Abstract

Objective

The deficiency of very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) resulted in Wnt signaling activation and neovascularization (NV) in the retina. The present study sought to determine if the VLDLR extracellular domain (VLN) is responsible for the inhibition of Wnt signaling in ocular tissues.

Approach and Results

A plasmid expressing the soluble VLN was encapsulated with poly (lactide-co-glycolide acid) (PLGA) to form VLN nanoparticles (VLN-NP). Nanoparticles containing a plasmid expressing the low-density lipoprotein receptor extracellular domain (LN-NP) were used as negative control. MTT, modified Boyden chamber and Matrigel (™) assays were used to evaluate the inhibitory effect of VLN-NP on Wnt3a-stimulated endothelial cell (EC) proliferation, migration and tube formation. Vldlr−/− mice, oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) and alkali burn-induced corneal NV models were used to evaluate the effect of VLN-NP on ocular NV. Wnt reporter mice (BAT-gal), Western blotting and luciferase assay were used to evaluate Wnt pathway activity. Our results showed that VLN-NP specifically inhibited Wnt3a-induced EC proliferation, migration and tube formation. Intravitreal injection of VLN-NP inhibited abnormal NV in Vldlr−/−, OIR and alkali burn-induced corneal NV models, compared with LN-NP. VLN-NP significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of LRP6, the accumulation of β-catenin and the expression of VEGF in vivo and in vitro.

Conclusions

Taken together, these results suggest that the soluble VLN is a negative regulator of the Wnt pathway and has anti-angiogenic activities. Nanoparticle-mediated expression of VLN may thus represent a novel therapeutic approach to treat pathologic ocular angiogenesis and potentially other vascular diseases impacted by Wnt signaling.

Keywords: nanoparticle, VLDLR, Wnt, eye, neovascularisation

Introduction

Ocular neovascularization (NV) is a major cause of irreversible visual loss in a number of eye diseases, such as proliferative diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, retinopathy of prematurity and traumatic corneal injury1–3. The treatments for these diseases are not satisfactory due to the limited understanding of pathogenesis of ocular NV and the poor drug delivery due to the ocular barriers4, 5.

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway regulates a wide array of developmental and physiological processes, including proliferation, migration, differentiation and apoptosis by activating transcription of multiple target genes6. Previous studies have reported that the Wnt signaling pathway participates in the regulation of angiogenesis7. In the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, Wnt ligands bind to a cell surface receptor complex consisting of frizzled receptors and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6), leading to stabilization of cytoplasmic β-catenin by attenuating its phosphorylation. Non-phosphorylated-β-catenin (n-p-β-catenin) translocates into the nucleus, where it associates with T cell factor (TCF) to activate the transcription of Wnt target genes including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)8, which is a key causative factor in ocular angiogenesis9. Although several Wnt pathway inhibitors, such as Dickkopf1 (DKK1), have been identified, the regulation of Wnt signaling is not well understood.

Very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) is a membrane receptor originally known to mediate lipid transport10. It was reported later that Vldlr−/− mice develop abnormal retinal and sub-retinal NV11, 12. Our previous study has shown that VLDLR deficiency results in Wnt signaling over-activation in the retina, which is responsible for retinal NV, suggesting an inhibitory effect of VLDLR on Wnt signaling and retinal NV13. VLDLR belongs to the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene family and is a highly conserved integral membrane protein consisting of a large ectodomain, a single transmembrane domain and an intracellular domain14. The specific functional domain of VLDLR for the interaction with Wnt signaling has not been clearly defined. We hypothesized that the VLDLR N-terminal ectodomain (VLN) is responsible for the inhibitory effect on Wnt signaling, as VLDLR is known to shed VLN into the extracellular space as a soluble peptide15. Our previous work has shown that VLN is efficient to block Wnt signaling in vitro16, while the present study generated nanoparticles capsulated with a plasmid-mediated expression of the soluble VLN with His tag to evaluate the inhibitory effect of VLN on retinal NV and Wnt signaling in vivo. At the same time, nanoparticles expressing the extracellular domain of LDLR (LN) with Myc tag was used as a control, since previous studies showed that LDLR knockout does not affect the Wnt signaling pathway or result in neovascular phenotype17, 18.

Due to the ocular barriers, including the corneal barrier, aqueous barrier, the inner and outer blood-retinal barriers, it is always challenging to deliver large molecules such as peptides and DNA into the retina. Intravitreal injection is commonly used to deliver genes or proteins into the retina. Since these molecules remain in the eye for only short durations, repetitive injections are needed, which is accompanied by problems such as cataract, vitreous hemorrhage and endophthalmitis. Nanoparticles have been applied to improve penetration, controlled and sustained release of drugs, and drug targeting19. Several groups have successfully encapsulated naked DNA into biodegradable poly (lactide-co-glycolide acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles for long-term and controlled DNA release20, 21.

To study the role of VLN in the regulation of Wnt signaling and ocular NV, we encapsulated an expression plasmid of VLN or LN with PLGA polymer to form VLN-NP/LN-NP and evaluated the efficacy of VLN-NP on Wnt3a-induced proliferation, migration and tube formation of endothelial cells (EC) and on ocular NV in ocular NV models, including Vldlr−/− mice, oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) model and alkali burn-induced corneal NV model.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Methods are available in the online-only Supplement.

Results

VLN-NP mediated expression of VLN in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMEC)

VLN-NP and LN-NP had a low polydispersity (≤ 0.2), indicating a narrow particle size distribution and were negatively charged. The plasmid loading was 1.1% and 0.9% in VLN-NP and LN-NP, respectively (Suppl. Table).

The conditioned serum-free media (3-fold) from primary HRMEC were harvested 72 hr after the transfection of VLN-NP and LN-NP and concentrated. As shown by Western blot analysis, both of the anti-His-tag and anti-VLN antibodies detected significant amounts of the VLN peptide with the expected molecular weight (100 kDa) in the conditioned medium from the cells transfected with VLN-NP, but not in that from the cells transfected with LN-NP (Fig. 1A). On the contrary, an anti-Myc-tag antibody detected the expression of LN-Myc only from the cells transfected with LN-NP (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. VLN-NP mediated expression and activity of VLN in HRMEC.

A: Conditioned media of VLN-NP or LN-NP were concentrated 3-fold and used for Western blotting. B: HRMEC were quantified with MTT assay at indicated durations of VLN-NP or LN-NP treatment. **p<0.01, n=6. C: HRMEC were quantified after treatment with VLN-NP or LN-NP for 72 hr in the presence of LCM or WCM. **p < 0.01, n=6. D, F: HRMEC were seeded on one side of the membrane in the insert and treated with VLN-NP or LN-NP in the presence of WCM or LCM for 12 hr. The cells migrated to the other side of the membrane were stained, and micrographs captured (D), and cells counted in five fields per insert (F). **p<0.01, n=3. E, G: HRMEC were treated with VLN-NP and LN-NP for 72 hr, seeded on Matrigel-coated plates and incubated with WCM or LCM at 37°C for 6 hr. E: Representative micrographs of tube formation (×200). G: Branching points were counted in five fields per dish. **p<0.01, n=3. H: HRMEC were transfected with a VLDLR siRNA or a control siRNA after incubation with VLN-NP or LN-NP for 48 hr for additional 24 hr. Cells were then quantified with MTT assay. **p<0.01, n=6.

VLN-NP inhibits HRMEC growth induced by Wnt3a and small interfering RNA (siRNA) of VLDLR

As shown by MTT assay in HRMEC at various time points following transfection, VLN-NP significantly decreased HRMEC viability at 48 and 72 hr post-transfection, compared to the LN-NP-transfected cells (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, VLN-NP specifically attenuated Wnt3a-induced HRMEC growth, compared with LN-NP (Fig. 1C). In addition, the siRNA knockdown of VLDLR resulted in increased numbers of viable HRMEC, which is consistent with a previous study22, while VLN-NP decreased viable HRMEC, diminishing the effect of the VLDLR siRNA (Fig. 1H).

VLN-NP suppresses Wnt3a-stimulated HRMEC migration and tube formation

HRMEC migration was measured using the transwell chamber assay. As shown in Figure 1D and F, Wnt3a conditioned medium (WCM) stimulated HRMEC migration compared with L cell conditioned medium (LCM). VLN-NP, but not LN-NP, significantly suppressed the EC migration induced by WCM.

Tube formation assay demonstrated that WCM induced tubes formation in HRMEC, while VLN-NP significantly suppressed WCM-induced EC tube formation (Fig. 1E, G).

VLN-NP inhibits Wnt3a-induced activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in vitro

To evaluate the modulation of Wnt signaling by VLN in vitro, HRMEC were transfected with VLN-NP or LN-NP. WCM was used to induce Wnt signaling compared to the LCM control. WCM up-regulated the levels of phosphorylated LRP6 (p-LRP6), total LRP6 (t-LRP6), n-p-β-catenin and VEGF, compared to LCM (Fig. 2A–D). VLN-NP dramatically blocked the increases of LRP6, n-p-β-catenin and VEGF levels induced by WCM (Fig. 2A–D).

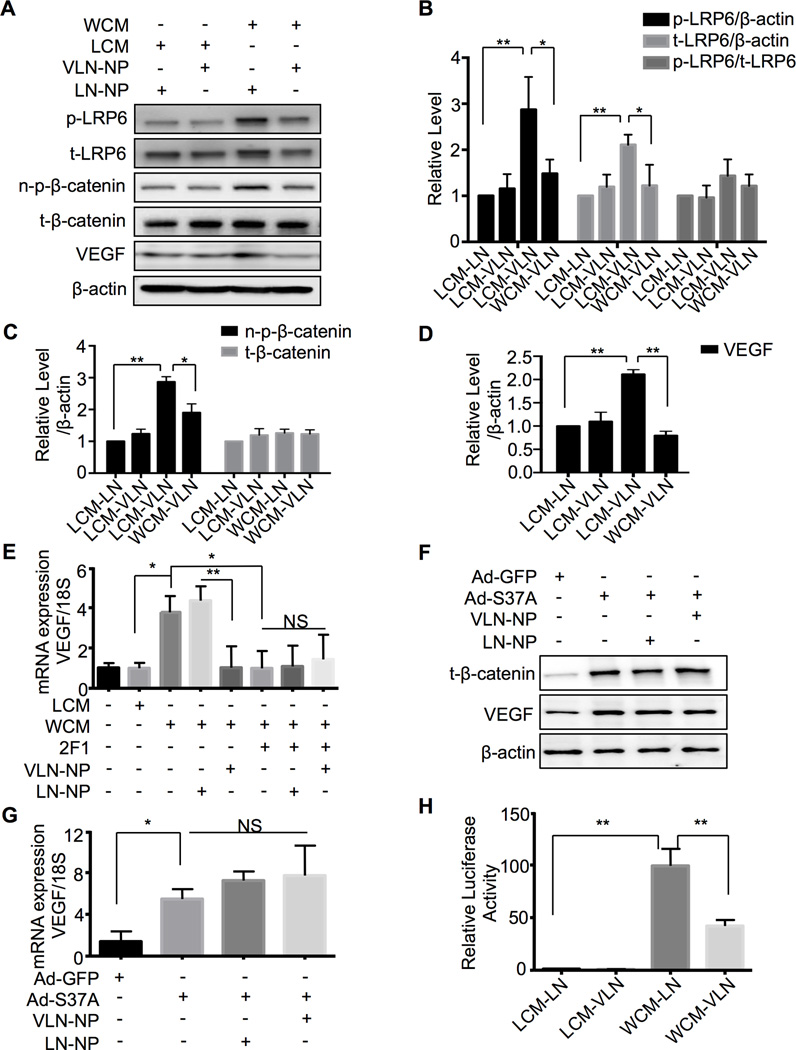

Fig. 2. VLP-NP suppresses Wnt signaling activated by Wnt ligand in cultured cells.

A: HRMEC were transfected with VLN-NP or LN-NP for 48 hr and treated with LCM or WCM for 4 hr (p-LRP6, t-LRP6, n-p-β-catenin, t-β-catenin) or 24 hr (VEGF). Levels of p-LRP6, t-LRP6, n-p-β-catenin, t-β-catenin and VEGF in the cell lysates were measured by Western blot analysis. B–D: Semi-quantification of p-LRP6 and t-LRP6 (B), n-p-β-catenin and t-β-catenin (C), and VEGF (D) levels by densitometry and normalized by β-actin levels. **p<0.01, * p<0.05, n=3. E: HRMEC were transfected with VLN-NP or LN-NP for 48 hr and treated with Mab2F1 (50 µg/ml) 4 hr before adding LCM/WCM for additional 24 hr. VEGF mRNA levels were measured by q-PCR and normalized by 18S. **p<0.01, * p<0.05, NS: not significant, n=3; F, G: HRMEC were transfected with VLN-NP or LN-NP for 48 hr and infected with Ad-GFP/Ad-S37A for additional 24 hr. T-β-catenin and VEGF protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis (F), and VEGF mRNA levels were measured by q-PCR and normalized by 18S (G). H: hTERT-RPE cells were transfected with TOPFLASH vectors and then treated as indicated for 24 hr. TOPFLASH activity was measured using Luciferase assay and expressed as the firefly/renilla ratio relative to that of LCM-LN group. **p<0.01, n=3.

Transcriptional activity of TCF/β-catenin was measured using TOPFLASH assay. As shown in Figure 2H, WCM increased luciferase activity by almost 100 fold, while VLN-NP reduced the activity by 60%, compared to LN-NP (Fig. 2H), suggesting that VLN-NP directly inhibits Wnt signaling induced by Wnt ligand in EC.

To determine if the regulation of VLN on VEGF is through the Wnt signaling pathway, we used a monoclonal antibody Mab2F1, which specifically blocks the ligand-binding site of the Wnt co-receptor LRP623. The results showed that Mab2F1 successfully blocked the VEGF expression induced by WCM (Fig. 2E), and abolished the inhibitory effect of VLN-NP on Wnt3a-induced VEGF up-regulation (Fig. 2E), suggesting that VLN-NP mediated VEGF suppression acts exclusively through Wnt inhibition. Moreover, an adenovirus expressing a constitutively active mutant of β-catenin (Ad-S37A) was used to induce VEGF over-expression in the absence of Wnt ligand, and the VEGF expression induced by this active mutant of β-catenin was not blocked by VLN-NP as shown at the protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 2F, G). Together, these results suggest that the suppression of VEGF expression by VLN-NP is through inhibiting the Wnt signaling pathway, which occurs at the LRP6 co-receptor level.

VLN-NP mediates sustained expression of VLN in the retina

To examine the expression and duration of the genes delivered by nanoparticles in the retina, VLN-NP were injected intravitreally (50 µg/eye), with LN-NP as control, and then the retinas were dissected at 1, 2, 3 and 4 weeks (three mice per time point) following the injection. VLN was detected with an expected molecular weight in the retinas injected with VLN-NP at all of the time points analyzed by Western blotting analysis using the anti-His-tag antibody, but not in the retinas injected with LN-NP (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Anti-angiogenic activity of VLN-NP in the retina.

A: Expression of VLN in the mouse retinas was measured using Western blot analysis at 1, 2, 3 and 4 weeks following an intravitreal injection of VLN-NP. B: Representative retinal angiographs of Vldlr−/− (VKO) mice(upper panels, ×40; lower panels, higher magnification of the boxed areas). VLN-NP was injected into the VKO eyes on P10, with LN-NP as control. Retinal angiography was performed on P30. C: Quantification of intra-retinal neovascular blebs (IRN blebs) in VKO mice treated with VLN-NP or LN-NP. **p<0.01, n=6. D: Immunostaining of BS-1 lectin (green) in VKO retinal sections. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue) (×200). Arrows indicate abnormal vessels in the retinas. GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer; RPE: retinal pigment epithelium. E–H: VLN-NP or LN-NP was intravitreally injected into OIR mice on P12 and retinal NV analyzed at P17. E: Representative retinal angiographs (upper panels, ×40; lower panels, higher magnification of the boxed areas). F: Quantification of non-perfusion area in the retina. **p<0.01, n=6. G: Representative retinal sections with H&E staining. Arrows indicate pre-retinal vascular cells (×200). H: Quantification of pre-retinal vascular cells. **p<0.01, n=6.

VLN-NP has no detectable toxicities to the structure and function of the retina

To detect the possible adverse effect of VLN-NP and LN-NP on visual functions, electroretinography (ERG) recording was employed in the treated eyes and eyes 4 weeks after intravitreal injection of VLN-NP and LN-NP. The amplitudes of A- or B-waves of scotopic and photopic ERG in the VLN-NP-treated group were not significantly different among the untreated mice and /LN-NP treated mice (Suppl. Fig. 1A, B).

Possible toxicities of VLN-NP were also evaluated by histological examination. No difference was observed in the number of retinal nuclear layers or thickness of the retina among the mice injected with VLN-NP, LN-NP and the control (Suppl. Fig. 1C).

VLN-NP inhibits retinal NV in Vldlr−/− mice

As shown by angiography of the flat-mounted whole retinas, Vldlr−/− mice developed small, irregular in shape (coiled or enlarged) intra-retinal neovascular (IRN) blebs throughout the retina, which is consistent with a previous report24 (Fig. 3B). The injection of VLN-NP significantly reduced numbers of IRN blebs in Vldlr−/− eyes, compared to those with the LN-NP injection (Fig. 3B, C).

BS-1 lectin staining of retinal sections showed decreased vascular density and less abnormal vessels in outer nuclear level of the retina in Vldlr−/− retinas after the VLN-NP injection, compared with those in the retina with LN-NP injection (Fig. 3D).

VLN-NP inhibits the Wnt signaling pathway in the retina of Vldlr−/− mice

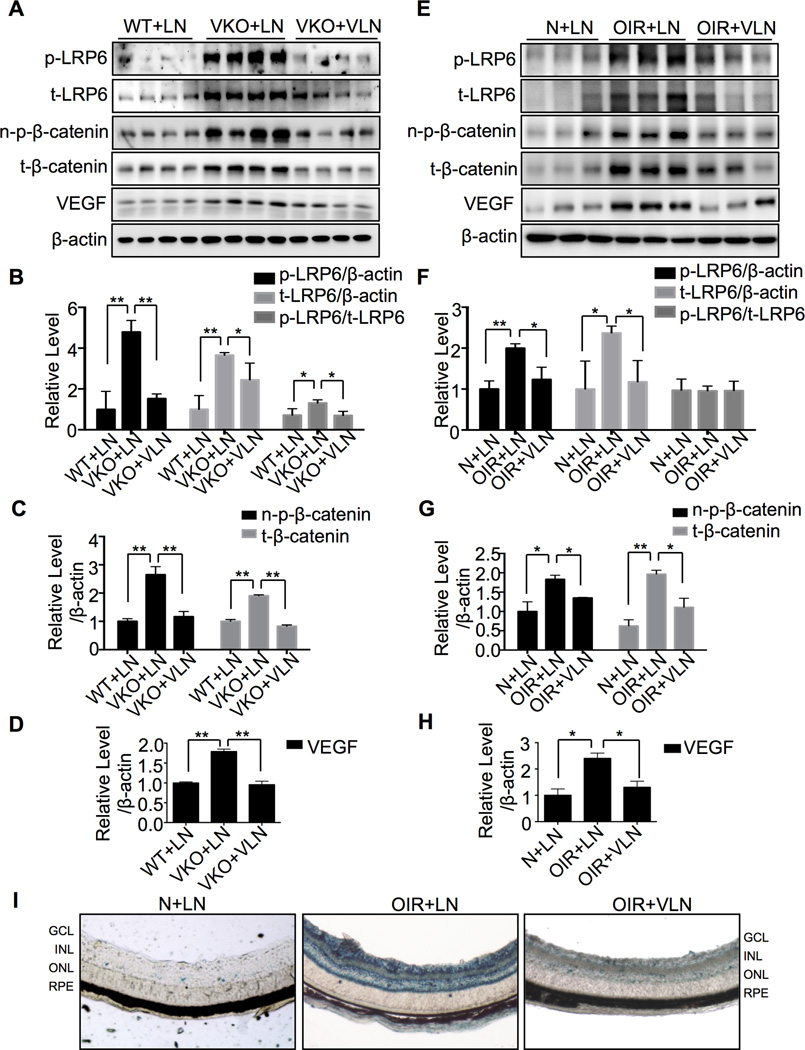

Levels of p-LRP6, t-LRP6, n-p-β-catenin, total β-catenin (t-β-catenin) and VEGF were significantly elevated in the eyecups of Vldlr−/− mice with LN-NP injection, compared to wild-type (WT) mice with LN-NP injection at age of P30, suggesting the activation of Wnt signaling in the Vldlr−/− retinas (Fig. 4A–D). A single injection of VLN-NP into Vldlr−/− vitreous at P10 abolished the up-regulation of p-LRP6, t-LRP6, n-p-β-catenin, t-β-catenin and VEGF levels, suggesting that VLN is the functional domain responsible for the inhibition of the Wnt pathway (Fig. 4A–D).

Fig. 4. The inhibition of Wnt signaling by VLN-NP in Vldlr−/− and OIR mice.

A–D: Eyecups were isolated at P30 from LN-NP-treated WT (WT+LN), LN-NP-treated Vldlr−/− (VKO+LN) and VLN-NP-treated Vldlr−/− (VKO+VLN) group. Levels of proteins were measured by Western blot analysis (A). Each lane represents an individual animal. Densitometry was performed to semi-quantify p-LRP6 and t-LRP6 (B), n-p-β-catenin and t-β-catenin (C), and VEGF (D) which were normalized by β-actin levels. **p<0.01, *p<0.05, n=4. E–H: The retinas were dissected on P17 from LN-NP-treated Normoxia (N+LN), LN-NP-treated OIR (OIR+LN) and VLN-NP-treated OIR (OIR+VLN) groups. Levels of protein were measured by Western blot analysis (E). Densitometry was performed to semi-quantify p-LRP6 and t-LRP6 (F), n-p-β-catenin, t-β-catenin (G), and VEGF (H) levels, which were normalized by β-actin levels. **p<0.01, *p<0.05, n=3. I: X-gal staining of retinal sections: VLN-NP or LN-NP was injected intravitreally into BAT-gal mice (50 µg/eye) with OIR at P12. The retinas were dissected at P17 and sectioned, and β-galactosidase activities were evaluated by X-gal staining (blue). GCL: ganglion cell layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer; RPE: retinal pigment epithelium.

VLN-NP alleviates ischemia-induced retinal NV in OIR mice

As shown by fluorescein angiography, severe NV and enlarged non-perfusion area were exhibited in the flat-mounted retinas in the OIR mice treated with LN-NP, while the VLN-NP-treated OIR mice displayed alleviated retinal NV and dramatically smaller non-perfusion areas (Fig. 3E, F). Moreover, the VLN-NP-treated OIR group developed significantly fewer pre-retinal vascular cells, in comparison to LN-NP-treated OIR mice (Fig. 3G, H), supporting an inhibitory effect of VLN-NP on ischemia-induced retinal NV.

VLN-NP inhibits the Wnt signaling pathway in OIR mice

Our group has previously shown that the Wnt pathway is activated in the retina of OIR model, which contributes to the retinal NV23. A single injection VLN-NP attenuated the elevations of p-LRP6, t-LRP6, n-p-β-catenin, t-β-catenin and VEGF levels in the retina of OIR animals (Fig. 4E–H).

We also evaluated the effect of VLN-NP on Wnt signaling activity using the Wnt reporter mice, BAT-gal transgenic mice that express the β-galactosidase gene under the control of a promoter containing TCF/β-catenin-binding sites. As shown by X-gal staining, the retina with OIR showed more intense blue color, compared to that of age-matched normal mice, suggesting Wnt pathway activation induced by OIR. The injection of VLN-NP decreased blue color in the retina of OIR mice, compared to LN-NP-treated OIR retinas (Fig. 4I), indicating that VLN-NP down-regulates Wnt signaling in the OIR retinas.

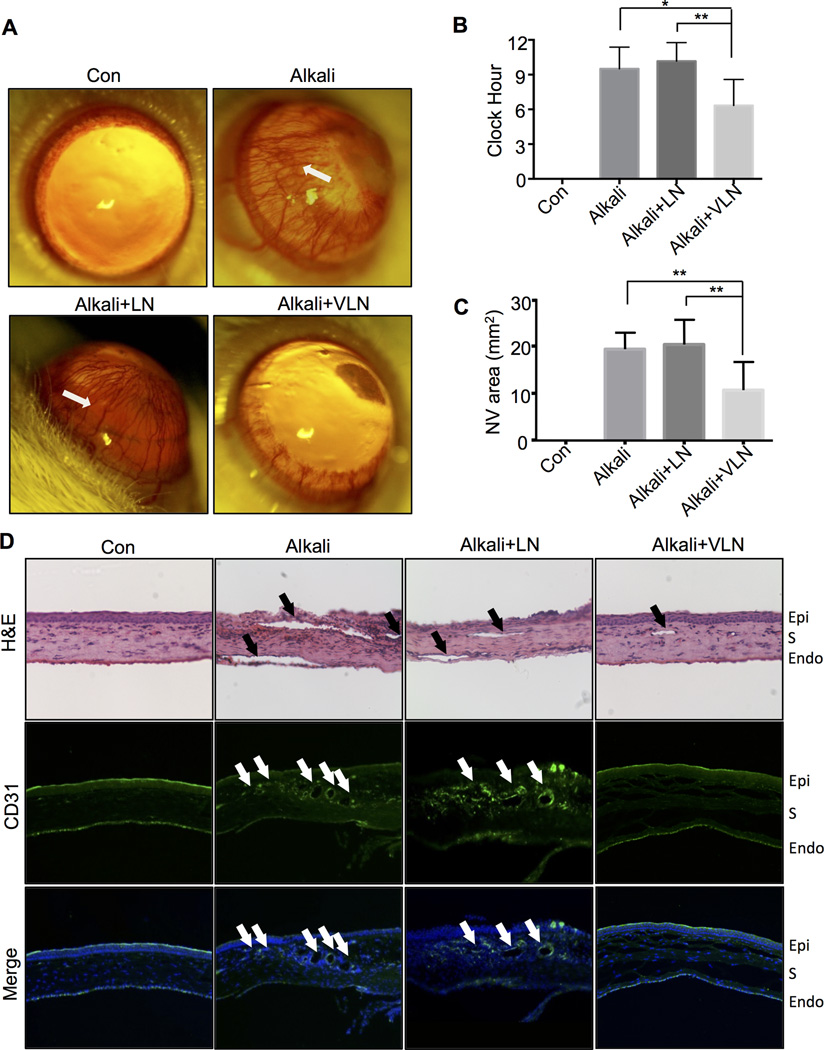

VLN-NP ameliorates alkali burn-induced corneal NV

Corneal NV was induced with alkali burn in rats, as shown in corneal images, 7 days after the alkali burn25. A single topical treatment of VLN-NP (20 µl, 10 mg/ml) at the procedure day of alkali burn substantially reduced corneal NV induced by alkali burn at day 7 after treatment, compared to the same dose of LN-NP (Fig. 5A). Quantitatively, VLN-NP significantly reduced NV severity in the alkali burn model, compared to LN-NP, as measured by corneal NV clock hour (Fig. 5B) and vascularized area (Fig. 5C). H&E and CD31 staining of corneal sections showed that the VLN-NP-treated group developed fewer vessels in the cornea with alkali burn, compared to un-treated and LN-NP-treated groups (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5. The effect of VLN-NP in rat alkali burn-induced corneal NV model.

VLN-NP or LN-NP was administered topically onto the cornea 1 hr after alkali burn, and photographs were taken on day 7 following the administration. A: Representative photographs of rat corneas with indicated treatments. Arrows indicate corneal NV areas. B, C: Quantification of corneal NV by NV clock hour (B) and area (C) in each group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, n=6. D: Representative rat cornea sections with H&E staining and immunostaining of an anti-CD31 antibody (green), and the nuclei counterstained with DAPI (blue). Magnification ×100. Arrows indicate NV areas in the cornea. Epi: epithelium; S: stroma; Endo: endothelium.

VLN-NP suppresses the Wnt signaling pathway in the rat cornea with alkali burn-induced NV

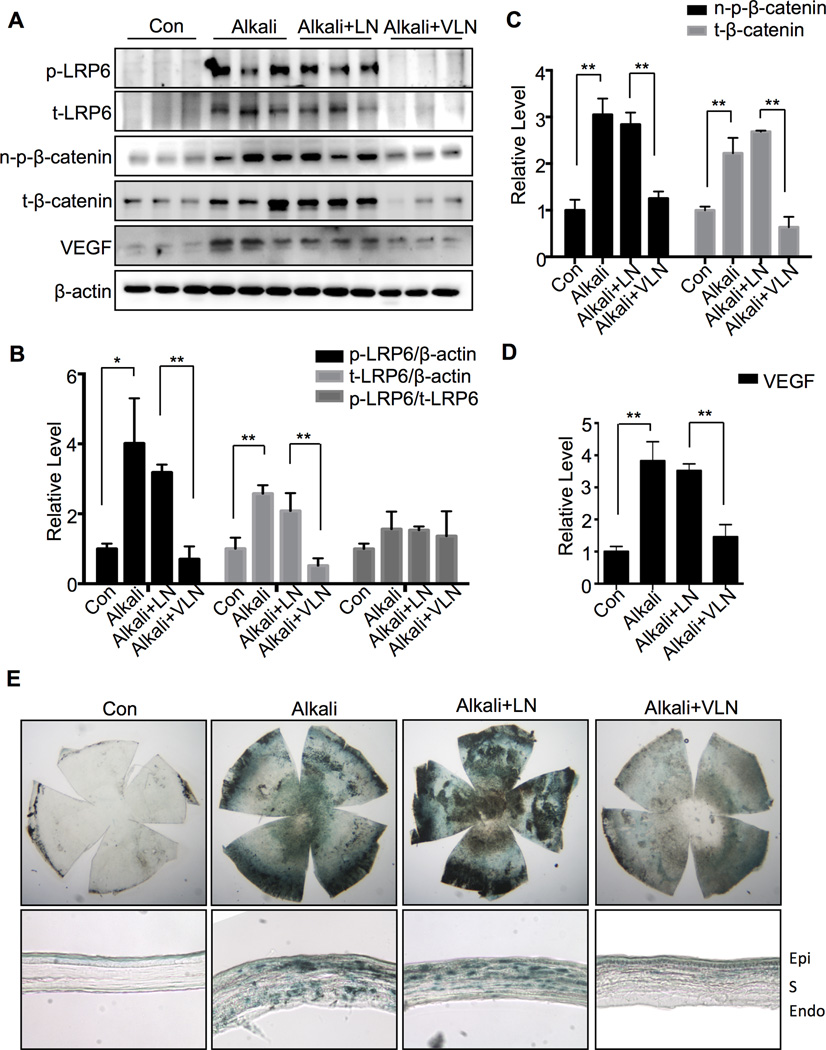

As shown in Figure 6, levels of p-LRP6, t-LRP6, n-p-β-catenin, t-β-catenin and VEGF in the cornea were significantly elevated in the untreated and LN-NP-treated corneas with alkali burn, compared to control without alkali burn. VLN-NP (20 µl, 10 mg/ml) treatment dramatically suppressed the increases of p-LRP6, t-LRP6, n-p-β-catenin, t-β-catenin and VEGF (Fig. 6A–D).

Fig. 6. VLN-NP inhibits Wnt signaling in neovascularized cornea after alkali burn.

A: Corneal levels of proteins were measured by Western blot analysis at day 7 following the alkali burn. Each lane represents an individual rat. B–D: Semi-quantification of p-LRP6 and t-LRP6 (B), n-p-β-catenin and t-β-catenin (C), and VEGF (D) levels by densitometry and normalized by β-actin levels. **p<0.01, *p<0.05, n=3. E: X-gal staining of the whole corneas and corneal sections. Corneas from BAT-gal mice were isolated at Day 7 after the alkali burn and fixed. Corneal flat-mount and frozen sections were stained with X-gal to evaluate the expression of β-galactosidase reporter (blue). Epi: epithelium; S: stroma; Endo: endothelium.

The same procedure of alkali burn was performed in BAT-gal transgenic mice, and flat-mounted corneas and corneal sections showed more intense blue color, indicative of active Wnt signaling, after X-gal staining in the alkali burn group, without treatment or with LN treatment compared with no burn group. Moreover, significantly less intense blue color was observed in the VLN-NP treated corneas with alkali burn (Fig. 6E), indicating that VLN-NP inhibited Wnt signaling activity in the cornea with alkali burn-induced NV.

Discussion

Ocular neovascular diseases constitute the most common causes of severe and irreversible vision loss in developed countries26. The canonical Wnt signaling pathway plays a vital part in ocular development and diseases27, as well as in ischemia-induced retinal NV and laser-induced CNV23, 28, 29. Our group reported that VLDLR deficiency results in over-activation of the Wnt signaling pathway and retinal NV13, suggesting a potential role of VLDLR as an endogenous inhibitor of Wnt signaling and ocular NV. Recently, our group revealed that the extracellular domain of VLDLR is essential for its inhibition of the Wnt pathway in vitro16. However, the potential usage of VLDLR in the treatment of pathological ocular NV diseases has not been established. The present study provided the first in vivo evidence that the soluble extracellular domain of VLDLR is responsible for its inhibition of ocular NV through down-regulating Wnt signaling. Additionally, our data also show that nanoparticle-mediated delivery of VLDLR extracellular peptide is an effective approach to treat ocular diseases in mouse models.

Ocular NV, depending on its location and causation, can have distinct pathogenic mechanisms. However, angiogenic factors such as VEGF are commonly involved in almost all types of the ocular NV. Wnt signaling, which is an upstream signaling pathway regulating VEGF, has been shown to play a crucial part in retinal NV formation, and inhibitors of Wnt signaling have displayed therapeutic potential for retinal NV diseases23, 28, 30. This study demonstrates that Wnt signaling is up-regulated in all three NV models (Fig. 4, 6), which are consistent with previous studies in Vldlr−/− mice13, 31 and OIR model29, 32. Further, the present study is the first to establish the pathogenic role of Wnt signaling in corneal NV. Although β-catenin was reported to be up-regulated in the neovascularized cornea after alkali burn30, it was not clear if the Wnt pathway was activated, since β-catenin has multiple functions in addition to participating in Wnt signaling cascade, such as modulating cellular adhesion and cytoskeleton33. The present study evaluated the Wnt pathway activity at multiple levels including phosphorylation of a Wnt co-receptor, LRP6; up-regulation of VEGF, a direct target gene of β-catenin; and transcriptional activity of β-catenin in the corneas (Fig. 6). All of these assays showed that Wnt signaling was activated in the neovascularized cornea after alkali burn, thus providing further evidence for a key pathogenic role of Wnt signaling in ocular NV. In addition, we also measured the expression of transcription factor TCF in HRMEC. The TCF mRNA was not altered with the treatment of WCM or VLN-NP (Suppl. Fig. III). While the functional suppression of TCF activity by VLN is supported by our results from TOPFLASH assay (Fig. 2H), showing that VLN suppressed Wnt3a-induced TOPFLASH activity, indicative of TCF transcriptional activity. Therefore, the transcriptional function of TCF, rather than its expression level, is relevant to Wnt signaling activity and VLN suppression.

LRP6 and VLDLR both belong to the LDLR family and share significant amino acid sequence identity in their extracellular domains34. It has been established that the extracellular domain of LRP6 is the essential binding domain for Wnt ligands and some Wnt signaling inhibitors such as DKK135, 36, and also required for homodimerization of LRP6 to initialize Wnt signaling37. As the extracellular domain of VLDLR can be shed into the extracellular space15, we hypothesized that the soluble extracellular domain of VLDLR may function as a soluble cytokine and confer some physiological or pathological functions distinct from its membrane form. Based on the hypothesis, our group dived into the structural basis for the inhibitory effect of VLDLR on Wnt signaling, and found that VLN is essential for the inhibition of Wnt signaling16. Here, we generated a nanoparticle-encapsulated the extracellular domain of VLDLR, termed as VLN-NP. Our results show that VLN is sufficient to inhibit Wnt3a-induced HRMEC growth, migration and tube formation (Fig. 1B–G). Moreover, it was reported that knockdown of VLDLR by siRNA enhanced endothelial cell viability, migration and tube formation22. Our data show that VLN-NP inhibits HRMEC growth induced by the VLDLR siRNA (Fig. 1H), suggesting that the ectodomain of VLDLR is sufficient to constitute the Wnt inhibiting function of VLDLR in regulation of Wnt signaling. Three animal models all demonstrated VLN-NP ameliorate ocular NV and suppress Wnt signaling as shown at the receptor level (LRP6), transcription factor level (β-catenin) and target gene level (VEGF) in vivo. Our data showed that a specific blocker of LRP6 attenuated the VEGF expression induced by WCM, similar to the effect of VLN-NP (Fig. 2E). Further, VLN-NP did not decrease VEGF expression induced by a constitutively active mutant of β-catenin (Ad-S37A), which activates Wnt target genes down-stream of LRP6 in HRMEC (Fig. 2F, G). These results support that the inhibition of VEGF by VLN is achieved through suppressing Wnt signaling at the co-receptor LRP6 level. Our recent publication demonstrated that VLDLR inhibits Wnt signaling through the formation of a heterodimer with LRP616. This heterodimerization blocks the binding of Wnt ligand and the co-receptor LRP6, which is an essential step in the activation of Wnt signaling. The heterodimerization also reduces LRP6 levels on the cell surface by accelerating its internalization and turnover of LRP616, which explains the reduction of total LRP6 in VLN-NP treated group and non-significant changes of the p-LRP6/t-LRP6 ratios in this study. Here, our data showed that the mRNA levels of LRP6 were not changed in vascularized corneas in vivo or with Wnt3a stimulation in vitro, nor by VLN-NP treatment (Suppl. Fig. II), indicating that VLN may modulate LRP6 on post-translational level. Taken together, these data indicate that soluble VLN functions as an inhibitor of ocular NV through suppressing Wnt signaling pathway.

The delivery of macromolecules such as DNA and protein to ocular tissues, especially the posterior segment, is challenging due to the existence of structural barriers. Therefore, the development of nano-sized carriers may represent a promising approach in ocular drug delivery38. Although the nanoparticles formulated using PLGA polymers have not been widely used in clinic, they are being extensively used in research because of their sustained release characteristics, biodegradability, biocompatibility and ability to protect DNA from degradation39. Our data showed that VLN-NP mediated substantial and sustained VLN expression in cultured cells and in the retina for at least 4 weeks after a single injection, confirming effective internalization of the nanoparticles, and that the cargo protein VLN is expressed and released into the extracellular space.

In conclusion, this study suggests that the Wnt signaling pathway plays an important pathogenic role in corneal and retinal NV; nanoparticle-mediated delivery of soluble VLN has therapeutic potential for ocular NV diseases, and likely through the inhibition of Wnt signaling. However, there are still some unsolved questions that warrant further studies in the future. Previous study showed that Vldlr−/− retinas and down-regulation of VLDLR by siRNA resulted in up-regulation of LRP6 expression at both the protein and mRNA levels13, while our data indicate that the Wnt signaling pathway and VLN does not affect LRP6 mRNA level. It is possible that VLDLR regulates LRP6 expression at different levels, depending on cell types, duration of the treatment and types of the treatments. The present study focuses on the mechanism that VLN regulates LRP6 at the post-translational level, and further study needs to be performed to demonstrate the molecular mechanism by which VLDLR modulates Wnt signaling through down-regulating LRP6 at different levels. In addition, although nanoparticle significantly reduces the frequency of injection, there may be still associated risks due to the characteristics of intravitreous injection. Better drug administration remains to be explored. Nevertheless, VLN-NP represents a promising strategy to treat ocular NV, providing an encouraging perspective for clinic usage.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

The present study is the first to establish the causative role of activation of Wnt signaling in corneal neovascularization, as well as in retinal NV in Vldlr−/− and OIR models. Extracellular domain of VLDLR is essential to inhibit pathological Wnt signaling and suppress aberrant ocular NV, providing a new endogenous inhibitor of Wnt signaling and a potential drug target. In addition, the this study also shows nanoparticle is an efficient delivery way for intraocular administration, which may offer a promising approach in ocular drug delivery.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Xi He at Harvard University for providing the plasmid expressing the LDLR extracellular domain for this study.

This study is supported by grants from National Institutes of Health grants EY012231, EY018659, EY019309, and GM104934, a grant from IRRF, a grant from Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science & Technology (OCAST) HR13-076 and a grant from Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Abbreviations

- VLDLR

very low-density lipoprotein receptor

- NV

neovascularization

- VLN

VLDLR extracellular domain

- PLGA

poly (lactide-co-glycolide acid)

- VLN-NP

VLN nanoparticles

- LDLR

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- LN

LDLR extracellular domain

- LN-NP

LN nanoparticles

- EC

endothelial cell

- OIR

oxygen-induced retinopathy

- LRP5/6

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6

- n-p-β-catenin

Non-phosphorylated-β-catenin

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- HRMEC

human retinal microvascular endothelial cells

- WCM

Wnt3a conditioned medium

- LCM

L cell conditioned medium

- ERG

electroretinography

- IRN

intra-retinal neovascular

- WT

wild-type

- DKK1

Dickkopf1

Footnotes

Author contributions: Z. Wang, research design, data collection, manuscript writing; K. Lee, data collection; T. Puneet, data collection; R. Cheng, data collection; L. Ding, data collection; X. Xu, manuscript writing; J Chen, manuscript writing; U.B. Kompella, research design, manuscript writing; J-x. Ma, research design, manuscript writing

Competing interests: None.

Data and materials availability: N/A

References

- 1.Rathmann W, Giani G. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes care. 2004;27:2568–2569. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2568. author reply 2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gehrs KM, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hageman GS. Age-related macular degeneration--emerging pathogenetic and therapeutic concepts. Annals of medicine. 2006;38:450–471. doi: 10.1080/07853890600946724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunker DJ, George RJ, Kumar RJ, Maitz P. Alkali-related ocular burns: A case series and review. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2013 doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31829b0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honda M, Asai T, Oku N, Araki Y, Tanaka M, Ebihara N. Liposomes and nanotechnology in drug development: Focus on ocular targets. International journal of nanomedicine. 2013;8:495–503. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S30725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim LA, D'Amore PA. A brief history of anti-vegf for the treatment of ocular angiogenesis. The American journal of pathology. 2012;181:376–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2008;8:387–398. doi: 10.1038/nrc2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reis M, Liebner S. Wnt signaling in the vasculature. Experimental cell research. 2013;319:1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dejana E. The role of wnt signaling in physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Circulation research. 2010;107:943–952. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinnunen K, Yla-Herttuala S. Vascular endothelial growth factors in retinal and choroidal neovascular diseases. Annals of medicine. 2012;44:1–17. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.532150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wittmaack FM, Gafvels ME, Bronner M, Matsuo H, McCrae KR, Tomaszewski JE, Robinson SL, Strickland DK, Strauss JF., 3rd Localization and regulation of the human very low density lipoprotein/apolipoprotein-e receptor: Trophoblast expression predicts a role for the receptor in placental lipid transport. Endocrinology. 1995;136:340–348. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.1.7828550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heckenlively JR, Hawes NL, Friedlander M, Nusinowitz S, Hurd R, Davisson M, Chang B. Mouse model of subretinal neovascularization with choroidal anastomosis. Retina. 2003;23:518–522. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200308000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C, Huang Z, Kingsley R, Zhou X, Li F, Parke DW, 2nd, Cao W. Biochemical alterations in the retinas of very low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice: An animal model of retinal angiomatous proliferation. Archives of ophthalmology. 2007;125:795–803. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.6.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Hu Y, Lu K, Flannery JG, Ma JX. Very low density lipoprotein receptor, a negative regulator of the wnt signaling pathway and choroidal neovascularization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34420–34428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oka K, Tzung KW, Sullivan M, Lindsay E, Baldini A, Chan L. Human very-low-density lipoprotein receptor complementary DNA and deduced amino acid sequence and localization of its gene (vldlr) to chromosome band 9p24 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genomics. 1994;20:298–300. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magrane J, Casaroli-Marano RP, Reina M, Gafvels M, Vilaro S. The role of o-linked sugars in determining the very low density lipoprotein receptor stability or release from the cell. FEBS Lett. 1999;451:56–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee K, Shin Y, Cheng R, Park K, Hu Y, McBride J, He X, Takahashi Y, Ma JX. Receptor heterodimerization as a novel mechanism for the regulation of wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:4857–4869. doi: 10.1242/jcs.149302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishibashi S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Gerard RD, Hammer RE, Herz J. Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1993;92:883–893. doi: 10.1172/JCI116663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudolf M, Winkler B, Aherrahou Z, Doehring LC, Kaczmarek P, Schmidt-Erfurth U. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor associated with accumulation of lipids in bruch's membrane of ldl receptor knockout mice. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2005;89:1627–1630. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.071183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadat Tabatabaei Mirakabad F, Nejati-Koshki K, Akbarzadeh A, Yamchi MR, Milani M, Zarghami N, Zeighamian V, Rahimzadeh A, Alimohammadi S, Hanifehpour Y, Joo SW. Plga-based nanoparticles as cancer drug delivery systems. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2014;15:517–535. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.2.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farokhzad OC, Cheng J, Teply BA, Sherifi I, Jon S, Kantoff PW, Richie JP, Langer R. Targeted nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for cancer chemotherapy in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:6315–6320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601755103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park K, Chen Y, Hu Y, Mayo AS, Kompella UB, Longeras R, Ma JX. Nanoparticle-mediated expression of an angiogenic inhibitor ameliorates ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization and diabetes-induced retinal vascular leakage. Diabetes. 2009;58:1902–1913. doi: 10.2337/db08-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang A, Hu W, Meng H, Gao H, Qiao X. Loss of vldl receptor activates retinal vascular endothelial cells and promotes angiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:844–850. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee K, Hu Y, Ding L, Chen Y, Takahashi Y, Mott R, Ma JX. Therapeutic potential of a monoclonal antibody blocking the wnt pathway in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2012;61:2948–2957. doi: 10.2337/db11-0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, Wong LL, Karakoti AS, Seal S, McGinnis JF. Nanoceria inhibit the development and promote the regression of pathologic retinal neovascularization in the vldlr knockout mouse. PloS one. 2011;6:e16733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Lin Z, Zhou T, Zong R, He H, Liu Z, Ma JX, Liu Z, Zhou Y. Anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of serpina3k on corneal injury. PloS one. 2011;6:e16712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campochiaro PA. Ocular neovascularization. Journal of molecular medicine. 2013;91:311–321. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-0993-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Iongh RU, Abud HE, Hime GR. Wnt/frizzled signaling in eye development and disease. Front Biosci. 2006;11:2442–2464. doi: 10.2741/1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu Y, Chen Y, Lin M, Lee K, Mott RA, Ma JX. Pathogenic role of the wnt signaling pathway activation in laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2013;54:141–154. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Stahl A, Krah NM, et al. Wnt signaling mediates pathological vascular growth in proliferative retinopathy. Circulation. 2011;124:1871–1881. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.040337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang L, Zhang MC, Zhang Y, He Z, Zhang L, Xiao SY. Beta-catenin expression in rat neovascularized cornea after alkali burn. International journal of ophthalmology. 2010;3:304–307. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2010.04.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dorrell MI, Aguilar E, Jacobson R, Yanes O, Gariano R, Heckenlively J, Banin E, Ramirez GA, Gasmi M, Bird A, Siuzdak G, Friedlander M. Antioxidant or neurotrophic factor treatment preserves function in a mouse model of neovascularization-associated oxidative stress. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:611–623. doi: 10.1172/JCI35977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, Zhang B, McBride JD, Zhou K, Lee K, Zhou Y, Liu Z, Ma JX. Anti-angiogenic and anti-neuroinflammatory effects of kallistatin through interactions with the canonical wnt pathway. Diabetes. 2013 doi: 10.2337/db12-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fagotto F. Looking beyond the wnt pathway for the deep nature of beta-catenin. EMBO reports. 2013;14:422–433. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krieger M, Herz J. Structures and functions of multiligand lipoprotein receptors: Macrophage scavenger receptors and ldl receptor-related protein (lrp) Annual review of biochemistry. 1994;63:601–637. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mao B, Wu W, Li Y, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C. Ldl-receptor-related protein 6 is a receptor for dickkopf proteins. Nature. 2001;411:321–325. doi: 10.1038/35077108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng Z, Biechele T, Wei Z, Morrone S, Moon RT, Wang L, Xu W. Crystal structures of the extracellular domain of lrp6 and its complex with dkk1. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2011;18:1204–1210. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu S, Liu Y, Yang X, et al. The brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nature communications. 2014;5:3930. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu S, Jones L, Gu FX. Nanomaterials for ocular drug delivery. Macromolecular bioscience. 2012;12:608–620. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201100419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panyam J, Zhou WZ, Prabha S, Sahoo SK, Labhasetwar V. Rapid endo-lysosomal escape of poly(dl-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles: Implications for drug and gene delivery. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2002;16:1217–1226. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0088com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.