Abstract

Purpose:

In-vivo dosimetry and beam range verification in proton therapy could play significant role in proton treatment validation and improvements. In-vivo beam range verification, in particular, could enable new treatment techniques one of which could be the use of anterior fields for prostate treatment instead of opposed lateral fields as in current practice. This paper reports validation study of an in-vivo range verification method which can reduce the range uncertainty to submillimeter levels and potentially allow for in-vivo dosimetry.

Methods:

An anthropomorphic pelvic phantom is used to validate the clinical potential of the time-resolved dose method for range verification in the case of prostrate treatment using range modulated anterior proton beams. The method uses a 3 × 4 matrix of 1 mm diodes mounted in water balloon which are read by an ADC system at 100 kHz. The method is first validated against beam range measurements by dose extinction measurements. The validation is first completed in water phantom and then in pelvic phantom for both open field and treatment field configurations. Later, the beam range results are compared with the water equivalent path length (WEPL) values computed from the treatment planning system XIO.

Results:

Beam range measurements from both time-resolved dose method and the dose extinction method agree with submillimeter precision in water phantom. For the pelvic phantom, when discarding two of the diodes that show sign of significant range mixing, the two methods agree with ±1 mm. Only a dose of 7 mGy is sufficient to achieve this result. The comparison to the computed WEPL by the treatment planning system (XIO) shows that XIO underestimates the protons beam range. Quantifying the exact XIO range underestimation depends on the strategy used to evaluate the WEPL results. To our best evaluation, XIO underestimates the treatment beam range between a minimum of 1.7% and maximum of 4.1%.

Conclusions:

Time-resolved dose measurement method satisfies the two basic requirements, WEPL accuracy and minimum dose, necessary for clinical use, thus, its potential for in-vivo protons range verification. Further development is needed, namely, devising a workflow that takes into account the limits imposed by proton range mixing and the susceptibility of the comparison of measured and expected WEPLs to errors on the detector positions. The methods may also be used for in-vivo dosimetry and could benefit various proton therapy treatments.

Keywords: proton therapy, in-vivo range verification, diode dosimeter, prostate AP field

1. INTRODUCTION

Proton beams exhibit a depth-dose profile characterized by a Bragg peak with a sharp distal falloff. The position of the Bragg peak in depth and its weight can be varied by changing both the beam energy and beam intensity to conform the dose to a predetermined volume.1 Due to this feature, the use of protons in the field of radiation oncology is gaining prominence, especially in treatments where critical organs are located near the tumor site.2 However, the determination of the precise location of the Bragg peaks inside the patient has uncertainties contributed by several factors, e.g., conversion of Hounsfield unit to stopping power ratios, dose calculation approximations, organ motion, and inter and intra fractional variations in patient setup.3–6 Such uncertainties might lead to inadequate distal dose coverage of the tumor volume or overshooting, displacing the Bragg peak to normal tissues behind the target thus depositing maximum dose in them.

In order to manage the effect of this range uncertainty, proton centers currently plan the beam range with an extra margin to ensure the distal coverage of the target volume. Most institutions use 3.5% of the beam range and an additional millimeter for cases without significant organ motion or setup variations, and add more accordingly if these effects are present. This practice can affect the treatment quality for certain treatment sites, sometimes significantly, as for the case of prostate treatment. In principle, the prostate should ideally be treated by anterior or anterior-oblique fields, since such fields can use the sharp distal falloff (4 mm at 50%–95%) to spare the anterior rectal wall as a primary dose limiting organ.7 The typical beam range to treat prostate with an anterior beam is 15 cm. If we follow the current practice, the extra range margin needed will be around 5 mm, even without considering the daily variations along the beam path, for example, variations in bladder filling. Because the anterior rectal wall is immediately adjacent to the posterior edge of prostate in certain areas and is about 3–5 mm thick when an endorectal balloon is used, this extra 5 mm range would deliver full dose to the anterior rectal wall. Thus, anterior fields can be used to increase rectal sparing only if the beam range in patient can be controlled with millimeter accuracy. Unfortunately, in-vivo range verification in proton therapy is still at early stage of development8–10 and has not yet provided clinically acceptable solution that offers robust control of the proton beam range with millimeter accuracy. Lacking this control, the current prostate treatment technique uses only parallel-opposed lateral beams, which has a number of disadvantages.11 First, the posterior surface of the prostate generally wraps around the concave anterior rectal wall. This geometry makes it impossible to spare the anterior rectum by lateral beams. Second, rectal sparing in treatments by lateral beams relies solely on the lateral beam penumbra. For passively scattered proton beams, the lateral penumbra is around 10 mm (50%–95%) at the typical treatment depth of 25 cm. Third, the lateral beams pass through the thick femoral heads, delivering a non-negligible amount of dose to them despite it is still within the tolerance of the treatment.

We have shown recently in a treatment planning study that anterior fields significantly improved the proton dose distribution compared to lateral fields.7 To take advantage of this feature, we have been developing a range verification technique specifically for the use of anterior fields in prostate treatment.12–14 It is to provide a “range check” right before each treatment so that the beam range can be accurately determined with millimeter accuracy on every treatment day to fully exploit the benefits of the anterior fields. The principle of the technique is based on our earlier work showing that time-resolved measurement of dose function for passively scattered beams could be used to determine the water equivalent path length (WEPL) traversed by the beam.12 Recently, we have studied the effects of tissue heterogeneity on this technique and also extended the analysis method to accommodate diode dosimeters with significantly different time characteristics.13,15 In this paper, we report a prototype of this range check system and the testing results on an anthropomorphic pelvic phantom for an anterior treatment field.

2. MATERIALS AND METHOD

2.A. WEPL determination based on time-resolved dosimetry

The principle of the method was described in details in Refs. 12 and 14 and will be mentioned here briefly. It is based on the unique temporal characteristics of the dose distribution produced by rotating modulator wheel. Modulator wheels are widely used in passive scattering systems to produce the range modulation for the construction of the SOBP fields. The beam current is gated relative to the modulator track and can be turned off at any selected position, so that only a particular group of deeper Bragg peaks participates in the superposition to produce the desired modulation width. As a result, the dose function at every point in depth has a unique pattern in its time dependence. In other words, the time-dependence pattern “encodes” the WEPL to the point of observation. The dose patterns corresponding to all WEPL can be obtained a priori either by time-resolved measurement in phantoms or by computations based on modeling or Monte Carlo.

In practice, one can measure the pattern of dose as a function of time at given point of interest within or behind a given medium, then find it’s best matching pattern from a pre-established library of dose functions measured in water phantom. Then, we take the WEPL of the matching pattern to be the WEPL from body surface to the point of measurement. A simple least square fit was found sufficiently effective for pattern matching in the exercise in Ref. 12. Note that the method works effectively only when the points of interest are located within the dose plateau of the SOBP. At depths either proximal or distal to the dose plateau, the time dependence of the dose function is much less sensitive to changes in WEPL and as a result, the method becomes much less accurate.

We have conducted a number of tests of diode detectors to be used as dosimeters for this technique.14,15 Without the need of a bias voltage, such dosimeters are safer for patients and have been used routinely for in-vivo dosimetry measurements in photon therapy. Moreover, diode detectors can operate at a much lower dose rate compared to ion chambers and will minimize the extra dose to patient for the range check. We have also developed a new approach for decoding the WEPL particularly applicable to diode detectors.14 In this approach, the root-mean-square (RMS) of the duration of the dose signal from each rotational period of the modulator wheel is used as the primary parameter for “decoding” the WEPL. These values are converted to the corresponding WEPLs by a calibration function which is obtained by measuring the RMS values of the duration of the dose patterns at a number of known WEPLs and a simple polynomial fitting. The new analysis method is simpler to implement than the original method of pattern matching which requires the measurement of the signal pattern at every depth, and yet sufficiently accurate14 and will thus be solely used in this paper.

2.B. WEPL measurement by the prototype in-vivo range check system

2.B.1. System setup

Figure 1 shows an overview of the instrumentation we used to conduct in-vivo measurement of WEPL for prostate treatment by anterior beams. The prototype detector-preamplifier-data-logger assembly is build following the traditional configuration of nuclear physics experiments of a short cable/preamplifier/long cable. This configuration is devised to tackle the common issue of dealing with detectors that put out tiny charges (like the diodes in our case), and thus, a great need for minimum noise electronics and cables is required. In this configuration, only the short cable, between the detector and the preamplifier, matters since their total capacitance directly affects the final signal-to-noise which is, at the same time, totally immune to the length and other specs of the long cable. In this framework, we carried out bench tests to determine the best specs of the short cable between the diodes and the preamplifier. Details of these tests can be found in Ref. 21 (Fig. 24 and associated text). As results of those tests, we have elected to use 1 m long, twisted, and shielded single strand 30-gauge magnet wires as a short cable. For the long cable, we used 75 foot long RG-178B/U miniature Teflon-insulated 50 Ω coaxial cable to the digitizer which is kept in the treatment control room.

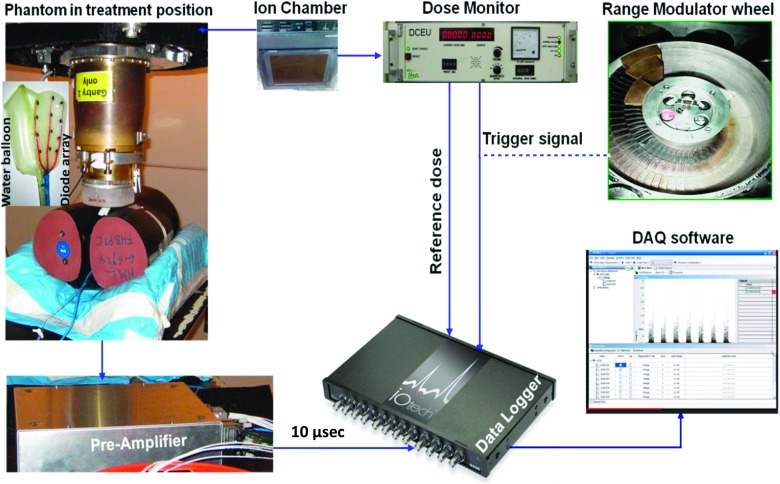

FIG. 1.

Overview of the in-vivo range verification setup and data flow.

The detector assembly consists of a home-made matrix of 12 diodes, model DFLR1600, manufactured by diode incorporated, wired in three columns in a grid like layout housed in a silicone pad. The water equivalent thickness from the front surface of the detector assembly to the active volume of the diodes was 3 mm, including 2 mm for the silicone padding material and 1 mm for the casing of the diodes. They were measured using range pull back method applied to the diode array in its silicone housing. Then, the thickness of the silicone layer is estimated using geometric measurement and the density of the silicone. The detector assembly was first taped to the anterior surface of a rectal water balloon (Radiadyne, Houston, TX) and then inserted into the rectum hole of the pelvic phantom. The diodes were connected to an in-house built, current to voltage preamplifier with a gain of 0.5 V/nA. The details of the preamplifier can be found in Ref. 21. The output of the preamplifier is sent to a digitizer with 16 bit ADCs and a sampling rate of 100 kHz. The digitizer is linked to a PC via a 10/100BaseT Ethernet cable. A data logging software provided along with the digitizer by the manufacturer (Measurement Computing™, Norton, MA) is used to acquire and store data in the PC for further analysis.

In our passive scattering system, the proton beam current is synchronized to the rotation of the modulator wheel by the beam current modulation (BCM) system that controls the ion source of the cyclotron and turns the beam on and off for each rotation of the wheel.16 The digitizer is triggered by this “beam-on” signal by connecting it to one of the digital I/O pins designated as a trigger source in the data logging software. The digitizer is also equipped with counters, one of which is connected to the same signal that drives the digital counter electronic unit (DCEU). The number of monitor units (MU) delivered can be calculated from this signal using the conversion 300 counts = 1 MU which is the default calibration of the proton therapy ion chamber based dose monitoring system.

For this study, the data logging software was setup to start acquisition on a trigger and stop 2 s after that. Since the sampling rate is 100 kHz, a total of 200 K samples are acquired for each channel in this duration. The period of the range modulator wheel is 100 ms and therefore, 20 beam bursts, each corresponding to one complete rotation of the wheel, are captured per acquisition for each channel.

2.B.2. Phantom setup and acquisition of time-resolved dose data

2.B.2.a. Solid water phantom.

A solid water phantom was used for preliminary verification of the accuracy of the time-resolved dose method (TRDM) in homogeneous media. The diode array was placed at the isocenter, under a stack of solid water. The total WEPL to the active area of the diodes was 14.78 cm including 14.58 cm of solid water and 0.2 cm (water equivalent thickness) of silicone housing of the detector array. These two WEPLs (14.58 and 0.2 cm) were measured in a separate experiment using pristine proton beam range pullback method in which the profile of the pristine Bragg peak of 230 MeV proton beam is measured in water with and without the stack of solid water and the diode array, respectively. The shift in centimeters between the ranges of the pristine Bragg peaks (depth at 90% of the maximum of Bragg peak profile) from the two measurements corresponds to the WEPL of the object under the test (i.e., solid water stack and diode array, respectively).

Separately, the measurements of the total WEPL with TRDM were performed using a “scout SOBP beam” which is the same as the treatment beam (i.e., same nozzle configuration) but with the beam range increased to 18 cm. Previously, the same scout SOBP beam was used with the diode array to establish the relationship between the RMS of the dose rate signals and the WEPL, i.e., the function σt(w) as reported in Ref. 21. The collected data were analyzed and the water equivalent path length to the diodes was derived.

2.B.2.b. Anthropomorphic phantom.

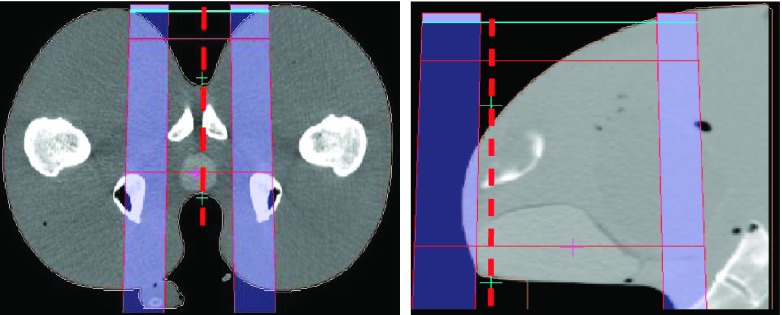

An anthropomorphic pelvic phantom was designed and fabricated (in collaboration with Physics Laboratory, New York, NY) specifically for testing the range verification system. It contains a prostate volume made of material with a slightly different density compared to surrounding tissues, a tubular rectal cavity and a bladder that can be filled with water. Samples of the tissue equivalent materials that were used, respectively, to build the pelvic phantom’s soft tissue, and prostate organs were CT-scanned and their respective densities were verified to be near water equivalent. The respective ratios of their geometric thicknesses to their water equivalent thickness were found equal to 1.02 and 1.04, respectively. The phantom was CT scanned in the same condition as in a treatment, i.e., with a full bladder and water filled rectal balloon in position. A dummy dosimeter array was used to indicate the possible locations of the diode detectors in an actual treatment session. A straight anterior treatment beam (AP) was planned in double scattering mode using the Xio proton planning system (Elekta, Inc, Sweden). The specific aperture and range compensator designed for this treatment were fabricated. The AP field has a beam range of 14.1 cm and modulation width of 11 cm, designed to deliver full dose coverage to the prostate. The “scout” beam used for the WEPL measurement was the treatment beam with the range extended to 18 cm in order to cover the diodes within the SOBP. Figure 2 shows transversal (right) and sagittal (left) slice from CT scan of the pelvic phantom with water balloon and a matrix of BBs used as dummy detectors to simulate the position of the diodes. A schematic representation of the scout SOBP beam is added to show the ideal position of the diodes within the SOBP, which is within the few centimeters of the SOBP before the distal falloff.

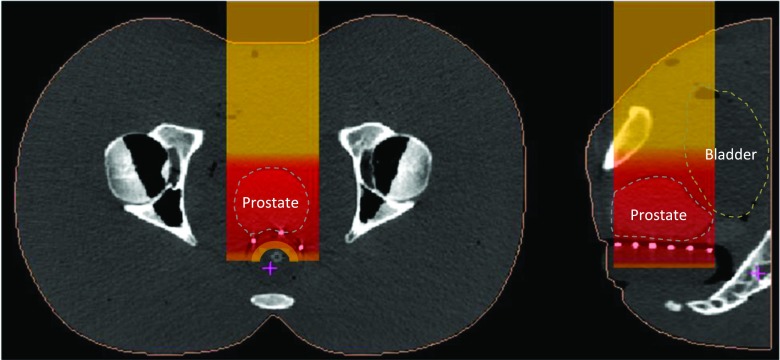

FIG. 2.

Position of the diodes (white dots at the rectum–prostate interface) within the scout SOBP beam.

The x-ray positioning system of the proton treatment room is used to place the pelvic phantom, with the diode array on the water balloon, inserted into its rectal cavity at the treatment position in reference to the orthogonal and beam’s eye view DRRs. The radiographs in Fig. 3 show the locations of the diodes in both orthogonal views.

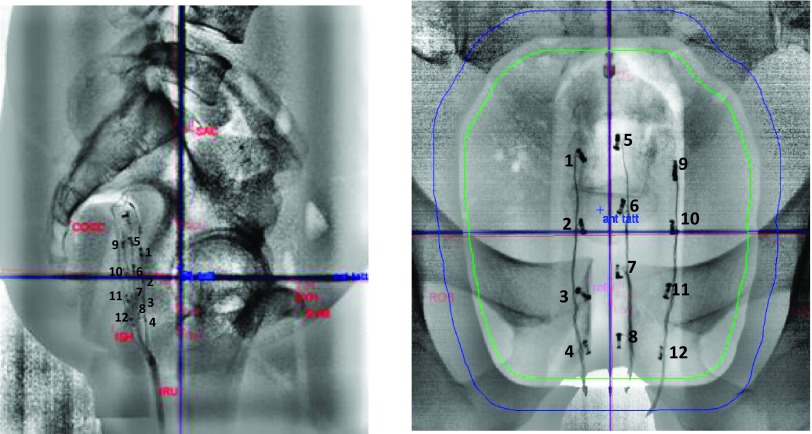

FIG. 3.

Lateral right and AP x-ray radiographs of the pelvic phantom with the matrix of diodes which were used to collect the data are presented in this paper.

Time-resolved dose data were taken for two configurations, one with the aperture and compensator in place (referred hereafter as treatment field) and one without (open field). The data were acquired twice per beam for 2 s for each acquisition, corresponding to 20 modulator wheel periods. During the experiments, the channels 10 and 12 showed exceptionally large noise making the data analysis difficult at times, while channels 7 and 11 had no readout signals at all. Those issues were largely due to poor electric contacts from wiring the diodes and the insertion process. As a consequence, no reliable results were obtained from these four channels.

2.B.3. Data analysis

The collected data, voltage as a function of time, are analyzed using in-house developed software that calculates the moments (mean and RMS) for each channel after performing the following data conditioning. The first step identifies the beginning and ending positions in time for each beam-on segment, taking advantage of the perfect periodicity of signal (100 ms) resulting from the precisely controlled rotation of the modulator wheel. The next step estimates the DC baseline offset. Due to the high amplifier gain, voltage offsets are inevitable and they have to be subtracted from each reading. This correction voltage “vcorr” is obtained by calculating the mean over a narrow region (over 90% of maximum) of the peak in the smoothed voltage spectrum after the removal of the beam on segments from the raw signal. Details of this procedure are reported in Ref. 21. After the subtraction of vcorr from the readings, the second order moments (RMS) of the time dependence of the beam-on signals are calculated. The moments for each single burst are calculated and then averaged. In the case of multiple acquisitions, the averages from the individual acquisitions are averaged. The WEPL to each diode location is then derived from the averaged RMS values based on the function σt(w) mentioned earlier.

2.C. WEPL measurement by the dose extinction method (DEM)

This measurement was intended to provide a reference value to be compared to the WEPL values measured by the range check system discussed in Sec. 2.B and those provided by the treatment planning system to be discussed in Sec. 2.D. The principle of the method is rather simple. Basically, it utilizes the fact that the beam range in our system is defined as the distance from the surface of the water tank to the 90% dose level on the distal dose falloff and is calibrated within 0.5 mm. To obtain the WEPL value from the phantom surface to the dosimeter location, we only need to find the beam range that will deliver 90% of the dose relative to the dose plateau of the SOBP. The process is illustrated in Fig. 4.

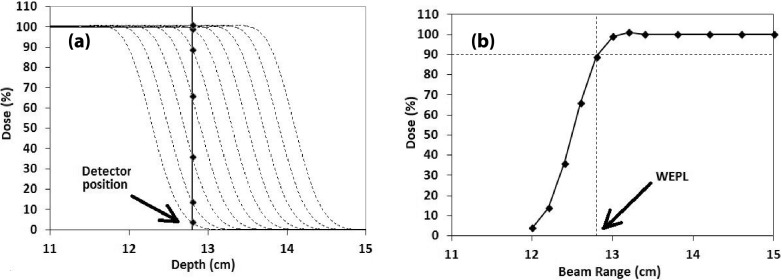

FIG. 4.

Illustration of WEPL measurement by dose extinction. Plot (a) shows the depth-dose profiles around the dose falloff for the beam ranges used in the measurement (dotted lines), all normalized to the dose plateau. Plot (b) shows the measured dose value as a function of beam range. The beam range that gives 90% of the dose is the measured WEPL value.

The measurement uses a group of SOBP beams with variable beam ranges that are close to the WEPL to be measured. The dosimeter is fixed at one location in the phantom, but the beam range is reduced gradually in steps and at each beam range, the dose received by the dosimeter is measured and then normalized relative to the dose plateau of the depth-dose profile for the particular beam range. As the beam range decreases, the dose measured by the detector decreases and eventually becomes zero, thus, the extinction. If one then plots the measured and normalized dose value as a function of the beam range, as in Fig. 4(b), the beam range that gives 90% of the dose will be the WEPL value.

We first validated the dose extinction method in solid water slabs (14.6 cm) using a parallel plate Markus chamber as the detector. Then, we repeated the test using the same solid water slabs and the same group of beams, but the diode detector array, i.e., with the same setup as that described in Sec. 2.B.2.a for the range check measurement in homogeneous medium. The dose extinction measurements were taken with a starting beam range of 15.2 cm and decreasing in steps of 2 mm until 14.2 cm and then decreasing in steps of 1 mm until 13.2 cm. Four dose readings were taken for averaging at each beam range.

Next, we performed the dose extinction measurements with the setup described in Sec. 2.B.2.b for the range check method with diode detectors in the anthropomorphic pelvic phantom. The measurement was done for both beam configurations, with aperture and compensator (treatment field) and without them (open field). For the measurement with open field, the beam range was decreased from 15.2 cm to 11.9 cm in steps of 1 mm. For the treatment field configuration, the range was decreased from 15.2 cm to 13.3 cm in steps of 1 mm and then decreased until 12.7 in steps of 2 mm. There were two dose readings taken for each range. These measurements provided a reference value for the WEPL values from the anterior surface of the phantom to the locations of the diode detectors to be compared against those obtained from the measurement in Sec. 2.B.2.b based on time-resolved dosimetry.

2.D. WEPL calculation by treatment planning system

The Xio proton planning systems (Stockholm, Sweden) provide a tool for computing the WEPL between two selected points. The actual positions of the diodes in the isocenter plan are derived from their 2D projections in the orthogonal x-ray radiographs shown in Fig. 3, following the same clinical procedure used to determine the position correction vector of patient setup which has an uncertainty of 1 mm in each of X, Y, and Z directions. The diodes coordinates are then transformed into the coordinate system of the planning CT. The beam entry point corresponding to each detector was determined by ray tracing, considering the divergence of the beam. The WEPL value between the two points is subsequently calculated. The calculation is based on the CT calibration equation for the conversion of the CT Hounsfield units to relative stopping power.

3. RESULTS

3.A. Verification and validation in solid water phantom

The dose extinction measurement with the Markus chamber produced an average value of 14.7 cm for WEPL from the surface of the solid water phantom to the active volume of the chamber. Given 1 mm water equivalent thickness of the chamber window, the measured water equivalent thickness of the solid water stack is then 14.6 cm, in excellent agreement with the value of 14.6 cm determined by the traditional range pull-back method.

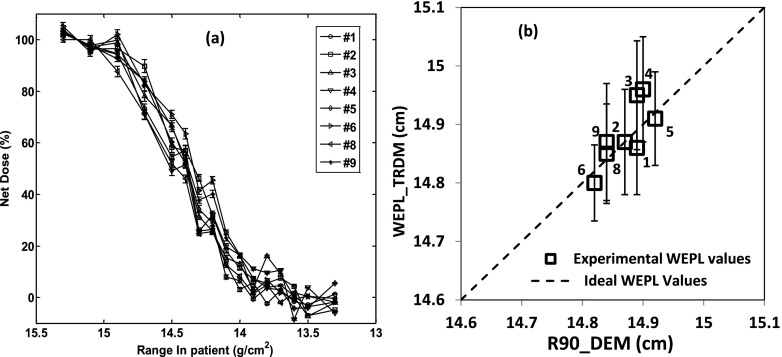

Figure 5 shows the results from the dose extinction measurement using diodes at 14.9 cm water equivalent depth (i.e., 14.6 cm of solid water stack added to 0.2 cm of silicone layer housing the diodes and 0.1 cm of the casing around the diodes sensitive junction). Figure 5(a) plots the measured dose versus the beam range for the eight functioning channels. Figure 5(b) shows the correlation between the WEPLs obtained from the time-resolved dose method (Sec. 2.B.2.a) and the results from the dose-extinction method. The mean value of WEPLs over the eight functioning diodes from the dose-extinction method was 14.9 ± 0.03 cm and that from the time-resolved dose method was 14.9 ± 0.05 cm. The average of the standard deviation over the four readings for each diode was 0.09 cm for the time-resolved dose method.

FIG. 5.

Results for the solid water phantom test. (a) is the dose extinction data for different channels normalized to the SOBP dose. (b) is the correlation between the results of dose extinction method and those by the time-resolved dose method. It included only the diodes that are properly functioning. The error bars represent the standard deviation on the values of time-resolved dose methods from the four measurements.

3.B. Verification and validation in pelvic phantom

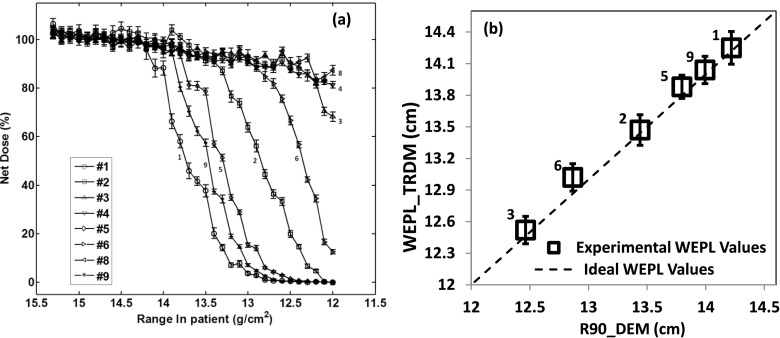

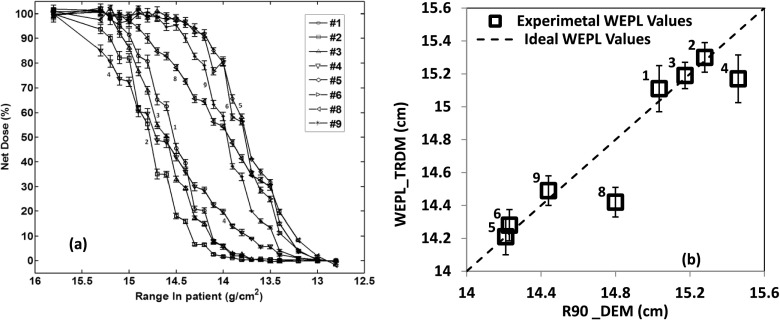

Figures 6 and 7 show the results for the pelvic phantom, respectively, in the case of open field and in the case of treatment field. Figures 6(a) and 7(a) show the data measured from the dose extinction method for the two cases, respectively. Figures 6(b) and 7(b) show the correlation between the WEPL values obtained from the dose extinction data and those measured by the time-resolved dose method for each of the two cases.

FIG. 6.

Results for the pelvic phantom in the case of open field. (a) is the dose extinction measurements from the different channels normalized to the SOBP dose. (b) is the correlation between the results of the dose extinction method and the time-resolved dose method. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the values of time-resolved dose methods over four measurements.

FIG. 7.

Results for the pelvic phantom in the case of treatment field (with aperture and range compensator). (a) is the dose extinction curves for the different channels normalized to SOBP dose and (b) is the correlation between the dose extinction method and the time-resolved dose method. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the values of time-resolved dose methods over four measurements.

Note that the points in Fig. 6(b) are more spread out continuously than those in Fig. 7(b) in terms of TRDM values. This is due to the absence of the compensator for the open field configuration. The WEPL is solely from the anterior body surface to the anterior rectal wall where the diode detectors are located. As the inferior portion of the body surface slopes down (see Fig. 2), the WEPL decreases substantially. In fact, the WEPL to the diodes that are located mostly inferiorly such as the three diodes, 3, 4, and 8, were so small that the depth scan to characterize the DEM did not go far enough to fully cover the dose falloff of these diodes as is the case for the other channels [Fig. 6(a)]. With the compensator in place in the treatment configuration, the WEPL to the detectors include also the thickness of the compensator. Since the compensator is designed to equalize the WEPL to the distal surface of the prostate target volume, it also equalizes the WEPL values to those detectors that are located at nearly equal distances from the distal surface of the prostate. Given the cylindrical shape of the rectum in the phantom, diodes on the same branch [Fig. 3(b)] should have similar WEPL values and those on different branches should have larger difference between their WEPL values. This matches with Fig. 7(b) where the points basically form three groups, one for diodes 1, 2, and 3 on the left branch, the other for 5 and 6 on the central branch, and 9 on the left branch. The diodes 4 and 8, respectively, the last diode of left branch and last diode of central branch, are outliers. This is because they appear exposed to much greater range degradation as suggested by the shape of their dose extinction curves in Fig. 7(a).

In the case of open field configuration (Fig. 6), the WEPL results from the dose extinction method agreed with the WEPL from the time-resolved dose method with an accuracy of ±1 mm with the exception of channels 4 and 8 which has no DEM WEPL values because they were not sufficiently covered by the DEM depth scan. For the treatment field configuration (Fig. 7), the results from the two methods also agree to within ±1 mm except for the channels 4 and 8, which had lower TRDM WEPL values of 2.9 and 3.8 mm, respectively.

A common feature for all the above results of the WEPL from the time-resolved dose method, for all the three tests carried out, respectively, in solid water phantom and in pelvic phantom with the open field and treatment field, is that all the WEPL values were obtained by delivering the total dose of 7 mGy per data acquisition for 2 s (20 cycles of the modulation wheel).

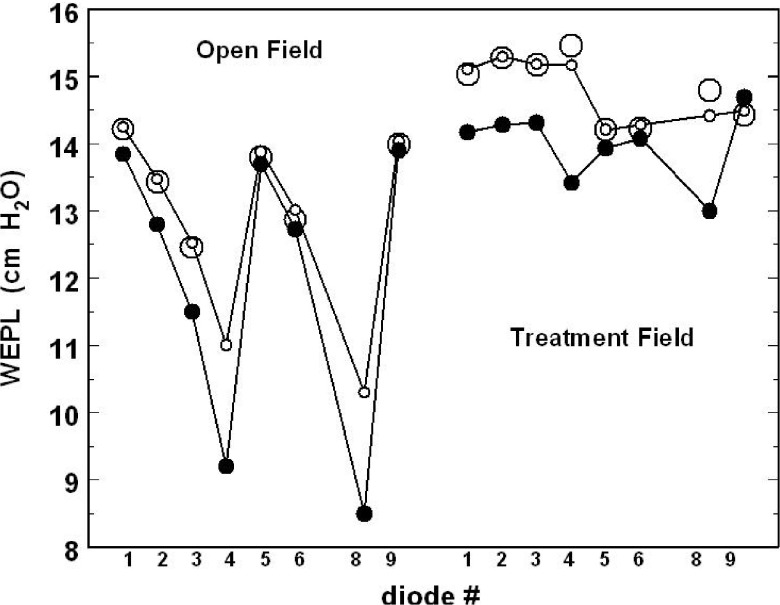

3.C. Comparison with the calculated WEPL from treatment planning system

Table I summarized the WEPL results obtained in the case of open field and in the case of the treatment field and compared them with WEPL values computed, for both configurations, by the treatment planning system (proton XIO) over the same beam paths as the measurements. Figure 8 is a graphic representation of Table I. In case of the open field, the TRDM measured WEPL varies between 10.3 and 14.3 cm, while the expected WEPL values from the treatment planning system are between 8.5 and 13.9 cm. In the case of treatment field, the measured WEPL fits within the window of 14.2 and 15.3 cm, while the expected WEPL from the treatment planning is between 13.0 and 15.7 cm.

TABLE I.

Comparative table of the WEPL values measured by the DEM and TRDM with the TPS WEPL values.

| WEPL in open field (cm) | WEPL in treatment field (cm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diodes # | DEM | TRDM | TPS | DEM | TRDM | TPS |

| 1 | 14.2 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 15.0 | 15.1 | 14.2 |

| 2 | 13.4 | 13.5 | 12.8 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 14.3 |

| 3 | 12.4 | 12.5 | 11.5 | 15.2 | 15.2 | 14.3 |

| 4 | — | 11.0 | 9.2 | 15.5 | 15.2 | 13.4 |

| 5 | 13.8 | 13.9 | 13.7 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.0 |

| 6 | 12.9 | 13.0 | 12.7 | 14.2 | 14.3 | 14.1 |

| 8 | — | 10.3 | 8.5 | 14.8 | 14.4 | 13.0 |

| 9 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 14.4 | 14.5 | 14.7 |

FIG. 8.

Graphic representation of the WEPL values for all the operational diodes in pelvic phantom for the open field and treatment field configurations. Small circles represent TRDM; large circles represent DEM; and solid circles represent TPS.

The difference between the measured WEPL and the planned [treatment planning system (TPS)] WEPL for both configurations varies strongly from diode to diode. Based on this difference, one can sort the diodes into three groups. Diodes # 4 and # 8 show the largest deviation which amounts to 18 mm for both open field and treatment field, respectively, equivalent of a difference of 21% and 13.0%. Diodes # 1, # 2, and # 3 make the second group with moderate deviations of the measured WEPL from the planned WEPL. It is between 4 and 10 mm with an average difference of 5.7% for the open field and 6.5% for the treatment field. Diodes # 5, # 6, and # 9 give the smallest deviation of the measured WEPL from the planned WEPL. It is between 1 and 3 mm, with an average difference of 2.2% for open field and 1.7% for treatment field.

4. DISCUSSION

Using anterior or anterior-oblique fields in proton, prostate treatment could potentially reduce dose to anterior rectal wall to allow further dose escalation or reduction of rectal toxicity from the current treatment technique by only lateral beams.7 In relevance to the anterior beam treatment approach, we performed tests with a pelvic anthropomorphic phantom to assess the accuracy of an in-vivo WEPL verification method based on time-resolved dose measurement and diode detectors. The dose extinction method was used to establish a reference against which we compared the TRDM WEPL values.

The test in solid water showed that in homogeneous medium, the accuracy of the time-resolved dose method for WEPL measurement is in the submillimeter range. In the case of anthropomorphic pelvic phantom, the agreement between the time-resolved dose method and the dose extinction method is within ±1 mm for the majority of measurement positions. Moreover, only 7 mGy of dose was needed for the TRDM to achieve the above accuracies on the WEPL measurement. Both the accuracy on the WEPL determination and the small amount of the required dose are favorable characteristics for the time-resolved dose method to be applied to pretreatment range verification in prostate treatments. Additionally, diodes are commonly used for in-vivo dosimetry in radiotherapy.17–19 Therefore, since the diodes would remain in the patient during the actual treatment with the adjusted beam range, they can be used to measure the in-vivo dose which will serve to verify the accuracy of the range correction by measuring the dose on the distal fall of the treatment field.

The comparison between the measured WEPL(s) and the WEPL(s) calculated by the treatment planning system (XIO) shows that overall XIO underestimated the WEPL. However, it is not straightforward to precisely quantify with how much! This is directly due to the wide spread in the difference between the measured WEPL and expected WEPL from diode to diode. Three groups of diodes were identified suggesting, respectively, the average differences of 21%, 5.7%, and 2.2% in the case of open field and 13%, 6.5%, and 1.7% in the case of treatment field. This result illustrates a key difficulty for applying the TRDM to patients. It suggests that one must develop a strategy that allows sorting out the diodes results in order to determine which group of diodes to trust and which group of diodes to discard regarding the making of a clinical decision about with how much one should adjust the TPS planned range of the treatment beam?

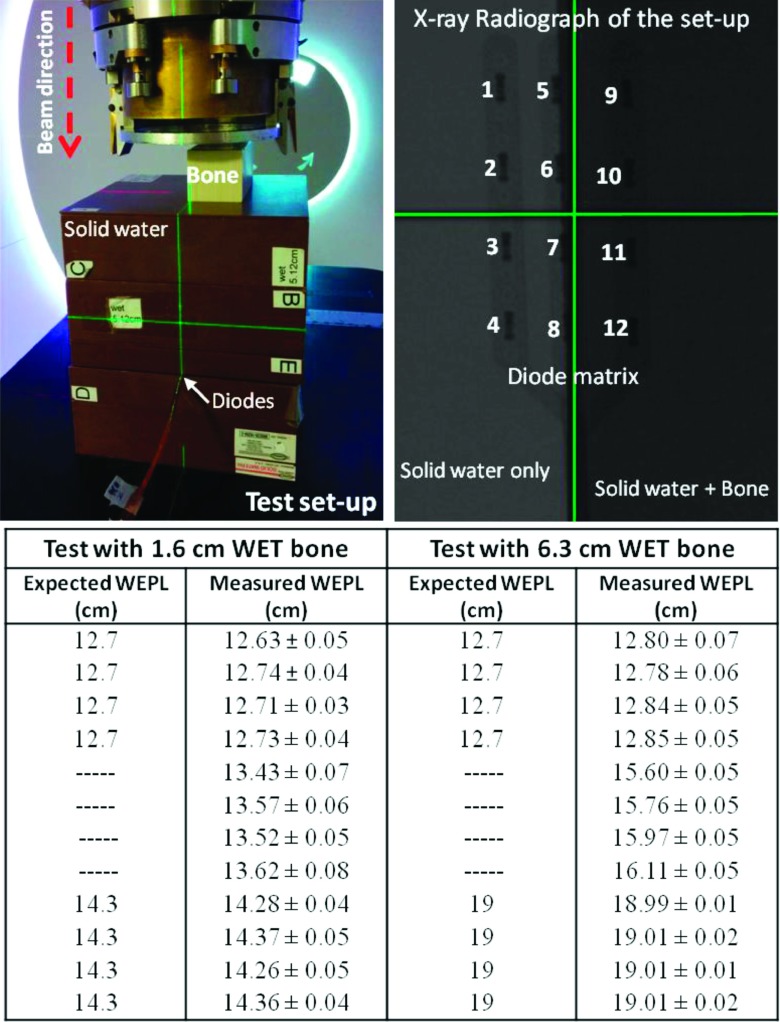

The said strategy may be based on several factors like attributing to each of the diodes an “importance index” and a “trust index” which depend, respectively, on diode position with respect to the treatment volume and with respect to the degree of homogeneity/heterogeneity along the beam path to each diode. The later factor trust index is particularly important because it should represent both the amount of range mixing to which a given diode is exposed and the sensitivity of the measured WEPL to the error one would make in determining the diode location. Figure 9 is simple experimental illustration of the reliability of the results of the TRDM and why decision strategy should be developed. The top left panel of the Fig. 9 shows a simple setup with matrix of diode arrays placed at 12.7 cm depth of solid water, 4 cm after isocenter, with a slab of bone equivalent material at the phantom surface. The top right panel of the Fig. 9 is x-ray radiograph of the setup shown in the first panel. It shows the exact location of each of the diode arrays. The location of the left diode array (diodes # 1–# 4) is such that the diodes are covered only by the 12.7 cm of solid water. The location of the middle array (diodes # 5–# 8) is behind 12.7 cm of solid water but aligned along the interface of the bone slab. The third array (diodes # 9–# 12) is covered by the 12.7 cm of solid water and the bone slab. The test was repeated using two bone slabs with water equivalent thicknesses of 1.6 and 6.8 cm, respectively. The table included at the bottom panel of Fig. 9 compares the measured WEPL by the TRDM to the expected WEPL for each of the diodes. The errors reported for the measured WEPL are the reproducibility errors of the test.

FIG. 9.

Simple experiment to illustrate the reliability of the TRDM against the location of the diodes within heterogeneous media. The errors reported for the measured WEPL are test reproducibility error. The accuracy error is represented by the spread of WEPL measured by each of the three groups of diodes.

The result of the above test shows that the reliability of the TRDM depends on the nature of the protons paths to the detector (diodes). When the protons reach the detectors by crossing one or more homogeneous medium, such is the case for diodes # 1–# 4 and diodes # 9–# 12, the method measures realistic WEPL which compares favorably to the real/expected WEPL. However, when the protons reach the diodes along an interface between two or more homogeneous medium such is the case for diodes # 6–# 8, then the measured WEPL is likely nonrealistic and therefore cannot be trusted. In fact, in the above test, the diodes # 6–# 8 report WEPLs that do not exist physically within the phantom with either bone thicknesses. This situation (diodes # 6–# 8) also highlights another risk of using the method without well developed strategy to sort out the WEPL results. This risk consists in the susceptibility of the expected WEPL to an error on determining the exact location of the diodes. For example, in the test above, making an error of ±2 mm on determining the exact positions of the diodes # 6–# 8 could lead, in the case of test with small bone slab, to expecting a WEPL of either 12.7 or 14.3 cm which will be, in average, 8 mm (6%) different from the measured WEPL (∼13.5 cm). This difference becomes much greater (31.5 mm or 20%) in the case with the large bone slab.

Reflecting the above test results in interpreting the WEPL result with anthropomorphic phantom, one can identify the diodes # 4 and # 8 as outliers. The observations that support this argument are found in Figs. 10 and 7(a).

FIG. 10.

Axial and sagittal CT slices showing the location of diode # 8 and the steep curvature of the phantom surface at this location. The sign (+) in these figures represents the beam entry point to the phantom starting from which the expected WEPL is computed.

Figure 10 shows an axial and a sagittal CT slice where the position of diode 8, located below the prostate, is marked with “full white circle” symbol. The beam path is marked with the dashed red line. The location of this diode happens to be in a place where the change in the curvature of the phantom surface is very steep. Although not shown here, diode 4 is in a similar situation. In addition to the steep curvature of the phantom surface, both diodes (# 4 and # 8) happen to be located, respectively, behind an interface of soft tissues and the femur bone and soft tissues and the pubic bone, which increases the likelihood of range mixing13,20 and the susceptibility of the WEPL to errors on the diode positions. Figure 7(a) shows that the profiles of the dose falloff measured by diodes # 4 and # 8 are distinctively broader comparing to the dose profiles measured by the rest of the diodes. This observation suggests again that the unbalanced beam scattering caused by the steep curvature of the phantom’s surface and the interfaces between the bones and soft tissues broadens the energy spectrum of the protons that reach the diodes # 4 and # 8. This affects the reliability of WEPL measurement by these two diodes for both methods (DEM and TRDM), suggesting that one should discard them from any comparison to the TPS planned WEPL(s).

Discarding the result of diodes # 4 and # 8 suggests that the treatment planning system underestimates the treatment beam range by 4.1%. This value is at the upper end to the usual range correction commonly practiced in the proton therapy clinics which consist of systematically increasing the TPS planned beam range by about 4% ± 1% depending on the institution. Further scrutiny of the WEPL result suggests that the first group of diodes (# 1, # 2, and # 3) may also have to be discarded or have their weights in the clinical decision reduced because they are located closer to the edge of the treatment field which makes them exposed to the range mixing caused by the edge of the aperture and the edge of the range compensator. It is noteworthy to highlight that picking only diode # 5 and diode # 6 as most relevant for clinical decision is likely the optimal choice. Such choice can be justified by the importance of the location of these two diodes as been right behind the prostate and having no significant heterogeneity gradients between them and the phantom surface. Taking such decision leads to only 1.9% and 1.4% of WEPL correction for the open field and treatment field, respectively, which is in good agreement with the range correction suggested by the theoretical prediction as reported by Paganetti in Ref. 3.

Summarizing the limitations of this study, we must point out: (i) the steep slope of the body surface shown in Fig. 10 is purely due to the absence of the penile structure in the phantom (by mistake) and would not be the case in a real male prostate patient. (ii) It seems obvious the TRDM would perform better and will be easier to implement if 3D imaging, such as cone beam CT, is available in the treatment room. This is simply because the diodes positions would be determined with greater accuracy comparing to when relaying on 2D orthogonal x-ray radiographs as it is the case of this study. (iii) The comparison of the measured WEPL with the WEPL expected from the TPS is very sensitive to the diodes locations and the accuracy with which one can determine their positions. This is particularly true in the case where diodes are located along interfaces between two body parts with large density difference such as bone and soft tissue. (iv) While a straight AP field works well in anthropomorphic phantom, it may not work as well in patient. This is because of the fact that the beam traverses the patient bladder, which is as opposite of the phantom bladder and is hard to guarantee its filling level for every treatment. For this reason, the application of the method to patients could be more successful if applied with AP oblique field, about 30° inclinations as reported by Tang et al.7 In such configuration, the treatment beam will interact minimally with the patient bladder, traversing only the lower tip of it which is easier to maintain full at all time.

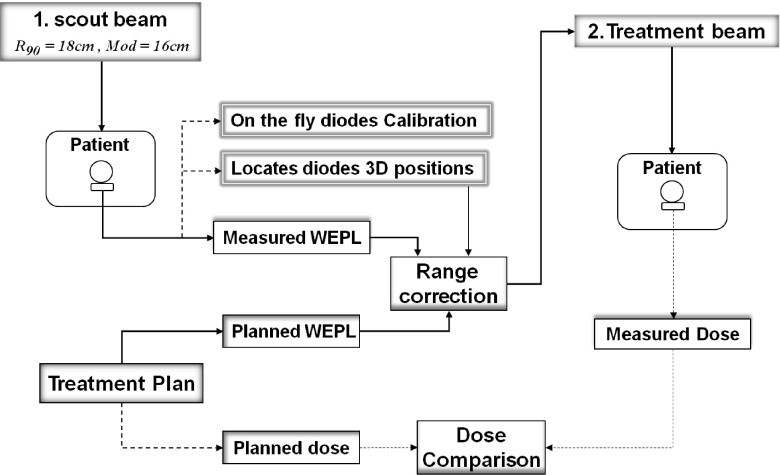

Envisioning a realistic workflow for protons treatment of prostate using AP field with in-vivo beam range verification, one can proceed as follow: the patient is setup with a rectal water balloon, as widely practiced for prostate treatment by proton therapy, but with arrays of dosimeters embedded on the anterior surface of the water balloon, i.e., positioned right below the anterior rectal wall. A beam with a range of a few centimeters longer than that for the actual treatment field (a scout beam) is then used to deliver a very small amount of dose (<10 mGy). The time dependence of the dose at the embedded dosimeters is captured and then analyzed to derive the WEPL from the anterior surface of the patient’s body to the inner side of the anterior rectal wall. Then, by comparing the obtained WEPLs values to those computed by the treatment planning system, verification and/or correction of the beam range, if necessary, can be achieved for the particular treatment that immediately follows. The comparison of the measured and planned WEPLs must be done following a well established procedure that takes into account the particularities of each diode in terms of the amount of range mixing to which each diode is exposed and how sensitive its location is to determine the correct expected WEPL. Figure 11 shows a schematic of the actual treatment workflow and the suggested modification to incorporate the time-resolved dose method for treatment beam range check.

FIG. 11.

Schematic of modified proton therapy treatment workflow to include pretreatment range check and in-vivo dosimetry.

One can predict that the above workflow scenario could be applied to improve the treatment of several tumor sites by proton therapy, other than treating prostate with AP and AP oblique fields. For example, the method could be used for range verification and correction of the brain fields of medulloblastoma patients in order to reduce the exit dose to the cranial skin and thus reduce the risk of alopecia (permanent hair loss).22 Also, the method could be used to optimize full dose coverage in the treatment of the spinal target volume while sparing the patient esophagus (in cranial-spinal irradiations), assuming the in-vivo detector array can be inserted into the patient esophagus. Proton therapy treatment of prostate cancer by hypo-fractionation may also benefit from this workflow and method. That is because monitoring the dose per fraction of the treatment, which is the secondary goal of the method, provides the necessary confidence and the safety for escalating the treatment dose.

5. CONCLUSION

We demonstrated a proof-of-principle of an in-vivo range verification system that allows measuring WEPLs with millimeter accuracy in comparison to a reference WEPL measurement method (DEM). The method offers potential path to conduct range guided proton treatment which could potentially enable the treatment of some tumor sites with more precision and effectiveness such as the treatment of prostate using AP fields. Its use on patient requires further technical and workflow development. Devising a clear strategy on how to reach clinical decision using the measured WEPLs is of utmost importance. The method also allows one to measure the dose during the treatment which can be used for range cross check and as safety mechanism for the treatment. The cost effectiveness of this method is another attractive feature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partly funded by IMAGX/PPP-1 of Region Walloon - Belgium and was supported in part by MGH-NIH Federal Share Grant and NIH/NCI p01 CA21239. One of the authors, Bernard Gottschalk thanks the Harvard University Physics Department for ongoing support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson R. R., “Radiological use of fast protons,” Radiology 47, 487–491 (1946). 10.1148/47.5.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foote R. L.et al. , “The clinical case for proton beam therapy,” Radiat. Oncol. 7, 174–184 (2012). 10.1186/1748-717x-7-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paganetti H., “Range uncertainties in proton therapy and the role of Monte Carlo simulations,” Phys. Med. Biol. 57, R99–R117 (2012). 10.1088/0031-9155/57/11/r99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang M., Zhu X. R., Park P. C., Titt U., Mohan R., Virshup G., Clayton J., and Dong L., “Comprehensive analysis of proton range uncertainties related to patient stopping-power-ratio estimation using the stoichiometric calibration,” Phys. Med. Biol. 57, 4095–4115 (2012). 10.1088/0031-9155/57/13/4095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trofimov A., Unkelbach J., Delaney T. F., and Bortfeld T., “Visualization of a variety of possible dosimetric outcomes in radiation therapy using dose-volume histogram bands,” Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2(3), 164–171 (2012). 10.1016/j.prro.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaffner B. and Pedroni E., “The precision of proton range calculations in proton radiotherapy treatment planning: Experimental verification of the relation between CT-HU and proton stopping power,” Phys. Med. Biol. 43(6), 1579–1592 (1998). 10.1088/0031-9155/43/6/016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang S., Both S., Bentefour E. H., Tochner Z., Efstathiou J., and Lu H., “Improvement of prostate treatment by anterior proton fields,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 83(1), 408–418 (2011). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knopf A.-C. and Lomax A., “In vivo proton range verification: A review,” Phys. Med. Biol. 58, R131–R160 (2013). 10.1088/0031-9155/58/15/r131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knopf A., Parodi K., Paganett H., Cascio E., Bonab A., and Bortfeld T., “Quantitative assessment of the physical potential of proton beam range verification with PET/CT,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53, 4137–4151 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/15/009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parodi K., Paganetti H., Shih H. A., Michaud S., Loeffler J. S., Delaney T. F., Liebsch N. J., Munzenrider J. E., Fischman A. J., Knopf A., and Bortfeld T., “Patient study of in vivo verification of beam delivery and range, using positron emission tomography and computed tomography imaging after proton therapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 68, 920–934 (2007). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.01.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efstathiou J. A., Gray P. J., and Zietman A. L., “Proton beam therapy and localised prostate cancer: Current status and controversies,” Br. J. Cancer 108, 1225–1230 (2013). 10.1038/bjc.2013.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu H. M., “A potential method for in vivo range verification in proton therapy treatment,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53, 1413–1424 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/5/016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentefour E., Tang S., Prieels D., and Lu H., “Effect of tissue heterogeneity on an in-vivo range verification technique for proton therapy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 57, 5473–5484 (2012). 10.1088/0031-9155/57/17/5473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottschalk B., Tang S., Bentefour E. H., Cascio E. W., Prieels D., and Lu H., “Water equivalent path length measurement in proton radiotherapy using time resolved diode dosimetry,” Med. Phys. 38, 2282–2288 (2011). 10.1118/1.3567498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cascio E. and Bentefour E. H., “The use of diodes as dose and fluence probes in the experimental beamline at the Francis H. Burr Proton Therapy Center,” in IEEE - Radiation Effects Data Workshop (REDW) (IEEE, Las Vegas, NV, 2011), Vol. 1–6. 10.1109/REDW.2010.6062516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu H. and Kooy H., “Optimization of current modulation function for proton SOBP fields,” Med. Phys. 33, 1281–1287 (2006). 10.1118/1.2188072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins P. D., Alaei P., Gerbi B. J., and Dusenbery K. E., “In vivo diode dosimetry for routine quality assurance in IMRT,” Med. Phys. 30, 3118–3123 (2003). 10.1118/1.1626989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jursinic P. A., “Implementation of an in vivo diode dosimetry program and changes in diode characteristics over a 4-year clinical history,” Med. Phys. 28, 1718–1726 (2001). 10.1118/1.1388217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meiler R. J. and Podgorsak M. B., “Characterization of the response of commercial diode detectors used for in vivo dosimetry,” Med. Dosim. 22(1), 31–37 (1997). 10.1016/s0958-3947(96)00152-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urie M., Goitein M., and Wagner M., “Compensating for heterogeneities in proton radiation therapy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 29, 553–566 (1984). 10.1088/0031-9155/29/5/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottschalk B., “Skewness and kurtosis as measures of range mixing in time resolved diode dosimetry” (2014), e-print arXiv: 1407.2931v1, [physics.med-ph].

- 22.Min C., Paganetti H., Winey B. A., Adams J., MacDonald S. M., Tarbell N. J., and Yock T. I., “Evaluation of permanent alopecia in pediatric medulloblastoma patients treated with proton radiation,” Radiat. Oncol. 9(1), 220–226 (2014). 10.1186/s13014-014-0220-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]