Abstract

Context

A large racial disparity exists in organ donation.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to identify factors associated with becoming a registered organ donor in among African Americans in Alabama.

Methods

The study utilized a concurrent mixed methods design guided by the Theory of Planned Behavior to analyze African American’s decisions to become a registered organ donor using both qualitative (focus groups) and quantitative (survey) methods.

Results

The sample consisted of 22 registered organ donors (ROD) and 65 non-registered participants (NRP) from six focus groups completed in urban (n=3) and rural (n=3) areas. Participants emphasized the importance of the autonomy to make one’s own organ donation decision and have this decision honored posthumously. One novel barrier to becoming a ROD was the perception that organs from African Americans were often unusable due to high prevalence of chronic medical conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. Another novel theme discussed as an advantage to becoming a ROD was the subsequent motivation to take responsibility for one’s health. Family and friends were the most common groups of persons identified as approving and disapproving of the decision to become a ROD. The most common facilitator to becoming a ROD was information, while fear and the lack of information were the most common barriers. In contrast, religious beliefs, mistrust and social justice themes were infrequently referenced as barriers to becoming a ROD.

Discussion

Findings from this study may be useful for prioritizing organ donation community-based educational interventions in campaigns to increase donor registration.

Keywords: Organ Donor Registration, Organ Donation, African American, Theory of Planned Behavior, Mixed Methods Design

Introduction

The need for more organ donors in the United States (U.S.) is well recognized. Currently, more than 105,000 patients are waiting for a solid organ transplant in the U.S., of which, over 6,500 patients will die each year before an organ becomes available.(1) Efforts to increase organ donation via the dissemination of “best practices” in the early 2000s have manifested in a significant increase in deceased organ donation.(2) While significant increases in organ donation have been realized across races, there remains a large disparity in organ donation between Caucasians and African Americans.

African American race is a significant predictor of organ non-donation.(3) At the same time, African Americans are significantly over represented on the transplant waitlist. For example, African Americans make up 26.5% of the Alabama population,(4) yet comprise 67.6% (2244/3320) of the renal transplant waiting list at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB).(5) During 2011, 143 deceased donor kidney transplants were performed at UAB of which African Americans accounted for 59.4% of transplant recipients yet only 16.8% of donor organs originated in African Americans.(5) A recent review of all requests for organ donation in the Alabama donor service area demonstrated a four-fold increase in donor authorization in Caucasians compared to African Americans.(6)

The purpose of this study was to identify factors (beyond those already identified) associated with African Americans choosing to become a registered organ donor. This study adds to existing research by using a theory-based, mixed methods research design intended to reveal factors not tapped by previous research in a sample of African Americans from the Deep South. The dependent variable explored is “being a registered organ donor,” consistent with recommendations from comprehensive reviews of African American organ donation literature which advocate measuring organ donor registration and not attitudes concerning organ donation such as “I would consider becoming an organ donor.”(3)

Methods

Design

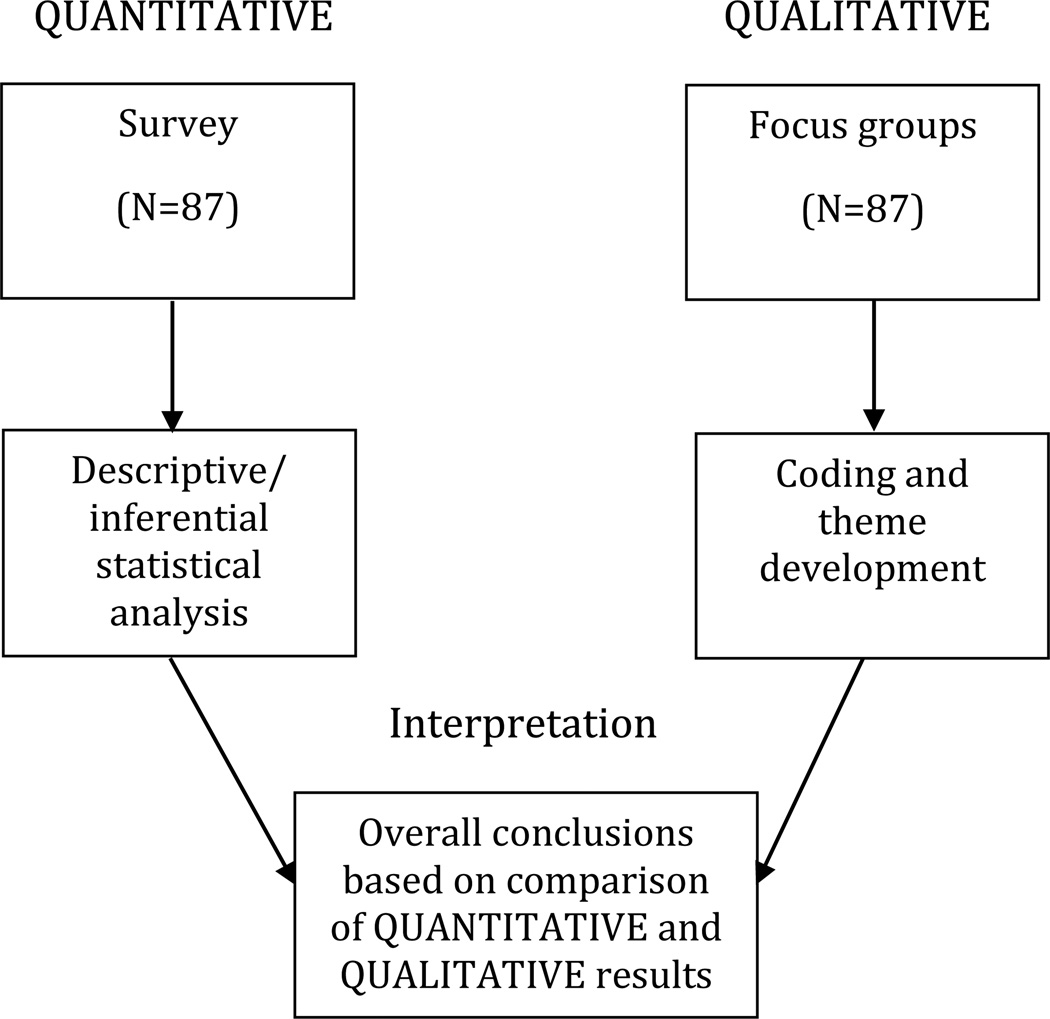

The study utilized a concurrent mixed methods design (7–9), which has been previously used in community health research to address health disparities.(10, 11) African Americans’ decisions to become a registered organ donor were explored using both qualitative (focus groups) and quantitative (survey) methods. (Figure 1) The results from survey and focus group analysis were compared to produce more consistent and valid conclusions.(12)

Figure 1.

Mixed Methods Concurrent Design Procedures in the Study

Theoretical Framework

This study used the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to explore factors influencing the choice to become a registered organ donor. The TPB, a model used by researchers to predict behavioral intentions(13), has strong empirical support.(14, 15) The theory specifies that people’s intentions are the most proximal determinant of their behavior. The model incorporates data from three domains: behavioral beliefs, subjective norm, and behavioral control.

Participant Recruitment

Study participants were recruited via existing UAB partnerships, coalitions, and community networks.(16, 17) Focus group advertisements were distributed through these established channels along with study eligibility requirements (African American race and age ≥ 19) and a phone number to call if they were interested in participating. The participants were recruited from areas defined as either urban or rural by the Alabama rural association. (18) The study was approved by the UAB Institutional Review Board (X090325003).

Data Collection

Six focus groups were completed. The number of participants per focus group ranged from 8 to 19. Both registered and not registered organ donors participated in the focus groups jointly. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected concurrently from the 87 focus group participants. Participants were provided with a $50 Visa gift card as compensation for their time and travel.

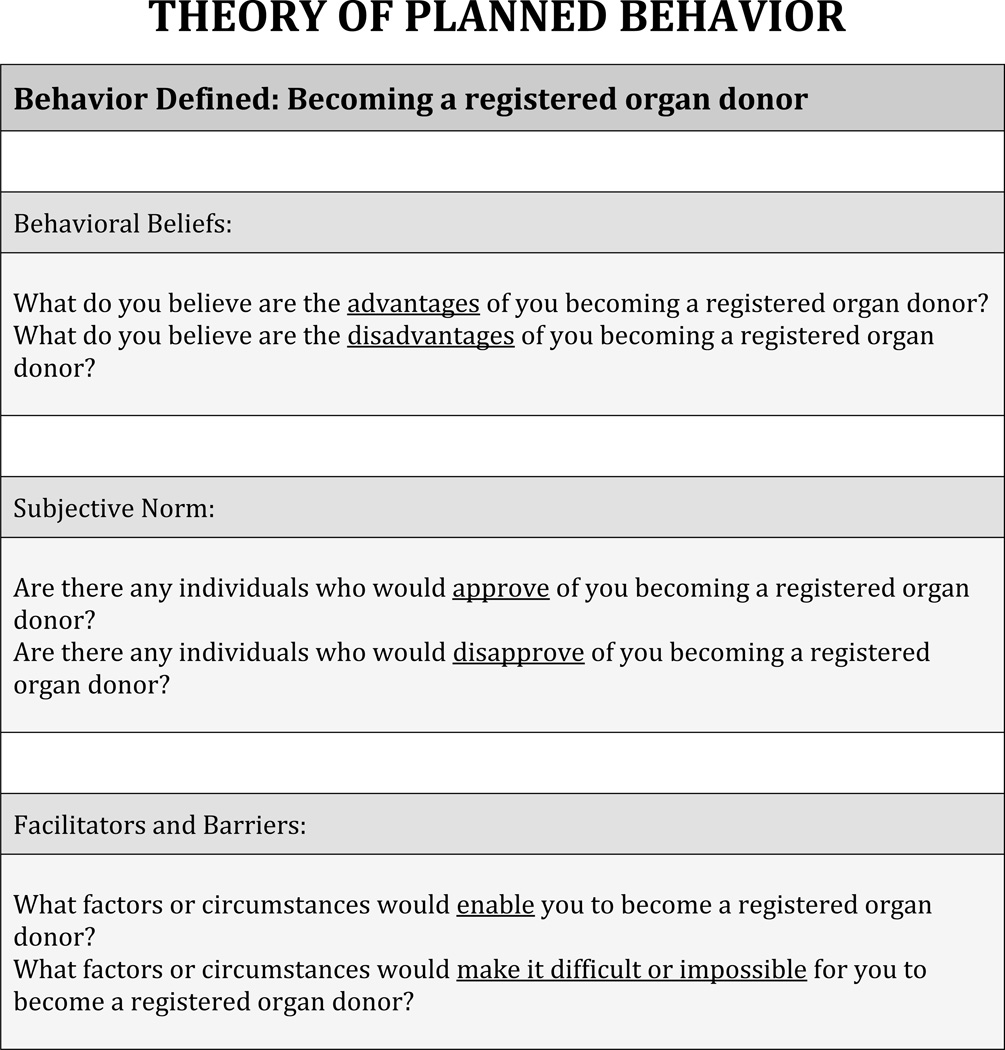

Qualitative data

Using the constructs of TPB and the procedures outlined by Morgan (19) and Krueger (20), members of the investigative team developed the qualitative research protocol to guide focus group discussions. The facilitator began each discussion by describing the purpose of the study and discussing the basic ground rules. Each session began by defining the behavior of interest, namely, becoming a registered organ donor, and illustrating the three avenues of becoming an organ donor (registration at the Department of Motorized Vehicles, mail-in brochure and online registration). The focus group moderator then asked specific questions regarding behavioral beliefs (advantages and disadvantages of becoming a registered organ donor), subjective norm (those who would approve or disapprove of becoming a registered organ donor) and behavioral control (facilitators and barriers to becoming a registered organ donor). (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Focus Group Protocol Guided by Theory of Planned Behavior

Quantitative data

Following the focus group, participants completed a quantitative questionnaire to assess their awareness and knowledge of organ donation, and attitudes regarding becoming a registered organ donor. The research team developed this preliminary questionnaire using the information from the organ donor literature and a “mock” focus group. An elicitation research “mock” focus group was completed on campus at UAB with 20 African American participants recruited from employees of the Survey Research Unit in Public Health prior to the main study. The mock focus group participants completed the questionnaire and provided feedback including identifying questions that were confusing and words that needed clarification.

The goal was to create a final survey instrument that would have quantitative questions for most qualitative themes that may arise from the focus group discussions. A panel of experts then reviewed the themes that emerged during the mock focus group as well as the answers to the preliminary questionnaire. Thirty-three questions were selected to be in the final instrument and were organized into the following categories: 13 organ donor attitude questions, 14 questions on organ donor awareness and 6 questions designed to measure organ donor knowledge. The validated nine-item Organ Donor Readiness Index (21) and the five-question “Beliefs” section of the National Minority Organ and Tissue Transplant Education Program (MOTTEP) (22) was embedded in the questionnaire. The final tool was rated by Microsoft Word (Redmond, WA) to be composed at a 7th grade level. Data obtained via the mock focus group was only used to inform the development of our final research instrument, and is not included in the statistical analysis in this study.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data

The digitally recorded focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim and analyzed inductively in two stages using a multi-functional software system for qualitative data analysis, NVivo10 (QSR International). First, a standard thematic analysis was conducted to search for common categories and themes in the data. Two qualitative investigators (NI and IH) independently coded the original transcripts by identifying key points and recurring categories and themes that were central to areas of discussion both within and across focus groups. A constant comparative method (23) was used to guide the analytical process. Inter-coder agreement between the two coders reached an acceptable 90% as recommended by Miles and Huberman. (24) Content analysis (25) was also performed on the generated categories and themes using the counts of text references in NVivo 10 to systematically represent consistencies in viewpoints across focus groups. Particular emphasis in the analysis was placed on how the themes interacted with others to explain intentions to become a registered organ donor within the study theoretical framework - TPB. [Table 2]

Table 2.

Qualitative Themes, Sub-Themes, Categories and Illustrative Quotes

| Themes/ Sub-Themes |

Categories | (%) | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Beliefs | |||

| Advantages | Saving Someone's Life | 51.6% | “It comes up in ways saying like, saving a life, it’s a good thing to do.” |

| Making It Your Own Decision | 20.0% | “My mama …she feel like it’s my life so I can do whatever I want to do.” | |

| Not Needing Organs When Dead | 18.3% | “When you are an organ donor, I’m dead anyway. I don’t need it.“ | |

| Personal Factors | 6.6% | “…cause it’s dealing with your life…it’s personal.” | |

| Taking Responsibility for Your Own Health | 3.3% | “So if we walk out of this room today and say yes I want to be an organ donor would it not behoove us to say to ourselves we need to make sure that our nutrition is appropriate and we take care of our bodies and since I’ve made that commitment that I want to be a donor that it would be a healthy donation?” | |

| Disadvantages | Fear | 30.3% | “The only disadvantage I think about is that if you become a donor when you’re alive, you know you’ll have to have surgery …you are going to have to go under the knife and have that organ removed.” |

| Legal Issues | 21.2% | “… you know you can make one decision and later on down the road, …there should be a waiver in there if I decide to change my mind I may do so.” | |

| Organ Usability | 16.6% | “As a whole, African Americans have more health issues … That’s a disadvantage….high cholesterol, heart disease, and all that, so, we probably have very little organs to donate with our lifestyle and eating habits.” | |

| Religious and Moral Beliefs | 10.6% | “Some people have their religious beliefs and some people have moral issues about it. I think that plays a role in it.” | |

| Social Justice | 7.6% | “…Sometimes when some people got more money than another person, that kind of up that person to get that organ before the one that really need it…the next in line.” | |

| Normative Beliefs | |||

| Approving | Family and Friends | 69.3% | “If you had a discussion with family members and significant others …then they would go along with.” |

| Health Care Providers | 16.3% | “…yes, with a doctor, like if the doctor was to bring it up and explain everything to me, I would probably feel fine about it.” | |

| Community | 8.2% | “… like I said, friends, your social surroundings …you can get positive feedback. I just know the people feel the same thing.” | |

| Those in Need of Organs | 6.1 | “A person may approve if you were at the point of death.” | |

| Disapproving | Family and Friends | 51% | “Tell your family that’s what your intentions… Sometimes people not on the same page and they still overlook and go against it…it still not fool proof.” |

| Church and Religious Groups | 20.4% | “The leadership of this church….they may be members among the body that might not believe in organ donation….” | |

| Community | 20.4% | “Outside of family, like I said, friends, your social surroundings if it brought up. for the most part I just would say more negative…” | |

| Behavioral Control | |||

| Facilitators | Information | 40% | “…if people knew more information then maybe it wouldn’t be a thing that’s so negative.” |

| Family Member Needs | 16.4% | “.if a family member was needing one.” | |

| Formal Process in Place | 16.4% | “…maybe when they register to vote? Maybe they need to put it on that.” | |

| Knowing Organ Recipients | 8.9% | “I think that’s something that’s important that you could see that person and know their story that they are ordinary people…” | |

| Altruism | 6.3% | “If it will help somebody else after I’m gone, then that’s fine…I can’t do anything with it. So, I am an organ donor.” | |

| Religious Beliefs | 6.3% | “I guess it depends on the church. A more modern church, one that’s non-denominational a little bit more …what’s going on in the world would be a lot more accepting.” | |

| Trust | 3.8% | “I feel that the majority of the doctors take an oath to do their best and to work on you …I feel like they would try to save me you know if they feel like I could be saved.” | |

| Barriers | Lack of Information | 41.2% | “…it’s the lack of information or whatever.” |

| Mistrust | 16.5% | “I think that goes to the Black community, they think that if it was an accident or whatever happened I think they not gonna work hard on me; I think that’s why a lot of them not an organ donor.” | |

| Fear | 12.4% | “I just think that the whole organ donor is a scary thing.” | |

| Religious Beliefs | 8.2% | “…The Bible always tell you, ashes to ashes, dust to dust…you going back to the ground…This is gone…” | |

| Personal Factors | 7.2% | “…A lot of thinking…well, what I got, I going to take it with me…I isn’t giving nobody nothing…cause it’s dealing with your life…it’s personal…” | |

| Social Justice | 6.2% | “…you really won’t know if they are using it for the right reason, giving it to someone really in need.” | |

Quantitative data

Questionnaire results were compared between registered organ donors and non-registered participants. The primary analytic approaches for dichotomous variables utilized Pearson Chi-square and Fisher exact test analyses. To summarize strength and direction of associations, odds ratio and their respective 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Data were expressed in mean ± standard deviation. The Student t test was used to compare means and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test was used to compare median values between registered organ donors and non-registered participants. Analyses were conducted using the SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC).

Mixed methods data analysis

Mixed methods data analysis and integration of the quantitative and qualitative results were performed at the completion of the separate analyses of the survey and focus group discussion data. Qualitative themes and categories, organized according to the constructs of the TPB, were compared with quantitative survey items in a joint display matrix (Table 3). The number of text references for qualitative categories were compared with the statistical test probability values for quantitative survey items to identify consistency in the participants’ viewpoints regarding becoming a registered organ donor.

Table 3.

Comparison of Qualitative and Quantitative Results

| TPB Constructs/ Qualitative Themes |

Related Categories |

% Text References |

Survey Items | % Yes/ True |

DV “Registered OD” N=87 (22 registered, 65 not registered) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Beliefs | |||||

| Advantages | Saving Someone’s Life | 51.6% |

|

76% | Donors 5.0 vs. non-Donors 3.9, p=0.04 |

| 82% | Donors 4.6 vs. non-Donors 3.9, p=0.19 | ||||

| Making It Your Own Decision | 20.0% |

|

77% | Donors 3.4 vs. non-Donors 2.3, p=0.01 | |

| Not Needing Organs When Dead | 18.3% |

|

67% | OR 15 (95% CI 1.9 – 121), p=0.0017* | |

| Disadvantages | Fear | 30.3% |

|

11% | Donors 3.0 vs. non-Donors 4.5, p=0.008 |

| Legal Issues | 21.2% |

|

77% | Donors 3.4 vs. non-Donors 2.3, p=0.01 | |

| Religious and Moral Beliefs | 10.6% |

|

7% | Donors 4% vs. non-Donors 8%, p=0.61 | |

| 6% | Donors 3.7 vs. non-Donors 4.1, p=0.49 | ||||

| 13% | Donors 3.5 vs. non-Donors 4.5, p=0.09 | ||||

| Social Justice | 7.6% |

|

11% | Donors 3.3 vs. non-Donors 4.4, p=0.05 | |

| 67% | Donors 64% vs. non-Donors 68%, p=0.72 | ||||

| Normative Beliefs | |||||

| Approving | Family and Friends | 68.3% |

|

36% | OR 3.1 (95% CI 1.1 – 8.8), p=0.035* |

| 64% | OR 2.0 (95% CI 0.6– 6.4), p=0.22* | ||||

| Health Care Providers | 16.3% |

|

10% | OR 9.4 (95% CI 1.7– 51.6), p=0.0032* | |

| Community | 8.2% |

|

59% | OR 7.1 (95% CI 1.5 – 34.0), p=0.0065* | |

| 33% | OR 2.5 (95% CI 0.9 – 7.3), p=0.085* | ||||

| Those in Need of Organs | 6.1% |

|

57% | OR (2.0 95% CI 0.7 – 6.1), p=0.20* | |

| 30% | OR 2.5 (95% CI 0.9 – 7.3), p=0.085* | ||||

| Disapproving | Family and Friends | 51% |

|

36% | OR 3.1 (95% CI 1.1 – 8.8), p=0.035* |

| Church and Religious Groups | 20.4% |

|

7% | Donors 4% vs. non-Donors 8%, p=0.61 | |

| 6% | Donors 3.7 vs. non-Donors 4.1, p=0.49 | ||||

| Community | 20.4% |

|

64% | OR 2.0 (95% CI 0.6– 6.4), p=0.22* | |

| Behavioral Control | |||||

| Facilitators | Information | 40% |

|

53% | Donors 4.9 vs. non-Donors 3.8, p=0.068 |

| Knowing Organ Recipients | 8.9% |

|

30% | OR 2.5 (95% CI 0.9 – 7.3), p=0.085* | |

| Religious Beliefs | 6.3% |

|

39% | Donors 4.9 vs. non-Donors 4.1, p= 0.17 | |

| Altruism | 6.3% |

|

64% | OR 5.3 (95% CI 1.3 – 20.4), p=0.01* | |

| 75% | OR 0.7 (95% CI 0.2 – 2.5), p=0.6* | ||||

| Trust | 3.8% |

|

92% | OR 0.4 (95% CI 0.1 – 3.1), p=0.38* | |

| 93% | OR 1.5 (95% CI 1.2 – 7.2), p=0.018* | ||||

| Barriers | Lack of Information | 41.2% |

|

39% | Donors 41% vs. non-Donors 38%, p=0.84 |

| 60% | Donors 59% vs. non-Donors 60%, p=0.94 | ||||

| 20% | Donors 23% vs. non-Donors 18%, p=0.66 | ||||

| 9% | Donors 14% vs. non-Donors 8%, p=0.40 | ||||

| Mistrust | 16.5% |

|

19% | Donors 2.6 vs. non-Donors 4.8, p=0.0002 | |

| 9% | Donors 3.1 vs. non-Donors 4.5, p=0.014 | ||||

| Fear | 12.4% |

|

6% | Donors 2.8 vs. non-Donors 4.6, p=0.001 | |

| Religious and Moral Beliefs | 8.2% |

|

4% | Donors 4.0 vs. non-Donors 4.2, p=0.71 | |

| 7% | Donors 23% vs. non-Donors 18%, p=0.66 | ||||

| Personal Factors | 7.2% |

|

7% | Donors 2.8 vs. non-Donors 4.6, p=0.002 | |

| Social Justice | 6.2% |

|

11% | Donors 3.3 vs. non-Donors 4.4, p=0.05 | |

| 63% | Donors 59% vs. non-Donors 64%, p=0.64 | ||||

Reference groups for all Odds Ratios are the non-registered participants.

Results

Demographics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Overall Sample and Characteristics by Donor Status

| All | Registered Donors |

Non- Registered |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | N=87 | N=22 | N=65 | |

| Age mean (range) | 50 (19 – 88) | 51.4 ± 20.3 | 49.2 ± 15.8 | 0.65 |

| Female gender | 65 (75%) | 68.4% | 80.8% | 0.34 |

| Children <18yr in house | 0.26 | |||

| 0 | 55 (63%) | 67.7% | 50.0% | |

| 1 | 10 (15%) | 10.8% | 27.3% | |

| 2 | 10 (15%) | 15.4% | 13.6% | |

| ≥3 | 5 (6%) | 6.2% | 9.1% | |

| Highest Education | 0.11 | |||

| High School or less | 26 (30%) | 22.7% | 32.3% | |

| Some College | 24 (28%) | 18.2% | 30.8% | |

| Bachelors | 20 (23%) | 36.4% | 18.5% | |

| Post-Graduate | 11 (16%) | 22.7% | 13.9% | |

| Household Income | 0.70 | |||

| <$20,000 | 25 (29%) | 33.3% | 27.0% | |

| $20,000 – 40,500 | 18 (21%) | 28.6% | 19.1% | |

| $40,500 – 60,000 | 18 (21%) | 14.3% | 23.8% | |

| >$60,000 | 17 (19%) | 19.1% | 19.1% | |

| Marital Status | 0.41 | |||

| Never Married | 16 (19.5%) | 18.2% | 20.0% | |

| Married/ Common-law | 42 (51.2%) | 54.6% | 50.0% | |

| Divorced/ Separated | 15 (18.3%) | 9.1% | 21.7% | |

| Widowed | 9 (11.0%) | 18.2% | 8.3% | |

| Employment | 0.24 | |||

| Retired | 29 (33%) | 45.5% | 30.5% | |

| Unemployed | 19 (22%) | 27.3% | 22.0% | |

| Part-time | 7 (8%) | 0 | 11.9% | |

| Full-time | 27 (31%) | 27.2% | 35.6% | |

| Religious Person | 0.35 | |||

| No | 2 (2%) | 3.1% | 0 | |

| Yes, somewhat | (40%) | 43.1% | 31.8% | |

| Yes, very | (54%) | 49.2% | 68.2% | |

| Attend Religious Services | 0.44 | |||

| Less than once/month | 11 (13%) | 9.1% | 13.8% | |

| 2–3 Times/ month | 19 (22%) | 18.2% | 23.1% | |

| About once/ week | 26 (30%) | 22.7% | 32.3% | |

| More than once/week | 32 (37%) | 50.0% | 30.8% |

Eighty-seven African American participants completed six focus groups. The mean number of participants was 14.5 (range 8 – 19). The sample consisted of 22 registered organ donors (ROD) and 65 non-registered participants (NRP). Most participants were women (75%) and the mean age was 50 (range 19–88) years. There were no significant differences in baseline measures between the groups. Focus Groups and Survey Findings (Tables 2 & 3).

Behavioral Beliefs: Advantages and disadvantages of becoming a ROD

The opportunity to save someone’s life emerged as the dominant qualitative theme about the advantages of becoming a registered organ donor accounting for 51.6% of text references and validated quantitatively to be a more dominant attitude in ROD compared to NRP (p=0.04). “Making your own [organ donation] decision” was also commonly referred to as an advantage of becoming a registered organ donor accounting for 20.0% of text references but there was near equivalent agreement between both ROD and NRPs regarding honoring a person’s wish to donate organs (p=0.84). The concept of “not needing organs when dead” accounted for 8.3% of text references and was a significantly prevalent attitude in ROD compared to NRPs (OR 15.0, 95% CI 1.9 – 121, p=0.0017). Two additional advantages to becoming an organ donor that were discussed by the participants were personal factors (6.6% of text references) and taking responsibility for your health (3.3% of text references). However, there were no quantitative questions to measure the association between these two themes and organ donor registration.

The biggest disadvantage to becoming a registered organ donor was fear, accounting for 30.3% of text references. RODs were much less likely to agree with donation fear statements (p=0.008). Legal issues and religious/moral beliefs also were brought up as disadvantages to becoming a registered organ donor although there were no significant differences in quantitative responses to questions probing these themes between ROD and NRPs. Organ usability was another disadvantage to becoming a registered organ donor commonly discussed, accounting for 16.6% of text references. Finally, registered donors were significantly less likely to agree with social justice statements regarding transplantation (p=0.05), although social justice themes only accounted for 7.6% of text references.

Normative Beliefs: Those who would approve or disapprove of a ROD

The most common groups of persons who were thought to approve of the decision to become a registered organ donor were family and friends accounting for 69.3% of text references. RODs were more likely to have had a conversation with their family about organ donation than NRPs (OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.1 – 8.8, p=0.035). Health care providers were also listed as approving of the decision to become a registered organ donor, accounting for 16.3% of text references. RODs were also more likely to have had a conversation with their physician about organ donation than NRPs (OR 9.4, 95% CI 1.7 – 51.6, p=0.0032). Community members (8.2% of text references) and those in need of organs (6.1% of text references) were also discussed as groups of persons who would approve of the decision to become a registered organ donor but there were no significant differences in quantitative responses to questions probing these themes between ROD and NRPs.

Family members were also identified as the most common persons to disapprove with becoming a registered organ donor, accounting for 51% of text references. Church and religious groups also were commonly (20.4% of text references) brought up as disapproving of the decision to become a registered organ donor but there were no significant differences in responses to questions probing these themes between ROD and NRPs. Similarly, community (20.4% of text references) was put forth as disapproving with the decision to become a registered organ donor but no differences were measured between ROD and NRPs.

Behavioral Control: Facilitators and barriers to becoming a ROD

The most common facilitating factor discussed in the focus groups was information, accounting for 40% of text references. There was a trend toward increased agreement with the question “I understand the organ donor process” in ROD compared to NRPs, although the difference was not statistically significance (p=0.068). The next most common facilitators discussed were family members needing an organ transplant and having a formal process in place for becoming an organ donor, each accounting for 16.4% of text references. Knowing the organ recipient (8.9% of text references) and religious beliefs (6.3% of text references) also were perceived as facilitators but there were no significant differences in quantitative responses to questions probing these themes between ROD and NRPs. RODs were more likely to acknowledge measures of altruism compared to NRPs (OR 5.3, 95% CI 1.3 – 20.4, p=0.01), although altruism themes only accounted for 6.3% of text references. Similarly, RODs responded more positively to questions measuring trust compared to NRPs (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.2 – 7.2, p=0.018), although trust themes only accounted for 3.8% of text references.

Many themes emerged when discussing barriers to becoming an organ donor. The lack of information was most commonly referenced (41.2%). In analysis of data from the quantitative questions, mistrust, fear and social justice themes all demonstrated significant differences between ROD and NRPs. Mistrust accounted for 16.5% of text references and was much less prevalent in ROD compared to NRPs (p=0.002). Fear accounted for 12.4% of text references and also was much less prevalent in ROD compared to NRPs (p=0.001). Similarly, social justice accounted for 6.2% of text references and was less prevalent in ROD compared to NRPs (p=0.05). Personal factors (7.2% of text references) were another significant theme that emerged with differences between ROD and NRPs (p=0.002). In contrast, there were no significant differences in quantitative responses to questions probing religious and moral beliefs, which accounted for 8.2% of text references.

Discussion

This study used a mixed methods approach to explore factors associated with choosing to become a registered organ donor in a sample of African Americans from the Deep South. The strength of this study lies in the identification of factors informed by the Theory of Planned Behavior. While previous research has identified factors associated with organ donation (add cites), few have proceeded from a strong theoretical foundation. The current study thus extends the organ donation research paradigm contributing new and novel insights about organ donation in the African American population. One novel finding from this study was the emergence of a self-perception that organs from African Americans are often unusable due to the higher prevalence of health issues compared to other races. Concerns about organ usability were discussed as a disadvantage to becoming an organ donor. One participant said, “…we probably have very little organs to donate with our lifestyle and eating habits.” It is important for community-based educational campaigns to emphasize that there often are donation options, even for patients with comorbid illnesses. An analogous theme was that being a registered organ donor might be a healthy stimulus prompting registered donors to take care of their own health, which was discussed as an advantage to being a registered organ donor.

Religious beliefs (5, 26–29), mistrust (2, 4,5, 26, 29–36), and social justice (2, 37–40) are common barriers to organ donation frequently cited in the literature. Interestingly, religious beliefs, mistrust and social justice were infrequently discussed during the focus groups in our study, accounting for few text references. There were no differences in measures of religiosity between the ROD and NRPs. In contrast, mistrust and social justice were statistically different between ROD and NRPs on the quantitative measurements. One issue is the relative importance of religious beliefs, mistrust and social justice barriers in predicting becoming a registered organ donor. Our data suggest that other factors may play a more dominant role in predicting the behavior of becoming a registered organ donor.

Fear and lack of information, in contrast, are commonly cited as barriers to organ donation in the literature and were commonly discussed in our focus groups.(5, 37,41–43) Three common fears cited in the literature are that being a donor will be a financial burden to their family, you will not get a proper burial and your body will be disfigured if you are a donor. (5, 37, 44) Addressing these fear-inducing misconceptions are an important part of informative organ donation educational campaigns. Information was the most common facilitator and lack of information was the most common barrier to becoming a registered organ donor. There were encouraging comments offered about the “younger generation” being informed thus increasing their willingness to become organ donors.

Our study reaffirms the importance of disseminating the decision to become an organ donor to family and friends, as has been frequently documented in the literature. (40, 42,45, 46) The survey results also confirm that individuals who have had a discussion about organ donation with their family and friends (or health care provider) are more likely to be an organ donor. Efforts to increase organ donor registration need to include mechanisms to ensure familial notification.

This study has several limitations. First, the participants were disproportionately female, older, highly educated and with incomes higher than the average incomes of African Americans in Alabama. Underrepresentation of males may be especially important, as studies have demonstrated that non-donation attitudes in African American males were more likely to be related to medical mistrust than in African American females.(47) Secondly, the quantitative questionnaire contained the nine-question organ donor readiness index (21) and select items from the National Minority Organ and Tissue Transplant Education Program (MOTTEP) (22) without further validity testing in this population. The questionnaire also included items developed specifically for the current study. The self-developed items on the questionnaire were not subjected to construct validity testing due to a small sample size. Third, despite attempts to (prospectively) include items on the questionnaire that would measure each qualitative theme discussed during the mock focus group, some new themes emerged during the focus groups (and thus after the questionnaire was developed) for which there were no matching quantitative items. This is consistent with the inductive nature of qualitative research and its ability to yield more in-depth exploration of the phenomenon of interest, and thus may also be a strength of the study.(48)

In summary, this study measured factors associated with choosing to become a registered organ donor in a sample of African Americans from the Deep South. Using a mixed methods approach helped not only produce more rigorous conclusions, but allowed better capturing of the nuances that may account for differences in the intentions to become or not to become a registered organ donor. Results from this study suggest new content and motivational messages to include in campaigns to increase African American donor registration.

Acknowledgments

Research was supported in part by a Charles Barkley Health Disparities Research Award (D. DuBay) and NIH NIDDK 1 K23 DK091514-01A1 (D. DuBay).

Abbreviations

- ROD

Registered Organ Donor

- NRP

Non-Registered Participants

- MOTTEP

Minority Organ and Tissue Transplant Education Program

- TPB

Theory of Planned Behavior

- UAB

University of Alabama at Birmingham

- OR

Odds Ratio

- 95% CI

95% Confidence Interval

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by Progress in Transplantation

References

- 1.Anonymous. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. [cited 2013 March 7]; Available from: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/.

- 2.Siminoff LA, Arnold R. Increasing organ donation in the African-American community: altruism in the face of an untrustworthy system. Annals of internal medicine. 1999 Apr 6;130(7):607–609. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-7-199904060-00023. PubMed PMID: 10189333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurz RS, Scharff DP, Terry T, Alexander S, Waterman A. Factors influencing organ donation decisions by African Americans: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2007 Oct;64(5):475–517. doi: 10.1177/1077558707304644. PubMed PMID: 17881619. Epub 2007/09/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siminoff LA, Saunders Sturm CM. African-American reluctance to donate: beliefs and attitudes about organ donation and implications for policy. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2000 Mar;10(1):59–74. PubMed PMID: 11658155. Epub 2001/10/20. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spigner C, Weaver M, Pineda M, Rabun K, French L, Taylor L, et al. Race/ethnic-based opinions on organ donation and transplantation among teens: preliminary results. Transplantation proceedings. 1999 Feb-Mar;31(1–2):1347–1348. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)02022-3. PubMed PMID: 10083597. Epub 1999/03/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DuBay D, Redden D, Haque A, Gray S, Fouad M, Siminoff L, et al. Is decedent race an independent predictor of organ donor consent or merely a surrogate marker of socioeconomic status? Transplantation. 2012 Oct 27;94(8):873–878. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31826604d5. PubMed PMID: 23018878. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3566527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene JC, Caracelli VJ. New directions for evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. Advances in mixed-method evaluation: The challenges and benefits of integrating diverse programs. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative adn qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Smith KC. Best practices for mixed methods research in health sciences. [cited 2013 March 7];2011 Available from: http://obssr.od.nih.gov/mixed_methods_research.

- 10.Kawamura Y, Ivankova N, Kohler C, Perumean-Chaney S. Utilizing mixed methods to assess parasocial interaction of one entertainment-education program audience. International Journal of Multiple Research. Approaches. 2009;3(1):88–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruffin MTt, Creswell JW, Jimbo M, Fetters MD. Factors influencing choices for colorectal cancer screening among previously unscreened African and Caucasian Americans: findings from a triangulation mixed methods investigation. Journal of community health. 2009 Apr;34(2):79–89. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9133-5. PubMed PMID: 19082695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: a meta-analytic review. The British journal of social psychology / the British Psychological Society. 2001 Dec;40(Pt 4):471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. PubMed PMID: 11795063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McEachan RR, Conner M, Taylor NJ, Lawton RJ. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the Theory of Planned Behaviour: a meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review. 2011;5(2):97–144. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fouad MN, Partridge E, Dignan M, Holt C, Johnson R, Nagy C, et al. Targeted intervention strategies to increase and maintain mammography utilization among African American women. American journal of public health. 2010 Dec;100(12):2526–2531. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167312. PubMed PMID: 21068422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wynn TA, Anderson-Lewis C, Johnson R, Hardy C, Hardin G, Walker S, et al. Developing a community action plan to eliminate cancer disparities: lessons learned. Progress in community health partnerships : research, education, and action. 2011 Summer;5(2):161–168. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0013. PubMed PMID: 21623018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anonymous. Alabama Rural Health Association. [cited 2013 March 7]; Available from: http://www.arhaonline.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreuger R, Casey M. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice C, Tamburlin J. A confirmatory analysis of the Organ Donor Readiness Index: Measuring the potential for organ donation among African Americans. Research on Social Work Practice. 2004;14:295–303. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callender CO, Hall MB, Branch D. An assessment of the effectiveness of the Mottep model for increasing donation rates and preventing the need for transplantation--adult findings: program years 1998 and 1999. Semin Nephrol. 2001 Jul;21(4):419–428. doi: 10.1053/snep.2001.23778. PubMed PMID: 11455531. Epub 2001/07/17. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall LE, Callender CO, Yeager CL, Barber JB, Jr, Dunston GM, Pinn-Wiggins VW. Organ donation in blacks: the next frontier. Transplantation proceedings. 1991 Oct;23(5):2500–2504. PubMed PMID: 1926452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis C, Randhawa G. The influence of religion on organ donation and transplantation among the Black Caribbean and Black African population--a pilot study in the United Kingdom. Ethnicity & disease. 2006 Winter;16(1):281–285. PubMed PMID: 16599384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubens AJ. Racial and ethnic differences in students' attitudes and behavior toward organ donation. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996 Jul;88(7):417–421. PubMed PMID: 8764522. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2608007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan SE. Many facets of reluctance: African Americans and the decision (not) to donate organs. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006 May;98(5):695–703. PubMed PMID: 16749644. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2569263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Creecy RF, Wright R. Correlates of willingness to consider organ donation among blacks. Social science & medicine. 1990;31(11):1229–1232. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90128-f. PubMed PMID: 2291119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minniefield WJ, Muti P. Organ donation survey results of a Buffalo, New York, African-American community. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002 Nov;94(11):979–986. PubMed PMID: 12443001. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2594182. Epub 2002/11/22. eng. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reitz NN, Callender CO. Organ donation in the African-American population: a fresh perspective with a simple solution. J Natl Med Assoc. 1993 May;85(5):353–358. PubMed PMID: 8496989. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2571809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell E, Robinson DH, Thompson NJ, Perryman JP, Arriola KR. Distrust in the healthcare system and organ donation intentions among African Americans. Journal of community health. 2012 Feb;37(1):40–47. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9413-3. PubMed PMID: 21626439. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3489022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Ibrahim SA. Racial disparities in preferences and perceptions regarding organ donation. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006 Sep;21(9):995–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00516.x. PubMed PMID: 16918748. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1831604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terrell F, Moseley KL, Terrell AS, Nickerson KJ. The relationship between motivation to volunteer, gender, cultural mistrust, and willingness to donate organs among Blacks. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004 Jan;96(1):53–60. PubMed PMID: 14746354. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2594755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuen CC, Burton W, Chiraseveenuprapund P, Elmore E, Wong S, Ozuah P, et al. Attitudes and beliefs about organ donation among different racial groups. J Natl Med Assoc. 1998 Jan;90(1):13–18. PubMed PMID: 9473924. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2608302. Epub 1998/02/25. eng. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNamara P, Guadagnoli E, Evanisko MJ, Beasley C, Santiago-Delpin EA, Callender CO, et al. Correlates of support for organ donation among three ethnic groups. Clin Transplant. 1999 Feb;13(1 Pt 1):45–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.t01-2-130107.x. PubMed PMID: 10081634. Epub 1999/03/19. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan SE, Cannon T. African Americans' knowledge about organ donation: closing the gap with more effective persuasive message strategies. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003 Nov;95(11):1066–1071. PubMed PMID: 14651373. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2594684. Epub 2003/12/04. eng. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan SE, Harrison TR, Afifi WA, Long SD, Stephenson MT. In their own words: the reasons why people will (not) sign an organ donor card. Health communication. 2008 Jan-Feb;23(1):23–33. doi: 10.1080/10410230701805158. PubMed PMID: 18443990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgan SE, Miller JK. Beyond the organ donor card: the effect of knowledge, attitudes, and values on willingness to communicate about organ donation to family members. Health communication. 2002;14(1):121–134. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1401_6. PubMed PMID: 11853207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacob Arriola KR, Robinson DH, Perryman JP, Thompson N. Understanding the relationship between knowledge and African Americans' donation decision-making. Patient education and counseling. 2008 Feb;70(2):242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.09.017. PubMed PMID: 17988820. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2254183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siminoff LA, Gordon N, Hewlett J, Arnold RM. Factors influencing families' consent for donation of solid organs for transplantation. JAMA. 2001 Jul 4;286(1):71–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.1.71. PubMed PMID: 11434829. Epub 2001/07/04. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haustein SV, Sellers MT. Factors associated with (un)willingness to be an organ donor: importance of public exposure and knowledge. Clin Transplant. 2004 Apr;18(2):193–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-0012.2003.00155.x. PubMed PMID: 15016135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamburlin J, C R. Exploring the use of the stages of change model to increase organ donations among African Americans. Journal of human behavior in the social environment. 2002;5(2):45–59. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Howard RJ. Organ donation decision: comparison of donor and nondonor families. Am J Transplant. 2006 Jan;6(1):190–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01130.x. PubMed PMID: 16433774. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2365918. Epub 2006/01/26. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Howard RJ. The instability of organ donation decisions by next-of-kin and factors that predict it. Am J Transplant. 2008 Dec;8(12):2661–2667. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02429.x. PubMed PMID: 18853951. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2588486. Epub 2008/10/16. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boulware LE, Ratner LE, Cooper LA, Sosa JA, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Understanding disparities in donor behavior: race and gender differences in willingness to donate blood and cadaveric organs. Medical care. 2002 Feb;40(2):85–95. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00003. PubMed PMID: 11802081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]