Abstract

AIM: To investigate the incidence, characteristics, and risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Chinese patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC).

METHODS: We reviewed the data of 52 PBC-associated HCC patients treated at Beijing 302 Hospital from January 2002 to December 2013 and analyzed its incidence and characteristics between the two genders. The risk factors for PBC-associated HCC were analyzed via a case-control study comprising 20 PBC patients with HCC and 77 matched controls without HCC. The matched factors included gender, age, follow-up period and Child-Pugh scores. Conditional logistic regression was used to evaluate the odds ratios of potential risk factors for HCC development. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS: The incidence of HCC in Chinese PBC patients was 4.13% (52/1255) and was significantly higher in the males (9.52%) than in the females (3.31%). Among the 52 PBC patients with HCC, 55.76% (29/52) were diagnosed with HCC and PBC simultaneously, and 5.76% (3/52) were diagnosed with HCC before PBC. The males with PBC-associated HCC were more likely than the females to have undergone blood transfusion (18.75% vs 8.33%, P = 0.043), consumed alcohol (31.25% vs 8.33%, P = 0.010), smoked (31.25% vs 8.33%, P = 0.010), had a family history of malignancy (25% vs 5.56%, P = 0.012), and had serious liver inflammation, as indicated by the elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (P < 0.05). Conditional logistic regression analysis revealed that body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.116, 95%CI: 1.002-1.244, P = 0.045] and history of alcohol intake (AOR = 10.294, 95%CI: 1.108-95.680, P = 0.040) were significantly associated with increased odds of HCC development in PBC patients.

CONCLUSION: HCC is not rare in Chinese PBC patients. Risk factors for PBC-associated HCC include BMI ≥ 25 and a history of alcohol intake. In addition to regular monitoring, PBC patients may benefit from abstinence from alcohol and body weight control.

Keywords: Primary biliary cirrhosis, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Body mass index, History of alcohol intake, Case-control study

Core tip: Previous studies have suggested that many factors are associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development in primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) patients. However, the evaluation of risk factors using a case-control study has not been reported. This case-control study analyzed the characteristics of PBC-associated HCC and investigated the relevant risk factors. The incidence of HCC was 4.13% in Chinese PBC patients, and it was more frequent in the male patients. Our results show for the first time that body mass index ≥ 25 and a history of alcohol intake are independent risk factors for HCC in PBC patients.

INTRODUCTION

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a progressive autoimmune liver disease that mainly affects middle-aged women. The disease is characterized by elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels, the presence of antimitochondrial antibodies, and the immune-mediated destruction of small-to-medium bile ducts in the liver. PBC can result in chronic cholestasis and the eventual development of irreversible cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1].

The clinical manifestations of PBC vary widely over the course of disease, and there are few treatment options. Increased awareness by clinicians and improved diagnostic techniques have enabled its diagnosis in a greater number of asymptomatic patients. However, the only drug approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration to treat PBC is ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), which has not been proven to satisfactorily lower mortality rates[2]. Currently, liver transplantation is the only effective treatment for PBC patients who are in the terminal stage or have liver failure[3].

In general, HCC only occurs at the end stages of liver diseases, and the most common risk factor is infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV)[4,5]. Until recently, the development of HCC in PBC patients was considered rare[6]. However, with early diagnosis and improved treatment, the survival time has increased along with the incidence of HCC in these patients, which now ranges from 0.76% to 5.9%[7-12]. Although older age, male gender, advanced histological stage, and history of blood transfusion have been associated with significantly increased odds of HCC, no factors have been found to be directly correlated with HCC development in PBC patients[7,13,14] other than comorbidities, such as HBV or HCV infection and portal hypertension[13-15].

Most of the studies cited above were based on populations in Europe, the United States, or Japan. In China, the greater awareness of PBC among physicians and the application of new laboratory tests have revealed that this disease is not as rare as formerly thought, and a recent study shows that its prevalence rate is 492 cases per million in southern China[16], but the national data is still lacking. Furthermore, there have been several studies concerning the diagnosis and treatment of HCC in PBC patients[17-20]. However, little is specifically known about the epidemiology of PBC-associated HCC in Chinese population.

In this study, we retrospectively assessed 52 PBC patients with HCC out of 1255 PBC patients to clarify the incidence and clinical characteristics of PBC-associated HCC in China and explored potential risk factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and subjects

The Beijing 302 Hospital Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol. This study involved an analysis of anonymous secondary data; therefore, no informed consent from patients was required.

Beijing 302 Hospital is the largest liver disease hospital in China. The hospital’s clinical database holds records of the clinical histories, physical and laboratory findings, and treatments of admitted patients, including those with viral hepatitis, autoimmune liver diseases, drug-induced hepatitis and inherited liver diseases. This database has been utilized previously in several studies[21-23].

This was a retrospective study of patients diagnosed with PBC and treated at Beijing 302 Hospital between January 2002 and December 2013. The diagnosis of PBC was established when any two of the following three criteria were met: biochemical evidence of cholestasis (based mainly on ALP elevation); the presence of antimitochondrial autoantibodies; and histological evidence of non-suppurative destructive cholangitis and destruction of interlobular bile ducts[24]. Patients were excluded who were HBV carriers, positive for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) or anti-HCV antibody, or had autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), Wilson’s disease, or α-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

This study comprised 1255 PBC patients, most of whom were receiving regular UDCA treatment. All patients were followed regularly, at least every 3-6 mo after hospital discharge, with biochemistry tests and abdominal sonography. A diagnosis of HCC was made based on imaging tests (magnetic resonance imaging with contrast media, computed tomography with contrast media or ultrasonic examination) or histological findings (surgery or biopsy)[13]. During the study period, 52 cases of HCC were identified that met the above criteria for PBC and HCC.

A positive history of alcohol intake was defined as alcohol consumption at least once per week for at least 1 year (≥ 20 g/d for women and ≥ 30 g/d for men) without achieving the diagnostic criteria of alcoholic hepatitis[13]. A positive history of smoking was defined as cigarette smoking for ≥ 4 d per week for at least 1 year[24]. A family history of malignancy included one or more direct relatives suffering from any malignant tumor. Past HBV infection was defined as an HBsAg-negative status and positive HBsAb and HBcAb statuses. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by height squared (in meters).

Study design

We first determined the incidence of primary HCC in Chinese PBC patients. In addition, we reviewed the cases and collected the following laboratory data: alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ALP, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), albumin, total bilirubin, and α-fetoprotein levels, prothrombin time, and white blood cell, red blood cell, and platelet counts. The main complaints (pruritus, fatigue, anorexia, and discomfort in the hepatic region), physical findings (jaundice and ascites) and medical history (blood transfusion, past HBV infection, alcohol intake, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and family history of malignancy) were also recorded for these patients at the time of HCC diagnosis. The patients were stratified by gender for further statistical comparisons to analyze the characteristics between the two genders.

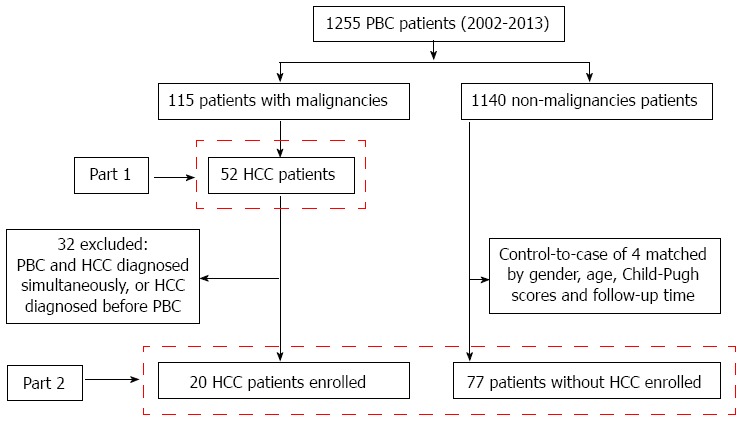

Gender and older age have been regarded as risk factors for PBC-associated HCC development[13,14,26]. To determine other possible risk factors, we conducted a case-control study (Figure 1). Twenty patients diagnosed with PBC prior to HCC were identified. In addition, we selected PBC patients without HCC as controls, matching 4 controls to each PBC patient with HCC by age, gender, Child-Pugh scores and follow-up period. Because there were not enough matched control subjects for two cases, we used only two and three controls for these patients, respectively[13]. We recorded the family history of malignancy, clinical and laboratory data, physical findings, and comorbidities for these patients at the time of PBC diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Derivation and definition of the study population. Part 1: Analysis of the characteristics of 52 patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); Part 2: Analysis of potential risk factors for the development of HCC in PBC patients.

Statistical analysis

The data are reported as the mean ± SD or number (percentage) of patients. The Mann-Whitney U and χ2 tests were used as nonparametric and independent tests, respectively. Survival rates were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method. Variables with a P-value < 0.1 were considered to be potential factors for the case-control study. Then, a conditional logistic regression model was used to estimate the relative magnitudes in relation to the potential factors. The odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were calculated using patients without HCC as a reference. Analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 software for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). All statistical tests were two-sided. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The incidence and characteristics of PBC-associated HCC were identified in our database of 1255 PBC Chinese patients, which included 168 men and 1087 women. During nearly 12 years of follow-up, 115 patients were diagnosed with malignant tumors. There were 52 HCC patients, including 16 men and 36 women (Table 1). The overall HCC incidence was 4.13% (52/1255), and the incidence in men (9.52%) was almost three times higher than that in women (3.31%). The average follow-up period was 43.44 ± 39.91 mo for the entire group, with no statistically significant difference between the men (29.88 ± 22.84 mo) and women (49.47 ± 44.46 mo; P = 0.346).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical features of primary biliary cirrhosis patients at hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis n (%)

| Variable | Total | Men | Women | P value1 |

| (n = 52) | (n = 16) | (n = 36) | ||

| Age (yr) | 65.75 ± 10.09 | 69.75 ± 8.09 | 63.97 ± 10.47 | 0.093 |

| Han nationality | 47 (90.38) | 14 (87.50) | 33 (91.67) | 0.638 |

| Body mass index ≥ 25 (kg/m2) | 16 (30.77) | 4 (25.00) | 12 (33.33) | 0.548 |

| History of blood transfusion | 6 (11.54) | 3 (18.75) | 3 (8.33) | 0.043 |

| Past HBV infection | 29 (55.77) | 10 (62.50) | 19 (52.78) | 0.519 |

| Alcohol intake | 8 (15.38) | 5 (31.25) | 3 (8.33) | 0.035 |

| Smoking | 8 (15.38) | 5 (31.25) | 3 (8.33) | 0.010 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 8 (15.38) | 0 | 8 (22.22) | 0.040 |

| Hypertension | 12 (23.08) | 5 (31.25) | 7 (19.44) | 0.165 |

| Family history of malignancy | 6 (11.54) | 4 (25.00) | 2 (5.56) | 0.012 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 52 (100.00) | 16 (100.00) | 36 (100.00) | 1.000 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≥ 3 cm | 35 (67.31) | 11 (68.75) | 24 (66.67) | 0.882 |

| < 3 cm | 17 (32.69) | 5 (31.25) | 12 (33.33) | 0.882 |

| Tumor number | ||||

| Single | 29 (55.77) | 9 (56.25) | 20 (55.56) | 0.963 |

| Multiple | 23 (44.23) | 7 (43.75) | 16 (44.44) | 0.963 |

| Pruritus | 4 (7.70) | 3 (18.75) | 1 (2.78) | 0.046 |

| Fatigue | 37 (71.15) | 13 (81.25) | 24 (66.67) | 0.284 |

| Anorexia | 20 (38.46) | 5 (31.25) | 15 (41.67) | 0.476 |

| Discomfort in hepatic region | 11 (21.15) | 4 (25.00) | 7 (19.44) | 0.651 |

| Jaundice | 30 (57.69) | 11 (68.75) | 19 (52.78) | 0.282 |

| Ascites | 41 (78.85) | 12 (75.00) | 29 (80.56) | 0.651 |

Men compared with women. HBV: Hepatitis B virus; NA: Not applicable.

Most of the 52 PBC patients with HCC were of Han nationality and were older than 60 years. Comparative analysis of the men and women showed that HCC prevalence was significantly higher among the men with a history of blood transfusion (P = 0.043), alcohol intake (P = 0.035), or smoking (P = 0.010) and a family history of malignancy (P = 0.012) (that is, one patient’s mother had lung cancer, another patient’s father and younger brother had gastric cancer, and one patient’s father had HCC). More women than men had type-2 diabetes mellitus (P = 0.040).

All PBC patients were at the stage of liver cirrhosis when HCC was diagnosed. In most cases, there was a single tumor (55.77%), and the tumor size was more than 3 cm (67.31%). Portal venous thrombosis was present in five patients. Fatigue was the most common symptom (71.15%, 37/52), followed by anorexia (38.46%, 20/52) and discomfort in the hepatic region (21.15%, 11/52). Pruritus only occurred in four patients, including three men and one woman (18.75% vs 2.78%, P = 0.046). There were no significant differences in BMI, past HBV infection, history of hypertension, clinical manifestations, tumor size, or number of tumors between the two genders.

The serum levels of ALT, AST, ALP, and GGT were significantly higher in men than in women (P < 0.05 for all; Table 2). Approximately 65.38% of patients with PBC-associated HCC had elevated serum α-fetoprotein levels, but no significant differences were found between the men and women (P = 0.356).

Table 2.

Biochemical characteristics of male and female primary biliary cirrhosis patients at hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis

| Variable | Total | Men | Women | P value1 |

| (n = 52) | (n = 16) | (n = 36) | ||

| Alanine transaminase (U/L) | 43.04 ± 42.28 | 64.25 ± 55.48 | 33.61 ± 31.45 | 0.012 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 77.83 ± 56.24 | 111.38 ± 72.47 | 62.92 ± 40.19 | 0.005 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 229.29 ± 190.44 | 308.81 ± 209.37 | 193.94 ± 172.87 | 0.015 |

| γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (U/L) | 156.90 ± 179.05 | 253.13 ± 220.54 | 114.14 ± 140.55 | 0.010 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 28.42 ± 5.67 | 28.06 ± 5.64 | 28.58 ± 5.75 | 0.720 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/dL) | 61.19 ± 102.13 | 74.14 ± 64.25 | 55.43 ± 115.41 | 0.071 |

| α-fetoprotein elevating, n (%) | 34 (65.38) | 9 (56.25) | 25 (69.44) | 0.356 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 13.49 ± 2.20 | 12.79 ± 1.91 | 13.8 ± 2.28 | 0.159 |

| International standardization ratio | 1.15 ± 0.23 | 1.13 ± 0.14 | 1.17 ± 0.26 | 0.410 |

| White blood cells (109/L) | 4.29 ± 2.35 | 5.13 ± 2.32 | 3.92 ± 2.30 | 0.073 |

| Red blood cells (1012/L) | 3.31 ± 0.66 | 3.56 ± 0.76 | 3.19 ± 0.60 | 0.096 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 76.57 ± 40.50 | 85.20 ± 48.26 | 72.74 ± 36.64 | 0.506 |

Men compared with women. Data expressed as mean ± SD or n (%) of patients.

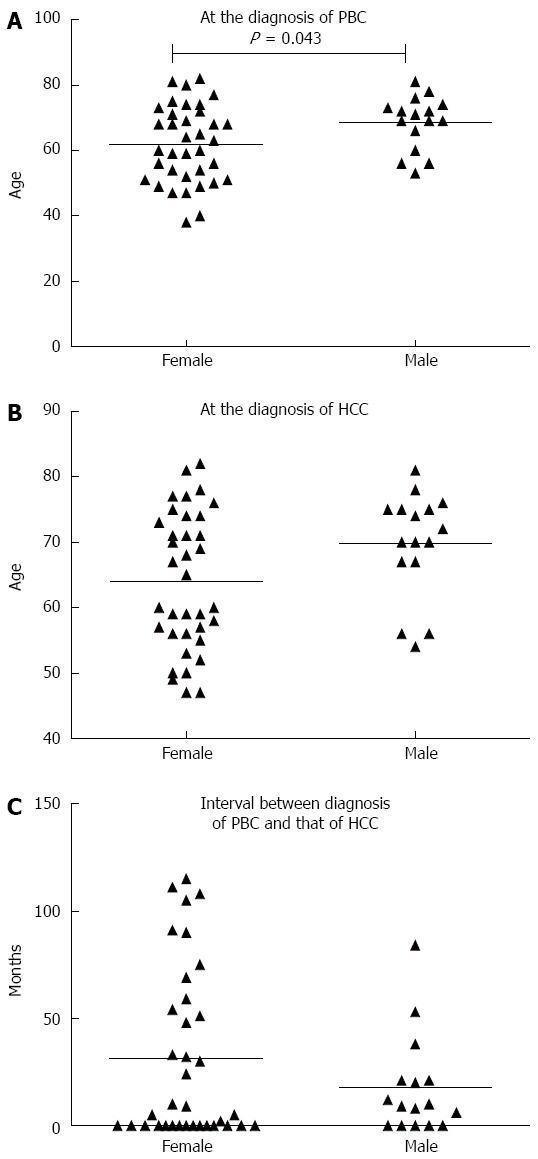

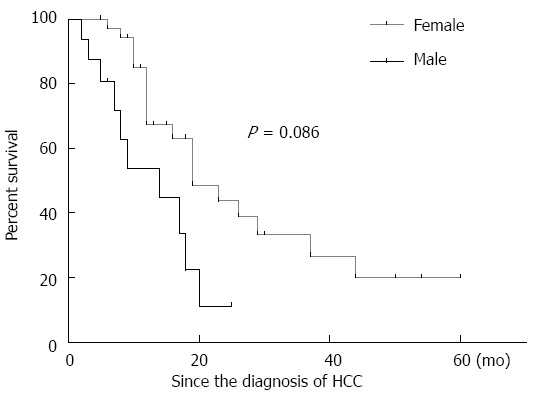

Of the 52 PBC patients with HCC, 55.76% (29/52) received a diagnosis of HCC and PBC simultaneously, and 5.76% (3/52) were found to have HCC before being diagnosed with PBC. For the remaining 20 patients, HCC was diagnosed after PBC, and the characteristics of these patients were used for further studies. Upon diagnosis of PBC, the men were significantly older than the women (68.44 ± 8.23 years vs 61.78 ± 11.75 years, P = 0.043), and the men also tended to be older (69.75 ± 8.09 years) than the women (63.97 ± 10.47 years) at the time of HCC diagnosis, but this difference was not significant (P = 0.056). Regarding the interval between the diagnosis of PBC and the development of HCC, there was no statistically difference between the men (17.63 ± 23.15 mo) and women (31.27 ± 39.61 mo; P = 0.21; Figure 2). The prognosis of the men tended to be slightly poorer than that of the women, although this difference was not statistical significant (P = 0.086) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Average ages at the times of primary biliary cirrhosis diagnosis and hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis, and intervals between these two diagnoses. The average age at primary biliary cirrhosis diagnosis was higher in men than in women (P < 0.05). Each triangle represents one patient. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; PBC: Primary biliary cirrhosis.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve for survival for the males and females with primary biliary cirrhosis-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. There was no statistically significant difference between the two genders (P = 0.086). HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Risk factors for HCC development in PBC patients

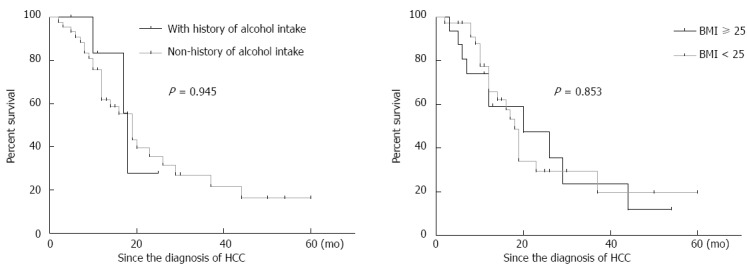

Of 52 patients with PBC and HCC, we selected 20 in whom PBC was diagnosed prior to HCC to analyze risk factors for HCC development. Using a case-control study design, records from these 20 cases and 77 matched controls (PBC patients without HCC) were analyzed to identify risk factors for the development of HCC in Chinese PBC patients (Table 3). Further assessments indicated that there were no significant differences in age, gender ratio, Child-Pugh scores or follow-up period between the two groups. However, BMI ≥ 25 (P = 0.015), family history of malignancy (P = 0.014), and history of alcohol intake (P = 0.022) significantly differed between the two groups, and in further univariate analysis, these three factors were found to be associated with increases in crude ORs for HCC development (Table 4). There were no significant differences between the PBC-associated HCC cases and controls with regard to history of blood transfusion, history of smoking, diabetes mellitus, the levels of antimitochondrial autoantibodies, immunoglobulin, aminotransferase, α-fetoprotein, triglycerides or total cholesterol, prothrombin time, use of UDCA, or clinical stage. Adjustments for possible confounders (UDCA therapy and α-fetoprotein) only slightly altered the ORs. In the final model, BMI ≥ 25 [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.294; 95%CI, 1.054-1.589] and history of alcohol intake (AOR = 9.204; 95%CI, 1.019-83.129) were independent risk factors for HCC development in PBC patients (Table 4). However, BMI ≥ 25 and history of alcohol intake had no significant impact on the survival rate of patients with PBC-associated HCC (P = 0.853 and P = 0.945, respectively; Figure 4).

Table 3.

Demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of primary biliary cirrhosis patients with or without hepatocellular carcinoma at primary biliary cirrhosis diagnosis n (%)

| Variable | PBC with HCC (n = 20) | PBC without HCC (n = 77) | P value |

| Follow-up (mo) | 46.45 ± 41.85 | 57.20 ± 36.33 | 0.144 |

| Male | 8 (40) | 30 (38.97) | 1.000 |

| Female | 12 (60) | 47 (61.04) | 1.000 |

| Age (yr) | 61.05 ± 11.92 | 60.77 ± 11.52 | 0.808 |

| Han nationality | 18 (90.00) | 73 (94.81) | 1.000 |

| Body mass index ≥ 25 (kg/m2) | 6 (30) | 7 (9.10) | 0.015 |

| History of blood transfusion | 0 | 4 (5.19) | 0.300 |

| Family history of malignancy | 4 (20) | 3 (3.90) | 0.014 |

| History of alcohol intake | 7 (35) | 10 (12.99) | 0.022 |

| History of smoking | 4 (20) | 6 (7.79) | 0.112 |

| History of type 2 diabetes mellitus | 3 (15) | 7 (9.09) | 0.441 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 17 (85) | 62 (79.22) | 0.958 |

| Hepatitis B core antibody | 9 (45) | 37 (48.05) | 0.562 |

| Child-Pugh, A/B/C (n/n/n) | 8/11/1 | 32/42/3 | 0.900 |

| Antimitochondrial autoantibodies | |||

| (+) | 18 (90) | 65 (84.42) | 0.529 |

| (-) | 2 (10) | 12 (15.58) | 0.529 |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 2.78 ± 1.32 | 3.13 ± 2.07 | 0.686 |

| IgM (mg/dL) | 3.46 ± 1.99 | 4.07 ± 3.34 | 0.482 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 15.86 ± 3.24 | 15.55 ± 6.27 | 0.657 |

| White blood cells (× 109/L) | 4.14 ± 1.38 | 4.85 ± 2.52 | 0.449 |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dL) | 109.01 ± 16.28 | 108.42 ± 20.69 | 0.438 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 80.15 ± 63.50 | 75.91 ± 67.18 | 0.715 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 97.5 ± 64.48 | 92.60 ± 72.85 | 0.611 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 278.25 ± 155.42 | 376.10 ± 433.46 | 0.918 |

| γ-glutamyl transpeptidase level (U/L) | 294.65 ± 285.01 | 316.29 ± 331.95 | 0.748 |

| Total bilirubin level (mg/dL) | 46.84 ± 64.34 | 46.19 ± 62.37 | 0.858 |

| Albumin level (g/dL) | 32.75 ± 6.20 | 33.21 ± 5.58 | 0.876 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.03 ± 0.43 | 1.36 ± 0.82 | 0.207 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.20 ± 1.38 | 5.75 ± 4.05 | 0.113 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 12.34 ± 1.64 | 12.23 ± 1.37 | 0.813 |

| α-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 14.75 ± 21.84 | 7.62 ± 4.46 | 0.072 |

| Use of ursodeoxycholic acid | 19 (95) | 60 (77.9) | 0.080 |

| Effective | 8 (42.1) | 23 (38.3) | 0.769 |

| Clinical stage | |||

| Asymptomatic | 0 (0) | 9 (11.69) | 0.110 |

| Symptomatic | 20 (100) | 68 (88.31) | 0.110 |

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; PBC: Primary biliary cirrhosis.

Table 4.

Univariate (unadjusted) and multivariate (adjusted) conditional logistic regression analysis of potential risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in primary biliary cirrhosis patients n (%)

| Variable |

Univariate OR |

Multivariate OR |

||

| (95%CI) | P value | (95%CI) | P value | |

| Body mass index ≥ 25 (kg/m2) | 3.819 (1.140-12.792) | 0.006 | 1.116 (1.002-1.244) | 0.045 |

| Family history of malignancy | 6.971 (1.253-38.790) | 0.027 | NA | 0.175 |

| History of alcohol intake | 11.525 (1.338-99.280) | 0.026 | 10.294 (1.108-95.680) | 0.040 |

| α-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 1.132 (1.016-1.260) | 0.025 | NA | 0.058 |

| Use of ursodeoxycholic acid (%) | 78.828 (0.053-1.169 × 105) | 0.241 | NA | 0.159 |

OR: Odds ratio; NA: Not applicable.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves for survival for the primary biliary cirrhosis patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients were divided into two groups according to history of alcohol intake and body mass index. BMI: Body mass index.

DISCUSSION

HCC often develops in patients with HBV or HCV infection, but its incidence has recently increased in patients with autoimmune liver diseases, including PBC, AIH, PSC, and overlap syndrome. The risks of hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies are significantly increased in patients with AIH and PSC, and response to therapy is often associated with prognosis[27,28]. We conducted a retrospective study of patients treated at Beijing 302 Hospital between January 2002 and December 2013 to investigate the likelihood of developing HCC, its clinical features, and its related risk factors in Chinese PBC patients. We first found that HCC was present in 4.13% of PBC patients. The male PBC patients were more likely than the females to develop HCC, and it was more serious in the males. This is the first report that the risk factors BMI ≥ 25 and history of alcohol intake are independently associated with HCC development in Chinese PBC patients.

A previous meta-analysis has reported that the risk of HCC in PBC patients is more than 18.8-fold that of the general population[29]. This finding indicates that it is necessary to screen PBC patients for HCC. The data from these two studies suggest that HCC is not as common in PBC patients as it is in those with other forms of cirrhosis[8,30], while another study has reported conflicting results[31]. This may be due to discrepancies in cirrhosis stages, follow-up periods or study samples. In 1997, Jones et al[7] reported that the incidence of PBC-associated HCC in the United Kingdom was 5.9%, and their findings were based on 667 PBC patients who were followed for 20 years. However, a 9-year follow-up study of 1689 PBC patients in the United States by Angulo et al[32] found that the incidence of PBC-associated HCC was 0.89%. Recently, Harada et al[26] reported an incidence of 2.4% in Japan. In our study, we reported that its incidence in Chinese PBC patients was 4.13%. This is in accord with other Chinese studies, which have reported values ranging from 2.57% in mainland China (350 cases followed for 5 years)[33] to 5.2% in Taiwan (96 cases followed for 18 years)[34]. However, the incidence might be underestimated in our paper, because some patients, who received liver transplantation, may develop HCC in their natural history. In addition, in the present study, approximately 60% of the patients received diagnoses of PBC and HCC simultaneously or of HCC prior to PBC, which is unique to China. These findings indicate that a lack of recognition of PBC still exists in China and that this condition should be taken seriously by the development of an intensive surveillance program.

In the present study, the incidence of HCC in the male PBC patients was 3-fold higher than that in the female patients. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies[7,8,13-15]. These results are also in agreement with the finding that the severity of liver injury, as indirectly indicated by the liver function data, was more serious in male patients. Considering the effect of gender, we suggest that estrogen levels may have a role in PBC-associated HCC. Yeh et al[35] and Naugler et al[36] have found that estrogen can protect hepatocytes from malignant transformation, and male patients are more likely to develop HCC due to a lack of estrogen, although PBC mainly affects women. Moreover, some studies have shown that the absence of the Y chromosome is associated with multiple malignant diseases[37-39]. Unhealthy habits (such as alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking), history of blood transfusion, and family history of malignancy may also contribute to HCC development in male PBC patients[26]. Above all, based on these studies, male PBC patients in particular should be screened carefully for HCC because of its higher incidence and severity in men. However, the exact reasons for these gender differences remain unknown and require further study to determine.

Studies of PBC-associated HCC have reported the involvement of some risk factors in its development, including male gender, blood transfusion, advanced histological stage, and age at PBC diagnosis[7,8,13-15]. Results are not always congruent due to differences in sample sizes, follow-up periods, and methodologies. Based on prior studies, we conducted a case-control study of Chinese PBC patients with HCC compared with those without HCC, matching factors that included gender, age, follow-up time and Child-Pugh score[40]. We enrolled 20 HCC cases with complete data at PBC diagnosis and HCC diagnosis. We first found that BMI ≥ 25 and history of alcohol intake were risk factors for PBC-associated HCC, which is consistent with previous studies[41,42]. There were two studies showing that overweight status (BMI ≥ 25) was associated with advanced fibrosis in PBC patients[25,43], indicating that the immune reactions triggered by obesity and alcohol intake (even in small quantities) might contribute to PBC stage progression[24]. Moreover, several studies have shown that obesity and history of alcohol intake synergistically increase the incidence of HCC by aggravating hepatic insulin resistance and necroinflammation in patients with HBV or HCV infection, HBV/HCV co-infection, or other liver diseases[24,44,45]. Therefore, these two factors may promote HCC development in PBC patients. However, conflicting opinions remain concerning these two factors[13,14], due to differences among ethnicities in the sensitivity to liver injury caused by alcohol[46], the lack of a consistent definition of alcohol intake, and differences in sample sizes and follow-up time.

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. First, although histological stage at PBC diagnosis is a known important risk factor for HCC, we could not obtain this information because liver biopsies were not consistently performed. Second, UDCA treatment and α-fetoprotein level were not found to be risk factors for the development of PBC-associated HCC in our study. Racial factors may play a role, but basic studies of its underlying mechanisms are needed. Third, the retrospective nature of our study design may have made it difficult to obtain risk factors specific to PBC patients; thus, a further prospective study is warranted that should include more comprehensive groups. Fourth, there might have been an inclusion bias because only 20 cases met the inclusion criteria; thus, there may have been an insufficient number of patients evaluated to obtain adequate positive findings. Therefore, a study with a larger sample size should be performed.

In conclusion, HCC is not rare in Chinese patients with PBC. The incidence of PBC-associated HCC is higher and liver injury is more serious in men than in women. Because high BMI and alcohol intake are risk factors for HCC in PBC patients, these patients should be encouraged to stop alcohol consumption and control body weight.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Professor Ping-Ping He (Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Peking University Health Science Center) for her critical revision of the statistical analysis section.

COMMENTS

Background

Previous studies have indicated that some risk factors are involved in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development in primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) patients. However, the evaluation of potential risk factors using a case-control study has not been reported.

Research frontiers

There is a lack of information regarding the risk factors for and incidence of PBC-associated HCC in China. Potential factors contributing to disease progression and death were included in this study to identify independent risk factors for HCC development.

Related publications

This is the first case-control study to investigate risk factors for HCC development in PBC patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This study is the first case-control study to investigate risk factors for HCC development in PBC patients and the first to demonstrate that the incidence of PBC-associated HCC is 4.13% in the Chinese population. Analysis indicated that high BMI and alcohol intake might be risk factors for HCC development. Male PBC patients are more likely to develop HCC than females, and PBC-associated HCC in male patients is more severe than in female patients, as indicated by their high levels of alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase/alkaline phosphatase/γ-glutamyl transpeptidase.

Applications

The authors suggest that physicians should pay close attention to patients with PBC-associated HCC and advise PBC patients to stop drinking and control body weight. Male PBC patients should be screened carefully for HCC because of its high incidence and severity.

Peer-review

The authors investigated the cases and controls from their hospital clinical database to explore the incidence and risk factors for PBC-associated HCC and offer some valuable conclusions.

Footnotes

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81470837, No. 81101589 and No. 81302593.

Ethics approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Beijing 302 Hospital Research Ethics Committee.

Informed consent: The Beijing 302 Hospital Research Ethics Committee waived the need for written informed consent from the participants due to the de-identified secondary data analyzed in this study.

Conflict-of-interest: All authors declare no conflict of any interest.

Data sharing: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: October 21, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Article in press: January 16, 2015

P- Reviewer: Chok Kenneth SH, Efe C, McNally RJQ, Toshikuni N S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Kaplan MM, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1261–1273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson H, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Card TR, Aithal GP, Logan R, West J. Influence of ursodeoxycholic acid on the mortality and malignancy associated with primary biliary cirrhosis: a population-based cohort study. Hepatology. 2007;46:1131–1137. doi: 10.1002/hep.21795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamagiwa S, Ichida T. Recurrence of primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis after liver transplantation in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2007;37 Suppl 3:S449–S454. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582–592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lööf L, Adami HO, Sparén P, Danielsson A, Eriksson LS, Hultcrantz R, Lindgren S, Olsson R, Prytz H, Ryden BO. Cancer risk in primary biliary cirrhosis: a population-based study from Sweden. Hepatology. 1994;20:101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones DE, Metcalf JV, Collier JD, Bassendine MF, James OF. Hepatocellular carcinoma in primary biliary cirrhosis and its impact on outcomes. Hepatology. 1997;26:1138–1142. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibuya A, Tanaka K, Miyakawa H, Shibata M, Takatori M, Sekiyama K, Hashimoto N, Amaki S, Komatsu T, Morizane T. Hepatocellular carcinoma and survival in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;35:1172–1178. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutsch M, Papatheodoridis GV, Tzakou A, Hadziyannis SJ. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and extrahepatic malignancies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:5–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f163ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakano T, Inoue K, Hirohara J, Arita S, Higuchi K, Omata M, Toda G. Long-term prognosis of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) in Japan and analysis of the factors of stage progression in asymptomatic PBC (a-PBC) Hepatol Res. 2002;22:250–260. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(01)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Terada R, Okamaoto R, Ikeda H, Makino Y, Kobashi H, Takaguchi K, Sakaguchi K, Shiratori Y. Persistent elevation of serum alanine aminotransferase levels leads to poor survival and hepatocellular carcinoma development in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1197–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Floreani A, Biagini MR, Chiaramonte M, Milani S, Surrenti C, Naccarato R. Incidence of hepatic and extra-hepatic malignancies in primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) Ital J Gastroenterol. 1993;25:473–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki A, Lymp J, Donlinger J, Mendes F, Angulo P, Lindor K. Clinical predictors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavazza A, Caballería L, Floreani A, Farinati F, Bruguera M, Caroli D, Parés A. Incidence, risk factors, and survival of hepatocellular carcinoma in primary biliary cirrhosis: comparative analysis from two centers. Hepatology. 2009;50:1162–1168. doi: 10.1002/hep.23095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silveira MG, Suzuki A, Lindor KD. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;48:1149–1156. doi: 10.1002/hep.22458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H, Liu Y, Wang L, Xu D, Lin B, Zhong R, Gong S, Podda M, Invernizzi P. Prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis in adults referring hospital for annual health check-up in Southern China. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Han Q, Chen H, Wang K, Shan GL, Kong F, Yang YJ, Li YZ, Zhang X, Dong F, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with UDCA-resistant primary biliary cirrhosis. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:2482–2489. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang DK, Chen M, Liu Y, Wang RF, Liu LP, Li M. Acoustic radiation force impulse elastography for non-invasive assessment of disease stage in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: A preliminary study. Clin Radiol. 2014;69:836–840. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Li J, Liu H, Li Y, Fu J, Sun Y, Xu R, Lin H, Wang S, Lv S, et al. Pilot study of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell transfusion in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28 Suppl 1:85–92. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qian C, Jiang T, Zhang W, Ren C, Wang Q, Qin Q, Chen J, Deng A, Zhong R. Increased IL-23 and IL-17 expression by peripheral blood cells of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Cytokine. 2013;64:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu J, Zhang Z, Zhou L, Qi Z, Xing S, Lv J, Shi J, Fu B, Liu Z, Zhang JY, et al. Impairment of CD4+ cytotoxic T cells predicts poor survival and high recurrence rates in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;58:139–149. doi: 10.1002/hep.26054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z, Zhang S, Zou Z, Shi J, Zhao J, Fan R, Qin E, Li B, Li Z, Xu X, et al. Hypercytolytic activity of hepatic natural killer cells correlates with liver injury in chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatology. 2011;53:73–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.23977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang JY, Zhang Z, Lin F, Zou ZS, Xu RN, Jin L, Fu JL, Shi F, Shi M, Wang HF, et al. Interleukin-17-producing CD4(+) T cells increase with severity of liver damage in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;51:81–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.23273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loomba R, Yang HI, Su J, Brenner D, Barrett-Connor E, Iloeje U, Chen CJ. Synergism between obesity and alcohol in increasing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:333–342. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorrentino P, Terracciano L, D’Angelo S, Ferbo U, Bracigliano A, Tarantino L, Perrella A, Perrella O, De Chiara G, Panico L, et al. Oxidative stress and steatosis are cofactors of liver injury in primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1053–1062. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harada K, Hirohara J, Ueno Y, Nakano T, Kakuda Y, Tsubouchi H, Ichida T, Nakanuma Y. Incidence of and risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in primary biliary cirrhosis: national data from Japan. Hepatology. 2013;57:1942–1949. doi: 10.1002/hep.26176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngu JH, Gearry RB, Frampton CM, Stedman CA. Mortality and the risk of malignancy in autoimmune liver diseases: a population-based study in Canterbury, New Zealand. Hepatology. 2012;55:522–529. doi: 10.1002/hep.24743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozaslan E, Efe C, Heurgué-Berlot A, Kav T, Masi C, Purnak T, Muratori L, Ustündag Y, Bresson-Hadni S, Thiéfin G, et al. Factors associated with response to therapy and outcome of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis with features of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:863–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang Y, Yang Z, Zhong R. Primary biliary cirrhosis and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2012;56:1409–1417. doi: 10.1002/hep.25788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howel D, Metcalf JV, Gray J, Newman WL, Jones DE, James OF. Cancer risk in primary biliary cirrhosis: a study in northern England. Gut. 1999;45:756–760. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.5.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caballería L, Parés A, Castells A, Ginés A, Bru C, Rodés J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in primary biliary cirrhosis: similar incidence to that in hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1160–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angulo P, Batts KP, Therneau TM, Jorgensen RA, Dickson ER, Lindor KD. Long-term ursodeoxycholic acid delays histological progression in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1999;29:644–647. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li ZM, Zhao DT, Feng X, Sun LM, Zhang HP, Zhao Y, Yan HP. The characteristic of auto-antibodies of hepatocellular carcinoma in primary biliary cirrhosis. Zhongguo Shiyan Zhengduanxue. 2014;1:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su CW, Hung HH, Huo TI, Huang YH, Li CP, Lin HC, Lee PC, Lee SD, Wu JC. Natural history and prognostic factors of primary biliary cirrhosis in Taiwan: a follow-up study up to 18 years. Liver Int. 2008;28:1305–1313. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeh SH, Chen PJ. Gender disparity of hepatocellular carcinoma: the roles of sex hormones. Oncology. 2010;78 Suppl 1:172–179. doi: 10.1159/000315247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, Elsharkawy AM, Karin M. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317:121–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeong SY, Park SJ, Lee SJ, Park HJ, Kim HJ. Loss of Y chromosome in the malignant peripheral nerve sheet tumor of a patient with Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:804–808. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.5.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lleo A, Oertelt-Prigione S, Bianchi I, Caliari L, Finelli P, Miozzo M, Lazzari R, Floreani A, Donato F, Colombo M, et al. Y chromosome loss in male patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong AK, Fang B, Zhang L, Guo X, Lee S, Schreck R. Loss of the Y chromosome: an age-related or clonal phenomenon in acute myelogenous leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1329–1332. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-1329-LOTYCA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Findor J, He XS, Sord J, Terg R, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:220–225. doi: 10.1016/s1568-9972(02)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bugianesi E, Vanni E, Marchesini G. NASH and the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2007;7:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s11892-007-0029-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purohit V, Brenner DA. Mechanisms of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis: a summary of the Ron Thurman Symposium. Hepatology. 2006;43:872–878. doi: 10.1002/hep.21107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Híndi M, Levy C, Couto CA, Bejarano P, Mendes F. Primary biliary cirrhosis is more severe in overweight patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:e28–e32. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318261e659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dyson J, Jaques B, Chattopadyhay D, Lochan R, Graham J, Das D, Aslam T, Patanwala I, Gaggar S, Cole M, et al. Hepatocellular cancer: the impact of obesity, type 2 diabetes and a multidisciplinary team. J Hepatol. 2014;60:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hart CL, Morrison DS, Batty GD, Mitchell RJ, Davey Smith G. Effect of body mass index and alcohol consumption on liver disease: analysis of data from two prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2010;340:c1240. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.List S, Gluud C. A meta-analysis of HLA-antigen prevalences in alcoholics and alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29:757–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]