Abstract

Skeletal muscle possesses a remarkable capacity for regeneration in response to minor damage, but severe injury resulting in a volumetric muscle loss can lead to extensive and irreversible fibrosis, scarring, and loss of muscle function. In early clinical trials, the intramuscular injection of cultured myoblasts was proven to be a safe but ineffective cell therapy, likely due to rapid death, poor migration, and immune rejection of the injected cells. In recent years, appropriate therapeutic cell types and culturing techniques have improved progenitor cell engraftment upon transplantation. Importantly, the identification of several key biophysical and biochemical cues that synergistically regulate satellite cell fate has paved the way for the development of cell-instructive biomaterials that serve as delivery vehicles for cells to promote in vivo regeneration. Material carriers designed to spatially and temporally mimic the satellite cell niche may be of particular importance for the complete regeneration of severely damaged skeletal muscle.

Keywords: myogenesis, biomaterial, cell therapy, drug delivery, synthetic niche, satellite cell, microenvironment cues

1. INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle comprises a large percentage of the human body mass (40–50%) and plays an essential role in locomotion, postural support, and breathing. In response to minor injuries, such as exercise-induced tears, lacerations, or contusions, skeletal muscle possesses a remarkable capacity for regeneration [1, 2]. These injuries, which account for up to 55% of all sports-related injuries, do not result in significant loss of muscle mass and heal without therapeutic intervention [3]. However, severe injuries resulting in a muscle mass loss of greater than 20% can lead to extensive and irreversible fibrosis, scarring, and loss of muscle function [2]. Traumatic injuries sustained from motor vehicle accidents, aggressive tumor ablation, and prolonged denervation all lead to volumetric muscle loss and are considered common clinical situations [2–4]. Unfortunately, surgical reconstruction does not fully regenerate the lost muscle tissue and often leads to donor site morbidity. As a result, the development of therapeutic strategies to treat severe skeletal muscle injuries is an area of active investigation.

Although extensive research has been carried out in rodents, few clinical trials have focused on therapies for acute skeletal muscle injury in humans, likely due to high variability in the severity and anatomical location of injuries. In contrast, several clinical studies have been carried out aimed at identifying a suitable therapy for muscle damage in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) patients. DMD, a genetic disease resulting from a severe lack of dystrophin in muscle fibers, leads to progressive muscle wasting as muscles remain in a constant state of degeneration and regeneration. Early clinical trials demonstrated the safety of intramuscular cell injections and the ability of transplanted myoblasts to participate in muscle regeneration [5]. However, although new dystrophin production was observed in a few cases, no functional benefit was observed following cell injections. In almost all cases, poor donor cell engraftment was observed and attributed to rapid death, poor migration, and immune rejection of the injected cells [5, 6]. In spite of these limitations in trials with DMD patients, cell transplantation remains a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of traumatic muscle injury. In an attempt to address limitations in cell survival and distribution highlighted by these early clinical trials, experimental studies have largely focused on improving donor cell participation in regeneration, leading to the identification of potentially useful therapeutic cell populations and transplantation strategies.

Skeletal muscle tissue engineering presents a particularly promising therapeutic avenue. A variety of biomaterial scaffolds serving as synthetic extracellular matrices have been developed to provide localized delivery of various cell populations and growth factors to injured skeletal muscle. Further optimization of these biomaterial platforms may lead to significant functional improvement of severely damaged skeletal muscle. Specifically, biomaterial carriers designed to incorporate synergistic biophysical and biochemical cues that mimic the in vivo satellite cell niche may offer dramatic improvements in cell regenerative potential both during ex vivo expansion and in vivo regeneration. Additionally, material systems that provide not only spatially but also temporally appropriate microenvironment cues may ultimately provide the best support for the normal regenerative mechanism.

This review will first provide a short overview of the pathophysiology of skeletal muscle repair, and address recent advances in therapeutic approaches to treat acutely and severely damaged skeletal muscle tissue. The cell source and critical design criteria for the development of biomaterial scaffolds optimal for ex vivo cell expansion and in vivo cell delivery will be highlighted. Future directions and current challenges in the field of skeletal muscle regeneration will also be examined. This review will not specifically examine cell transplantation or growth factor delivery strategies to treat patients with DMD or other myopathies, as potent treatments for these diseases will likely require genetic correction, and a review focusing on therapeutic strategies for muscular dystrophies and aging was recently published [7]. Also, an in depth review of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of muscle regeneration will not be covered, as this topic has been reviewed elsewhere [8–10].

2. BRIEF REVIEW OF RELEVANT SKELETAL MUSCLE BIOLOGY

2.1 Satellite cells and other progenitors

Skeletal muscle is a highly complex tissue containing a hierarchically organized structure that is essential to its contractile function. Within each muscle, bundles of long, cylindrical, multi-nucleated muscle fibers are aligned in parallel, and consist of myofibrils containing sarcomere contractile units. Satellite cells, initially identified by their anatomical location between the basal lamina and the plasma membrane that surrounds each individual muscle fiber, are considered to be a skeletal muscle specific stem cell population [11]. These normally quiescent cells represent only about 5% of myonuclei in healthy adult human tissue but can generate large numbers of myogenic progenitor cells upon muscle injury. Recently, it has been demonstrated that satellite cells, identified by expression of the transcription factor paired box 7 (Pax7), are absolutely required for skeletal muscle regeneration in response to acute injury. Specifically, it was revealed that genetic ablation of Pax7+ satellite cells led to complete regenerative failure following cardiotoxin induced injury, but rescue followed satellite cell transplantation [12–15]. Furthermore, it is suggested that alternative host-derived cell populations possessing myogenic regenerative capacity may depend upon the presence of satellite cells, since Pax7− cell types were unable to compensate for the loss in regenerative potential accompanying Pax7+ cell ablation [12–14].

While all satellite cells can be identified by their combined anatomical location and Pax7 expression, it is important to note that heterogeneity in the muscle satellite cell population exists. In past years, numerous markers have been reported for the isolation and purification of both quiescent and activated satellite cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), emphasizing the high degree of variability that exists for satellite cell gene and cell surface marker expression [16–19]. Specifically, it has been shown that sublaminar satellite cells are heterogeneous for the transcription factors paired box 3 (Pax3), which is only expressed in quiescent satellite cells of a subset of muscles, and myogenic regulatory factor 5 (Myf5), which is not expressed in a subset of quiescent satellite cells [17, 20, 21]. Additionally, nearly all cell surface markers used for the isolation of purified satellite cell populations, including but not limited to CXCR4, c-met, and CD34, are not unique to satellite cells or even to skeletal muscle tissue and consequently must be used in combination [5]. Heterogeneity in satellite cell proliferation kinetics and differentiation capacity in vitro and regenerative potential in vivo also exists [22–24]. For example, satellite cells from different hindlimb muscles display functional heterogeneity, as the transplantation of satellite cells within their myofiber sublaminal niche from tibialis anterior (TA) muscles generated significantly less muscle than satellite cells from extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and soleus myofiber grafts [25]. Functional heterogeneity among satellite cells from the same population has also been reported [26]. It has been suggested that satellite cell populations consist of a small fraction of satellite stem cells that have never expressed Myf5 (~10%) and a large number of committed satellite myogenic cells [17, 27, 28]. More recently, it has been reported that a subpopulation of adult skeletal muscle stem cells, corresponding to high Pax7 expression with a low metabolic state, retains all template DNA strands after cell division and represents a population of satellite cells with more stem-like properties [21].

It is important to note that other progenitors have demonstrated a capacity for participation in skeletal muscle regeneration, many of which can be systemically delivered to potentially increase donor cell distribution. However, contribution to regeneration is low compared to satellite cells, and/or functional data for regeneration with these cell types is not yet available. For instance, the injection of 106 WT BM-derived progenitors contributed only minimally to muscle regeneration in chemically injured TAs of SCID/bg mice. The contribution of the BM progenitors was less than satellite cells, and BM progenitor fibers took longer to appear histologically (5 days for satellite cell repaired fibers vs. 2 weeks for BM-progenitors) [29]. In addition, human skeletal muscle pericytes have been shown to colonize host muscle and generate fibers expressing dystrophin when transplanted into SCID-MDX mice by femoral artery injection [30]. Nevertheless, while pericytes resident in postnatal skeletal muscle possess the ability to differentiate into muscle fibers and generate satellite cells, pericyte myogenesis is minimal in adult muscle [31]. Another cell type, blood vessel associated mesoangioblast stem cells, have also been shown to increase dystrophin expression and ameliorate some loss in muscle function exhibited by dystrophic dogs [32]. More recently, PW1+/Pax7− interstitial cells (PICs) have been shown to be myogenic in vitro and efficiently contribute to skeletal muscle regeneration following injection into freeze-crush injured tibialis anterior muscles of nude mice. When compared to satellite cells injected in contralateral limbs, PICs recolonize muscle tissue as efficiently but with less sharply defined boundaries [33]. However, without muscle function data it is hard to determine the ultimate therapeutic value of many of these cell types. As a result, this review will focus exclusively on strategies to improve satellite cell delivery.

2.2 Skeletal muscle regeneration

In response to acute injury, skeletal muscle follows a predictable regenerative process involving sequential but overlapping phases of inflammation, repair, and remodeling. The initial inflammatory response to skeletal muscle damage is a characteristic Th1 response. During this phase, muscle fiber necrosis leads to plasma membrane dissolution, activation of the complement cascade, and chemotactic recruitment of leukocytes [9]. Within 2 hours, Ly6C+/F4/80− neutrophils begin to appear, typically peaking in concentration between 6 and 24 hours following injury and then rapidly declining [34]. These neutrophils induce muscle membrane damage through the release of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and target tissue debris for phagocytosis through the production of free radicals [35]. Following neutrophil infiltration, two distinct subpopulations of macrophages sequentially invade and help to promote regeneration of the injured muscle tissue. First, phagocytic CD68+ M1 macrophages arrive and remain elevated in concentration from approximately 24 to 48 hours postinjury. These classically activated macrophages secrete proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species [36]. Following M1 macrophage infiltration, macrophages switch to an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype. In vitro, it has been shown that M1 to M2 phenotype switch is obtained after phagocytosis of either apoptotic or necrotic myogenic cells. Specifically, M1 macrophages show decreased expression of iNOS, CCL3, TNFα (M1 markers) and increased expression of TGFβ1, CD163, and CD206 (M2 markers) upon phagocytosis of muscle debris [37, 38]. In vivo, the switch from inflammatory to anti-inflammatory macrophages likely results from phagocytosis of apoptotic and necrotic myofibers, as well as, other environmental cues [39]. The population of nonphagocytic CD163+/CD206+ M2 macrophages then persists for many days postinjury. These alternatively activated macrophages secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) [9].

Satellite cell activation, proliferation, and migration to damaged myotubes occur during the repair phase. Multiple niche factors and signaling pathways appear to initiate satellite cell activation and proliferation following muscle damage. Roles for notch signaling, wnt signaling, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) in satellite cell proliferation and differentiation have been thoroughly reviewed [40, 41]. Satellite cell proliferation leads to the formation of both new quiescent satellite cells and committed myogenic progenitors which express MyoD, Myf5, myogenin and Mrf4. Interestingly, the influx of M1 macrophages coincides with the activation and recruitment of muscle progenitor cells. In vitro, M1 macrophages have been shown to stimulate myogenic progenitor cell proliferation [37, 38]. In contrast, medium from proinflammatory macrophages has been shown to exert negative effects on myogenic differentiation and fusion, while stimulating myogenic cell motility, which may be detrimental for cell fusion [36, 39]. In humans, regenerating areas containing proliferating myogenic progenitors were preferentially associated with macrophages expressing proinflammatory markers [36]. The rise in M2 macrophage concentration coincides with the differentiation of muscle progenitor cells and termination of inflammation. In vitro, anti-inflammatory macrophages and M2 macrophage conditioned medium have been shown to promote myogenic progenitor differentiation by increasing their commitment into differentiated myocytes and promoting the formation of mature myotubes [36–39]. In humans, regenerating areas containing differentiating myogenin-positive myogenic progenitors were preferentially associated with macrophages harboring anti-inflammatory markers [36]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that total impairment of monocyte recruitment into damaged skeletal muscle during the first 24 hour after injury prevents muscle repair [38, 39].

Following inflammation and repair, the remodeling phase leads to the maturation of regenerating fibers and remodeling of the muscle tissue. Newly formed fibers can manifest in a variety of unconventional patterns. Forked fibers may form as a result of incomplete fusion of newly formed myofibers, segmental necrosis may occur following satellite cell fusion with a viable myofiber stump, and satellite myofibers may result from satellite cell fusion under the basal lamina of a preexisting fiber. In rare cases, orphan myofibers may even form outside the basal lamina [9]. Reestablishment of myotendinous junctions, neuro-innervation, and revascularization are required for muscle growth and restoration of muscle function [42–44]. In cases of severe injury, severe fibrosis may lead to myofiber-scar tissue myotendinous junction formation, nerve denervation may lead to atrophic myofibers, and devascularization may lead to ischemia. While permanent loss of muscle function may result if left untreated, therapeutic cell transplantation may provide a return of function.

3. CURRENT APPROACHES TO CELL TRANSPLANTATION

3.1 Cell isolation and manipulation – cultured versus freshly isolated myogenic progenitors

An appropriate therapeutic cell source, and appropriate isolation and manipulation procedures are necessary for successful engraftment of transplanted cells. As demonstrated in early clinical trials, the transplantation of myoblasts cultured from satellite cells was ineffective in human patients due to poor graft survival following injection [45]. It was later determined that culturing satellite cells, even for a short time period on tissue culture plastic, results in a myoblast population that possesses limited regenerative potential, as satellite cells suffer from loss of stemness and generate progeny with greatly reduced regenerative capacity [18]. Upon intramuscular injection, cultured primary myoblasts differ functionally from freshly isolated integrin-α7+CD34+ satellite cells and do not as successfully engraft, proliferate, or give rise to progenitors that contribute to muscle (Figure 1) [19]. The two dimensional constraint and substrate stiffness of conventional tissue culture plastic (~3 GPa) fails to mimic the in vivo satellite cell niche, likely contributing to the major loss in regenerative potential [46]. In contrast, freshly isolated satellite cells subjected to minimal manipulation represent a population with largely preserved stem cell behavior capable of rapid expansion and repopulation of the satellite cell niche. Freshly isolated, FACS purified satellite cells are much more efficient than cultured cell populations in contributing to muscle repair. For example, injection of 104 freshly isolated cells into the TA muscles of immunodeficient nude mdx mice led to engraftment (as measured by dystrophin expression) similar to injection of 105 cultured cells. Clonal assays suggested that the difference in regenerative potential was attributed to more rapid differentiation of the cultured cells [18]. Similar results were obtained in a separate study that demonstrated the injection of 5000 freshly isolated muscle stem cells into notexin-damaged, irradiated muscles of NOD-SCID mice led to engraftment, proliferation, and generation of committed progenitors and new muscle fibers, while injection of 20,000 cultured myoblasts did not [19]. The robust engraftment efficiency of freshly isolated skeletal muscle precursors (contributing to formation of up to 94% of myofibers) has been shown to translate into a therapeutic benefit (5.5 fold greater force production) in mdx mice with a regeneration index (number of donor-engrafted myofibers generated per 105 transplanted cells) up to 40 times greater than previous reports of cultured populations of muscle-derived stem and progenitor cells [16]. Remarkably, even the transplantation of a single freshly isolated muscle stem cell has been shown to lead to remarkable proliferation and self-renewal in vivo when measured with bioluminescence imaging [19, 46]. However, isolation and cell sorting techniques still require cell removal from the satellite cell niche and may result in some loss of stemness.

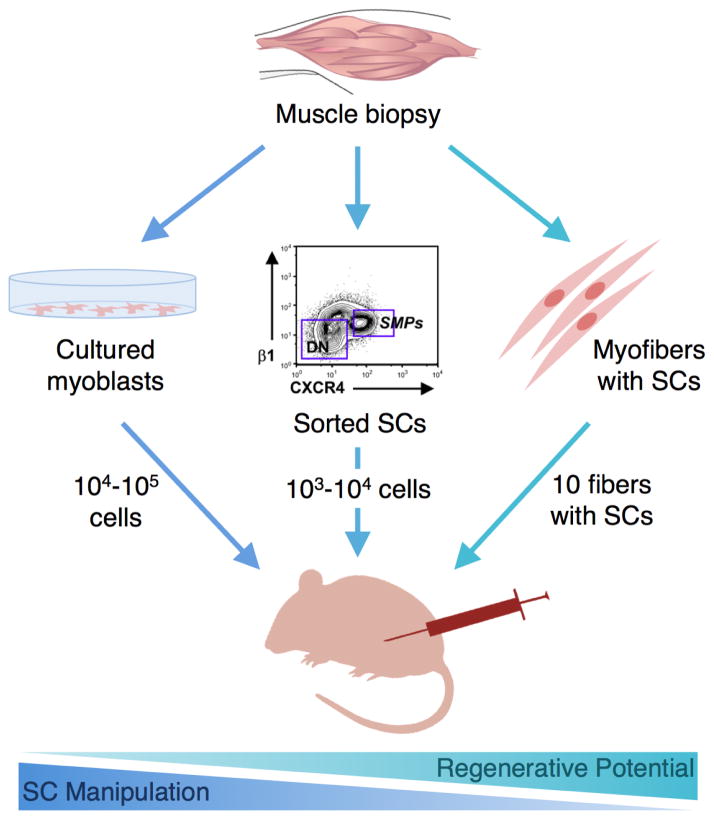

Figure 1. Impact of satellite cell isolation and manipulation on regenerative capacity.

Following muscle biopsy and tissue dissociation, satellite cells are manipulated in different ways to obtain a desired cell population. The extent of manipulation generally determines the loss in regenerative potential that occurs before reinjection. Cells that are subjected to extensive in vitro culture (left) typically exhibit the greatest loss in regenerative potential and must be injected in high quantity. Alternatively, satellite cells that undergo a minimally intensive sorting procedure followed by immediate reinjection (middle) can be injected in lower quantities to obtain regenerative benefit. Satellite cells that are transplanted with their associated myofiber niche (right) demonstrate the greatest regenerative potential, and only a few fibers are required for significant muscle regeneration. Image used with permission [16].

Alternatively, transplantation of satellite cells without removal from their associated myofiber has proven advantageous for maintaining satellite cell regenerative capacity, highlighting the importance of the microenvironment of the satellite cell niche. Transplantation of single intact myofibers (satellite cells transplanted with their associated myofiber) into radiation-ablated muscles has led to the generation of abundant new myofibers and myofiber-associated cells [25]. In fact, it has been shown that injection of 50,000 freshly isolated cells is roughly equivalent to injection of 5 muscle fibers with their associated nuclei, as measured by the number of dystrophin expressing fibers observed in injured mdx mice, demonstrating that transplantation of muscle fibers has the greatest potential per cell to date for regeneration [47]. Furthermore, transplanting myofibers with their associated satellite cells increases muscle mass, myofiber number, and donor myonuclei permanently and prevents muscle aging [48]. As a result, material carriers that mimic the natural satellite cell microenvironment may be useful as synthetic niches for cell transplantation.

3.2 Material systems – synthetic satellite cell niches and sustained cell delivery systems

In addition to the specific therapeutic cell source utilized, the delivery approach may be just as critical to the success of a cell therapy. Cell transplantation approaches using biomaterials that act as synthetic niches by biophysically and biochemically mimicking the natural satellite cell microenvironment may be of great clinical utility for improving survival, engraftment, and fate control of delivered cells (Figure 2, Table 1). Recently, it was demonstrated that ex vivo rejuvenation of aged satellite cells is possible with specific biophysical and biochemical cues [49]. This finding suggests that a better understanding of the satellite cell niche may lead to the development of improved culture techniques to maintain stemness during cell expansion. Certainly this is not an easy task as the satellite cell niche consists of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, vascular and neural networks, various surrounding cells, and a diverse collection of diffusible molecules [41, 50]. Nevertheless, improvement in cell therapies is likely possible using biomaterials that do not completely recapitulate the satellite cell niche but instead incorporate key adhesive, mechanical, and soluble microenvironment cues (Table 2).

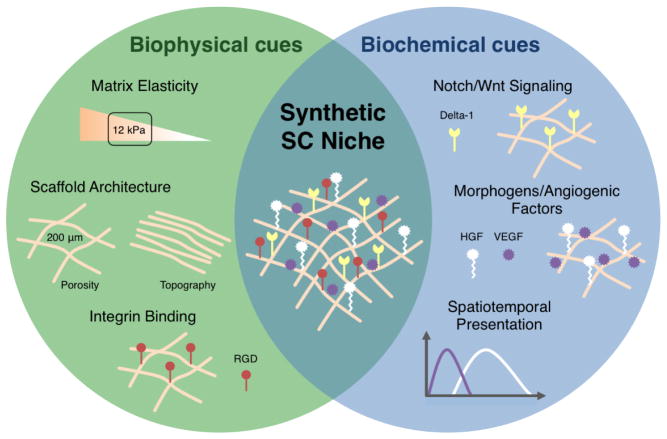

Figure 2. Design criteria for a biomaterial-based synthetic satellite cell niche.

Biophysical and biochemical cues can be used synergistically to create a synthetic satellite cell niche designed to optimize cell engraftment upon implantation. Biophysical cues, such as adhesive and mechanical signals, can dramatically affect cell survival and cell fate. For example, highly ordered material topography can be used to align myofibers and matrix stiffness can be used to promote self-renewal. Additionally, material carrier presentation of biochemical cues can lead to enhanced cell survival and participation in regeneration. Morphogens, cytokines, and angiogenic factors can be incorporated into a matrix through covalent coupling, physical entrapment, or ionic interactions in order to spatially and temporally control presentation. Key microenvironment cues are incorporated into an example synthetic satellite cell niche for cell transplantation.

Table 1. Signals in the muscle satellite cell niche.

The satellite cell niche is a highly complex microenvironment, containing extracellular matrix proteins, vascular and neural networks, various surrounding cells, and a diverse collection of diffusible molecules. Representative signals important to satellite cell self-renewal, migration, activation, and differentiation are provided along with a source and relevant receptor. Adapted from [4].

| Source | Signal | Receptor | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrix | Wnt | Frizzled | Cell fete |

| HGF | c-Met | Activation | |

| EGF | ErbBR | Activation | |

| bFGF | FGFR | Proliferation | |

| IGF-1 | IGFR-1 | Proliferation | |

| Myofiber | NO | No receptor | Quiescence |

| SDF-1 | CXCR4 | Migration | |

| VLA4 | VCAM | Fusion | |

| M-cadherin | M-cadherin | Fusion | |

| Basal Lamina | Laminin | Integrin | Quiescence |

| Satellite Cell | Myostatin | ACVR-2 | Self-renewal |

| Delta-1 | Notch | Selt-renewal | |

| BDNF | P75NTR | No differentiation | |

| Circulation | Myostatin | ACVR-2 | Self-renewal |

| Calcitonin | CTR | Quiescence | |

| IGF-1 | IGFR-1 | Proliferation | |

| Macrophage | TWEAK | Fn14 | Proliferation |

Table 2. Representative biomaterials for skeletal muscle tissue engineering.

Summary of natural and synthetic biomaterials commonly used for skeletal muscle tissue engineering [114–116]. Potentially useful properties and modifications relevant to the use of the material as a synthetic satellite cells niche are listed.

| Source | Material | Select Properties | Typical Modifications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Alginate | Tunable elasticity and porosity, controlled release (ionic interactions) | Ionic crosslinking, adhesion (RGD), degradation (oxidation) | 54–56, 61, 67, 70, 76, 82, 84, 85, 102 |

| Collagen | Adhesive, tunable porosity | Heat crosslinking | 88,90,91, 113, 114 | |

| ECM | Adhesive, architecture for cell guidance, promotes remodeling, immunomodulatory | Decellularization | 58, 59, 98 | |

| Fibrin | Adhesive, architecture for cell guidance (microthreads, micromolding), degradation | UV crosslinking | 69, 89, 92–96 | |

| Gelatin | Tunable elasticity | Genipin crosslinking | 57 | |

| Synthetic | Polyacrylamide | Tunable elasticity | Chemical crosslinking, adhesion (collagen-I) | 60, 62 |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Tunable elasticity | Chemical crosslinking, adhesion (laminin, RGD), degradation (PEG-maleimide) | 45, 48, 53 | |

| Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) | Tunable elasticity, porosity, and degradation | Adhesion (collagen-I) | 99, 115 |

Biophysical cues, such as adhesive and mechanical signals, presented by material carriers to transplanted cells dramatically affect cell survival and ultimately participation in regeneration. ECM adhesion is essential for the viability of anchorage dependent cells, such as normal epithelial and endothelial cells, that require integrin binding for survival [51]. In skeletal muscle, cell death following myoblast injection is partially mediated by anoikis, as bolus injections do not provide ECM contacts [52]. As a result, carrier materials developed for ex vivo expansion and cell transplantation incorporating adhesive cues that mimic natural binding in the satellite cell niche may be beneficial for skeletal muscle regeneration. The covalent modification of both natural and synthetic polymers with the cell adhesion ligand RGD, the cell binding domain of fibronectin, allows myoblasts to recognize and interact with their matrices [53, 54]. In vitro, RGD density, affinity, and nanoscale distribution have been shown to regulate skeletal myoblast proliferation and differentiation [55, 56]. Specifically, it has been determined that a minimal required RGD ligand density (36 nm spacing) is necessary for myoblast growth on alginate gels. Increased proliferation and differentiation is achievable by increasing ligand density and ligand affinity through the use of a cyclic peptide that more closely mimics the natural fibronectin motif [56]. RGD-coupled alginate has also been used to create cell-instructive scaffolds to enhance cell viability following transplantation in mice [57]. Complete ECM proteins, including collagen, laminin, and fibronectin, widely used as coatings for tissue culture plastic may also be of potential utility for the regulation of cell adhesion to material carriers. Collagen VI, a key component of the satellite cell niche, has been shown to improve the maintenance and survival of Pax7 expressing cells in vitro [58]. Interestingly, ECM from decellularized whole tissues has also been shown to modulate the immune system by promoting anti-inflammatory responses both in vitro and in vivo [59]. Recently, ECM scaffolds offering both mechanical and functional components have been used to promote skeletal muscle formation following volumetric muscle loss in mice and humans [60]. Due to the widespread biophysical and biochemical influence of the ECM, adhesive cues must be carefully selected when engineering implantable biomaterials for skeletal muscle regeneration.

Optimization of material carrier elasticity, may further promote muscle regeneration by partially overcoming inappropriate mechanical cues associated with injured or diseased muscle tissue. While healthy resting muscle tissue possesses an elasticity of 12 kPa, aging, injury, and disease have been shown to stiffen the tissue, leading to an elastic modulus >18 kPa [49]. Previously, matrix elasticity has been implicated in regulating mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) fate, with matrices that mimic striated muscle elasticity (8–17 kPa) promoting myogenic specification [61]. Material elastic modulus has also been shown to regulate primary myoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. When cultured on alginate scaffolds of varying elasticity (Young’s modulus of 1, 13, 45 kPa), primary myoblasts exhibited maximal adhesion and proliferation without terminal differentiation on gels possessing a physiologically relevant elastic modulus (13 kPa) [62]. Similarly, myotubes have been shown to differentiate optimally with maximum myosin striations emerging following myotube growth on materials of tissue-like elasticity (12 kPa gels) [63]. More recently, it has been demonstrated that matrix elasticity also plays an important role in specifically regulating satellite cell fate. During muscle regeneration in mice, collagen VI has been shown to regulate satellite cell activity through the maintenance of muscle elasticity. Satellite cells cultured on structures mimicking physiological elasticity (12 kPa) were more likely to be Pax7+MyoD−, and following intramuscular injection, were able to adopt a satellite cell localization and were more frequently associated with centrally nucleated fibers when compared to satellite cells cultured on softer substrates (7 kPa) [58]. Strikingly, porous hydrogels that contain the niche protein laminin, p38α/β mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitor, and mimic a rigidity similar to skeletal muscle tissue (12 kPa) have even been shown to contribute to the rejuvenation of aged stem cells [46, 49]. The preservation of satellite cell stemness on tissue-like modulus gels may result from cell shape alterations and the resulting cytoskeletal rearrangements and signaling modifications that follow [46]. Although the precise mechanisms remain to be elucidated, recent studies demonstrate that the actin cytoskeleton, RhoA-ROCK signaling, and nuclear lamin A are likely to play key roles in mechanotransduction [64, 65]. In general, materials that physiologically mimic the elastic modus of healthy muscle, in combination with other biophysical and biochemical cues, appear to be optimal for satellite cell maintenance, expansion, and regenerative participation upon transplantation.

Other biophysical cues, such as porosity and topography, are also often critical to transplanted cell survival and regenerative response. Due to their oxygen and nutrient requirements, few cell types tolerate distances greater than 200 μm from a blood vessel [66]. As a result, engineered matrix materials should incorporate a pore size and interconnectivity that allows for efficient delivery of nutrients and removal of waste. In general, macropore sizes ranging between 100 and 500 μm have been shown to be optimal for cell growth on scaffold materials [67]. The creation of macropores (400–500 μm) in alginate scaffolds was shown to significantly enhance primary myoblast viability and migration when compared to scaffolds containing micropores (10–20 μm) or nanopores [68]. In addition to scaffold porosity, materials possessing architectural features mimicking the aligned structures present in healthy skeletal muscle may also be of potential use in severe injuries requiring full-thickness replacement. Following moderate injury, satellite cells use the basement membrane of necrotic fibers as a scaffold to ensure a highly organized structure in the newly regenerated tissue [69]. However, severe injury resulting in volumetric muscle loss can lead to a defect that is void of these natural biophysical cues. In these cases, a scaffold that structurally approximates the organization of healthy muscle tissue may be advantageous. In general, primary myoblasts exhibit alignment when cultured on microgrooves, microfibers, and other micropatterned features [70]. Recently, bundles of fibrin microthreads were used to promote longitudinal growth and alignment of implanted human muscle progenitor cells, leading to the successful regeneration of partial thickness muscle defects [71].

Material carrier presentation of biochemical cues, such as growth factors, cytokines, and signaling ligands, to host and transplanted cells can also dramatically affect cell survival and participation in regeneration. The repair of injured skeletal muscle by therapies utilizing intramuscular growth factor injection has seen limited success [72, 73], most likely due to rapidly depleted local concentrations, inappropriate gradients, and/or loss of growth factor bioactivity. However, biochemical cues that regulate satellite cell function can be incorporated into a matrix through covalent coupling, physical entrapment, or ionic interactions in order to create a drug delivery device that allows localized and sustained exposure of satellite cells within the matrix and injured tissue. Growth factors of particular importance for skeletal muscle regeneration include HGF, IGF-1, VEGF, FGF, and PDGF, which appear during the normal regenerative process [40]. HGF has been described as the primary initiator of satellite cell activation and proliferation, and is essential for muscle progenitor migration to injured tissue during the early phase of muscle regeneration [74, 75]. IGF-1 has also been regarded as a central regulator of muscle repair, and has been shown to stimulate myoblast proliferation and myofiber hypertrophy in vitro and enhance muscle regeneration in vivo [76, 77]. Additionally, the potent angiogenic factor VEGF has been shown to enhance perfusion and muscle function of ischemic muscle tissue when released in a sustained and localized manner from an injectable hydrogel [72, 78]. The synergistic presentation of multiple biochemical cues that mimic normal in vivo presentation will likely lead to improved cell therapies. Previously, it has been shown that the combined presentation of HGF and FGF-2 significantly increased myoblast proliferation over the individual growth factors alone [79]. The combined delivery of myogenesis (IGF-1) and angiogenesis (VEGF) factors has also been shown to improve functional muscle regeneration following ischemic muscle injury, demonstrating the regenerative value of material carriers designed to impact both processes simultaneously [72]. Furthermore, signaling ligands covalently coupled to the matrix may provide an additional regenerative benefit. For instance, activation of notch signaling, through direct and immediate exposure to the notch ligand delta-1, maintains engraftment potential during ex vivo expansion [47]. This is consistent with previous reports that forced Notch activation promotes myoblast proliferation and inhibits differentiation in muscle progenitor cells in vitro and leads to improved muscle regeneration in aged mice [80, 81]. Furthermore, Wnt7a/Fzd7 signaling has been shown to drive the symmetric expansion of satellite stem cells [82]. When combined with fibronectin, Wnt7a signaling stimulates the expansion of satellite stem cells in regenerating muscle, resulting in a 147% increase in the number of satellite stem cells and 163% increase in the proportion of symmetric cell divisions when compared to controls [83]. Together, these findings suggest that appropriate biochemical cues should be incorporated into cell transplantation materials.

In a similar manner to the use of biomaterials for sustained drug delivery, appropriately designed materials may also be used to temporarily protect transplanted cells from a harsh wound environment, and promote the sustained release of functional cells into the surrounding tissue. Specifically, niche signals provided by the material can serve to activate the cells and continually promote outward migration to the site of injury (Figure 3). This cell delivery strategy is likely to be of particular relevance when regeneration of host muscle tissue is desired instead of replacement with a new graft. For example, a cell-instructive scaffold containing a combination of FGF-2 and HGF enhanced cell survival, prevented premature terminal differentiation of transplanted cells, and promoted their outward cell migration to repopulate the host lacerated TAs; this dramatically improved muscle regeneration [84]. Following cell release, it is highly desired that the materials biodegrade with kinetics that match the natural healing process of skeletal muscle (~4–6 weeks), as excessively rapid degradation may lead to open space filled by scar tissue and overly slow degradation may require invasive surgical removal in order to avoid a prolonged immune response [85, 86]. Material degradation has also been shown to promote the proliferation of primary myoblasts [62]. Recently, a biodegradable cell-releasing scaffold delivering IGF-1, VEGF, and primary myoblasts was able to regenerate muscle tissue in the context of a severe injury involving both myotoxin-mediated direct damage and regional ischemia [57]. Similar regenerative success was found following catheter-based introduction of a shape memory scaffold delivering IGF-1, VEGF, and primary myoblasts to myotoxin-ischemia injured muscle tissue, supporting the potential for this approach to be incorporated into minimally invasive treatment strategies [86, 87]. Importantly, this scaffold degraded gradually as it served as a delivery vehicle for growth factors and cells over a six week period, a timeframe matching the kinetics of normal muscle regeneration. In the future, the synergistic presentation of both biophysical and biochemical cues is likely to further enhance this approach to cell therapies.

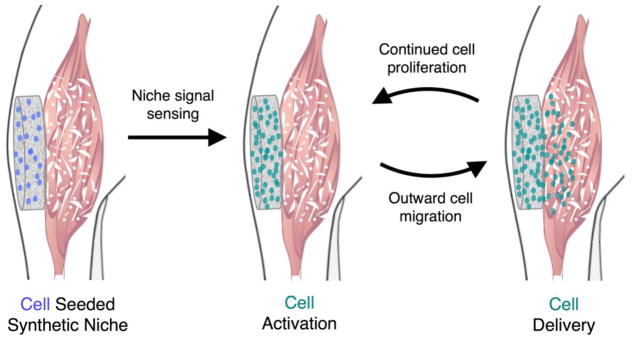

Figure 3. Biomaterial-based approach to sustained cell delivery.

A synthetic satellite cell niche can be designed to promote sustained cell delivery to injured muscle. Following implantation at a site of muscle damage, the engineered niche can provide protection from the harsh wound environment, and provide niche signals to promote cell activation leading to proliferation without terminal differentiation. Cell delivery to the injured area results from the subsequent outward migration of cells. Continued rounds of proliferation and outward migration lead to sustained cell delivery.

3.3 Tissue engineered skeletal muscle

Tissue engineered skeletal muscles may be of great clinical utility as therapeutic grafts to replace damaged skeletal muscle, and as in vitro model systems to study muscle biology. Allowing the cells within engineered tissues to contract against the scaffold can lead to highly organized, engineered muscle in vitro. In one approach, culturing myoblasts between two anchor posts acting as artificial tendons promotes tissue organization and leads to the generation of bioartificial muscle (BAM) tissues or myooids (Figure 4) [88, 89]. These BAMs, consisting of three-dimensional bundles of aligned and well-organized myofibers, have been shown to actively contract and generate force when stimulated, suggesting their functional similarity to natural muscles. Subsequently, BAMs have shown promise as an in vitro drug-screening platform for compounds that affect muscle strength [90], and genetically engineered BAMs were used successfully for sustained, local delivery of therapeutic proteins following transplantation [91, 92]. Specifically, the localized delivery of VEGF from BAMs was shown to rapidly increase capillary density within adjacent ischemic host muscle tissue, demonstrating the potential utility of tissue engineered muscles as a living drug delivery platform. Furthermore, BAMs have been shown to support effective clustering and maturation of acetylcholine receptors, suggesting an in vitro microenvironment that at least partially recapitulates physiological conditions supporting innervation [93]. In another approach, sacrificial outer molding was used to engineer tunable fascicle-like muscle tissues densely populated with highly aligned cells [94]. Recently, larger engineered muscle tissues displaying a three-dimensional organization resembling that of native tissue have been demonstrated using a cell/hydrogel micromolding approach [95, 96]. Strikingly, these engineered muscles consist of aligned, highly differentiated myofibers with Pax7+MyoD− associated quiescent satellite cells, and show a capacity to regenerate following cardiotoxin induced injury in vitro [97]. Implantation of these engineered muscles leads to vascularization and physiologically relevant contractile stress values that surpass those of undifferentiated myogenic cells, suggesting a regenerative value to the implantation of functional engineered muscle with a resident satellite cell niche. Transplantation of muscle tissues genetically engineered to express multiple proteins promoting muscle regeneration may be of great clinical utility in the future.

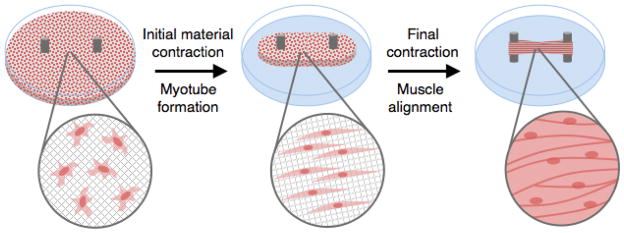

Figure 4. Tissue engineered skeletal muscle – bio-artificial muscle (BAM) formation.

Tissue engineered skeletal muscle tissues are of potential clinical utility as therapeutic grafts to replace lost muscle tissue. In one approach, BAMs are created when an ECM/cell composite is allowed to contract against two anchor posts acting as artificial tendons. Although cells are initially seeded in the material with random orientation, they align and fuse to form myotubes with time. Following contraction of the material, a contractile, highly organized muscle tissue consisting of aligned myofibers is generated.

Rapid integration with host nervous and vascular systems following transplantation will likely be key to the success of prefabricated tissues used to replace large volumes of muscle tissue. Rapid vascularization of engineered muscle is critical as cells more than a few hundred microns from a blood supply are typically metabolically inactive or necrotic due to limited nutrient diffusion [98]. In an attempt to improve oxygen supply and nutrient transport in thicker tissues, pre-vascularization of engineered skeletal muscle tissues has been explored with fibrin-based constructs seeded with HUVECs, fibroblasts, and myocytes. These constructs were able to form vessel-like networks in vitro that rapidly anastomose with host vessels, leading to the repair of small abdominal defects [99]. Recently, an engineered muscle flap with an autologous vascular pedicle was demonstrated [100]. Following transplantation to a full-thickness abdominal wall defect, the vascularized engineered muscle flap was able to undergo effective integration with the host tissue. Furthermore, reinnervation of a muscle graft is critical for the restoration of function. If left untreated, skeletal muscle denervation can lead to progressive deterioration of the affected fibers and loss of muscle function [101]. Reinnervation also plays a role in muscle fiber type specification [102]. While studies focusing on reinnervation of damaged skeletal muscle are limited, a recently described regulatory role for VEGF in nerve regeneration may foster additional studies [103]. Specifically, it was demonstrated that biomaterial-based VEGF delivery dramatically slowed neuron degeneration and promoted neuron regeneration in murine ischemic hindlimbs. The incorporation of VEGF and other biochemical cues into transplantable, engineered grafts may provide synergistic effects on myogenesis, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis.

4. SUMMARY AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

In early clinical trials, the intramuscular injection of cultured myoblasts was proven ineffective as a cell therapy for human myopathies, but much progress has been made in recent years to increase engraftment of transplanted, myogenic cells. The identification of several important biophysical and biochemical cues that regulate satellite cell fate has paved the way for the development of cell-instructive biomaterials that improve ex vivo culture, cell engraftment, and enhance regeneration. Material carriers that spatially mimic the satellite cell niche, biophysically and biochemically, may be of particular importance for the complete regeneration of severely damaged skeletal muscle.

In the future, further advances in cell therapy may result from more strict spatiotemporal regulation of biologic delivery. Many relevant growth factors have been found to exhibit pleiotropic effects. HGF, for example, has been found to promote muscle regeneration during early stage muscle regeneration, but to inhibit when injected during the differentiation stage of muscle repair, revealing that timing of HGF administration is critical for its role in muscle regeneration [104]. Spatial restriction of these factors to the scaffold through covalent coupling or the incorporation of small quantities that can only act very locally may be advantageous in some cases [84]. In addition, the sequential delivery of growth factors that regulate satellite cell activation and differentiation may lead to enhanced muscle regeneration. Spatiotemporal timing of cell delivery to coincide with specific phases of the innate inflammatory response may also lead to better cell survival and more successful therapies. As examples, improved myoblast engraftment was observed following coinjection of myogenic progenitors with anti-inflammatory macrophages in an mdx model [105] and proinflammatory macrophages in a cryoinjury model due to increased donor cell proliferation following injection [106]. Surprisingly, few studies have investigated the optimal time-point for cell transplantation by either injection or scaffold delivery to injured skeletal muscle. However, a recent study demonstrated reduced fibrosis, increased fiber diameter, and increased angiogenesis following delayed injection (4–7 days post injury) of muscle-derived stem cells (MDSCs) into contusion injured skeletal muscle [107]. In this injury model, these delayed time points coincide with the completion of acute inflammation and the beginning of angiogenesis. There has also been some investigation in the cardiac and neural regeneration fields. Specifically, cardiomyocytes have been transplanted to injured cardiac tissue immediately, 2 weeks, or 4 weeks following myocardial infarction [108]. Interestingly, cardiomyocyte transplantation was most successful when cells were injected 2 weeks following injury, a time point subsequent to the peak of the acute inflammatory reaction and prior to chronic inflammation promoting scar formation. The importance of the timing of neural stem cell delivery following peripheral nerve injury has also been examined [109]. The optimal time-point for cell transplantation was 1 week following nerve injury; cells transplanted immediately after injury suffered massive death attributed to the hostile microenvironment associated with acute inflammation. These studies suggest that postponed cell transplantation, timed to coincide with the resolution of acute inflammation, may be more advantageous than immediate treatment. Active material systems that provide on-demand release of cells and growth factors may be of great utility in cases where delayed biologic delivery is desired [110, 111].

Ultimately, it may be possible to eliminate the need for cell isolation and transplantation in muscle regeneration through the use of material systems that direct satellite cell behavior in situ. A material carrier that can recruit, activate, and redeploy satellite cells to injured skeletal muscle, analogous to recent systems that direct host immune cell behavior [112, 113], may allow one to eliminate the need for isolation and manipulation of cells, as that can lead to loss of regenerative potential.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Juhas M, Bursac N. Engineering skeletal muscle repair. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:880–886. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner NJ, Badylak SF. Regeneration of skeletal muscle. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:759–774. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarvinen TAHJ, Jarvinen TLN, Kaariainen M, Kalimo A, Jarvinen M. Muscle injuries - Biology and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:745–764. doi: 10.1177/0363546505274714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi CA, Pozzobon M, De Coppi P. Advances in musculoskeletal tissue engineering Moving towards therapy. Organogenesis. 2010;6:167–172. doi: 10.4161/org.6.3.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tedesco FS, Cossu G. Stem cell therapies for muscle disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:597–603. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328357f288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmieri B, Tremblay JP, Daniele L. Past, present and future of myoblast transplantation in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14:813–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCullagh KJ, Perlingeiro RC. Coaxing stem cells for skeletal muscle repair. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhawan J, Rando TA. Stem cells in postnatal myogenesis: molecular mechanisms of satellite cell quiescence, activation and replenishment. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciciliot S, Schiaffino S. Regeneration of Mammalian Skeletal Muscle: Basic Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:906–914. doi: 10.2174/138161210790883453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagers AJ, Conboy IM. Cellular and molecular signatures of muscle regeneration: current concepts and controversies in adult myogenesis. Cell. 2005;122:659–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauro A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961;9:493–495. doi: 10.1083/jcb.9.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Mathew SJ, Hutcheson DA, Kardon G. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3625–3637. doi: 10.1242/dev.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepper C, Partridge TA, Fan CM. An absolute requirement for Pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3639–3646. doi: 10.1242/dev.067595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambasivan R, Yao R, Kissenpfennig A, Van Wittenberghe L, Paldi A, Gayraud-Morel B, Guenou H, Malissen B, Tajbakhsh S, Galy A. Pax7-expressing satellite cells are indispensable for adult skeletal muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3647–3656. doi: 10.1242/dev.067587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Maltzahn J, Jones AE, Parks RJ, Rudnicki MA. Pax7 is critical for the normal function of satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16474–16479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307680110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerletti M, Jurga S, Witczak CA, Hirshman MF, Shadrach JL, Goodyear LJ, Wagers AJ. Highly efficient, functional engraftment of skeletal muscle stem cells in dystrophic muscles. Cell. 2008;134:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuang SH, Kuroda K, Le Grand F, Rudnicki MA. Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell. 2007;129:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montarras D, Morgan J, Collins C, Relaix F, Zaffran S, Cumano A, Partridge T, Buckingham M. Direct isolation of satellite cells for skeletal muscle regeneration. Science. 2005;309:2064–2067. doi: 10.1126/science.1114758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sacco A, Doyonnas R, Kraft P, Vitorovic S, Blau HM. Self-renewal and expansion of single transplanted muscle stem cells. Nature. 2008;456:502–506. doi: 10.1038/nature07384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Relaix F, Montarras D, Zaffran S, Gayraud-Morel B, Rocancourt D, Tajbakhsh S, Mansouri A, Cumano A, Buckingham M. Pax3 and Pax7 have distinct and overlapping functions in adult muscle progenitor cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:91–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocheteau P, Gayraud-Morel B, Siegl-Cachedenier I, Blasco MA, Tajbakhsh S. A subpopulation of adult skeletal muscle stem cells retains all template DNA strands after cell division. Cell. 2012;148:112–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day K, Paterson B, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. A distinct profile of myogenic regulatory factor detection within Pax7+ cells at S phase supports a unique role of Myf5 during posthatch chicken myogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1001–1009. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brack AS, Rando TA. Tissue-specific stem cells: lessons from the skeletal muscle satellite cell. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:504–514. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biressi S, Rando TA. Heterogeneity in the muscle satellite cell population. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins CA, Olsen I, Zammit PS, Heslop L, Petrie A, Partridge TA, Morgan JE. Stem cell function, self-renewal, and behavioral heterogeneity of cells from the adult muscle satellite cell niche. Cell. 2005;122:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zammit PS. All muscle satellite cells are equal, but are some more equal than others? J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2975–2982. doi: 10.1242/jcs.019661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuang S, Gillespie MA, Rudnicki MA. Niche regulation of muscle satellite cell self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cossu G, Tajbakhsh S. Oriented cell divisions and muscle satellite cell heterogeneity. Cell. 2007;129:859–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrari G, Cusella-De Angelis G, Coletta M, Paolucci E, Stornaiuolo A, Cossu G, Mavilio F. Muscle regeneration by bone marrow-derived myogenic progenitors. Science. 1998;279:1528–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dellavalle A, Sampaolesi M, Tonlorenzi R, Tagliafico E, Sacchetti B, Perani L, Innocenzi A, Galvez BG, Messina G, Morosetti R, Li S, Belicchi M, Peretti G, Chamberlain JS, Wright WE, Torrente Y, Ferrari S, Bianco P, Cossu G. Pericytes of human skeletal muscle are myogenic precursors distinct from satellite cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:255–267. doi: 10.1038/ncb1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dellavalle A, Maroli G, Covarello D, Azzoni E, Innocenzi A, Perani L, Antonini S, Sambasivan R, Brunelli S, Tajbakhsh S, Cossu G. Pericytes resident in postnatal skeletal muscle differentiate into muscle fibres and generate satellite cells. Nat Commun. 2011;2:499. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sampaolesi M, Blot S, D’Antona G, Granger N, Tonlorenzi R, Innocenzi A, Mognol P, Thibaud JL, Galvez BG, Barthelemy I, Perani L, Mantero S, Guttinger M, Pansarasa O, Rinaldi C, Cusella De Angelis MG, Torrente Y, Bordignon C, Bottinelli R, Cossu G. Mesoangioblast stem cells ameliorate muscle function in dystrophic dogs. Nature. 2006;444:574–579. doi: 10.1038/nature05282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell KJ, Pannerec A, Cadot B, Parlakian A, Besson V, Gomes ER, Marazzi G, Sassoon DA. Identification and characterization of a non-satellite cell muscle resident progenitor during postnatal development. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:257–U256. doi: 10.1038/ncb2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tidball JG, Villalta SA. Regulatory interactions between muscle and the immune system during muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol: Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1173–R1187. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00735.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen HX, Lusis AJ, Tidball JG. Null mutation of myeloperoxidase in mice prevents mechanical activation of neutrophil lysis of muscle cell membranes in vitro and in vivo. J Physiol. 2005;565:403–413. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.085506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saclier M, Yacoub-Youssef H, Mackey AL, Arnold L, Ardjoune H, Magnan M, Sailhan F, Chelly J, Pavlath GK, Mounier R, Kjaer M, Chazaud B. Differentially activated macrophages orchestrate myogenic precursor cell fate during human skeletal muscle regeneration. Stem Cells. 2013;31:384–396. doi: 10.1002/stem.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mounier R, Theret M, Arnold L, Cuvellier S, Bultot L, Goransson O, Sanz N, Ferry A, Sakamoto K, Foretz M, Viollet B, Chazaud B. AMPK alpha 1 Regulates Macrophage Skewing at the Time of Resolution of Inflammation during Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Cell Metab. 2013;18:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnold L, Henry A, Poron F, Baba-Amer Y, van Rooijen N, Plonquet A, Gherardi RK, Chazaud B. Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1057–1069. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chazaud B, Brigitte M, Yacoub-Youssef H, Arnold L, Gherardi R, Sonnet C, Lafuste P, Chretien F. Dual and beneficial roles of macrophages during skeletal muscle regeneration. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2009;37:18–22. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e318190ebdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ten Broek RW, Grefte S, Von den Hoff JW. Regulatory Factors and Cell Populations Involved in Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224:7–16. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin H, Price F, Rudnicki MA. Satellite Cells and the Muscle Stem Cell Niche. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:23–67. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slater CR, Schiaffino S. Innervation of Regenerating Muscle. In: Schiaffino S, Partridge T, editors. Skeletal Muscle Repair and Regeneration. Springer; 2008. pp. 303–334. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaariainen M, Jarvinen T, Jarvinen M, Rantanen J, Kalimo H. Relation between myofibers and connective tissue during muscle injury repair. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:332–337. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2000.010006332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laschke MW, Harder Y, Amon M, Martin I, Farhadi J, Ring A, Torio-Padron N, Schramm R, Rucker M, Junker D, Haufel JM, Carvalho C, Heberer M, Germann G, Vollmar B, Menger MD. Angiogenesis in tissue engineering: Breathing life into constructed tissue substitutes. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2093–2104. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smythe GM, Hodgetts SI, Grounds MD. Problems and solutions in myoblast transfer therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2001;5:33–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2001.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilbert PM, Havenstrite KL, Magnusson KE, Sacco A, Leonardi NA, Kraft P, Nguyen NK, Thrun S, Lutolf MP, Blau HM. Substrate elasticity regulates skeletal muscle stem cell self-renewal in culture. Science. 2010;329:1078–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.1191035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker MH, Loretz C, Tyler AE, Duddy WJ, Hall JK, Olwin BB, Bernstein ID, Storb R, Tapscott SJ. Activation of Notch signaling during ex vivo expansion maintains donor muscle cell engraftment. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2212–2220. doi: 10.1002/stem.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hall JK, Banks GB, Chamberlain JS, Olwin BB. Prevention of muscle aging by myofiber-associated satellite cell transplantation. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:57ra83. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cosgrove BD, Gilbert PM, Porpiglia E, Mourkioti F, Lee SP, Corbel SY, Llewellyn ME, Delp SL, Blau HM. Rejuvenation of the muscle stem cell population restores strength to injured aged muscles. Nat Med. 2014;20:255–264. doi: 10.1038/nm.3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boonen KJ, Post MJ. The muscle stem cell niche: regulation of satellite cells during regeneration. Tissue Eng, Part B. 2008;14:419–431. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frisch SM, Ruoslahti E. Integrins and anoikis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:701–706. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouchentouf M, Benabdallah BF, Rousseau J, Schwartz LM, Tremblay JP. Induction of anoikis following myoblast transplantation into SCID mouse muscles requires the Bit1 and FADD pathways. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1491–1505. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rowley JA, Madlambayan G, Mooney DJ. Alginate hydrogels as synthetic extracellular matrix materials. Biomaterials. 1999;20:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salimath AS, Garcia AJ. Biofunctional hydrogels for skeletal muscle constructs. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/term.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rowley JA, Mooney DJ. Alginate type and RGD density control myoblast phenotype. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60:217–223. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boontheekul T, Kong HJ, Hsiong SX, Huang YC, Mahadevan L, Vandenburgh H, Mooney DJ. Quantifying the relation between bond number and myoblast proliferation. Faraday Discuss. 2008;139:53–70. doi: 10.1039/b719928g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borselli C, Cezar CA, Shvartsman D, Vandenburgh HH, Mooney DJ. The role of multifunctional delivery scaffold in the ability of cultured myoblasts to promote muscle regeneration. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8905–8914. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Urciuolo A, Quarta M, Morbidoni V, Gattazzo F, Molon S, Grumati P, Montemurro F, Tedesco FS, Blaauw B, Cossu G, Vozzi G, Rando TA, Bonaldo P. Collagen VI regulates satellite cell self-renewal and muscle regeneration. Nat Commun. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fishman JM, Lowdell MW, Urbani L, Ansari T, Burns AJ, Turmaine M, North J, Sibbons P, Seifalian AM, Wood KJ, Birchall MA, De Coppi P. Immunomodulatory effect of a decellularized skeletal muscle scaffold in a discordant xenotransplantation model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:14360–14365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213228110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sicari BM, Rubin JP, Dearth CL, Wolf MT, Ambrosio F, Boninger M, Turner NJ, Weber DJ, Simpson TW, Wyse A, Brown EH, Dziki JL, Fisher LE, Brown S, Badylak SF. An acellular biologic scaffold promotes skeletal muscle formation in mice and humans with volumetric muscle loss. Science translational medicine. 2014;6:234ra258. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boontheekul T, Hill EE, Kong HJ, Mooney DJ. Regulating myoblast phenotype through controlled gel stiffness and degradation. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1431–1442. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Engler AJ, Griffin MA, Sen S, Bonnemann CG, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Myotubes differentiate optimally on substrates with tissue-like stiffness: pathological implications for soft or stiff microenvironments. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:877–887. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swift J, Ivanovska IL, Buxboim A, Harada T, Dingal PC, Pinter J, Pajerowski JD, Spinler KR, Shin JW, Tewari M, Rehfeldt F, Speicher DW, Discher DE. Nuclear lamin-A scales with tissue stiffness and enhances matrix-directed differentiation. Science. 2013;341:1240104. doi: 10.1126/science.1240104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guilak F, Cohen DM, Estes BT, Gimble JM, Liedtke W, Chen CS. Control of stem cell fate by physical interactions with the extracellular matrix. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaully T, Kaufman-Francis K, Lesman A, Levenberg S. Vascularization--the conduit to viable engineered tissues. Tissue engineering Part B, Reviews. 2009;15:159–169. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ikada Y. Challenges in tissue engineering. J R Soc, Interface. 2006;3:589–601. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hill E, Boontheekul T, Mooney DJ. Designing scaffolds to enhance transplanted myoblast survival and migration. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1295–1304. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Serrano AL, Munoz-Canoves P. Regulation and dysregulation of fibrosis in skeletal muscle. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:3050–3058. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang NF, Lee RJ, Li S. Engineering of aligned skeletal muscle by micropatterning. American journal of translational research. 2010;2:43–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Page RL, Malcuit C, Vilner L, Vojtic I, Shaw S, Hedblom E, Hu J, Pins GD, Rolle MW, Dominko T. Restoration of skeletal muscle defects with adult human cells delivered on fibrin microthreads. Tissue engineering Part A. 2011;17:2629–2640. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Borselli C, Storrie H, Benesch-Lee F, Shvartsman D, Cezar C, Lichtman JW, Vandenburgh HH, Mooney DJ. Functional muscle regeneration with combined delivery of angiogenesis and myogenesis factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3287–3292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903875106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hammers DW, Sarathy A, Pham CB, Drinnan CT, Farrar RP, Suggs LJ. Controlled release of IGF-I from a biodegradable matrix improves functional recovery of skeletal muscle from ischemia/reperfusion. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:1051–1059. doi: 10.1002/bit.24382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Webster MT, Fan CM. c-MET Regulates Myoblast Motility and Myocyte Fusion during Adult Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sisson TH, Nguyen MH, Yu B, Novak ML, Simon RH, Koh TJ. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator increases hepatocyte growth factor activity required for skeletal muscle regeneration. Blood. 2009;114:5052–5061. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shansky J, Creswick B, Lee P, Wang X, Vandenburgh H. Paracrine release of insulin-like growth factor 1 from a bioengineered tissue stimulates skeletal muscle growth in vitro. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1833–1841. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pelosi L, Giacinti C, Nardis C, Borsellino G, Rizzuto E, Nicoletti C, Wannenes F, Battistini L, Rosenthal N, Molinaro M, Musaro A. Local expression of IGF-1 accelerates muscle regeneration by rapidly modulating inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. FASEB J. 2007;21:1393–1402. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7690com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Silva EA, Mooney DJ. Spatiotemporal control of vascular endothelial growth factor delivery from injectable hydrogels enhances angiogenesis. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:590–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sheehan SM, Allen RE. Skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation in response to members of the fibroblast growth factor family and hepatocyte growth factor. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:499–506. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199912)181:3<499::AID-JCP14>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Smythe GM, Rando TA. Notch-mediated restoration of regenerative potential to aged muscle. Science. 2003;302:1575–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1087573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Conboy IM, Rando TA. The regulation of Notch signaling controls satellite cell activation and cell fate determination in postnatal myogenesis. Dev Cell. 2002;3:397–409. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Le Grand F, Jones AE, Seale V, Scime A, Rudnicki MA. Wnt7a activates the planar cell polarity pathway to drive the symmetric expansion of satellite stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bentzinger CF, Wang YX, von Maltzahn J, Soleimani VD, Yin H, Rudnicki MA. Fibronectin regulates Wnt7a signaling and satellite cell expansion. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hill E, Boontheekul T, Mooney DJ. Regulating activation of transplanted cells controls tissue regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2494–2499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506004103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gates C, Huard J. Management of skeletal muscle injuries in military personnel. Oper Techn Sport Med. 2005;13:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang L, Cao L, Shansky J, Wang Z, Mooney D, Vandenburgh H. Minimally invasive approach to the repair of injured skeletal muscle with a shape-memory scaffold. Mol Ther. 2014 doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang L, Shansky J, Borselli C, Mooney D, Vandenburgh H. Design and Fabrication of a Biodegradable, Covalently Crosslinked Shape-Memory Alginate Scaffold for Cell and Growth Factor Delivery. Tissue Eng, Part A. 2012;18:2000–2007. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dennis RG, Kosnik PE. 2nd, Excitability and isometric contractile properties of mammalian skeletal muscle constructs engineered in vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2000;36:327–335. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2000)036<0327:EAICPO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shansky J, Del Tatto M, Chromiak J, Vandenburgh H. A simplified method for tissue engineering skeletal muscle organoids in vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1997;33:659–661. doi: 10.1007/s11626-997-0118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vandenburgh H, Shansky J, Benesch-Lee F, Barbata V, Reid J, Thorrez L, Valentini R, Crawford G. Drug-screening platform based on the contractility of tissue-engineered muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:438–447. doi: 10.1002/mus.20931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lu Y, Shansky J, Del Tatto M, Ferland P, Wang X, Vandenburgh H. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor secreted from tissue-engineered bioartificial muscles promotes localized angiogenesis. Circulation. 2001;104:594–599. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.092215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Powell C, Shansky J, Del Tatto M, Forman DE, Hennessey J, Sullivan K, Zielinski BA, Vandenburgh HH. Tissue-engineered human bioartificial muscles expressing a foreign recombinant protein for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:565–577. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang L, Shansky J, Vandenburgh H. Induced Formation and Maturation of Acetylcholine Receptor Clusters in a Defined 3D Bio-Artificial Muscle. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:397–403. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8412-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Neal D, Sakar MS, Ong LL, Harry Asada H. Formation of elongated fascicle-inspired 3D tissues consisting of high-density, aligned cells using sacrificial outer molding. Lab Chip. 2014;14:1907–1916. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00023d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bian W, Bursac N. Engineered skeletal muscle tissue networks with controllable architecture. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1401–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bian W, Liau B, Badie N, Bursac N. Mesoscopic hydrogel molding to control the 3D geometry of bioartificial muscle tissues. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1522–1534. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Juhas M, Engelmayr GC, Jr, Fontanella AN, Palmer GM, Bursac N. Biomimetic engineered muscle with capacity for vascular integration and functional maturation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5508–5513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402723111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Colton CK. Implantable biohybrid artificial organs. Cell Transplant. 1995;4:415–436. doi: 10.1177/096368979500400413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Koffler J, Kaufman-Francis K, Shandalov Y, Egozi D, Pavlov DA, Landesberg A, Levenberg S. Improved vascular organization enhances functional integration of engineered skeletal muscle grafts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14789–14794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017825108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shandalov Y, Egozi D, Koffler J, Dado-Rosenfeld D, Ben-Shimol D, Freiman A, Shor E, Kabala A, Levenberg S. An engineered muscle flap for reconstruction of large soft tissue defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:6010–6015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402679111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Borisov AB, Dedkov EI, Carlson BM. Interrelations of myogenic response, progressive atrophy of muscle fibers, and cell death in denervated skeletal muscle. Anat Rec. 2001;264:203–218. doi: 10.1002/ar.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mendler L, Pinter S, Kiricsi M, Baka Z, Dux L. Regeneration of reinnervated rat soleus muscle is accompanied by fiber transition toward a faster phenotype. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:111–123. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7322.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shvartsman D, Storrie-White H, Lee K, Kearney C, Brudno Y, Ho N, Cezar C, McCann C, Anderson E, Koullias J, Tapia JC, Vandenburgh H, Lichtman JW, Mooney DJ. Sustained delivery of VEGF maintains innervation and promotes reperfusion in ischemic skeletal muscles via NGF/GDNF signaling. Mol Ther. 2014 doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Miller KJ, Thaloor D, Matteson S, Pavlath GK. Hepatocyte growth factor affects satellite cell activation and differentiation in regenerating skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C174–181. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.1.C174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lesault PF, Theret M, Magnan M, Cuvellier S, Niu Y, Gherardi RK, Tremblay JP, Hittinger L, Chazaud B. Macrophages improve survival, proliferation and migration of engrafted myogenic precursor cells into MDX skeletal muscle. PloS One. 2012;7:e46698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bencze M, Negroni E, Vallese D, Yacoub-Youssef H, Chaouch S, Wolff A, Aamiri A, Di Santo JP, Chazaud B, Butler-Browne G, Savino W, Mouly V, Riederer I. Proinflammatory macrophages enhance the regenerative capacity of human myoblasts by modifying their kinetics of proliferation and differentiation. Mol Ther. 2012;20:2168–2179. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ota S, Uehara K, Nozaki M, Kobayashi T, Terada S, Tobita K, Fu FH, Huard J. Intramuscular transplantation of muscle-derived stem cells accelerates skeletal muscle healing after contusion injury via enhancement of angiogenesis. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1912–1922. doi: 10.1177/0363546511415239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li RK, Mickle DA, Weisel RD, Rao V, Jia ZQ. Optimal time for cardiomyocyte transplantation to maximize myocardial function after left ventricular injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lin S, Xu L, Hu S, Zhang C, Wang Y, Xu J. Optimal time-point for neural stem cell transplantation to delay denervated skeletal muscle atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2013;47:194–201. doi: 10.1002/mus.23447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhao X, Kim J, Cezar CA, Huebsch N, Lee K, Bouhadir K, Mooney DJ. Active scaffolds for on-demand drug and cell delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:67–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007862108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]