Abstract

MSCs encounter extended hypoxia in the wound microenvironment yet little is known about their adaptability to this prolonged hypoxic milieu. In this study, we evaluated the cellular and molecular response of MSCs in extended hypoxia (1% O2) vs. normoxia (20% O2) culture. Prolonged hypoxia induced a switch towards anaerobic glycolysis transcriptome and a dramatic increase in the transcript and protein levels of monocarboxylate transporter-4 (MCT4) in MSCs. To clarify the impact of MCT4 upregulation on MSC biology, we generated MSCs which stably overexpressed MCT4 (MCT4-MSCs) at levels similar to wildtype (WT) MSCs following prolonged hypoxic culture. Consistent with its role to efflux lactate to maintain intracellular pH, MCT4-MSCs demonstrated reduced intracellular lactate. To explore the in vivo significance of MCT4 upregulation in MSC therapy, mice were injected intramuscularly following MI with control (GFP)-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs or MSCs in which MCT4 expression was stably silenced (KDMCT4-MSCs). Overexpression of MCT4 worsened cardiac remodeling and cardiac function whereas silencing of MCT4 significantly improved cardiac function. MCT4-overexpressing MSC secretome induced reactive oxygen species-mediated cardiomyocyte but not fibroblast apoptosis in vitro and in vivo; lactate alone recapitulated the effects of the MCT4-MSC secretome. Our findings suggest that lactate extruded by MCT4-overexpressing MSCs preferentially induced cell death in cardiomyocytes but not in fibroblasts, leading ultimately to a decline in cardiac function and increased scar size. A better understanding of stem cells response to prolonged hypoxic stress and the resultant stem cell-myocyte/fibroblast cross-talk is necessary to optimize MSC-based therapy for cardiac regeneration.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cells, hypoxia, monocarboxylate transporter 4, secretome, lactate

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been used as therapeutics to repair injured heart, soft tissue, and bone [1, 2]. Presently there are more than 100 clinical trials that use exogenous bone-marrow derived human MSCs (clinicaltrial.gov) targeting cardiovascular diseases [3, 4]. The outcomes of clinical trials for myocardial infarction (MI) have shown modest improvement in the left ventricle ejection fraction [5–7]. Despite the modest clinical benefits, the outstanding safety profile and clinical scalability of MSCs continue to make them a highly desirable candidate for regenerative cell therapy [8]. Thus, there is a strong interest to identify potential molecular and cellular factors that limit the therapeutic potency of current MSC-based therapies.

Prior to transplantation, MSCs are typically cultured in ambient, 20% oxygen conditions. When injected into injured tissue, MSCs face oxygen concentration that can range from 0.4% to 2.3% O2 referred as hypoxia [9]. Much of the published work studying the effects of hypoxia on MSCs has evaluated the impact of short bursts of hypoxic exposure [10–12]. Overall, these studies indicate that short-term hypoxic preconditioning induced a pro-survival and pro-angiogenic MSC secretome and also increased MSC survival in vitro [10, 11]. In fact, short bursts of “ischemic preconditioning” of MSCs prior to administration have resulted in faster recovery of mice from vascular injury in a hind limb ischemia model [12] and improved heart function through increased angiogenesis and enhanced MSC survival [10]. A few studies have examined prolonged hypoxia. Although MSCs maintain their proliferative and multipotent capacity after prolonged hypoxia [13, 14], the metabolic changes (and their impact on the host) after extended hypoxia are poorly understood [15].

Following administration into the injured tissue, a large number of MSCs die immediately but some portion survive beyond 3 days and are evident through 14 days after administration [16, 17]. We postulate that cells that survive beyond 72 hours arguably have greater impact on host repair and sought to better understand the impact of the prolonged hypoxic environment on their function.

In the present study, we showed that prolonged exposure to hypoxia leads to considerable upregulation of transcript and protein levels of proton-linked monocarboxylate transporter 4 (MCT4) in bone-marrow-derived mouse MSCs. MCT4 belongs to a family of proton-linked MCTs that facilitate the transport of monocarboxylates (such as pyruvate and lactate) across the plasma membrane [18]. In the event of intracellular lactate accumulation, resulting from high glycolytic flux, MCT4 maintains cellular pH by effluxing monocarboxylates across the plasma membrane [19]. Our data suggest that hypoxia-induced overexpression of MCT4 in MSCs generates increased lactate within the wound bed, leading to cardiomyocyte apoptosis and adverse effects on cardiac repair after acute MI.

Material and methods

Animals

Wild-type C57Bl/6 (WT) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and are maintained by PPY. All surgeries were carried out in accordance with Vanderbilt Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The protocol was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol Number: M/07/236). All experiments were performed using appropriate analgesics and anesthetics, and every effort was made to minimize pain/distress.

Myocardial Infarctions (MI)

For MI model, anesthetized mice were intubated. Ligation of the left anterior descending artery was performed by placing a 7–0 silk suture through the myocardium into anterolateral LV wall. One time injection of PBS (n=6), 2.5 × 105 GFP (n=5), MCT4 (n=5) and KDMCT4 (n=6) -MSCs in 20 µL of PBS was administered around the infarct area. Following MI, echocardiograms were performed at day 7 and day 30 and were blindly read using short axis and a parasternal long-axis views with the leading edge method. At day 30 mouse hearts were excised and were immersion-fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours and transferred to 70% ethanol. Each paraffin-fixed heart was sliced in 6 µm cross sections at four levels spanning from the apex to the base and prepared for routine histology. These sections were stained with H & E and Masson trichrome and analyzed by light microscopy. Measurements of the length of the entire endocardial circumference and that segment of the endocardial circumference made up by the infarcted portion from each of the four slices of the left ventricle were determined. The infarct size, expressed as a percentage of the left ventricle, was calculated by dividing the circumference of the infarct by the total circumference of the left ventricle including the septum by our co-investigator, Dr. Atkinson [20]. A different cohort of mice received 2.5 × 105 GFP (n=3), MCT4 (n=3) and KDMCT4 (n=4) -MSCs following MI. These mice were sacrificed on day 3 for caspase-3 immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Additional Methods

Methods for cell culture, hypoxia conditions, conditioned media generation, transduction, membrane fractionation, immunoblotting, RNA isolation, complementary DNA synthesis, and semi-quantitative real time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), immunofluorescence (IF) and immunohistochemistry, BrdU cell proliferation, cell viability, and Live/Dead assay, intracellular measurements of reactive oxygen species, lactate, and pyruvate, and statistical analyses are provided in supplementary materials and methods.

Results

The transcriptome of MSCs switched towards anaerobic glycolysis following extended hypoxia

Hypoxia-induced molecular signature of bone-marrow-derived WT mouse MSCs was determined by culturing them in normoxia (20% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2) and total RNA submitted for microarray analysis to identify gene expression changes following prolonged hypoxia (48 hours). Gene expression analysis identified the upregulation of several metabolic regulators including an array of enzymes that regulate (a) the rate of glycolysis [hexokinase 2 (HK2), triose phosphate isomerase 1 (Tpi1), phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (Pgk1), phosphoglycerate mutase 1 (Pgam1), phosphofructokinase (Pfk), glucose phospho isomerase (Gpi1), enolase 1 (Eno1), and aldolase a and c (Aldoa and Aldoc)], (b) switch from aerobic towards anaerobic respiration [pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (Pdk1), and lactate dehydrogenase A and D (Ldha and Ldhd)], (c) energy homeostasis [phosphoglucomutase 2 (Pgm2), adenylate kinase 4 (Ak4), and sodium glucose co-transporter (Slc2a3), carbonic anhydrase 12 (Car12)], and (d) the transport of monocarboxylates across plasma membrane [(monocarboxylate transporter 2 (MCT2, Slc16a2), and 4 (MCT4, Slc16a3)] in MSCs exposed to extended hypoxia (Fig. 1A, left panel). The glycolytic pathway showing the measured key metabolic genes highlighted in blue (Fig. 1A, right panel). The transcript levels of key metabolic enzymes were further validated by RT-PCR analysis in WT-MSCs cultured in normoxia and hypoxia for 48 and 72 hours (only data from 72 hours shown since no difference in transcript levels was identified between 48 and 72 hours). Increased expression of HK1 (2.04 ± 0.86 fold) and 2 (4.73 ± 1.21 fold; p<0.01), and enolase (3.96 ± 1.59 fold; p<0.001) confirmed the activation of glycolytic pathway enzymes (Fig. 1B), and increased transcript levels of LDHA (2.96 ± 0.54 fold; p<0.01), carbonic anhydrase (CarAnh, 3.92 ± 1.99 fold; p<0.01), and PDK1 (11.03 ± 1.63 fold; p<0.001) and 3 (5.89 ± 1.24 fold; p<0.001) (Fig. 1C) signified anaerobic glycolysis as an adaptation of MSCs to hypoxia.

Figure 1.

Prolonged hypoxia drives the transcription of key metabolic genes in MSCs. (A): Heat map of the panel of glycolytic genes (HK2, Tpi1, Pgk1, Pgam1, Pfk, Gpi1, Eno, and Aldo), genes involved in the switch from aerobic to anaerobic respiration (Ldha, Ldhd, pdk1), cellular homeostasis (Ak4, Pgm2, Car12, Slc2a3), and efflux of monocarboxylates [Slc16a2 (MCT2) and Slc16a3 (MCT4)] in MSCs subjected to normoxia (20% O2; green) vs. hypoxia (1% O2; red) for 48 hours. The color scale depicts green to red values on a scale of 0–3 (B): RT-PCR of glycolytic genes (HK1, HK2, and enolase), (C): genes regulating the switch from aerobic to anaerobic respiration (LDH-A, PDK-1, PDK-3, and CarAnh), (D, top panel): MCT4 and (E): MCT1 in MSCs, HUVECs, and NIH3T3 cells cultured in normoxia and hypoxia for 72 hours. (D, bottom panel): Immunoblot analysis of MCT4 in the membrane fraction of MSCs cultured in normoxia and hypoxia. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 were calculated by two way ANOVA using Bonferroni post-test, n=3 experiments were performed; bar represent mean ±SD.

MSCs subjected to prolonged hypoxia show dramatic upregulation of monocarboxylate transporter 4 (MCT4) transcripts and protein

Interestingly, prolonged hypoxia for 48 or 72 hours induced a significant upregulation of MCT4 transcripts (303 ± 71.97 fold; p<0.001) and cell surface protein expression levels measured by real time RT-PCR (Fig. 1D, upper panel; only data from 72 hours shown) and immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1D, lower panel), respectively. Whereas in normoxic MSCs, MCT4 expression was low to undetectable. Prolonged exposure (>48 hours) to hypoxia was required for elevated MCT4 transcripts as MSCs exposed to hypoxia for 6, 16 or 24 hours exhibited undetectable MCT4 levels (Supporting information, Fig. S1). Moreover, cell surface MCT4 protein expression levels remained constantly upregulated for upto 5 days of extended hypoxia exposure (Supporting information, Fig. S2). Increased MCT4 protein expression was also detected in human MSCs with prolonged hypoxia exposure (data not shown). The dramatic upregulation of MCT4 was unique to MSCs as HUVECs and a mouse fibroblast cell line, NIH3T3, showed significantly low or unchanged transcript levels, respectively, following 72 hours of culture in hypoxia (Fig. 1D, upper panel). To determine if changes were observed in other moncarboxylate transporters, we evaluated the transcript level of monocarboxylate transporter 1 and 2 (MCT1 and MCT2). MCT1 was slightly induced (4.27 ± 1.33 fold; p<0.001) in MSCs (Fig. 1E), but not in HUVECs or NIH3T3s in response to hypoxia. MCT2 transcript levels were very low in both hypoxic and normoxic MSCs. HUVEC and NIH3T3 cell responsiveness to hypoxia was determined by the significant upregulation of key metabolic enzymes (LDH-A and HK1) in hypoxic culture (Supporting information, Fig. S3). In summary, while adaptation of MSCs to anaerobic respiration in hypoxia has previously been shown [21], a dramatic upregulation of MCT expression following prolonged hypoxia has not been reported. The increased expression of MCT4 in MSCs suggested that lactic acid efflux is a unique adaptation to hypoxia by MSCs, and not present in other differentiated cells of mesenchymal origin (such as HUVECs or fibroblasts).

MCT4-overexpressing MSCs (MCT4-MSCs) maintained low intracellular lactate, whereas MCT4 knockdown MSCs (KDMCT4-MSCs) accumulated intracellular lactate in hypoxia

To investigate the contribution of hypoxia-induced upregulation of MCT4 on MSC homeostasis, we generated retrovirus-mediated stably transduced MSC lines overexpressing MCT4. Fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS) enrichment using GFP co-expression yielded >95% pure population of MCT4-MSCs (Supporting information, Fig. S4). MSCs expressing GFP alone (GFP-MSCs) were generated as empty vector control. Importantly, the fold increase of transcript and MCT4 protein levels in MCT4-MSCs was comparable to that in WT-MSCs subjected to 72 hours of hypoxia (Fig. 2A)

Figure 2.

Altering MCT4 expression in MSCs resulted in changes in intracellular lactate to pyruvate ratio. (A): WT-MSCs transduced with retroviral particles containing MCT4 together with GFP (MCT4-MSCs) were sorted for GFP expression. WT-MSCs transduced with retroviral particles containing GFP alone (GFP-MSC) were also sorted for control. RT-PCR (top panel) and immunoblot (bottom panel) analysis of the membrane fraction of MCT4-MSCs and GFP-MSCs cultured in normoxia and hypoxia for 72 hours for MCT4 expression. (B): WT-MSCs, WT-MSCs transduced with shRNA knockdown of MCT4 (KDMCT4-MSCs) and control shRNA (Csh-MSCs) were selected for puromycin resistance and analyzed by RT-PCR (top panel) and immunoblot of the membrane fractions (bottom panel) for MCT4 expression. β-actin was used as loading control. (C): Intracellular lactate to pyruvate ratio in GFP-MSCs vs. MCT4-MSCs and (D): Csh-MSCs vs. KDMCT4-MSCs cultured for 24 hours in normoxia and hypoxia. Statistical significance, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 were calculated by paired t-test or two way ANOVA using Bonferroni post-test, n=3 experiments were performed; bar represent mean ±SD.

In parallel, we also knocked down MCT4 transcripts in MSCs with 4 independent shRNAs and assessed MCT4 expression by immunoblot (Supporting information, Fig. S5). KDMCT4-MSCs, derived using shRNA clones 1, 2, 4, and 5, showed a 78%–95% reduction in MCT4 transcript levels (Fig. 2B, top panel and data not shown) and a 99% reduction in protein levels (Fig. 2B, bottom panel and supporting information, Fig. S5) when compared to WT-MSCs stably transduced with control shRNA (Csh-MSCs) and subjected to hypoxia. KDMCT4-MSCs derived using shRNA clone 4 were expanded for further experiments.

MCT4-MSCs maintained low lactate-to-pyruvate ratios as compared to GFP-MSCs in both normoxia (6.355 ± 0.204 vs. 13.2 ± 1.545; p<0.001) and hypoxia (8.368 ± 0.278 vs. 15.536 ± 1.110; p<0.001), indicating that the overexpressed protein was functional in extruding lactate. (Fig. 2C). KDMCT4-MSCs had higher intracellular lactate-to-pyruvate ratios in hypoxia than Csh-MSCs (1.755 ± 0.122 vs. 1.096 ± 0.086; p<0.01), indicating a decline in the cell’s ability to extrude lactate (Fig. 2D). In addition, real time RT-PCR analysis of hypoxic KDMCT4-MSCs identified no change in the transcript levels of glycolytic enzymes (HK1, HK2, and enolase) or enzymes involved in anaerobic respiration (LDH-A and PDK1 and PDK3) (Supporting information, Fig. S6), ruling out compensation for MCT4 with other enzymes or transporters following MCT4 knockdown.

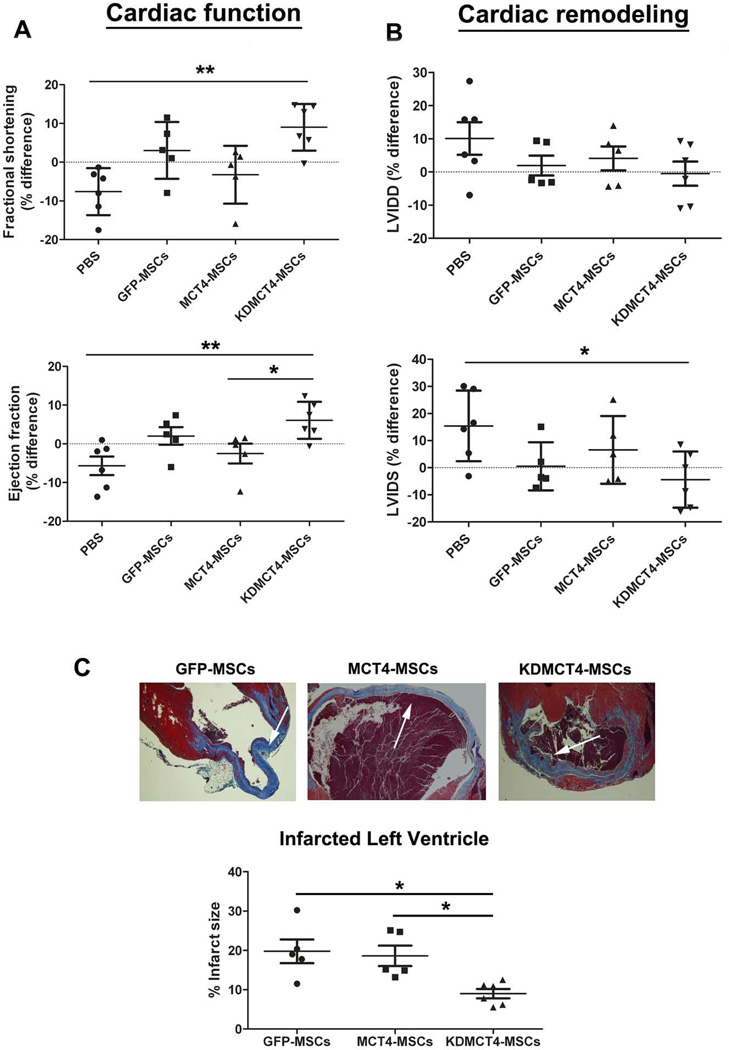

MCT4 overexpression adversely affected MSC-mediated cardiac repair, whereas MCT4 knockdown enhanced MSC-mediated cardiac repair

To evaluate if MCT4 could modulate MSC-mediated cardiac repair, a single injection of PBS, GFP-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs, and KDMCT4-MSCs was administered into the peri-infarct region of left ventricle following MI induced by coronary artery ligation. Left ventricular function and remodeling were evaluated by echocardiography at day 7 and day 30 post-MI and the percentage differences (Δ) was determined using the formula, % differences (Δ) =100*(d30-d7)/d7. The percentage differences in fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF) represented change in cardiac function. Consistent with earlier studies, mice injected with all MSCs showed an improvement in ΔEF (2.02 ± 5.11 for GFP- MSCs, −2.51 ± 5.71 for MCT4-MSCs, and 6.06 ± 4.79 for KDMCT4-MSCs [p<0.01] vs. −5.67 ± 5.89 for PBS) and ΔFS (3.02 ± 7.33 for GFP-MSCs, −3.26 ± 7.47 for MCT4-MSCs, and 9.00 ± 6.02 for KDMCT4-MSCs [p<0.01] vs. −7.62 ± 6.06 for PBS) in comparison to PBS injected controls (Fig. 3A). Surprisingly, MCT4-MSC recipient showed a decline in both ΔEF (−2.51 ± 5.71 vs. 2.02 ± 5.11) and ΔFS (−3.26 ± 7.47 vs. 3.02 ± 7.33) compared with GFP-MSC injected controls. In contrast, KDMCT4-MSC recipient mice exhibited significant improvement in functional parameters 30 days post-infarct when compared with MCT4-MSC recipient mice [ΔEF (6.06 ± 4.79 vs. −2.51 ± 5.71; p<0.05) and ΔFS (9.00 ± 6.02 vs. −3.26 ± 7.47]. Although not statistically significant, KDMCT4-MSC recipient mice also showed a trend towards improvement in cardiac function in comparison to GFP-MSC recipient mice [ΔEF (6.06 ± 4.79 vs. 2.02 ± 5.11) and ΔFS (9.00 ± 6.02 vs. 3.02 ± 7.33)] (Fig. 3A). Adverse ventricular remodeling was measured by left ventricle internal dimension at diastole and systole (LVIDD and LVIDS). In comparison to PBS injected mice, all MSCs showed a decline in ΔLVIDD (1.94 ± 6.68 for GFP-MSCs, 4.09 ± 8.07 for MCT4-MSCs, and −0.481 ± 8.93 for KDMCT4-MSCs vs. 10.1 ± 12.0 for PBS) and ΔLVIDS (0.504 ± 8.86 for GFP-MSCs, 6.58 ± 12.5 for MCT4-MSCs, and −4.40 ± 10.4 for KDMCT4-MSCs [p<0.05] vs. 15.4 ± 13.0 for PBS) (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, there was no significant improvement with an inclination towards increase in the ΔLVIDD (4.09 ± 8.07 vs. 1.94 ± 6.68) and ΔLVIDS (6.58 ± 12.5 vs. 0.504 ± 8.86) parameters in mice receiving MCT4-MSCs compared to GFP-MSCs receiving mice. Conversely, KDMCT4-MSC receiving mice showed a trend towards reduction in adverse cardiac remodeling when compared to MCT4-MSC receiving mice [ΔLVIDD (−0.481 ± 8.93 vs. 4.09 ± 8.07) and ΔLVIDS (−4.40 ± 10.4 vs. 6.58 ± 12.5)] and GFP-MSC receiving mice [LVIDD (−0.481 ± 8.93 vs. 1.94 ± 6.68) and LVIDS (−4.40 ± 10.4 vs. 0.504 ± 8.86)] (Fig. 3B). Moreover, KDMCT4-MSCs showed a significant reduction in infarct size compared to GFP-MSCs (9.00 ± 2.89 vs. 19.8 ± 6.75; p<0.05) and MCT4-MSCs (9.00 ± 2.89 vs. 18.6 ± 5.79; p<0.05) (Fig. 3C), as determined by histomorphometry. These results indicated that knocking down MCT4 significantly improved the reparative effects of MSCs signified by improvement in cardiac function and decline in the infarct size.

Figure 3.

MCT4 overexpression adversely affected MSC-mediated cardiac repair whereas knocking down MCT4 in MSCs improved cardiac remodeling and function. PBS, GFP-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs, and KDMCT4-MSCs were injected peri-infarct immediately following the infarction. (A): Cardiac function represented by fractional shortening and ejection fraction and (B): cardiac remodeling represented by LVIDD and LVIDS were plotted as percentage difference (Δ%) values (mean ± SD) between day 7 and 30 after myocardial infarct to show therapy-mediated impact on cardiac remodeling and function. (C, top panel): Representative Masson’s trichrome-stained sections (blue-staining representing collagen deposition) of heart from mice 30 day after receiving GFP-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs, and KDMCT4-MSCs following MI. White arrows point towards the infarcted ventricle. (C, bottom panel): % infarct size of mice hearts injected with designated MSCs. **p<0.01 and *p<0.05 were calculated using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test (n=5 for GFP-MSCs and MCT4-MSCs and n=6 for PBS and KDMCT4-MSCs).

Changes in MCT4 expression did not alter MSC proliferation or survival in hypoxia

To determine whether the effect of altered MCT4 expression on cardiac repair by MSCs was due to their ability to proliferate and/or survive in hypoxia, MSCs with both increased or decreased MCT4 expression were cultured in 1% O2 or 20% O2 at 37 °C and their proliferation and survival was measured by BrdU and MTT assay, respectively. The BrdU assay identifies actively proliferating cells by getting incorporated into newly synthesized DNA. The MTT assay is a surrogate measure of survival by measuring the metabolic activity of the cell. MSCs proliferated better in hypoxia in comparison to normoxia, consistent with prior reports [22, 23]; proliferation was not affected by MCT4 expression levels (Fig. 4A and B). Similarly, survival of MCT4-MSCs and KDMCT4-MSCs did not change significantly compared to their respective controls, GFP-MSCs and Csh-MSCs, in normoxic or hypoxic culture (Fig. 4C and D). These results indicated that the effect of altered MCT4 expression in MSCs on influencing post-MI LV function and infarct size was not due to MCT4-regulated changes on MSC proliferation or survival.

Figure 4.

Altering MCT4 expression did not change their ability to proliferate or survive in hypoxia. MCT4-MSCs and KDMCT4-MSCs together with their respective controls (GFP-MSCs and Csh-MSCs) were subjected to normoxia or hypoxia for 48 hours. (A and B): Proliferation was assessed by BrdU ELISA and (C and D): cell survival was measured by MTT assay; nsp>0.05 was calculated using two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-test, n=3 experiments were performed in triplicate; bar represent mean ±SD.

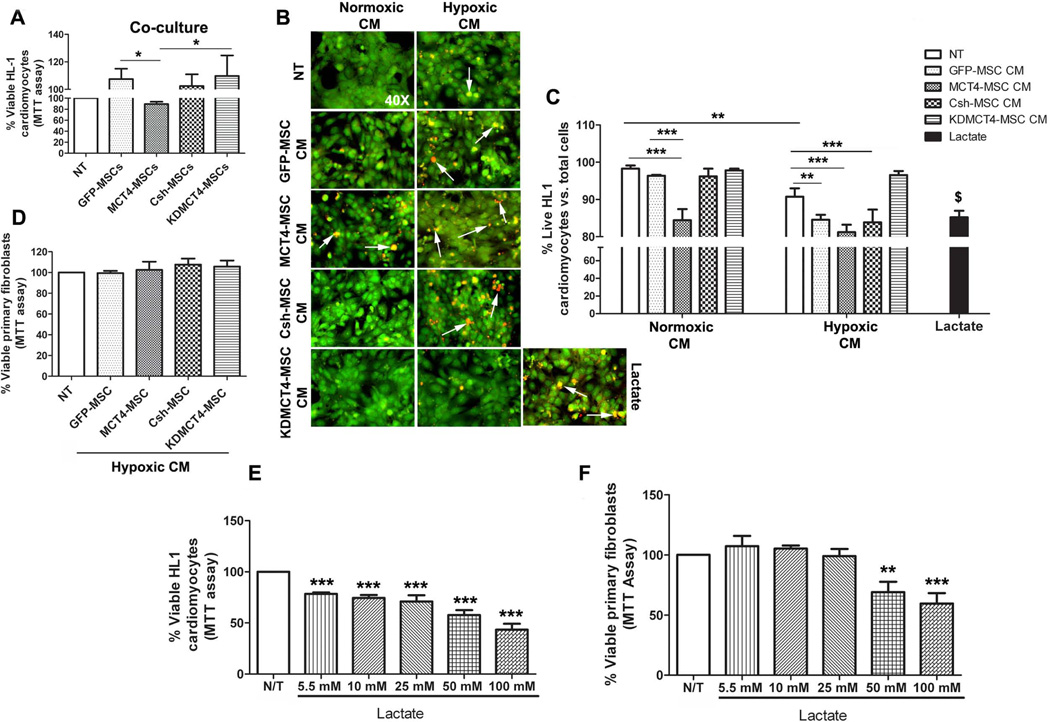

MCT4 overexpression generated an MSC secretome which adversely affected cardiomyocyte survival

Since MCT4 expression did not affect proliferation or survival of MSCs, we evaluated its effect on the MSC secretome and cells residing in the infarcted milieu of the heart. First we used co-culture of MSCs overexpressing or with knockdown of MCT4 with HL1 cardiomyocytes. The HL1 cell line is a well characterized cardiomyocyte cell line which retains the characteristics of adult cardiomyocytes and possesses the ability to beat in confluent cultures [24]. After culture in normoxia for 72 hours, only MCT4-MSCs significantly inhibited HL1 survival (89.2 ± 4.28% vs. 107 ± 7.6% with GFP-MSCs; p<0.05 Fig. 5A) measured by MTT assay. To determine if reduced HL-1 survival resulting from co-culture with MCT4-MSCs was due to an altered secretome, we tested the conditioned media (CM) generated from the various MSC transducts. We collected CM after 5 days of normoxic or hypoxic culture to allow sufficient time for accumulation and enrichment of resulting secretome, which were subsequently added to HL1 cultures to evaluate effects on their survival by the Live/Dead assay. Analysis of CM derived from MSCs cultured in normoxia demonstrated that only CM from MCT4-MSC inhibited HL1 cell survival (84.42 ± 2.98%; p<0.001) compared to no treatment (NT; 98.26 ± 0.87%) (Fig. 5B and 5C). However, CM derived from prolonged hypoxic culture of both the control MSCs (GFP-MSCs: 84.54 ± 1.35%; p<0.01; and Csh-MSCs: 83.85 ± 3.43%; p<0.001) and MCT4-MSCs (81.21 ± 1.99%; p<0.001) reduced HL1 cell survival. Particularly, control MSCs upregulate cell surface MCT4 expression to levels comparable to MCT4-MSCs after prolonged hypoxia. However, CM derived from KDMCT4-MSCs did not inhibit HL1 cell survival (97.83 ± 0.43%, normoxia derived or 96.56 ± 1.08%, hypoxia derived) (Fig. 5B and 5C). Lactate, used as a positive control, also significantly reduced HL1 cell survival (85.2 ± 1.74%; p<0.01) vs. HL1 cells cultured in normoxia (98.26 ± 0.87%). Notably, hypoxia treatment alone also caused a reduction in HL1 cell survival (90.8 ± 2.24%; p<0.01) compared to cells cultured in normoxia (98.26 ± 0.87%) but not at the level as induced by hypoxic MSC CM. These results were confirmed with MTT assay which demonstrated a significant decline in the percent of live HL1 cells in the presence of hypoxic GFP-MSC CM (75.9 ± 4.12%; p<0.001), Csh-MSC CM (76.1 ± 4.15%; p<0.001), and MCT4-MSC CM (73.5 ± 3.47%; p<0.001) whereas KDMCT4-MSC CM (93.2 ± 8.99%) had no effect on HL1 survival (Supporting information, Fig. S7). Overall, these results indicated that MCT4 expression in MSCs resulted in a secretome that reduced myocyte survival. Moreover, the effects of MCT4 on the MSC secretome could be recapitulated by culturing WT-MSCs in hypoxia.

Figure 5.

MCT4-MSC secretome and lactate induced cell death in cardiomyocytes but not in primary fibroblasts. (A): HL1 cardiomyocytes were co-cultured with GFP-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs, Csh-MSCs, and KDMCT4-MSCs in normoxia for 72 hours. Cell survival was measured by MTT assay and plotted as % viable HL1 cardiomyocytes. The data was normalized to HL1 cells cultured in the Claycomb media in normoxia. (B and C): HL1 cardiomyocytes were treated with normoxic or hypoxic conditioned media (CM) obtained from 5-day culture of GFP-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs, Csh-MSCs, and KDMCT4-MSCs. Treatment was performed for 24 hours in hypoxia. Cell survival was measured by Live/Dead assay and plotted as % live HL1 cardiomyocytes vs. total cells. HL1 cells cultured in normoxia in the absence or presence of 25 mM D-lactate were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Green staining represents live cells whereas red staining represents dead cells. White arrows point towards the red stained dead cells. (D): Mouse primary fibroblasts were treated for 24 hours in normoxia with hypoxic CM obtained from 5-day culture of GFP-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs, Csh-MSCs, and KDMCT4-MSCs. Cell survival was measured by MTT assay and plotted as % viable HL1 cardiomyocytes. The data was normalized to primary fibroblasts cultured in normoxia. (E and F): HL1 cardiomyocytes and mouse primary fibroblasts were treated with increasing concentrations (5.5–100 mM) of lactate in normoxia. Cell survival was measured by MTT assay and plotted as % viable (E) HL1 cardiomyocytes and (F): primary fibroblasts. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 were calculated using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test or two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-test. $p<0.001 was calculated using unpaired t-test. n=3 independent experiments were performed in triplicate; bar represent mean ±SD

To determine whether the cell death response induced by MCT4’s effect on the MSC secretome was preferential to cardiomyocytes or a general phenomenon, mouse primary fibroblasts were treated with CM obtained from GFP-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs, Csh-MSCs, and KDMCT4-MSCs following 5 day hypoxic culture. Interestingly, no significant influence on fibroblast survival was identified (Fig. 5D). These data indicated that MCT4 induced a MSC secretome that exhibited a deleterious effect on cardiomyoctyes (i.e. HL1 cells) but not on fibroblast cells. The adverse effect of MCT4-induced MSC secretome on cardiomyocyte survival was avoided when MCT4 expression was specifically knocked down in MSCs.

Lactate reduced cell survival in cardiomyocyte but not in primary fibroblasts

MCT4 is primarily responsible for extrusion of lactate from cells [25]. Thus MCT4 overexpressing secretome would be expected to contain higher levels of lactate. To identify if lactate alone can mimic the effect of MCT4 on MSC CM, we assessed HL1 and fibroblast survival following culture in increasing concentrations of lactate. Decreased cardiomyocyte survival was evident (78.4 ± 1.4% to 43.5 ± 5.74%; p<0.001) with increasing amount of lactate (5.5 mM to 100 mM) in normoxia (Fig. 5E) and hypoxia (82.7 ± 10.4% to 58.2 ± 0.20%; p<0.05 to p<0.001); Supporting information, Fig. S8A). By contrast, supra-physiological levels (50 and 100 mM) of lactate was required to reduce fibroblast survival in normoxia (69.1 ± 8.56% at 50 mM and 59.5 ± 8.66% at 100 mM; p<0.01 and p<0.001; Fig. 5F). Interestingly, when cultured in hypoxia, even 100 mM lactate failed to decrease cell survival in fibroblasts (Supporting information, Fig. S8B). These studies suggested that lactate alone induced a similar pattern of cell survival effects induced by CM derived from MCT4 overexpressing cells.

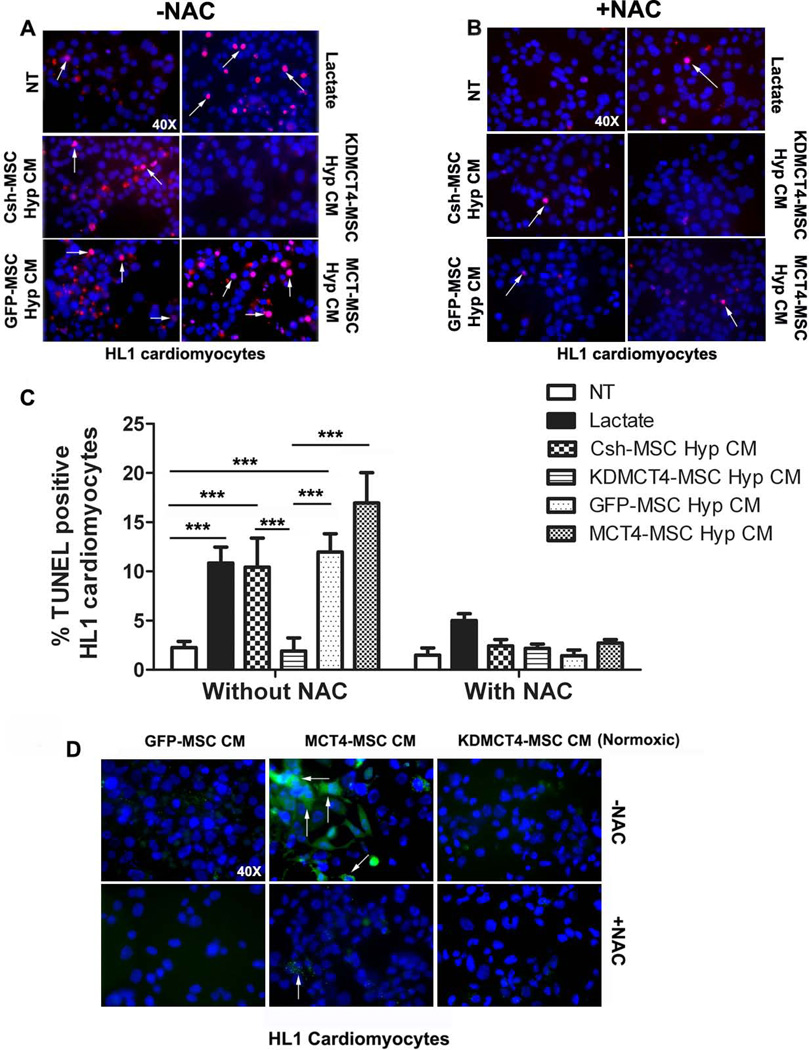

MCT4 MSC secretome induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis via reactive oxygen species generation

To identify the molecular basis of the cell death induced by MCT4-MSC secretome, HL1 cells were cultured in hypoxia in the presence of hypoxic and normoxic CM obtained from MCT4-MSCs, KDMCT4-MSCs and their respective controls. TUNEL assay was used to detect DNA fragmentation resulting from apoptosis (Fig. 6A). There was an increase in the percentage of TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes in the presence of hypoxic CM from GFP-MSCs (11.96 ± 1.86%; p<0.001), MCT4-MSCs (16.95 ± 3.80%; p<0.001), and Csh-MSCs (10.4 ± 2.96%; p<0.001), in comparison to no treatment (2.27 ± 0.60%; Fig. 6C). Conversely, KDMCT4-MSC hypoxic CM had a minimal effect on myocyte apoptosis (1.90 ± 1.3%). Lactate treatment, used as a positive control, also led to an increase in the number of TUNEL positive cells (10.85 ± 1.6 %; p<0.001). Treatment with MSC media alone had no effect on cardiomyocyte apoptosis (data not shown). As expected, normoxic CM from GFP-MSCs induced minimal cardiomyocyte apoptosis (3.028 ± 1.47%) whereas normoxic CM from MCT4-MSCs resulted in apoptosis (16.65 ± 2.365; p<0.01) (Supporting information, Fig. S9) comparable to hypoxic MSC CM (11.96 ± 1.43 Fig. 6A and C). The results herein elucidated that MCT4 overexpression as well as extended hypoxic conditioning of WT- MSCs alike generated a pro-apoptotic secretome for cardiomyocytes.

Figure 6.

MSCs overexpressing MCT4 secretome induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by activating reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. HL1 cardiomyocytes were treated for 24 hours in hypoxia with CM obtained from 5-day hypoxic culture of designated MSCs without (A and C) or with (B and C) N-acetyl cysteine (NAC). Cardiomyocyte cell death was measured by TUNEL staining. (A and B): Representative immunofluorescence images of cardiomyocytes (blue: 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear staining) with TUNEL positive (red) staining (40× magnification). Arrows indicate examples of TUNEL positive cells. (C): Quantification of cell death as % TUNEL positive cardiomyocytes assessed in 5 field of views (20× magnification, >200 cells were counted/ field of view, n=3 experiments/group). (D): HL1 cardiomyocytes were treated for 24 hours in hypoxia with normoxic CM obtained from 5-day culture of designated MSCs with or without N-acetyl cysteine (NAC). ROS production was assessed by labeling cardiomyocytes with CM-H2DCFDA for 15 minutes at 37°C. Representative fluorescent micrograph of cardiomyocytes (blue: DAPI nuclear staining) with ROS-detection reagent, CM-H2DCFDA (green) staining (40× magnification). Bar represent mean ±SD, ***p<0.001 was calculated using two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-test. n=3 experiments were performed in triplicate/group.

To determine if apoptosis was induced through activation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the oxidant-sensing probe CM-H2DCFDA was used. Strong staining for ROS in cells treated with normoxic MCT4-MSC CM was observed (Fig. 6D), and was significantly reduced when co-treated with ROS scavenger N-acetyl cysteine (NAC). Treatment with normoxic GFP-MSC CM or KDMCT4-MSC CM led to low numbers of ROS positive cells. Additionally, the addition of NAC to HL1 cells abrogated the adverse effects of CM derived from MCT4 over expressing MSCs or lactate determined by TUNEL staining (Fig. 6B and 6C). These results suggested that MCT4 expression induced a pro-apoptotic MSC secretome via induction of ROS.

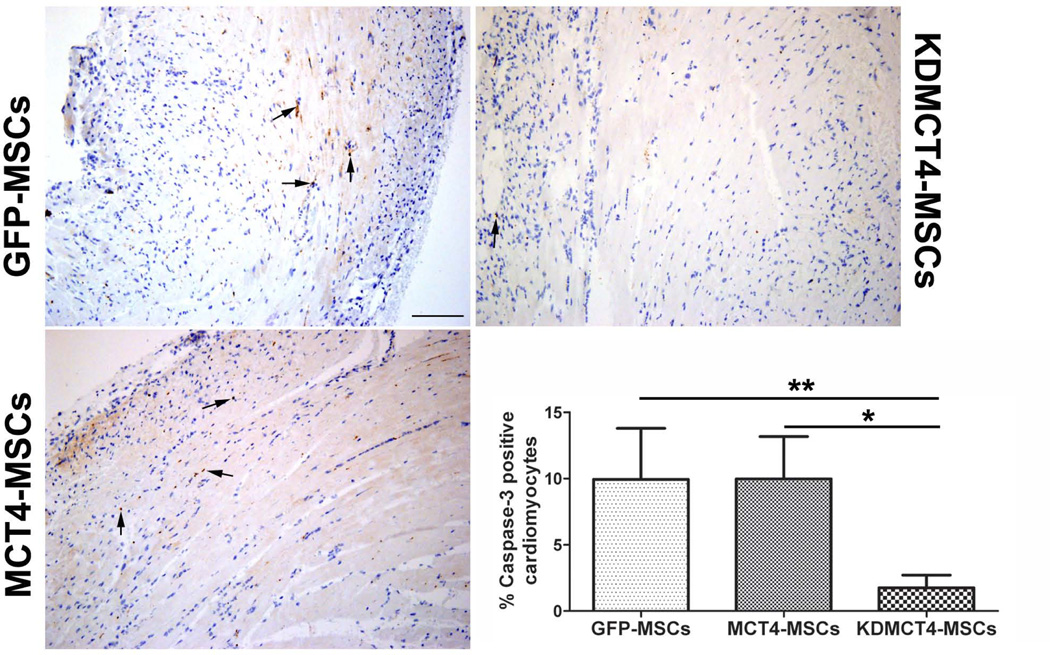

Inhibition of MCT4 expression in MSCs prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo

To test whether MCT4 overexpressing MSCs induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo, GFP-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs, and KDMCT4-MSCs were injected in the peri-infarct region of the left ventricle following MI. Mice were sacrificed on day 3 and caspase-3 IHC was performed. There was a considerable reduction in the percentage of activated caspase-3 cardiomyocytes in ventricles injected with KDMCT4-MSCs compared to GFP-MSCs (1.75 ± 0.957 vs. 9.94 ± 3.85; p<0.01) and MCT4-MSCs (1.75 ± 0.957 vs. 9.97 ± 3.19; p<0.05) (Fig. 7A and 7B). These results indicated that suppressing the expression of MCT4 (i.e. KDMCT4-MSCs) in MSCs significantly reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo.

Figure 7.

Knocking down MCT4 expression in MSCs prevented cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo. GFP-MSCs, MCT4-MSCs, and KDMCT4-MSCs were injected in the peri-infarct region of the left ventricle following MI induced by coronary artery ligation. Mice were sacrificed on day 3 and caspase-3 immunohistochemistry was performed. (A): Representative images of histological sections of anti-caspase-3 stained ventricle following MI. Black arrows indicate examples of caspase-3 positive cells. (B): Quantification of apoptosis as % active caspase-3 positive cardiomyocytes assessed in 5 field of views (>800 cells were counted/ field of view, n=3 /GFP-MSC and MCT4-MSC, and n=4/KDMCT4-MSC). Bar represent mean ±SD, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 were calculated using one way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test; scale bar=0.1 mm.

Discussion

Although MSCs are an attractive cell-therapy source for cardiac and wound regeneration, little is known about the effect of prolonged hypoxic exposure and its impact on MSC biology in ischemic wounds. In this study, we identified significant upregulation of the lactate transporter MCT4 in MSCs after prolonged hypoxia. We found that upregulation of MCT4 had minimal impact on MSC survival and proliferation in vitro, but to our surprise adversely affected MSC-based post-MI repair via its effect on the MSC secretome. Moreover, the observation that MCT4-modulated secretome preferentially induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis (but not fibroblast death) in vitro would predict a shift towards fibrosis rather than organ repair.

It is common for cancer cells to adapt quickly to the hypoxic tumor milieu and switch their metabolism based on the availability of substrate and oxygen [26]. Our findings support previous reports that MSCs similarly shift toward glycolysis following prolonged hypoxic exposure [15]. Although the hypoxic niche has been shown to have no adverse effect on stem cell multipotency and self-renewal properties [27], little is known about the molecular changes in MSCs during prolonged hypoxia and the impact of these changes on MSC-based repair.

Enhanced ability to efflux lactic acid is a hallmark of tumor cells; MCTs, including MCT4, are widely known to maintain the energetics of glycolytic tumors [28, 29]. Besides tumors, MCT4 expression is elevated in various other cell types with hypoxic exposure. HUVECs have also been shown to upregulate MCT4 in hypoxia [30]. However, in this study we found that the extent of MCT4 transcript upregulation in MSCs was 4.49 fold higher than in HUVECs after 72 hours of hypoxia. Moreover, the absence of MCT4 transcript upregulation in the mouse fibroblast line NIH3T3 suggests that the observed upregulation of MCT4 is not shared by all stromal or mesenchymal cells.

MCT4 belongs to a family of integral membrane transporter proteins [31]. MCTs facilitate the transport of monocarboxylates such as lactate, pyruvate, and ketone bodies across the plasma membrane. Presently, 14 putative members of the MCT family have been reported. Only 4 of these members have been functionally shown to transport lactate and pyruvate together with H ions. In highly glycolytic muscles, the low affinity of MCT4 towards pyruvate (Km ~150 mM) compared with lactate (Km ~28 mM) has been argued to be the key for MCT4’s prominent role in lactate efflux [25]. Due to MCT4’s preference towards lactate efflux, it seems logical that MCT4 might protect MSCs from acidosis by extruding lactate during intense hypoxic exposure and thereby improve their survival. However, MCT overexpression or knockdown had no significant effect on their survival or proliferation in hypoxia in vitro, suggesting that the observed cardiac functional differences incurred by MCT4-MSC and KDMCT4-MSC transplantations were not due to the differences in MSC survival and engraftment in the injured myocardium.

The significance of MCT4 upregulation in MSCs was explored by administering genetically modified WT-MSCs overexpressing MCT4 in a murine model of acute MI. Surprisingly, we found no evidence of improved cardiac function, improved remodeling, or reduced infarct size between GFP-MSC and MCT4-MSC. In fact, we observed a trend towards a decline in myocardial function in animals treated with MCT4-MSC. Moreover, MSCs with knocked down expression of MCT4 improved myocardial function and showed attenuation in adverse cardiac remodeling and infarct size.

It is widely hypothesized that MSC-based repair is largely mediated by MSC-derived paracrine factors [32–34]. This led us to consider if MCT4 expression levels altered the MSC secretome. MCT4-MSC CM significantly reduced cardiomyocyte survival, whereas KDMCT4-MSC secretome had no effect on cardiomyocyte death. Interestingly, fibroblasts were resistant to cell death induced by MCT4-MSC CM. These observations were further confirmed in vivo with the identification of a higher percentage of peri-infarct cardiomyocyte apoptosis following MCT4 overexpressing MSC (GFP-MSCs exposed to hypoxia and MCT4-MSCs) treatment in comparison to KDMCT4-MSCs. Additionally, KDMCT4-MSCs produced significantly less lactate when cultured in hypoxia vs. normoxia (50–54% less) when compared to GFP-MSCs, Csh-MSCs, and MCT4-MSCs. Altogether, our data suggest that prolonged hypoxic exposure upregulated MCT4 in MSCs and generated a more deleterious, lactate-rich, profibrogenic MSC secretome in vitro and in vivo. Inhibition of MCT4 expression (i.e. in KDMCT4-MSCs), prevented cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improved MSC-based therapy.

Since MCT4 predominantly effluxes lactate [25], we tested and showed that lactate itself can induce cardiomyocyte apoptosis while promoting fibroblast survival. The positive effect of lactate on fibroblast survival has been previously reported [35]. Lactate concentration in wound fluid ranges from 5.4–16.7 mM [36]. Our results also showed cardiomyocyte death at lactate concentrations of 5.5 mM and higher. Since a single dose of 2.5×105 MSCs were injected at multiple peri-infarct sites after experimental MI, it is difficult to reconcile that a relatively small number of MSCs may be able to increase local lactate concentration. One possibility is that lactate may primarily act as a signaling molecule. In human colorectal and breast cancer it has been shown that lactate released from tumor cells through MCT4 can signal to the neighboring endothelial cells and activate reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [37]. Indeed our results also demonstrated that MSC CM containing lactate (from MCT4-MSC) activated ROS generation in cardiomyocytes whereas normoxic GFP-MSC and KDMCT4-MSC CM had minimal effects on ROS generation in myocytes.

Activation of ROS generation by lactate signaling, facilitated by lactate extrusion by MCT4 and intrusion by MCT1, has been previously documented [37, 38]. However, lactate has been noted to have positive as well as negative effects depending on the disease context. Lactate is postulated to serve as an energy source to preserve myocardial performance in a congestive heart failure model [39]. Moreover, the role of lactate in cardiomyocyte biology may also vary depending upon the confirmation of the lactate enantiomer [40, 41].

Our study has identified that prolonged hypoxia resulted in unique changes in MSC metabolism, specifically, the dramatic upregulation of the lactate effluxer, MCT4. Importantly, our studies suggested that MCT4 upregulation ultimately had a negative impact on MSC-based cardiac repair by impairing cardiomyocyte survival and promoting fibrosis. Strategies to avert or counteract this metabolic response may augment MSC-based cardiac repair.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01-HL088424, HL08842402S1, RO1-GM081635; Veterans Affairs merit award (PPY) and American Heart Association 11POST7530010 (SS). The authors would like to thank Dr. Susan R. Opalenik and Dr. Jeffrey M. Davidson for their generous gift of a mouse primary fibroblast cell line. The authors would also like to thank Desirae L. Deskins for her technical help.

Footnotes

Author contribution summary:

S.S: Conception and design, financial support, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing

Y.G.: Data analysis and interpretation

J.A.: Data analysis and interpretation

P.P.Y.: Conception and design, financial support, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript

Potential conflicts of interest

There is no potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Med. 1999;5:309–313. doi: 10.1038/6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei X, Yang X, Han ZP, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new trend for cell therapy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:747–754. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. National Library of Medicine USNIoH. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Clinicaltrials.gov: Lester Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications

- 4.Trounson A, Thakar RG, Lomax G, et al. Clinical trials for stem cell therapies. BMC Med. 2011;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hare JM, Traverse JH, Henry TD, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2277–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katritsis DG, Sotiropoulou PA, Karvouni E, et al. Transcoronary transplantation of autologous mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial progenitors into infarcted human myocardium. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;65:321–329. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Z, Zhang F, Ma W, et al. A novel approach to transplanting bone marrow stem cells to repair human myocardial infarction: delivery via a noninfarct-relative artery. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;28:380–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2009.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young PP, Schafer R. Cell-based therapies for cardiac disease: a cellular therapist's perspective. Transfusion. 2014 doi: 10.1111/trf.12826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, et al. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nat Med. 2004;10:858–864. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu X, Yu SP, Fraser JL, et al. Transplantation of hypoxia-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells improves infarcted heart function via enhanced survival of implanted cells and angiogenesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:799–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Xue W, Ge G, et al. Hypoxic preconditioning advances CXCR4 and CXCR7 expression by activating HIF-1alpha in MSCs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;401:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosova I, Dao M, Capoccia B, et al. Hypoxic preconditioning results in increased motility and improved therapeutic potential of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2173–2182. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basciano L, Nemos C, Foliguet B, et al. Long term culture of mesenchymal stem cells in hypoxia promotes a genetic program maintaining their undifferentiated and multipotent status. BMC Cell Biol. 2011;12:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-12-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai CC, Chen YJ, Yew TL, et al. Hypoxia inhibits senescence and maintains mesenchymal stem cell properties through down-regulation of E2A-p21 by HIF-TWIST. Blood. 2011;117:459–469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-287508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu SH, Chen CT, Wei YH. Inhibitory effects of hypoxia on metabolic switch and osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2779–2788. doi: 10.1002/stem.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong F, Harvey J, Finan A, et al. Myocardial CXCR4 expression is required for mesenchymal stem cell mediated repair following acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:314–324. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.082453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noiseux N, Gnecchi M, Lopez-Ilasaca M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing Akt dramatically repair infarcted myocardium and improve cardiac function despite infrequent cellular fusion or differentiation. Mol Ther. 2006;14:840–850. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halestrap AP, Price NT. The proton-linked monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) family: structure, function and regulation. Biochem J. 1999;343(Pt 2):281–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson MC, Jackson VN, Heddle C, et al. Lactic acid efflux from white skeletal muscle is catalyzed by the monocarboxylate transporter isoform MCT3. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15920–15926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.15920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfeffer MA, Pfeffer JM, Fishbein MC, et al. Myocardial infarct size and ventricular function in rats. Circ Res. 1979;44:503–512. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palomaki S, Pietila M, Laitinen S, et al. HIF-1alpha is upregulated in human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2013;31:1902–1909. doi: 10.1002/stem.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saraswati S, Deskins DL, Holt GE, et al. Pyrvinium, a potent small molecule Wnt inhibitor, increases engraftment and inhibits lineage commitment of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugrue T, Lowndes NF, Ceredig R. Hypoxia enhances the radioresistance of mouse mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:2188–2200. doi: 10.1002/stem.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Jr, Stallworth BS, et al. HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manning Fox JE, Meredith D, Halestrap AP. Characterisation of human monocarboxylate transporter 4 substantiates its role in lactic acid efflux from skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2000;529(Pt 2):285–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones RG, Thompson CB. Tumor suppressors and cell metabolism: a recipe for cancer growth. Genes Dev. 2009;23:537–548. doi: 10.1101/gad.1756509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohyeldin A, Garzon-Muvdi T, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curry JM, Tuluc M, Whitaker-Menezes D, et al. Cancer metabolism, stemness and tumor recurrence: MCT1 and MCT4 are functional biomarkers of metabolic symbiosis in head and neck cancer. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:1371–1384. doi: 10.4161/cc.24092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gotanda Y, Akagi Y, Kawahara A, et al. Expression of monocarboxylate transporter (MCT)-4 in colorectal cancer and its role: MCT4 contributes to the growth of colorectal cancer with vascular endothelial growth factor. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2941–2947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ord JJ, Streeter EH, Roberts IS, et al. Comparison of hypoxia transcriptome in vitro with in vivo gene expression in human bladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:346–354. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halestrap AP, Wilson MC. The monocarboxylate transporter family--role and regulation. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:109–119. doi: 10.1002/iub.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gnecchi M, He H, Liang OD, et al. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:367–368. doi: 10.1038/nm0405-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ranganath SH, Levy O, Inamdar MS, et al. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salgado AJ, Gimble JM. Secretome of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in regenerative medicine. Biochimie. 2013;95:2195. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner S, Hussain MZ, Hunt TK, et al. Stimulation of fibroblast proliferation by lactate-mediated oxidants. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12:368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.012315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trengove NJ, Langton SR, Stacey MC. Biochemical analysis of wound fluid from nonhealing and healing chronic leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 1996;4:234–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1996.40211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vegran F, Boidot R, Michiels C, et al. Lactate influx through the endothelial cell monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 supports an NF-kappaB/IL-8 pathway that drives tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2550–2560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuvel DJ, Sundararaj KP, Nareika A, et al. Lactate boosts TLR4 signaling and NF-kappaB pathway-mediated gene transcription in macrophages via monocarboxylate transporters and MD-2 up-regulation. J Immunol. 2009;182:2476–2484. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johannsson E, Lunde PK, Heddle C, et al. Upregulation of the cardiac monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 in a rat model of congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:729–734. doi: 10.1161/hc3201.092286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ling B, Peng F, Alcorn J, et al. D-Lactate altered mitochondrial energy production in rat brain and heart but not liver. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu Y, Wu J, Yuan SY. MCT1 and MCT4 expression during myocardial ischemic-reperfusion injury in the isolated rat heart. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;32:663–674. doi: 10.1159/000354470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.