Abstract

Immediate and lasting effects of music or second-language training were examined in early childhood using event-related potentials (ERPs). ERPs were recorded for French vowels and musical notes in a passive oddball paradigm in 36 four- to six-year-old children who received either French or music training. Following training, both groups showed enhanced late discriminative negativity (LDN) in their trained condition (music group–musical notes; French group–French vowels) and reduced LDN in the untrained condition. These changes reflect improved processing of relevant (trained) sounds, and an increased capacity to suppress irrelevant (untrained) sounds. After one year, training-induced brain changes persisted and new hemispheric changes appeared. Such results provide evidence for the lasting benefit of early intervention in young children.

Keywords: development, event-related potentials (ERP), late discriminative negativity (LDN), training, top-down control processing

Music and language are two cognitive domains that share many features and sensory-perceptual and cognitive networks. Although neural network differences exist between music and language processing (Zatorre et al., 2002), they both use the same acoustic cues (i.e., pitch, timing and timbre) to convey meaning, rely on systematic sound-symbol representations, and require analytic listening, selective attention, auditory memory, and the ability to integrate discrete units of information into a coherent and meaningful percept (Kraus & Chandrasekaran, 2010; Patel, 2011). This widespread recruitment of shared processes, ranging from the perceptual to the cognitive, makes music and language ideal cognitive activities in which to observe the phenomenon of transfer (for a review, Moreno & Bidelman, 2013; for a complete discussion, White et al., in press). The purpose of the present study is to investigate the domain-specific and domain-general benefits of either second-language learning or music training and consider a potential transfer mechanism responsible for these training effects.

In the fields of music training and bilingualism, studies have highlighted transfer to several other cognitive skills, although most of the evidence has been provided by correlational studies comparing experts and non-experts on general cognitive skills such as executive control (Bialystok, Craik, Klein, & Viswanathan, 2004), working memory (Pallesen et al., 2010), and intelligence (Forgeard, Winner, Norton, & Schlaug, 2008). Transfer is considered to occur when novel and trained tasks recruit overlapping processing components and engage shared brain regions (Jonides, 2004). Bialystok, Craik, Green, and Gollan (2009) reviewed a large body of evidence indicating bilinguals’ advantage in executive functions, demonstrating how an intensive “training” experience is expressed in enhancement of a crucial set of domain-general cognitive processes. These findings have been attributed to bilinguals’ increased need to manage attention to two competing languages that are jointly available during linguistic performance (Bialystok et al., 2009; Green, 1998). In the music literature, recent reviews have also illustrated the benefits of music training for behavioral skills such as language, verbal intelligence, reading, and inhibition (Moreno & Bidelman, 2013; Patel, 2011; Slevc, 2012) from very young (Gerry, Unrau, & Trainor, 2012) to aging populations (Parbery-Clark, Anderson, Hittner, & Kraus, 2012). For musicians, these findings have been attributed to their considerable training requirements involving intensive memorization and multi-sensory coordination and monitoring (see review in Wan & Schlaug, 2010). Accordingly, learning music or language seems to be beneficial for more general aspects of cognitive development, possibly because the experience enhances core skills such as executive functions (Blair & Razza, 2007; Krizman, Marian, Shook, Skoe, & Kraus, 2012), which in turn improves other cognitive skills (Moreno & Bidelman, 2013).

In spite of this evidence, the underlying mechanisms responsible for these training effects are elusive. Recently, Gazzaley and Nobre (2012) proposed a top-down control hypothesis as a common neural mechanism underlying cognitive operations. This mechanism modulates the activity in stimulus-selective cortices with concurrent engagement of prefrontal and parietal control regions that are sources of top-down signals. Evidence for such a mechanism has been shown in both animal and human research. For example, Polley, Steinberg, and Merzenich (2006), found that responses in the auditory cortices of rats were modulated by task specific top-down inputs (i.e., task demands). These discoveries have motivated Moreno and Bidelman (2013) to suggest a model of transfer that highlights the role of executive functions, specifically top-down control processing, to mediate transfer between cognitive functions. This framework hypothesizes that training in one domain (e.g., music or language) induces not only domain-specific benefits, but also domain-general benefits with attention processing serving as a mediator (also see Bialystok & DePape, 2009). For example, Moreno et al. (2011) showed that improvements of verbal intelligence scores in children following music training were positively correlated with functional plasticity in the fronto-parietal network (i.e., in a go-nogo task which involves cognitive control and attention).

In order to further explore this top-down control hypothesis, we conducted a longitudinal study in which participants were tested before and after French language or music training, and again in a one year follow-up. We measured the event-related potentials (ERPs) for mismatch negativity (i.e., MMN, peaking between 100–250 ms) and late discriminative negativity (i.e., LDN, peaking at a later latency after 400 ms) in an odd-ball paradigm to investigate auditory change detection in young children at the neural level. The MMN is an index of sensory memory-based detection of auditory change and reflects early bottom-up processing (Näätänen, Paavilainen, Rinne, & Alho, 2007). In children, the MMN is less reliable than in adults and often followed by the LDN; both the MMN and LDN show fronto-central scalp distributions. The LDN is usually not seen in adults (observed only when attending to the stimulus) (Wetzel, Widmann, Berti, & Schröger, 2006), and therefore its presence may indicate developmental processing of auditory changes. The two most common interpretations of the LDN’s functional role indicate a top-down mechanism influencing auditory processing. These two interpretations of LDN have been identified as: (a) the reorienting of attention after being distracted by a deviant sound (Shestakova, Huotilainen, & Cheour, 2003; Wetzel et al., 2006) similar to the reorienting negativity response observed in adults, and (b) a regulation of auditory processing at a higherorder cognitive level that follows the initial change detection reflected by the MMN (Čeponienė et al., 2004; Horváth, Roeber, & Schröger, 2009) (see Putkinen, Tervaniemi, and Huotilainen, 2012b, for details). In the case of (b), there is no relation between the amplitudes of the MMN, P3a, and LDN (e.g., LDN responses could be recorded without a preceding P3a), suggesting independent processes underlying these components (Putkinen, Niinikuru, Lipsanen, Tervaniemi, & Huotilainen, 2012a). These two interpretations of LDN are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as there could be several temporally overlapping but functionally distinct components in the LDN time range that are differentially activated depending on the specifics of the stimuli and task (Putkinen et al., 2012a; Putkinen et al., 2012b). Therefore, these ERP measures from an odd-ball paradigm allow for observation of both bottom-up and top-down processing.

Few developmental studies have examined changes in auditory electrophysiological indices in preschool children, and studies of these changes induced by music training or second-language learning are even scarcer. The difficulties in testing this population, paired with the challenges faced when conducting longitudinal studies (i.e., including a control group, drop-out participants) make it almost impossible to look at this crucial developmental stage. Nevertheless, a few studies report results which provide insight into the effects of training on MMN and LDN in young children. In one study (Shestakova et al., 2003), the auditory ERPs of Finnish-speaking 3-to 6-year-old children in a French language learning group (following three to four months of French language training) were compared to a no-contact control group. The results showed an increase of MMN and LDN responses to French vowel sounds in the French learning group. The authors suggested that while the MMN indexes development of French-specific auditory processing in these children, the LDN may reflect reorienting of attention to the task (i.e., watching a movie) after being distracted by the familiar French sound. Thus, their results support the possible function of the LDN in a top-down regulation process. Moreover, studies of musically trained children or children who have had significant music exposure found enhanced MMN to musical tones or speech sounds (Chobert, Marie, François, Schön, & Besson, 2011; Meyer et al., 2011; Putkinen, Tervaniemi, Saarikivi, de Vent, & Huotilainen, 2014; Virtala, Huotilainen, Putkinen, Makkonen, & Tervaniemi, 2012) and changes in LDN (Putkinen et al., 2012b). Putkinen et al. (2012b) showed a relation between informal musical activities at home and specific ERP components in 2- to 3-year-old children. The authors used a multi-feature paradigm that included frequency, duration, intensity, direction, gap deviants, and attention-catching novel tones. Their results showed correlations between several evoked brain responses induced in this type of task and the amount of musical activity at home (i.e., musical play by the child and parental singing reported by the parents). Specifically, their data showed that greater informal musical experiences were associated with reduced LDNs to varying novel sounds (e.g., different environmental sounds such as machines, animals) in early childhood, indicating lowered distractibility (Putkinen et al., 2012b, p. 5). These novel sound stimuli have been used in studies to trigger cognitive processes related to novelty detection and distraction (e.g., Gumenyuk, Korzyukov, Alho, Escera, & Näätänen, 2004; also see the Method of Putkinen et al. 2012b). Putkinen et al. suggested that the changes in brain responses highlight the importance of musical experience in facilitating the development of crucial auditory abilities in early childhood. Although these two studies by Shestakova and Putkinen did not directly compare training with responses to untrained tasks, the collective findings from these studies demonstrated different LDN changes according to the relevance of the deviant sound: LDN was enhanced with a familiar, trained sound (e.g., French vowel following French language training in Shestakova et al., 2003), but reduced with irrelevant, untrained sounds (e.g., different novel tones in Putkinen et al., 2012a).

In another study which used an auditory odd-ball paradigm to observe the effects of music and language experience on auditory skills, Milovanov and colleagues (2009) studied older children who had advanced foreign language pronunciation and musicality skills. Their results showed that these children, compared to a non-expert group, displayed enhanced MMNs to duration changes in both speech and musical sounds. Using a different approach, Marie, Kujala, and Besson (2012) compared the effects of linguistic and musical expertise in an adult population. As Finnish is a language in which phonemic duration is linguistically relevant, Finnish participants were tested as linguistic experts. Their results indicated an increase of MMN amplitude for duration deviants in harmonic sounds in Finnish non-musicians and French musicians compared to controls, who were French non-musicians. The authors concluded that there was common processing of duration in music and speech, which might allow for transfer between language and music auditory processing. Unfortunately LDN was not reported in either study, so the role of a higher-order cognitive regulation of auditory processing in this type of transfer could not be assessed. The use of correlational designs also limited these results.

The present study investigated functional brain changes in the detection of auditory anomaly by examining the effect of two experiences on children’s performance, second-language learning and music training. English-speaking children followed either French language or music training in a summer camp setting for four weeks. In an oddball paradigm, both groups were tested in two conditions, with French vowel or musical note stimuli presented in separate runs, creating a double dissociation design. This paradigm allowed us to test both the specific effects of training and the bi-directional transfer between music and language processing (Bidelman, Hutka, & Moreno, 2013) by measuring domain-specific changes (e.g., vowel condition for the French group, note condition for the music group) and domain-general changes (e.g., note condition for the French group, vowel condition for the music group) in the brain following training. Additionally, we examined the top-down control hypothesis (Moreno & Bidelman, 2013) suggesting attention as a medium for transfer between perceptual and cognitive functions. We focused on changes in the LDN, as the LDN displays training-dependent plasticity (Näätänen et al., 2007; Putkinen et al., 2012b; Shestakova et al., 2003), and may reflect reorienting of attention or higher-order processing of auditory changes, or a combination of both (Čeponienė et al., 2004; Horváth et al., 2009; Putkinen et al., 2012b).

The design was a longitudinal intervention (i.e., test/training/retest/follow up) with young children (i.e., 4- to 6-year-olds). None of the children had prior experience with either a second language or with music. Each testing session used the same battery of tests (with two alternate versions). There were three hypotheses. First, we expected an increase of MMN amplitude after training in both conditions (i.e., musical notes and French vowels), reflecting improved auditory skills in each training group. Second, we held the assumption that LDN is related to top-down control processing (Putkinen et al., 2012a; Shestakova et al., 2003) and as such, we expected to observe LDN modulation after training. Specifically, we speculated that an increase in amplitude of evoked brain responses would be observed to the trained sounds, as was demonstrated by Shestakova et al. (2003), and a reduction of amplitude would be observed to the untrained stimuli, as was shown in Putkinen et al. (2012b). Finally, following Kraus and Chandrasekaran (2010) who introduced the notion that music learning can have a lasting positive influence even after training or practice has completely stopped (also see Parbery-Clark et al., 2012), we predicted that these changes would remain detectable one year following the end of the training. However, because Kraus and Chandrasekaran used a cross-sectional design, the interpretations of their findings are limited. By following up with participants one year after the end of training in our longitudinal study, we could explore and substantiate this notion of lasting positive influence posited by Kraus and Chandrasekaran. If early experience indeed showed lasting benefits, this finding would have strong implications for the improvement of education systems through introducing cognitive training to pre-school education curriculums.

Method

Participants

Thirty-six monolingual English-speaking children between 4- and 6-years of age who had no prior musical or French language training were recruited. Parents filled out a detailed questionnaire to provide background information (e.g., formal music training, languages spoken at home, languages understood by the child, parent’s rating of the child’s second language abilities). None of the children were able to speak a second language. Most children were right-handed except for two children in the French group and one child in the music group. At pre-test (before training), both groups (n = 18 each) were similar in age (French, M = 67.1 months, SD = 6.6, 11 males; Music, M = 66.0 months, SD = 7.0, 8 males), English vocabulary scores (PPVT: French, M = 113.9, SD = 14.8; Music, M = 113.3, SD = 12.8), nonverbal intelligence (Raven’s: French, M = 106.9, SD = 15.1; Music, M = 100.8, SD = 9.9), and SES based on parents’ education (French, M = 3.7, SD = 0.8; Music, M = 3.5, SD = 0.9; see SI for the SES scale). After one year, 16 children from the French group and 14 children from the music group returned for follow-up testing (French: M = 81.5 months, SD = 6.1; Music: M = 78.3 months, SD = 6.9). These subgroups remained similar in age, t(28) = 1.25, ns, and SES, t(28) = 1.05, ns, and had comparable scores on the PPVT, t(28) = .28, ns, and Raven’s t(28) = .90, ns, at pre-test. During the intervening year between post-test and follow-up, two children in the music group continued formal music training (piano for 30 mins – 1 hour a week) and two children in the French group received formal music training (piano or violin for 1 hour a week). No participant was reported to receive French language training. Excluding these children did not affect the results (see the supplementary information), thus, these children were included in the follow-up data. The study received Research Ethics Committee approval and all parents provided written informed consent. The procedure was individually explained to children and their assent was obtained prior to each testing session. Children were given presents at the end of the session for their participation.

Study Design

The study used a four-phase longitudinal design: pre-test, training, post-test, and one year follow-up. Children were tested individually by a research assistant who was blind to the type of training the child was receiving. After the pre-test, children were assigned to French language or musical training in a pseudo-random manner to ensure that there were no pre-training differences between groups in their intelligence scores or the background questionnaire. Immediately after training (i.e., between 5 and 20 days after the end of the training) and at one year after training, children returned to our laboratory to be re-assessed with EEG as well as behavioral measures.

Training

Training was conducted in the form of a summer camp. The children engaged in computer-based training programs projected on the wall with their respective teacher in a classroom setting for two 1-hour sessions each day for four weeks (15 minutes for organization and 45 minutes of training, 20 days in total). Two computerized training programs were created by the first author (see the supplementary information for a detailed description and learning objectives of the training programs). Both training programs shared the same learning goals (e.g., listening, production, reading), graphics and design, duration, number of breaks, and number of teaching staff; the only difference was the content of the training. The curriculum in the music training was based on a combination of motor, perceptual, and cognitive tasks and included training on rhythm, pitch, melody, voice, and basic musical concepts. The training in French language included vocabulary learning (e.g., days of the week, body parts, animals) and communication schemes (e.g., interacting with a character in the projected game). Both programs involved activity or discussion with the teacher or with other children in the class.

EEG Task Stimuli

The EEG experiment had two conditions which were tested in separate blocks: vowel and note. The presentation order of conditions was counterbalanced across participants, and the same stimuli were used at each of the three testing sessions. Sound tokens used during the EEG task were created independently from the training (e.g., the French speaker who recorded the experimental stimuli was not the teacher for the French training). The vowel condition presented two French vowels spoken in a female voice (by a native French speaker), ou [u] and o [y], as the standard or deviant. The standard and deviant stimuli were alternated between pre- and post-test: for example, if [u] was used as the standard and [y] as the deviant at pre-test, then these roles were reversed in the post-test. One year follow-up used the same version as pre-test. The duration of each vowel was 280 ms (i.e., the majority of the energy had died out by 240 ms). The note condition involved synthesized piano tones A and A# as the standard or deviant. The choice of the standard and deviant sounds was alternated between pre- and post-test for this condition as well. The duration of the tone was 1000 ms but the energy had died out by 750 ms (see Figure S1 for spectrogram). Although the stimulus duration was different in the vowel and note conditions, we were interested in keeping natural acoustic features and presenting the sound as naturally as possible. We aimed to measure the effect of training on sound processing across groups rather than directly comparing the two sound conditions within a group. After training, French vowels should have become more familiar to children in the French group and piano tones should have sounded more familiar to those in the music group. The sound onset asynchrony (SOA) was 1500 ms in both conditions so that the onset of the stimulus was the same despite varying stimulus duration for each of the two conditions. There were a total of 300 trials in each condition including 45 deviants (15% of the trials).

Procedure

A passive auditory odd-ball paradigm was used in EEG testing. During EEG recording, the children sat in a comfortable chair and watched a silent movie of their choice displayed on the computer screen. They were told to attend to the movie and ignore the sounds as they would be asked about the contents of the movie. The sounds were played from two loudspeakers at 80 dB. After the experiment, the research assistant asked questions to ensure that children had attended to the movie.

EEG Recording and Data Analysis

EEG was recorded using a 70 channel Biosemi ActiveTwo amplifier system (sampling rate of 512 Hz) with electrodes placed around the scalp according to standard 10–20 locations (Oostenveld & Praamstra, 2001). During EEG acquisition, all electrodes were referenced to the CMS (Common Mode Sense) electrode, with the DRL (Driven Right Leg) electrode serving as the common ground. Subsequent analyses were performed in EEGLAB (Delorme & Makeig, 2004) and utilized custom routines coded in MATLAB (The MathWorks). Data were re-referenced off-line to the average of all electrodes. Eye movements and artefacts were corrected in the continuous EEG using PCA decomposition in EEGLAB. Excessively noisy channels were interpolated (two nearest electrodes). Trials with residual voltages exceeding ±150 µV were rejected prior to averaging. Due to a small number of deviant trials, noise was reduced by artefact rejection and all trials were entered into analysis. The EEG was epoched (−200–1000 ms), baseline-corrected to the pre-stimulus interval, and subsequently averaged in the time domain to obtain ERPs for each response type at each electrode site per stimulus condition (i.e., standard and deviant responses in the vowel or note condition). Grand averaged ERPs were then digitally filtered (0.1–30 Hz, zero-phase response) to attenuate non-meaningful fluctuations in the evoked response.

Difference waveforms were derived by subtracting ERPs to the standard stimuli from their corresponding deviant ERPs of the same sequence (i.e., deviants – standards). MMN was manually identified as the most negative peak in the 100–300 ms time window of the difference waveform in Fz, FCz and Cz of each participant.

For LDN, a sustained slow-wave over a large latency window, mean ERP amplitudes were computed in the latency windows selected based on prior research and visual inspection of the waveforms (Luck, 2005; Shestakova et al., 2003). The analysis was focused on frontal electrodes such as AF3, AFz, AF4, F1, Fz, F2, FC1, FCz, F3, F5, F4, F6. Latency windows and electrodes differed in the analysis of pre vs. post data and one year follow-up data: for pre vs. post, the vowel condition window was 650–850 ms and the note condition was 450–650 ms; for comparison of three sessions (pre, post, follow-up) in the subgroups, the vowel condition window was 475–600 ms and the note condition was 450–600 ms. ANOVAs were conducted on mean amplitude values given a latency window, using group as a between-subjects factor and session (pre vs. post, or across three sessions) as within-subject factors.

Results

Pre vs. Post Training Results

There were no group differences at pre-test on age, intelligence scores, or socioeconomic status (SES) (n = 18 in each group, see Methods). At pre-test, the groups were also similar on MMN vowel peak amplitude, t(34) = −.74, ns; note peak amplitude, t(34) = .24, ns), and on LDN vowel mean amplitude, t(34) = 1.14, ns; note mean amplitude, t(34) = −.98, ns).

The vowel sounds and musical notes elicited a significant MMN in both pre- and post-test (see Table 1). In the vowel condition, both the second-language and music training group showed an MMN that was significantly different from 0 (one sample t-tests, two-tailed): French group (pre, t(17) = −4.60, p < .001; post, t(17) = −5.21, p < .001), music group (pre, t(17) = −4.99, p < .001; post, t(17) = −5.51, p < .001). In the note condition, both groups also showed a significant MMN (one sample t-tests, two-tailed): French (pre, t(17) = −4.71, p < .001; post, t(17) = −5.08, p < .001), Music (pre, t(17) = −4.46, p < .001; post, t(17) = −2.97, p = .009).

Table 1.

MMN peak amplitude (averaged across Fz, FCz, Cz)

| Vowel | Note | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | FU | Pre | Post | FU | |

| French | −2.91 (0.63) | −2.75*** (0.53) | −3.42*** (0.49) | −2.57*** (0.54) | −2.47*** (0.49) | −2.33*** (0.43) |

| Music | −2.33** (0.47) | −2.28*** (0.41) | −2.34*** (0.53) | −2.15*** (0.48) | −1.76** (0.59) | −2.20** (0.65) |

At pre and post: French n = 18, Music n = 18. At follow-up (FU), French n = 16, Music n = 14. Note that for repeated measures ANOVAs in follow-up results included only subgroups of children who completed all three sessions. Results for one-sample t-test:

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001 (two-tailed); SE of mean in a bracket.

To assess the effect of training and bi-directional transfer between music and language processing, a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA (group × session) was conducted in each condition with MMN and LDN as dependent variables. Results of ANOVAs on other electrophysiological components (deviant ERP, standard ERP) can be found in SI.

MMN responses

In both vowel and note conditions, a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA (group × session) on MMN amplitude found no significant effect of either factor or their interaction.

LDN responses

LDN responses in each condition were averaged across frontal electrodes for a given time window. For the vowel condition (latency window 650–850 ms), a 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA (group × session) found a significant interaction of group×session, F(1, 34) = 4.66, p < .04, ηp2 = 0.12, but no main effect of group or session (all F < 1). Figure 1(a, b) depicts LDN amplitude change between pre and post in each group, which reveals that after training, the French group showed increased LDN and the music group demonstrated decreased LDN to the vowel sounds.

Figure 1.

Training effect in the vowel (a, b, left panel) and note (c, d, right panel) conditions. (a, c) Difference wave (i.e., deviant – standard) at Fz (as a representative electrode) is shown for each group (n = 18 each). (b, d) LDN change (i.e., pre – post in each group) was averaged across six frontal electrodes (AF3, AFz, AF4, F1, Fz, F2) in the latency window of 650–850 ms for (b) the vowel condition and 450–650 ms for (d) the note condition. The trained group showed enhanced LDN to the trained sound (French group-vowel; music group-note), whereas the untrained group showed decreased LDN to the untrained sound (French group-note, music group-vowel). Error bars = s.e.m.

Similarly, the note condition (latency window 450–650 ms) also found a significant interaction of group × session, F(1, 34) = 4.43, p = .04, ηp2 = 0.12, again with no main effects (all F < 1). Figure 1(c, d) shows the patterns of LDN change in the note condition: the music group showed enhanced LDN to their trained sounds (French vowel), and the French group exhibited reduced LDN to the untrained (music) stimuli. Therefore, both groups showed similar patterns of LDN amplitude change across the tasks in which there was increased LDN to the trained sounds and decreased LDN to the untrained sounds.

One Year Follow-up Results

One year after the end of the training, 16 children in the French group and 14 children in the music group returned to the laboratory for follow-up testing. These subgroups did not significantly differ in age, intelligence scores, or SES (see Methods). Moreover, there were no differences in these subgroups at pre-test on MMN (vowel peak amplitude, t(28) = − .54, ns; note amplitude, t(28) = − .43, ns) and LDN (vowel mean amplitude, left sites, t(28) = .03, ns, right sites, t(28) = .25, ns; note mean amplitude, t(28) = 1.73, ns; see LDN results below for electrode information). The follow-up study examined the changes across all three sessions (pre, post, follow-up) in these subgroups of children (see SI Table S2 and S3 for LDN values).

MMN responses

In both vowel and note conditions, a 2 × 3 mixed ANOVA (group × session) on MMN amplitude found no significant effect (see Table 1 for MMN follow-up values).

LDN responses

In the vowel condition, visual inspection of the waveforms revealed hemispheric differences in the wave patterns of the two groups (see Figure 2a). Accordingly, a three-way mixed ANOVA (2 groups × 3 sessions × 2 lateralities) was conducted with left (averaged F3, F5) and right (averaged F4, F6) frontal sites (latency window 475–600 ms) and with all testing sessions (pre, post, follow-up). The ANOVA revealed a significant three-way interaction, F(2, 56) = 3.64, p = .03, ηp2 = .12, indicating that at follow-up, enhanced LDN was found in left frontal sites, relative to the right, in the French group while a reversed pattern was shown in the music group. Figure 2a shows these opposite patterns of the LDN amplitude change in the two groups. To further examine this finding, a 2 (group) × 2 (laterality) ANOVA was performed separately on the follow-up data only: The results showed a significant interaction of group and laterality, F(1, 28) = 9.18, p = .005, ηp2 = .25, and no other effect. At follow-up, the French group showed a larger LDN amplitude on the left compared to the right, F(1, 15) = 4.70, p = .047, ηp2 = .24 (one-way repeated ANOVA), while the music group showed a larger amplitude on the right compared to the left, F(1,13) = 4.64, p = .05, ηp2 = .26 (one-way repeated ANOVA). Therefore, after one year, the French group exhibited enhanced LDN to the vowel sound, but at an earlier latency window than in the pre versus post results, and this effect was shifted to the left frontal sites from the fronto-central sites observed in the pre versus post results (see Figure 3). The music group, on the other hand, showed larger LDN on the right frontal sites than on the left at follow-up.

Figure 2.

Lasting training effects after one year. (a) Vowel condition. Difference wave (i.e., deviant – standard) at F3 and F4 (as representative electrodes for left and right, respectively) are shown for each group in the post and follow-up sessions (n = 16 in French group, n = 14 in music group). At follow-up (latency window 475–600 ms), the French group showed enhanced LDN on the left compared to right, and the music group showed enhanced LDN on the right compared to left (also see Fig. 3). (b) Note condition. Difference wave at Fz (as a representative electrode) is shown for each group across three testing sessions (n = 16 in French, n = 14 in music). At follow-up (latency window 450–600 ms), the music group maintained LDN to the musical sound (albeit reduced), whereas the French group showed LDN similar to that of the pretest. Error bars = s.e.m.

Figure 3.

Laterality effects in the vowel condition at one year follow-up. LDN change from pre (i.e., pre – follow-up in each group) was averaged across two left (F3, F5) and two right (F4, F6) electrodes in the latency window of 475–600 ms. The French group (n = 16) showed enhanced LDN to the vowel sounds on the left electrodes at follow-up session, whereas the music group (n = 14) showed increased LDN to the vowel sound on the right frontal sites at follow-up. Note that pre – post was not plotted as the laterality effects were not observed at post-test. Error bars = s.e.m. FU = follow-up, L = left, R = right.

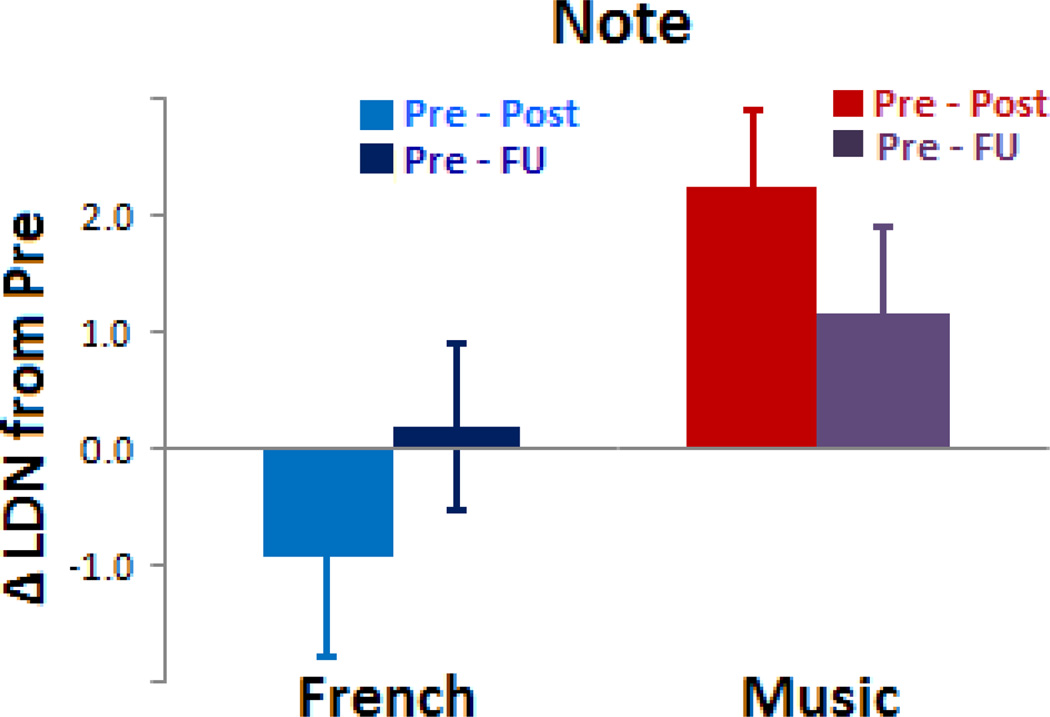

In the note condition, significant results were found in the same frontal channels that were used in the pre versus post analysis, but at a shorter latency window (450–600 ms). As no laterality difference was found in the note condition, a two-way mixed ANOVA was conducted with two groups and three sessions. The results showed a significant group×session interaction, F(2, 56) = 4.61, p = .014, ηp2 = .14, suggesting that the two groups showed different patterns of LDN changes across the three sessions (see Figure 2b and Figure 4), but no other effect was significant (all F < 1). To examine this interaction further, one-way repeated ANOVAs were performed within each group: the music group showed a significant session effect, F(2, 26) = 3.78, p = .036, ηp2 = .23, whereas the French group did not, F(2, 30) = 1.46, p = .25, ηp2 = .09, indicating that this LDN was modulated by music training.

Figure 4.

Lasting effects in the note condition at one year follow-up. LDN change (i.e., pre – post, or pre – follow-up in each group) was averaged across six frontal electrodes (AF3, AFz, AF4, F1, Fz, F2) in the latency window of 450–600 ms. Note that values are slightly different from Figure 1d because the latency window for Figure 1d was longer (450–650 ms). The graphs illustrate different patterns of LDN change observed in the two training groups: the trained group (music on the right) maintained LDN to the trained sound at follow-up (albeit reduced), whereas the untrained group (French on the left) showed LDN returned to baseline at pre. Error bars= s.e.m.

Discussion

Our findings present a demonstration of the underlying functional mechanism governing neuroplasticity effects in early childhood after a short training period (see Hyde et al., 2009, and Schlaug et al., 2009 for structural changes). Training in music and second-language learning induced training-specific effects and domain-general changes (i.e., French group in the music note condition; Music group in the French vowel condition), indicating the bi-directional link between music and language processing (Bidelman et al., 2013). Our results, showing LDN changes, are consistent with the explanation that training mechanisms are mediated at least in part by top-down regulation (Moreno & Bidelman, 2013). Moreover, one year after our training, we still observed training-induced brain responses, demonstrating that even a short exposure to an auditory training period has a lasting effect in children specific to the type of training received.

Training Effects: Top-down Regulation Mechanism on Auditory Processing

Our training induced significant changes in LDN, but not in MMN. We believe that this lack of change in MMN can be attributed to two factors. First, our training was not designed to improve auditory discrimination of specific sounds, which is the case in some instrumental training programs (e.g., Suzuki method), but rather to train and improve cognitive skills such as executive functions. More precisely, in the present study, the participants were not directly trained on the exact sound stimuli that were used for the experiment, although the experimental stimuli were part of commonly used musical notes or French vowels that the children probably heard at some point during the class. Second, the studies reporting enhanced MMN examined children who underwent long-term training: 12–16 weeks of French language training in 3–6 year old children (Shestakova et al., 2003), 4 years of music instrument training in 9 year old children (Chobert et al., 2011), 5 years of violin training in 7–12 year old children (Meyer et al., 2011), 2–5 years of music instrument training in 9–13 year old children (Putkinen et al., 2014). In Putkinen et al. (2014), an enhanced MMN for some sound features (e.g., timbre deviants) was not present in 9 year old children with 2 years of music training but it was observed in 11 year old children with 4 years of music training, suggesting an importance of accumulation of training. Unlike these studies, our training only lasted 4 weeks. It is possible that MMN was not enhanced because of either of these two factors – lack of training directly targeting discrimination of specific sound features or time-limited training duration.

After training, both groups showed enhanced LDN in their trained task, a pattern that is in line with the electrophysiological brain plasticity effects of training within the auditory domain (Moreno & Bidelman, 2013). We interpret this increase as reflecting improved auditory processing through specific experience (Čeponienė et al., 2004; Horváth et al., 2009). Our results are consistent with previous reports of an influence of music training (Fujioka, Ross, Kakigi, Pantev, & Trainor, 2006; Herholz & Zatorre, 2012), second-language training (Conboy & Kuhl, 2011; Shestakova et al., 2003), and auditory training (Reinke, He, Wang, & Alain, 2003) on auditory brain responses. Increased auditory ERP amplitude has been interpreted as reflecting an increase in neuronal representation resulting from training (Recanzone, Schreiner, & Merzenich, 1993), or as an improvement in neural synchrony (Tremblay, Kraus, McGee, Ponton, & Otis, 2001). Our LDN results are consistent with the interpretation that LDN reflects a regulation of auditory processing (Čeponienė et al., 2004; Horváth et al., 2009) (see Putkinen et al., 2012a, 2012b, for review).

We also observed reduced LDN after training to untrained stimuli, a change we interpret as reflecting top-down regulation of auditory processing (Gazzaley, 2011, 2013; Zanto, Rubens, Thangavel, & Gazzaley, 2011; Zhou, de Villers-Sidani, Panizzutti, & Merzenich, 2010). This pattern is consistent with several findings that have linked the functional role of LDN to attention processing (i.e., reduced LDN related to lowered distractibility and increased LDN related to reorienting of attention back to a task, such as watching a movie, after being distracted by familiar sounds) (Putkinen et al., 2012a; Shestakova et al., 2003; Wetzel et al., 2006). Such evidence also can be found in the literature showing that the amplitude of LDN increases when children perform an active oddball task (i.e., attended condition) compared to when they do not pay attention to the task in a passive oddball (Mueller, Brehmer, von Oertzen, Li, & Lindenberger, 2008; Wetzel et al., 2006). In adults as well, LDN is usually absent in a passive oddball task and present during an active oddball task (Wetzel et al., 2006). Therefore, we suggest that the observed effects, both increased and decreased LDN, are modulated by a top-down regulation mechanism, such that increased LDN to the trained stimuli reflects heightened auditory processing of the stimuli, and that decreased LDN to the untrained stimuli reflects involuntary suppression of the irrelevant sound in order to pay better attention to the task (i.e., watching a silent movie). These results demonstrate that LDN shows two different responses depending on the contextual situation. Future research should explore unfamiliar sounds that are not related to music or language to determine if the patterns of response change.

A top-down regulation of sensory processes as we have interpreted above has been supported by other recent findings. For example, top-down modulation has been proposed as a common neural mechanism underlying cognitive operations (Gazzaley & Nobre, 2012). This mechanism would modulate the activity in stimulus-selective auditory cortices with concurrent engagement of prefrontal and parietal control regions that are sources of top-down signals. Such a mechanism has also been shown in animals. Auditory cortical areas in rats can be modified moment to moment in time as a function of behavioral context (Zhou et al., 2010; also see Polley et al., 2006). These adaptive changes can be interpreted as a top-down regulation mechanism impacting the auditory system. Furthermore, previous studies in monkeys and humans have recorded fluctuations in ongoing activity levels that at least partially reflect facilitatory and suppressive modulatory effects in the auditory system (Alho, Woods, & Algazi, 1994; Rossi, Pessoa, Desimone, & Ungerleider, 2009; Telkemeyer et al., 2009). Finally, the present study showed that modulation in LDN was observed in both types of training but in ways that were specific to each training. These results, in line with the model proposed by Moreno and Bidelman (2013), suggest that top-down processing, indexed by LDN, plays a mediator role in transfer between cognitive abilities (also see Strait & Kraus, 2011). However, the theoretical question remains of whether cross-domain effects and skill transfer are distinguished. Our data cannot address this theoretical point and more studies are needed to define the notions of transfer. Our study is just a preliminary step in this direction.

One Year Follow-up: Concept of Developmental Trajectory Change after Training

Our one year follow-up results demonstrated the lasting effects at both quantitative (as discussed above) and qualitative levels. In both the vowel and note conditions, the results showed attenuated but persistent training-induced ERP responses for both groups. We interpret these results as maintenance of the brain plasticity observed immediately after training. This finding was surprising because of the short-term exposure to the training and the prolonged time gap between the second (post) and third (follow-up) testing sessions without training. These results exhibit the powerful impact of music and second language training on the developing brain.

At the follow-up phase, the music group showed a lasting effect in both tasks but the effect in the French group remained only in the vowel condition, indicating a stronger effect of music training. However, we observed qualitative effects in the vowel condition in which both groups showed hemispheric modifications, absent at post-test, one year after the discontinuation of training. The French group showed a change in the left hemisphere while the music group showed an opposite pattern to the French vowel sounds, which is consistent with the literature (language: Szaflarski, Holland, Schmithorst, & Byars, 2006, for a review see Holland et al., 2007; music: Schlaug, Marchina, & Norton, 2008; for a review see Jäncke, 2009). We speculate that both types of training reinforced the capacity of brain plasticity in the principal hemisphere involved in their trained domain: left for language training and right for music training. This speculation is supported by evidence suggesting that processing that is more consistently activated by sensory stimuli during early development is advantaged and preferentially consolidated (Berardi, Pizzorusso, & Maffei, 2000; Eggermont, 2007; Fagiolini, Pizzorusso, Berardi, Domenici, & Maffei, 1994; Gordon & Stryker, 1996). Therefore, our findings imply that different types of auditory training can selectively stimulate the brain and facilitate hemispheric specialization, which reflects the developmental process of skill acquisition and the maturation of the brain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health (Grant R01HD052523) to E.B., and the Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario (FedDev Ontario) to S.M.

References

- Alho K, Woods DL, Algazi A. Processing of auditory stimuli during auditory and visual attention as revealed by event-related potentials. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:469–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi N, Pizzorusso T, Maffei L. Critical periods during sensory development. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2000;10:138–145. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)00047-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0959- 4388(99)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Craik FI, Klein R, Viswanathan M. Bilingualism, aging, and cognitive control: Evidence from the Simon task. Psychology and aging. 2004;19:290–303. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Craik FIM, Green DW, Gollan TH. Bilingual minds. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;10:89–129. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, DePape A. Musical expertise, bilingualism, and executive functioning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2009;35:565–574. doi: 10.1037/a0012735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidelman GM, Hutka S, Moreno S. Tone Language Speakers and Musicians Share Enhanced Perceptual and Cognitive Abilities for Musical Pitch: Evidence for Bidirectionality between the Domains of Language and Music. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Razza RP. Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child development. 2007;78:647–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Čeponienė R, Lepistö T, Soininen M, Aronen E, Alku P, Näätänen R. Event-related potentials associated with sound discrimination versus novelty detection in children. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:130–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2003.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy BT, Kuhl PK. Impact of second-language experience in infancy: Brain measures of first- and second-language speech perception. Developmental Science. 2011;14:242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2004;134:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ. Correlated neural activity as the driving force for functional changes in auditory cortex. Hearing Research. 2007;229:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagiolini M, Pizzorusso T, Berardi N, Domenici L, Maffei L. Functional postnatal development of the rat primary visual cortex and the role of visual experience: Dark rearing and monocular deprivation. Vision research. 1994;34:709–720. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90210-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(94)90210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgeard M, Winner E, Norton A, Schlaug G. Practicing a musical instrument in childhood is associated with enhanced verbal ability and nonverbal reasoning. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka T, Ross B, Kakigi R, Pantev C, Trainor L. One year of musical training affects development of auditory cortical-evoked fields in young children. Brain: Journal of Neurology. 2006;129:2593–2608. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A. Influence of early attentional modulation on working memory. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:1410–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A. Top-down modulation and cognitive aging. In: Stuss DT, Knight RT, editors. Principles of frontal lobe function. Second ed. OUP USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Nobre AC. Top-down modulation: Bridging selective attention and working memory. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2012;16:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerry D, Unrau A, Trainor LJ. Active music classes in infancy enhance musical, communicative and social development. Developmental science. 2012;15:398–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JA, Stryker MP. Experience-dependent plasticity of binocular responses in the primary visual cortex of the mouse. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:3274–3286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DW. Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 1998;1:67–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1366728998000133. [Google Scholar]

- Gumenyuk V, Korzyukov O, Alho K, Escera C, Näätänen R. Effects of auditory distraction on electrophysiological brain activity and performance in children aged 8–13 years. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:30–36. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herholz SC, Zatorre RJ. Musical Training as a Framework for Brain Plasticity: Behavior, Function, and Structure. Neuron. 2012;76:486–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland SK, Vannest J, Mecoli M, Jacola LM, Tillema J-M, Karunanayaka PR, Byars AW. Functional MRI of language lateralization during development in children. International journal of audiology. 2007;46:533–551. doi: 10.1080/14992020701448994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horváth J, Roeber U, Schröger E. The utility of brief, spectrally rich, dynamic sounds in the passive oddball paradigm. Neuroscience letters. 2009;461:262–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde KL, Lerch J, Norton A, Foregeard M, Winner E, Evans AC, Schlaug G. Musical training shapes structural brain development. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:3019–3025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5118-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäncke L. The plastic human brain. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 2009;27:521–538. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2009-0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J. How does practice make perfect? Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:10–11. doi: 10.1038/nn0104-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus N, Chandrasekaran B. Music training for the development of auditory skills. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:599–605. doi: 10.1038/nrn2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizman J, Marian V, Shook A, Skoe E, Kraus N. Subcortical encoding of sound is enhanced in bilinguals and relates to executive function advantages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:7877–7881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201575109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll JF, Bialystok E. Understanding the consequences of bilingualism for language processing and cognition. Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 2013;25:497–514. doi: 10.1080/20445911.2013.799170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ. An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique. 1st ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marie C, Kujala T, Besson M. Musical and linguistic expertise influence pre-attentive and attentive processing of non-speech sounds. Cortex. 2012;48:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller V, Brehmer Y, von Oertzen T, Li S-C, Lindenberger U. Electrophysiological correlates of selective attention: A lifespan comparison. BMC Neuroscience. 2008;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milovanov R, Huotilainen M, Esquef PA, Alku P, Välimäki V, Tervaniemi M. The role of musical aptitude and language skills in preattentive duration processing in school-aged children. Neuroscience letters. 2009;460:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Bialystok E, Barac R, Schellenberg EG, Cepeda NJ, Chau T. Short-term music training enhances verbal intelligence and executive function. Psychological Science. 2011;22:1425–1433. doi: 10.1177/0956797611416999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Bidelman GM. Examining neural plasticity and cognitive benefit through the unique lens of musical training. Hearing Research. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R, Paavilainen P, Rinne T, Alho K. The mismatch negativity (MMN) in basic research of central auditory processing: A review. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;118:2544–2590. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostenveld R, Praamstra P. The five percent electrode system for high-resolution EEG and ERP measurements. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2001;112:713–719. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen KJ, Brattico E, Bailey CJ, Korvenoja A, Koivisto J, Gjedde A, Carlson S. Cognitive control in auditory working memory is enhanced in musicians. PLoSONE. 2010;5:e11120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parbery-Clark A, Anderson S, Hittner E, Kraus N. Musical experience offsets age-related delays in neural timing. Neurobiology of aging. 2012;33:1483. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.12.015. e1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AD. Why would musical training benefit the neural encoding of speech? The OPERA hypothesis. Frontiers in psychology. 2011;2 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putkinen V, Niinikuru R, Lipsanen J, Tervaniemi M, Huotilainen M. Fast measurement of auditory event-related potential profiles in 2–3-year-olds. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2012a;37:51–75. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2011.615873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putkinen V, Tervaniemi M, Huotilainen M. Informal musical activities are linked to auditory discrimination and attention in 2–3-year-old children: An event-related potential study. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2012b;37:654–661. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putkinen V, Tervaniemi M, Saarikivi K, de Vent N, Huotilainen M. Investigating the effects of musical training on functional brain development with a novel Melodic MMN paradigm. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2014;110:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recanzone GH, Schreiner CE, Merzenich MM. Plasticity in the frequency representation of primary auditory-cortex following discrimination-training in adult owl monkeys. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:87–103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00087.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke SK, He Y, Wang C, Alain C. Perceptual learning modulates sensory evoked response during vowel segregation. Cognitive Brain Research. 2003;17:781–791. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(03)00202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AF, Pessoa L, Desimone R, Ungerleider LG. The prefrontal cortex and the executive control of attention. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;192:489–497. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1642-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaug G, Forgeard M, Zhu L, Norton A, Norton A, Winner E. Training-induced neuroplasticity in young children. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1169:205–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaug G, Marchina S, Norton A. From singing to speaking: Why singing may lead to recovery of expressive language function in patients with Broca's aphasia. Music Perception. 2008;25:315. doi: 10.1525/MP.2008.25.4.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shestakova A, Huotilainen M, Cheour M. Event-related potentials associated with second language learning in children. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2003;114:1507–1512. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slevc LR. Language and music: Sound, structure, and meaning. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2012;3:483–492. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strait D, Kraus N. Playing music for a smarter ear: Cognitive, perceptual and neurobiological evidence. Music Perception. 2011;29:133–146. doi: 10.1525/MP.2011.29.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Holland SK, Schmithorst VJ, Byars AW. fMRI study of language lateralization in children and adults. Human brain mapping. 2006;27:202–212. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telkemeyer S, Rossi S, Koch SP, Nierhaus T, Steinbrink J, Poeppel D, Wartenburger I. Sensitivity of newborn auditory cortex to the temporal structure of sounds. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:14726–14733. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1246-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay K, Kraus N, McGee T, Ponton C, Otis B. Central auditory plasticity: Changes in the N1-P2 complex after speechsound training. Ear and Hearing. 2001;22:79–90. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200104000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan CY, Schlaug G. Music Making as a Tool for Promoting Brain Plasticity across the Life Span. The Neuroscientist. 2010;16:566–577. doi: 10.1177/1073858410377805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel N, Widmann A, Berti S, Schröger E. The development of involuntary and voluntary attention from childhood to adulthood: A combined behavioral and event-related potential study. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2006;117:2191–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.06.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanto TP, Rubens MT, Thangavel A, Gazzaley A. Causal role of the prefrontal cortex in top-down modulation of visual processing and working memory. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:656–661. doi: 10.1038/nn.2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, de Villers-Sidani É, Panizzutti R, Merzenich MM. Successive-signal biasing for a learned sound sequence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:14839–14844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009433107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.