Abstract

Intramembrane proteolysis has emerged as a key mechanism required for membrane proteostasis and cellular signaling. One of the intramembrane-cleaving proteases (I-CLiPs), γ-secretase, is also intimately implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, a major neurodegenerative disease and leading cause of dementia. High-resolution crystal structural analyses have revealed that I-CLiPs harbor their active sites buried deeply in the membrane bilayer. Surprisingly, however, the key kinetic constants of these proteases, turnover number kcat and catalytic efficiency kcat/KM, are largely unknown. By investigating the kinetics of intramembrane cleavage of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated β-amyloid precursor protein in vitro and in human embryonic kidney cells, we show that γ-secretase is a very slow protease with a kcat value similar to those determined recently for rhomboid-type I-CLiPs. Our results indicate that low turnover numbers may be a general feature of I-CLiPs.

Introduction

Intramembrane-cleaving proteases (I-CliPs) are unusual proteases that cleave their substrates within the membrane. Several of these enzymes have been identified in the past two decades and studied intensively. They belong to different protease classes and include the GxGD-type aspartate proteases presenilin (PS), signal peptide peptidase (SPP) and its homologous SPP-like proteases, the S2P metalloproteases, and the rhomboid serine proteases (1). Very recently, Rce1 was identified as a novel glutamate-type I-CliP (2). PS is the catalytic subunit of γ-secretase, a protease complex that contains nicastrin (NCT), APH-1, and PEN-2 as additional subunits in a 1:1:1:1 stoichiometry (3,4). Due to its close association with Alzheimer’s disease, γ-secretase is one of the best-studied I-CLiPs (5). The enzyme generates ∼4 kDa amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) species of different lengths from a C-terminal fragment of the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP), termed APP CTFβ or C99. These include the major 40-amino-acid Aβ species Aβ40 and a slightly longer species, Aβ42, which is believed to trigger Alzheimer’s disease (5). Mutations in PS and APP are associated with genetically inherited forms of the disease (6).

Cleavage of integral membrane proteins within the hydrophobic environment of the lipid bilayer has been considered an obscure process for a long time. Recently, purification and crystallization of a handful of these proteases showed that their active sites are deeply immersed in the membrane bilayer but are nevertheless water accessible, allowing intramembrane proteolysis to occur (1). However, the detailed mechanism of substrate recruitment and cleavage, as well as the underlying kinetics, remains largely unclear.

Cell-free assays in which detergent-solubilized I-CliPs, purified to various grades, are capable of cleaving a substrate in either micelles or lipid bilayers, have allowed investigators to study the enzymatic properties of I-CLiPs in more detail and to determine some of the key enzyme kinetic constants (7–12). Thus, data for the Michaelis constant KM have become available for various I-CLiPs. However, an equally important parameter, the turnover number kcat, has not been determined so far. Only recently, surprisingly low values of kcat were reported for rhomboids (e.g., only 0.0063 s−1 for E. coli GlpG, a well-characterized rhomboid (12)). Additionally, the reported kcat/KM value of GlpG showed that rhomboid substrate cleavage is highly inefficient compared with that of other well-studied proteases. These properties were recently confirmed (13). In this study, we determined kcat and kcat/KM of γ-secretase for its APP CTFβ substrate, the precursor of Aβ, both in vitro and in cultured cells. Remarkably, we found that, like rhomboids, γ-secretase is a very slow and inefficient enzyme.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

The monoclonal antibody to the NCT ectodomain (ectoNCT; Clone 35) was obtained from BD Signal Transduction Laboratories, and the monoclonal anti-His5 antibody was obtained from Qiagen. The following antibodies were used for analysis of Aβ: 2D8 to Aβ1-16 (14), 4G8 to Aβ17-24 (Covance), and C-terminal specific Aβ antibodies to Aβ38, Aβ40, and Aβ42 (15).

Cell lines

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells stably expressing Swedish mutant APP (APPsw; HEK293/sw) were described previously (16). HEK293-EBNA cells stably transfected with a fusion protein of ectoNCT with the IgG1 hinge-CH3 heavy chain (NCT-IgG) were described before (17).

Purification and reconstitution of γ-secretase into lipid vesicles

Detergent-solubilized endogenous human γ-secretase was isolated from HEK293 cells by a multistep purification procedure as described previously (18). To reconstitute γ-secretase into a lipid bilayer, first small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) of palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) were prepared by sonication. Subsequently, the enzyme was reconstituted into the SUVs by detergent dilution, followed by a 4 h incubation at 4°C (19). As reported previously (19), electron microscopy and dynamic light scattering analyses demonstrated that our SUVs and the proteoliposomes derived from them, respectively, are unilamellar and have a size of ∼30 nm.

Purification of ectoNCT

HEK293-EBNA cells stably expressing NCT-IgG were used to purify ectoNCT as described previously (17) with minor modifications. In brief, cells were cultured in Opti-MEM medium, and secreted NCT-IgG was captured by immunoprecipitation using Protein A-sepharose. Bound NCT-IgG was extensively washed with STEN-NaCl (50 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.2% NP-40, pH 7.6), STEN (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl; 2 mM EDTA; 0.2% NP-40, pH 7.6), and finally with Factor Xa buffer (20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0), in which all subsequent steps were carried out. NCT-IgG was cleaved with Factor Xa (New England Biolabs) to release ectoNCT, which was further purified using WGA-agarose beads (Calbiochem). After overnight binding and subsequent washing, ectoNCT was eluted from the WGA-agarose beads using 250 mM N-acetylglucosamine. The purity of the ectoNCT was analyzed by combined western blot/Ponceau S staining analysis and its concentration was determined with the Bradford method.

Kinetic model of substrate processing by γ-secretase

γ-Secretase cleaves its APP CTFβ substrate in a complicated stepwise manner starting with an endoproteolytic cleavage at the ε-site, releasing the amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain (AICD), followed by carboxy-terminal trimming, liberating Aβ species of different lengths (20). Since the initially generated longer and intermediate Aβ forms Aβ49(48) and Aβ46(45) are not measurable in our analysis, our kinetic model applies to the overall substrate processing by γ-secretase to the final Aβ end products, i.e., the generation of the major Aβ species (mainly Aβ42, Aβ40, and Aβ38). This simplified kinetic analysis is based on the following reaction:

| (1) |

where APP CTFβ is the substrate, E is the free γ-secretase enzyme, ES is the enzyme-substrate complex, and Aβ is the sum of the Aβ end products. Applying Michaelis-Menten kinetics to this reaction, we obtain

| (2) |

where V is the steady-state rate of the reaction, KM is the Michaelis-Menten constant, S is the substrate concentration, Et is the total enzyme concentration, and kcat is the turnover number of overall APP CTFβ substrate processing by γ-secretase.

Determination of KM and Vmax of γ-secretase in vitro

Purified recombinant APP C100-His6 substrate was prepared as previously described (3) and added to aliquots of proteoliposomes at room temperature (RT) followed by immediate incubation at 37°C. The pH of the assay mixture was 6.4 (19), i.e., in the range of the reported optimal pH of γ-secretase (pH 6.3–6.5) (21,22). The reaction was stopped at different time points by addition of an excess amount of PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100. The respective amounts of Aβ (Aβ38 + Aβ40 + Aβ42) generated in the assay were then measured by Aβ sandwich immunoassay as previously described (14). From these data, the total Aβ concentration in the incubation volume of the proteoliposomes was calculated. One purified enzyme preparation was used for three independent experiments with four different substrate concentrations (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 μM), and Aβ was measured after 0, 4, 8, and 16 h of incubation. Another enzyme preparation was used for two larger experiments with five different substrate concentrations (0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, and 1.6 μM). In these experiments, Aβ was measured after 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 16, and 32 h of incubation. To compare the results obtained with the proteoliposomes of the two different enzyme preparations, the concentration of Aβ generated at each time point was normalized with respect to the total concentration of γ-secretase, which was determined by NCT quantitation as described below. Subsequently, we evaluated whether the changes in the concentration of Aβ followed first-order kinetics with time t, i.e.,

| (3) |

where k is the rate constant, Aβ(∞) is the final Aβ concentration, and Aβ(t) the concentration of Aβ at incubation time t. Assuming that Aβ(0) = 0, the solution of this equation becomes

| (4) |

Using GraphPad PRISM 5.0 software, the parameters k and Aβ(∞) of the one phase association function (Eq. 4) were fitted to all data points (i.e., Aβ(t) at t = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 16, and 32 h). Subsequently, the initial rates of Aβ production (V0) were determined from the fitted linear slopes of Aβ formation from the data points at t = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8 h. Values of Vmax and apparent KM were then calculated by plotting V0 against S and fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Eq. 2) by nonlinear regression, using Vmax and KM as independent variables.

Quantification of total and active γ-secretase

The total amount of γ-secretase in the proteoliposomes (Et) was determined by immunoblotting using the monoclonal anti-NCT antibody and quantification of NCT with known amounts of purified ectoNCT (17) as protein standard by measuring the respective enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) signal intensities using the FluorChem 8900 detection system (Alpha Innotech). The concentration of active enzyme (Ea) in the proteoliposomes was determined by active-site titration as outlined previously (23). In brief, after a 1 h preincubation of γ-secretase proteoliposomes at RT in the presence of increasing concentrations of the transition-state analog inhibitor L-685,458 (24), 0.5 μM C100-His6 was added and substrate cleavage was allowed to proceed overnight at 37°C. The Aβ and AICD immunoblot signals obtained with 2D8 and anti-His5 antibodies, respectively, were quantified as above using the FluorChem 8900 detection system. The amounts of Aβ and AICD produced in the absence of inhibitor were set to 100%. Ea was then extrapolated from the linear decrease in enzyme activity (23).

Determination of kcat in cells

Two experimental groups (groups A and B) consisting of six independent cultures of HEK293/sw cells were incubated at 37°C to allow secretion of Aβ. For each group, cultures 1–3 were analyzed after 4 h and cultures 4–6 were analyzed after 8 h. After the respective incubation times, the rate of total Aβ production (V) was derived from the amount of total secreted Aβ, which was quantified via an Aβ sandwich immunoassay as previously described (15). Levels of cellular γ-secretase and APP CTFβ substrate were determined from cell lysates (prepared with STEN-lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitors (Sigma)) additionally containing 1% SDS) by immunoblotting using the monoclonal anti-NCT antibody or antibody 2D8, respectively, and quantitation of the immunoblot signals using known amounts of ectoNCT or C100-His6 as protein standards. kcat was calculated from the Michaelis-Menten equation.

| (5) |

Here KM is the real KM, i.e., the KM with respect to the volume of the POPC bilayer of the proteoliposomes. The real KM was derived from the apparent KM determined in vitro (see Eq. 13 below). To calculate S per volume of the lipid phase of the cells, an estimation of the amount of plasma membrane (PM) and endosomal lipids relative to the experimentally determined total cellular protein amount of the cell lysates was required. From the amount of these lipids, the volume of the lipid phase was calculated. Subsequently, S was calculated from the amount of cellular APP CTFβ divided by the volume of the lipids. From the experimental data, V was calculated as pmol/h and Et was calculated as pmol. Consequently, the dimension of kcat calculated from Eq. 5 is h−1. Alternatively, kcat was recalculated from Eq. 5 using the in vitro real KM relative to the surface area of the proteoliposomes (Eq. 14 below), and recalculating S in the cells relative to the surface area of PM and endosomal membranes.

Estimation of the volume and surface area of PM and endosomal lipids in HEK293 cells

First, we estimated the total amount of phospholipids in the PM and endosomal compartments. The experimentally determined phospholipid/protein ratio for HEK293 cells is ∼125 nmol phospholipids/mg protein (25). In baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells, which presumably have a similar distribution of lipids among the different cell compartments compared with HEK293 cells, it was previously found that 17% of the cellular phospholipids are in the PM (26). To estimate the amount of lipids in the endosomal fraction, we used data from a previous electron microscopy study of BHK cells (27), which reported that the membrane surface of endosomes is 430 μm2/cell and the total membrane area is 15,860 μm2/cell. Thus, the percentage of lipids of the endosomal fraction relative to the total membrane lipids is 430/15,860 = 2.7%. Combining these data, we concluded that for BHK cells, the PM and endosomal fraction contain ∼20% of the total cellular phospholipids. Thus, we calculated the amount of phospholipids of HEK293 cells as

| (6) |

To estimate the volume of this phospholipid fraction, we assumed that the average volume of the cellular phospholipid species (i.e., choline, ethanolamine, anionic phospholipids, and sphingomyelins) is similar to the volume of POPC, i.e., 1100 Å3/POPC molecule, which is justified (28). Thus, the volume of the phospholipid fraction is

| (7) |

Since one PC molecule at the lipid-water interface of a phospholipid bilayer occupies 71.7 Å2 (28), the total surface area of a bilayer of PC becomes

| (8) |

To calculate the volume and surface area of additional membrane lipids, we took their distribution into account. For the PM of BHK cells, a composition of 63% w/w phospholipids, 30% w/w cholesterol, and 7% other lipids (such as glycolipids) was previously reported (26). Similar lipid distributions were found for the PM of other mammalian cells (29–31). Neglecting the 7% other lipids, we assumed that the PM and the endosomal membranes for HEK293 cells are composed of phospholipids and cholesterol only, at a 2:1 (w/w) ratio. Since on average the molecular weight (MW) of phospholipids is about twice that of cholesterol, we calculated the volume of all lipids from the sum of all phospholipids and cholesterol, taking a 1:1 molar ratio. The volume of one cholesterol molecule is 623 Å3 (28).

| (9) |

Since the surface area of one cholesterol molecule at the lipid-water interface of a bilayer of a PC/cholesterol mixture is 37 Å2 (28,32), the surface area of the cholesterol fraction of the membrane is

| (10) |

Combining Eq. 6 with Eqs. 7 and 9, we obtain

| (11) |

Combining Eq. 6 with Eqs. 8 and 10, we obtain

| (12) |

Results

Determination of kcat and apparent KM in vitro

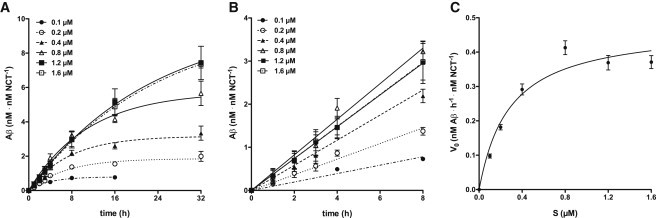

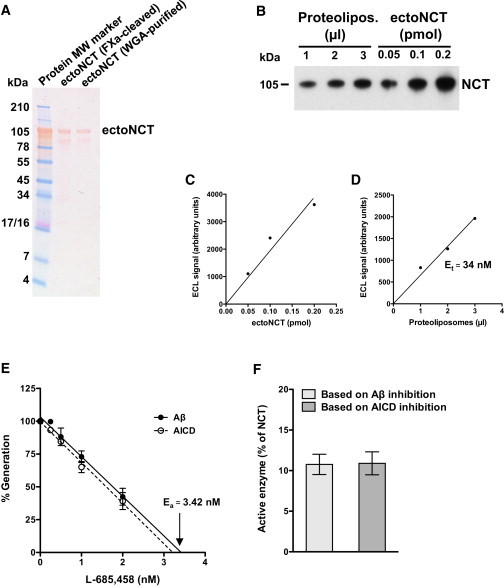

To determine kcat as well as kcat/KM of γ-secretase, we used our previously established cell-free in vitro assay in which the purified endogenous enzyme from HEK293 cells is reconstituted into preformed SUVs composed of POPC (19). Purified C100-His6 γ-secretase substrate, a recombinant APP CTFβ variant (3), was added at different concentrations to the proteoliposomes. For each substrate concentration (S), we measured the corresponding Aβ production at different time points of incubation at 37°C using an Aβ immunoassay (15) (Fig. 1 A). There was no apparent major delay in the production of Aβ upon addition of substrate to the proteoliposomes (Fig. 1 A), suggesting that the added substrate is incorporated instantaneously into the proteoliposomes. To correct for variations in enzyme activity of the proteoliposome preparations used, we normalized the Aβ production of each individual experiment with respect to the total enzyme concentration Et. To determine the Et of the proteoliposomes, we used purified recombinant ectoNCT as a standard (see Fig. 2, A–D). The concentrations of Aβ during time t (Fig. 1 A) were fitted to single exponential association kinetics (Eq. 4). From the fitted endpoints (Aβ(∞)), we found that the final Aβ concentration was on average ∼35% of the initial substrate concentration, i.e., only 35% of added substrate could be processed by γ-secretase (see Discussion below). For each substrate concentration, the initial rate (V0) was determined from the linear increase in the concentration of Aβ during the first 8 h of incubation (Fig. 1 B). The good fits indicated that the steady-state condition (S>>E) was fulfilled at all of the substrate concentrations used. Finally, V0 was plotted against S (Fig. 1 C). Vmax and apparent KM were derived by fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Eq. 2). The average value of Vmax was 0.476 ± 0.047 nM Aβ h−1 nM NCT−1 and was 0.285 ± 0.091 μM. Although our value was comparable to those previously reported by others (7–11), our Vmax value cannot be strictly compared with previously published values, since the enzyme concentrations in the previous studies were not determined and may have varied (8–11).

Figure 1.

In vitro kinetics of γ-secretase. (A) Time course of in vitro Aβ generation by γ-secretase. γ-Secretase proteoliposomes were incubated with 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, and 1.6 μM of C100-His6 APP substrate, respectively, at 37°C. For each indicated incubation time (t = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 16, and 32 h), the respective concentration of total Aβ was measured. The data points represent the mean ± SE of two to five independent experiments (see Materials and Methods). Note that for some data points the error bars are too small to be displayed. The lines represent fitted curves to single exponential association kinetics. (B) Data from A for the first 8 h of incubation. For each substrate concentration, V0 was obtained from the slope at t = 0 by fitting the data to a linear increase of Aβ during time. (C) Michaelis-Menten plot. For each individual substrate concentration (S), the fitted mean ± SE of V0 from the data in (B) was taken. The line represents the fit of the data points to the Michaelis-Menten equation. From this fit, the values for Vmax (0.476 ± 0.047 nM Aβ h−1 nM NCT−1) and (0.285 ± 0.091 μM) were obtained.

Figure 2.

Quantification of γ-secretase in the in vitro assay. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of the recombinant ectoNCT. Ponceau S staining showed that both ectoNCT preparations yielded purified protein that migrated at the expected MW. A higher degree of purity was obtained for the WGA-purified ectoNCT, qualifying this protein preparation as standard for the γ-secretase determination. (B) Immunoblot analysis of γ-secretase proteoliposomes in comparison with the ectoNCT protein standard. Small aliquots of one of the proteoliposome preparations used for the in vitro assays shown in Fig. 1 A were comigrated with known amounts of purified ectoNCT protein standard and detected with an anti-NCT monoclonal antibody. (C and D) Determination of total γ-secretase (Et). (C) The ECL signal intensities of the immunoblot shown in (B) were plotted to obtain an ectoNCT standard calibration curve. (D) From the same immunoblot, the ECL signal intensities of aliquots of the proteoliposomes were compared with the calibration curve, allowing for an estimation of the concentration of NCT, i.e., the total γ-secretase present in the proteoliposomes. Et was 34 nM. (E) Active-site titration of γ-secretase. There was a close correlation between the decrease in Aβ and AICD production with increasing L-685,458 concentrations. Data points represent the mean ± SE of three measurements. Ea was 3.42 nM or 3.21 nM based on the extrapolation of Aβ and AICD data, respectively. (F) Determination of the active γ-secretase enzyme pool. Et, determined from the amount of NCT (D) was compared with Ea, determined from the active site inhibitor titration (E). The fraction of active γ-secretase in proteoliposomes (Ea/Et) was 10.1% and 9.5% based on the Aβ and AICD data (E), respectively. In a total of four independent enzyme purifications, we found that only 11% (mean ± SE = 10.8 ± 1.2) of γ-secretase present in the proteoliposomes was in an active conformation.

Our Vmax, expressed in a dimension normalized to Et, is in fact the turnover number, i.e., kcat = 0.476 h−1. However, since only a small fraction of reconstituted γ-secretase is in an active conformation (18), this evaluation of kcat is probably an underestimation. By determining the active enzyme concentration (Ea) with active-site titration experiments, we found that in four different proteoliposome preparations, including those used for Fig. 1 A, Ea was on average only 11% of Et (Fig. 2, E and F). Taking this into account, we conclude that kcat is 9.1 times higher, i.e., kcat = 4.33 ± 0.43 h−1.

Determination of real KM and catalytic efficiency kcat/KM

To next calculate kcat/KM of γ-secretase in proteoliposomes, one should bear in mind that in our assay the substrate and the enzyme are both present in the membrane. Thus, the real concentration of the substrate depends on the amount of lipids in the assay and not on the total aqueous volume of the incubation assay (33). In our in vitro assay, the lipid concentration was 0.7 mM. This means that the real KM equals 0.285 μM/0.7 mM = 0.041 mol% relative to phospholipid, which is ∼3 times lower than the KM value of 0.14 mol% reported for rhomboid GlpG (12).

Alternatively, to calculate the real KM relative to the volume of the membrane, we assumed that the volume of one POPC molecule in a lipid bilayer is 1100 Å3 (28). Thus, the real KM, relative to the volume of the phospholipids (Eq. 7) is

| (13) |

Applying Eq. 13, the real KM becomes 0.285 μM × 2165 = 0.617 mM. Correcting also for the observation that on average only 35% of added substrate was available for cleavage (Fig. 1 A), the real KM becomes 0.35 × 0.617 mM = 0.216 mM. Thus, we calculate the catalytic efficiency of γ-secretase as kcat/KM = 0.0012 s−1/0.216 mM = 5.6 s−1M−1.

Since association of the substrate to γ-secretase is a two-dimensional diffusion process, it is also meaningful to express KM as mol/area. Because the surface area of a bilayer of POPC is NAV × 71.7 Å2/mol lipid (Eq. 8), the real KM is calculated as follows:

| (14) |

Applying Eq. 14, the real KM becomes 0.285 × 10−6 /302 = 0.94 nmol/m2. Again with the correction that 35% of substrate was available for cleavage (Fig. 1 A), the real KM becomes 0.35 × 0.94 = 0.33 nmol/m2.

Determination of kcat and KM in HEK293 cells

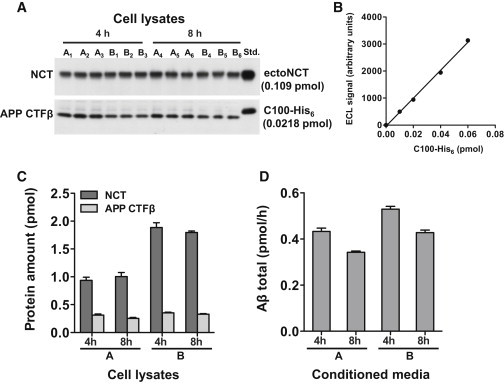

Since in vitro γ-secretase appeared to be such a slow enzyme (kcat = 4.33 h−1), we sought to also estimate the kcat value for γ-secretase in living cells. To this end, we allowed two independent groups of cultured HEK293/sw cells (groups A and B) to secrete Aβ for either 4 h or 8 h (Fig. 3, A–D). We then measured the steady-state rate of Aβ production (V), the total protein, the steady-state amount of APP CTFβ substrate, the amount of total γ-secretase, and calculated kcat as described in Materials and Methods. In the first three cell lines of group A (Fig. 3, A–D), after 4 h, V was 0.433 ± 0.014 pmol/h. The APP CTFβ substrate amount in the cell lysates was 0.311 ± 0.021 pmol and the amount of γ-secretase complexes was 0.936 ± 0.056 pmol. We assumed that the real KM value determined in vitro would be the same in cells (KM = 0.216 mM). Thus, from the measured amount of APP CTFβ in the cell lysates, we needed to calculate the substrate concentration in the cells relative to the lipid volume. Since it was not possible to experimentally determine the amount of lipids of the cellular organelles in which γ-secretase was embedded, we made an estimation taking into account that Aβ generation by γ-secretase from APPsw occurs both at the PM and in endosomes (34,35). To calculate the lipid content of these cellular compartments, we used data from the literature (see Materials and Methods). The total protein of the cell lysates was 596 ± 23 μg, so that the total volume of the PM and endosomal fraction, as calculated from Eq. 11, was 26.0 × 0.596 =15.5 nl. Thus, the steady-state APP CTFβ concentration relative to the volume of PM and endosomal lipids was 0.311 pmol/15.5 nl = 0.0201 mM. Finally, applying Eq. 5, we calculated kcat = 5.43 h−1. We also repeated the calculation for the three cell lines of group A with 8 h Aβ secretion and the cell lines of group B. The average of these four determinations was 6.00 ± 0.34 h−1, which is similar to the in vitro kcat. Alternatively, when we recalculated the substrate concentration with respect to the surface area of the PM and endosomal lipids (Eq. 12), and used the real KM of γ-secretase relative to the surface area of POPC (KM = 0.33 nmol/m2), the kcat calculated from the cellular experiments was 5.8 h−1. This is nearly indistinguishable from the cellular kcat (6.0 h−1) calculated based on the volume of the lipids.

Figure 3.

Determination of cellular γ-secretase and APP CTFβ levels, and Aβ production rates. (A and B) Immunoblot analysis of cellular γ-secretase and APP CTFβ levels. Two groups of six independent cultures (A1–A6 and B1–B6, respectively) of HEK293/sw cells were analyzed. Cultures 1–3 of each group were analyzed after 4 h and cultures 4–6 after 8 h. Equal aliquots of the corresponding cell lysates were immunoblotted with the monoclonal anti-NCT antibody and with antibody 2D8 to APP CTFβ, respectively. The signals were compared with known amounts of purified ectoNCT and C100-His6 loaded on the same gel (Std.). Immunoblot signals of the ectoNCT (see Fig. 2C) and C100-His6 protein standards (B) were in the linear range. Note that the cell lysates of the cultures of group A were generated in half the volume compared with those of group B to adjust for the ∼2-fold higher cell number of the cultures of group B. (C) Quantification of A. The ECL signal intensities of the immunoblots shown in A were used to determine the protein amount of γ-secretase and APP CTFβ. (D) Aβ production rate. The average rate of total Aβ production for groups A and B was calculated from the amount of total secreted Aβ in media conditioned for 4 h and 8 h, measured by an Aβ sandwich immunoassay detecting all secreted Aβ species. In (C) and (D), data are represented as mean ± SE (n = 3).

Discussion

To better understand the kinetics of γ-secretase, we set out to determine the turnover number kcat, which had remained elusive in previous enzyme kinetic studies of γ-secretase (7–11). Similarly to the kcat values reported for rhomboids (12), the kcat of γ-secretase was very low in the cell-free assay (4.33 h−1). Although our initially derived apparent KM was similar to previous studies (7–11), for our kinetic analysis of γ-secretase, we took into consideration the fact that the substrate and enzyme are both embedded in the membrane. Therefore, we calculated a real KM in a dimension with respect to the lipid phase (33). Furthermore, the of γ-secretase derived from the Michaelis-Menten plot (Fig. 1 C) also had to be corrected for the fact that not all added substrate was cleaved in the in vitro assay. This was not unexpected, as a random membrane orientation of both substrate and enzyme theoretically would lead to a 50% mismatch, such that maximally 50% of the substrate could be cleaved. Since we found that only 35% of added substrate could be processed by γ-secretase, indeed a partial mismatch between the orientation of the incorporated substrate and the orientation of the reconstituted enzyme in the membrane might have occurred. Additionally, a fraction of the added substrate may not have assumed a cleavable transmembrane conformation. Taking all of these considerations into account, we found that the real KM was 0.216 mM, which is comparable to the real KM that we calculated for rhomboids (Table 1) from the previously reported data (12) by taking the volume of the lipid bilayer of the proteoliposomes into account.

Table 1.

Comparison of real KM, kcat, and kcat/KM of γ-secretase and other selected proteases

| Protease | Substrate | KM (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (s−1M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ-Secretasea | APP CTFβ (C100-His6) | 0.216 | 0.00120 | 5.6 |

| γ-Secretaseb | APP CTFβ (C99) | 0.216 | 0.00167 | 7.7 |

| Rhomboid GlpGc | FITC-TatA | 2.1 | 0.0063 | 3 |

| Rhomboid GlpGd | FITC-TatA | 0.135 | 0.0407 | 301 |

| Rhomboid GlpGe | TatA-Flag | 2.9 | 0.0069 | 2.4 |

| Reninf | Angiotensinogen | 0.0011 | 2.4 | 2.2 ×106 |

| Chymosing | κ-Casein | 0.032 | 93.3 | 2.9 ×106 |

Determined for the proteoliposome-based assay.

Determined for cultured HEK293 cells, assuming that KM is the same as in vitro.

Calculated for the proteoliposome-based assay (KM = 0.14 mol% (12)).

Calculated for the micelle-based assay (12).

Calculated for cultured E. coli cells (KM = 0.19 mol% (12)).

Taken from Nguyen et al. (44).

Taken from Vreeman et al. (45).

Using the real KM in vitro, we were able to experimentally determine the kcat in cells. We found a remarkably good match between the kcat determined in vitro (kcat = 4.33 h−1) and that approximated in cells (kcat = 6.0 h−1), despite several assumptions that we made to calculate kcat from the measured cellular rate of Aβ production and the steady-state substrate concentration. We first assumed that the Michaelis-Menten equation (Eq. 5) applied in our experiment with living cells. The validation of the Michaelis-Menten equation assumes steady-state kinetics, i.e., d[ES]/dt = 0, which is fulfilled in vitro when Et is at least five times less than S (13,14). Although we found in our cells that the enzyme concentration is larger than the substrate concentration, d[ES]/dt = 0 is nevertheless fulfilled because the APP CTFβ substrate concentration is a steady-state concentration. Second, we assumed that the real KM of APP CTFβ in the cells is the same as the real KM of C100-His6 in vitro. We calculated the real KM from the apparent KM obtained from the in vitro experiment, taking the POPC lipids into account. Although POPC is the most common phospholipid in biological membranes, it is possible that other lipids present in cellular membranes alter the KM. Third, for cells, we determined their steady-state APP CTFβ concentration per volume of the PM and endosomal lipids. Since substrate binding to γ-secretase is a two-dimensional process, we also calculated the cellular kcat using the in vitro real KM based on the surface area of the membrane. However, there was almost no difference between the kcat calculated based on the surface area of the cellular lipids (kcat 5.8 h−1) and the kcat (6.0 h−1) calculated using the volume of these lipids. We further assumed that Et can be determined by the total amount of NCT in the cells. This is justified because there is evidence that γ-secretase complexes adopt an active conformation once they have assembled in the ER (36,37). However, since the bulk of γ-secretase resides in the early compartments of the secretory pathway where no APP CTFβ substrate is present (34,38), our determination of Et might be an overestimation and our calculated cellular kcat an underestimation. Finally, we did not take into account that γ-secretase and APP CTFβ could segregate into raft domains in the membrane (39) and thus locally the estimated substrate concentration would be higher than that calculated based on the total amount of lipids in the PM and endosomes. In this case, the local substrate concentration would be higher and our calculated cellular kcat would be an overestimation. However, despite the above assumptions, we do not expect that the actual cellular kcat is several orders of magnitudes larger.

As summarized in Table 1, γ-secretase is a very slow protease with kinetics comparable to that of rhomboids such as GlpG (12). In contrast, caspase-3, a cysteine protease, cleaves natural substrates with ∼500- to 1000-fold higher kcat values and catalytic efficiencies kcat/KM of at least 104 M−1 s−1 (40). Likewise, the soluble aspartate protease renin cleaves its natural substrate angiotensinogen ∼103 times faster than γ-secretase, whereas chymosin, another aspartate protease, is ∼105 times faster (Table 1). To our knowledge, only C5 convertase, a soluble serine protease of the complement system, has an exceptionally low kcat for its natural substrate (41). γ-Secretase thus appears to be one of the slowest and most inefficient proteases in nature. Perhaps the lipid environment of γ-secretase slows necessary conformational changes of the enzyme-substrate complex (42). Furthermore, since cleavage by γ-secretase is a multistep process, it is also possible that potential dissociation and reassociation of intermediary Aβ forms slow down the overall process (20,43).

An intriguing feature of γ-secretase is that it can cleave more than 90 different substrates (46), which do not share obvious common features in their primary structure (47). Apart from the requirement that most of the ectodomain of its type I membrane protein substrates must be shed (5), detailed mechanistic insight into how γ-secretase discriminates between substrates, as well as the role of KM and kcat in this process, is still lacking. With regard to rhomboids, Dickey et al. (12) recently found that all substrates bind very weakly to the enzyme, and that substrate discrimination is governed by differences in kcat for different substrates and not by different binding affinities, i.e., not by the KM. They argued that this mechanism is a unique feature of rhomboids. However, according to considerations by Fersht (21) and others, competition between the substrates of any enzyme is not governed by KM alone but by kcat/KM. Thus, the ratio of the rates of product formation of two competing substrates (A and B) is given by

| (15) |

Indeed, substrate competition by kcat alone will occur when the KM values are similar. This is illustrated in a specific example in Table 2 for the soluble serine protease chymotrypsin (48). For two selected peptide substrates of this protease, KM was similar but kcat varied by a factor of 54, resulting in different kcat/KM ratios for the substrates. Various other examples of this principle have been reported (e.g., for the aspartate protease pepsin (49)). Thus, variation of kcat can also be a property of soluble proteases to discriminate between substrates and is not a unique property of rhomboids (12). Moreover, according to the classic transition-state theory of catalysis (48), kcat is linked to the activation energy ΔG# for an enzyme-substrate complex ES to reach a conformation ES# in which the protease is able to cleave the substrate’s scissile bond (kcat = kf × e(−ΔG#/RT), where kf is the forward rate constant). Due to intrinsic structural and motional differences in their respective transmembrane domains (42), the required ΔG#s of different substrates to achieve a cleavable conformation might substantially vary. For some proteases, this may also involve transitory substrate binding to an exosite, i.e., a binding site distinct from the active site, which γ-secretase and rhomboids apparently have (1,8,12), although this is principally not necessary for substrate discrimination.

Table 2.

Competition by kcat alone between two substrates of chymotrypsin

| Protease | Substrate | KM (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (s−1M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsina | AcTyr-AlaNH2 | 17 | 7.5 | 440 |

| Chymotrypsina | AcPhe-GlyNH2 | 15 | 0.14 | 10 |

Taken from Fersht (21).

Conclusions

Our results show that γ-secretase, like rhomboids, is a very slow enzyme, indicating that I-CLiPs may not have evolved for high-rate protein degradation. In future studies, it will be interesting to determine whether other I-CLiPs have similarly low turnover numbers or rhomboids and γ-secretase are exceptional in this regard.

Author Contributions

F.K. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. E.W., J.T., and A.E. performed research and analyzed data. R.F. contributed analytical tools. H.S. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabriele Basset for technical assistance and Christian Haass and Dieter Langosch for critical readings of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (KNDD) and the Alzheimer Forschung Initiative e.V.

Footnotes

Frits Kamp and Edith Winkler contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Strisovsky K. Structural and mechanistic principles of intramembrane proteolysis—lessons from rhomboids. FEBS J. 2013;280:1579–1603. doi: 10.1111/febs.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manolaridis I., Kulkarni K., Barford D. Mechanism of farnesylated CAAX protein processing by the intramembrane protease Rce1. Nature. 2013;504:301–305. doi: 10.1038/nature12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edbauer D., Winkler E., Haass C. Reconstitution of γ-secretase activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:486–488. doi: 10.1038/ncb960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato T., Diehl T.S., Wolfe M.S. Active γ-secretase complexes contain only one of each component. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:33985–33993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenthaler S.F., Haass C., Steiner H. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis—lessons from amyloid precursor protein processing. J. Neurochem. 2011;117:779–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheuner D., Eckman C., Younkin S. Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 1996;2:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y.M., Lai M.T., Gardell S.J. Presenilin 1 is linked with γ-secretase activity in the detergent solubilized state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6138–6143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110126897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian G., Sobotka-Briner C.D., Greenberg B.D. Linear non-competitive inhibition of solubilized human γ-secretase by pepstatin A methylester, L685458, sulfonamides, and benzodiazepines. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:31499–31505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraering P.C., Ye W., Wolfe M.S. Purification and characterization of the human γ-secretase complex. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9774–9789. doi: 10.1021/bi0494976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kakuda N., Funamoto S., Ihara Y. Equimolar production of amyloid β-protein and amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain from β-carboxyl-terminal fragment by γ-secretase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:14776–14786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chávez-Gutiérrez L., Bammens L., De Strooper B. The mechanism of γ-secretase dysfunction in familial Alzheimer disease. EMBO J. 2012;31:2261–2274. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickey S.W., Baker R.P., Urban S. Proteolysis inside the membrane is a rate-governed reaction not driven by substrate affinity. Cell. 2013;155:1270–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arutyunova E., Panwar P., Lemieux M.J. Allosteric regulation of rhomboid intramembrane proteolysis. EMBO J. 2014;33:1869–1881. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirotani K., Tomioka M., Steiner H. Pathological activity of familial Alzheimer’s disease-associated mutant presenilin can be executed by six different γ-secretase complexes. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;27:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page R.M., Gutsmiedl A., Steiner H. β-amyloid precursor protein mutants respond to γ-secretase modulators. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:17798–17810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Citron M., Oltersdorf T., Selkoe D.J. Mutation of the β-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer’s disease increases β-protein production. Nature. 1992;360:672–674. doi: 10.1038/360672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fluhrer R., Kamp F., Haass C. The Nicastrin ectodomain adopts a highly thermostable structure. Biol. Chem. 2011;392:995–1001. doi: 10.1515/BC.2011.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winkler E., Hobson S., Steiner H. Purification, pharmacological modulation, and biochemical characterization of interactors of endogenous human γ-secretase. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1183–1197. doi: 10.1021/bi801204g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winkler E., Kamp F., Steiner H. Generation of Alzheimer disease-associated amyloid β42/43 peptide by γ-secretase can be inhibited directly by modulation of membrane thickness. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:21326–21334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.356659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takami M., Funamoto S. γ-Secretase-dependent proteolysis of transmembrane domain of amyloid precursor protein: successive tri- and tetrapeptide release in amyloid β-protein production. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:591392. doi: 10.1155/2012/591392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia W., Ostaszewski B.L., Selkoe D.J. FAD mutations in presenilin-1 or amyloid precursor protein decrease the efficacy of a γ-secretase inhibitor: evidence for direct involvement of PS1 in the γ-secretase cleavage complex. Neurobiol. Dis. 2000;7(6 Pt B):673–681. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quintero-Monzon O., Martin M.M., Wolfe M.S. Dissociation between the processivity and total activity of γ-secretase: implications for the mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease-causing presenilin mutations. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9023–9035. doi: 10.1021/bi2007146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight C.G. Active-site titration of peptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:85–101. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shearman M.S., Beher D., Castro J.L. L-685,458, an aspartyl protease transition state mimic, is a potent inhibitor of amyloid β-protein precursor γ-secretase activity. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8698–8704. doi: 10.1021/bi0005456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita S.Y., Ueda K., Kitagawa S. Enzymatic measurement of phosphatidic acid in cultured cells. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:1945–1952. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D900014-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allan D. Mapping the lipid distribution in the membranes of BHK cells (mini-review) Mol. Membr. Biol. 1996;13:81–84. doi: 10.3109/09687689609160580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffiths G., Back R., Marsh M. A quantitative analysis of the endocytic pathway in baby hamster kidney cells. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:2703–2720. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Small D.M. Plenum Press; New York/London: 1986. The Physical Chemistry of Lipids: From Alkanes to Phospholipids. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Meer G., Voelker D.R., Feigenson G.W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andreyev A.Y., Fahy E., Dennis E.A. Subcellular organelle lipidomics in TLR-4-activated macrophages. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:2785–2797. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M008748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klose C., Surma M.A., Simons K. Organellar lipidomics—background and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2013;25:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lecuyer H., Dervichian D.G. Structure of aqueous mixtures of lecithin and cholesterol. J. Mol. Biol. 1969;45:39–57. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheel G., Acevedo E., Sandhoff K. Model for the interaction of membrane-bound substrates and enzymes. Hydrolysis of ganglioside GD1a by sialidase of neuronal membranes isolated from calf brain. Eur. J. Biochem. 1982;127:245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haass C., Kaether C., Sisodia S. Trafficking and proteolytic processing of APP. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a006270. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jäger S., Leuchtenberger S., Pietrzik C.U. α-Secretase mediated conversion of the amyloid precursor protein derived membrane stub C99 to C83 limits Aβ generation. J. Neurochem. 2009;111:1369–1382. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S.H., Yin Y.I., Sisodia S.S. Evidence that assembly of an active γ-secretase complex occurs in the early compartments of the secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48615–48619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Capell A., Beher D., Haass C. γ-Secretase complex assembly within the early secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:6471–6478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dries D.R., Yu G. Assembly, maturation, and trafficking of the γ-secretase complex in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:132–146. doi: 10.2174/156720508783954695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vetrivel K.S., Thinakaran G. Membrane rafts in Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid production. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1801:860–867. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timmer J.C., Zhu W., Salvesen G.S. Structural and kinetic determinants of protease substrates. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rawal N., Pangburn M.K. C5 convertase of the alternative pathway of complement. Kinetic analysis of the free and surface-bound forms of the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16828–16835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scharnagl C., Pester O., Langosch D. Side-chain to main-chain hydrogen bonding controls the intrinsic backbone dynamics of the amyloid precursor protein transmembrane helix. Biophys. J. 2014;106:1318–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okochi M., Tagami S., Takeda M. γ-Secretase modulators and presenilin 1 mutants act differently on presenilin/γ-secretase function to cleave Aβ42 and Aβ43. Cell Reports. 2013;3:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen G., Delarue F., Sraer J.D. Pivotal role of the renin/prorenin receptor in angiotensin II production and cellular responses to renin. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:1417–1427. doi: 10.1172/JCI14276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vreeman H.J., Visser S., Van Riel J.A. Characterization of bovine κ-casein fractions and the kinetics of chymosin-induced macropeptide release from carbohydrate-free and carbohydrate-containing fractions determined by high-performance gel-permeation chromatography. Biochem. J. 1986;240:87–97. doi: 10.1042/bj2400087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haapasalo A., Kovacs D.M. The many substrates of presenilin/γ-secretase. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25:3–28. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beel A.J., Sanders C.R. Substrate specificity of γ-secretase and other intramembrane proteases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:1311–1334. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7462-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fersht A. W.H. Freeman & Co. Ltd.; Reading, UK: 1977. Enzyme Structure and Mechanism. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balbaa M., Cunningham A., Hofmann T. Secondary substrate binding in aspartic proteinases: contributions of subsites S3 and S’2 to kcat. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993;306:297–303. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]