Abstract

We examined the endothelial transient receptor vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) channel’s vasodilatory signaling using mathematical modeling. The model analyzes experimental data by Sonkusare and coworkers on TRPV4-induced endothelial Ca2+ events (sparklets). A previously developed continuum model of an endothelial and a smooth muscle cell coupled through microprojections was extended to account for the activity of a TRPV4 channel cluster. Different stochastic descriptions for the TRPV4 channel flux were examined using finite-state Markov chains. The model also took into consideration recent evidence for the colocalization of intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (IKCa) and TRPV4 channels near the microprojections. A single TRPV4 channel opening resulted in a stochastic localized Ca2+ increase in a small region (i.e., few μm2 area) close to the channel. We predict micromolar Ca2+ increases lasting for the open duration of the channel sufficient for the activation of low-affinity endothelial KCa channels. Simulations of a cluster of four TRPV4 channels incorporating burst and cooperative gating kinetics provided quantal Ca2+ increases (i.e., steps of fixed amplitude), similar to the experimentally observed Ca2+ sparklets. These localized Ca2+ events result in endothelium-derived hyperpolarization (and SMC relaxation), with magnitude that depends on event frequency. The gating characteristics (bursting, cooperativity) of the TRPV4 cluster enhance Ca2+ spread and the distance of KCa channel activation. This may amplify the EDH response by the additional recruitment of distant KCa channels.

Introduction

A complex bidirectional communication between endothelial (EC) and smooth muscle (SMC) cells regulates SMC constriction and vessel tone. Cytosolic calcium (Ca2+) regulates the ability of ECs to induce the release of vasoactive signals including the discharge of hyperpolarizing current to the SMC. In small resistance vessels, this NO-independent endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing (EDH) signaling is typically mediated by the activation of intermediate- (IKCa) and small- (SKCa) conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels in response to an increase in Ca2+ concentration (1,2). Global EC Ca2+ mobilization results from transmembrane Ca2+ influx and/or Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores. Evidence suggests that localized Ca2+ influx from spontaneous or agonist-induced opening of the transient receptor vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) channel can also induce SMC hyperpolarization and vessel dilation through the EDH mechanism in resistance vessels (3–5).

TRPV4 channels are sensitive to a wide array of stimuli including epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, diacylglycerol and phorbol esters via PKC-dependent and independent pathways, osmotic changes, mechanical stimuli, Ca2+ levels, and temperature (6–8). In the vasculature, EC agonists like acetylcholine (4,5,9), shear stress (10), and sustained low pressures (3), in addition to exogenous agonists like GSK1016790A, 4-α phorbol 12,13-didecanoate (4αPDD), or 11-12 epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, may activate TRPV4 channels to produce a transient stationary Ca2+ burst (sparklet) within the EC that may ultimately result in vasodilation. Single-channel patch-clamp data reveals stochastic TRPV4 opening with pA current amplitude at resting membrane potential (−50 mv) (11). Activation of as few as three channels per EC may be sufficient to induce maximal vessel dilation (4). The role of individual activators and pathways resulting in TRPV4 channel openings is under investigation, as of this writing. Recent evidence suggests bursting activity and cooperative opening of TRPV4 channels in a cluster (4). The physiological relevance of such gating mechanisms has not been elucidated.

EC extensions over the internal elastic lamina toward SMCs, termed myoendothelial projections (MPs), have been observed in small-diameter vessels (12,13), and can play a role in the modulation of vascular tone (14). Recent studies provide evidence for the localization of TRPV4 channels with IKCa, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), and connexins in/near MPs (3,15–18). Myoendothelial gap junctions (MEGJs) are often found at the tip of the MP, and allow for electrochemical communication between ECs and SMCs (12,13). Spontaneous and agonist-induced localized Ca2+ events mediated by transmembrane Ca2+ influx (TRPV4 sparklets (3–5)) or intracellular store Ca2+ release (pulsars (16) and wavelets (19)) have been observed in ECs near the MP sites.

Mathematical modeling offers a systematic approach for the analysis of complex signaling mechanisms, and it can serve as a tool for data interpretation and for guiding new experimental studies. Few theoretical studies have been carried out to investigate the role of ECs and MPs in the modulation of SMC Ca2+ and membrane potential (Vm) dynamics. We have previously examined SMC Ca2+ and Vm changes during EC stimulation through the development of an EC-SMC compartmental model (20). This model integrates detailed single EC (21) and SMC (22) models with electrical, chemical, and NO coupling pathways. Acetylcholine stimulation of ECs in the model increased global EC Ca2+ levels, activated EDH and NO pathways to hyperpolarize the SMC, and ultimately reduced global Ca2+ concentration in the SMC. We have also extended the compartmental model into a two-dimensional continuum model that incorporates accurate MP geometry from electron microscopy images and spatial localization of IKCa and IP3Rs in the MP. This formulation was utilized to investigate the role of feedback in EC-SMC communication (23). Similarly, Brasen et al. (24) have developed a two-dimensional axisymmetric model incorporating the anatomical structure of MPs into a two-cell system. Their results show that MPs may rectify the signal between the EC and SMC. Previous models did not examine the role of TRPV4 channels. Moreover, they considered deterministic whole-cell current descriptions for membrane channels and pumps, and did not account for localized and stochastic channel openings.

In this study, we present the development of a computational model to examine the localized Ca2+ mobilization, in the vicinity of the MP, arising from a single or a cluster of TRPV4 channels. The TRPV4s were incorporated into a previously developed continuum EC-SMC model with MPs. The model accounts for preferential presence of the TRPV4s near the MPs as suggested in experimental studies. Stochastic opening of a TRPV4 channel was captured using a finite-state Markov chain. We utilize this model to examine the contribution of these channels to the regulation of vessel tone.

Materials and Methods

Continuum model

We have presented a general computational framework for modeling spatiotemporal Ca2+ events integrated with plasma membrane electrophysiology in single or coupled vascular cells in Nagaraja et al. (23) and Kapela et al. (25). The model assumes EC and SMC to be simplified rectangular domains with dimensions as shown in Fig. 1 A and implements only half of the EC and SMC by assuming symmetry for the other half. Moreover, the model incorporates an accurate MP geometry from experimental images and assumed high density of IKCa (25% of total, under control conditions) and IP3Rs (10% of total) within the MP. The continuum model takes into account concentration gradients of Ca2+ and other ions within the EC and MP. The transport for individual ionic species is influenced by both electrical and concentration gradients, and was described using the Nernst-Planck electrodiffusion equation,

| (1) |

where S = Na+, K+, Cl−, and Ca2+; Ds is the diffusion coefficient of ionic species S; zs is the valence of ionic species S; ∇V is the electrical gradient; F is the Faraday constant; and umS is the ionic mobility given by Ds/RT (where R is the ideal gas constant (8341 mJ∙mol−1∙K−1), and T is the absolute temperature). Rs is the source/sink term, which includes the expressions for cytosolic Ca2+ exchange with the ER/SR, and Ca2+ buffering in the EC and MP. The value δbuff accounts for the Ca2+ buffering in the SMC using a fast buffering approximation. Transport of cytosolic IP3 and Ca2+ within a uniformly distributed ER/SR store was described using

| (2) |

where [S] is the concentration of any of the species (IP3, Ca2+ ER, and SR) in the store. Rs is the source/sink term and includes Ca2+ exchange between stores and the cellular domains, and IP3 production and degradation. A uniform distribution of transmembrane channels and pumps was considered along the boundary of the cellular domains. The membrane currents were defined as boundary fluxes across the top and bottom boundaries of the EC, SMC, and the MP boundaries, as

| (3) |

where n is the normal to the surface and Ns is the membrane flux given by summation of all the transmembrane currents for species S (IS,K). The membrane currents were distributed between the MP and bulk cell according to their respective volumes. The membrane current definitions and parameters are identical to the original models (20–22,25).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the continuum EC-SMC model. (A) Two-dimensional axisymmetric model geometry with SMC and EC as rectangular domains coupled with EC MP and MEGJs. (B) Cartoon illustration describing all the channels and pumps incorporated in the EC-MP-SMC continuum model in (A).

To estimate the characteristics of the TRPV4-mediated Ca2+ event in the EC and resulting vessel tone modulation, the model in Nagaraja et al. (23) was modified through the introduction of the single or a cluster of four TRPV4 channels in a localized region on the EC boundary 0.5 μm away from the MP (Fig. 1 B). The current carried by each cation S (ITRPV4,S) through a single TRPV4 channel is described as

| (4) |

where Si is the concentration of Ca2+, K+, and Na+ inside the EC; So is the extracellular concentration; F is the Faraday constant; PTRPV4,S is the ionic permeability; and Vm is the membrane potential. The net current (ITRPV4,total) through the channel modulates the membrane potential (Vm) described using standard Hodgkin Huxley formalism (21), as follows:

| (5) |

A single TRPV4 channel-conductance of 45 pS for inward currents (at −100 to 0 mV) was reported using inside-out patch-clamp under symmetric intra- and extracellular ionic concentrations (26), and a single channel-conductance of 56–66 pS for inward currents (at −100 to 0 mV) was observed under near-physiological ionic concentrations using a cell-attached patch-clamp technique (11). We estimated the permeability for each ion (PTRPV4,S) to match these conductances using the ITRPV4, total description (Eqs. 4 and 5) and reported the permeability ratios (PTRPV4,Ca:PTRPV4,K:PTRPV4,Na = 7.1:1.42:1 (27)). The calculated Ca2+ permeability for a single TRPV4 channel PTRPV4,Ca was 6.8 × 10−13 – 8.5 × 10−13 cm3/s (which corresponds to 4 × 10−8–5 × 10−8 cm/s assuming 1 μF/cm2 standard membrane capacitance and total EC membrane capacitance of 17 pF). In the model we use PTRPV4,Ca control value of 4.5 × 10−8 cm/s. This corresponds to control values for PTRPV4,Na and PTRPV4,K of 6.5 × 10−9 cm/s and 8.77 × 10−9 cm/s, respectively.

Stochastic opening of TRPV4 channel

Two-state model

Individual channels are not constantly open and the ionic currents fluctuate stochastically. A single channel can be represented using a continuous-time homogenous finite-state Markov chain, which describes reversible transitions between a finite number of distinct states in which the ion channel can reside (28,29). The probability of transitions from one state to another is assumed to be independent of the current state. As a simplest case, we considered the TRPV4 channel to be either in a conducting (open) or nonconducting (close) state, presented here as Mechanism 1,

where O is the open state, C is the close state, and α and β define the rate of transition from one state to another.

The probability density function for the closed-channel lifetime (fc) and the open-channel lifetime (fo) are distributed exponentially, as follows:

| (6) |

The mean lifetime in any state is given by the reciprocal of sum of the transition rates that lead away from the state (30). This provides a mean open lifetime and mean closed lifetime of 1/α and 1/β, respectively, for the two-state model in Mechanism 1, given above. The transition rates α, β were calculated based on the reported mean open time (37 ms; 1/α) in Sonkusare et al. (4) and an assumed mean closed time of 780 ms (1/β). This estimate for the mean closed time provides an open probability (Po; β/(α + β)) for an individual two-state TRPV4 channel of 0.045 as observed in Sonkusare et al. (4).

Three-state model

Ca2+ data obtained from a cluster of TRPV4 channels (3,4) reveals a Ca2+ burst of few seconds followed by longer inactivity periods, suggesting burst kinetics (i.e., openings are separated by short closed periods, before a long closed period). The two-state model cannot capture the experimentally observed Ca2+ burst. We simulated stochastic opening of a single TRPV4 channel using a simple three-state model (28) given here as Mechanism 2,

where B is the blocked state (intraburst short closed state), O is the open state, and S is the shut state (interburst long closed state). The values k1, k2, k3, and k4 define the rates of transition from one state to another. The TRPV4 channel can reside in either of these three states. The model in Mechanism 2, given above, results in mean open time, mean blocked time, mean shut time, and burst length given by 1/(k3 + k1), 1/k2, 1/k4, and (1 + k1/k2)/k3, respectively. The transition rates k1–k4 were calculated based on the reported mean open time (37 ms) of the TRPV4 channel, and observed long inactivity (shut time) of ∼1 min and burst duration of ∼5 s from the Ca2+ data in Sonkusare et al. (4). We assumed a mean channel blocked time (∼33 ms) to obtain an overall channel Po of 0.045 as in the two-state model. The overall probability P0 was calculated as described in Colquhoun and Hawkes (28). The three-state model provides a significantly higher open probability during the burst (Poburst) of ∼0.5.

Cluster of independent or cooperative TRPV4 channels

Stochastic openings of a cluster of four independent TRPV4 channels, with each individual channel represented by the Markov two- and three-state chain described in Mechanisms 1 and 2, respectively, were simulated using a reduced transition rate matrix (see the Supporting Material). Given a group of N independent and identical TRPV4 channels, the probability that k of these channels are open, p(k), is described by the binomial distribution as follows:

| (7) |

A 2-min-long simulation of a cluster of four independent channels followed the binomial distribution (see Results). The Po of each individual channel in a cluster of four independent channels was observed as before to be 0.045, using both the two- and three-state models. The average number of open (active) TRPV4 channels (NPo) in this simulation was 0.17 (close to the theoretical value of 4∗Po of 0.18).

Data in Sonkusare et al. (4) suggest that simultaneous opening of two, three, or four TRPV4 channels are significantly more frequent than expected based on the binomial distribution, indicating an interaction between the channels within a cluster. The cooperative two- and three-state models account for these channel interactions in a cluster through modulation of the transition rate from closed to open state (β), and shut state to open state (k4), respectively, when at least one other channel in the cluster is in the open state (see the Supporting Material). For example, as shown in Fig. 2 for a cluster of four channels described using the three-state model, if channel 3 is in open state, the transition rate k4 for channels 1, 2, and 4 was increased to k4′ to allow for cooperativity between the channels. Cooperativity increased the average number of open (active) TRPV4 channels (NPo) to 0.27 in both the two- and three-state models.

Figure 2.

Cooperativity implementation of four TRPV4 channels. (A) Four TRPV4 channels in a cluster described using a simple two-state (open and close) Markov chain model. The rate parameter β, for transition of a channel from the closed state to the open state, was increased in the presence of at least one other channel in the open state. (B) TRPV4 channels implemented using a three-state (shut, block, and open) Markov chain to capture burst opening of the channel. The rate parameter k4 describing the transition of a channel from the shut state to the open state was increased in the presence of at least one other channel in the open state.

Results

Continuous TRPV4 opening

A single TRPV4 channel opening was simulated through the introduction of TRPV4 current (Eq. 5). Ca2+ levels arising from continuous opening of the TRPV4 channel for 10, 100, 200, and 4000 ms are depicted as color-coded in Fig. 3 A. A micromolar increase in Ca2+ levels was observed within few milliseconds in a small area (0.25 μm2) around the TRPV4 channel location. Channel opening for longer durations increases the spread area of the Ca2+ event. The resulting Ca2+ spread can activate Ca2+-activated potassium channels (KCa) in the vicinity of the TRPV4 location. The contour lines in Fig. 3 B (black, yellow, red, and brown) represent the region of Ca2+ spread for 10, 100, 200, and 4000 ms TRPV4 open durations, respectively. The region was defined by Ca2+ concentrations higher than the half-activation of the IKCa channel ((EC50) 740 nM (31)). Simulations predict Ca2+ activity spreading up to 0.3–6 μm radial distances for 10–4000 ms open time durations. The increase in the Ca2+ spread area did not increase linearly with channel open time.

Figure 3.

Spatial Ca2+ profiles resulting from a single TRPV4 channel opening. (A) Continuous opening of the TRPV4 channel for open times of 10, 100, 200, and 4000 ms resulted in micromolar Ca2+ concentrations progressively spreading over a larger area. (B) Contour lines (Ca2+ concentration equal to EC50 of IKCa) indicate increasing Ca2+ spatial spread for 10, 100, 200, and 4000 ms of continuous opening of a TRPV4 channel and highlight the time evolution of the cell regions with at least 50% IKCa activity. To see this figure in color, go online.

Stochastic TRPV4 opening

Stochastic opening of a TRPV4 channel represented by a simple two-state Markov model (Mechanism 1) was simulated using a transition rate matrix (Eq. S3 in the Supporting Material) with α = 2.7 × 10−2 ms−1 and β = 1.3 × 10−3 ms−1. A representative single channel record of 120-s duration is shown in Fig. S2 A in the Supporting Material, displaying random opening and closing of the TRPV4 channel with an overall Po value of 0.045. Simulations with a two-state model could not capture the long quiescent period of TRPV4 channel inactivity observed in the experiment (4).

Three-state model

A three-state Markov chain model (Mechanism 2) was used to describe a single TRPV4 channel exhibiting bursting activity. Simulations were performed using a transition rate matrix obtained from the three-state model with k1 = 2.35 × 10−2 ms−1, k2 = 4.35 × 10−2 ms−1, k3 = 3.23 × 10−4 ms−1, and k4 = 1.69 × 10−5 ms−1 (Eq. S4 in the Supporting Material). These values were derived from the observed open time, open probability, interburst interval, and burst duration in Sonkusare et al. (4), as described in Materials and Methods. A representative single channel record with burst openings is shown in Fig. 4 A. TRPV4 superposition records for a cluster of four independent channels were simulated (data not shown) using the reduced transition rate matrix of the three-state model (Eq. S7 in the Supporting Material). Comparison between a single TRPV4 channel and a cluster of TRPV4 channels enable us to examine the physiological relevance of channel clustering in mediating Ca2+ signaling and EDH.

Figure 4.

Stochastic opening of a cluster of four TRPV4 channels implemented using a three-state Markov chain to simulate burst opening of the channel. (A) Illustrative example of a temporal profile of a single TRPV4 channel transition between the conducting (open) and nonconducting states (shut, block). (B) Example of a superposition temporal profile of the TRPV4 cluster, with the level number describing the number of open channels at a given time. (Inset) Zoomed-in view of a segment of the total simulation time for better visualization. (C) Experiment (4) (solid bar) and cooperative channel gating in the Markov model (solid checkered) demonstrated increased open probabilities of second, third, and fourth channel openings, respectively, relative to the binomial distribution (shaded) and a Markov model (shaded checkered) considering independent channels.

Cooperativity was implemented by increasing the transition rate k4 to k4′ when at least one other channel is in the open state. An eightfold increase in k4′ was considered to match the experimentally observed NPo value (Fig. S1). An illustrative superposition record of a cooperative TRPV4 cluster is displayed in Fig. 4 B. A significant number of second-, third-, and fourth-level openings is observed during the burst period followed by a long period of channel idleness (compare with Fig. S2 B). Similar to the two-state model, a cluster of independent channels resulted in an open probability distribution (Fig. 4 C, shaded checkered bar), which follows a binomial distribution (Fig. 4 C, shaded bar). An increase in the probabilities for second-, third-, and fourth-level openings was observed for simulations with cooperativity (Fig. 4 C, solid checkered bar), in agreement with the experimental observation (Fig. 4 C, solid bar). Statistical χ-squared test described in Draber et al. (32) was carried out to confirm for cooperativity in the simulations. The three-state model with cooperativity is able to closely capture the salient features of the TRPV4 cluster from the experiments. The different model implementations for the TRPV4 cluster allow us to examine the role of bursting and cooperativity in the modulation of vessel tone.

Ca2+ and Vm dynamics: stochastic continuum model

In the absence of agonist stimulation (i.e., no Ca2+ release from the stores), we examined the Ca2+ and Vm changes induced from the opening of a cluster of EC TRPV4s in the continuum model. Stochastic current (Istochastic,TRPV4,S) from the TRPV4 channel cluster is provided by

| (8) |

where ITRPV4,S(t) is the TRPV4 flux as described by the GHK equation (Eq. 5) and N(t) is the number of open TRPV4 channels at time t given by superposition records such as the records in Figs. 4 B and 5 B.

Figure 5.

Representative example of observed temporal EC Ca2+ and EC Vm profiles from the stochastic opening of the TRPV4 cluster in the continuum model. (A) Superposition temporal profile of TRPV4 cluster with cooperative gating kinetics implemented using the three-state model. (Right inset) Zoomed-in view for better visualization. (B) EC Ca2+ concentration around the TRPV4 cluster (0.25 μm2 area) arising from the TRPV4 openings in (A). (C) EC Vm transients follow the EC Ca2+ events. (D) Local EC Ca2+ concentration around the TRPV4 cluster (0.25 μm2 area) observed in different stochastic simulations.

A 2-min-long representative simulation using the three-state cooperative model is displayed in Fig. 5. The stochastic TRPV4 openings (Fig. 5 A) and the average Ca2+ concentration in a small area (0.25 μm2) around the cluster’s location (Fig. 5 B) are depicted. The TRPV4 current resulted in quantal Ca2+ increases with fixed amplitude of ∼4 μM. (Note: Average Ca2+ levels depend on the sampled region around the cluster; for an area of 2 μm2, the amplitude was 1.8 μM.) Long inactivity periods following these stochastic Ca2+ transient bursts. Ca2+ events in different simulations are shown in Fig. 5 D. The Ca2+ transients closely resemble, in duration and spread area, the fluorescence recording of Ca2+ sparklets in the experiments (4,5).

The simulated Ca2+ sparklets activated the localized IKCa channels (25% of total in the vicinity of the TRPV4s) to produce EC (and SMC) hyperpolarization. The EC Vm profile shows hyperpolarizations corresponding to each Ca2+ sparklet (Fig. 5 C). An average EC hyperpolarization of ∼2.3 mV was estimated in the 2-min-long simulation.

Simulations were carried out using the alternative model implementations for the TRPV4 cluster openings. Spatial Ca2+ profiles obtained at the time of maximum Ca2+ spread, using: 1) the two-state model with independent channels (top, no bursting activity); 2) the three-state model with independent channels (middle, bursting activity); and 3) the three-state model with interacting channels (bottom, bursting activity with cooperativity) are depicted as color-coded in Fig. 6 A. The contour lines represent the region of the EC where the Ca2+ concentration is above the value of IKCa EC50. Model simulations with no bursting activity or cooperativity (two-state independent channel model) resulted in ∼2 μm maximum radial distance for half-activation of the IKCa channels (Fig. 6 B). Bursting activity (three-state independent channel model) and bursting activity with cooperativity (three-state cooperative model) increased this radial distance by ∼3.2- and 4.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 6 B).

Figure 6.

Increase in distance of IKCa channel activation arising from burst and cooperative gating kinetics in the TRPV4 cluster. (A) Ca2+ concentration profile in the EC and the SMC at the time of maximum Ca2+ spread. TRPV4 channel cluster implemented with a two-state model (top, no bursting or cooperative gating kinetics), three-state model (middle, bursting activity), and three-state model with channel interactions (bottom, bursting and cooperativity). (Contour lines) Ca2+ concentration equivalent to EC50 of IKCa channels. (B) Radial distance for half-maximum KCa channel activation in the simulations in (A). To see this figure in color, go online.

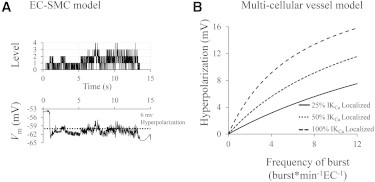

In the model we simulate a single EC coupled to a single SMC. We also assumed that under control conditions, 25% of the total IKCa channels are localized in close proximity to the TRPV4 cluster (i.e., within 1 μm). This corresponds to 36 IKCa channels, based on whole-cell IKCa conductance () of 1.7 nS, single IKCa channel conductance of 17pS, and open probability of 0.7 (21,33). Fig. 7 A shows temporal changes in the EC Vm induced by the TRPV4 Ca2+ sparklet in a representative simulation. (Note: Similar levels of SMC hyperpolarization were obtained for a MEGJ resistance of 0.9 GΩ (20,34).) Mean EC Vm hyperpolarization of ∼6 mV is predicted during sparklet activity. Under the assumed arrangement of the TRPV4 and IKCa channels in the model, the second-, third-, and fourth-level TRPV4 opening resulted in ∼1.5–4.5 mV depolarization, attenuating the Ca2+-induced hyperpolarization.

Figure 7.

Predicted Vm hyperpolarization induced by a localized Ca2+ increase through TRPV4 channels (Ca2+ sparklet). (A) Temporal EC Vm profile (bottom) indicates an average EC hyperpolarization of ∼6 mV during the bursting activity of the TRPV4 cluster (top) in the single EC/single SMC model. (B) Hyperpolarization of the endothelium as a function of sparklet frequency and IKCa localization, predicted for an intact vessel with EC and SMC layers coupled by MEGJ.

In vivo, the hyperpolarization induced by TRPV4 sparklet in individual ECs will spread through homocellular gap junctions to neighboring ECs and through MEGJs to SMCs, causing vessel hyperpolarization and dilation. The bursting response in an individual cell from the IKCa channel activation seen in the model (Figs. 5 C and 7 A) will be smoothed, giving rise to a steady change in vessel’s membrane potential. The mean hyperpolarization of the endothelium will be determined by the frequency and duration of the sparklet events. Assuming TRPV4 sparklets with a mean duration, τburst; an average frequency of occurrence per EC site, fburst; and an average number of active sites per EC, nsites yields an average number of ECs, N = 1/(τburst × fburst × nsites), having an active event and open IKCa channels at any given time. Thus, hyperpolarizing current from each sparklet will spread, on average, in N cells. The resulting hyperpolarization of the endothelium can be approximated from a simplified electrical equivalent of an intact vessel segment (Fig. S3 and see Eq. S9 in the Supporting Material). For a representative scenario of τburst = 5 s, fburst = 2 bursts per min per active site, and one active site per cell nsites =1 (i.e., N = 6), IKCa conductance

(representing 25% of IKCa channels or 36 channels activated by a single TRPV4 sparklet), and net EC-SMC membrane resistance

of ∼1.2–2.2 GΩ (for RmEC = 2–10GΩ, RmSMC = 2GΩ, and RmME = 0.9GΩ (34–38)), the estimated vessel hyperpolarization is ΔVm ≈ 2–3.4 mV (Eq. S9 in the Supporting Material). Fig. 7 B shows how this hyperpolarization can increase as a function of the sparklet frequency per EC (fburst × nsites) and the fraction of IKCa () localized around the TRPV4 cluster. In the presence of 36 (25% of total), 72 (50%), and 144 (100%) localized IKCa channels around the TRPV4 cluster, the TRPV4-mediated Ca2+ sparklet (with assumed mean duration of 5 s) results in a vessel hyperpolarization of 0.3–15 mV for sparklet frequency between 0.1 and 12 bursts/min per EC (Fig. 7 B). Similar results were obtained with a multicellular computational model of an intact vessel segment (39). The vessel model predicted a similar ΔVm value of 2.3 mV in the endothelium (simulating opening of 25% of IKCa channels in one EC out of 6 ECs (i.e., N = 6)). According to Eq. S9 in the Supporting Material, hyperpolarization also depends on the membrane resistance, and in microvessels with higher input resistance, achieved levels of hyperpolarization may be greater relative to larger vessels.

Discussion

The primary aim of the study was to examine the regulatory mechanism of EC TRPV4 channels in inducing vessel relaxation. Using the two-dimensional EC-SMC continuum model coupled with MP, we examined the localized Ca2+ events arising from activation of a single TRPV4 channel and a cluster of TRPV4 channels in the EC and the resulting vasodilatory response. Simulations showed the effect of TRPV4 and IKCa channel distribution, and burst and cooperative gating kinetics of TRPV4 channels in defining the localized Ca2+ event (sparklet), and the resulting SMC hyperpolarization.

Endothelial control of vascular tone is attributed to EC Ca2+ mobilization that may manifest as events with different spatiotemporal characteristics. Agonist or mechanical stimulation, for example, may increase global Ca2+ levels, the frequency of Ca2+ waves/oscillations, the presence and frequency of Ca2+ pulsars (events mediated by IP3Rs in the vicinity of MP (16,35)), or of Ca2+ sparklets (events mediated by EC TRPV4 channels (3–5)). Evidence suggests a central role of TRPV4 channels in agonist- and mechanical-induced vasoactive signaling in the microcirculation (3–5).

TRPV4 Ca2+ sparklet

The model predicts local micromolar Ca2+ increases from a single TRPV4 channel opening for the duration of the channel’s open time (Fig. 3). The obtained Ca2+ levels in a small region around the TRPV4 channel are significantly higher than the nanomolar global Ca2+ increases usually observed experimentally (16,35) or predicted theoretically (21) in response to agonist or mechanical stimuli. These high local Ca2+ concentrations may be required to fully activate cellular components with low Ca2+ affinity, including IKCa channels whose affinity may be in the high nanomolar range (reported EC50 values as high as 300–740 nM (31,40)).

Multiple TRPV4 channel opening in a cluster resulted in localized quantal Ca2+ increases (Fig. 5, B and D). Second-, third-, and fourth-level openings in the TRPV4 cluster lead to essentially constant amplitude increases in Ca2+ concentrations that return quickly to the previous baseline after channel closure, consistent with the experimental data (3–5). This allows examining channel gating characteristics based on the changes in Ca2+ levels, as was done in the experimental studies (4,5). The model corroborates the methodology utilized in these earlier analyses and shows that Ca2+ diffusion, extrusion, and buffering have minimal effect on the interpretation of the data.

In the experiments, TRPV4 channels with an average open time of milliseconds (4) generate a Ca2+ burst event (i.e., sparklet) of 1–10 s duration, followed by a long inactivity period before the occurrence of the next event. The significant increase in duration of the Ca2+ event, compared to channel open times, can be a result of bursting activity of the TRPV4 channel. Bursting kinetics of TRPV4s have been observed in single channel patch-clamp data (11,26). Model implementation of bursting in a cluster of four TRPV4 channels (Figs. 4 and 5) resulted in Ca2+ events lasting for seconds followed by longer inactivity periods (Fig. 5, B and D), as observed in the experiments. Burst activity in a cluster of independent TRPV4 channels enhanced the Ca2+ spread and activated IKCa channels at longer distances (Ca2+ concentrations >50% activation within 5 μm) (Fig. 6, A and B).

Cooperative activation of TRPV4 channels in a cluster has been suggested in experiments because multilevel openings appear much more frequently than suggested by the binomial distribution for random events (4). We have accounted for cooperativity in channel kinetics, capturing the increased probability of multilevel openings seen in the experiments. Cooperativity further enhances the Ca2+ spread. The combined effect of bursting and cooperativity is a Ca2+ spread of ∼7 μm (defined as the radial distance with Ca2+ levels greater than IKCa EC50). Thus simulations suggest that the gating characteristics of TRPV4 cluster increase the sparklet’s area and presumably the resulting hyperpolarization by the recruitment of additional IKCa channels. It will be interesting to examine the effect of clustering of other TRP channels such as of TRPA1 and TRPV3, which have been shown to facilitate endothelium-dependent dilation in cerebral arteries (41,42). The coupled stochastic-continuum model presented here could be extended toward the analysis of experimental data from stimulation of such channels.

TRPV4-mediated hyperpolarization

EC hyperpolarization through the activation of IKCa and SKCa channels is a major contributor in NO-independent endothelium-derived vasodilation in microvessels (2). TRPV4 Ca2+ sparklets may activate nearby IKCa channels (3,4) to induce hyperpolarization and dilation. We tested the potential of TRPV4 sparklets to mediate EDH responses. The presence of high-density cellular components, including the KCa channels near microdomain structures like MPs, has been reported in small-resistance vessels (3,12,13,16,19). Micromolar localized Ca2+ increases around the MPs can potentially fully activate the nearby KCa channels (assuming an EC50 as high as 740 nM). In the model of a single EC coupled to a single SMC, a TRPV4 sparklet activated colocalized IKCa channels in the vicinity of the cluster to generate ∼6 mV of hyperpolarization in the EC (Fig. 7 A).

Although cooperative gating in the cluster increased the Ca2+ spread (Fig. 6 A), it showed no significant amplification of hyperpolarization (data not shown). This was attributed to the positioning of a high density of IKCa channels within a very close proximity to the cluster (<1 μm). Within this area even a single TRPV4 channel produces saturating Ca2+ concentrations so multilevel opening in a cluster does not offer any additional advantage. On the contrary, at physiological ionic concentrations and around resting Vm, significant sodium influx currents (pA) are predicted from each TRPV4 opening. This can result in a few millivolts depolarization, which in the absence of additional KCa channel recruitment will have an attenuating effect on EDH signaling. Thus, the high Na+ influx and the micromolar Ca2+ levels in the vicinity of the TRPV4 cluster arising from a single channel opening suggest that bursting and cooperatively may benefit EDH signaling only if KCa channels are positioned at intermediate distances (3–10 μm) away from the cluster. Under the assumed arrangement of TRPV4 and IKCa channels in the model, we observed that second, third, and fourth TRPV4 channel opening from cooperative gating kinetics, result in a ∼1.5–4.5 mV depolarization (Fig. 7 A).

Sustained vessel hyperpolarization results from the spread of transient hyperpolarization generated in a single EC cell to its neighbors. The achieved vessel hyperpolarization will depend on many parameters including membrane resistances of the EC and SMC layers, the MEGJ resistance, the transient hyperpolarizing current, and the frequency and duration of the events. Simulations suggest a significant EC hyperpolarization through activation of TRPV4 channels, which increases with increasing the frequency and duration of the event and the amount of the KCa channels in proximity to the TRPV4 cluster (Fig. 7 A). Our calculations suggest that experimentally observed TRPV4 Ca2+ sparklets that typically have an average duration of ∼5 s and frequency of occurrence of two bursts/min per EC should induce ∼2.0 mV hyperpolarization, assuming that 36 channels (25% of total) are located near the cluster (Fig. 7 B). This is lower than what has been observed in experiments (∼10 mV) (4). This discrepancy may be attributed to a higher number of sparklet events/sites than observed experimentally, a very high number of KCa activated by each sparklet (i.e., the majority of IKCa), or to mechanisms amplifying TRPV4/IKCa-mediated hyperpolarization. Moreover, the predicted level of hyperpolarization depends on parameters such as membrane resistances (Eq. S9 in the Supporting Material) that have not been accurately characterized and which may change with stimulation or could vary between vessels. Furthermore, as the size of a vessel decreases, input resistance typically increases and this may result in significantly higher hyperpolarization for a given transmembrane current.

Local versus global Ca2+ activity

It is well established that a variety of stimuli can elicit global Ca2+ increases in ECs. A typical Ca2+ response has an initial transient that is mediated by store Ca2+ release (with peak concentrations of ∼0.4–1.5 μM (35,43)) followed by a lower plateau phase that is sustained by Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ permeable channels in the plasma membrane. This global Ca2+ mobilization is thought to mediate vasoactive signaling, including EDH responses. However, studies showed activation of IKCa channels by localized Ca2+ events such as pulsars and sparklets (3–5,16), and that a moderate global Ca2+ increase (∼30% above resting) by CPA (cyclopiazonic acid) did not lead to a significant activation of KCa channels in Ledoux et al. (16). Thus, evidence points toward a preferential activation of IKCa channels and EDH response to local rather than global Ca2+ increases.

Is there a mechanism that would allow for a portion of KCa channels to be relatively immune to global Ca2+ mobilization so that their activity can be regulated preferentially/exclusively by localized Ca2+ signaling? One possibility is that compartmentalization of TRPV4 and KCa channels may provide a locally confined, regulatory unit relatively inaccessible to global Ca2+ changes. Restriction of Ca2+ signals to subplasmalemma regions has been reported, suggesting the presence of cytosolic compartments (16,24,35,44,45).

Simulation results provide an alternative possibility. The preferential activation of the KCa channels to local rather than global Ca2+ increases may be a result of significantly higher Ca2+ concentrations in localized events (micromolar levels are predicted in the model (Fig. 6, B and D)) relative to nanomolar global Ca2+ increases during EC stimulation (21,35). Provided that the KCa EC50 is in the high nanomolar range, global Ca2+ levels may not be sufficient to fully activate KCa and thus a significant portion of the channels is activated only by the high concentration local Ca2+ event. However, reported values for IKCa affinity for Ca2+ range from ∼100 nM to 740 nM (31,35,40,46). The predicted high local Ca2+ concentrations will be beneficial only if the EC50 is in the high end of this range. (Note: A high EC50 (740 nM, i.e., low affinity) for IKCa channels was assumed in the simulations.)

Interestingly, a high Ca2+ affinity for IKCa channels can make these channels significantly (if not fully) activated by global Ca2+ events. In this case, subsequent TRPV4 activation may result in EC depolarization that will attenuate rather than promote EDH. (Note: Recruitment of saturated KCa channels will not compensate for the depolarizing TRPV4 current.) An intermediate scenario where an IKCa channel is activated by both local events and global transients might also be possible. Further experimentation is required to determine the relative contribution of global and local Ca2+ events on IKCa channel activation.

Limitations

Many of the parameter values used here have not been previously quantified or may vary between different vessels. In this study, we try to remain consistent with our previous EC-SMC models with respect to parameter values and whole cell currents and examine responses over a range of values for parameters with significant uncertainty. The model is limited by the absence of quantitative data for the spatial distribution of important cellular components. Such data may significantly improve the predictive ability of the proposed models. The TRPV4 channel current was modeled using a GHK equation and ignores the effects of temperature, shear, and modulatory pathways on the channel. Moreover, simple Markov chain models were considered that can capture the observed channel behavior, but the actual gating mechanism could be more complex.

Conclusions

The developed model describes TRPV4-mediated signaling for the regulation of vessel dilation. Model simulations are in good agreement with experiments in isolated vessels, corroborating data for the role of TRPV4 signaling in vascular control. The model predicts a micromolar-localized Ca2+ increase through activation of cluster of four TRPV4 channels. This is significantly higher than the nanomolar global Ca2+ levels typically observed during EC stimulation. The model shows an enhanced Ca2+ spread as a result of burst opening and cooperative channel gating in the TRPV4 cluster. Ca2+ mobilization over several micron radial distances can recruit KCa channels and produce millivolts of EDH. The model predicts that amplification of EDH signaling by cooperativity in the TRPV4 cluster is more likely if KCa channels are not immediately adjacent to the TRPV4 channels, but at distances that can reach 10 μm away. The magnitude of the resulting hyperpolarization depends on a variety of parameters, including the sparklet frequency and the effective membrane resistance of the vessel wall. Nevertheless, for a wide range of parameter values predicted, TRPV4-induced hyperpolarization underestimates what has been recorded in some experiments. This may suggest additional mechanisms contributing to the observed EDH response.

Author Contributions

J.P., A.K., and N.M.T. are responsible for conception and design of the research; J.P. developed the computational code and performed the simulations; J.P., A.K., and N.M.T. interpreted the results of simulations; J.P. drafted the manuscript; J.P., A.K., and N.M.T. edited and revised the manuscript; and J.P., A.K., and N.M.T. approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant numbers HL95101 and HL121778 from the National Institutes of Health (to N.M.T.). J.P. was supported by a Dissertation Year Fellowship from the University Graduate School of Florida International University.

Supporting Material

Supporting Citations

Reference (47) appears in the Supporting Material.

References

- 1.Edwards G., Félétou M., Weston A.H. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors and associated pathways: a synopsis. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:863–879. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0817-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garland C.J., Hiley C.R., Dora K.A. EDHF: spreading the influence of the endothelium. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011;164:839–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagher P., Beleznai T., Dora K.A. Low intravascular pressure activates endothelial cell TRPV4 channels, local Ca2+ events, and IKCa channels, reducing arteriolar tone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:18174–18179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211946109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonkusare S.K., Bonev A.D., Nelson M.T. Elementary Ca2+ signals through endothelial TRPV4 channels regulate vascular function. Science. 2012;336:597–601. doi: 10.1126/science.1216283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonkusare S.K., Dalsgaard T., Nelson M.T. AKAP150-dependent cooperative TRPV4 channel gating is central to endothelium-dependent vasodilation and is disrupted in hypertension. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:ra66. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heller S., O’Neil R.G. TRP Ion Channel Function in Sensory Transduction and Cellular Signaling Cascades. Taylor & Francis; London, UK: 2007. Chapter 8. Molecular mechanisms of TRPV4 gating. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strotmann R., Schultz G., Plant T.D. Ca2+-dependent potentiation of the nonselective cation channel TRPV4 is mediated by a C-terminal calmodulin binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:26541–26549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilius B., Vriens J., Voets T. TRPV4 calcium entry channel: a paradigm for gating diversity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C195–C205. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00365.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Earley S., Pauyo T., Brayden J.E. TRPV4-dependent dilation of peripheral resistance arteries influences arterial pressure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;297:H1096–H1102. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00241.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendoza S.A., Fang J., Zhang D.X. TRPV4-mediated endothelial Ca2+ influx and vasodilation in response to shear stress. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010;298:H466–H476. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00854.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe H., Vriens J., Nilius B. Heat-evoked activation of TRPV4 channels in a HEK293 cell expression system and in native mouse aorta endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:47044–47051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandow S.L., Haddock R.E., Plane F. What’s where and why at a vascular myoendothelial microdomain signaling complex. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2009;36:67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heberlein K.R., Straub A.C., Isakson B.E. The myoendothelial junction: breaking through the matrix? Microcirculation. 2009;16:307–322. doi: 10.1080/10739680902744404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr P.M., Tam R., Plane F. Endothelial feedback and the myoendothelial projection. Microcirculation. 2012;19:416–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2012.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandow S.L., Neylon C.B., Garland C.J. Spatial separation of endothelial small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (KCa) and connexins: possible relationship to vasodilator function? J. Anat. 2006;209:689–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledoux J., Taylor M.S., Nelson M.T. Functional architecture of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling in restricted spaces of myoendothelial projections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9627–9632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801963105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isakson B.E. Localized expression of an Ins1,4,5P3 receptor at the myoendothelial junction selectively regulates heterocellular Ca2+ communication. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:3664–3673. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dora K.A., Gallagher N.T., Garland C.J. Modulation of endothelial cell KCa3.1 channels during endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor signaling in mesenteric resistance arteries. Circ. Res. 2008;102:1247–1255. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran C.H., Taylor M.S., Welsh D.G. Endothelial Ca2+ wavelets and the induction of myoendothelial feedback. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C1226–C1242. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00418.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapela A., Bezerianos A., Tsoukias N.M. A mathematical model of vasoreactivity in rat mesenteric arterioles: I. Myoendothelial communication. Microcirculation. 2009;16:694–713. doi: 10.3109/10739680903177539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silva H.S., Kapela A., Tsoukias N.M. A mathematical model of plasma membrane electrophysiology and calcium dynamics in vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C277–C293. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00542.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapela A., Bezerianos A., Tsoukias N.M. A mathematical model of Ca2+ dynamics in rat mesenteric smooth muscle cell: agonist and NO stimulation. J. Theor. Biol. 2008;253:238–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagaraja S., Kapela A., Tsoukias N.M. Role of microprojections in myoendothelial feedback—a theoretical study. J. Physiol. 2013;591:2795–2812. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.248948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brasen J.C., Jacobsen J.C., Holstein-Rathlou N.H. The nanostructure of myoendothelial junctions contributes to signal rectification between endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapela A., Tsoukias N.M. Multiscale FEM modeling of vascular tone: from membrane currents to vessel mechanics. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011;58:3456–3459. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2162513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loukin S., Zhou X., Kung C. Wild-type and brachyolmia-causing mutant TRPV4 channels respond directly to stretch force. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:27176–27181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.143370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma X., Nilius B., Yao X. Electrophysiological properties of heteromeric TRPV4-C1 channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:2789–2797. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colquhoun D., Hawkes A.G. On the stochastic properties of bursts of single ion channel openings and of clusters of bursts. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1982;300:1–59. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1982.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ball F.G., Rice J.A. Stochastic models for ion channels: introduction and bibliography. Math. Biosci. 1992;112:189–206. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(92)90023-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colquhoun D., Hawkes A.G. On the stochastic properties of single ion channels. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1981;211:205–235. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1981.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahn S.C., Seol G.H., Suh S.H. Characteristics and a functional implication of Ca2+-activated K+ current in mouse aortic endothelial cells. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:426–435. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Draber S., Schultze R., Hansen U.P. Cooperative behavior of K+ channels in the tonoplast of Chara corallina. Biophys. J. 1993;65:1553–1559. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81194-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bychkov R., Burnham M.P., Vanhoutte P.M. Characterization of a charybdotoxin-sensitive intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in porcine coronary endothelium: relevance to EDHF. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:1346–1354. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto Y., Klemm M.F., Suzuki H. Intercellular electrical communication among smooth muscle and endothelial cells in guinea-pig mesenteric arterioles. J. Physiol. 2001;535:181–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilius B., Droogmans G. Ion channels and their functional role in vascular endothelium. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:1415–1459. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagaraja S., Kapela A., Tsoukias N.M. Intercellular communication in the vascular wall: a modeling perspective. Microcirculation. 2012;19:391–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2012.00171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kapela A., Nagaraja S., Tsoukias N.M. Modeling Ca2+ signaling in the microcirculation: intercellular communication and vasoreactivity. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2011;39:435–460. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v39.i5.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan X.J., Goldman W.F., Blaustein M.P. Ionic currents in rat pulmonary and mesenteric arterial myocytes in primary culture and subculture. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:L107–L115. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.2.L107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapela A., Nagaraja S., Tsoukias N.M. A mathematical model of vasoreactivity in rat mesenteric arterioles. II. Conducted vasoreactivity. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010;298:H52–H65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00546.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishii T.M., Silvia C., Maylie J. A human intermediate conductance calcium-activated potassium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11651–11656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Earley S., Gonzales A.L., Crnich R. Endothelium-dependent cerebral artery dilation mediated by TRPA1 and Ca2+-Activated K+ channels. Circ. Res. 2009;104:987–994. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.189530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Earley S., Gonzales A.L., Garcia Z.I. A dietary agonist of transient receptor potential cation channel V3 elicits endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;77:612–620. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.060715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buchan K.W., Martin W. Modulation of agonist-induced calcium mobilization in bovine aortic endothelial cells by phorbol myristate acetate and cyclic AMP but not cyclic GMP. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;104:361–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saliez J., Bouzin C., Dessy C. Role of caveolar compartmentation in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated relaxation: Ca2+ signals and gap junction function are regulated by caveolin in endothelial cells. Circulation. 2008;117:1065–1074. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.731679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rizzuto R., Pozzan T. Microdomains of intracellular Ca2+: molecular determinants and functional consequences. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:369–408. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crane G.J., Gallagher N., Garland C.J. Small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated K+ channels provide different facets of endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization in rat mesenteric artery. J. Physiol. 2003;553:183–189. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.051896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keleshian A.M., Yeo G.F., Madsen B.W. Superposition properties of interacting ion channels. Biophys. J. 1994;67:634–640. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80523-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.