Abstract

Background: The school setting may be the optimal context for early screening of and intervention on child mental health problems, because of its large reach and intertwinement with various participants (child, teacher, parent, other community services). But this setting also exposes children to the risk of stigma, peer rejection and social exclusion. This systematic literature review investigates the efficacy of mental health interventions addressed to children and adolescents in school settings, and it evaluates which programs explicitly take into account social inclusion indicators. Method: Only randomized controlled trials conducted on clinical populations of students and carried out in school settings were selected: 27 studies overall. Most studies applied group Cognitive Behavioural Therapy or Interpersonal Psychotherapy. Results: Findings were suggestive of the effectiveness of school-based intervention programs in reducing symptoms of most mental disorders. Some evidence was found about the idea that effective studies on clinical populations may promote the social inclusion of children with an ongoing mental disorder and avoid the risk of being highly stigmatized.Conclusion: School programs are still needed that implement standardized models with verifiable and evidence-based practices involving the whole school community.

Keywords: Educational context, mental health, school

INTRODUCTION

Schools are considered the ideal setting for the implementation of mental health treatment interventions, for several reasons.

Since the vast majority of children attends school and spends a considerable amount of time in school, the school is not only a setting for the early detection of children at risk of mental health disorders, but it also creates numerous possibilities to target these children with early interventions. Furthermore, the school provides a complex, far-reachingnetwork of community, parents, teachers and peers who,when involved, have a large potential of influencing childdevelopment.

School-based screening or treatment programs for common mental disorders can raise complex issues as well. One often feared risk is the potential over-diagnosing of students with the risk of stigmatizing them with a life-long label, damaging their social interactions and peer acceptance. Indeed, stigma and discrimination behaviour towards mental health disorders have been observed in even the youngest school children [1, 2].

To avoid the risk of stigmatization, there is some agreement that school-based screening and intervention programsshould not merely address clinical or cognition-based problems, but also include experiential social activities, engage students' feelings and behaviour thus facilitating their interaction with others, and develop their social skills [3, 4]. Within the worldwide call to eliminate and prevent mental health stigma and its antecedents [5], programs aimed at facilitating integration of children with psychiatric problems in the community were developed and tested.

Social competence is an important aspect in youth development and can be defined as the ability to form and maintain positive relationships and pro-social styles of interaction, and the ability to read social situations and to interpret them correctly. The absence of pro-social strategies often leads to dislike by peers, hence social exclusion. For children with a mental disease, peer-rejection at school can prompt or exacerbate antisocial development, while acceptance by peers could buffer the effects of dysfunctional behaviors [6, 7]. Interventions effectiveness could therefore benefit from the inclusion of strategies that strengthen social competence and stimulate peer acceptance in the school setting and in the community [6, 8, 9], and vouch for a functional network and community.

To create efficient functional networks and communities, school-based mental health activity and intervention programs increasingly involve families and school personnel in treatment. There is some evidence that positive interaction of families and school staff helps to achieve an overall functional school climate. Providers and families who work collaboratively for a student are more likely to win the student’s collaboration, which can result in positive role modelling [10, 11]. Whole-school interventions have been emphasised recently. Sugai and Horner (2002) [12] described this system-based approach as a model that incorporates research-validated procedures and outcomes, consistent with international policies and guidelines about the best school practices. It also includes positive reinforcement and skill building approaches, prevents stress, and integrates all the elements of the school culture engaging students, teachers, administrators, and parents in practices.

Research and practices demonstrate that whole-school discipline programs, involving the school and its surrounding community as a unit of change, can be effective in reducing dysfunctional behaviours, preventing mental health problems, and contributing to a better students’ performance [12-16].

Educational achievement can materialize as academic success, and also in successful social relationships and integration at school. Engaging teachers into proactive and cooperative classroom management can produce positive environments that encourage and reinforce functional classroom behavior [4, 11, 17-19]. To reduce the risk for children with a mental illness to have poor performance and a stressful social experience at school, resulting in potential exacerbation of the mental illness, practices need to improve their everyday psychosocial functioning in both school and home settings, involving the pupil’s parents, teachers and community in school interventions [8].

OBJECTIVES

The main purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review of school-based treatments or programs focusing on the integration of students with psychiatric diagnosis in the classroom. The concept of Integration comprises social inclusion dimensions, social skills, the sense of belonging to a group, inclusion in the school network, and quality relationships with peers: this dimension was labelled as “ingroup” [20]. Its opposite, conceived as a dichotomous construct, could be constituted by discrimination, the presence of stigmas, peer dysfunctional relationships, social exclusion, social anxiety, and low participation in school and recreational activities. The effectiveness of the interventions will be evaluated, while social outcome or social skills will be assessed as well as possible indicators of social inclusion/exclusion variables. Given the low number of studies specifically aimed at integration, authors decided to review all the studies involving clinical populations of students, ensuring the overall effectiveness of the interventions and assessing social outcomes and their changes after treatments apart.

METHODS

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

As a requirement of the search criteria, all the selected studies were based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which is considered the gold standard methodology to assess a program’s effectiveness. More specifically, to be included studies had to involve a school-age (3-18 years old) clinical sample; they must have been carried out in school settings and verified through clinical, psycho-social, learning or academic skills outcomes. Only studies written in English and published from 2000 to 2014 were included. Primary and secondary prevention programs on at-risk populations chosen according to socio-demographic variables, and interventions focusing on addictions and substance abuse were excluded.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

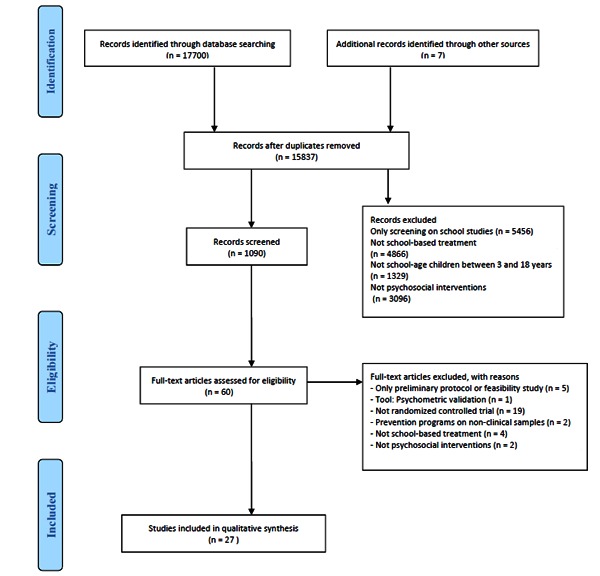

We searched PubMed, and the Google Scholar databases using the following key words: “mental health, educational context, school”; no additional filters were used. This initial search yielded 17,700 hits, while seven additional studies were retrieved by searching on included articles’ references or following indication by expert authors. Eventually, 1,090 abstracts written in English were examined to determine whether they met the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Overall sixty full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Out of these, five studies were excluded because they were preliminary protocol descriptions or feasibility studies; one study was a psychometric validation of a questionnaire; nineteen studies did not refer to a randomized controlled trial; two studies referred to prevention programs applied to non-clinical samples; four studies referred to treatment other than school-based; two studies were reports of pharmacological treatments and did not refer to a psychosocial intervention (Fig. (1): the flowchart according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, PRISMA).

Fig. (1).

Prisma flow diagram.

RESULT

General Description of Included Studies

Overall, 27 RCT papers met the inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis.

These school-based interventions differed among them in terms of the role played by teachers and parents in the treatment. In some studies, treatment was targeted at parents or teachers and the outcomes were measured on school children. In other studies, students, teachers and parents were equally involved in the treatment; other studies instead delivered treatment to pupils only. Presentation of results and interpretation of findings was divided in two parts: school-based programs that actively involved parents or teachers in the interventions, and interventions aimed at students only. The main outcomes that revealed a statistical significance were reported (see Table 1, 2). Table 3 describes more in detail the psychometric instruments used to test social variables of social inclusion and their variation in relation to the intervention.

Table 1.

Efficacy of school-based interventions on clinical samples targeting pupils with active participation of teachers and/or parents.

| Study | Country | Diagnosis | Type of program/FU |

Sample size and group |

Measures/outcome | Result | Social outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ostberg et al. 2012 |

Sweden | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) |

Parent and teacher manual-based group training Program 3-month T3 |

Children Treatment group TG (n=46) Children control group CG (n=46) 61 par./68 teachers Age m=10.95 |

ADHD Rating Scale ODD symptoms were measured by the eight DSM-IV criteria The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) |

(Assessed by parents and Teachers)

ADHD Rating Scale TG ↓ p <0.01 at T3 ODD symptoms TG ↓ p <0.05 at T3 SDQ TG ↓ p <0.05. at T3 Stronger efficacy assessed by parents |

SDQ : Peer relationship problems (5 items) Prosocial behaviour (5 items) |

| Sayal et al. 2010 |

United KingdomUni | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) |

Early school-based screening and educational intervention 5-year follow-up |

Children group book only TG (n=81) Children group identification only CI (n=114) Children group book and identification TGI (n=99) Children group no intervention CG (n=84) Age m=7.5 |

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) |

(Assessed by parents and Teachers)

SDQ « Stronger efficacy assessed by Teachers |

SDQ: Peer relationship problems (5 items) Prosocial behaviour (5 items) |

| Murray et al. 2011 |

United States | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | Teacher Management Practices for children with ADHD No follow-up |

Teachers (n=36) Children intervention group TG (n=46) Attention training control group CG (n=46) Age m=6.5 |

Teacher Management Questionnaire (TMQ) |

(Assessed by Teacher) TMQ subscales: Environmental modification TG ↑ p < 0.001 Behavior modification TG ↑ p < 0.05 Assignment modi-fication TG ↑ p <0 .001 Structure and organization « Instructional modifications « |

|

| Drugli et al. 2006 |

Norway |

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) |

Parent training combined with child therapy on positive discipline strategies, coping and social skills, conflict resolution, playing and cooperation with peers. 1-year follow-up |

Children parent training group PT (n=47) Children parent training and therapy group PT+CT (n=52) Waiting-list group WLC (n=28 families) Age m=6 |

Teacher Report Form (TRF) Preschool Behavior Questionnaire (PBQ) Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation (SCBE) The Wally Child Social Problem-Solving Detective Game (WALLY) Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS) |

(Assessed by parents and Teachers) TRF Aggression problems at post-treatment PT+CT vs PT ↓ p<0.05 PT+CT vs t WLC ↓ p<0.01 Aggression problems across post-treatment and follow-up PT+CT ↑ p<0.01 PBQ clinical level at post-treatment PT+CT ↓ p<0.05 clinical level at follow-up PT+CT ↑ p<0.05 WALLY social strategies at post-treatment PT+CT ↑ p<0.001 social strategies at follow-up PT ↑ p<0.05 SCBE « STRS « |

WALLY SCBE STRS |

| Drugli et al. 2007 |

Norway |

Conduct disorders (CD) Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) |

Parent training combined with child therapy on positive discipline strategies, coping and social skills, conflict resolution, playing and cooperation with peers. 1-year follow-up |

Children in parent training and therapy group PT+CT (n=52) Children in parent training group PT (control) (n= 47) Waiting-list group WLC (n=28) Age m=6 |

The Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) The Wally Child Social Problem-Solving Detective Game (WALLY) The Child Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Questionnaire (LSC) Social Competence and Behaviour Evaluation (SCBE) |

(Assessed by parents and Teachers) CBCL (father reports) from post-treatment and maintained across follow-up PT + CT ↑ p < 0.01 PT ↑ p < 0.05 CBCL (mother ratings) from post-treatment and maintained across follow-up PT + CT ↑ p < 0.05 WALLY Number of pro-social strategies used and maintained across follow-up PT+CT ↑p < 0.01 SCBE « LSC « |

CBCL Social competence WALLY LSC SCBE |

| Hand, et al. 2013 |

Ireland |

ID Intellectual Disability |

Evidence-based parenting programs based on social learning models No follow-up |

Treatment group participants TG (n = 16) Control group participants CG (n = 13) 42 parents Age m=9 |

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) The Parenting Stress Index (PSI) The Kansas Parent Satisfaction Scale (KPS) Parent identified personal and child-related goals. |

(Assessed by parents) SDQ: (Time × Group) Total difficulties subscales TG ↓ p<0.007 Conduct problems subscales TG ↓ p < 0.027 Hyperactivity « Emotional problems « Peer problems « Pro-social behaviour « Time factor Total difficulties TG ↓ p =0.003 Conduct problems TG ↓ p = 0.009 PSI stress Index (Time × Group) total score TG ↓ p <0. 01 Total TG ↓ p< 0.01). (Time factor) PSI Total score TG ↓ p < 0.001 Parent Distress TG ↓ p= 0.002 Parent–child relationship difficulties TG ↓p= 0.004 Difficult child measure « KPS Satisfaction Scale « Parent defined child-related goals (Time × Group) child-related goals TG↑ p < 0.001. (Time effect) TG v sCG ↑ p < 0.001 |

SDQ : Peer relationship problems (5 items) Prosocial behaviour (5 items) |

| Jorm, et al. 2010 |

Australia |

Mental disorders (Depression,Anxiety

Psychosis, Behavioural disorders |

Teachers educational programs on common mental disorders in Adolescents and student welfare 6 months follow-up |

Teachers Intervention group TIG (n=221) Teachers Control group TCG (n=106) Students in intervention group SIG (n= 982) Students Control group SCG (n= 651) Age m=9 |

Teacher outcomes: mental health knowledge Personal stigma items: % strongly disagree Perceived stigma items: % ≥ agree Help given towards students: % ≥ occasionally Confidence in helping students and staff with mental health problems % ≥ quite a bit School policies on student mental health Interacting with colleagues: % ≥ occasionally Seeking Additional Mental health information: % ≥ occasionally Teacher mental health Student outcome: Mental health knowledge Beliefs and intentions about where to seek help for depression Personal stigma: % strongly disagree Perceived stigma: % ≥ agree Help received from teacher Student Mental Health |

(Assessed by Clinicians)

(Teacher) knowledge TIG ↑ p <0.001 and maintained at follow-up P < 0.001. Perceived stigma (OR) TIG ↑ p = 0.031 and maintained at follow -up See other people as reluctant to disclose TIG ↑ p= 0.041 and maintained at follow -up Intentions towards helping students (OR) Teachers more likely to discuss their concerns with another teacher TIG ↑ p = 0.013 and maintained at follow -up Discuss their concerns with a counsellor (OR) TIG ↑ p = 0.023 and maintained at follow -up Have a conversation with the student (OR) TIG ↑ p = 0.162 and maintained at follow -up School policy of mental health (OR) TIG ↑ p=0.019 and maintained at follow -up Policy had been implemented in the previous month (OR) TIG ↑ p= 0.070 and maintained at follow-up (Student) Mental health knowledge Report that they received information about mental health problems SIG ↑ P < 0.001 Beliefs and intentions about where to seek help for depression (Student outcome) « Personal stigma: % strongly disagree (Student outcome) « Perceived stigma: % ≥ agree Stigma perceived in others (OR) SIG ↑ p= 0.006. Help received from teacher « Student Mental Health « |

Students Personal Stigma Items: % Strongly Disagree Perceived Stigma Items: % ≥ Agree Teachers Personal Stigma: % Strongly Disagree Perceived Stigma: % ≥ Agree |

| Mifsud,

et al. 2005 |

Australia | Anxiety | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Treatment groups (8-10 children) with parents collaboration 4-Month Follow-up |

Treatment group TG (n= 92) Active intervention waitlist control CG (num not reported) Age m=9.5 |

Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale (CATS) Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale-Parent Version (SCAS-P) (Sec.) Child Behavior Checklist-(CBCL) Teacher Rep. |

(Assessed by Clinicians) SCAS TG ↓ p < 0.005 and maintained at follow-up CATS TG ↓ p = .001 and maintained at follow-up SCAS-P↔ CBCL ↔ |

SCAS: sub-scale s Social phobia CATS: (9 items) CBCL: Social problems |

| Masia et al. 2005 |

United States | Anxiety | Skills training intervention on adolescents and participation of parents and teachers on psychoeducation groups 9-month follow-up |

Intervention group (SASS) TG ( n=21) Control group WL (n=17) Age m=14.8 |

Self-Report Inventories (ADIS-PC) Severity Social Phobic Disorders Severity and Change Form (SPDSCF) Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale for Children and Adolescents (LSAS-CA) Children’s Global Assessment Scale(CGAS) Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children (SPAI-C) Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A) Self-Report Inventories Loneliness Scale Parent Report: Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-AP) |

(Assessed by Clinicians)

ADIS-PC Severity (Group × Time) TG ↓ p < .0001 SPDSCF (Group × Time) TG ↓ p < .0001 LSAS-CA (Group × Time) Total score, TG ↓ p = .03, Total Avoidance subscale TG ↓ p = .03, Social Avoidance subscale TG ↓ p = .04. Performance Anxiety TG ↓ , p = .053 Total Anxiety TG ↓ p = .056. CGAS (Group × Time interaction) TG ↑ p < .0001 SPAI-C Social phobia symptoms TG ↓ p = .052. SAS-A(significance was found in one subscale out of three) (Group × Time effect) social anxiety in new situations TG ↓ p = .03. SAS-AP(parent reports) Social anxiety in new situations TG ↓ p = .02. FNE ↔ SAD-General subscales. ↔ (CDI) ↔ (interpersonal Problems) |

SPDSCF LSAS-CA SPAI-C SAS-A (AP) CDI: (interpersonal Problems) Self-Report Inventories Loneliness Scale ADIS-PC: social phobia items C-GAS: Children's global assessment scale (the area of interaction with with friends) |

| Bernstein, et al. 2005 |

United States | Anxiety | Group cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for children Group

6-month follow-up. |

Treatment group CBT for children TG (n = 17), Treatment group CBT for children plus parent training TPP (n = 20), No-treatment control group (n = 24). Age m=9.0 |

Child and Parent Interview Schedules (ADIS) Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC-C) Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Services Questionnaire (developed for use in this study) |

(Assessed byParentand Clinicians) ADIS

Composite CSR TG+TPP ↑ p= .03 TPP ↑ p= .06 Child-Interview TG+TPP ↑ p = .045 CGI TG+TPP ↑ p = .06 TPP ↑ p= .02). MASC (group × time) TG+TPP ↑ p= .006 SCARED(group × time) TG+TPP↓ p= .001 MASCTotal TPP ↑p= .02. SCARED indic. TPP ↑ p= .000. |

ADIS: social phobia items MASC: The Social Anxiety scale Humiliation/Rejection subscale |

Table 2.

Efficacy of school-based interventions on clinical samples targeting pupils only.

| Study | Country | Diagnosis | Type of program/FU | Sample size And group |

Measures/outcome | Result | Social outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hong, etal.2011 |

China |

Behavioral problems | Child Cognitive-behavioral intervention 6-month follow Up |

Treatment group TG (n = 208) Control group CG (n = 209) Age m=8 |

Child Behavior Checklist. (CBCL) Total Behavior Problem Scores |

(Assessed by Parents)

CBCL

Total behavior problem scores TG ↓ p = .024 TG ↓ p = .001 at 6-month follow up The levels of reported total behavior problems declined in response to the intervention and remained lower than those in the control group 6 months later |

CBCL: Social problem scale |

| Leff, et al.2009 |

United States | CD (Conduct problems) |

Culturally-adapted social problem solving/social skills

intervention No follow-up |

Intervention group TG (n = 21) Control Group CG (n = 11) Age m=12 |

The Children’s Social Behavior

Questionnaire (CSB) Measure of Hostile Attributional Bias (HAB) with cartoon-based version Asher and Wheeler Loneliness Scale Children’s Depression Inventory (ALS) |

(Assessed by Peer, Teachers and Clinicians)

CSB Teacher reports of relational aggression TG ↓ (moderate to large effect size of .74, Cohen, 1988) Teacher ratings of peer likeability TG ↑( very large effect size of 1.73, Cohen, 1988) HAB TG ↓ (very large effect size of .61, Cohen, 1988) ALS TG ↓ (moderate effect size of .45. Cohen, 1988 |

Peer nomination survey: relational aggression, physical aggression, peer liking hostile Attributions ALS CSB |

| Owens et al.2005 | United States |

ADHD Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ODD Oppositional defiant disorder CD Conduct problems DBD Disruptive Behavior Disorders |

Behavioral treatment intervention 9 months follow-up |

Treatment group TG (n= 30) Waitlist Control group CG (n= 12) Age m=8.5 |

Disruptive Behavior Disorders Structured Interview (DBD) Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) Impairment Rating Scale (IRS) |

(Assessed by Parents and Teachers)

DBD Rating Scale,

severity of hyperactivity and impulsivity TG ↓ p < .05 oppositional defiant behaviour TG ↓ p < .05 impairment in their peer relationships TG ↓ p < .05 CBCL, aggressive symptomatology TG ↓ p < .10, externalizing behavior problems TG ↓ p < .05 CD symptoms TG ↓ p < .10 total behavior problems TG ↓ p < .10 |

DBD (peer relationships) IRS: Peers relation Sibling relation Parental relation CBCL: ratings Social |

| Cooper, etal. 2010 |

United Kingdom |

Emotional distress | School-based humanistic counselling intervention no follow-up |

Counselling group TG (n= 13) Waiting list group WL (n=14) Age m=14 |

The Self-Report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (The emotional symptoms subscale of the SDQ) |

(Assessed by Clinicians)

SDQ-ES ↔ |

SDQ-PS: prosocial subscale Secondary outcome: The Social Inclusion Questionnaire' (SIQ) |

| Mufson, et al.

2004 |

Unites States |

Depression/Anxiety |

Interpersonal psychotherapy intervention 16 week follow-up |

Treatment group IPT-A, TG (n=34) Treatment as usual TAU, CG (n=29) Age m=15.1 |

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

(HAMD) Children's global assessment scale (C-GAS ) Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Social adjustment scale-self report (SAS-SR) |

(Assessed by Clinicians)

HAMD TG ↓ p=.04 and maintained at follow-up C-GAS TG ↑p=.04 (C-GAS trend to improvement at 16 weeks, p=0.06) CGI Global functioning TG ↑p=0.03 mean CGI scores (improvement) TG ↑p=0.03 At 16 weeks slight effect size in global functioning 0.51 (95% CI 0.003 to 1.02) SAS-SR social functioning mean TG ↑p=0.01 |

C-GAS: (interaction with friends) SAS-SR: social adjustment scale-self report |

| O'Leary-Barrett, et al.2013 | United Kingdom |

Depression, Anxiety, Conduct disorders |

Cognitive behavioral therapy intervention 2 years follow-up |

Treatment group TG ( n=694) Control group CG (n=516) Age m=13.5 |

The Substance Use Risk Profile Scale (SURPS) Brief symptoms Inventory (BSI) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (conduct subscale) |

(Assessed by Clinicians) SURPS « BSI depressive symptoms TG ↓ p<.05 (over two years) Suicidal ideation TG ↓ p<.02 (over two years) Anxiety symptoms TG ↓ p<.01 (over two years) Panic attacks « SDQ (conduct subscale) TG ↓ p=.01 (over two years) |

|

| Stallard et al.2012 | United kingdom |

Depression | Cognitive behavioural therapy 12 months follow-up |

Usual school inter-personal, social, and health education (PSHE) UG (n=298) Classroom based CBT group TG ( n=392) Attention control group CG (n=374) Age m=14 |

Short mood and feelings questionnaire (SMFQ) |

(Assessed by Clinicians) SMFQ« |

Secondary out.: Rev. child anx. and dep. Scale (RCADS) Social fobia scale |

| Stallard, et al.2013 | United kingdom |

Depression | Classroom based cognitive behavioural therapy 12 months follow up |

Usual school provision group UG (n=190) Attention control personal, social, and health education Interventions PSHE group CG (n= 179) Classroom-based CBT group TG (n=344) Age m=14 |

Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) Cost-effectiveness: incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions score (EQ-5D) |

(Assessed by Clinicians) SMFQ « ICERs Costs of interventions per child £41.96 for classroom-based CBT; £34.45 for attention control PSHE. Fieller's method was used to obtain a parametric estimate of the 95% CI for the ICERs and construct the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, confirming that classroom-based CBT was not cost-effective in the case of controls. EQ-5D « |

Secondary outcomes: Revised child anx. and dep.scale (RCADS) School Connectedness subscale. CATS Social phobia subscale |

| s et al.2010 |

United States | Depression | Classroom based cognitive behavioural therapy 12 months follow-up |

Cognitive behavioural therapy group TG (n=78), Contrast treatment at usual CG (n=70) Age m=9,5 |

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) |

(Assessed by Clinicians) MASC anxious symptoms TG and in CG ↓ P<.001 CDI depressive symptoms TG and in CG ↓ P<.001 |

MASC: The Social Anxiety scale Humiliation / Rejection subscale CDI: Interpersonal Problems Subscale |

| Gunlicks etal.2010 |

United States | Depression | Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents week 12 follow-up |

Interpersonal Psychotherapy group (IPT-A) TG (n=31) Treatment as usual group (TAU) CG (n=32) Age m=15 |

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ-20) CBQ_Mother Social Adjustment Scale - Self-report (SAS-SR): |

(Assessed by Clinicians) HRSD(at week 12) TG ↓ p < .05 CBQ-20 ↔ SAS-SR ↔ |

SAS-SR Sub-scale: Friends, School,Family, Dating CBQ-20 |

| Rose et al2014 |

Australia | Depression | Manualized cognitive behavior Therapy and Interpersonal Psychotherapy group program (RAP) Manualized group Program basic social skills (PIR) 12-month follow-up |

CBT and Interpersonal Psychotherapy (RAP) TG1 (n=31) Placebo, exercises therapeutically inactive CG ( n=31) Social skills treatment group TG2 (PIR) (n=31) Age m=13.5 |

Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale Second Edition (RADS–2). Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychological Sense of School Membership (PSSM) Clinical Assessment of Interpersonal Relations (CAIR) Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS) Clinician-administered, semistr. Interv.(DISCAP) |

(Assessed by Clinicians)

RADS–2 ↔ (TG1) TG2 ↓ p =.008 (no at follow-up) CDI ↔(TG1) TG2 ↓ p =.026 (not at follow-up) PSSM school connectedness TG2 ↑ p= .061) (not at follow-up) ↔(TG1) But no difference on follow-up between TG1 and TG2 MSLSS TG2 ↑ p = .061 CAIR ↔ DISCAP↔ |

PSSM CAIR CDI: Subscale interpersonal Problems |

| Tze-Chun Tang et al.2009 |

Taiwan | Depression | Interpersonal psychotherapy Intervention

(IPT-A) no follow-up |

Intensive interpersonal psychotherapy

TG (n=35) Treatment as usual (psychoeducation) (TAU) CG (n=328) Age m=15 |

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) Beck Scale for Suicide (BSS) |

(Assessed by Clinicians)

BAI TG ↓ p < 0.05 BDI TG ↓ p< 0.001 BHS TG ↓ p < 0.01 BSS TG ↓ p < 0.01 |

|

| Chemtob et al. 2002 |

Hawaii | PTSD post traumatic stress disorders |

School-based screening and psychosocial treatment 1 year follow-up |

Group treatment

TG (n=124) Individual treatment CG (n=124) Age m=8.47 |

Kauai Recovery Inventory

(KRI) Child PTSD Reaction Index (CPTS-RI) |

(Assessed by Clinicians)

KRI TG ↑ p<.001 (maintained at follow-up) CPTS-RI TG ↓ p=.01 |

|

| Stein, etal.2003 |

United States |

PTSD

post traumatic stress disorders |

Child Cognitive-behavioral program |

Treatment

group TG (n=61) Control Group CG (n=65) (Age m=11) |

Child Ptsd Symptom Scale (CPSS) Child Depression Inventory (CDI) Parents report Psychosocial dysfunction Teacher-Child Rating Scale (TCRS) |

(Assessed by Clinicians, Parents and Teachers)

CPSS

TG ↓ p < 0.05 CDI TG ↓ p < 0.05 Parents report Psychosocial dysfunction TG ↓ p < 0.05 TCRS ↔ |

CPSS:

item relationships with friends and item relationships with family

CDI: Subscale interpersonal Problems Parents report Psychosocial dysfunction |

| Tol WA, et al.2010 | Sri Lanka | PTSD post traumatic stress disorders |

Manualized intervention of cognitive behavioral Techniques and creative expressive elements 3-month follow-up |

Treatment Group TG (n=199) Waitlist group CG (n=200) Age m=11.03 |

Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS) Depression Self-Rating (DSRS) Screen for Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED-5) |

(Assessed by Clinicians ) PTSD ↔ DSRS ↔ SCARED-5 ↔ |

Secondary outcome: SDQ: Prosocial subscale |

| Kataoka et al.2011 |

United States |

PTSD post traumatic stress disorders |

Cognitive behavioral therapy skills intervention in a group format (5–8 students/group) |

Treatment Group TG (n=61) Waitlist group CG (n=62) Age m=11 |

Academic performance (math and language arts) grades were extracted from school records and coded as A=4, B=3, C=2, D=1, and F=0 for use as an outcome variable |

(Assessed by Teachers)

Math grade TG ↑ p=0.048)

Language Arts ↔ |

|

| Galla et al.2011 |

United States |

Anxiety | Modular Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Treatment 1-year follow-up |

Treatment group TG (n=14)

Control group CG (n=10) Age m=8.51, |

Child and Parent Versions (ADIS-C/P)

The Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale (CGI-I) Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC-C) |

(Assessed by Clinicians and Teachers)

Follow-up data have been only reported TG ADIS-IV TG↓ p = .000 MASC-P TG↓ p = .006 MASC-C TG↓ p = .000 CGI ↔ |

MASC: The Social Anxiety scale Humiliation / Rejection subscale |

↔ no statistical significance was found.

↑ a statistically significant increase was found

↓a statistically significant decrease was found

Table 3.

Social outcome as possible indicator of social inclusion.

| Study | Social Measure | Construct | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostberg et al. (2012) | The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) social sub-scale |

SDQ Assess children pro-social skills and quality of peer relations |

No separate presentation of data |

| Murray et al. (2011) | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Drugli etal. (2006) | Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation (SCBE) The Wally Child Social Problem-Solving Detective Game (WALLY) Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS) |

SCBE: Assess social competence, affective expression and adjustment difficulties in the child Wally: Assess problem-solving ability in hypothetical social problem situations STRS: Assess teacher perceptions of their relationships with a particular child |

WALLY social strategies at post-treatment PT+CT (composite group) ↑ p<0.001 social strategies at follow-up PT ↑ p<0.05 SCBE ↔ STRS ↔ |

| Drugli et al. (2007) |

The Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) The Wally Child Social Problem-Solving Detective Game (WALLY) The Child Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Questionnaire (LSC) Social Competence and Behaviour Evaluation (SCBE) |

CBCL Assess prosocial and antisocial behaviour (subscales) Wally Assess problem-solving ability in hypothetical social problem situations LSC Assess children’s feelings of loneliness, appraisal and peer relationships, perceptions of the degree to which important relationship needs are met, and perceptions of their own social competence. SCBE Assess patterns of social competence (isolated–integrated aspects in peer interactions), affective expression, and adjustments difficulties in children |

CBCL (father reports) from post-treatment and maintained across follow-up PT + CT (composite group) ↑ p < 0.01 PT ↑ p < 0.05 CBCL (mother ratings) from post-treatment and maintained across follow-up PT + CT (composite group) ↑ p < 0.05 WALLY Number of pro-social strategies used and maintained across follow-up PT+CT (composite group) ↑p < 0.01 SCBE ↔ LSC ↔ |

| Hand et al. (2013) | The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) |

SDQ Assess children pro-social skills and quality of peer relations |

No statistical significance was found |

| Jorm et al. (2010) | Student/Teachers Personal Stigma Items: % (Strongly Disagree) Perceived Stigma Items: % (Agree) |

Student/Teachers Personal Stigma and Stigma perceived |

Students

Stigma perceived in others

Perception that others believe in unpredictability

TG ↑ p = 0.006 Teachers Personal Stigma Items: See depression as due to personal weakness TG ↓ p = 0.024; and p= 0.077 at follow-up Be reluctant to disclose depression to others TG ↓ p = 0.012 and p = 0.029 at follow-up Teachers Perceived Stigma Items Believe that other people see depression as due to personal weakness TG ↑ p=0.848 and p = 0.031 at follow-up See other people as reluctant to disclose TG ↑ p= 0.041 and p = 0.555 at follow-up |

| Mifsud et al. (2005) | Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) social phobia subscale Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale (CATS) Child Behavior Checklist-(CBCL) Teacher Rep. social problems subscale |

SCAS Assess children separation anxiety social phobia CATS Assess social threat, personal failure, and hostility (subscales) CBCL Assess social problems (subscale) |

No separate presentation of data |

| Masia Warner et al. (2005) | Self-Report Inventories (ADIS-PC) Severity Independent Evaluator Ratings: Social Phobic Disorders Severity and Change Form (SPDSCF) Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale for Children and Adolescents (LSAS-CA) Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children (SPAI-C) Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A/AP) Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Self-Report Inventories (Loneliness Scale) Parent Report: Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-AP) |

ADIS-PC

Assess social phobia, social anxiety disorder (subscales) SPDSCF Assess Social Phobic Disorders LSAS-CA Assess Social Anxiety SPAI-C Assess Social Phobia SAS-A/AP Assess Social phobia symptoms and Social anxiety in new situations (subscales) CDI Assess Loneliness Scale |

ADIS-PC: No separate presentation of data

SPDSCF (Group × Time effect)TG ↓ p < .0001 LSAS-CA (Group × Time effects)Total score TG ↓ p = .03 Total Avoidance, TG ↓ p = .03 Social Avoidance, TG ↓ p = .04 SPAI-C (Group × Time effects) Performance Anxiety, TG ↑, p = .053 Total Anxiety, TG ↓ p = .056. SASS social phobia symptoms TG ↓ p = .052. SAS-A (Group × Time effect) subscales social anxiety in new situations TG ↓ p = .03. SAS-AP (parent reports) social anxiety in new situations TG ↓ p = .02. |

| Bernstein et al. (2006) | Child and Parent Interview Schedules (ADIS) social phobia items Multid. Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC-C) social anxiety, humiliation-rejection subscale |

ADIS

Assess social phobia, social anxiety disorder (subscales) MASC-C Assess social anxiety, humiliation-rejection (subscales) |

No separate presentation of data |

| Hong et al. (2011) | Child Behavior Checklist-(CBCL) social problems subscale |

CBCL Assess social problems (subscale) | No separate presentation of data |

| Leff et al. (2009) | The Children’s Social Behavior Questionnaire (CSB) Asher and Wheeler Loneliness Scale (ALS) |

CSB

Assess Peer relations, how children think about the social world, and how children think and feel about themselves ALS Assess feelings of Loneliness |

CSB

Relational aggression TG ↓ moderate to large effect size of .74 (Cohen, 1988) Peer likeability TG ↑ very large effect size of 1.73. (Cohen, 1988) ALS Feelings of loneliness TG ↓ moderate effect size of .45.(Cohen, 1988) |

| Owens et al. (2005) | Disruptive Behavior Disorders Structured Interview (DBD) Impairment Rating Scale (IRS) peers relation - Sibling relation - parental relation CBCL (Social subscale) |

DBD

Assess quality of peer relationships and impairment in peer relationships IRS Assess quality of Peers relations and with parents CBCL Assess social problems (subscale) |

DBD

peer relationships TG ↑ p < .05 impairment in peer relationships TG ↓ p < .06 IRS Peers relations TG ↑ p < .06 |

| Sayal et al. (2010) | The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) peer relationship problems |

SDQAssess children pro-social skills and quality of peer relations |

SDQ

Parental and Teacher

Peer problems TG ↓ p<.001 Prosocial behaviour TG ↑ p<.001 |

| Cooper et al. (2010) | The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-PS) prosocial subscale Secondary outcome: The Social Inclusion Questionnaire (SIQ) |

SDQ Assess children pro-social skills and quality of peer relations SIQ Assess Social Inclusion |

SDQ-PS prosocial subscale TG ↑ p<.001 |

| Mufson et al. (2004) | Children's global assessment scale (C-GAS) interaction with friends Social adjustment scale-self report (SAS-SR) |

C-GAS Assess quality of interaction with friends (subscales) SAS Assess Social phobia symptoms and Social anxiety in new situations (subscales) |

C-GAS

Social Functioning dating TG ↑ p=.03 overall social functioning TG ↑ p=.01 family functioning TG ↑ p =.10 SAS-SR. TG ↑ p=.003 |

| O'Leary-Barrett et al. (2013) |

Not reported | Not reported | |

| Stallard et al. (2012) | Secondary outcomes: Revised child anx. and dep. scale (RCADS) |

RCADS Assess Social phobia And quality of School connectedness (subscales) |

RCADS

Social phobia TG ↓ p=.05 School connectedness TG ↑ p=.05 |

| Stallard et al. (2013) | Secondary outcomes: Revised child anx. and dep. scale (RCADS) Children's Automatic Thoughts Scale (CATS) social phobia subscale |

RCADS Assess Social phobia And quality of School connectedness (subscales) CATS Assess social threat, personal failure, and hostility (subscales) |

RCADS School connectedness TG ↑ p=.05 CATS Social phobia sub-scale TG ↓ p=.05 |

| Manassis et al. (2010) | Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) social Anxiety scale, humiliation/rejection subscale Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Interpersonal Problems subscale |

MASC-C Assess social anxiety, humiliation-rejection (subscales) CDI Assess Loneliness Scale |

No separate presentation of data |

| Gunlicks-Stoessel et al. (2010) | Social adjustment scale-self report (SAS-SR) Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ-20) |

SAS Assess Social phobia symptoms and Social anxiety in new situations (subscales) CBQ Assess levels of conflict in children ‘s relationship |

No statistical significance was found |

| Kirsten et al. (2014) |

Psychological Sense of School Membership (PSSM) CAIR Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Interpersonal Problems Subscale |

PSSM Assess quality of psychological membership in school CAIR Assess perceptions of children and adolescents regarding the quality of their relationships (Social, Family, and Academic) |

PSSM School connectedness TG ↓ p= .027 CAIR Interpersonal peer relationships TG ↑ p=.010 |

| Tze-Chun Tanget et al. (2009) |

Not reported | Not reported | |

| Chemtob et al. (2002) | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Stein et al. (2003) | Pediatric Symptom Checklist Child Ptsd Symptom Scale (CPSS) item relationships with friends and item relationships with family Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Interpersonal Problems subscale |

CPSS Assess relationships with friends and item relationships with family CDI Assess Loneliness Scale |

Pediatric Symptom Checklist Psychosocial dysfunction TG ↓ p=.05 and maintain at 6-month |

| Tol WA et al.(2012) | Secondary outcome: The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) prosocial subscale |

SDQ Assess children pro-social skills and quality of peer relations |

No statistical significance was found |

| Kataoka et al. (2011) | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Brian et al. (2012) | Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) (The Social Anxiety scale Humiliation/Rejection subscale) |

MASC-C Assess social anxiety, humiliation-rejection (subscales) |

No separate presentation of data |

↔ no statistical significance was found

↑a statistically significant increase was found

↓ a statistically significant decrease was found

School-based Interventions on Clinical Samples with Active Participation of Teachers and/or Parents

Three of the parent- and teacher-training program treatments concerned children samples with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Table 1). Two studies concerned Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders; more specifically, one dealt with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and the other with both Conduct Disorder (CD) and ODD children samples. One study followed a parenting program for the management of children with Intellectual Disability, one was a Teachers’ educational program on common mental disorders (including Depression, Anxiety, Psychosis, Behavioural disorders) and three studies concerned Psycho-educational and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) group treatments on a sample of children with Anxiety disorders, with participation of both parents and teachers.

School-based Interventions on Clinical Samples Targeting Pupils Only

Two studies concerned Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders, specifically one was on Conduct Disorder (CD), and the other had a children sample with behavioural problems as a specification of Conduct Disorders (Table 2).

One study investigated the efficacy of school-based interventions on a sample of ADHD pupils; two studies investigated the effectiveness of treatment on both Anxiety and Depression disorders in a clinical sample of school children, seven studies focused solely on mood disorder school programs, six studies focused on the treatment of Depression disorder, and one on Emotional distress; four studies were about Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) programs; and one study was a treatment focused on Anxiety Disorders in a clinical school children sample.

Treatment Effectiveness of School-based Interventions on Clinical Samples with Active Participation of Teachers and/or Parents

The overall findings on school-based treatment of clinical samples with the active participation of teachers and/or parents were suggestive of the effectiveness of these programs in reducing the symptoms of most mental disorders. Only two studies out of ten were not associated with improved outcomes in children. Three studies investigated training for teachers that specifically focused on improving the knowledge and management of school children’s mental disease, and on decreasing attributional bias and stigma towards mental illness. The aim of these interventions was to improve school policies [21-23]. Effectiveness was assessed in terms of increased knowledge and more positive attitude towards talking about mental health (decrease of stigma) for both teachers and students. As depicted in Table 1, one study reported positive results; two interventions did not show improved outcomes in children [22, 23]. The other seven studies did not set integration as their main goal. Two of these studies evaluated and confirmed the effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with the participation of parents in a clinical sample of children with anxiety disorders. Both studies used clinical measures as outcome measures: Clinical Global Impressions (CGI), and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) [24, 25]. Two studies investigated the positive results of two combined manualized programs: Basic Incredible Years Parenting Programme and Dinosaur School Programme for children with Conduct Disorders (ODD). The two mixed programs included: positive discipline strategies, effective strategies for coping with stress, and social skills. They shared The Wally Child Social Problem-Solving Detective Game (WALLY) as main outcome, as shown in Tables 1 and 3 [8]. Finally, three studies were heterogeneous on clinical sample type (ADHD, Anxiety, ID) and verified the effectiveness of school programs that combine different techniques: CBT, behavioural techniques, skills training, family systems interventions and psycho-education: Barkley’s programme; Social Effectiveness Therapy for Children (SET-C), Parents Plus Children’s Programme. They all used the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) as main outcome measure, as shown inTables 2 and 3 [26-28].

Treatment Effectiveness of School-based Interventions on Clinical Samples Targeting Pupils Only

The overall findings about school-based treatment on clinical samples targeting pupils only were suggestive of the effectiveness of these programs in reducing the symptoms of most mental disorders. Only three studies were not associated with improved outcomes, and none of these specified integration as their specific goal. Most of the retrieved studies concerned a school-based intervention on a clinical sample with a target on pupils only (n=10), and consisted of a mixture of CBT techniques. Some studies were manualized and concerned verified interventions in a school setting. One study, in particular, used the Resourceful Adolescent Program (RAP) [29] (Rose et al., 2014) that incorporates CBT and Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT-A) principles, including stress management skills, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, and conflict resolution within families. However the results of this study revealed that adolescents completing RAP did not report significantly reduced depressive symptoms. The preponderance of studies based on CBT concerned samples of school children with Depression Disorder (n= 4), one included treatment of Anxiety and Depression Disorders and Behavioural problems, one focused on Anxiety Disorder only, one on Behavioural problems, and three studies targeted Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms [29-38]. One of them did not identify any major effect on primary outcomes [36].

Three Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT-A) school-based interventions focused on Depression symptoms using Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) as main outcome. They reported significantly higher effects on reducing the severity of depression symptoms [39-41]. One intervention was performed as culturally-adapted social problem solving Intervention for Conduct problems (CD) in girls with relational aggression (GRAs) style. Greater decrease in teachers’ reports about relational aggression from pre-treatment to post-treatment was found for students under treatment than for students in the control group. The main outcome measure in this study was derived from Asher and Wheeler Loneliness Scale Children’s Depression Inventory [42]. One Behavioral Treatment intervention was performed on Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), Conduct problems (CD) and Disruptive Behavior Disorders (DBD) symptoms in a sample of schoolchildren. The study used the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Structured Interview (DBD) as main outcome measure and showed significant improvement [43]. Another study describing a school-based humanistic counselling intervention focused on the presence of Emotional distress symptoms in a sample of school-children using The Self-Report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), but showed non-significant results on the primary outcome measure [44].

Finally one study reported results from a specific psychosocial treatment for children who showed symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after Hurricane exposure. Data showed significant differences on the Kauai Recovery Inventory (KRI) after treatment and at follow-up (X months) [45] in treatment-group children, as compared to children in the control group.

Social Outcome and Effectiveness of School-based Interventions on Clinical Samples

As stated above, only a few studies had a specific focus on investigating the integration of students with psychiatric diagnosis in the classroom; therefore all the studies that involved a clinical population in a school setting were included and changes in social outcome as a main or secondary outcome measure were reviewed. Five studies out of twenty-seven did not report a main outcome or secondary outcome measures as far as social inclusion or exclusion variables were concerned. It was not possible to extrapolate data from six studies, because for instance social variables were part of a subscale of the outcome measure that was used (are reported in Table 3 as No separate presentation of data).

Considering all the reviewed studies, the most frequently used measures of social variables were subscales of instruments such as the social subscale of The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), the Social Anxiety subscale and Humiliation/rejection subscale of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC), and the interpersonal problems subscale of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). The chosen instruments (though not always as the main outcome) that seemed to specifically focus on treatment effectiveness in relation to social dimensions were: Personal and Perceived Stigma Items, The Social Inclusion Questionnaire' (SIQ), Asher and Wheeler Loneliness Scale (ALS), the Psychological Sense of School Membership (PSSM), The Wally Child Social Problem-Solving Detective Game (WALLY) and the IRS (Peers relation, Sibling relation, Parental relation). Overall, as shown in Table 3, out of sixteen studies that reported indicators of social values or dimensions, thirteen studies reported positive results of social variables,while three studies found no effects on these outcomes.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the literature on implemented and verified school-based practices addressed to clinical populations of students, and targeting specific mental disorders to improve the integration of pupils with specific mental health problems in the classroom and the school system. Of all the studies including clinical populations that were screened, only few concerned randomized controlled trials, which is the golden standard methodology to assess a program’s effectiveness. In particular, this study evaluated the effectiveness of twenty-seven interventions on clinical populations. A larger amount of programs implementing standardized models with verifiable and evidence-based practices is still needed. Indeed in almost all the assessed studies, the main outcome, the effect size and the number required for treatment are not always clearly or fully indicated: it was therefore not possible to include these data in the tables. There is a clear call for the use of evidence-based practice (EBP) in schools. It is necessary to identify, better understand and define the potential barriers to the use of empirical interventions in school settings. This information could be used to guide strategies that promote EBP among school-based staff and clinicians [46]. A complicated issue in school interventions may involve the question on how all the elements of known evidence-based programs can fit in the complex network of a specific school community, and how these programs can be successfully and effectively implemented and coordinated [11]. Evidence-based practice has shown that through involvement in interventions, the whole school and its surrounding community as a unit of change produce better performance in promoting and reinforcing students’ health behaviors [17, 18, 47]. Engaging teachers in proactive and cooperative classroom management may produce positive environments that encourage and reinforce health classroom behavior. School practices and interventions need to improve psychosocial functioning of school children in both school settings and at home, by involving parents, teachers, and pupils [47, 18, 11, 8] However, out of the twenty-seven studies included in this review only 37% involved the active participation of parents and teachers in school treatment. Therefore, the practices that proved to be the most effective are not always concretely implemented [11]. Very few studies have also involved parents as well as teachers and clinicians as evaluators in the assessment phase. Several evidences indicate significant differences between the different types of evaluation observers. This approach would make it possible to assess differences in effectiveness between different studies in a more reliable manner [48]. School-based treatments for mental disorders can also raise the risk of stigmatizing and over-diagnose students, and subsequently violate their social interactions and peer acceptance [1, 2]. Social interactions can prevent the development of stigma towards mental disease, and young people’s social networks are influential [49-51]. A lack of pro-social strategies is often disliked by peers and could result in social exclusion. For children with a mental disease, peer-rejection could exacerbate antisocial development, while acceptance by peers could buffer the effects of dysfunctional behaviours. For this reason interventions should also target peer acceptance and strengthen social competence in the school setting and in the community [8, 6, 7, 52].

To avoid the danger of stigmatization, there is some agreement that school-based programs should involve children in experiential activities, engage students' feelings and behaviour, and facilitate students’ interaction with others. However, out of the twenty-seven studies included, only 59% considered social values or dimensions after treatment, 48% reported positive results on prosocial behaviors and quality of interactions as an outcome of the program, and maintained them at follow-up. More programs are needed that involve clinical populations of schoolchildren and implement standardized models of intervention, taking into account social inclusion outcome in the school setting. It would be necessary to monitor if these values and indicators of integration remain stable or change during the whole educational experience of students with mental disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schachter H, Girardi A, Ly M et al. Effects of school-based interventions on mental health stigmatization a systematic review. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Social distance towards the mentally ill results of representative surveys in the Federal Republic of Germany. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1 ):131–41. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mura G, Carta MG, Helmich I, et al. Physical activity interventions in schools for improving lifestyle in European Countries. Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health. 2015;11:77–101. doi: 10.2174/1745017901511010077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sancassiani F, Pintus E, Holte A et al. Enhancing the emotional and social skills of the youth to promote their wellbeing and positive development a systematic review of universal school-based randomized. Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health. 2015;11:21–40. doi: 10.2174/1745017901511010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Stigma and discrimination against the mentally ill in Europe Briefing of the WHO European Ministerial Conference on Mental Health. Facing the Challenges Building Solutions 12-15 January. 2005;Helsinki [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Salzer BV , et al. Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Dev. 2003;74(2 ):374–93. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster-Stratton C, Lindsay DW. Social competence and conduct problems in young children Issues in assessment. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28(1 ):25–43. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drugli MB, Larsson B. Children aged 4-8 years treated with parent training and child therapy because of conduct problems generalization effects to day-care and school settings. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;15(7 ):392–9. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster-Stratton C, Lindsay DW. (1999) Social competence and conduct problems in young children Issues in assessment. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28(1 ):25–43. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weist MD, Evans SW, Lever NA, Lowie JA, Lever NA, Ambrose MG, Tager SB, Hill S. Partnering with families in expanded school mental health programs. Handbook of School Mental Health Advancing Practice and Research. 2003:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg MT, Weissberg RP, O'Brien MU, Zins JE, Fredericks L, Elias MJ. Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. Am Psychol. 2003;58(6-7 ):466–74. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugai G, Horner RH. The evolution of discipline practices School-wide positive behavior supports. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2002;24:23–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Putnam R, Handler M, Handler C, Ramirez P, Luiselli J. Improving student bus-riding behavior through a whole-school intervention. J Appl Behav Anal. 2003;36:583–90. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson Jr. Designing schools to meet the needs of students who exhibit disruptive behavior. J Emot Behav Disord. 1996;4:147–61. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor-Greene S, Brown D, et al. Schoolwide behavior support Starting the year off right. J Behav Edu. 1997;7:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker HM, Horner RH, Sugai G et al. Inte grated approaches to preventing antisocial behavior patterns among school-age children and youth. J Emot Behav Disord. 1996;4:193–256. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 2011;82(1 ):405–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weare K Nind M. Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools what does the evidence say?. Health Promot Int. 2011;26(1):i29–i69. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dar075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantone E, Piras P, Vellante M, et al. Interventions on bullying and cyberbullying in schools a systematic review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health. 2015;11:58–76. doi: 10.2174/1745017901511010058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tajfel H, Billig MG, Bundy RP, Flament C. Social categorization and intergroup behavior. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1971;1(2 ):149–78. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray DW, Rabiner DL, Hardy KK. Teacher management practices for first graders with attention problems. J Atten Disord. 2011;15(8 ):638–45. doi: 10.1177/1087054710378234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jorm AF, Kitchener BA, Sawyer MG, Scales H, Cvetkovski S. Mental health first aid training for high school teachers a cluster randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayal K, Owen V, White K. Impact of early school-based screening and intervention programs for ADHD on children's outcomes and access to services follow-up of a school-based trial at age 10 years. Arch Pediatric Adolescent Med. 2010;164(5 ):462–9. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mifsud C, Rapee RM. Early intervention for childhood anxiety in a school setting outcomes for an economically disadvantaged population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(10 ):996–1004. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000173294.13441.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein GA, Bernat DH, Victor AM, Layne AE. School-based interventions for anxious children 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(9 ):1039–47. doi: 10.1097/CHI.ob013e31817eecco. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostberg M, Rydell AM. An efficacy study of a combined parent and teacher management training program for children with ADHD. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;66(2 ):123–30. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.641587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masia-Warner C, Klein R, Dent H, et al. School-based intervention for adolescents with social anxiety disorder results of a controlled study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2005;6:707–22. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-7649-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hand A, Raghallaigh CN, Cuppage J. A controlled clinical evaluation of the Parents Plus Children's Program for parents of children aged 6-12 with mild intellectual disability in a school setting. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;18(4 ):536–55. doi: 10.1177/1359104512460861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose K, Hawes D, Hunt C. Randomized controlled trial of a friendship skills intervention on adolescent depressive symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(3 ):510–20. doi: 10.1037/a0035827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong L, Yufeng W, Agh K. Preventing behavior problems among elementary schoolchildren impact of a universal school-based program in China. J Sch Health. 2011;81(5 ):273–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Leary-Barrett M, Topper L, Al-Khudhairy N, et al. Two-year impact of personality-targeted, teacher-delivered interventions on youth internalizing and externalizing problems a cluster-randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(9 ):911–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stallard P, Phillips R, Montgomery AA, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of classroom-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in reducing symptoms of depression in high-risk adolescents. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(47 ):vii–xvii, 1-109. doi: 10.3310/hta17470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stallard P, Sayal K, Phillips R, et al. Classroom based cognitive behavioral therapy in reducing symptoms of depression in high risk adolescents pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;345:e6058. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manassis K, Wilansky-Traynor P, Farzan N, Kleiman V, Parker K, Sanford M. The feelings club randomized controlled evaluation of school-based CBT for anxious or depressive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(10 ):945–52. doi: 10.1002/da.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH et al. A mental health intervention for school children exposed to violence a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290(5 ):603–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tol WA, Komproe IH, Jordans MJ, et al. Outcomes and moderators of a preventive school-based mental health intervention for children affected by war in Sri Lanka a cluster randomized trial. World Psychiatry. 2012;11(2 ):114–22. doi: 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kataoka S, Jaycox LH, Wong M, et al. Effects on school outcomes in low-income minority youth preliminary findings from a community-partnered study of a school-based trauma intervention. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(3 Suppl 1):S1–71-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galla BM, Wood JJ, Chiu AW et al. One year follow-up to modular cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders in an elementary school setting. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43(2 ):219–26. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mufson L, Dorta KP, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Olfson M, Weissman MM. A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;82(3 ):510–20. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Mufson L, Jekal A, Turner JB. The impact of perceived interpersonal functioning on treatment for adolescent depression IPT-A versus treatment as usual in school-based health clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(2 ):260–7. doi: 10.1037/a0018935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang TC, Jou SH, Ko CH, Huang SY, Yen CF. Randomized study of school-based intensive interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents with suicidal risk and par suicide behaviors. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63(4 ):463–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leff SS, Gullan RL, Paskewich BS, et al. An initial evaluation of a culturally adapted social problem-solving and relational aggression prevention program for urban African-American relationally aggressive girls. J Prev Interv Community. 2009;37(4 ):260–74. doi: 10.1080/10852350903196274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Owens JS, Richerson L, Beilstein EA, Crane A, Murphy CE, Vancouver JB. School based mental health programming for children with inattentive and disruptive behavior problems first-year treatment outcome. J Atten Disord. 2005;9(1 ):261–74. doi: 10.1177/1087054705279299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cooper M, Rowland N, McArthur K, Pattison S, Cromarty K, Richards K. Randomized controlled trial of school-based humanistic counseling for emotional distress in young people feasibility study and preliminary indications of efficacy. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2010;22:4–12. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chemtob CM, Nakashima JP, Hamada RS. Psychosocial intervention for post disaster trauma symptoms in elementary school children a controlled community field study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(3 ):211–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walker HM. Use of Evidence-Based Intervention in Schools Where We've Been, Where We Are, and Where We Need to Go. School Psychol Rev. 2004;33(3 ):398–407. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Catalano R, Berglund ML, Ryan GAM, Lonczak HS, Hawkins JD. Positive youth development in the United States Research ?ndings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2004;591(1 ):98–124. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sonuga-Barke EJ, Brandeis D, Cortese S, et al. Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3 ):275–89. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pinto-Foltz MD, Logsdon MC, Myers JA. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of a knowledge-contact program to reduce mental illness stigma and improve mental health literacy in adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(12 ):2011–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pescosolido BA, Martin JK. Stigma and the sociological enterprise. In: Avison WR, Pescosolido BA, Mcleod JD, editors. Mental Health, Social Mirror. NY:: Springer; 2007. pp. 307–28. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crosnoe R, McNeely C. Peer relations, adolescent behavior, and public health research and practice. Fam Community Health. 2008;31(15 ):S71–S80. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000304020.05632.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agabio R, Trincas G, Floris F, Carta MG. A systematic review of school based alcohol and other drugs prevention programs. Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health. 2015; 11:102–112. doi: 10.2174/1745017901511010102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]