Abstract

Cocaine self-administration disturbs intracellular signaling in prefrontal cortical neurons that regulate neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens. The deficits in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) signaling change over time, resulting in different neuroadaptations during early withdrawal from cocaine self-administration than after one or more weeks of abstinence. Within the first few hours of withdrawal, there is a marked decrease in tyrosine phosphorylation of critical intracellular and membrane-bound proteins in the dmPFC that include ERK/MAP kinase and the NMDA receptor subunits, GluN1 and GluN2B. These changes are accompanied by a marked increase in STEP tyrosine phosphatase activation. Simultaneously, ERK and PKA-dependent synapsin phosphorylation in presynaptic terminals of the nucleus accumbens is increased that may have a destabilizing impact on glutamatergic transmission. Infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) into the dmPFC immediately following a final session of cocaine self-administration blocks the cocaine-induced changes in phosphorylation and attenuates relapse to cocaine seeking for as long as three weeks. The intra-dmPFC BDNF infusion also prevents cocaine-induced deficits in prefronto-accumbens glutamatergic transmission that are implicated in cocaine seeking. Thus, intervention with BDNF in the dmPFC during early withdrawal has local and distal effects in target areas that are critical to mediating cocaine-induced neuroadaptations that lead to cocaine seeking.

Keywords: BDNF, ERK MAP kinase, glutamate, nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex, reinstatement

1. Therapeutic intervention during early withdrawal for cocaine addiction

Development of pharmacotherapies for substance use disorders (SUDs) targets all phases of the addictive process: intoxication, withdrawal preceding abstinence initiation, use reduction, and maintenance of relapse prevention (Ross and Peselow, 2009). However, there is no FDA-approved pharmacological agent that effectively prevents any phase of the addiction process (Skolnick and Volkow, 2012; Volkow and Skolnick, 2012). Preclinical evidence indicates that early withdrawal is a critical period in which to intervene with BDNF to prevent persistent relapse to cocaine-seeking (Berglind et al., 2007; Whitfield et al., 2011). However, despite BDNF’s enduring effects on cocaine-seeking when infused into the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), it is not a good candidate for therapy because it is expensive and does not cross the blood-brain barrier effectively. In contrast, there are systemically-active SUD medication candidates that target cocaine-induced disturbances in glutamate transmission with the aim of strengthening fronto-striatal inhibitory control over relapse to cocaine-seeking. These include N-acetyl-cysteine (Baker et al., 2003; Kupchik et al., 2011), ceftriaxone (Knackstedt et al., 2010; Sondheimer and Knackstedt, 2011; Ward et al., 2011), and modulators of metabotropic glutamate receptors (Gass and Olive, 2008; Hao et al., 2010). However, all of these glutamate-related ligands have been administered immediately before a drug-seeking or –taking test in animals after different periods of abstinence. In contrast to intervention after neuroadaptations have emerged during abstinence from cocaine self-administration (SA) (Kalivas, 2009), early intervention has the potential advantage of preventing the emergence of long-term drug-induced neuroadaptations that promote persistent relapse to drug-seeking. Moreover, early intervention underscores the dynamic nature of cocaine-induced changes over time and suggests that treatment based on strengthening prefrontal inhibitory control over drug-seeking may be most effective when the intervention occurs before impulsive drug-seeking becomes compulsive. Thus, identification of treatments that prevent cocaine-induced neuroadaptations early in withdrawal represents a novel approach that may prevent escalation of drug use and reduce the suffering and burden of SUDs in human cocaine abusers.

2. The significance of altered PFC functioning during early withdrawal from cocaine

The PFC is a major brain executor of goal-directed behaviors and impulse control, with several subdivisions that selectively mediate responses to different environmental stimuli relevant to cocaine abuse (Capriles et al., 2003; Goldstein and Volkow, 2002; Jentsch and Taylor, 1999; McFarland and Kalivas, 2001; Peters et al., 2008; Volkow and Fowler, 2000). Chronic human cocaine users are vulnerable to persistent drug-seeking that is linked to reduced metabolic activity in the PFC during abstinence (Baler and Volkow, 2006; Goldstein and Volkow, 2002; Hester and Garavan, 2004) and increased metabolic activity in response to cues associated with cocaine (Childress et al., 1999). Animals with a cocaine SA history also have reduced activity in the PFC during cocaine withdrawal (Porrino and Lyons, 2000; McGinty et al., 2010) and increased immediate early gene expression elicited by relapse to cocaine-seeking (Hearing et al., 2008; Zavala et al., 2008; Cruz et al., 2014).

Cocaine-induced deficits in the structure and/or function of the PFC have been demonstrated after both short and long access preclinical models (Briand et al., 2008; George et al., 2008; Kalivas 2009; Whitfield et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2013). A common feature arising out of these reports is that PFC deficits become greater and last longer as the duration of cocaine intake escalates. In fact, it has been proposed that intervention to strengthen prefrontal inhibitory control when goal-directed behavior is still intact and escalation to compulsive drug-seeking and negative affective states have not yet solidified may be the most effective time to begin treatment and prevent the transition to addiction (Koob and Volkow, 2009; George and Koob, 2010). The ability to strengthen PFC inhibitory control depends on a better understanding of how cocaine triggers dysfunction of glutamatergic neurons that project from PFC to NAc, a dysfunction that emerges after short access to cocaine in animal models. Reinstatement of drug-seeking induced by conditioned cues or a drug prime in rats with a cocaine SA history is driven in large part by a suppression of basal extracellular glutamate levels that is associated with an excessive cocaine prime-induced extracellular overspill of glutamate in the NAc core (McFarland et al., 2003). Basal glutamate levels in the NAc are suppressed as early as 24 hr after a short access cocaine SA regimen and the suppression persists for weeks (Lutgen et al., 2012).

Few other studies have investigated changes in the PFC and NAc during cocaine SA or early withdrawal in rodents. However, two stand out because they provide important clues about the effects of repeated cocaine SA on glutamatergic transmission. First, Sun and Rebec (2006) demonstrated that repeated short access (2 hr daily) cocaine SA decreased baseline firing (from day 1) but increased the duration of bursting (from session 10–21) by pyramidal neurons in the PFC, suggesting that alterations in PFC excitability and sensitivity to repeated short access cocaine emerge early during exposure and persist. Second, Miguens and colleagues (2008) demonstrated that, once cocaine SA is established, but not after acute i.v. cocaine administration, extracellular glutamate levels in the NAc increase markedly toward the end of a daily 2-hr session and remain elevated for at least 40 min after the end of SA (the maximum duration of the measurements). These data suggest that glutamate uptake mechanisms are overwhelmed by repeated cocaine infusions so that glutamate overflows into the extrasynaptic space and the effects endure beyond the last cocaine infusion (Kalivas, 2009).

3. Cocaine SA dephosphorylates ERK and GluN2B in the PFC

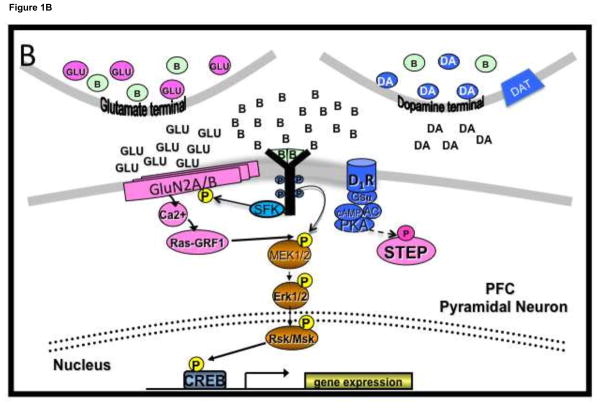

ERK phosphorylation is a reliable biomarker associated with combined dopamine and glutamate receptor activation that causes a transient, NMDA receptor-mediated spike in Ca2+ influx (Fiore et al., 1993). Intermittent cocaine exposure causes this type of ERK phosphorylation in the striatum that is associated with the rewarding and memory consolidating properties of cocaine (Miller et al., 2007; Valjent et al., 2000, 2005). However, prolonged exposure to glutamate causes ERK dephosphorylation by causing a further rise in Ca2+ that activates protein phosphatase 2B (PP2B) (Mulholland et al., 2008; Paul and Connor, 2010). PP2B dephosphorylates and activates PP1 that dephosphorylates and thereby activates the protein tyrosine phosphatase, STEP (striatal-enriched tyrosine phosphatase), which then dephosphorylates ERK in cortical cultures (Paul and Connor, 2010). This cascade is blocked by NMDA receptor GluN2B subtype-selective antagonists. Interestingly, the NMDA-induced ERK shut-off in cortical cultures is over-ridden by BDNF, the effects of which are linked to synaptic strengthening (Mulholland et al., 2008). We have found that within 2 hr of the end of cocaine SA, ERK and CREB in the dmPFC are profoundly dephosphorylated and a single BDNF infusion into dmPFC immediately after the end of SA prevents this deactivation (Whitfield et al., 2011). Thus, it is possible that prolonged extracellular glutamate causes overstimulation of NMDA receptors, triggering the critical shut-off of ERK phosphorylation in the dmPFC that contributes to relapse, a process that is reversed by intra-dmPFC infusion of BDNF immediately after the last cocaine SA session (Figure 1). This hypothesis is consistent with our more recent data demonstrating that 2 hr after the end of cocaine SA, not only are ERK and CREB dephosphorylated but STEP is activated and GluN2B, also a substrate of STEP, is dephosphorylated at Y1472 (Sun et al., 2013). The total amount of GluN2B is also decreased in dmPFC, suggesting that during early withdrawal from repeated cocaine exposure, there is a compensatory reduction in the total number of GluN2B-containing receptors as well as fewer GluN2B receptors on the cell surface of dmPFC neurons because phosphorylation of the Y1472 site is critical for surface expression of NMDA receptors (Lau and Huganir, 1995; Goebel-Goody et al., 2008). Alternatively GluN2A may be dephosphorylated by STEP at Y1325 as selective inhibition of GluN2A receptors also attenuates cocaine-seeking (Go et al., in prep). The link between TrkB receptors and NMDA receptors is most likely via activation of Src family kinases (SFKs) known to phosphorylate Y1472 in GluN2B and Y1325 in GluN2A (Salter and Kalia, 2004) as a SFK inhibitor, PP2, also attenuates cocaine-seeking (Barry et al., in prep).

Figure 1.

Possible substrates underlying dephosphorylation of ERK and CREB in PFC during early withdrawal from cocaine self-administration (A) and restoration of phosphorylation by intra-dmPFC BDNF infusion (B). A. Prolonged extra-synaptic NMDA receptor activation causes a sharp rise in Ca2+ that activates PP2B, and, likely via DARPP-32 dephosphorylation, disinhibits PP1 that dephosphorylates and thereby activates the protein tyrosine phosphatase, STEP, that then dephosphorylates ERK. B. An intra-dmPFC BDNF infusion immediately after the last cocaine SA session enhances ERK and CREB phosphorylation in a synaptic NMDA receptor-dependent manner likely mediated by a Src family kinase. AC=adenylyl cyclase, B=BDNF, DA=dopamine, D1R=dopamine 1 receptor, D32=DARPP32, Glu=glutamate, P=phosphate, PP1=protein phosphatase 1, PP2B=protein phosphatase 2B, SFK= Src family kinase, STEP=striatal-enriched phosphatase. Fuzzy postsynaptic membrane=postsynaptic density.

Whereas ERK is activated almost exclusively by the MAPK, MEK1/2, it is a substrate for at least three different phosphatase families: (1) the protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP-Tonks, 2006), (2) the serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A-Alessi et al., 1995), and (3) the dual-specificity map kinase phosphatases (MKP-Owens and Keyes 2007). Based on extensive research by Lombroso and colleagues, calcineurin-activated STEP appears to be the most likely mediator of the NMDA receptor-mediated ERK shut-off (Braithwaite et al., 2006b; Paul et al., 2003; Paul and Connor, 2010) because it is blocked by GluN2B antagonists and the calcineurin inhibitor, cyclosporin A. Further, STEP61 (an isoform of STEP with MW 61kDa) is well-expressed in PFC pyramidal neurons (Boulanger et al., 1995) and STEP activation can be detected by a decrease in its phosphorylated (resting) state. When activated STEP binds to and selectively dephosphorylates the Y1472 site in the GluN2B receptor subunit and dephosphorylates the Src family kinase, fyn, that phosphorylates GluN2B at that site, endocytosis and LTD are facilitated (Braithwaite et al., 2006a,b). Therefore, an attractive hypothesis is that GluN2B/PP2B/PP1-activated STEP mediates the cocaine SA-induced ERK shutoff in the dmPFC. In support of this hypothesis, phospho-STEP61-immunoreactivity is decreased in the dmPFC 2 hr after the end of cocaine SA, suggesting that STEP is activated and is a likely mediator of the cocaine SA-induced ERK shutoff in the dmPFC during early withdrawal (Sun et al., 2013). In contrast, phospho-Y307-PP2A is elevated 2 hr after the end of cocaine SA (Sun et al., 2013), suggesting that PP2A is inactivated (Mao et al., 2005) and does not mediate the cocaine SA-induced ERK shutoff.

4. Cocaine SA increases synapsin I phosphorylation in nucleus accumbens

We have previously demonstrated that one intra-dmPFC BNDF infusion immediately following the last cocaine SA session normalized the cocaine-induced disturbance of glutamate transmission in the NAc after extinction and a cocaine prime that is associated with cocaine-seeking (Berglind et al., 2009). However, the molecular mechanism mediating the BDNF effect on cocaine-induced alterations in extracellular glutamate levels is unknown. Because BDNF activates ERK phosphorylation, we searched for ERK targets that regulate glutamate release and chose to investigate the phosphorylation state of synapsins, presynaptic proteins that mediate synaptic vesicle mobilization, that are phosphorylated at several sites by different kinases. Two hr after SA ended, phospho-synapsin Ser9 (PKA/CAMKI) and phospho-synapsin Ser62/67 (ERK), but not phospho-synapsin Ser603 (CAMKII), were increased in the NAc of cocaine SA rats and at 22 hr, only phospho-synapsin Ser9 was still elevated (Sun et al., in press). The elevated phospho-synapsin at both timepoints was attenuated by an intra-dmPFC BDNF infusion immediately after the end of cocaine SA. BDNF also reduced cocaine SA withdrawal-induced phosphorylation of the protein phosphatase 2A C-subunit (PP2Ac) at both time points, suggesting that BDNF disinhibits PP2Ac, consistent with p-synapsin Ser9 dephosphorylation. Further, co-immunoprecipitation demonstrated that PP2Ac and synapsin are associated in a protein-protein associated complex that was reduced after 2 hr of withdrawal from cocaine SA and reversed by BDNF. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that BDNF normalizes the cocaine SA-induced elevation of phospho-synapsin in NAc that may underlie a disturbance in the probability of neurotransmitter release or represent a compensatory neuroadaptation in response to the hypofunction within the PFC-NAc pathway during cocaine withdrawal.

6. PKA-dependent CREB and GluA1 Ser845 phosphorylation is upregulated in dmPFC after one week of abstinence and reversed by relapse

Abstinence from cocaine SA is associated with neuroadaptations in the dmPFC and NAc that are implicated in cocaine-induced neuronal plasticity and relapse to drug-seeking. Alterations in PKA signaling are prominent in medium spiny neurons in the NAc after repeated cocaine exposure but little is known about similar changes in the PFC. Because cocaine SA induces disturbances in glutamatergic transmission in the PFC-NAc pathway, we examined whether dysregulation of PKA-mediated molecular targets in PFC-NAc neurons occurs during abstinence and, if so, whether it contributes to cocaine seeking. We measured the phosphorylation of CREB (Ser133) and GluA1 (Ser845) in the dmPFC and synapsin I (Ser9, Ser62/67, Ser603), in the NAc after 7 days of abstinence from cocaine SA with or without cue-induced cocaine-seeking. We also evaluated whether infusion of the PKA inhibitor, 8-bromo-Rp-cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphorothioate (Rp-cAMPs), into the dmPFC after abstinence would affect cue-induced cocaine-seeking and PKA-regulated phosphoprotein levels. Seven days of forced abstinence increased the phosphorylation of CREB and GluA1 in the dmPFC and synapsin I (Ser9 but not Ser 62/67 or Ser603) in the NAc. Induction of these phosphoproteins was reversed by a cue-induced relapse test of cocaine-seeking (Sun et al., 2014). Bilateral intra-dmPFC Rp-cAMPs rescued abstinence-elevated PKA-mediated phosphoprotein levels in the dmPFC and NAc and suppressed cue-induced relapse. Thus, by inhibiting abstinence-induced PKA molecular targets, relapse reverses neuroadaptations in the dmPFC after one week of abstinence.

7. Conclusions

Cocaine-induced disturbances in dmPFC signaling during early withdrawal from cocaine self-administration differ from those that emerge after one or more weeks of abstinence. Within the first few hours of withdrawal, there is a marked decrease in tyrosine phosphorylation of critical intracellular and membrane-bound proteins in the dmPFC that include ERK MAP kinase and the NMDA receptor subunits, GluN1 and GluN2B that are likely mediated by STEP tyrosine phosphatase. Further destabilization of dmPFC-NAc transmission may be indicated by ERK- and PKA-dependent synapsin phosphorylation in presynaptic terminals of the NAc. Infusion of BDNF into the dmPFC immediately following a final session of cocaine self-administration blocks the cocaine-induced changes in phosphorylation and attenuates relapse to cocaine seeking. The intra-dmPFC BDNF infusion also prevents cocaine-induced deficits in dmPFC-NAc glutamatergic transmission that are implicated in cocaine seeking. However, cocaine-induced neuroadaptations in PKA-dependent signaling occur after one week of abstinence, when BDNF infusions are no longer effective (Berglind et al., 2007), that are normalized by a PKA inhibitor and relapse. Thus, restoring synaptic activity in the dmPFC requires different types of intervention at different intervals during abstinence in order to decrease susceptibility to relapse in animals with a history of cocaine exposure.

Highlights.

Cocaine induces signaling deficits in corticostriatal circuitry during early withdrawal

STEP is implicated in cocaine-induced dephosphorylation in the prefrontal cortex

BDNF restores phosphorylation in the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens

Cocaine induces PKA-dependent signaling in corticostriatal circuitry that is reversed by relapse after one week of abstinence

Acknowledgments

Funded by P50 DA015369 and RO1 DA033479 (JFM),

Abbreviations

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- ERK

extracellular-regulated kinase

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- MEK

mitogen activated extracellular-regulated protein kinase

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- dmPFC

dorsomedial prefrontal cortex

- PKA

protein kinase A

- SA

self-administration

- STEP

striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase

- SUD

substance use disorder

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alessi DR, Gomez N, Moorhead G, Lewis T, Keyes SM, Cohen P. Inactivation of p42 MAP kinase by protein phosphatase 2A and a protein tyrosine phosphatase regulates, but not CL100, in various cell lines. Curr Biol. 1995;5:283–295. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, McFarland K, Lake RW, Shen H, Tang XC, Toda S, Kalivas PW. Neuroadaptations in cysteine-glutamate exchange underlie cocaine relapse. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:743–749. doi: 10.1038/nn1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baler RD, Volkow ND. Drug addiction; the neurobiology of disrupted self control. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind WJ, See RE, Fuchs RA, Ghee SM, Whitfield TW, Miller SW, McGinty JF. A BDNF infusion into the medial prefrontal cortex suppresses cocaine-seeking in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:757–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind WJ, Whitfield TW, LaLumiere R, Kalivas PW, McGinty JF. A single intra-PFC infusion of BDNF prevents cocaine-Induced alterations in extracellular glutamate within the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3715–3719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5457-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger LM, Lombroso PJ, Raghunathan A, During MJ, Wahle P, Naegle JR. Cellular and molecular characterization of a brain-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1532–1544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01532.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SP, Adkisson A, Leung J, Nava A, Masterson B, Urfer R, Oksenberg D, Nikolich K. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking and function by striatal-enriched tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) EurJ Neurosci. 2006a;23:2847–2856. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SP, Paul S, Nairn AC, Lombroso PJ. Synaptic plasticity: one STEP at a time. Trends in Neurosci. 2006b;29:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand LA, Flagel SB, Garcia-Fuster MJ, Watson SJ, Akil H, Sarter M, Robinson TE. Persistent alterations in cognitive function and prefrontal dopamine D2 receptors following extended, but not limited, access to self-administered cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2969–2980. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capriles N, Rodaras D, Sorge RE, Stewart J. A role for the prefrontal cortex in stress-and cocaine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 2003;168:66–74. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1283-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, Fitzgerald J, Reivich M, O’Brien CP. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:11–18. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz FC, Babin KR, Leao RM, Goldart EM, Bossert JM, Shaham Y, Hope BT. Role of nucleus accumbens shell neuronal ensembles in context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. J Neurosci. 2014;34:7437–7446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0238-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore RS, Murray TH, Sanghera JS, Pelech SL, Braban JM. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by glutamate receptor stimulation in rat primary cortical cultures. J Neurochem. 1993;61:1626–1633. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb09796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JT, Olive MF. Glutamatergic substrates of drug addiction and alcoholism. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:218–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George O, Mandyam CD, Wise S, Koob GF. Extended access to cocaine self-administration produces long-lasting prefrontal cortex-dependent working memory impairments. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;33:2472–2482. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George O, Koob GF. Individual differences in prefrontal cortex function and the transition from drug use to drug dependence. Neurosci & Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:232–247. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel-Goody SM, Davies KD, Alvestad Linger RM, Freund RK, Browning MD. Phospho-regulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in adult hippocampal slices. Neurosci. 2009;158:1446–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis. Neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:642–1652. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Behavioral and functional evidence of metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 dysregulation in cocaine-escalated rats: Factor in the transition to dependence. Biol Psychiat. 2010;68:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing MC, Miller SW, See RE, McGinty JF. Relapse to cocaine seeking increases activity-regulated gene expression differentially in the prefrontal cortex of abstinent rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;198:77–91. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester R, Garavan H. Executive dysfunction in cocaine addiction: evidence from discordant frontal, cingulate, and cerebellar activity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11017–11022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3321-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Taylor JR. Impulsivity resulting from frontostriatal dysfunction in drug abuse: implications for the control of behavior by reward-related stimuli. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:373–390. doi: 10.1007/pl00005483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW. Glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:561–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, Melendez R, Kalivas PW. Ceftriaxone restores glutamate homeostasis and prevents relapse to cocaine seeking. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:81–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GK, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupchik Y, Moussawi K, Tang XC, Wang X, Kalivas BC, Kolokithas R, Ogburn KB, Kalivas PW. The effect of N-acetylcysteine in the nucleus acumbens on neurotransmission and relapse to cocaine. Biol Psychiat. 2011;71:978–986. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau LF, Huganir R. Differential tyrosine phosphorylation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20036–20041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Chen N, Luo T, Otsu Y, Murphy TH, Raymond LA. Differential regulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:833–8334. doi: 10.1038/nn912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgen V, Kong L, Kau KS, Madayag A, Mantsch JR, Baker DA. Time course of cocaine-induced behavioral and neurochemical plasticity. Addict Biol. 2012;19:529–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Yang L, Arora A, Choe ES, Zhang G, Liu Z, Fibuch EE, Wang JQ. Role of protein phosphatase 2A in mGluR5-regulated MEK/ERK phosphorylation in neurons. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12602–12610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Kalivas PW. The circuitry mediating cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8655–8663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08655.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty JF, Berglind WJ, Whitfield TW. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cocaine addiction. Brain Res. 2010;1314:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguens M, Del Olmo N, Higuera-Matas A, Torres I, Garcia-Lecumberri C, Ambrosio E. Glutamate and aspartate levels in the nucleus accumbens during cocaine self-administration and extinction: a time course microdialysis study. Psychopharmacol. 2008;196:303–313. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0958-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Marshall JF. Molecular substrates of retrieval and reconsolidation of cocaine-associated contextual memory. Neuron. 2005;47:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland PJ, Luong NT, Woodward JJ, Chandler LJ. BDNF activation of ERK is autonomous from the dominant extrasynaptic NMDA receptor EK shut-off pathway. Neurosci. 2008;151:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens DM, Keyes SM. Differential regulation of MAP kinase signaling by dual-specificity protein phosphatases. Oncogene. 2007;26:3203–3213. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Nairn AC, Wang P, Lombroso PJ. NMDA-mediated activation of the tyrosine phosphatase STEP regulates the duration of ERK signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:34–42. doi: 10.1038/nn989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Connor JA. NR2B-NMDA receptor-mediated increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration regulate the tyrosine phosphatase, STEP, and ERK MAP kinase signaling. J Neurochem. 2010;114:1107–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06835.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW. Infralimbic prefrontal cortex Is responsible for inhibiting cocaine seeking in extinguished rats. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6046–6053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1045-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrino LJ, Lyons D. Orbital and medial prefrontal cortex and psychostimulant abuse: studies in animal models. Cerebral Cortex. 2000;10:326–336. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SR, Peselow E. Pharmacotherapy of addictive disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32:277–289. doi: 10.1097/wnf.0b013e3181a91655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MW, Kalia LV. SRC kinases: a hub for NMDA receptor regulation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2004;5:317–328. doi: 10.1038/nrn1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolnick P, Volkow N. Addiction therapeutics: obstacles and opportunities. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:890–891. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondheimer I, Knackstedt LA. Ceftriaxone prevents the induction of cocaine sensitization and produces enduring attenuation of cue- and cocaine-primed reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Behavioural Brain Res. 2011;225:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Rebec GV. Repeated cocaine self-administration alters processing of cocaine-related information in rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8004–8008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1413-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun WL, Coleman NT, Zelek-Molik A, Barry SM, Whitfield TW, Jr, McGinty JF. Relapse to cocaine-seeking after abstinence Is regulated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase A in the prefrontal cortex. Addiction Biology. 2014;19:77–86. doi: 10.1111/adb.12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun WL, Zelek-Molik A, McGinty JF. Short and long access to cocaine self-administration attenuates the tyrosine phosphatase STEP and GluN2B phosphorylation but differentially regulates AMPA subunit expression in the prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacol. 2013;229:603–613. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3118-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun WL, Eisenstein EA, Zelek-Molik A, McGinty JF. A single BDNF infusion into the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex attenuates cocaine self-administration-induced phosphorylation of synapsin in the nucleus accumbens during early withdrawal. Intl J Neuropsychopharmacology. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu049. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from genes, to function, to disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:833–846. doi: 10.1038/nrm2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Corvol JC, Pages C, Besson MJ, Maldonado R, Caboche J. Involvement of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade for cocaine-rewarding properties. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8701–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08701.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Pascoli V, Svenningsson P, Paul S, Enslen H, Corvol JC, Stipanovich A, Caboche J, Lombroso PJ, Nairn AC, Greengard P, Herve D, Girault JA. Regulation of a protein phosphatase cascade allows convergent dopamine and glutamate signals to activate ERK in the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:491–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408305102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS. Addiction, a disease of compulsion and drive: Involvement of orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2000;10:318–325. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Skolnick P. New medications for substance use disorders: challenges and opportunities. Neuropsychopharm Rev. 2012;37:290–292. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward AJ, Rasmussen BA, Corley G, Henry C, Kim JK, Walker EA, Rawls SM. Beta-lactam antibiotic decreases acquisition of and motivation to respond for cocaine, but not sweet food, in C57Bl/6 mice. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:370–373. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283473c10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield TW, Gomez AM, McGinty JF. The suppressive effect of an intra-prefrontal cortical infusion of BDNF on cocaine relapse is trk receptor and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase mitogen activated protein kinase dependent. J Neurosci. 2011;31:834–842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4986-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala AR, Osredkar T, Joyce JN, Neisewander JL. Upregulation of Arc mRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex following cue-induced reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior. Synapse. 2008;62:421–431. doi: 10.1002/syn.20502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]