Abstract

Neurogenesis persists throughout life in the neurogenic regions of the mature mammalian brain, and this response is enhanced after traumatic brain injury (TBI). In the hippocampus, adult neurogenesis plays an important role in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory functions and is thought to contribute to the spontaneous cognitive recovery observed after TBI. Utilizing an antimitotic agent, arabinofuranosyl cytidine (Ara-C), the current study investigated the direct association of injury-induced hippocampal neurogenesis with cognitive recovery. In this study, adult rats received a moderate lateral fluid percussion injury followed by a 7-day intraventricular infusion of 2% Ara-C or vehicle. To examine the effect of Ara-C on cell proliferation, animals received intraperitoneal injections of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU), to label dividing cells, and were sacrificed at 7 days after injury. Brain sections were immunostained for BrdU or doublecortin (DCX), and the total number of BrdU+ or DCX+ cells in the hippocampus was quantified. To examine the outcome of inhibiting the injury-induced cell proliferative response on cognitive recovery, animals were assessed on Morris water maze (MWM) tasks at 21–25 or 56–60 days postinjury. We found that a 7-day infusion of Ara-C significantly reduced the total number of BrdU+ and DCX+ cells in the dentate gyrus (DG) in both hemispheres. Moreover, inhibition of the injury-induced cell proliferative response in the DG completely abolished the innate cognitive recovery on MWM performance at 56–60 days postinjury. These results support the causal relationship of injury-induced hippocampal neurogenesis on cognitive functional recovery and suggest the importance of this endogenous repair mechanism on restoration of hippocampal function.

Key words: : Ara-C, cognition, hippocampus, Morris water maze, neurogenesis, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the leading cause of death and disability of persons under the age of 45 in the United States, affecting over 1.4 million individuals each year. The hippocampus, a region responsible for learning and memory functions, is particularly vulnerable to TBI. Hippocampal injury-associated learning and memory deficits are often the hallmarks of brain trauma and are the most enduring and devastating consequences after TBI.1 Despite the high frequency and severity of TBI, relatively little is known about the biological basis of the cognitive deficits associated with insults to the brain or the innate repair processes in the brain. Consequently, no cure is available for the enduring deficits caused by TBI. After TBI, there is a limited spontaneous recovery in cognitive functions. The exact mechanisms underlying this recovery are unknown. Recent findings of the existence of continuous neurogenesis in the hippocampus in the mature mammalian brain and its biological roles in the hippocampal-dependent learning and memory functions have indicated the involvement of this cellular event in cognitive recovery after brain injury.

In the hippocampus of the normal brain, the newly generated granule cells in the adult dentate gyrus (DG) can become functional neurons, which display passive membrane properties, and can generate action potentials and functional synaptic inputs similar to the mature DG neurons.2,3 Evidence has also shown that adult hippocampal neurogenesis is involved in learning and memory functions.4,5 For example, mouse strains with genetically low levels of neurogenesis perform poorly on learning tasks, when compared to those with higher levels of baseline neurogenesis.6,7 Conversely, physical activity stimulates a robust increase in the generation of new neurons and subsequently enhances spatial learning and long-term potentiation.8,9 Additionally, diminished hippocampal neurogenesis, as observed after the administration of antimitotic drugs, or by irradiation exposure or genetic ablation, has been associated with worse performance on hippocampus-dependent trace eyeblink conditioning,10 contextual fear conditioning,11,12 active place avoidance task,13 and long-term spatial memory function tests.14,15 Collectively, these studies provide compelling evidence that adult-born neurons in the hippocampus play a critical role in many important hippocampal-dependent functions in the normal brain.

In the injured brain, we and others have shown a significantly enhanced neurogenic response in the hippocampus after TBI.2,16–18 Our lab and others have also found that injury-induced newly generated dentate granule neurons integrate extensively into the existing hippocampal circuitry,19,20 and this integration is associated with the time course of innate cognitive recovery observed after brain injury.20 Further, studies have shown that enhancement of TBI-induced hippocampal neurogenesis with growth factors significantly improved cognitive recovery in injured animals.21–24 Collectively, these results have provided evidence that there is a link between hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive recovery after injury and revealed the therapeutic potential of augmenting the endogenous repair response for treating TBI. To ascertain the direct connection between injury-induced hippocampal neurogenesis to post-TBI cognitive recovery, in this study we abolished the TBI-induced cell proliferative response with a focal administration of antimitotic agent, arabinofuranosyl cytidine (Ara-C). We then examined the effect of disrupting injury-induced cell proliferation on the recovery of spatial learning and memory functions in the injured animals.

Methods

Animals

A total of 93 male 3- to 4-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN), weighing approximately 300 g, were included in this study. Animals were housed in the animal facility, with a 12-h light/dark cycle, and water and food provided ad libitum. All procedures were approved by our institutional animal care and use committee.

Surgical procedures

Animals were subjected to a moderate lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) following our published protocol.20,21 Briefly, adult rats were anesthetized in a plexiglass chamber with 5% isofluorane, intubated and ventilated with 2% isofluorane in a gas mixture (30% O2 and 70% N2), and fixed on a stereotaxic frame. After a mid-line incision and skull exposure, a 4.9-mm craniotomy was trephinized on the left parietal bone halfway between the lambda and bregma sutures. A Leur-Loc syringe hub made from a 20-gauge needle was affixed to the craniotomy site with cyanoacrylate and further cemented with dental acrylic to the skull, at which point the anesthesia was switched off. Once the animal regained consciousness, as measured by toe and tail reflexes, the Leur-Loc fitting filled with saline was connected to a precalibrated fluid percussion device and a 2.2±0.04 atm fluid pulse was administered. Sham animals went through the same surgical procedure without receiving the fluid pulse. After injury, the Leur-Loc fitting was removed; the animal was returned to the surgical table and righting time was assessed. Fifteen minutes after injury, the animal was reanesthetized and an Alzet brain infusion cannula (Brain Infusion Kit II; DURECT, Cupertino, CA) was stereotactically implanted into the posterior lateral ventricle ipsilateral to the injury site (coordinates: anteroposterior –1.0 mm, mediolateral 1.4 mm, and 3.5 mm beneath the pial surface). The infusion cannula was connected to an Alzet miniosmotic pump (model 1007D; DURECT), which was placed subcutaneously on the back of the neck. An Alzet miniosmotic pump containing either 2% Ara-C or vehicle (artificial cerebrospinal fluid) was primed at 37°C water bath for 2 h before use. The solution was infused for 7 consecutive days at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/h. A total of 25 injured and 21 sham rats received 2% AraC infusion, whereas 21 injured and 21 sham animals received a vehicle infusion. Another group of 5 rats received 2% Ara-C infusion 7 days prior to LFPI.

Beginning at 48 h after injury, all animals received daily single intraperitoneal injections of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU; 50 mg/kg) for 5 consecutive days. The infusion cannula and Alzet miniosmotic pump were removed at 7 days postinjury.

Tissue preparation

Animals were sacrificed at 7, 28, or 62 days postinjury, depending on the experimental group. Animals were deeply anesthetized with an overdose of isofluorane inhalation and transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Brains were dissected and postfixed in 4% PFA for 48 h at 4°C and then cut coronally at 60 μm with a vibratome throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the brain. Sections were collected in 24-well plates filled with PBS plus 0.01% sodium azide and stored at 4°C until use.

Immunohistochemistry

In order to assess the number of BrdU-labeled cells for animals sacrificed at 7 days postinjury (N=5 for each group), every fourth sections were processed for BrdU immunostaining. BrdU staining was performed following our previously published protocol.20 Briefly, sections were washed with PBS, DNA was denatured with 50% formamide for 60 min at 65°C followed by a rinse in 2×saline-sodium citrate buffer, and then incubated with 2 N of HCl for 30 min at 37°C. After denaturing, sections were washed with PBS and endogenous peroxidase was blocked using 3% H2O2. Following an overnight serum blocking with 5% normal horse serum in PBS, sections were incubated with rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) preabsorbed mouse anti-BrdU antibody (1:200; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) in PBST (PBS with 0.4% Triton) plus 5% normal horse serum at 4°C for 48 h with agitation on the shaker. After rinsing with PBST, sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4°C and visualized with 5′5-diaminobenzidine. Sections were mounted on glass slides, lightly counterstained with 0.1% cresyl violet, and cover-slipped.

To assess the effect of Ara-C infusion on the generation of new neurons, another set of every fourth sections from sham animals sacrificed at 7 days postinjury were processed for doublecortin (DCX) immunostaining. In the DG, DCX labels actively divided transiently amplifying progenitor cells (type 2b cells), neuroblasts (type 3 cells), and immature neurons.25 The immunostaining procedure for DCX was similar to the BrdU immunostaining procedure described above, albeit omitting the denaturing steps. A goat anti-DCX (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and biotin-conjugated horse anti-goat IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) were used, followed by an ABC kit and DAB substrate.

Because BrdU was injected at 2–7 days postinjury, the number of BrdU+ cells present at a later time postinjury did not reflect cell proliferation at the time point when animals were sacrificed. To assess whether Ara-C has a long-term effect on cell proliferation in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and hippocampus, every fourth brain sections from animals that went through the Morris water maze (MWM) tests and were sacrificed at 62 days postinjury were immunostained for Ki67, a proliferation marker. The immunostaining procedure for Ki67 was similar to the BrdU immunostaining protocol described above, with the omission of the denaturing steps. A rabbit anti-Ki67 (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge MA) and biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used, followed by an ABC kit and DAB substrate.

Stereological quantification

A modified optical fractionator method was used to estimate the total number of BrdU-, DCX-, or Ki67-positive cells. This design-based stereological method, which is used to estimate cell numbers, has been widely used by our lab and previously described.22 Briefly, the region of interest (ROI) was outlined using a 4×objective. A 60×oil immersion objective was used for cell counting. To quantify the number of BrdU+, DCX+, or Ki67+ cells in the DG of the hippocampus, sections were examined with an Olympus Image System CAST program (Olympus, Fredericia, Demark). Ten sections spaced 240 μm apart spanning the DG (–2.56 to –5 mm of bregma) were examined by a “blinded” observer. In the DG, immunolabeled cells located in the subgranular zone (SGZ), a two-cell band between the granule cell layer (GCL) and the hilus,26 and in the GCL were counted together as the granular zone (GZ). Because the immunostained cells were scattered in the DG, we counted the total number of BrdU+, Ki67+, or DCX+ cells in the entire GZ and the hilus regions. A 60×oil immersion lens was used to focus through the thickness of each section, and, to avoid sampling error, cells from the upper- and lowermost focal planes were excluded from the count (optical dissector principle).27 To derive a cell number calculation, the sampling fraction (asf)=1, the disector height (h)=15, and the average section thickness (t) after immunostaining was 22 μm. With these parameters, the number of total cell counts (N) was estimated as N=ΣQ−·t/h·1/asf·1/ssf, where ssf was the section-sampling fraction (=0.25 in this study) and ΣQ− was the number of cells counted.

Morris water maze

The MWM was utilized to assess spatial cognition after TBI.1,28 All animals surviving beyond 7 days postinjury were tested. For the purpose of investigating the innate cognitive recovery after TBI, separate groups of animals were tested at 21–25 (N=8 for both sham and injury-vehicle groups; N=10 for both sham and injury-AraC groups) or 56–60 days postinjury (N=8 for both sham and injury-vehicle groups; N=10 for TBI-AraC group; N=6 for sham-AraC group) by a “blinded” observer. MWM testing was performed following our previously published protocol.20 In the MWM performance, goal latency and path length are equally sensitive measures.29 We used goal latency as the primary dependent variable. The probe trial was done at 24 h after the last day of the goal latency test. Path length (to reach the goal in the MWM) and swim speed were also analyzed. Preceding MWM testing, a visual platform test was performed to confirm that the visual system of the animal was not impaired. Briefly, animals were placed in the large circular tank (180-cm diameter by 45-cm height) containing opaque water. Water temperature was maintained at 24°C with a heater. Animals were allowed to swim freely to find the hidden goal platform (1 cm below the water surface) in order to escape from the water. Each animal was tested four times each day with a 5-min intertrial interval. For each trial, the animal was randomly placed at one of four starting positions (north, east, south, west). MWM performance was recorded using a computerized video tracking system (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). The latency to find the platform, total distance swum to reach the goal platform, and swim speed were calculated for each trial. Upon finding the platform, the rat was left there for 30 sec before being removed from the maze and placed in a warm cage to dry. Animals that did not find the platform after 120 sec were placed on the platform for 30 sec and then removed from the maze. During the probe trial, at 24 h after the last day of latency training, the platform was removed from the tank. The animal was placed in the quadrant where the platform was placed before facing the wall and given 60 sec to swim in the pool. Using the video tracking system, the time spent in the goal platform quadrant and the average proximity to the goal location were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The data generated were analyzed using SPSS software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). For cell quantification, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post-hoc Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) test or the Student's t-test with an applied Bonferroni's correction for multiple groups utilized, with p values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. For MWM data analysis, the data were analyzed using a split-plot ANOVA [Treatment×Day] comparing effect of group on goal latency. A Fisher's LSD test was performed to allow for pair-wise group contrasts. Swim speed was also analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) in all figures.

Results

Increasing evidence has been accumulated to show that adult hippocampal neurogenesis plays an important role in learning and memory functions, and this endogenous cell response is enhanced after TBI. This enhancement likely contributes to the innate cognitive recovery after brain trauma. We have previously demonstrated that the neurogenic regions of the brain display a TBI-enhanced cell proliferative response during the first week postinjury.2 In this study, to validate the direct link of the injury-enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis to the spontaneous cognitive recovery observed after TBI, we administrated the antimitotic agent, Ara-C, into the lateral ventricle for 7 days to specifically block injury-induced cell proliferation. Efficacy of Ara-C infusion on this injury-induced proliferative response was assessed and its effect on cognitive function was examined.

Righting response

To ensure that the injury severity was similar in all TBI animal groups, animals were randomly assigned to study groups and spontaneous postinjury righting response time was assessed. Righting time, which measures the length of suppression of the righting reflex, is a reflection of neuromotor damage and is generally regarded as an indicator of injury severity.29,30 The mean (SEM) duration (min) of suppression of righting response after injury was 14.19 (±0.88) for the vehicle-infused injured animal group, 13.88 (±0.89) for the Ara-C-infused injured animal group, and 12.55 (±1.28) for the animal group infused with Ara-C before injury. A t-test on these data indicated that the groups did not significantly differ with regard to duration of suppression of righting response, thus suggesting that all TBI groups received a similar severity of injury.

Intraventricular infusion of arabinofuranosyl cytidine eliminates traumatic brain injury–induced cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus

In a pilot study, we first tested the effectiveness of Ara-C on inhibiting cell proliferation at the concentration of 4% (w/v) or 2% (w/v). We found that an intraventricular infusion of Ara-C at both concentrations reduced the number of BrdU+ cells in the neurogenic regions. However, the 4% Ara-C infusion caused significant animal weight loss, whereas the 2% Ara-C had no influence on body weight. Consequently, 2% Ara-C was used for the subsequent studies.

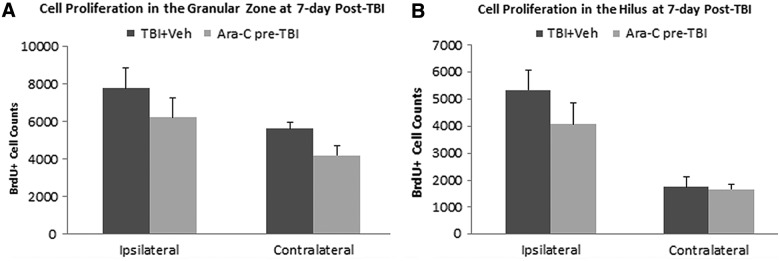

Because Ara-C was delivered focally to the ventricular system in a relative low concentration of 2%, animals did not present with any observable side effects, such as weight loss or infection. By using BrdU to label dividing cells in the DG of the hippocampus, we found that BrdU-labeled cells were clustered predominately in the SGZ and the inner third portion of the GCL. Moreover, levels of cell proliferation in vehicle-infused injured animals were elevated, as compared to sham animals (Fig. 1). After infusion of the mitogen inhibitor, Ara-C, sham animals did not show any changes; however, injured animals had fewer BrdU-labeled cells in the SGZ and GCL, as compared to vehicle-infused injured animals (Fig. 1). Unbiased stereological quantification analysis of subregions within the DG showed that in the GZ (including the SGZ and GCL), the total number of BrdU+ cells in vehicle-infused injured animals was significantly higher in both the ipsi- and contralateral hemispheres, as compared to the sham animals (Fig. 1A; p<0.01). After infusion of Ara-C, the total number of BrdU+ cells in Ara-C-infused injured animals was significantly reduced, compared to the vehicle-infused injured animals (Fig. 1A; p<0.05) and was at similar levels to sham animals in both the ipsi- and contralateral hemispheres. Sham animals with Ara-C infusion had a slight, but not significant, reduction in the number of BrdU+ cells, compared to the vehicle-infused sham animals (Fig. 1A). In the hilus region, increased cell proliferation was observed in the ipsilateral hemisphere of both injury groups, as compared to the sham (Fig. 1B; p<0.05). Moreover, animals that received Ara-C infusion did not display a reduced number of BrdU+ cells, as compared to vehicle-treated animals. In the sham groups, a slight increase of BrdU+ cells was observed in Ara-C-infused animals in both the ipsi- and contralateral hilus, although the difference did not reach significance (Fig. 1B). In the molecular layer of the DG, a similar level of BrdU+ cells was observed in both the vehicle and Ara-C groups (Fig. 1). These data suggest that a 7-day infusion of 2% Ara-C abolished TBI-induced cell proliferation primarily in the neurogenic regions of the SGZ and GCL in the DG, whereas injury-induced cell proliferation in the hilus region and the molecular layer of the DG was not affected.

FIG. 1.

Ara-C infusion eliminates injury-induced cell proliferation in the SGZ of the DG. Micrographs taken from BrdU-stained coronal sections in the ipsilateral DG from sham and injured animals receiving vehicle or Ara-C infusion. In sham vehicle-treated animal, a small number of BrdU+ cells were mostly located in the SGZ of the DG (arrows). In injured animal with vehicle infusion, there were many more BrdU+ cells in the SGZ (arrows) and the hilus. On the contrary, in animals with 2% Ara-C infusion for 7 days, BrdU+ cells in the SGZ were largely diminished, particularly in the injured animal. Ara-C infusion did not affect the number and distribution of BrdU+ cells in the hilus region and the molecular layer of the DG. Bar scale=300 μm. Graphs (A) and (B) show the quantitative analysis of cell proliferation in the DG. (A) In the GZ (SGZ and GCL combined), in both the ipsi- and contralateral sides, TBI vehicle-treated animals had a significantly higher number of BrdU-labeled cells than sham animals (**p<0.01) and injured animals with Ara-C infusion (#p<0.01). The level of BrdU+ cells in injured animals with Ara-C infusion was similar to sham vehicle animals. Among sham animals, the Ara-C infusion group had a lower number of BrdU+ cells, as compared to the vehicle group; however, the difference was not statistically significant. (B) In the hilus region, in the ipsilateral side, the number of BrdU+ cells was significantly higher in injured animals with vehicle or Ara-C infusion, as compared to sham vehicle animals (#p<0.01). No difference was found in the contralateral hilus region. In sham groups, Ara-C infusion had a higher number of BrdU+ cells in the hilus region, compared to the sham-vehicle groups; however, the difference was not statistically significant. Ara-C, arabinofuranosyl cytidine; BrdU, 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine; DG, dentate gyrus; GCL, granule cell layer; GZ, granular zone; SGZ, subgranular zone; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

Arabinofuranosyl cytidine infusion inhibits generation of doublecortin-positive cells

Given that most of the newly generated cells in the DG of the adult brain become granule neurons,20,31 we assessed the extent to which the generation of new neurons was affected by a 7-day intraventricular infusion of Ara-C in the DG using DCX labeling. Previous studies have reported that immature neurons in the DG are vulnerable to TBI and often undergo apoptosis.32,33 To avoid the complication of this TBI effect, we examined the outcome of Ara-C infusion on new neurons only in sham animals. To identify newly generated neurons, sequential hippocampal sections were processed for DCX staining and the total number of DCX+ cells in the ipsi- and contralateral DG were quantified. In the DG of vehicle-treated animals, DCX+ cells were densely distributed throughout the dorsal and rostral blades with cell bodies clustered in the SGZ and the inner third portion of the GCL whereas the dendrites extended to the molecular layer (Fig. 2A). In Ara-C-treated animals, much less DCX+ cells were observed in the DG, and the DCX+ cells were mostly scattered singly in both blades (Fig. 2B). Stereological quantification analysis revealed that the total number of DCX+ cells in the ipsi- and contralateral DG (including the SGZ and the GCL) of Ara-C-infused animals was approximately 56% and 66%, respectively, to that found in vehicle-infused animals (Fig. 2C; p<0.05). Similar changes were found in the subventricular zone, another primary neurogenic region in the brain (data not shown). These data suggest that Ara-C infusion mostly affects DCX-expressing actively dividing type 2b neural progenitor cells, type 3 neuroblast cells, and immature neurons in the neurogenic regions.

FIG. 2.

Ara-C infusion-abolished cells are mostly DCX+ cells in the DG. Micrographs were taken from coronal sections of sham animals with DCX staining in the ipsilateral DG. (A) In the vehicle-treated animal, DCX+ cells were distributed in both the upper and lower blades of the GZ with clustered cell bodies packed in the SGZ. (B) In the Ara-C-infused animals, there were much less DCX+ cells present in the DG and the remaining DCX+ cells were scattered singly in both blades. Bar scale=200 μm. (C) Stereological quantification analysis showed that Ara-C infusion significantly reduced the total number of DCX+ cells in both the ipsi- and contralateral side of DG, as compared to the vehicle infusion (*p<0.05). Ara-C, arabinofuranosyl cytidine; DCX, doublecortin; DG, dentate gyrus; GZ, granular zone; SGZ, subgranular zone; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

Arabinofuranosyl cytidine treatment does not have prolonged effect on cell proliferation inhibition

To test whether an intraventricular delivery of Ara-C only has transient effect of cell proliferation inhibition when it is on board, a group of naïve animals received a 2% Ara-C infusion for 7 days first. After removal of the infusion cannula and the pump, animals were then subjected to a moderate LFPI and received BrdU injection at 2–7 days post-TBI. Animals were sacrificed 2 h after the last BrdU injection, and the total number of BrdU+ cells was quantified. We found that a preinjury infusion of Ara-C did not affect injury-induced cell proliferation in the DG. Quantification analysis revealed that the animals that had an Ara-C treatment before injury had similar total numbers of BrdU+ cells in the GZ and the hilus regions in both the ipsi- and contralateral hemispheres as the injured animals with vehicle infusion (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Infusion of Ara-C preinjury does not affect TBI-induced cell proliferation in the DG. Stereological quantification analysis revealed that at 7 days postinjury, animals that received a 7-day intraventricular infusion of 2% Ara-C before TBI had a similar total number of BrdU+ cells in the GZ (SGZ and GCL combined; A) and the hilus regions (B) as the TBI vehicle-treated animals in both the ipsi- and contralateral sides. Ara-C, arabinofuranosyl cytidine; BrdU, 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine; DG, dentate gyrus; GCL, granule cell layer; GZ, granular zone; SGZ, subgranular zone; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

To examine whether Ara-C treatment has a prolonged effect on cell proliferation, which may affect cognitive performance, we assessed cell proliferation in animals that were sacrificed at 62 days postinjury (right after the cognitive functional tests) using the proliferation marker, Ki67. Ki67 is a cell-cycle–related nuclear protein that is expressed in all phases of the active cell cycle. At 62 days postinjury, the staining pattern of Ki67+ cells was similar in both sham and injured animals, regardless of treatment. As shown in Figure 4, clustered Ki67+ cells were predominately located in the SGZ, a pattern similar to BrdU staining in sham animals in Figure 1. Stereological quantification analysis revealed that the total number of Ki67+ cells in the ipsi- and contralateral GZ was slightly lower in Ara-C-treated animals in both the sham and injured groups; however, no statistical significant was found in the number of Ki67+ cells between the injured animals with vehicle or Ara-C infusion. The only group difference was found between the sham animals with vehicle group and the group of injured animals with Ara-C treatment in the ipsilateral GZ (Fig. 4A; p=0.05). In the hilus region, no significant difference was found between groups (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Ara-C infusion does not have a prolonged effect on cell proliferation inhibition. In micrographs taken from Ki67-stained coronal sections in the ipsilateral DG from sham and injured animals with vehicle or Ara-C infusion at 2 months postinjury, a similar pattern of Ki67 staining was observed (arrows). Bar scale=100 μm. (A and B) Graphs show stereological quantification analysis of the total number of Ki67+ cells. In both the GZ and the hilus regions, the total number of Ki67+ cells in animals with Ara-C infusion was slightly, but not significantly, lower than their matched vehicle groups in both the ipsi- and contralateral sites. The only significant group difference was found between the sham-vehicle and the TBI+Ara-C group in the ipsilateral GZ (*p=0.05). Ara-C, arabinofuranosyl cytidine; DG, dentate gyrus; GZ, granular zone; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

Collectively, the data from this pre-TBI Ara-C infusion study and the Ki67 study at 62 days postinjury suggest that Ara-C exerts its inhibition effect transiently and only when it is onboard.

Inhibition of injury-induced cell proliferation with arabinofuranosyl cytidine infusion impedes innate cognitive recovery after injury

Extensive studies in recent years have demonstrated that hippocampal neurogenesis is important for learning and memory functions.4,5 We have previously reported that moderate LFPI enhances hippocampal neurogenesis and that the time course of the innate cognitive recovery postinjury is correlated to the integration of newly generated neurons into existing neuronal networks within the hippocampus.20 To determine whether this injury-induced hippocampal neurogenesis plays a direct role in cognitive functional recovery after TBI, we evaluated the learning and memory functions of the injured animals after abolishing injury-induced cell proliferation. Animals were infused with a 2% Ara-C for 7 days postinjury to eliminate injury-induced cell proliferation, MWM performance was tested at 21–25 or 56–60 days postinjury in two separate groups.

To test whether inhibition of injury-induced cell proliferation had a detrimental effect on cognitive function, a group of animals was tested on WMW tasks at 21–25 days postinjury. Mean latency (s) to reach the platform at 21–24 days postinjury was used as a measure of cognitive function. Data were analyzed using a split-plot ANOVA (repeated-measures ANOVA, Group×Day). The results of the ANOVA revealed significant differences in Group effect (p<0.001) and Day×Group interaction (p<0.001) between groups. Post-hoc analysis revealed that injured animals in both vehicle- and Ara-C-infused groups had significantly longer latencies to reach the goal platform, compared to the sham animals treated with vehicle (Fig. 5A; p<0.05). There was no significant difference in the performance of Ara-C-treated sham animals, compared to vehicle-treated sham animals (p=0.538), or injured animals between vehicle- and Ara-C-infused groups (Fig. 5A). After the latency test, the probe trial was conducted at 24 h after the last day of the latency trial. Probe trial latency data and proximity data analysis showed that, compared to sham groups, injured animals in both vehicle and Ara-C groups stayed a shorter time within, and were further away from, the quadrant where the hidden platform was placed (Fig. 5B; p<0.01). In the injured groups, no difference was found between vehicle and Ara-C infusion. In sham animals, the group that received Ara-C infusion spent a shorter time in the goal quadrant, compared to the group with vehicle infusion (Fig. 5B; p<0.05). Collectively, the MWM data at 21–25 days suggested that injured animals have significant learning and memory deficits, as compared to sham animals, and Ara-C infusion does not further impact TBI-induced deficits. The probe trial data also indicated that Ara-C infusion can induce memory deficits in sham animals.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of injury-enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis with Ara-C infusion does not further exacerbate TBI-induced cognitive deficits at 21–25 days post-injury. (A) MWM goal latency test at 21–24 days postinjury; all groups showed improvement in the goal latency performance by the fourth day of training. Group comparison revealed that injured animals, either with vehicle or Ara-C infusion, had significantly longer goal latency, as compared to sham animals with vehicle or Ara-C infusion from the second test day onward (*p<0.01). No significant difference was found between sham vehicle and sham+Ara-C animals, or TBI+vehicle and TBI+Ara-C groups. (B) Probe trial following a 24-hour delay. Compared to sham+vehicle-infused animals, injured animals with vehicle or Ara-C infusion spent a significantly shorter time in the goal quadrant (**p<0.01). Sham animals with Ara-C infusion also spent a shorter time in the goal quadrant, as compared to sham+vehicle animals (*p<0.05). No difference was found between the two injured groups. Ara-C, arabinofuranosyl cytidine; MWM, Morris water maze; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

We previously reported that after a moderate LFPI, cognitive deficits lasted for several weeks and spontaneous recovery was observed at approximately 2 months postinjury, a time course corresponding to integration of injury-induced, newly generated dentate granule neurons to the existing neural circuitry.20 To confirm that this injury-induced neurogenesis plays a crucial role in the innate postinjury recovery, a separate group of animals underwent MWM tests at 56–60 days postinjury. The ANOVA test revealed significant differences in Group effect (p<0.001), but not in Day×Group interaction (p=0.74). Post-hoc analysis revealed that injured animals with Ara-C infusion had a significantly longer latency to reach the goal platform, whereas the vehicle-treated injury group performed similarly as sham animals (Fig. 6A; TBI-Ara-C vs. sham-vehicle, p<0.05; TBI-vehicle vs. sham-vehicle, p=0.26). The probe trial performed at 24 h after the last latency trial showed that injured animals with Ara-C infusion stayed a significantly shorter time in the goal quadrant, as compared to the injury-vehicle group or the sham groups (Fig. 6B; p<0.01). No difference was found between sham-vehicle and sham-Ara-C groups in both the latency and probe trials. Taken together, this finding suggests that inhibition of injury-induced cell proliferation with Ara-C treatment significantly disrupts innate recovery of hippocampal-dependent learning and memory functions after TBI.

FIG. 6.

Elimination of injury-induced neurogenesis with Ara-C infusion abolishes the innate cognitive recovery after TBI observed at 56–60 days postinjury. (A) MWM goal latency test at 56–60 days postinjury; all groups showed improvement in the goal latency performance through training. Group comparison revealed that injured animals with vehicle infusion performed similarly to sham groups. However, injured animals with Ara-C infusion had significantly longer goal latency, as compared to injured vehicle animals or sham groups (*p<0.01). (B) Probe trial following a 24-hour delay. Injured animals with Ara-C infusion spent a significantly shorter time in the goal quadrant, as compared to the injured vehicle group and two sham groups (*p<0.01). Among sham animals, the Ara-C infusion group did not show significant difference, as compared to the vehicle group, in both the goal latency and probe trial tests. Ara-C, arabinofuranosyl cytidine; MWM, Morris water maze; TBI, traumatic brain injury; Veh, vehicle.

Discussion

Our previous studies have found that TBI in the form of LFPI significantly enhances hippocampal neurogenesis, and this response is linked to the spontaneous cognitive recovery observed after injury.20 The current study demonstrated that inhibition of this injury-induced neurogenic response abolishes the innate cognitive recovery, thereby suggesting a causal relationship. Specifically, an intraventricular infusion of the mitogen-inhibitor, Ara-C, for 7 days immediately after TBI eliminated the injury-induced cell proliferative response in the DG of the hippocampus. The effect of Ara-C on cell proliferation inhibition was transient and was only present when it was onboard. Moreover, the cell type affected by Ara-C infusion was primarily the actively dividing DCX-positive cells. When cognitive function was assessed, we found that inhibition of injury-induced cell proliferation did not affect the performance of animals in the MWM tests at 21–25 days postinjury at the time points when injury-induced cognitive deficits were present. However, inhibition of injury-induced cell proliferation in the DG abolishes the innate cognitive recovery at 56–60 days postinjury at the time when recovery was observed in the injured vehicle-treated animals. Collectively, the results of the current study suggest that injury-induced cell proliferation in the neurogenic region of the hippocampus is directly associated with spontaneous cognitive recovery after TBI.

Following the discovery of persistent adult neurogenesis throughout life in the mature mammalian brain, the physiological roles and the importance of this adult neurogenesis on learning and memory functions have been studied intensively. Studies have shown that conditions that promote neurogenesis in the hippocampus (i.e., exposure to enriched environments, physical exercise, or growth factor treatment) can improve cognitive abilities.8,21,34 These studies have provided correlative evidence about the role of this adult hippocampal neurogenesis on hippocampal functions. Subsequent extensive studies have examined the causal relationship between neurogenesis and hippocampal function by inhibiting adult neurogenesis using varying types of approaches (i.e., brain irradiation, systemic or focal administration of antimitotic agents, and genetic ablation of dividing progenitor cells). These studies reported important roles for adult-generated dentate granule neurons on many types of hippocampal-dependent learning and memory tasks. These include trace eyeblink and fear conditioning,10,11 formation of contextual fear memory,12,35,36 long-term retention of spatial memory in the water maze task,15,37 object recognition task,37,38 and active place avoidance task.13 Moreover, targeted deletion of adult-generated dentate granule neurons at the maturation stage induced retrograde memory deficits in contextual fear, water maze, and visual discrimination memories.39 Although some variable and partially contradictory results have been reported from these studies owing to the methods used to knock down neurogenesis or animal species used or the nature of behavioral tasks, this growing body of data provide compelling evidence that adult hippocampal neurogenesis is directly involved in many aspects of hippocampal-dependent learning and memory functions.

Under many neuropathological conditions, such as TBI, stroke, and epilepsy, the degree of adult neurogenesis is significantly enhanced.40.41 This endogenous cell response may have functional significance by contributing to endogenous brain repair and regeneration. Indeed, previous studies from our lab have found that injury-induced newly generated dentate granule neurons in the hippocampus integrate into the hippocampal circuitry, and this process is closely related to the time course of the innate cognitive recovery observed after brain trauma.20 This suggests the importance of injury-induced hippocampal neurogenesis to the innate cognitive functional recovery. To confirm the causal relationship of injury-enhanced neurogenesis to functional recovery, we designed the current study. Our previous studies examined the time course of injury-induced cell proliferation in the DG and the SVZ. We found that TBI, in a form of moderate lateral fluid percussion, induced a significant cell proliferation in these regions during the first week after injury, with the peak of cell proliferation at 2 days postinjury, and by 2 weeks post-TBI, cell proliferation returned to the sham level.2 Thus, in the current study, we administered mitogen inhibitor Ara-C focally to the brain through intraventricular infusion for 7 days, which specifically blocked TBI-induced cell proliferative response, but maintained the baseline cell proliferation at the level similar to the sham control. We found that elimination of the injury-induced endogenous stem cell proliferative response completely abolished the innate hippocampal-dependent learning and memory functional recovery, as shown in the MWM performance at 56–60 days postinjury. These data validated the direct link of injury-induced endogenous neural stem cell response to the spontaneous cognitive functional recovery after TBI. Our result is also in agreement with a published study in a mice controlled cortical impact injury model using a genetic approach to ablate nestin+ neural stem cells in the neurogenic regions to examine the contribution of post-TBI hippocampal neurogenesis to spatial memory function.42 In this study, ganciclovir was delivered for 4 weeks, starting immediately after TBI, to allow ganciclovir-mediated ablation of nestin+ progenitor cells. The 4-week ganciclovir delivery reduced the number of DCX+ cells and nestin+ progenitor cells in the injured animals to the level lower than the sham control at 2 months after injury when behavior tests were carried out.42 Compared with this study, our strategy only ablated the TBI-induced new cells born in the first week after injury without affecting the ongoing baseline level of cell proliferation in the DG during the time when behavior tests were performed; thus, our study more specifically ascertained the causal relationship of injury-induced neurogenesis to the innate cognitive functional recovery. Our result is consistent with those described in a recently published mice stroke study examining the contribution of stroke-enhanced neurogenesis on poststroke cognitive recovery using a genetic approach to ablate nestin+ neural stem cells in the neurogenic regions, as mentioned above.43

To eliminate dividing cells, three strategies are often used, including irradiation, genetic manipulation, and antimitotic drugs. Each of these strategies has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, through lead shielding, irradiation can target selected ROIs to eliminate region-specific dividing cells. This spatially restricted exposure does not affect other organs or require surgical procedures and is a popular method in neurogenesis and cognitive function studies.12,14,15 However, irradiation causes prolonged effect on cell inhibition and can alter focal microvasculature, damage postmitotic cells, or induce inflammatory responses within the exposed tissue.44,45 Compared to irradiation, genetic manipulation with conditional transgenic targeting of selected cell populations, such as glial fibrillary acid protein–positive, nestin+, or DCX+ cells can be target-specific. However, there are also shortfalls with this method, such as lower than baseline and prolonged effect on cell proliferation inhibition,42 and treatments to induce gene expression can be complicated, with possible toxicity when given systemically or prolonged delivery when given locally.46,47 Moreover, genetic manipulation can only be done in mice, an animal model where strain differences largely affect baseline levels of neurogenesis and cognitive function.6 Additionally, there is a substantial difference in plasticity and functional contribution of adult-born new neurons between rat and mice; specifically, new neurons generated in the adult hippocampus in mice are less abundant, mature slower, and are less involved in behaviors, compared to new neurons generated in rats.48 Compared to irradiation and genetic manipulation, antimitotic drugs have a transient effect on dividing cells, affecting cells only from the time when the drug is delivered through the period of dose efficacy, as shown in the current study. Moreover, given that antimitotic drugs target primarily actively dividing cells, such as DCX+ cells in the current study, postmitotic cells, the quiescent or inactive neural stem cells, are largely unaffected when exposed to these drugs. However, caution must be taken when these drugs are administered systemically, given that this treatment has a global effect on organisms and cannot be restricted to a target region. This nonspecific targeting can be reduced or overcome with region-specific targeting through local delivery. In the current study, we used antimitotic agent Ara-C to eliminate injury-induced cell proliferation with focal delivery into the lateral ventricle. We also tested the optimal concentration in our pilot study. In the pilot study, we tested a 7-day infusion of 4% or 2% Ara-C on cell proliferation inhibition and general health of animals and found that the 4% Ara-C caused body-weight loss in the injured animals. Thus, the 2% Ara-C was used throughout the study. In our study, a 7-day infusion of 2% Ara-C sufficiently blocked injury-induced cell proliferation without affecting general heath of injured animals and causing detrimental effect on cognitive function given that it had shown no worsening in MWM performance at 21–25 days postinjury.

Ara-C is a chemotherapy agent that interferes with DNA synthesis. Ara-C is metabolized rapidly in the liver with an initial half-life of approximately 10 min after intravenous dosing followed by a secondary elimination half-life of 1–3 h.49 Owing to the fact that Ara-C has a transient effect on dividing cells, its cell inhibition action is reversible after withdrawal. This provides an advantage when a limited period of cell elimination is desirable, such as our study, where the period of injury-induced cell proliferation can be targeted. In our study, a group of animals received Ara-C infusion before TBI and this pre-TBI infusion did not affect TBI-induced cell proliferation. Using proliferation marker Ki67, we examined cell proliferation at 2 months after Ara-C infusion and did not observe a difference between animals with or without Ara-C treatment. Unlike other published studies with 14-day Ara-C infusion to maximally eliminate adult neurogenesis,50,51 our 7-day 2% Ara-C regime, given at the time period when injury-induced cell proliferation is observed, effectively eliminated only TBI-induced cell proliferative response without affecting the baseline level of cell proliferation. Thus, this Ara-C treatment is of advantage to testify the contribution of injury-enhanced neurogenesis to the innate cognitive recovery, compared to irradiation or the transgenic approach given that these two methods reduced the baseline level of cell proliferation and had a prolonged effect.44 One thing that needs to be mentioned is that Ara-C infusion also blocked injury-induced cell proliferation in the SVZ. Because the SVZ-generated cells are mostly destined to the olfactory bulb, and the MWM-based tasks do not depend on olfactory information,28 cells generated from the SVZ may not contribute to hippocampal-dependent cognitive function.

As noted in our study, BrdU+ cells were observed in the hilus and the molecular layer of the DG in the injured brains. Our previous studies have shown that BrdU+ cells in these areas were a mixture of blood-borne macrophages, reactive astrocytes, and activated microglia after TBI.16 These injury-activated cells were not significantly affected by Ara-C infusion, perhaps owing to differential sensitivity of different cell types to Ara-C. For example, a previous study found that infusion of Ara-C to the site of a focal injury can transiently affect the focal injury induced activation of NG2+ oligodendrocyte progenitor cells and CD11+ microglial cells, but not blood-borne macrophages and reactive astrocytes.52 Additionally, an early published study examining cerebral explants reported that Ara-C affected microglia cell proliferation, but not astrocytes proliferation.53 Further, in vitro studies have found that Ara-C can inhibit fibroblast proliferation, but not Schwann cells, and Ara-C is used for Schwann cell purification in culture.54,55 Nevertheless, it is not clear whether the BrdU+ cells in the hilus and the molecular layer after Ara-C infusion in the current study were blood-borne macrophages and reactive astrocytes. Further study using double-labeling of BrdU and varying cell-type–specific markers is needed to verity this assumption. Regardless, the effect of Ara-C focal infusion on cell proliferation inhibition on both neural stem cells and glial cells are transient, as shown in the current study and by other published studies.51,52

In summary, accumulating evidence has proved the importance of adult hippocampal neurogenesis to hippocampal-dependent learning and memory functions. The current study has added to this body of evidence and established the direct role of injury-induced neural stem cell response in the hippocampus in the spontaneous cognitive functional recovery after brain insults. With the understanding of the functional role of endogenous neurogenesis, augmenting or manipulating this response could be a promising avenue for researchers seeking to develop new therapies for brain repair and regeneration.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; grant nos.: NS055086 and NS078710; to D.S.). Microscopy work was performed at the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology Microscopy Facility, supported, in part, with funding from NIH-NINDS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke) center core grant 5P30NS047463.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Smith D.H., Okiyama K., Thomas M.J., Claussen B., and McIntosh T.K. (1991). Evaluation of memory dysfunction following experimental brain injury using the Morris water maze. J. Neurotrauma 8, 259–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun D., Colello R.J., Daugherty W.P., Kwon T.H., McGinn M.J., Harvey H.B., and Bullock M.R. (2005). Cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation in the dentate gyrus in juvenile and adult rats following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma, 22, 95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Praag H., Schinder A.F., Christie B.R., Toni N., Palmer T.D., and Gage F.H. (2002). Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature 415, 1030–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng W., Saxe M.D., Gallina I.S., and Gage F.H. (2009). Adult-born hippocampal dentate granule cells undergoing maturation modulate learning and memory in the brain. J. Neurosci. 29, 13532–13542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clelland C. D., Choi M., Romberg C., Clemenson G.D., Jr., Fragniere A., Tyers P., Jessberger S., Saksida L.M., Barker R.A., Gage F.H., and Bussey T.J. (2009). A functional role for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in spatial pattern separation. Science 325, 210–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kempermann G., Kuhn H.G., and Gage F.H. (1997). Genetic influence on neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of adult mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 10409–10414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kempermann G., Brandon E.P., and Gage F.H. (1998). Environmental stimulation of 129/SvJ mice causes increased cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Curr. Biol. 8, 939–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Praag H., Christie B.R., Sejnowski T.J., and Gage F.H. (1999). Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 13427–13431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Praag H., Kempermann G., and Gage F.H. (1999). Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 266–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shors T.J., Miesegaes G., Beylin A., Zhao M., Rydel T., and Gould E. (2001). Neurogenesis in the adult is involved in the formation of trace memories. Nature 410, 372–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shors T.J., Townsend D.A., Zhao M., Kozorovitskiy Y., and Gould E. (2002). Neurogenesis may relate to some but not all types of hippocampal-dependent learning. Hippocampus 12, 578–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxe M.D., Battaglia F., Wang J.W., Malleret G., David D.J., Monckton J.E., Garcia A.D., Sofroniew M.V., Kandel E.R., Santarelli L., Hen R., and Drew M.R. (2006). Ablation of hippocampal neurogenesis impairs contextual fear conditioning and synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 17501–17506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burghardt N.S., Park E.H., Hen R., and Fenton A.A. (2012). Adult-born hippocampal neurons promote cognitive flexibility in mice. Hippocampus 22, 1795–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rola R., Raber J., Rizk A., Otsuka S., VandenBerg S.R., Morhardt D.R., and Fike J.R. (2004). Radiation-induced impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis is associated with cognitive deficits in young mice. Exp. Neurol. 188, 316–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder J.S., Hong N.S., McDonald R.J., and Wojtowicz J.M. (2005). A role for adult neurogenesis in spatial long-term memory. Neuroscience 130, 843–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chirumamilla S., Sun D., Bullock M.R., and Colello R.J. (2002). Traumatic brain injury induced cell proliferation in the adult mammalian central nervous system. J. Neurotrauma 19, 693–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dash P.K., Mach S.A., and Moore A.N. (2001). Enhanced neurogenesis in the rodent hippocampus following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 63, 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao X., Enikolopov G., and Chen J. (2009). Moderate traumatic brain injury promotes proliferation of quiescent neural progenitors in the adult hippocampus. Exp. Neurol. 219, 516–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emery D.L., Fulp C.T., Saatman K.E., Schutz C., Neugebauer E., and McIntosh T.K. (2005). Newly born granule cells in the dentate gyrus rapidly extend axons into the hippocampal CA3 region following experimental brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 22, 978–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun D., McGinn M.J., Zhou Z., Harvey H.B., Bullock M.R., and Colello R.J. (2007). Anatomical integration of newly generated dentate granule neurons following traumatic brain injury in adult rats and its association to cognitive recovery. Exp. Neurol. 204, 264–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun D., Bullock M.R., McGinn M.J., Zhou Z., Altememi N., Hagood S., Hamm R., and Colello R.J. (2009). Basic fibroblast growth factor-enhanced neurogenesis contributes to cognitive recovery in rats following traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 216, 56–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun D., Bullock M.R., Altememi N., Zhou Z., Hagood S., Rolfe A., McGinn M.J., Hamm R., and Colello R.J. (2010). The effect of epidermal growth factor in the injured brain after trauma in rats. J. Neurotrauma 27, 923–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee C., and Agoston D.V. (2010). Vascular endothelial growth factor is involved in mediating increased de novo hippocampal neurogenesis in response to traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 27, 541–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thau-Zuchman O., Shohami E., Alexandrovich A.G., and Leker R.R. (2010). Vascular endothelial growth factor increases neurogenesis after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30, 1008–1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempermann G., Jessberger S., Steiner B., and Kronenberg G. (2004). Milestones of neuronal development in the adult hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 27, 447–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kempermann G., Gast D., Kronenberg G., Yamaguchi M., and Gage F.H. (2003). Early determination and long-term persistence of adult-generated new neurons in the hippocampus of mice. Development 130, 391–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coggeshall R.E., and Lekan H.A. (1996). Methods for determining numbers of cells and synapses: a case for more uniform standards of review. J. Comp. Neurol. 364, 6–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris R.G., Garrud P., Rawlins J.N., and O'Keefe J. (1982). Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature 297, 681–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamm R.J. (2001). Neurobehavioral assessment of outcome following traumatic brain injury in rats: an evaluation of selected measures. J. Neurotrauma 18, 1207–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morehead M., Bartus R.T., Dean R.L., Miotke J.A., Murphy S., Sall J., and Goldman H. (1994). Histopathologic consequences of moderate concussion in an animal model: correlations with duration of unconsciousness. J. Neurotrauma 11, 657–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cameron H.A., and McKay R.D. (2001). Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J. Comp. Neurol. 435, 406–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao X., Deng-Bryant Y., Cho W., Carrico K.M., Hall E.D., and Chen J. (2008). Selective death of newborn neurons in hippocampal dentate gyrus following moderate experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 86, 2258–2270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun D., McGinn M., Hankins J.E., Mays K.M., Rolfe A., and Colello R.J. (2013) Aging- and injury-related differential apoptotic response in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in rats following brain trauma. Front. Aging Neurosci. 5, 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kempermann G., Kuhn H.G., and Gage F.H. (1997). More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment. Nature 386, 493–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imayoshi I., Sakamoto M., Ohtsuka T., Takao K., Miyakawa T., Yamaguchi M., Mori K., Ikeda T., Itohara S., and Kageyama R. (2008). Roles of continuous neurogenesis in the structural and functional integrity of the adult forebrain. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 1153–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernandez-Rabaza V., Llorens-Martin M., Velazquez-Sanchez C., Ferragud A., Arcusa A., Gumus H.G., Gomez-Pinedo U., Perez-Villalba A., Rosello J., Trejo J.L., Barcia J.A., and Canales J.J. (2009). Inhibition of adult hippocampal neurogenesis disrupts contextual learning but spares spatial working memory, long-term conditional rule retention and spatial reversal. Neuroscience 159, 59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jessberger S., Clark R.E., Broadbent N.J., Clemenson G.D., Jr., Consiglio A., Lie D.C., Squire L.R., and Gage F.H. (2009). Dentate gyrus-specific knockdown of adult neurogenesis impairs spatial and object recognition memory in adult rats. Learn. Mem. 16, 147–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suárez-Pereira I., Canals S., and Carrión A.M. (2014). Adult newborn neurons are involved in learning acquisition and long-term memory formation: The distinct demands on temporal neurogenesis of different cognitive tasks. Hippocampus 25, 51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arruda-Carvalho M., Sakaguchi M., Akers K.G., Josselyn S.A., and Frankland P.W. (2011). Posttraining ablation of adult-generated neurons degrades previously acquired memories. J. Neurosci. 31, 15113–15127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kernie S.G., and Parent J.M. (2010). Forebrain neurogenesis after focal Ischemic and traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 37, 267–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parent J.M. (2008). Persistent hippocampal neurogenesis and epilepsy. Epilepsia 49, Suppl 5, 1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blaiss C.A., Yu T.S., Zhang G., Chen J., Dimchev G., Parada L.F., Powell C.M., and Kernie S.G. (2011). Temporally specified genetic ablation of neurogenesis impairs cognitive recovery after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. 31, 4906–4916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun C., Sun H., Wu S., Lee C.C., Akamatsu Y., Wang R.K., Kernie S.G., and Liu J. (2013). Conditional ablation of neuroprogenitor cells in adult mice impedes recovery of poststroke cognitive function and reduces synaptic connectivity in the perforant pathway. J. Neurosci. 33, 17314–17325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mizumatsu S., Monje M.L., Morhardt D.R., Rola R., Palmer T.D., and Fike J.R. (2003). Extreme sensitivity of adult neurogenesis to low doses of X-irradiation. Cancer Res. 63, 4021–4027 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Limoli C.L., Giedzinski E., Rola R., Otsuka S., Palmer T.D., and Fike J.R. (2004). Radiation response of neural precursor cells: linking cellular sensitivity to cell cycle checkpoints, apoptosis and oxidative stress. Radiat. Res. 161, 17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin K., Wang X., Xie L., Mao X.O., and Greenberg D.A. (2010). Transgenic ablation of doublecortin-expressing cells suppresses adult neurogenesis and worsens stroke outcome in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 7993–7998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singer B.H., Jutkiewicz E.M., Fuller C.L., Lichtenwalner R.J., Zhang H., Velander A.J., Li X., Gnegy M.E., Burant C.F., and Parent J.M. (2009). Conditional ablation and recovery of forebrain neurogenesis in the mouse. J. Comp. Neurol. 514, 567–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snyder J.S., Choe J.S., Clifford M.A., Jeurling S.I., Hurley P., Brown A., Kamhi J.F., and Cameron H.A. (2009). Adult-born hippocampal neurons are more numerous, faster maturing, and more involved in behavior in rats than in mice. J. Neurosci. 29, 14484–14495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamada A., Kawaguchi T., and Nakano M. (2002). Clinical pharmacokinetics of cytarabine formulations. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 41, 705–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lau B.W., Yau S.Y., Lee T.M., Ching Y.P., Tang S.W., and So K.F. (2009). Intracerebroventricular infusion of cytosine-arabinoside causes prepulse inhibition disruption. Neuroreport 20, 371–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y., Chopp M., Mahmood A., Meng Y., Qu C., and Xiong Y. (2012). Impact of inhibition of erythropoietin treatment-mediated neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus on restoration of spatial learning after traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 235, 336–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rhodes K.E., Moon L.D., and Fawcett J.W. (2003). Inhibiting cell proliferation during formation of the glial scar: effects on axon regeneration in the CNS. Neuroscience 120, 41–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oorschot D.E., and Jones D.G. (1989). Effect of cytosine arabinoside on rat cerebral explants: fibroblasts and reactive microglial cells as the primary cellular barrier to neurite growth. Neurosci. Lett. 102, 332–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Calderon-Martinez D., Garavito Z., Spinel C., and Hurtado H. (2002). Schwann cell-enriched cultures from adult human peripheral nerve: a technique combining short enzymatic dissociation and treatment with cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C). J. Neurosci. Methods 114, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei Y., Zhou J., Zheng Z., Wang A., Ao Q., Gong Y., and Zhang X. (2009). An improved method for isolating Schwann cells from postnatal rat sciatic nerves. Cell Tissue Res. 337, 361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]