Abstract

Carbon monoxide (CO) production from heme catabolism is increased with hemolysis. A portable end-tidal CO (ETCO) monitor was used to analyze breath samples in 16 children with sickle cell anemia (SCA, 5-14 years). Median (range) ETCO for SCA was 4.35 ppm (1.8-9.7) versus 0.80 ppm (0.2-2.3) for controls (P<0.001). ETCOc >2.1 ppm provided sensitivity and specificity of 93.8% (69.8-99.8%) for detecting SCA. ETCO correlated with reticulocytosis (P=0.015) and bilirubin (P=0.009), and was 32% lower in children receiving hydroxyurea (P=0.09). Point-of-care ETCO analysis may prove useful for non-invasive monitoring of hemolysis and as a screening test for SCA.

Keywords: Sickle cell anemia, Hemoglobinopathies, Red blood cell disorders

Introduction

Carbon Monoxide (CO) produced during the cleavage of porphyrin ring of heme is mostly derived from hemoglobin breakdown [1]. The catabolism of heme by heme oxygenase (HO) creates equimolar amounts of iron, carbon monoxide and biliverdin [2]. Thus, quantifying CO in exhaled breath serves as an indicator of hemolysis [3]. Alveolar breath CO closely approximates carboxyhemoglobin concentration in adults [4]. Since children may not cooperate to provide a forced breath sample, end-tidal CO (ETCO) monitoring has been evaluated as an alternative [5,6]. We describe the utility of point-of-care measurement of ETCO to detect hemolysis in sickle cell anemia (SCA).

Results

Sixteen children with SCA (HbSS, mean age 9.7 year, range 5-14 years) who were not transfused in previous 3 months were enrolled, along with age and gender matched controls. Subjects did not have history of cigarette smoking or exposure to second hand smoke which are associated with elevated carboxyhemoglobin concentration [4]. Children with recent infection or symptomatic asthma were excluded since inflammation raises ETCO through induction of HO in respiratory epithelial cells [7,8]. One subject in control group (ETCO 3.2 ppm) was excluded due to asthma and oxcarbazepine therapy [9]. Informed consent was obtained per institutional review board guidelines. ETCO corrected for ambient CO (ETCOc) was measured during normal breathing with the CoSense® ETCO monitor (Capnia, Redwood City, CA) in duplicate using a nasal cannula, with a third sample obtained if the difference was >15%. The mean intra-subject coefficient of variation in HbSS was 8.0%. Each measurement took typically <1 minute for breath acquisition and a further 2 minutes to display ETCOc result. The highest ETCOc value for the subject was used for analysis. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01848691).

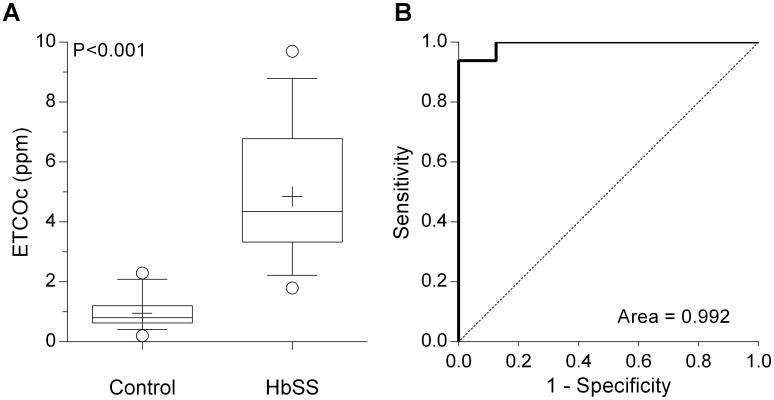

The median (range) ETCOc for HbSS was 4.35 ppm (1.8-9.7 ppm) versus 0.80 ppm (0.2-2.3 ppm) for controls (P<0.001, Mann-Whitney test, Figure 1A). Using the lowest (instead of highest) ETCOc value for each subject dropped the median ETCOc in HbSS to 4.1 ppm (1.8-9.2 ppm), but did not alter significance of the comparison (P<0.001). In the control group, ETCOc was ≤1.2 ppm in 14/16 (88%), which appeared to be the upper limit for healthy children. In the HbSS group, 15/16 subjects had ETCOc value ≥2.4 ppm, so the expected ETCOc in HbSS is likely >2.0 ppm. Receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curve confirmed the ability of ETCOc to distinguish between HbSS and controls (Figure 1B) with area under the curve (AUC) 0.99 ± 0.01. A threshold ETCOc value of >2.1 ppm provided both sensitivity and specificity equal to 93.8% (95% CI 69.8-99.8%). Inclusion of the control subject who was found ineligible in the ROC analysis changed sensitivity and specificity to 94.1% (71.3-99.9%) for ETCOc >2.3 ppm.

Figure 1.

(A) End-tidal carbon monoxide concentration in children with sickle cell anemia (SCA) and healthy age-matched controls (n=16 for both groups). Whiskers extend from 10-90th percentile (+: mean). (B) Receiver-operator characteristic curve (solid line) for ETCOc in children with or without a diagnosis of SCA. A threshold ETCOc value of 2.1 ppm provided a sensitivity and specificity of 93.8% to differentiate between the two groups. (Dotted line: line of identity).

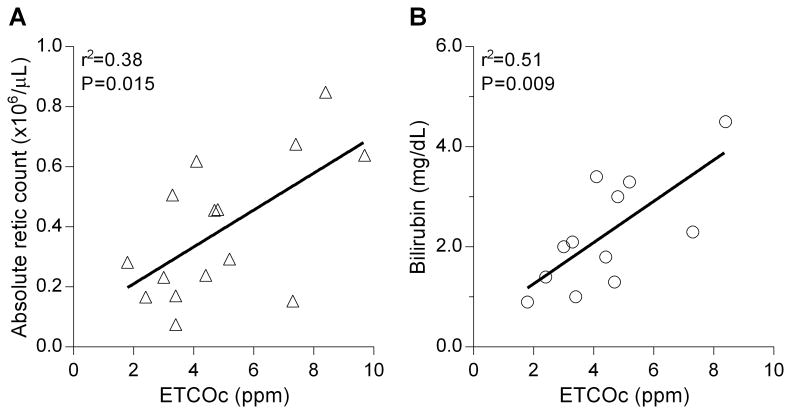

ETCOc was closely associated with hemolysis as demonstrated by a significant positive correlation with absolute reticulocyte count (r2=0.38, P=0.015) and total serum bilirubin (r2=0.51, P=0.009, Figures 2A and 2B). No correlation was observed with hemoglobin level, although children with severe anemia (hemoglobin <8 g/dL) had higher mean ETCOc (5.43 ppm vs. 4.40 ppm, P=0.38). There was a lack of association between ETCOc and LDH (r2=0.12) or AST (r2=0.04). The mean ETCOc was lower in children receiving hydroxyurea therapy (n=9, 4.01 ± 1.62 ppm) compared with those without hydroxyurea (n=7, 5.93±2.57, P=0.09, Student's t-test). As previously observed [6], there was a trend towards higher ETCOc level with age for both the HbSS (r2=0.21, P=0.08) and control (r2=0.24, P=0.05) groups.

Figure 2.

Association of end-tidal carbon monoxide concentration (ETCOc) with absolute reticulocyte count (Figure 2A, n=15), and serum bilirubin concentration (Figure 2B, n=12).

Discussion

The results of this pilot study show that ETCOc is a non-invasive point-of-care (POC) indicator of hemolysis in sickle cell anemia. The range of CO excretion between controls and HbSS was sufficiently different to discriminate between the two groups with confidence. The data demonstrated a quantitative relationship between severity of hemolysis and ETCOc.

The range of ETCOc levels in HbSS observed with CoSense monitor is similar to previous reports using an earlier device (CO-Stat™, Natus Medical, San Carlos, CA, manufacturing discontinued) [5,6]. The 5-fold elevation of ETCOc in HbSS supports its potential utility as a non-invasive screening test [10], and we found a threshold ETCOc >2.1 ppm will detect most children with HbSS. A previous study from our institution (with Co-Stat™ monitor) reported ETCOc >3.0 ppm distinguished patients from controls with 86% sensitivity and 97% specificity [5]. This variation is likely from difference in technology and heterogeneous subject population (sickle cell disease and thalassemia) in the previous study. The CoSense monitor used in our study has the advantages of improved end-tidal breath capture, portability and pre-calibration of the CO sensor (obviating the need for on-site calibration). Thus, greater ease of use in the field without the need for extensive operator training is anticipated.

Prior studies in chronically transfused patients showed that ETCOc levels are influenced by hemoglobin and time since transfusion [5,6]. The current study is the first to observe a strong association between ETCOc and hemolysis in HbSS at steady state. Thus, ETCOc is similar to other gauges of CO excretion, such as endogenous CO production rate and carboxyhemoglobin concentration [3,11], but easier to measure at the POC. We found the strongest correlation was between ETCOc and total serum bilirubin with a coefficient of determination (r2) of 0.52, implying that half of the variance in ETCOc was explained by bilirubin level. Further, it was observed that children with HbSS receiving hydroxyurea (which is associated with decrease in hemolysis [12]) had 32% lower ETCOc levels. The lack of association between ETCOc and either LDH or AST may reflect the primary association of these two markers with intravascular hemolysis [13], while serum bilirubin is a composite measure of catabolism of all heme (derived from intra- and extravascular hemolysis) in the body.

A limitation of our data is the small number of subjects and that it was conducted under controlled circumstances in the clinic. ETCOc levels are affected by genotype (hemolysis is less severe in HbSC or S beta+ thalassemia) and fetal hemoglobin [14,15]. ETCOc has not been measured in infants to assess the effect of gradual decline in fetal hemoglobin after birth on hemolysis. However, the validity of measuring ETCOc has been demonstrated in newborns with immune hemolysis [16]. Further studies should evaluate the impact of genotype and fetal hemoglobin on ETCOc levels. Respiratory infection, asthma, and to a lesser extent, non-respiratory infections raise ETCO unrelated to hemolysis [1,7,8], as does environmental CO inhalation [17]. In all cases with abnormal result, an inquiry into the presence of infectious and environmental causes of elevated ETCOc should be made.

In conclusion, this study reports the use of a new portable method for measuring ETCOc. POC testing provides instantaneous results of ETCOc at the bedside, which could be applied to monitor hemolysis during acute pain or febrile episodes and predicting the need for transfusion or risk of acute chest syndrome. ETCOc can also be useful to monitor the response to hydroxyurea therapy. Since ETCOc levels are distinct between HbSS and controls and the device is suitable for field usage, it could be developed as a tool for POC screening test for SCA in children living in resource poor countries [18].

Acknowledgments

Capnia Inc, Redwood City, CA, provided financial support for this study and provided the CoSense End Tidal Carbon Monoxide monitor and the nasal cannulas that were used in this study.

This project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- SCA

Sickle cell anemia (HbSS)

- POC

Point-of-care

- ETCOc

End tidal carbon monoxide corrected for ambient CO

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Owens EO. Endogenous carbon monoxide production in disease. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gozzelino R, Jeney V, Soares MP. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:323–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coburn RF, Williams WJ, Kahn SB. Endogenous carbon monoxide production in patients with hemolytic anemia. J Clin Invest. 1966;45:460–468. doi: 10.1172/JCI105360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald NJ, Idle M, Boreham J, Bailey A. Carbon monoxide in breath in relation to smoking and carboxyhaemoglobin levels. Thorax. 1981;36:366–369. doi: 10.1136/thx.36.5.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James EB, Vreman HJ, Wong RJ, Stevenson DK, Vichinsky E, Schumacher L, Hall JY, Simon J, Golden DW, Harmatz P. Elevated exhaled carbon monoxide concentration in hemoglobinopathies and its relation to red blood cell transfusion therapy. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;27:112–121. doi: 10.3109/08880010903536227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sylvester KP, Patey RA, Rafferty GF, Rees D, Thein SL, Greenough A. Exhaled carbon monoxide levels in children with sickle cell disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164:162–165. doi: 10.1007/s00431-004-1605-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaya M, Sekizawa K, Ishizuka S, Monma M, Mizuta K, Sasaki H. Increased carbon monoxide in exhaled air of subjects with upper respiratory tract infections. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:311–314. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9711066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Yao X, Yu R, Bai J, Sun Y, Huang M, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ. Exhaled carbon monoxide in asthmatics: A meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2010;11:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhry MM, Abrar M, Mutahir K, Mendoza C. Oxcarbazepine-induced hemolytic anemia in a geriatric patient. Am J Ther. 2008;15:187–189. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31815afb6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odame I. Developing a global agenda for sickle cell disease: Report of an international symposium and workshop in cotonou, republic of benin. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:S571–S575. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sears DA, Udden MM, Thomas LJ. Carboxyhemoglobin levels in patients with sickle-cell anemia: Relationship to hemolytic and vasoocclusive severity. Am J Med Sci. 2001;322:345–348. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballas S, Marcolina M, Dover G, Barton F, the Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea Sickle Cell A Erythropoietic activity in patients with sickle cell anaemia before and after treatment with hydroxyurea. Br J Haematol. 1999;105:491–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato GJ, McGowan V, Machado RF, Little JA, Taylor J, Morris CR, Nichols JS, Wang X, Poljakovic M, Morris SM, Gladwin MT. Lactate dehydrogenase as a biomarker of hemolysis-associated nitric oxide resistance, priapism, leg ulceration, pulmonary hypertension, and death in patients with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2006;107:2279–2285. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lal A, Vichinsky E, Sickle cell disease . In: Postgraduate haematology. 6th. Hoffbrand AV, editor. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester, West Sussex, UK: 2011. pp. 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akinsheye I, Alsultan A, Solovieff N, Ngo D, Baldwin CT, Sebastiani P, Chui DHK, Steinberg MH. Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2011;118:19–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-325258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du L, Zou P, Chen L, Bhutani VK. Exhaled end-tidal carbon monoxide testing for hemolysis in neonates with significant hyperbilirubinemia and positive direct anti-globulin test (abstr.). PAS/ASPR Joint Meeting, 2014; Vancouver, BC. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ballard-Tremeer G, Jawurek HH. Comparison of five rural, wood-burning cooking devices: Efficiencies and emissions. Biomass Bioenergy. 1996;11:419–430. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modell B, Darlison M. Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders and derived service indicators. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:480–487. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.036673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]