Abstract

Objectives:

The objective was to assess the views of clinicians in teaching hospitals of Kolkata regarding the use of antibiotics in their own hospitals, focusing on perceived misuse, reasons behind such misuse and feasible remedial measures.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 200 clinicians from core clinical disciplines was approached in six teaching hospitals of Kolkata through purposive sampling. A structured, validated questionnaire adopted from published studies and modified to suit the responding population was completed by consenting respondents through face-to-face interaction with a single interviewer. Respondents were free to leave out questions they did not wish to answer.

Results:

Among 130 participating clinicians (65% of approached), all felt that antibiotic misuse occurs in various hospital settings; 72 (55.4% of the respondents) felt it was a frequent occurrence and needed major rectification. Cough and cold (78.5%), fever (65.4%), and diarrhea (62.3%) were perceived to be the commonest conditions of antibiotic misuse. About half (50.76%) felt that oral preparations were more misused compared to injectable or topical ones. Among oral antibiotics, co-amoxiclav (66.9%) and cefpodoxime (63.07%) whereas among parenteral ones, ceftriaxone and other third generation cephalosporins (74.6%) followed by piperacillin-tazobactam (61.5%) were selected as the most misused ones. Deficient training in rational use of medicines (70.7%) and absence of institutional antibiotic policy (67.7%) were listed as the two most important predisposing factors. Training of medical students and interns in rational antibiotic use (78.5%), implementation of antibiotic policy (76.9%), improvement in microbiology support (70.7%), and regular surveillance on this issue (64.6%) were cited as the principal remedial measures.

Conclusions:

Clinicians acknowledge that the misuse of antibiotics is an important problem in their hospitals. A system of clinical audit of antibiotic usage, improved microbiology support and implementation of antibiotic policy can help to promote rational use of antimicrobial agents.

KEY WORDS: Clinicians, rational antibiotic usage, teaching hospitals, views

Introduction

Antibiotics are frequently prescribed in clinical practice. Emergence of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms due to excessive and indiscriminate use of these drugs is a serious issue which is plaguing healthcare delivery throughout the world.[1,2] Available literature highlights the necessity of rationalization of antimicrobial therapy in developing countries.[2,3,4]

The present study sought to assess the knowledge and insight of clinicians in teaching hospitals of Kolkata regarding the usage of antibiotics in their own hospitals, with emphasis on whether they perceive any misuse of these drugs, possible reasons behind such misuse and feasible remedial measures. Acknowledging the role of pharmacologists in prescription audit and adverse drug reaction monitoring within hospitals, a comparative assessment was also done in order to determine whether the clinicians and pharmacologists differed significantly in their views regarding the issues of concern as cited above.

Materials and Methods

Permission was taken from institutional ethics committee all the institutes involved in the study before commencement. Clinicians from core clinical disciplines (as stated later) in six teaching hospitals of Kolkata were approached over a 3-month period. The sampling method was purposive. The clinicians had to be associated with the hospitals either full time or visiting at least 3 days in a week and had to be involved in actual antibiotic prescribing. The participating hospitals all had microbiology departments that offered culture-sensitivity testing.

The clinicians as well as pharmacologists were presented with a structured, validated, multiple response type questionnaire adapted from published studies and modified to suit the responding population.[3,5,6,7] Thereafter, the questionnaire was completed by the respondents through face-to-face interaction by a single interviewer. Respondents were free to leave out questions they did not wish to answer. The confidentiality of their responses was mentioned.

Data were summarized by descriptive statistics. For each question, the percentages of responses in the five options most frequently selected by the clinicians were noted and compared with the percentages of responses by the pharmacologists in the same five options. Chi-square test was applied for this purpose. GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego; 2007) software was used for analysis.

Results

Of the 200 clinicians approached, a total of 130 (65%) responded to the questionnaire. Respondents were from departments of general medicine and cardiology (26%), pediatric medicine (22%), obstetrics and gynecology (15%), general surgery (13%), orthopedic surgery (12%), dermatology (6%), and otorhinolaryngology (6%).

All respondents felt that the irrational use of antibiotics does occur in various settings within their hospitals; 72 (55.4% of respondents) felt it was a frequent occurrence and needed major rectification. About half (50.76%) felt that oral antibiotics were more misused as compared to injectable or topical ones. Adherence to a standard protocol (80%), following a proper dose schedule (67%), modification as per the resistance patterns encountered in the hospital (59.2%) and cost-effectiveness (57.7%) were perceived to be the major elements of rationality with regards to antibiotic usage.

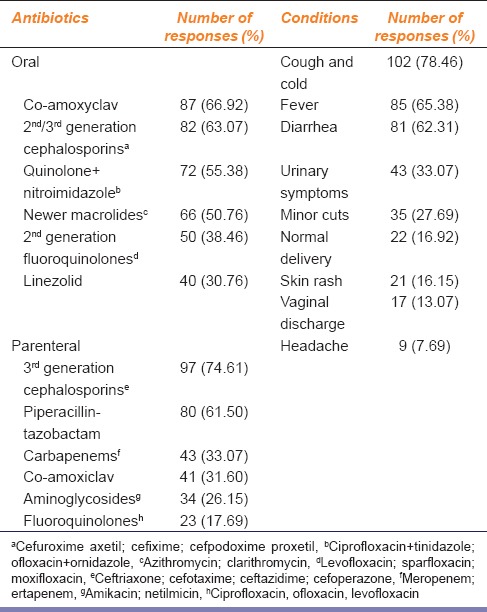

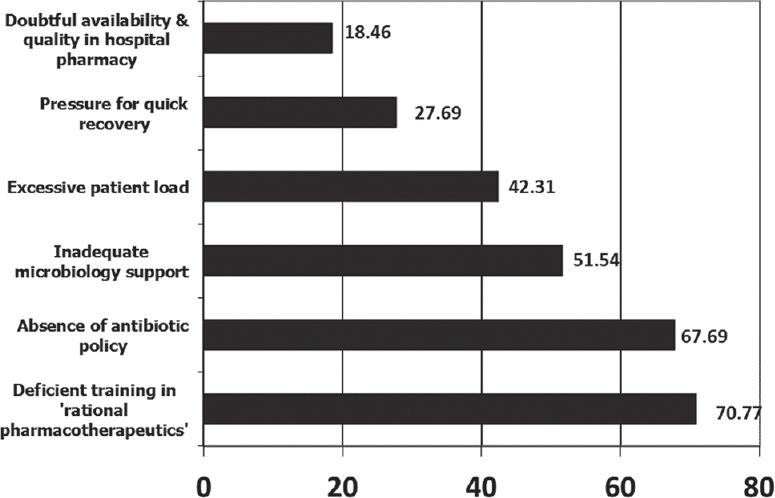

Table 1 represents the antibiotics that were perceived to be more frequently misused and the disease conditions where misuse was likely. Co-amoxiclav (66.92%) ranked the highest among oral antibiotics. Among the parenteral ones, ceftriaxone and other third-generation cephalosporins (74.61%) followed by piperacillin-tazobactam (61.5%) received maximum responses. Among topical preparations, mupirocin (52.3%), fusidic acid (36%), and neomycin (18.46%) were chosen as the most frequently misused ones. Among the clinical conditions associated with misuse of antibiotics, cough, and cold (78.46%) was ranked highest followed by fever (65.38%) and diarrhea (62.31%). The out-patient department (OPD) received the maximum percentage of responses (40%) as the most common site of irrational antibiotic prescriptions. OPD, as well as indoor prescription audit, both received equal percentage of responses (78.46%) as the two most effective ways of identifying this problem within hospital premises. Figure 1 summarizes the perceived predisposing factors behind antibiotic misuse – deficient training in rational pharmacotherapeutics (70.76%) and absence of institutional or departmental antibiotic policy (67.69%) were cited as the two most important factors. Various remedial measures were suggested by the clinicians. Incorporation of “rational therapeutics” in MBBS and postgraduate curriculum (78.46%), implementation of antibiotic policies (76.92%), improvement in microbiological support (70.76%), continuous surveillance on this issue (64.61%), improvement in the quality of drugs available in hospital pharmacies (55.38%) and assured availability of essential antibiotics in hospital pharmacies (51.53%) were given priority.

Table 1.

Antibiotics perceived to be misused and conditions of misuse

Figure 1.

Perceived reasons behind misuse of antibiotics (bar lengths denote percentages)

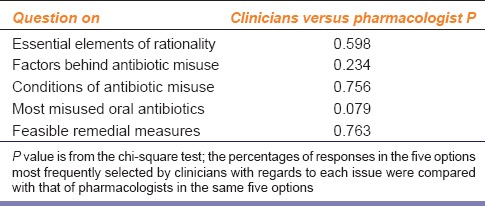

Of the 48 pharmacologists approached during the study period, 35 (72.9%) responded to the questionnaire. There were no significant differences in opinion between pharmacologists and clinicians as depicted in Table 2. The only issue of difference was the one pertaining to the perceived list of most frequently misused parenteral antibiotics. Consideration of the top five responses of clinicians to this question – third-generation cephalosporins, piperacillin-tazobactam, carbapenems, co-amoxiclav, and aminoglycosides – yielded a P = 0.015. However, on considering only the top three responses of clinicians – third-generation cephalosporins, piperacillin-tazobactam, and carbapenems – the P (0.139) did not reflect a statistically significant difference in opinion between the two groups.

Table 2.

Comparison between views of clinicians and pharmacologists on different issues

Discussion

The present study addressed the issue of antibiotic use in Indian teaching hospitals from the clinicians’ as well as pharmacologists’ perspective. Antibiotic misuse was universally acknowledged, with the OPDs perceived to be the most frequent setting for misuse and β-lactam antibiotics perceived to be the most misused ones. Training of MBBS and medical postgraduate students in rational therapeutics, framing and implementation of institutional antibiotic policy, improved microbiology support and regular surveillance on this issue were considered urgent needs. It is not surprising that the opinion of pharmacologists did not differ significantly from that of clinicians because pharmacologists, though not directly involved in patient care, are regularly in contact with hospital prescriptions during prescription audit and adverse drug reaction monitoring.

The burden of infectious diseases in India is one of the highest in the world.[3] The concern of clinicians regarding inappropriate antibiotic use is a serious matter because it not only enhances the risk of emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria but also imposes a financial burden on patients from lower socioeconomic strata who constitute the majority of those seeking treatment in Indian teaching hospitals.

Oberoi et al. expressed a similar concern that the overuse of β-lactam antibiotics is resulting in the emergence of certain strains of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in intensive care units that produce mutated forms of β-lactamases such as extended-spectrum β-lactamase, AmpC, and metallo-β-lactamases (MBL).[8] These organisms are resistant to extended-spectrum penicillins, third and fourth generation cephalosporins and even carbapenems. In India, these newer β-lactamase producing “superbugs” are posing major therapeutic challenges. This necessitates the implementation of strict guidelines for antibiotic therapy.

Remesh et al. conducted a questionnaire-based study on clinicians in a tertiary care hospital in India to assess their knowledge, attitude, and perception regarding rational antibiotic usage.[3] The participants had a perception similar to that of the respondents in the present study that antibiotics were being overused, and the existence of an essential drug list along with rational prescribing based on culture-sensitivity were of utmost importance.

The high rates of antibiotic prescriptions in developing countries find mention in other studies too. Akande et al. collected data from 630 prescriptions from the pharmacy of a Nigerian teaching hospital; 83.5% of them had least one antibiotic, mostly penicillins.[2] Khan et al. conducted a cross-sectional study on 270 hospitalized patients in Pakistan.[4] Prodigious double regimens of antibiotics were observed, and penicillins were the most misused ones. Lack of hospital formulary and pharmaceutical and therapeutic committee were the most important perceived factors behind such improper prescribing. These two studies documented β-lactam antibiotics as the most frequently misused ones, similar to this study.

The perceived necessity of proper training of future prescribers in rational therapeutics is emphasized by another questionnaire-based study with primary health care physicians in Turkey.[9] The antibiotic prescription rate was quite high, particularly among young physicians. Only 32% could indicate antibiotics contraindicated in neonates, and 6.5% could not exercise the correct choice of antibiotics in any of the infections indicated in the questionnaire. Nearly, 90% of them felt the need of continuous education on rational antibiotic use.

The utility of institutional antibiotic policy and regular prescription audit finds regular mention in literature. Fowler et al. investigated the effect of reinforcing a narrow spectrum antibiotic policy by feedback of antibiotic use to doctors as part of a departmental audit and feedback program.[10] The result was a reduction in the use of broad-spectrum drugs such as cephalosporins and co-amoxiclav and increase in the use of targeted narrow spectrum antibiotics such as benzylpenicillin and amoxicillin. Clostridium difficile infection rates also fell.

Gjelstad et al. explored a multifaceted educational intervention in Norway termed prescription peer academic detailing.[11] Trained general practitioners (the prescription peers) conducted outreach visits to participating physicians during which evidence-based recommendations of antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory tract infections (RTI) were presented and software was made available to the participants to capture prescription data. These data were linked to the Norwegian prescription database, and individual feedback was sent to all participating physicians after a year. The antibiotic prescription pattern in RTI improved considerably. Another study by Llor et al. documented significant reduction in rates of antibiotic prescription for common cold among physicians who had access to rapid diagnostic tests such as rapid antigen detection and C-reactive protein coupled with rational antibiotic prescribing guidelines.[12] Such educational interventions and studies regarding their feasibility need to be explored in Indian settings.

Pressure from patients or their relatives for quick recovery is yet another perceived factor behind injudicious use of antibiotics. Trepka et al. described how a community-wide educational intervention increased awareness among parents regarding correct use of antibiotics for pediatric RTI.[13] The parents in the intervention area developed better awareness compared to those in the control area. The number of parents who changed physicians simply because their child was not prescribed antibiotics also diminished.

Antibiotic surveillance in developing countries needs improvement.[14] In India, we urgently need a nationwide surveillance program for monitoring antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance patterns. After the discovery of the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase enzyme, the Indian Government formed a task force to assess and formulate preventive measures against antibiotic resistance.[15] The result is a new addendum to the existing drugs and cosmetics rules 1945 known as “schedule H1” which prohibits over-the-counter sale of antimicrobials such as antitubercular drugs, third generation cephalosporins, newer fluoroquinolones, and recent molecules such as carbapenems, tigecycline, and daptomycin. A system of red color (Rx in red) warning for such drugs is mandated. Pharmacies will not sell them without a prescription and written record in a separate register that is to be open for inspection.

Regarding antibiotic stewardship, Aldeyab et al. reported successful reduction in the use of second and third generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and clindamycin and significant reduction in Clostridium difficile infection rates in a hospital as a result of a high-risk antibiotic stewardship program.[16] Borde et al. also described how a similar program reduced the incidence of nosocomial infections with multidrug-resistant bacteria by reducing rates of prescriptions of third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones.[17]

This study has its share of limitations. Other categories of antimicrobials such as antifungals, antimalarials, and antivirals were not included in the questionnaire. The opinion of clinicians in private setups was not obtained. Furthermore, differences in opinion among various groups of clinicians based on academic seniority and discipline were not assessed. Finally, this survey is based on clinicians’ perceptions and, therefore, the findings may show some discrepancies with actual prescription audit data.

Nevertheless, we can conclude that clinicians acknowledged the misuse of antibiotics as an important problem. They identified the probable risk factors and suggested feasible remedial measures. Their concerns need to be addressed. Proper training of medical students, interns and residents in rational antibiotic use, improvement in microbiology support, implementation of institutional or departmental antibiotic policy, awareness regarding schedule H1 and a system of clinical audit of antibiotic use are pressing needs in Indian teaching hospitals.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.Kunin CM, Liu YC. Excessive use of antibiotics in the community associated with delayed admission and masked diagnosis of infectious diseases. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2002;35:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akande TM, Ologe M, Medubi GF. Antibiotic prescription pattern and cost at university of llorin teaching hospital, llorin, Nigeria. Int J Trop Med. 2009;4:50–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Remesh A, Gayathri AM, Singh R, Retnavally KG. The knowledge, attitude and the perception of prescribers on the rational use of antibiotics and the need for an antibiotic policy-a cross sectional survey in a tertiary care hospital. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:675–9. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5413.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan S, Shehzad A, Shehzad O, Al-Suhaimi EA. Inpatient antibiotics pharmacology and physiological use in Hayatabad medical complex, Pakistan. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2013;5:120–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fadare JO, Tamuno I. Antibiotic self-medication among university medical undergraduates in Northern Nigeria. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2011;3:217–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abasaeed A, Vlcek J, Abuelkhair M, Kubena A. Self-medication with antibiotics by the community of Abu Dhabi Emirate, United Arab Emirates. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:491–7. doi: 10.3855/jidc.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling Oh A, Hassali MA, Al-Haddad MS, Syed Sulaiman SA, Shafie AA, Awaisu A. Public knowledge and attitudes towards antibiotic usage: A cross-sectional study among the general public in the state of Penang, Malaysia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:338–47. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oberoi L, Singh N, Sharma P, Aggarwal A. ESBL, MBL and Ampc ß Lactamases Producing Superbugs-Havoc in the Intensive Care Units of Punjab India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:70–3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/5016.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahin H, Arsu G, Köseli D, Büke C. Evaluation of primary health care physicians’ knowledge on rational antibiotic use. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2008;42:343–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler S, Webber A, Cooper BS, Phimister A, Price K, Carter Y, et al. Successful use of feedback to improve antibiotic prescribing and reduce Clostridium difficile infection: A controlled interrupted time series. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:990–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gjelstad S, Fetveit A, Straand J, Dalen I, Rognstad S, Lindbaek M. Can antibiotic prescriptions in respiratory tract infections be improved? A cluster-randomized educational intervention in general practice– The prescription peer academic detailing (Rx-PAD) study [ NCT00272155] BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:75. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llor C, Hernández S, Cots JM, Bjerrum L, González B, García G, et al. Physicians with access to point-of-care tests significantly reduce the antibiotic prescription for common cold. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2013;26:12–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trepka MJ, Belongia EA, Chyou PH, Davis JP, Schwartz B. The effect of a community intervention trial on parental knowledge and awareness of antibiotic resistance and appropriate antibiotic use in children. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E6. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felmingham D, Feldman C, Hryniewicz W, Klugman K, Kohno S, Low DE, et al. Surveillance of resistance in bacteria causing community-acquired respiratory tract infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;8(Suppl 2):12–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.8.s.2.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad A, Patel I. Schedule H1: Is it a Solution to Curve Antimicrobial Misuse in India? Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:S55–6. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.121228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aldeyab MA, Kearney MP, Scott MG, Aldiab MA, Alahmadi YM, Darwish Elhajji FW, et al. An evaluation of the impact of antibiotic stewardship on reducing the use of high-risk antibiotics and its effect on the incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in hospital settings. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2988–96. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borde JP, Kaier K, Steib-Bauert M, Vach W, Geibel-Zehender A, Busch H, et al. Feasibility and impact of an intensified antibiotic stewardship programme targeting cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone use in a tertiary care university medical center. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]