Abstract

Insecure attachment and behavioral inhibition (BI) increase risk for internalizing problems, but few longitudinal studies have examined their interaction in predicting adolescent anxiety. This study included 165 adolescents (ages 14-17 years) selected based on their reactivity to novelty at 4 months. Infant attachment was assessed with the Strange Situation. Multi-method BI assessments were conducted across childhood. Adolescents and their parents independently reported on anxiety. The interaction of attachment and BI significantly predicted adolescent anxiety symptoms, such that BI and anxiety were only associated among adolescents with histories of insecure attachment. Exploratory analyses revealed that this effect was driven by insecure-resistant attachment and that the association between BI and social anxiety was significant only for insecure males. Clinical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Attachment, behavioral inhibition, adolescent anxiety

Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychiatric problems seen in children and adolescents, with prevalence estimates ranging from 5.7% to 17.7% (Costello & Angold, 1995). Poor quality of parent-child attachment has long been theorized to have lasting adverse effects on child adjustment, including increased risk for the development of psychopathology generally, and anxiety disorders specifically (Bowlby, 1973; Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005). Behavioral inhibition (BI) refers to a predisposition or temperament, characterized by consistently responding to unfamiliar situations, objects, and people with negative emotion and withdrawal (Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, 2005; Kagan, 1997). BI occurs in approximately 15-20% of children and has been identified as one of the most reliable individual-level early predictors of anxiety disorders (Clauss & Blackford, 2012). While there is evidence for associations between temperamental reactivity and attachment classification in infancy (Marshall & Fox, 2005), as well as infant attachment classifications predicting BI in toddlerhood (Calkins & Fox, 1992), few studies have prospectively examined direct and interactive effects of insecure attachment and BI together in predicting adolescent anxiety.

Attachment theory suggests that infants have a need for social contact and proximity and that a corresponding behavioral system supports the fulfillment of this need (Bowlby, 1969). This system promotes the infant's development of an attachment to a caregiver, though the type of attachment formed depends on the quality of daily caregiving that is experienced within the caregiver-child relationship. Based on behavior displayed during Strange Situation Procedure (SSP; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978), most infants (i.e., approximately 61 - 65% in normative samples world-wide; van IJzendoorn, 1995; van IJzendoorn & Kroonenberg, 1988) can be classified as showing a secure attachment. Infant behaviors observed during the SSP are thought to reflect the quality of the caregiver-child relationship (Bretherton, 1992). Securely attached infants display a pattern of behavior during the SSP in which they comfortably explore their surroundings when the caregiver is present and effectively relieve distress when reunited with the caregiver following separation. Thus, the caregiver supports effective emotion regulation, establishing the foundation for further social and emotional development (Cassidy, 1994).

In contrast, insecure attachment refers to three distinct patterns of infant behavior observed during the SSP (Ainsworth et al., 1978). These include infants who ignore or avoid contact with their caregiver following separation (“insecure-avoidant”); who seek proximity and physical contact with their parent, but also show angry behaviors and are unable to effectively modulate their distress when reunited (“insecure-resistant” or “insecure-ambivalent”); or who show anomalous or fearful behaviors upon reunion, suggesting a breakdown in the attachment system (“insecure-disorganized”; Main & Solomon, 1986).

Recent meta-analyses indicate that insecure attachment in infancy is a non-specific risk factor for psychopathology, predicting both internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Lapsley, & Roisman, 2010; Groh, Roisman, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Fearon, 2012). In two recent meta-analyses, Groh and colleagues (2012) and Madigan and colleagues (2013) reported significant though modest (d = 0.15 and d = .37, respectively) associations between insecure attachment and internalizing symptoms. In a meta-analysis examining insecure attachment and externalizing behavior, Fearon and colleagues (2010) also reported a modest, significant effect for the association between insecure attachment and externalizing symptoms (d = 0.31). These results may suggest that divergent developmental pathways emerge over time among children who form insecure attachments to caregivers in infancy, including both internalizing and externalizing outcomes. Prior studies have reported high correlations between internalizing and externalizing problems in childhood (ranging from 0.66 to 0.72), suggesting considerable co-occurrence of disorders across these domains (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Lahey et al., 2004). Thus, it could be that this co-morbidity accounts for insecure attachment predicting both outcomes.

Childhood BI appears to be a relatively specific early risk factor that is associated with more than sevenfold increased risk of social anxiety disorder (SAD; Clauss & Blackford, 2012). In a recent meta-analysis, Clauss and Blackford (2012) reported that 43% of children with childhood BI met criteria for SAD at follow-up assessments, compared to only 12% of non-inhibited children. Further, studies including multiple childhood assessments of BI across time suggest greater risk of anxiety, and particularly SAD, among adolescents with histories of consistently high BI (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Essex, Klein, Slattery, Goldsmith, & Kalin, 2010). For instance, Chronis-Tuscano and colleagues (2009) reported that the presence of consistently high BI increased the risk of lifetime SAD two-fold by adolescence (OR = 1.98). Essex and colleagues (2010) found rates of SAD as high as 50% among 14-year-olds with histories of chronic high BI, relative to rates of 27% and 5% in those with histories of less chronic BI (i.e., a “middle-high” and “middle” BI group, respectively) and to rates of 0% in low-middle and chronic low BI groups.

Though BI is a primary early risk factor for SAD (Clauss & Blackford, 2012), it may not be sufficient for the development of SAD or other anxiety disorders. That is, most children with the temperament of BI across early childhood do not develop anxiety disorders, and many children with anxiety disorders do not have histories of consistently high BI (Degnan & Fox, 2007). This highlights the importance of examining other factors that may alter the trajectories of children within this temperamental group either toward or away from developing anxiety disorders. Though relatively understudied, such moderation effects have been reported (Degnan, Almas, & Fox, 2010). For instance, consistently high BI has been found to predict adolescent SAD only in the presence of maternal over-control (Lewis-Morrarty et al., 2012) or certain cognitive or attention biases (e.g., Pérez-Edgar et al., 2010). Therefore, further research is needed to identify moderating factors that increase risk for anxiety disorders, particularly SAD, among children with consistent high BI.

Results of empirical studies investigating both insecure attachment and BI as predictors of childhood anxiety suggest that both risk factors are independently associated with concurrent child anxiety during the preschool (e.g., Manassis, Bradley, Goldberg, & Hood, 1995; Shamir-Essakow, Ungerer, & Rapee, 2005) and middle school periods (e.g., van Brakel, Muris, Bögels, & Thomassen, 2006). However, methodological limitations of these studies include cross-sectional research design (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010; Manassis et al., 1995; Shamir-Essakow et al., 2005; van Brakel et al., 2006), small sample sizes (e.g., N = 20; Manassis et al., 1995), assessment of BI from the child's behavior during the SSP (Stevenson-Hinde, Shouldice, & Chicot, 2011), or the reliance on self-, parent-, or retrospective-report of constructs (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010; van Brakel et al, 2006).

Despite a strong theoretical foundation, few empirical studies have examined the interaction of attachment and BI together in predicting childhood anxiety. However, one prior study using the current sample reported that infants classified as insecure-avoidant during the SSP at age 14 months had a higher incidence of parent-rated externalizing behavior problems at age 4 years, relative to those classified as secure or insecure-resistant (Burgess, Marshall, Rubin, & Fox, 2003). There was also an interaction effect such that the combination of insecure-avoidant attachment and uninhibited temperament predicted a higher incidence of externalizing behavior problems at age 4 years. Interestingly, the hypothesis that the combination of insecure-resistant attachment and BI would predict internalizing problems through age 4 was not supported. The authors speculated that it may have been too early to detect internalizing problems, and that such difficulties might be expected to emerge in later childhood and adolescence. Therefore, longitudinal follow-up of this sample into adolescence is warranted.

However, Warren and colleagues (1997) reported that insecure-resistant attachment in infancy predicted anxiety disorders at age 17 (N = 172), when controlling for both maternal anxiety and infant temperament (Warren, Huston, Egeland, & Sroufe, 1997). Of note, only direct effects of the independent variables were examined in predicting adolescent anxiety, and not interactive effects. Additionally, temperament was assessed within the first 10 days of life via nurse and observer ratings, rather than using a standardized laboratory paradigm (e.g., Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1988). Thus, very few longitudinal studies have investigated interactive effects of attachment and BI in predicting the development of anxiety into adolescence.

Early variations in parental care may explain why resistant attachment and BI confer the greatest risk for adolescent anxiety. Mothers of infants classified as insecure-resistant have been observed to be the least consistently available and the least competent in providing comfort in response to distress, relative to other mothers (Cassidy & Berlin, 1994). They also show a greater tendency than other mothers to directly interfere with their infants’ exploration (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Cassidy & Berlin, 1994). Interestingly, parenting characterized by overly involved or overly directive behaviors (i.e., “oversolicitousness”) has also been associated with BI (Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009) and with childhood and adolescent anxiety, generally (d = .58), and more specifically with social anxiety (d = .76; van der Bruggen, Stams, & Bögels, 2008). Such quality of maternal care may serve as a key environmental connection between insecure attachment, BI, and the development of anxiety.

As discussed in a recent review by Doey and colleagues (2013), across different methodologies, there has been limited evidence of gender differences in the occurrence of BI and shyness across early to middle childhood. However, there is growing evidence to suggest that the psychosocial consequences of consistent high BI and shyness may be greater for boys than for girls, perhaps because shyness in boys is less socially acceptable than it is in girls, particularly when BI persists over time (Doey, Coplan, & Kingsbury, 2013). For example, stronger associations between shyness and a multitude of negative outcomes have been found for boys relative to girls, including peer exclusion, social rejection, anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and difficulties adjusting to adulthood (e.g., Caspi, Elder, & Bem, 1988; Coplan et al., 2007; Spangler & Gazelle, 2009). Despite this mounting evidence, not all prior studies have reported that boys with BI or shyness are at greater risk of internalizing problems. For example, of particular relevance to the present study, Schwartz and colleagues (1999) found a stronger association between BI and social anxiety for girls than for boys. Thus, influences of child gender on the development of anxiety among children with BI or shyness have been somewhat mixed and require further investigation. Similarly, there have not been longitudinal studies examining gender differences in attachment classifications or interactions between child gender and attachment security in predicting adolescent anxiety.

To our knowledge, no prospective longitudinal studies have examined insecure attachment and consistently high BI together, as predictors of anxiety during adolescence. In particular, social anxiety (SA) symptoms and SAD are important outcomes to evaluate, given that BI has been found to predict increased rates of SAD (Clauss & Blackford, 2012). The present study therefore aims to address these gaps in the prior research literature. We hypothesized that infant attachment would moderate the association between consistently high BI and adolescent anxiety, such that BI would be a better predictor of anxiety for adolescents with histories of insecure attachment than it would for those who had been securely attached. We speculated that direct or interactive effects between consistent BI, insecure attachment, and anxiety might be stronger for males, relative to females, considering findings suggesting that consistent shyness is associated with poorer long-term outcomes among males than females. However, given inconsistent findings reported in the prior literature, and limited research concerning gender differences in attachment classifications, we considered examination of interactions of attachment and BI with child gender to be exploratory.

Method

Participants

The present study included adolescents who were selected based on their reactivity to novel auditory and visual stimuli at age 4 months and followed longitudinally as part of a larger study (Fox, Henderson, Rubin, Calkins, & Schmidt, 2001). Initially, recruitment mailings were sent to families ascertained from the birth records of local hospitals, asking that parents return a survey indicating whether their child: was born full-term and normally developing; had not experienced any serious birth complications; and whether parents were right-handed (to address aims of the larger study). Of the infants who met study inclusion criteria, 443 were assessed through standardized laboratory paradigms of reactivity to novel stimuli at age 4 months (See Fox et al., 2001). Based on these assessments, 178 infants (92 female, 86 male) were followed into adolescence, with 37% showing high negative and high motor reactivity in response to novel stimuli, 29% showing high positive and high motor reactivity, and 34% showing low reactivity. All participants were European-American and initially from two-parent, middle-to-upper class families. Mothers had completed high school (28%), college (49%), or graduate school (11%), with the remainder having listed their educational attainment as “other” (12%).

The present analyses include 165 adolescents (83 female, 82 male) ranging in age from 14 to 17 years (M = 15.05, SD = 1.82) who provided observational i or maternal report BI data at one or more timepoints across early childhood (at 14 months, 24 months, 4 years , 7 years). Of these, 143 (86.7% of those with BI data) participated in the SSP at age 14 months and 113 (68.5% of those with BI data) completed anxiety questionnaires in adolescence. Missing data patterns across child gender, attachment, BI, and anxiety measures did not violate the assumption that data were missing completely at random (MCAR; Little & Rubin, 1987), Little's MCAR average χ2 = 3.20, p's > .25.

Measures

Infant attachment

The SSP is considered the gold standard measure of infant attachment (Ainsworth et al., 1978). It is a 24-minute standardized laboratory observation consisting of eight 3-minute segments. Two of these involve separation episodes, during which the parent leaves the room, followed by reunion episodes during which the infant's behavior is coded for quality of attachment upon the parent's return. The SSP is intended to activate the infant's attachment system through exposure to an increasingly threatening situation. That is, the SSP takes place in an unfamiliar room with novel toys, and the infant meets an unfamiliar adult with whom he or she is first left alone, and later he or she is left completely alone in the room.

Infants were classified as secure (B), insecure-avoidant (A), or insecure-resistant (C) based on their behavior during SSP reunion episodes, in accordance with the coding procedures outlined by Ainsworth (1978). As previously reported (Bar-Haim, Sutton, Fox, & Marvin, 2000; Burgess et al., 2003; Marshall & Fox, 2005), coding was completed by raters who had achieved reliability with an attachment researcher, who had completed extensive training and passed a reliability test with expert coders. A randomly selected 25% of SSP cases were triple-coded with the attachment researcher, and an additional 25% were double-coded. Inter-rater reliability was satisfactory between coders (κ's > .75), and any differences were resolved through discussion and mutual agreement.

Behavioral inhibition

At 14 and 24 months, infants’ reactions to an unfamiliar room, mechanical robot, and adult stranger during a standardized laboratory procedure were coded to provide an index of BI (Fox et al., 2001). At 24 months, the procedure also included asking children to crawl through a pop-up tunnel. Child behavior during these tasks was coded in seconds for behaviors such as latency to touch a toy or approach the stranger, latency to vocalize, and proportion of time spent in proximity to the mother. A composite index of BI at each age was computed by summing standardized reaction scores to these novel stimuli, with higher scores indicating greater BI. At 14 and 24 months, inter-rater reliability was adequate based on intraclass correlations calculated from 15% (ICC's ranged from 0.85 to 1.00) and 24% (ICC's ranged from 0.77 to 0.97) of the sample, respectively.

Parent ratings of child BI at 14 and 24 months were based on the 19-item Social Fearfulness (SF) scale (α = .87) of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ; Goldsmith, 1996), on which parents rate the frequency of child behaviors occurring within the past month. The SF scale includes items assessing child inhibition, distress, withdrawal, and shyness, with higher scores indicating greater BI (e.g., “When he or she saw other children while in the park or playground, how often did your child approach and immediately join in play?”).

At ages 4 and 7, children were observed during a same-age, same-sex free-play session in which 4 unfamiliar children were left alone together in the playroom for 15 minutes with age-appropriate toys while their mothers remained in a waiting area (Fox et al., 2001). Each playgroup consisted of one child who exhibited high BI in the laboratory at the previous visit (one-half standard deviation or more above the mean), one child who exhibited very low BI in the previous laboratory visit (one-half standard deviation or more below the mean), and two average children (within one standard deviation of the mean). Child behaviors fitting two categories from the Play Observation Scale (POS; Rubin, 2001) were coded in 10-second segments: Onlooking behavior, defined as “the child observes the other children's activities without attempting to play,” and Unoccupied behavior, defined as “the child demonstrates an absence of focus or intent.” Higher scores indicated a greater proportion of BI. Three independent coders double-coded 30% of the cases at age 4 and 7 years, and inter-rater reliability estimates were adequate (κ's ranging from 0.71 to 0.86 at 4 years; 0.84 to 0.88 at 7 years).

At 4 and 7 years, parents completed the Shyness and Sociability subscale of the Colorado Children's Temperament Inventory (CCTI; Rowe & Plomin, 1977). This scale includes 5 items rated from 1-5, such as “child tends to be shy” or “child takes a long time to warm up to strangers,” (α = .88), with higher scores indicating greater BI.

Longitudinal BI profiles

To create a comprehensive, single BI variable incorporating all eight measures of BI collected across the four time points, BI profiles were created using Latent Class Analysis (LCA) performed in Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2011). This analysis yielded continuous probability scores reflecting the likelihood of each individual to consistently display high BI over time (Lewis-Morrarty et al., 2012). The LCA included continuous measures of observed BI and parent report of BI at the four time points (i.e., a total of 8 measures), to estimate probability of BI class membership. To account for our use of different BI measures over time, a sub-type of LCA, Latent Profile Analysis (LPA; Gibson, 1959), was performed, which estimates the average level of BI at each age independently within each class or profile. Models with 2 through 4 profiles were estimated. Best model fit was assessed using Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), where the smallest number indicates best fit, and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood ratio test (LMRL), which tests the significance of the −2 Log likelihood difference between models with k and k-1 profiles (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001).

The LPA utilized all 165 participants who provided BI data at any of the assessments, as the data did not violate missing data assumptions, Little's MCAR χ2 (180) = 192.86, p = .24. The 2-profile model was chosen as the best-fitting model because a low BIC and a significant LMRL occurred for this model relative to the others (See Lewis-Morrarty et al., 2012, for more details). The high BI profile represented high average levels of BI at all four study time points and 15% of the sample (n = 25) had a higher probability of membership in this profile than the other profile. The “low” profile represented lower levels of BI at all four time points and 85% of the sample (n = 140) had a higher probability of membership in this profile than the other profile. In the current study, the continuous individual probabilities of membership in the high BI profile were used as the consistently high BI variable in all subsequent analyses (M = 0.16, SD = 0.34).

Adolescent anxiety

When participants were ages 14-17 years, they and their parents independently completed the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1999). Consistent with the clinical standards in assessing childhood psychopathology, we examined both adolescent- and parent-reported anxiety symptoms in order to retain important information gained from each informant separately (De Los Reyes, Thomas, Goodman, & Kundey, 2013). The SCARED is a 41-item psychometrically-sound measure of child and adolescent anxiety that asks informants to rate items on a 3-point scale (0 = not true or hardly ever true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very true or very often true). The SCARED generates a total anxiety (TA) score (SCARED-TA; adolescent: α = .93, parent: α = .94), which is comprised of scores on five subscales: Panic Disorder or Significant Somatic Symptoms, Generalized Anxiety, Separation Anxiety, Social Anxiety, and Significant School Avoidance. We also examined the adolescent- and parent-report versions of the SCARED Social Anxiety subscale (SCARED-SA; adolescent: α = .74, parent: α = .83). The SCARED-SA scale includes items such as, “I feel nervous when I am with other children or adults and I have to do something while they watch me like read aloud, speak, play a game, or play a sport,” and, “I feel nervous when I am going to parties, dances, or any place where there will be people I don't know well.” Higher scores on the SCARED-SA scale indicate greater SA symptoms.

To assess anxiety diagnoses, 124 (75.2%) of the 165 adolescents and their parents were administered the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997), which included supplemental questions from the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (ADISC; Silverman & Albano, 1996). Interviews were conducted separately with parents and with adolescents to obtain independent ratings of symptoms. Any discrepancies were discussed with the parent and adolescent together to clarify the presence or absence of a disorder. Interviews were conducted by advanced clinical psychology doctoral students under the supervision of a licensed clinical psychologist and a board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist, all of whom were blind to temperament, attachment, and SCARED data. Audiotapes of 59 interviews (47.6%) were reviewed for reliability, and interviewer agreement with expert clinicians was high for anxiety diagnoses (κ = .92).

Data Analytic Plan

We first examined direct and interactive associations between attachment (i.e., two-group comparison; secure vs. insecure) and BI in predicting adolescent total anxiety (TA) and social anxiety (SA) symptoms. We examined the adolescent- and parent-report SCARED scales independently due to the likelihood of informant discrepancies (De Los Reyes et al., 2013) and (given that the BI variable was partially based on maternal-report) to reduce the potential effects of shared method variance. We were also interested in exploring whether child gender moderated associations between BI, attachment, and anxiety; thus, child gender was included in our main analyses. Second, we examined the interaction between attachment and BI in predicting anxiety diagnoses. Third, we compared associations between BI and anxiety symptoms among adolescents with histories of insecure-avoidant and insecure-resistant attachment, relative to those who had been securely attached.

Linear and logistic regression models were tested in an SEM framework with Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) for all participants with data on one or more variables using Mplus. This analysis estimates the log likelihood of each model for the outcome measure (anxiety symptoms or disorder), conditional on the covariates (gender, attachment, BI, gender × attachment, gender × BI, attachment × BI, gender × attachment × BI). Similar to traditional regression analysis, all covariates were assumed to be correlated. Means and variances of all continuous covariates were estimated in the model to allow for missing data among these measures. Prior to these analyses, the continuous BI variable was mean-centered and dichotomous predictors (i.e., gender and attachment) were dichotomized as 0 and 1. Interactions were computed as the product of the mean-centered (i.e., BI) and dichotomous (i.e., gender and attachment) variables. Anxiety symptoms were continuous variables, whereas anxiety diagnoses were categorical variables.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the main study variables. The two-way distribution of infant attachment classifications for the sample was: 59.4% secure (n = 85) and 40.6% insecure (n = 58). Among those classified as insecurely attached, 25 were insecure-avoidant (17.5%) and 33 were insecure-resistant (23.1%). Secure and insecure infants did not differ significantly in terms of BI probability scores, F(1, 142) = 1.42, p = .24, nor did the proportion of secure vs. insecure infants differ significantly according to child gender, χ2(1, N = 143) = 2.92, p = .09. However, insecure-resistant attachment was significantly associated with 14-month observed BI, such that infants with insecure-resistant attachment patterns showed higher observed BI at 14 months, t(143) = 2.95, p = .01. Additionally, secure attachment was negatively associated with observed BI at 24 months, t(143) = −2.09, p = .04. No other associations between attachment and BI or SCARED scores were statistically significant, p's > .05, and no significant associations between attachment and anxiety diagnoses were found.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics on Main Study Variables

| Measure | N | Min. | Max. | M | SD | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (0 male; 1 female) | 165 | 0.00 | 1.00 | .50 | .50 | −0.01 |

| Observed BI | ||||||

| 14 Months | 142 | −8.90 | 16.75 | 0.00 | 5.07 | 1.08 |

| 24 Months | 150 | −8.07 | 11.52 | 0.00 | 4.32 | 0.44 |

| 4 Years | 137 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 1.98 |

| 7 Years | 115 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 2.95 |

| Parent-reported BI | ||||||

| 14 Months | 139 | 1.63 | 6.40 | 3.88 | 0.83 | 0.30 |

| 24 Months | 133 | 2.00 | 6.21 | 4.09 | 0.95 | 0.28 |

| 4 Years | 133 | 1.00 | 4.80 | 2.54 | 0.84 | 0.35 |

| 7 Years | 116 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 2.24 | 0.76 | 0.35 |

| BI probability | 165 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 1.94 |

| Attachment security (0 secure; 1 insecure) | 143 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.39 |

| SCARED-SA | ||||||

| Adolescent-report | 113 | 0.00 | 13.00 | 3.80 | 3.34 | 0.62 |

| Parent-report | 113 | 0.00 | 14.00 | 3.84 | 3.75 | 0.90 |

| SCARED-TA | ||||||

| Adolescent-report | 113 | 0.00 | 50.00 | 14.52 | 11.37 | 0.90 |

| Parent-report | 113 | 0.00 | 47.00 | 10.81 | 10.01 | 1.16 |

Note. BI = Behavioral Inhibition; SCARED = Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorder

Table 2 presents bivariate correlations among the individual BI measures and adolescent SCARED scores. As shown in Table 2, there were significant associations between parent-reported BI at 4 and 7 years and the adolescent SCARED scores, with r's ranging from .18 to .38. There was also a significant gender difference in BI, such that males had significantly higher BI probability scores than females, F(1, 164) = 4.68, p = .03. Bivariate correlations between the adolescent- and parent-reported SCARED scores ranged from 0.38 and 0.78, p's < .05, with stronger correlations between scales reported on by the same, relative to different, informant(s).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Observed BI – 14 mo. | .41*** | .28*** | .13 | .23** | .34*** | .22* | .19* | .01 | −.05 | .09 | .00 | .05 |

| 2. Observed BI – 24 mo. | -- | .38*** | .23* | .18* | .36*** | .30*** | .33** | .04 | −.05 | .00 | −.04 | −.12 |

| 3. Observed BI – 4 years | -- | .26** | .32*** | .39*** | .48*** | .39*** | −.05 | −.06 | .03 | .08 | −.03 | |

| 4. Observed BI – 7 years | -- | .04 | −.02 | .30*** | .27** | .17 | .11 | .09 | .03 | −.09 | ||

| 5. Parent-report BI – 14 mo. | -- | .32*** | .16 | .22** | −.05 | −.03 | −.05 | −.00 | −.02 | |||

| 6. Parent-report BI – 24 mo. | -- | .37*** | .36*** | .13 | .05 | .17 | .07 | −.01 | ||||

| 7. Parent-report BI – 4 years | -- | .74*** | .18* | .14 | .28** | .17 | .02 | |||||

| 8. Parent-report BI – 7 years | -- | .24* | .15 | .38*** | .27* | .03 | ||||||

| 9. Adolescent-report SCARED-SA | -- | .78*** | .47*** | .54*** | −.02 | |||||||

| 10. Adolescent-report SCARED-TA | -- | .38*** | .69*** | .05 | ||||||||

| 11. Parent-report SCARED-SA | -- | .73*** | .11 | |||||||||

| 12. Parent-report SCARED-TA | -- | .17 | ||||||||||

| 13. Attachment Security | -- |

Note. BI = Behavioral Inhibition. SCARED-SA = SCARED Social Anxiety. SCARED-TA = SCARED Total Anxiety. Attachment Security = 0 secure, 1 insecure.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

(N = 165)

Insecure Attachment × BI Predicting Adolescent Total Anxiety Symptoms

Results from the models predicting adolescent- and parent-reported SCARED-TA symptoms from child gender, attachment, and BI are presented in Table 3. In the model predicting adolescent-reported TA symptoms, there were no significant main effects of gender (0 = male; 1 = female), attachment (0 = secure; 1 = insecure), or BI, p's > .05. However, the 2-way interaction between attachment and BI was significant, p < .01. The 3-way interaction was only marginally significant, p = .09, and was not probed further.

Table 3.

Predicting Adolescent Anxiety From Child Gender, Attachment, and Behavioral Inhibition

| Adolescent-report | Total Anxiety | Social Anxiety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | B | SE B | β | |

| Gender | 4.17 | 2.94 | 0.18 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.14 |

| Attachment (Att.) | 1.15 | 3.54 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 1.03 | −0.01 |

| BI | −2.66 | 4.34 | −0.08 | −0.75 | 1.21 | −0.07 |

| Gender × Att. | −1.89 | 4.86 | −0.07 | −1.16 | 1.41 | −0.14 |

| Gender × BI | 5.00 | 11.04 | 0.09 | 5.95 | 3.20 | 0.34 τ |

| Attach. × BI | 34.72 | 12.40 | 0.56** | 12.41 | 3.55 | 0.67** |

| Gend. × Att. × BI | −31.33 | 19.07 | −0.40τ | −15.75 | 5.47 | −0.68** |

| Total R2 | .14τ | .19 | ||||

| Parent-report | Total Anxiety | Social Anxiety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | B | SE B | B | |

| Gender | 0.05 | 2.73 | 0.00 | −0.85 | 1.00 | −0.11 |

| Attachment (Att.) | 6.88 | 3.16 | 0.33* | 0.75 | 1.17 | 0.10 |

| BI | 3.14 | 3.84 | 0.10 | −0.22 | 1.40 | −0.02 |

| Gender × Att. | −4.75 | 4.66 | −0.20 | −0.57 | 1.70 | −0.06 |

| Gender × BI | 0.18 | 10.25 | 0.00 | 6.36 | 3.71 | 0.33 τ |

| Att. × BI | 19.24 | 11.27 | 0.35τ | 9.93 | 4.13 | 0.48* |

| Gend. × Att. × BI | −19.93 | 20.48 | −0.29 | −17.12 | 7.40 | −0.66* |

| Total R2 | .11 | .14τ | ||||

Note: As reported on the SCARED-TA and SCARED-SA scales (N = 165). BI = Behavioral Inhibition; Gender = 0 Male, 1 Female; Attachment = 0 Secure Attachment, 1 = Insecure Attachment.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

As recommended by Aiken and West (1991), to examine the significant 2-way interaction between attachment and BI in predicting adolescent-reported TA, the effect of BI on TA was examined among adolescents classified as securely attached as infants compared to those classified as insecurely attached. Among adolescents with histories of secure attachment, BI was not associated with adolescent-reported TA, p = .54, whereas this association was positive and significant for adolescents with histories of insecure attachment, p = .01.

In the model predicting parent-reported TA symptoms, a significant main effect of attachment emerged, such that adolescents with histories of insecure attachment were rated as more anxious by their parents than those with histories of secure attachments, p = .03. No other significant effects emerged. The 2-way interaction between attachment and BI was only marginally significant in predicting parent-reported TA, p = .08, and was not probed further.

Insecure Attachment × BI Predicting Adolescent Social Anxiety Symptoms

Results of the models predicting adolescent- and parent-reported SCARED SA symptoms are presented in Table 3. Results of the separate models predicting adolescent- and parent-reported SA revealed no significant main effects, p's > .05. However, the 2-way interaction between attachment and BI significantly predicted adolescent-reported SA, p < .01, as well as parent-reported SA, p = .02. Additionally, the 3-way interaction between gender, attachment, and BI also significantly predicted adolescent-reported SA, p < .01, and parent-reported SA, p = .02.

In the models predicting adolescent- and parent-reported SA symptoms, the significant attachment by BI interaction followed the same pattern as described above for adolescent-reported TA symptoms. Specifically, among adolescents who had been securely attached, BI was not significantly associated with adolescent-reported SA, p = .54, or parent-reported SA, p = .88. However, among those who had been insecurely attached, BI was positively and significantly associated with both adolescent-reported SA, p < .01, and parent-reported SA, p = .01.

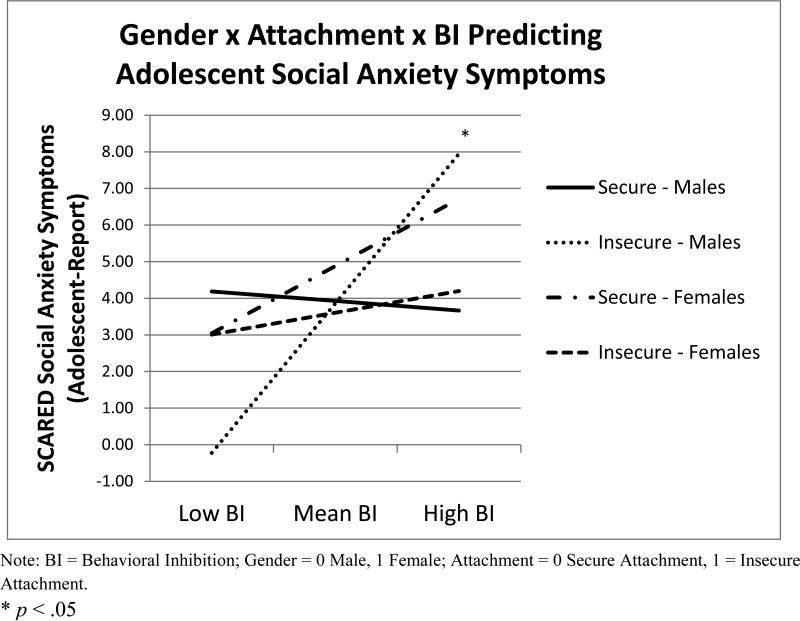

To examine the significant 3-way interaction, the effect of BI on SA symptoms was additionally examined with gender coded as 0 = female, 1 = male, and also with attachment coded as 0 = insecure, 1 = secure (Aiken & West, 1991). Results indicated that the association between BI and adolescent-reported SA was significant only among insecurely attached males, p < .01. Similarly, the association between BI and parent-reported SA was significant only for insecurely attached males, p = .01. The association between BI and SA symptoms (adolescent- or parent-report) was not significant among secure males or secure and insecure females, p's > .05 (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interaction of child gender, infant attachment, and consistently high BI predicting adolescent social anxiety symptoms (based on adolescent-report).

Insecure Attachment × BI Predicting Adolescent Anxiety Diagnoses

Next, the interaction of attachment and BI in predicting current and lifetime anxiety disorders and SAD were examined, with the anxiety diagnoses coded as 0 = not present, 1 = present. Given that diagnoses are dichotomous outcomes, limited power precluded our ability to examine gender interactions. However, we included child gender in these models as a covariate. None of the main or interaction effects in the models predicting lifetime and current anxiety disorder and lifetime SAD were statistically significant, p's > .05 (See Table 4). Results of the model predicting current SAD mirrored those of the models predicting adolescent- and parent-reported SA symptoms, but the attachment by BI interaction was only marginally significant in predicting current SAD, p = .06.

Table 4.

Predicting Adolescent Anxiety Disorder From Gender, Attachment, and BI

| Lifetime | Anxiety Disorder | Social Anxiety Disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | B | SE B | B | |

| Gender | −0.03 | 0.25 | −0.01 | −0.35 | 0.26 | −0.18 |

| Attachment | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.01 | −0.32 | 0.31 | −0.16 |

| BI | 0.75 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.51 | 0.03 |

| BI × Attachment | −0.67 | 1.16 | −0.12 | 1.01 | 1.11 | 0.18 |

| Total R2 | .05 | .11 | ||||

| Current | Anxiety Disorder | Social Anxiety Disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | B | SE B | B | |

| Gender | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.03 | −0.15 | 0.30 | −0.07 |

| Attachment | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.03 | −0.43 | 0.39 | −0.21 |

| BI | 0.02 | 0.51 | 0.01 | −0.56 | 0.60 | −0.19 |

| BI × Attachment | 0.26 | 1.12 | 0.05 | 2.09 | 1.10 | 0.38τ |

| Total R2 | .01 | .16τ | ||||

Note: As reported on the KSADS-PL (N = 165). BI = Behavioral Inhibition; Gender = 0 Male, 1 Female; Attachment = 0 Secure Attachment, 1 = Insecure Attachment.

p < .10

* p < .05

** p < .01

Insecure Attachment Types Predicting Adolescent Anxiety Symptoms

We were also interested in exploring whether the moderating effect of attachment on associations between BI and anxiety was driven by one specific type of insecure attachment. Thus, we separated the attachment variable into three groups including adolescents with histories of insecure-avoidant, insecure-resistant, and secure attachment patterns. The categorical nature of the data precluded our conducting this comparison in predicting anxiety diagnoses or in examining the interaction between child gender and insecure attachment type.

Results predicting adolescent TA symptoms revealed a significant attachment × BI interaction, p = .01, which was driven by those classified as insecure-resistant during infancy. Specifically, the attachment × BI interaction was significant for both adolescent-reported TA (p = .01) and parent-reported TA (p = .01), with significant positive associations between BI and TA emerging for adolescents with insecure-resistant attachment (p = .01, adolescent-report; p = .01, parent-report), but significant negative associations emerging between BI and TA for those with insecure-avoidant attachment (p = .03, adolescent-report; p = .01, parent-report). There were no significant associations between BI and TA for adolescents with histories of secure attachment (p = .90, adolescent-report; p = .47 parent-report).

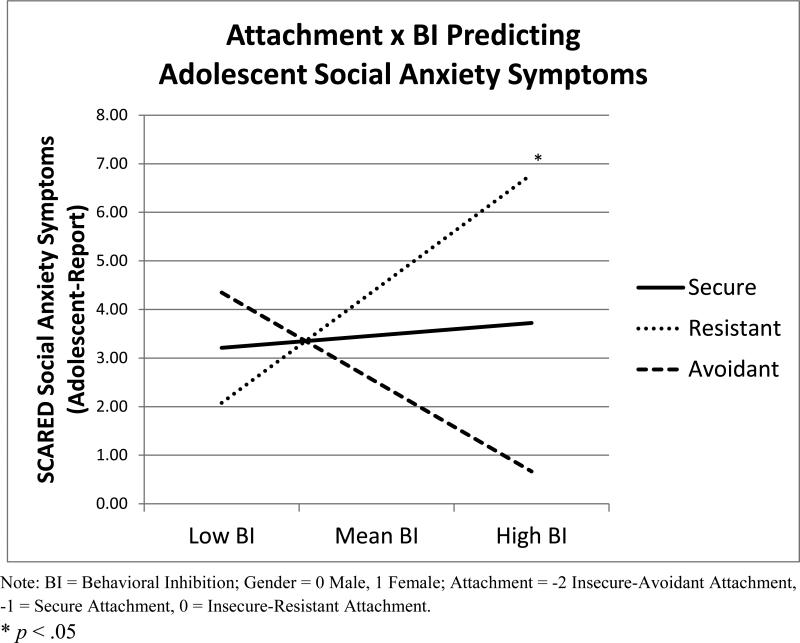

A similar pattern of results was found when predicting adolescent-reported SA symptoms (Figure 2). Among adolescents with insecure-resistant attachment, BI was positively and significantly associated with SA, p < .01; whereas BI was not significantly associated with SA among those with secure attachment, p = .46, and only marginally associated among those with insecure-avoidant attachment, p = .06. With regard to parent-reported SA, the attachment × BI interaction was only marginally significant, p = .05, and thus was not probed further.

Figure 2.

Interaction of infant attachment (secure, insecure-avoidant, and insecure-resistant) and consistently high BI predicting adolescent social anxiety symptoms (based on adolescent-report) with child gender included as a covariate.

Discussion

The present study uniquely contributes to the existing research literature by testing the interaction between insecure infant attachment and consistently high BI in childhood predicting adolescent anxiety. The prospective, longitudinal research design, observational measure of infant attachment, and multi–method assessments of BI over time all lend strength to the present conclusions. The overall hypothesis was supported, that the combination of insecure attachment and consistently high BI would significantly predict adolescent anxiety. We found a specific positive association between consistently high BI in childhood and adolescent anxiety symptoms only among those with insecure attachment in infancy. Thus, relative to each individual risk factor, the interaction between the quality of the early caregiver-child relationship and the child's vulnerability to distress predicted the greatest risk for anxiety in adolescence (Manassis & Bradley, 1994). Our main finding is consistent with a transactional model, which suggests that developmental outcomes (e.g., adolescent anxiety symptoms) are not solely the result of individual characteristics (e.g., child temperament) or solely the result of an individual's experience (e.g., attachment quality), but that outcomes are instead the result of the combination of individual and experiential factors (Mangelsdorf & Frosch, 2000).

Consistent with previously-reported findings from this sample (e.g., Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009), direct associations between consistently high BI and adolescent anxiety symptoms were not found when relying on a measure of BI which incorporated both behavioral observations and maternal report of BI over time. Additionally, we did not find evidence of a direct effect of early attachment on adolescent anxiety, with the exception of the model predicting parent-reported total anxiety symptoms. This finding is consistent with results of recent meta-analyses that reported small effect sizes for associations between insecure attachment and internalizing symptoms (Groh et al., 2012; Madigan et al., 2013). Though infant attachment insecurity and consistently high BI are both risk factors for anxiety, most children with the temperament of behavioral inhibition do not develop anxiety disorders (Degnan & Fox, 2007).

Though we tested models predicting the presence of anxiety disorders in adolescence, all main effects and interaction effects of these models were non-significant. Small effect sizes of the associations we were trying to detect coupled with the categorical nature of several of the variables included in our analyses (i.e., child gender, attachment, and anxiety disorders) likely resulted in reduced power to detect effects.

Our results also revealed that the attachment moderation effects we found were driven specifically by the insecure-resistant pattern of attachment. Only one prior longitudinal study prospectively examined adolescent anxiety as predicted by the specific infant attachment classifications and temperament (Warren et al., 1997). Consistent with our finding, Warren and colleagues (1997) reported that only insecure-resistant attachment predicted adolescent anxiety disorders when accounting for the contributions of temperament and maternal anxiety. The present study extends these findings by assessing BI comprehensively across multiple time points; examining adolescent SA and SAD, specifically; and testing interactive effects between the variables including child gender. Together, these studies provide evidence for a specific link from insecure-resistant attachment to adolescent anxiety.

Although results of recent meta-analyses suggest that infant insecure attachment is a non-specific risk factor for both internalizing and externalizing problems (Fearon et al., 2010; Groh et al., 2012; Madigan et al., 2013), Colonnesi and colleagues (2011) previously reported a slightly larger effect size for the association between insecure-resistant attachment and anxiety, r = .37, relative to the association between insecure attachment (overall) and anxiety, r = .30. Similarly, Brumariu and Kerns (2010) reported that insecure-resistant attachment, in particular, was associated with internalizing symptoms and anxiety; whereas insecure-avoidant attachment was not consistently associated with these outcomes. Thus, our results are fairly consistent with the prior research on the types of psychopathology associated with the specific insecure patterns.

The insecure-resistant attachment pattern was somewhat more prevalent in our sample than in unselected samples, relative to the insecure-avoidant pattern, even though there was no significant association between attachment security and the BI probability variable. Previous published findings from this sample indicated that high negative reactivity at age 4 months predicted a greater incidence of resistant infant behaviors during the SSP at age 14 months (e.g., crying, clinging, proximity-seeking), but not overall attachment security (Marshall & Fox, 2005). Further, in another study utilizing a subset of this sample, infants classified as insecure-resistant at 14 months displayed more inhibition during laboratory assessments of BI at 24 months than those classified as insecure-avoidant (Calkins & Fox, 1992). Though infant reactivity and BI influence infant behaviors that are observed during the SSP (i.e., whether avoidant or resistant behaviors), it is the overall organization or pattern of behavior that determines attachment security (Calkins & Fox, 1992; Mangelsdorf & Frosch, 2000; Marshall & Fox, 2005). That is, as would be expected, the proportion of infants classified as insecure-resistant was somewhat higher in our selected sample, compared to unselected samples, yet the majority (59.4%) of infants in the sample had been securely attached.

Upon examination of child gender differences, we additionally found that the association between consistently high BI and adolescent SA symptoms was specific to males with histories of insecure attachment, rather than females (regardless of their attachment histories). That is, our findings suggest that males are more susceptible than females to a trajectory toward adolescent SA when both consistently high BI and insecure attachment are present. This finding is congruent with past research reporting that consistently high BI is more strongly associated with negative social outcomes for boys than it is for girls (e.g., Caspi et al., 1988). In addition, previous work with this sample suggested that the continuity in BI may be seen more often in boys (Fox et al., 2001), although sample size prevented this finding from reaching statistical significance. As suggested by Doey et al. (2013), the cost of persistent shyness may be greater for boys than for girls in terms of psychosocial functioning, given that this behavior violates societal expectations to a greater extent when it occurs in males than in females.

Although attachment theory did not propose differential outcomes for insecure girls and boys and, therefore, few studies have examined attachment by gender interactions, there is some evidence to suggest that both emotion regulation and peer interaction strategies differ between insecure boys and insecure girls (Hazen, Jacobvitz, Higgins, Allen, & Jin, 2011; Turner, 1991). The nature of these gender differences in coping strategies and peer interaction styles may in turn place members of one gender at increased risk for psychopathology relative to the other. Indeed, Hazen and colleagues (2011) recently reported that insecure-disorganized boys were at greater risk than insecure-disorganized girls for social problems and for both internalizing and externalizing problems, as reported by parents and teachers. Though additional studies are needed, the results of the current study are consistent with the prior literature suggesting that males may be particularly vulnerable to developing psychopathology when both insecure attachment and persistent BI are present. Considering the exploratory nature of our hypothesis regarding gender effects, replication of the current findings is needed. If our findings related to child gender are replicated, further research should focus on clarifying the mechanisms that place insecure boys at greater risk for such outcomes than insecure girls.

A significant, negative association was found between consistently high BI and adolescent TA symptoms among adolescents with histories of insecure-avoidant attachment. This finding may reflect the organized, avoidant strategy of minimizing outward expression of distress. For instance, prior research has found that infants classified as insecure-avoidant do not display observable distress when separated from their mothers during the SSP, even though they show accelerated heart rates to the same degree as do securely attached infants (Spangler & Grossmann, 1993). That is, though the biobehavioral stress level is similar among secure and insecure-avoidant infants, the avoidant strategy involves dampening or holding back any overt expressions of distress. Expanding on this idea, earlier research on this sample found that the combination of insecure-avoidant attachment at 14 months and uninhibited temperament at 24 months predicted a more regulated autonomic profile at age 4 years (e.g., lower heart rate and higher respiratory sinus arrhythmia or RSA; Burgess et al., 2003). Thus, it could be that insecure-avoidant infants become less physiologically reactive to external stimuli over time, thereby reducing the need to express anxiety overtly. These ideas are consistent with the organized strategy of insecure-avoidant attachment, which is thought to develop when displays of infant distress are repeatedly met by rejecting parental behaviors (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Sroufe & Waters, 1977). However, we did not examine externalizing disorders in the present study and insecure-avoidant attachment might instead predict such outcomes.

On the other hand, though not considered optimal for healthy emotional development, the caregiving style associated with insecure-avoidant attachment may result in parents tending to ignore overly reactive child behaviors, thereby preventing parental reinforcement of the heightened behavioral reactivity that is characteristically shown by high BI children in unfamiliar situations. Ignoring overly fearful behaviors in anxiety-provoking situations, combined with providing positive attention and rewards for “brave” behaviors, is a component of effective treatments for BI and anxiety in young children (e.g., Kennedy, Rapee, & Edwards, 2009). Thus, the type of parental behavior associated with avoidant attachment may serve to decrease overly reactive, anxious behaviors in novel situations among young children with BI, thereby diminishing risk for SAD. Regardless, insecure-avoidant attachment has been found to predict less optimal outcomes in other domains of functioning, as reported in the prior literature (e.g., Carlson & Sroufe, 1995; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2006).

Though our findings are impressive considering the length of time between the measurement of predictor and outcome variables, our models at best account for only 19 percent of the variance in adolescent anxiety symptoms. Other important sources of variance likely include genetics, parenting, parent anxiety, peer relationships, and cognitive factors (e.g., attention bias to threat, internal working models; Vertue, 2003). Attachment theorists suggest a developmental pathway from infant insecure attachment to later emotion dysregulation and psychopathology, stating that early emotion regulation first occurs within the caregiver-child relationship (Cassidy, 1994; Sroufe, 1996). Thus, another potential mechanism linking insecure-resistant attachment, BI, and adolescent anxiety may be the development of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies among those with histories of insecure attachment (Esbjørn, Bender, Reinholdt-Dunne, Munck, & Ollendick, 2012). Further studies are needed to more clearly elucidate the mechanisms linking such early risk factors to the development of anxiety.

Our findings must be considered in light of several limitations. First, our sample was predominantly middle class, European American, and was initially selected for infant reactivity to novel stimuli during a laboratory assessment. Our results may not generalize to different or more diverse populations. Second, though our study is longitudinal, we did not have an early assessment of anxiety disorders prior to adolescence, and thus cannot say when exactly anxiety symptoms emerged relative to our measures of BI. Third, observational measures of parenting in infancy or toddlerhood as well as any measure of parental anxiety were not collected. Further, though BI was assessed based on multiple timepoints, attachment was assessed only at a single study timepoint. Thus, we could not directly test associations among parent anxiety, parenting behaviors, attachment, BI, and anxiety over time. Fourth, attachment coding for the sample occurred before there were well-developed training guidelines for assessing disorganized attachment. Thus, we were unable to examine outcomes associated with disorganized attachment. Future studies should aim to address these limitations by testing more complex, transactional models examining how the child and parent change over time as related to the development of psychopathology. Additionally, future studies should seek to replicate these findings in more demographically diverse samples.

Despite these limitations, the methodological and conceptual strengths of the study represent a unique contribution to the previous literature on moderators of the association between BI and adolescent anxiety. Results of the present study enhance our understanding regarding how biology and the early environment interact to predict one of the most prevalent types of anxiety disorders among adolescents. Altering parent behaviors among at-risk dyads by teaching parents to provide sensitive, responsive care, may be particularly important in the prevention of anxiety disorders among children who show BI consistently over time (Bernard et al., 2012; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2012).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01MH07454 and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R37HD17899 awarded to Nathan A. Fox.

References

- Aiken LS, West GM. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publishing; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth M, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: psychological study of the Strange Situation. Lawrence Erlbaum; Oxford, England: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Sutton D, Fox NA, Marvin RS. Stability and change of attachment at 14, 24, and 58 months of age: Behavior, representation, and life events. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:381–388. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, Lewis Morrarty E, Lindhiem O, Carlson E. Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Development. 2012;83:623–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M. Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1230–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011. doi:10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis; London, England: 1969. Attachment and Loss, Vol. I. Attachment. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss, Vol. II. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Anisworth. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:759–775. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759. [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu LE, Kerns KA. Parent-child attachment and internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence: A review of empirical findings and future directions. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:177–203. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990344. doi:10.1017/S0954579409990344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KB, Marshall PJ, Rubin KH, Fox NA. Infant attachment and temperament as predictors of subsequent externalizing problems and cardiac physiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:819–831. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00167. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA. The relations among infant temperament, security of attachment, and behavioral inhibition at twenty-four months. Child Development. 1992;63:1456–1472. doi:10.2307/1131568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EA, Sroufe L. Contribution of attachment theory to developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 1: Theory and methods. John Wiley & Sons; Oxford, England: 1995. pp. 581–617. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Elder GH, Bem DJ. Moving away from the world: Life-course patterns of shy children. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:824–831. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.24.6.824. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:228–283. doi:10.2307/1166148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Berlin LJ. The insecure/ambivalent pattern of attachment: Theory and research. Child Development. 1994;65:971–981. doi:10.2307/1131298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan K, Pine D, Pérez-Edgar K, Henderson H, Diaz Y, Fox N. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Thomas SR, O'Brien KA, Huggins SL, Dougherty LR, Ellison K, Rubin KH. The turtle project: A multi-component intervention to help inhibited preschoolers come out of their shells.. Poster presented at the meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy (ABCT); National Harbor, MD.. Nov, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, Blackford J. Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: A meta-analytic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:1066–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonnesi C, Draijer EM, Jan JM, Stams G, Van der Bruggen CO, Bögels SM, Noom MJ. The relation between insecure attachment and child anxiety: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:630–645. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581623. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.581623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Closson LM, Arbeau KA. Gender differences in the behavioral associates of loneliness and social dissatisfaction in kindergarten. Journal Of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:988–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01804.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Angold A. Epidemiology. In: March JS, editor. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and Development of Psychiatric Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. Archives Of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Thomas SA, Goodman KL, Kundey SMA. Principles underlying the use of multiple informants’ reports. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:123–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185617. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Almas AN, Fox NA. Temperament and the environment in the etiology of childhood anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:497–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02228.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:729–746. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000363. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doey L, Coplan RJ, Kingsbury M. Bashful boys and coy girls: A review of gender differences in childhood shyness. Sex Roles. 2013;70 doi:10.1007/s11199-013-0317-9. [Google Scholar]

- Esbjørn BH, Bender PK, Reinholdt-Dunne ML, Munck LA, Ollendick TH. The development of anxiety disorders: Considering the contributions of attachment and emotion regulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2012;15:129–143. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0105-4. doi:10.1007/s10567-011-0105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Klein MH, Slattery MJ, Goldsmith HH, Kalin NH. Early risk factors and development pathways to chronic high inhibition and social anxiety disorder in adolescence. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:40–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.07010051. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.07010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Lapsley A, Roisman GI. The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children s externalizing behavior: A meta-analytic study. Child Development. 2010;81:435–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox N, Henderson H, Marshall P, Nichols K, Ghera M. Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Reviews of Psychology. 2005;56:235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox N, Henderson H, Rubin K, Calkins S, Schmidt L. Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001;72:1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson WA. Three multivariate models: factor analysis, latent structure analysis and latent profile analysis. Psychometrika. 1959;24:229–252. doi: 10.1007/BF02289845. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH. Studying temperament via construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Development. 1996;67:218–235. doi: 10.2307/1131697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh AM, Roisman GI, van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans Kranenburg MJ, Fearon R. The significance of insecure and disorganized attachment for children's internalizing symptoms: A meta analytic study. Child Development. 2012;83:591–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01711.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen NL, Jacobvitz D, Higgins KN, Allen S, Jin M. Pathways from disorganized attachment to later social-emotional problems; The role of gender and parent child interaction patterns. In: Solomon J, George C, editors. Disorganized attachment and caregiving. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 167–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J. Temperament and the reactions to the unfamiliarity. Child Development. 1997;68:139–143. doi: 10.2307/1131931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick J, Snidman N. Temperamental influences on reactions to unfamiliarity and challenge. In: Chrousos GP, Loriaux D, Gold PW, editors. Mechanisms of physical and emotional stress. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1988. pp. 319–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SJ, Rapee RM, Edwards SL. A selective intervention program for inhibited preschool-aged children of parents with an anxiety disorder: Effects on current anxiety disorders and temperament. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:602–609. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819f6fa9. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819f6fa9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Waldman ID, Loft JD, Hankin BL, Rick J. The Structure of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology: Generating New Hypotheses. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:358–385. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.358. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Morrarty E, Degnan KA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Rubin KH, Cheah CL, Pine DS, Fox NA. Maternal over-control moderates the association between early childhood behavioral inhibition and adolescent social anxiety symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1363–1373. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9663-2. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9663-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. J. Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. doi: 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Atkinson L, Laurin K, Benoit D. Attachment and internalizing behavior in early childhood: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:672–689. doi: 10.1037/a0028793. doi:10.1037/a0028793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Solomon J. Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In: Brazelton T, Yogman MW, editors. Affective development in infancy. Ablex Publishing; Westport, CT: 1986. pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Manassis K, Bradley SJ. The development of childhood anxiety disorders: Toward an integrated model. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1994;15:345–366. doi:10.1016/0193-3973(94)90037-X. [Google Scholar]

- Manassis K, Bradley S, Goldberg S, Hood J. Behavioural inhibition, attachment and anxiety in children of mothers with anxiety disorders. The Canadian Journal Of Psychiatry. 1995;40:87–92. doi: 10.1177/070674379504000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf SC, Frosch CA. Temperament and attachment: One construct or two? In: Reese HW, editor. Advances in child development and behavior. Vol. 27. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 181–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall PJ, Fox NA. Relations between behavioral reactivity at 4 months and attachment classification at 14 months in a selected sample. Infant Behavior & Development. 2005;28:492–502. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.06.002. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Sixth Edition. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Infant-mother attachment classification: Risk and protection in relation to changing maternal caregiving quality. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:38–58. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.38. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JNM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion. 2010;10:349–357. doi: 10.1037/a0018486. doi: 10.1037/a0018486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, Plomin R. Temperament in early childhood. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1977;41:150–156. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4102_5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4102_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH. The Play Observation Scale (POS) University of Maryland; 2001. Unpublished instrument Available from author. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of The American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1008–1015. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017. doi:10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir-Essakow G, Ungerer JA, Rapee RM. Attachment, Behavioral Inhibition, and Anxiety in Preschool Children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:131–143. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-1822-2. doi:10.1007/s10802-005-1822-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children for DSM-IV, Child and Parent Versions. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Spangler T, Gazelle H. Anxious solitude, unsociability, and peer exclusion in middle childhood: A multitrait—multimethod matrix. Social Development. 2009;18:833–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00517.x. doi:10.1111/sode.2009.18.issue-410.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler GG, Grossmann KE. Biobehavioral organization in securely and insecurely attached infants. Child Development. 1993;64:1439–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02962.x. doi:10.2307/1131544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe L. Emotional development: The organization of emotional life in the early years. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1996. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511527661. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe L, Egeland B, Carlson EA, Collins W. The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. Guilford Publications; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe L, Waters E. Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Development. 1977;48:1184–1199. doi:10.2307/1128475. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson-Hinde J, Shouldice A, Chicot R. Maternal anxiety, behavioral inhibition, and attachment. Attachment & Human Development. 2011;13:199–215. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2011.562409. doi:10.1080/14616734.2011.562409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner PJ. Relations between attachment, gender, and behavior with peers in preschool. Child Development. 1991;62:1475–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01619.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Brakel AL, Muris P, Bögels SM, Thomassen C. A Multifactorial Model for the Etiology of Anxiety in Non-Clinical Adolescents: Main and Interactive Effects of Behavioral Inhibition, Attachment and Parental Rearing. Journal Of Child And Family Studies. 2006;15:569–579. doi:10.1007/s10826-006-9061-x. [Google Scholar]

- van der Bruggen CO, Stams GM, Bögels SM. Research review: The relation between child and parent anxiety and parental control: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:1257–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01898.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH. Adult attachment representations, parental responsiveness, and infant attachment: A meta-analyses on the predictive validity of the Adult Attachment Interview. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:387–403. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.387. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Kroonenberg PM. Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: A meta-analysis of the Strange Situation. Child Development. 1988;59:147–156. doi: 10.2307/1130396. [Google Scholar]

- Vertue FM. From adaptive emotion to dysfunction: An attachment perspective on social anxiety disorder. Personality And Social Psychology Review. 2003;7:170–191. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0702_170-191. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0702_170-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SL, Huston L, Egeland B, Sroufe L. Child and adolescent anxiety disorders and early attachment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:637–644. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00014. doi:10.1097/00004583-199705000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]