Abstract

Nitrooleic acid (OA-NO2) is endogenous ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. The present study was aimed at investigating the beneficial effects of OA-NO2 on the lipid metabolism and liver steatosis in deoxycorticosterone acetate- (DOCA-) salt induced hypertensive mice model. Male C57BL/6 mice were divided to receive DOCA-salt plus OA-NO2 or DOCA-salt plus vehicle and another group received neither DOCA-salt nor OA-NO2 (control group). After 3-week treatment with DOCA-salt plus 1% sodium chloride in drinking fluid, the hypertension was noted; however, OA-NO2 had no effect on the hypertension. In DOCA-salt treated mice, the plasma triglyceride and total cholesterol levels were significantly increased compared to control mice, and pretreatment with OA-NO2 significantly reduced these parameters. Further, the histopathology of liver exhibited more lipid distribution together with more serious micro- and macrovesicular steatosis after DOCA-salt treatment and that was consistent with liver tissue triglyceride and nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) content. The mice pretreated with OA-NO2 showed reduced liver damage accompanied with low liver lipid content. Moreover, the liver TBARS, together with the expressions of gp91phox and p47phox, were parallelly decreased. These findings indicated that OA-NO2 had the protective effect on liver injury against DOCA-salt administration and the beneficial effect could be attributed to its antihyperlipidemic activities.

1. Introduction

Hypertension is the most common cardiovascular disease and the prevalence of hypertension is projected to increase globally, especially in the developing countries. The metabolic abnormalities including lipid metabolism in hypertensive patients draw attention of the researchers considering the close association between them. There is increasing evidence for the strong relationship of hypertension and dyslipidemia. Metabolic abnormalities including hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, and insulin resistance were found in many hypertensive patients [1, 2]. Hypertension and dyslipidemia are major risk factors for cardiovascular disease, accounting for the highest morbidity and mortality among the patient population with cardiovascular disease. Hence, enormous studies have been focused on developing therapeutic agents for hypertension and its related lipid metabolism. There are several classical animal models existing for the hypertension study. Deoxycorticosterone acetate- (DOCA-) salt induced hypertensive animal model has been widely used for studying hypertension and hypertension-related organ damage. In the past decades, the increase of both circulating and membrane lipids was observed in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats prior to induction of hypertension [3, 4]. Meanwhile, the alteration of membrane phospholipids content, phospholipid distribution, and degree of fatty acid saturation were found in DOCA-salt hypertensive animals [3]. The changes in membrane lipid composition may modulate membrane function in a long-term mode, contributing to blood pressure regulation and heart, liver, and kidney organ dysfunction.

Nitrated free fatty acids (NO2-FA), notably nitroalkene derivatives of linoleic acid (nitrolinoleic acid) and nitrooleic acid (OA-NO2), are endogenous molecules with several attractive signaling properties [5, 6]. Nitroalkenes are found to be robust endogenous ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), although they also activate PPARα and PPARδ at increasing concentrations [5, 6]. The agonists of PPARs are therapeutically used to treat dyslipidemia and hyperglycaemia associated with the metabolic syndrome. However, the serious side effects of certain PPARs agonists such as PPARγ agonists from the thiazolidinedione type led to its limitation in clinical practice, which further increased the demand for the discovery of novel ligands. The endogenous ligand for PPARs has proven historically to be a promising pool of structures for drug discovery, and a significant research effort has recently been undertaken to explore the biological functions of the natural products. In a previous study, it was demonstrated that OA-NO2 significantly reduced the plasma triglycerides, almost normalized the plasma free fatty acids, and prevented the body weight gain without fluid retention in obese Zucker rats [7]. The present study aimed to examine the potential therapeutic effects of OA-NO2 for the dyslipidemia in DOCA-salt induced hypertensive mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (8–10-week-old) were purchased from the Animal Center of Shandong University. All animals were fed using standard rodent chow with hand free access to water, and 12-hour light/dark cycle was maintained. All protocols employing mice were conducted in accordance with the principles and guidance of the Ethics Committee of the Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University.

2.2. Materials

9- and 10-nitrooleic acids are two regioisomers of OA-NO2, which are formed by nitration of oleic acid in approximately equal proportions in vivo [8]. Both compounds were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and used as a 1 : 1 mixture of the isomers.

2.3. Animal Experiments

The OA-NO2 was dissolved in 100% DMSO at 100 mg/mL. The mice were randomly divided into the following groups, mice were pretreated for 48 h with DMSO (DOCA-salt + vehicle) or OA-NO2 (DOCA-salt + OA-NO2) at 2 mg/kg/d via a microosmotic pump (DURECT Corporation, Cupertino, CA, USA), and then both groups were subject to DOCA-salt treatment. Under anesthesia with isoflurane, a slow-release (21-day) 50 mg DOCA pellet was implanted subcutaneously through a midscapular incision. Sham-operated animals served as controls. After the surgery, animals received 1% sodium chloride in drinking water and a normal salt diet for 3 weeks. Food intake, water intake, body weight, and urine volume were determined once per week in metabolic cages. At the end of the experiments, animals were fasted overnight before blood sampling, which was performed by making a small cut (~2 mm) in the tail using razor blade.

2.4. Blood Pressure Measurement

Systolic blood pressure was measured by a tail-cuff method using a Visitech BP2000 Blood Pressure Analysis System (Apex, NC, USA). All animals were habituated to the blood pressure measurement device for 7 days. All mice underwent 2 cycles of 20 measurements reordered per day for a minimum of 3 days.

2.5. Measurement of Biochemical Parameters and Cytokine

Blood samples from anesthetized mice were collected by puncturing vena cava using 1 cc insulin syringe containing 50 μL of 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in the absence of protease inhibitors. Plasma levels of triglyceride, cholesterol, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were measured using a blood chemistry analyzer.

For analysis of hepatic triglyceride and nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA), liver tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen and dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride. The NEFA levels were determined from the supernatant using the commercial enzymatic colorimetric kits (Wako Chemicals, VA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The liver triglyceride levels were determined using an L-type triglyceride H kit (Wako Chemicals, VA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.6. Histopathological Analysis

After 3 weeks of treatment with DOCA-salt, the mice were euthanized and the livers were excised, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin embedded tissues were sectioned at 4 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) by standard methods. Hepatic steatosis was blindly assessed on 4 random fragments from different areas of each liver and was staged on a scale of 0 to 4, according to the percentage of hepatocytes containing cytoplasmic vacuoles as follows: 0 (<5%), 1 (5–20%), 2 (20%–30%), 3 (30–60%), and 4 (≥60%). Frozen samples were also stained with Oil-Red-O at the optimal cutting temperature. Slides were analyzed by microscopy using Image J and Microsuite (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions GmbH, Munster, Germany).

2.7. Measurement of Thiobarbituric Acid-Reactive Substances

The measurement of plasma thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) was based on the formation of malondialdehyde using a commercially available TBARS Assay Kit (10009055; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.8. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Mice livers were harvested and preserved in the RNAlater solution (Sangon Biotech, China) at −20°C until ribonucleic acid (RNA) extraction. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA), and complimentary deoxyribonucleic acid was synthesized with SuperScript (TaKaRa Bio, Japan). RT-PCR was carried out using a QuantiTect SYBR Green Kit (Qiagen, Germany) on an ABI Prism 7500 RT-PCR instrument equipped with appropriate software (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). The oligonucleotide sequences used for RT-PCR were as follows (Sangon Biotech, China): glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, sense 5′-GTCTTCACTACCATGGAGAGG-3′ and antisense 5′-TCATGGATGACCTTGGCCAG-3′; p47phox, sense 5′-GTCGTGGAGAAGAGCGAGAG-3′ and antisense 5′-CGCTTTGATGGTTACATACGG-3′; gp91phox, sense 5′-CCGTATTGTGGGAGACTGGA-3′.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All values were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using a student t-test or analysis of variance. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of OA-NO2 on Body Weight Loss

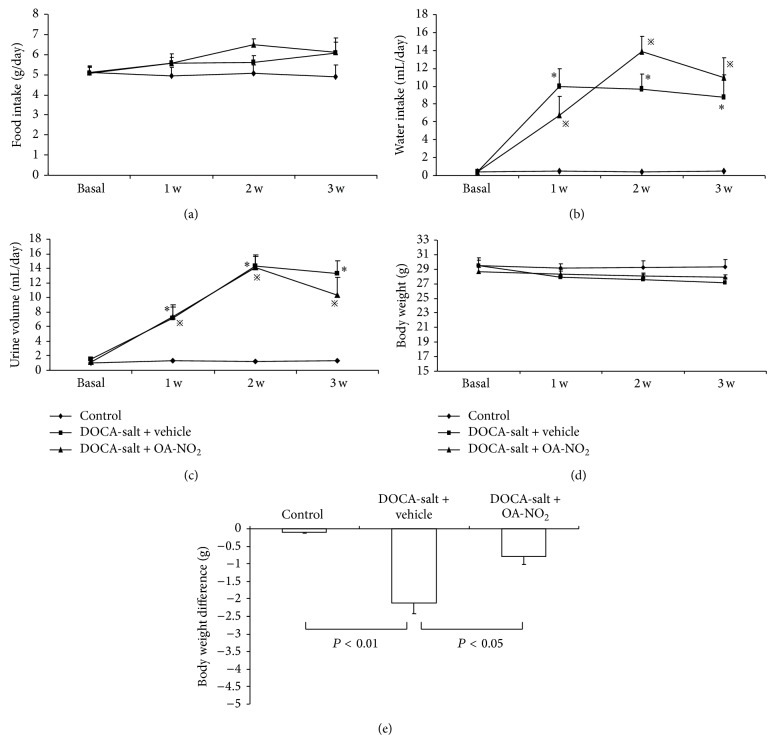

During the 3-week treatment, food intake, water intake, body weight, and urine volume were determined once per week in metabolic cages. There were no differences among the control, DOCA-salt + vehicle, and DOCA-salt + OA-NO2 groups in food intake (Figure 1(a)), while the water intake increased strikingly after implanting the DOCA pellet together with high salt drinking water; however, OA-NO2 has no effect on the alteration of the water intake (Figure 1(b)). The urine volume had the same pattern similar to water intake (Figure 1(c)). Although there were no differences in the food intake, the DOCA-salt treatment induced the body weight loss (control: −0.11 ± 0.02 versus DOCA-salt + vehicle: −2.1 ± 0.31, P < 0.01), which was less in OA-NO2 treatment group (DOCA-salt + OA-NO2: −0.79 ± 0.23) (P < 0.05) (Figure 1(e)).

Figure 1.

Food intake (a), water intake (b), urine volume (c), body weight (d), and body weight difference (e) in control (n = 5), DOCA-salt + vehicle (n = 8), and DOCA-salt + OA-NO2 (n = 8) mice. * P < 0.05, compared with control; ※ P < 0.05, compared with control; data are shown as mean + SE.

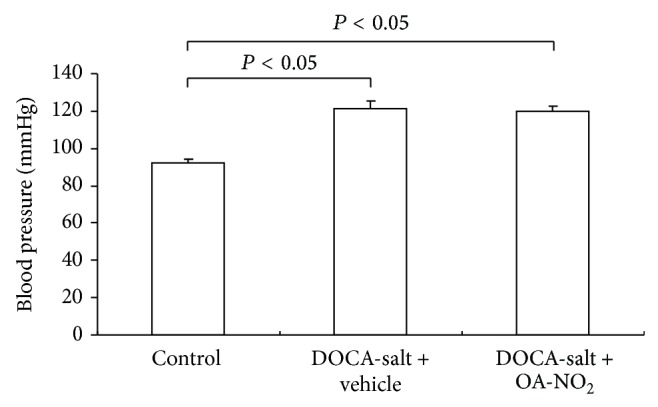

3.2. Effect of OA-NO2 on Blood Pressure

After 3-week treatment with DOCA-salt, the mice exhibited higher blood pressure than control mice (control: 92.5 ± 2.23 versus DOCA-salt + vehicle: 121.5 ± 4.38, P < 0.05); however, OA-NO2 had no effect on the hypertension (Figure 2). The result was different from the previous study results where the OA-NO2 inhibited angiotensin II-induced hypertension [12].

Figure 2.

The changes of blood pressure in control (n = 5), DOCA-salt + vehicle (n = 8), and DOCA-salt + OA-NO2 (n = 8) mice after 3 weeks of DOCA-salt treatment. Data are shown as mean + SE.

3.3. Effect of OA-NO2 on Biochemical Parameters

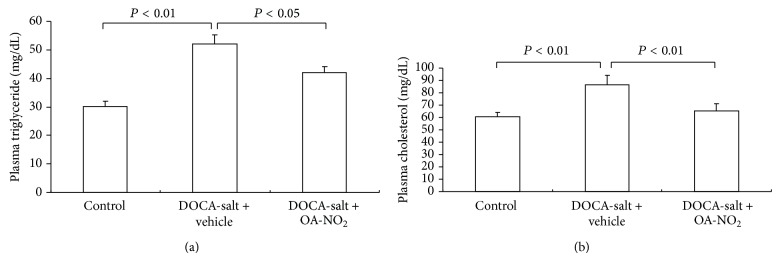

After 3-week treatment, plasma triglyceride concentrations increased in DOCA-salt treated mice (control: 30.1 ± 2.02 versus DOCA-salt + vehicle: 51.9 ± 3.29, P < 0.01), which was reduced to 42.1 ± 2.19 by OA-NO2 treatment (P < 0.05) (Figure 3(a)). A similar increase in the plasma cholesterol concentration after the treatment with DOCA-salt (control: 60.3 ± 4.03 versus DOCA-salt + vehicle: 86.5 ± 7.78, P < 0.01) was observed, and the pretreatment with OA-NO2 almost normalized the plasma cholesterol levels (Figure 3(b)).

Figure 3.

Effect of OA-NO2 on plasma triglyceride (a) and cholesterol (b) in DOCA-salt hypertensive mice. Control: n = 5; DOCA-salt + vehicle: n = 8; DOCA-salt + OA-NO2: n = 8. Data are shown as mean + SE.

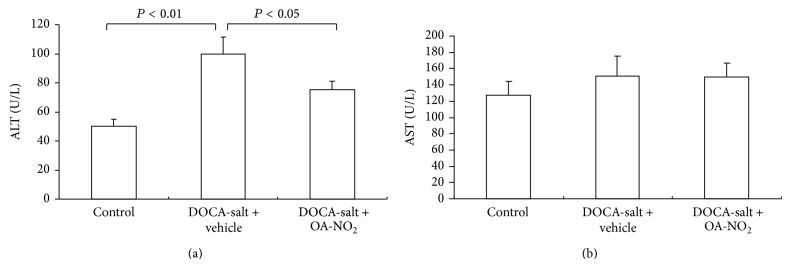

The liver is sensitive to the dyslipidemia, and DOCA-salt treated rats showed fatty changes in hepatocytes in the previous study [9]. Hence, the liver damage was assessed by ALT and AST levels. The plasma ALT rose significantly after DOCA-salt treatment compared with control mice (control: 50.3 ± 5.2 versus DOCA-salt + vehicle: 100.5 ± 11.3, P < 0.05), while the OA-NO2 treatment attenuated the liver injury with reduced ALT (75.5 ± 6.2, P < 0.05) (Figure 4(a)). The DOCA-salt treated mice had slight higher plasma AST values than the control mice; however, there were no statistical differences among the three groups (Figure 4(b)).

Figure 4.

Effect of OA-NO2 on plasma AST and ALT after 3-week DOCA-salt treatment. Control: n = 5; DOCA-salt + vehicle: n = 8; DOCA-salt + OA-NO2: n = 8. Data are shown as mean + SE.

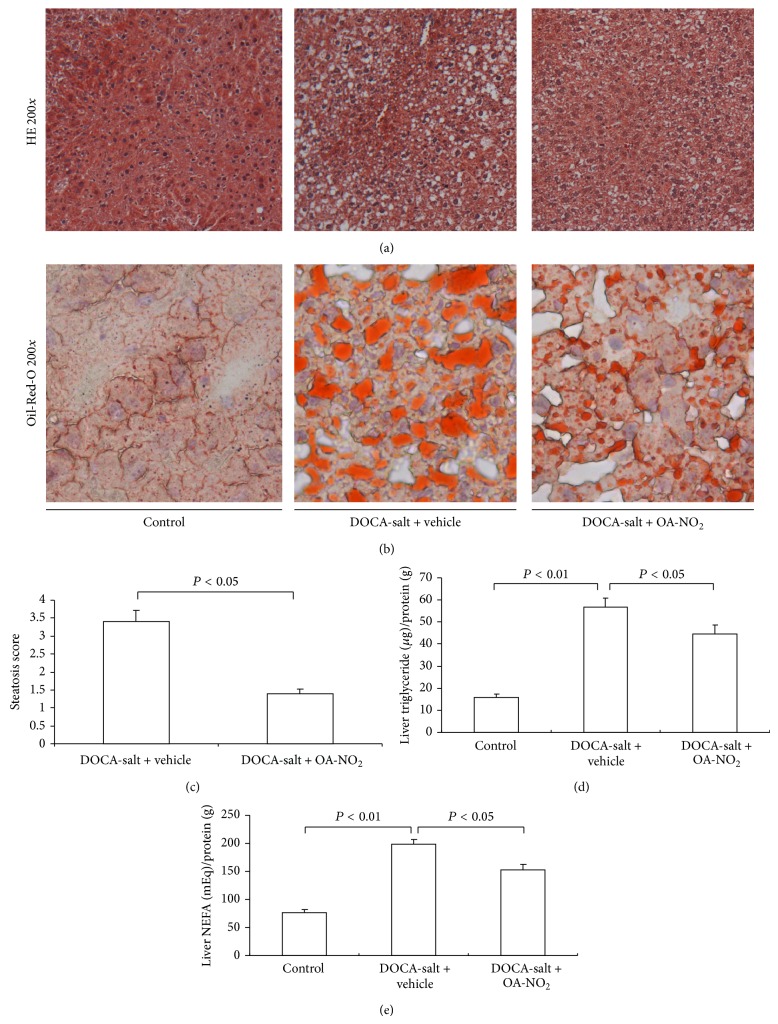

3.4. Effect of OA-NO2 on Liver Steatosis

To assess liver steatosis, the liver sections were evaluated histologically using HE and Oil-Red-O staining. The DOCA-salt treated mice showed significantly more micro- and macrovesicular steatosis, characterized with hypertrophy and globular hyalinization, edema, and hydrophobic changes than control mice (Figures 5(a) and 5(b)), and the pretreatment with OA-NO2 attenuated the histological changes in the liver, as illustrated by the decrease in the steatosis score (Figure 5(c)). With Oil-Red-O staining, the DOCA-salt treated mice showed more lipid accumulation in the liver than the control, while the OA-NO2 strikingly reduced the lipid accumulation.

Figure 5.

Effect of OA-NO2 on the liver steatosis after 3-week DOCA-salt treatment. Morphological analysis of DOCA-salt treated liver injury in control, DOCA-salt + vehicle, and DOCA-salt + OA-NO2 mice. (a) Representative photomicrographs: hematoxylin and eosin staining (magnification 200). (b) Oil-Red-O staining (magnification 200) of livers. (c) Mean liver steatosis score. The lipid content in liver: liver triglyceride (d) and liver NEFA (e). Control: n = 5; DOCA-salt + vehicle: n = 8; DOCA-salt + OA-NO2: n = 8. Data are shown as mean + SE.

After the histological staining, the fatty liver was further evaluated for triglyceride and NEFA levels in the liver tissue. After 4-week treatment, the DOCA-salt treated mice had significantly elevated liver triglyceride (control: 15.9 ± 1.45 versus DOCA-salt + vehicle: 56.7 ± 4.21, P < 0.01) and NEFA (control: 76.3 ± 5.80 versus DOCA-salt + vehicle: 199.1 ± 8.41, P < 0.01) levels compared to control mice (Figures 5(d) and 5(e)), while the OA-NO2 treated mice had less liver triglyceride (44.6 ± 3.91) and NEFA (153.2 ± 9.89) levels compared to DOCA-salt treated mice.

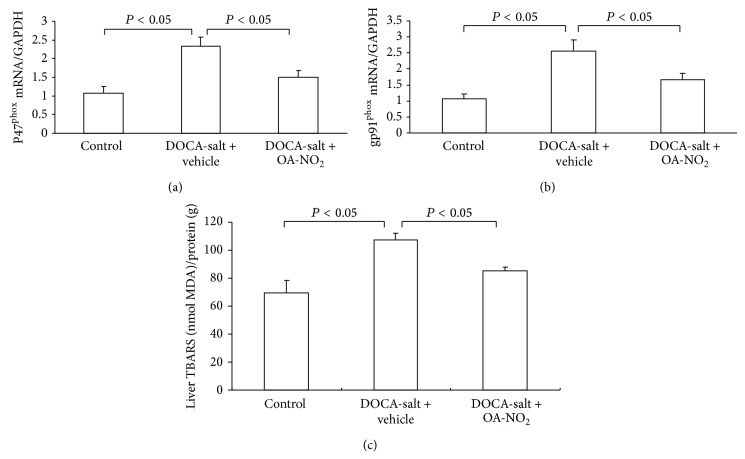

3.5. Effect of OA-NO2 on Oxidative Stress in Liver

The presence of oxidative stress in the liver was evaluated. In the livers of DOCA-salt treated mice, TBAR levels showed 40% increase compared to the control mice; however, this increase was less (24%) in OA-NO2 treated mice. To understand the liver sources of oxidative stress and liver expressions of gp91phox and p47phox, the two major nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase subunits, along with superoxide dismutase- (SOD-) 1 and SOD2, were examined using quantitative RT-PCR. DOCA-salt treatment induced parallel increases in renal gp91phox (2.5-fold; P < 0.05) and p47phox (2.3-fold; P < 0.05) without any effect on SOD1 or SOD2 compared with control mice (data did not show), and these increases were significantly reduced by OA-NO2 treatment (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of OA-NO2 on the oxidative stress after 3-week DOCA-salt treatment. Liver p47phox mRNA expression (a) and gp91phox mRNA expression, and the liver TBARS content (c) in control (n = 5), DOCA-salt + vehicle (n = 8), and DOCA-salt + OA-NO2 (n = 8) mice. Data are shown as mean + SE.

4. Discussion

Nitrated fatty acids are derived from NO- and NO2-dependent redox reactions with unsaturated fatty acids, including OA-NO2 and nitrolinoleic acid [10]. The OA-NO2, a nitrated fatty acid and an endogenous PPARs agonist, has been reported to have relevant biological effects on inflammation [11], hypertension [12], vascular neointimal proliferation [13], obesity with metabolic syndrome [7], hyperglycemia [14], and proteinuria [15] in diabetes without side effects. Hence, a significant research work has recently been undertaken to explore the biological functions of the natural products. In the present study, it was demonstrated that the pretreatment with OA-NO2 produced beneficial effects on hyperlipidemia and liver steatosis with no effect on hypertension in the DOCA-salt induced hypertensive mice model.

In the DOCA-salt induced hypertensive rat model, the animals showed significant elevation in mean arterial pressure, heart rate, and reduction in body weight. A significant increase in the plasma and tissue (liver, kidney, heart, and aorta) lipid levels such as total cholesterol, triglycerides, free fatty acids, and phospholipids was noted in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats [16, 17]. In the present study, it was found that the pretreatment with OA-NO2 lowered the plasma triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations, without any impact on the mice food intake. The present study results were different from previous data, which showed that OA-NO2 produced beneficial effects on obesity and hyperlipidemia, accompanied by an immediate reduction of food intake in obese Zucker rats [7]. The PPARα agonists (Wy-14643 and GW7647) and endogenous PPARα agonists (oleoylethanolamide) treatment reduced the body weight gain and improved the hyperlipidemia via appetite-suppressing effect (within a day) in an obese animal model wherein the hyperlipidemia was mainly due to the high food intake [18–21].

Unlike the obese Zucker rats, the mechanism of the hyperlipidemia of DOCA-salt hypertensive animals was different. Interestingly, in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats, Hernández et al. [22] found that the glucose, glycogen, and triglycerides levels were increased and citrate synthase and beta-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase activities were reduced in the soleus muscle, along with higher plasma triglycerides and cholesterol compared with control rats; the study findings indicated that the hyperlipidemia of the DOCA-salt hypertensive animals was due to the changes of metabolic enzymes and not because of high food intake. The OA-NO2 not only is a robust PPARγ activator but also activates PPARα and PPARδ at increasing concentrations. All three PPAR subtypes have been shown to play a crucial role in whole body lipid homeostasis as well as in insulin sensitivity [23–26]. In spite of the impact of PPARα on the appetite-suppressing effect, both PPARγ and PPARδ have no effect on food intake [18, 27].

The mechanism of action of OA-NO2 in DOCA-salt hypertensive mice remains elusive; however, the involvement of PPARs appears conceivable. All three PPAR isoforms have been identified as therapeutic targets in the treatment of patients with hyperlipidaemia. Among these, PPARα has been found to play a key role in lipid metabolism. PPARα-null mice exhibited higher plasma levels of cholesterol and triglycerides [28] with extensive hepatic lipid accumulation. The PPARα is known to be involved in almost all aspects of lipid metabolism including uptake, binding, and oxidation of fatty acids, lipoprotein assembly, and lipid transport [29]. The PPARγ is also an important regulator in lipid homeostasis. The PPARγ gene deficiency resulted in elevated plasma levels of triglycerides and NEFA [30]. The thiazolidinediones type PPARγ activators including troglitazone and pioglitazone improved the dyslipidemia by lowering the triglyceride levels in patients with dyslipidemia [31, 32]. In line with these observations, PPARβ/δ-null mice on a high-fat diet showed an increased rate of hepatic very-low-density lipoprotein production, and treatment of various animal models with selective PPARβ/δ agonists (GW0742 and L165041) yielded valuable data favoring PPARβ/δ as a therapeutic target for dyslipidemia [33]. Based on the above-mentioned evidences, it can be concluded that all the three PPAR subtypes have the lipid lowering properties mediated via different signal pathways. It may be possible that the lipid lowering effects of OA-NO2 share the lipid lowering properties of three PPAR subtypes, without reducing the food intake of animals. There were also the possibilities that the OA-NO2 reduced the lipids via PPARs independent pathways.

Besides the hyperlipidemia, the fatty liver also was present in the DOCA-salt hypertensive mice. The DOCA-salt treated rats showed fatty changes in hepatocytes besides hypertrophy and globular hyalinization, edema, and hydrophobic changes [9]. In the present study, a similar liver steatosis characterized with striking histological changes along with abnormal ALT was found. Pretreatment of OA-NO2 strikingly attenuated the liver injury and reduced the liver tissue triglycerides. The DOCA-salt induced hypertension status is known to be associated with oxidative stress resulting from an imbalance of antioxidant defense mechanisms in various tissues, including an early imbalance of liver antioxidant. Hepatic antioxidant defenses were decreased as early as 1 week of hypertensive treatment; the decrease of peroxidase, reductase, transferase, and catalase activities was associated with a significant increase of TBARS levels [34]. On the other hand, the high triglyceride levels can trigger liver oxidative stress after a long-term high-fat diet [35]. Generally, lipid and metabolic disorders are very likely to cause oxidant-antioxidant imbalances in the liver, where high levels of fatty acids provide the material basis for oxidative stress [36, 37]. Excessive levels of FFAs induced high levels of β-oxidation, and the production of ROS decreased antioxidant defenses at a mitochondrial respiratory chain level, simultaneously with the induction of steatosis [38]. Expressions of p47phox and gp91phox have been found to increase in obese rats and to be partly responsible for excessive oxidation [39]. Considering the hyperlipidemia and fatty liver in DOCA-salt induced hypertensive mice, the liver oxidative stress was accessed by examining liver TBARS levels and the two major NADPH oxidase subunits gp91phox and p47phox. The DOCA-salt hypertensive mice exhibited extensive liver oxidative stress, while OA-NO2 treatment improved the oxidative stress. The antioxidative stress effect of OA-NO2 is consistent with the previous study results in ischemia and reperfusion and endotoxemia mice model [11, 40].

In addition to the effect of OA-NO2 on obesity and obesity-related conditions [7], in the present study, it was demonstrated that OA-NO2 had the beneficial effect on the hypertension-related lipid metabolism. Hypertension is recognized globally as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, and renal diseases [41]. There is a strong association between hypertension and dyslipidemia. About 80% of hypertensive patients have comorbidities such as obesity, glucose intolerance, and lipid metabolism abnormalities. Several prospective studies have found that the hypertensive patients had higher serum total cholesterol and triglycerides compared to healthy normotensive controls [42]. It is meaningful that the OA-NO2 has the potential properties for improving the hypertension-related lipid metabolism and organ injury.

In summary, OA-NO2 is a newly identified endogenous product with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and has demonstrated a favorable safety profile in animal studies. The present study results demonstrated that the OA-NO2 restored the lipid metabolism and ameliorated the liver steatosis in DOCA-salt hypertensive mice. The results indicated the novel therapeutic potential of OA-NO2 in a rodent model of hypertension-related lipid metabolism.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81200530) (to Haiping Wang).

Conflict of Interests

All authors declare that they have no any conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Hermida Ameijeiras A., Lopez Paz J. E., Pena Seijo M., et al. Lipid profile in hypertensive patients treated with lipid lowering therapy. Journal of Hypertension. 2010;28:378–379. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000379372.41522.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarkar D., Latif S. A., Uddin M. M., et al. Studies on serum lipid profile in hypertensive patient. Mymensingh Medical Journal. 2007;16(1):70–76. doi: 10.3329/mmj.v16i1.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girard A., Madani S., El Boustani E. S., Belleville J., Prost J. Changes in lipid metabolism and antioxidant defense status in spontaneously hypertensive rats and Wistar rats fed a diet enriched with fructose and saturated fatty acids. Nutrition. 2005;21(2):240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakano A., Inoue N., Sato Y., et al. LOX-1 mediates vascular lipid retention under hypertensive state. Journal of Hypertension. 2010;28(6):1273–1280. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833835d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy D., Höke A., Zochodne D. W. Local expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in an animal model of neuropathic pain. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;260(3):207–209. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00982-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naureckiene S., Edris W., Ajit S. K., et al. Use of a murine cell line for identification of human nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2007;55(3):303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang T., Wang H., Liu H., Jia Z., Guan G. Effects of endogenous PPAR agonist nitro-oleic acid on metabolic syndrome in obese Zucker rats. PPAR Research. 2010;2010:7. doi: 10.1155/2010/601562.601562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangel-Frausto M. S., Pittet D., Costigan M., Hwang T., Davis C. S., Wenzel R. P. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): a prospective study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273(2):117–123. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520260039030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veeramani C., Al-Numair K. S., Chandramohan G., Alsaif M. A., Pugalendi K. V. Antihyperlipidemic effect of Melothria maderaspatana leaf extracts on DOCA-salt induced hypertensive rats. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2012;5(6):434–439. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lundberg J. O., Gladwin M. T., Ahluwalia A., et al. Nitrate and nitrite in biology, nutrition and therapeutics. Nature Chemical Biology. 2009;5(12):865–869. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H., Liu H., Jia Z., et al. Nitro-oleic acid protects against endotoxin-induced endotoxemia and multiorgan injury in mice. The American Journal of Physiology—Renal Physiology. 2010;298(3):F754–F762. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00439.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J., Villacorta L., Chang L., et al. Nitro-oleic acid inhibits angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circulation Research. 2010;107(4):540–548. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole M. P., Rudolph T. K., Khoo N. K., Bauer P. M. Nitro-fatty acid inhibition of neointima formation after endoluminal vessel injury. Circulation Research. 2009;105:965–972. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin S.-L., Chen Y.-M., Chiang W.-C., Wu K.-D., Tsai T.-J. Effect of pentoxifylline in addition to losartan on proteinuria and GFR in CKD: a 12-month randomized trial. The American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2008;52(3):464–474. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y., Jia Z., Liu S., et al. Combined losartan and nitro-oleic acid remarkably improves diabetic nephropathy in mice. American Journal of Physiology: Renal Physiology. 2013;305(11):F1555–F1562. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00157.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prahalathan P., Saravanakumar M., Raja B. The flavonoid morin restores blood pressure and lipid metabolism in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Redox Report. 2012;17(4):167–175. doi: 10.1179/1351000212Y.0000000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veeramani C., Al-Numair K. S., Chandramohan G., Alsaif M. A., Pugalendi K. V. Antihyperlipidemic effect of Melothria maderaspatana leaf extracts on DOCA-salt induced hypertensive rats. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2012;5(6):434–439. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu J., Gaetani S., Oveisi F., et al. Oleylethanolamide regulates feeding and body weight through activation of the nuclear receptor PPAR-α . Nature. 2003;425(6953):90–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terrazzino S., Berto F., Carbonare M. D., et al. Stearoylethanolamide exerts anorexic effects in mice via down-regulation of liver stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase-1 mRNA expression. The FASEB Journal. 2004;18(13):1580–1582. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1080fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Astarita G., Rourke B. C., Andersen J. B., et al. Postprandial increase of oleoylethanolamide mobilization in small intestine of the Burmese python (Python molurus) The American Journal of Physiology—Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2006;290(5):R1407–R1412. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00664.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allcock G. H., Hukkanen M., Polak J. M., Pollock J. S., Pollock D. M. Increased nitric oxide synthase-3 expression in kidneys of deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1999;10(11):2283–2289. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10112283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernández N., Torres S. H., de Sanctis J. B., Sosa A. Metabolic changes in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Research Communications in Molecular Pathology and Pharmacology. 2000;108(3-4):201–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Lange P., Lombardi A., Silvestri E., Goglia F., Lanni A., Moreno M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta: a conserved director of lipid homeostasis through regulation of the oxidative capacity of muscle. PPAR Research. 2008;2008:7. doi: 10.1155/2008/172676.172676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torra I. P., Chinetti G., Duval C., Fruchart J.-C., Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: from transcriptional control to clinical practice. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2001;12(3):245–254. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barish G. D., Narkar V. A., Evans R. M. PPARδ: a dagger in the heart of the metabolic syndrome. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(3):590–597. doi: 10.1172/JCI27955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barish G. D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and liver X receptors in atherosclerosis and immunity. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(3):690–694. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emilsson V., O'Dowd J., Wang S., et al. The effects of rexinoids and rosiglitazone on body weight and uncoupling protein isoform expression in the zucker fa/fa rat. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 2000;49(12):1610–1615. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.18692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akiyama T. E., Nicol C. J., Fievet C., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α regulates lipid homeostasis, but is not associated with obesity. Studies with congenic mouse lines. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(42):39088–39093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guan Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor family and its relationship to renal complications of the metabolic syndrome. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2004;15(11):2801–2815. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000139067.83419.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones J. R., Barrick C., Kim K.-A., et al. Deletion of PPARγ in adipose tissues of mice protects against high fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(17):6207–6212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306743102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komers R., Vrána A. Thiazolidinediones—tools for the research of metabolic syndrome X. Physiological Research. 1998;47(4):215–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lalloyer F., Vandewalle B., Percevault F., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α improves pancreatic adaptation to insulin resistance in obese mice and reduces lipotoxicity in human islets. Diabetes. 2006;55(6):1605–1613. doi: 10.2337/db06-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y.-X., Lee C.-H., Tiep S., et al. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor δ activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell. 2003;113(2):159–170. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elhaïmeur F., Nicod L., Courderot-Masuyer C., et al. Evolution of liver antioxidant status and iron implication during the development of deoxycorticosterone-saline hypertension in rats. Biological Trace Element Research. 2005;107(3):263–276. doi: 10.1385/BTER:107:3:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ganz M., Csak T., Szabo G. High fat diet feeding results in gender specific steatohepatitis and inflammasome activation. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;20:8525–8534. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fromenty B., Robin M. A., Igoudjil A., Mansouri A., Pessayre D. The ins and outs of mitochondrial dysfunction in NASH. Diabetes and Metabolism. 2004;30(2):121–138. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(07)70098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seki S., Kitada T., Yamada T., Sakaguchi H., Nakatani K., Wakasa K. In situ detection of lipid peroxidation and oxidative DNA damage in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Journal of Hepatology. 2002;37(1):56–62. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aronis A., Madar Z., Tirosh O. Mechanism underlying oxidative stress-mediated lipotoxicity: exposure of J774.2 macrophages to triacylglycerols facilitates mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production and cellular necrosis. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2005;38(9):1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dobrian A. D., Schriver S. D., Khraibi A. A., Prewitt R. L. Pioglitazone prevents hypertension and reduces oxidative stress in diet-induced obesity. Hypertension. 2004;43(1):48–56. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000103629.01745.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu H., Jia Z., Soodvilai S., et al. Nitro-oleic acid protects the mouse kidney from ischemia and reperfusion injury. American Journal of Physiology: Renal Physiology. 2008;295(4):F942–F949. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90236.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sana M. S., Sana N. K., Shaha R. K. Serum lipid profile of hypertensive patients in the northern region of Bangladesh. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 2006;14:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choudhury K. N., Mainuddin A., Wahiduzzaman M., Islam S. M. Serum lipid profile and its association with hypertension in Bangladesh. Journal of Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2014;30:327–332. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S61019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]