggregation concentration of 8.1 ± 0.3 nM (62). The most likely explanation for the decrease in NMR signal intensity is thus a restriction of molecular motion, as it would be caused by transient interactions of Skp with the LPS-preaggregate oligomers (63). This explanation is additionally evidenced by measurements of the Skp self-diffusion coefficient at 1.8 mM LPS (Fig. 3 C). Whereas free Skp with a molecular weight of 54 kDa has a self-diffusion coefficient of D = 6.0·10−11 m2s−1, the self-diffusion coefficient of the molecule in presence of LPS is decreased by a factor of 2.5 to D = 2.4·10−11 m2s−1 (Fig. 3 C). Additionally, to assess if Skp might bind to monomeric LPS at nanomolar concentrations we used microscale thermophoresis, which showed that under our experimental conditions no significant interaction between Skp and monomeric LPS occurs (Fig. S3). Overall, the structural effect of LPS is thus a nonspecific denaturation of the trimeric chaperone Skp.

Conservation of amino acid residues in Skp

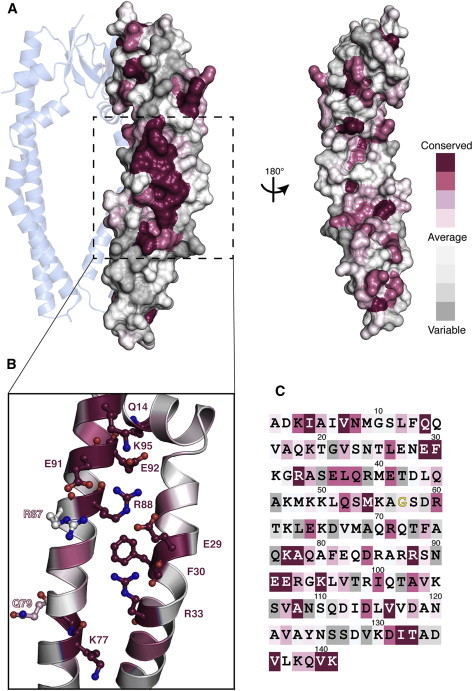

The initial proposition of residues E29, K77, Q79, R87, and R88 as an LPS binding site was supported by considerations of evolutionary conservation of these residues in Skp (23). A specific and biologically relevant LPS binding site would be expected to be highly conserved within the Skp family of proteins. We revisited this scenario by a sequence alignment of 55 nonredundant Skp-sequences, comprising the entire currently annotated Skp family. The analysis shows a distinct region with high conservation at the interhelix interface (Fig. 4 A). However, this region overlaps only partially with the previously suggested LPS binding site, of which only residues E29, K77, and R88, but not Q79 and R87 are highly conserved (Fig. 4 B). Rather, the region of highly conserved residues comprises further residues. It is centered around invariant F30 and consists of the pairs of oppositely charged residues R88–E29, R88–E92, and Q14–E92. These residues are located on the adjacent α-helices of the Skp coiled-coil arm, forming a salt bridge network. The conserved region further comprises residues V136, V140, and K141, which are located in a patch on the C-terminal helix α4 and whose side chains all point toward helix α3. Presumably, these residues form a functional side-chain network important for stabilization of the helical coiled-coils of Skp.

Figure 4.

Conservation analysis of the Skp family of proteins. (A) Surface representation of one Skp protomer displaying the degree of evolutionary conservation in a color gradient from dark purple-white-gray, as indicated (47,48). The protomer is shown as part of the Skp trimer (PDB 1SG2 (24)), as well as rotated by 180°. (B) Close-up of Skp in ribbon representation with a highly conserved arrangement of amino acid residues shown as ball and sticks. (C) Amino acid sequence of E. coli Skp with the same coloring. For G57 (yellow), no conservation score could be calculated. The complete alignment is shown in Fig. S1. To see this figure in color, go online.

In addition to the region of conserved residues at the helix-helix interface, a set of seven highly conserved residues L3, I4, V6, A108, V116, I132, and T133 is found in the basal unit of Skp. These residues are directly or indirectly involved in interstrand stabilization of β1 and β2. In contrast, the most variable region of Skp is located in the lower part of the helices α2 and α3 and in the tip of the arms. Their high variability suggests these residues to be of little importance for substrate interaction, in excellent agreement with our previous experimental observations that the helical tips are not in contact with typical substrates (28).

Molecular dynamics simulations

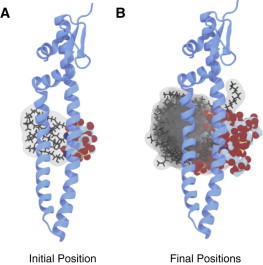

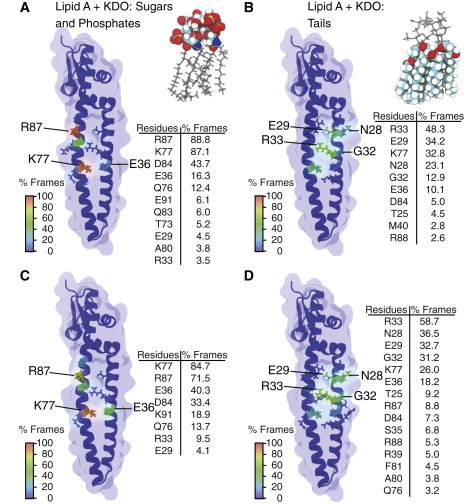

MD simulations of hypothetical Skp-LPS complexes at atomic resolution were performed as additional assessment. For this we used lipid A and 2 attached KDO sugars (lipid-A-KDO) as well as lipid A only. Starting from a configuration of lipid-A-KDO docked to the proposed binding site of trimeric Skp, five independent simulations of 100 ns length provided 15 independent observations of the interaction (Fig. 5). The interaction specificity was assessed by the occurrence of intermolecular contacts within ≤3.5 Å of lipid, for either the first or the last 20 ns of each 100 ns trajectory, averaged over all 15 Skp monomers (Fig. 6).

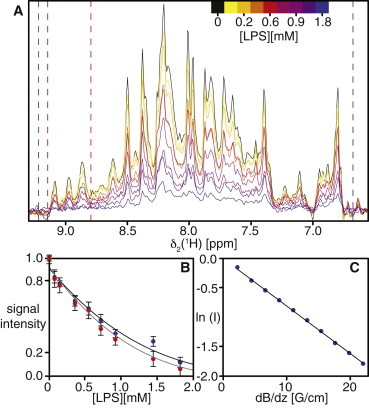

Figure 5.

Conformations of Skp–lipid-A-KDO ensembles. (A) Initial configuration of the Skp–lipid-A-KDO complex after its adsorption to the binding site. This is the initial configuration for the unrestrained MD simulations. (B) Overlaid final positions of 15 lipid molecules relative to Skp. The structures of Skp were aligned by a least-square fit of the proposed binding site residues. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 6.

Mean intermolecular contacts in five independent MD simulations of Skp and lipid-A-KDO. (A and B) The first 20 ns of the trajectories and (C and D) the last 20 ns of the trajectories. The number of frames recording contacts between nonhydrogen atoms of lipid A and Skp residues is shown. Contacts involving the lipid A sugars, KDO sugars, and phosphates are shown in (A) and (C), and the contacts involving lipid tails are shown in (B) and (D). A contact was recorded if at least one atom pair had an interatomic distance of <3.5 Å. To see this figure in color, go online.

In general, the contacts between lipid-A-KDO and the proposed binding site on Skp mirrored those of the lipid A simulations (Fig. 6 and Table S3). The specificity of the interaction between Skp and lipid-A-KDO decreased over the course of the simulations, with residues in the first 20 ns of the simulations, R87 (88.8%), K77 (87.1%), and D84 (43.7%), displaying less time in contact with lipid-A-KDO in the last 20 ns, 71.5%, 84.7%, and 33.4% of the time, respectively. In a few cases, residues from Skp were observed to be in contact with lipid-A-KDO more often at the end of the simulations, E36 (40.3%) and E91 (18.9%) than at the start, 16.3% and 6.1%, respectively. In a similar fashion to the lipid A simulations, the acyl tails also showed substantial variation over the course of the trajectories. During the initial 20 ns, the tails were in proximity with nine residues for ≥2.5% of the time, whereas in the last 20 ns, the tails were in contact with a total of 15 residues. These changes in the distribution of contacts between the start and end of the simulations were the result of a positional rearrangement of the lipid-A-KDO molecules relative to Skp (Fig. 5). During the initial 20 ns, the tails were in proximity with 10 residues for ≥2.5% of the time, whereas in the last 20 ns, the tails were in contact with a total of 15 residues. All these contacts were nonspecific and made only with hydrophilic residues, as a result of the absence of solvent-exposed hydrophobic amino acids near to the proposed LPS binding site. Indeed, despite the homogeneously assembled initial state, in several cases the lipid molecules completely dissociated from the proposed LPS-binding site during the 100 ns simulations (Fig. 5).

The stability of the salt bridge network formed by conserved residues E29, R88, and E92 upon contact with lipid A was compared with an equivalent simulation of apoSkp. In the absence of LPS, R88 is involved in a salt bridge in >95% of the trajectories. These are formed with E29, E91 and E92 in 88%, 30%, and 79% of the trajectories, respectively. In the presence of LPS, these values changed only insignificantly. The salt bridge between R88 and E29 remained the most persistent and was present in 89% of the simulation time. The salt bridges formed between R88 and either E91 or E92 were present in 34% and 72%, respectively. The salt bridge network is largely unaffected by the docked lipid molecules and its stability is thus not dependent on the presence of LPS.

Finally, the stability of the Skp-LPS interaction was assessed by measuring the buried, or solvent excluded, surface area of LPS. The KDO sugars in isolation made few contacts with the bound subunit, with no residue in contact for >43% (R87) of the time. Interestingly, the sugars were able to make contact with adjacent Skp subunits forming a stable crosslink, inhibiting substantial rearrangements during the timescale of the simulations. The mean buried surface area between the polar head group of lipid-A-KDO and Skp subunit was 3.3 nm2. This represents an increase over the lipid A simulations (∼2.4 nm2) and can be directly attributed to interactions between the KDO sugars and the adjacent Skp subunits, which adds ∼1.3 nm2 to the buried area. Although the additional KDO sugars increased the total buried area, this represented only ∼16% of the surface area of the lipid-A-KDO polar head group, lower than the 20% observed in the lipid A simulations. The buried surface area between the fatty acid tails and the Skp subunit was 7.3 nm2. We compare these values with published data from a known high-affinity LPS binder, the MD-2 domain of TLR4 (56). In equivalent simulations of that complex with lipid A, the mean buried surface area was ∼5.4 nm2 for the polar headgroup and ∼25.1 nm2 for the acyl tails, corresponding, respectively, to burial of ∼40% versus ∼80% of the total surface area of lipid A. Thereby, the association of lipid A with the hydrophobic MD-2 cavity involves substantial burial of the acyl tails from solvent, similar to a membrane environment. Nonpolar residues are absent at the proposed conserved site in Skp and the limited burial of LPS is inconsistent with a specific binding site in Skp hinge region.

Discussion

The trimeric chaperone Skp is destabilized and denatured into monomeric subunits by either of the amphiphilic molecules LPS and LDAO. Thereby, the facile denaturation of Skp by LDAO can readily be explained by the small size of the hydrophobic core within the Skp trimerization domain, which exhibits only ∼20 Å of the 80 Å full-length of the protein (23,24). It is accompanied by interactions of LDAO with both states of Skp. The interaction with folded Skp has a dissociation constant of 77 mM and is site-preferential, as the residues most strongly affected are located in a cluster in the basal head region of folded Skp at the trimerization interface, linking the interaction to the simultaneously occurring trimer destabilization. LDAO dissociation constants for unfolded Skp vary in the range 47 to 138 mM, and these local affinity modulations are likely caused by variations of the amino acid sequence, leading to LDAO interactions with variable ionic and hydrophobic character.

The interaction with LPS preaggregates results in a similar, nonspecific denaturation of Skp, in agreement with previous observations (20). The interaction is accompanied by a decrease of the effective, ensemble-averaged lateral diffusion constant by a factor of 2.5, corresponding in first order to an increase in effective molecular weight by the same factor. This increase readily explains the signal loss upon LPS interaction, rendering only the most flexible residues in the random-coil region observable at high LPS concentrations. Compared with the biophysically determined hydrophobic radii of the LPS preaggregates in this concentration range (62,64), this observation indicates that Skp is not stably bound to LPS, but in a dynamic equilibrium between an LPS-bound and an unbound form, promoted by the positive overall charge of the Skp. MD simulations of Skp in complex with monomeric LPS provide no indications for a specific or stable binding. Importantly, the denaturating effect of LPS on Skp, or the incorporation of LPS into the lipid bilayer may well result in a modulation of the folding kinetics, as well as folding yields of Skp-bound outer membrane protein substrates (33,65). The denaturing effect of LPS on Skp may partly contribute to a modulation of the folding kinetics, but only if the LPS concentration is sufficiently high (33,65). At low LPS concentrations, Skp facilitates Omp folding into negatively charged membranes mainly by electrostatic effects and not by a specific interaction (30,31).

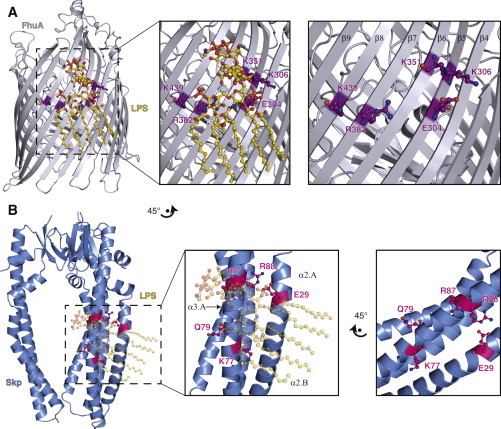

In contrast to the earlier alignment on a subset of Skp sequences (23), we observe only a partial evolutionary conservation of a previously proposed LPS binding site, where residues E29, K77, and R88, but not Q79 and R87, are highly conserved within the Skp family. The absence of a specific LPS binding motif in this region is further evidenced by a comparison of Skp with known protein crystal structures with bound LPS. These are the β-barrel outer membrane proteins FhuA (36), and OmpT (37), the Toll-like receptor (66), the LPS binding protein (67), and antibodies raised against LPS (68). All these proteins show exclusively β-strand secondary structure at the LPS binding site. Also the known structures of LPS biogenesis proteins, LptA (69), LptC (70), LptD (71,72), and LptE (71–73), exhibit high β-content and the LPS binding sites derived from cross-linking experiments are located on the inside of the β-jellyroll structures in LptA and LptC (74). Importantly, in all these structures the LPS binding sites are located either on the surface of an extended β-sheet, if LPS is bound when integrated in the outer membrane (36,75), or it is extended into a β-pocket for LPS binding in aqueous solution (66–68,74). In stark contrast, the presumed LPS binding site on Skp would be formed by two α-helices, leaving the outside of the LPS molecule exposed to the aqueous environment in an unusual and thermodynamically unfavorable arrangement (Fig. 7). Altogether, these evolutionary and structural considerations combined with the experimental absence of a specific interaction in an NMR titration make the scenario of a specific and biologically relevant LPS-interaction of Skp unlikely.

Figure 7.

Structural comparison of FhuA-LPS with Skp. (A) Ribbon representation of the FhuA crystal structure (silver) in complex with LPS (gold; PDB 2FCP (36)). Residues E304, K306, K351, R382, and K439, which are part of the FhuA-LPS contact surface, are highlighted in purple. In the right panel, LPS is omitted for clarity to show the structural arrangement of these side chains. (B) Hypothetic structural model of Skp-LPS based on a spatial alignment of the FhuA binding site with conserved Skp residues (23). Ribbon representation of the Skp crystal structure (blue, PDB 1SG2 (24)) with residues E29, K77, Q79, R87, and R88 highlighted in magenta on one Skp-protomer. A zoom is shown in the middle panel. The right panel shows the hypothetic LPS-interaction site rotated by 45°, to be in the same spatial orientation as in FhuA in (A). To see this figure in color, go online.

Rather, the set of conserved amino acid residues form an interhelical salt bridge network between the coiled-coil arms of Skp. Coiled-coils generally have a high degree of intrinsic disorder in need of stabilization by helix-helix interactions (76,77). The sequence alignment highlights the importance of the interhelix stabilization centered around residue F30, further strengthening our earlier observations of a pivot element around this residue, as well as the observed stabilization of helix α3.2 upon substrate binding (28). Whereas a high importance of this side-chain network for Skp function is suggested by its conservation as well as by the experimental evidence of rigidification upon substrate binding, its exact functional role remains elusive. For example, this stabilization may present a lock mechanism upon substrate binding, or a control mechanism for the arm dynamics.

In conclusion, the interaction of LPS with Skp is of nonspecific nature and has no biological significance, considering additionally the fact that free LPS is present in the periplasm only at very low concentrations of ∼0.1 fM (44). The previously proposed role of Skp in LPS biosynthesis based on the close genetic proximity of the skp gene to lipid-A–related genes (18,78) can well be rationalized by the functional role of Skp in LptD biogenesis (79), a β-barrel membrane protein that shuttles LPS molecules from the periplasm to the outer leaflet of the outer membrane (1,80).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Timothy Sharpe and the biophysics core facility of the Biozentrum Basel for the microscale thermophoresis measurements.

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant PP00P3_128419) and the European Research Council (FP7 contract MOMP 281764) to S.H. and by a personal fellowship from the Werner-Siemens Foundation to M.C.

Contributor Information

Björn M. Burmann, Email: bjoern.burmann@unibas.ch.

Sebastian Hiller, Email: sebastian.hiller@unibas.ch.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Ruiz N., Kahne D., Silhavy T.J. Transport of lipopolysaccharide across the cell envelope: the long road of discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:677–683. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raetz C.R., Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raetz C.R., Reynolds C.M., Bishop R.E. Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowles T.J., Scott-Tucker A., Henderson I.R. Membrane protein architects: the role of the BAM complex in outer membrane protein assembly. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:206–214. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagan C.L., Silhavy T.J., Kahne D. β-Barrel membrane protein assembly by the Bam complex. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011;80:189–210. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061408-144611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crooke E., Wickner W. Trigger factor: a soluble protein that folds pro-OmpA into a membrane-assembly-competent form. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:5216–5220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bechtluft P., Nouwen N., Driessen A.J. SecB—a chaperone dedicated to protein translocation. Mol. Biosyst. 2010;6:620–627. doi: 10.1039/b915435c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papanikou E., Karamanou S., Economou A. Identification of the preprotein binding domain of SecA. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:43209–43217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driessen A.J., Nouwen N. Protein translocation across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:643–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.160747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rigel N.W., Silhavy T.J. Making a β-barrel: assembly of outer membrane proteins in Gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2012;15:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y.E., Hipp M.S., Hartl F.U. Molecular chaperone functions in protein folding and proteostasis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013;82:323–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060208-092442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saibil H.R., Fenton W.A., Horwich A.L. Structure and allostery of the chaperonin GroEL. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:1476–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwich A.L., Fenton W.A. Chaperonin-mediated protein folding: using a central cavity to kinetically assist polypeptide chain folding. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2009;42:83–116. doi: 10.1017/S0033583509004764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doyle S.M., Genest O., Wickner S. Protein rescue from aggregates by powerful molecular chaperone machines. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:617–629. doi: 10.1038/nrm3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh E., Becker A.H., Bukau B. Selective ribosome profiling reveals the cotranslational chaperone action of trigger factor in vivo. Cell. 2011;147:1295–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann A., Bukau B., Kramer G. Structure and function of the molecular chaperone Trigger Factor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1803:650–661. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holck A., Lossius I., Kleppe K. Purification and characterization of the 17 K protein, a DNA-binding protein from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1987;914:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(87)90160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thome B.M., Hoffschulte H.K., Müller M. A protein with sequence identity to Skp (FirA) supports protein translocation into plasma membrane vesicles of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1990;269:113–116. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koski P., Rhen M., Vaara M. Isolation, cloning, and primary structure of a cationic 16-kDa outer membrane protein of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:18973–18980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geyer R., Galanos C., Golecki J.R. A lipopolysaccharide-binding cell-surface protein from Salmonella minnesota. Isolation, partial characterization and occurrence in different Enterobacteriaceae. Eur. J. Biochem. 1979;98:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb13156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schäfer U., Beck K., Müller M. Skp, a molecular chaperone of gram-negative bacteria, is required for the formation of soluble periplasmic intermediates of outer membrane proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:24567–24574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen R., Henning U. A periplasmic protein (Skp) of Escherichia coli selectively binds a class of outer membrane proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;19:1287–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walton T.A., Sousa M.C. Crystal structure of Skp, a prefoldin-like chaperone that protects soluble and membrane proteins from aggregation. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korndörfer I.P., Dommel M.K., Skerra A. Structure of the periplasmic chaperone Skp suggests functional similarity with cytosolic chaperones despite differing architecture. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:1015–1020. doi: 10.1038/nsmb828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarchow S., Lück C., Skerra A. Identification of potential substrate proteins for the periplasmic Escherichia coli chaperone Skp. Proteomics. 2008;8:4987–4994. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denoncin K., Schwalm J., Collet J.F. Dissecting the Escherichia coli periplasmic chaperone network using differential proteomics. Proteomics. 2012;12:1391–1401. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moon C.P., Zaccai N.R., Fleming K.G. Membrane protein thermodynamic stability may serve as the energy sink for sorting in the periplasm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:4285–4290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212527110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burmann B.M., Wang C., Hiller S. Conformation and dynamics of the periplasmic membrane-protein-chaperone complexes OmpX-Skp and tOmpA-Skp. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:1265–1272. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu J., Mayer C., Kleinschmidt J.H. The trimeric periplasmic chaperone Skp of Escherichia coli forms 1:1 complexes with outer membrane proteins via hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;374:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel G.J., Behrens-Kneip S., Kleinschmidt J.H. The periplasmic chaperone Skp facilitates targeting, insertion, and folding of OmpA into lipid membranes with a negative membrane surface potential. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10235–10245. doi: 10.1021/bi901403c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McMorran L.M., Bartlett A.I., Brockwell D.J. Dissecting the effects of periplasmic chaperones on the in vitro folding of the outer membrane protein PagP. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:3178–3191. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aasland R., Coleman J., Kleppe K. Identity of the 17-kilodalton protein, a DNA-binding protein from Escherichia coli, and the firA gene product. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:5916–5918. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5916-5918.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulieris P.V., Behrens S., Kleinschmidt J.H. Folding and insertion of the outer membrane protein OmpA is assisted by the chaperone Skp and by lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:9092–9099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211177200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Cock H., Brandenburg K., Seydel U. Non-lamellar structure and negative charges of lipopolysaccharides required for efficient folding of outer membrane protein PhoE of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:5114–5119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freudl R., Schwarz H., Henning U. An outer membrane protein (OmpA) of Escherichia coli K-12 undergoes a conformational change during export. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:11355–11361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferguson A.D., Hofmann E., Welte W. Siderophore-mediated iron transport: crystal structure of FhuA with bound lipopolysaccharide. Science. 1998;282:2215–2220. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vandeputte-Rutten L., Kramer R.A., Gros P. Crystal structure of the outer membrane protease OmpT from Escherichia coli suggests a novel catalytic site. EMBO J. 2001;20:5033–5039. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qu J., Behrens-Kneip S., Kleinschmidt J.H. Binding regions of outer membrane protein A in complexes with the periplasmic chaperone Skp. A site-directed fluorescence study. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4926–4936. doi: 10.1021/bi9004039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bos M.P., Robert V., Tommassen J. Biogenesis of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;61:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaneechoutte M., Verschraegen G., Van Den Abeele A.M. Serological typing of Branhamella catarrhalis strains on the basis of lipopolysaccharide antigens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990;28:182–187. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.182-187.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan L., Grewal P.S. Characterization of the first molluscicidal lipopolysaccharide from Moraxella osloensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:3646–3649. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3646-3649.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pervushin K., Riek R., Wüthrich K. Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wider G., Dreier L. Measuring protein concentrations by NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2571–2576. doi: 10.1021/ja055336t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chou J.J., Baber J.L., Bax A. Characterization of phospholipid mixed micelles by translational diffusion. J. Biomol. NMR. 2004;29:299–308. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000032560.43738.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Güntert P., Dötsch V., Wüthrich K. Processing of multi-dimensional NMR data with the new software PROSA. J. Biomol. NMR. 1992;2:619–629. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller R.L.J. Cantina Verlag; Goldau, Switzerland: 2004. The Computer Aided Resonance Assignment Tutorial. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Landau M., Mayrose I., Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2005: the projection of evolutionary conservation scores of residues on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W299–W302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ashkenazy H., Erez E., Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2010: calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W529–W533. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Angermüller C., Biegert A., Söding J. Discriminative modelling of context-specific amino acid substitution probabilities. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3240–3247. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Biegert A., Söding J. Sequence context-specific profiles for homology searching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3770–3775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810767106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li W., Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lamarche M.G., Kim S.H., Harel J. Modulation of hexa-acyl pyrophosphate lipid A population under Escherichia coli phosphate (Pho) regulon activation. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:5256–5264. doi: 10.1128/JB.01536-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacKerell A.D., Bashford D., Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bjelkmar P., Larsson P., Lindahl E. Implementation of the CHARMM force field in GROMACS: analysis of protein stability effects from correction maps, virtual interaction sites, and water models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:459–466. doi: 10.1021/ct900549r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paramo T., Piggot T.J., Bond P.J. The structural basis for endotoxin-induced allosteric regulation of the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) innate immune receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:36215–36225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.501957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berendsen H.J.C., van der Spoel D., van Drunen R. GROMACS: a message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Berendsen H.J. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hess B., Kutzner C., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics. 1996;14::33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bolen D.W., Santoro M.M. Unfolding free energy changes determined by the linear extrapolation method. 2. Incorporation of delta G degrees N-U values in a thermodynamic cycle. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8069–8074. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sasaki H., White S.H. Aggregation behavior of an ultra-pure lipopolysaccharide that stimulates TLR-4 receptors. Biophys. J. 2008;95:986–993. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brandenburg K., Andrä J., Garidel P. Physicochemical properties of bacterial glycopolymers in relation to bioactivity. Carbohydr. Res. 2003;338:2477–2489. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Santos N.C., Silva A.C., Saldanha C. Evaluation of lipopolysaccharide aggregation by light scattering spectroscopy. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:96–100. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200390020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Cock H., Schäfer U., Tommassen J. Affinity of the periplasmic chaperone Skp of Escherichia coli for phospholipids, lipopolysaccharides and non-native outer membrane proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;259:96–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park B.S., Song D.H., Lee J.O. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature. 2009;458:1191–1195. doi: 10.1038/nature07830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eckert J.K., Kim Y.J., Schumann R.R. The crystal structure of lipopolysaccharide binding protein reveals the location of a frequent mutation that impairs innate immunity. Immunity. 2013;39:647–660. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gomery K., Müller-Loennies S., Evans S.V. Antibody WN1 222-5 mimics Toll-like receptor 4 binding in the recognition of LPS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:20877–20882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209253109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suits M.D., Sperandeo P., Jia Z. Novel structure of the conserved gram-negative lipopolysaccharide transport protein A and mutagenesis analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;380:476–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tran A.X., Dong C., Whitfield C. Structure and functional analysis of LptC, a conserved membrane protein involved in the lipopolysaccharide export pathway in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:33529–33539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.144709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dong H., Xiang Q., Dong C. Structural basis for outer membrane lipopolysaccharide insertion. Nature. 2014;511:52–56. doi: 10.1038/nature13464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qiao S., Luo Q., Huang Y. Structural basis for lipopolysaccharide insertion in the bacterial outer membrane. Nature. 2014;511:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature13484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Malojčić G., Andres D., Kahne D. LptE binds to and alters the physical state of LPS to catalyze its assembly at the cell surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:9467–9472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402746111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Okuda S., Freinkman E., Kahne D. Cytoplasmic ATP hydrolysis powers transport of lipopolysaccharide across the periplasm in E. coli. Science. 2012;338:1214–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1228984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferguson A.D., Welte W., Diederichs K. A conserved structural motif for lipopolysaccharide recognition by procaryotic and eucaryotic proteins. Structure. 2000;8:585–592. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Uversky V.N. Flexible nets of malleable guardians: intrinsically disordered chaperones in neurodegenerative diseases. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1134–1166. doi: 10.1021/cr100186d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lupas A. Coiled coils: new structures and new functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996;21:375–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dicker I.B., Seetharam S. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the firA gene and the firA200(Ts) allele from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:334–344. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.334-344.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schwalm J., Mahoney T.F., Silhavy T.J. Role for Skp in LptD assembly in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:3734–3742. doi: 10.1128/JB.00431-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chng S.S., Xue M., Kahne D. Disulfide rearrangement triggered by translocon assembly controls lipopolysaccharide export. Science. 2012;337:1665–1668. doi: 10.1126/science.1227215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.