Graphical abstract

Keywords: Chlorophyll, Phyllobilin, Collision-induced dissociation, Ionic fragmentation, Structure elucidation, Catabolomics

Highlights

-

•

Collision-induced dissociation of cationic and anionic species of a tetrapyrrolic chlorophyll catabolite.

-

•

Diagnostic fragmentations are discussed as well as possible mechanisms presented.

-

•

An exceptional decarboxylation reaction involving a deprotonated carboxylic acid and a ketene function that results from the loss of methanol.

Abstract

The hyphenation of high performance chromatography with modern mass spectrometric techniques providing high-resolution data as well as structural information from MS/MS experiments has become a versatile tool for rapid natural product identification and characterization. A recent application of this methodology concerned the investigation of the annually occurring degradation of green plant pigments. Since the first structural elucidation of a breakdown product in the early 1990s, a number of similarly structured, tetrapyrrolic catabolites have been discovered with the help of chromatographic, spectroscopic and spectrometric methods. A prerequisite for a satisfactory, manually operated or database supported analysis of mass spectrometric fragmentation patterns is a deeper knowledge of the underlying gas phase chemistry. Still, a thorough investigation of the common fragmentation behavior of these ubiquitous, naturally occurring chlorophyll breakdown products is lacking. This study closes the gap and gives a comprehensive overview of collision-induced fragmentation reactions of a tetrapyrrolic nonfluorescent chlorophyll catabolite, which is intended to serve as a model compound for the substance class of phyllobilins.

1. Introduction

Each year, the world-wide degradation of chlorophyll (Chl) in higher plants furnishes an amount of about 1000 million tons of linear tetrapyrroles, called phyllobilins [1], which are colorless and have completely evaded their detection until about 23 years ago [2,3]. From the very beginnings of these studies, mass spectrometry (MS) [4] has played a key role: it has contributed to the discovery and identification of a first colorless Chl-catabolite, a ‘nonfluorescent’ Chl-catabolite (NCC) [2]. Indeed, NCCs typically accumulate in senescent leaves as the ‘final’ tetrapyrrolic stage of Chl-breakdown (see Scheme 1) [5]. In particular the ‘soft’ ionization methods fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry (FAB-MS) [6], electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) [7] and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) [8,9] have paved the way to direct analysis of complex mixtures of natural products and also proved to be essential in the strongly developing field of Chl-breakdown: MS has provided effective tools not only for the structural analysis of the nonvolatile and complex NCCs (as well as of other bilin-type Chl-catabolites) [10,11], but also for the clarification of reaction mechanisms of key Chl-breakdown enzymes by analysis of the isotope composition of catabolites [12].

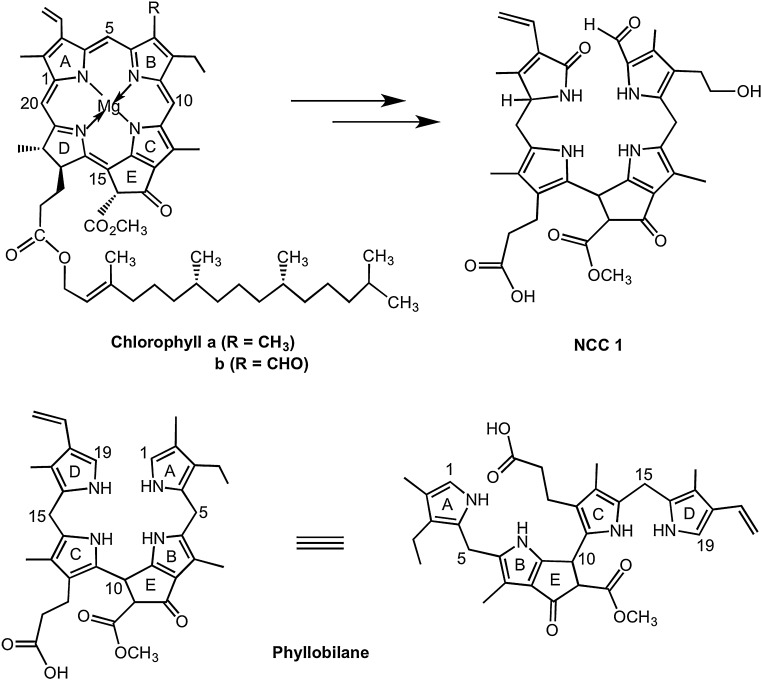

Scheme 1.

Top: NCCs are products of the degradation of chlorophylls a and b in higher plants. Bottom: General chemical formulas and core structures of a phyllobilane including labels for major structural elements and atom numbering used here. Note the different enumeration and labeling of the pyrrolic rings in chlorophyll vs. phyllobilane.

Nowadays, modern MS-techniques, when combined with efficient separation methods, have become versatile means for the detection and provisional ex-vivo identification of Chl-catabolites in plant extracts [13], as well as in-vivo, e.g. in intact senescent leaves [14]. Typically, the ubiquitous NCCs represent notable components in both types of these natural sources [15]. Interestingly, an exemplary model study of a representative NCC by MS still is lacking. Here, electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry [7] was applied in an MS-analysis of the abundant NCC 1 [15], in order to provide insights helpful for analysis of related Chl-catabolites in plant extracts. The colorless Chl-catabolite 1 is a well-characterized NCC that was originally isolated from de-greened leaves of the deciduous tree Cercidiphyllum japonicum, and thus is also called Cj-NCC-1 [16,17]. The NCC 1 is also present in various ripe fruit, e.g. in apples and pears (where 1 figures as Ms-NCC-2 or as Pc-NCC-2, resp. [18]). The NCC 1 was classified as an excellent antioxidant, thus raising further interest in a versatile procedure for the analysis of NCCs, such as 1.

1.1. The role of mass spectrometry in structure elucidation of chlorophyll degradation products

Advances in MS, such as the development of exact mass measurement, tandem mass spectrometry, soft ionization methods, as well as the improvement of hyphenated techniques, especially liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS), have provided a basis for rapid screening of different types of plant material. Full structure elucidation still may require additional information from heteronuclear 2D-NMR spectroscopy [19], and rely on further input from crystallography [20].

In order to tap the full potential of MS for structure elucidation of Chl-catabolites, not only the delineation of their molecular formula from high resolution MS is a prerequisite, but the understanding of common fragmentation behavior of these linear tetrapyrroles in the gas phase is also very characteristic. In this study we therefore present a comprehensive analysis of the (pseudo)molecular ions of the Chl-catabolite 1, as well as basic mechanistic considerations of the collision-induced dissociation (CID) reactions observed for the (pseudo)molecular ions of this NCC. To delineate basic mass spectrometric patterns of 1, we used electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry [7].

2. Experimental

A stock solution of the NCC 1 was prepared by dissolving 0.005 g of 1 [16,17,21] in 1 ml of 4 mM methanolic ammonium acetate (NH4OAc; c = 7.8 mM). Prior to infusion into the ESI-MS the stock solution was diluted 1:28 (v/v) using 4 mM methanolic NH4OAc. A Thermo-Finnigan LCQ quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with electrospray ionization (ESI) source was used for MS and MS/MS experiments. High-resolution data were obtained using a Bruker Apex Ultra 7 Tesla Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Ions of a given m/z were selected in a linear quadrupole prior to collision-induced dissociation (CID) in a linear hexapole ion trap floated with argon as collision gas. The collision energy is defined as the bias potential difference between the second ion funnel and the collision cell's hexapole. Post-source decay (PSD) experiments were performed on a modified Bruker Ultraflex mass spectrometer equipped with a Smartbeam Nd:YAG laser. For PSD experiments the pulse width of the precursor ion selector was set to 120–150 ns corresponding to a selection window of approx. 5–7 Da. At a constant acceleration voltage of 25 kV the high voltage at the reflectron was stepwise reduced from 26.4 kV to 21.21 kV, 16.86 kV, 13.45 kV, 10.72 kV and 8.54 kV. In-house developed software was used to calibrate and merge the obtained PSD spectra. All mass spectrometric data were processed using the open source tool mMass [22].

3. Results and discussion

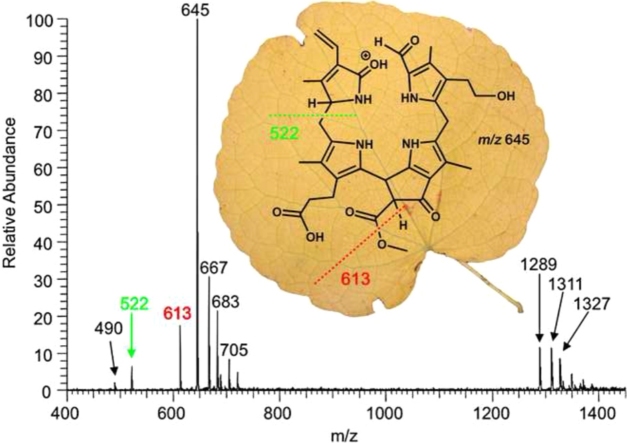

Methanolic solutions of 1 (10 ppm) were used for infusion ESI mass spectrometric analyses. A typical positive ion-mode full ESI mass spectrum of 1 with the protonated pseudo-molecular ion [M + H]+ as the base peak is depicted in Fig. 1A. NH4OAc (4 mM) had to be added to the spray solvent in order to obtain useful signal intensities of the [M + H]+ ion at m/z 645 and to decrease the signal intensity of the sodiated and potassiated ions [M + X]+ (X = Na, K) at m/z 667 or m/z 683, resp., or [M–H + 2X]+ (X = Na, K) at m/z 689 or m/z 721, resp., or the [M–H + Na + K]+-ion at m/z 705. These latter ions were observed to be formed efficiently due to the presence of a free propionic acid side chain at position 12 of ring C (see Scheme 1 and inset of Fig. 1A). The analogous observation also applied to the formation of dimeric species, as the protonated, sodiated and potassiated dimers ([2M + H]+ at m/z 1289, [2M + Na]+ at m/z 1311, [2M + K]+ at m/z 1327) were clearly seen in the spectra (for a more detailed classification see Supporting information Figs. S1 and S2). The [M + H]+-ions of the linear tetrapyrrolic Chl-catabolite 1 exhibited immediate in-source fragmentation. As can also be seen in Fig. 1A, the fragment ions at m/z 613, m/z 522 and m/z 490 readily appeared in the full MS spectrum without any further activation in the nozzle-skimmer region.

Fig. 1.

(A) ESI mass spectrum in the positive ion-mode of the NCC 1 and proposed chemical structure of the [M + H]+ of 1 (R1 = H, Na, K). The signal at m/z 645 corresponds to the protonated molecular ion [M + H]+, the products of an in-source fragmentation are readily visible at m/z 613, 522 and 490 (NCC 1 was dissolved in 4 mM methanolic NH4OAc). Dashed lines signify formal fragmentation modes. The region of the molecular ions (m/z 480 to m/z 740) is magnified in (B), the region of the dimeric molecular ions (m/z 1270 to m/z 1450) is magnified in (C).

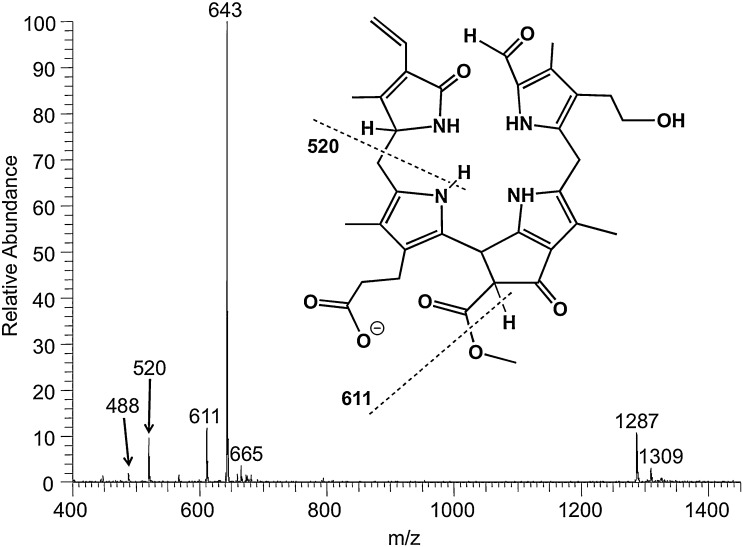

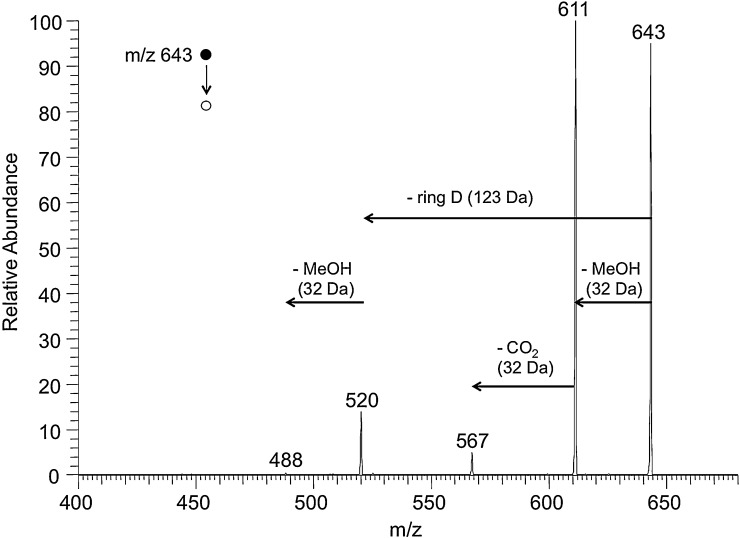

A free propionic acid group is a common feature of most naturally occurring Chl-catabolites and thus predestines NCCs to be also detectable in the negative ion mode (Fig. 2). The base peak of the spectrum was the deprotonated molecular ion [M–H]− at m/z 643. As already shown for the positive ion-mode, the formation of dimers ([2M–H]− at m/z 1287 and ([2M–2H + Na]− at m/z 1309) as well as in-source fragmentation of the [M–H]− were observed in the negative ion-mode too. The three in-source fragment ions (m/z 613, m/z 522, m/z 490 in the positive mode and m/z 611, m/z 520, m/z 488 in the negative mode) are due to loss of MeOH (−32), of ring D (−123), or of both (−155). This type of heterolytic fragmentation pattern is generally observed when Chl-degradation products are analyzed by ‘soft’ ionization MS methods, and thus is considered to be highly diagnostic (see also Sections 3.1 and 3.3). In the negative ion-mode the formation of dianions was not observed for NCC 1.

Fig. 2.

ESI mass spectrum in the negative ion-mode of the NCC 1, and proposed chemical structure of the [M–H]−-ion of 1. The signal at m/z 643 corresponds to deprotonated molecular ion [M–H]−; signals at m/z 611, 520 and 488 correspond to in-source fragments (NCC 1 was dissolved in 4 mM methanolic NH4OAc). Dashed lines signify formal fragmentation modes.

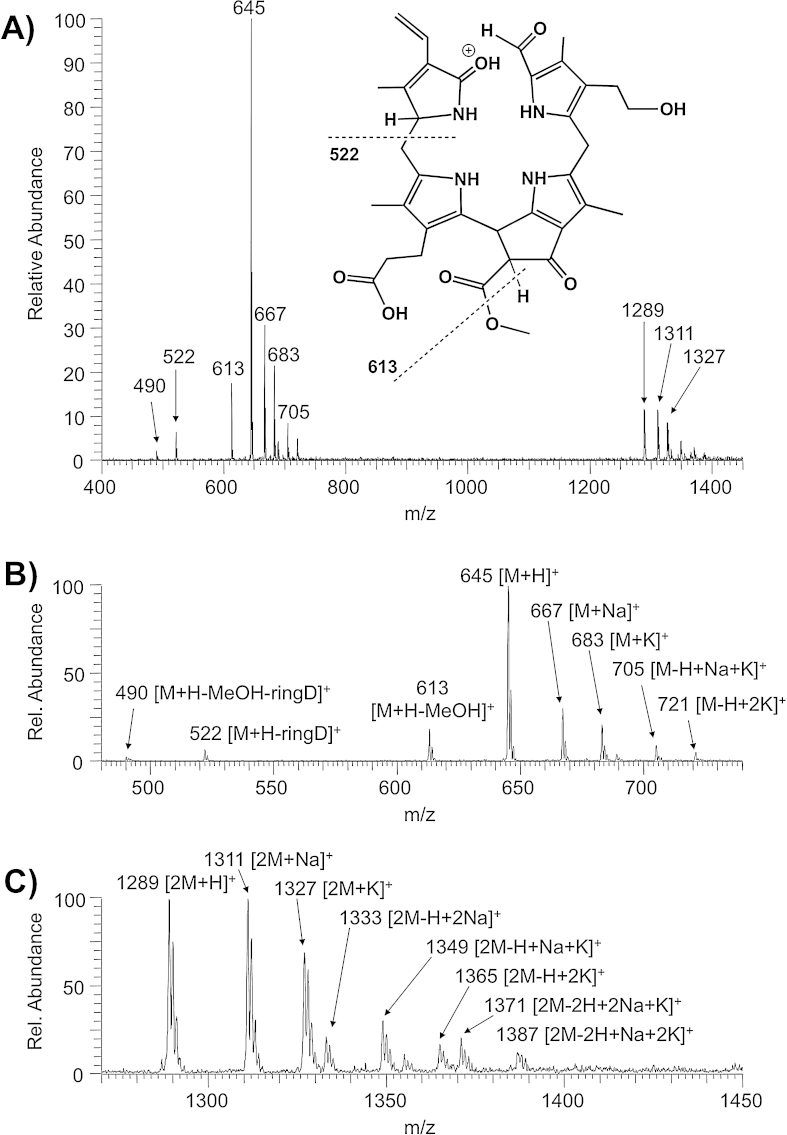

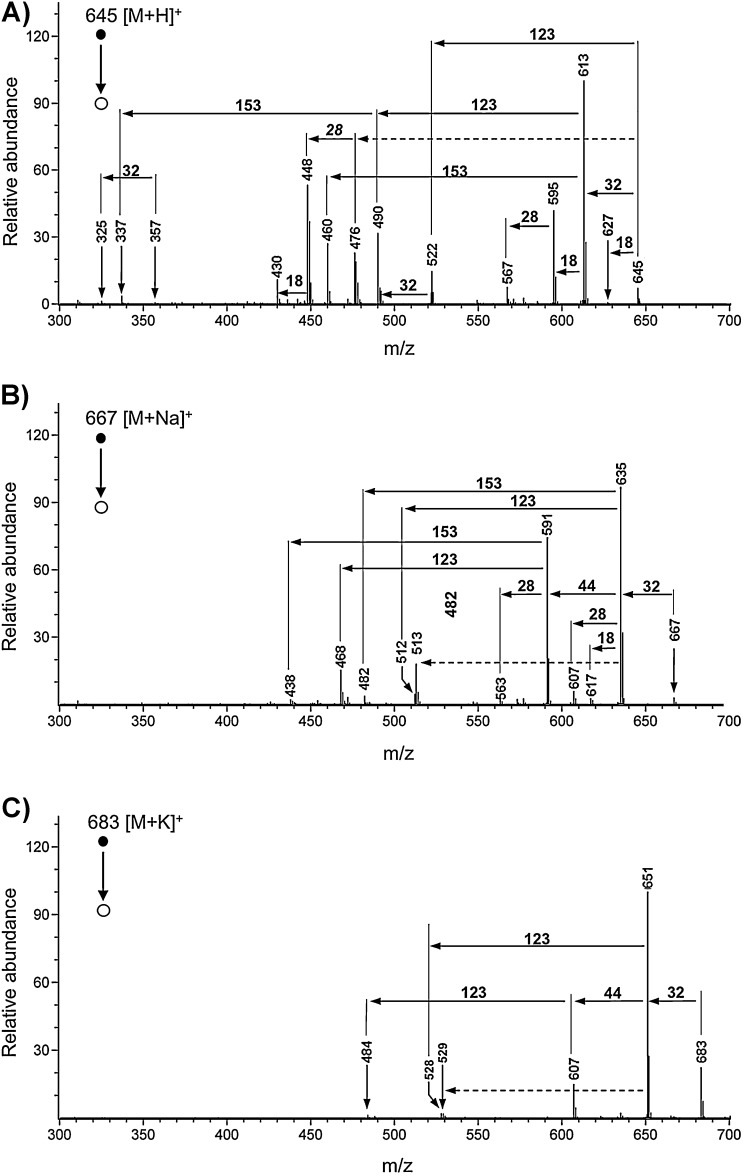

The fragmentation behavior of the isolated pseudo-molecular ions in the gas phase was studied in the positive (Fig. 3) as well as negative ion-mode (Fig. 4). Collision-induced dissociation (CID) MS/MS experiments were carried out on a Thermo-Finnigan LCQ quadrupole ion trap, applying normalized collision energy of 25% to the isolated ions. Dimeric ions showed complete dissociation of the dimer at normalized collision energies higher than 15%. For the determination of the elemental composition of parent as well as fragment ions high-resolution MS/MS was performed on a Bruker FT-ICR instrument. The [M + H]+, [M + Na]+ and [M + K]+ ions were selected as precursors and fragmented in the linear hexapole ion trap floated with argon. The collision energy was kept at the same level (20 V) for all three types of pseudo-molecular ions. Although it is possible that Na+ and K+ are also fragment ions, high resolution spectra were usually recorded in the mass range from m/z 200 to m/z 1500. As can be seen in Fig. 3, the number of fragment ions was decreasing depending on the charging cation (H+ > Na+ > K+), hence most structural information is provided by the MS/MS analysis of the [M + H]+ ion (see Fig. 3A–C). As a rule, a mass spectrum of a tetrapyrrolic NCC indicates four important types of fragmentation reactions, which will be discussed in detail: (i) the loss of methanol in case of a methoxycarbonyl functionality at the 82-position, (ii) the loss of water and carbon monoxide, (iii) cleavages at the so-called meso-positions C5, C10 and C15, and (iv) decarboxylation reactions. All losses of neutral fragments could unambiguously be identified with the help of the high-resolution data of the remaining cation (see Supporting information, Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

High-resolution MS/MS experiments (CID) of the isolated pseudo-molecular ions of 1: (A) [M + H]+ (m/z 645), (B) [M + Na]+ (m/z 667) and (C) [M + K]+ (m/z 683). Collision energy level at the quadrupole of the Bruker FT-ICR instrument was kept constant at 20 V (see also Supporting information Fig. S3).

Fig. 4.

MS/MS experiments (CID) of the isolated deprotonated pseudo-molecular ion [M–H]− (m/z 643) of 1.

3.1. MeOH loss from the methoxycarbonyl functionality at the 82-position

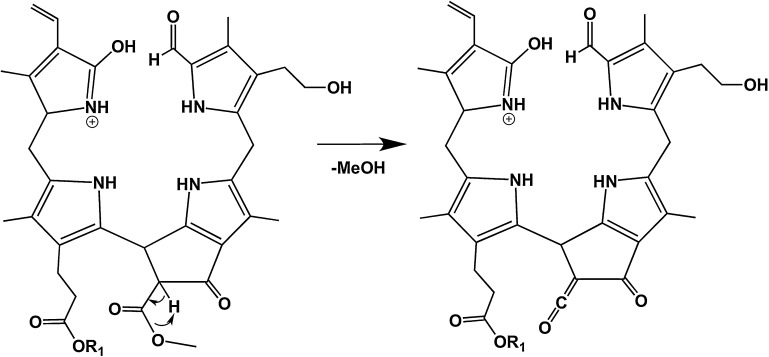

As can be seen in Figs. 3 and 4, the pseudo-molecular ions in positive as well as negative ion mode efficiently lose MeOH upon CID, i.e. the fragment ions [M + X-MeOH]+ (X = H, Na or K) or [M–H–MeOH]− were found to be the base peaks in all of the MS/MS spectra. Interestingly, loss of MeOH could also be observed in the negative ion-mode (Fig. 4) and in case of [M–H + 2X]+ ions (X = Na or K; e.g. the “potassiated potassium salt” of 1; data not shown). Hence the intra-molecular source of a proton, needed to form the neutral MeOH fragment, is an acidified position of the tetrapyrrole, e.g. the 82 position of the β-keto ester functionality at ring E.

The suggested mechanism is delineated for the [M + H]+ ion in Scheme 2 and gives rise to the formation of a ketene functionality. This is in accordance with a mechanism proposed for CH3OH loss from chlorophyll derivatives using fast atom bombardment (FAB) mass spectrometry [23]. The loss of MeOH is a characteristic attribute for many structurally characterized, naturally occurring chlorophyll degradation products [1], having the methyl ester functionality of the original chlorophylls. However, in some higher plants (e.g. in the Brassicaceae Arabidopsis thaliana [11,24] or oilseed rape [10,25]) this methyl ester function is hydrolyzed in the course of chlorophyll breakdown by a methyl esterase [26], giving rise to a β-keto acid functionality, which decarboxylates readily (see also Section 3.4).

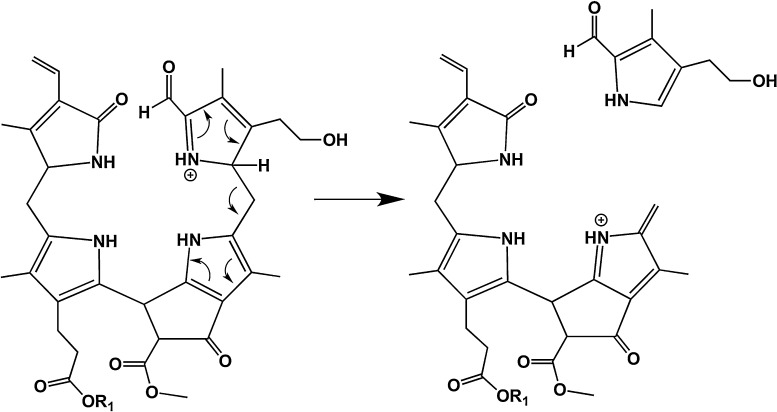

Scheme 2.

Diagnostic fragmentations of (+)-ions of NCC 1 (R1 = H+, Na+ or K+). Loss of MeOH.

3.2. Loss of water and carbon monoxide

As can be seen in Fig. 3, in particular the molecular ions [M + H]+ and [M + Na]+ showed several prominent losses of water (−18 Da) and/or carbon monoxide (−28 Da). The origin of these neutral losses presumably is the free propionic acid side chain at the 12 position. Due to its ubiquitous presence in naturally occurring NCCs, the cleavages of H2O or CO may be considered important but not diagnostic. Although at very low abundances, a direct loss of water can also be observed from the molecular ions (e.g. m/z 627 in Fig. 3A). This is not the case for the losses of carbon monoxide, which were only found together with losses of water, methanol (see Section 3.1) or cleavages of pyrrolic units (see Section 3.3).

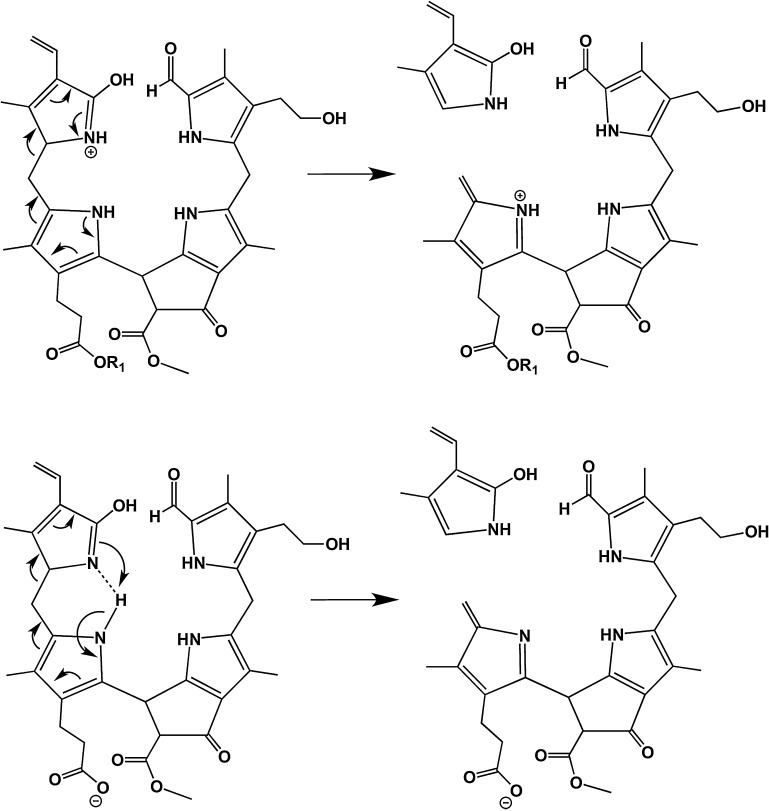

3.3. Cleavage at meso-positions

In the course of Chl-breakdown, the chlorin ring of chlorophyll a is opened oxygenolytically at the “northern” meso-position [12], paving the way to the typical formyl-oxobilin-type structures of the linear tetrapyrroles (or phyllobilins) derived from Chl [1]. This is depicted e.g. by the formula of the NCC 1 in Scheme 1. Depending on the type of the higher plant, NCCs are often further modified at the two remaining rings next to the cleavage site, i.e. rings A and D [15]. Mass spectrometric loss of either the ring A or/and of the ring D moieties therefore provide important information with respect to the chemical constitution of an NCC. In comparison to its precursor, chlorophyll a, the NCC 1 has no further peripheral modification on ring D, but it is hydroxylated at the 32-position of ring A. Ring D of the NCC 1 is a 1,2-dihydropyrrole-5-one moiety, while rings A, B and C are substituted pyrrole units.

All MS/MS experiments in the positive as well as in the negative ion-mode showed loss of ring D (−123 Da; (C15–C16)-bond was cleaved) as a very favored fragmentation mode, either of the pseudo-molecular ion directly (Fig. 3A and Fig. 4), or in a row with the loss MeOH and CO2 (Fig. 3A–C). It is assumed that protonation of the carbonyl group at ring D (the 1,2-dihydropyrrol-5-one) initiates the loss of a neutral (aromatic), 2-hydroxy-pyrrol unit (Scheme 3; top), while a positive charge remains at the other fragment, where it gains stabilization from interaction with the electron-rich ring C hetero-cycle. Due to the fact that the loss a neutral 2-hydroxy-pyrrol unit (−123 Da) is also observed in the negative ion-mode, a different mechanism is supposed to contribute to the loss of ring D. This mode of cleavage makes it likely that the nitrogen bound hydrogen from pyrrolic ring C is a direct or indirect intramolecular proton source for ring D. As a consequence the C15–C16 bond can be cleaved heterolytically while no charge remains on either part (see Scheme 3; bottom). This also would explain why ring D can be cleaved after the loss of ring A and vice versa (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, in case of [M + Na]+ and [M + K]+ (Fig. 3B and C) the loss of methanol comes first and the loss of ring D is not occurring directly from the sodiated and potassiated molecules. We hypothesize that the sodium or potassium ions are stabilized by complexation involving all oxygens of the carboxlic acid as well as the β-keto ester on the ring C and ring E, respectively. This special arrangement might favor the neutral loss of methanol over any other reaction channel. In contrast, signals from loss of ring A (−153 Da; (C4–C5)-bond was cleaved) were of comparably low intensity (Fig. 3A andB). As shown in Scheme 4, in this fragmentation process, an initial protonation is suggested at the α-position of ring A. Although a neutral, stable pyrrole unit is lost and the (+)-charge associated with the ring B moiety is delocalized and stabilized electronically, the initial protonation disrupts the aromaticity of the pyrrole unit of ring A and is, therefore, an energetically disfavored step.

Scheme 3.

Diagnostic fragmentations of (+)-ions of NCC 1 (top; R1 = H+, Na+ or K+) and of (−)-ions of NCC 1 (bottom): Loss of ring D.

Scheme 4.

Diagnostic fragmentations of (+)-ions of NCC 1 (R1 = H, Na or K): Loss of ring A; a similar mechanism could be relevant for the cleavage between the pyrrole rings C and E.

Cleavage of the “southern” (C10–C11)-bond between rings C and E of 1 is of considerable interest also, since the fragment ions containing rings A, B and E would assist in the characterization of the ‘left’ and ‘right’ halves of NCC molecules. However, in spite of the pyrrolic nature of ring C, CID gave signals with very low abundance only, that related to a dissociation of the (C10–C11)-bond of 1. Such a fragmentation could occur via protonation of the pyrrolic α-position (i.e. at C11) of ring C. As can be seen in Fig. 3A, signals at m/z 357 and m/z 325 corresponding to the fragment ions [M + H-(rings C + D)]+ and [M + H–MeOH-(rings C + D)]+ are low-abundant and barely seen (these fragment ions are marked with an arrow in Fig. 3A). However, these important fragments can be detected at reasonably higher signal intensities when matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization post-source decay (MALDI-PSD) [27] is used to study metastable fragmentations of the Chl-catabolites (see Supporting information Fig. S4). It would help the clarification of the nature of the propionic acid function at ring C, which has been detected either in a free acid form, or as a glycosyl-ester.

As a rule, cleavages at the meso positions observed in ESI mass spectra of 1 can be rationalized as charge-induced fragmentations of even-electron ionic species yielding a product ion being capable to stabilize the remaining charge and a neutral which is lost. However, as can be seen in Fig. 3, signals of some fragment ions showed exceptional isotope patterns, which were not related to the natural abundance of the isotopes (m/z 476 and m/z 448 in Fig. 3A and Fig. S5 in the Supporting information; m/z 513 in Fig. 3B; m/z 529 in Fig. 3C). According to the high-resolution data, all these fragment ions unambiguously corresponded to a loss of ring D. Hence, a loss of ring D together with the methylene carbon C5 as a neutral radical (C8H10N1O1.; 136 Da; dashed arrow in Fig. 3A) corresponds to the isotope pattern observed in Fig. 3A (more detailed in Supporting Fig. S5), which was found to be exceptionally abundant at m/z 477 (i.e. m/z 613–136 Da) as well as at m/z 449 (i.e. m/z 613 – 136 Da – CO). Furthermore, the signals at m/z 513 in Fig. 3B and m/z 529 in Fig. 3C must be due to the loss of ring D as a neutral radical (C7H8N1O1; 122 Da; dashed arrows in Fig. 3B and C). These fragmentations are remarkable because they disobey the even-electron rule saying that even electron ions will not usually lose a radical to form an odd-electron cation [28,29]. But the structural features of the rings C and D are able to stabilize a radical cationic product ion and a neutral radical suggesting radical fragmentation mechanisms to be most likely in these cases [29,30].

3.4. Decarboxylation reactions

Typical FAB mass spectra [10,25] or ESI mass spectra [24] of polar NCCs, which carried a carboxylic acid function at ring E, showed a strong signal at (M-44 + X)+, with X = H, Na or K, indicating an efficient loss of carbon dioxide. This observation was rationalized by the presence of a reactive β-keto acid grouping in these NCCs. Surprisingly, a decarboxylation reaction in the gas phase was also observed in the MS of the NCC 1, in which a β-keto ester functionality is present. Remarkably, in the MS spectra of sodiated or potassiated 1 (Fig. 3B and C) as well as of deprotonated 1 (Fig. 4), loss of carbon dioxide was observed only from the daughter ions [M + X-CH3OH]+ with X = Na, K or [M–H–CH3OH)]− that resulted from loss of MeOH, giving a ketene group at C82. Thus, two boundary conditions need to be met for the remarkable decarboxylation to be relevant: a deprotonated carboxylic acid functionality (with sodium or potassium counter ions in the positive ion-mode) and the ketene function appear to be required. These findings suggest further activation steps to be crucial for the rapid loss of CO2. Note, the positively charged pseudo-molecular ions [M + X]+ are protonated sodium or potassium complexes of 1. In the decarboxylation the electrophilic ketene group may be attacked by the nucleophilic carboxylate. This leads to the enolate of a cyclic anhydride function (see Scheme 5; delineated for the positive ion-mode). The latter may undergo closure to a strained α-lactone ring, which is activated for an ensuing decarboxylative ring fragmentation. This hypothetical path would involve loss of the 83 carbon and one oxygen atom of the former ester function, and not of the propionate itself.

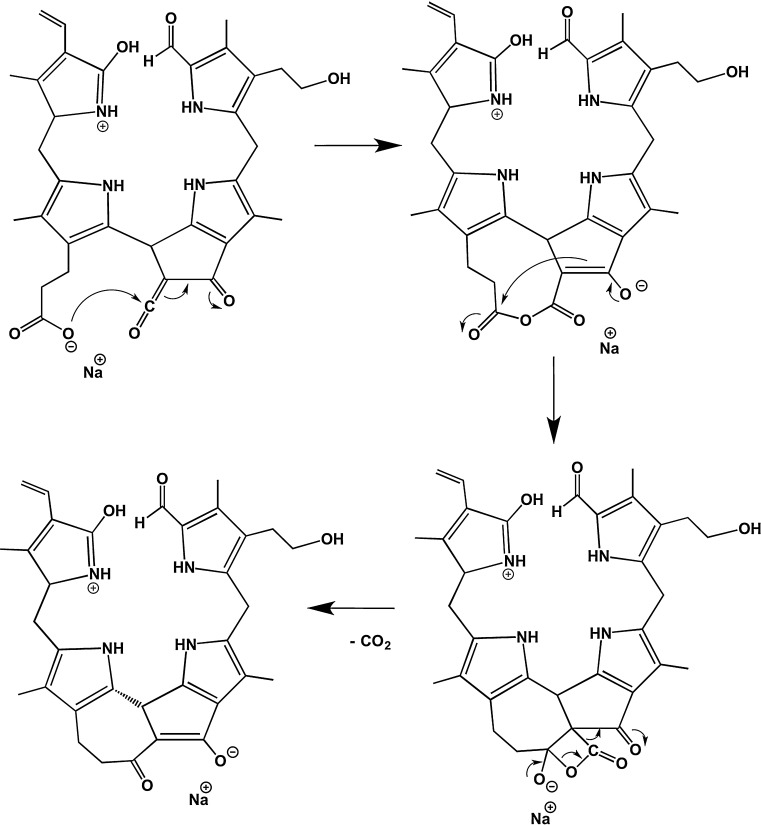

Scheme 5.

Diagnostic fragmentations of sodiated (+)-ions of NCC 1: Loss of CO2 and a proposed mechanism involving the ketene functionality from the 82-methoxycarbonyl group (see Section 3.1).

4. Conclusion

Non-fluorescent chlorophyll catabolites (NCCs) are bilin-type degradation products of chlorophyll a. They are remarkable and ubiquitous antioxidants, which accumulate in cells of senescing leaves and of ripening fruit. NCCs are amphiphilic compounds with a variety of polar functionalities at the periphery of their tetrapyrrolic core. These functional groups provide good solubility in polar solvents, and allow for ESI mass spectrometric analyses in positive as well as negative ion-mode. Three isolated pyrrole moieties and a 1,2-dihydropyrrol-5-one unit are connected by three saturated meso-positions, which are ‘predetermined’ sites for effective cleavage observable in mass spectra. Careful exhaustive examination of suitable mass spectra of NCCs not only furnishes their molecular formula, but, in addition, it appears to be an excellent means for the determination of the molecular constitution of such Chl-catabolites. The mass spectrometric finger print of NCCs may serve further purposes, such as of ex-vivo or in-vivo ‘catabolomics’ of plant samples.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Kathrin Breuker for technical assistance (FT-ICR MS). Financial support by the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF, projects L-457 and I-563 to B. K.) and by the Bundesministerium fur Wissenschaft und Forschung (BM.W_F, Project SPA/04-140/Indian Summer in Tyrol to T. M.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Thomas Müller, Email: thomas.mueller@uibk.ac.at.

Bernhard Kräutler, Email: bernhard.kraeutler@uibk.ac.at.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kräutler B., Hörtensteiner S. Chlorophyll breakdown—chemistry biochemistry and biology. In: Ferreira G.C., Kadish K.M., Smith K.M., Guilard R., editors. The Porphyrin Science Handbook. World Scientific Publishing; USA: 2013. pp. 117–185. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kräutler B., Jaun B., Bortlik K., Schellenberg M., Matile P. On the Enigma of chlorophyll degradation—the constitution of a secoporphinoid catabolite. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1991;30:1315–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kräutler B., Matile P. Solving the riddle of chlorophyll breakdown. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuo T., Caprioli R.M., Gross M.L., Seyama Y. John Wiley & Sons; 1994. Biological Mass Spectrometry. Present and Future. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hörtensteiner S., Kräutler B. Chlorophyll breakdown in higher plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1807:977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber M., Bordoli R.S., Elliott G.J., Sedgwick R.D., Tyler A.N. Fast atom bombardment mass-spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1982;54:A645–A650. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200090506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenn J.B., Mann M., Meng C.K., Wong S.F., Whitehouse C.M. Electrospray ionization for mass-spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science. 1989;246:64–71. doi: 10.1126/science.2675315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karas M., Bachmann D., Bahr U., Hillenkamp F. Matrix-assisted ultraviolet-laser desorption of nonvolatile compounds. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 1987;78:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karas M., Hillenkamp F. Laser desorption ionization of proteins with molecular masses exceeding 10000 Daltons. Anal. Chem. 1988;60:2299–2301. doi: 10.1021/ac00171a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mühlecker W., Kräutler B. Breakdown of chlorophyll: constitution of nonfluorescing chlorophyll-catabolites from senescent cotyledons of the dicot rape. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1996;34:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pružinska A., Tanner G., Aubry S., Anders I., Moser S., Müller T., Ongania K.-H., Kräutler B., Youn J.-Y., Liljegren S.J., Hörtensteiner S. Chlorophyll breakdown in senescent Arabidopsis leaves. Characterization of chlorophyll catabolites and of chlorophyll catabolic enzymes involved in the degreening reaction. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:52–63. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.065870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hörtensteiner S., Wüthrich K.L., Matile P., Ongania K.H., Kräutler B. The key step in chlorophyll breakdown in higher plants—cleavage of pheophorbide a macrocycle by a monooxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15335–15339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moser S., Müller T., Ebert M.-O., Jockusch S., Turro N.J., Kräutler B. Blue luminescence of ripening bananas. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8954–8957. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller T., Oradu S., Ifa D.R., Cooks R.G., Kräutler B. Direct plant tissue analysis and imprint imaging by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:5754–5761. doi: 10.1021/ac201123t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moser S., Müller T., Oberhuber M., Kräutler B. Chlorophyll catabolites—chemical and structural footprints of a fascinating biological phenomenon. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009:21–31. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200800804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curty C., Engel N. Chlorophyll catabolism. 9. Detection, isolation and structure elucidation of a chlorophyll a catabolite from autumnal senescent leaves of Cercidiphyllum japonicum. Phytochemistry. 1996;42:1531–1536. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberhuber M., Berghold J., Breuker K., Hörtensteiner S., Kräutler B. Breakdown of chlorophyll: a nonenzymatic reaction accounts for the formation of the colorless ‘nonfluorescent’ chlorophyll catabolites. PNAS. 2003;100:6910–6915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232207100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Müller T., Ulrich M., Ongania K.-H., Kräutler B. Colourless tetrapyrrolic chlorophyll catabolites found in ripening fruit are effective antioxidants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:8699–8702. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst R.R., Bodenhausen G., Wokaun A. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1987. Principles of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance in One & Two Dimensions. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engel N., Gossauer A., Gruber K., Kratky C. Chlorophyll catabolism 4. X-ray molecular-structure of a red bilin derivative from Chlorella protothecoides. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1993;76:2236–2238. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulrich M., Moser S., Müller T., Kräutler B. How the colourless “nonfluorescent” chlorophyll catabolites rust. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:2330–2334. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strohalm M., Kavan D., Novak P., Volny M.V. Havlicek, mMass 3: a cross-platform software environment for precise analysis of mass spectrometric data. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:4648–4651. doi: 10.1021/ac100818g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quirke J.M.E. Mass spectrometry of porphyrins and metalloporphyrins. In: Kadish K.M., Smith K.M., Guilard R., editors. The Porphyrin Handbook. Academic Press; 2000. pp. 371–422. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller T., Moser S., Ongania K.H., Pruzinska A., Hörtensteiner S., Kräutler B. A Divergent path of chlorophyll breakdown in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:40–42. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mühlecker W., Kräutler B., Ginsburg S., Matile P. Breakdown of chlorophyll—a tetrapyrrolic chlorophyll catabolite from senescent rape leaves. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1993;76:2976–2980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christ B., Schelbert S., Aubry S., Süssenbacher I., Müller T., Kräutler B., Hörtensteiner S., MES16 A member of the methyl esterase protein family, specifically demethylates fluorescent chlorophyll catabolites during chlorophyll breakdown in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:628–641. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.188870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spengler B., Kirsch D., Kaufmann R. Metastable decay of peptides and proteins in matrix-assisted laser-desorption mass-spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1991;5:198–202. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1290060207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman L., Long F.A. Mass spectra of 6 lactones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953;75:2832–2836. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karni M., Mandelbaum A. The even-electron rule. Org. Mass Spectrom. 1980;15:53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowen R.D., Harrison A.G. Loss of methyl radical from some small immonium ions—unusual violation of the even-electron rule. Org. Mass Spectrom. 1981;16:180–182. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.