Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the third most common hematologic malignancy in Korea. Historically, the incidence of MM in Korea has been lower than that in Western populations, although there is growing evidence that the incidence of MM in Asian populations, including Korea, is increasing rapidly. Despite advances in the management of MM, patients will ultimately relapse or become refractory to their current treatment, and alternative therapeutic options are required in the relapsed/refractory setting. In Korea, although lenalidomide/dexamethasone is indicated for the treatment of relapsed or refractory MM (RRMM) in patients who have received at least one prior therapy, lenalidomide is reimbursable specifically only in patients with RRMM who have failed bortezomib-based treatment. Based on evidence from pivotal multinational clinical trials as well as recent studies in Asia, including Korea, lenalidomide/dexamethasone is an effective treatment option for patients with RRMM, regardless of age or disease status. Adverse events associated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone, including hematologic toxicity, venous thromboembolism, fatigue, rash, infection, and muscle cramps, are largely predictable and preventable/manageable with appropriate patient monitoring and/or the use of standard supportive medication and dose adjustment/interruption. Lenalidomide/dexamethasone provides an optimal response when used at first relapse, and treatment should be continued long term until disease progression. With appropriate modification of the lenalidomide starting dose, lenalidomide/dexamethasone is effective in patients with renal impairment and/or cytopenia. This review presents updated evidence from the published clinical literature and provides recommendations from an expert panel of Korean physicians regarding the use of lenalidomide/dexamethasone in patients with RRMM.

Keywords: Guideline, Korea, Lenalidomide, Multiple myeloma, Refractory, Relapsed

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM), a plasma cell neoplasm, accounts for approximately 10% of all hematologic malignancies [1, 2, 3]. In Western populations, the annual incidence of MM is estimated to be about 3-5/100,000 patients [1]. Historically, Asian populations have exhibited a lower incidence of MM (0.5-3/100,000 patients) [4]. However, there is growing evidence that the incidence of MM in Asian populations is increasing rapidly [5], with the incidence of MM in Korea doubling between 2000 and 2010 [4]. A recent study from the Asian Myeloma Network reported that the median age of MM patients in Asia (N=3,405) was 62 years, and there was a higher prevalence in men than in women [5].

Irrespective of sex, MM currently ranks as the third most common hematologic malignancy in Korea, after non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [2]. In fact, the incidence of MM has surpassed that of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and is approaching the incidence of AML [2]. Overall, the incidence of hematologic malignancies, including MM, in Korea is similar to that reported in China and Japan [2].

The clinical features and survival outcomes of 3,209 patients with MM in Korea were reported in an analysis of web-based data from the Korean Myeloma Registry [6]. The study demonstrated associations between survival outcomes and treatment modalities, as well as between outcomes and baseline disease characteristics. More recently, epidemiologic data from 3,405 symptomatic MM patients in 7 Asian countries have shown that there are no unique clinical characteristics of MM that are specific to Asian patients compared with Western patients with MM [5].

Although there have been advances in the management of MM, allowing patients to achieve improvements in complete response rates and sustained response durations, MM patients will nonetheless ultimately relapse or become refractory to their current treatment [3, 7, 8, 9]. Alternative therapeutic options are subsequently required in the relapsed or refractory setting.

The Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) approved the use of lenalidomide, a thalidomide derivative, in combination with dexamethasone in 2009 for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory MM (RRMM) who have received at least 1 prior therapy [10].

Lenalidomide has anti-angiogenic, anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, and immunomodulatory effects [11]. Although the precise cellular targets and molecular processes responsible for the actions of immunomodulatory drugs, including lenalidomide, in MM have not been elucidated fully, a recent landmark study identified cereblon (CRBN: cerebral protein with Lon protease) as a primary target of thalidomide teratogenicity [12]. Subsequently, the anti-myeloma activity of both thalidomide and lenalidomide has been shown to be dependent on the presence of CRBN [13, 14].

The combination of lenalidomide and dexamethasone has demonstrated efficacy and safety in patients with RRMM in 2 large, well-designed pivotal clinical trials conducted, respectively, in North America (MM-009) [15] and Europe, Israel, and Australia (MM-010) [16]. Compared with placebo/dexamethasone, lenalidomide/dexamethasone resulted in significant improvements in overall response rate (ORR), time-to-progression (TTP), and overall survival (OS). The most common adverse events included hematologic toxicity and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Several recent clinical studies conducted in Korea [17], China (MM-021) [18], and Japan [19] have also demonstrated the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide/dexamethasone in Asian patients with RRMM. However, despite the availability of clinical practice guidelines for the use of lenalidomide in the treatment of RRMM in Caucasian populations [20, 21, 22, 23, 24], currently, no treatment guidelines have been tailored for the Korean population.

The objective of this article is to present an updated review of the current literature on the use of lenalidomide in patients with RRMM and to provide specific expert recommendations from the Korean perspective. These guidelines are based on published literature and the clinical experience of an expert panel of Korean clinicians.

INDICATION AND TIMING

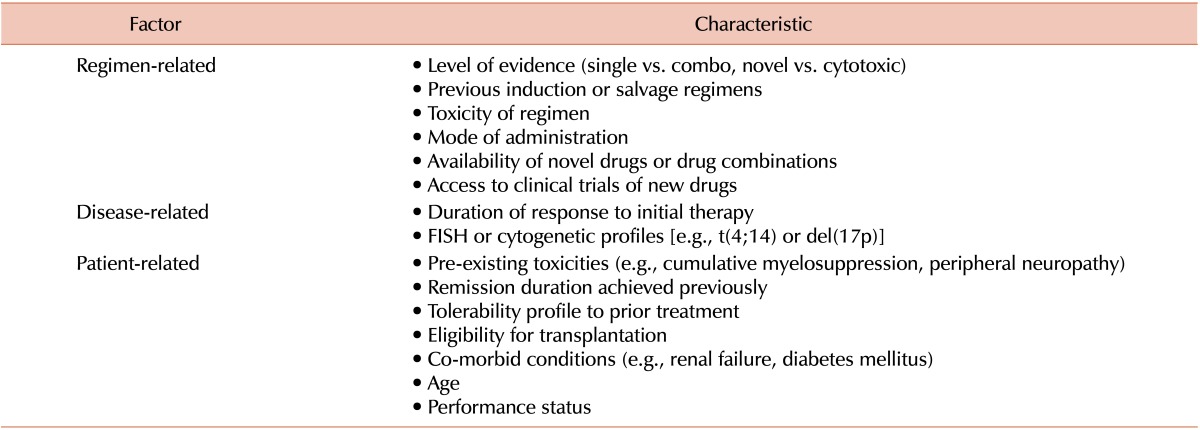

A number of factors relating to disease and patient characteristics, as well as treatment regimen, must be considered when selecting an appropriate treatment for patients with RRMM (Table 1). For example, the duration of response can affect outcomes; patients with a duration of remission <6 months have an inferior response duration compared with patients who have a remission duration >12 months [25]. In addition, different management strategies may be needed for patients with rapid disease progression or aggressive relapse compared with patients exhibiting indolent, slowly progressive disease relapse [25].

Table 1. Factors for consideration before selecting the appropriate treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.

Abbreviation: FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization.

In Korea, lenalidomide, in combination with dexamethasone, is indicated (under a special risk management program) for the treatment of MM in patients who have undergone at least 1 prior therapy [10]. However, there is currently a gap between the approved lenalidomide indication and reimbursement guidelines, with lenalidomide being reimbursed specifically only in patients with MM who have failed bortezomib-based treatment.

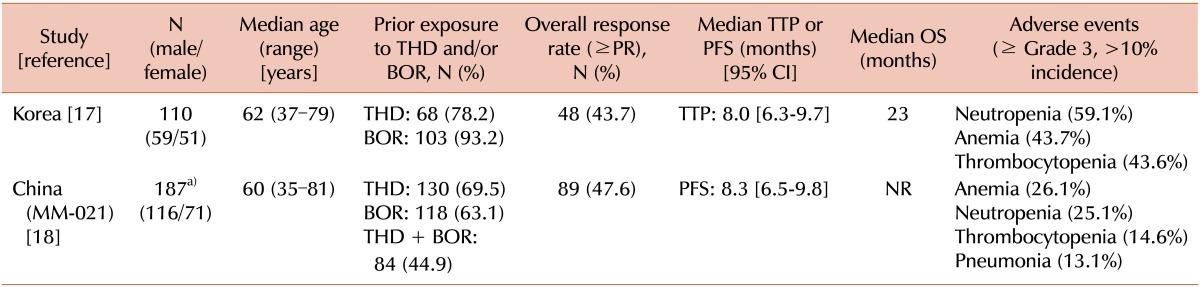

The rationale for the indication of lenalidomide/dexamethasone in the treatment of RRMM is based on data from 2 pivotal clinical studies, MM-009 and MM-010 [15, 16]. In both studies, the median OS was significantly longer with lenalidomide/dexamethasone than with dexamethasone alone (29.6 months or not reached vs. 20.2-20.6 months, respectively; P<0.001). ORRs (60-61% vs. 20-24%, respectively; P<0.001) and the median TTP (11.1-11.3 months vs. 4.7 months, respectively; P<0.001) were also improved significantly with lenalidomide/dexamethasone compared with dexamethasone alone [15, 16]. Long-term follow-up (median 48 months) from the 2 studies demonstrated that the benefit of lenalidomide/dexamethasone compared with dexamethasone alone remained significant [26]. Similar response rates and survival benefits have been reported in recently published clinical studies conducted in Korea [17] and China (MM-021) [18], each including more than 100 RRMM patients treated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of key clinical data from 2 large (>100 patients) multicenter, noncomparative studies (Korea and China) in Asian patients receiving lenalidomide/dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma [17, 18].

a)Primary efficacy population (safety population: N=199).

Abbreviations: BOR, bortezomib; CI, confidence interval; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; THD, thalidomide; TTP, time to progression.

Hematologic toxicities (particularly neutropenia) and thromboembolic events are the most clinically important adverse events associated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone treatment [27]. Prevention (see 'Prophylactic management of adverse events') and treatment (see 'Treatment of adverse events') strategies for adverse events are discussed in detail in this review.

A subgroup analysis of the 2 pivotal clinical trials mentioned above revealed that lenalidomide/dexamethasone is both effective and tolerable for second-line MM therapy, with data indicating that the greatest benefit occurs with earlier use of the combination [28]. Patients who had undergone 1 prior therapy had significantly prolonged median TTP (17.1 months vs. 10.6 months; P=0.026) and progression-free survival (PFS; 14.1 months vs. 9.5 months, P=0.047) compared with patients who had previously received more than 1 prior therapy. ORRs were also significantly higher in patients experiencing their first relapse (66.9% vs. 56.8%, P=0.06), as was the complete plus very good partial response rate (39.8% vs. 27.7%, P=0.025). Importantly, OS was significantly prolonged for patients treated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone who had only received 1 prior therapy, compared with patients treated in later salvage lines (median of 42.0 months vs. 35.8 months, P=0.041) and, despite longer treatment, there were no differences in toxicity, dose reductions, or discontinuations [28]. Similar outcomes were also reported in study MM-021 conducted in patients with RRMM in China, demonstrating that treatment outcomes may be better if lenalidomide/dexamethasone is initiated early rather than after several previous therapies [18].

Furthermore, despite potential concerns of resistance in patients previously exposed to thalidomide, a subgroup analysis of MM-009 and MM-010 showed that lenalidomide/dexamethasone was superior to placebo plus dexamethasone, regardless of prior thalidomide exposure [29]. In a recent "real world" study in 212 patients with RRMM, the quality of response to lenalidomide/dexamethasone was found to be independent of previous lines of therapy or prior exposure to either thalidomide or bortezomib [30].

In a separate subanalysis of MM-009 and MM-010, continuation of lenalidomide treatment until disease progression, after achievement of at least a partial response, was associated with a significant survival advantage (hazard ratio [HR], 0.137; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.045-0.417; P=0.0005) when controlling for patient characteristics (number of prior MM therapies, β2-microglobulin levels, and Durie-Salmon disease stage) [31]. Each additional lenalidomide cycle was also associated with longer survival (HR, 0.921; 95% CI, 0.886-0.957; P<0.0001) [31]. Furthermore, continuing treatment with lenalidomide/dexamethasone to achieve best response, in the absence of disease progression and toxicity, provided deeper remissions and greater clinical benefit over time [32].

A number of recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of long-term treatment with lenalidomide/dexamethasone in patients with RRMM [33, 34]. A retrospective analysis from a single-center German study in 67 non-selected patients with RRMM compared Kaplan-Meier survival estimates between the total population, patients receiving lenalidomide for >12 months, and patients discontinuing therapy after <12 months [33]. The median OS times in the total patient population, in patients treated for >12 months, and in those who stopped lenalidomide after <12 months for reasons other than disease progression, were 33.2, 42.9, and 20.2 months, respectively (P=0.027) [33]. Thus, the analysis showed that the OS of patients receiving lenalidomide for >12 months was superior when compared with that of patients who discontinued lenalidomide after <12 months for reasons other than disease progression. These data confirm the potential use of lenalidomide as a continuous long-term treatment strategy [33].

In a study conducted by the French Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM), 50 patients with RRMM received lenalidomide/dexamethasone for ≥2 years (median duration 3 years [range, 2-7 years]) [34]. Response rates of at least partial response and very good partial response were achieved in 96% and 74% of patients in the overall cohort, respectively. At 37 months' follow-up, the percentages of patients free from progression were 78.3% and 91.3% (odds ratio [OR] 11.052 [95% CI: 0.94-129.91]; P=0.025) for patients exposed to lenalidomide for 2 to <3 years and ≥3 years, respectively. There were no notable changes in the incidence of adverse events in patients who received lenalidomide/dexamethasone for >3 years [34].

▪ Expert recommendations

• Based on the approved indication, lenalidomide (in combination with dexamethasone) is recommended for the treatment of MM in patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy. However, the expert panel highlights that lenalidomide is currently reimbursed in Korea only for patients after bortezomib treatment failure.

• Optimally, based on clinical evidence, lenalidomide should be administered as early as possible after first relapse and continued until disease progression.

DOSE AND SCHEDULE

Based on data from the 2 pivotal phase III trials, MM-009 and MM-010, the standard recommended dosing schedule for oral lenalidomide is 25 mg/day on days 1-21 of each 28-day cycle [10]. The starting dose of lenalidomide requires adjustment according to renal function or cytopenia (see 'Renal insufficiency' and 'Cytopenia'), but lenalidomide dose adjustment is not required on the basis of patient age or disease stage.

For patients with aggressive disease, the recommended starting dose of dexamethasone is 40 mg/day on days 1-4, 9-12, and 17-20 of each 28-day cycle for the first 4 cycles, then 40 mg/day for 1-4 days. An alternative, slightly lower, dexamethasone dosing schedule is 40 mg/day on days 1-4 and 15-20 of each 28-day cycle for the first 4 cycles, then 40 mg/day for 1-4 days. The dexamethasone dose can be reduced according to patient age (see 'Elderly patients').

However, as discussed in more detail later, it is important to note that, in a retrospective analysis of Korean patients with RRMM who received lenalidomide/dexamethasone, it was found that the majority of physicians favored the use of a low-dose dexamethasone schedule (160 mg per cycle): oral dexamethasone 40 mg/day on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 of each 28-day cycle [17]. According to our survey regarding the dose and schedule of dexamethasone, the regimen of 40 mg/day once a week for 4 weeks was the most preferred schedule.

Patients with normal renal function and complete blood counts (CBCs) at baseline may be monitored every 2 weeks for the first 2-3 cycles of lenalidomide/dexamethasone. Patients with neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, or renal impairment may require more intensive monitoring. For patients who have experienced no complications after 2-3 cycles, monitoring every 4 weeks should be sufficient [21].

Elderly patients

MM is commonly observed in elderly individuals [35]. Based on the 2011 cohort of Korean patients, the median age at MM diagnosis is 67 years [36] and the increasing age of the overall Korean population is postulated to be among the reasons for the rise in the incidence of MM in recent years [5].

In a pooled, retrospective subanalysis of MM-009 and MM-010, lenalidomide/dexamethasone improved the ORR and led to prolonged PFS, TTP, and OS compared with placebo plus dexamethasone, irrespective of the age of patients [37]. Three age-specific subgroups were defined: patients aged <65 years (N=390), patients aged 65-74 years (N=232), and those aged ≥75 years (N=82). The ORR with lenalidomide/dexamethasone was similar in all 3 groups and consistently higher than that achieved with dexamethasone alone (P<0.0001 for all age groups). In each age group, the median PFS and the median TTP were also consistently higher with lenalidomide/dexamethasone than with dexamethasone alone (P<0.001 for all age groups), indicating that the benefit of lenalidomide/dexamethasone over dexamethasone alone is independent of patient age. Increasing age, however, was associated with an increased incidence of anemia, febrile neutropenia, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), neuropathy, and gastrointestinal disorders. Although dose modification was more common in patients aged ≥75 years, there was no indication that dose reduction limited the benefits of lenalidomide therapy [37]. Overall, these findings from the age-specific subanalysis were consistent with those from the overall MM-009 and MM-010 study populations. Indeed, international guidelines state that lenalidomide/dexamethasone is an appropriate treatment option for patients with RRMM, regardless of age [21].

In current daily clinical practice, a reduced dose of lenalidomide is often used for RRMM. According to a recent study from the Greek Myeloma Study Group, the initial dose of lenalidomide was higher in patients aged <65 years compared with that in older patients; the recommended starting dose of lenalidomide (25 mg) was administered in 84.5% of patients aged <65 years compared with 64.5% of older patients (P=0.02) [30].

▪ Expert recommendations

• In the absence of other factors (e.g., renal impairment, cytopenia), lenalidomide can be administered, without dose reduction, regardless of age.

Dexamethasone: dose and schedule

Standard, high-dose dexamethasone should be considered in certain cases, such as for patients with spinal cord compression, hypercalcemia, pain, or renal failure [21, 35].

The use of a lower total dose of dexamethasone (compared with standard, high-dose dexamethasone) has been associated with a reduced incidence of serious adverse events (including thromboembolic complications) and early deaths, particularly within the first 4 months of therapy, when administered to patients with newly diagnosed MM [38].

As noted earlier, although starting doses of lenalidomide and dexamethasone in the retrospective analysis of 110 patients with RRMM in Korea were based on MFDS recommendations, the majority of patients started on lenalidomide 25 mg on days 1-21 (84.5%) and dexamethasone 160 mg per cycle (61.8%) [17]. The lower dexamethasone dose and schedule (40 mg/day on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 of a 28-day cycle) were based on data from the US Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) E4A03 trial conducted in 445 patients with newly diagnosed MM [38]. In this study, lenalidomide/low-dose dexamethasone was associated with significantly better short-term OS (96% [95% CI, 94-99] vs. 87% [95% CI, 82-92], P=0.0002, at 1 year) and lower toxicity (grade 3 or worse: 35% vs. 52% of patients, P=0.0001) than lenalidomide/high-dose dexamethasone [38].

In the MM-009 and MM-010 studies, the dexamethasone dose was modified (due to toxic effects), at the investigator's discretion, to 1 of the following levels: 40 mg/day for 4 days every 2 weeks (dose level, -1), 40 mg/day for 4 days every 4 weeks (dose level, -2), or 20 mg/day for 4 days every 4 weeks (dose level, -3) [15, 16].

Although few prospective, well-controlled studies have analyzed the effects of low-dose dexamethasone in combination with lenalidomide in the RRMM setting, the use of low-dose dexamethasone with lenalidomide is recommended because it offers improved tolerability with no loss of efficacy compared with the standard regimen [21]. In addition, the following age-related dexamethasone modifications have been recommended by an international consensus panel [21]: age <65 years: 40 mg/day on days 1-4 and 15-18 of each 28-day cycle for the first 4 cycles, then 40 mg/day weekly (days 1, 8, 15, 22 of each 28-day cycle); age 65-75 years: 40 mg/day weekly; age >75 years: 20 mg/day weekly.

▪ Expert recommendations

• In combination with lenalidomide, a low-dose dexamethasone schedule is recommended due to improved tolerability compared with standard high-dose dexamethasone.

• High-dose dexamethasone may be considered in certain cases, such as for patients with spinal cord compression, hypercalcemia, pain, or renal failure.

• Age-adjusted dexamethasone dose reductions are recommended.

Renal insufficiency

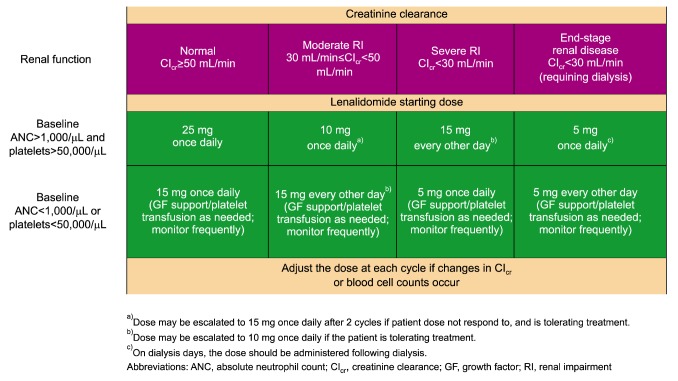

Lenalidomide undergoes minimal metabolism in humans and is eliminated predominantly via urinary excretion in an unchanged form [39]. Consequently, lenalidomide dosing must be adjusted based on creatinine clearance (ClCr; assessed using the Cockcroft-Gault or MDRD [Modification of Diet in Renal Disease] equations) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. International consensus recommendations for identifying the optimal lenalidomide starting dose (when used in combination with dexamethasone) in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, according to baseline renal function and cytopenia [21]. Each lenalidomide cycle is 21 days out of 28 days. Reproduced with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Leukemia, copyright 2011.

In a pooled retrospective analysis of the MM-009 and MM-010 trials, lenalidomide/dexamethasone treatment was effective in patients with RRMM, irrespective of the degree of baseline renal impairment [40]. There were no significant differences in clinical response between patients with mild or no renal impairment (ORR 64%) and patients with moderate (ORR 56%) or severe (ORR 50%) renal impairment. However, at a median follow-up of 31.3 months, median OS was significantly longer in patients with mild or no renal impairment than in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment (38.9 months vs. 29.0 months and 18.4 months, respectively; both P=0.006). Importantly, 70% and 86% of patients with moderate (ClCr ≤30 to <60 mL/min; N=80) or severe (ClCr <30 mL/min; N=14) renal impairment, respectively, experienced improved renal function during treatment with lenalidomide/dexamethasone. It is also notable, however, that significantly more patients (P<0.05) with moderate (40%) or severe (38%) renal impairment than with mild/no renal impairment (22%) required a dose reduction or interruption because of an adverse event [40].

Overall, these data indicate that, with appropriate modification of lenalidomide dosing according to renal function (Fig. 1), lenalidomide/dexamethasone can be administered to RRMM patients with renal impairment (who may not have other treatment options) without excessive toxicity [41]. Furthermore, it has been shown that lenalidomide/dexamethasone may improve renal function in a substantial proportion of RRMM patients with renal impairment [41, 42].

Recent data from European clinical studies have reinforced the fact that lenalidomide-based treatment is highly effective and represents an attractive treatment option in patients with MM with impaired renal function [43, 44]. In a retrospective, multicenter analysis of 26 patients with RRMM and impaired renal function (ClCr <60 mL/min), the ORR (at least a partial response) was 84% and the rate of renal response (at least a minor renal response) was 42% (6 patients achieved a complete renal response) [43]. Lenalidomide/dexamethasone has also shown efficacy with acceptable toxicity in 20 elderly patients (median [range] age 76.5 [68-85] years) with relapsed (N=7) or refractory (N=13) MM and moderate to severe renal failure (ClCr <50 mL/min) [44]. In both studies, the lenalidomide dose was adjusted according to the degree of renal impairment.

▪ Expert recommendations

• With appropriate dose modification, lenalidomide can be administered to patients with varying degrees of renal impairment.

• In patients demonstrating improved renal function, lenalidomide dosing can be increased with caution.

Cytopenia

Lenalidomide can cause significant neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Preventive measures are often required in patients at high risk of developing neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, and supportive treatment (see 'Hematologic toxicities') is necessary in patients who develop cytopenia during therapy [45]. Lenalidomide should be used with caution in patients with baseline thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50,000/µL or <30,000/µL in patients with heavy marrow infiltration with myeloma) or neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] <1,000/µL) [23]. While there is insufficient evidence for a standard approach for the management of cytopenia, current international expert opinion indicates that lenalidomide can be initiated, with caution, in patients with cytopenia, provided that frequent monitoring of CBCs and appropriate management strategies, including growth factor support (granulocyte-colony stimulating factor [G-CSF] for neutropenia) and/or platelet transfusions, and lenalidomide dose modification, are implemented [10, 21, 23, 24]. If changes in the CBC occur, the lenalidomide dose should be adjusted by 1 dose step in each cycle (e.g., from 25 mg/day to 15 mg/day per cycle) (Fig. 1) [21].

▪ Expert recommendations

• If frequent monitoring of CBCs and appropriate management strategies are implemented, including growth factor support (G-CSF for neutropenia) and/or platelet transfusions and lenalidomide dose interruption/reduction, lenalidomide can be initiated, with caution, in patients with cytopenia.

• Patients with existing cytopenia require more frequent monitoring.

PROPHYLACTIC MANAGEMENT OF ADVERSE EVENTS

Venous thromboembolism

Data from the 2 pivotal phase III multinational registration studies (MM-009 and MM-010) indicated that the incidence of VTE with lenalidomide/dexamethasone treatment in patients with RRMM was 8.8%-14.7% [15, 16].

The risk of VTE is associated with the type of regimen used: lenalidomide/high-dose dexamethasone (18%) > lenalidomide/low-dose dexamethasone (4%)≈dexamethasone (3.4%-4.7%)≈lenalidomide (<4%) [46].

Without prophylaxis, the incidence of VTE associated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone was similar in patients with newly diagnosed MM and RRMM (0.8% and 0.7%, respectively) based on a systematic review and meta-analysis [47]. Similarly, the rates of VTE in patients undergoing thromboprophylaxis with aspirin were 0.9% (95% CI, 0.5-1.5) and 0.6% (95% CI, 0.01-2.1), respectively [47]. The incidence of VTE is highest in the first few months after initiation of lenalidomide/dexamethasone, followed by a reduced incidence [48].

Based on Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) data, the incidence of VTE in Korea in general is approximately one-tenth of that in Western populations [49]. However, the risk of advanced cancer-associated VTE in Korea has been shown to be similar to that in Western populations [50, 51, 52, 53].

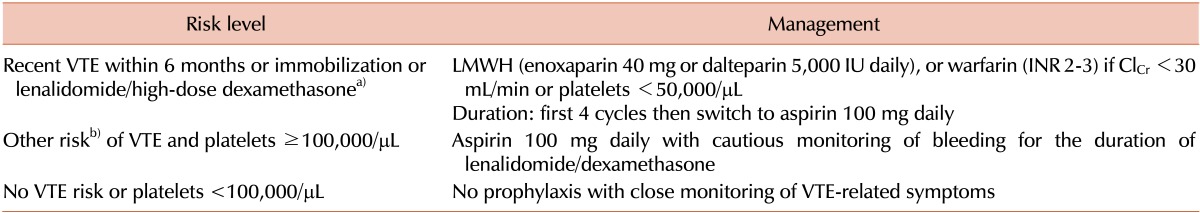

Compared with data from the MM-009 and MM-010 studies, a retrospective analysis of data from 110 Korean patients with RRMM who received lenalidomide/dexamethasone showed a relatively low incidence of VTE (2.7%) [17]. Similar findings have been reported previously in Asian patients with RRMM receiving thalidomide [54, 55]. However, as part of a preventative management strategy, all patients to be treated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone therapy for RRMM should be assessed for their additional risk of VTE, with platelet counts checked prior to the start of therapy and the appropriate method of thromboprophylaxis considered (Table 3) [23, 56].

Table 3. Prophylactic management of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

a)Dexamethasone 480 mg/month. b)Elderly patients aged ≥75 years, history of VTE, ECOG PS 2 or more, medical comorbidity such as infection, renal disease, pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, arterial thromboembolism, hereditary or acquired thrombophilia, concomitant erythropoietin therapy, body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 [56, 64].

Abbreviations: ClCr, creatinine clearance; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; INR, International Normalized Ratio; LMWH, low molecular-weight heparin.

▪ Expert recommendations

• When the combination of lenalidomide and dexamethasone is considered for patients with RRMM, it is important to assess each patient's VTE risk and consider appropriate prophylaxis (Table 3).

• Four months' injection of low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or administration of warfarin are appropriate prophylactic measures for patients with additional VTE risk factors such as recent VTE, immobilization, or lenalidomide combined with high-dose dexamethasone (480 mg/month).

• Patients without additional VTE risk factors or those with platelet counts <100,000/µL should be monitored for VTE symptoms without prophylaxis.

Infection and teratogenicity

Despite the frequent occurrence of neutropenia in RRMM patients treated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone, the regimen is generally not associated with febrile infectious episodes [45]. In MM-009/MM-010 and MM-016 (expanded safety experience), grade 3 or higher pneumonia occurred in 9.1% and 7.1% of patients with RRMM treated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone [26, 57]. Pneumonia (grade 3 or higher) was also found to occur in 9.1% of patients in a retrospective Korean study in which 110 patients with RRMM received lenalidomide/dexamethasone [17].

An analog of thalidomide, lenalidomide has demonstrated teratogenic effects in monkeys [58]. The potential transfer of lenalidomide from a male undergoing treatment with lenalidomide to a female partner via semen during unprotected intercourse is a concern. Human pharmacokinetic data indicate that lenalidomide is detected in human semen, but only at a very low percentage of the administered dose (<0.01%) [39, 59]. Consequently, caution should be exercised in women of childbearing potential and in sexually active male patients. Complete abstinence or contraception must be used by female patients of childbearing potential, and male patients must practice complete abstinence or use condoms throughout the treatment duration, including dose interruptions, and for 1 week after treatment discontinuation if their partner is pregnant or is of childbearing potential and does not use contraception [10].

▪ Expert recommendations

• To prevent infection, routine antibiotic prophylaxis (e.g., trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, quinolones, or penicillin) is highly recommended for the first 3 cycles of lenalidomide when combined with dexamethasone, particularly for patients with aggressive disease or a history of neutropenia or infectious complications [21].

• The use of vaccinations, including influenza, should also be considered in MM patients.

• Due to the teratogenic potential of lenalidomide, caution must be exercised in women of childbearing potential and in sexually active male patients.

TREATMENT OF ADVERSE EVENTS

Neutropenia, thromboembolic events, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and pneumonia were the most commonly reported grade 3 or higher adverse events in the MM-009 and MM-010 trials after long-term follow-up [26]. The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events reported in the expanded safety study (MM-016) were hematologic events (45%), fatigue (10%), and pneumonia (7%) [57]. The toxicity profile of lenalidomide/dexamethasone in patients with RRMM in Asian studies has generally been shown to be comparable to that reported in multinational studies [17, 18, 19]. Of note, unlike thalidomide and bortezomib, lenalidomide-based therapy is rarely associated with peripheral neuropathy. During long-term follow-up of patients in the MM-009 and MM-010 studies, the incidence of grade 2 and 3 peripheral neuropathy was only 1.4% [26]. No grade 3 or 4 peripheral neuropathy has been reported in studies conducted in Asian patients [17, 18].

Hematologic toxicities

The most common grade ≥3 hematologic toxicities, occurring significantly more often with lenalidomide/dexamethasone than with dexamethasone/placebo in the MM-009 and MM-010 studies, were neutropenia (35.5% vs. 3.4%; P<0.05), thrombocytopenia (13.0% vs. 6.3%; P<0.05), and anemia (10.8% vs. 6.0%; P<0.001) [26]. Hematologic toxicities (45%) also represented the most common grade ≥3 adverse events in the lenalidomide expanded access program in patients with RRMM [57]. In a Korean study, neutropenia (59.1%), anemia (43.7%), and thrombocytopenia (43.6%) were the most common grade 3-4 hematologic adverse events reported in 110 patients with RRMM who received lenalidomide/dexamethasone [17].

Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia are clinically significant and usually occur during the initial lenalidomide/dexamethasone cycles, with a decreasing frequency thereafter [48]. They are generally predictable and manageable [60].

▪ Expert recommendations

• At the beginning of each new cycle, lenalidomide treatment should be delayed for 1 week if neutropenia (ANC <1,000 cells/µL) is present. When severe neutropenia (ANC 500 cells/µL) occurs, lenalidomide treatment should be interrupted and G-CSF support should be added. If not contraindicated, dexamethasone should be continued.

• Lenalidomide treatment can be resumed if ANC has returned to 1,000 cells/µL [23, 26, 45]. If ANC remains <1,000 cells/µL, a lenalidomide dose reduction, by 1 dose step, is necessary [45]. Further episodes of grade 3 or higher neutropenia require lenalidomide interruption (until ANC rises to >1,000 cells/µL) and/or dose reductions [45].

• Management of low platelet counts (<30,000 cells/µL) involves a combination of platelet transfusions, lenalidomide dose modification, or treatment discontinuation [23, 26].

Non-hematologic toxicities

Pulmonary thromboembolism and deep vein thrombosis

A retrospective subgroup analysis of data from 353 patients with RRMM treated with lenalidomide/high-dose dexamethasone in the 2 pivotal studies, MM-009 and MM-010, assessed whether the subsequent development of VTE had an impact on survival. Overall, 17% of patients developed VTE, but they did not experience shorter OS or TTP [61].

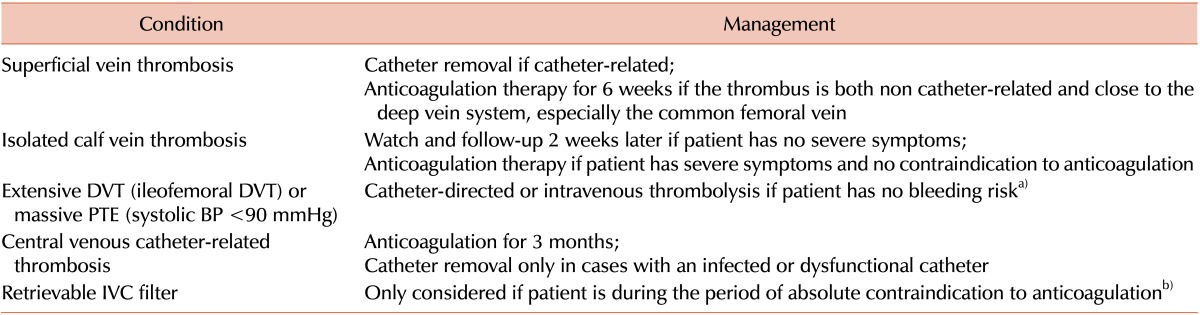

Although the treatment of cancer-associated thrombosis remains challenging, and it is limited by the paucity of evidence-based data, anticoagulation is the established cornerstone of treatment. The decision as to whether to treat with an anticoagulant or not depends on an assessment of the severity of thrombus burden, risk of bleeding, convenience of treatment, potential interaction with anticancer therapy, and life expectancy [62]. Based on American College of Chest Physicians guidelines, LMWH is the preferred therapy for both initial and long-term anticoagulation treatment [63]. Alternative anticoagulation therapy may consist of unfractionated heparin, warfarin, or new oral anticoagulants (e.g., rivaroxaban or dabigatran). In patients with active cancer, anticoagulation can be extended beyond 3 months [63]. Table 4 outlines special considerations in cancer-associated VTE treatment [64].

Table 4. Special conditions in cancer-associated venous thromboembolism (VTE) [64].

a)History of hemorrhagic stroke or stroke of unknown origin; intracranial tumor; ischemic stroke within 3 months; history of major trauma, surgery or head injury within 3 weeks; platelets <100,000/µL; active bleeding; bleeding diathesis. b)Recent CNS bleed; intracranial or spinal lesion at high risk for bleeding; active bleeding with more than 2 units transfused in 24 hours.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CNS, central nervous system; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; IVC, inferior vena cava; PTE, pulmonary thromboembolism.

▪ Expert recommendations

• Anticoagulation is the standard treatment when patients develop pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) and/or DVT during lenalidomide/dexamethasone treatment.

• Severity of thrombus burden, risk of bleeding, convenience of treatment, interaction with anti-cancer treatment, and life expectancy should be considered before the start of anticoagulation. LMWH is recommended preferentially over warfarin or new oral anticoagulants in the treatment of PTE/DVT.

Secondary primary malignancies

A post hoc analysis of pooled data from the MM-009 and MM-010 trials reported a low incidence of secondary primary malignancies (SPMs) in patients with RRMM who received lenalidomide/dexamethasone [65]. Overall, in lenalidomide/dexamethasone recipients, there were 2 cases of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), 8 cases of solid tumors, and no cases of AML or B-cell malignancies. Standardized incidence ratios indicated that patients with RRMM treated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone had no increased risk of developing solid tumors [65]. Another analysis which assessed pooled data from 11 lenalidomide-containing studies in 3,839 patients with RRMM, including some with a lenalidomide treatment duration ≥2 years, demonstrated an SPM incidence rate of 2.15 per 100 patient-years, including MDS (8 cases), B-cell malignancies (2 cases), and AML (1 case). However, the incidence of SPMs was considered consistent with the incidence observed previously [66].

▪ Expert recommendations

• Appropriate caution should be exercised to ensure that patients treated with lenalidomide are followed up closely with regard to monitoring/assessment of SPM.

Other adverse events

Based on data from the expanded safety experience with lenalidomide/dexamethasone in patients with RRMM (MM-016), other commonly reported non-hematologic adverse events (all grades) included fatigue (55.4%), constipation (23.7%), muscle cramps (23.5%), diarrhea (20.7%), nausea (18.9%), and rash (12.9%) [57]. Corresponding data from a retrospective analysis of 110 Korean RRMM patients treated with lenalidomide/dexamethasone indicated slightly lower incidence rates of these adverse events: fatigue (45.5%), constipation (17.2%), muscle cramps (10.9%), diarrhea (10.8%), nausea (7.2%), and rash (10.0%) [17]. Anorexia was reported at a higher incidence in the Korean study than in the MM-016 expanded safety study (20.9% vs. 10.2%) [17, 57]; the clinical relevance, if any, is unclear. Although not reported in any of the clinical trials of lenalidomide/dexamethasone in patients with RRMM, cases of potential lenalidomide-associated hepatotoxicity [67] and thyroid dysfunction [68] have been recorded in the literature.

▪ Expert recommendations

• In general, symptoms such as fatigue, diarrhea, constipation, and rash can be managed routinely without the need for lenalidomide dose adjustment.

• In specific cases, at the discretion of the treating physician, severe adverse events may warrant lenalidomide dose reduction, interruption, or discontinuation until the event has resolved.

• Routine liver and thyroid function monitoring is recommended during lenalidomide therapy.

CONCLUSION

Evidence from pivotal multinational clinical trials has demonstrated the superior efficacy and predictable and manageable tolerability profile of lenalidomide when used in combination with dexamethasone, compared with dexamethasone alone, in patients with RRMM [15, 16]. Recent additional evidence from clinical trials conducted in Asian patients with RRMM [17, 18, 19], real world experience [30, 69], and a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical studies of lenalidomide-based treatment for patients with MM [70], provides further support for the use of lenalidomide/dexamethasone in patients with RRMM.

Based on a recent epidemiologic analysis of 3,405 Asian patients with MM, there do not appear to be any significant ethnic differences between Western and Asian populations with regard to clinical or cytogenetic features of MM [17]. Nevertheless, given the rapidly increasing incidence of MM in Korea [17], similar to increases being observed in other Asian countries [71], there are requirements for a set of practical guidelines that will assist Korean clinicians to manage their patients better.

Recent Asian resource-stratified guidelines for the management of MM recognize that, at a pan-Asian level, the delivery of optimal care to all patients with MM is hindered due to large economic and healthcare infrastructure disparities, and varying access to novel drugs [72]. At a country-specific level, even in Asian countries which fall into the high-income category, with national healthcare systems, restrictions on healthcare reimbursement are often imposed which can limit the availability and/or use of specific drugs [72]. In Korea, lenalidomide has been reimbursed since March 2013 for patients with RRMM who have failed bortezomib treatment.

With regard to ongoing and potential future developments, lenalidomide is being evaluated in various therapeutic combinations in patients with RRMM. It is also being evaluated as maintenance therapy following autologous stem cell transplantation (SCT). Other investigational combinations currently being evaluated in early phase clinical trials include lenalidomide in combination with everolimus, and lenalidomide/dexamethasone in combination with panobinostat, bevacizumab, SGN-40, perifosine, vorinostat, dasatinib, NPI-0002, or carfilzomib [73]. Lenalidomide is also being evaluated as monotherapy in patients who have relapsed after prior SCT [73]. Although these investigational studies will have no short-term impact on the current indicated use of lenalidomide in Korean patients with RRMM, data from ongoing clinical studies are awaited with anticipation.

Furthermore, given the continual focus by stakeholders on the use of healthcare resources, an alternative lenalidomide dosing (on alternate days) schedule has recently been evaluated in a preliminary retrospective UK analysis of 39 patients with RRMM experiencing grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicity [74]. The alternative schedule yielded significant cost savings, while maintaining efficacy, compared with the recommended lenalidomide dose reduction. Prospective evaluation of the alternative dosing schedule is warranted.

In summary, lenalidomide is a distinct second-generation immunomodulatory drug that possesses activity against hematologic malignancies, in particular MM. The combination of lenalidomide/dexamethasone is approved for the treatment of patients with RRMM. Results from multinational pivotal phase III trials in this setting have demonstrated that lenalidomide/dexamethasone leads to significantly improved OS compared with dexamethasone alone. In addition, smaller studies in Asian populations (including Korea) support the findings from pivotal trials, demonstrating that lenalidomide is an effective option in the treatment of RRMM in Korea. Optimal clinical benefits are seen when lenalidomide/dexamethasone is initiated at first relapse and continued, beyond best treatment response, until disease progression. Importantly, lenalidomide has a predictable and manageable tolerability profile, with minimal neurotoxicity, allowing long-term administration. Future studies will determine the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide in novel combinations, with potentially complimentary agents, for the treatment of RRMM.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank David P. Figgitt, PhD, Content Ed Net, for providing independent medical writing assistance in the preparation of this article, with funding from Celgene Korea.

Footnotes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Raab MS, Podar K, Breitkreutz I, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2009;374:324–339. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park HJ, Park EH, Jung KW, et al. Statistics of hematologic malignancies in Korea: incidence, prevalence and survival rates from 1999 to 2008. Korean J Hematol. 2012;47:28–38. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2012.47.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vallet S, Podar K. New insights, recent advances, and current challenges in the biological treatment of multiple myeloma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13(Suppl 1):S35–S53. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2013.807337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JH, Lee DS, Lee JJ, et al. Multiple Myeloma Working Party. Multiple myeloma in Korea: past, present, and future perspectives. Experience of the Korean Multiple Myeloma Working Party. Int J Hematol. 2010;92:52–57. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0617-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim K, Lee JH, Kim JS, et al. Clinical profiles of multiple myeloma in Asia-An Asian Myeloma Network study. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:751–756. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SJ, Kim K, Kim BS, et al. Korean Multiple Myeloma Working Party. Clinical features and survival outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma: analysis of web-based data from the Korean Myeloma Registry. Acta Haematol. 2009;122:200–210. doi: 10.1159/000253027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Niesvizky R. How lenalidomide is changing the treatment of patients with multiple myeloma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88(Suppl 1):S23–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mariz JM, Esteves GV. Review of therapy for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: focus on lenalidomide. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24(Suppl 2):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000410243.84074.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larocca A, Cavallo F, Mina R, Boccadoro M, Palumbo A. Current treatment strategies with lenalidomide in multiple myeloma and future perspectives. Future Oncol. 2012;8:1223–1238. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Revlimid® Prescribing Information (Revlimid capsules 5 mg/10 mg/15 mg/25 mg) Incheon, Korea: Celegene International Sarl; 2013. [Accessed February 28, 2015]. at http://drug.mfds.go.kr/html/bxsSearchDrugProduct.jsp?item_Seq=200909430. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quach H, Ritchie D, Stewart AK, et al. Mechanism of action of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDS) in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2010;24:22–32. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito T, Ando H, Suzuki T, et al. Identification of a primary target of thalidomide teratogenicity. Science. 2010;327:1345–1350. doi: 10.1126/science.1177319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu YX, Kortuem KM, Stewart AK. Molecular mechanism of action of immune-modulatory drugs thalidomide, lenalidomide and pomalidomide in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:683–687. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.728597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain PP, Lopez-Girona A, Miller K, et al. Structure of the human Cereblon-DDB1-lenalidomide complex reveals basis for responsiveness to thalidomide analogs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:803–809. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, et al. Multiple Myeloma (009) Study Investigators. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2133–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. Multiple Myeloma (010) Study Investigators. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2123–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim K, Kim SJ, Voelter V, et al. Korean Multiple Myeloma Working Party (KMMWP) Lenalidomide with dexamethasone treatment for relapsed/refractory myeloma patients in Koreaexperience from 110 patients. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1893-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou J, Du X, Jin J, et al. A multicenter, open-label, phase 2 study of lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone in Chinese patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: the MM-021 trial. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iida S, Chou T, Okamoto S, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone treatment in Japanese patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Int J Hematol. 2010;92:118–126. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0624-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harousseau JL, Dreyling M ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Multiple myeloma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v155–v157. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Attal M, et al. European Myeloma Network. Optimizing the use of lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: consensus statement. Leukemia. 2011;25:749–760. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barosi G, Merlini G, Billio A, et al. SIE, SIES, GITMO evidence-based guidelines on novel agents (thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide) in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:875–888. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1445-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reece D, Kouroukis CT, Leblanc R, Sebag M, Song K, Ashkenas J. Practical approaches to the use of lenalidomide in multiple myeloma: a canadian consensus. Adv Hematol. 2012;2012:621958. doi: 10.1155/2012/621958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C, Baldassarre F, Kanjeekal S, Herst J, Hicks L, Cheung M. Lenalidomide in multiple myeloma-a practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:e136–e149. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lonial S. Relapsed multiple myeloma. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:303–309. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimopoulos MA, Chen C, Spencer A, et al. Long-term follow-up on overall survival from the MM-009 and MM-010 phase III trials of lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009;23:2147–2152. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palumbo A, Mateos MV, Bringhen S, San Miguel JF. Practical management of adverse events in multiple myeloma: can therapy be attenuated in older patients? Blood Rev. 2011;25:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stadtmauer EA, Weber DM, Niesvizky R, et al. Lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone at first relapse in comparison with its use as later salvage therapy in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol. 2009;82:426–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang M, Dimopoulos MA, Chen C, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone is more effective than dexamethasone alone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma regardless of prior thalidomide exposure. Blood. 2008;112:4445–4451. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-141614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katodritou E, Vadikolia C, Lalagianni C, et al. "Real-world" data on the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who were treated according to the standard clinical practice: a study of the Greek Myeloma Study Group. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:129–139. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1841-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.San-Miguel JF, Dimopoulos MA, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Effects of lenalidomide and dexamethasone treatment duration on survival in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide and dexamethasone. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:38–43. doi: 10.3816/CLML.2010.n.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harousseau JL, Dimopoulos MA, Wang M, et al. Better quality of response to lenalidomide plus dexamethasone is associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2010;95:1738–1744. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.015917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zago M, Oehrlein K, Rendl C, Hahn-Ast C, Kanz L, Weisel K. Lenalidomide in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma disease: feasibility and benefits of long-term treatment. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1993–1999. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fouquet G, Tardy S, Demarquette H, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of long-term exposure to lenalidomide in patients with recurrent multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2013;119:3680–3686. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cerrato C, Mina R, Palumbo A. Optimal management of elderly patients with myeloma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14:217–228. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2014.856269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2011. Korea Central Cancer Registry. Seoul, Korea: National Cancer Center; 2013. [Accessed November 4, 2014]. at http://www.ncc.re.kr/english/infor/kccr.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chanan-Khan AA, Lonial S, Weber D, et al. Lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone improves survival and time-to-progression in patients ≥65 years old with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Int J Hematol. 2012;96:254–262. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, et al. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70284-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen N, Wen L, Lau H, Surapaneni S, Kumar G. Pharmacokinetics, metabolism and excretion of [(14)C]-lenalidomide following oral administration in healthy male subjects. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:789–797. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1760-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dimopoulos M, Alegre A, Stadtmauer EA, et al. The efficacy and safety of lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma patients with impaired renal function. Cancer. 2010;116:3807–3814. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Goldschmidt H, Alegre A, Mark T, Niesvizky R. Treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma and renal impairment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:1012–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dimopoulos MA, Christoulas D, Roussou M, et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone for the treatment of refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma: dosing of lenalidomide according to renal function and effect on renal impairment. Eur J Haematol. 2010;85:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oehrlein K, Langer C, Sturm I, et al. Successful treatment of patients with multiple myeloma and impaired renal function with lenalidomide: results of 4 German centers. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012;12:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tosi P, Gamberi B, Castagnari B, et al. Lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone in elderly patients with advanced, relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma and renal failure. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2013;5:e2013037. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2013.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palumbo A, Bladé J, Boccadoro M, et al. How to manage neutropenia in multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012;12:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennett CL, Angelotta C, Yarnold PR, et al. Thalidomide- and lenalidomide-associated thromboembolism among patients with cancer. JAMA. 2006;296:2558–2560. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2558-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carrier M, Le Gal G, Tay J, Wu C, Lee AY. Rates of venous thromboembolism in multiple myeloma patients undergoing immunomodulatory therapy with thalidomide or lenalidomide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:653–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishak J, Dimopoulos MA, Weber D, Knight RD, Shearer A, Caro JJ. Declining rates of adverse events and dose modifications with lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone. Blood. 2008;112:abst 3708. ASH Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jang MJ, Bang SM, Oh D. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in Korea: from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee KW, Bang SM, Kim S, et al. The incidence, risk factors and prognostic implications of venous thromboembolism in patients with gastric cancer. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:540–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang MJ, Ryoo BY, Ryu MH, et al. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients with advanced gastric cancer: an Asian experience. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:492–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi S, Lee KW, Bang SM, et al. Different characteristics and prognostic impact of deep-vein thrombosis / pulmonary embolism and intraabdominal venous thrombosis in colorectal cancer patients. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:1084–1094. doi: 10.1160/TH11-07-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun JM, Kim TS, Lee J, et al. Unsuspected pulmonary emboli in lung cancer patients: the impact on survival and the significance of anticoagulation therapy. Lung Cancer. 2010;69:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koh Y, Bang SM, Lee JH, et al. Korean Multiple Myeloma Working Party. Low incidence of clinically apparent thromboembolism in Korean patients with multiple myeloma treated with thalidomide. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:201–206. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0807-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu SY, Yeh YM, Chen YP, Su WC, Chen TY. Low incidence of thromboembolism in relapsed/refractory myeloma patients treated with thalidomide without thromboprophylaxis in Taiwan. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1773–1778. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palumbo A, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, et al. International Myeloma Working Group. Prevention of thalidomide- and lenalidomide-associated thrombosis in myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:414–423. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen C, Reece DE, Siegel D, et al. Expanded safety experience with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2009;146:164–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amin RP, Fuchs A, Christian MS, et al. An embryo-fetal developmental toxicity study of lenalidomide in cynomolgus monkeys. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009;85(Suppl):435. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen N, Lau H, Choudhury S, Wang X, Assaf M, Laskin OL. Distribution of lenalidomide into semen of healthy men after multiple oral doses. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50:767–774. doi: 10.1177/0091270009355157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lonial S, Baz R, Swern AS, Weber D, Dimopoulos MA. Neutropenia is a predictable and early event in affected patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone. Blood. 2009;114 (Ash Annual Meeting):abst 2879. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zangari M, Tricot G, Polavaram L, et al. Survival effect of venous thromboembolism in patients with multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide and high-dose dexamethasone. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:132–135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee AY. Anticoagulation in the treatment of established venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4895–4901. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S–e494S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Cancer-associated venous thromboembolic disease. Version 1. 2014. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2014. [Accessed October 2, 2014]. at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dimopoulos MA, Orlowski RZ, Niesvizky R, Lonial S, Brandenburg NA, Weber DM. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone (LEN plus DEX) treatment in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) patients (pts) and risk of second primary malignancies (SPM): Analysis of MM-009/010. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15 Suppl):abst 8009. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morgan G, Durie B, San Miguel J, et al. Retrospective analysis of the long term safety of lenalidomide (LEN) ± dexamethasone (DEX) in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) patients (PTS): analysis of pooled data and incidence rates (IR) of second primary malignancy (SPM) Haematologica. 2011;96(Suppl 1):S24. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hussain S, Browne R, Chen J, Parekh S. Lenalidomide-induced severe hepatotoxicity. Blood. 2007;110:3814. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Figaro MK, Clayton W, Jr, Usoh C, et al. Thyroid abnormalities in patients treated with lenalidomide for hematological malignancies: results of a retrospective case review. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:467–470. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.João C, Coelho I, Costa C, Esteves S, Lucio P. Efficacy and safety of lenalidomide in relapse/refractory multiple myeloma--real life experience of a tertiary cancer center. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:97–105. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang B, Yu RL, Chi XH, Lu XC. Lenalidomide treatment for multiple myeloma: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang SY, Yao M, Tang JL, et al. Epidemiology of multiple myeloma in Taiwan: increasing incidence for the past 25 years and higher prevalence of extramedullary myeloma in patients younger than 55 years. Cancer. 2007;110:896–905. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tan D, Chng WJ, Chou T, et al. Management of multiple myeloma in Asia: resource-stratified guidelines. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e571–e581. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Richardson P, Mitsiades C, Laubach J, et al. Lenalidomide in multiple myeloma: an evidence-based review of its role in therapy. Core Evid. 2010;4:215–245. doi: 10.2147/ce.s6002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Popat R, Khan I, Dickson J, et al. An alternative dosing strategy of lenalidomide for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:148–151. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]