Abstract

To reconstruct reliable nuclear medicine-related occupational radiation doses or doses received as patients from radiopharmaceuticals over the last five decades, we assessed which radiopharmaceuticals were used in different time periods, their relative frequency of use, and typical values of the administered activity. This paper presents data on the changing patterns of clinical use of radiopharmaceuticals and documents the range of activity administered to adult patients undergoing diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures in the U.S. between 1960 and 2010. Data are presented for 15 diagnostic imaging procedures that include thyroid scan and thyroid uptake, brain scan, brain blood flow, lung perfusion and ventilation, bone, liver, hepatobiliary, bone marrow, pancreas, and kidney scans, cardiac imaging procedures, tumor localization studies, localization of gastrointestinal bleeding, and non-imaging studies of blood volume and iron metabolism. Data on the relative use of radiopharmaceuticals were collected using key informant interviews and comprehensive literature reviews of typical administered activities of these diagnostic nuclear medicine studies. Responses of key informants on relative use of radiopharmaceuticals are in agreement with published literature. Results of this study will be used for retrospective reconstruction of occupational and personal medical radiation doses from diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals to members of the U.S. radiologic technologist’s cohort and in reconstructing radiation doses from occupational or patient radiation exposures to other U.S. workers or patient populations.

Keywords: Nuclear medicine, radiopharmaceutical use, administered activity

INTRODUCTION

Diagnostic imaging used to support medical decision-making experienced explosive growth in the second half of the 20th century and during this interval both diagnostic nuclear medicine and radiology procedures accounted for the bulk of radiation exposure to patients and hospital staff. Numerous epidemiologic studies have been conducted over the last 5 decades on populations exposed to medical radiation and/or other sources of radiation. Some studies have tried to account for personal medical exposures received though doses are almost always difficult to estimate with acceptable reliability for the component of exposure due to radiopharmaceuticals for diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures. The reason for this difficulty is due in part to poor historical information on the diagnostic use of radiopharmaceuticals and reliance upon individuals’ recall of the radiopharmaceuticals and doses to which they may have been exposed. A retrospective analysis was, therefore, performed to fill the gap on the historical use of radiopharmaceuticals to facilitate future assessment of radiation doses to populations whose exposure included diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures.

To this end we will use this data to support an ongoing study by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), a long-term follow-up and cancer risk analysis, of a large cohort of U.S. radiologic technologists (USRT) who worked during the mid to late 20th century. That study focuses on exposures and evaluation of health risks, in particular, the risk of cancer (Boice et al., 1992, Sigurdson et al. 2003, Simon et al. 2006). We are in the process of reconstructing occupational radiation doses to each USRT cohort member (Simon et al. 2006, Simon et al. 2014) as well as radiation doses technologists received as part of their personal medical care. To collect information for accurate assessment of individual doses, we request each USRT cohort member to complete a self-administered questionnaire to specifically report radiopharmaceutical use in their occupational activities or personal exposure radiation (both nuclear medicine and radiology) for medical diagnosis or therapy during the years 1960–2010. A work history questionnaire module has been designed to provide an estimate of the number of times per week each technologist performed or assisted in the performance of diagnostic radioisotope/ radiopharmaceutical procedures during ten year intervals from 1960 through 2010. Here we note that the questionnaire only inquires about the type of radioisotope procedure with which they might have assisted. Although radiopharmaceuticals used for diagnostic imaging and their typical administered activities have markedly changed over the past five decades, we intentionally did not inquire about details of the radiopharmaceuticals since the time period was too long to expect reliable answers. We assumed similar, albeit greater, recall difficulties for technologists who received exposure to radiopharmaceuticals as a patient rather than by occupational exposure.

In order to reconstruct a five-decade history reliable nuclear medicine-related occupational radiation doses and/or radiation doses from radiopharmaceuticals received as patients we needed to assess radiopharmaceuticals use in different time intervals, their relative frequency, and typical administered activities. Published data are limited, and we used information from nationwide surveys of relative use of radiopharmaceuticals and actual administered activities in the United States conducted by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW) in the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s (USDHEW 1968, 1970, 1976). Reports from medical market research companies provided information on the relative frequency of use of radiopharmaceuticals for selected nuclear medicine examinations in the 2000s, for example, for cardiac perfusion studies (IMV 2008). However, we were unable to find sufficient published data on the frequency of use for many of the different radiopharmaceuticals used in other time intervals.

In an attempt to fill this information gap, we collected data on the relative frequency of use of the major radiopharmaceuticals deployed in diagnostic nuclear medicine imaging from interviews of a panel of internationally recognized nuclear medicine practitioners. This paper summarizes the collective information obtained from those interviews that details the use and administered doses of radiopharmaceuticals in the practice of diagnostic nuclear medicine in the U.S. from 1960 through 2010.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Use of radiopharmaceuticals

Key informants interview

To collect data on the relative use of radiopharmaceuticals for diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures in the U.S. in 1960–2010, we conducted a survey of knowledgeable persons who began working in the field of diagnostic imaging in the 1960s through the early 1980s. For the purposes of our data collection effort, these experts served the role as “key informants”. In this data collection, 11 of 40 prominent U.S.-based nuclear medicine experts responded on the survey. The key informants were experts working at large hospitals and medical centers including: Massachusetts General Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, University of Missouri, University of New Mexico Medical Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Veteran Affairs (VA) Hospitals (Ann Arbor, Long Island, Los Angeles, Nashville), and Weill Cornell Medical Center. In completing the questionnaires, key informants were instructed to rely on their own experience and knowledge or archival records of their practice or the medical centers where they were employed.

The questionnaire completed by the key informants included 17 spreadsheets, one for each of the following nuclear medicine procedures: thyroid scan, thyroid uptake study, brain scan, brain blood flow study, lung perfusion study, lung ventilation study, bone scan, liver scan, hepatobiliary scan, bone marrow scan, pancreas scan, kidney scan, cardiac procedures, tumor localization study, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and Meckel’s scan, non-imaging studies of blood volume, and iron metabolism studies. For each procedure, a list of the most frequently used radiopharmaceuticals, as indicated by the literature, was provided. Key informants were asked whether they used each radiopharmaceutical in their practice and to estimate its relative frequency of use in each year from 1960 to 2010. Experts were allowed to add other radiopharmaceuticals if they knew of their use in a particular year(s). The key informants were requested to maintain the total percentage of the relative use of radiopharmaceuticals for given procedures in each year to be equal to 100%. Years of approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for some radiopharmaceuticals as well as an example of a completed table (for instructional purposes) were also provided to the key informants.

Relative use of radiopharmaceuticals

The data collected from the key informants’ responses of the relative use of radiopharmaceuticals (in %) for each diagnostic radioisotope procedure in each year was calculated using eqn (1):

| (1) |

where pk,l,m is the relative use (%) of the m-th radiopharmaceutical in the l-th year for the k-th diagnostic radioisotope procedure; pk,l,m,n is the percentage of use of the m-th radiopharmaceutical in the l-the year for the k-th diagnostic radioisotope procedure reported by the n-th key informant.

Administered activity of radiopharmaceuticals

We also conducted an extensive literature review to collect data on activity of radiopharmaceuticals administered to adult patients in the U.S. during different time intervals. Textbooks on nuclear medicine practice in the U.S. (e.g., Blahd 1965, 1971; Wagner 1968, 1995; Maynard 1969, 1971; Sodee and Early 1972, 1975; Mettler and Guiberteau 1983, 1998, 2012; Kowalsky and Falen 2004) and the U.S. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guidelines (e.g. Becker et al. 1999; Balon et al. 2006a, 2006b; Delbeke et al. 2006) were consulted as major reference sources. We also searched for full-text articles published between the 1960 and 2013 using PubMed, Science Direct, and journals’ web-sites when necessary. In addition, references listed in each publication were used to identify publications not captured by the electronic searches. If the administered activity was given in a reference as a range, a median of that range was assumed to be the typical administered activity.

Radiopharmaceutical-weighted effective dose to patient

Information on the relative use of each radiopharmaceutical and its administered activity for each diagnostic radioisotope procedures was used to calculate a typical radiopharmaceutical-weighted effective dose as follows:

| (2) |

where is the radiopharmaceutical-weighted effective dose to a patient who underwent the k-th diagnostic radioisotope procedure (mSv) in the l-the year; Ak,l,m is the activity of the m-th radiopharmaceutical administered in the l-the year for the k-th diagnostic radioisotope procedure (MBq); DCFm is the effective dose conversion factor, giving the effective dose per unit administered activity of the m-th radiopharmaceutical (mSv MBq−1) (ICRP 1987 , 1998, 2008); Mk,l is the number of radiopharmaceuticals used in the l-the year for the k-th diagnostic radioisotope procedure.

Mixtures of radiopharmaceuticals, except for some protocols like dual isotope cardiac perfusion studies, were generally not administered to the same patient; therefore the typical radiopharmaceutical-weighted effective dose presented here is used only for illustrative purposes. The value from eqn. (2) represents a radiopharmaceutical-weighted average effective dose that reflects the overall mean dose for each procedure type and is used only to evaluate trends in patient radiation exposures over the time period from 1960 through 2010.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes data reported by key informants on the relative use of radiopharmaceuticals for diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures in the U.S. from 1960 through 2010. Although the experts provided estimates for each year, the data are summarized and averages are shown for 5-year periods. Based on literature reports, we also summarize in Table 2, typical administered doses (and ranges) for radiopharmaceuticals used in adult patients in diagnostic nuclear medicine in the U.S. for 5-year intervals. The data for different diagnostic radioisotope procedures are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Table 1.

Relative use (%) of radiopharmaceuticals for diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures in the United States in 1960–2010.

| Radiopharmaceutical | Percentage of use of radiopharmaceuticals for diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures in

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960–1964 | 1965–1969 | 1970–1974 | 1975–1979 | 1980–1984 | 1985–1989 | 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2004 | 2005–2010 | |

| Thyroid scan | ||||||||||

| 131I-sodium iodide | 100 | 88 | 53 | 22 | 19 | 14 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| 123I-sodium iodide | – a | – | 3 | 16 | 22 | 26 | 36 | 49 | 51 | 56 |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | – | 12 | 44 | 62 | 59 | 60 | 54 | 42 | 41 | 36 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Thyroid uptake | ||||||||||

| 131I-sodium iodide | 100 | 92 | 93 | 76 | 67 | 67 | 60 | 55 | 48 | 45 |

| 123I-sodium iodide | – | – | – | 13 | 22 | 22 | 38 | 45 | 52 | 55 |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | – | 8 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 2 | – | – | – |

|

| ||||||||||

| Brain scan | ||||||||||

| 203Hg-chlormerodrin | 81 | 36 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 197Hg-chlormerodrin | 19 | 17 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | – | 47 | 89 | 53 | 33 | 24 | 4 | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-DTPA | – | – | 8 | 43 | 56 | 48 | 35 | 25 | 20 | 18 |

| 99mTc-glucoheptonate | – | – | – | 4 | 11 | 8 | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-HMPAO | – | – | – | – | – | 13 | 39 | 35 | 20 | 19 |

| 99mTc-ECD | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 | 25 | 37 | 35 |

| 201Tl-chloride | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | 1 | – | – | – |

| 18F-FDG | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | 9 | 15 | 23 | 28 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Brain blood flow | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | 9 | 15 | 23 | 28 |

| 131I-RIHSA | 100 | 40 | 15 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | – | 53 | 63 | 42 | 23 | 19 | 3 | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-DTPA | – | 7 | 22 | 55 | 67 | 65 | 50 | 47 | 48 | 48 |

| 99mTc-HMPAO | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 25 | 19 | 11 | 10 |

| 99mTc-ECD | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 17 | 25 | 26 |

| 111In-DTPA | – | – | – | – | 10 | 14 | 20 | 17 | 16 | 16 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lung perfusion | ||||||||||

| 131I-MAA | 100 | 93 | 38 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-MAA | – | 7 | 58 | 77 | 81 | 94 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 99mTc-HAM | – | – | 4 | 19 | 19 | 6 | – | – | – | – |

|

| ||||||||||

| Lung ventilation | ||||||||||

| 133Xe | – | 100 | 100 | 100 | 89 | 74 | 67 | 64 | 37 | 32 |

| 99mTc-DTPA aerosol | – | – | – | – | 11 | 26 | 33 | 36 | 63 | 68 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Bone scan | ||||||||||

| 85Sr-chloride | 100 | 45 | 17 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 85Sr-nitrate | – | 15 | 10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Na18F | – | 25 | 21 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-polyphosphate | – | 15 | 48 | 50 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-MDP | – | – | 4 | 50 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Liver scan | ||||||||||

| 198Au-colloid | 97 | 47 | 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 131I-Rose Bengal | 3 | 18 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-SC | – | 35 | 91 | 100 | 93 | 82 | 84 | 83 | 79 | 78 |

| 99mTc-IDA | – | – | – | – | 7 | 18 | 16 | 17 | 21 | 22 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Hepatobiliary scan | ||||||||||

| 131I-Rose Bengal | – | 100 | 100 | 73 | 16 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-mebrofenin | – | – | – | 20 | 8 | 4 | 1 | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-HIDA | – | – | – | 7 | 76 | 95 | 90 | 84 | 73 | 70 |

| 99mTc-DISIDA | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 9 | 16 | 27 | 30 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Bone marrow scan | ||||||||||

| 198Au-colloid | 100 | 65 | 15 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-SC | – | 35 | 85 | 100 | 98 | 85 | 93 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 99mTc-albumin colloid | – | – | – | – | 2 | 15 | 7 | – | – | – |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pancreas scan | ||||||||||

| 75Se-methionine | 100 | 100 | 80 | 80 | 42 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-SC | – | – | 20 | 20 | 45 | 30 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| 18F-FDG | – | – | – | – | 13 | 70 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Kidney scan | ||||||||||

| 131I-hippurate | – | 41 | 68 | 34 | 27 | 18 | 2 | – | – | – |

| 203Hg-chlormerodrin | 56 | 17 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 197Hg-chlormerodrin | 44 | 42 | 15 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-DTPA | – | – | 16 | 55 | 60 | 61 | 34 | 27 | 5 | 3 |

| 99mTc-glucoheptonate | – | – | 1 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 1 | 5 | 2 | – |

| 99mTc-DMSA | – | – | – | 1 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 4 |

| 99mTc-MAG3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 57 | 59 | 90 | 93 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Cardiac procedures | ||||||||||

| 201Tl-chloride | – | – | 10 | 70 | 67 | 67 | 49 | 30 | 19 | 9 |

| 99mTc-pyrophosphate | – | 100 | 33 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 7 | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | – | – | 35 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-RBC | – | – | 22 | 11 | 20 | 18 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 10 |

| 99mTc-HSA | – | – | – | 7 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 99mTc-sestamibi (1 day) | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 26 | 47 | 53 | 55 |

| 99mTc-sestamibi (2 day) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 99mTc-tetrofosmin | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 7 | 13 | 20 |

| 18F-FDG | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 82Rb-chloride | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 |

|

| ||||||||||

| GI bleeding and Meckel’s scan | ||||||||||

| 99mTc-RBC | – | 100 | 96 | 83 | 92 | 89 | 96 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | – | – | 4 | 17 | 8 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Tumor localization | ||||||||||

| 131I-HSA | 100 | 100 | 71 | 7 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 67Ga-citrate | – | – | 29 | 93 | 100 | 97 | 84 | 50 | 24 | 1 |

| 111In-pentetreotide | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 5 | 11 | 11 |

| 111In-capromab pendetide | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 18F-FDG | – | – | – | – | – | 3 | 15 | 42 | 62 | 87 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Non-imaging studies | ||||||||||

| Blood volume | ||||||||||

| 131I-RIHSA | 62 | 60 | 49 | 31 | 42 | 49 | 46 | 60 | 66 | 83 |

| 51Cr-RBC | 38 | 34 | 41 | 57 | 48 | 41 | 46 | 40 | 34 | 17 |

| 125I-HSA | – | 6 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | – | – | – |

|

| ||||||||||

| Iron metabolism | ||||||||||

| 59Fe-citrate | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | – | – | – |

Use of radiopharmaceutical was not reported for this time period

Table 2.

Typical activity (and range) of radiopharmaceuticals administered to adults for diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures in the United States in 1960–2010.

| Procedure/study | Radiopharmaceutical | Administered activity (MBq)

|

Yearsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical | Range | |||

| Thyroid scan | 131I-sodium iodide | 1.85 | 0.925–2.78 | before 1975 |

| 2.78 | 1.85–3.7 | 1975–1979 | ||

| 3.7 | 2.8–4.4 | after 1980 | ||

| 123I-sodium iodide | 3.7 | 1.85–3.7 | before 1980 | |

| 7.4 | 3.7–11.1 | 1980–1984 | ||

| 11.1 | 7.4–14.8 | 1985–1994 | ||

| 14.8 | 11.1–25 | after 1995 | ||

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | 74 | 37–185 | before 1980 | |

| 185 | 74–222 | 1980–1994 | ||

| 222 | 185–370 | after 1995 | ||

|

| ||||

| Thyroid uptake | 131I-sodium iodide | 0.185 | 0.148–0.222 | before 2000 |

| 0.26 | 0.148–0.37 | after 2000 | ||

| 123I-sodium iodide | 7.4 | 3.7–11.1 | – | |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | 18.5 | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Brain scan | 203Hg-chlormerodrin | 26 | – | – |

| 197Hg-chlormerodrin | 26 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | 463 | 370–555 | before 1970 | |

| 555 | 370–740 | 1970–1975 | ||

| 740 | – | after 1975 | ||

| 99mTc-DTPA | 740 | 370–1110 | – | |

| 99mTc-glucoheptonate | 740 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-HMPAO | 740 | 370–1100 | – | |

| 99mTc-ECD | 740 | 370–1100 | – | |

| 201Tl-chloride | 111 | 74–148 | – | |

| 18F-FDG | 555 | 222–740 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Brain blood flow | 131I-RIHSA | 14.8 | 13.9–18.5 | – |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | 463 | 370–555 | before 1970 | |

| 555 | 370–740 | 1970–1975 | ||

| 740 | – | after 1975 | ||

| 99mTc-DTPA | 740 | 370–1110 | – | |

| 99mTc-HMPAO | 740 | 370–1100 | – | |

| 99mTc-ECD | 740 | 370–1100 | – | |

| 111In-DTPA | 18.5 | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Lung perfusion | 131I-MAA | 11.1 | 7.4–13 | – |

| 99mTc-MAA | 111 | 74–148 | before 1975 | |

| 148 | 111–185 | 1975–1979 | ||

| 185 | 111–222 | after 1980 | ||

| 99mTc-HAM | 111 | 74–148 | before 1985 | |

| 185 | – | after 1985 | ||

|

| ||||

| Lung ventilation | 133Xe | 555 | 370–740 | – |

| 99mTc-DTPA aerosol | 1300b | 1110–1480b | – | |

|

| ||||

| Bone scan | 85Sr-chloride | 3.7 | – | – |

| 85Sr-nitrate | 3.7 | – | – | |

| Na18F | 55.5 | 37–74 | before 1970 | |

| 74 | 37–111 | after 1970 | ||

| 99mTc-polyphosphate | 555 | 370–740 | before 1975 | |

| 740 | – | after 1975 | ||

| 99mTc-MDP | 555 | 370–740 | before 1975 | |

| 740 | – | 1975–1994 | ||

| 925 | 740–1110 | after 1995 | ||

|

| ||||

| Liver scan | 198Au-colloid | 7.4 | 5.55–11.1 | – |

| 131I-Rose Bengal | 0.37 | 0.185–0.65 | before 1965 | |

| 8.3 | 5.55–11.1 | after 1965 | ||

| 99mTc-SC | 74 | 55.5–185 | before 1969 | |

| 111 | 74–185 | 1970–1974 | ||

| 185 | 148–222 | after 1975 | ||

| 99mTc-IDA | 185 | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Hepatobiliary scan | 131I-Rose Bengal | 8.3 | 5.55–11.1 | – |

| 99mTc-mebrofenin | 185 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-HIDA | 185 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-DISIDA | 185 | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Bone marrow scan | 198Au-colloid | 55.5 | 37–74 | – |

| 99mTc-SC | 222 | 74–370 | before 1970 | |

| 444 | 370–555 | 1970–1974 | ||

| 555 | 370–740 | after 1975 | ||

| 99mTc-albumin colloid | 463 | 370–555 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Pancreas scan | 75Se-methionine | 7.4 | 7.4–9.25 | – |

| 99mTc-SC | 185 | – | – | |

| 18F-FDG | 555 | 370–740 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Kidney scan | 131I-hippurate | 9.25 | 3.7–14.8 | – |

| 203Hg-chlormerodrin | 3.7 | – | – | |

| 197Hg-chlormerodrin | 3.7 | – | 1960–1969 | |

| 5.55 | 4.6–7.4 | after 1970 | ||

| 99mTc-DTPA | 370 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-glucoheptonate | 555 | 370–740 | before 1990 | |

| 463 | – | 1990–1994 | ||

| 370 | – | after 1995 | ||

| 99mTc-DMSA | 185 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-MAG3 | 370 | 185–555 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Cardiac procedures | 201Tl-chloride | 111 | 74–148 | before 2000 |

| 148 | 111–185 | after 2000 | ||

| 99mTc-pyrophosphate | 555 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | 370 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-RBC | 740 | – | before 1995 | |

| 833 | 740–925 | 1995–1999 | ||

| 925 | 740–1110 | after 2000 | ||

| 99mTc-HSA | 740 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-sestamibi (1 day) | 1110 | – | – | |

| 99mTc-sestamibi (2 day) | 1480 | 1110–1850 | – | |

| 99mTc-tetrofosmin | 1110 | 740–1480 | – | |

| 18F-FDG | 370 | – | – | |

| 82Rb-chloride | 1850 | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| GI bleeding and Meckel’s scan | 99mTc-RBC | 740 | – | before 1995 |

| 833 | 740–925 | 1995–1999 | ||

| 925 | 740–1100 | after 2000 | ||

| 99mTc-pertechnetate | 185 | – | before 1990 | |

| 370 | – | after 1990 | ||

|

| ||||

| Tumor localization | 131I-HSA | 111 | 74–148 | – |

| 67Ga-citrate | 111 | 74–148 | before 1990 | |

| 148 | 111–185 | 1990–1999 | ||

| 185 | 148–222 | after 2000 | ||

| 111In-pentetreotide | 222 | – | – | |

| 111In-capromab pendetide | 185 | – | – | |

| 18F-FDG | 555 | 370–740 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Non-imaging studies | ||||

| Blood volume | 131I-RIHSA | 0.185 | – | before 1980 |

| 0.28 | 0.185–0.37 | after 1980 | ||

| 51Cr-RBC | 0.37 | – | before 1970 | |

| 0.74 | 0.185–0.925 | 1970–1974 | ||

| 1.11 | – | 1975–1979 | ||

| 1.48 | 1.11–1.85 | after 1980 | ||

| 125I-HSA | 0.28 | 0.185–0.37 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Iron metabolism | 59Fe-citrate | 0.37 | 0.185–0.555 | – |

Years of use is given if administered activity has been changed during entire period of use of radiopharmaceutical that is given in Table 1.

This is the amount that is dispensed and placed into the nebulizer (aerosolizer). However, only about 18.5–37 MBq is administered into the patient’s lungs.

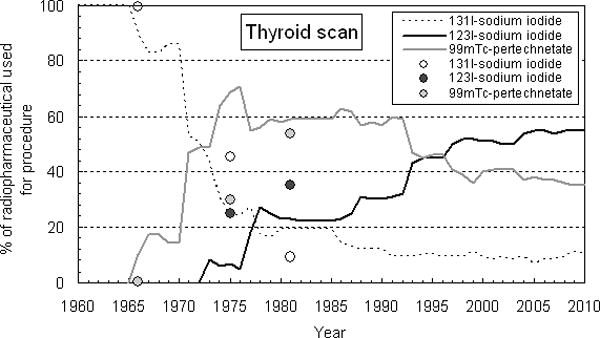

Thyroid scan and thyroid uptake

Historically Iodine-131(131I)-sodium iodide is the standard radiopharmaceutical used for routine thyroid studies since the late 1940s. Other radiopharmaceuticals that have also been used for thyroid studies are technetium-99m (99mTc)-pertechnetate (since the late 1960s) and 123I-sodium iodide (since the mid-1970s). By the beginning of the 2000s, about half of all thyroid scans were performed with 123I-sodium iodide, about 40% used 99mTc-pertechnetate, while less than 10% used 131I-sodium iodide. For thyroid uptake studies, by the late 2000s, 131I-sodium iodide and 123I-sodium iodide were reported by key informants to be used almost equally, 45% and 55%, respectively. In addition to these three radiopharmaceuticals (Table 1), use of 125I-sodium iodide for thyroid imaging was also reported, although it is not shown in Table 1 as it was reported to be only a few percent and was primarily used for research studies conducted in the 1970s and 1980s.

The activity administered radiopharmaceuticals used for thyroid studies to adults (Table 2) varied over the last five decades. The administered activity of 131I-sodium iodide for thyroid imaging before the mid-1970s was about 1.85 MBq (Harper et al. 1965; Wagner 1968; Atkins 1975; McAfee and Subramanian 1984; Drozdovitch et al. 2014), then gradually increased to 3.7 MBq (Sodee and Early 1975; Irwin et al. 1978; Mettler et al. 1986; Sisson 1997). The administered activity of 123I-sodium iodide for thyroid imaging before the late-1970s was estimated to be 3.7 MBq (Robertson 1982; Wagner et al. 1986), then gradually increased to 11.1 MBq in the 1980s (Mettler and Guiberteau 1983, Mettler et al. 1986; Wagner et al. 1995; Park et al. 1994, 1997) and to 14.8 MBq in the mid-1990s (Mettler and Guiberteau 1998; Becker et al. 1999; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Balon et al. 2006a; Joyce and Swihart 2011). The administered activity of 99mTc-pertechnetate for thyroid imaging before the late-1970s was estimated to be 74 MBq (Early et al. 1969; Maynard 1971; Barrall and Smith 1976), then increased to 185 MBq in the 1980s (Mettler et al. 1986; Wagner et al. 1986; NCRP 1996) and to 222 MBq in the mid-1990s (Mettler and Guiberteau 1998; Becker et al. 1999; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Balon et al. 2006a; Joyce and Swihart 2011).

The activity administered to adult patients who underwent thyroid uptake studies is shown in Table 2 (Blahd 1965; Wagner 1968; Maynard 1971; Atkins 1975; USDHEW, 1976; Schneider 1979; Mettler and Guiberteau 1998; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Balon et al. 2006b; Dahnert 2007; NCRP 2009).

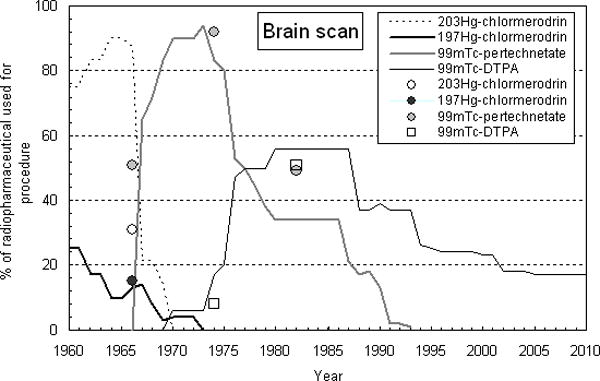

Brain scan

Mercury-203 (203Hg)- and 197Hg-labeled chlormerodrin were the main radiopharmaceuticals used for brain imaging in the 1960s following their introduction by Blau and Bender (1962) and Sodee (1963). By the end of the 1960s, 203Hg-chlormerodrin was replaced with 99mTc-pertechnetate because 203Hg resulted in a high radiation dose to the kidneys due to its beta-radiation and long effective half-time. Mercury-197-chlormerodrin was also used until the early 1970s. Other 99mTc-labeled radiopharmaceuticals that were used for brain imaging were 99mTc-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (99mTc-DTPA) starting in 1970, 99mTc-glucoheptonate (99mTc-GH) during the mid-1970s through the 1980s, 99mTc-hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime (99mTc-HMPAO) since the late 1980s, and 99mTc-ethyl cysteinate diethylester (99mTc-ECD (Neurolite™)) since 1990. Our key informants reported use of 201Tl-chloride for brain imaging only for a short period of time, in the late 1980s through early 1990s. Since the late 1980s, fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) has been used for imaging brain function/metabolism; and its use has progressively increased.

In addition to the radiopharmaceuticals shown in Table 1, use of 123I-iodoamphetamine (123I-IMP) was also reported; however, it is not included in the analysis as it was used only for a few percent of brain scans and for only a short time period. For a number of reasons, including uncertain brain retention mechanisms, inconvenience of use/ supply, and cost, 123I-IMP did not become a routine brain imaging agent (Kowalsky and Falen 2004) and was replaced by 99mTc-HMPAO (Saha et al. 1994).

Activities of radiopharmaceuticals administered to adult patients for brain imaging were the following (Table 2):

-

–

26 MBq of 197, 203Hg-chlormerodin (Silver 1968; Maynard 1971; Sodee and Early 1972; Drozdovitch et al. 2014);

-

–

463 MBq 99mTc-pertechnetate before the early 1970s, then gradually increasing to 555 MBq and to 740 MBq since the mid-1970s (Harper et al. 1965; Maynard 1969; Blahd 1971; O’Mara and Mozley 1971; Ramsey and Quinn 1972; Sodee and Early 1972; Brownell et al. 1974; Fischer and McKusick 1975; Holman 1976; Mettler and Guiberteau 1983, 1998; Mettler et al. 1986; Dahnert 2007);

-

–

740 MBq of 99mTc-DTPA, 99mTc-GH, 99mTc-HMPAO, and 99mTc-ECD (USDHEW, 1976; Robertson 1982; Mettler et al. 1986, 2008a, 2008b; McAfee 1989; Larar and Nagel 1992; Kuni and duCret 1997; Mettler and Guiberteau 1998, 2012; Donohoe et al. 2003a, 2012; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Dahnert 2007; Juni et al. 2009; NCRP 2009; Bonte et al. 2011;);

-

–

111 MBq of 201Tl-chloride (Saha et al. 1994; Kahn et al. 1994; Kowalsky and Falen 2004);

-

–

555 MBq of 18F-FDG (Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Mettler et al. 2008a; Waxman et al. 2009; Mettler and Guiberteau 2012).

Brain blood flow study

Iodine-131 (131I)-radioiodinated human serum albumin (131I-RIHSA), introduced in the 1950s, was the first agent used for brain blood flow studies. 99mTc-labeled radiopharmaceuticals were later used for this purpose. Since the early 1980s 111In-DTPA has been used for cerebrospinal fluid flow studies. According to the key informants (Table 1), by the end of the 2000s, almost half (48%) of brain blood flow studies utilized 99mTc-DTPA, 26% 99mTc-ECD, 16% 111In-DTPA and 10% 99mTc-HMPAO. Use of 99mTc-gluceptate was also reported but not included in the analysis because of a very low frequency of use.

An administered activity of 131I-RIHSA of 14.8 MBq, range 13.9–18.5 MBq, was used for brain imaging that included cerebral blood flow analysis during the 1960s to early 1970s (Wagner 1968; Blahd 1971; Maynard 1971; O’Mara and Mozley 1971; Brownell et al. 1974). The administered activity of 111In-DTPA was 18.5 MBq (Mettler and Guiberteau 1983, 1998; Wagner et al. 1986; Kuni and duCret 1997; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Dahnert 2007; NCRP 2009). The administered activities of 99mTc-labeled radiopharmaceuticals are presented in Table 2.

Lung perfusion study

Iodine-131(131I)-labeled macroaggregated albumin (131I-MAA) was the first agent used for pulmonary perfusion imaging and was introduced in the mid-1960s by Wagner et al. (1964) and Taplin et al. (1964) for use with the rectilinear scanner. In the mid-1970s, it was replaced with 99mTc-MAA, which became a major radiopharmaceutical for pulmonary perfusion imaging using the gamma camera. In the 1970s–1980s, 99mTc-human albumin microspheres (99mTc-HAM) were also used. Since the late 1980s, key informants indicated that 99mTc-MAA was the only agent used for lung perfusion scans (Table 1). 99mTc-iron hydroxide macroaggregates (99mTc-FHMA) were used only to a small degree. Use of 133Xe was also reported but not shown as it was reported to have been used only for research studies during a short time period (1968–1971).

The typical administered activity of 131I-MAA for lung perfusion scanning was 11.1 MBq (Haynie et al. 1965; Wagner 1968; Early et al. 1969; USDHEW, 1970; Blahd 1971; Sodee and Early 1975; Atkins 1975; McAfee and Subramanian 1984). The typical administered activity of 99mTc-MAA was initially 111 MBq (Blahd 1971; Sodee and Early 1975; Neuman et al. 1980) but gradually increased to 185 MBq in the 1980s (Mettler et al. 1986, 2008a; McAfee 1989; Wagner et al. 1995; Kuni and duCret 1997; NCRP 2009; Mettler and Guiberteau 2012; Jafari and Daus 2013).

Lung ventilation study

Because the noble gases are poorly soluble and chemically inert, they are good agents for ventilation imaging. Xenon-133 (133Xe) was first used for evaluation of lung function in the mid-1960s. Because of the low cost of production, 133Xe was the most widely used agent for lung ventilation studies until the late 1970s. Development of techniques for radio-aerosol ventilation systems in the early 1980s (Hayes et al. 1979) led to introduction of 99mTc-DTPA aerosol for lung studies. According to the key informants in our study, about two-thirds of the studies were conducted using of 99mTc-DTPA as the lung ventilation agent since 2000, the remainder were performed with 133Xe (Table 1). Use of other noble gases for lung ventilation imaging was limited by cost shielding requirements (127Xe) and short half-life of the 81Rb parent of 81mKr. Both of these agents were excellent choices for evaluation of lung ventilation, but costly and availability limited their use. Use of 127Xe and 81mKr to a small extent was reported, but not included in Table 1.

Typical administered activities of radiopharmaceuticals used for lung ventilation imaging were: 555 MBq for 133Xe (Robertson 1982; Mettler et al. 1983; Wagner et al. 1986, 1995; Mettler and Guiberteau 1998; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Dahnert 2007); and 1110–1480 MBq†††† for 99mTc-DTPA aerosol (Wellman 1986; McAfee 1989; Sandler et al. 1996; Mettler and Guiberteau 1998, 2012; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Mettler et al. 2008a; NCRP 2009; Parker et al. 2012).

Bone scan

Strontium-85 (85Sr)-chloride and 85Sr-nitrate were the main radiopharmaceuticals for bone imaging in the 1960s. In the mid-1960s – mid-1970s, 18F-sodium fluoride (Na18F) was also used for bone imaging using rectilinear scanners. Technetium-99m bone-scan agents, i.e., 99mTc-polyphosphate and 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate (99mTc-MDP), were introduced in the early 1970s (Subramanian et al. 1972, 1975) and replaced Na18F with the advent of the Anger camera. Since the early 1980s, 99mTc-MDP has been used to conduct all bone scans, except PET. Use of 87mSr-chloride, 99mTc-ethane hydroxydiphosphonate (99mTc-EHDP), 99mTc-hydroxymethylene diphosphonate (99mTc-HDP) and 99mTc-hydroxyethylidene diphosphonate (99mTc-HEDP) for bone imaging were also reported by the key informants. These radiopharmaceuticals are not shown in Table 1 as their usage was very low (a few percent or less) and for only a short period of time.

The typical administered activity of 85Sr-chloride and 85Sr-nitrate was 3.7 MBq (Wagner 1968; Ronai et al. 1968; Early et al. 1969; Maynard 1969, 1971; USDHEW, 1970; Sodee and Early 1972; Anderton et al. 1975; Atkins 1975; Leventhal et al. 1980; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Drozdovitch et al. 2014). The typical administered activities of 99mTc-phosphate and 99mTc-MDP were 555 MBq before the mid-1970s (Sodee and Early 1972, 1975; Subramanian et al. 1975; USDHEW, 1976; Barrall and Smith 1976), increased to 740 MBq in the 1980s (Kelly et al. 1979; Robertson 1982; Mettler and Guiberteau 1983; Mettler et al. 1986; Wagner et al. 1986; Gertz et al. 1987), and to 925 with range 740–1110 MBq for 99mTc-MDP by the mid-1990s (Mettler and Guiberteau 1998, 2012; Donohoe et al. 2003b; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; NCRP 2009; Segall et al. 2010; Brenner et al. 2012; Frank et al. 2012).

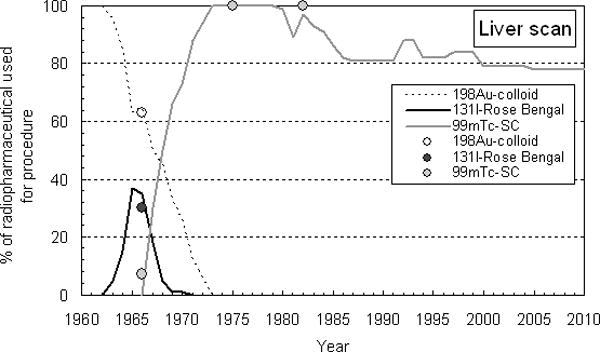

Liver scan

Iodine-131-Rose Bengal and 198Au-colloid were the first agents for liver imaging using rectilinear scanners in the 1950s–1960s. In 1964, 99mTc-sulfur colloid (99mTc-SC) was introduced clinically by Harper et al. (1964) and quickly became the preferred radiopharmaceutical for liver, spleen and bone marrow imaging. According to the responses from key informants, from 80 to 100% of liver scans were performed using 99mTc-SC beginning in the early 1970s. Since the early 1980s, 99mTc-iminodiacetic acid (99mTc-IDA), which has been used primarily in gallbladder studies, was reported to be used in a small fraction of examinations to characterize the liver as well. Our key informants also reported the use of 99mTc-macroaggregated albumin (99mTc-MAA) and 99mTc-albumin colloid for liver imaging. They were reported to be used infrequently in the 1980s–1990s in tumor related cases (not shown in Table 1).

The typical administered activity of 131I-Rose Bengal was 0.37 MBq in the early 1960s to evaluate liver function by measuring the rate of its blood clearance (Beierwaltes 1957; Blahd et al. 1958) while higher activities 8.33 MBq were used for imaging studies (Wagner 1968; Silver 1968; Maynard 1969, 1971; USDHEW, 1970; Blahd 1971; Sodee and Early 1972; Atkins 1975; Leventhal et al. 1980). The typical administered activity of 198Au-colloid was 7.4 MBq with range of 5.55–11.1 MBq (Wagner 1968; Silver 1968; Maynard 1969; Early et al. 1969; USDHEW, 1970; Blahd 1971; Atkins 1975; Sodee and Early 1972; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Drozdovitch et al. 2014). The typical administered activity of 99mTc-SC was 74 MBq in the late 1960s (Harper et al. 1965; Wagner 1968; Silver 1968; Early et al. 1969; Maynard 1969; USDHEW, 1970; Blahd 1971; Atkins 1975), gradually increasing to 185 MBq in the late 1970s (Mettler and Guiberteau 1983, 1998; Mettler et al. 1986; Wagner et al. 1986, 1995; Royal et al. 2003; Jafari and Daus 2013). The typical administered activity of 99mTc-IDA is 185 MBq (Mettler and Guiberteau 1983; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Dahnert 2007).

Hepatobiliary scan

Iodine-131-Rose Bengal was the first agent used for hepatobiliary imaging in the 1960s to early 1970s. In the mid-1970s 99mTc-mebrofenin was introduced. According to key informants, since the early 1980s, the majority of hepatobiliary studies have been conducted with 99mTc-hepatoiminodiacetic acid (99mTc-HIDA). More recently, since the early 1990s, 99mTc-labeled diisopropyliminodiacetic acid (99mTc-DISIDA) has been used for hepatobiliary scintigraphy.

The typical administered activity of 131I-Rose Bengal in the mid-1960s to mid-1980s was 8.33 MBq. The same typical administered activity of 99mTc-labeled radiopharmaceuticals of 185 MBq is used for hepatobiliary imaging according the (Mettler and Guiberteau 1983, 1998, 2012; Mettler et al. 1986, 2008b; Wagner et al. 1986, 1995; Kowalsky and Falen 2004).

Bone marrow scan

Bone marrow scanning is typically conducted with particulate agents, radio-colloids. The first available tracer, 198Au-colloid, was used until the early 1970s. At that time it was replaced with 99mTc-SC which is still used today for the majority of bone marrow scans. Along with 99mTc-SC, 99mTc-albumin colloid was used in up to 15% of scans in the mid-1980s. Our key informants also reported use of 111In-chloride, 111In-SC and 59Fe. These radiopharmaceuticals are not shown in Table 1 as they were rarely used and mostly for research studies.

The typical administered activity of 198Au-colloid was 55.5 MBq with a range from 37 to 74 MBq (Warner 1968; Maynard 1971). A wide range of administered activities, from 74 to 370 MBq, was reported in the early literature for use of 99mTc-SC (Harper et al. 1965; Maynard 1971). By the mid-1980s, the typical administered activity of 99mTc-SC gradually increased to 555 MBq (Sodee and Early 1975; Robertson 1982; Wagner et al. 1995) with a range from 370 to 740 MBq (Mettler and Guiberteau 1998; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; NCRP 2009).

Pancreas scan

Selenium-75 (75Se)-methionine was the only radiopharmaceutical for functional imaging of the pancreas until the early 1970s, when 99mTc-SC was used to image the pancreas/liver border. According to our key informants, in the 1990s and 2000s, a majority (75%) of pancreas scans were conducted using 18F-FDG PET (Table 1) in order to detect pancreatic cancer. Typical administered activities of radiopharmaceuticals for pancreas imaging were 7.4 MBq of 75Se-methionine (Haynie et al. 1964; Sodee and Early 1975); 185 MBq of 99mTc-SC (Azadi et al. 2012); and 555 MBq of 18F-FDG.

Kidney scan

Mercury (197Hg and 203Hg)-labeled chlormerodrin, introduced by Reba et al. (1962a, 1962b), was the main radiopharmaceutical for renal imaging in the 1960s. The key informants reported a wide use of 131I-iodohippurate for renal imaging in the mid-1960s to mid-1980s. By the early 1970s, 197Hg- and 203Hg-chlormerodrin were replaced primarily by 99mTc-DTPA and, to a lesser degree, by 99mTc-glucoheptonate (99mTc-GH). Starting the early 1980s, 99mTc-dimercaptosuccinic acid (99mTc-DMSA) was used for renal cortical imaging. From the beginning of the 1990s, 99mTc-mercaptoacetyltriglycine (99mTc-MAG3) became the major radiopharmaceutical used for renal imaging; more than 90% of kidney scans were performed using this agent. Use of 123I-Iodohippurate and 99mTc-pertechnetate for renal imaging was also reported, but results are not shown in Table 1. Because of high costs, 123I-Iodohippurate was used only infrequently (around 1%) for a short time. 99mTc-pertechnetate was not a favored renal agent and was used infrequently for a short period of time.

The typical administered activity of 197Hg- and 203Hg-chlormerodrin in the 1960s was 3.7 MBq and 5.55 MBq of 197Hg-chlormerodrin in the 1970s (Reba et al. 1962a; Blahd 1965; Wagner 1968; Silver 1968; Maynard 1969; USDHEW, 1970, 1976; Atkins 1975; Sodee and Early 1975; Leventhal et al. 1980). The typical administered activity of 131I-iodohippurate was 9.25 MBq (Mettler and Guiberteau 1983, 1998; Mettler et al. 1986). Typical administered activities of 99mTc-DTPA and 99mTc-GH varied between 370 MBq and 555 MBq; while the typical administered activities of 99mTc-DMSA and 99mTc-MAG3 were 185 MBq and 370 MBq, respectively (Enlander et al. 1974; USDHEW, 1976; Shanahan and Klingensmith 1981; Robertson 1982; Mettler and Guiberteau 1983, 1998, 2012; Schultz et al. 1985; Ziessman et al. 1987; Setaro et al. 1991; Barbaric 1994; Wagner et al. 1995; Mandell et al. 1999; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Dahnert 2007; Mettler et al. 2008a; 2008b; NCRP 2009; Jafari and Daus. 2013).

Cardiac procedures

Radiopharmaceuticals used in cardiac procedures depend on the clinical indication(s) for the procedure. In the late-1960s to early 1990s, 99mTc-pyrophospate was used as infarct-avid agent. Since the early 1970s 99mTl-thallous chloride has been used as a favored myocardial imaging agent, while 99mTc-RBC was used as blood-pool marker. In the late 1980s to early 1990s, 99mTc-sestamibi and 99mTc-tetrofosmin were introduced as perfusion agents for SPECT and 18F-FDG was used as a metabolic PET tracer. In the 2000s, 82Rb-chloride and 13N-ammonia were introduced as a perfusion and myocardial imaging agent for PET. According to the key informants (Table 1), by the end of the 2000s, most of cardiac studies (88%) involved myocardial imaging using 99mTc-sestamibi (59% of cardiac studies), 99mTc-tetrofosmin (20%), with diminishing numbers of 99mTl-thallous chloride (9%). The reminder of cardiac imaging was for blood-pool studies using 99mTc-RBC (10%) and myocardial PET imaging with 18F-FDG (1%) and 82Rb-chloride (1%).

The typical administered activity of 99mTl-thallous chloride was 111 MBq (Mettler et al. 1986; Saha et al. 1992, 1996; NCRP 1996; Mettler and Guiberteau 1998; Bushberg et al. 2002; Kowalsky and Falen 2004), which increased in the late 1990s to 148 MBq (Holly et al. 2010; Frank et al. 2012; Jafari and Daus 2013). The administered activity of 99mTc-tetrofosmin was 1110 MBq, 1110 MBq of 99mTc-sestamibi for the one-day protocol and 1480 MBq for the two-day protocol (NCRP 1996; Mettler and Guiberteau 1998, 2012; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Mettler et al. 2008a, 2008b, Strauss et al. 2008; Holly et al. 2010; Dorbala et al. 2013). For administered activity of other cardiac agents see Table 2 (Early et al. 1969; Sodee and Early 1975; Barrall and Smith 1976; USDHEW 1976; Pavel et al. 1977; Robertson 1982; Mettler et al. 1986; Wagner et al. 1986; 1995; Mettler and Guiberteau 1998, 2012; Scheiner et al. 2002; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Di Carli and Lipton 2007; Mettler and Guiberteau 2012; Dorbala et al. 2013).

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and ectopic gastric mucosa localization (Meckel’s) scan

The most frequently used method in more than 90% of procedures between 1965 and 2010 has been 99mTc-labeled red blood cells (99mTc-RBC) scintigraphy for detecting GI bleeding through visualization of extravasated tracer from the blood pool. Technetium-99m-pertechnetate was used for the detection of Meckel’s diverticulum. The typical administered activity of 99mTc-RBC was 740 MBq (McKusick et al. 1981; Orecchia et al. 1985; Wagner et al. 1986; Smith et al. 1987; McAfee 1989; Suzman et al. 1996; Mettler and Guiberteau 1983, 1998) increasing in the 2000s to 740–1110 MBq (Ford et al. 1999; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Olds et al. 2005; Mettler et al. 2008a; NCRP 2009; Mellinger et al. 2011; Mettler and Guiberteau 2012). The typical administered activity of 99mTc-pertechnetate was 185 MBq (Robertson 1982; Wagner et al. 1986), increasing to 370 MBq in the beginning of 1990s (Mettler and Guiberteau 1998; Ford et al. 1999; Kowalsky and Falen 2004).

Tumor localization

Iodine-131-HSA was reported as the first tumor-imaging agent in the 1960s to early 1970s. In the early 1970s, 67Ga-galluim citrate was introduced for tumor-localization and was widely deployed until the 2000s. Since the 1990s, 111In-labeled radiopharmaceuticals, in particular 111In-pentetreotide and 111In-capromab pendetide (ProstaScint™), have been used as tumor imaging agents. Starting in the late 1990s, the majority of tumor localization scans were conducted by PET imaging with 18F-FDG – almost 90% in 2005–2010. Use of 99mTc-WBC, 111In- satumomab pendetide (OncoScint™), 131I-labelled carcinoembryonic antigen (131I-CEA), and 201Tl was also reported. The latter are not shown in Table 1 as they were used at a low level for a short period of time, some of them mainly for research studies.

The typical administered activity of 131I-HSA to adult patients was 111 MBq (Sodee and Early 1975; USDHEW, 1976). The typical activity of 67Ga-citrate administered to adult patients was initially 111 MBq (Sodee and Early 1975; USDHEW, 1976; Mettler et al. 1986; Wagner et al. 1986, 1995; Bernier et al. 1989; McAfee 1989), gradually increasing to 148 MBq in the early 1990s and to 185 MBq by the early 2000s (Kuni and duCret 1997; Mettler and Guiberteau 1998; Bushberg et al. 2002; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Palestro et al. 2004a; Jafari and Daus 2013). The typical administered activity to adult patients of 111In-pentetreotide and 111In-capromab pendetide was 222 MBq and 185 MBq, respectively (Schirmera et al. 1995; Giles et al. 1997; Kuni and duCret 1997; Mettler and Guiberteau 1998, 2012; Petronis et al. 1998; Sinha and Freeman 1998; Raj et al. 2002; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Manyak 2008; Mettler et al. 2008a; Jafari and Daus 2013). The administered activity of 18F-FDG to adults varied from 370 MBq (Kuni and duCret 1997; Keyes et al. 1997) to 740 MBq (Mettler and Guiberteau 1998) with typical values of 555 MBq (Coleman 1998; Schelbert et al. 1999; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Delbeke et al. 2006; Joyce and Swihart 2011; Mettler and Guiberteau 2012).

Blood volume study

Blood volume studies were reported in the 1960s using two primary tracers: 131I-RIHSA (60–62%) (plasma volume) and 51Cr-RBC (34–38%) (red-cell volume). In the mid-1960s, 125I-HSA was introduced and used for the studies through the mid-1990s. Blood volume studies were done less frequently after the 1990s. The administered activity of 131I-RIHSA was 0.185 MBq in the 1960s–1980s (Maynard 1969; Atkins 1975; Leventhal et al. 1980), later increasing to 0.28 MBq. The administered activity of 51Cr-RBC was 0.37 MBq in the 1960s (Wagner 1968), gradually increasing to 1.48 by the early 1980s (Kowalsky and Falen 2004). The administered activity of 125I-HSA was 0.28 MBq (Wagner 1968; Maynard 1969; Kowalsky and Falen 2004; Dworkin et al. 2007).

Iron metabolism study

Iron metabolism studies were reported during the 1960s to mid 1990s using 59Fe-citrate as the primary tracer. The administered activity of 59Fe-citrate was 0.37 MBq, range 0.185–0.555 MBq (Wagner 1968; Early et al. 1969; Maynard 1971; Atkins 1975; Leventhal et al. 1980).

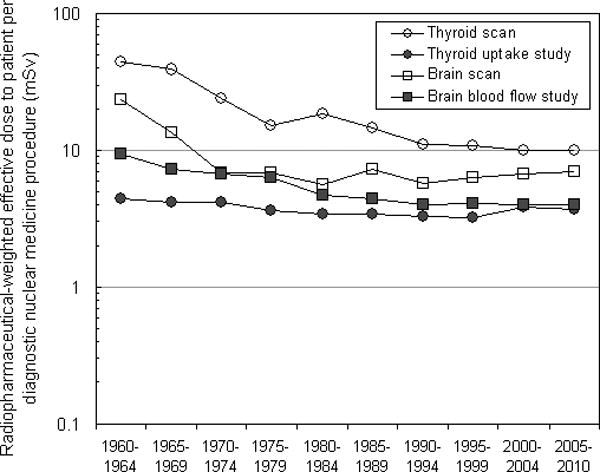

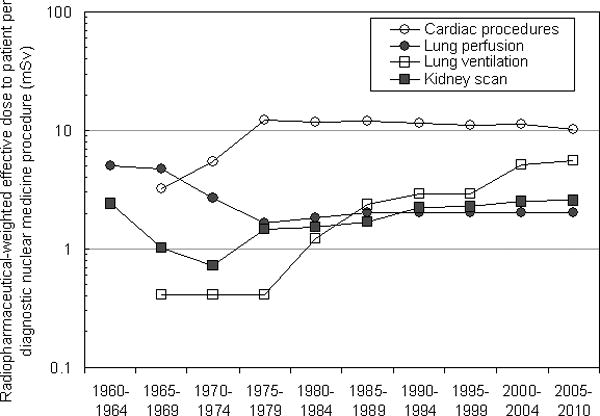

Typical effective dose to patient

Fig.1 shows trends in the typical radiopharmaceutical-weighted effective dose to patients (calculated using eqn (2)) from different diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures over the time period from 1960 through 2010. As can be seen from the figure, in the early 1960s, the typical radiopharmaceutical-weighted effective dose to patients was the highest for tumor localization studies (71 mSv), bone marrow imaging (61 mSv), thyroid scans (44 mSv), and brain scans (24 mSv). The radiopharmaceutical-weighted effective doses to patients from these procedures decreased substantially (12 times for bone marrow imaging) as 198Au-colloid (bone marrow imaging), 131I-labeled agents (tumor localization, thyroid scan) and 203Hg- and 197Hg-chlormerodrin (brain scan) were replaced by the early 1970s with 67Ga-citrate (tumor localization), 99mTc-labeled radiopharmaceuticals (bone marrow scan, brain scan, thyroid scan) and 123I-sodium iodide (thyroid scan). The decreasing trend with time of the weighted effective dose is not characteristic of all nuclear medicine procedures. Use of 99mTc-labeled radiopharmaceuticals since the 1970s–1980s led to an increase of the radiopharmaceutical- weighted effective dose to patients who underwent lung function studies (by a factor of 13) and renal imaging (by a factor of 3). By the end of 2000s, the weighted effective dose to patients varied between 2 and 11 mSv for all diagnostic imaging procedures considered here. It should be noted that the effective dose conversion factors for some radiopharmaceuticals, including 123I- and 131I-sodium iodide, 131I-Rose Bengal, 197Hg- and 204Hg-chlormerodrin, and 198Au-colloid, given in ICRP Publication 53 (1987) were not updated in ICRP Publication 80 (1998) and, therefore, they do not include changes in values of the tissue weighting factors introduced by ICRP Publication 60 (1991).

Fig. 1.

Trend in radiopharmaceutical-weighted effective dose to patients from diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures over time period from 1960 through 2010: a) thyroid scan, thyroid uptake study, brain scan, and brain blood flow study; b) liver, hepatobiliary, and pancreas scan, GI bleeding study and Meckel’s scan; c) cardiac imaging procedures, lung perfusion study, lung ventilation study, and kidney scan; d) bone scan, bone marrow scan, tumor localization study, blood volume study, and iron metabolism study.

As can be seen from Table 2 for some diagnostic radioisotope procedures such as bone scans and GI bleeding studies, the typical administered activity of 99mTc has increased during the past 15–20 years. Higher administered activities allow shorter image acquisition times, thus enhancing patient convenience and compliance, and, to some extent, image quality. Higher administered activities also increased the efficiency of the nuclear medicine facility and made it possible to conduct more studies. Of course, the drawback to this practice is the higher radiation dose to patients (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

Comparison with other studies

We compared the relative use of radiopharmaceuticals in diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures reported by key informants with a literature-based description of relative use (USDHEW 1968, 1976; Parker et al. 1984; Mettler et al. 1986). The only radiopharmaceuticals that can be compared with literature data are shown in Figs. 2–4, for example, 99mTc-glucoheptonate, 99mTc-HMPAO, 99mTc-ECD, 201Tl-chloride and 18F-FDG are not shown for brain scanning as literature data on the frequency of their use were not found.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of relative use of radiopharmaceuticals for liver imaging in the U.S. in 1960–2010 reported by key informants (lines) and in literature (circles).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of relative use of radiopharmaceuticals for thyroid imaging in the U.S. in 1960–2010 reported by key informants (lines) and in literature (circles).

As can be seen from Fig. 2, there is good agreement between the results of nationwide surveys in 1966 and 1974–1975 and our study on radiopharmaceuticals used for liver imaging. According to the DHEW survey (USDHEW 1968) in 1966, 198Au-colloid was used for 63% of liver scans compared to 65% reported by key informants; 131I-Rose-Bengal was used for 30% of liver scans compared to 35% reported by key informants; and 99mTc-SC was used in 7% of scans. Our key informants did not report the use of 99mTc-SC in 1966, but reported a frequency of use of 30% in 1967. The DHEW survey (USDHEW 1976) reported that 100% of liver scans were conducted using 99mTc-SC in 1974–1975; the same was reported by key informants. Mettler et al. (1986) reported that in 1982 in the U.S. 99mTc-SC was used for all liver scans while the key informants reported 97%.

Good agreement was also observed between the results of nationwide surveys in 1966 and 1974–1975 and our study on radiopharmaceuticals used for brain imaging (Fig. 3). DHEW (USDHEW 1968) reported that 15% of brain scans were conducted using 197Hg, 31% used 203Hg, and 51% used 99mTc-pertechnetate. According to our study, a very similar relative usage was observed in 1967: 14% of brain scans were conducted using 197Hg, 21% using 203Hg, and 65% using 99mTc-pertechnetate. The DHEW survey (USDHEW 1976) also reported that 92% of brain scans were conducted using 99mTc-pertechnetate and 8% using 99mTc-DTPA in 1974–1975. The key informants’ responses indicated a similar pattern in 1974: 83% for 99mTc-pertechnetate, 17% for 99mTc-DTPA and 3% for 197Hg. Mettler et al. (1986) reported that in 1982 in the U.S., 99mTc-pertechnetate and 99mTc-DTPA were used equally for brain imaging. According to our study, 99mTc-pertechnetate was used in 34% of scans and 99mTc-DTPA for 56%.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of relative use of radiopharmaceuticals for brain imaging in the U.S. in 1960–2010 reported by key informants (lines) and in literature (circles).

Agreement between the literature data and the key-informant data is not as good for thyroid scans (Fig. 4). The DHEW survey (USDHEW 1976) reported that in 1974–1975 45% of thyroid scans were conducted using 131I-sodium iodide, 25% using 123I-sodium iodide, and 30% – with 99mTc-pertechnetate. The key informants indicated a different frequency of use in 1974: 24% for 131I-sodium iodide, 7% for 123I-sodium iodide, and 69% for 99mTc-pertechnetate. For the year 1981 agreement is better, Parker et al. (1984) reported that 9% of thyroid scans were conducted using 131I-sodium iodide (vs 19% reported in this study), 35% with 123I-sodium iodide (vs 23% in this study), and 54% with 99mTc-pertechnetate (vs 59% in this study).

Although there were some differences between literature data and responses from key informants, on the whole we believe that the results of our study adequately reflect usage patterns of radiopharmaceuticals for diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures in the U.S.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, our study is the first to summarize historical information on the relative use of radiopharmaceuticals and administered activities in diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures in the U.S. over the relatively long time period between 1960 and 2010. Published data on this topic are limited by the data from the U.S. nationwide surveys done in the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s. To collect historical information we successfully conducted interviews among nuclear medicine experts from major nuclear medicine facilities across the U.S.

There are, however, some obvious limitations of our study. As is clear, we have relied on memory recall of experts and this, in itself, imposes some limitations on precision. Second, the number of experts was limited and their combined experience may not include all circumstances where radiopharmaceuticals were used. In particular, the data presented may not completely reflect the practices and usage in the large number of smaller hospitals and larger volume practices across the U.S. Some radiopharmaceuticals might not have even been reported by key informants or their reported use may not be representative of all facilities or facility types.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

We collected information for 15 diagnostic imaging radioisotope procedures: thyroid scan, thyroid uptake, brain scan, brain blood flow, lung perfusion and ventilation, bone, liver, hepatobiliary, bone marrow, pancreas and kidney scans, cardiac imaging procedures, tumor localization studies, localization of GI bleeding, and non-imaging studies of blood volume and iron metabolism. Data on relative use of radiopharmaceuticals were collected by means of key informant interviews and comprehensive literature review of administered activities.

We evaluated trends in the typical effective dose to patients from different diagnostic nuclear medicine procedures over the time period from 1960 through 2010. In general, for the majority of procedures the typical effective dose to patients decreased substantially (up to 12 times) from the 1960s through the 2000s. However, since the 1970s–1980s typical effective doses to patients who underwent lung function studies and renal imaging increased. By the end of 2000s, the typical effective dose to patients varied between 2 and 11 mSv for all diagnostic imaging procedures considered in this study.

Data on the relative use of radiopharmaceuticals and their typical administered activities that were collected in this study will be used for retrospective reconstruction of occupational and personal medical radiation doses from diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals to members of the U.S. radiologic technologists cohort and in reconstructing radiation doses from occupational or patient radiation exposures to other U.S. workers or patient populations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, NCI, NIH. Special thanks are to Dr. Fred A. Mettler Jr. (New Mexico VA Health Care System, Albuquerque, NM) for his participation in survey and for comments on our manuscript.

Footnotes

This is the amount that is dispensed and placed into the nebulizer (aerosolizer). However, only about 18.5–37 MBq is administered into the patient’s lungs.

References

- Anderton NS, Monroe L, Burdine JA. Clinical appraisal of a new lyophilized Tc stannous pyrophosphate kit for skeletal imaging. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124(4):625–629. doi: 10.2214/ajr.124.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins HL. Radiopharmaceuticals. Physics Report (Section C of Physics Letters) 1975;21(6):315–367. [Google Scholar]

- Azadi J, Subhawong A, Durand DJ. F-18 FDG PET/CT and Tc-99m sulfur colloid SPECT imaging in the diagnosis and treatment of a case of dual solitary fibrous tumors of the retroperitoneum and pancreas. J Radiol Case Rep. 2012;6(3):32–37. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v6i3.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DV, Charkes ND, Hurley JR, McDougall IR, Price DC, Royal HD, Sarkar SD, Dworkin HJ. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guideline for thyroid scintigraphy version 2.0. 1999 Feb 7; Available at http://interactive.snm.org/docs/pg_ch05_0403.pdf. Accessed 5 February 2014.

- Balon HR, Silberstein EB, Meier DA, Charkes ND, Sarkar SD, Royal HR, Donohoe KJ. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guideline for thyroid scintigraphy. 2006a Sep 10; Available at http://interactive.snm.org/index.cfm?PageID=772. Accessed 5 February 2014.

- Balon HR, Silberstein EB, Meier DA, Charkes ND, Sarkar SD, Royal HR, Donohoe KJ. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guideline for thyroid uptake measurement. Version 3.0. 2006b Sep 5; Available at http://interactive.snm.org/index.cfm?PageID=772. Accessed 5 February 2014.

- Barbaric ZL. Principles of genitourinary radiology. 2. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barrall RC, Smith SI. Personnel radiation exposure from 99mTc radiation. In: Kereiakes JG, Corey KR, editors. Biophysical aspects of the medical use of technetium-99m, AAPM Monograph No. 1. New York: American Association of Physics in Medicine; 1976. pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beierwaltes W. Clinical use of radioisotopes. Philadelphia, London, Toronto: W.B. Saunders Company; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier DR, Christian PE, Langan JK, Wells LD, editors. Nuclear medicine technology and techniques. St Louis, Toronto, Baltimore: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Blahd WH, Bauer FK, Cassen B. The practice of nuclear medicine. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Blahd WH, editor. Nuclear medicine. New York: Blakiston Division: McGraw-Hill Inc; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Blahd WH, editor. Nuclear medicine. 2. New York: Blakiston Division: McGraw-Hill Inc; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Blau M, Bender MA. Radiomercury (Hg-203) labeled Neohydrin: A new agent for brain tumor localization. J Nucl Med. 1962;3:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Boice JD, Jr, Mandel JS, Doody MM, Yoder RC, McGowan R. A health survey of radiologic technologists. Cancer. 1992;69:586–598. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920115)69:2<586::aid-cncr2820690251>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonte FJ, Hynan L, Harris TS, White CL., III Tc-99m HMPAO brain blood flow imaging in the dementias with histopathologic correlation in 73 patients. Int J Molec Imaging. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/409101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner AI, Koshy J, Morey J, Lin C, DiPoce J. The bone scan. Semin Nucl Med. 2012;42:11–26. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell GL, Correia JA, Hoop B., Jr Scintillation scanning of the brain. Annu Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1974;3:365–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.03.060174.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushberg JT, Seibert JA, Leidholdt EM, Boone JM. The essential physics of medical imaging. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RE. Clinical PET in oncology. Clinical positron imaging. 1998;1(1):15–30. doi: 10.1016/s1095-0397(97)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahnert WF. Radiology review manual. 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Delbeke D, Coleman RE, Guiberteau MJ, Brown ML, Royal HD, Siegel BA, Townsend DW, Berland LL, Parker JA, Hubner K, Stabin MG, Zubal G, Kachelriess M, Cronin V, Holbrook S. Procedure guideline for tumor imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT 1.0. SNM; 2006. Available at http://interactive.snm.org/index.cfm?PageID=772. Accessed 5 February 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carli MF, Lipton MJ, editors. Cardiac PET and PET/CT imaging. New York: Spring Science + Business Media LLC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dorbala S, Di Carli MF, Delbeke D, Abbara S, DePuey EG, Dilsizian V, Forrester J, Janowitz W, Kaufmann PA, Mahmarian J, Moore SC, Stabin MG, Shreve P. SNMMI/ASNC/SCCT guideline for cardiac SPECT/CT and PET/CT 1.0. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(8):1485–1507. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.105155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe KJ, Brown ML, Collier BD, Carretta RF, Henkin RE, O’Mara RE, Royal HD. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guideline for bone scintigraphy. Version 3.0. SNM; 2003a. Approved June 20, 2003. Available at http://interactive.snm.org/index.cfm?PageID=772. Accessed 5 February 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe KJ, Frey KA, Gerbaudo VH, Mariani G, Nagel JS, Shulkin BL. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guideline for brain death scintigraphy. Version 1.0. SNM; 2003b. Approved February 25, 2003. Available at http://interactive.snm.org/index.cfm?PageID=772. Accessed 5 February 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe KJ, Agrawal G, Frey KA, Gerbaudo VH, Mariani G, Nagel JS, Shulkin BL, Stabin MG, Stokes MK. SNM practice guideline for brain death scintigraphy 2.0. J Nucl Med Technol. 2012;40(3):198–203. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.112.105130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drozdovitch V, Brill AB, Mettler FA, Jr, Beckner WM, Goldsmith SJ, Gross MD, Hays MT, Kirchner PT, Langan JK, Reba RC, Smith GT, Bouville A, Linet MS, Melo DR, Lee C, Simon SL. Nuclear medicine practices in the 1950s through the mid 1970s and occupational radiation doses to technologists from diagnostic radioisotope procedures. Health Phys. 2014;107(4):300–310. doi: 10.1097/HP.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin HJ, Premo M, Dees S. Comparison of red cell and whole blood volume as performed using both Chromium-51–tagged red cells and Iodine-125–tagged albumin and using I-131–tagged albumin and extrapolated red cell volume. Am J Med Sci. 2007;334(1):37–40. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3180986276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early PJ, Razzak MA, Sodee DB. Textbook of nuclear medicine technology. Saint Louis: CV Mosby Company; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Enlander DE, Weber PM, dos Remedios LV. Renal cortial imaging in 35 patients: superior quality with 99mTc-DMSA. J Nucl Med. 1974;15:743–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer KC, McKusick KA, Pendergrass HP, Potsaid MS. Improved brain scan specificity utilizing 99mTc-pertechnetate and 99mTc(Sn)-Diphosphonate. J Nucl Med. 1975;16(8):705–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford PV, Bartold SP, Fink-Bennett DM, Jolles PR, Lull RJ, Maurer AH, Seabold JE. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guideline for gastrointestinal bleeding and Meckel’s diverticulum scintigraphy. Version 1.0. SNM; 1999. Approved February 7, 1999. Available at http://interactive.snm.org/index.cfm?PageID=772. Accessed 5 February 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank ED, Long BW, Smith BJ. Merrill’s atlas of radiographic positioning and procedures, Volume 3 12th Edit. Saint Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gertz MA, Brown ML, Hauser MF, Kyle RA. Utility of technetium Tc-99m pyrophosphate bone scanning in cardiac amyloidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(6):1039–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles FJ, Waxman AD, Nguyen KN, Fuerst MP, Kusuanco DA, Franco MM, Bierman H, Lim SW. Comparison of Technetium-99m sestamibi and Indium-111 octreotide imaging in a patient with Ewing’s sarcoma before and after stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 1997;15(80, 12 Suppl):2478–2483. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971215)80:12+<2478::aid-cncr19>3.3.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper PV, Lathrop K, Richards P. Tc99-m as radiocolloid. J Nucl Med. 5(382):1964. [Google Scholar]

- Harper PV, Lathrop KA, Jiminez F, Fink B, Gottschalk A. Technetium 99m as a scanning agent. Radiology. 1965;85:101–109. doi: 10.1148/85.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie TP, Svaboda AC, Zuidema GD. Diagnosis of pancreatic disease by photoscanning. J Nucl Med. 1964;5:90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie TP, Hendrick CK, Schreiber MH. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism and infraction by photoscanning. J Nucl Med. 1965;6:613–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holly TA, Abbott BG, Al-Mallah M, Calnon DA, Cohen MC, DiFilippo FP, Ficaro EP, Freeman MR, Hendel RC, Jain ID, Leonard SM, Nichols KJ, Polk DM, Soman P. Single photon-emission computed tomography. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17(5):941–973. doi: 10.1007/s12350-010-9246-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman BL. Concepts and clinical utility of the measurement of cerebral blood flow. Semin Nucl Med. 1976;6(3):233–251. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(76)80007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMV Medical Information Division Inc. 2008 nuclear medicine market summary report. Des Plaines, IL: IMV Medical Information Division Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ICRP. Radiation dose to patients from radiopharmaceuticals. (ICRP Publication 53).Ann ICRP. 1987;18:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICRP. 1990 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. (ICRP Publication 60).Ann ICRP. 1991;21:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICRP. Radiation dose to patients from radiopharmaceuticals. (Addendum 2 to ICRP Publication 53. ICRP Publication 80).Ann ICRP. 28(3):1998. doi: 10.1016/s0146-6453(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICRP. Radiation dose to patients from radiopharmaceuticals. (Addendum 3 to ICRP Publication 53. ICRP Publication 106).Ann ICRP. 2008;38:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin RS, Braman SS, Arvanitidis AN, Milton A, Hamolsky W. 131l Thyroid scanning in preoperative diagnosis of mediastinal goiter. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(1):73–74. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari ME, Daus AM. Applying image gentlySM and image wiselySM in nuclear medicine. The Radiation Safety J. 2013;104(1):S31–S36. doi: 10.1097/HP.0b013e3182764cd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JM, Swihart A. Thyroid: Nuclear medicine update. Radiol Clin N Am. 2011;49:425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juni JE, Waxman AD, Devous MD, Sr, Tikofsky RS, Ichise M, Van Heertum RL, Carretta RF, Chen CC. Procedure guideline for brain perfusion SPECT using 99mTc radiopharmaceuticals 3.0. SNM; 2009. Available at http://interactive.snm.org/index.cfm?PageID=772. Accessed 5 February 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn D, Follett KA, Bushnell DL, Nathan MA, Piper JG, Madsen M, Kirchner PT. Diagnosis of recurrent brain tumor: Value of 201Tl SPECT vs 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET. Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:1459–1465. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.6.7992747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RJ, Chilton H, Hackshaw BT, Ball JD, Watson NE, Kahl FR, Cowan FJ. Comparison of Tc-99m pyrophosphate and Tc-99m methylene diphosphonate in acute myocardial infarction: concise communication. J Nucl Med. 1979;20(5):402–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes JW, Jr, Watson NE, Jr, Williams DW, 3rd, Greven KM, McGuirt WF. FDG PET in head and neck cancer. Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169(6):1663–1669. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.6.9393187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalsky RJ, Falen SW. Radiopharmaceuticals in nuclear pharmacy and nuclear medicine. 2. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kuni CC, duCret RP. Manual of nuclear medicine imaging. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Larar GN, Nagel JS. Technetium-99m-HMPAO cerebral perfusion scintigraphy: Considerations for timely brain death declaration. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:2209–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal L, Melgard R, Claridge DE, Kendricks H. Assessment of radiopharmaceuticals usage release practices by eleven Western hospitals. In: Kelly JJ, editor. Effluent and environment radiation surveillance. ASTM STP 698. American Society for Testing and Materials; 1980. pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mandell GA, Cooper JA, Leonard JC, Majd M, Miller JH, Parisi MT, Sfakianakis GN. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guideline for diuretic renography in children. Version 2.0. 1999 Feb 7; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manyak MJ. Indium-111 capromab pendetide in the management of recurrent prostate cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8(2):175–181. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard CD. Clinical nuclear medicine. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard CD. Clinical nuclear medicine. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- McAfee JG, Subramanian G. Radioactive agents for imaging. In: Freeman LM, Johnson PM, editors. Clinical radionuclide imaging. Vol. 1. Orlando, FL: Crune and Straffon Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McAfee JG. Update on radiopharmaceuticals for medical imaging. Radiology. 1989;171:593–601. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.3.2654998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKusick KA, Froelich J, Callahan RJ, Winzelberg GG, Strauss HW. 99mTc red blood cells for detection of gastrointestinal bleeding: experience with 80 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137(6):1113–1118. doi: 10.2214/ajr.137.6.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellinger JD, Bittner JG, 4th, Edwards MA, Bates W, Williams HT. Imaging of gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91(1):93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettler FA, Jr, Guiberteau MJ. Essentials of nuclear medicine imaging. Orlando, FL: Grune & Stratton Inc.; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mettler FA, Jr, Christie JH, Williams AG, Moseley RD, Jr, Kelsey CA. Population characteristics and absorbed dose to the population from nuclear medicine: United States – 1982. Health Phys. 1986;50(5):619–628. doi: 10.1097/00004032-198605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettler FA, Jr, Guiberteau MJ. Essential of nuclear medicine imaging. 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mettler FA, Jr, Huda W, Yoshizumi TT, Mahesh M. Effective doses in radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine: a catalog. Radiology. 2008a;248(1):254–263. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettler FA, Jr, Bhargavan M, Thomadsen BR, Gilley DB, Lipoti JA, Mahesh M, McCrohan J, Yoshizumi TT. Nuclear medicine exposure in the United States: 2005–2007. Semin Nucl Med. 2008b;38:384–391. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettler FA, Jr, Guiberteau MJ. Essential of nuclear medicine imaging. 6. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- NCRP. Sources and magnitude of occupational and public exposures from nuclear medicine procedures. Bethesda, MD: National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements; 1996. (NCRP Report No. 124). [Google Scholar]

- NCRP. Ionizing radiation exposure of the population of the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements; 2009. (NCRP Report No. 160). [Google Scholar]

- Neuman RD, Sostman HD, Gottschalk A. Current status of ventilation-perfusion imaging. Sem Nucl Med. 1980;10(3):198–217. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(80)80002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds GD, Cooper GS, Chak A, Sivak MV, Jr, Chitale AA, Wong RC. The yield of bleeding scans in acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39(4):273–277. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155131.04821.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mara RE, Mozley JM. Current status of brain scanning. Semin Nucl Med. 1971;1(1):7–30. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(71)81025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orecchia PM, Hensley EK, McDonald PT, Lull RJ. Localization of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Experience with red blood cells labeled in vitro with technetium Tc 99m. Arch Surg. 1985;120(5):621–624. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390290095016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palestro CJ, Brown ML, Forstrom LA, Greenspan BS, McAfee JG, Royal HD, Schauwecker DS, Seabold JE, Signore A. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guideline for gallium scintigraphy in inflammation Version 3.0. SNM; 2004a. approved June 2, 2004. Available at http://interactive.snm.org/index.cfm?PageID=772. Accessed 5 February 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palestro CJ, Brown ML, Forstrom LA, McAfee JG, Royal HD, Schauwecker DS, Seabold JE, Signore A. Society of Nuclear Medicine procedure guideline for 111In-Leukocyte scintigraphy for suspected infection/inflammation Version 3.0. SNM; 2004b. approved June 2, 2004. Available at http://interactive.snm.org/index.cfm?PageID=772. Accessed 5 February 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey RG, Quinn JL., III Comparison of accuracy between initial and delayed 99mTc-pertechnetate brain scans. J Nucl Med. 1972;13(2):131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HM, Perkins OW, Edmondson JW, Schnute RB, Manatunga A. Influence of diagnostic radioiodines on the uptake of ablative dose of Iodine-131. Thyroid. 1994;4(1):49–54. doi: 10.1089/thy.1994.4.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HM, Park YH, Zhou X. Detection of thyroid remnant/metastasis without stunning: an ongoing dilemma. Thyroid. 1997;7:277–280. doi: 10.1089/thy.1997.7.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker TW, Mettler FA, Jr, Christie JH, Williams AG. Radionuclide thyroid studies: a survey of practice in the United States in 1981. Radiology. 1984;150:547–550. doi: 10.1148/radiology.150.2.6318261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JA, Coleman RE, Grady E, Royal HD, Siegel BA, Stabin MG, Sostman HD, Hilson AJW. SNM practice guideline for lung scintigraphy 4.0. J Nucl Med Technol. 2012;40(1):57–65. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.111.101386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavel DG, Zimmer AM, Patterson VN. In vivo labeling of red blood cells with 99mTc: A new approach to blood pool visualization. J Nucl Med. 1977;18:305–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronis J, Fintan R, Ke L. Indium-111 capromab pendetide (ProstaScint) imaging to detect recurrent and metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 1998;23(10):672–677. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199810000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj GV, Partin AW, Polascik TJ. Clinical utility of indium 111-capromab pendetide immunoscintigraphy in the detection of early, recurrent prostate carcinoma after radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2002;94(4):987–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reba RC, Wagner HN, Jr, McAfee JG. Measurement of 203Hg chlormerodrin accumulation by the kidneys for detection of unilateral renal disease. Radiology. 1962a;79:134–135. doi: 10.1148/79.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]