Abstract

We report a 64-year-old lady with stage II, Immunoglobulin-G lambda multiple myeloma (MM) (standard risk), who presented with type-B lactic acidosis (LA), and multi-organ dysfunction associating myeloma progression, and ending in imminent death. In the context of literature review of all previously reported similar cases, this report highlights and discusses the association of type-B LA and MM (especially progressive disease), and also emphasizes the poor outcome. Early recognition of this condition with intensive supportive care, and treatment of multiple myeloma may improve outcomes.

Metabolic acidosis (MA) can be defined as decreased systemic pH resulting from either an increase in hydrogen ion (H+), or a reduction in bicarbonate (HCO3-). Based on the etiology, it is classified into anion gap MA and non-gap MA. Lactic acidosis (LA) is a common cause of the high anion gap MA.1 It is the normal end-product of the anaerobic breakdown of glucose in the cells.

Pyruvate+NADH+H+↔lactate+NAD+

Also the normal level of lactic acid in the serum is 0.5-1 mmol/l.1 Lactic acid can accumulate in the blood due to increased production or decreased utilization. Lactic acidosis occurs when there is an increase in lactate levels (>4 mmol/l) along with MA.1 This results in several adverse effects on human physiology. Lactic acidosis can be classified based on the pathogenesis into 2 categories: type-A LA and type-B LA.1 Type-A LA is diagnosed when there is clinical evidence of decreased tissue perfusion, or oxygenation of blood and it results from either: 1) increased production of lactate; such as in the cases of hypovolemia, cardiac failure, sepsis, and cardiopulmonary arrest, or 2) from the diminished utilization of lactate, such as in liver disease, and in thiamine deficiency.1 In contrast, type-B LA occurs when there is no evidence of decreased tissue perfusion, or oxygenation. This can occur with systemic diseases, such as renal and hepatic failure, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, toxins, drugs, and inborn errors of lactate metabolism. The link between type-B LA and malignancy is established, especially in leukemia and lymphoma.2 This case report describes the association of multiple myeloma (MM) with type-B LA, and highlights the prognostic impact of this association in a background of literature review of all reported cases of MM and LA.

Case Report

A 64-year-old lady was diagnosed in March 2012 to have standard risk, stage II (international staging system [ISS]), immunoglobulin-G lambda, MM with large osseous left femur plasmacytoma. She had fixation and radiotherapy to left femur, and then she started induction therapy with cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (CTD). She completed 5 cycles of CTD in August 2012, and achieved very good partial response, and she refused to undergo autologous stem cell transplantation. Three months later, she developed disease progression and was treated with 4 cycles of bortezomib and Velcade and low dose dexamethasone. Initially, she had good partial response, but in April 2013 she had disease progression. She was given one cycle of lenalidomide and dexamethasone, and was then admitted to the hospital in June 2013 with fatigue, decreased urine output, and sleepiness as a case of acute kidney injury, hypernatremia, sub-clinical disseminated intravascular coagulation, and progression of MM.

The vital signs at presentation were stable, with temperature 36.8°C. Her oxygen saturation was 95% on room air. She was pale, sleepy but arousable, glasgow coma scale (GCS) was 13/15, and she appeared not-toxic. The laboratory results are shown in Table 1. Blood film showed normochromic normocytic red blood cells with rouleaux formation, no schistocytes, and there were 3% circulating plasma cells. Fibrinogen was 60mg/dl, lactate dehydrogenase was 639 IU/L, haptoglobin was 87 mg/dl, and her brain CT scan did not show any acute insults. She received intravenous (IV) fluid, IV broad spectrum antibiotics, IV bicarbonate, dexamethasone, transfusion of blood, fresh frozen plasma, and cryoprecipitate.

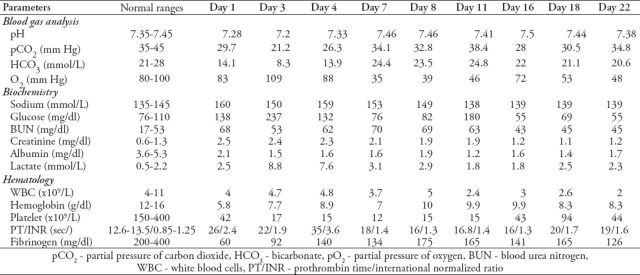

Table 1.

The progress of patient’s laboratory parameters during the hospitalization period.

Her blood and urine cultures were negative. Brain MRI showed only the presence of multiple lytic bone lesions, but there was no evidence of acute brain insult. Computed tomography scanning of the chest, abdomen and pelvis ruled out pneumonia, abdominal collection, and bowel ischemia. A new right pelvic soft tissue mass was detected (Figure 1). Biopsy from this mass revealed a soft tissue plasmacytoma in keeping with myeloma progression.

Figure 1.

Axial cut from non-contrasted pelvic CT scan (soft tissue window) showing a large destructive right iliac bone lesion with associated soft tissue mass (white arrow). There is also another destructive lesion with soft tissue component in the left iliac bone.

She remained in a state of a decreased level of consciousness with GCS of 8-10/15, and she maintained normal hemodynamic parameters until the last 2 days of her life. The progress of laboratory results is shown in Table 1. Cerebrospinal fluid examination was not feasible due to the patient’s abnormal coagulation profile entailing high risk of bleeding. During hospitalization, she developed type-B LA in day 3 of hospitalization. Intravenous thiamine was added to the treatment, and a gradual drop of lactic was noticed within a few days. Though there was measurable biochemical improvement with the intensive supportive treatment. She passed away after 23 days of hospitalization from respiratory failure.

Discussion

Multiple myeloma is a neoplasm that is associated with several metabolic abnormalities including, elevated serum creatinine, hypercalcemia, low anion gap, low value for high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high bilirubin value, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and acidosis.3 The acidosis in MM can be attributed to several causes, both acute and chronic renal insufficiency, proximal and distal renal tubular acidosis, and both type-A and B LA.4

Recent studies indicate that the increased use of the glycolytic pathway, even in the presence of oxygen, is a characteristic hallmark of malignant cells.5 This glycolytic phenotype results in increased lactic acid production. The occurrence of LA has been demonstrated in both hematologic and solid malignancies.2 There are several mechanisms proposed to explain the occurrence of LA in malignancies, including: liver and kidney dysfunction, overproduction of lactate by tumor cells, tumor cell overexpression of glycolytic enzymes, and mitochondrial dysfunction, tumor necrosis factor a, thiamine deficiency, and chemotherapy.2,5 Malignant cells favor glycolysis even when there is an abundant blood supply and normal oxygen concentrations, which is known as aerobic glycolysis, or the Warburg effect.5

It was found that malignant cells overexpress hexokinase and insulin like growth factors, both of which increase the production of lactic acid.2

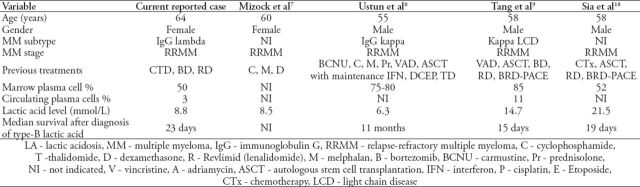

The predisposing factors for the development of LA in myeloma patients are not yet identified. In our reported case, our patient had stage II MM with standard risk category. Looking into previously reported cases, the only common denominator was the presence of relapsed disease. Other factors like immunoglobulin subtype, stage, and cytogenetic profile were variably reported. Though the survival of our patient was in a range of a few days as with other reported cases (Table 2), we cannot say that LA is a surrogate for shorter survival. Although elevated levels of lactic acid have been shown to be correlated with increased mortality.6 Some studies have also demonstrated an association between a 12-hour rise in lactate concentration above 2.5 mmol/L and multisystem organ failure.6

Table 2.

Summary of case reports of type-B LA associated with MM including the current reported case.

In conclusion, it is evident that relapsed-refractory myeloma carries a poor prognosis, and is associated with involvement of multiple body systems. Lactic acidosis may reflect tumor burden and warrants an early recognition and treatment. Physicians should consider type-B LA in patients with malignancies when there is high anion gap metabolic acidosis and normal hemodynamics. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of such cases could lead to rapid death.6 Reduction of tumor burden with chemotherapy could possibly improve the LA.2 Other treatment modalities including careful use of bicarbonate infusion, hemodialysis, thiamine replacement, and mechanical ventilation should be considered while waiting for a potential response to chemotherapy.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mahmoud Alarini, MD, for reviewing patient’s radiological figures.

Footnotes

Related Articles

Alherabi AZ, Khan AM, Marglani OA, Abdulfattah TA. Multiple myeloma presenting as dysphagia. Saudi Med J 2013; 34: 648-650.

Charafeddine KM, Kaskas HR, Zaatari GS, Mahfouz RA, Hanna TS, Sarieddine DS, et al. Patterns of monoclonal components and their correlation with different analytical parameters. Saudi Med J 2011; 32: 308-310.

Saad AA, Awed NM, Abdel-Hafeez ZM, Kamal GM, Elsallaly HM, Alloub AI. Prognostic value of immunohistochemical classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma into germinal center B-cell and non-germinal center B-cell subtypes. Saudi Med J 2010; 31: 135-141.

References

- 1.Andersen LW, Mackenhauer J, Roberts JC, Berg KM, Cocchi MN, Donnino MW. Etiology and therapeutic approach to elevated lactate levels. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1127–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruiz JP, Singh AK, Hart P. Type B lactic acidosis secondary to malignancy: case report, review of published cases, insights into pathogenesis, and prospects for therapy. Scientific World Journal. 2011;11:1316–1324. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caers J, Vande broek I, De Raeve H, Michaux L, Trullemans F, Schots R, et al. Multiple myeloma--an update on diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Haematol. 2008;81:329–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minemura K, Ichikawa K, Itoh N, Suzuki N, Hara M, Shigematsu S, et al. IgA-kappa type multiple myeloma affecting proximal and distal renal tubules. Intern Med. 2001;40:931–935. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnold RC, Shapiro NI, Jones AE, Schorr C, Pope J, Casner E, et al. Multicenter study of early lactate clearance as a determinant of survival in patients with presumed sepsis. Shock. 2009;32:35–39. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3181971d47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizock BA, Glass JN. Lactic acidosis in a patient with multiple myeloma. West J Med. 1994;161:417–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ustun C, Fall P, Szerlip HM, Jillella A, Hendricks L, Burgess R, et al. Multiple myeloma associated with lactic acidosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:2395–2397. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000040116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang P, Perry AM, Akhtari M. A case of type B lactic acidosis in multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:80–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sia P, Plumb TJ, Fillaus JA. Type B lactic acidosis associated with multiple myeloma. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:633–637. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]