Abstract

Background and Purpose

Hydroxamate derivatives have attracted considerable attention because of their broad pharmacological properties. Recent studies reported their potential use in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases, arthritis and infectious diseases. However, the mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory effects of hydroxamate derivatives remain to be elucidated. In an effort to develop a novel pharmacological agent that could suppress abnormally activated macrophages, we investigated a novel aliphatic hydroxamate derivative, WMJ-S-001, and explored its anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

Experimental Approach

RAW264.7 macrophages were exposed to LPS in the absence or presence of WMJ-S-001. COX-2 expression and signalling molecules activated by LPS were assessed.

Key Results

LPS-induced COX-2 expression was suppressed by WMJ-S-001. WMJ-S-001 inhibited p38MAPK, NF-κB subunit p65 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP)β phosphorylation in cells exposed to LPS. Treatment of cells with a p38MAPK inhibitor (p38MAPK inhibitor III) markedly inhibited LPS-induced p65 and C/EBPβ phosphorylation and COX-2 expression. LPS-increased p65 and C/EBPβ binding to the COX-2 promoter region was suppressed in the presence of WMJ-S-001. In addition, WMJ-S-001 suppression of p38MAPK, p65 and C/EBPβ phosphorylation, and subsequent COX-2 expression were restored in cells transfected with a dominant-negative (DN) mutant of MAPK phosphatase-1 (MKP-1). WMJ-S-001 also caused an increase in MKP-1 activity in RAW264.7 macrophages.

Conclusions and Implications

WMJ-S-001 may activate MKP-1, which then dephosphorylates p38MAPK, resulting in a decrease in p65 and C/EBPβ binding to the COX-2 promoter region and COX-2 down-regulation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. The present study suggests that WMJ-S-001 may be a potential drug candidate for alleviating LPS-associated inflammatory diseases.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | ||

|---|---|---|

| COX-2 | GSK3β | JNK |

| ERK1 | HDAC | p38MAPK |

| ERK2 | Inducible (i) NOS | RSK (ribosomal protein S6 kinase) |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| JNK inhibitor II |

| LPS |

| PGE2 |

| U0126 |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

Macrophages are the primary immune cells in host defence against invading pathogens and play a central role in innate immune responses. However, aberrantly activated macrophages that produce excessive amounts of inflammatory mediators have been implicated in various inflammatory disorders including atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and sepsis (Sweet and Hume, 1996; Medvedev et al., 2000). Sepsis and subsequent multiple organ dysfunction remain a leading cause of death among severely ill patients (Hotchkiss and Karl, 2003). The most common cause of sepsis is elicited by LPS, the major component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria (Beutler and Rietschel, 2003). LPS causes the excessive release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as PGs and ILs, which ultimately cause clinical symptoms (Gioannini and Weiss, 2007; Wang et al., 2011). PGs, lipid autacoids derived from arachidonic acid, play critical roles in homeostatic and inflammatory processes throughout the body (Ricciotti and FitzGerald, 2011). COX-2, a key enzyme that catalyses the biosynthesis of PGs, is induced primarily by inflammation. There is growing evidence indicating that COX-2 expression is linked to diseases associated with inflammation, suggesting it has a major role in inflammation (Williams et al., 1999; Ejima et al., 2003). Therefore, suppression of aberrant macrophage activation and COX-2 expression may have valuable therapeutic potential in treating inflammatory disorders.

The transcription factor NF-κB plays an important role in regulating pro-inflammatory gene expression and aberrant activation of NF-κB contributes to the pathogenesis of immune and inflammatory disorders and cancer (Liu and Malik, 2006). NF-κB activation in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli transactivates a number of pro-inflammatory mediators including inducible (i) NOS and COX-2 (Wu et al., 2003; Shishodia et al., 2004). The COX-2 promoter region contains many transcription factor-binding sites. In addition to NF-κB, the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) also plays an important regulatory role in COX-2 expression (Glauben et al., 2006; Chuang et al., 2014).

Cellular responses to inflammatory stimuli are mainly mediated by the activation of MAPK cascades (Chang and Karin, 2001; Dong et al., 2002). MAPKs such as p38MAPK and JNK subfamilies are well-recognized as regulator of the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, ILs, iNOS and COX-2 (Hsu et al., 2010; 2011,; Turpeinen et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2011). The sequential protein phosphorylation and activation of MAPKKK, MAPKK and MAPK is required for MAPKs activation (Raman et al., 2007). In contrast, negative regulation of MAPKs is mediated primarily by MAPK phosphatases (MKPs), which dephosphorylate and thereby inactivate MAPKs (Farooq and Zhou, 2004; Lang et al., 2006; Jeffrey et al., 2007). MKP-1, the founding member of the MKP family, plays a pivotal role in modulating innate immune responses (Abraham et al., 2006; Chi et al., 2006; Dickinson and Keyse, 2006). MKP-1-null cells exhibit prolonged p38MAPK activation and elevated inflammatory cytokine secretion (Zhao et al., 2006). In addition, LPS-induced inflammation in Mkp-1−/− mice is accompanied by an exacerbated production of inflammatory cytokines and increased mortality (Frazier et al., 2009). As MKP-1 is an essential and negative regulator of inflammatory responses (Jeffrey et al., 2007; Roth et al., 2009), pharmacological approaches that modulate MKP-1 might be potential therapeutic targets for pathogen-associated inflammatory diseases.

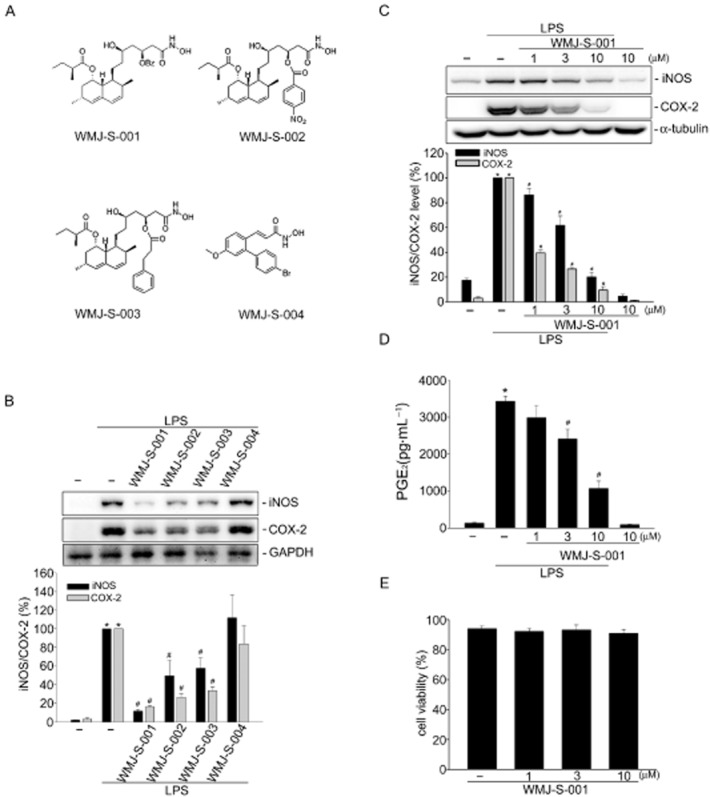

Recent development in drug discovery has highlighted the diverse biological and pharmacological properties of hydroxamate, a key pharmacophore (Bertrand et al., 2013). A variety of hydroxamate derivatives have demonstrated potential as anti-inflammatory (Hsu et al., 2011), anti-infectious (Rodrigues et al., 2014) and anti-tumour (Jiang et al., 2012; Venugopal et al., 2013) agents. As hydroxamate and its derivatives may possess functions leading to therapeutic applications, they are worthy of further development. The anti-tumour properties of hydroxamate derivatives have been studied extensively and some hydroxamates, such as suberoylanilide hydroxamate (vorinostat, SAHA), have been approved for clinical use for treating cancer (Grant et al., 2007). In contrast, the underlying anti-inflammatory mechanisms of hydroxamates have still not been elucidated. We thus synthesized a series of aliphatic hydroxamate derivatives and evaluated their anti-inflammatory properties in RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to LPS. WMJ-S-001 (Figure 1A) was selected from these compounds, as it potently inhibited the expression of iNOS and COX-2 in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. We demonstrated in this study that WMJ-S-001, an aliphatic hydroxamate derivative, may activate MKP-1 to dephosphorylate and inactivate p38MAPK, leading to a decrease in p65 and C/EBPβ binding to the COX-2 promoter region, which culminates in suppressing COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages.

Figure 1.

WMJ-S-001 suppressed COX-2 and iNOS expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. (A) Chemical structures of WMJ-S-001, WMJ-S-002, WMJ-S-003 and WMJ-S-004. (B) Cells were pretreated with 10 μM of WMJ-S-001, WMJ-S-002, WMJ-S-003 or WMJ-S-004 for 30 min followed by the stimulation with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. After treatment, cells were harvested to assess the COX-2 and iNOS levels by immunoblotting. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of at least four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. (C) Cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 at the indicated concentrations for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. The COX-2 and iNOS levels were then determined by immunoblotting. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of six independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. (D) Cells were transfected as described in (C); media were then collected to measure PGE2 as described in the ‘Methods’ section. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. (E) Cells were treated with WMJ-S-001 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h, cell viability was determined using a trypan blue dye exclusion test. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments.

Methods

Synthesis of WMJ-S

WMJ-S compounds were synthesized as described in the Supporting Information.

Cell culture

The RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage cell line was purchased from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center (Hsinchu, Taiwan), and cells were maintained in DMEM (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% FBS, 100 U·mL−1 of penicillin G, and 100 μg·mL−1 streptomycin in a humidified 37°C incubator.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously (Huang et al., 2013). Briefly, cells were lysed in an extraction buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 7.0), 140 mM NaCl, 2 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride, 5 mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40, 0.05 mM pepstatin A and 0.2 mM leupeptin. Samples of equal amounts of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto an nitrocellulose membrane, which was then incubated in a tris-buffered saline and tween 20 buffer containing 5% non-fat milk. Proteins were visualized by incubating with specific primary antibodies for 2 h followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for another 1 h. Immunoreactivity was detected based on enhanced chemiluminescence as per the instructions of the manufacturer. Quantitative data were obtained using a computing densitometer with a scientific imaging system (Biospectrum AC System, UVP, Upland, CA, USA).

Reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR analyses were performed as described previously (Huang et al., 2014). Primers used for amplification of the COX-2 and GAPDH fragments were as follows: COX-2, sense 5′-CCCCCACAGTCAAAGACACT-3′ and antisense 5′-CTCATCACCCCACTCAGGAT-3′; and GAPDH, sense 5′-CCTTCATTGACCTCAACTAC-3′ and antisense 5′-GGAAGGCCATGCCAGTGAGC-3′. GAPDH was used as the internal control. The PCR was performed with the following conditions: a 5 min denaturation step at 94°C, 30 cycles of a 30 s denaturation step at 94°C, a 30 s annealing step at 56°C, and a 45 s extension step at 72°C to amplify COX-2 and GAPDH cDNA. The amplified fragment sizes for COX-2 and GAPDH were 191 and 594 bp respectively. PCR products were run on an agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized by UV illumination.

Measurements of PGE2 production

After treatment as indicated, PGE2 in the medium was assayed using a PGE2 enzyme immunoassay kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Butler Pike, PA, USA), according to procedures described by the manufacturer.

Cell viability assay (trypan blue dye exclusion assay)

RAW264.7 macrophages (104 cells per well) were treated with vehicle or WMJ-S-001 for 24 h. Cells were harvested and re-suspended in PBS. Cells in a volume of 150 μL were mixed with 0.4% trypan blue solution (150 μL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). From this, 10 μL was charged into the haemocytometer chamber and examined immediately. Live cells excluded the dye whereas the dye entered and stained the dead cells blue in colour. Both stained and unstained cells were counted, and cell viability was calculated using the formula: cell viability (%) = a/(a + b) × 100, where a is total cells unstained and b is total cells stained.

Transfection in RAW264.7 macrophages

RAW264.7 macrophages were transfected with different constructs as described below using Turbofect reagent (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the reporter assay, cells were transfected with COX-2-luc, NF-κB-Luc, C/EBP-luc, m NF-κB-COX-2-luc, or mC/EBP-COX-2-luc plus Renilla-luc. For immunoblotting, cells were transfected with pcDNA, or MKP-1-DN.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

Cells with and without treatments were then harvested, and the luciferase activity was determined using a Dual-Glo luciferase assay system kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Normalization was performed with renilla luciferase activity as the basis.

Immunofluorescence analysis

For determination of NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation, RAW264.7 macrophages were seeded on glass cover slips for 24 h. Cells were pretreated with WMJ-S-001 for 30 min and stimulated with LPS for another 1 h. After treatment, cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed in 4% (v·v−1) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized for 5 min in 0.1% (v·v−1) Triton X-100, and incubated with 5% (v·v−1) skimmed milk in PBS for 30 min before being stained. To observe NF-κB translocation, cells were reacted with rabbit anti-mouse NF-κB p65 antibody (1:50 dilution in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. After being washed, slides were incubated for 1 h with FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and propidium iodide (10 μg·mL−1), and then observed under a confocal microscope (Zeiss, LSM 410). Green fluorescence indicated NF-κB p65, and red fluorescence represented nuclei. NF-κB translocation occurred in the cells in which green and red overlapped.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

A ChIP assay was performed as described previously (Huang et al., 2013). Ten per cent of the total purified DNA was used for the PCR in 50 μL reaction mixture. The 163 and 173 bp COX-2 promoter fragments between −466 and −395 (for p65 binding sequence), and −138 and −85 (for C/EBPβ binding sequence) were amplified using the primer pairs, for p65 binding sequence, sense: 5′-GTAGCTGTGTGCGTGCTCTG-3′ and antisense: 5′-CTCCGGTTTCCTCCCAGT-3′; for C/EBPβ binding sequence, sense: 5′-AGCTCTCTTGGCACCACC t-3′ and antisense: 5′-ACGTAGTGGTGACTCTGTCTTTCCGC-3′, in 30 cycles of PCR. This was done: at 95°C for 30 s, at 56°C for 30 s, and at 72°C for 45 s. The PCR products were analysed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Suppression of MKP-1 expression

For MKP-1 suppression, predesigned small interfering (si)RNA targeting the mouse MKP-1 gene were purchased from Sigma. The siRNA oligonucleotides targeting the coding regions of mouse MKP-1 messenger (m)RNA were as follows: MKP-1 siRNA, 5′-cugguucaacgaggcuauu-3′; a negative control siRNA comprising a 19 bp scrambled sequence with 3′dT overhangs was also purchased from Sigma.

MKP-1 activity assay

A serine/threonine phosphatase assay system (Promega) was used to measure MKP-1 activity according to the manufacturer's instructions with modifications. Briefly, cells were lysed in an extraction buffer. Equal amounts of cell homogenates were treated with WMJ-S-001 (1–30 μM) for 20 min. The reaction mixture were then incubated for 2 h at 4°C with 2 μg anti-MKP-1 antibody (Millipore), and 20 μL protein A-Magnetic Beads (Millipore), to immunoprecipitate MKP-1. Immune complexes were then collected, washed three times, and incubated with phosphoprotein, the substrate (amino acid sequence RRApTVA, 100 μM), in protein phosphatase assay buffer (20 mM 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (pH 7.5), 60 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.1 mg mL−1 serum albumin). Reactions were initiated by the addition of the phosphoprotein substrate and carried out for 10 min at 30°C. We also prepared appropriate phosphate standard solutions containing free phosphate for construction of a standard curve. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 50 μL of the Molybdate Dye solution. The absorbance at 630 nm was measured on a microplate reader. Nonspecific hydrolysis of RRApTVA by lysates was assessed in normal IgG immunoprecipitates.

Animal model of endotoxaemia

To evaluate the effect of WMJ-S-001 on survival rate in endotoxaemic mice, an animal model of endotoxaemia was constructed as described previously (Tsoyi et al., 2011). BALB/c mice, 7–8 weeks-old, were obtained from BioLasco (Taipei, Taiwan) and injected with LPS (15 mg·kg−1, i.p.) to induce endotoxaemia. The total number of mice used was 18. After injection of LPS for 12 h, animals were randomized into the vehicle-treated control group and the treatment group, which received WMJ-S-001 20 mg·kg−1. The treatment was administered i.p. and repeated 24 h after induction of endotoxaemia. Animals were monitored up to 10 days to evaluate survival rate after LPS challenge in the absence or presence of WMJ-S-001. Mice were maintained in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication 85-23, revised 1996). All protocols were approved by the Taipei Medical University Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. One-way anova followed by, when appropriate, the Newman–Keuls test was used to determine the statistical significance of the difference between means. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reagents

LPS purified by phenol extraction from Escherichia coli 0127:B8 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). U0126, p38 MAPK Inhibitor III, JNK Inhibitor II, antibodies specific for MKP-1 and COX-2 and Turbofect™ in vitro transfection reagent were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). DMEM, optiMEM, FBS, penicillin and streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Antibodies specific for C/EBPβ and p65 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies specific for α-tubulin, p-p65 Ser536, JNK, p38MAPK, myc tag, and anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG-conjugated HRP antibodies were purchased from GeneTex, Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA). Antibodies specific for ERK1/2, p-ERK1/2, p-JNK1/2 and p-p38MAPK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Murine COX-2 promoter with wild-type construct (−966/+23) cloned into pGL3-basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) were kindly provided by Dr Byron Wingerd (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA). The catalytically inactive murine MKP1-C258S [MKP1 dominant-negative mutant (DN) ] were kindly provided by Dr Nicholas Tonks (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA). NF-κB-Luc, Renilla-luc and Dual-Glo luciferase assay system were purchased from Promega. The C/EBP-luc reporter construct was kindly provided by Dr Kjetil Tasken (University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway). All materials for immunoblotting were purchased from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, UK). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Results

WMJ-S-001 inhibits LPS-induced COX-2 expression

To assess the anti-inflammatory activities of aliphatic hydroxamate derivatives, WMJ-S compounds, we evaluated four WMJ-S compounds (Figure 1A) on LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages at the concentration of 10 μM. As shown in Figure 1B, WMJ-S-001, -002 and -003 significantly decreased LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression while WMJ-S004 was without effects. As WMJ-S-001 exhibited the most marked inhibitory effect, we further investigated the inhibitory mechanisms of WMJ-S-001. We examined iNOS and COX-2 levels in RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to various concentrations of WMJ-S-001 in the presence of LPS. As shown in Figure 1C, WMJ-S-001 inhibited LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expressions in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, treatment of cells with LPS significantly induced PGE2 formation and COX-2-catalysed PGE2 formation was concentration-dependently inhibited by WMJ-S-001 in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages (Figure 1D). We also used a trypan blue dye exclusion test to determine whether the cytotoxic effect was attributable to WMJ-S-001's inhibitory actions on LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. As shown in Figure 1E, cell viability was not altered after WMJ-S-001 (1–10 μM) treatment for 24 h compared with the vehicle-treated control group. Taken together, these findings suggest that WMJ-S-001 may inhibit LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expressions in RAW264.7 macrophages. Moreover, WMJ-S-001 at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 μM inhibited LPS-induced COX-2 expression by 60–80% and the IC50 of WMJ-S-001 was approximately 0.3 μM (Supporting Information Fig. S1). WMJ-S-001 at the higher concentration (10 μM) did not alter cell viability in RAW264.7 macrophages. We thus used WMJ-S-001 at concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 μM to do the following experiments.

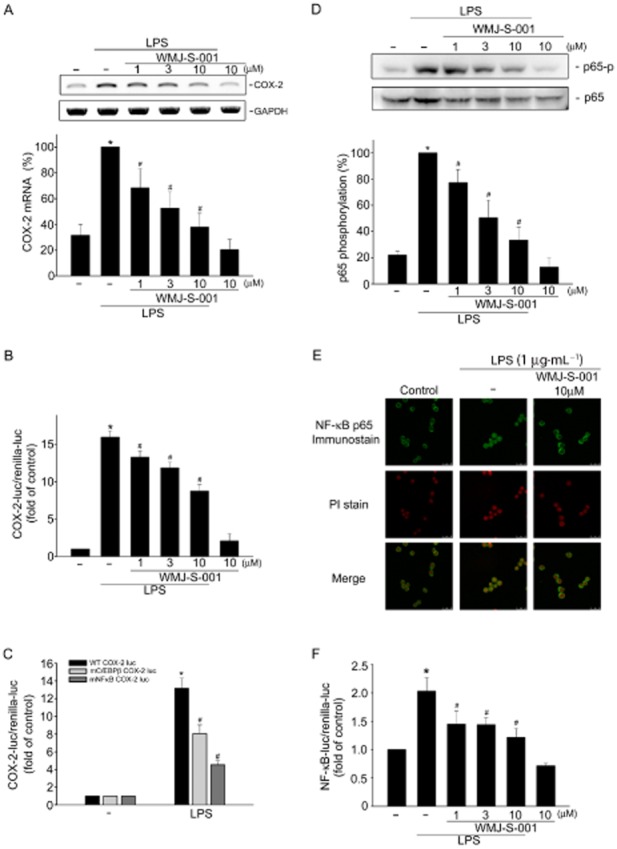

WMJ-S-001 suppressed NF-κB and C/EBPβ activation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages

The RT-PCR analysis was used to confirm the hypothesis that WMJ-S-001 inhibition of COX-2 expression was attributable to a decrease in cox-2 mRNA. As shown in Figure 2A, LPS significantly induced an increase in cox-2 mRNA and WMJ-S-001 concentration-dependently reduced this effect of LPS. Treatment of cells with WMJ-S-001 significantly reduced the LPS-induced increase in COX-2 promoter luciferase activity as determined by the reporter assay (Figure 2B). These results suggest that WMJ-S-001 inhibition of LPS-induced COX-2 expression may have resulted from transcriptional down-regulation of cox-2. It is thus conceivable that WMJ-S-001 may suppress the activation of transcription factors that leads to COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. Many consensus sequences, including those for NF-κB and C/EBPβ in the 5′ flanking region of the cox-2 gene, have been reported to up-regulate COX-2 expression in response to various stimuli (Hsu et al., 2011; Chuang et al., 2014). To confirm the regulatory role of NF-κB and C/EBPβ in COX-2 transcription in RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to LPS, the wild-type murine COX-2 reporter construct (−966/−23, WT COX-2-luc) and mutant reporter constructs with either a NF-κB (−402/−395, mNF-κB COX-2-luc) or a C/EBPβ (−138/−130, m C/EBPβ COX-2-luc) site deletion were separately transfected into RAW264.7 cells. As shown in Figure 2C, LPS caused an increase in COX-2 promoter luciferase activity in cells transfected with the wild-type murine COX-2 construct. However, LPS-induced COX-2 promoter luciferase activity was reduced in cells transfected with the mutant constructs with NF-κB or C/EBPβ deletion. These results suggest that the activation of NF-κB or C/EBPβ is necessary for LPS-induced COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages. We next investigated whether WMJ-S-001 affects NF-κB and C/EBPβ activation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. As shown in Figure 2D, WMJ-S-001 significantly inhibited LPS-induced NF-κB subunit p65 phosphorylation. NF-κB/p65 phosphorylation may account for its nuclear localization and transcriptional activity (Li and Verma, 2002). Therefore, we examined whether WMJ-S-001 interferes with the subcellular localization of NF-κB. p65 exhibited a decreased cytoplasmic localization and increased nuclear localization after exposure to LPS as determined by immunofluorescence analysis (Figure 2E). WMJ-S-001 markedly impaired the translocation of p65 from the cytosol to nucleus in cells exposed to LPS (Figure 2E). The results from the reporter assays also demonstrated that WMJ-S-001 reduced LPS-increased NF-κB-luciferase activities in RAW264.7 macrophages (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

WMJ-S-001 inhibited p65 activation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. (A) Cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 (1–10 μM) for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 6 h. The extent of COX-2 mRNA was then determined by an RT-PCR assay as described in the ‘Methods’ section. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of five independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. (B) Cells were transiently transfected with COX-2-luc and renilla-luc for 48 h. After transfection, cells were treated with vehicle or WMJ-S-001 (1–10 μM) for 30 min, followed by treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. Luciferase activity was then determined as described in the ‘Methods’ section. Data represent the mean ± SEM of at least five independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. (C) Cells were transiently transfected with WT COX-2-luc, mC/EBP-COX-2-luc (C/EBP site mutant) or mNFκB COX-2-luc (NFκB site mutant) and renilla-luc for 48 h. Luciferase activity was then determined after treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. Data represent the mean ± SEM of six independent experiments performed in duplicate. (D) Cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 (1–10 μM) for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 20 min. The extent of p65 phosphorylation was then determined by immunoblotting. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. (E) Cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 (10 μM) for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 1 h. p65 translocation was determined by immunofluorescence analysis as described in the ‘Methods’ section. Results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. (F) Cells were transiently transfected with NF-κB-luc and renilla-luc for 48 h. After transfection, cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 (1–10 μM) for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. Luciferase activity was then determined. Data represent the mean ± SEM of six independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.05, compared with the vehicle-treated group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. PI, propidium iodide.

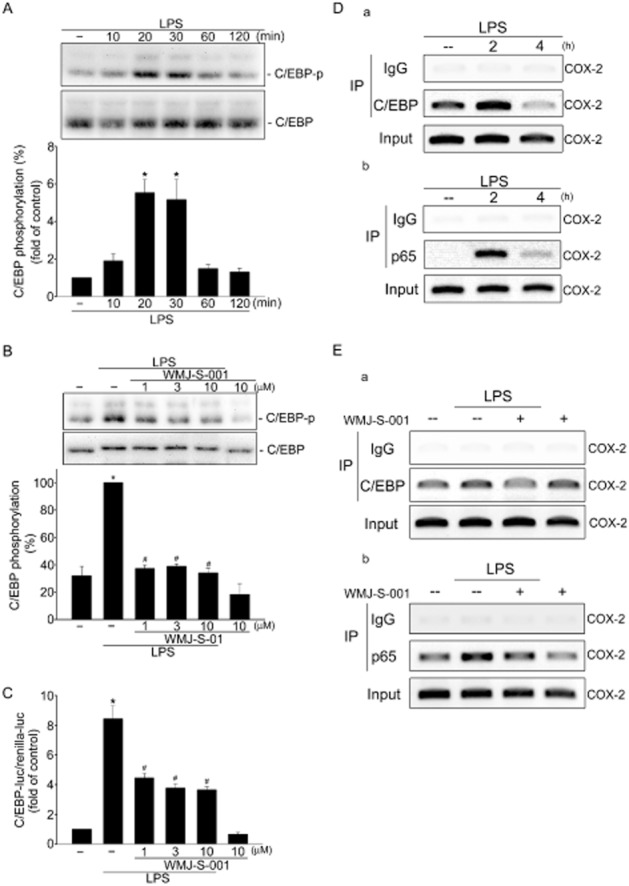

It has been reported that phosphorylation of C/EBPß promotes its transcriptional activity (Nakajima et al., 1993). We therefore determined the phosphorylation status of C/EBPß in RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to LPS. As shown in Figure 3A, LPS caused an increase in C/EBPß phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner. Treatment of cells with WMJ-S-001 significantly suppressed LPS-induced C/EBPß phosphorylation (Figure 3B). The results from the reporter assays also demonstrated that WMJ-S-001 reduced LPS-increased C/EBP-luciferase activities in RAW264.7 macrophages (Figure 3C). We next performed ChIP experiments to determine whether WMJ-S-001 affects the recruitment of p65 and C/EBPß to the endogenous COX-2 promoter region in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. The primers encompassing the COX-2 promoter regions between −230 and −60 (containing the C/EBPß-binding site), and between −466 and −304 (containing the NF-κB-binding site) were used. As shown in Figure 3D, C/EBPß binding to the COX-2 promoter region (−230/−60) was increased readily after LPS exposure (Figure 3Da). p65 binding to the COX-2 promoter region (−466/−304) was also increased in cells exposed to LPS (Figure 3Db). The COX-2 promoter region (−230/−60 or −466/−304) was detected in the cross-linked chromatin sample before immunoprecipitation (bottom panels of Figure 3Da and Db, input, positive control). Furthermore, LPS's effects on C/EBPß and p65 binding to the COX-2 promoter region were reduced in the presence of WMJ-S-001 (Figure 3Ea and Eb). These results suggest that C/EBPß and p65 may be responsible for the inhibitory effects of WMJ-S-001 on COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages.

Figure 3.

WMJ-S-001 attenuated C/EBPβ activation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. (A) Cells were treated with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for the indicated time periods. Cells were then harvested and C/EBPβ phosphorylation was determined by immunoblotting. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of at least five independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group. (B) Cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 (1–10 μM) for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 20 min. The extent of C/EBPβ phosphorylation was then determined by immunoblotting. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of five independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. (C) Cells were transiently transfected with C/EBP-luc and renilla-luc for 48 h. After transfection, cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 (1–10 μM) for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. Luciferase activity was then determined. Data represent the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.05, compared with the vehicle-treated group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. Cells were treated with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for the indicated time intervals (D) or treated with WMJ-S-001 (10 μM) for 30 min followed by the treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 2 h (E). ChIP assay was performed as described in the ‘Methods’ section. Typical traces representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results are shown.

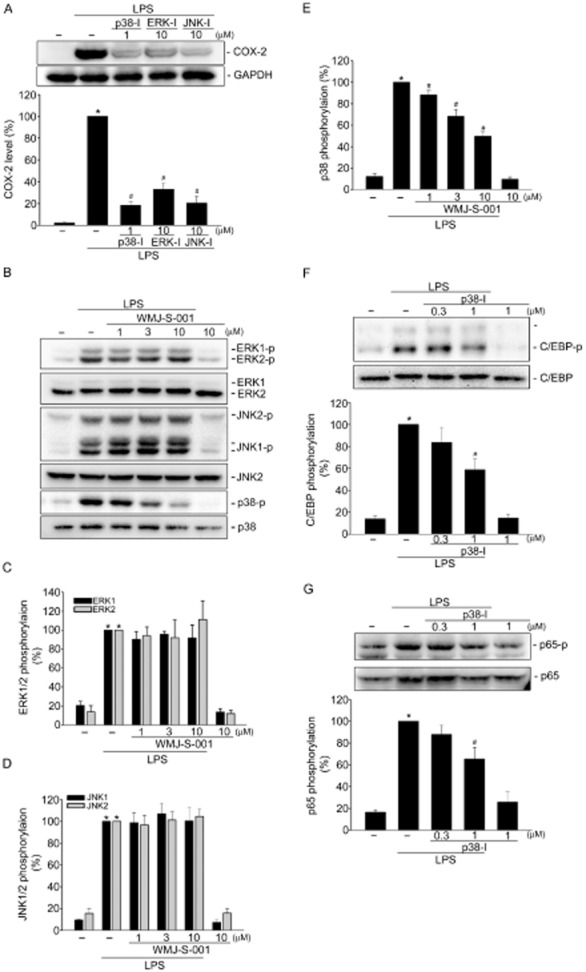

p38MAPK signalling contributes to WMJ-S-001 suppression of COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages

LPS induction of COX-2 occurs via activation of MAPKs including ERK, JNK and p38MAPK. To confirm whether ERK, p38MAPK or JNK1/2 signalling contributes to LPS-induced COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages, pharmacological inhibitors U0126 (an ERK signalling inhibitor, ERK-I), p38MAPK inhibitor III (a p38MAPK inhibitor, p38-I) and JNK1/2 inhibitor II (a JNK1/2 inhibitor, JNK-I) were used. As shown in Figure 4A, these three inhibitors were all effective in reducing LPS-induced COX-2 expression, suggesting the causal role of MAPKs in COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. In addition, these three inhibitors did not alter cell viability as determined by trypan blue dye exclusion assay (Supporting Information Fig. S2). It appears that the inhibitory effects of these three inhibitors on LPS-induced COX-2 expression were not attributable to cytotoxic effects. We next examined whether WMJ-S-001 affects the status of MAPKs activation to explore the inhibitory mechanisms of WMJ-S-001 on LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. As shown in Figure 4B, LPS caused increases in ERK, JNK and p38MAPK phosphorylation in RAW264.7 macrophages. The increase in ERK (Figure 4C) and JNK (Figure 4D) phosphorylation was not altered in the presence of WMJ-S-001. In contrast, WMJ-S-001 significantly inhibited LPS-induced p38MAPK phosphorylation in RAW264.7 macrophages (Figure 4E). Furthermore, we also used p38MAPK inhibitor III to confirm whether p38MAPK signalling contributes to LPS-induced C/EBPß and p65 phosphorylation. As shown in Figure 4F, p38MAPK inhibitor III at 1 μM significantly inhibited LPS-induced C/EBPß phosphorylation. Similarly, p38MAPK inhibitor III was also effective in attenuating LPS-induced p65 phosphorylation (Figure 4G). Taken together, these results suggest that WMJ-S-001 may inhibit p38MAPK signalling to suppress C/EBPß and p65 phosphorylation and COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages.

Figure 4.

Effects of WMJ-S-001 on p38MAPK signalling cascade in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. (A) Cells were pretreated with p38MAPK inhibitor III (p38-I, 1 μM), U0126 (ERK-I, 10 μM) or JNK inhibitor II (JNK-I, 10 μM) for 30 min followed by treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. The COX-2 level was then determined by immunoblotting. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of at least four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the vehicle-treated group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. Cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 (1–10 μM) for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 20 min. Figures shown in (B) are representative of at least four independent experiments with similar results. The compiled results of ERK (C), JNK (D) or p38MAPK (E) phosphorylations are shown. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of at least four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the vehicle-treated group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone. Cells were pretreated with the vehicle or p38MAPK inhibitor III (p38-I, 1 μM) for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 20 min. The extent of C/EBPβ (F) or p65 (G) phosphorylation was then determined by immunoblotting. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of at least four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the vehicle-treated group; #P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone.

MKP-1 plays a causal role in WMJ-S-001 suppression of COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages

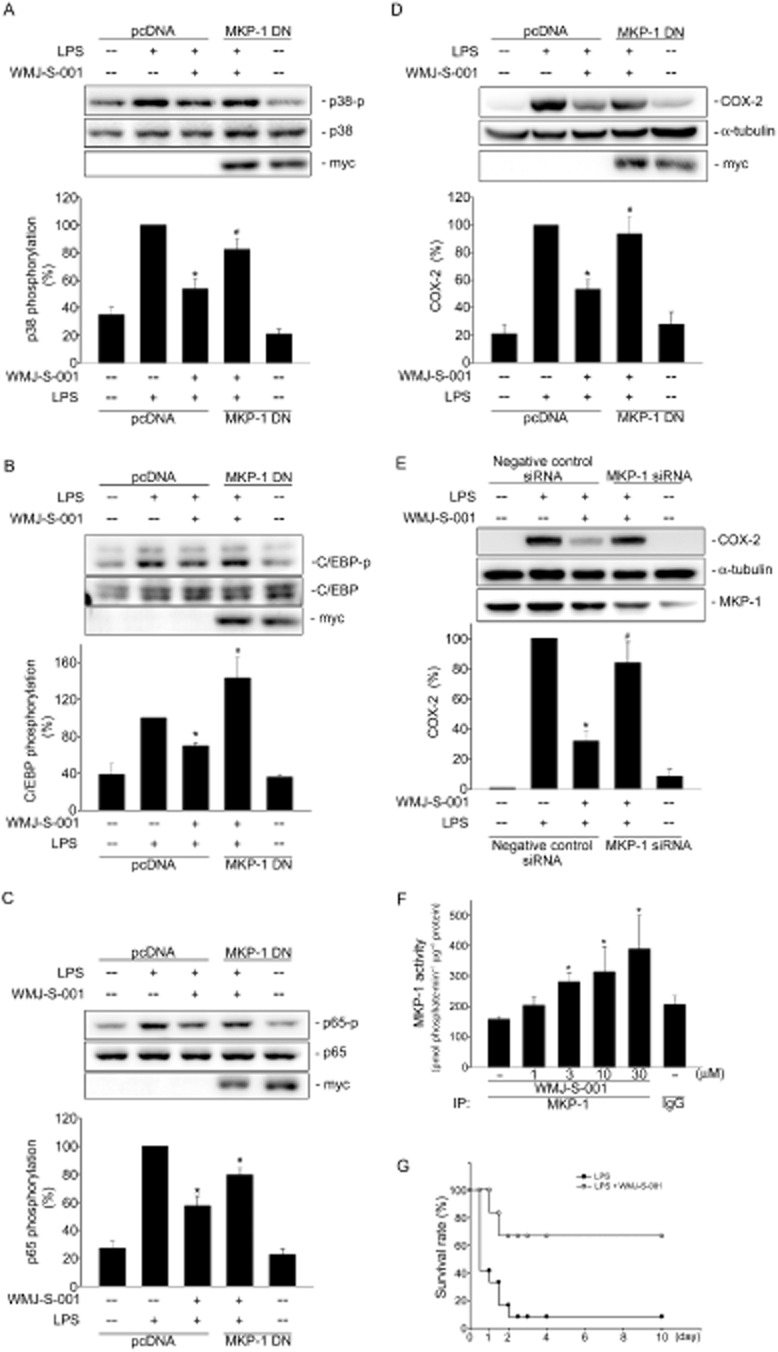

We next explored the underlying mechanisms of WMJ-S-001 in inhibiting LPS-induced p38MAPK phosphorylation. It is likely that WMJ-S-001 may activate a protein phosphatase that dephosphorylates p38MAPK and thereby down-regulates COX-2 expression. Several studies have showed that MKP-1 plays a crucial role in regulating inflammatory responses by dephosphorylating and inactivating p38MAPK (Jeffrey et al., 2007; Hsu et al., 2011; Chuang et al., 2014). We thus investigated whether MKP-1 mediates WMJ-S-001 dephosphorylation of p38MAPK in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. An MKP-1-DN construct was employed to confirm more specifically that WMJ-S-001's inhibitory actions on LPS-induced p38MAPK phosphorylation were mediated by MKP-1. As shown in Figure 5A, transfection of cells with MKP-1-DN restored WMJ-S-001-decreased p38MAPK phosphorylation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. The decreases in C/EBP (Figure 5B) and p65 (Figure 5C) phosphorylation by WMJ-S-001 were also prevented by MKP-1-DN. Whether MKP-1-DN alters the inhibitory effects of WMJ-S-001 on LPS-induced COX-2 expression was also determined. As shown in Figure 5D, transfection of cells with MKP-1-DN significantly restored WMJ-S-001-decreased COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. We also used MKP-1 siRNA to confirm that WMJ-S-001's inhibitory actions on LPS-induced COX-2 expression were mediated by MKP-1. As shown in Figure 5E, transfection of HUVECs with MKP-1 siRNA significantly restored WMJ-S-001-decreased COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to LPS. Furthermore, WMJ-S-001 caused an increase in MKP-1 activity (Figure 5F). To evaluate the suppressive effect of WMJ-S-001 on systemic inflammation induced by endotoxaemia, mice were injected with LPS (15 mg·kg−1, i.p.). As shown in Figure 5F, WMJ-S-001 at 20 mg·kg−1 prevented LPS-induced mouse death, and the survival rate was about 65% at 20 mg·kg−1 at 72 h. Most of the control mice were dead within 48 h and the survival rate was about 10% at 72 h (Figure 5G). Taken together, these results suggest that MKP-1 is responsible for WMJ-S-001-induced suppression of p38MAPK phosphorylation, leading to COX-2-PGE2 down-regulation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages.

Figure 5.

MKP-1 contributed to WMJ-S-001-induced suppression of p38MAPK, C/EBPβ and p65 phosphorylation and COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to LPS. Cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA or MKP-1-DN for 48 h followed by 30 min of treatment with WMJ-S-001 (10 μM). Cells were then treated with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h (A) or 20 min (B–D). The COX-2 level (A) and phosphorylation status of p38MAPK (B), C/EBPβ (C) and p65 (D) were then determined by immunoblotting. The compiled results are shown in the bottom of the charts. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of at least four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone; #P < 0.05, compared with the LPS-treated group in the presence of WMJ-S-001. (E) Cells were transiently transfected with negative control siRNA or MKP-1 siRNA for 48 h followed by 30 min of treatment with WMJ-S-001 (10 μM). Cells were then treated with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. The COX-2 and MKP-1 levels were then determined by immunoblotting. The compiled results are shown at the bottom of the charts. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the group treated with LPS alone; #P < 0.05, compared with the LPS-treated group in the presence of WMJ-S-001. (F) Cell homogenates were treated with WMJ-S-001 at the indicated concentrations for 20 min. MKP-1 activity assay was determined as described in the ‘Methods’ section. Data represent the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the vehicle-treated control group. (G) Mice were pretreated with WMJ-S-001 (20 mg·kg−1) and then stimulated with LPS (15 mg·kg−1, i.p.) in PBS buffer. LPS-treated mice with or without WMJ-S-001 treatment were observed for 10 days and their survival rates were recorded. Mice in the control group were administered LPS alone (n = 12) and the other group was administered LPS plus 20 mg·kg−1 WMJ-S-001 (n = 6). IP, immunoprecipitation.

Discussion

Hydroxamate derivatives exhibit broad pharmacological properties including anti-tumour, anti-infectious and anti-inflammatory activities (Jiang et al., 2012; Bertrand et al., 2013; Venugopal et al., 2013; Rodrigues et al., 2014). To develop anti-inflammatory agents for the treatment of dysregulated or excessive inflammatory diseases, we evaluated the effects of a series of novel aliphatic hydroxamate derivatives, WMJ-S compounds, on COX-2 expression in activated macrophages exposed to LPS. In this study, we have identified a novel aliphatic hydroxamate derivative, WMJ-S-001, as a potent inhibitor in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. The results from the present study demonstrated that WMJ-S-001 may cause MKP-1 activation to dephosphorylate p38MAPK, leading to the decrease in p65 and C/EBPβ binding to the COX-2 promoter region and COX-2 down-regulation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages.WMJ-S-001 was also shown to protect mice from lethal endotoxaemia induced by LPS in an animal model of endotoxaemia.

MAPKs are involved in regulating the production of crucial inflammatory mediators such as COX-2 in endothelial cells (Hsu et al., 2011; Chuang et al., 2014) and macrophages (Hsu et al., 2010). It has been reported that p38MAPK and JNK inhibitors exhibit anti-inflammatory activities by suppressing the expression of inflammatory mediators. Several novel agents that modulate the JNK and p38 MAPK signalling pathways have been shown to be effective in treating chronic inflammatory diseases (Kumar et al., 2003; Kaminska, 2005). We noted in this study that ERK, JNK and p38MAPK contribute to LPS-induced COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages. However, only p38MAPK signalling blockade was causally related to WMJ-S-001 suppression of COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. Previous studies have demonstrated that MKP-1 negatively regulates p38MAPK, resulting in the down-regulation of pro-inflammatory mediators (Lasa et al., 2002; Turpeinen et al., 2010). In addition, both p38MAPK and JNK are negatively regulated by MKP-1 in endothelial cells (Hsu et al., 2011; Chuang et al., 2014). MKP-1 was shown to regulate JNK in pulmonary smooth muscle cells (Grant et al., 2007) and p38MAPK in macrophages (Salojin et al., 2006). These observations suggest that the substrate specificity of MKP-1 varies among cell types. In addition to p38MAPK and JNK, MKP-1 also dephosphorylates and therefore inactivates ERK (Liu et al., 2005). Furthermore, the MKP-1 phosphatase activity has been reported to be context-dependent. In a given situation, not all three MAPKs are targeted for dephosphorylation (Wu and Bennett, 2005a; Wu et al., 2005b). In agreement with these observations, we noted that MKP-1-DN restored WMJ-S-001's dephosphorylation of p38MAPK. It is likely that WMJ-S-001 activates MKP-1 to inactivate p38MAPK signalling, leading to a decrease in the expression of COX-2 in RAW264.7 macrophages. Further investigations are needed to explore whether WMJ-S-001 also inactivates p38MAPK signalling through an MKP-1-independent mechanism in RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to LPS.

The precise mechanism involved in WMJ-S-001-induced MKP-1 activation in RAW264.7 macrophages remains unclear. It has been reported that MKP-1 could be regulated through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms (Liu et al., 2007). In a recent study it was shown that dexamethasone exhibits anti-inflammatory effects by augmenting MKP-1 expression and its activity in LPS-stimulated macrophages (Abraham et al., 2006). We noted that WMJ-S-001 increased MKP-1 activity in RAW264.7 macrophages. Further investigations are needed to explore whether WMJ-S-001 augments MKP-1 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. In addition, hydroxamate derivatives have been shown to act as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors to increase acetylation of cellular signalling molecules (Drummond et al., 2005). The acetylation of MKP-1 may enhance its phosphatase activity (Cao et al., 2008) and increase its interaction with p38MAPK to dephosphorylate p38MAPK (Jeong et al., 2014). WMJ-S-001 was also shown to inhibit HDACs activity (unpubl. data). These results raise the possibility that WMJ-S-001 may activate MKP-1 to inhibit COX-2 expression through, at least in part, an inhibitory effect on HDAC. Whether WMJ-S-001 increases acetylation of MKP-1 or other signalling molecules, which contribute to its anti-inflammatory effects in RAW264.7 macrophages will need to be investigated further.

Previous studies reported that transcription factors including NF-κB, C/EBP, SP1 and CREB have been implicated in the induction of COX-2 expression (Kang et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2010). These transcription factors may participate in a sequential, coordinated regulation of COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages (Kang et al., 2006). We noted in reporter and ChIP assays that LPS increased NF-κB and C/EBP-luciferase activities and the recruitment of NF-κB and C/EBPβ to the endogenous cox-2 promoter region in RAW264.7 macrophages. This phenomenon was markedly suppressed in the presence of WMJ-S-001. The reporter assays further demonstrated that LPS-increased COX-2 promoter luciferase activity was attenuated in cells transfected with the reporter constructs containing a deletion of the NF-κB or the C/EBP site. These findings suggest that NF-κB and C/EBPβ play important roles in WMJ-S-001 suppression of LPS-induced COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages. The exact mechanism by which WMJ-S-001 inhibited NF-κB and C/EBPβ binding to the cox-2 promoter region remains to be elucidated. Consistent with the previous reports that p38MAPK regulates NF-κB and C/EBPβ (Hsu et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2010), we noted that the p38MAPK inhibitor suppressed LPS-induced NF-κB subunit p65 and C/EBPβ phosphorylation. It appears that p38MAPK signalling blockade by MKP-1 may contribute to the inhibitory actions of WMJ-S-001 on NF-κB and C/EBPβ. Moreover, we noted in this study that the p38MAPK inhibitor, similar to WMJ-S-001, dose-dependently inhibited p65 phosphorylation. C/EBPβ phosphorylation seemed to be similarly inhibited by the p38MAPK inhibitor in a dose-dependent manner, and WMJ-S-001 at a lower concentration (1 μM) strongly inhibited C/EBPβ phosphorylation in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. Several studies have reported that C/EBPβ phosphorylation is also regulated by ribosomal protein S6 kinase (RSK) (Buck and Chojkier, 2007) and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) (Tang et al., 2005). This raises the possibility that WMJ-S-001 inhibits C/EBPβ phosphorylation through targeting RSK or GSK3β in addition to p38MAPK. Further investigations are needed to characterize whether other signalling molecules such as RSK and GSK3β contribute to the anti-inflammatory actions of WMJ-S-001. These observations explain, at least in part, the different patterns of inhibition of C/EBPβ phosphorylation in the presence of the p38MAPK inhibitor and WMJ-S-001.

Moreover, physical and functional interactions have been shown to occur between C/EBP and NF-κB family members (Banks and Erickson, 2010). Whether WMJ-S-001 affects the interactions between C/EBPβ and NF-κB or other transcription factors in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages needs to be investigated further. Furthermore, HDAC3 has been reported to interact with the NF-κB p65 subunit (Chen et al., 2001) and to de-acetylate NF-κB, which contributes to its association with IκBα (Winkler et al., 2012). Hence, it would be worth clarifying whether WMJ-S-001's inhibitory actions in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages are also attributable to its HDAC inhibitory activity.

As described earlier, we showed that WMJ-S-001 inhibited LPS-induced COX-2 promoter luciferase activity, suggesting that WMJ-S-001 may modulate COX-2 expression at the transcriptional level. However, the control of COX-2 protein expression may also occur at levels other than transcription such as chromatin modifications and post-transcriptional regulation via 3′-UTR (Harper and Tyson-Capper, 2008). There are many adenylate–uridylate-rich elements (AU-rich elements, AREs) and microRNA response elements in the COX-2 3′-UTR. When these elements are recognized and bound by specific ARE-binding factors or miRNAs, the stability of COX-2 and its translational efficiency will be affected (Harper and Tyson-Capper, 2008). In addition, the p38MAPK signalling pathways have been shown to contribute to the regulation of COX-2 mRNA stability (Monick et al., 2002). The COX-2 protein stability may also be altered through an N-glycosylation-mediated mechanism or substrate-dependent degradation process (Mbonye et al., 2008). This raises the possibility that WMJ-S-001 may activate the MKP-1 to suppress COX-2 protein expression by both transcriptional and post-transcriptional or post-translational mechanisms. Further investigations are needed to elucidate whether ARE-binding factors, miRNAs or protein modifications contribute to WMJ-S-001's modulation of COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages.

In conclusion, we demonstrated in this study that WMJ-S-001, a novel aliphatic hydroxamate derivative, significantly suppressed COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. We also showed that MKP-1 contributed to the p38MAPK dephosphorylation and subsequent COX-2 down-regulation in the presence of WMJ-S-001.

Together these findings suggest that WMJ-S-001 may act as a promising therapeutic agent against inflammatory diseases. The precise underlying mechanisms of WMJ-S-001 in suppressing inflammation and the more potent compounds derived from its structure should be further characterized and developed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Byron Wingerd (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, SUA) for the kind gift of the murine COX-2 promoter with wild-type construct (native −966/+23) and mutant constructs cloned into pGL3-basic vector (Promega); Dr Nichola Tonks (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York) for the kind gift of the catalytically inactive MKP1-C258S (MKP1-DN); Dr Kjetil Tasken (University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway) for the kind gift of C/EBP-luc reporter construct. This work was supported by grant NSC 102-2320-B-038-047 from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan and grant 102CM-TMU-12 from the Chi Mei Medical Center, Tainan, Taiwan.

Glossary

- DN

dominant-negative

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- MKP

MAPK phosphatase

Author contributions

W.-C. C., C.-S. Y. and M.-J. H. designed the experiments. W. C. C. and C. S. Y. performed the experiments. W. C. C., Y.-F. H. and M.-J. H. analysed the data. W.-J. H. contributed reagents and synthesized WMJ-S compounds. W.-C. C., G. O. and M.-J. H. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

Figure S1 WMJ-S-001 concentration-dependently suppressed COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to LPS. (A) Cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 at indicated concentrations for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. The COX-2 level was then determined by immunoblotting. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of six independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; (B) based on the results derived from A, the IC50 of WMJ-S-001 was calculated.

Figure S2 Effects of MAPK inhibitors on cell viability in RAW264.7 macrophages. Cells were pretreated with p38MAPK inhibitor III (p38-I, 1 μM), U0126 (ERK-I, 10 μM) or JNK inhibitor II (JNK-I, 10 μM) for 24 h. Cell viability was determined using a trypan blue dye exclusion test. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments.

References

- Abraham SM, Lawrence T, Kleiman A, Warden P, Medghalchi M, Tuckermann J, et al. Antiinflammatory effects of dexamethasone are partly dependent on induction of dual specificity phosphatase 1. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1883–1889. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1797–1867. doi: 10.1111/bph.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Erickson MA. The blood–brain barrier and immune function and dysfunction. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand S, Helesbeux JJ, Larcher G, Duval O. Hydroxamate, a key pharmacophore exhibiting a wide range of biological activities. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2013;13:1311–1326. doi: 10.2174/13895575113139990007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B, Rietschel ET. Innate immune sensing and its roots: the story of endotoxin. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:169–176. doi: 10.1038/nri1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck M, Chojkier M. C/EBPbeta phosphorylation rescues macrophage dysfunction and apoptosis induced by anthrax lethal toxin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1788–C1796. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00141.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Bao C, Padalko E, Lowenstein CJ. Acetylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 inhibits Toll-like receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1491–1503. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Fischle W, Verdin E, Greene WC. Duration of nuclear NF-kappaB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science. 2001;293:1653–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.1062374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, Barry SP, Roth RJ, Wu JJ, Jones EA, Bennett AM, et al. Dynamic regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) in innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2274–2279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510965103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YF, Yang HY, Ko TL, Hsu YF, Sheu JR, Ou G, et al. Valproic acid suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression via MKP-1 in murine brain microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson RJ, Keyse SM. Diverse physiological functions for dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 22):4607–4615. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. MAP kinases in the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:55–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091301.131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DC, Noble CO, Kirpotin DB, Guo Z, Scott GK, Benz CC. Clinical development of histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer agents. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:495–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejima K, Layne MD, Carvajal IM, Kritek PA, Baron RM, Chen YH, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice are resistant to endotoxin-induced inflammation and death. FASEB J. 2003;17:1325–1327. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1078fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq A, Zhou MM. Structure and regulation of MAPK phosphatases. Cell Signal. 2004;16:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier WJ, Wang X, Wancket LM, Li XA, Meng X, Nelin LD, et al. Increased inflammation, impaired bacterial clearance, and metabolic disruption after gram-negative sepsis in Mkp-1-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2009;183:7411–7419. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioannini TL, Weiss JP. Regulation of interactions of Gram-negative bacterial endotoxins with mammalian cells. Immunol Res. 2007;39:249–260. doi: 10.1007/s12026-007-0069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauben R, Batra A, Fedke I, Zeitz M, Lehr HA, Leoni F, et al. Histone hyperacetylation is associated with amelioration of experimental colitis in mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:5015–5022. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.5015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, Easley C, Kirkpatrick P. Vorinostat. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:21–22. doi: 10.1038/nrd2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper KA, Tyson-Capper AJ. Complexity of COX-2 gene regulation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36(Pt 3):543–545. doi: 10.1042/BST0360543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu MJ, Chang CK, Chen MC, Chen BC, Ma HP, Hong CY, et al. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in peptidoglycan-induced COX-2 expression in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:1069–1082. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1009668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu YF, Sheu JR, Lin CH, Chen WC, Hsiao G, Ou G, et al. MAPK phosphatase-1 contributes to trichostatin A inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells exposed to lipopolysaccharide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1810:1160–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YH, Yang HY, Hsu YF, Chiu PT, Ou G, Hsu MJ. Src contributes to IL6-induced vascular endothelial growth factor-C expression in lymphatic endothelial cells. Angiogenesis. 2013;17:407–418. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9386-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YH, Yang HY, Hsu YF, Chiu PT, Ou G, Hsu MJ. Src contributes to IL6-induced vascular endothelial growth factor-C expression in lymphatic endothelial cells. Angiogenesis. 2014;17:407–418. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9386-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey KL, Camps M, Rommel C, Mackay CR. Targeting dual-specificity phosphatases: manipulating MAP kinase signalling and immune responses. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:391–403. doi: 10.1038/nrd2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y, Du R, Zhu X, Yin S, Wang J, Cui H, et al. Histone deacetylase isoforms regulate innate immune responses by deacetylating mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:651–659. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1013565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Thyagarajan-Sahu A, Krchnak V, Jedinak A, Sandusky GE, Sliva D. NAHA, a novel hydroxamic acid-derivative, inhibits growth and angiogenesis of breast cancer in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Samuvel DJ, Zhang X, Li Y, Lu Z, Lopes-Virella MF, et al. Coactivation of TLR4 and TLR2/6 coordinates an additive augmentation on IL-6 gene transcription via p38MAPK pathway in U937 mononuclear cells. Mol Immunol. 2011;49:423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminska B. MAPK signalling pathways as molecular targets for anti-inflammatory therapy – from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic benefits. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YJ, Wingerd BA, Arakawa T, Smith WL. Cyclooxygenase-2 gene transcription in a macrophage model of inflammation. J Immunol. 2006;177:8111–8122. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Boehm J, Lee JC. p38 MAP kinases: key signalling molecules as therapeutic targets for inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:717–726. doi: 10.1038/nrd1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, Hammer M, Mages J. DUSP meet immunology: dual specificity MAPK phosphatases in control of the inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2006;177:7497–7504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasa M, Abraham SM, Boucheron C, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Dexamethasone causes sustained expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase 1 and phosphatase-mediated inhibition of MAPK p38. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7802–7811. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7802-7811.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Verma IM. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:725–734. doi: 10.1038/nri910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin ML, Lu YC, Chung JG, Wang SG, Lin HT, Kang SE, et al. Down-regulation of MMP-2 through the p38 MAPK-NF-kappaB-dependent pathway by aloe-emodin leads to inhibition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell invasion. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:783–797. doi: 10.1002/mc.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Shi Y, Du Y, Ning X, Liu N, Huang D, et al. Dual-specificity phosphatase DUSP1 protects overactivation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 through inactivating ERK MAPK. Exp Cell Res. 2005;309:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SF, Malik AB. NF-kappa B activation as a pathological mechanism of septic shock and inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L622–L645. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Shepherd EG, Nelin LD. MAPK phosphatases – regulating the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:202–212. doi: 10.1038/nri2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbonye UR, Yuan C, Harris CE, Sidhu RS, Song I, Arakawa T, et al. Two distinct pathways for cyclooxygenase-2 protein degradation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8611–8623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev AE, Kopydlowski KM, Vogel SN. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction in endotoxin-tolerized mouse macrophages: dysregulation of cytokine, chemokine, and toll-like receptor 2 and 4 gene expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:5564–5574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monick MM, Robeff PK, Butler NS, Flaherty DM, Carter AB, Peterson MW, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity negatively regulates stability of cyclooxygenase 2 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32992–33000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Kinoshita S, Sasagawa T, Sasaki K, Naruto M, Kishimoto T, et al. Phosphorylation at threonine-235 by a ras-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade is essential for transcription factor NF-IL6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2207–2211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42:D1098–1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. (Database Issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman M, Chen W, Cobb MH. Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene. 2007;26:3100–3112. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciotti E, FitzGerald GA. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:986–1000. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues GC, Feijo DF, Bozza MT, Pan P, Vullo D, Parkkila S, et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of hydroxamic acid derivatives as promising agents for the management of Chagas disease. J Med Chem. 2014;57:298–308. doi: 10.1021/jm400902y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth RJ, Le AM, Zhang L, Kahn M, Samuel VT, Shulman GI, et al. MAPK phosphatase-1 facilitates the loss of oxidative myofibers associated with obesity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3817–3829. doi: 10.1172/JCI39054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salojin KV, Owusu IB, Millerchip KA, Potter M, Platt KA, Oravecz T. Essential role of MAPK phosphatase-1 in the negative control of innate immune responses. J Immunol. 2006;176:1899–1907. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishodia S, Koul D, Aggarwal BB. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor celecoxib abrogates TNF-induced NF-kappa B activation through inhibition of activation of I kappa B alpha kinase and Akt in human non-small cell lung carcinoma: correlation with suppression of COX-2 synthesis. J Immunol. 2004;173:2011–2022. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Endotoxin signal transduction in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:8–26. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang QQ, Gronborg M, Huang H, Kim JW, Otto TC, Pandey A, et al. Sequential phosphorylation of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta by MAPK and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta is required for adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9766–9771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503891102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoyi K, Jang HJ, Nizamutdinova IT, Kim YM, Lee YS, Kim HJ, et al. Metformin inhibits HMGB1 release in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells and increases survival rate of endotoxaemic mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1498–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpeinen T, Nieminen R, Moilanen E, Korhonen R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 negatively regulates the expression of interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and cyclooxygenase-2 in A549 human lung epithelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333:310–318. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.157438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal B, Baird R, Kristeleit RS, Plummer R, Cowan R, Stewart A, et al. A phase I study of quisinostat (JNJ-26481585), an oral hydroxamate histone deacetylase inhibitor with evidence of target modulation and antitumor activity, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4262–4272. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Yu C, Pan Y, Li J, Zhang Y, Ye F, et al. A novel compound C12 inhibits inflammatory cytokine production and protects from inflammatory injury in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CS, Mann M, DuBois RN. The role of cyclooxygenases in inflammation, cancer, and development. Oncogene. 1999;18:7908–7916. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler AR, Nocka KN, Williams CM. Smoke exposure of human macrophages reduces HDAC3 activity, resulting in enhanced inflammatory cytokine production. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012;25:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Marko M, Claycombe K, Paulson KE, Meydani SN. Ceramide-induced and age-associated increase in macrophage COX-2 expression is mediated through up-regulation of NF-kappa B activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10983–10992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JJ, Bennett AM. Essential role for mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase phosphatase-1 in stress-responsive MAP kinase and cell survival signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005a;280:16461–16466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Pew T, Zou M, Pang D, Conzen SD. Glucocorticoid receptor-induced MAPK phosphatase-1 (MPK-1) expression inhibits paclitaxel-associated MAPK activation and contributes to breast cancer cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2005b;280:4117–4124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Wang X, Nelin LD, Yao Y, Matta R, Manson ME, et al. MAP kinase phosphatase 1 controls innate immune responses and suppresses endotoxic shock. J Exp Med. 2006;203:131–140. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 WMJ-S-001 concentration-dependently suppressed COX-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages exposed to LPS. (A) Cells were pretreated with the vehicle or WMJ-S-001 at indicated concentrations for 30 min before treatment with LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for another 24 h. The COX-2 level was then determined by immunoblotting. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of six independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; (B) based on the results derived from A, the IC50 of WMJ-S-001 was calculated.

Figure S2 Effects of MAPK inhibitors on cell viability in RAW264.7 macrophages. Cells were pretreated with p38MAPK inhibitor III (p38-I, 1 μM), U0126 (ERK-I, 10 μM) or JNK inhibitor II (JNK-I, 10 μM) for 24 h. Cell viability was determined using a trypan blue dye exclusion test. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments.