Abstract

Patient: Female, 81

Final Diagnosis: Liver absces

Symptoms: Diarrhea • jaundice • vomiting • weakness

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: CT scan guided drainage

Specialty: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Clostridium perfringens is an unusual pathogen responsible for the development of a gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess. Progression to septicemia with this infection has amplified case fatality rates.

Case Report:

We report a case of an 81-year-old lady with pyogenic liver abscess with gas formation that was preceded by an acute gastroenteritis. The most common precipitating factors are invasive procedures and immunosuppression. Clostridium perfringens was unexpectedly isolated in the drained abscess, as well as blood. It is a normal inhabitant of the human bowel and a common cause of food poisoning, notoriously leading to tissue necrosis and gas gangrene.

Conclusions:

We report a case of gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess and bacteremia progressing to fatal septic shock, caused by an uncommon Clostridium perfringens isolate.

MeSH Keywords: Clostridium perfringens; Gas Gangrene; Liver Abscess, Pyogenic

Background

Pyogenic liver abscess is a critical disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clostridium perfringens is an unusual pathogen responsible for the development of gas-forming pyogenic liver abscesses. Progression to septicemia with this infection has amplified case fatality rates.

Case Report

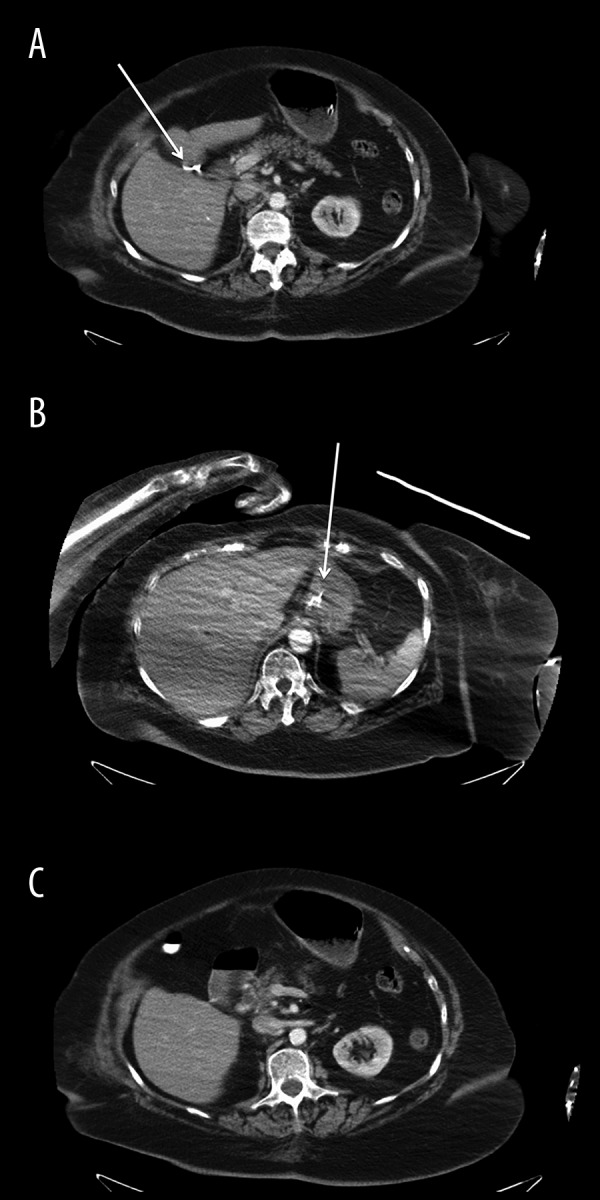

We report a case of an 81-year-old Greek lady who was brought to the emergency department with complaints of vomiting and diarrhea starting a few days before. The patient had previous cerebrovascular stroke, for which she was being treated with aspirin and clopidogrel. She was prescribed anti-depressant medications: Paroxetine, Clonazepam, and Olanzapine. She used fesoterodine for overactive bladder. Other medications included atorvastatin, levetiracetam, levothyroxine, and lisinopril and laxatives as needed. She has relevant surgical history of cholecystectomy performed 10 years ago and a remote history of thyroidectomy. On physical exam, she was febrile and icteric. Rest of the exam was unremarkable. Laboratory work revealed leukocytosis and transaminitis. Viral hepatitis panel was negative. Unfortunately, stool culture was not obtained as diarrhea had already resolved promptly at the beginning of hospitalization. The patient had an esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy for evaluation of dysphagia and positive occult blood in stool, which was unrevealing except for antral hernia. Colonoscopy was deferred for outpatient follow-up. Ultrasound abdomen and CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast showed a 2-mm punctate focus of calcification was found within the right hepatic lobe, which may be a small calcified granuloma. A 5-mm low-attenuation lesion was found within the right hepatic lobe, too small to further characterize (Figure 1A–1C). The patient improved and diagnosis of an acute self-limited gastroenteritis was hypothesized without any need for further treatment with antibiotics.

Figure 1.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast (A) Liver: The liver is mildly enlarged measuring up to 18.1 cm along the mid-clavicular plane. A 2 mm punctate focus of calcification is present within the right hepatic lobe which may represent a small calcified granuloma. Mild hepatomegaly is noticed. A 5 mm low-attenuation lesion is present within the right hepatic lobe (white arrow). (B) A 5 mm low-attenuation lesion (white arrow) is present within the right hepatic lobe as seen which is too small to further characterize. Further evaluation of the hepatic parenchyma is difficult due to streak artifact from the patient’s bilateral upper extremities. (C) Biliary tree: The distal CBD is mildly dilated, measuring up 1.0 cm in diameter. Pancreas: Moderate pancreatic parenchymal atrophy is present diffusely. An enteric tube is present with its distal tip visualized in the stomach. Exophytic left mid pole renal cyst. The patient is status post cholecystectomy. The distal CBD is mildly dilated, measuring up to 1.0 cm in diameter, which is at the upper limits of normal for post-cholecystectomy state.

Five days later, her condition worsened and she was brought to the hospital in a state of lethargy, fever, and deep jaundice. She was hypotensive and tachycardic with a BP of 87/29 mm hg. Rapid workup demonstrated leukocytosis with a WBC of 22×109/L. In addition, serum creatinine was 1.89 μmol/L and BUN was 17.5 mmol/L. Liver function progressively deteriorated from her recent hospitalization. AST was 318 U/L, ALT 231 U/L, ALP 494 U/L, and bilirubin total 7.2 µmol/L /direct 5.6 µmol/L. Diagnosis of septic shock was made.

Intravenous fluids were initiated, in addition to empirical antibiotics (cefepime, metronidazole, and vancomycin). The patient was transferred to the ICU, and was intubated thereafter for respiratory distress, then was started on mechanical ventilation.

She had uncontrolled hyperglycemia, although she was not a known diabetic. One month ago her last HBA1C was 5.7%. On treatment with 3 vasopressors, no incremental response was seen. A CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis without contrast (due to worsening kidney functions) established the presence of a 9.9×9.9 cm area of low attenuation in the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe, containing mostly air (Figure 2). On blood cultures, Clostridium perfringens, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus faecalis (Group D Streptococcus) were isolated. The patient underwent a CT-guided aspiration of the hepatic abscess. Dark venous blood (120 cc) was aspirated along with foul-smelling air. The aspirate was cultured and was found to have the same organisms that were isolated from the blood. A percutaneous drain was left in situ. Antibiotics were switched to vancomycin and meropenem (IV) and empirical fluconazole IV. The patient failed to recover; eventually palliative care and terminal weaning were resorted to.

Figure 2.

CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis without intravenous or oral contrast. Liver: In the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe there was a 9.9×9.9 cm area of low attenuation containing mostly air. Foci of air were seen in the anterior hepatic space. Small amount of subcapsular air was seen. White arrows points to free air produced from the liver abscess. Scattered areas of free air were present in Peritoneum, Omentum and Retroperitoneum. Gallbladder and Biliary System: The patient is status post cholecystectomy. There was no evidence of appendicitis or diverticulitis. Pulmonary parenchyma: There was a consolidation right lower lobe. Pleura: There were small bilateral pleural effusions. Bones: Multiple left-sided rib fractures were visualized. Lymph nodes: Evaluation of lymphadenopathy was difficult in the absence of intravenous contrast.

Discussion

Liver abscesses are the most common type of visceral abscess; pyogenic liver abscesses account for 48% of visceral abscesses and 13% of intra-abdominal abscesses [1]. The annual incidence of liver abscess has been estimated at 2.3 cases per 100,000 population and is higher among men than women, indicating it is still an uncommon disease [2]; higher rates have been reported in Taiwan [3].

Bacterial pathogens causing liver abscess are usually mixed and depend on the precipitating cause. Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and other Gram-positive cocci are seen after invasive liver procedures like trans-arterial embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma [4]. Hepato-splenic candidiasis can occur in patients after chemotherapy [2]. Diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance are the most common risk factors for Klebsiella primary liver abscess (KLA) [5–8]. Hyperglycemia is an important factor for GFPLA (gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess). Poor control of DM leads to neutrophil dysfunction and chemotaxis failure. Local tissue damage is caused by gas-forming bacteria and compounded by the diabetic micro-angiopathy [9]. Our reported patient had uncontrolled hyperglycemia that could be from stressful the disease process. Uncommon organisms could cause liver abscess, like tuberculous [8] and amebic liver [11] in endemic areas.

Mixed infections may be found in 14–55% of cases of routine pyogenic liver abscesses, but KLA cases are almost uniformly mono-bacterial [14,17]. Prior to the era of rapid patient assessment and expeditious surgery, appendiceal pathology was the most common source of liver abscesses [12,13]. In the modern era, biliary disease is the most common etiology [12,15]. Other potential sources include penetrating trauma, distant sources (i.e., outside the abdomen), and contiguous spread from lung, kidney, colon, or stomach. Still, many are deemed cryptogenic (40–99%) [12,14].

GFPLA (gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess) accounts for 7–32% of PLA (pyogenic liver abscess) cases. It was reported in one of the studies that of the 69 patients included who had PLA, 22 had GFPLA, and 21 had DM. K. pneumonia was the most common pathogen of PLA, which accounts for 70% of GFPLA [14,15].

Most common pathways through which bacteria can reach the liver and start forming the abscess is through the portal venous system, hepatic artery, biliary tract, and direct spread. Among these, the biliary tract is the most frequent source, occurring in 60% of PLA cases [14].

A report of 52 cases treated at a single institution showed that the pathogenesis of liver abscesses in one group of patients was mainly malignant biliary obstruction and spontaneous or iatrogenic necrosis of primary hepatic neoplasms with superimposed bacterial infection. In contrast, the pathogeneses of the abscesses in the second group of patients included portal venous suppuration secondary to colorectal cancer, post-gastrectomy for gastric cancer, and hepatic artery seeding with uncertain infectious nidi following systemic anticancer treatment [16]. Pyogenic liver abscess can be a presentation of underlying hepato-pancreato-biliary malignant disease at a pre-terminal stage and carries a grave prognosis. In contrast, patients who have pyogenic liver abscess and non-malignant disease have a favorable outcome [16].

As regards our case, no malignancy was identified from history or on work-up done, including the CT abdomen. Unfortunately, colonoscopy was not done on either admission to exclude malignancy.

The major presenting symptoms were fever, chills, and abdominal pain; however, a few patients presented with only altered mental status, dizziness, or general malaise [17].

Recently, the introduction and refinement of percutaneous drainage techniques have dramatically improved the treatment success rate [18]. However, these refined techniques seemed not to influence the outcome of critically ill patients with PLA in one study [19]. Given that most patients in that study had severe sepsis, treatment not only should have focused on a local inflammation or infection, but also should have regulated a systemic, complex immunologic reaction [19].

Among patients with PLA, the incidence of septic shock and bacteremia is higher in GFPLA patients compared to non-GFPLA patients. Septic shock is noted in 32.5% of patients with GFPLA and in 11.7% of patients with PLA patients [20]. GFPLA also has a high fatality rate, which is around 27.7% to 37.1%. GFPLA also ruptures easily because of tissue invasion and fragility of abscess wall, and further gas formation increases the internal pressure of the abscess. In previous studies, spontaneous rupture of PLA had occurred in 7.1–15.1% of the cases and 20 of 24 patients with ruptured PLA had GFPLA [17,21,22]. Clostridium perfringens is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped, anaerobic, spore-forming bacterium of the genus Clostridium [20]. It is part of the intestinal normal flora in humans and known to cause tissue necrosis and gas gangrene by producing alpha toxin [23]. It is common cause of food-borne diseases in the USA [24].

After a literature review, only a few cases were found to have gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess secondary to C. perfringens. One of them occurred spontaneously in an immune-competent patient with intravascular hemolysis [25]. Another case was reported after pancreatectomy [26]. The third one was reported after laparoscopic cholecystectomy [27].

Conclusions

Our reported case is a presentation of gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess with mixed bacteria, but we wish to emphasize C. perfringens, which is rare without an invasive procedure or immunosuppression. Bacterial seeding could happen from the GI tract to the liver, causing liver abscess. Our patient developed septic shock with multi-organ system failure and with no signs of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy or intravascular hemolysis.

Footnotes

Learning objective

Liver abscess can be a serious life-threatening condition. Treatment should be very early and aggressive, which usually includes appropriate antibiotics and surgical drainage. Clostridium perfringens is one of the uncommon organisms involved.

Statement

There is no conflict of interest regarding the case report. Financial funding is self-funding.

References:

- 1.Altemeier WA, Culbertson WR, Fullen WD, Shook CD. Intra-abdominal abscesses. Am J Surg. 1973;125(1):70–79. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(73)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang CJ, Pitt HA, Lipsett PA, et al. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. Changing trends over 42 years. Ann Surg. 1996;223(5):600–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199605000-00016. discussion 607–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai FC, Huang YT, Chang LY, Wang JT. Pyogenic liver abscess as endemic disease, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(10):1592–600. doi: 10.3201/eid1410.071254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C, Chen PJ, Yang PM, et al. Clinical and microbiological features of liver abscess after transarterial embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(12):2257–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang JH, Liu YC, Lee SS, et al. Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(6):1434–38. doi: 10.1086/516369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang CC, Yen CH, Ho MW, Wang JH. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscess caused by non-Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37(3):176–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan KS, Chen CM, Cheng KC, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess: a retrospective analysis of 107 patients during a 3-year period. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2005;58(6):366–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fung CP, Chang FY, Lee SC, et al. A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis? Gut. 2002;50(3):420–24. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong VH, Yong A, Wahab AY. Gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess. Singapore Med J. 2008;49(5):e123–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everts RJ, Heneghan JP, Adholla PO, Reller LB. Validity of cultures of fluid collected through drainage catheters versus those obtained by direct aspiration. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(1):66–68. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.66-68.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aikat BK, Bhusnurmath SR, Pal AK, et al. The pathology and pathogenesis of fatal hepatic amoebiasis. A study based on 79 autopsy cases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979;73(2):188–92. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KT, Wong SR, Sheen PC. Pyogenic liver abscess: An audit of 10 years’ experience and analysis of risk factors. Dig Surg. 2001;18(6):459–65. doi: 10.1159/000050194. discussion 465–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miedema BW, Bineen P. The diagnosis and treatment of pyogenic liver abscesses. Ann Surg. 1984;200(3):328–35. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198409000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HL, Lee HC, Guo HR, et al. Clinical significance and mechanism of gas formation of pyogenic liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(6):2783–85. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2783-2785.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen W, Chen CH, Chiu KL, et al. Clinical outcome and prognostic factors of patients with pyogenic liver abscess requiring intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1184–88. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31816a0a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh TS, Jan YY, Jeng LB, et al. Pyogenic Liver Abscesses in Patients with Malignant Disease. A Report of 52 Cases Treated at a Single Institution. Arch Surg. 1998;133(3):242–45. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong WM, Wong BC, Hui CK, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess: Retrospective analysis of 80 cases over a 10-year period. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17(9):1001–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng DL, Liu YC, Yen MY, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess: Clinical manifestations and value of percutaneous catheter drainage treatment. J Formos Med Assoc. 1990;89(7):571–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siu WT, Chan WC, Hou SM, Li MK. Laparoscopic management of ruptured pyogenic liver abscess. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1997;7(5):426–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan KJ, Ray CG, editors. Sherris Medical Microbiology. 4th ed. McGraw Hill; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou FF, Sheen-Chen SC, Chen YS, Lee TY. The comparison of clinical course and results of treatment between gas-forming and non-gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess. Arch Surg. 1995;130(4):401–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430040063012. discussion 406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Treating patients with severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(3):207–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. http://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu//bionumber.aspx?id=105474&ver=1.

- 24.Shandera WX, Tacket CO, Blake PA. Food poisoning due to Clostridium Perfringens in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1983;147(1):167–70. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajendran G, Bothma P, Brodbeck A. Intravascular haemolysis and septicaemia due to Clostridium perfringens liver abscess. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38(5):942–45. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1003800522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonatti H, Cejna M, Hartmann G, et al. Clostridium perfringens liver abscess after pancreatic resection. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2009;10(2):159–62. doi: 10.1089/sur.2008.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qandeel H, Abudeeb H, Hammad A, et al. Clostridium perfringens sepsis and liver abscess following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012(1):5. doi: 10.1093/jscr/2012.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]