Abstract

Myxoma virus (MV) is a rabbit-specific poxvirus, whose unexpected tropism to human cancer cells has led to studies exploring its potential use in oncolytic therapy. MV infects a wide range of human cancer cells in vitro, in a manner intricately linked to the cellular activation of Akt kinase. MV has also been successfully used for treating human glioma xenografts in immunodeficient mice. This study examines the effectiveness of MV in treating primary and metastatic mouse tumors in immunocompetent C57BL6 mice. We have found that several mouse tumor cell lines, including B16 melanomas, are permissive to MV infection. B16F10 cells were used for assessing MV replication and efficacy in syngeneic primary tumor and metastatic models in vivo. Multiple intratu-moral injections of MV resulted in dramatic inhibition of tumor growth. Systemic administration of MV in a lung metastasis model with B16F10LacZ cells was dramatically effective in reducing lung tumor burden. Combination therapy of MV with rapamycin reduced both size and number of lung metastases, and also reduced the induced antiviral neutralizing antibody titres, but did not affect tumor tropism. These results show MV to be a promising virotherapeutic agent in immunocompetent animal tumor models, with good efficacy in combination with rapamycin.

INTRODUCTION

Oncolytic virotherapy (the use of viruses to target and destroy cancer cells) is a novel form of cancer treatment derived from a finding over a century ago that virus infection could have a positive effect on tumor regression.1 The ideal oncolytic virus candidate is required to possess a selective tropism for tumor tissue, and little or no ability to cause significant disease in normal tissue.2–4 A number of oncolytic virus candidates, such as adenovirus,5 herpes virus,6 reovirus,7 measles virus,8 and poxvirus (vaccinia virus)9 have been studied, and have been shown to have varying degrees of oncolytic efficacy in numerous tumor models.10 More recently, myxoma virus (MV) has been added to this expanding list of oncolytic virus candidates.11

MV is a poxvirus of the Leporipoxvirus genus and the Chordopoxvirinae subfamily of Poxviridae.12 It is a rabbit-specific pathogen, and causes a lethal disease known as myxomatosis in European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus).13 However, other than in the lagomorph species MV is not known to cause disease in any other vertebrate species.12,14–16 In mice, the host barrier to infection with MV has been linked to induced interferon responses.17 Recently, MV tropism in vitro has been extended to include a large percentage of human tumor cells.11 Further study has linked this increased tropism for human tumor cells to the hyperactivation of the serine/threonine kinase Akt in cancer cell lines.18 Human cancer cells can be grouped into three categories on the basis of their ability to be productively infected with MV, and the ability of MV to activate Akt through the action of a viral protein, M-T5.11,18 In examining ways to increase the tropism of MV to human cancer cells, we have explored the use of rapamycin in the treatment for human cancers. Rapamycin, an immunosuppressant with antitumor effects, acts directly on the mammalian target of rapamycin and can activate Akt.19 We have shown that rapamycin treatment can increase the replication of MV.20

In addition to in vitro studies examining the oncolytic capacity of MV, in vivo studies examining the potential of MV as a cancer therapy have also been carried out.21 In an orthotopic xenograft model in immune-compromised nude mice, intracerebral injection of MV was well tolerated, and intratumoral (IT) injection was effective in indefinitely prolonging the survival of mice engrafted with human gliomas.21 These mice also demonstrated a long-lasting viral infection of their tumors in situ until the tumors themselves regressed.

This study tests MV efficacy in a fully syngeneic immuno-competent mouse model. We demonstrate that murine tumor cells can be infected with MV in a manner similar to human tumor cell lines, and can be classified based on permissivity for MV infection and Akt kinase activity. IT infection of MV was shown to be effective in reducing primary tumor growth of the aggressive B16F10 melanoma in a subcutaneous injection model. Systemic administration of MV is shown to be both well tolerated and effective in decreasing lung metastasis of B16F10LacZ. Rapamycin treatment of B16F10LacZ cells in vitro resulted in modest increases in viral titers, but in vivo administration with MV decreased the tumor burden in doubly treated mice, and also decreased neutralizing antibody responses to MV induced by systemic administration. This study demonstrates that MV is capable of targeting and destroying tumors while causing no significant disease or collateral tissue infection in an immunocompetent host, and can be combined with drugs such as rapamycin, further supporting the potential of this virus as a significant oncolytic candidate in cancer therapy.

RESULTS

MV productively infects murine tumor cells in vitro

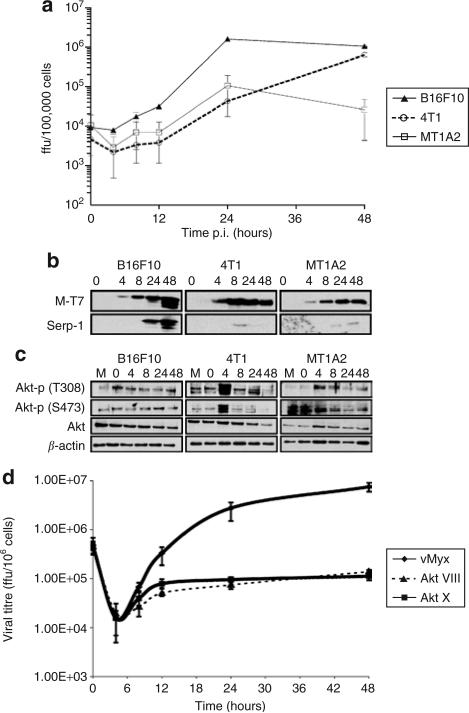

Using a single-step growth curve, we show that murine tumor cells (as do human cells) differ in their permissiveness to MV (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure S1).18 The murine melanoma B16F10 cells (Type I) were highly permissive to MV, with robust replication (Figure 1a) and production of both early (M-T7) and late (Serp-1) MV proteins secreted into infected cell supernatants (Figure 1b). In comparison, the murine mammary carcinoma 4T1 cell line demonstrates lower levels of MV replication (Figure 1a) and late MV gene production (Figure 1b), but is nevertheless able to form MV foci (data not shown), and is more closely related to Type II human cancer cells. The murine mammary carcinoma MT1A2 cell line is the least permissive murine cancer cell line tested, exhibiting little MV replication (Figure 1a), despite having the ability to support the production of MV early proteins (Figure 1b). Similar findings were found with the murine tumor cell lines B16F1 (Type I), CT-26 (Type II), and D2A1 (Type III) (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1. Permissiveness of myxoma virus (MV) in selected murine tumor cell lines.

(a) Single-step growth analysis of vMyxlac was evaluated on B16F10 (closed triangles), 4T1 (open circles), and MT1A2 (open squares) murine tumor cells. All growth analyses were performed in trip-licate. (b) Early viral protein expression was determined by the expression of M-T7, and late protein expression by the expression of Serp-1 at the indicated time points by Western blot analysis of cellular super-natants. M indicates mock infection. (c) The levels of whole Akt protein and of phosphorylated Akt (at serine 473, S473 and threonine 308, T308) were detected in cellular lysates by Western blot analysis. (d) The effect of Akt inhibitors on MV replication in B16F10 cells. The cells were either mock-treated or pre-incubated with the indicated inhibitors Akt X (10 μmol/l; squares) or Akt VIII (5 μmol/l; closed triangles) for 4 hours prior to vMyxgfp infection. Ffu, focus forming units.

We also tested the Akt kinase activation in these cells (Figure 1c,Supplementary Figure S1). The B16F10 cell line demonstrated a high endogenous level of Akt kinase, correlating well with permissiveness to MV. In the 4T1 and MT1A2 cell lines, there was little or no detectable endogenous activated Akt, but there was a transient and robust induction of phosphorylated Akt detected in the 4T1 cell line, and a much lower level in MT1A2 cell line, consistent with findings in human Type II and Type III cancer cells, respectively.18 Similar trends are seen in B16F1, CT-26, and D2A1 cell lines (Supplementary Figure S1). We also tested the ability of Akt inhibitors to decrease the capacity of MV to infect B16F10 cells (Figure 1d). The inhibition of Akt kinase activation by two separate inhibitors dramatically decreased the ability of the virus to replicate, in agreement with findings in human tumor cells.18 These results indicate that both murine and human tumor cells are permissive to MV infection in a P-Akt-dependent manner.

IT MV injection inhibits the development of primary B16F10 tumors

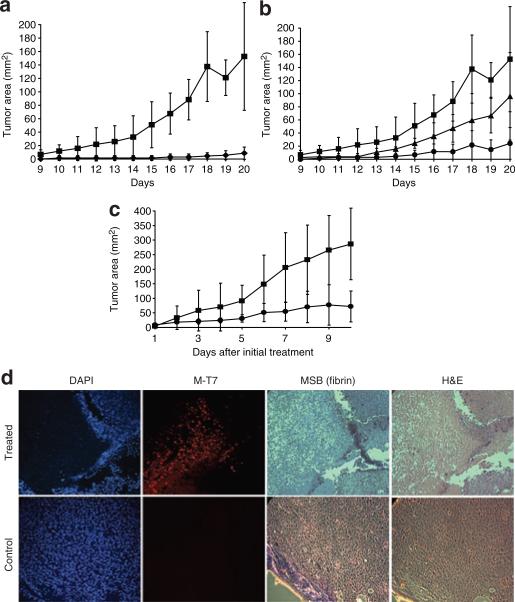

In order to determine whether infection with MV has the potential to inhibit or prevent B16F10 tumor cells from forming primary tumors in syngeneic, immunocompetent C57BL6 mice, we pre-infected these cells in culture prior to subcutaneous injection into mice (Figure 2a and b). At a dose of 107 focus forming units (ffu) of vMyxgfp, corresponding to a multiplicity of infection of 30 ffu/cell [as titered in the control baby green monkey kidney (BGMK) cell line], all the B16F10 cells were infected in vitro, as visualized by fluorescence microscopy and, when injected, exhibited little or no ability to form tumors in vivo (Figure 2a). The effect of MV on pre-infected cells was dependent on the multiplicity of infection dose of MV. When tumor cells were pre-infected with 106 (Figure 2b, triangles) or 105 (Figure 2b, circles) ffu of MV, the injected cells that were not infected with MV were able to form identifiable tumors. The most significant observation following pre-infection with suboptimal doses of virus was a delay in tumor progression when compared with uninfected control cells (Figure 2b). These results indicate that infection of B16F10 melanoma cells with MV will kill the cells and prevent their development into tumors. However, the critical determinant of successful control of the tumor is the complete infection of all cancerous cells in this model.

Figure 2. Effectiveness of myxoma virus (MV) treatment in a primary tumor model of B16F10.

Pre-infected cells do not form tumors. (a) B16F10 cells were pre-infected with increasing doses of vMyxgfp in vitro prior to subcutaneous injection, and their ability to form tumors was evaluated over time by caliper measurement of tumor growth. The cells were either treated with no virus (closed squares) or 107 focus forming units (ffu) (closed diamonds) of MV for 1 hour prior to injection. (b) Dose–response relating to pre-treatment of cells that were untreated (closed squares), or received either 105 ffu (closed triangles) or 106 ffu (closed circles) of MV 1 hour prior to injection. (c) Treatment of small tumors with vMyxgfp. The recipient mice were injected with B16F10 cells, and then either left untreated (closed squares), or treated with 3 × 108 ffu of vMyxgfp intratumorally daily. The tumors were monitored for size by caliper measurement. (d) Deposition of extracellular matrix prevents dissemination of vMyxgfp. Tumors were sectioned and stained with the nuclear stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), for fibrin (MSB), the viral antigen M-T7,or stained with hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E). Magnification, ×50. MSB, Martius yellow-brilliant crystal scarlet-soluble blue.

In order to determine whether MV could be used to treat established primary murine tumors in vivo in an immunocompetent host, we used IT injection of the virus to treat established subcutaneous B16F10 tumors (Figure 2c). As seen in Figure 2c, direct, daily injections of MV significantly (P = 0.0095 by analysis of variance) decreased the surface area of primary tumors, as compared to animals which received no virus treatment. Differences in tumor size were most dramatic at later time points. We also used immunohistochemistry to examine the dissemination of MV throughout the tumor(Figure 2d). In treated animals, tumor cells that expressed an early secreted MV protein, M-T7 (red staining), corresponded to tissue areas that had lost blue 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining, indicating substantial cellular destruction. A clear margin of soluble viral protein was visible within virus-infected tumors, suggesting a physical block to further virus spread. This was visible as a green area after Martius yellow-brilliant crystal scarlet-soluble blue staining for fibrin. This was not found in the uninfected tumors that were used as controls (Figure 2d).

Systemic treatment with MV inhibits the development of lung metastasis

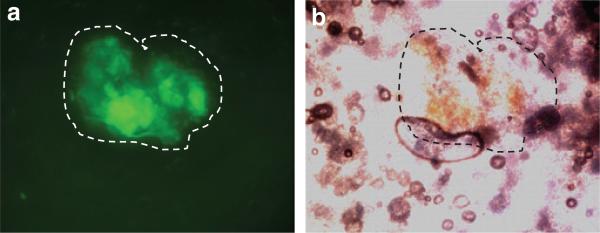

We also tested the ability of systemic MV administration to treat metastatic B16F10 tumors. In these experiments we used vMyx135KO, a recombinant MV that is still able to effectively infect human cancer cells,22 but is no longer pathogenic in rabbits.23 In order to investigate the safety of systemic administration of vMyx135KO, we injected 108 ffu intravenously (IV), and removed the lung, liver, spleen, and kidney 24 hours later to assay for infectious virus. We detected no infectious virus in any organ (data not shown). We also used a B16F10 cell line expressing LacZ so that small metastatic tumors could be stained and visualized. B16F10LacZ cells were injected IV into the animals, and at 7 days after inoculation, vMyx135KO was also delivered IV. Lungs were removed 24 hours later, and the tissue examined without fixation or staining under a fluorescent microscope to visualize enhanced green fluorescence protein expression (Figure 3a). Green fluorescence protein fluorescence expressed by replicating vMyx135KO can be easily visualized in distinct tumor-bearing areas of the lungs, as distinguished by the brown melanin expression of the B16F10 cells (Figure 3b). No comparable enhanced green fluorescence protein fluorescence was detected in the lungs of mice that had been injected with vMyx135KO, but that did not bear B16F10LacZ tumors. When a portion of the lung was homogenized, and the infectious virus within the lysate was titered in vitro, ~3 × 10–3 ffu MV/g of lung tissue was found.

Figure 3. Myxoma virus expressed enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP) localization within the lungs after systemic virus delivery.

B16F10LacZ cells were injected intravenously (IV) into recipient C57BL6 mice. Seven days later, vMyx135KO virus was injected IV. Twenty four hours later, and the lung removed. (a) The expression of virally expressed EGFP was visualized under a fluorescent microscope, and (b) the tumor was visualized from the expression of brown melanin. The tumor is outlined for clarity.

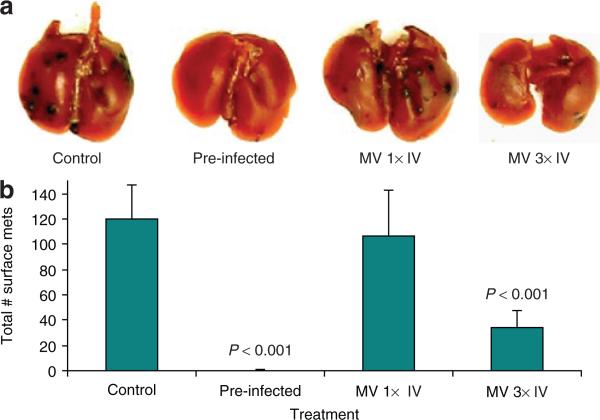

In order to examine B16F10 lung metastasis, B16F10LacZ cells were injected IV into mice. Fourteen days later, the lungs were removed and stained for β-galactosidase (Figure 4a). Untreated control animals had a high number of metastatic tumors, whereas animals that had received B16F10LacZ cells pre-infected with vMyx135KO prior to IV injection did not form any observable lung metastasis (P < 0.001, by t-test). A single IV injection of 3 × 108 ffu vMyx135KO at day 5 did not significantly reduce the number of surface metastases (Figure 4a and b), but three IV injections, one each at days 3, 5, and 8, were very effective in decreasing the number of metastases (P < 0.001) (Figure 4b). Animals receiving IV injection of virus demonstrated no ill effects from multiple high titer MV IV injections. This represents perhaps the first demonstration of safe systemic administration of MV in mice with cancer. It is also the first demonstration that this systemic administration of MV can target and kill metastatic tumors. There was no significant difference in the results with the use of vMyx135KO or vMyxgfp as regards decrease in surface metastases (data not shown).

Figure 4. Systemic administration of vMyx135KO virus prevents development of lung metastases of B16F10LacZ cells.

B16F10LacZ cells were injected intravenously (IV) into recipient C57BL6 mice. Some of the cells were pre-infected with vMyx135KO virus 1 hour prior to injection into mice. Mice were infected with vMyx135KO virus on day 3 [myxoma virus (MV) 1× IV] or on days 1, 3, and 8 (MV 3× IV). At 14 days after injection, the lungs were collected and stained with an X-gal staining solution. The next day, (a) the stained lungs were first photographed, and then the lobes were separated and each lung was separately observed under a dissecting microscope; and (b) the stained surface metastases were counted. The P values result from an unpaired t-test.

Rapamycin improves the oncolytic capacity of MV in treating lung metastases

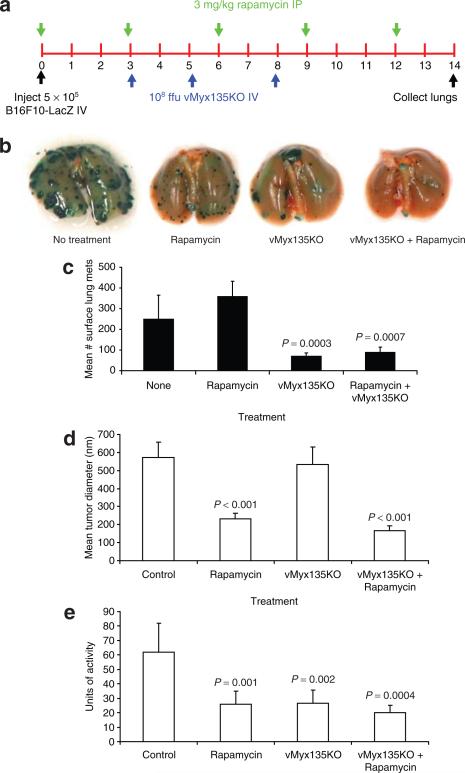

Rapamycin can increase MV replication in some human tumor cells.20 B16F10 is a Type I cancer cell, and we failed to see a significant increase in viral replication after rapamycin treatment in vitro (data not shown). However, rapamycin is also an immunosuppressant with its own anticancer properties; therefore its effect on murine tumor cells, alone or in combination with MV treatment, was examined in this animal model. Mice injected with B16F10LacZ were treated with rapamycin intraperitoneally every 3 days, or received IV injection of MV on days 3, 5, and 8, or received a combination of the two treatments (Figure 5a). At day 14, the lungs were collected for visual analysis of the metastases (Figure 5b), according to number of tumors (Figure 5c), mean tumor size (Figure 5d), and tumor burden (Figure 5e).

Figure 5. Rapamycin augments systemic myxoma virus treatment of B16F10-LacZ lung metastases.

(a) Schematic representation of treatment schedule; (b) The stained lungs were photographed, the lobes were separated, and each lung was separately observed under a dissecting microscope and (c) the number of stained surface metastases counted. The results represent those from 9–14 animals per group. (d) Measurement of the mean size of tumors. Fixed lungs were placed between two slides, and the diameters of individual tumors were measured using OpenLab software. The measurements from each lung were compiled and analyzed. The results are from six animals per treatment. (e) Estimation of tumor burden. One lobe from each animal lung was removed prior to fixation and homogenized. The extent of β-galactosidase activity was determined using a colorimetric assay. The results are representative of six animals per group. The P values result from an unpaired t-test. Ffu, focus forming units. IP, intraperitoneal; IV, intravenous.

Treatment with rapamycin did not affect the number of surface metastases, but it significantly decreased the diameter of the individual tumors (P < 0.001, by t-test) (Figure 5b and d). In fact, analysis of the surface metastases showed that there was a small and statistically insignificant increase in the number of tumors following rapamycin treatment alone (P = 0.549). This could be because of the smaller size of the individual tumors. MV treatment was effective in decreasing the number of surface metastases (P = 0.0003), but the sizes of the residual tumors were similar to those of the controls (Figure 5d). Combination therapy resulted in fewer tumors when compared with the control animals (P = 0.002) or with those on rapamycin treatment alone (P = 0.0007), but this difference was not statistically significant in comparison with the results obtained with vMyx135KO treatment alone, in terms of actual numbers of tumors (Figure 5c). However, these tumors were significantly smaller than those in the controls (P < 0.001) and in the MV treated animals (P < 0.001).

In order to quantify tumor burden, a single lung lobe from each animal was homogenized and the β-galactoside activities were analyzed (Figure 5e). Rapamycin treatment significantly decreased the tumor burden (P = 0.001, by t-test, as compared to the control), thereby indicating that the reduction in size of individual tumors was comparable to the reduction in the number of tumors achieved by MV treatment (P = 0.002) (Figure 5e). When both rapamycin and MV were administered, tumors were both significantly lower in number (Figure 5c) and smaller in size (Figure 5d). The beneficial effect of combination therapy is therefore evident.

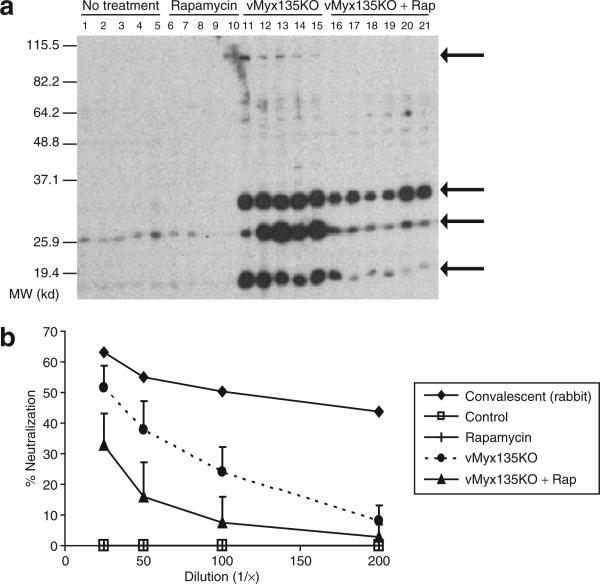

In delivering a virus systemically, a major concern is the stimulation of an immune response to the virus, hampering the effectiveness of subsequent doses. We detected anti-MV antibody production after repeated systemic administration of the virus (Figure 6). The reactivity of serum was compared by Western blotting, using lysates from B16F10 cells or B16F10 cells that had been infected with vMyx135KO (Figure 6a). We detected no reactivity to B16F10 lysates in the sera of any of the mice, nor did the sera of the mice that received either no treatment, or rapamycin treatment alone, react with infected B16F10 lysates (Figure 6a). However, in mice that received three systemic injections of vMyx135KO, we observed four prominent immunoreactive bands on the Western blots, at ~100, 35, 26, and 18 kd (indicated by arrows), but their identities remain to be determined.24 In mice that received combined virus and rapamycin treatment, all of the immunoreactive bands were significantly reduced in intensity. In order to quantify this, we utilized a viral neutralization assay (Figure 6b). As a positive control, we used convalescent sera from rabbits that had been infected with an attenuated recombinant MV, and that had survived infection and became immune to wild-type MV.25 Whereas control mouse sera had no ability to inhibit MV (Figure 6b, open squares), sera from mice receiving multiple MV injections could significantly reduce infectious virus titres (Figure 6b, broken line, closed circles). In comparison, the sera from mice that received a combination of MV and rapamycin had significantly lower titers of MV-neutralizing antibody (P < 0.01, by t-test).

Figure 6. Rapamycin suppresses the antibody response to systemic injection of myxoma virus.

(a) Western blot analysis. Protein lysate was tested from B16F10 cells that had been infected with a high multiplicity of infection (MOI of 3) of vMyx135KO virus for 48 hours. Mouse serum was diluted 1:500; each lane represents the serum from a single mouse. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments. Arrows represent bands of interest. (b) Viral neutralization assay. Mouse or rabbit sera were pre-incubated with vMyxlac at an MOI of 0.001. This mixture was then used to infect baby green monkey kidney (BGMK) cells, and the effect on viral titer was assessed by evaluating foci formation after 48 hours. The results represent one rabbit serum, and sera from five to six mice per group, and are presented as a percentage of the foci formed by virus untreated with serum.

DISCUSSION

For an oncolytic virus candidate to be considered a viable therapeutic option in humans, several parameters must be satisfied. These include the need for the strict tropism of the virus to cancer cells, the safety of the virus in both treated and collateral hosts, and the absence of a potentially attenuating immune response directed against the virus. Our laboratory has demonstrated the ability of rabbit-specific poxvirus (MV) to productively infect human tumor cells,11 and the activation state of the Akt kinase is intricately linked to this tropism.18 Akt is involved in many aspects of cell growth, death, and differentiation, and is amplified or mutated in a large number of malignancies.26,27 Our results here demonstrate that murine tumor cells can be productively infected with MV in an Akt-dependent manner, thus suggesting that the murine cells can act as an appropriate model for human cancer cells in this regard.18

We have demonstrated previously that MV-infected tumor cells will die as a result of virus infection in vitro.11,21 However, it is important to demonstrate that, when completely infected, all the B16F10 cells will be prevented from developing tumors in vivo. When all the cells are pre-infected, no tumors form (Figure 2). Multiple IT injection of MV was able to reduce, but not prevent, tumor formation. When examined histologically, the MV spread within the tumor appeared to have been physically impeded by de novo fibrin deposition. The problem of extracellular matrix protein deposition inhibiting the tumor dissemination of viruses has been demonstrated with other oncolytic viruses too, and has been addressed by the use of extracellular matrix–degrading collagenase28 or the extracellular matrix–degrading protein, relaxin.29,30 These could also be considered in attempts to improve the penetration of MV through tumor tissues that remodel in this fashion.

This is the first report of the delivery of MV to tumors through systemic administration. We show that not only is IV injection of MV well tolerated in mice, but is also specifically targeted to tumor tissue, and decreases lung metastasis of the B16F10 cells. This is important, because metastases are responsible for most cancer deaths, and are much more difficult to treat than the primary tumor.31,32 In these systemic injection studies, vMyx135KO, was used instead of the tagged wild-type MV (vMyxgfp) because it has a significantly attenuated pathogenesis in its natural pathogenic host, European rabbits (O. cuniculus),23 yet replicates at a similar or even higher titer in all cancer cells tested to date.22 vMyx135KO is not pathogenic in any known vertebrate species, including rabbits.

Our studies have found that the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor can enhance the replication of MV human tumor cells in vitro20 and recent work has shown that rapamycin can enhance the oncolytic ability of MV in a murine xenograft model for human medulloblastoma.33 Rapamycin does not significantly increase MV replication in B16F10 cells, but the drug does exhibit growth inhibiting, antiangiogenic, and immunosuppressant properties.34 Rapamycin treatment in mice bearing metastatic B16F10 tumors significantly decreased the sizes of individual tumors, without decreasing the overall number (Figure 5), whereas MV treatment significantly decreased the number of tumors. In this study, rapamycin was administered at levels that are too low to induce either antiangiogenesis or immunosuppression in this model.35 Despite this, when virus and rapamycin treatment were combined, we observed fewer, smaller tumors as well as an attenuated neutralizing antibody response to MV (Figure 6), thereby indicating that the combined treatment is both directly cytostatic on the tumor, and may also augment virus treatment through inhibiting the formation of antiviral immune responses. It is likely that rapamycin treatment at continuous immunosuppressive dosages (5 mg/kg) will ablate the anti-MV immune responses even further. To date, rapamycin or its analogues have been used in combination with a number cancer therapies, including radiotherapy,36,37 and drugs such as antiestrogens,38,39 B-Raf inhibitors,40 and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors.41,42 In addition, adenovirus oncolysis has also been shown to be enhanced by systemic rapamycin administration.43,44 However, this is the first report of rapamycin directly reducing the immune response of an oncolytic virus, thus potentially enabling more effective long-term dosing.

This study extends previous animal studies that investigated the use of MV in the treatment of cancer. This syngeneic murine model allowed us to examine the effects of the treatment of both primary and metastatic tumors in a fully immunocompetent host. We were able to monitor for the first time the contribution of the immune system to the efficacy of MV treatment, as well as the contribution of the tumor microenvironment. This study underlines the challenges inherent in repeated virus treatments of a solid tumor that is capable of rapid remodeling, and demonstrates that a drug such as rapamycin can augment MV oncolysis in numerous ways, making the combination therapy more effective. We also show the comparable efficacy of a variant of MV (vMyx135KO) that is non-pathogenic for all known vertebrate hosts, thereby indicating that we need not sacrifice tumor-killing ability for the sake of increased safety, either in humans or in collateral hosts such as rabbits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, reagents, and recombinant viruses

Cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), except B16F10 cells which were grown in α-minimum essential medium (Invitrogen). BGMK cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum, while tumor cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cell lines were maintained in a medium containing 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin, at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The murine B16F10 and B16F1 melanoma,45 4T1 mammary carcinoma, and CT-26 colon adenocarcinoma cell lines were obtained from John Bell (University of Ottawa). The mammary carcinoma cell lines D2A1 (ref. 46) and the MT1A2 cell lines were also used. B16F10LacZ cells were generated by stable transfection with LacZ complementary DNA, as described earlier (Kirstein JM, Graham KC, MacKenzie LT, Johnston DE, Martin LJ, Tuck AB et al., manuscript submitted). Cells were treated in vitro with rapamycin (Calbiochem) diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma; Oakville, Ontario, CA), or Akt inhibitors X or VIII (Calbiochem). Rapamycin (>99% pure) used in in vivo experiments (LC Laboratories, Boston, MA) was diluted in 100% ethanol and further diluted in 30% ethanol for injection.

The parental MV used in this study, vMyxlac, is a version of MV (strain Lausanne; American Type Culture Collection VR-115) containing the Escherichia coli lacZ under the control of the vaccinia virus P11 promoter and inserted at an innocuous site between open reading frames M010L and M011L.47 The virus, designated as vMyxgfp, expresses enhanced green fluorescence protein under the control of a synthetic vaccinia virus early/late promoter. This green fluorescence protein cassette was inserted between open reading frames M135R and M136R of the myxoma genome.48 The recombinant virus vMyx135KO had its copy of M135R replaced by the enhanced green fluorescence protein cassette.23 All MV strains were propagated on BGMK cells.

Viral growth curves

Viral replication was analyzed by single step growth curves as previously described.11 In experiments involving drug (rapamycin or Akt inhibitors) treatment, cellular monolayers (at 85–95% confluency) were treated with 20 nmol/l rapamycin, of an appropriate dilution with dimethyl sulfoxide, 6 hours prior to infection, and the treatment was resumed after infection with virus.

Western blot analysis

The cells were infected with vMyxlac at a multiplicity of infection of 3. The cells were collected at designated time points after infection, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and subsequently lysed with appropriate lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors, after which-Western blot analysis was performed as previously described.20 Akt status was determined with monoclonal Akt and polyclonal phospho-Akt (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) polyclonal antibodies. In addition, cellular supernatants were collected and concentrated, and the production of viral proteins was monitored with polyclonal M-T7 (secreted early gene product) and monoclonal Serp-1 (secreted late gene product; Biogen, Cambridge, MA) MV antibodies. The presence of the proteins was visualized, using the appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Animals

C57BL6 mice (female, 6–8 weeks old) were supplied by Charles River Canada (St. Constant, Canada). Mice were housed in micro-isolators in groups of three to four mice within a level 2 biocontainment room of the Animal Care and Veterinary Services facility (University of Western Ontario, Ontario, Canada) in a scheduled 12 hour light/dark environment. All animal protocols were carried out according to standard operating procedures of the Animal Care and Veterinary Services (University of Western Ontario).

Mouse Protocol and Tumor Measurements

Primary tumor model

Single subcutaneous injections of 3 × 105 uninfected B16F10 cells were administered into the flanks of the mice. The mice received three IT injections at different sites in the tumor at 108 ffu each of vMyxgfp (total 3 × 108 ffu/tumor) from day 7 through to day 21 (end point). The tumor area was measured with calipers. In some experiments, B16F10 cells were pre-infected with vMyxgfp for 1 hour prior to injection.

Lung metastasis model

B16F10LacZ cells (5 × 105), diluted in 100 μl α-minimum essential medium, were injected IV into the tail veins of the recipient mice. Mice were treated with either a single IV injection or multiple ones (tail vein) of 108 ffu of vMyx135KO. In some experiments, the mice were given rapamycin intraperitoneally at 3 mg/kg every 3 days, diluted in a total volume of 50 μl of 30% ethanol. The endpoint was 14 days after inoculation with tumor cells.

When the endpoints of each study were reached, the mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine, after which a terminal bleed was performed through a cardiac puncture, after which tumors and organs were excised. Tumors, in the primary tumor model, were fixed in 10% formalin for a minimum of 48 hours before processing. Whole lungs, in the lung metastasis model, were collected in 0.1 mol/l phosphate buffer. Some organs were snap-frozen and processed for measuring viral titers. Lungs were fixed and stained for β-galactosidase activity as previously described (Kirsten, JM et al., manuscript submitted). The number of metastases on the surface of each of the five lobes was determined, after physical separation of the lobes of each lung. They were counted under a dissecting microscope (Lieca).

In order to assess the mean size of lung tumors, the lungs were fixed and placed between two slides so as to flatten the lung lobes completely. These lungs were then visualized under low magnification, and OpenLab software was used for measuring the diameter of each individual tumor. The compiled data for each lung (representing 40–150 individual tumors) were analyzed and the mean tumor diameter per lung was determined.

In a separate experiment, the metastatic tumor burden was determined using a single lobe from each animal. The equivalent lobe from each recipient mouse was removed prior to fixation, and weighed. The tissue was homogenized, and β-galatosidase activity within the tissue lysate was determined as previously described.11

Tumor sectioning and immunohistochemistry

Tumors for use in analysis of cross-sections were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours, and then processed and embedded in paraffin. The sections were exposed to an Alexa Fluor-488 conjugate green fluorescence protein antibody (1:1,000; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) in 1% normal mouse serum and 1% normal human serum, and an anti-M-T7 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:1,000) was used in 1% normal mouse serum and 1% normal human serum for 1 hour. An anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor-568-conjugated secondary antibody was used for detection. All slides were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylin-dole. The protocol for staining connective tissue and fibrin was the Lendrum method with Martius yellow-brilliant crystal scarlet-soluble blue.49

Determination of anti-MV antibody responses

B16F10LacZ cells were grown to confluence, and either left uninfected or infected with vMyx135KO at a multiplicity of infection of 3 for 48 hours. At this time point the cells were collected, and a lysate was prepared. Protein (200 μg) was run in a single large well on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel, and the separated proteins were transferred onto nitro-cellulose membrane (Amersham). Mouse serum was diluted 1:500 in 5% bovine serum albumin, and 50 μl of each was added to the chambers of a Miniblotter 28 apparatus (Immunetics, Boston, MA). The serum was incubated for 3 hours at room temperature. The presence of the proteins was visualized using horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase) and the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Perkin-Elmer).

The viral neutralization assay was performed on confluent BGMK monolayers in a 48-well plate. Briefly, sera at the indicated dilutions were incubated with vMyxlac at a multiplicity of infection of 0.001 for 30 minutes at room temperature. The mixture was then used to infect BGMK in triplicate, and the β-galactosidase was used for assessing foci formation 48 hours later, as described above.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of Canada (G.M.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant no. 42511, to A.F.C.) and the Canada Research Chairs Program (A.F.C.). G.M. holds an International Scholarship of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. M.M.S. is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship provided by the Pamela Greenaway Kohlmeier Translational Breast Cancer Research Unit of the London Regional Cancer Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dock G. Influence of complicating diseases upon leukemia. Am J Med Sci. 1904;127:563–592. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell JC, Garson KA, Lichty BD, Stojdl DF. Oncolytic viruses: programmable tumour hunters. Curr Gene Ther. 2002;2:243–254. doi: 10.2174/1566523024605582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullen JT, Tanabe KK. Viral oncolysis. Oncologist. 2002;7:106–119. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-2-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parato KA, Senger D, Forsyth PA, Bell JC. Recent progress in the battle between oncolytic viruses and tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:965–976. doi: 10.1038/nrc1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu DC, Working P, Ando D. Selectively replicating oncolytic adenoviruses as cancer therapeutics. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2002;4:435–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuruppu D, Tanabe KK. Viral oncolysis by herpes simplex virus and other viruses. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:524–531. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.5.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shmulevitz M, Marcato P, Lee PW. Unshackling the links between reovirus oncolysis, Ras signaling, translational control and cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:7720–7728. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fielding AK. Measles as a potential oncolytic virus. Rev Med Virol. 2005;15:135–142. doi: 10.1002/rmv.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo ZS, Bartlett DL. Vaccinia as a vector for gene delivery. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:901–917. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.6.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aghi M, Martuza RL. Oncolytic viral therapies—the clinical experience. Oncogene. 2005;24:7802–7816. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sypula J, Wang F, Ma Y, Bell JC, McFadden G. Myxoma virus tropism in human tumor cells. Gene Ther Mol Biol. 2004;8:108–114. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenner F. Adventures with poxviruses of vertebrates. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:123–133. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(00)00027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanford MM, Werden SJ, McFadden G. Myxoma virus in the European rabbit: interactions between the virus and its susceptible host. Vet Res. 2007;38:299–318. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrewes CH, Harisijades S. Propagation of myxoma virus in one-day-old mice. Br J Exp Pathol. 1955;36:18–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson EW, Dorn CR, Saito JK, McKercher DG. Absence of serological evidence of myxoma virus infection in humans exposed during an outbreak of myxomatosis. Nature. 1966;211:313–314. doi: 10.1038/211313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFadden G. Poxvirus tropism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:201–213. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang F, Ma Y, Barrett JW, Gao X, Loh J, Barton E, et al. Disruption of Erk-dependent type I interferon induction breaks the myxoma virus species barrier. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1266–1274. doi: 10.1038/ni1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang G, Barrett JW, Stanford M, Werden SJ, Johnston JB, Gao X, et al. Infection of human cancer cells with myxoma virus requires Akt activation via interaction with a viral ankyrin-repeat host range factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4640–4645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509341103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanford MM, Barrett JW, Nazarian SH, Werden S, McFadden G. Oncolytic virotherapy synergism with signaling inhibitors: Rapamycin increases myxoma virus tropism for human tumor cells. J Virol. 2007;81:1251–1260. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01408-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lun X, Yang W, Alain T, Shi ZQ, Muzik H, Barrett JW, et al. Myxoma virus is a novel oncolytic virus with significant antitumor activity against experimental human gliomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9982–9990. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrett JW, Alston LR, Wang F, Stanford MM, Gilbert P, Gao X, et al. Identification of host range mutants of myxoma virus with altered oncolytic potential in human glioma cells. J Neurovirol. 2007 doi: 10.1080/13550280701591526. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett JW, Sypula J, Wang F, Alston LR, Shao Z, Gao X, et al. M135R is a novel cell surface virulence factor of myxoma virus. J Virol. 2007;81:106–114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01633-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cameron C, Hota-Mitchell S, Chen L, Barrett J, Cao JX, Macaulay C, et al. The complete DNA sequence of myxoma virus. Virology. 1999;264:298–318. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barry M, Hnatiuk S, Mossman K, Lee SF, Boshkov L, McFadden G. The myxoma virus M-T4 gene encodes a novel RDEL-containing protein that is retained within the endoplasmic reticulum and is important for the productive infection of lymphocytes. Virology. 1997;239:360–377. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YL, Law PY, Loh HH. Inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling: an emerging paradigm for targeted cancer therapy. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:575–589. doi: 10.2174/156801105774574649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, Ittmann MM, Ayala G, Tsai MJ, Amato RJ, Wheeler TM, et al. The emerging role of the PI3-K-Akt pathway in prostate cancer progression. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:108–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKee TD, Grandi P, Mok W, Alexandrakis G, Insin N, Zimmer JP, et al. Degradation of fibrillar collagen in a human melanoma xenograft improves the efficacy of an oncolytic herpes simplex virus vector. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2509–2513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganesh S, Gonzalez Edick M, Idamakanti N, Abramova M, Vanroey M, Robinson M, et al. Relaxin-expressing, fiber chimeric oncolytic adenovirus prolongs survival of tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4399–4407. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JH, Lee YS, Kim H, Huang JH, Yoon AR, Yun CO. Relaxin expression from tumor-targeting adenoviruses and its intratumoral spread, apoptosis induction, and efficacy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1482–1493. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brenner RJ. MBI: M(I)BI agonistes or a new chapter? Breast J. 2007;13:1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2006.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:563–572. doi: 10.1038/nrc865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lun XQ, Zhou H, Alain T, Sun B, Wang L, Barrett JW, et al. Targeting human medulloblastoma: oncolytic virotherapy with myxoma virus is enhanced by rapamycin. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8818–8827. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Georgakis GV, Younes A. From Rapa Nui to rapamycin: targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR for cancer therapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:131–140. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guba M, Koehl GE, Neppl E, Doenecke A, Steinbauer M, Schlitt HJ, et al. Dosing of rapamycin is critical to achieve an optimal antiangiogenic effect against cancer. Transpl Int. 2005;18:89–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2004.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paglin S, Lee NY, Nakar C, Fitzgerald M, Plotkin J, Deuel B, et al. Rapamycin-sensitive pathway regulates mitochondrial membrane potential, autophagy, and survival in irradiated MCF-7 cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11061–11070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weppler SA, Krause M, Zyromska A, Lambin P, Baumann M, Wouters BG. Response of U87 glioma xenografts treated with concurrent rapamycin and fractionated radiotherapy: possible role for thrombosis. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Treeck O, Wackwitz B, Haus U, Ortmann O. Effects of a combined treatment with mTOR inhibitor RAD001 and tamoxifen in vitro on growth and apoptosis of human cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadler TM, Gavriil M, Annable T, Frost P, Greenberger LM, Zhang Y. Combination therapy for treating breast cancer using antiestrogen, ERA-923, and the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, temsirolimus. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:863–873. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molhoek KR, Brautigan DL, Slingluff CL., Jr. Synergistic inhibition of human melanoma proliferation by combination treatment with B-Raf inhibitor BAY43-9006 and mTOR inhibitor Rapamycin. J Transl Med. 2005;3:39. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buck E, Eyzaguirre A, Brown E, Petti F, McCormack S, Haley JD, et al. Rapamycin synergizes with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor erlotinib in non-small-cell lung, pancreatic, colon, and breast tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2676–2684. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doherty L, Gigas DC, Kesari S, Drappatz J, Kim R, Zimmerman J, et al. Pilot study of the combination of EGFR and mTOR inhibitors in recurrent malignant gliomas. Neurology. 2006;67:156–158. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223844.77636.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukashev AN, Fuerer C, Chen MJ, Searle P, Iggo R. Late expression of nitroreductase in an oncolytic adenovirus sensitizes colon cancer cells to the prodrug CB1954. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:1473–1483. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Homicsko K, Lukashev A, Iggo RD. RAD001 (everolimus) improves the efficacy of replicating adenoviruses that target colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6882–6890. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fidler IJ, Nicolson GL. Organ selectivity for implantation survival and growth of B16 melanoma variant tumor lines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57:1199–1202. doi: 10.1093/jnci/57.5.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morris VL, Tuck AB, Wilson SM, Percy D, Chambers AF. Tumor progression and metastasis in murine D2 hyperplastic alveolar nodule mammary tumor cell lines. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1993;11:103–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00880071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Opgenorth A, Graham K, Nation N, Strayer D, McFadden G. Deletion analysis of two tandemly arranged virulence genes in myxoma virus, M11L and myxoma growth factor. J Virol. 1992;66:4720–4731. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4720-4731.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnston JB, Barrett JW, Chang W, Chung CS, Zeng W, Masters J, et al. Role of the serine-threonine kinase PAK-1 in myxoma virus replication. J Virol. 2003;77:5877–5888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5877-5888.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisseler-Eckhoff A, Muller KM. Lendrum (-MSB) staining for fibrin identification in sealed skin grafts. Pathol Res Pract. 1994;190:444–448. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.