Abstract

Background:

Herpes simplex virus infections are very common worldwide. The virus can cause infection in various body parts, especially eyes and the nervous system. Therefore, an early diagnosis and highly sensitive method is very helpful.

Objectives:

The present study sought to investigate the efficiency of Real-time TaqMan probe PCR in the diagnosis of HSV infection in suspected patients.

Patients and Methods:

In this study, 1566 patients with suspected HSV infections were enrolled. They aged 17 days to 96 years. The collected specimens were classified into four groups; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from HSE suspected individuals, samples from eye epithelial scraping, tear fluid or aqueous humor from herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) suspected patients, plasma of immune compromised patients and mucocutaneous collected samples from different body parts. The samples were analyzed by Real-time PCR assays.

Results:

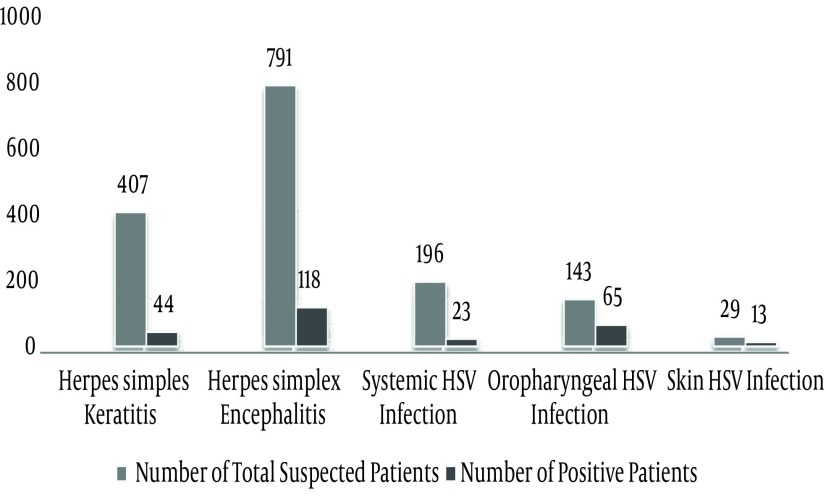

In total, 44 (5.6%), 118 (26.8%), 23 (11.7%), 13 (44.8%) and 65 (45.5%) of 791 HSE, 407 HSK, 29 skin HSV, 143 oropharyngeal suspected patients and 196 patients with systemic HSV infection HSV had positive results by Real-time PCR assays, respectively.

Conclusions:

Real-time PCR assay, due to its high sensitivity and specificity, can help in early diagnosis and more effective treatment for patients. Also, it requires shorter hospital stay and promotes patients' survival.

Keywords: Herpes Simplex Virus, Encephalitis, Keratitis, Real-Time PCR

1. Background

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections are very common worldwide. Clinically, herpes viruses display a range of diseases. Common HSV infections involve skin and/or mucus affecting face and mouth, genitalia and other body parts (1). Also, this virus can damages eyes and the central nervous system (CNS) (2). Herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) infection is one of the known viral keratitis and the main cause of blindness and visual morbidity in developing countries. Eye infection is a latent infection in the body, mainly in the trigeminal ganglia and can be revived by fever, trauma, stress, immunosuppressive agent or exposure to ultraviolet radiation (3-5). The prevalence of ocular HSV disease has been estimated in 5.9 to 7.20 cases per 100000 annually, as reported in some countries (6).

A few studies were performed regarding the diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis HSE in Iran until now. A study conducted in Mashhad revealed HSE prevalence in infants with septicemia as 3.3% (7). Another study conducted in Hamedan showed the HSE incidence as 15% (8). Accordingly, curing HSK is hard for ophthalmologists despite the existence of advanced diagnostic methods and impressive effect of antiviral drugs such as acyclovir (3). Other serious HSV infections include herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE), which is a common cause of severe sporadic viral infection in humans CNS (4, 9). About 30% of HSE cases resulted from primary HSV infection, predominantly occurring in individuals younger than 18 years (10). Nearly, 50% of patients with HSE are older than 50 years. HSE occurs relatively uncommonly with prevalence of only one case per 500000 populations annually (11). According to the studies on HSK in Iran, the prevalence of this infection among HSK sufferers was relatively variable between 30% - 88% (12, 13). HSE causes significant morbidity and mortality in patients without or with ineffective antiviral treatment. In the absence of treatment, mortality rate exceeds 70% and only 20% of survivors completely regain their normal brain function (10, 11, 14).

Primary diagnosis and treatment with acyclovir are essential in decreasing both mortality and occurrence of neurological sequelae in surviving patients (15). HSV infection may be primary or recurrent (16). HSV is the main cause of herpes infections in mouth and lips, including cold sores and fever blisters, which commonly passes through normal human contact (17). A kind of mucosal HSV infection, genital HSV, is a sexually transmitted infection. The biggest concern about genital herpes during pregnancy is that the mother might transmit it to her fetus during labor and delivery. Newborn herpes is relatively rare; nearly 1500 newborns are affected annually (18). However, the disease can be disrupting. Therefore, it is important to make early diagnosis and reduce the chance of infection in babies (19). Early, rapid and reliable diagnosis of such infections, especially HSE and HSK, is very critical for patients’ safety. Today, Real-time TaqMan probe PCR analysis is a valuable, reliable, highly sensitive and specific diagnostic method in HSV DNA detection (20, 21). Herpes simplex viral load in patients can serve as the best prospective marker for therapeutic effect.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to diagnose HSV infection in suspected patients by Real-time TaqMan probe PCR.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Patients

In this study, 1566 patients with suspected HSV infections were enrolled. Overall, 622 (39.8%) females and 944 (60.2%) males aged 17 days to 96 years with a mean ± SD of 32.48 ± 27.04 years old were included. They had been referred to Prof. Alborzi Clinical Microbiology Research Center (PACMRC), Namazi Hospital, Shiraz, Iran. In total, 36.9% (521 ones) of patients were younger than 15 years and 63.1% (891 adults) were older than 15 years. The samples were classified to four groups; first cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from HSE suspected individuals with symptoms such as alteration of consciousness, fever, dysphasia, ataxia and seizures received in sterile containers. Second, samples from epithelial scraping, tear fluid and aqueous humor in HSK suspected patients with symptoms including eye redness, mainly around the cornea, ache or pain in eyes, photophobia, watering eye and blurred vision. Third, plasma samples of immune compromised patients and the last one, samples were collected with swab from the vesicle of different parts; for example, blister on lips or eruption on tongue. All samples were collected within maximum six hours to arrive at PACMRC and kept frozen at -70°C until the examination. Research Ethics Committee at PACMRC, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran, reviewed and approved the design of study. Informed consents were obtained from participants or their legal guardians.

3.2. Nucleic Acid Extraction

DNA was extracted from 200 µL of CSF, serum and transport medium using spin-column based Stratec molecular, according to the manufacturer's instruction (Invisorb Spin Virus DNA Mini Kit, Germany).

3.3. Real-time Taq Man PCR

HSV Real-time PCR assay was performed with the Primer Design TM Genesig kit (Primer Design, UK). In brief, each PCR reaction contained 5 µL of extracted DNA, 10 µL of 1x TaqMan universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, New Jersey, USA), 15 Pmol of each primer and 5 Pmol probe. The final volume of Real-time PCR mixture was 20 µL. Amplification conditions using Primer Design kit were as follows; one cycle of 15 minutes at 95°C, 45 two-step cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C (denaturation step) and 1 minute at 60°C (annealing), performed in a 7500 Applied Biosystem Real-time instrument. The positive and negative controls were used in each run of PCR. The results were interpreted by PCR Amplification plots.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

HSV infection rate was statistically analyzed between different age groups and genders using SPSS software (version 16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

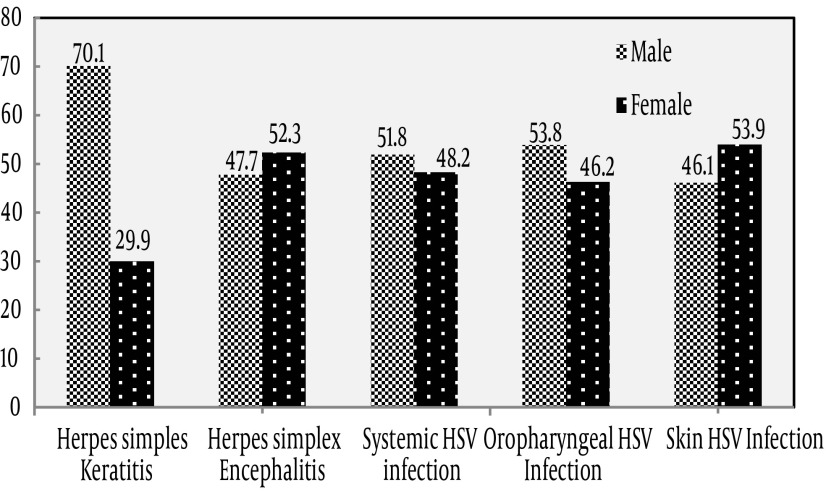

In this study, there were 1566 samples collected from June 2008 to August 2012. Figure 1 shows the distribution of collected samples as follows; 407 (25.6%) HSK, 791 (50.24%) HSE, 196 (12.42%) systemic HSV infection (plasma samples), 143 (9.84%) oropharyngeal (oral swabs) and 29 (1.9%) of total patients had HSV skin lesion (body swabs) (Table 1). HSE suspected patients comprised the highest frequency with 791 patients with 301 (38.4%) females and 490 (61.6%) males. Of 44 samples with positive results, 21 (47.7%) were male and 23 (52.3%) females (Figure 2). The patients were grouped for age range. Our data showed that 12 (29.3%) HSV genome positive patients with HSE were younger than 15 and the rest aged 15 years or older.

Figure 1. Distributions of Collected Specimens in Different Groups of Study and Number of Patients With Positive Results.

Table 1. Demographic Data of HSV Suspected Patients a.

| HSV Complications | Male | Female | Mean Age | Number of Positive, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSE | 490 | 301 | 31.15 | 44 (5.6) |

| HSK | 254 | 153 | 51.95 | 118 (26.8) |

| Skin | 18 | 11 | 9.20 | 13 (44.8) |

| Oropharyngeal | 65 | 76 | 13.07 | 65 (45.5) |

| Systemic infection | 103 | 93 | 15.15 | 23 (11.7) |

aAbbreviations: HSE, herpes simplex encephalitis; HSK, herpes simplex keratitis.

Figure 2. The Prevalence of HSV Infections in Different Groups of Study in Both Genders.

The difference in positive and negative samples between age and gender groups was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The second most frequent HSV infected patients included 153 (37.6%) female and 254 (62.4%) male patients with suspected HSK. The results showed that of 118 (26.8%) positive cases, 83 (70.1%) were males and 35 (29.9%) females (Figure 2); 6 (6.1%) were younger than 15 and 112 (93.9%) older than 15 years. A significant difference was found in positive and negative samples between age and gender groups (P < 0.001). There were 196 systemic HSV suspected patients (plasma samples) including 93 (48.2%) females and 103 males (51.8%). Of 23 positive samples, 14 (63.6%) were male and 9 (36.4%) female (Figure 2). Eighteen patients were younger than 15 years and five were older than 15 years. The difference in positive and negative samples was not statistically significant between age and gender groups (P > 0.05).

The patients with HSV skin lesion (body swabs) included 11 (37.9%) female and 18 male (62.1%). As shown, 13 (44.8%) had positive results; of 13 positive samples, 7 were male (53.8%) and 6 (46.2%) female (Figure 2). As far as age range was concerned, eight patients with positive results were younger than 15 and others were older than 15 years. Furthermore, 143 oropharyngeal HSV suspected cases (oral swabs) included 65 (46.1%) females and 76 (53.9%) males. Of patients with positive results, 30 (47.6%) and 33 patients (52.4%) were male and female (Figure 2), respectively. Among the respective 65 positive patients, 18 were younger than 15 and 47 older than 15 years. The difference in positive and negative samples of HSV skin and oropharyngeal suspected patients was not statistically significant between age and gender groups (P > 0.05).

5. Discussion

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which is widely used in clinics and laboratories, can be used for diagnosis of HSV infection. Among the PCR methods, Real-time PCR has the advantages of both speed and quantification (21). Recently, Real-time PCR has begun to demonstrate its potential usage in the field of clinical virology, specifically in detection of herpes virus DNA (15, 22). In the present study, Real-time PCR assay was used to detect HSV in suspected patients (23). From all HSV suspected patients referring to PACMRC, Namazi Hospital, Shiraz, Iran, more than 50% were suspected to HSE disorder, 407 (25.6%) HSK, 196 (12.42%) systemic HSV infection, 141 (9.84%) gingivostomatitis and 29 (1.9%) HSV skin lesions. Various studies showed the importance of early detection of these infections as soon as possible. HSE is one of the most considerable HSV associated disorders investigated in this study.

According to the results, 44 (5.6%) CSFs from 791 HSE suspected specimens had positive results for HSV genome including 21 (47.7%) males and 23 (52.3%) females. There was no significant difference between the genders for HSE. The previous study of present authors showed that (from November 2004 to May 2008) of the 236 samples, HSV DNA was detected in 22 (9.3%) cases by quantification PCR assay including 13 males and 9 females. Real-time PCR assay had no false negative results in this study and was a valuable tool in the diagnosis of HSE (24). In addition, increasing the number of patients with suspected HSE infection in the two periods of our study (November 2004 to May 2008 and June 2008 to August 2012) showed that a rapid, timely and sensitive diagnostic method is required.

Rapid diagnosis of HSK infection, the leading infectious cause of blindness, can be extremely useful in clinical terms. It seems that quantitative detection of HSV DNA in herpetic ulcers could be helpful in evaluation efficacy of antiviral treatment. Of 407 HSK suspected patients, 118 (26.8%) had positive results for HSV DNA. Six (6.1%) of patients with positive results were younger than 15 and the others (93.9%) older than 15 years. The results showed that HSV DNA in ocular HSV infection correlated with patients' age and there was a signification correlation between these two groups (i.e. under 15 and above 15 year old groups). Although the number of children with HSV keratitis is low, they are at risk of recurrent HSK and amblyopic prolonged systematic antiviral prophylaxis may help prevent such consequences (25). Similar obtained results indicated that the older patients with herpetic corneal ulcers, the greater their chance of HSV genome diagnosis (26).

These results suggested that HSK is one of the epidemiologically important eye diseases. It is better to monitor ocular herpetic disease by Real-time PCR method because of its high sensitivity for diagnosis of herpes keratitis, which could be helpful in clinical diagnosis and treatment decisions (27). HSV infections are the most common cause of skin, lips, buccal cavity and other gingivostomatitis disease. Among 29 cases of suspected HSV skin infections, 13 (44.8%) had positive results for HSV genome. According to age range, eight patients with positive results for HSV were younger than 15 and others were older than 15 years. Furthermore, of total positive patients with herpetic stomatitis infection, 30 (47.6%) were male and 35 (52.4%) were female, respectively. In the same group, of 65 patients with positive results, 18 and 47 patients were younger and older than 15 years, respectively. These results suggested that early diagnosis of infections is critical, especially in patients undergoing organ transplants.

Hygiene in schools and raising awareness of people in this regard can be effective in reducing HSV infections. Patients with systemic HSV infection are at a high risk of developing severe HSV disorder. Of 196 samples, 23 (11.7%) had positive results including 18 patients younger than 15 and 5 patients older than 15 years. The results showed no statistically significant difference in positive and negative samples between age and gender groups (P > 0.05). As revealed, the number of patients with suspected chronic vaginal infection was low in this study; however, early diagnosis of such devastating illness using Real-time PCR can be critical in pregnant women for the health of their fetuses. This study suggested that Real-time, quantitative PCR is becoming commonplace in clinical laboratory settings as a reliable, highly sensitive and specific method. Furthermore, determining herpes simplex viral load in suspected individuals can serve as the best prospective marker of therapeutic effect.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Alborzi Clinical Microbiology Research Center (PACMRC). This work was financially supported by a grant from PACMRC. Finally, our deep thanks go to Hassan Khajehei, PhD, for copyediting of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:Mazyar Ziyaeyan developed the original idea and the protocol. Nasrin Aliabadi wrote the manuscript and is guarantor. Marzieh Jamalidoust, Sadaf Asaei and Mandana Namayandeh analyzed data, contributed to the development of the protocol, abstracted data and prepared the manuscript.

Funding/Support:This study was financially supported by Clinical Microbiology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Fars, Iran.

References

- 1.Whitley RJ, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus infections. Lancet. 2001;357(9267):1513–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitley RJ. Herpes simplex encephalitis: adolescents and adults. Antiviral Res. 2006;71(2-3):141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamrah P, Pavan-Langston D, Dana R. Herpes simplex keratitis and dendritic cells at the crossroads: lessons from the past and a view into the future. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2009;49(1):53–62. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3181924dd8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domingues RB, Fink MCD, Tsanaclis AMC, De Castro CC, Cerri GG, Mayo MS, et al. Diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis by magnetic resonance imaging and polymerase chain reaction assay of cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol Sci. 1998;157(2):148–53. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimberlin D. Herpes simplex virus, meningitis and encephalitis in neonates. Herpes. 2004;11 Suppl 2:65A–76A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsiao CH, Yeung L, Yeh LK, Kao LY, Tan HY, Wang NK, et al. Pediatric herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea. 2009;28(3):249–53. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181839aee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amel Jamehdar S, Mammouri G, Sharifi Hoseini MR, Nomani H, Afzalaghaee M, Boskabadi H, et al. Herpes simplex virus infection in neonates and young infants with sepsis. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(2) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.14310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghannad MS, Solgi G, Hashemi SH, Zebarjady-Bagherpour J, Hemmatzadeh A, Hajilooi M. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis in hamadan, iran. Iran J Microbiol. 2013;5(3):272–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyler KL. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: encephalitis and meningitis, including Mollaret's. Herpes. 2004;11 Suppl 2:57A–64A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowley AH, Whitley RJ, Lakeman FD, Wolinsky SM. Rapid detection of herpes-simplex-virus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with herpes simplex encephalitis. Lancet. 1990;335(8687):440–1. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90667-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakeman FD, Whitley RJ. Diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis: application of polymerase chain reaction to cerebrospinal fluid from brain-biopsied patients and correlation with disease. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1995;171(4):857–63. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khodadoost MA, Sabahi F, Behroz MJ, Roustai MH, Saderi H, Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S, et al. Study of a polymerase chain reaction-based method for detection of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA among Iranian patients with ocular herpetic keratitis infection. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2004;48(4):328–32. doi: 10.1007/s10384-004-0081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firoozi B, Shahhosseiny MH, Yaghobi R. Diagnosis of herpes keratitis by PCR technique. Ann Biol Res. 2013;4(6):209–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revello MG, Baldanti F, Sarasini A, Zella D, Zavattoni M, Gerna G. Quantitation of herpes simplex virus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with herpes simplex encephalitis by the polymerase chain reaction. Clin Diagn Virol. 1997;7(3):183–91. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0197(97)00269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakimaru-Hasegawa A, Kuo CH, Komatsu N, Komatsu K, Miyazaki D, Inoue Y. Clinical application of real-time polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of herpetic diseases of the anterior segment of the eye. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2008;52(1):24–31. doi: 10.1007/s10384-007-0485-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr DJ, Tomanek L. Herpes simplex virus and the chemokines that mediate the inflammation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;303:47–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-33397-5_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MasCasullo V, Fam E, Keller MJ, Herold BC. Role of mucosal immunity in preventing genital herpes infection. Viral Immunol. 2005;18(4):595–606. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberts CJ, Schim van der Loeff MF, Papenfuss MR, da Silva RJ, Villa LL, Lazcano-Ponce E, et al. Association of Chlamydia trachomatis infection and herpes simplex virus type 2 serostatus with genital human papillomavirus infection in men: the HPV in men study. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(6):508–15. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318289c186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruisten SM. Genital ulcers in women. Curr Womens Health Rep. 2003;3(4):288–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schloss L, Falk KI, Skoog E, Brytting M, Linde A, Aurelius E. Monitoring of herpes simplex virus DNA types 1 and 2 viral load in cerebrospinal fluid by real-time PCR in patients with herpes simplex encephalitis. J Med Virol. 2009;81(8):1432–7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domingues RB, Lakeman FD, Mayo MS, Whitley RJ. Application of competitive PCR to cerebrospinal fluid samples from patients with herpes simplex encephalitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(8):2229–34. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2229-2234.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hjalmarsson A, Granath F, Forsgren M, Brytting M, Blomqvist P, Skoldenberg B. Prognostic value of intrathecal antibody production and DNA viral load in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with herpes simplex encephalitis. J Neurol. 2009;256(8):1243–51. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boivin G. Diagnosis of herpesvirus infections of the central nervous system. Herpes. 2004;11 Suppl 2:48A–56A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziyaeyan M, Alborzi A, Borhani Haghighi A, Jamalidoust M, Moeini M, Pourabbas B. Diagnosis and quantitative detection of HSV DNA in samples from patients with suspected herpes simplex encephalitis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15(3):211–4. doi: 10.1016/s1413-8670(11)70177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziyaeyan M, Japoni A, Roostaee MH, Salehi S, Soleimanjahi H. A serological survey of Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 and 2 immunity in pregnant women at labor stage in Tehran, Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2007;10(1):148–51. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.148.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill JM, Clement C. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA in human corneas: what are the virological and clinical implications? J Infect Dis. 2009;200(1):1–4. doi: 10.1086/599330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaye S, Choudhary A. Herpes simplex keratitis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006;25(4):355–80. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]