More people have died after contracting a virulent infection that has broken out in hospitals in Montréal and Calgary than were killed by SARS — yet neither public health nor hospital officials warned the public until CMAJ broke the news.

For 18 months, at least 12 hospitals in Montréal have been battling an outbreak of Clostridium difficile, an organism that is naturally resistant to most broad-spectrum antibiotics used on hospital wards. At 6 Montréal hospitals, more than 1400 patients tested positive for the infection in 2003, according to a chart review by Dr. Sandra Dial, an intensive care physician.

CMAJ's investigation has elicited reports of the deaths of at least 83 patients in several Montréal institutions and in Calgary, all of whom contracted the infection in 2003 or early 2004.

Last August, Hôpital du Sacre-Coeur de Montréal closed its ICU completely for 1 day and partly for 3 weeks, because staff were overwhelmed by the number of C. difficile patients, says Dr. Gilbert Pichette, infection control officer.

“We have had deaths, we have had colectomies. We are in the process of gathering the statistics,” he says.

The outbreaks are not yet under control in Montréal or in Calgary, where a less virulent strain of the same organism has apparently resurfaced after an outbreak in 2000–2001.

“I believe that we have a new [strain] that seems to be quite virulent,” says Dr. Vivian Loo, director of infection prevention and control at the McGill University Health Centre. “It's a huge challenge.”

The infection occurs in some patients after they've taken antibiotics. It is thought that antibiotics reduce the normal bacterial population of the small intestine, allowing the organism to thrive. Once established in the intestine, the organism produces a toxin (cytotoxin B) that damages the colon. Patients suffer mild or severe diarrhea, which can be accompanied by hemorrhage if further infections have damaged the colon. In some cases, a total colectomy may be necessary.

The organism forms spores that can survive for long periods outside the body and are resistant to common hospital disinfectants. C. difficile is spread through hand-to-hand contact, often by patients sharing rooms and bathrooms, or inadvertently by staff caring for multiple patients.

The precise number of deaths and colectomies that occurred after patients contracted C. difficile during the Montréal outbreak is unknown because most hospitals CMAJ contacted would not provide statistics.

But at Montréal's Royal Victoria Hospital alone, 51 patients died last year after contracting C. difficile, according to Dial's research. At least 30 of those deaths were directly attributable to the infection, she says — Loo says it's half that. She contends Dial is counting the deaths of patients who tested positive for C. difficile but also developed other problems. “There's a distinction whether you died with it [C. difficile] rather than from it,” says Loo.

Another 16 patients with C. difficile, admitted to the ICU at Jewish General Hospital between January 2003 and March 2004, have also died, Dial's records indicate. There were also 2 deaths at the Montréal Chest Institute attributable to C. difficile, she says.

At the Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont, 3–5 patients are dying per month with C. difficile, says Dr. Karl Weiss, the hospital's infectious disease specialist and microbiologist. That amounts to 9–15 patients this year alone. Those figures bring the total number of deaths in Montreal that CMAJ is aware of to at least 79, including that of a patient who died at St. Luke's Hospital. Another 4 patients died in Calgary in the last 18 months.

By comparison, in all of Canada 44 people died from SARS during last year's outbreak.

“Certainly it's much more serious than SARS,” says Dr. Bruce Brown, the director of professional services at St. Mary's Hospital in Montréal.

“It's almost a pandemic now, because it's been going on for so long,” says Dr. Todd McConnell, physician-in-chief at St. Mary's. Other countries, including the US and UK, have also experienced major outbreaks. “It's a huge concern to the medical community.”

“Twenty years ago this was a rare complication of antibiotics; now it's so common that when we have a patient in the hospital who develops diarrhea, our first thought is that it's this infection,” he says.

Although hospitals outside of Quebec and Alberta have not yet reported the same extent or severity of C. difficile, infectious disease specialists in Toronto and elsewhere are watching the organism closely.

“Listening to stories from Montréal is, frankly, scary. It could happen in Toronto — tomorrow,” says Dr. Allison McGeer, an infectious disease specialist at Toronto's Mount Sinai Hospital.

Patients have usually been admitted for other illnesses when they contract the infection in hospital and are often elderly or immunocompromised. But in at least 2 cases, otherwise healthy patients in hospital for joint surgery contracted C. difficile and died, Dial told CMAJ.

One was a 50-year-old healthy man who entered the hospital for elective hip surgery and contracted C. difficile. He was dead 4 days later.

Dial has published research findings (see page 33) indicating that treatment with proton pump inhibitors — a popular class of acid suppressants used to treat peptic ulcers and esophageal reflux disease — is a risk factor for C. difficile infection.

“I've been an intensivist for 10 years and I didn't see patients require ICU [admission] because of C. diff ever before, but now it's practically routine,” says Dial, who is based at the Montréal Chest Institute.

After seeing the high rates in ICUs at several Montréal hospitals where she works, Dial began reviewing hundreds of patients' charts. According to her figures, 466 patients were diagnosed with C. difficile at the Royal Victoria Hospital in 2003. Among those patients there were 51 deaths, 30 of which were directly attributable to C. difficile, she says.

At the Jewish General Hospital, there were 426 positive lab tests for toxin-positive C. difficile in 2003; at least 10 of those patients died in the ICU last year alone. Another 14 people with C. difficile were admitted to the ICU in the Jewish General in the first 3 months of this year; 6 died.

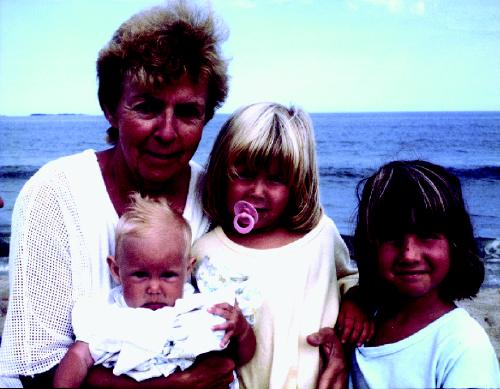

Isabelle Rocher's mother, Suzanne Cloutier Rocher, is among the C. difficile victims. Cloutier Rocher, who was 80, had emergency abdominal surgery at St. Luke's Hospital and was admitted to a floor that was “full of people with C. difficile,” her daughter says.

Rocher, who is a nurse at another Montréal hospital, watched her previously healthy, independent mother became severely ill. She died 5 weeks later.

“She should not have died. She was an elderly person but she had many years to go,” Rocher says. “If I had known that this hospital [had a C. difficile problem], I might have chosen another place.”

Patients are not the only ones contracting the infection; at least one doctor, a volunteer and some health care workers have also been admitted to hospital with C. difficile, Brown says of St. Mary's experience.

Despite the outbreak, hospitals administrators failed to warn the public and patients. The McGill University Health Centre held a media conference after this article was released online, saying they had 36 deaths.

The head of the infectious disease unit at Montréal's public health authority is just beginning to investigate the outbreak. Some doctors say they attempted to involve the agency in December.

“We really have only very preliminary data that we've been able to collect through hospital discharge [reports],” says Dr. John Carsley. “We've asked all the hospitals in Montréal to send us their most recent data.”

C. difficile is not a reportable disease, in part because nosocomial infections are viewed as being confined to hospitals and hence as not posing a risk to the public (see page 22). Physicians and hospitals must report any severe or unusual outbreaks of infectious diseases, however.

But at the Lakeshore General Hospital on Montréal's West Island, where an outbreak has been occurring since November 2003, doctors are seeing patients from the community who have never been hospitalized at that facility testing positive for C. difficile, says Ramona Rodrigues, the hospital's infection control officer.

Patients in their 20s, 30s and 40s are “coming in with bloody diarrhea and diarrhea. We've had cases of deaths and colectomies.”

Until public health better understands the extent of the problem, Carsley says he does not have an opinion on whether the public should be informed. “Right now it's an institutional decision about what kind of information they give out about [infection] control and about the extent of the infection.”

But Dial believes the lack of a public statement is keeping patients from making the choice of delaying elective surgeries or choosing to be admitted to a hospital with lower infection rates.

The Montréal hospitals have formed a group, which Loo heads, to track the outbreak and share infection control strategies.

Some doctors are telling patients that they risk contracting this infection if they are prescribed antibiotics or are admitted on wards with outbreaks.

“No hospital in Montréal wants to be labelled as the C. diff hospital,” says McConnell.

Like many of the physicians who spoke to CMAJ, McConnell is torn about the ethics of failing to inform patients or the public about the additional risk this infection poses.

“We're having a debate in our own hospital now as to how transparent we have to be about this infection as a risk factor,” he says. “I think you have to say to people, ‘Look, there’s a possibility you're going to get diarrhea, and if you do get diarrhea, we need to know about it sooner rather than later.' If you can get to a patient earlier, you stand a better chance of treating them.”

At private hospital meetings, medical staff and administrators have been debating the need to inform patients versus the risk of a general panic. The Christmas infection control meeting at St. Mary's — normally a social gathering — was spent listening to Dr. Michael Libman, an authority on C. difficile, talk about ways to try to control it.

The majority of people who die after contracting C. difficile are already quite sick and would have died even without getting the infection, Libman says, so it's difficult to decide if someone died from C. difficile directly. While doctors such as Dial may have seen “spectacular” cases with bad outcomes, he rejects the comparison some doctors are making that this is a SARS-like problem.

“I think the outbreak is a serious problem, but generally is a concern within the hospitals to specific types of patients,” says Libman, an assistant professor at McGill University.

While Libman believes patients should be told that taking antibiotics can precipitate C. difficile and should be educated about the importance of hand-washing, he does not think a public warning is warranted.

“In any given day or month, things are going on in the hospital that affect the patient's risk,” he says.

Nevertheless, the Royal Victoria is developing a handout to alert patients, says Loo. And patients at the Lakeshore General Hospital receive handouts about the importance of hand-washing and infection control, while nurses have some information available to give patients about C. difficile, Rodrigues says.

Physicians at several Montréal hospitals have unsuccessfully urged their administrators to hold news conferences or issue statements.

Initially, hospitals CMAJ contacted were reluctant to release their caseload, death and colectomy statistics. It was only when one doctor came forward to provide some figures that other hospitals acknowledged the problem.

At the Hôpital Maisonneuve-Rosemont, the caseload of patients with C. difficile has climbed to 30 per 1000 patients admitted, up from 10 cases per 1000 admissions in 2002, says Weiss.

“We have a big problem in terms of infection control,” he says. “We are practising 21st century medicine in a 19th century environment.”

Hospitals built at the turn of the 20th century -— like many of those in Montréal — are not equipped with bedside handwashing stations. There are few private rooms with separate bathrooms to allow doctors and administrators to isolate infected patients.

From an infection-control perspective, says Weiss, “When you keep people in hospital you should have 1 patient per room. Period.”

In addition to the physical set ups of bathrooms and wards, hospitals are having difficulty eradicating C. difficile, in part, they say, because of budget cuts to housekeeping staff. At Lakeshore General, for example, there are no housekeeping staff available at night, Rodrigues says.

“This organism stays around,” says Dr. Ken Flegel, a professor of medicine at McGill University and senior physician at the Royal Victoria. “We're finding it days and weeks after we thought a room was thoroughly sterilized with bleach. You have to treat the whole [hospital] environment as contaminated.”

There is a problem in Calgary as well. Before 2000, physicians saw only 2–4 cases of C. difficile per 500 beds per month. Hospitals endured a major outbreak of C. difficile in 2000–2001, when they experienced about 1100 cases, a rate peaking at 18–22 new cases per 500 beds per month, says Dr. Tom Louie, medical director, infection prevention and control at the Calgary Health Region.

The organism that affected Calgary emerged from a strain resistant to a common antibiotic (clindamycin), and health authorities thought they had successfully beaten back the outbreak after restricting prescriptions of the drug. The C. difficile rates declined to near baseline by January 2002.

But since last fall, the incidence has been rising again, with 13–15 new cases per 500 beds per month, at all 3 adult care hospitals in Calgary, says Louie. Since 2001, 17 patients with C. difficile have required colectomies and 10 have died; 4 of the deaths occurred in the last 18 months.

“We're not sure what it is. We know it's not the same strain as before,” Louie says. — Laura Eggertson, with Barbara Sibbald, CMAJ

Figure. Previously healthy, 80-year-old Suzanne Cloutier Rocher died of C. difficile Photo by: Courtesy of Isabelle Rocher

Figure. Proper hand-washing is essential to controlling C. difficile. Photo by: Canapress

β See related articles pages 27, 33, 45, 47 and 51

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published at www.cmaj.ca on June 4, 2004. Revised on June 14, 2004.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.