Abstract

Fear memories allow organisms to avoid danger, thereby increasing their chances of survival. Fear memories can be retrieved long after learning1,2, but little is known about how retrieval circuits change with time3,4. Here we show that the dorsal midline thalamus of rats is required for retrieval of auditory conditioned fear at late timepoints (24 h, 7 d, 28 d), but not early timepoints (0.5 h, 6 h) after learning. Consistent with this, the paraventricular subregion of the dorsal midline thalamus (PVT) showed increased cFos expression only at late timepoints, indicating that PVT is gradually recruited for fear retrieval. Accordingly, the conditioned tone responses of PVT neurons increased with time following training. The prelimbic (PL) prefrontal cortex, which is necessary for fear retrieval5–7, sends dense projections to PVT8. Retrieval at late timepoints activated PL neurons projecting to PVT, and optogenetic silencing of these projections impaired retrieval at late, but not early times. In contrast, silencing of PL inputs to the basolateral amygdala (BLA) impaired retrieval at early, but not late times, indicating a time-dependent shift in retrieval circuits. Retrieval at late timepoints also activated PVT neurons projecting to the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), and silencing these projections at late, but not early, times induced a persistent attenuation of fear. Thus, PVT may serve as a critical thalamic node recruited into cortico-amygalar networks for retrieval and maintenance of long-term fear memories.

Keywords: prefrontal cortex, midline thalamus, paraventricular, amygdala, optogenetics, unit-recording, fear conditioning

The association between a conditioned stimulus (e.g. a tone) and an aversive event (e.g. an electrical shock) can be retrieved throughout the lifetime of an animal9–11. This tone-shock association is stored in BLA and CeA12–15, but the circuits necessary for retrieval of this memory at various times after learning are not well understood. BLA receives inputs from PL16,17, a region necessary for fear retrieval5–7. PL also projects densely to the dorsal midline thalamus (dMT)8, which in turn projects to CeA18. Thus, dMT could coordinate fear responses with adaptive responses such as stress, sleep, and foraging through its connections with the hypothalamus or nucleus accumbens8,19. We previously observed that dMT is necessary for fear retrieval 24 h after conditioning, but not earlier20. Here, to directly test the hypothesis that retrieval circuits change with time, we used pharmacological, immunocytochemical, unit-recording, and optogenetic techniques.

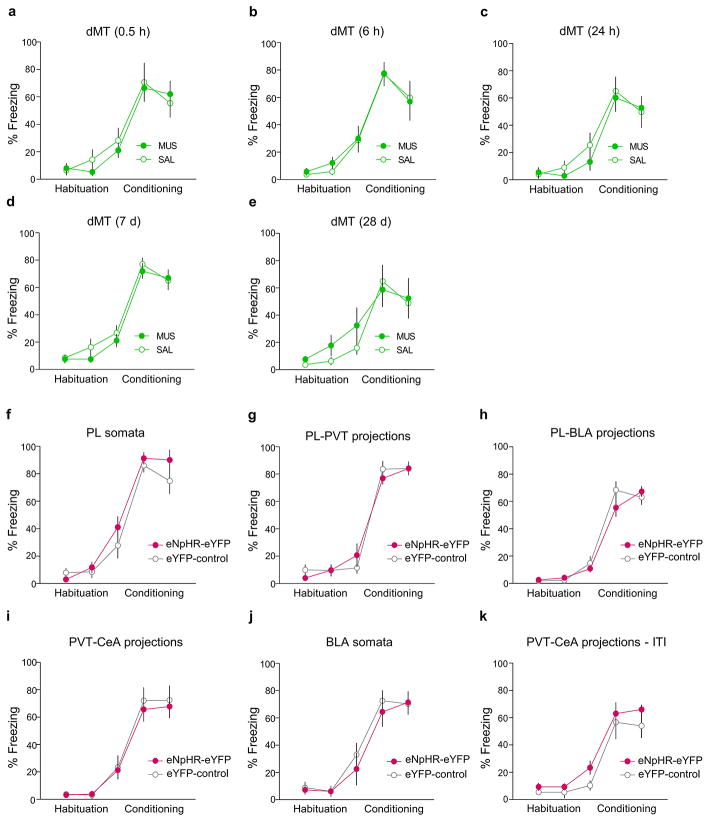

We found that inactivating dMT with GABA-A receptor agonist muscimol shortly after conditioning (0.5 h or 6 h) had no effect on fear retrieval, but inactivating dMT at later timepoints (24 h, 7 d and 28 d) impaired retrieval (Fig. 1a–c; conditioning levels shown in Extended Data Fig. 1a–e). The following day, in the absence of drug, retrieval remained impaired in the 7 d and 28 d groups (Fig. 1d), suggesting that dMT activity may be necessary for the maintenance of fear memory. In support of this, retrieval was still impaired one week following the initial retrieval test (day 14, see Extended Data Fig. 2a). Inactivation of dMT without retrieval had no effect (Extended Data Fig. 2b), suggesting a possible role of dMT in memory reconsolidation. Although intra-dMT infusion of drugs that block reconsolidation had no effect (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d), dMT activity could be facilitating memory reconsolidation in downstream structures (e.g. amygdala). Thus, with the passage of time, dMT activity becomes increasingly necessary first for retrieval and later for maintenance of fear memories.

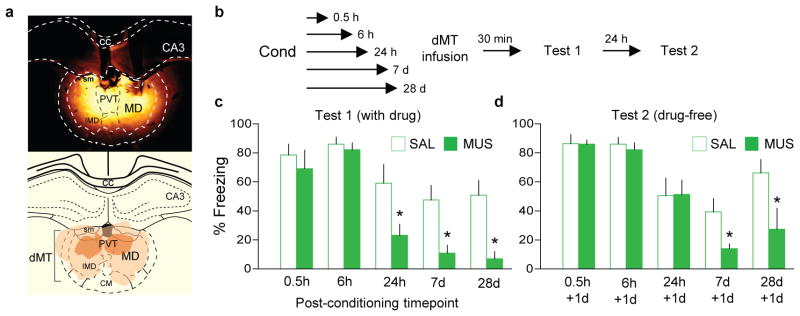

Figure 1. The dorsal midline thalamus (dMT) is necessary for retrieval of fear at late, but not early, timepoints after conditioning.

(a, upper) Representative micrograph showing the site of fluorescent muscimol (MUS) injection into dMT. (a, lower) Orange areas represent the minimum (dark) and the maximum (light) spread of muscimol into dMT. (b) Experimental design. (c, left) Freezing to conditioned tones after infusion of saline (SAL, white bars) or MUS (green bars) at different post-conditioning timepoints. MUS impaired freezing (F(4,73)= 3.31, P= 0.01) at 24 h (P= 0.002, n= 8 per group), 7 d (P= 0.002, n= 14 per group) and 28 d (P< 0.001, n= 10 for SAL group, n= 6 for MUS group), but not at 0.5 h or 6 h (P’s > 0.99, n= 6 per group). (c, right) The following day, persistent attenuation of freezing (F(2,54)= 4.78, P= 0.011) was observed at 7 d (P= 0.013) and 28 d (P= 0.04), but not at 24 h (P= 0.35). Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. Data are shown as mean ± SEM in blocks of two trials; *P < 0.05.

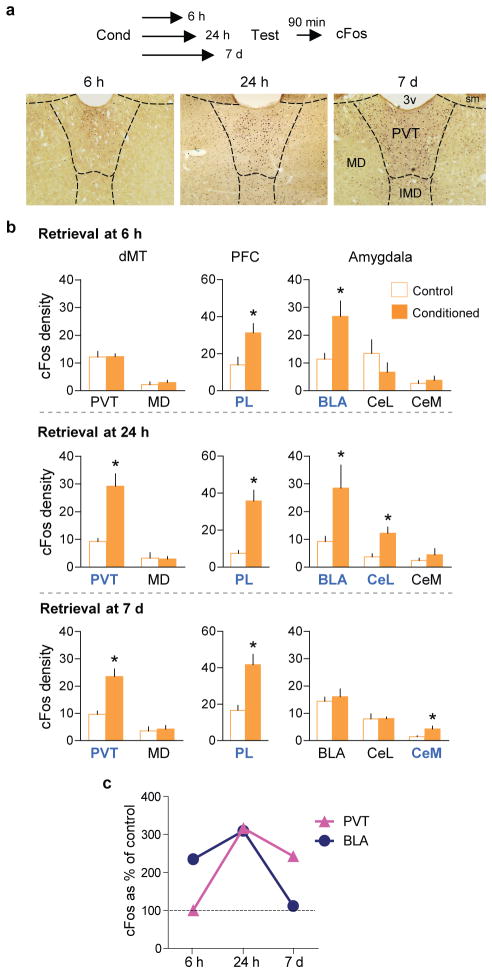

Next, we used the neural activity marker cFos to determine when dMT is activated by conditioning. Following training, exposure to conditioned tones induced robust freezing at 6 h, 24 h and 7 d timepoints (Extended Data Fig. 3a–c), but triggered different patterns of neuronal activation (Fig. 2a,b). The mediodorsal subdivision of dMT (MD) showed no conditioned activation at any timepoint, whereas PL showed activation at all three timepoints. This suggests that PL is necessary for retrieval at both early and late timepoints, which we confirmed with muscimol (Extended Data Fig. 3d–f). Retrieval at 6 h activated PL and BLA, but not PVT neurons, whereas retrieval at 7 d activated PL and PVT, but not BLA neurons. Retrieval at 7 d also activated the medial portion of the central amygdala (CeM), suggesting that retrieval at 7 d may involve PL-PVT and PVT-CeA pathways. At 24 h, however, both targets of PL (BLA and PVT) were activated (Fig. 2b,c), suggesting a gradual shift in retrieval circuits from PL-BLA to PL-PVT.

Figure 2. cFos expression induced by fear retrieval at different timepoints after conditioning.

(a, upper) Schematic for cFos experiments. (a, lower) Micrographs showing cFos expression in dMT in the conditioned groups following fear retrieval at 6 h, 24 h, and 7 d timepoints. (b, upper) Fear retrieval at 6 h (n= 4–5 per group) increased the number of cFos positive neurons (per 0.1 mm2) in the prelimbic prefrontal cortex (PL; P= 0.03, t= 2.65) and basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA; P= 0.02, t= 2.85), but not in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT; P= 0.96, t= 0.04). (b, middle) Fear retrieval at 24 h (n= 3–4 per group) increased the number of cFos positive neurons in PL (P= 0.002, t= − 5.43), PVT (P= 0.007, t= 3.22), BLA (P= 0.04, t= −2.67) and lateral portion of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeL; P= 0.01, t= −3.80). (b, lower) Fear retrieval at 7 d (n= 5–6 per group) increased the number of cFos positive neurons in PL (P= 0.002, t= 4.21), PVT (P< 0.001, t= 4.83) and medial portion of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeM; P= 0.02, t= 2.69). (c) cFos levels (as percentage of control) in PVT and BLA following fear retrieval at 6 h, 24 h and 7 d timepoints. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; Unpaired t-test between control and conditioned groups; *P < 0.05.

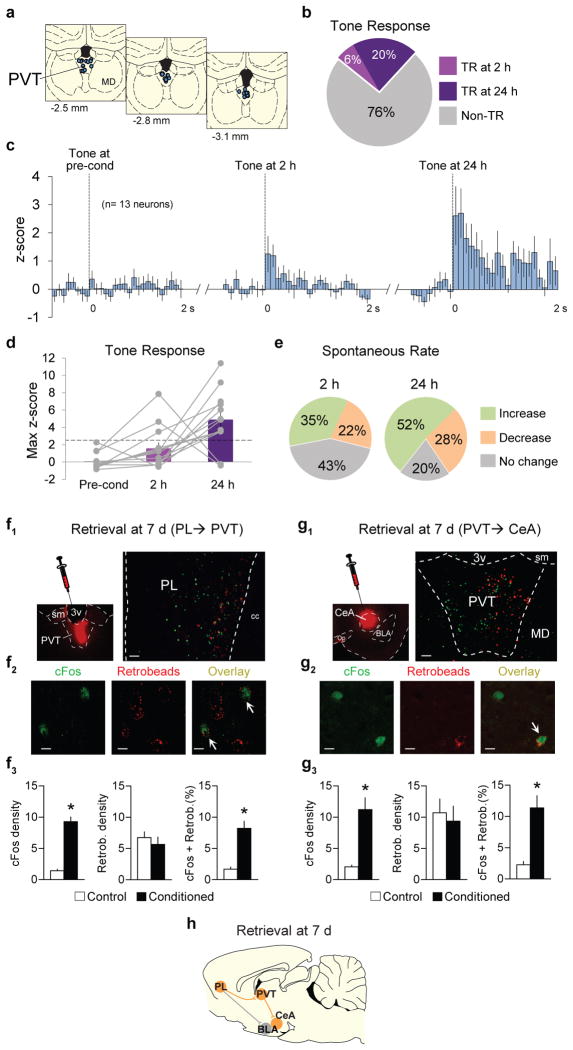

Our cFos findings suggest a time-dependent activation of PVT after fear conditioning, however, they do not indicate if this activation represents an increase in tone responses, spontaneous activity, or both. To address this, we recorded from the same PVT neurons during both early and late timepoints after fear conditioning (Fig. 3a–e, Extended Data Fig. 4). Compared to 2 h after conditioning, a higher percentage of PVT neurons exhibited conditioned tone-responses 24 h after conditioning (24 h= 11/54, 20%; 2 h= 3/54, 6%; Fisher exact test, p = 0.04; Fig. 3a–c). Moreover, the average magnitude of tone responses increased significantly from 2 h to 24 h in the same set of neurons (F(2,36)= 13.29, p= 0.003, Fig. 3c). Interestingly, 12 out of 13 PVT neurons that were tone responsive at 24 h were not tone responsive at 2 h (Fig. 3d), consistent with a time-dependent recruitment of PVT neurons. In addition to tone responses, conditioning-induced changes in the spontaneous firing rate of PVT neurons were greater at 24 h compared to 2 h (24 h= 43/54, 80%; 2 h= 31/54, 43%; Fisher exact test, p= 0.02; Fig. 3e).

Figure 3. Time-dependent increases in tone responses of PVT neurons following fear conditioning.

(a) Diagram of recording placements in PVT. Coordinates from bregma. (b) Percentage of tone responsive (TR) neurons at 2 h and 24 h following conditioning (n= 54 neurons, 6% tone responsive at 2 h, 20% tone responsive at 24 h, Fisher exact test, P= 0.04). (c) Average peri-stimulus time histograms of all PVT neurons that were significantly tone responsive at either 2 h or 24 h after conditioning (n=13 neurons). (d) Maximum z-score for group data (bars) or individual data (gray lines, n=13 neurons). Dashed line indicates a z-score criterion of 2.58. (e) Changes in spontaneous firing rates of PVT neurons at 2 h (left) and 24 h (right) after conditioning, compared to pre-conditioning. Changes at 24 h were significantly greater than 2 h (n= 54 neurons; 24 h= 80%; 2 h= 57%, Fisher exact test, P= 0.02). (f1,left) Micrograph showing the site of retrobeads infusion into PVT. (f1, right) Micrograph showing PL neurons projecting to PVT (retrogradely labeled, red) expressing immunoreactivity for cFos (green) following fear retrieval at 7 d. Scale bar,100 μm. (f2) Confocal images showing cFos labeling (left), retrobeads labeling (middle), and overlay (right) of PVT-projecting PL neurons (white arrows). Scale bar,10 μm. (f3) Fear retrieval at 7 d increased the number of cFos positive neurons (per 0.1 mm2) in PL (left, P= 0.003, t= 8.74), but the number of retrogradely labeled PL neurons was the same between groups (middle, P= 0.51, t= −0.7). Retrieval increased the percentage of retrogradely labeled PL neurons expressing cFos (right, P= 0.004, t= 4.83; n=3–4 per group). (g1,left) Micrograph showing the site of retrobeads infusion into CeA. (g1,right) Micrograph showing PVT neurons projecting to CeA (retrogradely labeled, red) expressing immunoreactivity for cFos (green) after fear retrieval at 7 d. Scale bar,100 μm. (g2) Confocal images showing cFos labeling (left), retrobeads labeling (middle), and overlay (right) of CeA-projecting PVT neurons (white arrow). Scale bar,10 μm. (g3) Fear retrieval at 7 d increased the number of cFos positive neurons (per 0.1 mm2) in PVT (left, P= 0.03, t= 3.71), but the number of retrogradely labeled PVT neurons was the same between groups (middle, P= 0.79, t= −0.28). Retrieval increased the percentage of retrogradely labeled PVT neurons expressing cFos (right, P= 0.03, t= 3.61; n=2–3 per group). (h) Schematic of potential circuit mediating fear retrieval at 7d timepoint. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; Unpaired t-test between control and conditioned groups; *P < 0.05.

The pattern of cFos activation we observed (Fig 2b) suggests that activation of PVT neurons at 7 d may involve inputs from PL and outputs to CeA. To further address this, we injected a retrograde tracer (retrobeads) into either PVT or CeA and measured co-labeling with cFos in PL and PVT, respectively. Accordingly, retrieval at 7 d activated PL neurons projecting to PVT (Fig 3f), as well as PVT neurons projecting to CeA (Fig 3g). Taken together, our data suggest that PL-PVT and PVT-CeA pathways may be necessary for fear retrieval at late (7d), but not early (6 h) timepoints (Fig. 3h).

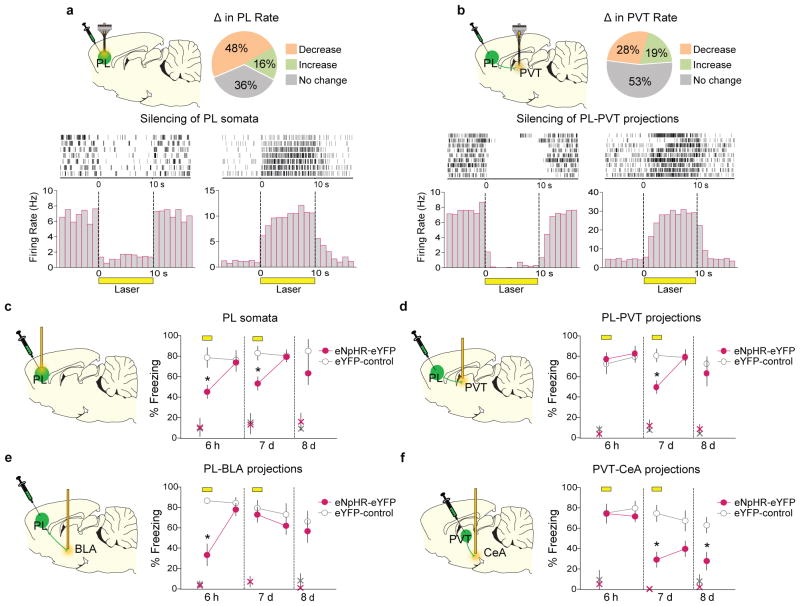

To directly test these hypotheses, we used an optogenetic approach to silence specific projections at these two timepoints, within the same animal. PL was infused with an adeno-associated viral vector (AAV-5) expressing the light sensitive chloride pump halorhodopsin 21 combined with enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP), under the control of a CaMKIIα promoter favoring expression within pyramidal neurons (AAV5:CaMKIIα::eNpHR3.0-eYFP)22,23. In anesthetized rats, laser illumination of PL somata reduced the firing rate (24 out of 50 tested, 48%) or in some cases increased the firing rate (8 out of 50 tested, 16%) of PL neurons (Fig 4a, Extended Data Fig. 5a). Neurons that reduced their rate showed shorter response latencies than neurons that increased their rate, suggesting direct vs. indirect responses, respectively. Furthermore, silencing PL terminals within the PVT either reduced (13 out of 47 tested, 28%) or increased (9 out of 47 tested, 19%) the firing rates of PVT neurons (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 5b), without significant differences in response latency. Our observation of both short and long response latencies in PVT neurons (Extended Data Fig. 5b) suggests that PL may influence PVT both directly and indirectly.

Figure 4. Time-dependent shift of retrieval circuits after conditioning.

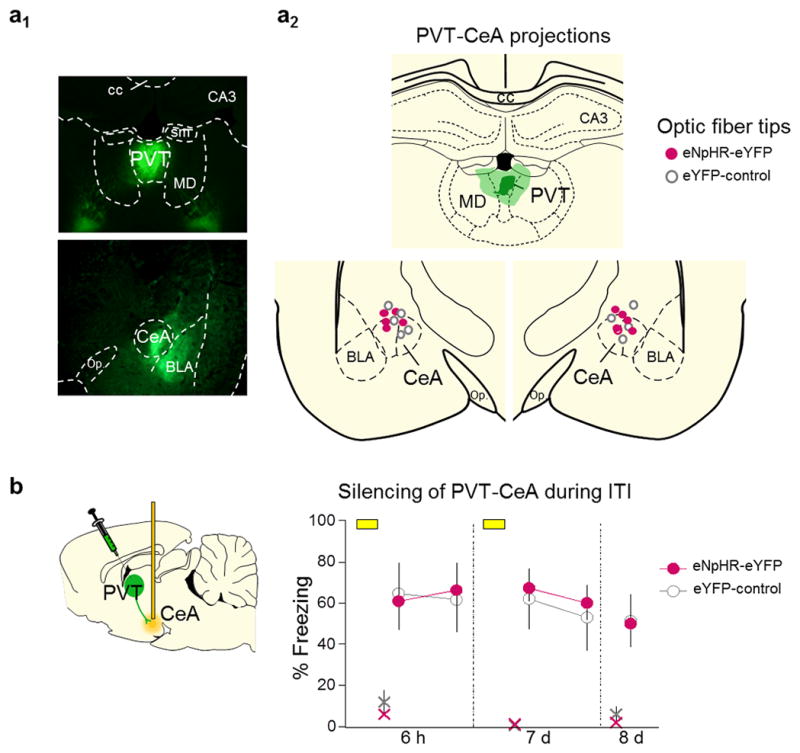

(a, upper) Changes in PL firing rate with illumination of PL in rats expressing eNpHR-eYFP in PL (n= 50 neurons; 48% decreased, 16% increased; 36% did not change; Unpaired t-test; all P’s < 0.05). (a, lower) Raster plot and peri-stimulus time histogram (PSTH) of representative PL neurons responding to illumination in rats expressing eNpHR-eYFP in PL. PL neurons showed inhibition (left) or excitation (right). (b, upper) Changes in PVT firing rate following illumination of PL terminals in PVT in rats expressing eNpHR-eYFP in PL (n= 47 neurons; 28% decreased, 19% increased; 53% did not change; Unpaired t-test; all P’s < 0.05). (b, lower) Raster plot and PSTH of representative PVT neurons responding to illumination of PL inputs in PVT in rats infused with eNpHR-eYFP in PL. PVT units showed inhibition (left) or excitation (right). (c) Illumination (yellow bar) of PL somata reduced freezing to tones at both 6 h (F(1,10)= 15.1, P= 0.003) and 7 d (F(1,10)= 20.3, P= 0.002) in the eNpHR-eYFP group (n= 7), compared to the eYFP-control group (n= 5). (d) Illumination of PL inputs in PVT significantly reduced freezing at 7 d (F(1,9)= 18.7, P= 0.002), but not 6 h (F(1,10)= 0.06, P= 0.81) (eNpHR-eYFP: n= 7; control: n= 4). (e) Illumination of PL inputs in BLA significantly reduced freezing at 6 h (F(1,16)= 26.0, P< 0.001), but not 7 d (F(1,16)= 0.64, P= 0.43) (eNpHR-eYFP: n= 8; control: n= 10). (f) Illumination of PVT inputs in CeA significantly reduced freezing at 7d (F(1,11)= 11.9, P= 0.005), but not 6 h (F(1,11)= 0.19, P= 0.67) (eNpHR-eYFP: n= 8; control: n= 5). Freezing remained reduced the day following illumination (P= 0.018). Repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. Data are shown as mean ± SEM in blocks of 2 trials; *P< 0.05. Small “x” indicates baseline (pre-tone) freezing levels.

We then determined the effects of PL silencing on retrieval of fear memory. Silencing PL somata impaired retrieval at both 6 h and 7 d (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 1f,6a,10a), however, silencing PL projections to PVT impaired retrieval at 7 d, but not at 6 h (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 1g, 6b, 10b). In contrast, silencing PL projections to BLA impaired retrieval at 6 h, but not at 7 d (Fig. 4e, Extended Data Fig. 1h, 6c, 10c). Thus, fear retrieval initially depends on PL-BLA circuits, but shifts to PL-PVT circuits with the passage of time. This shift likely involves different ensembles of neurons, as PL neurons projecting to PVT vs. BLA are located in different layers of PL8,16 (Extended Data Fig. 7).

Which outputs of PVT could mediate fear retrieval? PVT sends dense projections to CeA 18,19,24, and we observed that retrieval at 7 d activated PVT neurons projecting to CeA (Fig. 3g). Accordingly, silencing PVT projections to CeA impaired retrieval at 7 d, but not at 6 h (Fig. 4f and Extended Data Fig. 1i, 6d, 10d). Retrieval remained impaired the day following silencing (day 8), suggesting that activation of PVT-CeA circuits is necessary for maintenance of fear memory. It is unlikely that impaired retrieval at 7 d is caused by diffusion of the laser from CeA to adjacent BLA because silencing BLA somata at 7 d did not impair retrieval (Extended Data Fig. 1j, 8, 10e). Silencing PVT-CeA projections during the inter-tone interval had no effect (Extended Data Fig. 1k, 9), suggesting that the tone-responses of PVT neurons (Fig. 3c) are essential for memory retrieval and maintenance. The necessity of PVT-CeA projections at late timepoints agrees with an accompanying study (Penzo et al, 2014, this issue) showing that PVT inputs to CeA are necessary for the long-term (24 h), but not short-term (3 h), induction of conditioning-induced plasticity in CeA that encodes fear memory14.

Our findings suggest a time-dependent reorganization of the neural circuits required for fear memory retrieval. While fear behavior is constant with time, the circuits mediating this behavior are not. Retrieval of fear memories long after conditioning may activate PL inputs to PVT, which could excite PVT neurons projecting to CeA, thereby activating CeA neurons to elicit fear responses. Recruitment of PVT may serve to integrate fear with other adaptive responses such as stress25, thereby strengthening fear memory in amygdala circuits. Dysregulation of time-dependent changes in retrieval circuits may contribute to exacerbated fear responses occurring long after the traumatic event, in individuals with anxiety disorders.

METHODS

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine in compliance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Subjects

A total of 266 male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 300–360 g were housed and handled as described previously26. Rats were maintained on a restricted diet (18g/day of standard rat chow) until they reached 85% of their original body weight. They were then trained to press a bar for food on a variable interval schedule of reinforcement (VI-60 s)26, except for unit recording experiments and Extended Data Fig 2a. Pressing a bar for food ensures a constant level of activity in which freezing behavior can be reliably measured during fear conditioning sessions26. For optogenetic experiments, rats were randomly assigned to each of the experimental groups. For muscimol inactivation and immunocytochemistry experiments, groups were assigned after matching for freezing levels during the conditioning session. Sample size was based on estimations by power analysis with a level of significance of 0.05 and a power of 0.9.

Surgeries

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (5%) in an induction chamber. Rats were positioned in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA) and anesthetized with isoflurane (2.5%) through a facemask. For muscimol inactivation experiments, double 26-gauge guide cannulas with 9 mm of length (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA) were implanted targeting the dorsal midline thalamus [dMT; anteroposterior (AP), − 2.6 mm from bregma; mediolateral (ML), ±0.6 mm from midline; dorsoventral (DV), − 4.5 mm from skull surface] or the prelimbic cortex (PL; AP: + 2.8 mm; ML: ± 0.6 mm; DV: − 2.6 mm)27. Stainless steel obturators (33-gauge) were inserted into the guide cannulas to avoid obstructions until infusions were made. The cannula was fixed to the skull with anchoring screws and acrylic cement. For retrograde labeling experiments, a 0.5 μl syringe (Hamilton®, Reno, NV) was used to infuse 0.1 μl of green or red fluorescently labelled latex retrobeads (Lumafluor Inc®) per site. Retrobeads were chosen because they show very limited diffusion from the injection site even weeks after infusion. For optogenetic experiments, a double 22-gauge guide cannula (9 mm of length) was implanted targeting PL. A single guide cannula (12 mm of length) was implanted aiming the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT; AP: − 2.6 mm; ML: ± 2.0 mm; DV: − 4.7 mm, 20° angle), or bilaterally implanted aiming the basolateral amygdala (BLA; AP: − 2.6 mm; ML: ± 4.8 mm; DV: − 7.6 mm) or the central amygdala (CeA; AP: − 2.6 mm; ML: ± 4.2 mm; DV: − 6.7 mm). An injector extending 1 mm past the cannula tip was used to inject 0.5 μl of virus at a rate of 0.05 μl/min. After infusion, the injector was kept inside the cannula for 10 min to reduce back-flow. The injector was then removed and an optic fiber with 0.5 mm of projection was inserted into the cannula. Adhesive cement (C&B metabond; Parkell, Edgewood, NY, USA) was applied first, followed by acrylic cement to fix the guide cannula and the optic fiber to the skull. For unit-recording experiments, a moveable array of 16 microwires (50 μm, 2 × 8; NB Labs, Denison, TX) was used to record from PVT. After surgery, a triple antibiotic was applied and an analgesic (Ketofen, 2 mg/Kg) was injected intramuscularly. All rats were allowed 5–7 days for recovery, except those used for optogenetic experiments, which were allowed 6–8 weeks for virus expression.

Histology

Upon completion of experiments, rats were transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 10% buffered formalin. Brains were extracted and stored in a 30% sucrose/10% formalin solution. Coronal frozen sections were cut 40 μm thick, mounted on slides, and observed in a microscope equipped with a fluorescent lamp (X-Cite®, Series 120Q) and a digital camera. The spread of fluorescent muscimol or retrobeads, the presence of eYFP labeling, and the placement of the optic fiber tips were determined for each rat, and those located outside the target area were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Drug infusion

The GABAA agonist muscimol (fluorescent muscimol, BODIPY TMR-X conjugate, Sigma-Aldrich) was used to enhance GABA-A receptor activity, thereby inactivating target structures. Infusions were made 30 min before testing at a rate of 0.2 μl/min (0.11 nmol/0.2 μl/per side), according to a previous study5. To inhibit the signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK) signaling cascade within dMT, U0126 (Tocris) was dissolved in 5% DMSO and 5% Tween 80, diluted to a concentration of 2μg/μl, and infused into dMT (0.5 μl/side) at a rate of 0.25 μl/min immediately after retrieval test, according to a previous study28. To block the synthesis of protein within dMT, anisomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted in PBS and dissolved in 1M HCl. The pH was adjusted back to 7.3 with NaOH and PBS until reach a concentration of 125μg/μl. Anisomycin was infused into dMT (0.5 μl/side) at a rate of 0.25 μl/min immediately after retrieval test, according to a previous study29. Following infusion, the injectors were left in place for 1 min to allow the drug to diffuse.

Auditory fear conditioning

Rats were conditioned and tested in standard operant chambers (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, USA) located in sound-attenuating cubicles (Med Associates, Burlington, VT, USA). The floor of the chambers consisted of stainless steel bars that delivered a scrambled electric footshock. Between experiments, shock grids and floor trays were cleaned with soap and water, and chamber walls were cleaned with wet paper towels. Rats were conditioned with a pure tone (30 s, 4 KHz, 75 dB) paired with a shock delivered to the floor grids (0.5 s, 0.54 mA). All trials were separated by a variable interval averaging 3 min. Fear conditioning consisted of 5 habituation tones followed immediately by 7 conditioning tones that co-terminated with footshocks. To evaluate the role of dMT on fear retrieval, dMT was inactivated at one of 5 post-conditioning timepoints: 0.5 h, 6 h, 24 h, 7 d or 28 d, and rats were tested 30 min later in the same box with two tones. Only two post-conditioning timepoints were used for PL inactivation: 6 h or 7 d. A drug-free test was performed the day after infusion to test for fear maintenance. For immunocytochemistry experiments, naïve rats (without bar-press training) were fear conditioned (conditioned group) or exposed to tones only (unconditioned group). Both groups received two test tones at either 6 h or 7 d after conditioning, and were perfused 90 min later. For all optogenetics experiments, rats were fear conditioned and tested with 4 tones at both 6 h and 7 days after conditioning. Laser illumination was delivered during the first 2 tones at each timepoint. The following day (day 8), two tones were delivered in absence of illumination to test for fear memory maintenance. For unit-recording experiments, rats were fear conditioned and tested with 4 tones at 2 h and 24 h post-conditioning timepoints.

Open field testing and bar-pressing for food

Three days after completion of optogenetics experiments, rats were returned to the operant chambers to assess the effects of laser illumination on motivation to press for food. Average press rate was compared between 5 min trials (laser off vs. laser on), following a 5 min of acclimation period. Rats pressing < 3 or > 30 presses per min during the acclimation period were eliminated (n= 3). Locomotor activity in the open field arena (90 cm diameter) was automatically assessed (ANY-Maze, Stoelting, IL, USA) by comparing the total distance traveled between 3 min trials (laser off vs. laser on), following a 3 min acclimation period. The percentage of time spent in the center of the open field (30 cm diameter) was used as an anxiety measurement.

cFos Immunocytochemistry

Rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (450 mg/Kg i.p.) and perfused transcardially with 100 ml of saline (0.9%), followed by 500 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Brains were transferred to a solution of 30% sucrose in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at 4° C for 48 h. Brains were then frozen and cut (40 μm) in the frontal plane of the medial prefrontal cortex, dorsal midline thalamus, and amygdala. A complete series of sections was processed for immunocytochemistry with anti-cFos serum raised in rabbit (Ab-5, Oncogene Science, Cambridge, MA, USA) at a dilution of 1:20,000 overnight. The primary antiserum was localized using a variation of the avidin-biotin complex system. Sections were incubated for 2 h at room temperature in a solution of biotinylated goat antirabbit IgG (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and placed in the mixed avidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase complex solution (1: 200; ABC Elite kit, Vector Laboratories) for 90 min. Black immunoreactive nuclei labeled for cFos were visualized after 10 min of exposure to a chromogen solution containing 0.02% 3,30 diaminobenzidinetetrahydrochloride with 0.3% nickel-ammonium sulfate (DAB-Ni) in 0.05 M Tris buffer (pH 7.6) followed by incubation for 5 min in a chromogen solution with glucose oxidase (10%) and D-Glucose (10%). The reaction was stopped using potassium PBS (pH 7.4). Sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated and cover slipped. Counter sections were stained for Nissl bodies, cover slipped and examined in an optical microscope to determine the anatomical boundaries of each structure. For fluorescent cFos labeling, sections were processed with the same antibody mentioned above at a dilution of 1:2,000 overnight, and placed in a fluorescent secondary-antibody Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200; Life Technologies) for two hours. Sections were cover slipped with anti-fading mounting media (Vector Laboratories) and examined with both an epifluorescent and a confocal microscope.

Immunoreactivity quantification

cFos positive cells were counted at 20x magnification of a brightfield microscope (Olympus, Model BX51) equipped with a digital camera. Images were generated for the prelimbic (PL) subregion of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), the paraventricular (PVT) and the mediodorsal (MD) nucleus of the dorsal midline thalamus (dMT), the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA), the lateral portion of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeL), and the medial portion of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeM). Cells were considered positive for cFos-like immunoreactivity if the nucleus was the appropriate size (area ranging from 100 to 500 μm2) and shape (at least 50% of circularity), and was distinct from background. cFos positive cells were automatically counted (Metamorph software version 6.1) and averaged for each hemisphere at distinct rostro-caudal levels. For PL, counted sections at antero-posterior levels were +2.7 mm, +3.2 mm and + 3.7 mm from bregma. For dMT, counted sections at antero-posterior levels were −1.8 mm, −2.1 mm, − 2.5 mm, −2.9 mm, − 3.3 mm from bregma. For amygdala, counted sections at antero-posterior levels were − 2.3 mm and − 2.8 mm from bregma. The density of cFos positive cells (cell per 0.1 mm2) was calculated by dividing the number of cFos positive cells by the total area of each region. For fluorescent cFos and retrobeads quantification, images were generated by using both an epifluorescent microscope (X-Cite®, Series 120Q) and a confocal laser scanning microscope (model Zeiss, LSM 5 Pascal). A 40x oil immersion objective with the appropriate filter sets for cFos (488 nm) and red retrobeads (543 nm) were used. Serial Z-stack images (1 μm thick, 8–10 optical planes) through multiple sections were acquired (Axioplan 2 Imaging) using identical pinholes, gain and laser settings. cFos and retrobeads positive neurons were automatically counted using commercial software (Metamorph version 6.1; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). cFos colocalization with retrobeads was manually quantified by an experimenter blind to experimental groups by measuring the percentage of retrogradely labeled neurons in both PL and PVT expressing cFos.

Virus-mediated gene expression

The adeno-associated viruses (AAV, serotype 5) were obtained from the University of North Carolina Vector Core (Chapel Hill, NC, USA). Viral titers were 3 × 1012 particles/ml for AAV5:CaMKII::eYFP and 4 × 1012 particles/ml for AAV5:CaMKIIα::eNpHR3.0-eYFP. The use of CaMKII promoter enables transgene expression favoring pyramidal neurons22. Viruses were housed in an −80° C freezer. Dual-optic fibers (0.22 NA, 200 μm core; 10 mm length, Doric Lenses, Quebec, Canada) were implanted in PL, whereas mono-optic fibers were implanted singly in PVT or bilaterally in CeA and BLA (0.22 NA, 200 μm core, 13 mm length, Doric Lenses).

Illumination

Yellow laser was generated by a 593.5 diode-pumped solid-state laser (DPSS, MGLF 593.5; OEM Laser Systems, East Lansing, MI, USA). Laser was passed through a shutter/coupler (200 μm core, Ozoptics, Ottawa, ON, Canada), patchcord (200 μm core, Doric Lenses), rotary joint (200 μm core, 1 × 2, Doric Lenses), mono or dual patchcord (0.22 NA, 200 μm core, Doric Lenses), and optical fiber to reach the brain. The power density estimated at the tip of the optic fiber was of 5 mW for illumination of somata and 10 mW for illumination of projection sites. Yellow laser was initiated 10 s prior to tone onset, given the long response latencies observed in some PL and PVT neurons (see Extended Data Figure 6), and persisted throughout the 30 s tone. Rats were familiarized with the patchcord for at least 3 days before starting each behavioral session.

Optrode recording

Rats infected with eNpHR-eYFP in PL were anesthetized with urethane (1 g/Kg, i.p.; Sigma-Aldrich) and placed in a stereotaxic. An optrode consisting of an optic fiber surrounded by 8 single unit-recording wires (NB Labs) was inserted directed to PVT (−3.1 mm anterior, 1.8 mm lateral, 5.5 mm ventral from bregma with a 20° angle). The optrode was ventrally advanced in steps of 0.03 mm. Single units were monitored online (RASPUTIN software, Plexon Inc). When a single unit was isolated, a 593.5 nm laser was activated for 10 s within a 20 s period, at least 5 times. Single units were recorded and stored for spike sorting (Offline Sorter, Plexon Inc) and spike train analysis (Neuroexplorer, NEX Technologies) as described for single-units recording methods.

Single unit recording

Rats were implanted with electrode arrays consisting of 16 fine wires (50 μm, 2 by 8, NB Labs, Denison, TX). Stereotaxic coordinates for PVT electrodes were: AP: −1.8 to −3.8 mm; ML: ±1.8 mm and DV: − 5.5 mm, with a 20° angle. Rats were fear conditioned and tested for fear retrieval with 4 tones presented at 2 h and 24 h after conditioning. Eleven rats were used, with 2 – 9 neurons per rat for a total of 54 neurons. Waveforms exceeding a voltage threshold were amplified (gain x 100), digitized at 40 kHz (MAP, Plexon, Dallas, TX) and stored onto disk. Single units were classified as maintained throughout all timepoints (preconditioning, 2 h, and 24 h) based on waveform features such as valley-to-peak and amplitude measurements (Offline Sorter; Plexon, Dallas, TX; Extended Data Fig. 7)30. Automated processing was carried out using a valley-seeking scan algorithm and then evaluated using sort quality metrics. Spikes with interspike intervals < 1 ms were excluded. Spike trains were analyzed with commercial software (Neuroexplorer, NEX Technologies, Littleton, MA) for calculating firing rate and tone responses. Tone responses for 100 ms bins were calculated as z-scores normalized to ten pre-tone bins of 100 ms. Significantly tone responsive neurons showed z-scores > 2.58 (p < 0.01, two-tailed) in either the first or second 100 ms bin following tone onset. Spontaneous firing rate was collected before the conditioning session and before both retrieval sessions for 3 min. Between recording sessions, rats were unplugged and returned to their home-cage. At the end of the recording sessions, a microlesion was made by passing anodal current (25 mA for 25 s) through the active wires to deposit iron in the tissue. After perfusion, brains were extracted and stored in a 30% sucrose/6% of ferrocyanide solution to stain the iron deposits.

Data collection and analysis

Behavior was recorded with digital video cameras (Micro Video Products, Bobcaygeon, Ontario, Canada) and freezing was measured using commercially available software (Freezescan, Clever Systems, Reston, VA, USA). Press rate was measured using automated software (Graphic State, Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, USA). Distance traveled in the open field was measured using an automated video-tracking system (ANY-maze, Stoelting Co, Wood Dale, IL, USA). Although experimenters were not blind to group allocation, automated counting was used for most measurements. Manual counting was only used to quantify the percentage of co-labeling between cFos and retrobeads (Fig 3f,g) and was done by an experimenter blind to experimental groups. Parametric analysis was used since the data did not deviate substantially from a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk normality test, all p’s > 0.05). Similar variance was observed in all the groups statistically compared (F-Test two-sample for variance before t-test, Barttlet’s Chi-Square test before ANOVA; all p’s > 0.05). All graphs and numerical values in the figures are presented as mean ± SEM. Trials were averaged in blocks of two and compared with repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc comparisons when appropriate (STATISTICA; Statsoft, Tulsa, OK). All Student’s t-tests used were two-tailed. A small percentage of rats (3 %) were excluded from analysis because they did not exceed criteria for acquisition of conditioned freezing (>30 % freezing in at least one trial). No further exclusions were made.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Conditioning levels in muscimol and optogenetic experiments.

In the muscimol experiments, levels of freezing to tones (pre-treatment) for the habituation phase (first two blocks) and conditioning phase (last three blocks) were similar for saline (SAL, white circles) and muscimol (MUS, green circles) groups at 0.5 h (a), 6 h (b), 24 h (c), 7 d (d) and 28 d (e). In the optogenetic experiments, freezing levels were similar for the eNpHR-eYFP groups (red circles) and the control groups (white circles) prior to manipulation of the following regions or pathways: PL-somata (f), PL-PVT projections (g), PL-BLA projections (h), PVT-CeA projections (i), BLA somata (j) and PVT-CeA projections during ITI (k). Data are shown as mean ± SEM in blocks of two trials.

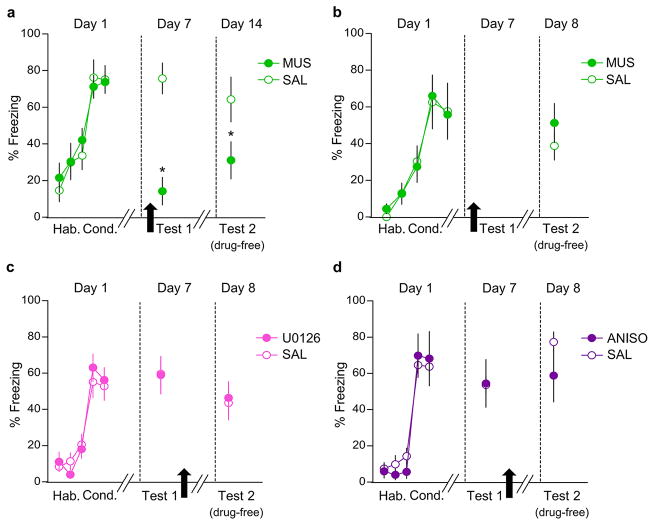

Extended Data Fig. 2. Neural activity in dMT, but not MAP-Kinase cascade or protein synthesis, is necessary for memory maintenance following reactivation.

(a) Freezing to tones during habituation (Hab.; first two blocks of day 1), conditioning (Cond.; last three blocks of day 1), test 1 (day 7), and test 2 (drug-free test; day 14) performed 7 days after dMT infusion of saline (SAL, white circles, n= 10) or muscimol (MUS, green circles, n= 14), in rats never given bar-press training. Infusion of MUS into the dMT impaired fear retrieval during test 1 (t= −4.35, P< 0.001), and also one week later during test 2 (t= −2.14, P= 0.04). (b) Freezing to tones during habituation (Hab.; first three blocks of day 1), conditioning (Cond.; last three blocks of day 1) and drug-free test (day 8) performed 24 h after dMT infusion of saline (SAL, n= 5) or muscimol (MUS, n= 7). Rats were infused in their home cage without fear reactivation. MUS infused this way had no effect on fear retrieval the following day (t= −0.88, P= 0.39). (c) Intra-dMT infusion of MAP-Kinase inhibitor U0126 (1 μg/0.5μl/side, n= 11) immediately after a two-tone test on day 7 did not alter freezing levels during a drug-free test performed the following day, compared to a vehicle control (VEH, n= 9, t= 0.37, P= 0.71). (d) Intra-dMT infusion of the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin (ANISO, 62.5μg/0.5μl/side, n= 7) immediately after a two-tone test on day 7 did not alter freezing levels during a drug-free test performed the following day, compared to vehicle control (VEH, n= 5, t=1.33, P=0.21). One-way ANOVA repeated measures was used on day 1. Unpaired t-test between SAL and MUS groups were used on days 7, 8, and 14. Data are shown as mean ± SEM in blocks of two trials; *P< 0.05.

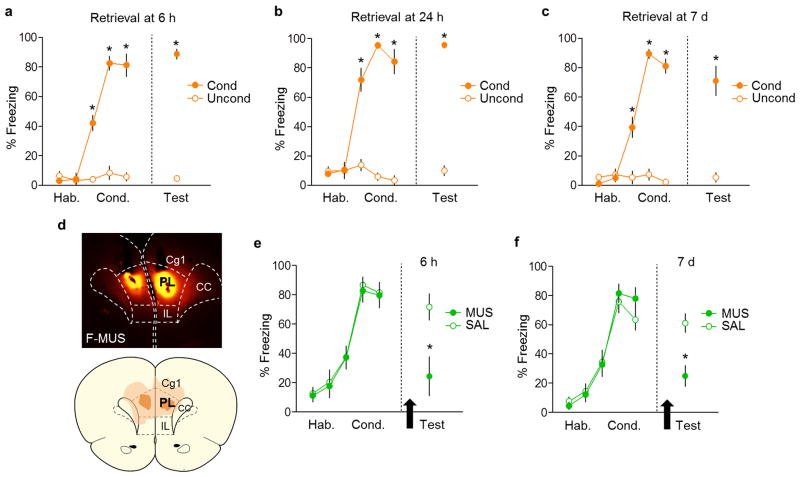

Extended Data Fig. 3. Conditioning levels for cFos experiments, and the effects of PL inactivation at early vs. late timepoints.

(a) Freezing levels for conditioned (n= 4) and unshocked control (n= 5) groups during fear conditioning and retrieval at 6 h timepoint. The conditioned group showed a significant increase in freezing compared to controls (F(5,35)= 76.12, P< 0.001). (b) Freezing levels for conditioned (n= 3) and control (n= 4) groups during fear conditioning and retrieval at 24 h timepoint. The conditioned group showed a significant increase in freezing compared to controls (F(5,25)= 40.07, P< 0.001). (c) Freezing levels for conditioned (n= 5) and control (n= 6) groups during fear conditioning and retrieval at 7 d timepoint. The conditioned group showed a significant increase in freezing compared to controls (F(5,45)= 49.88, P< 0.001). Rats were sacrificed and perfused for cFos immunocytochemistry 90 min after the fear retrieval test. Repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. (d, upper) Representative micrograph showing the site of fluorescent MUS injection into PL. (d, lower) Orange areas represent the minimum (darker) and the maximum (lighter) spread of muscimol into PL. (e) PL inactivation impaired fear retrieval at 6 h (F(1,11)= 7.92, P= 0.01, SAL: n= 6; MUS: n= 7) (f) In separate animals, PL inactivation also impaired fear retrieval at 7 d after conditioning (F(1,14)= 13.8, P= 0.002, SAL: n= 8; MUS: n= 8). The retrieval test was performed 30 min after infusion of SAL or MUS (black arrows). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. Data are shown as mean ± SEM in blocks of two trials; *P< 0.05. Legend: Hab= habituation, Cond= conditioning.

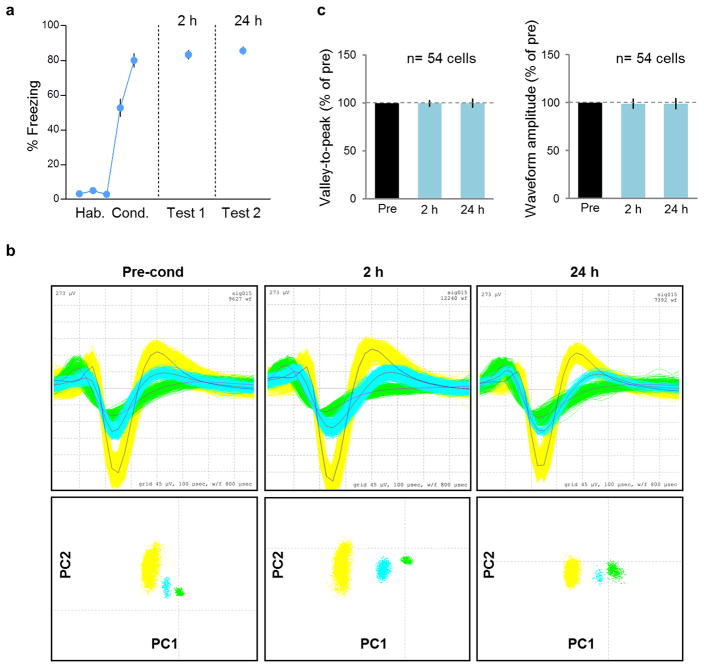

Extended Data Fig. 4. Conditioning levels for unit recording experiments, and waveform characteristics across recording sessions.

(a) Freezing levels to tones during habituation (first two blocks), conditioning (last three blocks), test 1 (2 h) and test 2 (24 h) in rats never given bar-press training. Rats showed similar levels of freezing during retrieval at 2 h and 24 h after conditioning (n= 11). Data are shown as mean ± SEM in blocks of two trials. (b, top) Waveforms of three representative PVT neurons recorded during pre-conditioning (left), 2 h postconditioning (middle), and 24 h post-conditioning (right). (b, bottom) Principal component analysis of these cells’ waveforms at all three timepoints. (c, left) Average valley-to-peak time, and (c, right) average waveform amplitude for all neurons (n= 54), shown as percent of preconditioning values. 53/54 neurons were unchanged (100% of pre-conditioning value) at both timepoints (2 h, 24 h) for one or both waveform parameters. One neuron showed 90% of preconditioning valley-to-peak time at both 2h and 24h, and ranged from 88–100% of preconditioning amplitude.

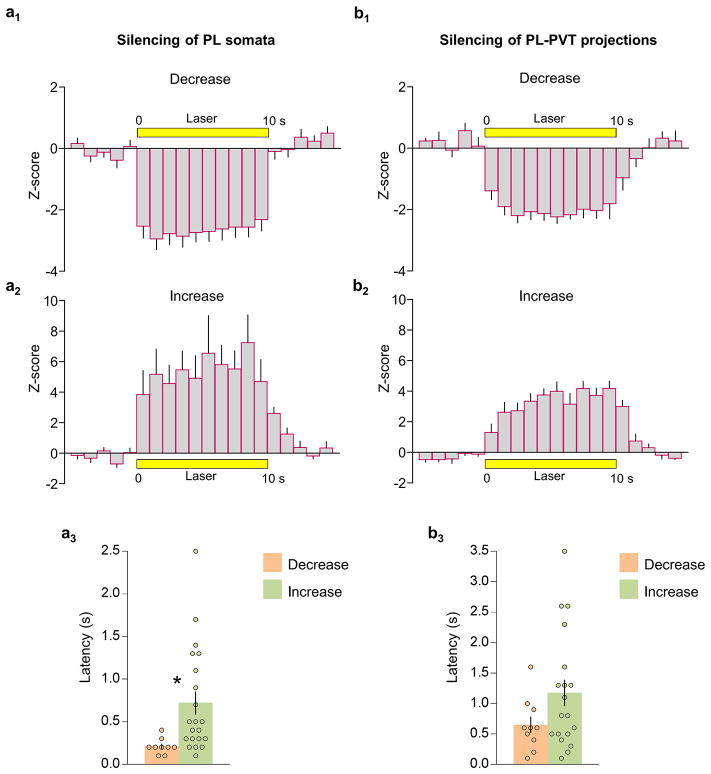

Extended Data Fig 5. Average firing rate and latency data for laser illumination of PL somata and PL terminals in PVT expressing eNpHR-eYFP.

(a1) Average peri-stimulus time histogram (PSTH) of PL neurons that decreased (24 out of 50) or increased (8 out of 50) (a2) their firing rate during laser illumination of PL somata. (a3) Latency of PL neuronal responses to laser illumination of PL somata (Paired Student’s t-test, P= 0.02). (b1) Average PSTH of PVT neurons that decreased (13 out of 47) or increased (9 out of 47) (b2) their firing rate during laser illumination of PL terminals in PVT. (b3) Latency of PVT neuronal responses to laser illumination of PL terminals in PVT (Paired Student’s t-test, P= 0.11). PSTHs are shown in bins of 1 s. Response latency was measured in bins of 100 ms; *P< 0.05.

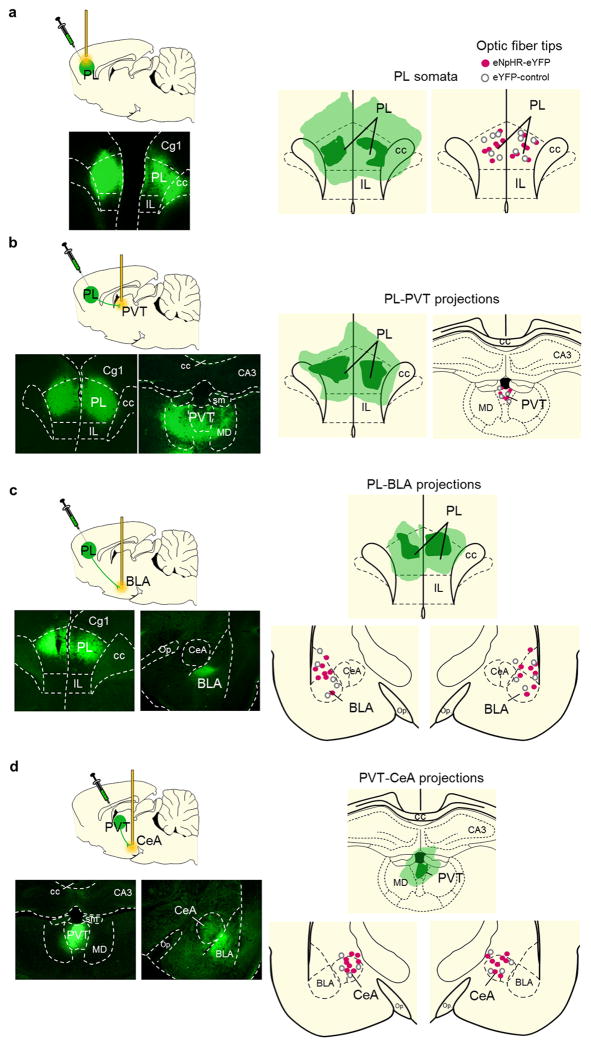

Extended Data Fig. 6. Location of eNpHR-eYFP expression and optical fibers.

(a, left) Representative micrograph showing eNpHR-eYFP expression in PL. (a, right) Placements of optic fiber tips in PL. (b, left) Representative micrograph showing the expression of eNpHR-eYFP in PL and its terminals in dMT. (b, right) Placement of optic fiber tips in PVT. (c, left) Representative micrograph showing the expression of eNpHR-eYFP in PL and its terminals in the amygdala. (c, right) Placement of optic fiber tips in BLA. (d, left) Representative micrograph showing the expression of eNpHR-eYFP in PVT and its terminals in the amygdala. (d, right) Placement of optic fiber tips in CeA. Micrographs were obtained 8–10 weeks after virus infusion. Legend: PL- prelimbic cortex, IL- infralimbic cortex, dMT- dorsal midline thalamus, BLA- basolateral nucleus of the amygdala, PVT- paraventricular thalamus; MD- mediodorsal thalamus, CeA- central nucleus of the amygdala, CA3- hippocampal region, cc- corpus callosum, op.- optical tract.

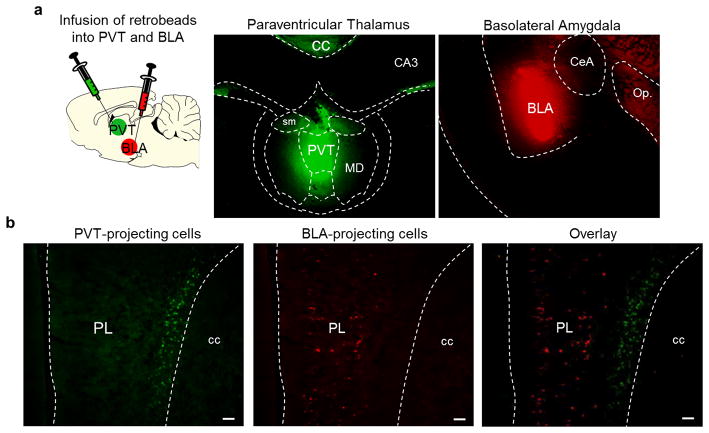

Extended Data Fig. 7. PL neurons projecting to PVT vs. BLA are located in distinct layers.

(a, left) Schematic of retrobead injections. (a, middle) Micrograph showing the site of retrobeads infusion into PVT (green) and BLA (red) (a, right) in the same rat. (b, left) PL neurons retrogradely labeled from PVT infusion (green). (b, middle) PL neurons retrogradely labeled from BLA infusion (red). (b, right) Overlay image showing absence of co-labeling between PL neurons projecting to PVT (green, deep layers) and PL neurons projecting to BLA (red, superficial layers). Scale bar, 100 μm.

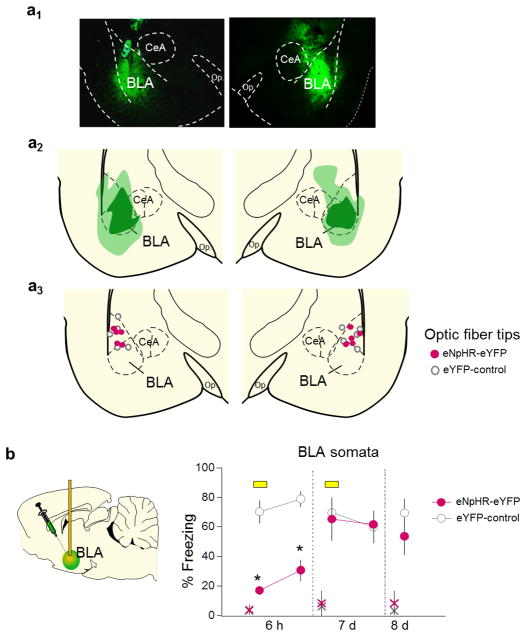

Extended Data Fig. 8. Silencing BLA somata impaired fear retrieval at early, but not late, timepoints after conditioning.

(a1) Representative micrograph showing eNpHR-eYFP expression in BLA. (a2) Green areas represent the minimum (darker) and the maximum (lighter) expression of eNpHR-eYFP in BLA. (a3) Dots represent the location of optic fiber tips within BLA. (b) Illumination of BLA soma (yellow bar) reduced freezing at 6 h (F(1,9)= 54.6, P< 0.001), but not at 7 d (F(1,9)= 10.1, P= 0.91) or 8 d (P= 0.33), in the eNpHR-eYFP group (n= 5) compared to eYFP-control group (n= 6). Repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. Data are shown as mean ± SEM in blocks of 2 trials; *P< 0.05. Small “x” indicates baseline (pre-tone) freezing levels.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Silencing PVT projections to CeA during the inter-trial interval did not impair fear retrieval.

(a1) Representative micrograph showing the expression of eNpHR-eYFP in PVT and its terminals in the amygdala. (a2,upper) Green areas represent the minimum (darker) and the maximum (lighter) expression of eNpHR-eYFP in PVT. (a2, lower) Dots represent the location of optic fiber tips within CeA. (b) Illumination (40 s) of PVT inputs to CeA during the interval between tones (3 min) did not affect freezing at 6 h (F(1,8)= 0.75, P= 0.40), 7 d (F(1,8)= 0.04, P= 0.84), or 8 d (P= 0.93), compared to eYFP-control group (n= 5 per group). Repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. Data are shown as mean ± SEM in blocks of 2 trials; *P< 0.05. Small “x” indicates baseline (pre-tone) freezing levels.

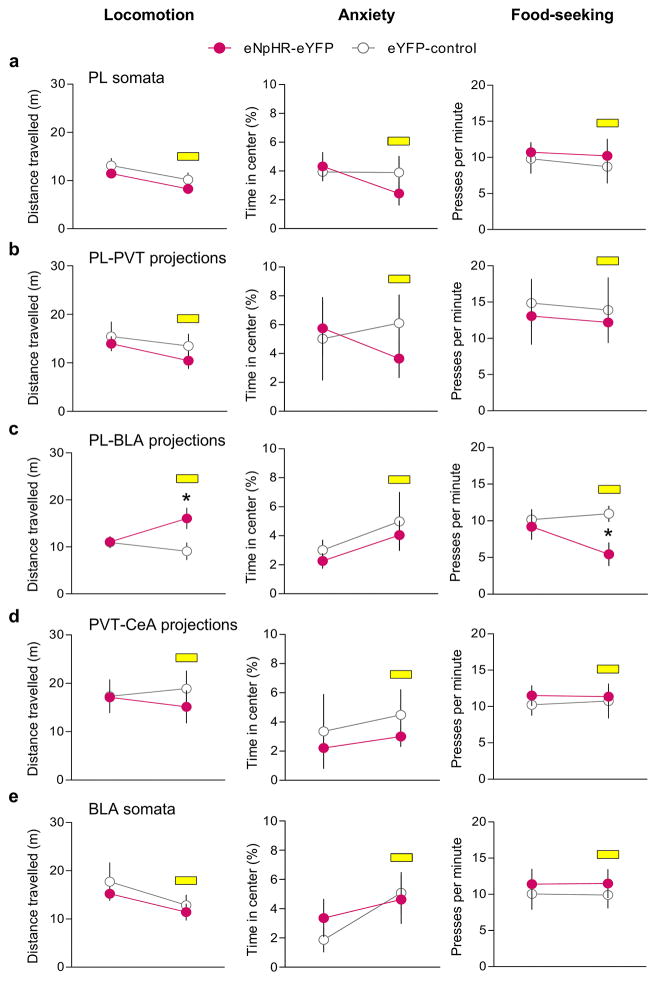

Extended Data Fig. 10.

Effects of laser illumination on locomotion, anxiety and food-seeking behavior, in rats expressing eNpHR-eYFP. Rats were tested in an open field during a 9 min session (3 min acclimation, 3 min laser off, 3 min laser on). We measured the total distance travelled (a–e, left) and the percentage of time spent in the center of the apparatus (a–e, middle) to assess locomotor activity and anxiety, respectively. We also compared the rate of pressing for food (a–e, right) in a 15 min session (5 min acclimation, 5 min laser off, 5 min laser on). Silencing of (a) PL somata (eNpHR-eYFP: n= 7, control: n= 5), (b) PL inputs to PVT (eNpHR-eYFP: n= 5; control: n=5), (d) PVT inputs to CeA (eNpHR-eYFP: n= 7, control: n= 5), or (e) BLA somata (eNpHR-eYFP: n= 5, control: n= 6) did not affect locomotion, anxiety or food-seeking. However, silencing (c) PL-BLA projections increased locomotion (F(1,12)= 12.4, P=0.004, eNpHR-eYFP: n= 6, control: n= 8) and decreased food-seeking (F(1,15)= 6.0, P=0.02, eNpHR-eYFP: n= 7, control: n= 10). Repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; *P< 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabriela Manzano-Nieves for help with the optogenetic experiments, Ada C. Felix-Ortiz for technical advice, and Kay M. Tye for comments on the manuscript. We thank Karl Deisseroth for viral constructs and the UNC Vector Core Facility for viral packaging. This study was supported by the following NIH Grants: R37-MH058883, P50-MH086400, and the University of Puerto Rico President’s Office to G.J.Q; the MBRS-RISE Program (R25-GM061838) to K.Q.L; and NSF Grant DBI-0115825 and RCMI Grant 8G12-MD007600 for the Confocal Microscope Facility.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions - F.H.M. performed behavioral, immunocytochemical and optogenetic experiments. F.H.M. and K.Q.L. performed single-unit recording in anesthetized rats. K.Q.L. performed single-unit recording experiments in behaving rats. F.H.M., K.Q.L. and G.J.Q. designed the study, interpreted results, and wrote the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jasnow AM, Cullen PK, Riccio DC. Remembering another aspect of forgetting. Front Psychol. 2012;3:175. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiltgen BJ, Tanaka KZ. Systems consolidation and the content of memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013;106:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacco T, Sacchetti B. Role of secondary sensory cortices in emotional memory storage and retrieval in rats. Science. 2010;329:649–656. doi: 10.1126/science.1183165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Restivo L, Vetere G, Bontempi B, Ammassari-Teule M. The formation of recent and remote memory is associated with time-dependent formation of dendritic spines in the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8206–8214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0966-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sierra-Mercado D, Padilla-Coreano N, Quirk GJ. Dissociable roles of prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, ventral hippocampus, and basolateral amygdala in the expression and extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:529–538. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgos-Robles A, Vidal-Gonzalez I, Quirk GJ. Sustained conditioned responses in prelimbic prefrontal neurons are correlated with fear expression and extinction failure. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8474–8482. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0378-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtin J, et al. Prefrontal parvalbumin interneurons shape neuronal activity to drive fear expression. Nature. 2014;505:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S, Kirouac GJ. Sources of inputs to the anterior and posterior aspects of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Brain Struct Funct. 2012;217:257–273. doi: 10.1007/s00429-011-0360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maren S. Neurobiology of Pavlovian fear conditioning. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:897–931. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gale GD, et al. Role of the basolateral amygdala in the storage of fear memories across the adult lifetime of rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3810–3815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4100-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansen JP, Cain CK, Ostroff LE, LeDoux JE. Molecular mechanisms of fear learning and memory. Cell. 2011;147:509–524. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogan MT, Staubli UV, LeDoux JE. Fear conditioning induces associative long-term potentiation in the amygdala. Nature. 1997;390:604–607. doi: 10.1038/37601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, et al. Experience-dependent modification of a central amygdala fear circuit. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:332–339. doi: 10.1038/nn.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciocchi S, et al. Encoding of conditioned fear in central amygdala inhibitory circuits. Nature. 2010;468:277–282. doi: 10.1038/nature09559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vertes RP. Differential projections of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortex in the rat. Synapse. 2004;51:32–58. doi: 10.1002/syn.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald AJ, Mascagni F, Guo L. Projections of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices to the amygdala: a Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1996;71:55–75. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vertes RP, Hoover WB. Projections of the paraventricular and paratenial nuclei of the dorsal midline thalamus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:212–237. doi: 10.1002/cne.21679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moga MM, Weis RP, Moore RY. Efferent projections of the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:221–238. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padilla-Coreano N, Do-Monte FH, Quirk GJ. A time-dependent role of midline thalamic nuclei in the retrieval of fear memory. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gradinaru V, et al. Molecular and cellular approaches for diversifying and extending optogenetics. Cell. 2010;141:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu XB, Jones EG. Localization of alpha type II calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase at glutamatergic but not gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) synapses in thalamus and cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7332–7336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van den Oever MC, et al. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex pyramidal cells have a temporal dynamic role in recall and extinction of cocaine-associated memory. J Neurosci. 2013;33:18225–18233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2412-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S, Kirouac GJ. Projections from the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus to the forebrain, with special emphasis on the extended amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:263–287. doi: 10.1002/cne.21502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heydendael W, et al. Orexins/hypocretins act in the posterior paraventricular thalamic nucleus during repeated stress to regulate facilitation to novel stress. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4738–4752. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quirk GJ, Russo GK, Barron JL, Lebron K. The role of ventromedial prefrontal cortex in the recovery of extinguished fear. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6225–6231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06225.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 3. Sydney: Academic; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schafe GE, et al. Activation of ERK/MAP kinase in the amygdala is required for memory consolidation of pavlovian fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8177–8187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08177.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nader K, Schafe GE, Le Doux JE. Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature. 2000;406:722–726. doi: 10.1038/35021052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tseng WT, Yen CT, Tsai ML. A bundled microwire array for long-term chronic single-unit recording in deep brain regions of behaving rats. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;201:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]