Consultation models are core to GP training. Current models provide an excellent basis for sharing the key elements needed for safe and effective consultations in a front-line, first-contact setting: where any problem can walk through the door, and where the consultation is an integral part of a therapeutic relationship. They support an all-rounder view of the generalist.

But the ‘expert generalist’ is more than an all-rounder: someone who knows a little bit about a lot of things, and is able to navigate a patient through multiple protocols and disease pathways.1 Rather, the distinct expertise of the generalist is in providing personalised illness care.1

We know from patients that individually-tailored care requires more than just good personal care; it requires good communication skills and empathy.2 It also needs personalised decision making;3 that is, the interpretive practice which goes beyond the application of guideline(s) to this individual, to the co-creation of a new, individualised explanation of illness experience. GPs have told us their training has not developed skills and/or confidence in individually-tailored decision making; in going beyond a protocol.4 Existing consultation models do not pay enough attention to the specific practice of individually-tailored decision making.

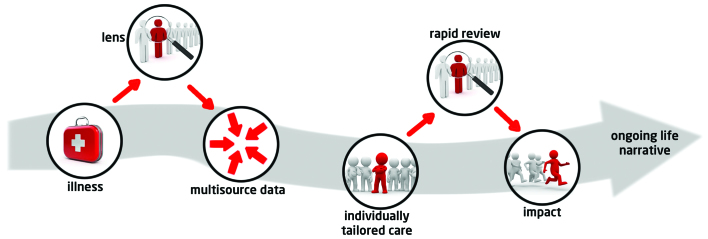

The School for Advancing Generalist Expertise (SAGE) is an international collaboration that aims to support the development and delivery of generalist solutions to complex problems. The group has previously described the principles underpinning interpretive generalist practice and how it differs from other approaches. We have been working with GPs to understand and address whole-system barriers and enablers to expert generalist practice (EGP).4 GPs have consistently identified extended consultation skills as one area of need.4 Colleagues have highlighted a need to translate described principles5 into a practical tool. In response, I have described the SAGE consultation model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The SAGE consultation model. © J Reeve 2015. Reproduced with permission.

THE SAGE MODEL

The model starts with a patient seeking help to deal with illness: a person experiencing a disruption6 (or potential disruption) to daily living that they believe to be a health-related issue or problem. To provide personalised illness care, the expert generalist must create a new individually-tailored understanding of the illness experience: an interpretation of what is wrong and what needs doing.5 There are five elements necessary for the robust construction of such new knowledge,5 which form the five steps of the SAGE consultation model:

the VIP lens;

multisource data;

individually-tailored care;

rapid review; and

impact review.

The VIP lens

To interpret something is to explain or provide meaning. The explanation we construct will depend on the position from which we view a problem, or an experience; as a medical problem or a disruption to daily living. The SAGE consultation focuses on the personal experience of illness. Its starting goal is therefore to understand the relative demands on, and resources available to, this individual; and particularly opportunities for modification in order to support a goal of sustaining and/or supporting daily living. Therefore, we start by looking for vulnerability to biographical disruption, VIP;7 an imbalance of resources and demands.

Multisource data

To make sense of an individual illness experience we draw on multiple sources of information,5 including scientific, patient, and professional understanding of illness and disease. All three are simply ‘data’; elements to go into the mixing pot from which we co-create an individualised account of illness. At this stage, the patients’ data (story) carries the same weight as the scientific data. The crucial difference in a generalist consultation is that we remove the hierarchy of knowledge that usually privileges scientific knowledge over others.5

Individually-tailored care

Thus, we weigh up all the data available to us to generate an interpretation about what is wrong and what needs doing. We use the data available to us, as viewed from the VIP lens, to co-create a new illness account for this individual: a personalised explanation of illness. We are not applying existing knowledge (for example, a guideline) to this patient. Rather we are creating new knowledge: an interpretation or explanation for this individual.

It is this interpretation which allows us to address the key decision described by Heath,8 namely whether it is in this person’s best interests to medicalise their illness experience.9 The expert generalist acts as a gatekeeper between illness and disease.8 This is in contrast to the approach in a protocolised model of care (as reinforced by the Quality Outcomes Framework) where the onus is on the health professional to justify exempting (exception reporting) an eligible patient from disease-focused care.9 We know from previous work that this change in emphasis results in different decision making, at least for some patients.8

Rapid review

Our interpretation and decision — generated through interaction with the patient — is unique to that individual patient. As such, it cannot be checked directly against a guideline or protocol.5 So we need an alternative approach to assessing the quality of the interpretation, and therefore the decision. Rapid review is the generalist-specific element of a wider concept of safety netting,10 asking does the decision provide a good interpretation of the individual’s illness experience?

Impact review

Within an interpretive scientific framework, we judge knowledge not only by how it is constructed but also by its impact. In this case, the extent to which it supports restoration or continuity of daily living and a reduction in illness.5 So we need feedback from individual patients, supported by continuity of care. But like other interpretive scholars, we need also to engage in critical peer review of our interpretation. Gabbay highlights the importance of collective generalist reflection in considering, constructing, and applying ‘beyond protocol’ decisions.11 Generalist practice requires us to protect and preserve opportunities for collective professional discussion and reflection.

DO WE REALLY NEED A NEW CONSULTATION MODEL?

Some people reading this may think there is nothing new here, and so challenge the need for a new model. But our research tells us that this work is needed. Patients tell us they are not getting individually-tailored care or personalised decisions about healthcare needs.2 Practitioners tell us that while individualised care is core to their professional philosophy, a number of barriers stop them doing this work in practice.4 Some have never developed the skills. Some don’t feel confident to use the skills they have, having no framework by which they can ‘defend’ their individualised interpretations ‘against’ the hierarchy of knowledge, that is protocols of condition-specific care.4 Clinicians have asked us whether it is ‘scientific’ to interpret.

Describing a clear model allows us to address some of these barriers. It means we can both teach those who don’t already have the necessary skills, and support those with existing skills to have the confidence to use them in practice.4 Crucially, it helps us to describe to non-practitioners (including managers and policy makers) how generalist practice is distinct from other ways of working, and why it matters.3 The failure to recognise and so value the expertise of the generalist has resulted in a ‘technical bypass’ of generalist decision making in the form of protocol driven care.3 Particularly for GPs working in European contexts where strong new public management creates organisational barriers to individualised care,5 a clear description of the model supports us in re-orienting healthcare systems to support this way of working.4

WHAT NEXT?

The model assumes a competence in the basics of consultation. It is not a replacement for, but an extension of the work described by Pendelton, Neighbour, and others. With colleagues from SAGE, I am now working with GPs, trainers, and trainees to develop a range of education resources. With the Society for Academic Primary Care and the Royal College of General Practitioners, we seek to ensure adequate attention is given to developing the skills of scholarship that underpin professional interpretive practice. Finally, we are actively engaged in research to formally evaluate the impact of this way of working.3 You can find out more about SAGE on our website (http://www.primarycarehub.org.uk/sage), and we would be delighted to hear from others interested in developing this work.

Funding

Joanne Reeve is funded by an NIHR Clinician Scientist Award to develop a body of work on generalist solutions to complex problems.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Additional information

A fuller version of this article, including an illustrative case history and schemata illustrating the SAGE model, is available from the author on request or at: http://www.primarycarehub.org.uk/sage/19-resources

REFERENCES

- 1.Reeve J, Irving G, Freeman G. Dismantling Lord Moran’s Ladder: the primary care expert generalist. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:34–35. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X660823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeve J, Lynch T, Lloyd-Williams M, Payne S. From personal challenge to technical fix: the risks of depersonalised care. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20(2):145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeve J, Blakeman T, Freeman GK, et al. Generalist solutions to complex problems: generating practice-based evidence — the example of managing multi-morbidity. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeve J, Dowrick C, Freeman G, et al. Examining the practice of generalist expertise: a qualitative study identifying constraints and solutions. JRSM Short Rep. 2013;4 doi: 10.1177/2042533313510155. 2042533313510155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeve J. Interpretive medicine: supporting generalism in a changing primary care world. Occas Pap R Coll Gen Pract. 2010;(88):1–20. v. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bury M. Illness narratives — fact or fiction. Sociol Health Illn. 2001;23(3):263–285. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeve J, Cooper L. Rethinking how we understand individual healthcare needs for people living with long-term conditions: a qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. 2014 doi: 10.1111/hsc.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heath I. Divided we fail. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2011. Harveian Oration 2011. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/harveian-oration-2011-web-navigable.pdf (accessed 17 Feb 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeve J, Bancroft R. Generalist solutions to overprescribing: a joint challenge for clinical and academic primary care. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2014;15(1):72–79. doi: 10.1017/S1463423612000576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neighbour R. The inner consultation. Lancaster: MTP press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabbay J, le May A. Practice based evidence for healthcare: clinical mindlines. Oxon: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]