Abstract

Suicide is a serious public health concern, and it is partly genetic. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene has been a strong candidate in genetic studies of suicide (Zai et al, 2012; Dwivedi et al, 2010) and BDNF regulates the expression of the dopamine D3 receptor.

Objective

We examined the role of the BDNF and DRD3 genes in suicide.

Methods

We analyzed four tag single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in BDNF and 15 SNPs in the D3 receptor gene DRD3 for possible association with suicide attempt history in our Canadian sample of Schizophrenia (SCZ) patients of European ancestry (N=188).

Results

In this sample, we found a possible interaction between the BDNF Val66Met and DRD3 Ser9Gly SNPs in increasing the risk of suicide attempt(s) in our SCZ sample. Specifically, a larger proportion of SCZ patients who were carrying at least one copy of the minor allele at each of the Val66Met and Ser9Gly functional markers have attempted suicides compared to patients with other genotypes (Bonferroni p<0.05). However, we could not replicate this finding in samples from other psychiatric populations.

Conclusions

Taken together, the results from the present study suggest that an interaction between BDNF and DRD3 may not play a major role in the risk for suicide attempt, though further studies, especially in SCZ, are required.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, dopamine receptor DRD3, brain-derived neurotrophic factor BDNF, genetics, suicidal behaviour

2 INTRODUCTION

Suicides claim one million lives worldwide each year. They account for approximately 10% of deaths in schizophrenia (SCZ) patients (Meltzer and Baldessarini 2003). A meta-analysis of excess mortality rates in SCZ by Brown (Brown 1997) found suicides to be the leading cause of excess deaths in SCZ, accounting for 28% of the excess SCZ deaths. Twin studies support a genetic basis of suicidal behaviour (Voracek and Loibl 2007).

Reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels have been observed in suicide attempters (Deveci et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2007) as well as suicide victims (Dwivedi et al. 2003; Karege et al. 2005; Pandey et al. 2008). Our recent systematic synthesis of data documented that the low-functioning Met allele confer an overall risk for suicide (Zai et al. 2012).

BDNF plays a critical role in dopaminergic neuronal establishment (Baquet et al. 2005). The number of tyrosine hydroxylase-expressing dopaminergic neurons was reduced in the murine midbrain-hindbrain regions where the BDNF gene was selectively deleted (Baquet et al. 2005). BDNF also specifically regulates the in vivo expression of dopamine D3 receptor (DRD3) in the nucleus accumbens both during development and in adulthood (Guillin et al. 2001). The DRD3 gene has not been investigated in suicide. Nonetheless, a Taiwanese study reported an interaction between BDNF Val66Met and the functional DRD3 Ser9Gly polymorphism in susceptibility for bipolar disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder (Chang et al. 2013), where comorbid anxiety disorder increased the risk of suicidal behaviour (Hawgood and De Leo 2008).

In spite of gene expression and genetic association studies pointing towards a possible role of the BDNF gene in suicidal behaviour, the combined role of BDNF and DRD3 in suicidal behaviour in SCZ patients has not been studied. In a previous study, we tested for the possibility of an association of tag polymorphisms in the DRD3 and BDNF genes with SCZ (Zai et al. 2010). Here, we aim to follow up with a study of whether these polymorphisms are associated with history of suicide attempt in our sample of SCZ patients. In view of the evidences that point to a functional relationship between DRD3 and BDNF, we also aim to examine their single-marker interactions in suicide attempt. Finally, we postulate that genetic susceptibility to suicidal behaviour may act across diagnostic boundaries; thus we aim to examine the significant interactions that are observed in our SCZ sample in independent samples including psychiatric patients with bipolar disorder, major depression, or bulimia nervosa. This cross-disorder approach has gained recent attention in genome wide association studies of complex psychiatric disorders (Lee et al. 2013).

3 PATIENTS AND METHODS

3.1 Subjects

Discovery Schizophrenia sample – TS

The research participants in the Discovery Schizophrenia TS sample (N=203, average age 37.46 +/− 10.44 years, 70.7% males) were recruited from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto, Canada. We have included only participants of European ancestry, as indicated by self-reported ethnicities of grandparents, in this study. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R/IV for Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; (First et al. 1997)) was used as the primary diagnostic tool (Maxwell 1992). Patients who satisfied the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for SCZ or schizoaffective disorder were included (Association 1994), while patients with history of major neurological disorders, major substance abuse, and head injury with significant loss of consciousness were excluded from the study. Based on the SCID-I interview as well as examination of medical records, 188 SCZ probands have available suicide data, of which 55 had at least one suicide attempt during their lifetime up to the date of assessment. The study was approved by the CAMH Research Ethics Board.

Replication samples with various psychiatric diagnoses

The first replication sample (TB sample; N=192; average age 33.46 +/− 9.04 years; 39% males) consists of DSM-III-R/IV-diagnosed Bipolar Disorder participants of European ancestry recruited from CAMH. The characteristics of the overall sample have been reported previously (Lett et al. 2011; Muller et al. 2011). Within the TB sample, 179 participants (48 had at least one suicide attempt) were assessed for suicidal behaviour during the SCID-I interview and the information was corroborated by examination of their medical records. The second Bipolar Disorder (GBP) sample consists of 267 cases of European ancestry (average age=42.36 +/– 13.24 years; 39.3% males) recruited from CAMH. The overall sample has been described previously (Scott et al. 2009; Xu et al. 2014) and suicidal behaviour was assessed using the Scheduled Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN). Eighty two GBP participants had attempted suicide. The studies for TB and GBP were approved by the Research Ethics Board at CAMH. The Bulimia Nervosa (BN) sample consists of cases of European ancestry that were described in a previous paper (Yilmaz et al. 2011; Yilmaz et al. 2012). Briefly, the BN sample consists of 242 female participants of European ancestry (average age 25.93+/− 7.00 years) of which 239 were assessed for suicidal behaviour during SCID-I interview. Nine of these patients had attempted suicide at least once. The Research Ethics Boards at CAMH and University Health Network approved the BN study.

The Norwegian sample has been previously described (Finseth et al. 2013). In brief, a total number of 1009 psychiatric patients, including 526 Bipolar Disorder cases (NB sample: 304 BD I, 197 BD II and 25 BD NOS), 338 Schizophrenia cases (NS sample: 258 schizophrenia, 24 schizophreniform and 56 schizoaffective), and 145 cases with related psychosis spectrum disorders (94 other psychosis (delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder and psychotic disorder NOS), 51 major depressive disorder (MDD)) were included. All of the Norwegian samples were of European, the majority Norwegian, ethnicity. The patients were recruited through a national Norwegian multicenter study (TOP - BRAIN Study) from several psychiatric hospitals and out-patient clinics. All patients met DSM-IV criteria for their respective diagnosis using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) (Association 1994; First et al. 1997).

Life-time history of at least one suicide attempt was assessed in all patients. In 25 % of the sample this was obtained by asking the patients to disclose if they had made a serious suicide attempt in the past requiring medical attention, emergency room visit or hospitalization. In the remaining 75%, suicide attempt was defined as in SCID-I, i.e. a past suicide attempt due to depression and thoughts of death. Based on these data the patients were grouped dichotomously; suicide attempters and non-attempters. Clinical risk factors of SB in the sample have been described in detail previously (Finseth et al. 2012; Mork et al. 2012; Finseth et al. 2013).

DNA isolation and polymorphism genotyping

For the SCZ, TB, GBP, and BN samples, genomic DNA was purified from whole blood samples using non-enzymatic method previously described (Lahiri and Nurnberger 1991). Genotyping was done after the subjects had completed the follow-up, and all laboratory staff members were blind to suicide attempt status. In all, we genotyped 34 DRD3 and 14 BDNF polymorphisms in the discovery TS sample, of which 15 DRD3 and 4 BDNF polymorphisms were tagged using Haploview using minimum minor allele frequency of 0.2 and an r2 threshold of 0.8. The tag polymorphisms were genotyped using either TaqMan SNP genotyping assays (Life Technologies Inc.) at CAMH or a microarray platform (Illumina) (Hodgkinson et al. 2008) at the The Centre for Applied Genomics as described previously (Zai et al. 2010). For replication of the significant interaction finding, genotyping of the Val66Met and Ser9Gly polymorphisms in the TB, GBP, and BN repliation samples were done using TaqMan SNP genotyping assays at CAMH.

The Norwegian replication samples were genotyped at Expression Analysis (Durham, NC, USA) using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP array 6.0 (Affymetrix Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Quality control was performed using PLINK (Purcell et al. 2007). Details on quality control have been described previously (Finseth et al. 2013).

3.3 Statistical Analyses

Adherence to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was determined using the chi-square test in Haploview version 4 (Barrett et al. 2005). Analyses of SCZ cases with history of suicide attempt versus SCZ cases without were done using Fisher’s Exact Tests both in terms of allele frequencies and genotype frequencies. Haplotype analyses were done using UNPHASED version 3.1.5 (Dudbridge 2008) for the analysis of history of suicide attempt. Haplotypes with frequencies of less than 5% were excluded from the analyses. For multiple-testing correction, our study of nineteen single-nucleotide polymorphisms was equivalent to testing twelve independent markers (Nyholt et al. 2004; Li and Ji 2005). Thus, the significance threshold was adjusted to 0.0042. Gene-gene interaction analyses were performed using HELIXTREE (GoldenHelix; e.g., (Zai et al. 2008)), and the significant analyses (after Bonferroni correction) were validated with the R package Model-Based Multifactor Dimensionality Reduction version 2.6 (MB-MDR) (Calle et al. 2010) as well as SPSS version 15 (IBM). The significance of the model was determined by running 1000 permutations. The meta-analysis, which incorporated replication samples, was carried out in STATA version 8.

4 RESULTS

4.1 DRD3 and BDNF tag SNPs are not associated with suicidal behaviour in TS patients

Genotypes of the 15 tag DRD3 and four tag BDNF polymorphisms did not differ significantly from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for the Canadian European TS sample (p>0.05). We did not find sex distribution or average age at recruitment to be significantly different between TS patients who had attempted suicide and those who had not (p>0.05). To test for an association of suicidal behaviour, we compared the allele, genotype, and haplotype frequency distributions of TS patients who had had at least one suicide attempt to those who had not attempted suicide (Tables 1a, 1b). None of the tested DRD3 and BDNF SNPs was associated with suicidality in SCZ.

Table 1.

| a. Results from analysis of polymorphisms and 2- and 3-marker haplotypes in the DRD3 gene with suicide attempt in our Discovery Schizophrenia (TS) sample. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DRD3 marker window size |

1* | 2 | 3 | |||

| Suicide | Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No | |||

| P | ||||||

| rs905568 | C/C C/G G/G |

13/41 35/67 7/25 |

C G |

61/149 49/117 |

0.58 | 0.82 |

| P | 0.242 | P | 1.00 | |||

| rs7620754 | A/A A/G G/G |

27/73 25/49 3/11 |

A G |

79/195 31/71 |

||

| P | 0.544 | P | 0.80 | 0.88 | ||

| rs2399504 | G/G G/A A/A |

35/86 20/42 0/5 |

G A |

90/214 20/52 |

0.89 | |

| P | 0.378 | P | 0.89 | 0.66 | ||

| rs7616367 | T/T T/C C/C |

22/60 28/60 5/13 |

T C |

72/180 38/86 |

0.71 | |

| P | 0.751 | P | 0.72 | 0.93 | ||

| rs7611535 | A/A A/G G/G |

4/14 25/51 26/68 |

A G |

33/79 77/187 |

0.98 | |

| P | 0.612 | P | 1.00 | 0.98 | ||

| rs1394016 | C/C C/T T/T |

16/49 32/55 7/29 |

C T |

64/153 46/113 |

0.92 | |

| P | 0.091 | P | 1.00 | 0.21 | ||

| rs9825563 | T/T T/C C/C |

19/58 30/58 6/17 |

T C |

68/174 42/92 |

0.08 | |

| P | 0.408 | P | 0.55 | 0.70 | ||

| rs1800828 | G/G G/C C/C |

13/29 26/54 16/49 |

G C |

52/112 58/152 |

0.36 | |

| P | 0.588 | P | 0.42 | 0.56 | ||

| Ser9Gly | A/A A/G G/G |

18/56 32/57 5/18 |

A G |

68/169 42/93 |

0.06 | |

| P | 0.192 | P | 0.64 | 0.56 | ||

| rs7633291 | A/A A/C C/C |

33/78 21/50 1/5 |

A G |

87/206 23/60 |

0.71 | |

| P | 0.838 | P | 0.79 | 0.84 | ||

| rs167770 | C/C C/T T/T |

4/13 26/56 25/64 |

C T |

34/82 76/184 |

0.91 | |

| P | 0.746 | P | 1.00 | 0.91 | ||

| rs2134655 | A/A A/G G/G |

1/12 26/49 28/72 |

A G |

28/73 82/193 |

0.89 | |

| P | 0.139 | P | 0.80 | 0.85 | ||

| rs2399496 | A/A A/T T/T |

11/30 29/67 15/36 |

A T |

51/127 59/139 |

0.71 | |

| P | 0.955 | P | 0.82 | 0.69 | ||

| rs2087017 | C/C C/T T/T |

8/24 29/64 17/45 |

C T |

45/112 63/154 |

0.81 | |

| P | 0.766 | P | 1.00 | 0.86 | ||

| rs1025398 | A/A A/G G/G |

20/51 26/54 9/26 |

A G |

66/156 44/106 |

||

| P | 0.724 | P | 1.00 | |||

| b. Results from analysis of polymorphisms and 2- and 3-marker haplotypes in the BDNF gene with suicide attempt in our Discovery Schizophrenia (TS) sample. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

BDNF Marker window size |

1* | 2 | 3 | |||

| Suicide | Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No | |||

| P | ||||||

| rs7934165 | A/A A/C C/C |

13/37 31/61 11/35 |

A C |

57/135 53/131 |

0.51 | 0.35 |

| P | 0.445 | P | 0.91 | |||

| BDNF_2 | C/C C/T T/T |

4/7 21/41 29/85 |

C T |

29/55 79/211 |

||

| P | 0.456 | P | 0.22 | 0.15 | ||

| Val66Met | A/A A/G G/G |

3/7 22/34 30/91 |

A G |

28/48 82/216 |

0.35 | |

| P | 0.156 | P | 0.12 | 0.29 | ||

| rs1519480 | A/A A/G G/G |

28/69 25/52 2/12 |

A G |

81/190 29/76 |

||

| P | 0.394 | P | 0.71 | |||

p-value calculated from two-tailed Fisher’s Exact Test.

4.2 BDNF-DRD3 interaction, Suicidal behaviour in SCZ patients

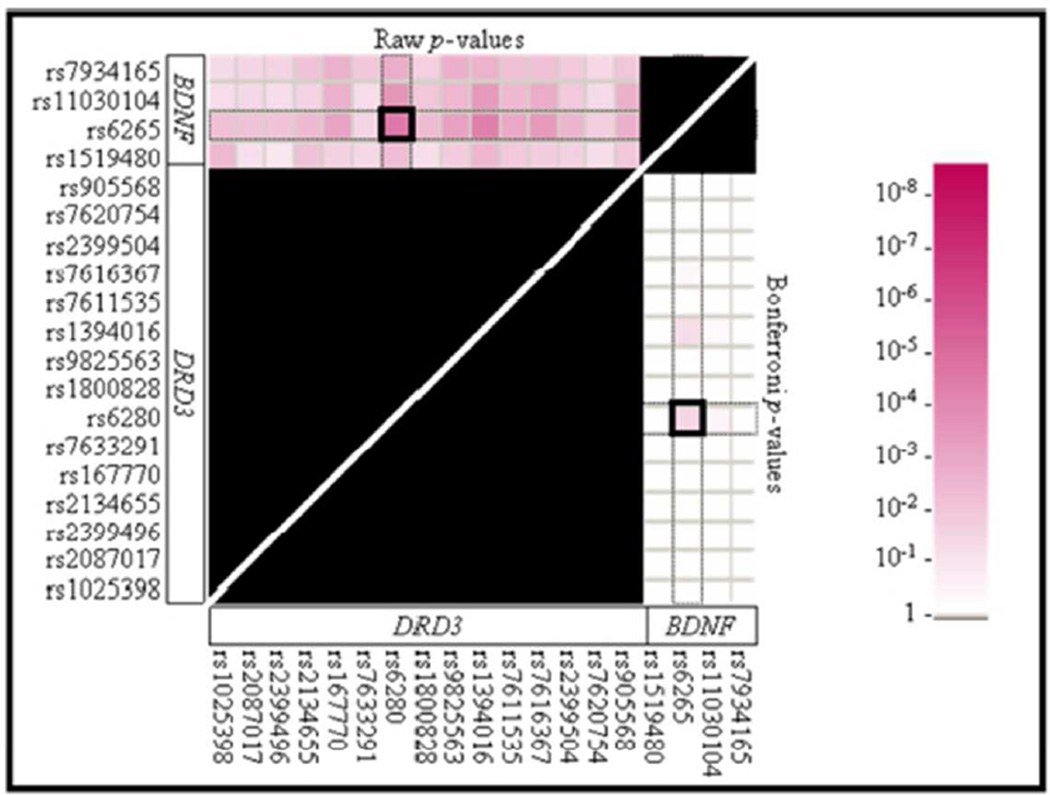

Because of the functional relationship between BDNF and DRD3 in vivo, we performed an interaction analysis between BDNF and DRD3 polymorphisms using HELIXTREE (Golden Helix Inc., Bozeman, MT). In our previous report, we did not find significant association between any BDNF-DRD3 two-marker combinations in SCZ diagnosis (Zai et al. 2010), but in the present study, we observed a significant interaction between BDNF Val66Met and DRD3 Ser9Gly in predicting lifetime suicide attempt (Figure 1; Bonferroni p<0.05). The results fom MB-MDR were also significant (permutation p=0.003). More specifically, SCZ patients who carried at least one copy of each rare variant of the Val66Met (A, Met) and Ser9Gly (G, Gly) were over-represented among the suicide attempters than other genotype combinations (20/36 or 56% of suicide attempters carrying at least one copy of the rare alleles for both markers, versus 35/149 or 23% of non-attempters carrying at least one copy of the rare alleles for both markers; OR=4.07; CI: 1.91–8.69).

Figure 1.

P-values from analyses of two-marker interactions between BDNF and DRD3 polymorphisms in association with the history of suicide attempt(s) in our Discovery Schizophrenia (TS) sample given by HELIXTREE program. Top left triangle indicates significance with the raw p-values, while the bottom right triangle indicates significance with Bonferroni adjusted p-values. Note that the interaction between BDNF Val66Met and DRD3 Ser9Gly was significant in history of suicide attempt(s). The black marked areas were included in the Bonferroni correction, but were not considered for the interaction results.

4.3 Replication of BDNF-DRD3 interaction

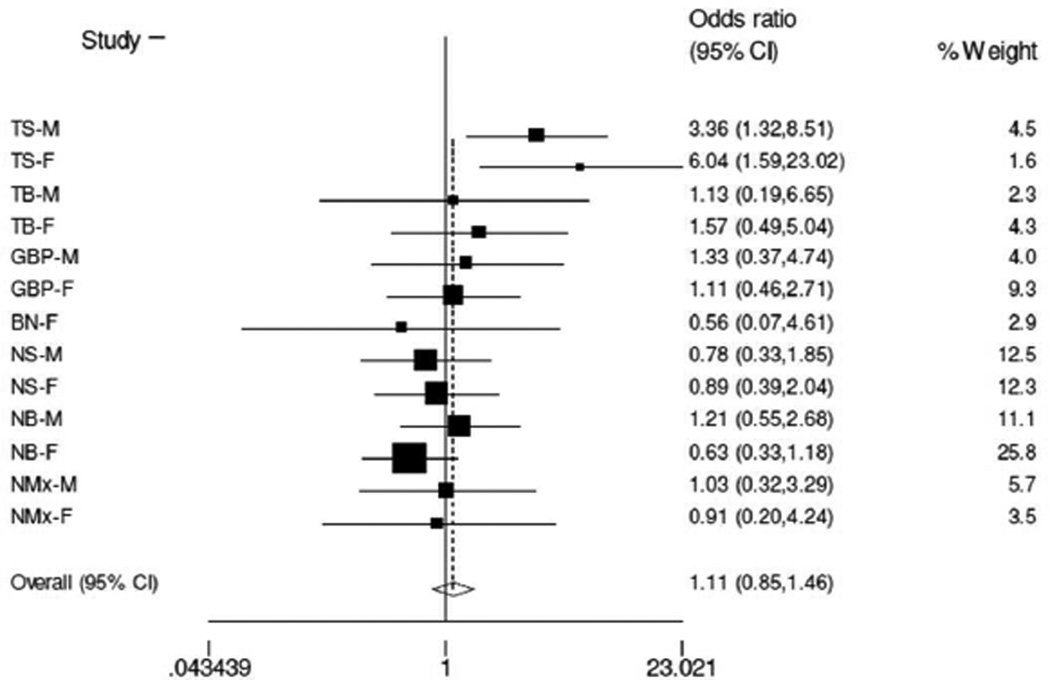

We were able to amass a large number of European samples with various psychiatric diagnoses (N=1694 total) in an effort to replicate the finding of the significant interaction between Ser9Gly and Val66Met that we observed in the TS sample with respect to history of suicide attempt. As shown by the forest plot (Figure 2), we were not able to replicate the findings in the meta-analysis with or without the discovery TS sample (including TS: OR= 1.11, 95% confidence interval: 0.85–1.46, P=0.438; excluding TS: OR= 0.92, 95% confidence interval: 0.68–1.24, P=0.574).

Figure 2.

Forest plot illustrating the overall effect of the presence of at least one copy of Gly9 and Met66 in suicide attempt across multiple psychiatric disorders (TS-M: discovery schizophrenia sample – males only; TS-F: discovery schizophrenia sample – females only; TBM: first bipolar disorder – males; TB-F: first bipolar disorder – females; GBP-M: second bipolar disorder – males; GBP-F: second bipolar disorder – females; BN-F: bulimia nervosa – females; NS-M: Norwegian schizophrenia sample – males; NS-F: Norwegian schizophrenia sample – females; NB-M: Norwegian bipolar disorder – males; NB-F: Norwegian bipolar disorder – females; NMx-M: Norwegian psychosis spectrum – males; NMx-F: Norwegian psychosis spectrum – females) in a meta-analysis.

5 DISCUSSION

This is the first comprehensive association study of DRD3 and BDNF polymorphisms with suicide. We did not observe any significant association for single SNPs or haplotypes, but we found a significant interaction between the functional polymorphisms Val66Met and Ser9Gly in the history of suicide attempt(s) in our SCZ Discovery sample.

As pointed out in the introduction, BDNF has been extensively investigated in SCZ with contrasting results (Neves-Pereira et al. 2005; Kanazawa et al. 2007; Squassina et al. 2010). Our findings confirmed the negative association of BDNF and SCZ, and discrepancies with previous reports of association could be explained by the evidence that BDNF variation is associated with psychiatric disorders with a primary affective component (Lencz et al. 2009), supporting the hypothesis that BDNF could exert a role on subphenotypes of SCZ (Schumacher et al. 2005).

The significant interaction between Val66Met and Ser9Gly in modulating the suicidal outcome led us to hypothesize that since the BDNF Val66Met Met allele has been associated with depression (Strauss et al. 2005; Martinowich et al. 2007; Ribeiro et al. 2007), and DRD3 Ser9Gly Gly allele has been associated with impulsivity (Retz et al. 2003), suicide attempts may require the interaction between the depressive and impulsive traits (Mann 2003).

Suicide attempters also appeared to be intolerant to delayed rewards (Liu et al. 2012);(Dombrovski et al. 2011);(Mathias et al. 2011). Moreover, it could be important to underline that testing interaction between polymorphisms of genes could prove the evidence of statistic epistasis that underlie the biological epistasis (Moore and Williams 2005). This assumption is further bolstered if the statistical interaction is between polymorphisms with functional roles, as in our study and gain importance in view of the genetic complexity of a neuropsychiatric disease like SCZ and suicidal behaviour, in which the polygenic hypothesis of its biological basis has been widely supported. Therefore, even though BDNF and DRD3 did not confer significant risk of suicide individually, the combination of the two genes, their functional polymorphisms, might be associated with increased suicide susceptibility. Even though the HELIXTREE analysis yielded a statistically significant interaction between the Ser9Gly and Val66Met SNPs in suicide attempt, we were unable to replicate this finding in other psychiatric samples. The discrepant findings could be due to a number of reasons. The discovery sample was relatively small; thus the possibility of false-positive finding, especially for the gene-gene interaction analysis, could not be ruled out. Our discovery sample had over 80% power to detect a genetic effect size of 1.95 to 2.17 for minor allele frequencies between 20% and 35% (alpha 0.05, additive model; (Gauderman and Morrison 2006)). The overall negative finding could also be due to insufficient size of the total sample to detect this interaction. Given the genetic architecture of the Norwegian population (Passarino et al. 2002), part of the genetic susceptibility of suicide in Norwegians may be distinct from that in other European populations. The average age of the BN sample was lower than other groups, and many of the BN patients could attempt suicide at a later time. In addition, the definition of suicide attempt included nonsuicidal self-injuries in the TS, TB, and GBP samples, while only serious suicide attempts were considered in the Norwegian samples. Thus, the heterogeneity in the definition of suicide attempt could have hampered the comparability of the samples. Moreover, the phenotype of suicide attempt for GBP was derived from the suicide severity item of SCAN; it reflects the suicide status during a depressive episode, but may not account for lifetime suicide attempt. In addition, the genetic components of suicidal behaviour may not overlap among the different psychiatric diagnoses (Bertolote and Fleischmann 2002; Harkavy-Friedman et al. 2004). Furthermore, factors including alcohol and substance use could have confounded the suicide findings and contributed to the heterogeneity of suicidal behaviour.

In summary, although the preliminary finding of a genetic interaction between BDNF and DRD3 in suicide attempt from our discovery SCZ sample was not replicated in other psychiatric samples (including SCZ), replications in additional independent SCZ samples with suicide attempt data are needed before the role of this interaction can be dismissed. The current study also encourages further studies of suicidal behaviour using different definitions and assessment tools to better decipher the role of these genes in this complex phenotype.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Grant 2PDF-00065-1208-0609-1209 awarded to [CCZ] from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Other funding sources include: Canadian Institutes for Health Research [JLK, JBV, VdL], Eli Lilly [CCZ], Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (NARSAD) [AKT, CCZ], STAGE program [VG], CAMH Foundation [VG], the Research Council of Norway (#217776, #223273) [OAA], and KG Jebsen Foundation and South-East Norway Health Authority (#2013-123) [OAA]. The collection of the IOP and CA2 samples was supported by funding from GlaxoSmithKline and CA1 from Pfizer.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF INTERESTS

JLK: honoraria from Roche, Novartis, and Lilly. CCZ: honorium from WebMD for Medscape review. JLK & CCZ: patent application “Genetic Markers Associated with Suicide Risk and Methods of Use Thereof” submitted. OAA: received speaker’s honoraria from GSK, Lilly, Otsuka, and Lundbeck. MM, IES, ZY, VdL, AKT, AS, GCZ, SAS, JS, NK, BLF, ASK, PIF, AEV, SD, and JBV reported no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baquet ZC, Bickford PC, Jones KR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for the establishment of the proper number of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6251–6259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4601-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. Suicide and psychiatric diagnosis: a worldwide perspective. World Psychiatry. 2002;1:181–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:502–508. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calle ML, Urrea V, Malats N, Van Steen K. mbmdr: an R package for exploring gene-gene interactions associated with binary or quantitative traits. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2198–2199. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YH, Lee SY, Chen SL, Tzeng NS, Wang TY, Lee IH, Chen PS, Huang SY, Yang YK, Ko HC, Lu RB. Genetic variants of the BDNF and DRD3 genes in bipolar disorder comorbid with anxiety disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;151:967–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveci A, Aydemir O, Taskin O, Taneli F, Esen-Danaci A. Serum BDNF levels in suicide attempters related to psychosocial stressors: a comparative study with depression. Neuropsychobiology. 2007;56:93–97. doi: 10.1159/000111539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski AY, Szanto K, Siegle GJ, Wallace ML, Forman SD, Sahakian B, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Clark L. Lethal forethought: delayed reward discounting differentiates high- and low-lethality suicide attempts in old age. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudbridge F. Likelihood-based association analysis for nuclear families and unrelated subjects with missing genotype data. Hum Hered. 2008;66:87–98. doi: 10.1159/000119108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y, Rizavi HS, Conley RR, Roberts RC, Tamminga CA, Pandey GN. Altered gene expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and receptor tyrosine kinase B in postmortem brain of suicide subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:804–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finseth PI, Morken G, Andreassen OA, Malt UF, Vaaler AE. Risk factors related to lifetime suicide attempts in acutely admitted bipolar disorder inpatients. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:727–734. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finseth PI, Sonderby IE, Djurovic S, Agartz I, Malt UF, Melle I, Morken G, Andreassen OA, Vaaler AE, Tesli M. Association analysis between suicidal behaviour and candidate genes of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Affect Disord. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I and II Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gauderman WJ, Morrison JM. QUANTO 1.1: A computer program for power and sample size calculations for genetic-epidemiology studies. 2006 In. [Google Scholar]

- Guillin O, Diaz J, Carroll P, Griffon N, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. BDNF controls dopamine D3 receptor expression and triggers behavioural sensitization. Nature. 2001;411:86–89. doi: 10.1038/35075076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkavy-Friedman JM, Nelson EA, Venarde DF, Mann JJ. Suicidal behavior in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: examining the role of depression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34:66–76. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.1.66.27770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawgood J, De Leo D. Anxiety disorders and suicidal behaviour: an update. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:51–64. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f2309d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson CA, Yuan Q, Xu K, Shen PH, Heinz E, Lobos EA, Binder EB, Cubells J, Ehlers CL, Gelernter J, Mann J, Riley B, Roy A, Tabakoff B, Todd RD, Zhou Z, Goldman D. Addictions biology: haplotype-based analysis for 130 candidate genes on a single array. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:505–515. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa T, Glatt SJ, Kia-Keating B, Yoneda H, Tsuang MT. Meta-analysis reveals no association of the Val66Met polymorphism of brain-derived neurotrophic factor with either schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2007;17:165–170. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32801da2e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karege F, Vaudan G, Schwald M, Perroud N, La Harpe R. Neurotrophin levels in postmortem brains of suicide victims and the effects of antemortem diagnosis and psychotropic drugs. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;136:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK, Lee HP, Won SD, Park EY, Lee HY, Lee BH, Lee SW, Yoon D, Han C, Kim DJ, Choi SH. Low plasma BDNF is associated with suicidal behavior in major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri DK, Nurnberger JI., Jr A rapid non-enzymatic method for the preparation of HMW DNA from blood for RFLP studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5444. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, et al. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat Genet. 2013;45:984–994. doi: 10.1038/ng.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencz T, Lipsky RH, DeRosse P, Burdick KE, Kane JM, Malhotra AK. Molecular differentiation of schizoaffective disorder from schizophrenia using BDNF haplotypes. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:313–318. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.050401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lett TA, Zai CC, Tiwari AK, Shaikh SA, Likhodi O, Kennedy JL, Muller DJ. ANK3, CACNA1C and ZNF804A gene variants in bipolar disorders and psychosis subphenotype. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12:392–397. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.564655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity (Edinb) 2005;95:221–227. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, Vassileva J, Gonzalez R, Martin EM. A comparison of delay discounting among substance users with and without suicide attempt history. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:980–985. doi: 10.1037/a0027384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:819–828. doi: 10.1038/nrn1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinowich K, Manji H, Lu B. New insights into BDNF function in depression and anxiety. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1089–1093. doi: 10.1038/nn1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias CW, Dougherty DM, James LM, Richard DM, Dawes MA, Acheson A, Hill-Kapturczak N. Intolerance to delayed reward in girls with multiple suicide attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011;41:277–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell E. The Family Interview for Genetic Studies: Manual. Washington, DC: Clinical Neurogenetics Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Mental Health; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Baldessarini RJ. Reducing the risk for suicide in schizophrenia and affective disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1122–1129. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JH, Williams SM. Traversing the conceptual divide between biological and statistical epistasis: systems biology and a more modern synthesis. Bioessays. 2005;27:637–646. doi: 10.1002/bies.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mork E, Mehlum L, Barrett EA, Agartz I, Harkavy-Friedman JM, Lorentzen S, Melle I, Andreassen OA, Walby FA. Self-harm in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16:111–123. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2012.667328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller DJ, Zai CC, Shinkai T, Strauss J, Kennedy JL. Association between the DAOA/G72 gene and bipolar disorder and meta-analyses in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:198–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves-Pereira M, Cheung JK, Pasdar A, Zhang F, Breen G, Yates P, Sinclair M, Crombie C, Walker N, St Clair DM. BDNF gene is a risk factor for schizophrenia in a Scottish population. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:208–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholt DR, Gillespie NG, Heath AC, Merikangas KR, Duffy DL, Martin NG. Latent class and genetic analysis does not support migraine with aura and migraine without aura as separate entities. Genet Epidemiol. 2004;26:231–244. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey GN, Ren X, Rizavi HS, Conley RR, Roberts RC, Dwivedi Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase B receptor signalling in post-mortem brain of teenage suicide victims. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:1047–1061. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarino G, Cavalleri GL, Lin AA, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Borresen-Dale AL, Underhill PA. Different genetic components in the Norwegian population revealed by the analysis of mtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:521–529. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retz W, Rosler M, Supprian T, Retz-Junginger P, Thome J. Dopamine D3 receptor gene polymorphism and violent behavior: relation to impulsiveness and ADHD-related psychopathology. J Neural Transm. 2003;110:561–572. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0805-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro L, Busnello JV, Cantor RM, Whelan F, Whittaker P, Deloukas P, Wong ML, Licinio J. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor rs6265 (Val66Met) polymorphism and depression in Mexican-Americans. Neuroreport. 2007;18:1291–1293. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328273bcb0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J, Jamra RA, Becker T, Ohlraun S, Klopp N, Binder EB, Schulze TG, Deschner M, Schmal C, Hofels S, Zobel A, Illig T, Propping P, Holsboer F, Rietschel M, Nothen MM, Cichon S. Evidence for a relationship between genetic variants at the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) locus and major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LJ, et al. Genome-wide association and meta-analysis of bipolar disorder in individuals of European ancestry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7501–7506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813386106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squassina A, Piccardi P, Del Zompo M, Rossi A, Vita A, Pini S, Mucci A, Galderisi S. NRG1 and BDNF genes in schizophrenia: an association study in an Italian case-control sample. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176:82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J, Barr CL, George CJ, Devlin B, Vetro A, Kiss E, Baji I, King N, Shaikh S, Lanktree M, Kovacs M, Kennedy JL. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor variants are associated with childhood-onset mood disorder: confirmation in a Hungarian sample. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:861–867. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voracek M, Loibl LM. Genetics of suicide: a systematic review of twin studies. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:463–475. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0823-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Cohen-Woods S, Chen Q, Noor A, Knight J, Hosang G, Parikh SV, De Luca V, Tozzi F, Muglia P, Forte J, McQuillin A, Hu P, Gurling HM, Kennedy JL, McGuffin P, Farmer A, Strauss J, Vincent JB. Genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder in Canadian and UK populations corroborates disease loci including SYNE1 and CSMD1. BMC Med Genet. 2014;15:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-15-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz Z, Kaplan AS, Zai CC, Levitan RD, Kennedy JL. COMT Val158Met variant and functional haplotypes associated with childhood ADHD history in women with bulimia nervosa. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:948–952. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz Z, Kaplan AS, Levitan RD, Zai CC, Kennedy JL. Possible association of the DRD4 gene with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in women with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:622–625. doi: 10.1002/eat.20986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zai CC, Manchia M, De Luca V, Tiwari AK, Chowdhury NI, Zai GC, Tong RP, Yilmaz Z, Shaikh SA, Strauss J, Kennedy JL. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene in suicidal behaviour: a meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:1037–1042. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zai CC, Romano-Silva MA, Hwang R, Zai GC, Deluca V, Muller DJ, King N, Voineskos AN, Meltzer HY, Lieberman JA, Potkin SG, Remington G, Kennedy JL. Genetic study of eight AKT1 gene polymorphisms and their interaction with DRD2 gene polymorphisms in tardive dyskinesia. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zai CC, Manchia M, De Luca V, Tiwari AK, Squassina A, Zai GC, Strauss J, Shaikh SA, Freeman N, Meltzer HY, Lieberman J, Le Foll B, Kennedy JL. Association study of BDNF and DRD3 genes in schizophrenia diagnosis using matched case-control and family based study designs. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:1412–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]