Abstract

Management of retroperitoneal sarcomas presents technical and oncological challenges. Imaging is crucial for diagnosis and to define local tumor extent. Complete gross resection at initial presentation is the best chance for cure, but there is controversy as to how this can be best achieved. There is a long-term risk of local recurrence, which is best treated with repeat resection if feasible. The roles of radiation and chemotherapy remain undefined.

Keywords: Soft tissue sarcoma, retroperitoneal sarcoma, surgery

INTRODUCTION

Retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas (RPS) comprise approximately 15% of all soft tissue sarcomas (STS) and thus, the incidence of RPS in the United States is only about 1600 per year (1). The two most common histologic types are liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma, comprising two-thirds of all RPS. Patients are most commonly diagnosed in the sixth decade, with an equal sex distribution. Median tumor size is 15–20cm (2–4). Surgery remains the primary treatment modality, with complete resection providing the only chance for cure. Local recurrence (LR), rather than distant recurrence (DR), is the major post-operative oncological concern because of the anatomical restraints of the retroperitoneum and the large size of tumors. In fact, local recurrence is the leading cause of death in patients with RPS. The roles of radiation therapy and chemotherapy remain controversial. More recent studies of more aggressive surgery and advanced radiation techniques have suggested that local recurrence can potentially be reduced, but these strategies are debatable. Newer chemotherapies and targeted agents may also play a role in the reduction of both local and distant recurrence. This chapter will discuss the surgical evaluation and treatment of patients with RPS.

HISTOLOGY

Retroperitoneal sarcomas comprise a spectrum of histologic types/subtypes with distinct biologic behavior. Liposarcomas comprise 40–50% of all RPS in large series (2–6). They are characterized genetically by amplification of chromosome 12q, with resultant increased expression of MDM2 and CDK4 (7). The identification of this genetic alteration has allowed many tumors previously designated as malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) to be re-classified as dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Retroperitoneal liposarcomas are typically either of the well-differentiated/dedifferentiated subtype, with myxoid/round cell and pleomorphic subtypes occurring very rarely (8). Well-differentiated liposarcomas (Figure 1A) appear as tumors with the density of fat, whereas dedifferentiated liposarcomas have a higher density, being hypercellular, and often occur within or adjacent to well-differentiated areas (Figure 1B). Well-differentiated liposarcomas recur locally but not distantly. Dedifferentiated liposarcomas have a higher early risk of local recurrence (within 2 years), but have an equivalent long-term cumulative risk of local recurrence compared with well-differentiated liposarcoma (8,9). Dedifferentiated liposarcomas can also metastasize to distant sites. Leiomyosarcomas are the next most common histologic type of RPS and can arise from major vessels such as the inferior vena cava (Figure 2). Almost all retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas are high grade. The disease-specific survival for patients with high grade retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas is almost identical to those with dedifferentiated liposarcomas, but with a lower rate local recurrence and a higher rate of distant metastasis (3). Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST), constituting up to 5% of RPS (3,6), are tumors that arise from the cellular components of a normal nerve, such as Schwann cells. One-third of cases are associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), where they commonly develop as malignant transformations of plexiform neurofibromas. NF1 patients have about a 15% lifetime risk of developing a MPNST (10). In the retroperitoneum, these tumors may arise from large nerves, such as the sciatic, and local recurrences may skip portions of normal nerve, complicating further attempts at local control. Solitary fibrous tumors (SFT), formerly known as hemangiopericytomas, also comprise approximately 5% of RPS (3,6). After complete resection, local recurrences are uncommon, but there is a significant rate of late distant metastasis, 10–20 years after initial diagnosis (11).

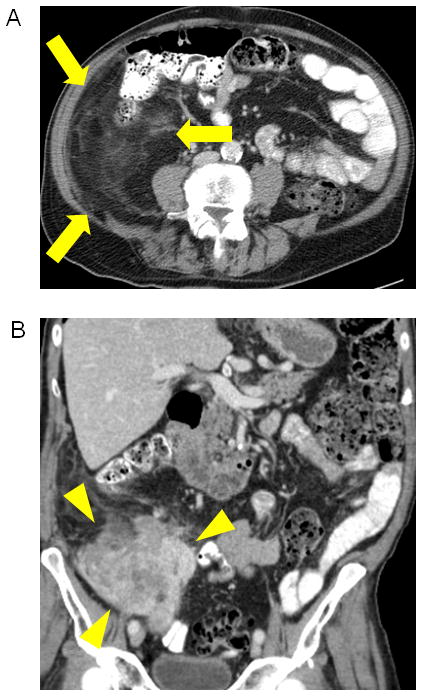

Figure 1.

Well differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcoma. (A) Axial image of right retroperitoneal well-differentiated liposarcoma which appears as an area of abnormal appearing fat (arrows). (B) Coronal image showing area of dedifferentiation, which appears as a more solid area within or adjacent to abnormal appearing fat (arrowheads).

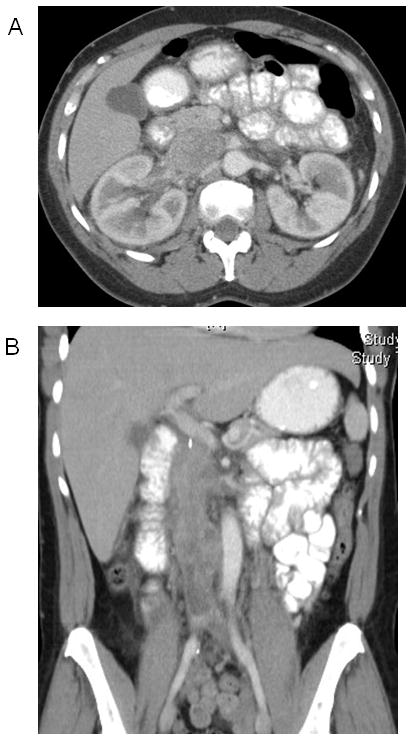

Figure 2.

Inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. (A) Axial image of an IVC leiomyosarcoma at the level of the renal veins. (B) Coronal image showing extension of tumor from liver to bifurcation.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND EVALUATION

Patients often present with an asymptomatic abdominal mass or after imaging identifies an incidental retroperitoneal mass (3). When symptoms do occur, they are due to compression of adjacent intra-abdominal structures: the bowel, leading to abdominal discomfort, early satiety, weight loss, or bowel obstruction; large veins (IVC or iliac veins), causing leg swelling; or nerves, causing lower extremity pain or weakness. In one series of 500 patients, 80% of patients presented with an abdominal mass, 42% with lower extremity neurologic symptoms, and 37% with pain (3).

The vast majority of patients will not have any identifiable genetic or environmental risk factor. However, certain genetic syndromes are associated with an increased risk of developing sarcomas. Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1, or von Recklinghausen’s disease) is associated with an approximately 15% risk of developing malignant transformation of a neurofibroma into a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) (12). Individuals with NF1 also carry an increased risk of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). Hereditary retinoblastoma and Li-Fraumeni syndrome are associated with a risk of both bone and soft tissue sarcoma.

In terms of environmental factors, radiation is capable of inducing sarcomas in soft tissue and bone. The incidence of radiation-associated sarcomas increases with the post-radiation observation period (13). Following breast irradiation, the most common radiation-induced sarcomas are angiosarcomas. The actuarial frequency of radiation-associated sarcoma at 15 to 20 years is approximately 0.5% in adults treated with radiation alone to full dose. The frequency is higher following treatment of children, especially those treated with both radiation and chemotherapy, and the frequency may reach 20% to 30% many years after treatment. Chemotherapeutic agents and exposure to a few select industrial chemicals (e.g. vinyl chloride) are likewise associated with risk of sarcoma induction. Trauma is rarely a factor in the development of these tumors with the exception of desmoid tumors. The usual history is of a traumatic incident occurring shortly before awareness of the mass, suggesting that the trauma merely brought the patient’s attention to the presence of the mass.

Most unifocal retroperitoneal tumors that do not arise from an adjacent organ will either be a RPS or a benign soft tissue tumor (e.g. Schwannoma). However, the differential diagnosis includes primary germ cell tumor, metastatic testicular cancer, and lymphoma. Patients with metastatic testicular cancer may have a testicular mass identified on physical examination or scrotal ultrasound. Patients with primary germ cell or testicular tumors will often have an elevated β-human chorionic gonadotropin or α-fetoprotein level. Patients with lymphoma may have B symptoms (fever, night sweats, and weight loss), additional lymphadenopathy, or an elevated LDH.

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis should be obtained with oral and intravenous contrast to fully evaluate the tumor and its proximity to adjacent organs, vessels, and nerves (14). For tumors that appear to consist purely of fat, the diagnosis is generally well-differentiated liposarcoma.

Two important differential diagnoses are renal angiomyolipoma and adrenal myelolipoma. Like liposarcomas, they are characterized by regions of macroscopic fat (−20 to −80 Hounsfield units). Most renal angiomyolipomas arise from the cortex and are infiltrated by a network of large vascular structures. The renal origin of exophytic angiomyolipomas may be discerned by identifying the defect in the renal capsule where the lesion is attached. Areas of hemorrhage may be present. Adrenal myelolipomas appear as well-circumscribed masses occupying the adrenal space. They have variable amounts of fat: in 50%, lesions are equal parts fat and soft tissue; in 40%, almost completely composed of fat; in 10% of lesions, they are mostly solid (15). Small punctate calcifications are seen in 25–30% of cases. Larger lesions may be associated with hemorrhage (16).

If lipomatous tumors contain areas of higher density, then these may represent areas of dedifferentiation or sclerosing components of well-differentiated liposarcoma. Conversely, it is crucial to avoid only focusing on the higher density component of the tumor and dismiss the lower density areas as normal fat. Overlooking the well-differentiated component of a mixed-density liposarcoma may lead to an incomplete resection or inappropriately small field of radiation (16). In a study from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, CT scan features accurately identified 60 out of 60 (100%) of well-differentiated liposarcomas but was less accurate in determining areas of hypercellular well-differentiated liposarcoma from areas of dedifferentiation (17).

After establishing the diagnosis of retroperitoneal sarcoma, the next step is to define its local extent. The relationship of the tumor with adjacent organs, vessels, nerves and bone must be assessed for abutment, invasion and/or encasement. Liposarcomas rarely invade major vessels, but leiomyosarcomas may originate from involved vessels such as the IVC, renal vein and gonadal vein. Tumor extension beyond the confines of the retroperitoneal space should be recognized. If the tumor extends across the diaphragm, into the inguinal canal, or through the obturator, sciatic or vertebral foramina, then this should be anticipated prior to resection (16). Clearly, there are some structures/organs that are easier to resect than others. Therefore, the surgeon must decide whether to aggressively excise the tumor and adjacent structures, or dissect just outside the pseudocapsule and risk leaving behind microscopic residual disease. This dilemma is a source of ongoing controversy among sarcoma surgeons on exactly how aggressive resections should be (see below).

Unresectability is usually determined by vascular invasion - either of the superior mesenteric vessels or the suprahepatic IVC. If nephrectomy is anticipated, then confirmation of function of the contralateral kidney is necessary.

MRI may be useful in certain circumstances such as determining the proximity of a tumor to major nerves or in patients with a contraindication to CT scan intravenous contrast.

A minority (10–20%) of patients with RPS present with metastatic disease, with the most common sites of metastatic spread being the lung and liver (2–4). A chest CT is obtained for patients with high-grade tumors, whereas a chest X-ray is sufficient for those with low-grade tumors. Although many soft tissue sarcomas are FDG-avid, PET scans only rarely identify metastases not obvious on CT, and so their use for staging is not recommended (18).

Biopsy is not required for those patients proceeding directly to the operating room. This is particularly the case for well-differentiated liposarcomas, because of their characteristic imaging features (see above). It is reasonable to biopsy when neoadjuvant therapy is being considered, or there is diagnostic doubt, e.g. if there is concern that a retroperitoneal mass may represent lymphoma or metastatic testicular cancer (which are not treated with upfront resection). Knowledge of tumor grade and histologic subtype guides use of pre-operative radiation and/or chemotherapy. Tissue is obtained by image-guided percutaneous core biopsy. Caution should be exercised in biopsying lipomatous tumors, since histologic confirmation of well-differentiated liposarcoma can be confounded by the paucity of neoplastic cells, and sampling error, in which areas of dedifferentiation are either not recognized or not sampled. Percutaneous biopsy may be difficult or dangerous due to a tumor’s proximity to large vascular structures. The risks of needle-track and intra-peritoneal seeding are very low, and can be minimized by avoiding a transperitoneal approach. It is critical that biopsy material be reviewed by an experienced sarcoma pathologist, since 6–10% of cases originally designated as sarcoma are in fact not sarcoma, and 14–27% are initially assigned the incorrect histologic subtype (19–22).

STAGING

A detailed discussion of staging systems and nomograms for STS can be found in a separate article in this seminar series. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging for RPS was derived from analysis of extremity soft tissue sarcoma (23). It includes characteristics of the primary tumor (T, size and depth), regional lymph nodes (N, negative or positive), distant metastases (M, absent or present), and grade (G1–G3). However, it does not include histologic type or subtype as a category, leading some authors to question its applicability (24–27). Nathan et al., in an analysis of 1365 RPS patients in the SEER database found that tumor grade, invasion of adjacent structures, and histologic subtype were prognostic, whereas tumor size was not (26). Anaya et al. also argued that a histology-based RPS prognostic system has major advantages over the AJCC staging system (25). This has led to the development of several post-operative nomograms specifically for patients with RPS (6,28,29). Prognostic factors in these nomograms include age, grade, histologic subtype, size, primary versus recurrent disease, multi-focality, and completeness of resection (R0/R1 vs. R2).

SURGERY

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for RPS.

Technical Aspects of Resection

Access is usually achieved through midline laparotomy. For right upper quadrant tumors displacing the right liver, a right thoracoabdominal incision will allow complete control of the inferior vena cava and right atrial access. When a tumor herniates through the midline or the left diaphragm, a left thoracoabdominal incision may be needed, unless the intra-thoracic dissection can be safely completed by enlarging the esophageal hiatus. For tumors herniating distally under the inguinal ligament, access to the external iliac and femoral vessels may be achieved either via separate S-shaped incision at the groin or by extending the midline incision distally in an oblique fashion. Where there is herniation through the sciatic notch, en bloc resection requires a counter-incision in the gluteal area (16). The patient is therefore positioned in contralateral decubitus to facilitate access to the pelvis anteriorly and posteriorly.

For tumors where complete gross resection is possible, leaving a negative microscopic margin around the entire tumor can be challenging. The EORTC-Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group recently described a standardized surgical approach to RPS (16). The anterior surface of these tumors is often covered by peritoneum and organs which can be resected with relatively low morbidity (e.g. colon, tail of pancreas, spleen, and kidney) enabling a negative anterior margin. For tumors abutting but not invading the kidney, the renal capsule may be resected en bloc with the tumor, without the need to sacrifice the kidney. In other instances, the anterior margin may be the head of the pancreas and duodenum, and performance of a pancreaticoduodenectomy may significantly increase morbidity. Laterally, the peritoneum and the transversalis fascia can be resected en bloc with the tumor. Medially, tumors can generally be dissected off of the aorta and inferior vena cava, leaving adjacent areolar tissue on the tumor as margin. The posterior margin of these tumors often abuts retroperitoneal fat and the psoas musculature, where obtaining negative margins requires visualization and sharp dissection due to the lack of anatomic dissection planes. Thus, tumors should be dissected circumferentially from anterior to posterior to optimize exposure when dissecting out the deepest parts of the tumor. Resection of major vessels, nerves, and bone is generally not necessary unless there is direct invasion. Major arteries can usually be dissected free leaving adventitia on the tumor, major nerves can be dissected free leaving epineurium on tumor, and bone can be dissected free leaving periosteum on tumor.

For IVC leiomyosarcomas, access to the tumor and the IVC is achieved using a Cattell-Braasch maneuver. After extirpation of the tumor, primary repair or autologous patching can be performed in a small subset of these tumors and is associated with minimal lower extremity edema. When this is not possible, then resection and ligation of the IVC is associated with acceptable post-operative morbidity (30). The IVC can be resected from just below the renal veins to below the bifurcation along with the right kidney without reconstruction, as long as the left gonadal and left adrenal veins are left in continuity with the left renal vein to allow collateral drainage of the left kidney. For the vast majority of patients, this results in normal left kidney function and only transient lower extremity edema, which can be mitigated by elevation and compression. While not our preference, reconstruction of the IVC has been advocated by some groups (31), but if the reconstruction thromboses, one runs the risk of clot extension into the collateral venous circulation. When IVC thrombosis is present, early intra-operative proximal control of the IVC is recommended to avoid pulmonary embolism. Placement of an IVC filter should be avoided given the risk of clot extension to the filter.

Extent of primary surgery

There is ongoing debate about how aggressive surgical resections for RPS should be, particularly regarding resection of adjacent organs and tissues. The catalysts for this debate were two European retrospective reviews analyzing the impact of more aggressive multivisceral resections on local recurrence (2,32). These “compartmental resections” comprise, for the most part, resection of adjacent kidney, colon and/or psoas, without increased resection rates of pancreatoduodenectomy, hepatectomy or vascular structures. In the first study, Gronchi et al. from the Istituto Nazionale del Tumor (INT) in Milan, Italy, retrospectively examined 288 patients with primary RPS resected between 1985 and 2007 (32). Prior to 2002, adjacent organs were generally only resected if there was direct involvement by tumor. From 2002 onward, a more aggressive policy was instituted with resection of adjacent organs and tissues. Five-year actuarial local recurrence was 48% in the less aggressive surgery group and 29% in the more aggressive surgery group, with no change in perioperative morbidity. However, the complete gross resection rate (~90%) and overall survival were the same in both time periods.

The second study is a multi-center retrospective review of 382 French patients with RPS divided patients by surgical procedure into compartmental resection of contiguous organs (32%), resection of only involved organs (35%), simple complete resection (17%), and re-excision of tumor bed (6%) (2). Complete gross resection was achieved in 73%. Margins were reported as being positive in 19%, 40% and 36% of patients undergoing compartmental resection, simple gross resection and contiguously-involved organ resection, respectively (p<0.001). However, when compartmental resection was performed, the resected colons or kidneys were never invaded. Rather, margins were positive where the tumor was not covered by viscera, particularly posteriorly. On multivariate analysis, the study found that compartmental resection of contiguous organs was associated with a 3.3-fold lower rate of local recurrence compared to only complete gross tumor resection.

Review of the multi-visceral resections performed in both studies reveals that they generally consisted of resection of uninvolved kidney, colon and/or psoas - structures that can be resected with low morbidity. These “compartmental resections” however, did not include other uninvolved adjacent viscera (pancreas, spleen, duodenum, liver), major vasculature (IVC, portal vein, aorta) and functionally significant muscles (diaphragm) whose resection is associated with much greater potential for morbidity and mortality. This policy of selective en bloc resection therefore extends to some but not all resection margins around sarcomas. As a consequence, the oncologic benefit of such resections is variable depending on the exact relationships of an individual tumor within the anatomically complex retroperitoneum. Interpretation of their results is confounded by the absence of standardization of pre-operative imaging, operative findings and pathologic review. A subsequent analysis was performed of post-operative complications of patients who underwent aggressive compartmental resections at the two highest-volume centers in the two above-mentioned articles (INT and Institut Gustave Roussy) (33). Morbidity was significant: the major complication rate was 18%, with a 12% re-operation rate and a 3% mortality rate. Resection of more than three adjacent viscera was associated with a significantly higher complication rate compared to resection of three or fewer organs (HR 2.8, 95% CI 1.3–5.7). Therefore, at this time, adoption of a frontline aggressive approach with resection of select uninvolved adjacent organs cannot be recommended given the retrospective nature of the data (fraught with selection bias), high complication rates and lack of overall survival benefit (34). There remains no consensus on the appropriate resection for RPS and no prospective trials to guide surgical practice. For operations requiring extensive organ resection or multiple surgeons from different specialties, the operation would ideally be performed at a high-volume sarcoma center. Of note, several articles on major vascular resections, liver resections, pancreaticoduodenectomies and other aggressive strategies for primary RPS have been published (30,31,35).

Results of large series and prognostic factors

Table 1 summarizes the three largest, contemporary surgical series of primary RPS, one each from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (New York, USA), the Insituto Nazionale Tumori (Milan, Italy), and the multicenter French Sarcoma Group (2,4). Each series is the most recent update from that institution/group’s sarcoma database. Consistent across these series are median age at presentation of 55–60 years, maximal tumor diameter of 15–20cm, with approximately 70% of tumors being of intermediate or high grade. Complete gross resection was achieved in 75–90% of cases, with contiguous organ resection performed in 58–91%. Use of pre-/post-operative radiation and chemotherapy ranged from 14%–37% and 16%–40%, respectively. Despite variations in both operative philosophies (as described above) and utilization of adjunctive therapies, five-year overall survival (59–66%), local recurrence (31–46%), and distant recurrence (21–24%) did not vary greatly between the three studies.

TABLE 1.

Selected Surgical Series

| Institution/Group | MSKCC* | French Sarcoma Group (2) | INT/MDACC/UCLA (6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | 1982–2010 | 1988–2008 | 1999–2009 |

| Year published | 2014 | 2014 | 2013 |

| Median follow-up (months) | 52 | 78 | 45 |

| Number of patients | 675 | 586 | 523 |

| Median age (years) | 60 | 57 | 57 |

| Primary tumors | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Median tumor size (cm) | 17 | 17 | 16 |

| Intermediate- or high-grade | 64% | 72% | 72% |

| Complete gross resection | 85% | 76% | 90% |

| Mortality | 3% | 3% | NR |

| Pre-/post-op radiation | 14% | 29% | 37% |

| Pre-/post-op chemotherapy | 16% | 17% | 40% |

| 5-year local recurrence | 39% | 46% | 31% |

| 5-year distant recurrence | 24% | 22% | 21% |

| 5- year overall survival | 59% | 66% | 57% |

submitted for publication; NR, not recorded.

Multiple series have identified prognostic factors. For overall survival, worse outcome is associated with histologic type, higher grade, multifocality, and incomplete or piecemeal resection (2,4,6,36–38). Risk factors for local recurrence include histologic subtype, grade, radiation, and type of surgery to be prognostic factors (2,3,32,38). Only one study (2) found margin to be prognostic while another study did not (3). Prognostic factors for distant recurrence (found in one or more studies) included histologic subtype, grade, and complete gross resection (3,32,36–38).

Debulking operations for primary disease

Surgeons should be wary of attempting surgery if complete surgical resection cannot be performed. In some series, incomplete resection has resulted in the same overall survival as patients undergoing biopsy alone (3,39,40). However, there may be some role for debulking unresectable RPS in very select circumstances such as for very slow growing tumors (e.g. well-differentiated liposarcomas) or for the relief of symptoms. MSKCC studied 55 patients with unresectable liposarcomas and found increased survival (26 versus 4 months) in patients receiving partial resection compared to biopsy alone (41). The majority of benefit for partial resection was seen in patients with primary disease, and patients undergoing partial resection of local recurrence showed significantly decreased survival compared to after partial resection of primary disease (17 versus 46 months). Several studies have shown that approximately 75% of patients report symptomatic improvement after palliative surgery (41–43). This improvement, however, can be short-lived. One study showed 71% of patients had symptomatic improvement at 30 days but this fell to 54% by 100 days (43). Also in this study, palliative operations had a morbidity rate of 29% and mortality rate of 12%. Thus selection of patients and surgical judgment is critical as these operations are often extensive and may not provide prolonged alleviation of symptoms.

RADIATION THERAPY

There is a lack of high quality studies to define the role of radiation in the management of patients with RPS. Numerous retrospective and non-randomized prospective studies exist, with some finding an association between adjuvant radiation and local disease control (44), while others have shown a delay in local recurrence but ultimately no difference in rate of local control (45). This controversy is reflected in clinical practice, with some institutions reporting very low (<15%) use of radiation (46), while in others, 70% of patients receive radiation (32).

Only one prospective randomized trial of radiation has been published (47), in which 35 patients with RPS were randomized to receive either 20 Gy of intra-operative radiation (IORT) with 35–40 Gy of postoperative external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) or 50–55 Gy of post-operative EBRT. Median survival was not significantly different between the groups (45 months for IORT vs. 52 months for EBRT only), but local recurrence was significantly lower in the group receiving IORT (40% vs 80%). Patients in both arms of the trial experienced very high rate of toxicity. Disabling radiation enteritis occurred in 50% of the EBRT only group compared to 13% in the IORT group. On the other hand, the IORT group had increased rates of peripheral neuropathy (60% vs 5%).

Currently, most radiation oncologists with expertise in treating RPS prefer delivering EBRT pre-operatively rather than post-operatively (48). Pre-operative radiation therapy has several potential advantages: (1) the target tumor volume can be clearly delineated; (2) adjacent normal tissue (especially bowel) is displaced out of the treatment field; (3) there is better oxygenation of the radiation field pre- vs post-operatively; (4) intra-operatively, there is a small risk of tumor seeding and peritoneal sarcomatosis (49,50). Retrospective and non-randomized prospective studies have demonstrated that p-pre-operative radiation is better tolerated than post-operative radiation, when administered to a comparable treatment volume (51). Recently, Bartlett et al. reviewed 696 RPS patients in the American College of Surgeons NSQIP database (52). After adjustment for cofounding variables, the 70 patients (10%) who underwent pre-operative radiation were not found to have increased in morbidity or mortality compared to those who did not receive radiation. A phase III multi-institutional prospective randomized trial of preoperative radiation and surgery versus surgery alone for RPS was attempted in the United States through the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG 9031), but failed due to lack of accrual. The failure of this trial has been attributed to institutional biases for or against the use of radiation, and a lack of consensus on the optimal neoadjuvant radiation regimen. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) is currently accruing a similar trial (“STRASS”; EORTC 62092).

The data is conflicting about combining pre-operative with intra-operative radiation. Gieschen et al treated 29 patients with RPS with preoperative radiation to a median dose of 45 Gy and patients then underwent complete gross resection (53). 10–20 Gy IORT was delivered to 16 of the 29 patients. Local control at 5 years was 83% for patients who received both preoperative radiation and IOERT and 61% for those who received only preoperative radiation. Similar results in local control for RPS treated with EBRT and IOERT have been reported from the Mayo Clinic (54). However, no benefit to IORT could be found on analysis of two prospective, non-randomized trials that utilized preoperative radiation therapy as well as either IORT or brachytherapy (55). Of the 72 patients with intermediate- or high-grade tumors in the study, pre-operative therapy was completed in 57 patients; 54 patients went on to complete surgical resection. Of these, 22 patients received IORT, 12 post-operative brachytherapy, and 20 no additional boost. During this trial, use of brachytherapy to the upper abdomen was associated with grade 3 toxicity in nearly 40% of patients including two deaths and one life-threatening illness (56). In this study, the 5-year local recurrence-free, disease-free, and overall survival rates were 60%, 46%, and 61%, respectively. There was no association between disease-free survival and use of either IORT or brachytherapy.

Newer radiation therapy technologies have been applied to patients with RPS in order to decrease treatment-related morbidities. These technologies, including 3D conformal, intensity-modulated (IMRT) and proton-beam (PBRT) (57–60), can more precisely target the tumor and critical margins, and thereby decrease delivery of radiation to adjacent organs and structures. Short-term follow-up of small series of patients treated with these technologies has established their safety and promising efficacy in decreasing LR (19,54,61,62). For example, dose escalation to presumed high-risk tumor margins using IMRT could help reduce LR (62,63).

In summary, use of radiation therapy for RPS is sharply polarized. Those against it cite the absence of data demonstrating a survival benefit and its considerable toxicities, especially in the post-operative setting. On the other hand, advocates argue that radiation improves local control, which is the major determinant of outcome in RPS, and the lower morbidity rates associated with pre-operative radiation. There is, however, widespread agreement that pre-operative radiation is favored over post-operative radiation, and that radiation has a greater role in the management of recurrent disease.

CHEMOTHERAPY AND CHEMORADIATION

The efficacy of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas is largely based on randomized trials and meta-analyses where the primary sites were predominantly the extremity and trunk. Typically, patients with high-risk lesions (higher grade, larger size [typically >5cm]) were eligible. Several early prospective studies using doxorubicin-based chemotherapy failed to show an improvement in disease-free or overall survival in patients receiving postoperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone (64). A meta-analysis of 14 randomized trials of doxorubicin-based adjuvant chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy in STS was performed in 1997 (65). The adjuvant chemotherapy group had a statistically significant higher rate of local recurrence-free survival (81% vs. 75%, P = .016), distant recurrence-free survival (70% vs. 60%, P = .003), and overall recurrence-free survival (55% vs. 45%, P = .001). However, overall survival differed only by 4% (54% vs. 50%), and this difference did not attain statistical significance. Four subsequent randomized trials examined the benefit of anthracycline and ifosfamide-based combination adjuvant chemotherapy in extremity STS, and two of them suggested a possible survival benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy. An updated meta-analysis was published in 2008 of 18 randomized trials of 1953 patients (66). Similar results were found in terms of local recurrence and distant recurrence compared to the earlier meta-analysis, but in this analysis the combination of doxorubicin and ifosfamide was found to increase overall survival from 59% to 70%. Most recently, however, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) reported final results of a trial that randomized 351 patients to adjuvant doxorubicin and ifosfamide or no chemotherapy (67). Extremity sarcomas comprised 80% of patients accrued, with the actual number of retroperitoneal sarcomas not stated. Histologically, one-third of patients had either liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma (the predominant histologies in the retroperitoneum), but the proportion of well- and de-differentiated liposarcomas was not detailed. Overall, no differences were found in overall or recurrence-free survival at a median follow-up of 8 years. So, the utility of adjuvant chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas remains unclear. The applicability of this data specifically to retroperitoneal sarcomas also remains uncertain. On the one hand, most RPS are high grade and larger than 5cm. On the other hand, very few patients with RPS were included in the above RCTs, and sarcomas of the retroperitoneum may have a unique biology and response to treatment compared to sarcomas at other sites.

Unfortunately, there are no randomized trials of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy for RPS. Meric et al examined whether pre-operative chemotherapy could decrease the extent of resection in 65 patients with STS, 23 of whom had RPS (68). In the RPS subgroup, no patients had a response significant enough to allow organ salvage, with one patient progressing to unresectability while on chemotherapy. Donahue et al treated 55 patients with high grade RPS with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (69). Before 1990, patients received doxorubicin-based therapy; after 1990, patients with leiomyosarcomas received dacarbazine or gemcitabine/docetaxel-based therapy while patients with other histologies received ifosfamide-based therapy. One-quarter of patients had >95% tumor necrosis. After a median follow-up of 68 months, 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) was 47%, not significantly different than the 37% survival predicted by the MSKCC nomogram. However, in the 25% of patients who demonstrated a pathologic response, 5-year DSS was 83%. Thus, chemotherapy is controversial for RPS given its heterogeneous nature and the lack of compelling clinical trials data. It is now well accepted that histologic subtype significantly governs outcome in RPS, and different histologies (e.g. leiomyosarcoma) are known to carry higher risk of metastasis.

Newer agents and strategies are currently being investigated. Targeted agents, especially inhibitors of CDK4 and MDM2 for well- and de-differentiated liposarcomas, have recently been developed and show promise in early clinical trials (70).

The addition of radiation-sensitizing agents to pre-operative radiation has also been studied. A phase I trial from MDACC reported 35 patients with RPS treated with neoadjuvant doxorubicin and concurrent dose-escalation EBRT with or without IOERT (71). This neoadjuvant treatment was completed in 89% of patients. In the group receiving 50 Gy radiation (6 patients), significant nausea and neutropenia occurred in two patients each. Six (17%) patients progressed to unresectability while on the neoadjuvant protocol. Of the remaining patients who underwent resection, two had 50–90% tumor necrosis and three had 10–49% necrosis. Gronchi et al treated 83 patients with upfront resectable RPS pre-operatively with high-dose long-infusion ifosfamide and 3D conformal radiation (72). One-third of patients could not complete the phase I/II protocol. A RECIST partial response was observed in 7 patients (8%). Four patients progressed to unresectability. Pathologic response rates were not reported. Yoon et al combined pre-operative radiation with bevacizumab to treat 20 patients with intermediate or high grade STS (four of whom had RPS) (73). There were no grade 4 toxicities, 20% had grade 3 toxicities. Nine of 20 (45%) tumors had ≥80% necrosis, which was more than twice the historical rate seen with radiation alone.

In summary, use of chemotherapy (either adjuvant or neoadjuvant) has not been conclusively shown to provide significant downsizing or survival benefit in RPS. Further studies, particularly in the neoadjuvant setting, are constrained by the small but defined rate of progression to unresectability and associated toxicities. Progress will likely depend on targeted rather than cytotoxic therapies.

FOLLOW-UP

The median time to local recurrence for patients with RPS is 22 months (74). Post-operatively, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend physical exam and CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis every 3–6 months for two years, then annually. Chest CT should be added for those patients with high grade tumors (75). There remains a risk of delayed recurrence (five years after resection) particularly for low grade tumors. Therefore, our practice is to follow patients with low grade tumors indefinitely, but to stop follow-up of high-grade tumors after five years.

LOCAL RECURRENCE

LR is the primary mode of recurrence after complete resection of retroperitoneal sarcoma, and may occur late: up to 40% of patients will recur beyond 5 years (44). Synchronous local and distant recurrence occurs in about 20%, and is associated with poor prognosis (median survival 12 months) (42). With close post-operative follow-up, most recurrences are detected at an asymptomatic stage by radiologic surveillance. Symptomatic patients will present with abdominal pain (52%), abdominal fullness (18%), and abdominal cramping/nausea (18%) (42).

The most significant prognostic variable following local recurrence is resectability of the recurrent disease (3). Median survival is 60 months in resected patients, compared with just 20 months for unresected patients. Approximately half of patients will have unresectable disease, defined as peritoneal implants (sarcomatosis) or extensive vascular involvement. Other prognostic factors include tumor grade, multifocality and tumor growth rate (42,76).

Surgery for local recurrence

Resection of locally recurrent RPS is generally significantly more difficult than resection for primary disease, and the risk of another local recurrence is even higher than that for primary disease. Each subsequent recurrence is associated with lower rate of successful re-resection and shorter disease-free interval (3,42,76,77). In studies specifically addressing resection of locally recurrent RPS, rates of complete resection ranged between 44–60% and complete resection was significantly associated with increased survival (40,42,74). Reported 5-year overall survival after complete resection are between 30–46% compared to 27% or less in unresectable patients. Park et al. examined 105 patients who had local recurrence of RP sarcoma (76). After a median follow-up of 65 months, local recurrence size, local recurrence growth rate, histologic subtype, and grade with independent predictors of disease-specific survival. Local recurrence growth rate for the first local recurrence was defined as the tumor size divided by the time from primary resection to local recurrence. Patients with a local recurrence growth rate <1cm per month had improved survival following resection of the local recurrence.

There are limited data to guide decision-making for locally-recurrent disease. For patients with resectable disease where further increase in tumor size would render the disease unresectable, an operation is typically indicated. On the other hand, a strategy of close observation may be considered in those with aggressive biology (as demonstrated by a short recurrence-free interval and multiple prior resections), in high-risk patients with significant co-morbidities, or in those with low grade, slowly-progressive biology. Employing such a strategy allows the surgeon to select out those patients unlikely to benefit from attempted resection (78). Patients with recurrent high grade tumors should be encourage to enroll in trials of investigational chemotherapy. The multifocal nature of recurrent disease in most patients limits use of radiation therapy.

SUMMARY

Management of RPS present complex challenges. Referral to a high volume sarcoma center is recommended. Complete gross resection at initial presentation is the best chance for cure, but controversy continues as to how this can be best achieved. There is a long-term risk of local recurrence, which is best treated with repeat resection if feasible. The role of pre-operative radiation is controversial, but the subject of an ongoing randomized trial in Europe. As our understanding of the genetic alterations grows, so too will the development and use of targeted systemic agents.

Acknowledgments

NIH funded. 1 R01 CA158301.

Footnotes

No Disclosures

Contributor Information

Marcus C. B. Tan, Email: mctan@health.southalabama.edu, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, University of South Alabama & Mitchell Cancer Institute, 2451 Fillingim St, Mobile, AL 36617

Sam S. Yoon, Email: yoons@mskcc.org, Associate Attending, Gastric and Mixed Tumor Service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, H1209, New York, NY 10065, Phone: 212739-7436, Fax: 212-639-7460

References

- 1.Siegel R. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonvalot S, Rivoire M, Castaing M, Stoeckle E, Le Cesne A, Blay JY, Laplanche A. Primary retroperitoneal sarcomas: a multivariate analysis of surgical factors associated with local control. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jan 1;27(1):31–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis JJ, Leung D, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Retroperitoneal soft-tissue sarcoma: analysis of 500 patients treated and followed at a single institution. Ann Surg. 1998 Sep;228(3):355–65. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toulmonde M, Bonvalot S, Méeus P, Stoeckle E, Riou O, Isambert N, Bompas E, Jafari M, Delcambre-Lair C, Saada E, Le Cesne A, Le Péchoux C, Blay JY, Piperno-Neumann S, Chevreau C, Bay JO, Brouste V, Terrier P, Ranchère-Vince D, Neuville A, Italiano A, Ray-Coquard I, Penel N, Lecesne A. Retroperitoneal sarcomas: patterns of care at diagnosis, prognostic factors and focus on main histological subtypes: a multicenter analysis of the French Sarcoma Group. Ann Oncol. 2014 Mar;25(3):735–42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gronchi A, Miceli R, Colombo C, Stacchiotti S, Collini P, Mariani L, Sangalli C, Radaelli S, Sanfilippo R, Fiore M, Casali PG. Frontline extended surgery is associated with improved survival in retroperitoneal low- to intermediate-grade soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Oncol. 2012 Apr;23(4):1067–73. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gronchi A, Miceli R, Shurell E, Eilber FC, Eilber FR, Anaya Da, Kattan MW, Honoré C, Lev DC, Colombo C, Bonvalot S, Mariani L, Pollock RE. Outcome prediction in primary resected retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma: histology-specific overall survival and disease-free survival nomograms built on major sarcoma center data sets. J Clin Oncol. 2013 May 1;31(13):1649–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crago AM, Singer S. Clinical and molecular approaches to well differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011 Jul;23(4):373–8. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32834796e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalal KM, Kattan MW, Antonescu CR, Brennan MF, Singer S. Subtype specific prognostic nomogram for patients with primary liposarcoma of the retroperitoneum, extremity, or trunk. Ann Surg. 2006 Sep;244(3):381–91. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234795.98607.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer S, Antonescu CR, Riedel E, Brennan MF. Histologic subtype and margin of resection predict pattern of recurrence and survival for retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Ann Surg. 2003 Sep;238(3):358–70. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086542.11899.38. discussion 370–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu-Emerson C, Plotkin SR. The Neurofibromatoses. Part 1: NF1. Rev Neurol Dis. 2009 Jan;6(2):E47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, Ferrone CR, Hussain M, Lewis JJ, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Clinicopathologic Correlates of Solitary Fibrous Tumors. Cancer. 2002;94:1057–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zöller ME, Rembeck B, Odén A, Samuelsson M, Angervall L. Malignant and benign tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 in a defined Swedish population. Cancer. 1997 Jun 1;79(11):2125–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson E, Neugut AI, Wylie P. Clinical aspects of postirradiation sarcomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988 Apr 20;80(4):233–40. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.4.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tzeng C-WD, Smith JK, Heslin MJ. Soft tissue sarcoma: preoperative and postoperative imaging for staging. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007 Apr;16(2):389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig WD, Fanburg-Smith JC, Henry LR, Guerrero R, Barton JH. Fat-containing lesions of the retroperitoneum: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 29(1):261–90. doi: 10.1148/rg.291085203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonvalot S, Raut CP, Pollock RE, Rutkowski P, Strauss DC, Hayes AJ, Van Coevorden F, Fiore M, Stoeckle E, Hohenberger P, Gronchi A. Technical considerations in surgery for retroperitoneal sarcomas: position paper from E-Surge, a master class in sarcoma surgery, and EORTC-STBSG. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 Sep;19(9):2981–91. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lahat G, Madewell JE, Anaya DA, Qiao W, Tuvin D, Benjamin RS, Lev DC, Pollock RE. Computed tomography scan-driven selection of treatment for retroperitoneal liposarcoma histologic subtypes. Cancer. 2009 Mar 1;115(5):1081–90. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberge D, Vakilian S, Alabed YZ, Turcotte RE, Freeman CR, Hickeson M. FDG PET/CT in Initial Staging of Adult Soft-Tissue Sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2012 Jan;2012:960194. doi: 10.1155/2012/960194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon SS, Chen Y-L, Kirsch DG, Maduekwe UN, Rosenberg AE, Nielsen GP, Sahani DV, Choy E, Harmon DC, DeLaney TF. Proton-beam, intensity-modulated, and/or intraoperative electron radiation therapy combined with aggressive anterior surgical resection for retroperitoneal sarcomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Jun;17(6):1515–29. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0935-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heslin MJ, Lewis JJ, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Core needle biopsy for diagnosis of extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4(5):425–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02305557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Presant CA, Russell WO, Alexander RW, Fu YS. Soft-tissue and bone sarcoma histopathology peer review: the frequency of disagreement in diagnosis and the need for second pathology opinions. The Southeastern Cancer Study Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 1986 Nov;4(11):1658–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.11.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiraki M, Enterline HT, Brooks JJ, Cooper NS, Hirschl S, Roth JA, Rao UN, Enzinger FM, Amato DA, Borden EC. Pathologic analysis of advanced adult soft tissue sarcomas, bone sarcomas, and mesotheliomas. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) experience. Cancer. 1989 Jul 15;64(2):484–90. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890715)64:2<484::aid-cncr2820640223>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A III, editors. AJCC Staging Manual. 7. New York: Springer US; 2010. Soft tissue sarcoma; pp. 291–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abbott AM, Habermann EB, Parsons HM, Tuttle T, Al-Refaie W. Prognosis for primary retroperitoneal sarcoma survivors: a conditional survival analysis. Cancer. 2012 Jul 1;118(13):3321–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anaya D, Lahat G, Wang X, Xiao L, Tuvin D, Pisters PW, Lev DC, Pollock RE. Establishing prognosis in retroperitoneal sarcoma: a new histology-based paradigm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009 Mar;16(3):667–75. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nathan H, Raut CP, Thornton K, Herman JM, Ahuja N, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Pawlik TM. Predictors of survival after resection of retroperitoneal sarcoma: a population-based analysis and critical appraisal of the AJCC staging system. Ann Surg. 2009 Dec;250(6):970–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b25183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maki RG, Moraco N, Antonescu CR, Hameed M, Pinkhasik A, Singer S, Brennan MF. Toward better soft tissue sarcoma staging: building on american joint committee on cancer staging systems versions 6 and 7. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013 Oct;20(11):3377–83. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3052-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anaya D, Lahat G, Wang X, Xiao L, Pisters PW, Cormier JN, Hunt KK, Feig BW, Lev DC, Pollock RE. Postoperative nomogram for survival of patients with retroperitoneal sarcoma treated with curative intent. Ann Oncol. 2010 Feb;21(2):397–402. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ardoino I, Miceli R, Berselli M, Mariani L, Biganzoli E, Fiore M, Collini P, Stacchiotti S, Casali PG, Gronchi A. Histology-specific nomogram for primary retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2010 May 15;116(10):2429–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollenbeck ST, Grobmyer SR, Kent KC, Brennan MF. Surgical treatment and outcomes of patients with primary inferior vena cava leiomyosarcoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2003 Oct;197(4):575–9. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kieffer E, Alaoui M, Piette J-C, Cacoub P, Chiche L. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: experience in 22 cases. Ann Surg. 2006 Aug;244(2):289–95. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000229964.71743.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gronchi A, Lo Vullo S, Fiore M, Mussi C, Stacchiotti S, Collini P, Lozza L, Pennacchioli E, Mariani L, Casali PG. Aggressive surgical policies in a retrospectively reviewed single-institution case series of retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jan 1;27(1):24–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.8871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonvalot S, Miceli R, Berselli M, Causeret S, Colombo C, Mariani L, Bouzaiene H, Le Péchoux C, Casali PG, Le Cesne A, Fiore M, Gronchi A. Aggressive surgery in retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma carried out at high-volume centers is safe and is associated with improved local control. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Jun;17(6):1507–14. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pisters PWT. Resection of some -- but not all -- clinically uninvolved adjacent viscera as part of surgery for retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jan 1;27(1):6–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, Jensen MH, Farnell MB, Smyrk TC, Zhang L. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas: study of 9 cases and review of literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010 Dec;34(12):1849–56. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f97727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassan I, Park SZ, Donohue JH, Nagorney DM, Kay Pa, Nasciemento AG, Schleck CD, Ilstrup DM. Operative management of primary retroperitoneal sarcomas: a reappraisal of an institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2004 Feb;239(2):244–50. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000108670.31446.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Dalen T, Plooij JM, van Coevorden F, van Geel aN, Hoekstra HJ, Albus-Lutter C, Slootweg PJ, Hennipman a Dutch Soft Tissue Sarcoma Group. Long-term prognosis of primary retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007 Mar;33(2):234–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierie J-PEN, Betensky Ra, Choudry U, Willett CG, Souba WW, Ott MJ. Outcomes in a series of 103 retroperitoneal sarcomas. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006 Dec;32(10):1235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiappa A, Zbar AP, Ed F, Bertani E. Primary and Recurrent Retroperitoneal Soft Tissue Sarcoma: Prognostic Factors Affecting Survival. 2006;(October 2005):456–63. doi: 10.1002/jso.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaques DP, Coit DG, Hajdu SI, Brennan MF. Management of primary and recurrent soft-tissue sarcoma of the retroperitoneum. Ann Surg. 1990 Jul;212(1):51–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199007000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibata D, Lewis JJ, Leung DH, Brennan MF. Is there a role for incomplete resection in the management of retroperitoneal liposarcomas? J Am Coll Surg. 2001 Oct;193(4):373–9. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grobmyer SR, Wilson JP, Apel B, Knapik J, Bell WC, Kim T, Bland KI, Copeland EM, Hochwald SN, Heslin MJ. Recurrent retroperitoneal sarcoma: impact of biology and therapy on outcomes. J Am Coll Surg Elsevier Inc. 2010 May;210(5):602–8. 608–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeh JJ, Singer S, Brennan MF, Jaques DP. Effectiveness of palliative procedures for intra-abdominal sarcomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005 Dec;12(12):1084–9. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heslin MJ, Lewis JJ, Nadler E, Newman E, Woodruff JM, Casper ES, Leung D, Brennan MF. Prognostic factors associated with long-term survival for retroperitoneal sarcoma: implications for management. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Aug;15(8):2832–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.8.2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Catton CN, O’Sullivan B, Kotwall C, Cummings B, Hao Y, Fornasier V. Outcome and prognosis in retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994 Jul 30;29(5):1005–10. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keung EZ, Hornick JL, Bertagnolli MM, Baldini EH, Raut CP. Predictors of outcomes in patients with primary retroperitoneal dedifferentiated liposarcoma undergoing surgery. J Am Coll Surg Elsevier Inc. 2014 Feb;218(2):206–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sindelar WF, Kinsella TJ, Chen PW, DeLaney TF, Tepper JE, Rosenberg SA, Glatstein E. Intraoperative radiotherapy in retroperitoneal sarcomas. Final results of a prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Arch Surg. 1993 Apr;128(4):402–10. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420160040005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van De Voorde L, Delrue L, van Eijkeren M, De Meerleer G. Radiotherapy and surgery-an indispensable duo in the treatment of retroperitoneal sarcoma. Cancer. 2011 Oct 1;117(19):4355–64. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herman K, Kusy T. Retroperitoneal sarcoma--the continued challenge for surgery and oncology. Surg Oncol. 1999;7(1–2):77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(99)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pawlik TM, Ahuja N, Herman JM. The role of radiation in retroperitoneal sarcomas: a surgical perspective. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007 Jul;19(4):359–66. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328122d757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pisters PWT. Retroperitoneal sarcomas--an SOS to colleagues in Europe. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007 Jun;14(6):1787–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9382-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bartlett EK, Roses RE, Meise C, Fraker DL, Kelz RR, Karakousis GC. Preoperative radiation for retroperitoneal sarcoma is not associated with increased early postoperative morbidity. J Surg Oncol. 2014 May;109(6):606–11. doi: 10.1002/jso.23534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gieschen HL, Spiro IJ, Suit HD, Ott MJ, Rattner DW, Ancukiewicz M, Willett CG. Long-term results of intraoperative electron beam radiotherapy for primary and recurrent retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001 May 1;50(1):127–31. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pezner RD, Liu A, Han C, Chen Y-J, Schultheiss TE, Wong JYC. Dosimetric comparison of helical tomotherapy treatment and step-and-shoot intensity-modulated radiotherapy of retroperitoneal sarcoma. Radiother Oncol. 2006 Oct;81(1):81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pawlik TM, Pisters PWT, Mikula L, Feig BW, Hunt KK, Cormier JN, Ballo MT, Catton CN, Jones JJ, O’Sullivan B, Pollock RE, Swallow CJ. Long-term results of two prospective trials of preoperative external beam radiotherapy for localized intermediate- or high-grade retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 Apr;13(4):508–17. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones JJ, Catton CN, O’Sullivan B, Couture J, Heisler RL, Kandel RA, Swallow CJ. Initial results of a trial of preoperative external-beam radiation therapy and postoperative brachytherapy for retroperitoneal sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002 May;9(4):346–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02573869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lichter AS, Ten Haken RK. Three-dimensional treatment planning and conformal radiation dose delivery. Important Adv Oncol. 1995 Jan;:95–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thorwarth D, Geets X, Paiusco M. Physical radiotherapy treatment planning based on functional PET/CT data. Radiother Oncol. 2010 Sep;96(3):317–24. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teh BS, Woo SY, Butler EB. Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT): a new promising technology in radiation oncology. Oncologist. 1999 Jan;4(6):433–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacDonald SM, DeLaney TF, Loeffler JS. Proton beam radiation therapy. Cancer Invest. 2006 Mar;24(2):199–208. doi: 10.1080/07357900500524751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bossi A, De Wever I, Van Limbergen E, Vanstraelen B. Intensity modulated radiation-therapy for preoperative posterior abdominal wall irradiation of retroperitoneal liposarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007 Jan 1;67(1):164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tzeng C-WD, Fiveash JB, Popple RA, Arnoletti JP, Russo SM, Urist MM, Bland KI, Heslin MJ. Preoperative radiation therapy with selective dose escalation to the margin at risk for retroperitoneal sarcoma. Cancer. 2006 Jul 15;107(2):371–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McBride SM, Raut CP, Lapidus M, Devlin PM, Marcus KJ, Bertagnolli M, George S, Baldini EH. Locoregional recurrence after preoperative radiation therapy for retroperitoneal sarcoma: adverse impact of multifocal disease and potential implications of dose escalation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013 Jul;20(7):2140–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2868-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Antman KH. Adjuvant therapy of sarcomas of soft tissue. Semin Oncol. 1997 Oct;24(5):556–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adjuvant chemotherapy for localised resectable soft-tissue sarcoma of adults: meta-analysis of individual data. Sarcoma Meta-analysis Collaboration. Lancet. 1997 Dec 6;350(9092):1647–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pervaiz N, Colterjohn N, Farrokhyar F, Tozer R, Figueredo A, Ghert M. A systematic meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy for localized resectable soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2008 Aug 1;113(3):573–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Woll PJ, Reichardt P, Le Cesne A, Bonvalot S, Azzarelli A, Hoekstra HJ, Leahy M, Van Coevorden F, Verweij J, Hogendoorn PCW, Ouali M, Marreaud S, Bramwell VHC, Hohenberger P. Adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and lenograstim for resected soft-tissue sarcoma (EORTC 62931): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol Elsevier Ltd. 2012 Oct;13(10):1045–54. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meric F, Hess KR, Varma DGK, Hunt KK, Pisters PWT, Milas KM, Patel SR, Benjamin RS, Plager C, Papadopoulos NEJ, Burgess Ma, Pollock RE, Feig BW. Radiographic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a predictor of local control and survival in soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 2002 Sep 1;95(5):1120–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Donahue TR, Kattan MW, Nelson SD, Tap WD, Eilber FCFR. Evaluation of neoadjuvant therapy and histopathologic response in primary, high-grade retroperitoneal sarcomas using the sarcoma nomogram. Cancer. 2010 Aug 15;116(16):3883–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dickson Ma, Tap WD, Keohan ML, D’Angelo SP, Gounder MM, Antonescu CR, Landa J, Qin L-X, Rathbone DD, Condy MM, Ustoyev Y, Crago AM, Singer S, Schwartz GK. Phase II trial of the CDK4 inhibitor PD0332991 in patients with advanced CDK4-amplified well-differentiated or dedifferentiated liposarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jun 1;31(16):2024–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.5476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pisters PWT, Ballo MT, Fenstermacher MJ, Feig BW, Hunt KK, Raymond KA, Burgess MA, Zagars GK, Pollock RE, Benjamin RS, Patel SR. Phase I trial of preoperative concurrent doxorubicin and radiation therapy, surgical resection, and intraoperative electron-beam radiation therapy for patients with localized retroperitoneal sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Aug 15;21(16):3092–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gronchi A, De Paoli A, Dani C, Merlo DF, Quagliuolo V, Grignani G, Bertola G, Navarria P, Sangalli C, Buonadonna A, De Sanctis R, Sanfilippo R, Dei Tos AP, Stacchiotti S, Giorello L, Fiore M, Bruzzi P, Casali PG. Preoperative chemo-radiation therapy for localised retroperitoneal sarcoma: a phase I–II study from the Italian Sarcoma Group. Eur J Cancer Elsevier Ltd. 2014 Mar;50(4):784–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoon SS, Duda DG, Karl DL, Kim T-M, Kambadakone AR, Chen Y-L, Rothrock C, Rosenberg AE, Nielsen GP, Kirsch DG, Choy E, Harmon DC, Hornicek FJ, Dreyfuss J, Ancukiewicz M, Sahani DV, Park PJ, Jain RK, Delaney TF. Phase II study of neoadjuvant bevacizumab and radiotherapy for resectable soft tissue sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 Nov 15;81(4):1081–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Dalen T, Hoekstra HJ, van Geel aN, van Coevorden F, Albus-Lutter C, Slootweg PJ, Hennipman a. Locoregional recurrence of retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma: second chance of cure for selected patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001 Sep;27(6):564–8. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2001.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Casper ES, Conrad EU, Delaney TF, Ganjoo KN, George S, Gonzalez RJ, Heslin MJ, Kane JM, Mayerson J, McGarry SV, Meyer C, O’Donnell RJ, Pappo AS, Paz IB, Pfeifer JD, Riedel RF, Schuetze S, Schupak KD, Schwartz HS, Van Tine BA, Wayne JD, Bergman MA, Sundar H. Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014 Apr;12(4):473–83. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park JO, Qin L-X, Prete FP, Antonescu C, Brennan MF, Singer S. Predicting Outcome by Growth Rate of Locally Recurrent Retroperitoneal Liposarcoma. Ann Surg. 2009 Dec;250(6):977–82. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181b2468b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kattan MW, Leung DHY, Brennan MF. Postoperative nomogram for 12-year sarcoma-specific death. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Feb 1;20(3):791–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gyorki DE, Brennan MF. Management of recurrent retroperitoneal sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014 Jan;109(1):53–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.23463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]