Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

Key Words: dry eye, rebamipide, diquafosol, eye drops, mucin, chronic graft-versus-host disease, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid

ABSTRACT

Purpose

Two new drugs with mucin-inducing and secretion-promotive effects, rebamipide and diquafosol, were recently approved as topical dry-eye treatments. We report two cases in which the long-term use of mucin-inducing eye drops improved chronic ocular graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD)–related dry eye and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP)-like disease.

Case Reports

Case 1. A 61-year-old woman had cGVHD-related dry eye that resisted traditional medications. Next, we use topical diquafosol in addition to conventional treatments. The patient used diquafosol for 6 months without experiencing any side effects. The symptoms, including dry-eye sensation, ocular pain, foreign body sensation, and photophobia, as well as ocular surface findings including fluorescein and rose bengal scores and tear break-up time (TBUT), partly improved. To further improve the clinical signs and symptoms and decrease chronic inflammation, rebamipide was added to diquafosol. The symptoms, TBUT, and fluorescein and rose bengal scores markedly improved after long-term dual treatment without any side effects for 6 months. Case 2. A 77-year-old woman had OCP-like disease with dry eye. The patient did not improve using the currently available conventional treatments. Next, we use topical rebamipide in addition to conventional treatments. Symptoms including asthenopia, dry-eye sensation, ocular pain, and dull sensation, as well as fluorescein and rose bengal scores and TBUT, partly improved. Specifically, functional visual acuity was markedly improved after commencement of rebamipide. To further improve the clinical signs and symptoms and increase tear film stability and tear film volume, diquafosol was added to rebamipide. The combination of diquafosol and rebamipide worked for the patient. Improvements were seen in several symptoms, fluorescein and rose bengal scores, Schirmer test value, and TBUT without any side effects for 12 months.

Conclusions

Long-term treatment with topical rebamipide and diquafosol can improve dry eye in patients with cGVHD or OCP-like disease.

Dry-eye disease is a multifactorial disorder of the tear film and ocular surface involving tear deficiency, excessive tear evaporation, and tear instability.1 One of the causes of tear film instability is an ocular surface disturbance resulting from mucin dysfunction, which can occur in Sjögren syndrome (SS), ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP), and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).2,3 Although several therapies have been developed to relieve the signs and symptoms of dry eye, some dry-eye patients do not respond to conventional eye drops. Recently, new mucin-related drugs have been approved for treating dry eye: diquafosol ophthalmic solution (3% Diquas; Santen Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan)4,5 and rebamipide (Mucosta ophthalmic suspension UD2%; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).6,7 These new eye drops have increased the therapeutic options for dry-eye patients.

Diquafosol is a dinucleotide, purinoreceptor P2Y2 receptor agonist. It stimulates P2Y2 receptors at the ocular surface, promoting tear secretion and inducing mucin secretion through elevated intracellular Ca++ concentrations.8 Mucin helps to maintain the wetness of the ocular surface, and its underproduction causes several types of dry-eye disease. In addition to maintaining hydration and lubrication of the epithelial surface, diquafosol repairs the damaged epithelial barrier through improving the functions of mucin for this disease.2

Rebamipide is a mucosal protective medicine.9,10 It increases gastric endogenous prostaglandins E2 and I2 to promote gastric epithelial mucins, which scavenge oxygen free radicals and have other anti-inflammatory actions. Rebamipide’s biological effects include cytoprotection, wound healing, and inflammation prevention9,11 in a variety of tissues as well as gastrointestinal mucosa.10,12 With respect to dry eye, rebamipide promotes the healing of corneal and conjunctival injuries by increasing secretion of both membrane-associated and secreted-type mucins. Rebamipide has been approved for treatment of dry eye in Japan since January 2012 and is being developed for this use in the United States.

Several studies have reported the effectiveness of administration of diquafosol eye drops, which appear to be effective for SS, tear film instability, and the short tear break-up time (TBUT) type of dry eye.4,5,13 However, there is no information about the effects of long-term treatment with rebamipide and/or diquafosol eye drops for specific disease-associated dry-eye conditions including those associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) and OCP (see Supplement Digital Content 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/OPX/A201).

Chronic GVHD–related dry-eye disease is a major late complication after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation that affects a patient’s visual function and quality of life.14,15 Other target organs of cGVHD include the mouth, skin, liver, lung, and intestine.15,16 The pathogenic process of cGVHD-related dry eye involves ocular surface and lacrimal gland dysfunction resulting from inflammation and immune-mediated fibrosis.17 In particular, previous reports suggest that mucin expression was reduced by the ocular surface epithelia in cGVHD-related dry eye.3,18 On the other hand, OCP is a rare autoimmune disease, characterized by a linear deposition of immunoglobulin on the conjunctival basement membrane and blistering on the mucous membrane, including the conjunctiva.19 In this disease, sight is threatened because of conjunctival inflammation, fibrosis, and corneal and conjunctival epitheliopathy.19

Here, we describe and discuss two cases of dry-eye disease. One is associated with cGVHD, and the other, with OCP-like disease. They were treated effectively with the long-term use of a combination of rebamipide and diquafosol eye drops.

Because cGVHD-related dry eye and OCP affect the mucosal membrane on the ocular surface, including mucin expression and the morphology of the ocular surface epithelia, we reasoned that the mucin-related effects on tear stability by both medicines, the increased water production by diquafosol, and the anti-inflammatory effect of rebamipide might be synergic. Our findings indicated that these two medicines may be effective for treatment of certain subclasses of dry-eye disease in which the dry eye is assessed to be mild to moderate.1

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 61-year-old woman was diagnosed as having cGVHD at another hospital. She underwent bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy for malignant lymphoma in August 1997. She had also received an allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplant and radiotherapy in November 1998. Afterward, she was treated systemically with corticosteroid and immunosuppressant medications.

In October 2011, she developed asthenopia, severe dry-eye sensation, ocular pain, and dull sensation, with a visual analog scale (VAS) score of 33 points. The VAS is used to assess patients’ subjective complaints.20 It has 12 components: asthenopia, pain, discharge, foreign body sensation, epiphoria, burning, ocular itching, dull sensation, conjunctival injection, dullness, dryness, and photophobia, each of which the patient assigns a value from 0 to 10 points. The most severe symptoms for all 12 subjects would yield a total score of 120 points. The VAS is presented as a set of 10-cm lines, and the patient checks a point on each line corresponding to his or her degree of sensation.

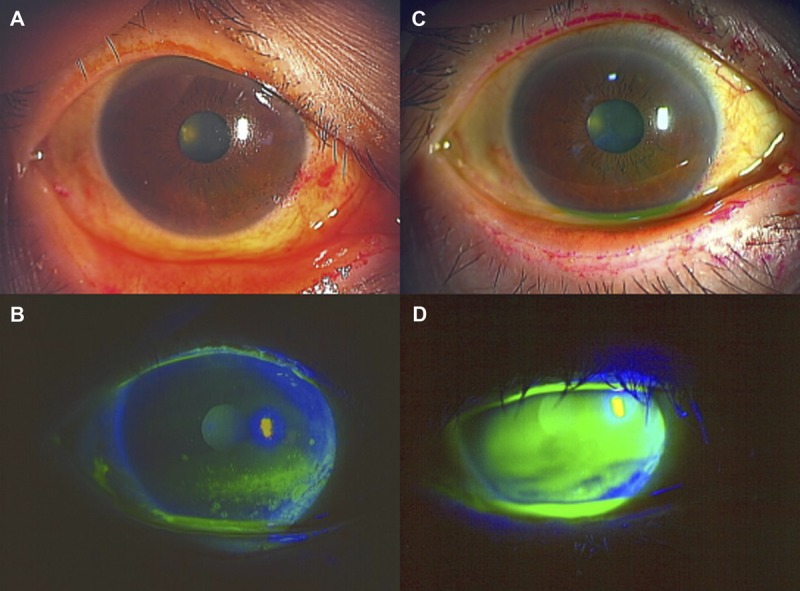

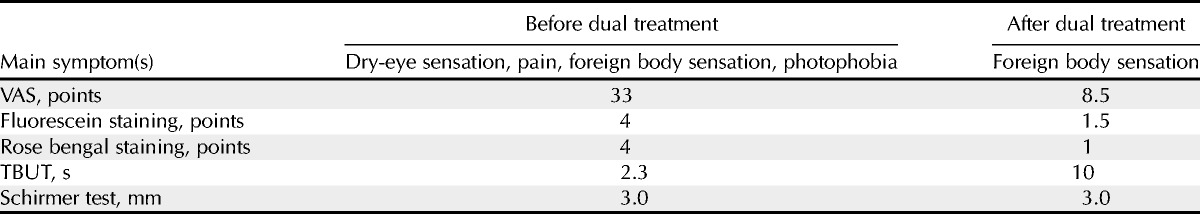

Slit-lamp examination showed diffuse punctate corneal epitheliopathy with a fluorescein score of 4 points, a rose bengal score of 4 points, and abnormality of tear dynamics with a Schirmer value of 3 mm and a TBUT score of 2.3 seconds (Fig. 1A, B; Table 1).20 For these analyses, the ocular surface is stained with 2 μl of either 1% fluorescein or 1% rose bengal solution, instilled into the conjunctival sac. After the patient blinks a few times, the patient is asked to blink before assessing the staining. The staining is scored as follows. The cornea is divided into three zones (upper, middle, and lower) that are assessed for fluorescein staining, and the ocular surface is divided into three areas (nasal, temporal conjunctival, and cornea) that are assessed for rose bengal staining. Each zone has a staining score from 0 (no damage) to 3 (damage in the entire area) points with minimum and maximum total scores ranging from 0 to 9 points. Therefore, there are 0 to 9 possible points for fluorescein staining and 0 to 9 points for rose bengal staining.21,22 Based on these analyses, cGVHD-related dry-eye disease was diagnosed in both of the patient’s eyes. She also manifested cGVHD of the mouth and skin. The patient was treated with tear substitutes, including eye drops containing 0.1% topical sodium hyaluronate (Santen Pharmaceutical Co Ltd), diquafosol (Santen Pharmaceutical Co Ltd), and ofloxacin (Santen Pharmaceutical Co Ltd), after which the symptoms and objective findings improved slightly. In February 2012, punctal plugs were inserted into the patient’s left and right lower puncta to improve symptoms and objective findings, especially eye pain and aqueous tear deficiency. Punctal plugs are used to retain the aqueous tear fluid when there is an aqueous deficiency among the loss of tear film components. In addition, treatment using fluorometholone eye drops (Santen Pharmaceutical Co Ltd) commenced. In an effort to further improve the patient’s condition, a combination therapy of diquafosol eye drops six times per day and rebamipide eye drops four times per day was started in March 2012. Ofloxacin and fluorometholone were stopped before the commencement of rebamipide, whereas the diquafosol was continued. Soon after starting the dual treatment, the sum of the patient’s subject scores in the VAS dropped from 33 to 8.5 points, indicating that her subjective symptoms had improved considerably. Improvements were also seen in the fluorescein score (1.5 points), rose bengal score (1 point), and TBUT score (10 seconds). However, the Schirmer test value did not improve after the dual treatment (Fig. 1C, D; Table 1). Limbal redness and bulbar redness were reduced after the dual treatment. No serious adverse events were observed. After 9 months of this treatment, the clinical findings of dry eye improved and remained stable (Table 1). The patient tolerated these eye drops well.

FIGURE 1.

Slit-lamp photographs before and after dual treatment (case 1). (A, B) Slit-lamp photographs showing rose bengal (A) and fluorescein (B) staining of a cGVHD patient with moderate dry eye in the left eye before combined treatment with topical rebamipide and diquafosol. (C, D) Slit-lamp photographs of the ocular surface condition in the same cGVHD patient after long-term topical rebamipide combined with diquafosol treatment. Note the remarkable improvement in the rose bengal (C) and fluorescein (D) staining, including the tear meniscus height (D) in the left eye.

TABLE 1.

Improvement of clinical findings after topical diquafosol and rebamipide (case 1)

Case 2

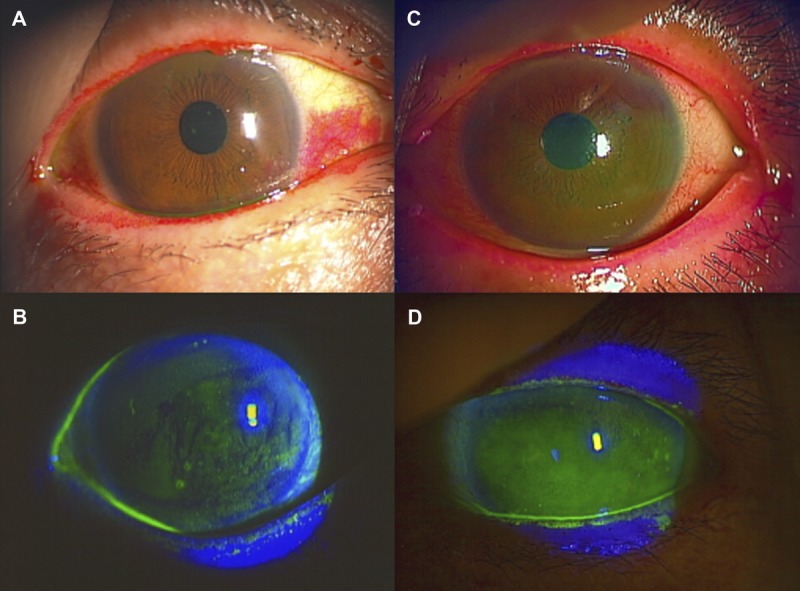

A 77-year-old woman underwent cataract surgery in 2001 and 2002. She exhibited keratoconjunctival epithelial damage due to dry-eye disease and began treatment with 0.1% topical sodium hyaluronate (Santen Pharmaceutical Co Ltd) in May 2003. In addition, vitamin A eye drops were applied and punctal plugs were inserted in both eyes. The patient was also treated with autologous serum, artificial tears, and therapeutic contact lenses in December 2007. However, these therapies did not improve the signs and symptoms of dry eye (Fig. 2A, B; Table 2). Therapeutic contact lenses were off after 1 month to avoid ocular surface infection. The patient exhibited OCP-like dry eye, with mild fornix shortening, conjunctival fibrosis, and mild keratoconjunctival epithelial damage due to dry-eye disease. She was negative for anti-SSA, anti-SSB, antinuclear antibodies, and rheumatoid factor. They are often found in the sera of SS and a hallmark of SS. Therefore, she did not likely have SS. Tranilast eye drops (Kissei Pharmaceutical Co Ltd) and fluorometholone eye drops (Santen Pharmaceutical Co Ltd) were added to her treatment regimen. Application of the tranilast eye drops (four times per day) was started in February 2010 to suppress the progression of conjunctival fibrosis,23 a characteristic feature of OCP, until 9 months before the commencement of rebamipide. Tranilast inhibits transforming growth factor-beta signaling, and topical tranilast is reported to be partly effective to suppress ocular GVHD.24 In this patient, tranilast and fluorometholone were discontinued because the conjunctival fibrosis was stabilized. Vitamin A was also discontinued because the patient was concerned about its long-term use. The patient began treatment with rebamipide eye drops in May 2012 because of worsening of several symptoms including severe pain, dry-eye sensation, asthenopia, dull sensation, sign of redness of conjunctiva, and tear film instability. Application of artificial tears five times per day, methylcellulose five times per day, and ofloxacin eye ointment once per day was continued in conjunction with rebamipide.

FIGURE 2.

Slit-lamp photographs before and after dual treatment (case 2). (A, B) Slit-lamp photographs showing the rose bengal (A) and fluorescein (B) staining of an OCP-like disease patient with moderate dry eye in the left eye before treatment with topical rebamipide. (C, D) Slit-lamp photographs of the ocular surface condition in the same OCP-like disease patient after long-term topical rebamipide treatment. Note the remarkable improvement especially in rose bengal (C) and fluorescein (D) staining including the tear meniscus height (D) in the left eye.

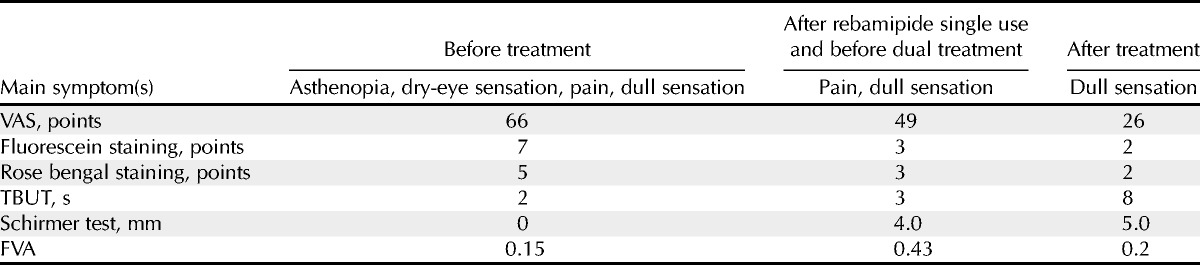

TABLE 2.

Improvement of clinical findings after topical rebamipide with diquafosol (case 2)

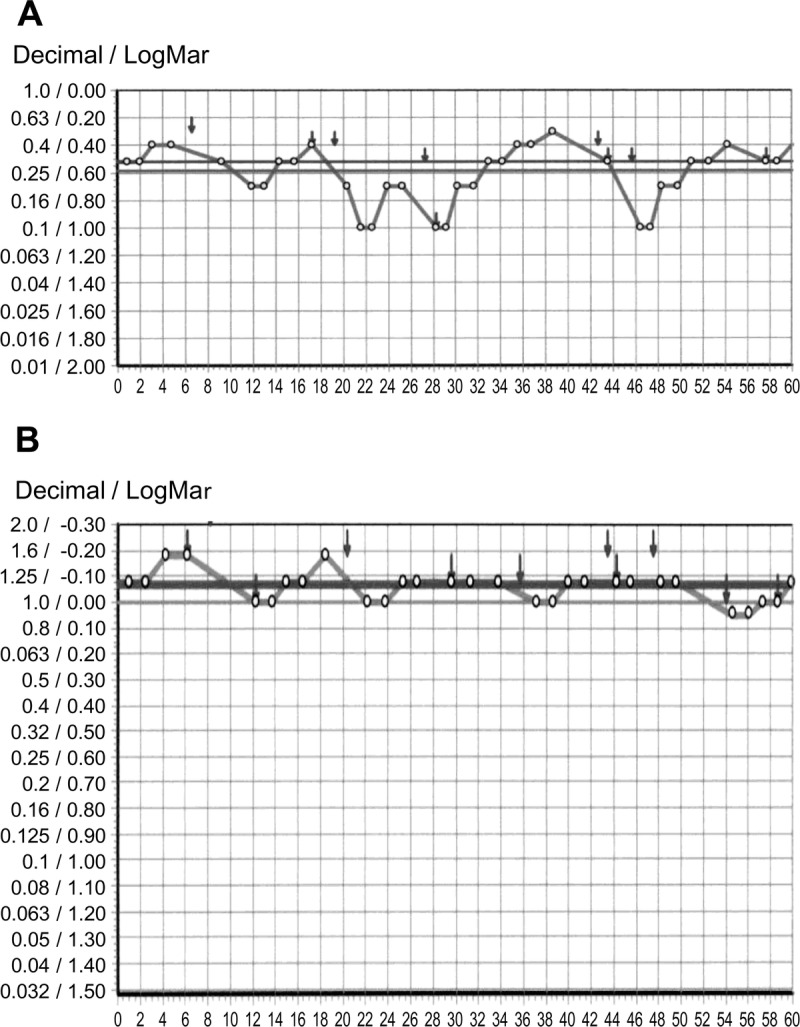

Two weeks later, her symptoms began to improve gradually. After using rebamipide eye drops in addition to her other treatments for 9 months, the clinical findings and symptoms of dry eye improved and remained stable (Fig. 2C, D; Table 2). In particular, functional visual acuity (FVA) was dramatically improved after rebamipide treatment. Functional visual acuity is a useful measure for patients with dry-eye disease, because it reflects tear film stability. In this test, the patient does not blink for 60 seconds, and a continuous assessment of visual acuity is obtained. Topical anesthesia is applied before measuring the FVA, to reduce reflex tearing and blinking. The patient is shown images of a Landolt ring, the size of which increases and decreases automatically when the patient is incorrect and correct, respectively.25 Functional visual acuity scores are presented as decimals; thus, a score of 0.1 (20/200) is the same as logMAR (logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution) 1.0 in Snellen acuity, and 1.0 (20/20) is the same as logMAR 0.0. In this case, the FVA score was 0.15 before treatment and improved to 0.43 after treatment (Fig. 3A, B).25,26 The decimal visual acuity also changed, that is, from 0.3 to 1.2. The rebamipide eye drops worked well for the patient, and she did not experience any side effects.

FIGURE 3.

Functional visual acuity. Remarkable improvement in FVA after long-term topical rebamipide treatment. Functional visual acuity before (A) and after (B) the single therapy using topical rebamipide is shown.

Although rebamipide was partly effective for this patient for 9 months, we decided to add diquafosol to see if there would be further improvement. We envisaged (1) that diquafosol had synergic effects with rebamipide on mucin production and (2) that diquafosol could improve the aqueous tear fluid layer. After the treatment, the sum of the patient’s subject scores in the VAS gradually dropped from 66 to 49 points with rebamipide and from 49 to 26 with the dual treatment, indicating that her subjective symptoms had improved considerably. The scores for TBUT (from 3 to 8 seconds) and corneal epithelium (from 3 to 2 points) indicated improvement using the dual treatment (Table 2), and limbal redness and bulbar redness were reduced after the dual treatment. No serious adverse events were observed. The combined treatment using diquafosol and rebamipide was considered successful.

DISCUSSION

This study focused on treatment of particular types of immune-mediated dry eye such as dry-eye disease caused by cGVHD and OCP-like dry-eye disease. We demonstrated that long-term dual treatment with diquafosol and rebamipide was effective for specific kinds of immune-mediated dry-eye patients who do not respond to other conventional eye drops.

Because of the chronic nature of these particular types of immune mediated dry-eye diseases, long-term safety is clearly needed.6 In our cases, long-term efficacy in addition to other currently available therapy was observed at least for 10 months during single or dual treatment using these medications, although future work with a larger sample size is necessary to confirm this.

There are no particular side effects in the two patients. Although we have been treating cGVHD- or OCP-related dry-eye patients using currently available treatments,27,28 specific therapies have yet to be developed for these diseases. Therapeutic interventions for these specific types of dry-eye diseases are limited at present because adding several treatments to basic therapies depends on the signs and symptoms in each case and the severity of the disease.

The dry-eye cases in this study may be considered mild to moderate according to the 2007 Report of the International Dry Eye WorkShop1; that is, the goblet cells of the conjunctiva might not be severely damaged as we have previously reported.18,29 In both cases, the mucin-related drugs may contribute to the improvement by increasing the mucin from goblet cells or secretory vesicles of the cornea and conjunctival epithelia.2,3,30 In addition, the diquafosol eye drops probably increased water secretion,8 whereas rebamipide eye drops had anti-inflammatory effects11,12 on these types of immune-mediated dry eye.31

In the two specific types of dry-eye disease in this case report, the long-term use of a combination of diquafosol and rebamipide eye drops improved the signs and symptoms of the two dry-eye patients. The conditions of their eyes were stabilized by the treatment, and they did not experience any disabling side effects.

Topical 3% diquafosol tetrasodium (Santen Pharmaceutical Company, Osaka, Japan) was approved in 2010 in Japan and in 2013 in South Korea for treatment of dry-eye disease including Sjogren syndrome, tear film instability, and the short TBUT type of dry eye.4,5,8,13,32 Diquafosol has been reported to be effective in restoring damaged ocular surface epithelia for the retention of the tear film and the mucin coating, because diquafosol eye drops promote the secretion of mucin and water.8

Because the P2Y2 receptor has also been shown to exist in the meibomian gland,33 we envisage that diquafosol eye drops could improve the meibomian gland function in these patients.

Rebamipide (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd) is a mucosal protective agent for producing ocular surface mucins and repairing the ocular surface barrier.34 Rebamipide has been in clinical use in Japan and other Asian countries since 1990 as an oral drug for the treatment of gastritis and gastritic ulcer.6 Rebamipide has been shown to increase the amount of mucin-like substances in the ocular surface in an N-acetylcysteine-treated animal model.35 In addition to increasing the proliferation of cultured rat conjunctival goblet cells,36 suppression of inflammation such as T cell activation and Th1 cytokine production has been reported.34

In case 1, symptoms and clinical findings of cGVHD-related dry eye improved, whereas the value of the Schirmer test did not. Previous reports suggested that early fibrosis and inflammation have been reported in the lacrimal glands affected by cGVHD and that they cause aqueous tear deficiency as well as ocular surface epithelial damage and meibomian gland dysfunction.37,38 In addition, because of its mechanism of action, diquafosol has been reported to have the ability to secrete water from the conjunctiva but not from the lacrimal glands. Therefore, TBUT and ocular surface findings improved because of water secretion from the conjunctiva and mucin production. In case 2, FVA improved after the start of rebamipide administration. Conjunctival fibrosis in case 2, a characteristic feature of OCP, causes friction between palpebral conjunctiva and ocular surface epithelia and thereby damages ocular surface epithelia. Treatment with rebamipide increases tear volume, which contributes to reduction of friction, lubrication of ocular surface, and tear film stability. Therefore, it is likely that FVA can improve.

Because rebamipide was partly effective for this patient for 9 months in case 2, we decided to add diquafosol to see if there would be further improvement. We envisaged (1) that diquafosol had synergic effects with rebamipide on mucin production and (2) that diquafosol could improve the aqueous tear fluid layer. In addition, no topical treatment other than diquafosol was available. In these cases, it is conceivable that the mucin-related eye drops improved keratoconjunctival epithelial damage and extended the TBUT. These findings suggest that the long-term use of a combination of diquafosol and rebamipide can be effective in treating dry eye caused by specific diseases such as cGVHD and OCP-like disease, if the severity of dry eye is assessed carefully. Future work is needed with a larger sample size to confirm these reports.

Based on these findings and previous reports, we hypothesized the following mechanism of improvement of dry-eye disease in two cases. Regeneration of barrier function in ocular surface epithelium, increased mucin production, and increased lubrication for palpebral friction in conjunctival fibrosis by rebamipide and diquafosol are among the underlying mechanisms of ocular surface improvement caused by the synergic effect of both eye drops. Washing out inflammatory cytokines in tear fluid by both medications might be one of the mechanisms for the improvement of signs and symptoms of the specific type of dry-eye disease. Increased tear volume by diquafosol and anti-inflammatory effects such as inhibition of cytokine production and infiltration of inflammatory cells by rebamipide can result in an improvement of this type of dry-eye condition. Taking these mechanisms of action together, the dual treatment can be useful in treating these types of immune-mediated dry-eye disease.

A combination of rebamipide and diquafosol can be one of the novel therapeutic interventions for topically treating mild to moderate immune-mediated dry-eye diseases.

Our data suggest that dual treatment with diquafosol and rebamipide can be one option to topically treat dry-eye disease associated with other specific diseases. It has been reported that these treatments are most likely effective for mild to moderate cases of common dry eye.13,26 In such cases, long-term treatment with mucin-related eye drops, along with conventional treatments, is recommended. The present cases further indicate that dry-eye patients with cGVHD and OCP-like disease can be treated long-term with rebamipide and diquafosol eye drops, either singly or together.

In summary, both diquafosol and rebamipide increase mucin secretion. In addition, diquafosol has aqueous secretion effects, and rebamipide has various anti-inflammatory effects. Both cGVHD and OCP-like dry eye involve chronic inflammation of the ocular surface and a three-component deficiency including lipid, aqueous tear fluid, and mucins, whereas other types of dry-eye disease can be caused by loss of one of the tear components. Therefore, both of these medications are effective for immune-mediated dry-eye diseases, probably in part by acting synergistically. At present, this dual treatment may be a better option available for certain patients. Further studies involving a large number of randomized clinical trials will be required to analyze the effectiveness of these two drugs and to gain insight into the correct regimen and timing of the commencement of the dual treatment for various types of immune-mediated dry-eye disease.

Yoko Ogawa

Department of Ophthalmology

Keio University School of Medicine

35, Shinanomachi, Shinjuku-ku

Tokyo, 160-8582

Japan

e-mail: yoko@z7.keio.jp

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture (no. 23592590 and no. 26462668).

The authors declare that there is no conflict to disclose.

This work was presented at the 37th Japan Cornea Society, Japan Cornea Conference 2013 in Wakayama, Japan.

SUPPLEMENTAL DIGITAL CONTENT

Supplement Digital Content 1, a .wmv video, is available online at http://links.lww.com/OPX/A201.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.optvissci.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf 2007; 5: 75– 92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gipson IK, Hori Y, Argueso P. Character of ocular surface mucins and their alteration in dry eye disease. Ocul Surf 2004; 2: 131– 48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tatematsu Y, Ogawa Y, Shimmura S, Dogru M, Yaguchi S, Nagai T, Yamazaki K, Kameyama K, Okamoto S, Kawakami Y, Tsubota K. Mucosal microvilli in dry eye patients with chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2012; 47: 416– 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matsumoto Y, Ohashi Y, Watanabe H, Tsubota K. Efficacy and safety of diquafosol ophthalmic solution in patients with dry eye syndrome: a Japanese phase 2 clinical trial. Ophthalmology 2012; 119: 1954– 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takamura E, Tsubota K, Watanabe H, Ohashi Y. A randomised, double-masked comparison study of diquafosol versus sodium hyaluronate ophthalmic solutions in dry eye patients. Br J Ophthalmol 2012; 96: 1310– 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kinoshita S, Awamura S, Nakamichi N, Suzuki H, Oshiden K, Yokoi N, Rebamipide Ophthalmic Suspension Long-term Study Group. A multicenter, open-label, 52-week study of 2% rebamipide (OPC-12759) ophthalmic suspension in patients with dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 157: 576– 83.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kinoshita S, Oshiden K, Awamura S, Suzuki H, Nakamichi N, Yokoi N. Rebamipide Ophthalmic Suspension Phase 3 Study Group. A randomized, multicenter phase 3 study comparing 2% rebamipide (OPC-12759) with 0.1% sodium hyaluronate in the treatment of dry eye. Ophthalmology 2013; 120: 1158– 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakamura M, Imanaka T, Sakamoto A. Diquafosol ophthalmic solution for dry eye treatment. Adv Ther 2012; 29: 579– 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanaka H, Fukuda K, Ishida W, Harada Y, Sumi T, Fukushima A. Rebamipide increases barrier function and attenuates TNFalpha-induced barrier disruption and cytokine expression in human corneal epithelial cells. Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 97: 912– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ueta M, Sotozono C, Yokoi N, Kinoshita S. Rebamipide suppresses PolyI:C-stimulated cytokine production in human conjunctival epithelial cells. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2013; 29: 688– 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kimura K, Morita Y, Orita T, Haruta J, Takeji Y, Sonoda KH. Protection of human corneal epithelial cells from TNF-alpha-induced disruption of barrier function by rebamipide. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013; 54: 2572– 760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kashima T, Akiyama H, Miura F, Kishi S. Resolution of persistent corneal erosion after administration of topical rebamipide. Clin Ophthalmol 2012; 6: 1403– 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koh S, Ikeda C, Takai Y, Watanabe H, Maeda N, Nishida K. Long-term results of treatment with diquafosol ophthalmic solution for aqueous-deficient dry eye. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2013; 57: 440– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Riemens A, Te Boome LC, Kalinina Ayuso V, Kuiper JJ, Imhof SM, Lokhorst HM, Aniki R. Impact of ocular graft-versus-host disease on visual quality of life in patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: questionnaire study. Acta Ophthalmol 2014; 92: 82– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ogawa Y, Kim SK, Dana R, Clayton J, Jain S, Rosenblatt MI, Perez VL, Shikari H, Riemens A, Tsubota K. International Chronic Ocular Graft-vs-Host-Disease (GVHD) Consensus Group: proposed diagnostic criteria for chronic GVHD (Part I). Sci Rep 2013; 3: 3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, Socie G, Wingard JR, Lee SJ, Martin P, Chien J, Przepiorka D, Couriel D, Cowen EW, Dinndorf P, Farrell A, Hartzman R, Henslee-Downey J, Jacobsohn D, McDonald G, Mittleman B, Rizzo JD, Robinson M, Schubert M, Schultz K, Shulman H, Turner M, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005; 11: 945– 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ogawa Y, Razzaque MS, Kameyama K, Hasegawa G, Shimmura S, Kawai M, Okamoto S, Ikeda Y, Tsubota K, Kawakami Y, Kuwana M. Role of heat shock protein 47, a collagen-binding chaperone, in lacrimal gland pathology in patients with cGVHD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48: 1079– 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Y, Ogawa Y, Dogru M, Tatematsu Y, Uchino M, Kamoi M, Okada N, Okamoto S, Tsubota K. Baseline profiles of ocular surface and tear dynamics after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with or without chronic GVHD-related dry eye. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010; 45: 1077– 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chang JH, McCluskey PJ. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: manifestations and management. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2005; 5: 333– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kojima T, Ishida R, Dogru M, Goto E, Matsumoto Y, Kaido M, Tsubota K. The effect of autologous serum eyedrops in the treatment of severe dry eye disease: a prospective randomized case-control study. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 139: 242– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tsubota K, Toda I, Yagi Y, Ogawa Y, Ono M, Yoshino K. Three different types of dry eye syndrome. Cornea 1994; 13: 202– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Bijsterveld OP. Diagnostic tests in the Sicca syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1969; 82: 10– 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hida RY, Takano Y, Okada N, Dogru M, Satake Y, Fukagawa K, Fujishima H. Suppressive effects of tranilast on eotaxin-1 production from cultured conjunctival fibroblasts. Curr Eye Res 2008; 33: 19– 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ogawa Y, Dogru M, Uchino M, Tatematsu Y, Kamoi M, Yamamoto Y, Ogawa J, Ishida R, Kaido M, Hara S, Matsumoto Y, Kawakita T, Okamoto S, Tsubota K. Topical tranilast for treatment of the early stage of mild dry eye associated with chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010; 45: 565– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishida R, Kojima T, Dogru M, Kaido M, Matsumoto Y, Tanaka M, Goto E, Tsubota K. The application of a new continuous functional visual acuity measurement system in dry eye syndromes. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 139: 253– 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaido M, Dogru M, Ishida R, Tsubota K. Concept of functional visual acuity and its applications. Cornea 2007; 26: S29– 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Espana EM, Shah S, Santhiago MR, Singh AD. Graft versus host disease: clinical evaluation, diagnosis and management. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013; 251: 1257– 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hessen M, Akpek EK. Ocular graft-versus-host disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 12: 540– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang Y, Ogawa Y, Dogru M, Kawai M, Tatematsu Y, Uchino M, Okada N, Igarashi A, Kujira A, Fujishima H, Okamoto S, Shimazaki J, Tsubota K. Ocular surface and tear functions after topical cyclosporine treatment in dry eye patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008; 41: 293– 302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gipson IK. Distribution of mucins at the ocular surface. Exp Eye Res 2004; 78: 379– 88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lau OC, Samarawickrama C, Skalicky SE. P2Y2 receptor agonists for the treatment of dry eye disease: a review. Clin Ophthalmol 2014; 8: 327– 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shimazaki-Den S, Iseda H, Dogru M, Shimazaki J. Effects of diquafosol sodium eye drops on tear film stability in short BUT type of dry eye. Cornea 2013; 32: 1120– 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cowlen MS, Zhang VZ, Warnock L, Moyer CF, Peterson WM, Yerxa BR. Localization of ocular P2Y2 receptor gene expression by in situ hybridization. Exp Eye Res 2003; 77: 77– 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sugai S, Takahashi H, Ohta S, Nishinarita M, Takei M, Sawada S, Yamaji K, Oka H, Umehara H, Koni I, Sugiyama E, Nishiyama S, Kawakami A. Efficacy and safety of rebamipide for the treatment of dry mouth symptoms in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome: a double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Mod Rheumatol 2009; 19: 114– 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Urashima H, Okamoto T, Takeji Y, Shinohara H, Fujisawa S. Rebamipide increases the amount of mucin-like substances on the conjunctiva and cornea in the N-acetylcysteine-treated in vivo model. Cornea 2004; 23: 613– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rios JD, Shatos M, Urashima H, Tran H, Dartt DA. OPC-12759 increases proliferation of cultured rat conjunctival goblet cells. Cornea 2006; 25: 573– 81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ogawa Y, Yamazaki K, Kuwana M, Mashima Y, Nakamura Y, Ishida S, Toda I, Oguchi Y, Tsubota K, Okamoto S, Kawakami Y. A significant role of stromal fibroblasts in rapidly progressive dry eye in patients with chronic GVHD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001; 42: 111– 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ban Y, Ogawa Y, Ibrahim OM, Tatematsu Y, Kamoi M, Uchino M, Yaguchi S, Dogru M, Tsubota K. Morphologic evaluation of meibomian glands in chronic graft-versus-host disease using in vivo laser confocal microscopy. Mol Vis 2011; 17: 2533– 43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]