Abstract

There is a need to better understand the post-treatment concerns of the nearly 14 million cancer survivors alive in the United States today and their receipt of care.

Methods

Using data from 2910 post-treatment cancer survivors from the 2006 or 2010 LIVESTRONG Surveys, we examined physical, emotional, and practical concerns, receipt of care, and trends in these outcomes at the population level.

Results

89% of respondents reported at least one physical concern (67% received associated post-treatment care); 90% reported at least one emotional concern (47% received care); and 45% reported at least one practical concern (36% received care). Female survivors, younger survivors, those who received more intensive treatment, and survivors without health insurance often reported a higher burden of post-treatment concerns though were less likely to have received post-treatment care.

Conclusions

These results reinforce the importance of post-treatment survivorship and underscore the need for continued progress in meeting the needs of this population. Efforts to increase the availability of survivorship care are extremely important to improve the chances of people affected by cancer living as well as possible in the post-treatment period.

Promoting health and wellness among cancer survivors is imperative to our nation’s public health. There are nearly 14 million cancer survivors alive in the United States today (Siegel et al., 2012). The first decade of the new millennium saw a significant increase in cancer survivorship research (Institute of Medicine, 2005, 2008; Rowland, Hewitt, & Ganz, 2006) showing that survivors encounter a variety of physical, emotional, and practical concerns in the post-treatment period.

Some of the most common physical concerns survivors encounter in the post-treatment period are fatigue (Schmidt et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2011), pain (Chapman, 2011; Moryl, Coyle, Essandoh, & Glare, 2010), and sleep problems (Humpel & Iverson, 2010). In a study of over 45,000 Canadian cancer survivors who were, on average, about four years post-diagnosis, 75 percent reported to be dealing with tiredness and about half reported pain (Barbera et al., 2010). A number of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments exist for fatigue, pain, and sleep problems in cancer survivors, but these concerns are often underdiagnosed and treatment is often underutilized (Pachman, Barton, Swetz, & Loprinzi, 2012). Cognitive disruption is also consistently reported by survivors (15 to 25 percent) after treatment with chemotherapy (labeled here as a “physical” concern due to increasing evidence that the etiology of cognitive disruption is linked to physical reductions in gray matter or activation of neural structures; (Ahles, Root, & Ryan, 2012)).

Common emotional concerns among post-treatment survivors include fear of recurrence (Thewes et al., 2011); emotional distress (Gao, Bennett, Stark, Murray, & Higginson, 2010); and symptoms of post-traumatic stress (Mehnert & Koch, 2008; Rusiewicz, 2008; Smith et al., 2011). Andrykowski and colleagues (Andrykowski, Lykins, & Floyd, 2008) described four possible trajectories of emotional outcomes relative to pre-cancer emotional health following a cancer diagnosis, including growth, recovery, impairment, or deterioration. Several studies have shown that a substantial minority of cancer survivors experience emotional impairment or deterioration in the wake of cancer, and that in particular, the transition out of treatment is a challenging time when survivors encounter emotional challenges (A. Stanton, 2012).

Finally, post-treatment cancer survivors face practical concerns relating to finances, insurance, employment, and education (Hauglann, Benth, Fossa, & Dahl, 2012; Kirchhoff et al., 2012). Physical limitations at work are more common among survivors who were treated with chemotherapy (Taskila T, 2007). And in a study of post-treatment breast cancer survivors, insurance premiums increased in the six months after diagnosis, and economic burden was negatively associated with quality of life (Meneses, Azuero, Hassey, McNees, & Pisu, 2012).

In response to the growing number of survivors who live to experience these concerns, post-treatment care is beginning to shift from a primary focus on surveillance for recurrence or new cancers to include management of post-treatment concerns (Hudson, Landier, & Ganz, 2011). Survivorship care was the focus of the Institute of Medicine’s 2005 Lost in Transition report (Institute of Medicine, 2005), which emphasized the need for coordination between health care providers to better address survivors’ post-treatment needs (Grunfeld & Earle, 2010a). Post-treatment survivorship care is likely to involve cancer care providers, specialty providers and the survivor’s primary care provider (PCP; (Grunfeld & Earle, 2010b; Howell et al., 2012; McCabe et al., 2013)). Poor coordination between these providers may undermine the receipt of quality care (Forsythe et al., 2012; Harrington, Hansen, Moskowitz, Todd, & Feuerstein, 2010; Potosky et al., 2011; Silver, 2011). Furthermore, care may not be available from the health care system to meet all post-treatment concerns (e.g., for practical concerns; (Miedema & Easley, 2012)), and availability of care is also threatened by the growing number of survivors outstripping oncology provider supply (Erikson, Salsberg, Forte, Bruinooge, & Goldstein, 2007).

These circumstances raise questions including: are the post-treatment experiences of survivors who were diagnosed before the increased attention to cancer survivorship different from those diagnosed after? And is the proportion of survivors receiving care for post-treatment concerns higher among survivors diagnosed after the Lost in Transition IOM report compared to those diagnosed before? Data from the LIVESTRONG Surveys for People Affected by Cancer are uniquely positioned to shed light on these important questions. In 2006, LIVESTRONG fielded their first surveillance effort focused on the experiences of post-treatment cancer survivors (Rechis R, 2010) followed by a second survey in 2010 (R. Rechis, Reynolds, K.A., Beckjord, E.B., Nutt, S., Burns, R.M., Schaefer, J.S., 2011a). Given the need for a greater understanding of population-level trends in post-treatment care delivery (Richardson et al., 2011), we used the LIVESTRONG surveys to describe physical, emotional, and practical post-treatment concerns and receipt of post-treatment care among a large and varied group of post-treatment cancer survivors within five years of diagnosis. We also report on population-level trends in post-treatment concerns and associated receipt of care for a survivors diagnosed before (2000–2005) or after (2006–2010) the release of the Lost in Transition IOM report.

Methods

Procedure

In 2006, LIVESTRONG fielded the LIVESTRONG Survey for Post-Treatment Cancer Survivors. The survey instrument was designed through a process that engaged cancer survivors and experts in survey methodology and oncology through peer review, three focus groups, and a pilot test. The survey queried post-cancer onset physical, emotional, and practical concerns as well as receipt of care for concerns. The concerns cited in the survey were initially included because: 1) they had been used in other surveys (e.g., the Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors Scale (QLACS; (Avis et al., 2005); the National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey (Hesse, Moser, Rutten, & Kreps, 2006)); 2) they were identified by the expert advisors as known late effects; and/or 3) they were addressed by LIVESTRONG educational resources. The survey was repeated in 2010 and collected data from a new sample of respondents. Two reports provide details on both administrations and copies of survey instruments (R. Rechis, 2006; R. Rechis, Reynolds, K.A., Beckjord, E.B., Nutt, S., Burns, R.M., Schaefer, J.S., 2011b).

The 2006 survey was fielded from March 2006 through February 2007, and the 2010 survey was fielded from June 2010 through March 2011. Both surveys were reviewed and approved by the Western Institutional Review Board. In 2006, the survey was available both online and in paper form (41 completed on paper). The 2010 survey was fielded exclusively online. For both administrations, surveys were available on LIVESTRONG.org. LIVESTRONG constituents were notified about the survey through emails, Twitter and Facebook posts. Additionally, LIVESTRONG reached out to partner organizations (e.g., the American Cancer Society) and state cancer coalitions who shared information about the survey with their constituents. Finally, LIVESTRONG worked with Comprehensive Cancer Centers, (Campbell et al., 2011; Shapiro et al., 2009) to share the survey with patients.

Participants

A total of 6593 post-treatment cancer survivors responded to either the 2006 (n=2307) or 2010 (n=4286) LIVESTRONG surveys. In both surveys, post-treatment cancer survivors were defined as respondents who reported to be finished with their cancer treatment (those managing cancer as a chronic condition or taking medication (e.g., tamoxifen) to prevent a recurrence were included). For these analyses, the LIVESTRONG survey samples were restricted to survivors who were within five years of diagnosis (diagnosed between 2001 and 2005 for 2006 survey respondents or between 2006 and 2010 for 2010 respondents).

Figure 1 gives a detailed overview of how the study samples were derived. Respondents were excluded if they or if they had been diagnosed more than five years before the survey (n=2565). Compared to survivors diagnosed within five years of taking their survey (in 2006 or 2010), survivors diagnosed six years or more before the survey had more years of education (p = 0.05); were less likely to be married; were less likely to have been diagnosed with prostate, colorectal, or breast cancer or Hodgkin lymphoma; and were older (all p<0.01). They also differed on annual income (p<0.01), but this was driven by more survivors who were diagnosed six years or more before taking the survey declining to report annual income data. Longer-term post-treatment survivors did not differ from the survey sample with respect to gender, race/ethnicity, health insurance status, or type of treatment received.

Figure 1.

Study Sample.

Further respondents were excluded if they were missing their date of diagnosis (n=427); had a recurrence or were missing recurrence data (n=427); or if they were missing data on post-treatment concerns (n=64); sociodemographic data (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, annual income; marital status; n=176); or cancer-related data (type of cancer; time since diagnosis; treatment received; n=24). The final sample included 2910 post-treatment cancer survivors; 1130 from the 2006 survey and 1780 from the 2010 survey.

Measures

Physical, Emotional, and Practical Concerns

Questions about post-treatment physical, emotional, and practical issues were presented as a series of questions starting with the following statement: “Since completing treatment, have any of the following statements been true for you as a result of your experience with cancer?” The statements that followed included both a low-literacy description of the concern (e.g., “I have had trouble with my heart”) and a reported diagnosis (e.g., “A doctor has told me I have a heart problem”). Endorsement of any of the descriptors (yes/no) was counted as reporting the issue as a “concern.”

A total of 13 physical concerns were included in both the 2006 and 2010 surveys: problems with heart; lungs; vision; hearing; oral health; lymphedema; neuropathy; thyroid problems; incontinence; sexual dysfunction; pain; cognitive problems; and fatigue. Emotional concerns included emotional distress; grief and identity issues; spiritual concerns; fear of recurrence; social anxiety; concerns about family risk; and concerns about body image. Practical concerns included debt; school problems (for survivors in school at time of diagnosis; n=186); and employment problems (for survivors employed at time of diagnosis; n=2102).

Receipt of care

Each time a respondent endorsed a specific concern, they were asked if they received care for that concern. Receipt of care was defined as having received care for any physical concern; for any emotional concern; and for any practical concern, representing a very inclusive approach to defining care received.

Sociodemographic and medical variables

Additional variables included age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, annual income, marital status, type of cancer, treatment received, health insurance status, and time since diagnosis.

Analytic approach

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize physical, emotional, and practical post-treatment concerns and associated receipt of care. Linear regression was used to model the number of post-treatment physical or emotional concerns reported; logistic regression was used to model odds of reporting practical concerns and odds of receiving post-treatment care for physical, emotional, or practical concerns. Multivariate models included survey year and time since diagnosis as well as sociodemographic and medical covariates. The survey year regression coefficient was interpreted as an indicator of whether the model outcome (post-treatment concern or receipt of care) was significantly different (i.e., detection of a trend) between the two survey administrations after adjusting for sociodemographic and medical differences between the two survey samples. If survey year was significant, the regression was re-run, stratified by survey year. When survey year was not significant, the regression was re-run without survey year in the model using the entire study population to understand the sociodemographic and medical correlates of post-treatment concerns and receipt of care.

Results

Sample description

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and medical characteristics of the sample, overall, and by survey administration. The p values reported show where there were sociodemograhpic and medical characteristic differences between survivors from the 2006 and 2010 surveys. On average, these post-treatment survivors were 47 years old; 65 percent were female; and nearly 90 percent reported White race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Medical Characteristics of the Study Sample.

| Whole Sample N=2910 |

2006 Respondents N=1130 |

2010 Respondents N=1780 |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 47.29 (11.69) | 46.67 (11.52) | 47.69 (11.79) | =0.02 |

| Gender | Female | 65.1% | 68.8% | 62.8% | <0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 89.7% | 91.6% | 88.5% | <0.01 |

| Other | 10.3% | 8.4% | 11.5% | ||

| Education | Less than college | 22.9% | 20.8% | 24.3% | =0.02 |

| Some college | 22.7% | 21.8% | 23.3% | ||

| College degree | 31% | 31.2% | 30.8% | ||

| Graduate degree | 23.4% | 26.2% | 21.6% | ||

| Annual income | <=$40K | 14.9% | 14% | 15.6% | <0.01 |

| $41K – $60K | 14.3% | 16.7% | 12.7% | ||

| $61K – $80K | 13.8% | 16.4% | 12.2% | ||

| $81K – $100K | 12.6% | 12.5% | 12.8% | ||

| $101K – $120K | 11% | 11.8% | 10.6% | ||

| $121K or more | 18.8% | 18.8% | 18.8% | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 14.5% | 9.9% | 17.4% | ||

| Marital status | Single | 21.2% | 26.4% | 18% | <0.01 |

| Married/Partnered | 71.1% | 71.5% | 70.9% | ||

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated/Prefer not to answer | 7.6% | 2.1% | 11.1% | ||

| Type of cancer | Breast | 32% | 34.6% | 30.3% | <0.01 |

| Testicular | 7.9% | 6.9% | 8.5% | ||

| Colorectal | 6.9% | 7% | 6.9% | ||

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 5.7% | 6.8% | 5% | ||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 3.6% | 3.9% | 3.4% | ||

| Prostate | 7% | 5% | 8.3% | ||

| Other | 37% | 35.8% | 37.8% | ||

| Treatment | No chemotherapy | 36.9% | 28.3% | 42.4% | <0.01 |

| Only chemotherapy | 10.2% | 11.1% | 9.7% | ||

| Chemotherapy plus radiation and/or surgery | 52.9% | 60.6% | 48% | ||

| Years since diagnosis | Mean (SD) | 1.62 (1.30) | 1.70 (1.31) | 1.57 (1.29) | <0.01 |

| Health insurance | Yes | 96.1% | 96% | 96.6% | n.s. |

| Year of diagnosis | 2001 | 3.4% | 8.8% | n/a | |

| 2002 | 4.5% | 11.6% | n/a | ||

| 2003 | 7.4% | 19% | n/a | ||

| 2004 | 13% | 33.5% | n/a | ||

| 2005 | 10.5% | 27.1% | n/a | ||

| 2006 | 8.5% | n/a | 13.8% | ||

| 2007 | 10.6% | n/a | 17.4% | ||

| 2008 | 13.5% | n/a | 22.1% | ||

| 2009 | 18.1% | n/a | 29.6% | ||

| 2010 | 10.5% | n/a | 17.2% | ||

For the combined sample, early one-third was breast cancer survivors. About 40 percent had not received chemotherapy, though more than half received chemotherapy plus surgery and/or radiation. On average, survivors were 1.62 years post-diagnosis.

Descriptive analyses

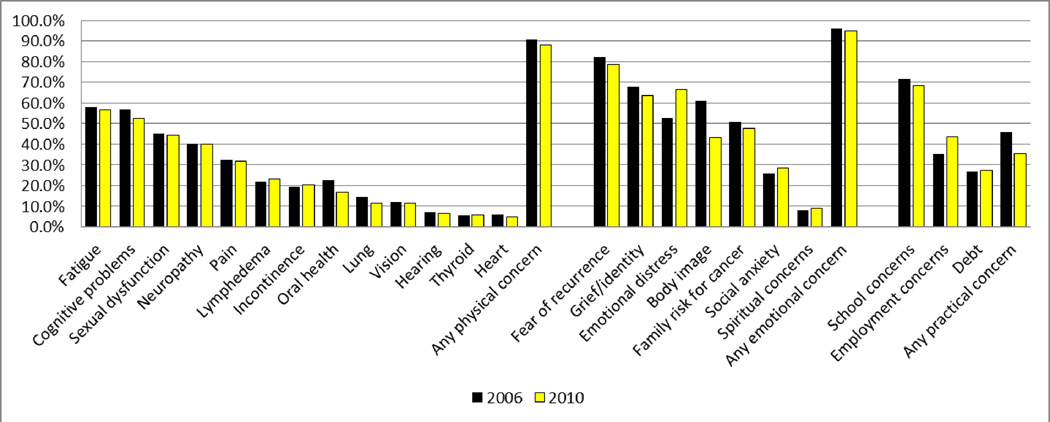

Figure 2 shows the distribution of physical, emotional, and practical post-treatment concerns separately for the 2006 and 2010 survey samples.

Figure 2.

Physical, Emotional, and Practical Concerns in the 2006 and 2010 Samples.

For physical concerns, in both surveys, more than half of the respondents reported concerns about fatigue and cognitive problems and at least one-third reported problems with sexual dysfunction; neuropathy; or pain. In 2006, over 90% of respondents reported at least one physical concern; in 2010 it was 88%.

In both samples, for emotional concerns, the majority of respondents (~80%) reported fears of recurrence, while more than 60 percent reported issues with grief or identity (e.g., lost sense of identity; grief about the death of other cancer patients) or emotional distress. About half reported concerns about body image or risk of cancer for family members. In 2006, 95.8% of the sample reported at least one emotional concern; it was 94.8 in 2010.

For the respondents who were in school when diagnosed, in 2006 over 70 percent said they had post-treatment concerns about school; in 2010 it was 68.6%. For the respondents who were working when diagnosed, in 2006, 35.3% reported concerns about employment; in 2010 it was 43.6%. In both years, just over one-quarter of the sample reported post-treatment concerns about debt. About half of respondents in 2006 reported at least one practical concern (45.8%) and about one-third (35.5%) reported at least one practical concern in 2010.

Figure 3 shows, for post-treatment survivors who reported each concern, the percentage who reported to receive care for each concern.

Figure 3.

Percentage of Survivors who Reported a Concern who Received Care for that Concern in the 2006 and 2010 Samples.

The percentage of survivors who reported to receive care for each concern varied widely. It is worth noting that the frequency with which care was received for any given concern was not directly correlated with how often the concern was reported. That is, for some of the most commonly reported concerns (shown in rank-order in Figure 3), receipt of care was low (e.g., cognitive problems). In both surveys, receipt of care was most common for physical concerns, then emotional, then practical. Among post-treatment survivors who reported any physical concerns, 68.7% received care in 2006 and 66.0% received care in 2010. For those who reported any emotional concerns, only about half received care (50.6% in 2006; 45.0% in 2010). For those who reported any practical concerns, less than half received care (36.1% in 2006; 44.2% in 2010).

Regression analyses

Physical and emotional concerns

Multivariate linear regression was used to model the average number of post-treatment physical and emotional concerns, separately. In both models, the coefficient for survey year was nonsignificant, indicating that there was not a significant difference in the average number of physical or emotional concerns reported by survivors from the 2006 versus the 2010 survey. Table 2 shows the results of the models without survey year.

Table 2.

Linear Regression Models of Post-Treatment Physical and Emotional Concerns.

| Number of Physical Concerns (Model Adjusted R2 = 0.42) |

Number of Emotional Concerns (Model Adjusted R2 = 0.11) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized β | p | Standardized β | p | ||

| Age | (Years) | −0.05 | <0.01 | −0.23 | <0.01 |

| Gender | Female | 0.13 | <0.01 | 0.15 | <0.01 |

| Male | reference | reference | |||

| Education | Less than college | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.94 |

| Some college | 0.04 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.44 | |

| College | 0.01 | 0.70 | 0.01 | 0.84 | |

| Graduate degree | reference | reference | |||

| Annual income | Less than $40K | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| $41K to less than $60K | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.54 | |

| $61K to less than $80K | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.79 | |

| $81K to less than $100K | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.33 | |

| $101K to less than $120K | 0.00 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.53 | |

| Prefer not to answer | −0.02 | 0.27 | −0.02 | 0.50 | |

| $120K or more | reference | reference | |||

| Marital status | Single | −0.06 | <0.01 | −0.02 | 0.45 |

| Widow/Divorce/Separate/Prefer not to Answer | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | <0.01 | |

| Married/Partnered | reference | reference | |||

| Race/ethnicity | Non-White | −0.01 | 0.77 | −0.01 | 0.42 |

| White | reference | reference | |||

| Treatment | No chemotherapy | −0.35 | <0.01 | −0.13 | <0.01 |

| Chemotherapy only | −0.08 | <0.01 | −0.04 | 0.03 | |

| Chemotherapy plus other | reference | reference | |||

| Type of cancer | Testicular | −0.09 | <0.01 | −0.10 | <0.01 |

| Colorectal | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | −0.01 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.91 | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.05 | |

| Prostate | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.88 | |

| Other type | 0.02 | 0.51 | −0.05 | 0.02 | |

| Breast | reference | reference | |||

| Time since diagnosis | (Years) | 0.04 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Health insurance | No | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.18 |

| Yes | reference | reference |

For both physical and emotional concerns, younger respondents and women reported more concerns, as did survivors who received chemotherapy plus surgery and/or radiation. Respondents who were married reported more physical concerns than single respondents, but fewer physical and emotional concerns than respondents who had previously been married. Compared to breast cancer survivors, testicular cancer survivors reported fewer physical and emotional concerns; colorectal cancer survivors reported fewer physical concerns. Finally, for physical concerns, nearly all respondents who reported incomes lower than $100,000 per year reported more concerns than those who earned $120,000 or more. Survivors further from time of diagnosis and those without health insurance reported more physical concerns.

Practical concerns

Logistic regression was used to model the odds of reporting the practical concerns of employment issues and debt (Table 3). School concerns were not modeled due to the small number of respondents who were in school at time of diagnosis (n=186). After adjusting for covariates, survey year was associated with reporting employment concerns: odds of reporting employment concerns were significantly higher in 2010 compared 2006 (OR=1.66, 95% CI=1.37, 2.01; p<0.01). In the 2006 survey, employment concerns were only related to medical variables. Respondents who had received less treatment had significantly lower odds of reporting employment concerns, and compared to breast cancer survivors, respondents who had non-Hodgkin lymphoma; Hodgkin lymphoma; or a type of cancer not listed in Table 1 had higher odds of employment concerns. In the 2010 sample, women had higher odds of reporting employment concerns as did respondents who reported annual incomes at or below $80,000 per year, and respondents who did not receive chemotherapy had significantly lower odds of reporting employment concerns than respondents who received chemotherapy plus surgery and/or radiation.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models of Post-Treatment Employment and Debt Concerns.

| Odds of Reporting Employment Concerns, 2006† |

Odds of Reporting Employment Concerns, 2010†† |

Odds of Reporting Debt Concerns††† |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age | (Years) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.69 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | 0.06 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | <0.01 |

| Gender | Female | 1.10 (0.74, 1.62) | 0.65 | 1.62 (1.15, 2.26) | <0.01 | 1.16 (0.91, 1.49) | 0.22 |

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Education | Less than college | 0.67 (0.44, 1.04) | 0.07 | 0.95 (0.65, 1.39) | 0.80 | 1.60 (1.21, 2.12) | <0.01 |

| Some college | 0.71 (0.47, 1.09) | 0.12 | 1.17 (0.81, 1.70) | 0.40 | 1.78 (1.35, 2.32) | <0.01 | |

| College | 0.73 (0.50, 1.07) | 0.11 | 1.28 (0.91, 1.80) | 0.16 | 1.31 (1.00, 1.70) | 0.05 | |

| Graduate degree | 1.00 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 0.28 | 1.00 | <0.01 | |

| Annual income | Less than $40K | 1.85 (1.00, 3.42) | 0.05 | 2.01 (1.26, 3.21) | <0.01 | 5.54 (3.85, 7.98) | <0.01 |

| $41K to less than $60K | 1.35 (0.81, 2.27) | 0.25 | 1.78 (1.14, 2.78) | 0.01 | 4.17 (2.94, 5.92) | <0.01 | |

| $61K to less than $80K | 1.24 (0.76, 2.04) | 0.39 | 1.77 (1.14, 2.76) | 0.01 | 2.88 (2.03, 4.10) | <0.01 | |

| $81K to less than $100K | 1.67 (0.99, 2.79) | 0.05 | 1.28 (0.82, 1.98) | 0.28 | 2.25 (1.56, 3.24) | <0.01 | |

| $101K to less than $120K | 0.75 (0.43, 1.31) | 0.32 | 1.00 (0.64, 1.57) | 0.99 | 1.55 (1.04, 2.31) | 0.03 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1.08 (0.60, 1.94) | 0.81 | 1.10 (0.73, 1.68) | 0.64 | 2.00 (1.39, 2.88) | <0.01 | |

| $120K or more | 1.00 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 | <0.01 | |

| Marital status | Single | 1.20 (0.83, 1.72) | 0.33 | 0.90 (0.63, 1.28) | 0.56 | 0.68 (0.53, 0.86) | <0.01 |

| Widow/Divorce/Separate/Prefer not to Answer | 0.22 (0.05, 1.02) | 0.05 | 0.87 (0.58, 1.32) | 0.52 | 1.53 (0.11, 2.11) | <0.01 | |

| Married/Partnered | 1.00 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.00 | <0.01 | |

| Race/ethnicity | Non-White | 0.69 (0.39, 1.22) | 0.20 | 1.09 (0.74, 1.60) | 0.67 | 1.24 (0.94, 1.64) | 0.13 |

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Treatment | No chemotherapy | 0.65 (0.46, 0.94) | 0.02 | 0.51 (0.38, 0.68) | <0.01 | 0.54 (0.44, 0.67) | <0.01 |

| Chemotherapy only | 0.49 (0.29, 0.82) | <0.01 | 1.81 (0.76, 1.83) | 0.46 | 0.85 (0.63, 1.16) | 0.31 | |

| Chemotherapy plus other | 1.00 | <0.01 | 1.00 | <0.01 | 1.00 | <0.01 | |

| Type of cancer | Testicular | 0.94 (0.44, 2.03) | 0.88 | 1.26 (0.69, 2.29) | 0.45 | 1.00 (0.64, 1.58) | 0.99 |

| Colorectal | 1.29 (0.72, 2.34) | 0.40 | 1.46 (0.88, 2.41) | 0.14 | 1.23 (0.85, 1.79) | 0.27 | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 2.12 (1.11, 4.06) | 0.02 | 0.68 (0.36, 1.25) | 0.21 | 1.54 (1.02, 2.32) | 0.04 | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 2.11 (1.00, 4.43) | 0.05 | 1.20 (0.59, 2.44) | 0.61 | 1.48 (0.91, 2.41) | 0.12 | |

| Prostate | 0.35 (0.11, 1.14) | 0.08 | 0.83 (0.42, 1.65) | 0.60 | 0.80 (0.44, 1.43) | 0.45 | |

| Other type | 2.09 (1.42, 3.06) | <0.01 | 1.13 (0.80, 1.58) | 0.49 | 1.31 (1.04, 1.65) | 0.02 | |

| Breast | 1.00 | <0.01 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.06 | |

| Time since diagnosis | (Years) | 0.97 (0.87, 1.08) | 0.52 | 1.08 (0.98, 1.19) | 0.10 | 1.05 (0.98, 1.13) | 0.13 |

| Health insurance | No | 2.00 (0.85, 4.71) | 0.11 | 1.25 (0.65, 2.42) | 0.51 | 2.12 (1.38, 3.26) | <0.01 |

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

The 2006 model of employment concerns includes the 917 respondents from the 2006 survey who were working at time of diagnosis.

The 2010 model of employment concerns includes the 1185 respondents from the 2010 survey who were working at time of diagnosis.

The model of debt concerns includes all respondents from both survey administrations (n=2910).

Odds of reporting debt concerns did not significantly differ by survey year, and decreased as respondents got older. Respondents with less than a graduate education had higher odds of reporting debt concerns as did respondents in all income categories lower than $120,000 per year. Compared to married respondents, single respondents had lower odds of debt concern while respondents who were widowed, separated, or divorced (or who preferred not to report marital status) had over 1.5 times the odds of reporting debt concerns. Finally, respondents who did not receive chemotherapy had half the odds of reporting debt concerns compared to respondents who received chemotherapy plus surgery and/or radiation, and survivors without health insurance had over two times the odds of reporting debt concerns as survivors who were insured.

Receipt of post-treatment care

Table 4 shows the logistic regression models of receipt of care for post-treatment physical, emotional, or practical concerns. For receipt of care for physical and practical concerns, the coefficient for survey year was nonsignificant; however, odds of receiving post-treatment emotional care were significantly lower in 2010 (OR=0.84, 95% CI=0.71, 1.00; p=0.04).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Models of Receipt of Post-Treatment Care.

| Odds of Receiving Care for Physical Concerns |

Odds of Receiving Care for Emotional Concerns, 2006 |

Odds Receiving Care for Emotional Concerns, 2010 |

Odds Receiving Care for Practical Concerns |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age | (Years) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.35 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.99 | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | 0.03 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.42 |

| Gender | Female | 0.83 (0.63, 1.08) | 0.15 | 1.30 (0.90, 1.89) | 0.16 | 1.62 (1.21, 2.17) | <0.01 | 0.89 (0.65, 1.23) | 0.49 |

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Education | Less than college | 0.68 (0.51, 0.90) | <0.01 | 0.62 (.042, 0.92) | 0.02 | 0.76 (0.55, 1.04) | 0.08 | 0.79 (0.54, 1.14) | 0.79 |

| Some college | 0.92 (0.69, 1.23) | 0.58 | 0.69 (0.47, 1.02) | 0.06 | 1.01 (0.74, 1.38) | 0.93 | 0.88 (0.61, 1.27) | 0.50 | |

| College | 0.78 (0.60, 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.95 (0.68, 1.34) | 0.95 | 1.21 (0.91, 1.60) | 0.20 | 0.97 (0.69, 1.36) | 0.84 | |

| Graduate degree | 1.00 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.55 | |

| Annual income | Less than $40K | 1.25 (0.86, 1.81) | 0.24 | 1.64 (0.96, 2.81) | 0.07 | 0.89 (0.61, 1.31) | 0.56 | 1.63 (1.02, 2.60) | 0.04 |

| $41K to less than $60K | 1.24 (0.88, 1.75) | 0.23 | 1.53 (0.97, 2.41) | 1.53 | 0.72 (0.49, 1.06) | 0.09 | 1.54 (0.98, 2.41) | 0.06 | |

| $61K to less than $80K | 0.93 (0.66, 1.29) | 0.65 | 1.10 (0.71, 1.71) | 0.66 | 0.99 (0.67, 1.45) | 0.95 | 1.24 (0.78, 2.00) | 0.37 | |

| $81K to less than $100K | 0.90 (0.64, 1.24) | 0.49 | 1.53 (0.96, 2.45) | 0.08 | 1.27 (0.88, 1.84) | 0.21 | 1.10 (0.67, 1.79) | 0.72 | |

| $101K to less than $120K | 0.77 (0.55, 1.09) | 0.14 | 0.92 (0.58, 1.48) | 0.73 | 0.90 (0.61, 1.33) | 0.60 | 1.38 (0.82, 2.30) | 0.22 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 0.95 (0.68, 1.32) | 0.75 | 1.10 (0.66, 1.83) | 0.73 | 1.14 (0.81, 1.60) | 0.47 | 1.31 (0.81, 2.11) | 0.27 | |

| $120K or more | 1.00 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 0.39 | |

| Marital status | Single | 1.04 (0.81, 1.35) | 0.74 | 0.74 (0.53, 1.04) | 0.08 | 0.98 (0.73, 1.32) | 0.90 | 1.01 (0.75, 1.36) | 0.94 |

| Widow/Divorce/Separate/Prefer not to Answer | 1.07 (0.72, 1.57) | 0.75 | 1.15 (0.45, 2.95) | 0.77 | 1.07 (0.76, 1.50) | 0.72 | 1.11 (0.72, 1.72) | 0.63 | |

| Married/Partnered | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.88 | |

| Race/ethnicity | Non-White | 0.85 (0.63, 1.15) | 0.28 | 0.96 (0.62, 1.52) | 0.86 | 1.16 (0.84, 1.62) | 0.36 | 1.03 (0.71, 1.48) | 0.89 |

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Treatment | No chemotherapy | 1.46 (1.16, 1.84) | <0.01 | 1.05 (0.77, 1.45) | 0.75 | 0.81 (0.64, 1.03) | 0.09 | 0.78 (0.58, 1.05) | 0.11 |

| Chemotherapy only | 0.64 (0.46, 0.89) | <0.01 | 0.87 (0.56, 1.36) | 0.54 | 0.75 (0.51, 1.11) | 0.15 | 0.86 (0.58, 1.26) | 0.44 | |

| Chemotherapy plus other | 1.00 | <0.01 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.24 | |

| Type of cancer | Testicular | 0.48 (0.30, 0.78) | <0.01 | 0.66 (0.33, 1.34) | 0.25 | 0.69 (0.40, 1.19) | 0.18 | 1.43 (0.80, 2.58) | 0.23 |

| Colorectal | 0.94 (0.64, 1.39) | 0.76 | 1.23 (0.72, 2.10) | 0.45 | 0.89 (0.58, 1.39) | 0.62 | 0.75 (0.45, 1.25) | 0.28 | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1.19 (0.75, 1.89) | 0.45 | 0.93 (0.52, 1.66) | 0.80 | 0.85 (0.50, 1.43) | 0.54 | 1.25 (0.73, 2.14) | 0.43 | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1.03 (0.60, 1.76) | 0.92 | 1.12 (0.54, 2.34) | 0.76 | 0.60 (0.32, 1.13) | 0.11 | 1.40 (0.77, 2.53) | 0.27 | |

| Prostate | 1.98 (1.20, 3.28) | <0.01 | 0.40 (0.17, 0.95) | 0.04 | 1.00 (0.59, 1.72) | 0.99 | 0.97 (0.40, 2.29) | 0.94 | |

| Other type | 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | 0.73 | 1.12 (0.80, 1.56) | 0.51 | 0.99 (0.76, 1.31) | 0.99 | 1.29 (0.94, 1.77) | 0.11 | |

| Breast | 1.00 | <0.01 | 1.00 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.30 | |

| Time since diagnosis | (Years) | 1.21 (1.12, 1.30) | <0.01 | 1.10 (0.99, 1.22) | 0.05 | 1.15 (1.07, 1.25) | <0.01 | 1.13 (1.03, 1.24) | <0.01 |

| Health insurance | No | 0.42 (0.25, 0.69) | <0.01 | 0.96 (0.49, 1.88) | 0.90 | 0.67 (0.37, 1.19) | 0.17 | 1.41 (0.84, 2.38) | 0.19 |

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Number of concerns† | (Count) | 1.81 (1.70, 1.93) | <0.01 | 1.42 (1.30, 1.56) | <0.01 | 1.35 (1.26, 1.46) | <0.01 | 1.79 (1.42, 2.26) | <0.01 |

The number of concerns in the model of receipt of care for physical concerns refers to number of physical concerns; in the model of receipt of care for emotional concerns refers to number of emotional concerns; and in the model of receipt of care for practical concerns refers to number of practical concerns.

Greater number of concerns was associated with higher odds of receiving care. Additionally, respondents who were further from time of diagnosis had higher odds of receiving care (Figure 4 shows the predicted probabilities of receiving care for post-treatment concerns by time since diagnosis). Receipt of care was most common for physical concerns and least common for practical concerns.

Figure 4.

Predicted Probabilities of Receiving Care for Post-Treatment Concerns by Time Since Diagnosis.

Compared to respondents with the most education, respondents who had less than a college education had lower odds of receiving care for physical concerns or emotional concerns. Respondents who did not have health insurance had less than half the odds of receiving care for physical concerns, and compared to breast cancer survivors, testicular cancer survivors had lower odds of receiving care for physical concerns while prostate cancer survivors had higher odds. Respondents who did not receive chemotherapy had higher odds of receiving care for physical concerns compared to respondents who received chemotherapy and surgery and/or radiation while respondents who received only chemotherapy had lower odds of receiving care. Finally, age and gender were associated with receiving care for emotional concerns in data from the 2010 LIVESTRONG survey: younger respondents had slightly lower odds of receiving care for emotional concerns and women had higher odds compared to men.

Discussion

The results of this study are a valuable contribution to the growing evidence base supporting post-treatment survivorship as a distinct and often challenging component of the cancer continuum (Richardson, et al., 2011). The most common symptoms reported in these surveys are consistent with what is known from the larger survivorship literature (Farley Short, Bradley, & Yabroff, 2009; Pachman, et al., 2012; Yabroff, Lund, Kepka, & Mariotto, 2011; B.J. Zebrack, 2011): more than half of the 2910 survivors who were included in these analyses reported fatigue (often the most common symptom reported by samples of survivors (e.g., (Barbera, et al., 2010; Becker, Rechis, Kang, & Brown, 2010; Mohile et al., 2011)), cognitive problems, fears of recurrence, problems with grief or identity, emotional distress, problems with body image, and, for those who were in school at their time of diagnosis, concerns about educational goals. The burden of physical, emotional, and practical concerns reported by survey respondents remained consistently high across the 2006 and 2010 surveys, with one exception: employment concerns were more commonly reported among respondents to the 2010 survey.

Because of the large sample size and variety of cancers represented, these results improve our understanding of how sociodemographic and medical variables are associated with risk for post-treatment concerns. As seen in previous research (e.g., (Barbera, et al., 2010; Philip, Merluzzi, Zhang, & Heitzmann, 2012)), women reported a higher concern burden than men, and younger survivors reported more physical, emotional, and employment concerns (Bloom, Petersen, & Kang, 2007; Brant et al., 2011; Foster, Wright, Hill, Hopkinson, & Roffe, 2009; Mao et al., 2007; Meyerowitz, Kurita, & D'Orazio, 2008; Shi, et al., 2011; Smith, Crespi, Petersen, Zimmerman, & Ganz, 2010; B. J. Zebrack, Yi, Petersen, & Ganz, 2008). One exception was that older survivors more frequently indicated debt concerns (see (Rogers, Harvey-Woodworth, Hare, Leong, & Lowe, 2012) for an example of older survivors reporting fewer financial concerns). Older survivors (age 65 and up) are an understudied group, and addressing their post-treatment concerns, including economic concerns that may be more challenging in the context of retirement compared to survivors who are working, is a high priority (Bellury et al., 2011; Parry, Kent, Mariotto, Alfano, & Rowland, 2011). Respondents who received the most treatment (chemotherapy plus surgery and/or radiation) consistently fared worse compared to respondents who received less treatment. Indeed, greater exposure to treatment increases the chances of associated physical morbidity (e.g., (Oerlemans, Mols, Nijziel, Lybeert, & van de Poll-Franse, 2011; Padilla & Ropka, 2005)), emotional challenges (Ganz, Kwan, Stanton, Bower, & Belin, 2011; Rusiewicz, 2008; Smith, et al., 2011; A. L. Stanton, 2006), and practical challenges related to costs of and time needed to receive and recover from treatments (da Silva & dos Santos, 2010; Rogers, et al., 2012). Advances in genomic medicine will provide more specificity in identifying the survivors at greatest risk for adverse post-treatment outcomes (Robison & Demark-Wahnefried, 2011).

Indicators of relative socioeconomic disadvantage – lower annual income, less education, and lack of health insurance – were also associated with a higher burden of post-treatment physical concerns, employment and debt concerns. Cancer significantly increases the probability of incurring out-of-pocket medical expenses, which for survivors past the active treatment phase can still be as high as $5,000 per year (Short, Moran, & Punekar, 2011). Programs that take a public health approach to offering resources to traditionally underserved or disadvantaged survivors (e.g., (Fairley, Pollack, Moore, & Smith, 2009; LIVESTRONG, 2011)) are extremely important to reducing and eliminating disparities in outcomes during the post-treatment period.

Though post-treatment physical, emotional, and debt concerns were consistent across the two survey administrations, the percentage of survivors who reported employment concerns significantly increased between the 2006 (35 percent) and 2010 (43 percent) surveys. These analyses involved a large number of statistical tests and as such, this result should be interpreted with some caution. However, the increase may be related, in part, to the economic crisis that began in 2008. Intensive physical rehabilitation can improve return-to-work rates among post-treatment survivors, but a substantial minority of survivors may be unable to return to work at their pre-diagnosis level of effort (Thijs et al., 2012). More work is needed to help cancer survivors avoid short- and/or long-term work disruption (Feuerstein et al., 2010; Hauglann, et al., 2012).

While the results presented here offer sobering statistics suggesting a high (and in the case of employment concerns, increasing) burden of physical, emotional, and practical concerns for post-treatment cancer survivors, more alarming are the results regarding associated receipt of care. Depending on time since diagnosis, as many as 41 percent of respondents with post-treatment physical concerns did not receive associated care, as many as 62 percent of respondents with emotional concerns did not receive care, and as many as 68 percent of respondents with practical concerns did not receive care. Worse, odds of receiving care for post-treatment emotional concerns decreased over the surveillance period. Again, due to the large number of statistical tests, this could be a spurious finding. Regardless of the decrease in reported care for emotional concerns, the number of survivors in either survey who did not receive care for emotional concerns is troubling in light of the emphasis placed on the importance of addressing emotional concerns among cancer survivors in the Institute of Medicine’s 2008 “Cancer Care for the Whole Patient” report (Institute of Medicine, 2008) as well as in other recent reports (Jacobsen & Wagner, 2012; Jacobsen PB, 2012). Additionally, the probability of having received treatment for individual concerns varied widely. Why treatment was more commonly received for some concerns versus others is likely a function of multiple parameters including the degree to which the concern is life-threatening; the availability of interventions to address the concern; and the individual characteristics of the survivor experiencing the concern and their ability to seek, request, and receive care. Understanding why some concerns are addressed more often than others and how to increase the provision of care for post-treatment concerns in general are important areas of ongoing research.

Of concern were mismatches between characteristics associated with higher burden of concern that were also associated with lower odds of receiving care. For example, younger survivors reported more emotional concerns but had lower odds of receiving post-treatment emotional care (in 2010); survivors who received chemotherapy had more physical concerns but lower odds of receiving physical care (compared to survivors who did not receive chemotherapy); and survivors without health insurance reported more physical concerns but had lower odds of receiving physical care. This observation in particular reinforces the value of expanded health care coverage for people affected by cancer in the Patient Protection and Affordability Act (American Cancer Society, 2012; McCabe, et al., 2013). While receiving care is often a necessary step towards improving health, receiving care requires time and effort on the part of the survivor. Our observation that, in some cases, higher concern burden was associated with lower odds of receiving care may reflect the degree to which concerns can be so overwhelming that survivors don’t have the capacity to seek care that could potentially ameliorate the concern. For younger survivors, who are more likely to be employed full-time and caring for children, and for survivors who received chemotherapy, who may have more long-term sequelae due to their more intensive treatment, this may be especially true.

Without a doubt, much work remains to improve survivors’ access to post-treatment care for physical, emotional, and practical concerns (Treanor & Donnelly, 2012). The delivery of post-treatment survivorship care is an active, complex, and growing area of research and practice (Campbell, et al., 2011; Earle & Ganz, 2012; Howell, et al., 2012; Shapiro, et al., 2009). LIVESTRONG recently led an effort to arrive at consensus among a large and diverse group of cancer stakeholders on “essential elements” of post-treatment care (R. Rechis, Beckjord, E., Arvey, S., Reynolds, K.A., Goldrick, D., 2012). There was broad agreement that survivorship care must provide referral or direct access to treatment summaries and Survivorship Care Plans (SCP), surveillance, care coordination, health promotion education, and symptom management.

SCPs are intended to be a tool to prevent failures in care coordination, with some evidence that they are effective in doing so (e.g., PCPs working with a SCP provide equally successful follow-up care as cancer care providers (Grunfeld & Earle, 2010b)). However, SCPs are not yet standard practice in survivorship care (Phillips, 2012; Stricker et al., 2011). The time and effort required to prepare and deliver SCPs are substantial (Stricker, et al., 2011) with additional challenges related to reimbursement and provider workload (Earle & Ganz, 2012). New patient-centered care accreditation standards set by organizations such as the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (American College of Surgeons) may, however, facilitate the creation, delivery, and coordination surrounding SCPs. Additionally, use of electronic medical records (EMRs) is increasing (Jamoom E, 2012). EMRs may additionally reduce the burden associated with the provision of SCPs by making key data available to auto-populate components of SCPs (Hesse, Hanna, Massett, & Hesse, 2010). The IOM Lost in Transition report laid critical groundwork for increasing the provision of quality post-treatment survivorship care. The work that continues within the health care system to implement the provision of post-treatment care may lead to fewer post-treatment survivors reporting to not receive care for their post-treatment concerns. However, educating survivors about the availability of post-treatment care and legitimizing their post-treatment concerns as important and worthy of intervention may also be required before post-treatment care is more routine and delivered more frequently.

Limitations

Several limitations are worth noting. The data collected in the LIVESTRONG samples reflect a volunteer sample. As such, the 2910 survivors in this study cannot be taken as representative of the population of all post-treatment survivors. Additionally, our use of the word “concern” to describe the physical, emotional, and practical issues endorsed by survey respondents assumes that the reported issues were problematic for the survivor, which may or may not have been the case. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the concerns reported by survey respondents here were congruent with those reported in many other studies where the concerns were associated with decreased quality of life. A strength of the study is its focus on symptom concerns among a large and varied survivor group in the post-treatment period (Jacobsen & Jim, 2011). It is also important to note that the post-treatment concerns reported in this sample may be conservative due to the degree to which the LIVESTRONG survey respondents are not representative of the broader population of cancer survivors. Nearly 30 percent of respondents had annual incomes at or above $100K per year, over half had a college education, and less than 5 percent were without health insurance. Still, our results suggest that lower annual income, less education, and worse access to health insurance are associated with more post-treatment physical concerns and practical concerns, as well as lower odds of receiving post-treatment.

Clinical Implications of the Study

Earle and Ganz recently charged the survivorship research and practice community to not let the “perfect be the enemy of the good” when it comes to implementing and delivering post-treatment survivorship care (Earle & Ganz, 2012). While we don’t yet have a robust evidence base to underlie best practices for promoting health and wellness among cancer survivors, and have not achieved all that was envisioned in the Lost in Transition report (Institute of Medicine, 2005), we must move forward with broader dissemination of post-treatment survivorship care (Pollack, Hawkins, Peaker, Buchanan, & Risendal, 2011). Survivors themselves make this clear. One respondent to the 2010 LIVESTRONG Survey commented: “I was successfully treated for cancer but I have had problem after problem from side effects ever since … I am emotionally worn out and feel wounded to the core of my being.” The data presented here, which add to a growing literature on common challenges encountered in the post-treatment period, suggest that too often, what we are doing now is not sufficient. Progress in adopting the LIVESTRONG Essential Elements of Survivorship Care and the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations for achieving high-quality cancer care (McCabe, et al., 2013) will be critical to adequately supporting all cancer survivors in their efforts to live well in the post-treatment period.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by funding from LIVESTRONG and the University of Pittsburgh Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Scholars Program (CTSA KL2, Grant Number 8KL2TR000146-07).

Contributor Information

Ellen Burke Beckjord, University of Pittsburgh.

Kerry A. Reynolds, RAND Corporation.

GJ van Londen, University of Pittsburgh.

Rachel Burns, RAND Corporation.

Reema Singh, RAND Corporation.

Sarah R. Arvey, Research and Evaluation, LIVESTRONG.

Stephanie A. Nutt, Research and Evaluation, LIVESTRONG.

Ruth Rechis, Research and Evaluation, LIVESTRONG.

References

- Ahles Tim A, Root James C, Ryan Elizabeth L. Cancer- and Cancer Treatment–Associated Cognitive Change: An Update on the State of the Science. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(30):3675–3686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. [Retrieved 17 January 2012];Six Ways the Affordable Care Act is Helping Cancer Patients. 2012 from http://www.cancer.org/myacs/eastern/areahighlights/affordable-care-act-six-ways. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Surgeons. [Retrieved March, 2012];Cancer Program Standards 2012, Version 1.1: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. ( http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.html) [Google Scholar]

- Andrykowski MA, Lykins E, Floyd A. Psychological health in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avis Nancy E, Smith Kevin W, McGraw Sarah, Smith Roselyn G, Petronis Vida M, Carver Charles S. Assessing Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors (QLACS) Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation. 2005;14(4):1007–1023. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-2147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbera L, Seow H, Howell D, Sutradhar R, Earle C, Liu Y, Dudgeon D. Symptom burden and performance status in a population-based cohort of ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5767–5776. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker H, Rechis R, Kang SJ, Brown A. The post-treatment experience of cancer survivors with pre-existing cardiopulmonary disease. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2010:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0957-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellury LM, Ellington L, Beck SL, Stein K, Pett M, Clark J. Elderly cancer survivorship: an integrative review and conceptual framework. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(3):233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JR, Petersen DM, Kang SH. Multi-dimensional quality of life among long-term (5+ years) adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2007;16(8):691–706. doi: 10.1002/pon.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brant JM, Beck S, Dudley WN, Cobb P, Pepper G, Miaskowski C. Symptom trajectories in posttreatment cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34(1):67–77. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f04ae9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Tessaro I, Gellin M, Valle CG, Golden S, Kaye L, Miller K. Adult cancer survivorship care: experiences from the LIVESTRONG centers of excellence network. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(3):271–282. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0180-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S. Chronic pain syndromes in cancer survivors. Nurs Stand. 2011;25(21):35–41. doi: 10.7748/ns2011.01.25.21.35.c8288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva G, dos Santos MA. Stressors in breast cancer post-treatment: a qualitative approach. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2010;18(4):688–695. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692010000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle Craig C, Ganz Patricia A. Cancer Survivorship Care: Don't Let the Perfect Be the Enemy of the Good. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(30):3764–3768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, Bruinooge S, Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists : challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3(2):79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairley TL, Pollack LA, Moore AR, Smith JL. Addressing cancer survivorship through public health: an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18(10):1525–1531. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley Short P, Bradley CJ, Yabroff KR. Employment status among cancer survivors. JAMA. 2009;302(1):33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.904. author reply 34–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein M, Todd BL, Moskowitz MC, Bruns GL, Stoler MR, Nassif T, Yu X. Work in cancer survivors: a model for practice and research. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2010:1–23. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Leach CR, Ganz PA, Stefanek ME, Rowland JH. Who Provides Psychosocial Follow-Up Care for Post-Treatment Cancer Survivors? A Survey of Medical Oncologists and Primary Care Physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster C, Wright D, Hill H, Hopkinson J, Roffe L. Psychosocial implications of living 5 years or more following a cancer diagnosis: a systematic review of the research evidence. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2009;18(3):223–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Bower JE, Belin TR. Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(9):1101–1109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W, Bennett MI, Stark D, Murray S, Higginson IJ. Psychological distress in cancer from survivorship to end of life care: prevalence, associated factors and clinical implications. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(11):2036–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld E, Earle CC. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: treatment through survivorship. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010a;2010(40):25–30. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld E, Earle CC. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: treatment through survivorship. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 2010b;2010(40):25–30. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M. It's not over when it's over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors--a systematic review. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2010;40(2):163–181. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.2.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauglann B, Benth JS, Fossa SD, Dahl AA. A cohort study of permanently reduced work ability in breast cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):345–356. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse BW, Hanna C, Massett HA, Hesse NK. Outside the box: will information technology be a viable intervention to improve the quality of cancer care? J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010(40):81–89. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse BW, Moser RP, Rutten LJ, Kreps GL. The health information national trends survey: research from the baseline. J Health Commun. 2006;11(Suppl 1):vii–xvi. doi: 10.1080/10810730600692553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell D, Hack TF, Oliver TK, Chulak T, Mayo S, Aubin M, Sinclair S. Models of care for post-treatment follow-up of adult cancer survivors: a systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Surviv. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0232-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson MM, Landier W, Ganz PA. Impact of survivorship-based research on defining clinical care guidelines. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(10):2085–2092. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humpel N, Iverson DC. Sleep quality, fatigue and physical activity following a cancer diagnosis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19(6):761–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Page AEK, editors. Institute of Medicine. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen Paul B, Jim Heather SL. Consideration of Quality of Life in Cancer Survivorship Research. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20(10):2035–2041. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen Paul B, Wagner Lynne I. A New Quality Standard: The Integration of Psychosocial Care Into Routine Cancer Care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(11):1154–1159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PB, Holland JC, Steensma DP. Caring for the Whole Patient: The Science of Psychosocial Care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1151–1153. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamoom E, Beatty P, Bercovitz A, Woodwell D, Palso K, Rechtsteiner E. Physician adoption of electronic health record systems: United States, 2011. NCHS data brief, no 98. 2012 Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff AC, Kuhlthau K, Pajolek H, Leisenring W, Armstrong GT, Robison LL, Park ER. Employer-sponsored health insurance coverage limitations: results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Support Care Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1523-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIVESTRONG. Navigating the Cancer Experience with the Help of the Lance Armstrong Foundation. Austin, TX: LIVESTRONG; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mao JJ, Armstrong K, Bowman MA, Xie SX, Kadakia R, Farrar JT. Symptom burden among cancer survivors: impact of age and comorbidity. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(5):434–443. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.05.060225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, Reaman GH, Tyne C, Wollins DS, Hudson MM. American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: Achieving High-Quality Cancer Survivorship Care. J Clin Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehnert A, Koch U. Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(4):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses K, Azuero A, Hassey L, McNees P, Pisu M. Does economic burden influence quality of life in breast cancer survivors? Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz BE, Kurita K, D'Orazio LM. The psychological and emotional fallout of cancer and its treatment. Cancer J. 2008;14(6):410–413. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedema B, Easley J. Barriers to rehabilitative care for young breast cancer survivors: a qualitative understanding. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(6):1193–1201. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohile SG, Heckler C, Fan L, Mustian K, Jean-Pierre P, Usuki K, Morrow G. Age-related Differences in Symptoms and Their Interference with Quality of Life in 903 Cancer Patients Undergoing Radiation Therapy. J Geriatr Oncol. 2011;2(4):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moryl N, Coyle N, Essandoh S, Glare P. Chronic pain management in cancer survivors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(9):1104–1110. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oerlemans S, Mols F, Nijziel MR, Lybeert M, van de Poll-Franse LV. The impact of treatment, socio-demographic and clinical characteristics on health-related quality of life among Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma survivors: a systematic review. Ann Hematol. 2011;90(9):993–1004. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1274-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachman Deirdre R, Barton Debra L, Swetz Keith M, Loprinzi Charles L. Troublesome Symptoms in Cancer Survivors: Fatigue, Insomnia, Neuropathy, and Pain. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(30):3687–3696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla G, Ropka ME. Quality of life and chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28(3):167–171. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200505000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry Carla, Kent Erin E, Mariotto Angela B, Alfano Catherine M, Rowland Julia H. Cancer Survivors: A Booming Population. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20(10):1996–2005. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip EJ, Merluzzi TV, Zhang Z, Heitzmann CA. Depression and cancer survivorship: importance of coping self-efficacy in post-treatment survivors. Psychooncology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/pon.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips C. A Closer Look: A Tough Transition: Cancer Survivorship Plans Slow to Take Hold. NCI Cancer Bulletin. 2012;9(13) Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack Lori A, Hawkins Nikki A, Peaker Brandy L, Buchanan Natasha, Risendal Betsy C. Dissemination and Translation: A Frontier for Cancer Survivorship Research. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20(10):2093–2098. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, Klabunde CN, Smith T, Aziz N, Stefanek M. Differences between primary care physicians' and oncologists' knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1403–1410. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechis R, Boerner L, Nutt S, Shaw K, Berno D, Duchover Y. How Cancer has Affected Post-Treatment Survivors: A LIVESTRONG Report. Austin, TX: LIVESTRONG; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rechis R. How cancer has affected post treatment survivors: A LIVESTRONG REPORT. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.livestrong.org/pdfs/3-0/LSSurvivorSurveyReport. [Google Scholar]

- Rechis R, Beckjord E, Arvey S, Reynolds KA, Goldrick D. The Essential Elements of Survivorship Care: A LIVESTRONG Brief Report. Austin, TX: LIVESTRONG; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rechis R, Reynolds KA, Beckjord EB, Nutt S, Burns RM, Schaefer JS. "I Learned to Live with It" is Not Enough: Challenges Reported by Post-Treatment Cancer Survivors in the LIVESTRONG Surveys. Austin, TX: LIVESTRONG; 2011a. [Google Scholar]

- Rechis R, Reynolds KA, Beckjord EB, Nutt S, Burns RM, Schaefer JS. "I Learned to Live With It" Is Not Good Enough: Challenges Reported by Post-Treatment Cancer Survivors in the LIVESTRONG Surveys. Austin, TX: LIVESTRONG; 2011b. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Addington-Hall J, Amir Z, Foster C, Stark D, Armes J, Sharpe M. Knowledge, ignorance and priorities for research in key areas of cancer survivorship: findings from a scoping review. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(Suppl 1):S82–S94. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison Leslie L, Demark-Wahnefried Wendy. Cancer Survivorship: Focusing on Future Research Opportunities. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20(10):1994–1995. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SN, Harvey-Woodworth CN, Hare J, Leong P, Lowe D. Patients' perception of the financial impact of head and neck cancer and the relationship to health related quality of life. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50(5):410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland JH, Hewitt M, Ganz PA. Cancer survivorship: a new challenge in delivering quality cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5101–5104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusiewicz A, DuHamel KN, Burkhalter J, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Scigliano E, Papadopoulos E, Moskowitz C, Redd W. Psychological distress in long-term survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17:329–337. doi: 10.1002/pon.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt ME, Chang-Claude J, Vrieling A, Heinz J, Flesch-Janys D, Steindorf K. Fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: temporal courses and long-term pattern. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(1):11–19. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro CL, McCabe MS, Syrjala KL, Friedman D, Jacobs LA, Ganz PA, Marcus AC. The LIVESTRONG Survivorship Center of Excellence Network. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3(1):4–11. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0076-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Smith TG, Michonski JD, Stein KD, Kaw C, Cleeland CS. Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: a report from the American Cancer Society's Studies of Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2011;117(12):2779–2790. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short PF, Moran JR, Punekar R. Medical expenditures of adult cancer survivors aged <65 years in the United States. Cancer. 2011;117(12):2791–2800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Desantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, Ward E. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver JK. Strategies to overcome cancer survivorship care barriers. PM R. 2011;3(6):503–506. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SK, Crespi CM, Petersen L, Zimmerman S, Ganz PA. The impact of cancer and quality of life for post-treatment non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Psychooncology. 2010 doi: 10.1002/pon.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SK, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Benecha H, Abernethy AP, Mayer DK, Ganz PA. Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Long-Term Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Survivors: Does Time Heal? J Clin Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL. Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5132–5137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL. What Happens Now? Psychosocial Care for Cancer Survivors After Medical Treatment Completion. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(11):1215–1220. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stricker CT, Jacobs LA, Risendal B, Jones A, Panzer S, Ganz PA, Palmer SC. Survivorship care planning after the Institute of Medicine recommendations: how are we faring? J Cancer Surviv. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taskila T, Martikainen R, Hietanen P, Lindbohm ML. Comparative study of work ability between cancer survivors and their referents. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43(5):914–920. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thewes B, Butow P, Zachariae R, Christensen S, Simard S, Gotay C. Fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic literature review of self-report measures. Psychooncology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pon.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thijs KM, de Boer AG, Vreugdenhil G, van de Wouw AJ, Houterman S, Schep G. Rehabilitation using high-intensity physical training and long-term return-to-work in cancer survivors. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(2):220–229. doi: 10.1007/s10926-011-9341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treanor C, Donnelly M. An international review of the patterns and determinants of health service utilisation by adult cancer survivors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:316. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D, Mariotto A. Economic burden of cancer in the United States: estimates, projections, and future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(10):2006–2014. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack BJ, Yi J, Petersen L, Ganz PA. The impact of cancer and quality of life for long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2008;17(9):891–900. doi: 10.1002/pon.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack BJ. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(S10):2289–2294. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]