Abstract

Background:

Cumulative evidence in the dental literature strongly supports the fact that poor oral hygiene practices and inadequate attention toward oral health during pregnancy have an impact on developing the fetus and significant adverse postnatal effects. Available literature suggests that the research is deficit in assessing knowledge and practices related to exposure to radiation, use of medication and safe period for dental treatment during pregnancy. Assessing the knowledge and practices among pregnant women could be a valuable tool for policy makers to improve the oral health. To assess knowledge and practices of pregnant woman regarding oral health.

Materials and Methods:

This study was a cross sectional survey. A total of 332 samples were selected by convenience sampling technique. A questionnaire containing 14 close-ended questions related to knowledge and practices pertaining to oral health during pregnancy along with sociodemographic data were used for collecting baseline information.

Results:

The overall level of knowledge and practice was 27.17% and 55%, respectively. Majority of respondents (89.10%) were not aware that gum diseases are common during pregnancy. Most of them (73.07%) were not aware of safe period for undergoing dental treatment during pregnancy. Only 19.87% were aware that exposure to high dose of radiation was hazardous to their babies. Around 18.6% did not brush when they experienced bleeding, 35.25% cleaned their teeth using finger.

Conclusion:

The overall results suggest that knowledge and practices of pregnant women need to be greatly improved. All necessary measures should be taken for maintenance of oral hygiene and to avoid complications with the use of drugs and exposure to radiation.

Keywords: Awareness, dental attendance, oral health and pregnancy

Introduction

Many physiological conditions in women can bring some reversible changes in oral health. Conditions such as puberty, pregnancy and menopause have a significant effect on the oral health of women.1 Pregnancy is a period of both joy and anxiety in a woman’s life and is characterized by various physiological changes in her body brought about by the circulating female sex hormones.2 A number of oral changes are inevitable during pregnancy. Immunological, dietary and behavioral factors associated with pregnancy are believed to be contributing factors. Pregnant women are particularly susceptible to gingival and periodontal diseases.3-5 In addition, they may not experience symptoms until advanced disease stages and therefore unknowingly increase perinatal risk. Associated risks include premature birth, low birth weight babies, pre-eclampsia, ulcerations of the gingival tissue, pregnancy granuloma, and tooth erosion. These risks increase in women who smoke, experience nutritional deficiencies or have less frequent visits to the dentist.6-8 In recent years, research linking periodontitis to the risk for adverse birth outcomes has resulted in increased interest in the topic of oral health during pregnancy. Increased attention has been focused on maternal periodontitis and preterm and low birth weight.9-11 Several studies have confirmed the association after adjusting for confounding factors.

Practices such as exposure to radiation,12 intake of certain drugs like tetracycline chlorampenical, aspirin, etc.13,14 and practices like smoking and alcoholism have adverse pregnancy outcome or birth defects. Aspirin and diffusional have both been associated with prolonged gestation and labor, anemia, increased bleeding potential and premature closure of the ductus arteriosus of the heart and thus not recommended for pregnant women, even ibuprofen, ketoprofen, and naproxen are contraindicated in the third trimester of pregnancy. The period in which dental treatment should be taken is also of considerable interest to pregnant woman. Hence, pregnant population poses a unique situation to assess the oral health knowledge. The achievement of optimal oral health in pregnant women has its own benefits, however in the past it has been hampered by myths surrounding the safety of dental care during pregnancy. Many women fail to understand the importance of oral care in pregnancy while others experience barriers to care. Most of the mothers are very keen about proper growth and development of their children. Any educational program can have a lasting impact on pregnant women to improve their oral health. Collection of such data could also be a valuable tool for policy makers. The available data indicate, moderate to poor knowledge related to oral health and adverse pregnancy outcomes, poor dental attendance and oral health related practices.15-19 Hence, the present study aims at assessing the knowledge, attitude and practices of pregnant women of Bagalkot District.

Materials and Methods

The present study was a cross sectional survey conducted among the pregnant women of Bagalkot District. Ethical clearance was obtained from Institutional Ethical Committee of PMNM Dental College and Hospital Bagalkot. Informed consent was obtained from the study participants. Convenience sampling technique was used for selection of subjects. The subjects were selected from two tertiary care centers, four primary health centers and 12 private nursing homes of Bagalkot district over a period of 2 months. The demographic data including socioeconomic status (SES) and oral hygiene practices were recorded from each of the pregnant woman. Modified Kuppuswamy scale was used for recording SES. Based on the pilot study results, with 31% prevalence of knowledge, 5% permissible error and 95% confidence interval, sample size was estimated to be 332.

Cross sectional data were collected from direct interviewing of the subjects through a questionnaire. A close-ended questionnaire containing 14 questions was used. The questions were based on knowledge and practices related to pregnancy and oral health, gingival conditions, oral hygiene, utilization of dental health services, habits and use of medications. Few of the questions had multiple options based on the positive response for both knowledge and practices. The questionnaire was pilot tested among twenty individuals and assessed for validity. Cronbach’s alpha value for knowledge and practice was 0.732 and 0.718, respectively. The questionnaire was distributed to pregnant women and asked to complete in front of the investigator. For those who were illiterate the questionnaire was explained and answers elicited. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 16. Each positive response to knowledge and practices was scored as 1 and negative response as zero. The total scores including suboptions were summed up and divided by total number of subjects to obtain the mean value for both knowledge and practices respectively, and percentage is obtained accordingly.

Results

Demographics

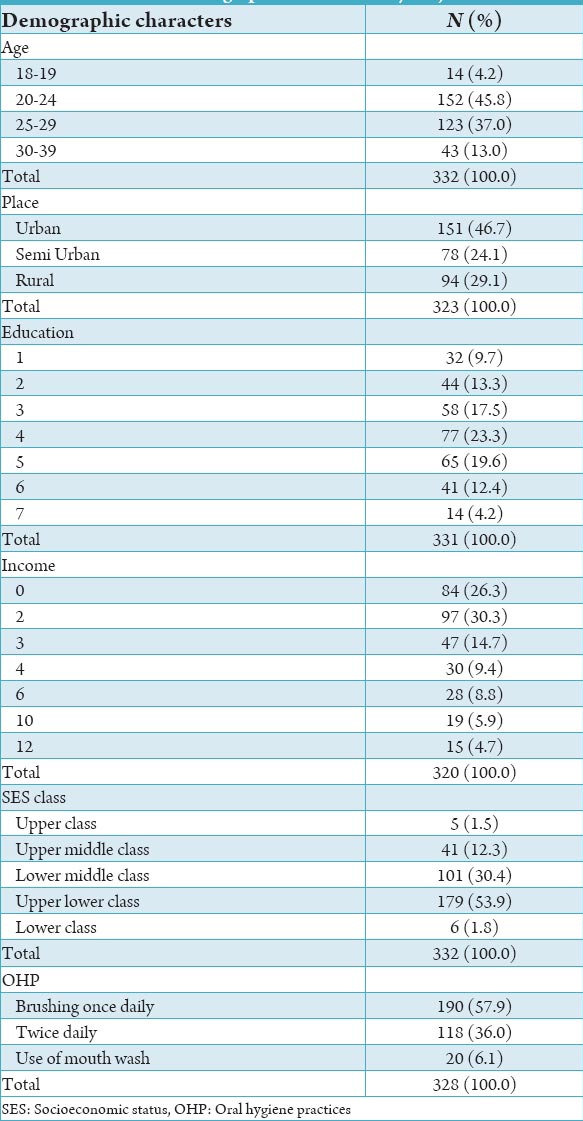

The majority (152 or 45.8%) of the participants were in the age group of 20-24 years and around 37% were between 25 and 30 years. The study population was heterogeneous. Nearly half of the participants (46.7%) belonged to the urban area, and 24.1% were from semi urban and 29.1% belonged to the rural area. SES showed that the majority of the respondents (53.9%) belonged to upper lower class and 30.4% to upper middle class (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic details of study subjects.

Response to knowledge questions

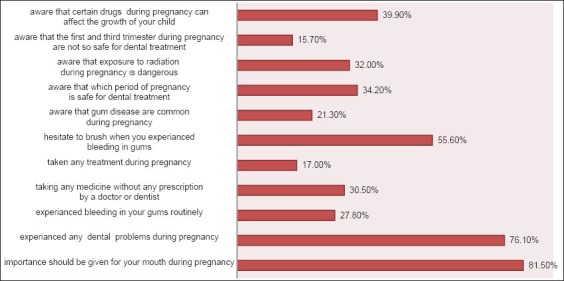

The mean knowledge level was around 1.36 (27.17 %) (Table 2) most of the respondents (78.7%) were not aware that gum diseases are common during pregnancy (Graph 1). About 65.8% were not aware of safe period for undergoing dental treatment during pregnancy. Only 32% were aware that exposure to radiation is hazardous to their babies. Most of the respondents (84.3%) were not aware that the first and third trimesters are not so suitable for dental treatment. More than half of the subjects (60.16%) were aware that the intake of certain drugs can affect child’s development.

Table 2.

Mean level of knowledge of respondents.

Graph 1.

Proportion of respondents to knowledge and practices.

Perceived dental experiences and practices

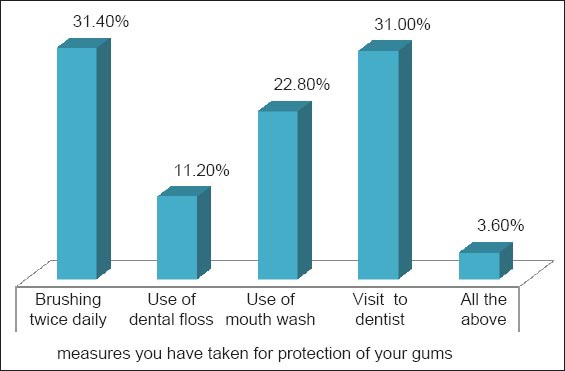

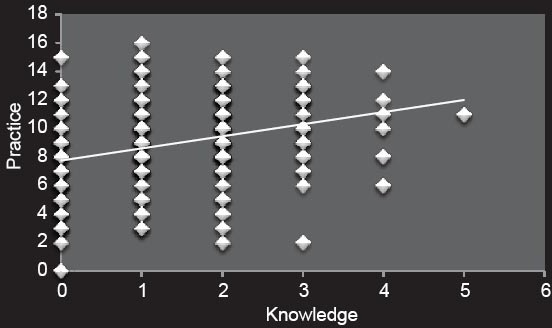

The mean level of practice was 8.9 (55%) (Table 3). Majority of the participants (76.1%) had dental problems during pregnancy. Nearly one third of study population (38.46%) had perceived signs of dental disease during pregnancy. Slightly more than one-third of the subjects (42.9%) had consulted their Obstetrician and Gynecologist for dental problems, about 40.1% to their dentist and 16.6% had ignored. Less than one third of the population (27.8%) had experienced bleeding gums during pregnancy. A small proportion (18.6%) did not brush when they experienced bleeding, 23.9% cleaned using finger, 16.4% used the soft brush and 41.1% consulted the dentist. Less than half of respondents (44.4%) were hesitant to brush when they experienced bleeding. More than half of them brush twice daily, 11.2% made use of dental floss, 22.8% used mouth wash and 31% consulted dentist at frequent intervals (Graph 2). Around 30.5%, had analgesics for dental pain without prescription of a dentist. Only 17% of study subjects had taken dental treatment during pregnancy. There is no significant difference in the knowledge and practices of pregnant women when adjusted for place of residence and socioeconomic class (Tables 4 and 5). There was a partial positive correlation (r = 0.307 P < 0.05) between knowledge and practices (Graph 3).

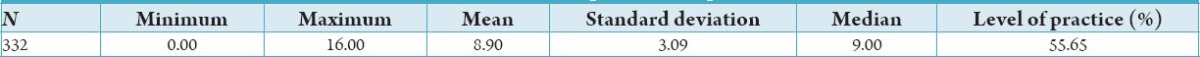

Table 3.

Mean level of practices of respondents.

Graph 2.

Measures taken by respondents for protection of their gums.

Graph 3.

Correlation between knowledge and practices.

Discussion

Establishing a healthy oral environment is the most important objective in planning dental care for the pregnant patient. Pregnancy is a potential risk condition where many pregnant women yield to dentist advice to safe guard the proper development of their babies.

In the present study, majority of the pregnant women were in the age group of 20-24 years. Education status revealed that 45% of them had high school education and 27% were illiterate. For the majority of them the source of antenatal care was private nursing homes, 25% received care in tertiary care centers. The present study findings have clearly shown that the knowledge of pregnant women about association of oral health and adverse pregnancy outcome was poor. The poor knowledge is independent of SES and place of residence. Similar results were reported in the study by Habashneh et al.20 where knowledge was poor among homogeneous population of relatively high socioeconomic standing. Few of the earlier studies have reported that the SES and ethnic background have an impact on the knowledge and practices22,23 and positively influencing the dental seeking behavior but not so in the present study. Although the differences were not significant, further studies to assess the precise role of SES and place of residence should be conducted.

In the present study, majority of respondents were unaware of gingivitis, safe period for dental treatment and hazards of exposure to high dose of radiation during pregnancy. Gingivitis though common and reversible during pregnancy needs significant attention. It is also advisable for pregnant woman to seek dental care during second trimester, as most of the tissues are in the formative period in the first trimester and because of risk of postural hypotension and positional discomfort, in the third trimester dental treatment should be avoided. Poor knowledge in the present study can also be attributed for patient being interviewed at varying length of pregnancy. Evaluation at the third trimester would have better estimated the knowledge and practices.

In the present study despite perceived dental problems, majority of them did not receive any dental treatment during pregnancy. Almost a quarter (23.5%) of the women believed that they had periodontal problem while 46.3% reported of having carious teeth. In the study of Hashim19 more than 44% reported to the dentist having dental pain, and about 40% women felt that their oral health was poor. About 94% of the women were brushing their teeth at least once a day. More than half of the women (58.3%) visited the dentist during their most recent pregnancy, mostly for dental pain. Around 38% had perceived signs of oral diseases. Around 53.5% of them have reported of brushing once daily. In the study by Christensen et al. 96% brushed their teeth at least twice a day and nine out of ten were regular users of the dental-care system.15 However, the data were collected by telephonic survey. The significant increase in dental attendance was attributed to provision of special care to pregnant women. In the study by Hullah et al., majority reported good oral hygiene habits such as brushing their teeth twice a day (73.7%) and using mouthwash (51%).17 In the present study, 57.9% said that they were brushing once daily and 36% twice daily.

In the present study, nearly 40% of subjects said that they reported to dentists when experience any dental problems and only 17% consulted dentist for treatment. The findings suggest that patients should be encouraged to schedule elective dental treatment during the second trimester but seek prompt care for acute dental problems. Less than half of respondents said that they consulted their gynecologist or obstetrician for oral health problems. The findings suggest the need of adequate training of gynecologist or obstetrician for oral diseases during pregnancy and patients should also be encouraged to visit dentist. The number of pregnant women who reported to dentists was relatively less as compared to the study of PRAMS that is 34.7%.24 In the study by Honkala,18 nearly half of the women had visited a dentist during pregnancy, mostly for dental pain. Most of the women had received no instructions concerning oral health care during their pregnancy. Reports of dental care use during pregnancy in other parts of the world also showed similar figures ranging from 27% to 61%.18-23 Relatively high dental attendance rate of 55% was reported in the study of Bamanikar et al. which can be attributed to high response rate when compared to other studies.22

There is serious concern about the dental care seeking behavior of pregnant women in the present study. Relatively poor attendance in the present study can be attributed to lack of availability of dental service, fear and misconception associated with dental treatment, perceptions of not having any oral health problems or long waiting time at the clinic etc. The data related to source of payment and dental insurance which significantly influence the dental attendance rate in most of the reported studies has not been assessed, because the mode of payment is predominantly fee for service in India. None of the study participants had the history of smoking and alcoholism. There are no data to compare the knowledge regarding the use of medication, exposure to radiation and the safe period for dental treatment among pregnant women, which were significantly low in the present study. As these practices have significant adverse post natal effect, further studies should give due attention. One of the limitations of the study was the convenience sampling technique, and hence generalizibity of the present study results should be done with caution.

Conclusion

The overall results suggest that knowledge and practices of pregnant women need to be greatly improved. All necessary measures should be taken for maintenance of oral hygiene and to avoid complications with the use of drugs and exposure to radiation. Oral health care should be a part of regular antenatal care.

Clinical Relevance

Pregnancy is a unique risk condition in terms of poor oral health related practices and its adverse effect on developing fetus. Illicit use of medicines and exposure to high dose of radiation, especially in the first trimester further increases the risk. Pregnant women should be educated to understand the consequences of the same. Enhanced screening and referral services should be provided at the preconception and antenatal period.

Recommendations

Providing oral health education in clinics and advocating affordable oral health services for all pregnant women should be considered. Education of oral health should be a part of regular antenatal care. The gynecologist and obstetrician should make the oral health care mandatory during pregnancy. Nurses, nurse practitioners, and nurse-midwives should include an assessment of maternal dentition and referral for dental problems as part of their prenatal practice. Public policies that support comprehensive dental services for vulnerable women of childbearing age should be expanded.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Source of Support: Nil

References

- 1.Ferris GM. Alteration in female sex hormones: Their effect on oral tissues and dental treatment. Compendium. 1993;14(12):1558–64. 1566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee A, McWilliams M, Janchar T. Care of the pregnant patient in the dental office. Dent Clin North Am. 1999;43(3):485–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zachariasen RD. The effect of elevated ovarian hormones on periodontal health: Oral contraceptives and pregnancy. Women Health. 1993;20(2):21–30. doi: 10.1300/J013v20n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loee H. Periodontal changes in pregnancy. J Periodontol. 1965;36:209–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breedlove G. Prioritizing oral health in pregnancy. Kans Nurse. 2004;79:4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuamah I, Annan BD. Periodontal status and oral hygiene practices of pregnant and non-pregnant women. East Afr Med J. 1998;75(12):712–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss KL, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. Clinical risk factors associated with incidence and progression of periodontal conditions in pregnant women. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(5):492–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davenport ES, Williams CE, Sterne JA, Murad S, Sivapathasundram V, Curtis MA. Maternal periodontal disease and preterm low birthweight: Case-control study. J Dent Res. 2002;81(5):313–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Offenbacher S, Boggess KA, Murtha AP, Jared HL, Lieff S, McKaig RG, et al. Progressive periodontal disease and risk of very preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):29–36. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000190212.87012.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffcoat MK, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC. Periodontal infection and preterm birth: Results of a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(7):875–80. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serman NJ, Singer S. Exposure of the pregnant patient to ionizing radiation. Ann Dent. 1994;53(2):13–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas DA, Pynn BR, Sands TD. Drug use for the pregnant or lactating patient. Gen Dent. 2000;48(1):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pregnancy categories for prescription drugs. FDA Drug Bull. 1982;12:24–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christensen LB, Jeppe-Jensen D, Petersen PE. Self-reported gingival conditions and self-care in the oral health of Danish women during pregnancy. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(11):949–53. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers SN. Dental attendance in a sample of pregnant women in Birmingham, UK. Community Dent Health. 1991;8(4):361–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hullah E, Turok Y, Nauta M, Yoong W. Self-reported oral hygiene habits, dental attendance and attitudes to dentistry during pregnancy in a sample of immigrant women in North London. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277(5):405–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honkala S, Al-Ansari J. Self-reported oral health, oral hygiene habits, and dental attendance of pregnant women in Kuwait. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(7):809–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashim R. Self-reported oral health, oral hygiene habits and dental service utilization among pregnant women in United Arab Emirates. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10(2):142–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2011.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Habashneh R, Guthmiller JM, Levy S, Johnson GK, Squier C, Dawson DV, et al. Factors related to utilization of dental services during pregnancy. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(7):815–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boggess KA, Urlaub DM, Moos MK, Polinkovsky M, El-Khorazaty J, Lorenz C. Knowledge and beliefs regarding oral health among pregnant women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(11):1275–82. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bamanikar S, Kee LK. Knowledge, attitude and practice of oral and dental healthcare in pregnant women. Oman Med J. 2013;28(4):288–91. doi: 10.5001/omj.2013.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas NJ, Middleton PF, Crowther CA. Oral and dental health care practices in pregnant women in Australia: A postnatal survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaffield ML, Gilbert BJ, Malvitz DM, Romaguera R. Oral health during pregnancy: An analysis of information collected by the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(7):1009–16. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]