Abstract

Background

In invertebrates, genes belonging to dynamically regulated functional categories appear to be less methylated than “housekeeping” genes, suggesting that DNA methylation may modulate gene expression plasticity. To date, however, experimental evidence to support this hypothesis across different natural habitats has been lacking.

Results

Gene expression profiles were generated from 30 pairs of genetically identical fragments of coral Acropora millepora reciprocally transplanted between distinct natural habitats for 3 months. Gene expression was analyzed in the context of normalized CpG content, a well-established signature of historical germline DNA methylation. Genes with weak methylation signatures were more likely to demonstrate differential expression based on both transplant environment and population of origin than genes with strong methylation signatures. Moreover, the magnitude of expression differences due to environment and population were greater for genes with weak methylation signatures.

Conclusions

Our results support a connection between differential germline methylation and gene expression flexibility across environments and populations. Studies of phylogenetically basal invertebrates such as corals will further elucidate the fundamental functional aspects of gene body methylation in Metazoa.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-1109) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acropora millepora, Coral, DNA methylation, Gene body methylation, Gene expression, Flexibility, Plasticity

Background

Phenotypic plasticity refers to the ability of an individual to adjust its phenotype in response to environmental cues [1]. Under changing environmental conditions, theory predicts that phenotypic plasticity may mitigate loss of fitness [2], and facilitate evolutionary adaptation [3, 4]. For sessile organisms such as plants and corals, plasticity is predicted to be of particular importance, as these organisms cannot migrate away from suboptimal environments [5, 6]. In the table top coral Acropora hyacinthus, colony fragments with previous exposure to elevated temperatures demonstrate increased bleaching resistance, suggesting an important role of plasticity in coral heat tolerance [7]. Hence predicting the future of reef-building corals and the ecosystems they support requires an understanding of their mechanisms of phenotypic plasticity. In most marine organisms, however, the molecular mechanisms that translate environmental stimuli into appropriate cellular responses are poorly understood [8]. One possible plasticity-modulating mechanism that is yet to be investigated in corals is DNA methylation [9–11].

DNA methylation is a widely conserved epigenetic modification involved in eukaryotic gene regulation [12]. In mammals, the majority (70-80%) of CG dinucleotides are methylated, with the exception of stretches of sequence rich in CG dinucleotides called CpG islands (CGIs) [13]. CGIs are generally not methylated, but can be targeted for methylation under particular conditions [14]. When methylation of CGIs occurs, its effect on transcription is based on the proximity of the CGI to a transcription start site (TSS), inhibiting initiation of transcription when near the TSS but not when far away from it [15]. There is evidence that this form of epigenetic regulation is involved in genome-environment interactions. DNA methylation is associated with persistent stress-induced gene expression in mice [16] and humans [17], as well as in plants [18]. It has also been linked with variation in disease development [19] and mediating phenotypic differences between monozygotic twins [20, 21].

In contrast to nearly ubiquitous methylation in mammalian genomes, genomic methylation in many invertebrates occurs specifically on CpG dinucleotides within gene bodies (also called transcription units) [22, 23]. Within gene bodies, methylation occurs primarily on exons rather than introns [24–26]. Density of gene body methylation is not equivalent across genes. Studies of multiple invertebrate taxa report bimodal patterns of gene body methylation, in which genes are separated into hypermethylated and hypomethylated classes [23, 27, 28]. Analyses of gene ontology (GO) terms in the context of these methylation classes have demonstrated characteristic divisions based on gene function. Basic biological functions with similar regulatory dynamics across tissue types and developmental stages tend toward strong methylation. Examples of basic biological functions include cellular metabolic processes, nucleic acid metabolism, and translation [28–30]. In contrast, functions that are dynamically regulated across tissues and developmental stages tend toward sparse methylation [31–33]. Examples of dynamically regulated functions include development, cell-cell signaling, and signal transduction [29, 30]. These findings suggest that bimodal gene body methylation may regulate flexibility of gene expression, with strongly methylated genes marked for stability and weakly methylated genes marked for flexibility. DNA methylation has also been linked with phenotypic plasticity, most strikingly in caste development in honeybees Apis mellifera, which is dependent on larval diet and activity of de novo DNA methyl-transferase (DNMT3) [34, 35]. Caste-specific genes in honeybees (i.e. genes with significant differential expression between queens and workers) are significantly biased toward weak methylation [31].

These findings have led to the hypothesis that invertebrate DNA methylation is involved in regulating environmentally driven gene expression and phenotypic plasticity [9, 11]. Among marine invertebrates, this hypothesis has yet to be validated in natural ecological contexts. In this study, we predicted that environmentally flexible gene expression in the branching coral Acropora millepora would be associated with signatures of weak gene body methylation. To test this prediction we analyzed gene expression profiles from clonal colony fragments reciprocally transplanted between distinct natural habitats. We show that elevated CpG content, a signature of historically weak germline methylation, is linked with environmentally driven gene expression. Our results suggest a potential role of DNA methylation in modulating the balance between stable gene expression required for homeostasis and flexible expression required for plasticity.

Results

Normalized CpG content of coding regions is bimodally distributed in A. millepora

Normalized CpG content (CpGO/E; see methods) is a well-established evolutionary signature of DNA methylation [23, 25, 28, 36]. We used this metric to estimate the strength of methylation of the coding regions of 15,221 genes across the A. millepora transcriptome. Because 5-methylcytosines are hypermutable [37], and invertebrate DNA methylation occurs specifically on CpG dinucleotides, sequences that are methylated in the germline are predicted to become CpG deficient over evolutionary time [38]. As a result, CpGO/E values are inversely related to the degree of historical germline methylation. Low CpGO/E values indicate strong methylation while high CpGO/E values indicate weak methylation. Importantly, CpGO/E has been shown to strongly correlate with direct measures of somatic DNA methylation in a number of animal models [23, 25, 28, 36].

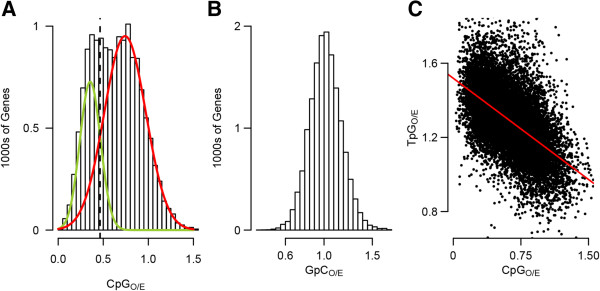

Using this metric, we found a characteristic bimodal pattern in which one set of genes is predicted to have strong germline methylation and a second is predicted to have weak germline methylation. For the distribution of CpGO/E values, a two-component mixture model provided substantially better fit than a single component model [Additional file 1] and as a consequence, we modeled the distribution with a two-component model (Figure 1A). We refer to the two components of the distribution as the low-CpGO/E and high-CpGO/E components. Means for the fitted component curves were estimated as 0.36 for the low-CpGO/E component and 0.74 for the high-CpGO/E component. Genes were assigned to either component based on the intersection of the fitted component curves at 0.46. Genes within the low-CpGO/E component are predicted to be strongly methylated and genes in the high-CpGO/E component are predicted to be weakly methylated. As a control, we showed that normalized content for GpC dinucleotides (which are not expected to be targeted for methylation) was unimodally distributed (Figure 1B). Also, as expected under the predicted mutational pattern for 5-methylcytosine (substitution for thymine as a result of deamination [37]), normalized TpG content showed an inverse linear relationship with CpGO/E (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Signatures of gene body methylation are bimodally distributed in the coral. (A) Distribution of genes based on normalized CpG content. The green curve indicates the low-CpG component (predicted to be strongly methylated). The red curve indicates the high-CpG component (predicted to be weakly methylated). The black dotted line separates the two components at the point of intersection between the curves. (B) Distribution of genes based normalized GpC content. In contrast to CpG dinucleotides, GpCs are not targeted for methylation so a normal distribution is expected. (C) Negative linear relationship between CpGO/E and TpGO/E. This is consistent with the prediction that DNA methylation causes depletion of CpG content largely though substitution of methylated cytosines for thymine.

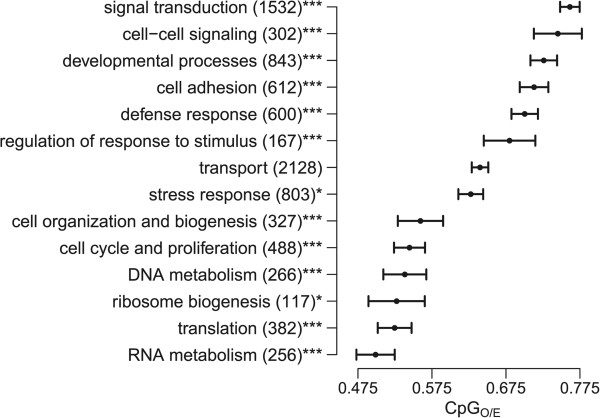

CpGO/E shows characteristic associations with different biological processes

To test for associations between CpGO/E and gene function, we sorted genes among different biological processes based on gene ontology (GO) annotations. Mean CpGO/E varied significantly between biological processes (ANOVA p < < 0.0001) and most processes were enriched in either the low or high-CpG component (Fisher’s exact test, Figure 2). Genes associated with RNA metabolism, translation, ribosome biogenesis, DNA metabolism, cell cycle and proliferation, and cellular organization and biogenesis tended toward low CpGO/E values, indicating strong germline methylation. Genes associated with signal transduction, cell-cell signaling, developmental processes, cell adhesion, defense response and regulation of response to stimulus tended toward high CpGO/E, indicating weak germline methylation. Genes associated with stress response showed intermediate mean CpGO/E but were enriched in the high-CpG component (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Variation of CpG O/E among genes assigned to different biological processes. Each bar represents mean CpGO/E for the indicated biological process and its standard error. Asterisks indicate significance of enrichment in the low- or high-CpG components (*< 0.05, **< 0.01, ***< 0.001; Fisher’s exact test).

High CpGO/E is linked with environmentally flexible gene expression

To investigate the relationship between environmentally induced gene expression and CpGO/E, we used DEseq [39] to compare gene expression between groups of clonal colony fragments reciprocally transplanted between two environmentally distinct natural habitats. Fifteen colonies were collected from each site and divided into two halves. One half of each colony was replaced in its native habitat, while the second half was transplanted to the alternate site (transplant location). In this way each genotype, represented by the two halves of the original colony, was exposed to both sites for a three-month study period. Following three months, global gene expression profiles were generated from all colony halves using tag-based RNA-seq method [40]. To detect effects of environment we compared gene expression between samples halves grouped by the transplantation site (the site they were placed at during the study period). In this way, the two groups being compared represented the same 30 genotypes exposed to two different environments for the three-month period. This allowed us to attribute systematic differences in gene expression between the two groups to environmental influences. To test the effect of population of origin we grouped the samples halves based on the site they originated from regardless of their transplant location during the study period. This allowed us to test for differences in gene expression that were distinctive of the two populations irrespective of environment. Expression data for each sample and estimates of differential expression between sample groups were uploaded through Zenodo at the following address [DOI] (http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12626) and will be available after June 1st 2015 or earlier. The read files have been uploaded the NCBI SRA (accession SRP049522) and will be released by November 11th 2015 or earlier.

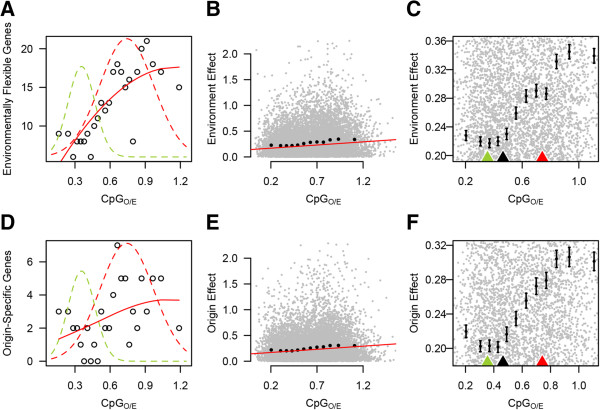

When sample halves were grouped based on transplantation site, 321 genes showed significant differential expression between the two groups (adjusted p < 0.01). We refer to this set of differentially expressed genes as ‘environmentally flexible genes’, since they are regulated depending on which site the sample halves were placed at. Environmentally flexible genes were significantly over-represented within the high-CpG component (Figure 3A and Table 1). Thus genes showing signatures of weak germline methylation were more likely to display environmentally driven variation in expression. To assess this relationship on a continuous scale we plotted CpGO/E against the magnitude of differential expression for each gene, calculated as [log(mean expression in environment A/mean expression in environment B)]. Differential expression was positively correlated with CpGO/E (Spearman's rank correlation; rho = 0.138; p < < 0.0001; Figure 3B). To examine if this was a simple linear relationship genes were divided into twelve quantiles based on CpGO/E and mean differential expression was plotted for each quantile. This analysis revealed that the magnitude of differential expression increased sharply within the high-CpGO/E component (Figure 3C), suggesting that differential expression correlates categorically with CpGO/E component rather than continuously with increasing CpGO/E.

Figure 3.

Genes with high CpG O/E are more likely to be differentially expressed between environments. (A) Frequency of environmentally flexible genes increases with CpGO/E. All genes with expression data were divided into 25 quantiles based on CpGO/E (503 genes per quantile). Each data point represents the count of environmentally flexible genes (adjusted P-value < 0.01) within a single quantile and the mean CpGO/E for the quantile. To illustrate associations with the CpGO/E components, the density component curves from figure 1A were traced over the count data. (B) Across all genes the magnitude of differential expression due to environment (environment effect) showed a positive relationship with CpGO/E. The red line indicates the linear model of the relationship between environmental effect and CpGO/E. Black error bars represent the mean and standard error for environmental effect of 12 quantiles based on CpGO/E. (C) Same as (B), rescaled to illustrate that mean environment effect increases sharply under the high-CpG component. Green and red arrows along the x-axis illustrate the means for each component curve. The black arrow indicates their point of intersection. (D-F) Same as A-C, but for the effect of coral origin rather than of transplant site.

Table 1.

Enrichment of differentially expressed genes in the high-CpG component

| Effect | Effect | Low-CpG | High-CpG | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off | Significant | Not significant | Significant | Not significant | ||

| Environment | 0.1 | 305 | 3994 | 667 | 7636 | 3.25E-02 |

| Environment | 0.05 | 185 | 4114 | 494 | 7809 | 4.77E-05 |

| Environment | 0.01 | 67 | 4232 | 254 | 8049 | 9.72E-08 |

| Environment | 0.001 | 25 | 4274 | 108 | 8195 | 6.65E-05 |

| Origin | 0.1 | 95 | 4204 | 264 | 8039 | 9.64E-04 |

| Origin | 0.05 | 46 | 4253 | 149 | 8154 | 8.74E-04 |

| Origin | 0.01 | 13 | 4286 | 55 | 8248 | 4.87E-03 |

| Origin | 0.001 | 0 | 4299 | 18 | 8285 | 5.44E-04 |

Effect Cut-off designates the α level used to designate significant differential expression due to transplantation site (environment). P column designates P-values for enrichment of environmentally flexible genes in the high-CpG were calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

Link between CpGO/E and population-specific gene expression

As differential expression due to transplantation site showed strong bias towards high CpGO/E, we performed the same analyses on differential expression with respect to sample origin. Here we compared gene expression between sample halves grouped based on their site of origin. We found 68 genes that maintained origin-specific expression patterns (adjusted p < 0.01) irrespective of transplantation site. Differential expression due to sample origin showed similar positive associations with CpGO/E (Figure 3 D-F; Table 1).

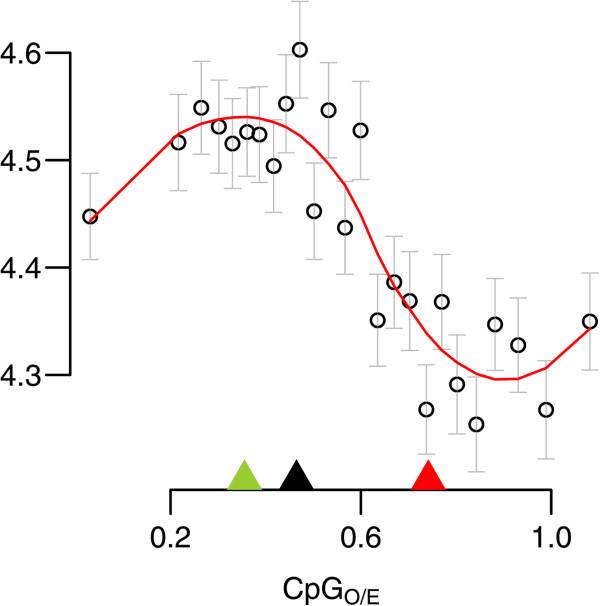

CpGO/E and gene expression level

To investigate broad scale relationships between the magnitude of gene expression and CpGO/E, we plotted mean transcript abundance (across all samples) for each gene against its CpGO/E value (Figure 4). Genes were divided into 25 equally sized quantiles based on CpGO/E. Mean transcript abundance varied significantly across CpGO/E quantiles (ANOVA p < < 0.0001) and genes in the high-CpGO/E component showed decreased mean expression compared genes in the low-CpGO/E component (Welch Two Sample t-test; p < < 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Correlation of CpG O/E with transcript abundance. Mean gene expression values were generated from 25 equally sized quantiles based on CpGO/E. Each gene was assigned an expression value equal to its average expression across all samples. Each data point represents mean of the expression values for all genes included in the quantile plotted against mean CpGO/E for the quantile; the whiskers denote standard errors. Green and red arrows indicate the means for the two mixture component shown in Figure 1A. The black arrow indicates the point of separation between the components.

Discussion

Bimodal patterns of gene body methylation as an ancestral feature among Metazoa

Depletion of CpG dinucleotides, a signature for historic germline DNA methylation, is widespread in A. millepora and follows a characteristic bimodal pattern. Notably, even for the high CpGO/E component, the mean CpGO/E value of 0.74 was less than 1.0, suggesting that these genes also bear signatures of germline methylation, although apparently weaker than genes in the low-CpGO/E component. As shown by Sarda et al. [28], bimodal methylation is consistent among diverse invertebrate taxa: reported in Hymenoptera [30, 31], Hemiptera [33], Lepidoptera [36], Orthoptera [27], Mollusca [29], and Cnidaria [23, 28], This study]. Evidence of bimodal methylation in Cnidaria (the sister group to all bilaterians) along with other diverse taxa suggests an ancient mechanism that has been conserved through more than 500 million of years of evolution [41].

Correlation between CpGO/Eand Gene Function in A. millepora

Consistent with previous findings among diverse invertebrates [28–31], we found significant variation in CpGO/E between different biological processes. The distribution follows a characteristic trend in which functions with spatial and temporal stability are enriched in the low-CpGO/E component, implying strong methylation. Functions with greater spatial and temporal variability are enriched in the high-CpGO/E component, implying weak methylation. Thus our results add to previous findings and suggest an association between weak gene body methylation and dynamic biological processes. In light of these results it was surprising that the GO term stress response showed an intermediate mean CpGO/E and only slight enrichment in the high-CpGO/E component (Figure 2). This contrasts with results from Gavery and Roberts [29], where stress response genes showed elevated CpGO/E. It is possible that the intermediate value for stress response in our system is related to regularity with which reef-building corals must contend with cellular stress. Unlike to other invertebrates examined for CpGO/E previously, scleractinian corals are host to photosynthetic endosymbionts (Symbiodinium spp.) [42]. While the coral host depends on endosymbionts for fixed carbon, their daily photosynthetic activity causes a hyperoxic cellular environment, so that host cells are regularly exposed to oxidative stress [43]. The relatively low mean CpGO/E for stress response in A. millepora could possibly reflect historical methylation of cellular stress response genes that require highly regular expression patterns to mediate chronic stresses of symbiosis. To support this, we compared mean CpGO/E of GO terms nested within stress response and found that oxidative stress, response to wounding, and cellular response to stress had the lowest mean CpGO/E values [see Additional file 2]. A recent comparison of gene expression in sea anemone (Aiptasia) revealed that along with response to oxidative stress, genes involved in Inflammation, tissue remodeling, and response to wounding, showed strong differential expression between symbiotic and asymbiotic individuals [44]. After removal of genes associated with response to oxidative stress and cellular response to stress, the remaining 426 stress response genes were substantially enriched in the high-CpGO/E component (Fisher’s exact test p < 0.001). These results suggest the interesting possibility that invertebrates possess taxon-specific methylation patterns based on the demands of their particular life histories.

Link between CpGO/E and gene expression plasticity

In insects, weakly methylated status is linked with variation in gene expression across tissue types [32], caste [31], and developmental stages [25], and a similar trend across tissues types been shown in oysters (Crassostrea gigas) [45]. However, whether the same association is found regarding variation in gene expression across different habitats remained unresolved. Here we show that in A. millepora, genes with high CpGO/E values are more likely to be differentially expressed in response to environmental conditions (Figure 3A and Table 1). High-CpGO/E genes also show greater magnitude of expression change in response to the environment (Figure 3B-C). To the extent that CpGO/E scores correlate with gene body methylation in somatic cells at the time of sampling, these results suggest a link between weak gene body methylation and gene expression plasticity.

Roberts and Gavery [11] proposed a role for gene body methylation in modulating plasticity in which weak gene body methylation passively facilitates flexible gene expression via alternative transcription start sites (TSSs), increased sequence mutations, exon skipping, or through transient gene methylation. Our results are consistent with the general hypothesis that weak gene body methylation facilitates environmentally responsive expression. To offer a potential mechanism, weak methylation could increase expression plasticity by allowing greater access to alternative TSSs. Among developmental genes in Drosophila melanogaster, alternative promoter use is quite common and can mediate temporally regulated expression [46]. In mammals, alternative promoter use is associated with tissue specific expression and can be regulated though methylation of intragenic CGIs [47]. Alternative TSSs could respond differently to regulatory elements and environmental cues, thereby permitting more complex and responsive transcriptional regulation. As proposed by Elango et al. [31], high CpGO/E genes also could be more amenable to epigenetic modulation. Here genes that are generally weakly methylated could be conditionally methylated to mediate environmentally responsive expression. This mechanism would be of particular interest if methylation patterns were shown to fluctuate in response to environmental cues. Because CpGO/E is an evolutionary signature reflecting historical methylation rather than the particular state at the time of sampling, this is a possibility that our approach could not address. An alternative hypothesis is that gene body methylation has little or no regulatory effects and is simply a byproduct of transcriptional patterns mediated by other mechanisms. Further experimentation will be required to resolve the potential explanations.

Link between CpGO/E and population-specific expression

We also identified genes with differential expression based on the corals’ origins. These genes showed expression patterns that were distinctive of the two populations and robust to changes in environmental conditions (i.e. expression differences between populations were maintained irrespective of transplant site). Our initial expectation was to find enrichment of low-CpGO/E genes among these stably expressed origin-specific genes; however, we found that these genes tended toward high CpGO/E similarly to the environmentally flexible genes (Figure 3D-E).

Since previous studies have demonstrated genetic structure between the Orpheus and Keppel populations [48], the simplest explanation of the origin-specific expression differences is that they result from genetic divergence. If this is the case, an intriguing possibility is that gene body methylation may help to stabilize expression patterns across divergent genetic backgrounds. Such buffering against genetic variation would be similar to the function of the heat shock protein 90 [49], except at the level of transcription rather than at the level of protein structure.

CpGO/E shows negative relationship with mean expression level

Although the difference was subtle, genes in the low-CpGO/E component (indicating strong germline methylation) showed higher average expression (Figure 4). This could be attributed to the ubiquitous expression of low-CpGO/E “housekeeping” genes, whereas the expression of many high-CpGO/E genes is restricted to certain cell types and thus might appear lower on the scale of the whole organism. It is also possible that gene body methylation lowers gene expression noise, as has been shown in human blood and brain tissue [50], potentially leading to less frequent “off” state and thus higher average expression of low-CpGO/E genes. A similar trend has been shown in the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) where transcriptional noise is negatively associated with protein abundance, and genes involved responding to the environment show elevated noise compared to genes involved in protein synthesis [51].

The link between predicted methylation and elevated expression contrasts with results from Riviere et al. [52], in which methylation of homeobox genes of oysters during development was inversely related to mRNA abundance. They suggest that in the case of these developmental genes a ‘CpG-island-like’ mechanism of gene repression could be responsible decreasing mRNA abundance. Hence it does not seem that gene body methylation leads to increased expression per se and the trend we describe is more likely due to enrichment with ubiquitously expressed housekeeping genes and not to a methylation-driven increase in expression of low-CpGO/E genes.

Corals as a model to study ecological roles of gene body methylation

Reef-building corals, as phylogenetically basal metazoans with a well-studied ecology and emerging genomic resources, represent an excellent study system to address the function of gene body methylation. Unlike most other animal models, corals can be fragmented into clonal replicates and transplanted across natural environments, making it possible to disentangle environmental and genotypic effects on genome-wide processes in realistic ecological contexts [53]. Corals can also be crossed in the lab to generate full-sib families of larvae and juveniles, which enables studies of how gene body methylation becomes established and facilitates quantitative genetic analysis [54]. Lastly, understanding the role of DNA methylation in phenotypic plasticity of corals has important conservation implications. Phenotypic plasticity is predicted to significantly influence evolutionary responses to climate change [55] and corals, the foundation of the most biologically diverse ecosystem in the ocean, are among the species most vulnerable to extinction [56].

Conclusions

Our results indicate a connection between historical germline methylation and gene expression flexibility across environments and populations. As a whole our results are consistent with a hypothesis that strong gene body methylation leads to more stable gene expression while weak methylation facilitates flexible expression, although the direction of causality remains to be confirmed. Studies of phylogenetically basal invertebrates such as corals will further elucidate the fundamental functional aspects of gene body methylation in Metazoa.

Methods

Genomic resources

Coding sequences were extracted from the A. millepora transcriptome [57] using the script CDS_extractor.pl which is part of the Matz lab’s transcriptome annotation bundle available on the Matz lab website at http://www.bio.utexas.edu/research/matz_lab/matzlab/Methods_files/transcriptomeAssemblyAnnotation.v.1.1.tgz and on GitHub (doi:10.5281/zenodo.12232). This script uses Blastx [58] results against a protein sequences database to identify open reading frames and extract them while correcting for occasional frame shifts. For the protein reference database we combined the proteomes of Nematostella vectensis [59] and Acropora digitifera [60]. Blastx against this database was performed with an evalue cutoff of 1e-4. Based on manual verifications of a subset of A. digitifera protein annotations, they were pre-filtered to include sequences longer than 60 amino acids with the annotation assigned based on the listed e-value = 1e-20 or better. Annotation of our coding sequences with GO terms was based on Blastx hits to the annotated Nematostella vectensis [59] and Acropora digitifera [60] proteomes as part of the annotation pipeline indicated above. All GO annotations associated with the best hit from these references were transferred to the query sequence in our dataset. GO annotations were further supplemented with GO terms based on BLASTx matches (e-value cutoff of 10-10) to the SwissProt Protein database [61]. Coding sequences with no annotations were excluded from the analysis. As gene length can influence the validity of CpGO/E as a predictor of methylation status [25], and DNA methylation tends to decrease toward the 3’ end of invertebrate gene bodies [23, 26], we controlled for differences in transcript length by examining CpG content only in the first 1 kb of the coding regions of each gene. Sequences shorter than 300 bp (2500 in total) were also excluded from the analysis. CpG values were bounded between 0.001 and 2, so that 1 gene with a value of 2.08 was excluded and 89 with values below 0.001 were excluded.

CpGO/E class assignment

To predict gene body methylation in A. millepora, we used normalized CpG content (CpGO/E) calculated as in Elango et al. [31].

Where PCpG, PC and PG are the frequencies of CpG dinucleotides, C nucleotides, and G nucleotides respectively. Because 5-methylcytosines are hypermutable [37], and invertebrate DNA methylation is targeted specifically to CpG dinucleotides, sequences that are methylated in the germline are predicted to become CpG deficient over evolutionary time [38]. As a result CpGO/E is inversely related to the degree of historical germline methylation. Low CpGO/E values indicate strong methylation while high CpGO/E values indicate weak methylation. This metric has been shown to correlate with direct measures of DNA methylation in a number of animal models [23, 25, 28, 36].

To test whether the distribution of CpGO/E values was best described as mixture of distributions we used the package Mclust [62] implemented in the R environment [63]. Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used to compare the likelihood of Gaussian Mixture Models with different numbers of components. We found that a two-component model provided substantially better fit than a single component model [see Additional file 1 for trace of BIC for different numbers of components]. The R package Mixtools [64] was used to fit and trace the two-component mixture model of the distribution. Following Hunt et al. [33], we used the point of intersection of the two component curves to separate genes into two components: the 'low-CpG component’ (predicted to be hypermethylated) and the ‘high-CpG component’ (predicted to be hypomethylated).

Analysis of CpGO/E for biological processes

To analyze patterns of gene function relative to predicted methylation, we assigned annotated genes to 14 general biological processes based on gene ontology (GO) terms. The GO terms were selected to match a subset of those analyzed by Gavery and Roberts [29]. To these we added four additional hand-picked GO terms: ribosome biogenesis, translation, defense response, and regulation of response to stimulus, to better demonstrate the spread of “house-keeping” versus dynamic biological processes. A single gene could be assigned to multiple GO terms. GO terms with fewer than 20 representative genes, including death (no annotated genes) and protein metabolism (11 genes), were excluded from the analysis. Nonrandom sorting of genes from each function between the high-CpGO/E and low-CpGO/E components was ascertained using Fisher’s exact test [65].

Reciprocal transplantation experiment

Field work was conducted with permission from the Great Barrier Reef marine Park Authority (Research permit G09/29894.1) To test for a relationship between environmentally induced gene expression and predicted methylation, we analyzed gene expression patterns of samples from a reciprocal transplantation experiment. Briefly, reciprocal transplantations were made between two environmentally distinct study sites (Keppel: 23°09S 150°54E and Orpheus 18°37S 146°29E) separated by 4.5 degrees of latitude in the Great Barrier Reef. On the 23rd April (Orpheus) and 4th May (Keppels) 2010 fifteen colonies were collected from wild populations from each site and divided into two. One half of each colony was replaced in its native habitat, while the second half was transplanted to the alternate study site. Samples from all coral fragments were collected at midday after three months (9th July 2010 at Orpheus, 14th July at Keppels) frozen in liquid nitrogen, then transferred into RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) for gene expression profiling.

Analysis of gene expression

The gene expression in 56 samples (four samples failed to produce gene expression profiles and were not included) from the reciprocal transplant experiment was profiled using tag-based RNA-seq library method [40]. The latest version of the protocol and bioinformatics pipeline are available at http://sourceforge.net/projects/tag-based-rnaseq/. Briefly, the method works by sequencing short fragments from the 3’ end of mature mRNA transcripts by priming off the poly-A tail during first stand cDNA synthesis. Transcript abundance is inferred through normalized fold coverage of reads mapped to the species transcriptome [57]. While the method is exceptionally cost effective it does not allow analysis of relative expression of different transcript isoforms. Sequencing was performed using the SOLiD system producing a total of 108499924 filter passing reads (average reads per sample = 1937499 ± 788474 standard deviation). The counts data were analyzed using generalized linear model implemented in DESeq package [39] with the factors “origin” and “transplant location”. The R script used to implement DESeq is available at [DOI] (https://zenodo.org/badge/doi/10.5281/zenodo.12626.png) (http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12626) and on GitHub at https://github.com/grovesdixon/CpGoe.git. False discovery rate was controlled at 1% [66]. Enrichment of differentially expressed genes (i.e., showing significant effect of transplant location or origin) in the high-CpGO/E component was tested using Fisher’s exact test [65]. To assess this association on a continuous scale, we plotted transplantation effect and origin effect estimated for each gene in DEseq against its CpGO/E. Effect size for transplantation was estimated as [log(mean expression of samples placed at Orpheus/mean expression samples placed at Keppel)], whereas the origin effect was estimated as [log(mean expression of samples that originated at Orpheus/mean expression samples that originated at Keppel)].

Plotting relationships between expression and CpGO/E

To visualize genome wide trends between differential gene expression and predicted methylation (Figure 3A,D) we plotted data from 25 equal-sized gene quantiles based on CpGO/E. The component curves from Figure 1A were overlaid to show the relative densities of the high- and low-CpG components. Vertical scaling of the component curves did not correspond to y-axis labels. To plot mean transcript abundance against CpGO/E (Figure 4), genes were divided into 25 equally sized quantiles based on CpGO/E values. For each gene, expression was averaged across all samples. Mean expression for all genes in each quantile was then plotted against the mean CpGO/E value for the quantile.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: Estimated fit for Gaussian Mixture Models. Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used to compare the fit of Gaussian Mixture Models with different numbers of components to the distribution of CpGO/E values. BIC indicated that multicomponent models were more likely than a single component model. For simplicity, and to facilitate comparisons with previous studies we chose a two-component model. (PDF 39 KB)

Additional file 2: Genes involved in response to oxidative stress and cellular response to stress contribute to the relatively low mean CpG O/E for the stress response Gene Ontology term. The figure illustrates the variation in CpGO/E of Gene Ontology (GO) terms nested within stress response. Each bar represents mean CpGO/E for the indicated GO term and its standard error. Asterisks indicate significance of enrichment in the low- or high-CpG components (*< 0.05, **< 0.01, ***< 0.001; Fisher’s test). The bar labelled ‘stress response reduced’ represents the stress response GO term with genes from response to oxidative stress and cellular response to stress removed. (PDF 59 KB)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Carly D. Kenkel for assistance with data analysis. Funding for this study was provided by National Science Foundation grant DEB-1054766 to MVM and the grant from the Australian Research Council Center of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies and the Queensland Government to LKB. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers who contributed valuable revisions and insights.

Abbreviations

- CGIs

CpG islands

- TSS

Transcription Start Site

- CpGO/E

Normalized CpG content, specifically the CpG observed to expected ratio

- GO

Gene ontology.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GBD carried out all the CpG-related data analysis and drafted the manuscript. LKB designed and conducted the field experiment, carried out RNA-seq sample preparation, and provided insights and revisions to the manuscript. MVM coordinated data analysis, analyzed RNA-seq data to infer differential gene expression and provided insights and revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Groves B Dixon, Email: grovesdixon@utexas.edu.

Line K Bay, Email: l.bay@aims.gov.au.

Mikhail V Matz, Email: matz@utexas.edu.

References

- 1.Kelly SA, Panhuis TM, Stoehr AM. Phenotypic plasticity: molecular mechanisms and adaptive significance. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:1417–1439. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chevin L, Collins S, Lefèvre F. Phenotypic plasticity and evolutionary demographic responses to climate change : taking theory out to the field. Funct Ecol. 2013;27:966–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02043.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price TD, Qvarnström A, Irwin DE. The role of phenotypic plasticity in driving genetic evolution. Proc R Soc London. 2003;270:1433–1440. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh PJ, Price TD. Adaptive phenotypic plasticity and the successful colonization of a novel environment. Am Nat. 2004;164:531–542. doi: 10.1086/423825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicotra AB, Atkin OK, Bonser SP, Davidson AM, Finnegan EJ, Mathesius U, Poot P, Purugganan MD, Richards CL, Valladares F, Van KM. Plant phenotypic plasticity in a changing climate. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:684–692. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barshis DJ, Ladner JT, Oliver TA, Seneca FO, Traylor-Knowles N, Palumbi SR. Genomic basis for coral resilience to climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1387–1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210224110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palumbi SR, Barshis DJ, Traylor-Knowles N, Bay RA. Science (80-) 2014. Mechanisms of Reef Coral Resistance to Future Climate Change. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aubin-Horth N, Renn S. Genomic reaction norms: using integrative biology to understand molecular mechanisms of phenotypic plasticity. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:3763–3780. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angers B, Castonguay E, Massicotte R. Environmentally induced phenotypes and DNA methylation: how to deal with unpredictable conditions until the next generation and after. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:1283–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bossdorf O, Arcuri D, Richards CL, Pigliucci M. Experimental alteration of DNA methylation affects the phenotypic plasticity of ecologically relevant traits in Arabidopsis thaliana. Evol Ecol. 2010;24:541–553. doi: 10.1007/s10682-010-9372-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts SB, Gavery MR. Is there a relationship between DNA methylation and phenotypic plasticity in invertebrates? Front Physiol. 2012;2:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richards EJ. Population epigenetics. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker KL. Methylated cytosine and the brain: a new base for neuroscience. Neuron. 2001;30:649–652. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet Suppl. 2003;33:245–254. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murgatroyd C, Patchev AV, Wu Y, Micale V, Bockmühl Y, Fischer D, Holsboer F, Wotjak CT, Almeida OFX, Spengler D. Dynamic DNA methylation programs persistent adverse effects of early-life stress. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1559–1566. doi: 10.1038/nn.2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heim C, Binder EB. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene-environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp Neurol. 2012;233:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W-S, Pan Y-J, Zhao X-Q, Dwivedi D, Zhu L-H, Ali J, Fu B-Y, Li Z-K. Drought-induced site-specific DNA methylation and its association with drought tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) J Exp Bot. 2011;62:1951–1960. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Portela A, Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javierre BM, Fernandez AF, Richter J, Al-Shahrour F, Martin-Subero JI, Rodriguez-Ubreva J, Berdasco M, Fraga MF, O’Hanlon TP, Rider LG, Jacinto FV, Lopez-Longo FJ, Dopazo J, Forn M, Peinado MA, Carreño L, Sawalha AH, Harley JB, Siebert R, Esteller M, Miller FW, Ballestar E. Changes in the pattern of DNA methylation associate with twin discordance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Genome Res. 2010;20:170–179. doi: 10.1101/gr.100289.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyake K, Yang C, Minakuchi Y, Ohori K, Soutome M, Hirasawa T, Kazuki Y, Adachi N, Suzuki S, Itoh M, Goto Y-I, Andoh T, Kurosawa H, Oshimura M, Sasaki M, Toyoda A, Kubota T. Comparison of genomic and epigenomic expression in monozygotic twins discordant for rett syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki MM, Kerr ARW, De SD, Bird A. CpG methylation is targeted to transcription units in an invertebrate genome. Genome Res. 2007;17:625–631. doi: 10.1101/gr.6163007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zemach A, McDaniel IE, Silva P, Zilberman D. Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of eukaryotic DNA methylation. Science. 2010;328:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1186366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyko F, Foret S, Kucharski R, Wolf S. PLoS Biol. 2011. The honey bee epigenomes: differential methylation of brain DNA in queens and workers. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Wheeler D, Avery A, Rago A, Choi J-H, Colbourne JK, Clark AG, Werren JH. Function and evolution of DNA methylation in Nasonia vitripennis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonasio R, Li Q, Lian J, Mutti N, Jin L, Zhao H, Zhang P, Wen P, Xiang H, Ding Y, Jin Z, Shen SS, Wang Z, Wang W, Wang J, Berger SL, Liebig J, Zhang G, Reinberg D. Genome-wide and caste-specific DNA methylomes of the ants camponotus floridanus and harpegnathos saltator. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1755–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falckenhayn C, Boerjan B, Raddatz G, Frohme M, Schoofs L, Lyko F. Characterization of genome methylation patterns in the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. J Exp Biol. 2013;216:1423–1429. doi: 10.1242/jeb.080754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarda S, Zeng J, Hunt B, Soojin V. The evolution of invertebrate gene body methylation. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1907–1916. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gavery M, Roberts S. DNA methylation patterns provide insight into epigenetic regulation in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) BMC Genomics. 2010;11:483. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park J, Peng Z, Zeng J, Elango N, Park T, Wheeler D, Werren JH, Yi SV. Comparative analyses of DNA methylation and sequence evolution using nasonia genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:3345–3354. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elango N, Hunt BG, Goodisman MAD, Yi SV. DNA methylation is widespread and associated with differential gene expression in castes of the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11206–11211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900301106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foret S, Kucharski R, Pittelkow Y, Lockett GA, Maleszka R. Epigenetic regulation of the honey bee transcriptome: unravelling the nature of methylated genes. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:472. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunt B, Brisson J. Functional conservation of DNA methylation in the pea aphid and the honeybee. Genome Biol Evol. 2010;2:719–728. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kucharski R, Maleszka J, Foret S, Maleszka R. Nutritional control of reproductive status in honeybees via DNA methylation. Science. 2008;319:1827–1830. doi: 10.1126/science.1153069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foret S, Kucharski R, Pellegrini M, Feng S, Jacobsen SE, Robinson GE, Maleszka R. DNA methylation dynamics, metabolic fluxes, gene splicing, and alternative phenotypes in honey bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4968–4973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202392109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiang H, Zhu J, Chen Q, Dai F, Li X, Li M, Zhang H, Zhang G, Li D, Dong Y, Zhao L, Lin Y, Cheng D, Yu J, Sun J, Zhou X, Ma K, He Y, Zhao Y, Guo S, Ye M, Guo G, Li Y, Li R, Zhang X, Ma L, Kristiansen K, Guo Q, Jiang J, Beck S, Xia Q, Wang W, Wang J. Single base-resolution methylome of the silkworm reveals a sparse epigenomic map. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:516–520. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sved J, Bird A. The expected equilibrium of the CpG dinucleotide in vertebrate genomes under a mutation model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4692–4696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flores KB, Amdam GV. Deciphering a methylome : what can we read into patterns of DNA methylation? J Exp Biol. 2011;214:3155–3163. doi: 10.1242/jeb.059741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer E, Aglyamova GV, Matz MV. Profiling gene expression responses of coral larvae (Acropora millepora) to elevated temperature and settlement inducers using a novel RNA-Seq procedure. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:3599–3616. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chapman J, Kirkness E, Simakov O, Hampson SE, Mitros T, Thomas W, Rattei T, Balasubramanian PG, Borman J, Busam D, Disbennett K, Pfannkoch C, Sumin N, Sutton GG, Viswanathan LD, Walenz B, Goodstein DM, Hellsten U, Kawashima T, Prochnik SE, Putnam NH, Shu S, Blumberg B, Dana CE, Gee L, Kibler DF, Law L, Lindgens D, Martines DE, Peng J, et al. The dynamic genome of Hydra. Nature. 2010;464:592–596. doi: 10.1038/nature08830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rocker M, Willis B, Bay L. Thermal stress-related gene expression in corals with different Symbiodinium types. Proc 12th Int Coral Reef Symp. 2012;9:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levy O, Kaniewska P, Alon S, Eisenberg E, Karako-Lampert S, Bay LK, Reef R, Rodriguez-Lanetty M, Miller DJ, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Complex diel cycles of gene expression in coral-algal symbiosis. Science. 2011;331(80):175. doi: 10.1126/science.1196419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehnert EM, Mouchka ME, Burriesci MS, Gallo ND, Schwarz JA, Pringle JR. Extensive differences in gene expression between symbiotic and aposymbiotic cnidarians. G3. 2014;4:277–295. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.009084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gavery MR, Roberts SB. Predominant intragenic methylation is associated with gene expression characteristics in a bivalve mollusc. Peer J. 2013;1:e215. doi: 10.7717/peerj.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Batut P, Dobin A, Plessy C, Carninci P, Gingeras TR. High-fidelity promoter profiling reveals widespread alternative promoter usage and transposon-driven developmental gene expression. Genome Res. 2013;23:169–180. doi: 10.1101/gr.139618.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maunakea AK, Nagarajan RP, Bilenky M, Ballinger TJ, Souza CD, Fouse SD, Johnson BE, Hong C, Nielsen C, Zhao Y, Turecki G, Delaney A, Varhol R, Thiessen N, Shchors K, Heine VM, Rowitch DH, Xing X, Fiore C, Schillebeeckx M, Jones SJM, Haussler D, Marra MA, Hirst M, Wang T, Costello JF. Conserved role of intragenic DNA methylation in regulating alternative promoters. Nature. 2010;466:253–257. doi: 10.1038/nature09165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Oppen MJH, Peplow LM, Kininmonth S, Berkelmans R. Historical and contemporary factors shape the population genetic structure of the broadcast spawning coral, Acropora millepora, on the Great Barrier Reef. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:4899–4914. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rohner N, Jarosz DF, Kowalko JE, Yoshizawa M, Jeffery WR, Borowsky RL, Lindquist S, Tabin CJ. Cryptic variation in morphological evolution: HSP90 as a capacitor for loss of eyes in cavefish. Science. 2013;342:1372–1375. doi: 10.1126/science.1240276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huh I, Zeng J, Park T, Yi SV. DNA methylation and transcriptional noise. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2013;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newman JRS, Ghaemmaghami S, Ihmels J, Breslow DK, Noble M, DeRisi JL, Weissman JS. Single-cell proteomic analysis of S. cerevisiae reveals the architecture of biological noise. Nature. 2006;441:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature04785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riviere G, Wu G-C, Fellous A, Goux D, Sourdaine P, Favrel P. DNA methylation is crucial for the early development in the Oyster C. gigas. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2013;15:739–753. doi: 10.1007/s10126-013-9523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kenkel CD, Meyer E, Matz MV. Gene expression under chronic heat stress in populations of the mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides) from different thermal environments. Mol Ecol. 2013;22:4322–4334. doi: 10.1111/mec.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer E, Davies S, Wang S, Willis B, Abrego D, Juenger T, Matz M. Genetic variation in responses to a settlement cue and elevated temperature in the reef-building coral Acropora millepora. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2009;392:81–92. doi: 10.3354/meps08208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reusch TBH. Evol Appl. 2013. Climate change in the oceans : evolutionary versus phenotypically plastic responses of marine animals and plants. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foden WB, Butchart SHM, Stuart SN, Vié J-C, Akçakaya HR, Angulo A, DeVantier LM, Gutsche A, Turak E, Cao L, Donner SD, Katariya V, Bernard R, Holland RA, Hughes AF, O’Hanlon SE, Garnett ST, Sekercioğlu CH, Mace GM. Identifying the world’s most climate change vulnerable species: a systematic trait-based assessment of all birds, amphibians and corals. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moya A, Huisman L, Ball EE, Hayward DC, Grasso LC, Chua CM, Woo HN, Gattuso J-P, Forêt S, Miller DJ. Whole transcriptome analysis of the coral Acropora millepora reveals complex responses to CO2-driven acidification during the initiation of calcification. Mol Ecol. 2012;21:2440–2454. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Putnam NH, Srivastava M, Hellsten U, Dirks B, Chapman J, Salamov A, Terry A, Shapiro H, Lindquist E, Kapitonov VV, Jurka J, Genikhovich G, Grigoriev IV, Lucas SM, Steele RE, Finnerty JR, Technau U, Martindale MQ, Rokhsar DS. Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organization. Science. 2007;317:86–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1139158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dunlap WC, Starcevic A, Baranasic D, Diminic J, Zucko J, Gacesa R, van Oppen MJ, Hranueli D, Cullum J, Long PF. KEGG orthology-based annotation of the predicted proteome of Acropora digitifera: ZoophyteBase - an open access and searchable database of a coral genome. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:509. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Consortium TU. Update on activities at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:43–47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fraley C, Raftery AE. Model-based methods of classification: using the mclust Software in Chemometrics. J Stat Softw. 2007;18:1–13. doi: 10.1360/jos180001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Team RC . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benaglia T, Chauveau D, Hunter DR, Young DS. Mixtools: An R Package for Analyzing Finite Mixture Models. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fisher RA. On the interpretation of χ2 from contingency tables, and the calculation of P. J R Stat Soc. 1922;85:87–94. doi: 10.2307/2340521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bejamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Estimated fit for Gaussian Mixture Models. Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used to compare the fit of Gaussian Mixture Models with different numbers of components to the distribution of CpGO/E values. BIC indicated that multicomponent models were more likely than a single component model. For simplicity, and to facilitate comparisons with previous studies we chose a two-component model. (PDF 39 KB)

Additional file 2: Genes involved in response to oxidative stress and cellular response to stress contribute to the relatively low mean CpG O/E for the stress response Gene Ontology term. The figure illustrates the variation in CpGO/E of Gene Ontology (GO) terms nested within stress response. Each bar represents mean CpGO/E for the indicated GO term and its standard error. Asterisks indicate significance of enrichment in the low- or high-CpG components (*< 0.05, **< 0.01, ***< 0.001; Fisher’s test). The bar labelled ‘stress response reduced’ represents the stress response GO term with genes from response to oxidative stress and cellular response to stress removed. (PDF 59 KB)