Abstract

Cellular plasticity is a major focus of investigation in developmental biology. The recent discovery that induced neuronal (iN) cells can be generated from mouse and human fibroblasts by expression of defined transcription factors suggested that cell fate plasticity is much wider than previously anticipated. In this review, we summarize the most recent developments of this nascent field and suggest criteria helping to define and categorize iN cells given the complexity of the neuronal identity.

Introduction

Somatic cell nuclear transfer and in vitro induction of pluripotency in somatic cells by defined factors provided unambiguous evidence that the epigenetic state of terminally differentiated somatic cells is not static and can be reversed to a more primitive state (Gurdon, 2006; Jaenisch and Young, 2008; Yamanaka and Blau, 2010). Inspired by these results, stem cell biologists have recently identified approaches to directly convert fibroblasts into induced neuronal (iN) cells, indicating that direct lineage conversions are possible between very distantly related cell types (Vierbuchen and Wernig, 2011). Importantly, iN cells can also be derived from defined endodermal cells. The reprogramming process both induces neuronal properties and extinguishes prior donor cell identity, and therefore represents a complete and functional lineage switch as opposed to generation of a chimeric phenotype. Since the discovery that MyoD, a key regulatory transcription factor in the skeletal muscle lineage, can induce many features of muscle cells in fibroblasts in the late 1980s, several other examples of remarkable cell-fate changes have been observed in response to forced expression of transcriptional regulators, but until recently it was assumed that this phenomenon is limited to closely related cell lineages (for discussion and historical background, see Graf, 2011, in this issue). After the initial description of iN cells, additional studies showed that fibroblasts can be directly converted to a diverse range of cell types, such as cardiomyocytes (Ieda et al., 2010;), blood cell progenitors (Szabo et al., 2010) and hepatocytes (Huang et al., 2011; Sekiya and Suzuki, 2011). In this review, we discuss the recent advances in direct lineage reprogramming towards the neuronal lineage and propose criteria that can be used to identify successfully reprogrammed iN cells.

Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to neurons

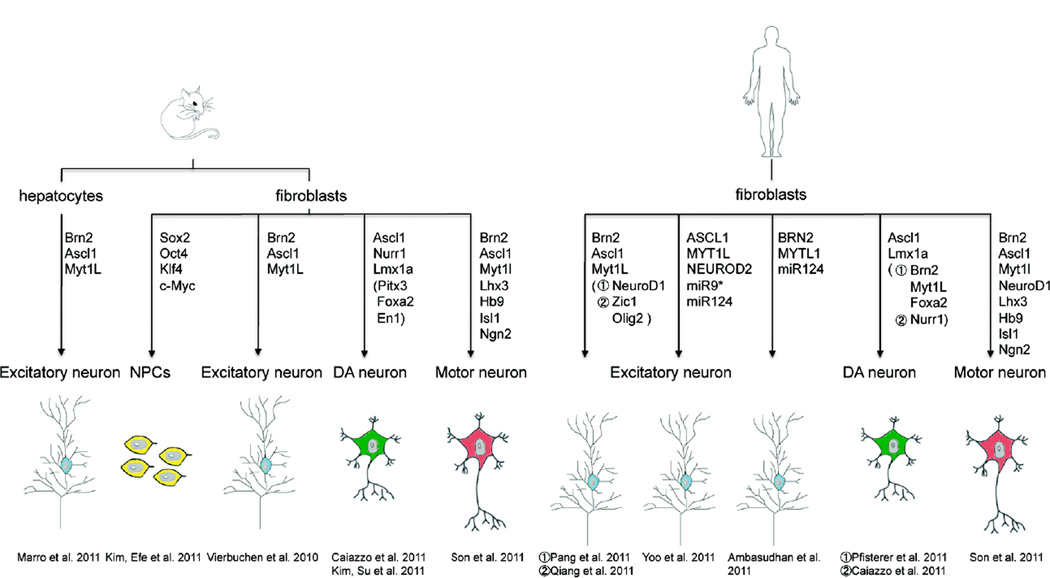

As transcription factors play key determining roles in cell fate specification, we hypothesized that forced expression of a combination of such factors may be sufficient to directly convert mouse fibroblasts into neuronal cells (Vierbuchen et al., 2010). Following lentiviral expression of 19 candidate genes we detected cells with neuronal morphologies and expression of neuronal markers suggesting such a conversion may indeed be possible. A systematic evaluation of different combinations revealed that the 5 transcription factors Ascl1, Brn2, Olig2, Zic1 and Myt1l are the most critical genes for this process. Out of those 5 factors the pool of Brn2, Ascl1 and Myt1l (BAM) was shown to be sufficient to induce neuronal cells that unexpectedly not only exhibited molecular but all principal functional properties of neurons (Figure 1). Even more surprising, the conversion efficiency of embryonic fibroblasts was estimated to be close to 20% within 2 weeks indicating that the conversion towards neuronal fates is substantially faster and more efficient than iPS cell formation. Also in contrast to induction of pluripotency, the iN cell reprogramming does not require cell proliferation, which is arguably a more favorable condition for epigenetic changes and a key mediator of iPS cell reprogramming (Hong et al., 2009; Kawamura et al., 2009; Li et al., 2009; Marion et al., 2009; Utikal et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Summary of all iN cell studies to date.

This first iN cell study raised many new questions that the field has now begun to address. Among other things, it was unclear what the exact cell of origin for iN cells was and whether endodermal cells could be coaxed towards iN cells. From a developmental point of view, it remained unresolved whether the reprogramming involved an intermediate neural progenitor cell, how similar iN cells are compared to bona fide neurons, whether iN cells possessed a regional identity and if modifying the combination of transcription factors would bestow a specific neural subtype identity. Chromatin biologists would be interested to know how complete the epigenetic landscape is remodeled towards a neuronal pattern and whether the reprogramming factors initiate the neurogenic program while suppressing the original cell fates or iN cells retain molecular "memories" of their cell of origin. Important for potential translational aspects the questions remained whether iN cells can functionally integrate into the brain and last but not least whether methods could be developed to generate human iN cells. In the past few months a number of reports have been published that provide the first answers to some of these questions and we will discuss those in the following sections.

A direct endoderm-to-ectoderm switch

In order to address some of these questions, we attempted to convert definitive endodermal cells into iN cells (Marro et al., 2011). Intriguingly, the exact same three reprogramming factors were sufficient to induce iN cells from primary liver cultures as from fibroblasts. Taking advantage of a well-characterized Albumin-Cre allele, we unequivocally confirmed that Albumin-expressing hepatocytes were the origin of iN cells, thereby demonstrating that transcription factor-mediated lineage reprogramming is possible across major lineage boundaries. We were also able to assess the transcriptional network dynamics during reprogramming and to compare the expression profile of fibroblast- and hepatocyte-derived iN cells. These results indicated that the timing of the two reprogramming processes is different and hepatocytes appear to be more resistant to the lineage switch. Moreover, we also explored how thoroughly iN cells are reprogrammed. We found that the donor cell type-specific expression signatures were robustly silenced in both fibroblast- and hepatocyte-derived iN cells. This led us to the remarkable conclusion that the exact same three transcription factors can not only induce a neuronal program but can also downregulate two unrelated donor transcriptional programs. Detailed gene expression analysis on the population and single cell level indicated that iN cells possess a small degree of epigenetic memory of their donor cells, but these transcriptional remnants decreased over time. It will be interesting to investigate the molecular mechanism underlying the transcriptional silencing that occurs, and to see whether it is similar to mechanisms that are used during cell fate specification in the embryo. Given the substantial differences between the fibroblast and liver transcriptional programs, it seems unlikely that the transcriptional silencing is directly mediated by the neuronal transcription factors themselves. Nevertheless, it is a formal possibility that the BAM factors target and inhibit a large number of key lineage-determining factors representing many non-neuronal cell fates. Alternatively, the mutual lineage switch could be caused by a more general mechanism. Perhaps when cells are becoming specified to one particular lineage a process becomes activated that leads to transcriptional silencing of many other lineage programs. For example, lineage-determining factors may have to compete for a finite amount of certain ubiquitously expressed and required co-factors, which would lead to suppression of undesired lineages once differentiating cells have committed to one lineage. E-proteins could potentially be one such critical co-factor as they are known to heterodimerize with many different lineage-specific bHLH transcription factors (Massari and Murre, 2000).

iN cells from human fibroblasts

Another important question that remained unclear after our initial publication was whether iN cells could also be generated from human fibroblasts. This issue is important, because potential clinical applications could only be realized with human cells. As the exact same four transcription factors can reprogram both mouse and human fibroblasts, into induced pluripotent cells, one might have expected that converting human fibroblasts to iN cells could be achieved in the same way to that used for mouse fibroblasts. However, when the BAM factors were introduced into human fetal fibroblasts the resulting cells remained immature and failed to generate action potentials when depolarized (Pang et al., 2011). This finding was later confirmed by another group that reported little reprogramming by the BAM factors in human cells in this case attributed to pronounced cell death (Qiang et al., 2011). We therefore screened 20 additional factors in combination with BAM and found that by introducing the bHLH factor NeuroD1, the generation of functional neuronal cells from human fibroblasts can be achieved. These human iN cells expressed a variety of neuronal markers including Tuj1, MAP2, NeuN, Neurofilament and Synapsin and exhibited functional neuronal properties as judged by measurement of action potentials. Moreover, when cultured with primary cortical neurons both spontaneous and evoked postsynaptic currents could be detected in these cells, demonstrating their synaptic maturation. However, the first functional synapses were found only after 5–6 weeks suggesting that the full maturation of human iN cells is a slow process. The same four factors could also convert postnatal foreskin fibroblasts into synaptically competent iN cells with comparable timing and efficiency. Like mouse iN cells, most of the human iN cells expressed mRNAs characteristic of glutamatergic neurons, such as vGLUT1 and vGLUT2. After downregulation of the exogenous transcription factors, the iN cells retained their stability, which indicated that an intrinsic program was established to maintain the newly adopted neuronal identity. The overall efficiency of generating human iN cells with four factors (2–4%) was about 10-fold lower than that of mouse with just three factors (compare to (Vierbuchen et al., 2010)). The observed species differences in the iN cell reprogramming may appear unexpected in light of the robustness of generating human iPS cells. However, upon closer inspection, the two different human reprogramming paradigms do share many similarities. The drop in human iPS cell reprogramming efficiency as compared to mouse is of a similar magnitude, especially when taking into account that only a small fraction of plated fibroblasts and only a small subset of these cells’ progenies are forming iPS cells. Similarly, it takes much longer for iPS cell-like colonies appear with human versus mouse fibroblasts. Thus, human cells in general appear to be less plastic and have a higher epigenetic “hurdle” for reprogramming to both iN and iPS cells. Finally, human ES cell-derived neurons require similar amounts of time to develop synaptic competence as human iN cells (Johnson et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007). Thus, long maturation time may be an inherent property of human cells, which is perhaps not surprising given that human brain development is orders of magnitude slower than in rodents.

In attempts to convert adult human fibroblasts to neurons, another group turned to using the 5 factors that we initially found in mouse to be the most critical of the 19 tested candidate factors. The resulting cells possessed a series of neuronal properties including certain functional properties such as the ability to generate action potentials when depolarized (Qiang et al., 2011). The acquisition of more mature functional properties such as synaptic transmission was less clear. This observation is similar to ours when adult fibroblasts were infected with BAM and Neurod1 (Pang et al., 2011). Nevertheless, iN cells were generated from Familial Alzheimer’s Disease (FAD) patients with mutations in PRESENELIN genes and were found to exhibit disease-specific traits, providing important proof-of-concept that iN cells can be used to model human disease. Specifically, the FAD-iN cells showed the presence of amyloid precursor protein (APP) puncta in endosomes, which was not readily detected in the originating FAD fibroblasts. This phenotype could be rescued by overexpression of wild-type PRESENELIN1. Of note, one of the reprogramming factors used in this study is Olig2, another member of bHLH family. Olig2 is not specific to neurons and can promote both neuronal and oligodendroglial fates depending on the developmental context (Mizuguchi et al., 2001; Novitch et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2002; Park et al., 2002; Takebayashi et al., 2002). However, in contrast to Ascl1 and NeuroD1, Olig2 is thought to act as a repressor, and associate with Ngn2 and E47 to antagonize their neurogenic effect (Lee et al., 2005). Future work will need to elucidate the function of these transcription factors during reprogramming. As a number of different transcription factor combinations can induce neuronal cells, there may be several parallel pathways to the neuronal lineage. Alternatively, the different transcription factors may eventually activate the same core program to induce neuronal identity.

The fact that the vast majority of reprogramming factors known to date are transcriptional regulators is not surprising given their ability to efficiently activate gene expression, and it also fits with the idea that there are “master regulators” and “terminal selectors” for specific lineages (Weintraub et al., 1989, Hobert, 2011). It is surprising, however, that miRNAs, which are thought to function predominantly through downregulation of gene activity, seem to be very powerful agents to mediate reprogramming. Two independent groups have recently derived human and mouse iPS cells by adding miRNAs, in the absence of any additional transcription factors (Anokye-Danso et al., 2011; Miyoshi et al., 2011). Similarly, Yoo et al. 2011 showed that by introducing miR-9/9* and miR-124, human fibroblasts can be reprogrammed into cells with neuron-like morphologies expressing the pan-neuronal marker MAP2. While these phenotypic changes are truly remarkable, the miRNAs alone were not sufficient to induce functional iN cells. However, the addition of the transcription factors NEUROD2, ASCL1, and MYT1L greatly increased the conversion efficiencies and led to the formation of iN cells from fetal and adult human fibroblasts with all the major functional properties of neurons, including synapse formation. Intriguingly, also this report underscored the essential role of bHLH transcription factors for generation of human iN cells. miR-9* and miR-124 are specifically expressed in post-mitotic neurons and were shown to repress the expression of SWI/SNF complex subunit Baf53a. When neural progenitor cells exit the cell cycle and differentiate into neurons, Baf53a is replaced by Baf53b and this switch is functionally relevant (Yoo et al., 2009). Therefore, one possibility was that the miRNAs facilitated reprogramming through promoting this BAF complex subunits switch. However, prolonging the expression of BAF53a did not abolish the conversion from fibroblasts to neurons and therefore downregulation of this miRNA target does not seem to be critical in this context (Yoo et al., 2011). Since Pang and colleagues showed iN cell induction by Neurod1, Ascl1, Myt1l, and Brn2, it appears that the miRNAs are able to replace the transcription factor Brn2 (Pang et al., 2011). This idea was not tested directly, however, and it is possible that the miRNAs work through yet another mechanism. More recently, another group also found miR-124 to be beneficial for human iN cell formation (Ambasudhan et al., 2011). In this report the miRNA was combined with BRN2 and MYT1L, further supporting the idea the miRNAs have a complementary function to Brn2. Surprisingly, no bHLH transcription factors were used in the latter report, but also the cells appeared less completely reprogrammed based on the absence of convincing evidence for synaptic competence. Future studies on the miRNA-transcription factor interplay responsible for iN cell formation could also be relevant to regular neural development. Thus, this extremely non-physiological method of reprogramming could perhaps even become a discovery tool for understanding normal development.

Induction of Specific Subtypes of Mouse and Human iN cells

For clinical and experimental use of iN cells, it would be desirable to develop ways to generate neurons with neurotransmitter- and region-specific phenotypes. Liver- and fibroblast-iN cells generated with the same reprogramming factors displayed properties characteristic of excitatory neurons. While this does not imply the acquisition of a specific region-specific phenotype, this finding could mean that the glutamatergic fate is a default fate as has been suggested for ES cell differentiation systems (Tropepe et al., 2001; Gaspard et al., 2008). Alternatively, the choice of transcription factors could have specifically induced an excitatory subtype. Therefore, the question arises of whether inclusion of subtype-specific transcription factors in the reprogramming cocktail could direct cells into other desired subtypes.

This hypothesis was elegantly tested by Son et al. who attempted to generate iN cells with motor neuron identity directly from fibroblasts (Son et al., 2011) (Figure 1). Starting out with a fairly large pool of transcription factors critical for motor neuron specification, they eventually found that four (Lhx3, Hb9, Isl1 and Ngn2) in combination with the BAM factors generated Hb9-positive neurons with an efficiency of up to 10% from MEFs. Gene expression analyses indicated that these induced motor neuronal (iMN) cells resemble the transcription profiles of embryonic and ESC-derived motor neurons. Besides displaying electrophysiological properties akin to motor neurons, these iMN cells also formed functional synaptic connections with myotubes. When transplanted to the developing chick spinal cord, most of the iMN cells were engrafted in the ventral horn of the spinal with axons projecting into the ventral roots. In addition, the cells behaved similarly to ESC-derived motor neurons in disease conditions. When cultured with glia carrying the G93A mutation in the Superoxide dismutase (Sod1) gene, a mutation found in familial forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the survival of iMN cells decreased. Vice versa, iMN cells derived from Sod1G93A MEFs also showed reduced survival when cultured with wild-type glia. These first translational studies suggest that iMN cells can be used as a tool to understand the pathophysiology of ALS. As a first step in this direction, Son et al. also infected human ESC-derived fibroblast-like cells with the 7 transcription factors in combination with Neurod1. This approach yielded neuronal cells that could fire action potentials and expressed Hb9 and vesicular ChAT. More work is needed to investigate whether iMN cells can be generated from primary human fibroblasts.

Another clinically relevant neuronal subtype that has been under intense investigation is the group of midbrain dopaminergic (DA) neurons, which are preferentially affected in Parkinson’s disease. Recently, two important proof-of-principle studies described the generation of iN cells expressing tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis (Caiazzo et al., 2011; Pfisterer et al., 2011). Pfisterer et al. showed that Lmx1a and Foxa2, when used in conjunction with the BAM pool, are capable of generating iN cells expressing TH, Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC), another crucial enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis, and importantly, Nurr1, a marker of midbrain identity. However, the cells did not express other midbrain markers and were not able to release dopamine into the media. Another report by Caiazzo et al. demonstrated the generation of mouse iN cells with dopaminergic features by expression of the transcription factors Ascl1, Nurr1 and Lmx1a. The efficiency of induction of TH-positive cells was reported to be 18% relying on a TH-EGFP transgenic reporter line. The TH-positive cells co-expressed vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), dopamine transporter (DAT), aldehyde dehydrogenase 1a1 (ALDH1A1), and calbindin. In contrast to the BAM/Foxa2/Lmx1a cells described by Pfisterer et al., the Ascl1/Nurr1/Lmx1a iN cells were able to release dopamine as determined by amperometry and HPLC analysis, indicating that the cells possessed an important functional property of dopamine neurons. Intriguingly, similar results could be obtained using human fibroblasts and the same reprogramming factors. However, the cells generated in this study did not express any regional markers specific to midbrain and displayed immature morphologies. Moreover, the authors did not investigate whether the cells were competent to receive synaptic input. Therefore, despite the use of midbrain dopamine neuron-specific transcription factors for reprogramming, only generic dopamine neuron and no midbrain-specific features were observed, suggesting incomplete reprogramming. Similarly, genome-wide transcriptional profiling showed substantial differences between the reprogrammed and brain-derived dopamine neurons.

As a cautionary note, the absence of midbrain character is a critical limitation for clinical application, since only “authentic” human midbrain dopamine neurons are able to restore function in animal models of Parkinson’s disease (Kriks et al., 2011; Roy et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2008). Therefore, yet another group very recently attempted to generate iN cells that are more reminiscent of midbrain dopamine neurons (Kim et al., 2011). This time transcription factor combinations were screened to induce EGFP fluorescence in Pitx3:EGFP knock-in fibroblasts, a locus highly specific for midbrain dopamine neurons. Surprisingly, EGFP+ cells were readily detected with a combination of two factors Ascl1 and Pitx3. Complementation with another four factors (Nurr1, Lmx1a, Foxa2, and En1) as well as the patterning factors Shh and FGF8 further enhanced the number of EGFP+ cells. The EGFP+ cells also expressed the generic dopamine neurons markers TH, DAT, AADC, and VMAT2 and were able to release dopamine. However, when tested in vivo, the cells only partially restored dopamine function and when a series of midbrain markers were analyzed both the 2-factor and the 6-factor iN cells failed to reach similar transcription levels found in embryonic or adult midbrain dopamine neurons. This finding leads to the somewhat sobering conclusion that even 6 transcription factors may still not be sufficient to fully reprogram fibroblasts to this specific neuronal subtype.

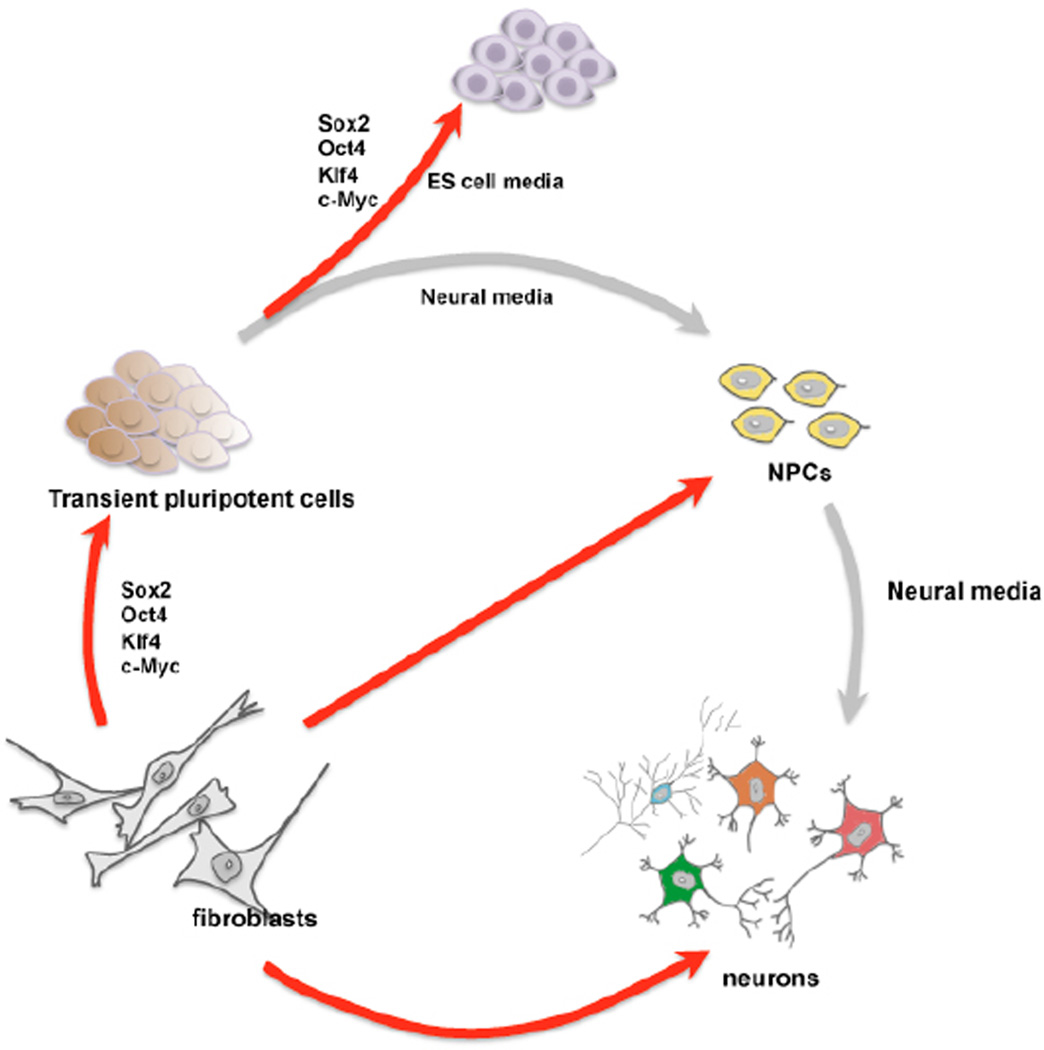

Directly generating terminally differentiated neurons could be useful in disease modeling and transplantation studies. However, a clear limitation of postmitotic iN cells is the inability to expand once reprogrammed. Large numbers of cells will be required for cell replacement-based therapies in a clinical setting, or for drug screening. Therefore, it would be desirable to induce expandable neural precursor cells directly from fibroblasts. Recently, Ding and colleagues successfully converted mouse fibroblasts to induced neural precursor cells (iNPCs) (Kim et al., 2011). In this study, the recipe for reprogramming was not tailored to the target cell type but instead identical to the iPS cell reprogramming factors (Figure 2). However, unlike for iPS cell formation, the factors were induced only for a short time, and the cells were then exposed to media favoring the growth of neural progenitor cells. After optimization of timing and culture conditions, colonies appeared that closely resembled neural rosette cells and expressed several relevant markers. Upon spontaneous differentiation, these iNPCs could give rise to multiple neuronal subtypes and astrocytic cells, indicating that the iNPCs were at least bi-potential neural precursor cells, but cells with oligodendrocytic characteristics were not seen; notably, a very similar approach was also used to generate cardiomyocytes and blood progenitor cells from fibroblasts (Szabo et al., 2010; Efe et al., 2011). In these studies, the authors claimed that the observed transdifferentiation bypassed an intermediate pluripotent stage because no Oct4 transcripts were observed in the cell population and the short reprogramming factor expression was not compatible with iPS cell generation. However, as the same approach can generate multiple somatic as well as pluripotent lineages, the simplest explanation is that short-term expression of the pluripotency reprogramming factors indeed induces a transient pluripotent state, but this state is unstable and prone to differentiation, and cannot be stabilized by environmental cues only (Figure 2). Future studies will address whether a “direct” conversion between fibroblasts and neural progenitors is possible using neural transcription factors (Figure 2). Although this approach is intriguing, the efficiency of forming rosette-like colonies appeared low and the cells could not be expanded well. It remains to be seen what the communalities and differences of these indirect and direct iNPCs will be and whether such unstable pluripotent cells can also be generated from human fibroblasts.

Figure 2. Direct versus indirect reprogramming.

Long expression of the 4 Yamanaka factors lead to iPS cell formation when grown in ES cell media. Short expression induces a transient, unstable pluripotent state that can be quickly differentiated into neural precursors or cardiomyocytes depending on the media components. Direct reprogramming (e.g. iN cell reprogramming) does not involve a pluripotent intermediate stage. Red arrows: reprogramming, grey arrows: differentiation.

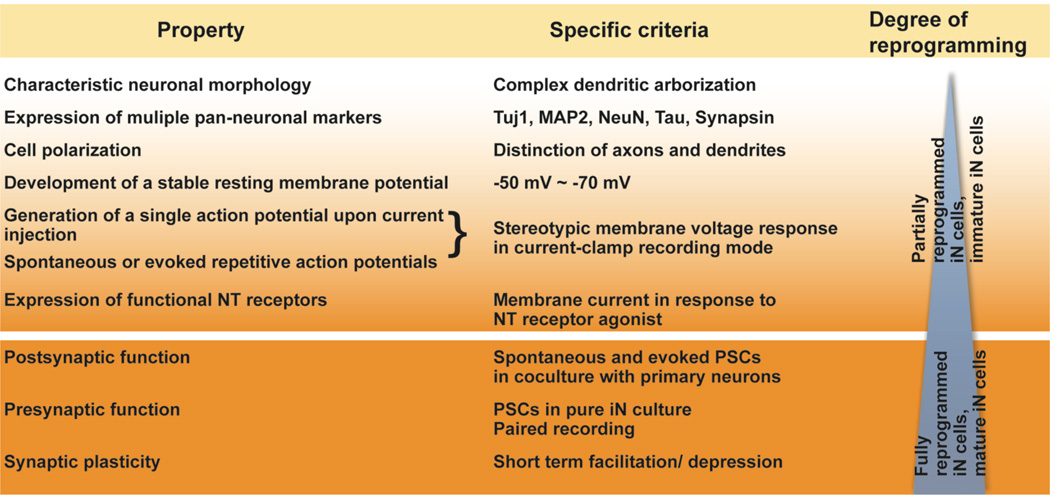

Defining criteria for iN cells

In recent months there has been a wave of reports published describing various methods to generate iN cells of various sorts. Given the infancy of the field, different criteria were applied to define converted neuronal cells, complicating the direct comparison of the different approaches. Consistent standards would be helpful, and we would therefore like to suggest here a panel of criteria that can be used to define iN cells of various degrees of reprogramming. First, we propose the term “induced neuronal cells (iN cells)” as opposed to “induced neurons”, to contrast reprogrammed cells with brain-derived cells. Second, we propose that the term “iN cell” should only be endorsed when the extent of reprogramming can be documented as being reasonably complete. In a nutshell, we believe fully reprogrammed iN cells should have a distinct neuronal morphology, express neuron-specific gene products, and exhibit the two principal functional properties of neurons: action potentials and synaptic transmission. This is equivalent to the validation of in vitro-generated neurons from neural or embryonic stem cells in previous work (Song et al., 2002; Vicario-Abejon et al., 2002; Wernig et al., 2004). Cells exhibiting only a subset of these properties should be termed “partially-reprogrammed iN cells”. Since the reprogramming process mimics neuronal maturation the term “immature iN cells” could be used alternatively. We would like to point out though that it is difficult to distinguish these two conceptionally very different interpretations.

Despite the great diversity of neurons in the nervous system, there are a number of typical properties shared by the vast majority of neurons. First, neurons have common morphological features. They are characterized by a cellular polarization and typically extend multiple arborizing dendrites and one single axon from the cell body (soma). Because of these unique structural properties, neurons also express specific cytoskeletal proteins such as neurofilaments, microtubules and microtubule-associated proteins. In addition, neurons have unique membrane characteristics with the presence of numerous constitutively open, voltage-gated, or transmitter-dependent, ion channels and intracellular second messenger-regulated metabotropic receptors. Together, these proteins confer the passive and active membrane properties of neurons. Finally, neurons are characterized by their ability to form synapses, which are specialized cell-cell contacts between an axon terminal and the soma or a dendrite where neurotransmission takes place. Please note, that not all neurons receive synaptic input from other neurons (e.g. primary sensory neurons), every neuron has output function and in most cases in form of synapses with other neurons (neuromodulatory neurons such as dopamine neurons are believed to not form classical synapses).

Building on the generic properties of neurons, we would like to propose criteria to define a fully reprogrammed iN cell (Figure 3). Similar to the maturation process of cultured primary neurons, reprogramming fibroblasts gradually and asynchronously acquire the full set of neuronal properties over time (Vierbuchen et al., 2010). Therefore, at any given time there will be a heterogeneous population containing iN cells that are reprogrammed to different degrees and thus display a range of neuronal features. Figure 3 shows such properties in the order of stringency, which is roughly also the order of appearance in reprogramming iN cells or neurons during development. These properties, therefore, can serve as criteria to help define the degree of reprogramming/ maturation stage of iN cells.

Figure 3. Neuronal properties in order of stringency (maturation/ extent of reprogramming).

Abbreviations: NT neurotransmitter, MAP2 microtubule associated protein 2

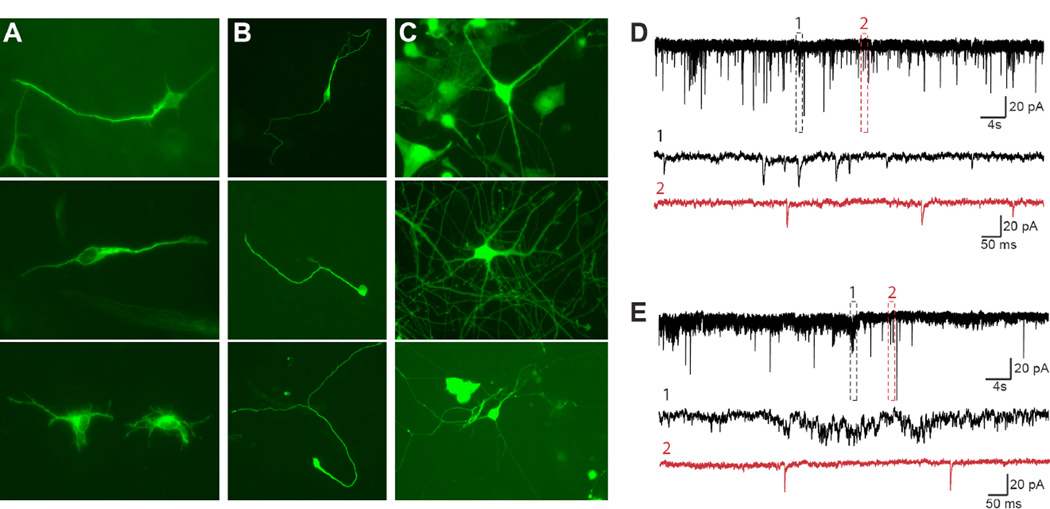

The earliest notable changes of converted iN cells are morphological, with the generation of a round soma protruding one small and thin process (Vierbuchen et al., 2010, see also Figure 4B). Gradually, more processes are generated which begin to branch. At first all neurites express both axonal and dendritic markers but early during differentiation one process gains characteristics of an axon whereas the remaining neurites become dendrites (e.g. MAP2 vs. Tau, see Silverman et al., 2001). During early stages of neurogenesis, newly born neurons become immunoreactive for the nuclear epitope NeuN (Mullen et al., 1992) and Poly-Sialated Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (PSA-NCAM) (Bonfanti et al., 1992).

Figure 4. Examples of morphological and electrophysiological criteria of iN cells.

A, Tuj1-positive fibroblasts extending one or more fairly thin cellular process. B, Immature iN cells extending one or two long branching neuritis from their soma. C, More mature iN cell morphologies characterized by multiple, long, branching processes extending from the cell body. Often iN cells sit on top of a dense network of neuritis derived from surrounding cells. D, A voltage clamp recording of spontaneous PSCs. The baseline is fairly tight and there is only little noise detectable. Both clusters of spikes (region 1, black) and separated spikes (region 2, red) represent most likely postsynaptic events as seen by higher time resolution (lower black and red traces). PSCs are typically of asymmetric shape with a fast deviation from the baseline followed by a slow rectification. E, A trace in the same recording mode with a much noisier baseline. Region 1 shows a group of spikes with similar amplitude deviation as in D. Higher resolution (lower black trace) reveals high levels of baseline fluctuation precluding the identification of PSCs. Other areas in the same trace (e.g. region 2, red trace) contain spikes that most likely represent synaptic currents.

During iN cell reprogramming, both passive and active membrane properties gradually approach the levels seen in primary cultured neurons (Vierbuchen et al., 2010). The resting membrane potential becomes more hyperpolarized and the capacitance increases as the cell volume increases. The input resistance also decreases, presumably as a result of the appearance of more neuronal membrane channel proteins. As for passive membrane properties, under current clamp recording mode, action potential-like responses induced by depolarization grow to resemble the mature stereotypic shape with increasing amplitudes and narrowing widths. A mature, all-or-none action potential is characterized by constant and high amplitude irrespective of the induction-trigger shape and current, with a fast depolarization and fast repolarization. The rapid repolarization ensures the regeneration of voltage-gated Na+ channels, which enables mature cells to fire a series of action potentials (Koester and Siegelbaum; Lockery et al., 2009). Therefore, the presence of repetitive action potentials is a clear sign that the ion-channels responsible for generating action potentials are properly orchestrated. Repetitive action potentials occur spontaneously or can be evoked by injecting currents. However, the presence of spontaneous action potentials does not necessarily mean that the cells are receiving excitatory synaptic input, as both spontaneous membrane fluctuations as well as various pace-making channels (e.g. hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels) can cause spontaneous firing. The development of passive and active membrane properties is facilitated by but not dependent on the presence of glial cells (Wu et al., 2007). By contrast, however, the formation of functional synapses requires factors secreted by glial cells (Banker, 1980; Eroglu and Barres, 2010). Morphological evidence of synapse formation can be obtained by high-resolution fluorescence microscopy showing a presynaptic vesicle protein such as synapsin, synaptophysin, or synaptotagmin localized in small puncta in close proximity to MAP2-positive dendrites. Electron microscopic analysis and demonstration of a postsynaptic density as well as synaptic vesicles in the presynaptic axonal compartment can provide even stronger evidence. Morphology alone does not prove the existence of functional synapses, but unambiguous evidence of synaptic transmission can be obtained using electrophysiological tools (Regehr and Stevens, 2001). A prerequisite for synaptic transmission is the expression of certain ionotropic neurotransmitter receptors, which can be tested by exposing the cells to specific receptor agonists such as glutamate or GABA and determining the current responses in the presence and absence of channel blockers to show specificity. Obviously, the expression of neurotransmitter receptors does not prove synaptic function. The presence of functional synapses can be demonstrated by the recording of typical spontaneous postsynaptic currents (PSCs), which display as distinct waveforms (Figure 4D,E) with sharp rise and slow decay phases caused by the dynamics of presynaptic vesicle exocytosis, and biophysical properties of postsynaptic receptors. PSCs can be recorded spontaneously or evoked by stimulation of presynaptic terminals (e.g. by extracellular stimulation). Application of specific neurotransmitter receptor blockers demonstrates specificity of the responses and distinguish inhibitory (IPSC) from excitatory postsynaptic activity (EPSC). Sometimes, noise caused by fluctuation of membrane channels during the recording can cause membrane potential deflections that appear to be bewildering synaptic currents (Figure 4D1). Therefore, not every deviation from the baseline is mediated by synaptic transmission and cautious interpretation of the recorded traces is essential. The evaluation of presynaptic competence is in our view the most rigorous criteria of neuronal function but also the most difficult test. This requires either the culture of pure iN cells in a sufficient density or paired recordings. Finally, mature synapses also often show simple short-term plasticity such as depression or facilitation.

In summary, we propose distinguishing fully and partially-reprogrammed iN cells based on a specific combination of molecular and functional characteristics. We suggest that the critical feature of fully reprogrammed iN cells should be the demonstration of synaptic competence as determined by the presence of spontaneous and evoked postsynaptic currents in mixed or pure neuronal cultures. iN cells can be assessed either in vitro or after transplantation into rodent brains, which may provide a better environment for maturation.

Outlook and concluding remarks

Although still at a nascent stage, the field of direct somatic lineage reprogramming has already attracted a lot of attention. From a biological standpoint, it may become a new method in the developmental and molecular biology toolbox. It offers a new way to interrogate transcription factor function independent of the physiological environment, and to study the complex interplay between sequence-specific transcriptional regulators and various repressive and active chromatin states, as well as the recruitment of their underlying chromatin-modifying enzymes. Moreover, the generation of iN cells represents a novel way to study the mechanisms of cell fate decisions of neural development and postmitotic neuronal maturation. In addition, the use of human iN cells provides an avenue for studying human developmental processes in live cultures, which may enable the discovery of species-specific differences relative to the much better studied model organisms.

From a medical point of view, direct lineage reprogramming provides an alternative potentially complementary tool to many of the proposed applications of iPS cell technology for both disease modeling and development of cell-based therapies. Recently, several elegant reports of assessing disease-related phenotypes in iPS cell-derived neurons have provided an important proof-of-principle that at least some cellular aspects of complex brain diseases can be recapitulated with patient-derived cells in vitro (Marchetto et al., 2010, Brennand et al., 2011, Nguyen et al., 2011). Both iPS and iN cell approaches are complicated by the heterogeneity with respect to maturation and presumably subtype specification. Especially iPS cells have shown a substantial line-to-line variability with regards to differentiation potential (Hu et al., 2010). Future studies will show whether directly generated iN cells can provide a better representation of the cellular variability, which might in turn simplify the discovery and analysis of disease-associated phenotypes. Moreover, the generation of iN cells from a large cohort of patients appears quite feasible whereas the generation and neuronal differentiation of iPS cells would be a very cumbersome and slow process.

For potential use in regenerative medicine both iPS and iN cell approaches would provide autologous neuronal donor cells for transplantation. Expandability is obviously a major advantage of iPS cells over postmitotic iN cells and may very well be a limiting factor. However, the postmitotic state of iN cells would have the advantage of a much lower risk of cancer and teratoma formation. Integration-free iN cells would be preferable for clinical use. Along those lines will it be exciting to see whether small molecules can be found to replace some or all transcription factors, similar to the recent successes for iPS cells. Finally, future studies will need to improve iN cell generation from adult human fibroblast since the current low efficiencies represent another hurdle for any of these translational applications.

References

- Ambasudhan R, Talantova M, Coleman R, Yuan X, Zhu S, Lipton SA, Ding S. Direct Reprogramming of Adult Human Fibroblasts to Functional Neurons under Defined Conditions. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anokye-Danso F, Trivedi CM, Juhr D, Gupta M, Cui Z, Tian Y, Zhang Y, Yang W, Gruber PJ, Epstein JA, et al. Highly efficient miRNA-mediated reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker GA. Trophic interactions between astroglial cells and hippocampal neurons in culture. Science. 1980;209(4458):809–810. doi: 10.1126/science.7403847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti L, Olive S, Poulain D, Theodosis D. Mapping of the distribution of polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule throughout the central nervous system of the adult rat: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroscience. 1992;49:419–436. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90107-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennand KJ, Simone A, Jou J, Gelboin-Burkhart C, Tran N, Sangar S, Li Y, Mu Y, Chen G, Yu D, et al. Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;473:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiazzo M, Dell'Anno MT, Dvoretskova E, Lazarevic D, Taverna S, Leo D, Sotnikova TD, Menegon A, Roncaglia P, Colciago G, et al. Direct generation of functional dopaminergic neurons from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nature. 2011;476:224–227. doi: 10.1038/nature10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efe JA, Hilcove S, Kim J, Zhou H, Ouyang K, Wang G, Chen J, Ding S. Conversion of mouse fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes using a direct reprogramming strategy. Nature Cell Biology. 2011;13:215–222. doi: 10.1038/ncb2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu C, Barres BA. Regulation of synaptic connectivity by glia. Nature. 2010;468:223–231. doi: 10.1038/nature09612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspard N, Bouschet T, Hourez R, Dimidschstein J, Naeije G, van den Ameele J, Espuny-Camacho I, Herpoel A, Passante L, Schiffmann SN, et al. An intrinsic mechanism of corticogenesis from embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2008;455:351–357. doi: 10.1038/nature07287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB. From nuclear transfer to nuclear reprogramming: the reversal of cell differentiation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.090805.140144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O. Regulation of terminal differentiation programs in the Nervous System. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:681–696. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Kanagawa O, Nakagawa M, Okita K, Yamanaka S. Suppression of induced pluripotent stem cell generation by the p53-p21 pathway. Nature. 2009;460:1132–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature08235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BY, Weick JP, Yu J, Ma LX, Zhang XQ, Thomson JA, Zhang SC. Neural differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells follows developmental principles but with variable potency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(9):4335–4340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910012107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, He Z, Ji S, Sun H, Xiang D, Liu C, Hu Y, Wang X, Hui L. Induction of functional hepatocyte-like cells from mouse fibroblasts by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:386–389. doi: 10.1038/nature10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, Vedantham V, Hayashi Y, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenisch R, Young R. Stem cells, the molecular circuitry of pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming. Cell. 2008;132:567–582. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MA, Weick JP, Pearce RA, Zhang SC. Functional neural development from human embryonic stem cells: accelerated synaptic activity via astrocyte coculture. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3069–3077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4562-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura T, Suzuki J, Wang YV, Menendez S, Morera LB, Raya A, Wahl GM, Belmonte JC. Linking the p53 tumour suppressor pathway to somatic cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460:1140–1144. doi: 10.1038/nature08311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Efe JA, Zhu S, Talantova M, Yuan X, Wang S, Lipton SA, Zhang K, Ding S. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neural progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7838–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Su SC, Wang H, Cheng AW, Cassady JP, Lodato MA, Lengner CJ, Chung CY, Dawlaty MM, Tsai LH, et al. Functional Integration of Dopaminergic Neurons Directly Converted from Mouse Fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester J, Siegelbaum SA. Propagated signaling: the action potential. Principles of Neural Science, ed. 4:159. [Google Scholar]

- Kriks S, Kriks S, Shim JW, Piao J, Ganat YM, Wakeman DR, Xie Z, Carrillo-Reid L, Auyeung G, Antonacci C, et al. Dopamine neurons derived from human ES cells efficiently engraft in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2011 Nov 6; doi: 10.1038/nature10648. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Lee B, Ruiz EC, Pfaff SL. Olig2 and Ngn2 function in opposition to modulate gene expression in motor neuron progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2005;19:282–294. doi: 10.1101/gad.1257105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Collado M, Villasante A, Strati K, Ortega S, Canamero M, Blasco MA, Serrano M. The Ink4/Arf locus is a barrier for iPS cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460:1136–1139. doi: 10.1038/nature08290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockery SR, Goodman MB, Faumont S. First report of action potentials in a C. elegans neuron is premature. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12:365–366. doi: 10.1038/nn0409-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QR, Sun T, Zhu Z, Ma N, Garcia M, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. Common developmental requirement for Olig function indicates a motor neuron/oligodendrocyte connection. Cell. 2002;109:75–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetto MC, Carromeu C, Acab A, Yu D, Yeo GW, Mu Y, Chen G, Gage FH, Muotri AR. A model for neural development and treatment of Rett syndrome using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion RM, Strati K, Li H, Murga M, Blanco R, Ortega S, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Serrano M, Blasco MA. A p53-mediated DNA damage response limits reprogramming to ensure iPS cell genomic integrity. Nature. 2009;460:1149–1153. doi: 10.1038/nature08287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marro S, Pang ZP, Yang N, Tsai MC, Qu K, Chang HY, Sudhof TC, Wernig M. Direct lineage conversion of terminally differentiated hepatocytes to functional neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massari ME, Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:429–440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi N, Ishii H, Nagano H, Haraguchi N, Dewi DL, Kano Y, Nishikawa S, Tanemura M, Mimori K, Tanaka F, et al. Reprogramming of mouse and human cells to pluripotency using mature microRNAs. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi R, Sugimori M, Takebayashi H, Kosako H, Nagao M, Yoshida S, Nabeshima Y, Shimamura K, Nakafuku M. Combinatorial roles of olig2 and neurogenin2 in the coordinated induction of pan-neuronal and subtype-specific properties of motoneurons. Neuron. 2001;31:757–771. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development. 1992;116:201–211. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HN, Byers B, Cord B, Shcheglovitov A, Byrne J, Gujar P, Kee K, Schule B, Dolmetsch RE, Langston W, et al. LRRK2 mutant iPSC-derived DA neurons demonstrate increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitch BG, Chen AI, Jessell TM. Coordinate regulation of motor neuron subtype identity and pan-neuronal properties by the bHLH repressor Olig2. Neuron. 2001;31:773–789. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang ZP, Yang N, Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Fuentes DR, Yang TQ, Citri A, Sebastiano V, Marro S, Sudhof TC, et al. Induction of human neuronal cells by defined transcription factors. Nature. 2011;476:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HC, Mehta A, Richardson JS, Appel B. olig2 is required for zebrafish primary motor neuron and oligodendrocyte development. Dev Biol. 2002;248:356–368. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfisterer U, Kirkeby A, Torper O, Wood J, Nelander J, Dufour A, Bjorklund A, Lindvall O, Jakobsson J, Parmar M. Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to dopaminergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10343–10348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105135108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang L, Fujita R, Yamashita T, Angulo S, Rhinn H, Rhee D, Doege C, Chau L, Aubry L, Vanti WB, et al. Directed conversion of Alzheimer's disease patient skin fibroblasts into functional neurons. Cell. 2011;146:359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Regehr WG, Stevens C. Physiology of synaptic transmission and shortterm plasticity. Synapses. 2001;135:Äì175. [Google Scholar]

- Roy NS, Cleren C, Singh SK, Yang L, Beal MF, Goldman SA. Functional engraftment of human ES cell-derived dopaminergic neurons enriched by coculture with telomerase-immortalized midbrain astrocytes. Nat Med. 2006;12:1259–1268. doi: 10.1038/nm1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:390–393. doi: 10.1038/nature10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MA, Kaech S, Jareb M, Burack MA, Vogt L, Sonderegger P, Banker G. Sorting and directed transport of membrane proteins during development of hippocampal neurons in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7051–7057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111146198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son EY, Ichida JK, Wainger BJ, Toma JS, Rafuse VF, Woolf CJ, Eggan K. Conversion of mouse and human fibroblasts into functional spinal motor neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song HJ, Stevens CF, Gage FH. Neural stem cells from adult hippocampus develop essential properties of functional CNS neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(5):438–445. doi: 10.1038/nn844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo E, Rampalli S, Risueno RM, Schnerch A, Mitchell R, Fiebig-Comyn A, Levadoux-Martin M, Bhatia M. Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to multilineage blood progenitors. Nature. 2010;468:521–526. doi: 10.1038/nature09591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi H, Nabeshima Y, Yoshida S, Chisaka O, Ikenaka K. The basic helix-loop-helix factor olig2 is essential for the development of motoneuron and oligodendrocyte lineages. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropepe V, Hitoshi S, Sirard C, Mak TW, Rossant J, van der Kooy D. Direct neural fate specification from embryonic stem cells: a primitive mammalian neural stem cell stage acquired through a default mechanism. Neuron. 2001;30:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utikal J, Polo JM, Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Kulalert W, Walsh RM, Khalil A, Rheinwald JG, Hochedlinger K. Immortalization eliminates a roadblock during cellular reprogramming into iPS cells. Nature. 2009;460:1145–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature08285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicario-Abejón C, Collin C, Tsoulfas P, McKay RD. Hippocampal stem cells differentiate into excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(2):677–688. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Sudhof TC, Wernig M. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010;463:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nature08797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierbuchen T, Wernig M. Direct lineage conversions: unnatural but useful? Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:892–907. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub H, Tapscott SJ, Davis RL, Thayer MJ, Adam MA, Lassar AB, Miller AD. Activation of muscle-specific genes in pigment, nerve, fat, liver, and fibroblast cell lines by forced expression of MyoD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5434–5438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernig M, Benninger F, Schmandt T, Rade M, Tucker KL, Büssow H, Beck H, Brüstle O. Functional integration of embryonic stem cell-derived neurons in vivo. J Neurosci.2. 2004;24(22):5258–5268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0428-04.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Xu J, Pang ZP, Ge W, Kim KJ, Blanchi B, Chen C, Sudhof TC, Sun YE. Integrative genomic and functional analyses reveal neuronal subtype differentiation bias in human embryonic stem cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13821–13826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706199104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka S, Blau HM. Nuclear reprogramming to a pluripotent state by three approaches. Nature. 2010;465:704–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Zhang ZJ, Oldenburg M, Ayala M, Zhang SC. Human embryonic stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons reverse functional deficit in parkinsonian rats. Stem Cells. 2008;26:55–63. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo AS, Staahl BT, Chen L, Crabtree GR. MicroRNA-mediated switching of chromatin-remodelling complexes in neural development. Nature. 2009;460:642–646. doi: 10.1038/nature08139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo AS, Sun AX, Li L, Shcheglovitov A, Portmann T, Li Y, Lee-Messer C, Dolmetsch RE, Tsien RW, Crabtree GR. MicroRNA-mediated conversion of human fibroblasts to neurons. Nature. 2011;476:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Choi G, Anderson DJ. The bHLH transcription factor Olig2 promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation in collaboration with Nkx2.2. Neuron. 2001;31:791–807. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00414-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]