Abstract

Dominant theoretical models of social anxiety disorder (SAD) suggest that people who suffer from function-impairing social fears are likely to react more strongly to social stressors. Researchers have examined the reactivity of people with SAD to stressful laboratory tasks, but there is little knowledge about how stress affects their daily lives. We asked 79 adults from the community, 40 diagnosed with SAD and 39 matched healthy controls, to self-monitor their social interactions, social events, and emotional experiences over two weeks using electronic diaries. These data allowed us to examine associations of social events and emotional well-being both within-day and from one day to the next. Using hierarchical linear modeling, we found all participants to report increases in negative affect and decreases in positive affect and self-esteem on days when they experienced more stressful social events. However, people with SAD displayed greater stress sensitivity, particularly in negative emotion reactions to stressful social events, compared to healthy controls. Groups also differed in how previous days’ events influenced sensitivity to current days’ events. Moreover, we found evidence of stress generation in that the SAD group reported more frequent interpersonal stress, though temporal analyses did not suggest greater likelihood of social stress on days following intense negative emotions. Our findings support the role of heightened social stress sensitivity in SAD, highlighting rigidity in reactions and occurrence of stressful experiences from one day to the next. These findings also shed light on theoretical models of emotions and self-esteem in SAD and present important clinical implications.

Keywords: social anxiety disorder, emotion differentiation, negative emotions, social interaction, experience sampling methodology

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is characterized by intense distress in anticipation of, during, and after social situations in which an individual may be scrutinized or devalued in the eyes of others (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This is one of the most common psychological disorders in the United States affecting 10–15% of the general population at some point during life (Grant et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2005). SAD is associated with a detrimental impact on an individual’s well-being, relationship functioning, and achievements in educational and career domains (Schneier et al., 1994), contributing to a financial burden that rivals that of depression (Tolman et al., 2009). By its nature SAD is a condition tied to an individual’s social environment, and theorists have recognized the importance of social events to the disorder’s symptomology. Yet, we know little about how social stress in the natural course of daily life affects people with SAD. This study aimed to better understand the temporal processes involved in social events, emotion, and self-esteem experiences of adults diagnosed with SAD. In particular, we sought to examine whether individuals with SAD display heightened emotional reactivity to social stress and whether they experience heightened occurrence of social stress in their daily lives compared to healthy adults.

A Theoretical Framework for Stress Sensitivity in SAD

Dominant theories of SAD have emphasized the role of social stress in the onset and maintenance of social fears (e.g., Clark & Wells, 1995; Heimberg, Brozovich, & Rapee, 2010; Hofmann, 2007). These models argue that people with SAD have unhelpful beliefs and assumptions about social interactions (e.g., unattainable social standards, high likelihood of rejection) that lead them to excessively focus on minimizing behaviors or expressions that might elicit judgment. This self-focus in turn increases physiological arousal (e.g., sweating) and negative social-evaluative thoughts. Thus, stressful social situations are presumed to increase negative emotions and decrease self-esteem—the emotional evaluation of one’s worth—in people with SAD. That is, individuals with SAD may have a heightened sensitivity to social stress as a result of maladaptive cognitive processes in the context of interpersonal events with potential for negative evaluation.

Sensitivity to daily social events

Daily stressors, particularly in the form of interpersonal conflict, can have a profound impact on daily mood and self-esteem in the general population (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989; Nezlek & Plesko, 2001). Some people are likely to be more reactive to such events than others. People with SAD have a stronger physiological response (e.g., increased heart rate) to stressful tasks in the laboratory like giving an impromptu speech (Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1987; Roelofs et al., 2009). They also exhibit greater neural activation in response to social threat compared to peers (Goldin, Manber, Hakimi, Canli, & Gross, 2009). These studies suggest that people with SAD will also be more reactive to daily social stressors in their lives than healthy controls.

Atypical sensitivity to daily social events has been demonstrated in other forms of psychopathology. Myin-Germeys and colleagues (2003) compared clients with major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder (BD), and psychosis without mood disturbances to a healthy comparison group. Compared to controls, the authors found that clients with MDD reported more negative affect associated with stressors, while patients with BD reported reduced positive affect, and those with psychosis reported more intense changes in both positive and negative affect in response to stress. Other studies have found clients with MDD to experience stronger responses to positive events (reductions in negative affect), while reactions to negative events were blunted (Peeters, Nicolson, Berkhof, Delespaul, & deVries, 2003) or similar to those of controls (Thompson et al., 2012). These differences highlight the importance of considering the effects of both positive and negative events on both positive and negative affect reactions.

Spillover of reactions to social events

Thus far, we have discussed sensitivity influences of social events on same-day emotions and self-esteem (i.e., concurrent effects). There are also individual differences in how affect and self-esteem reactions persist into the following day (i.e., lagged effects). For example, Peeters et al. (2003) also found that clients with MDD experience more prolonged negative affect in reaction to daily stressors compared to healthy controls.

Following social situations, people may engage in post-event processing, a thought process in which they recall and analyze their own and others’ behaviors in the situation. For people with elevated social anxiety, this process most often focuses on their flaws or mistakes that might have led to negative evaluation (Brozovich & Heimberg, 2008). This negative self-focus is likely to maintain or intensify negative emotions. Since this process occurs over hours or even days following negative events, people with SAD may be more likely to experience longer lasting reactions to social stressors.

Only one study to date has examined spillover of reactions to stressful events in people with anxiety difficulties. Starr and Davila (2012) assessed 55 individuals with generalized anxiety disorder over 21 days for affective, cognitive, and interpersonal experiences. They found participants to experience spillover of anxious mood (T–2) into later depressed mood (T), particularly when they experienced more social stressors and more perceived rejection (T–2). Taking a longitudinal approach, Auerbach, Richardt, Kertz, and Eberhart (2012) assessed adolescents every six weeks for six months on stressors and social anxiety symptoms. The authors found social and non-social stress at each occasion (T–1) to significantly predict higher social anxiety levels on the following assessment (T) for girls. Taken together, these studies support the hypothesis that daily stressors may influence not only same-day emotional and self-evaluative experiences but also following days’ experiences.

A Theoretical Framework for Stress Generation in SAD

Most stress research has focused on the causal pathway between stressful events and emotional experiences as unidirectional whereby the stress is presumed to impair well-being. A growing body of literature suggests that individuals vulnerable to psychopathology may not only be more psychologically and neurologically reactive to stress but also contribute to increased frequency of stressors in their lives (see Hammen, 2005 for review). Social stress is an example of such dependent stress, the occurrence of which is likely to be influenced by an individual’s own behavior either directly or indirectly. While some researchers have suggested that the stress generation may be specific to depression (Joiner, Wingate, Gencoz, & Gencoz, 2005), one study comparing adolescents with depression, anxiety, or both found comorbidity to be associated with most social stressors in the past year, compared to either disorder type alone (Connolly, Eberhart, Hammen, & Brennan, 2010). This may mean that the stress generation model originally developed to understand depression (Hammen, 1991) may also be useful to understanding other psychological disorders.

The stress generation model may be particularly applicable to anxiety disorders like SAD, due to common vulnerability factors. Recent studies have found cognitive vulnerability factors associated with both anxiety and depression to predict stress generation (Riskind, Black, & Shahar, 2010; Safford, Alloy, Abramson, & Crossfield, 2007). Additionally, both depression and anxiety disorders significantly overlap in general distress (Watson, Clark, & Carey, 1988), which may contribute to stress generation in these disorders. It is possible that stress sensitivity and stress generation may play unique and possibly synergistic roles in the maintenance of anxiety symptoms. For example, if people experience a heightened occurrence of anxiety-provoking situations to which their reactions are sensitized over time, they may have difficulty learning or utilizing adaptive coping strategies.

Occurrence of daily social stress in SAD

In the context of a stress generation model, people with SAD would be presumed to experience more frequent social stress. However, findings have been mixed. Daily diary methodology, which assesses individuals’ experiences over time with a series of daily self-reports, can give us a glimpse into people’s daily lives (Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 1987). Using this method, researchers found children with SAD to report more frequent socially stressful events (Beidel, Turner, & Morris, 1999). In the only study on social stress in adults with SAD, Yeganeh (2005) compared the daily occupational experiences of people with and without SAD and found those with SAD to report greater hardship in their work relationships. Notably, this study was limited in context to a work environment. In the only study to examine social stressors in the context of the daily lives of adults with elevated social anxiety, Farmer and Kashdan (2012) found no association between social anxiety (on a continuum) and the frequency of daily negative social events. Notably, this study used an undergraduate sample in which participants did not undergo careful diagnostic interviews. Taken together with studies on children and in a work context, this research suggests that there may be increased occurrence of dependent stressors for people with SAD.

Notably, avoidance of anxiety-provoking social situations is part of the criteria for a diagnosis of SAD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). It is quite likely that avoidance of potentially stressful interactions (e.g., meeting with a co-worker) may also limit the possibilities for positive social experiences to occur (e.g., having pleasant conversation resulting in social plans). It is worth noting that people with elevated social anxiety tend to engage in fewer social interactions overall than less anxious counterparts (Dodge, Heimberg, Nyman, & O’Rien, 1987). Consistent with this, elevated social anxiety has been associated with fewer daily positive events, particularly on days when people feel most socially anxious and make attempts to suppress their emotions (Kashdan & Steger, 2006). Consequently, people with SAD may be expected to experience less frequent positive social events compared to healthy controls.

The question of whether people with SAD experience more frequent negative social events is complicated by interpretive and memory biases. Past research suggests that how people perceive a stressor in everyday life may be more relevant to their well-being than just whether or not a stressor occurs (Bolger & Schilling, 1991). People with SAD tend to interpret ambiguous social information as negative or threatening (Amin, Foa, & Coles, 1998) and mildly negative information as having catastrophic consequences, even in comparison to people with other anxiety disorders (Stopa & Clark, 2000). Even social events that most people would consider pleasant (e.g., being praised) tend to be more distressing for people with SAD (Alden & Wallace, 1995). This may be due to concerns about managing anxiety during the course of the event or a general discomfort with positive evaluation (Weeks, Heimberg, Rodebaugh, & Norton, 2008). Overall, this research suggests that people with SAD are likely to perceive and remember social events as stressful and may ascribe more importance to negative social events.

Prospective daily stress generation in SAD

Although most literature on stress generation uses retrospective or prospective methods with major life events, a daily diary approach brings a number of methodological advantages (Liu & Alloy, 2010). Most importantly, emotions and perceived social stress tend to have rapid fluctuations, with quick rebounds to baseline levels (Stader & Hokanson, 1998). In the first stress generation study to take a daily approach, hostility (but not sadness) experienced in the morning predicted later occurrence of dependent stressors, while neither emotion predicted independent stressors (Sahl, Cohen, & Dasch, 2009). Another daily diary study found temporal relationships between interpersonal behaviors related to anxious attachment, reassurance seeking, and dependency on following day romantic conflict in a sample of undergraduate women (Eberhart & Hammen, 2009). This research suggests that people with SAD are likely to perceive daily social events (even some positive ones) as distressing.

Daily stress generation may be particularly relevant for SAD given the interpersonal dysfunction reported by most sufferers. When anxious, people with SAD are more likely to engage in safety behaviors or interpersonal styles, like unassertiveness, conflict avoidance, restriction of emotional expression, and interpersonal dependency (Davila & Beck, 2002). These behaviors aim to protect them from negative evaluation, but they paradoxically make people with high social anxiety less likeable to their interaction partners and even produce discomfort in confederates (Alden & Bieling, 1998; Alden & Taylor, 2004). Not only do these interpersonal styles aggravate relationships with friends, romantic partners, and family, but they also have been shown to mediate the relationship between social anxiety and social stress (Davila & Beck, 2002). In effect, what people with SAD do to avoid negative evaluation may actually increase relationship dysfunction, reinforcing their social anxiety symptoms and low self-esteem. This cycle may contribute to generation of stressful social events as a consequence of heightened negative emotion experiences.

The Present Study

The present study used daily diary methodology to capture day-to-day fluctuations in affect, self-esteem, and social events in people with and without SAD. This approach is useful for studying the impact of frequently occurring stressors (Stone & Shiffman, 2002), while minimizing problems associated with biased recall (Tourangeau, Rips, & Rasinski, 2000). Daily diaries allow us to use statistical analyses that simultaneously estimate between- and within-person effects, and the oscillations from one day to the next allow us to measure spillover effects of affect and events (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003). The temporal sequencing of events and reactions allow us to more strongly infer direction of influence. Given the possible differences in sensitivity to both negative and positive social events in people with SAD (Kashdan, Weeks, & Savostyanova, 2011), we investigated the temporal processes associated with both types of events.

People with SAD may differ in how social stressors influence their emotional and self-evaluative experiences in several ways. First—consistent with a stress sensitivity model—we hypothesized that participants with SAD would be more sensitive to negative social events in the form of heightened negative affect and lowered self-esteem on the day of the event; we also expected them to respond to positive events with less heightened positive affect and less heightened self-esteem on the day of the event compared to healthy controls. Notably, prior research also suggested the possibility that some positive events may be associated with heightened negative affect and possibly lowered self-esteem. Second, we hypothesized that participants with SAD would experience greater prospective fluctuations in daily emotions and self-esteem following social stressors, i.e., spillover of reactions to the following day. Third—consistent with a stress generation model—we expected that participants with SAD would experience more frequent negative social events and less frequent positive social events; we also expected them to evaluate negative social events as having greater importance and positive events as having less importance compared to the healthy control group. Fourth, we hypothesized that the SAD group would also experience prospective increases in negative social events (and decreases in positive social events) following days of increased negative emotions. Evaluating these pathways may explain the mechanisms by which social fears are maintained. Given the wealth of literature on the relationship of depression to stress sensitivity and stress generation (Hammen, 2005; Liu & Alloy, 2010), as well as recent work demonstrating deficits in interpersonal functioning in other anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder; Erickson & Newman, 2007), we also sought to test the specificity of our results by controlling for these additional diagnoses in our models.

Method

Participants

Participants were 86 adults from the Northern Virginia community recruited through online advertisements and flyers on bulletin boards. Of these, 43 participants were diagnosed with generalized SAD, while 43 adults not meeting criteria for any psychological diagnosis composed our healthy control (HC) group. After excluding seven participants who provided less than three daily diary entries, the final sample (n = 79) included 40 participants diagnosed with SAD and 39 age- and gender-matched HC. The sample was 64.6% female with an average age of 28.9 (SD = 8.8), and diverse in terms of self-identified race/ethnicity (54.4% “Caucasian/White,” 19% “African-American/Black,” 12.7% “Hispanic/Latino,” 5.1% “Asian-American,” 8.9% “Other”). Groups did not differ on demographic variables (see Farmer & Kashdan, 2013 for details).

Procedure

Complete details of this procedure can be found in Kashdan et al. (2013). Briefly, potential participants underwent initial screening by phone with trained research assistants. During the first face-to-face appointment (N = 122), participants completed trait questionnaires, participated in a thorough semi-structured clinical interview, and (qualified participants) learned how to complete online end-of-day questionnaires (and additional experience sampling data not used for these analyses) for the 14 days following the baseline assessment. Participants were asked to complete entries daily between 6:00 P.M. of the day in question and 11:59 A.M. on the next day, preferably as close to bedtime or waking as convenient to minimize memory bias. To maximize compliance, 1) we used brief measures, 2) we used an incentive-based payment structure (minimum payment of $165 up to $215 with regular, timely entries), 3) entries were date- and time-stamped, and 4) researchers sent reminder messages several days into data collection. At the end of data collection, participants returned to the laboratory for debriefing.

Measures

Diagnostic status

Participants’ diagnoses of SAD, MDD, and other Axis I disorders were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/NP; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002), conducted by doctoral-level clinical psychology students and supervised by a clinical psychologist. The SCID has previously demonstrated good interrater and test-retest agreement (Zanarini et al., 2000). In our study, 45 of the videotaped interviews were randomly chosen to be evaluated by a second coder, and inter-rater agreement was good (Kappa = .87). Additionally, we administered the SAD module of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM–IV: Lifetime Version (Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994) to determine SAD subtype. Generalized SAD had to be the primary or most severe diagnosis if other comorbid psychiatric conditions were present. Participants with comorbid substance dependence, psychotic symptoms, or active suicidal ideation were excluded from experience-sampling assessments due to risk and validity concerns. Only participants with no Axis I diagnoses were included in the HC group.

Daily emotions

Each evening, participants described the degree to which they experienced various emotions over the course of the day. Using a 5-point Likert-scale, participants rated five positive emotion items (e.g., joyful, enthusiastic) and five negative affect items (e.g., sad, angry) from 1 (very slightly/not at all) to 5 (extremely) to indicate “how well each adjective described your mood today.” The items were selected from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1994) and reflected brief adjective sets used in prior daily diary studies (e.g., Nezlek & Kuppens, 2008). We evaluated the reliability of the scales using three-level unconditional models (i.e., 5 emotions nested within the 14 days, nested within the 79 participants), where the reliability of the Level 1 intercept is essentially a Cronbach’s alpha (α) adjusted for differences between days and people (see Nezlek, 2007). Since reliability was very good for positive (α = .89) and negative (α = .81) emotion items, we created daily sum scores for each participant.

Daily self-esteem

Participants described their self-esteem on the day in question by responding to two items: “I felt I had good qualities” and “I felt satisfied with myself.” They rated their experiences on a 7-point scale from 1 (very uncharacteristic of me today) to 7 (very characteristic of me today). This measure was adapted from prior experience-sampling research (e.g., Nezlek & Plesko, 2001). Since our sample demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = .74), calculated as described above, we summed the item scores to create a daily self-esteem score for each end-of-day entry. Notably, the sample size for analyses involving self-esteem was 78 participants due to missing data (only on self-esteem) for one HC participant.

Daily social events

We also asked participants to describe the social events they experienced over the course of the day in question using the Daily Events Survey (DES; Butler, Hokanson, & Flynn, 1994); only items pertaining to social events were used for this study. Participants were asked to “describe the events that occurred to you today” with 9 specified positive social events (e.g., receiving a compliment, spending pleasant time in a social setting), and 9 specified negative social events (e.g., having an argument, being criticized), as well as one “Other” positive and negative event item that allowed participants to describe events not specified. All 20 items were assessed on a 6 point scale where 0 (did not occur) represented lack of exposure and 1 (occurred, and not meaningful) to 5 (occurred, and very meaningful) represented exposure with varying levels of importance. Although we calculated day-level reliability of positive (α = .64) and negative (α = .56) events, we did not expect these constructs to be internally consistent, given that they were essentially behavioral recordings (Stone, Kessler, & Haythomthwatte, 1991). Notably, prior research has similarly categorized positive and negative social events from the DES and reported good psychometric properties (e.g., Kashdan & Steger, 2006; Nezlek, 2002).

We calculated frequency of events by counting the number of positive or negative events the participant rated > 0 for each end-of-day entry. We also averaged importance ratings to create a total positive event score and a negative event score for that day, and we calculated the average importance rating for each participant for all events they rated > 0. Unless specified (Hypothesis 1), we present here the analyses for the frequency scores to avoid confounding interpretation biases with exposure to positive and negative events.1 To address possible buffering effects of positive and negative events, we calculated an interaction term of the daily event frequency scores centered around each participant’s mean score (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Compliance was acceptable, with an average of 87.1% of end-of-day entries (n = 963) completed within the requested time window (M = 12.1 entries per participant, SD = 3.67) and differences in compliance did not differ by diagnostic group (see Farmer & Kashdan, 2013). Based on previously published analyses (Farmer & Kashdan, 2013), the SAD group on average reported higher levels of negative emotions and lower levels of positive emotions and self-esteem over the two-week period (ds > 1.3).

Overview of Analyses

Given our inherently nested data (days within people), we used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to test our hypotheses. Despite efforts to encourage regular questionnaire completion, missing entries are the norm in daily diary research (13% in our study). Since multilevel modeling is appropriate if data are missing at random (Fitzmaurice, Laird, & Ware, 2004), we confirmed that missing data were not predicted by any of our predictor or outcome variables. Furthermore, we conducted analyses with full maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors, which uses all available data to inform within- and between- person level parameters and their standard errors (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

Multilevel models were constructed with separate Level 1 and Level 2 equations using HLM 6.08 software (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2004). Level 1 regression equations were specified to model fluctuation in the daily measures over time. Predictors at this level were centered around each participant’s average over the two weeks (see Nezlek, 2007). Level 2 equations were specified to model individual differences in Level 1 parameters as a function of diagnostic status which was contrast coded (e.g., SAD, MDD).

Descriptive Statistics

We first examined unconditional models to determine the proportion of variance explained by between-persons factors in our outcome variables. Our variables demonstrated considerable within-persons (σ2) and between-persons (τ) variability in our daily measures: positive emotions (σ2 = 8.67, τ = 15.32), negative emotions (σ2 = 8.47, τ = 5.84), self-esteem (σ2 = 4.15, τ = 6.62), positive event frequency (σ2 = 4.05, τ = 3.46), and negative event frequency (σ2 = 1.85, τ = 1.35). Thus, random effects were retained in subsequent HLM analyses. Notably, within-person variance was greater than between-person variance for all variables except positive emotions, highlighting the importance of studying these constructs as dynamic, fluctuating daily states. For an effect size, we calculated the percentage of within-person or between-person variance explained over the null model as appropriate, which approximates an R2 statistic in multiple linear regression analyses (Snijders & Bosker, 1994).

Temporal Process Analyses

Following Wickham and Knee’s (2013) recommendations, we addressed same-day (concurrent) and next-day (lagged) well-being sequelae of social events. We investigated concurrent effects by regressing the current day’s outcomes on the current day’s social events.2 Lagged effects were investigated simultaneously by regressing the current day’s outcome on the prior day’s events. This allowed us to examine the unique associations of well-being on a particular day with the same day’s events (concurrent at time T) and the prior day’s events (lagged at T–1). For each analysis, we accounted for expected autocorrelation of the outcome measure on adjacent days by including the prior day’s outcome (i.e., emotion or self-esteem), since people’s experiences at one point in time are likely to be more similar on days closer in proximity. This autocorrelation slope is a direct operationalization of emotional inertia (Kuppens, Allen, & Sheeber, 2010); by controlling it, we would be examining prospective fluctuations in experiences as a consequence of changes in events.

Additionally, we investigated potential interactions between concurrent and lagged events. Events that occur on one day can change how an individual reacts to events that occur on the following day. For example, an argument with a spouse on one day has the potential to change a person’s interpretation of (and thus reaction to) criticism from a boss on the following day. Negative social events on the previous day may have a potentiated sensitization effect, magnifying the association between today’s negative events and emotions. Alternatively, they may have an attenuated sensitization effect, where they dampen emotional responsiveness to today’s negative events (e.g., “It’s just another person criticizing me”). It is also possible for the previous day’s positive events to have a magnifying or dampening effect on today’s negative events. Thus, we investigated all two-way Concurrent × Lagged interaction effects between positive and negative events. The Level 1 model was as follows:

in which the outcome yij is the outcome for person j on day i, β0j represents the intercept for that person, β1j represents the degree to which a person’s level of the outcome measure on the previous day (T–1) predicts their current level of the outcome regardless of events (i.e., autocorrelation). β2j, β3j, and β4j represent the concurrent (same-day) relationships between events (positive, negative, and their interaction, respectively) with the outcome; β5j, β6j, and β7j are the lagged effects, testing the strength of the relationships between events one day before (T–1) and each day’s well-being (yij). Predictors were centered on each participant’s mean (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002); thus, their coefficients represent the relationships between deviations from the person’s mean event scores and short-term deviations in the outcome from the mean. To investigate possible sensitization or attenuation effects of previous days’ events on the associations of outcomes with same-day events, we included all two-way event interactions (β8j through β11j). For example, β10j represents the interaction of the previous day’s positive events and current day’s negative events on today’s well-being. Temporal processes in positive emotions, negative emotions, and self-esteem were examined in separate models. SAD was included as a Level 2 predictor of the intercept and all slopes. For a conservative approach, all predictors were estimated with random slopes.

Hypothesis 1: Does SAD Moderate the Effects of Concurrent Social Events on Well-Being?

We hypothesized that participants with SAD would experience greater sensitivity to same-day social stressors. Table 1 lists the results of the stress sensitivity temporal process models, which explained 43.4%, 46.4%, and 39.9% of the within-person variability in positive emotions, negative emotions, and self-esteem, respectively.3 For positive and negative emotions, we found a significant autocorrelation (inertia) effect of the previous day’s emotion level on the current day’s emotions, controlling for events occurring on those days (ps < .01). Consistent with previous research, we also found significant within-day associations between concurrent social events (positive and negative) and all three well-being outcome variables (i.e., positive emotions, negative emotions, and self-esteem; ps < .001).

Table 1.

Temporal Analysis of Relationships Between Social Events and Daily Well-being

| Coefficient | Negative Emotions | Positive Emotions | Self-esteem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 8.12 (.25)*** | 13.74 (.37)*** | 9.49 (.25)*** |

| × SAD | 1.32 (.25)*** | −2.39 (.37)*** | −1.39 (.25)*** |

| Outcome(T-1) | .12 (.04)** | .16 (.04)*** | .12 (.04)** |

| × SAD | −.02 (.04) | −.01 (.04) | −.06 (.04) |

| NegEvents(T) | .53 (.09)*** | −.37 (.09)*** | −.27 (.07)*** |

| × SAD | .28 (.09)** | .18 (.09)* | −.02 (.07) |

| PosEvents(T) | −.31 (.06)*** | .49 (.06)*** | .17 (.04)*** |

| × SAD | −.04 (.06) | .03 (.06) | .02 (.04) |

| NegEvents(T)× PosEvents(T) | −.10 (.05)* | .04 (.06) | .02 (.03) |

| × SAD | .00 (.05) | .03 (.06) | .01 (.03) |

| NegEvents(T-1) | −.02 (.09) | .16 (.08)* | .02 (.05) |

| × SAD | .04 (.09) | .11 (.08) | .03 (.05) |

| PosEvents(T-1) | .06 (.04) | −.08 (.05) | −.06 (.04) |

| × SAD | −.04 (.04) | .05 (.05) | .07 (.04) |

| NegEvents(T-1)× PosEvents(T-1) | −.00 (.05) | .05 (.04) | .03 (.03) |

| × SAD | .04 (.05) | −.02 (.04) | −.03 (.03) |

| NegEvents(T-1)× NegEvents(T) | −.06 (.06) | −.06 (.06) | −.08 (.04)† |

| × SAD | −.06 (.06) | .14 (.06)* | .10 (.04)* |

| PosEvents(T-1)× PosEvents(T) | −.02 (.02) | .04 (.03) | .02 (.02) |

| × SAD | −.02 (.02) | −.01 (.03) | −.01 (.02) |

| NegEvents(T-1)× PosEvents(T) | −.06 (.05) | .13 (.06)* | .06 (.03) |

| × SAD | −.03 (.05) | −.05 (.06) | −.03 (.03) |

| PosEvents(T-1)× NegEvents(T) | .04 (.04) | −.00 (.06) | .07 (.04) |

| × SAD | −.07 (.04) | −.09 (.06) | .02 (.04) |

Note.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .07.

Random coefficients from temporal process analyses are presented with standard errors in parentheses. Significant moderation effects of SAD diagnosis are bolded.

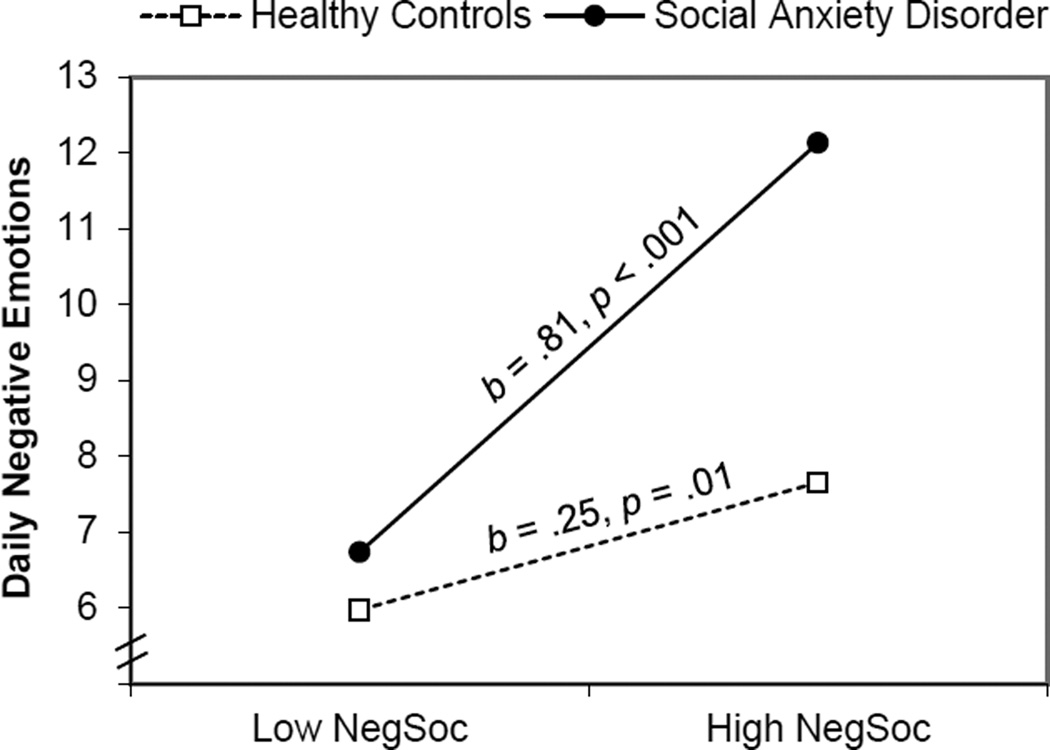

A diagnosis of SAD significantly moderated the relationship between negative events and negative emotions on the same day (t = 3.17, p = .003). Figure 2 depicts this interaction effect (using Shacham, 2009), where participants with SAD were significantly more reactive to negative events (b = .81, p < .001) than the HC group (b = .25, p = .013). We also found a significant interaction effect of Concurrent Negative Events × SAD on positive emotions (t = 2.05, p = .044), which suggested that participants with SAD did not experience as much decrease in positive emotions in reaction to negative events (b = −.19, p = .085) compared to the HC participants (b = −.54, p < .001). These results partially supported our hypothesis that participants with SAD would have greater sensitivity to same-day negative social events. Notably, negative social events were related to decreased self-esteem for participants (t = −3.62, p = .001), and positive events predictably decreased negative emotions (t = −5.50, p < .001), increased positive emotions (t = 8.13, p < .001), and increased self-esteem (t = 3.72, p = .001) for that day—but these effects were not moderated by SAD diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Social Anxiety Disorder Moderates the Relationship Between Concurrent Negative Social Events and Negative Emotions

Notes. Simple slopes for each diagnostic group were plotted at −1 SD (low) and +1 SD (high) of same-day negative social events centered within-person. NegSoc = negative social events.

We also found a significant Concurrent Negative Event × Concurrent Positive Event interaction effect on same-day negative emotions across all participants (t = −1.99, p = .050), but this effect was not moderated by SAD diagnosis. Simple slopes of this interaction effect suggested that positive events serve a protective effect on the relationship between negative events and negative emotions, such that when participants experienced more positive events (one SD above the mean), the relationship between negative events and negative emotions was moderately weaker (b = .33, p = .023) compared to days with less positive events (b = .73, p < .001).

Hypothesis 2: Does SAD Moderate Prospective Effects of Social Events on Well-Being?

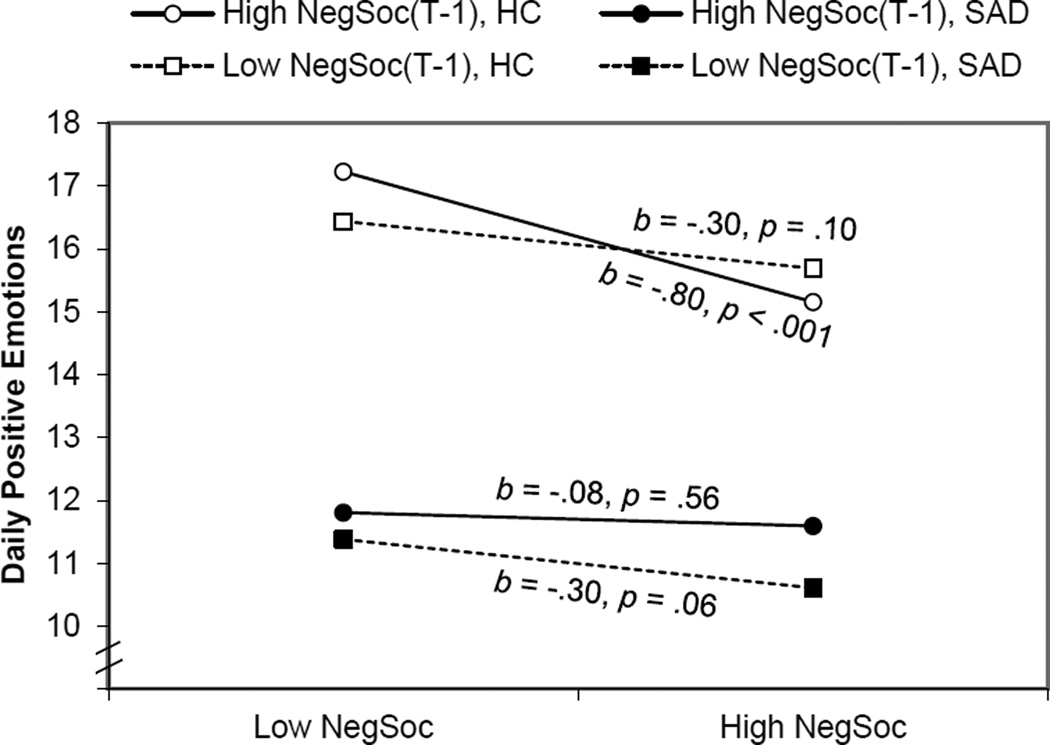

We hypothesized that participants with SAD would experience longer-lasting effects of social stressors on their well-being. We tested this analysis both with the lagged effects (unique contribution of prior day’s events on the current day’s outcome) and with interaction effects of Lagged × Concurrent events to test sensitization and attenuation effects. The results partially supported our hypothesis. We did not find SAD to moderate the effects of lagged events on current day negative emotions. We did find a significant interactive effect of SAD × Lagged Negative Events × Concurrent Negative Events on positive emotions (t = 2.52, p = .014). As depicted in Figure 3, among HCs, on days after participants experienced distressing social events, they were more sensitive to the occurrence of negative events compared to times when the prior day had a lower negative event score. In other words, they demonstrated potentiated sensitization to negative events from previous day’s negative event experiences. In contrast, the SAD group was similarly reactive to concurrent days’ negative events regardless of the previous day’s events. In other words, HCs’ positive emotions were dampened only when negative events occurred for the second day in a row, whereas the SAD group’s sensitivity did not significantly vary in relation to the prior day’s events.

Figure 3.

Three-way Interaction Between Diagnosis, Concurrent Negative Social Events, and Lagged Negative Social Events on Positive Emotions

Notes. Simple slopes for diagnostic groups were plotted −1 SD (low) and +1 SD (high) of same-day negative social events with separate lines for low and high prior day negative social events. HC = healthy controls; NegSoc = negative social events; SAD = social anxiety disorder.

We also found a significant interactive effect of SAD × Lagged Negative Events × Concurrent Negative Events on self-esteem (t = 2.36, p = .021). The pattern of effects was similar to that for positive emotions (Figure 3). Among HCs, self-esteem was more reactive to the occurrence of same-day negative events on days after they experienced more negative events (b = −.48, p < .001) compared to less negative events (b = −.01, p = .922). The self-esteem of the SAD group was similarly reactive to concurrent day’s negative events regardless of the previous day’s negative events (b = −.27, p = .010 vs. b = −.32, p = .022). In sum, these analyses suggest that participants with SAD were less variable in their sensitivity to negative social events compared to the HC group, which displayed potentiated sensitivity to subsequent days of negative events.4

Are Stress Sensitivity Effects Due to Depression?

Given the considerable comorbidity between SAD and MDD, as well as SAD and other anxiety disorders (Merikangas & Angst, 1995), we also sought to establish the specificity of our findings to SAD. Thus, we ran additional analyses including the presence of MDD diagnosis and presence of an additional anxiety diagnosis (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder) as additional predictors in each Level 2 equation.5 Our results with regard to SAD were similar with minor changes in the degree of significance. Specifically, controlling for MDD and anxiety disorders other than SAD, all significant SAD interactions remained statistically significant (p < .05) except for one—the interaction of Concurrent Negative Events × SAD on negative emotions (p = .184). Notably, controlling for MDD and other anxiety disorders separately, the effect remained at least at a trend level, with p-values of .011 and .087, respectively. These results suggest that our findings are not better explained by the SAD group’s comorbid conditions.

Hypothesis 3: Does SAD Predict the Occurrence and Importance of Daily Social Events?

HLM was used to test our third hypothesis that participants with SAD would report higher frequency of daily negative social events (and lower frequency of daily positive social events), as well as that the importance of events would also differ between groups. We used means-as-outcomes models (see Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) where we added SAD (coded −1 and 1) as a Level 2 predictor of the intercept.

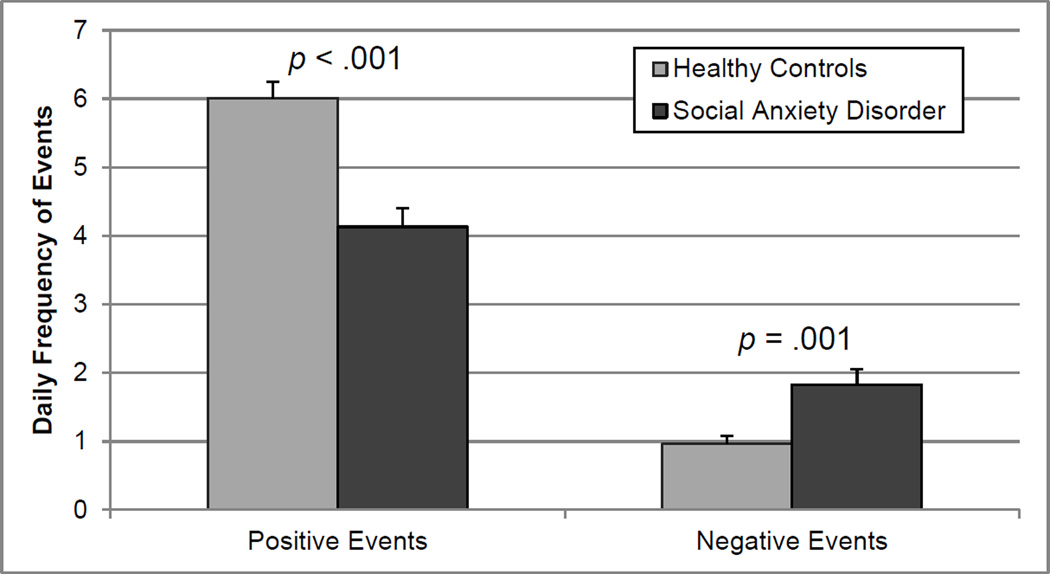

Consistent with predictions, the SAD group had significantly higher negative event scores (taking into account occurrence and importance) in their daily lives (β = 1.02, SE = .30, t = 3.39, p < .001, R2 = .27), and lower positive event scores in their daily lives (β = −3.37, SE = .67, t = −5.07, p < .001, R2 = .13). Furthermore, this represented not only a difference in subjective importance of events, as actual frequency of negative events was higher in participants with SAD (β = 0.43, SE = .13, t = 3.40, p = .001, R2 = .13); positive events occurred less frequently in participants with SAD (β = −0.94, SE = .19, t = −4.94, p < .001, R2 = .25). Figure 1 represents the frequency of events by group, with means and standard errors estimated from multilevel models. Notably, contrary to our expectations, groups did not differ in their average importance rating of a negative event when it occurred (β = 2.02, SE = .06, t = 1.10, p = .28, R2 < .01). However, participants with SAD did rate the importance of individual positive events on average lower than the HC group (M = 2.45, SE = 0.10 vs. M = 2.85, SE = 0.07; t = −3.15, p = .003, R2 = .11). In tests of specificity, all SAD effects remained significant (ps < .01) when controlling for MDD and other anxiety diagnoses.

Figure 1.

Social Anxiety Disorder Predicts Frequency of Daily Positive and Negative Social Events

Note. This figure represents average daily frequency of positive and negative events by group, estimated from multilevel models, with standard error bars.

Hypothesis 4: Is SAD Associated with Prospective Daily Stress Generation?

With evidence of stress generation in participants with SAD with regard to occurrence of daily social stress, we evaluated whether negative emotions prospectively contribute to interpersonal difficulties in people with SAD. Multilevel models were identical to those above with emotions replacing events as predictors. We conducted separate models predicting positive and negative social events, and accounted for an autocorrelation of events on adjacent days (e.g., being criticized on one day is more likely to be followed by criticism on the next day for the same reason). These models explained 50.4% and 35.8.9% of within-person variance in negative social events and positive social events, respectively. Adding SAD to the stress generation models only explained an additional 5.2% of between-persons variance in negative social events (but 20.8% of between person variance in positive social events) beyond the Level 1 predictors.

Outcomes of the temporal analyses predicting daily social events are summarized in Table 2. Positive events had significant carryover form one day do the next (t = 2.31, p = .024), while negative events had the opposite effect, being less likely on consecutive days (t = −2.30, p = .024). This latter effect was moderated by SAD; simple slopes determined that the effect was driven by the HC group (b = −0.17, p = .002), with no significant rebound from negative events for the SAD group (b = −0.00, p = .992).

Table 2.

Temporal Analysis of Relationships Between Daily Emotions and Daily Social Events

| Coefficient | Negative Events | Positive Events |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.26 (.14)*** | 4.90 (.21)*** |

| × SAD | .33 (.14)* | −0.89 (.21)*** |

| Outcome (T-1) | −.08 (.04)* | .11 (.04)* |

| × SAD | .08 (.04)* | −.04 (.04) |

| NegEmotions(T) | .14 (.03)*** | −.13 (.03)*** |

| × SAD | −.00 (.03) | .12 (.03)*** |

| PosEmotions(T) | −.01 (.02) | .20 (.03)*** |

| × SAD | .05 (.02) | .06 (.03) |

| NegEmotions (T)× PosEmotions (T) | .00 (.01) | −.02 (.01)* |

| × SAD | −.00 (.01) | .02 (.01)* |

| NegEmotions (T-1) | .07 (.03) | −.06 (.04) |

| × SAD | −.10 (.03)** | .07 (.04) |

| PosEmotions (T-1) | .04 (.02) | .04 (.03) |

| × SAD | −.01 (.02) | .00 (.03) |

| NegEmotions (T-1)× PosEmotions (T-1) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) |

| × SAD | −.01 (.01) | .01 (.01) |

| NegEmotions (T-1)× NegEmotions(T) | .00 (.02) | .01 (.01) |

| × SAD | .01 (.02) | .01 (.01) |

| PosEvents(T-1)× PosEmotions (T) | .01 (.01) | .02 (.01) |

| × SAD | .00 (.01) | −.00 (.01) |

| NegEmotions (T-1)× PosEmotions (T) | .00 (.01) | .00 (.01) |

| × SAD | .01 (.01) | .00 (.01) |

| PosEmotions (T-1)× NegEmotions (T) | .01 (.01) | .03 (.01)* |

| × SAD | .00 (.01) | −.04 (.01) |

Note. Random coefficients from temporal process analyses are presented with standard errors in parentheses. Significant moderation effects of SAD diagnosis are bolded. Residual within-person (σ2) and between-person (τ) variance is listed for each model.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Addressing the possibility that negative emotions may contribute to more negative social events prospectively, we examined the interaction effects of SAD and lagged effects. Although concurrent effects were not of interest for this study, we included them to examine Lagged × Concurrent interactions. We found a significant SAD × Lagged Negative Emotions effect for negative events (t = −3.11, p = .003). Simple slopes revealed that, for the HC group, more negative emotions on the prior day predicted more negative social interactions on a particular day (b = .17, p < .001). For the SAD group, lagged negative emotions were unrelated to negative social events (b = −0.03, p = .556). This result is contrary to our prospective stress generation hypothesis, instead suggesting that people with SAD had similar (high) levels of social stress regardless of day-to-day negative emotions.

With regard to daily positive social events, SAD did not moderate any lagged effects or interactions of lagged and concurrent effects. Notably, we did find a significant Lagged Positive Emotion × Current Negative Emotion effect (t = 2.45, p = .017)—not moderated by SAD. Simple slopes indicated that when participants experienced less positive emotions than usual on a prior day, there was an indirect relationship between their current day’s negative emotions and positive events (b = −0.22, p < .001), but not when they experienced more positive emotions than usual on the prior day (b = −.03, p = .433). Overall, we did not find support for greater prospective stress generation (neither increases of negative events nor decreases of positive events) related to prior day’s emotions for participants with SAD.

Discussion

In this study, we examined how people with SAD respond to social events in their daily lives. We looked at the extent to which positive and negative social events affected participants immediately (concurrent effects) and on the following day (lagged effects), and accounted for the likelihood that events experienced on one day influence their reactions to events on the following day. Compared to healthy adults, we found that participants with SAD exhibited greater stress sensitivity in their emotional reactions to same-day negative social events. Furthermore, the SAD participants demonstrated more rigid reactions to stressful social events across days (i.e., demonstrating consistently high sensitivity). Consistent with a stress generation model, we also found participants with SAD reported more frequent negative social events, as well as less frequent and meaningful positive social events in their daily lives. However, we did not find evidence for participants with SAD experiencing more social stressors on days following more intense negative emotion experiences; in fact, we found the opposite effect such that participants with SAD displayed less prospective stress generation. Our findings suggest that people with SAD experience heightened stress sensitivity and stress generation, but these effects appear to be limited to concurrent experiences, as their experiences appear to be less influenced by contextual factors like recent emotional and social events.

Stress sensitivity has been studied as a vulnerability factor for a number of psychiatric disorders. Our findings add to this understanding by demonstrating dysfunctional patterns of reactions to negative social events in a sample of adults with SAD and carefully screened HCs (using a validated clinical interview). Similar to other disorders, our participants with SAD experienced greater same-day negative emotion reactivity to negative social events. It is likely that positive emotion reactivity was less strong in the SAD group due to overall lower levels of positive emotions across days, such that decreases would be limited by a floor effect. Notably, over half of our SAD group met criteria for at least one secondary psychiatric diagnosis, raising the possibility that our findings could have been driven by symptoms of another diagnosis. Our findings were relatively unchanged when we accounted for depression or other anxiety diagnoses, but there is also significant overlap between SAD and other disorders (e.g., substance use disorders). Stress sensitivity may be a transdiagnostic feature shared among commonly occurring disorders. This is supported by findings of stress sensitivity associated with the serotonin transporter gene, which has been associated with several mood and anxiety disorders (Gunthert et al., 2007). Yet, equally important to uncovering transdiagnostic features of psychopathology and developing universal treatments for emotional problems (Barlow, Allen, & Choate, 2004) is the discovery of disorder-specific phenomena.

There are several reasons to believe SAD makes people particularly vulnerable to daily social stressors. First, stress sensitivity in people with SAD may be related to biological vulnerabilities, such as differential responses of the sympathetic nervous system (e.g., Yoon & Joormann, 2011). Second, cognitive models of SAD (e.g., Clark & Wells, 1995) argue that biased interpretations, excess attention to threat-related stimuli, and augmented perceived threat of social situations are common in SAD (Clark & McManus, 2002); thus, cognitive processes may intensify negative emotions, as well as self-focused thoughts that influence self-esteem. Third, recent SAD research has highlighted dysfunctional emotion regulation in people with SAD (Campbell-Sills & Barlow, 2007; Farmer & Kashdan, 2012; Goldin et al., 2009). Since people with SAD often doubt their ability to cope with stressful events, they expend significant energy on attempts to minimize distress and rejection including avoidance of situations, emotional experiences, and thoughts (e.g., Kashdan, Morina, & Priebe, 2009; Werner, Goldin, Ball, Heimberg, & Gross, 2011). Because trying to suppress experiences is cognitively taxing and generally ineffective for managing emotions (Richards & Gross, 1999), people with SAD may be more likely to perceive situations as stressful and feel more negatively.

The present study complements and extends the growing body of literature on daily stress sensitivity. Stressors and emotions do not occur in a vacuum but rather are influenced by recent experiences and influence subsequent experiences. To expand our understanding of day-to-day stress sensitivity in people with emotional difficulties, we tested for lagged effects (previous day’s predictors), concurrent effects (same day’s predictors), and their interaction (lagged × concurrent) to capture dynamic relationships between daily social events and well-being. Contrary to our initial expectations, the SAD group did not demonstrate a more lasting impact of negative social events on their negative emotions. A possible explanation for this is that participants with SAD may have been more likely to avoid potentially stressful situations in the aftermath of negative social events. Recent evidence suggests that people with SAD overuse not only avoidance of situations as an emotion regulation strategy, but also make efforts to avoid and suppress unpleasant emotions (e.g., Turk, Heimberg, Luterek, Mennin, & Fresco, 2005). Reliance on these strategies may have mitigated the possible spillover of negative emotions from one day to the next.

Compared to the SAD group, HC participants displayed more potentiated sensitization to negative events from the previous day’s stressors. Specifically, both positive emotions and self-esteem were more impacted when HC participants experienced high social stress after a prior day of high social stress. In contrast, the SAD group displayed similar (high) sensitivity across days, suggesting rigid, inflexible responding to stressors. Research on psychological flexibility suggests that being able to adapt to situational demands, i.e., to be able to choose behavioral and emotional responses from a wide repertoire in a way that is appropriate to one’s context, is important to psychological and physical health (Aldao, 2013; Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010). Our results indicate that the HC group demonstrated greater emotion regulation flexibility by reacting to events differently depending on the context of the previous day’s experiences. Our findings suggest that people with SAD may be so reactive to current stressors that they demonstrate a degree of insensitivity to context beyond their immediate (present day) experiences. This finding is consistent with other recent evidence of psychological inflexibility in SAD. Studies on emotion regulation have found that people with SAD tend to suppress both negative and positive emotions (Eisner, Johnson, & Carver, 2009; Werner et al., 2011), suggesting that they over-rely on this strategy even when it may have detrimental consequences for their well-being. Notably, such differences in stress sensitivity across time would not have been possible to capture with a within-day analytic approach.

We should highlight that participants with SAD did not exhibit more intense self-esteem reactivity to negative social events. One of the most dominant models of SAD (Clark & Wells, 1995) theorizes that a core feature of the condition is self-esteem that is contingent on social experiences, such that people with SAD are likely to experience low self-esteem following situations that evoke social threat. In our sample, both SAD and HC participants displayed similar self-esteem reactivity to social events (increasing in the context of positive events and decreasing in the context of negative events). It is possible that the events sampled in our study did not tap situations where participants experienced significant social threat or anxiety. It is also possible that, given the SAD group’s lower mean levels of self-esteem, they had a smaller range to drop on the self-esteem measure on days characterized by negative social events. Additionally, shifts in self-esteem may have been too transient to be captured by end-of-day ratings. Future studies can ask follow-up questions about specific negative social events to gauge perceived threat or other cognitive variables that help understand the relationship of social threat to self-esteem reactivity.

These findings build on prior research on stress sensitivity in SAD that focused almost exclusively on laboratory stress tasks (e.g., Yoon & Joormann, 2011) and retrospective accounts on global self-report measures (e.g., Bandelow et al., 2004). To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine daily stress sensitivity in adults diagnosed with SAD, adding novel understanding to the phenomenology of SAD by highlighting a possible mechanism for the persistent maintenance of SAD symptoms.

In addressing a stress generation hypothesis, our finding that participants with SAD reported more stressful negative social events, and less frequent and meaningful positive social events is consistent with experience sampling investigations on the daily lives of youth with SAD (e.g., Beidel et al., 1999). Our participants with SAD reported nearly twice as many negative events and 30% fewer positive events. This difference in exposure suggests that people with SAD are not only missing possible rewarding social opportunities but also are encountering situations most people would find somewhat distressing at a higher frequency, supporting the possible role of stress generation in this population. The contribution of both stress sensitivity and stress generation processes to SAD may help explain the particular chronicity of this disorder (Merikangas & Angst, 1995). Importantly, our findings were not better accounted for by comorbid depression or other anxiety disorders.

It is possible that people with SAD may not differ in actual experiences but perceive more negative social events due to interpretation or memory biases (see Stopa & Clark, 2000). For example, the exact same interaction may have led a healthy control to report occurrence of a positive interaction and an individual with SAD to report occurrence of a stressful event laden with criticism or rejection. Notably, the SAD and HC groups rated individual negative events at similar average levels of meaningfulness, suggesting the SAD group did not place more importance on individual social stressors when they occurred. However, the SAD group did rate positive events as less meaningful than the HC group, which provides additional evidence to the growing body of evidence showing people with SAD to experience a broad range of positivity deficits (Kashdan et al., 2011). Our research is unable to disentangle whether memory biases played a role in our findings, but we can conclude that participants with SAD perceived more social stress in their daily lives.

Cognitive-behavioral models of SAD (Heimberg et al., 2010) suggest that when people with SAD encounter anxiety during social interactions, they use ineffective emotion regulation strategies that often make them appear disinterested or cold. Thus, there is some reason to suspect negative emotions would predict negative social events prospectively for the SAD group. Our data did not support a prospective stress generation hypothesis. Instead, participants in the HC group experienced greater increases in negative events on days following high negative emotions, while the SAD group experienced similar frequencies of events regardless of prior day emotions. These results may reflect a tendency for participants in the HC group to seek out more social interactions to repair poor mood (increasing likelihood of stressful interactions), consistent with people’s motivation to seek social connections to fulfill a need for belonging following rejection (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). In contrast, the SAD group appears to have similar exposure to negative events irrespective of their day-to-day emotional experiences. In fact, whereas the HC group experienced a decrease in negative event exposure following stressful social event days, the SAD group did not experience this rebound. This further supports the possibility that people with SAD may not respond to their experiences day-to-day in way that may benefit their social relationships or mood, possibly due to a rigid reliance on behavioral avoidance instead of making efforts to increase social interactions as a strategy to manage negative mood.

Our research had several limitations worth mentioning. Any method asking participants to self-report and aggregate their social and emotional experiences over any length of time is likely to incur memory biases. We took precautions (e.g., date- and time-stamping entries) to maximize ecological validity (Affleck, Zautra, Tennen, & Armeli, 1999). In the future, researchers may consider more frequent reporting to capture stressors that occur in smaller time windows to reduce memory bias and allow for more nuanced examinations of stress sensitivity patterns within days. To minimize participant burden, we only asked participants about a subset of potential positive and negative social events. Future research may allow participants to self-report positive or negative social experiences on an event-contingent basis to allow for more personally meaningful event entry and description. Another limitation of our study is that missing data restricted the number of observations that could be used in temporal process analyses. Future researchers may consider ways to maximize data compliance, particularly for subsequent days, either by shortening data collection periods, making data entries less time-consuming, or increasing ease of access (e.g., smartphone applications).

Importantly, the present data cannot tell us why the SAD group had more negative social events. Future research examining motivations and attempts at social interactions, as well as their outcomes, would help researchers understand what an actual typical day looks like for someone with SAD. Are they making similar attempts at positive social interactions but having less success? Alternatively, are they only engaging in absolutely necessary interactions that have more likelihood for unpleasantness?

Our findings highlight several possible implications for clinical practice and research. We found that people with SAD experience stronger negative emotion reactivity and more rigid reactivity of positive emotions and self-esteem to same-day negative social events. These findings highlight the need for clinicians who work with people with SAD to help them develop more effective, flexible emotion regulation skills (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010). Additionally, emerging neuroimaging evidence suggests that mindfulness-based stress reduction not only improves SAD symptoms but also emotion regulation ability and reductions in physiological reactivity (Goldin & Gross, 2010). Future studies that incorporate pre- and post- treatment experience sampling will help determine the role of daily stress sensitivity in SAD as a risk factor, an associated symptom that improves with treatment, or a consequence of chronic social fears that maintains following recovery.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R21-MH073937) and the Center for the Advancement of Well-Being at George Mason University to TBK and the National Institutes of Drug Abuse and Mental Health (F31-DA029390) to ASF. We also want to thank Patrick McKnight, Ph.D., and Anastasia Kitsantas, Ph.D., the committee members of the doctoral dissertation by ASF.

Footnotes

It is worth noting that our findings are not limited to the use of frequency scores. We also conducted analyses by summing social event importance ratings to create a total positive event score and a negative event score for that day. These secondary analyses are important because without them, there is an assumption that all events are perceived to be equally meaningful. Notably, our results were similar when we substituted these composite scores in our models. In fact, the magnitude of significant SAD effects reported in the paper are even greater when using daily composite scores instead of frequency counts for life events. Detailed results are available upon request.

Since temporal process analyses required data from adjacent days, these models were based on 754 entries across the 79 people due to missing data.

Adding SAD diagnosis to the model explained an additional 35.3%, 29.3%, and 29.5% of the between person variance in positive emotions, negative emotions, and self-esteem beyond a temporal model with only Level 1 predictors.

Other noteworthy effects included participants overall reporting more positive emotions on days following more negative social events (t = 1.99, p = .050); this likely reflects a rebound effect after the significant decreases in positive emotions participants generally experienced in response to same-day negative events (t = −4.25, p < .001). We also found a significant interaction effect of Lagged Negative Events × Concurrent Positive Events for positive emotions (t = 2.29, p = .025). Participants were more reactive (i.e., potentiated sensitivity) to same-day positive events on days after they experienced more distressing negative events compared to days after they experienced less distressing negative events than average (b = .66, p < .001 vs. b = .32, p = .002). These effects were not moderated by SAD diagnosis.

Given our inclusion criteria, only the SAD group could have MDD or an additional anxiety disorder as an additional diagnosis.

Contributor Information

Antonina S. Farmer, Department of Psychology, Randolph-Macon College

Todd B. Kashdan, Department of Psychology, George Mason University

References

- Affleck G, Zautra A, Tennen H, Armeli S. Multilevel daily process designs for consulting and clinical psychology: A preface for the perplexed. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:746–754. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A. The future of emotion regulation research capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(2):155–172. doi: 10.1177/1745691612459518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alden LE, Bieling P. Interpersonal consequences of the pursuit of safety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:53–64. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alden LE, Taylor CT. Interpersonal processes in social phobia. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24(7):857–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alden LE, Wallace ST. Social phobia and social appraisal in successful and unsuccessful social interactions. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:497–505. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amin N, Foa EB, Coles ME. Negative interpretation bias in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:945–957. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Richardt S, Kertz S, Eberhart NK. Cognitive vulnerability, stress generation, and anxiety: Symptom clusters and gender differences. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2012;5(1):50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow PDB, Torrente AC, Wedekind DD, Broocks PDA, Hajak PDG, Rüther PDE. Early traumatic life events, parental rearing styles, family history of mental disorders, and birth risk factors in patients with social anxiety disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2004;254(6):397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0521-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35(2):205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM, Morris TL. Psychopathology of childhood social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(6):643–650. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Schilling EA. Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(5):808–818. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Schilling EA. Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality. 1991;59(3):355–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozovich F, Heimberg RG. An analysis of post-event processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(6):891–903. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Hokanson JE, Flynn HA. A comparison of self-esteem lability and low trait self-esteem as vulnerability factors for depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:166–177. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Barlow DH. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2007. Incorporating emotion regulation into conceptualizations and treatments of anxiety and mood disorders; pp. 542–559. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, McManus F. Information processing in social phobia. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(1):92–100. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Wells A. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. A cognitive model of social phobia; pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly NP, Eberhart NK, Hammen CL, Brennan PA. Specificity of stress generation: A comparison of adolescents with depressive, anxiety, and comorbid diagnoses. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2010;3(4):368–379. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2010.3.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R. Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1987;175:526–536. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Beck JG. Is social anxiety associated with impairment in close relationships? A preliminary investigation. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33(3):427–446. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM–IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge CS, Heimberg RG, Nyman D, O’Rien GT. Daily heterosocial interactions of high and low socially anxious college students: A diary study. Behavior Therapy. 1987;18(1):90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart NK, Hammen CL. Interpersonal Predictors of Stress Generation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35(5):544–556. doi: 10.1177/0146167208329857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner LR, Johnson SL, Carver CS. Positive affect regulation in anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23(5):645–649. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson TM, Newman MG. Interpersonal and emotional processes in generalized anxiety disorder analogues during social interaction tasks. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AS, Kashdan TB. Social anxiety and emotion regulation in daily life: Spillover effects on positive and negative social events. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2012;41:152–162. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2012.666561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AS, Kashdan TB. Affective and self-esteem instability in the daily lives of people with social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013 doi: 10.1177/2167702613495200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion. 2010;10(1):83–91. doi: 10.1037/a0018441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Manber T, Hakimi S, Canli T, Gross JJ. Neural bases of social anxiety disorder: Emotional reactivity and cognitive regulation during social and physical threat. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):170–180. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66(11):1351–1361. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthert KC, Conner TS, Armeli S, Tennen H, Covault J, Kranzler HR. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and anxiety reactivity in daily life: A daily process approach to gene-environment interaction. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69(8):762–768. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318157ad42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1(1):293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Brozovich FA, Rapee RM. A cognitive behavioral model of social anxiety disorder: Update and extension. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, editors. Social Anxiety: Clinical, Developmental, and Social Perspective. 2nd ed. New York: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 395–422. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2007;36:193–209. doi: 10.1080/16506070701421313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Wingate LR, Gencoz T, Gencoz F. Stress generation in depression: Three studies on its resilience, possible mechanism, and symptom specificity. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24(2):236–253. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Development. 1987;58:1459–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Morina N, Priebe S. Post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and depression in survivors of the Kosovo War: Experiential avoidance as a contributor to distress and quality of life. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Steger MF. Expanding the topography of social anxiety: An experience-sampling assessment of positive emotions, positive events, and emotion suppression. Psychological Science. 2006;17:120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Weeks JW, Savostyanova AA. Whether, how, and when social anxiety shapes positive experiences and events: a self-regulatory framework and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:786–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Allen NB, Sheeber LB. Emotional inertia and psychological maladjustment. Psychological Science. 2010;21(7):984–991. doi: 10.1177/0956797610372634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, Alloy LB. Stress generation in depression: A systematic review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future study. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(5):582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K, Angst J. Comorbidity and social phobia: Evidence from clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic studies. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1995;244(6):297–303. doi: 10.1007/BF02190407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Peeters F, Havermans R, Nicolson NA, DeVries MW, Delespaul P, Van Os J. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis and affective disorder: an experience sampling study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;107(2):124–131. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. Day-to-day relationships between self-awareness, daily events, and anxiety. Journal of Personality. 2002;70(2):249–276. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. A multilevel framework for understanding relationships among traits, states, situations and behaviours. European Journal of Personality. 2007;21:789–810. [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB, Kuppens P. Regulating positive and negative emotions in daily life. Journal of Personality. 2008;76(3):561–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB, Plesko RM. Day-to-day relationships among self-concept clarity, self-esteem, daily events, and mood. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(2):201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters F, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J, Delespaul P, deVries M. Effects of daily events on mood states in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(2):203–211. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]