Abstract

Background:

Bacopa monnieri (L.) Pennell, commonly known as Brahmi is an important medicinal plant traditionally used as memory enhancer and antiepileptic agent.

Objective:

The present study investigated antioxidant and stress resistance potentials of B. monnieri aqueous extract (BMW) using Caenorhabditis elegans animal model system.

Materials and Methods:

The antioxidant activity of the BMW was measured using in vitro (DPPH, reducing power and total polyphenol content) and in vivo (DCF-DA assay) assays. The antistress potential of BMW (0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 mg/ml) was evaluated through thermal stress (37°C) and oxidative stress (10 mM paraquat) using C. elegans. Quantification of the HSP-16.2 level was done using CL2070 transgenic worms.

Results:

Present study reveals that BMW possess in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities. BMW significantly enhanced stress tolerance and increased the mean lifespan of worms during thermal and oxidative stress, although it did not extend lifespan at 20°C and attenuated age dependent decline in physiological behaviors. Moreover, it was shown that BMW was able to up-regulate expression of stress associated gene hsp-16.2, which significantly (P < 0.001) extends the mean lifespan of worms under stress conditions.

Conclusion:

The study strongly suggests that BMW acts as an antistressor and potent reactive oxygen species scavenger which enhances the survival of the worms in different stress conditions.

Keywords: Antioxidant, antistress, Bacopa monnieri, Caenorhabditis elegans, reactive oxygen species

INTRODUCTION

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are chemically active molecules generated by cellular metabolism and various stresses like ultraviolet radiation, chemicals, and heat.[1,2] ROS are able to damage the major biological macromolecules including DNA, lipids, and protein and cause various diseases.[3] Although major world's population (approximate 60–80%) still relies on the traditional system for the cure of common diseases;[4] utilization of herbal medicines is promotive and preventive in therapeutic approach. Therefore, search for natural drugs of the plant origin has become a central focus for current research.

B. monnieri (L.) Pennell, (Plantagenaceae) commonly known as Brahmi is an important medicinal plant having a major role in traditional and modern systems of Indian medicine. This plant is used in the treatment of mental disorders such as epilepsy and mental retardation, in asthma and as a cardiotonic and diuretic.[5,6] B. monnieri extract is also known to possess anticancer and antioxidant properties.[7,8] Since the systematic evaluation of efficacy, safety, and mode of action of plant extracts in mammalian model is time consuming and costly, so there was a need of such a model organism in which results could be obtained easily, in less time and more efficiently. Caenorhabditis elegans, a free-living nematode is such a promising model organism in which aging and ROS associated manipulation can be done more efficiently and accurately in short course of time. Besides its short lifespan, the ease of genetic and dietary manipulations has also led C. elegans to become established at the forefront of aging studies.[9] Previously, stress- and aging-related studies have been demonstrated using various plant extracts and molecules such as EGb 761, EGCG, Ocimum sanctum, curcumin, and 4-HEG.[10,11,12,13,14] Keeping in view the vivid pharmacological properties of B. monnieri, the present investigation was undertaken to assess the efficacy of different pharmacological doses viz. 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 mg/ml of BMW on ROS scavenging, stress tolerance, lifespan, pharyngeal pumping, and the chemotaxis activity in C. elegans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and extraction

B. monnieri (var. CIM-Jagriti, No. BM-16) was obtained from our cultivation farm at Lucknow, India, which is conserved in Council of Scientific and Industrial Research - Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants gene bank repository. The plant material was washed thoroughly under running tap water and was dried conventionally under shade. The dried plant material was grounded to a coarse powder and used for extract preparation. Cold extraction method[15] was followed to prepare the aqueous extract. The extract was dried using a round bottom rotary vacuum evaporator and dissolved in deionized water to prepare the stock solutions.

In vitro antioxidant studies

Total polyphenolic content and reducing power estimations were done according to Luqman et al.[16] and DPPH free radical scavenging assay was determined as described by Movalia et al.[17] with minor modifications.

Strains, culture and BMW treatment of Caenorhabditis elegans

N2 Bristol (Wild-type), TK22 (mev-1[kn-1]) and CL2070, dvIs70 Is[hsp-16.2::gfp; rol-6(su1006)] strains of C. elegans and Escherichia coli OP50 were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, University of Minnesota, USA. The strain were cultured and maintained at 20°C on nematode growth medium (NGM) seeded with E. coli OP50 bacteria. Worms were treated with different concentration (0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 mg/ml) of BMW from L1 stage.

Lifespan assay

Age-synchronized worms were used for the lifespan assay. Different concentrations of BMW were spotted over the bacterial lawn, and the isolated eggs were allowed to hatch. L4 worms were transferred to fresh plates containing 50 μM 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (Sigma-Aldrich) which block progeny development. Worms were transferred to fresh plates in every 3–4 days to assure the presence of the extract throughout the experiment. Survival of the worms was scored daily.

Pharyngeal pumping assay

Pharyngeal pumping of the worms was recorded as the movement of the pharynx terminal bulb.[18] Worms were grown on NGM plates, treated with different concentrations of BMW from L1 stage. Pumping was recorded for 30 s interval in every alternate day from adult day 1.

Chemotaxis assay

Chemotaxis assays were performed as described by Brown et al.[18] with minor modifications. 1M sodium acetate was used as an attractant. Chemotaxis index (CI) was calculated by following formula:

CI = (A − B)/(A + B)

Where A = Number of worms at the attractant location, B = Number of worms at the control location, A + B = Total number of worms in the plate. All experiments were performed with three independent population.

Stress resistance assay

Stress tolerance of the worms was determined as described by Wilson et al.[19] with minor modifications. The life cycle of C. elegans is comprised of the embryonic stage, four larval stages (L1-L4) and adulthood. Day 0 stands for L4 stage, and the days are counted consequently as day 1, day 2, day 3, etc. Adult day 2 reflects the worm that is 2 days elder than L4 and this stage is usually preferred for stress assays. Therefore for thermal stress adult day 2 worms with and without BMW were placed at 37°C and survival of worms was recorded after every hour by touch provoked method.[20] For oxidative stress age synchronized BMW treated and untreated wild-type adult day 2 worms were transferred to NGM plates containing 10 mM paraquat (methyl viologen dichloride, Sigma-Aldrich). Survival of the worms was scored daily till the death of last worm.

Intracellular reactive oxygen species detection assay

The assay was conducted as described by Smith and Luo.[21] Adult day 2 worms were used for intracellular ROS determination. Thirty age synchronized worms were collected in 300 μl of 0.1% PBST and equally timed homogenization and sonication. The homogenized samples were transferred to the 96 well plate and incubated in the presence of 50 μM H2DCF-DA. Fluorescent readings were measured using spectra max M2 multimode microplate reader, (molecular devices) at 485 nm excitation and 530 nm emission. Observations were recorded at every 20 min for 2 h and 30 min at 37°C.

Green fluorescent protein quantification and visualization

For the quantification of HSP-16.2, age synchronized CL2070 (HSP-16.2: Green Fluorescent Protein [GFP]) adult day 1 worms were transferred to different BMW treated and untreated plates for 48 h. Pretreated worms were shifted to 37°C for 2 h and then allowed to recover for 24 h.[4,22] After recovery, worms were mounted on 3% agarose pad and images were assessed under fluorescence microscope (Leica). For GFP quantification images were analyzed by Image J Software, National Institute of Health, USA.

Statistical analysis

Significant difference between the lifespan was determined using Kaplan–Meier survival curves (MedCalc Software bvba, Belgium). Data other than lifespan were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA in ASSISTAT statistical assistance software, DEAG-CTRN-UFCG, Campina Grande, Paraiba State, Brazil. Difference between the data was considered as significant at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

BMW having in vitro antioxidant activity

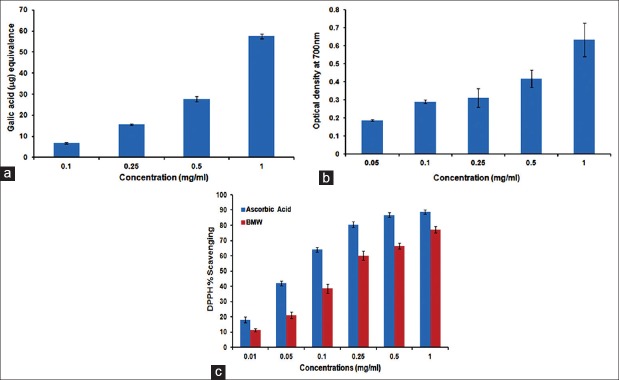

Plant polyphenol plays a major role in free radical scavenging activities. Our results revealed that BMW has 57.54 ± 1.1 μg/mg of total phenolics in terms of gallic acid equivalent [Figure 1a]. Reducing power of BMW was increased with the rise of concentration [Figure 1b]. Similar results were also obtained for DPPH scavenging activity with IC50 value 0.336 mg/ml [Figure 1c].

Figure 1.

BMW showed strong in vitro antioxidant potential. In BMW (a) total phenolic content (b) reducing power and (c) DPPH scavenging activity increased as BMW concentration raised

BMW unable to extend lifespan of wild-type Caenorhabditis elegans under normal culture condition

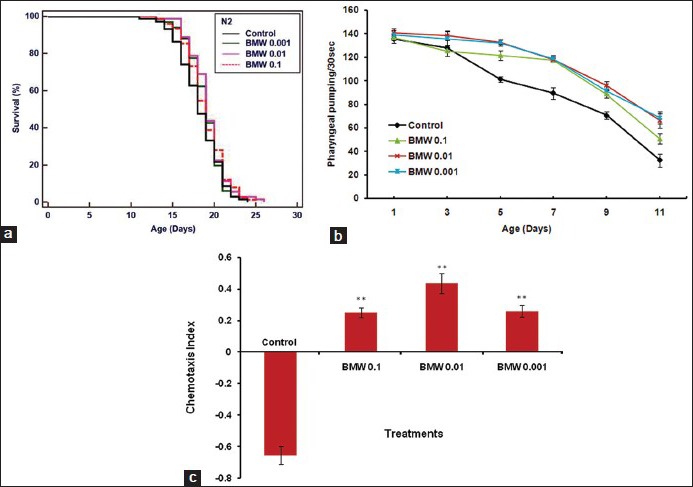

Our results revealed that there was no significant increase in mean lifespan of C. elegans in any of the treatment viz. 0.1, 0.01, 0.001 mg/ml (P = 0.537, P = 0.799, P = 0.456) [Supplementary material Figure S1a]. Only 4–6% mean lifespan was increased in different test concentration of BMW. However, we found that the first death was delayed in all BMW concentrations as compared to nontreated control worms [Table 1].

Figure S1.

Effect of BMW on lifespan and age-associated physiological behavior of C. elegans. (a) All the BMW concentration shows a nonsignificant modulation in mean lifespan of wild type N2 worms. (b) BMW significantly attenuates the rate of decline in movement of pharynx bulb. (c) BMW enhances the chemotaxis index significantly. Survival plot was drawn by Kaplan–Meier survival curves (**P < 0.001 vs. Control)

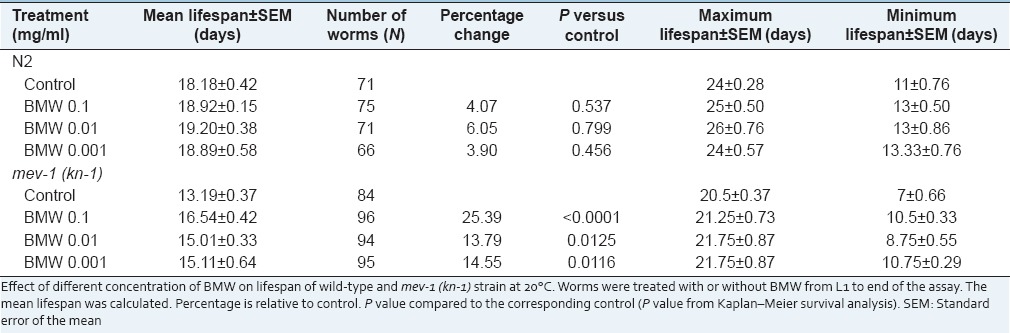

Table 1.

Effect of BMW on the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans at 20°C

Effect of BMW on pharyngeal pumping

Initially, pharyngeal pumping rate of worms in all test concentrations including control exhibited same results but after 3 days all the BMW concentrations attenuated the decline in pumping rate significantly (P = 0.01) as compared to untreated control [Supplementary material Figure S1b].

BMW increased the chemotaxis index of the worms

BMW treatment enhanced the CI of adult day 5 wild-type worms than the untreated control worms. Maximum CI was observed in 0.01 mg/ml concentration of the BMW (P < 0.001) [Supplementary material Figure S1c].

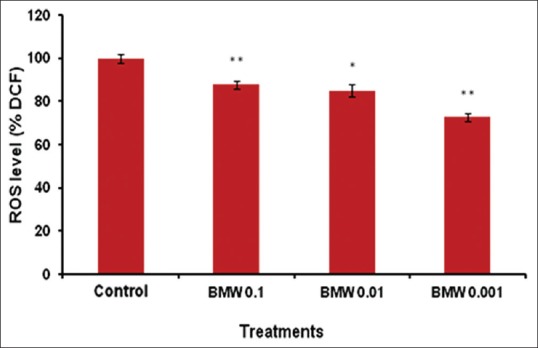

BMW reduced reactive oxygen species level in Caenorhabditis elegans

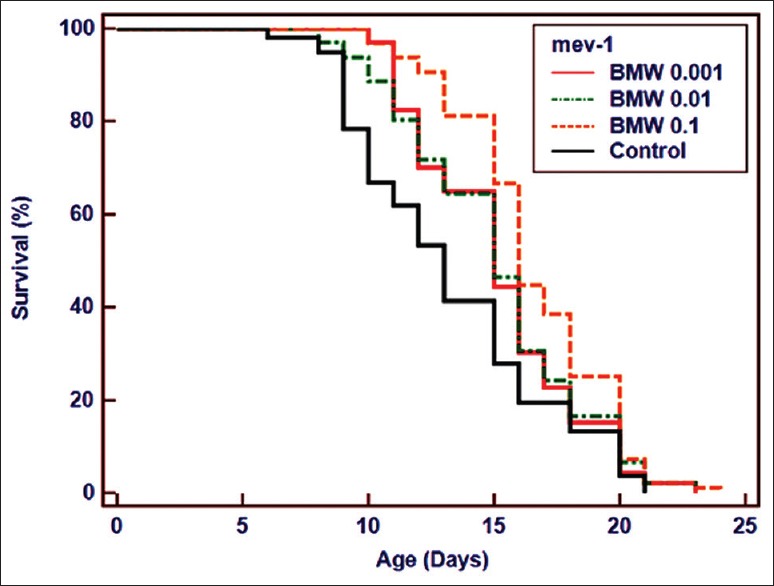

The lethality of stress and associated aging is directly linked to the damage caused by ROS, resulting in the decline of cells and tissues. We evaluated intracellular ROS levels in BMW treated and untreated worms by H2DCF-DA dye. All the BMW concentrations reduced the ROS level inside the worms significantly as compared to untreated-control [Figure 2]. Maximum reduction in ROS levels was recorded in worms treated with 0.001 mg/ml followed by other treatments. Furthermore, lifespan of a C. elegans mutant mev-1(kn-1) was also observed which has a short lifespan due to the accumulation of ROS.[23] We observed that all test concentrations of BMW increased mean lifespan of mev-1 mutant worms significantly in comparison to control worms [Table 1 and Figure 3]. Maximum increase (25.39%) in mean lifespan was found in 0.1 mg/ml concentration of the extract.

Figure 2.

BMW reduces intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) level in wild-type C. elegans. The graph was plotted as a relative change in ROS compared to control at 100%. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Statistically significant at **P < 0.01

Figure 3.

BMW (0.1–0.001 mg/ml) increased mean lifespan of mev-1(kn-1) mutant. Survival plot was drawn by Kaplan-Meier survival curves

BMW enhanced survival of Caenorhabditis elegans under stress conditions

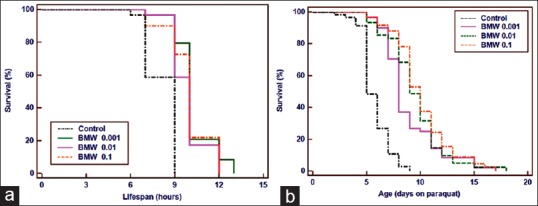

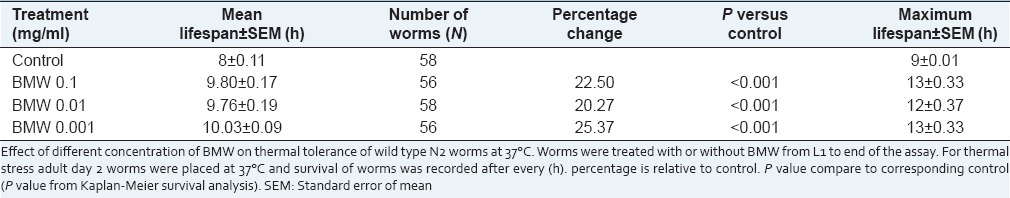

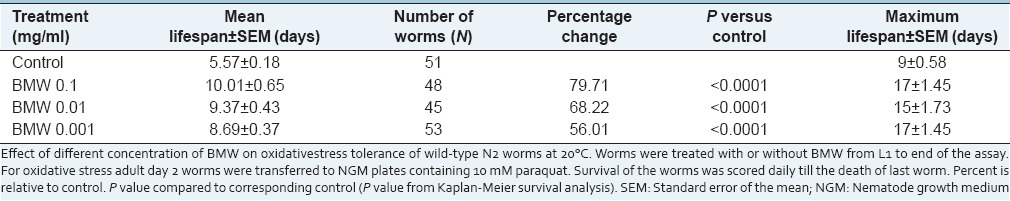

In the present study, it was recorded that all the test concentrations significantly (P < 0.001) increased the mean lifespan of wild-type worms when challenged to 37°C. The increase in mean lifespan was recorded 22.50, 20.27, and 25.37% in 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 mg/ml treated worm respectively as compared to untreated control worms [Figure 4a and Table 2]. Consistent with the findings of thermal stress BMW also enhanced resistance to oxidative stress significantly (P < 0.0001) in wild-type worms. The survival percentage was found to increase in BMW treated groups in a dose-dependent manner from 0.001 to 0.1 mg/ml [Figure 4b and Table 3].

Figure 4.

All test concentration of the BMW (0.1–0.001 mg/ml) extract significantly enhances resistance against thermal stress (a) and paraquat induced oxidative stress (b) survival plot was drawn by Kaplan–Meier survival curves

Table 2.

Effect of BMW on the thermal-tolerance of the Caenorhabditis elegans at 37°C

Table 3.

Effect of BMW on the paraquat induced oxidative stress tolerance in wild-type Caenorhabditis elegans at 20°C

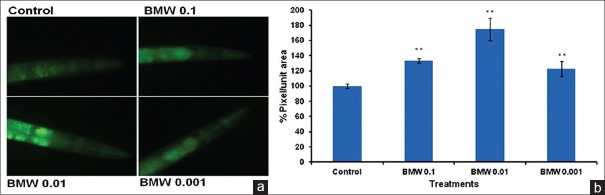

BMW up-regulates the expression of HSP-16.2

Our results with CL2070 worms indicated that the expression of HSP-16.2 was enhanced in worms treated with BMW [Figure 5a]. In BMW treated worms HSP-16.2 level was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than untreated control worms [Figure 5b].

Figure 5.

BMW up-regulates HSP-16.2::GFP expression in transgenic C. elegans CL2070. Images of worms captured using 40 × objective (a) and pixel/unit area was quantified by Image J (NIH) software (b) **P < 0.001 versus control

DISCUSSION

The present study revealed that all test concentrations of BMW nonsignificantly [Table 1] extended the mean and maximum lifespan but delayed the first death of the wild-type worm. BMW protected age-associated behavioral declination such as pharyngeal pumping and CI in C. elegans [Supplementary material Figures S1b and S1c]. This finding indicated that BMW improved the health span of the worms and attenuated the decline in age-related physiological behaviors.

The phytomolecules and plant extracts efficiently improve the health and has been widely used for treatment of various ailments caused by different stressors due to their metal chelating and free radical scavenging properties. To explore such possibilities, in vitro and in vivo free radical scavenging activity of BMW was observed. The in vitro antioxidant activities depend on the total polyphenolic contents.[16] We demonstrated that in BMW total polyphenolic content was increased in concentration dependent manner, due to which reducing power and DPPH radical scavenging activity were also increased as the concentration rises. In consistent with previous studies,[8] our results showed that BMW have in vitro antioxidant activities [Figure 1]. Further in vivo intracellular free radical scavenging activity of the extract in C. elegans was measured by a nonfluorescent dye H2DCF-DA. This nonfluorescent dye after interaction with intracellular ROS converted into a fluorescent compound 2’7’-dichlorofluorescein (DCF).[24] Our results showed that all BMW concentrations reduces the intracellular ROS level in C. elegans. Final assessment of extract's antioxidant activity was done using pro-aging mitochondrial mutant mev-1 (kn-1). mev-1 is a subunit of complex II in the electron transport chain[23] and the mev-1 deletion mutant is hypersensitive to oxidative stress and displays a reduced lifespan, mostly due to mitochondrial ROS overproduction. BMW increased the lifespan of mev-1 mutant by 14–25% in comparison to untreated control worms [Table 1]. These results verified the in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity of BMW.

The effect of BMW on wild-type worms against thermal and oxidative stress was examined. In the present study, we demonstrate that BMW significantly enhanced stress tolerance and increased the mean lifespan of the worms during thermal stress [Table 2] and paraquat induced oxidative stress [Table 3]. To investigate the effect of BMW on stress response gene, we examined the HSP-16.2:GFP expression using CL2070 mutant having gfp transgene fused with hsp-16.2 gene. HSP-16.2 encodes an important heat shock protein that is a member of the HSP family, and it helps to protect cells from various stresses. We observed that BMW supplementation up-regulates the expression of HSP-16.2 [Figure 5a and b]. Similar to other herbal formulations,[4,19] our results also suggest that BMW enhance the expression of small heat shock proteins and reduce the ROS level which might be the possible explanation of worms’ survival under stress conditions.

CONCLUSION

The potential of natural herbs for medicinal purposes due to their safer mode of action and least side effects has renowned. As such, this study confirms that BMW possess in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities and is able to up-regulate expression of stress resistance associated gene hsp-16.2, which significantly increase the lifespan of worms under stress conditions. This finding will be helpful in developing novel herbal drugs from BMW for various stress-related complications in humans. Importantly, these results can be transferred and explored in mammalian systems due to the high homology between C. elegans and the human beings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to the Director, CSIR - Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants for his valuable support and suggestions. First author (VS) is grateful to CSIR-HRDG for providing grant-in-aid. Authors are thankful to Mrs. Shilpi K. Saikia for her editorial comments and enhancing the language of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gutteridge JM, Halliwell B. Free radicals and antioxidants in the year 2000. A historical look to the future. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;899:136–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruskov VI, Malakhova LV, Masalimov ZK, Chernikov AV. Heat-induced formation of reactive oxygen species and 8-oxoguanine, a biomarker of damage to DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1354–63. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.6.1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Raamsdonk JM, Hekimi S. Reactive oxygen species and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans Causal or casual relationship? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:1911–53. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zang X. Traditional medicine: Its importance and protection. In: Twarog S, Kapoor P, editors. Protecting and Promoting Traditional Knowledge: Systems, National Experiences and International Dimensions. Part I. The Role of Traditional Knowledge in Health Care and Agriculture. New York: United Nations; 2004. pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moharana D, Moharana S. A clinical trial of mental in patients with various types of epilepsy. Probe. 1994;33:160–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dar A, Channa S. Bronchodilatory and cardiovascular effects of an ethanol extract of Bacopa monniera in anaesthetized rats. Phytomedicine. 1997;4:319–23. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(97)80040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elangovan V, Govindaswamy S, Ramamoorthy N, Balasubramanian K. In vitro studies on the anticancer activity of B. monniera. Fitoterapia. 1995;66:211–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand T, Mahadeva N, Swamy MS, Farhath K. Antioxidant and DNA damage preventive properties of Bacopa monniera (L) Wettst. Free Radic Antioxid. 2011;1:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guarente L, Kenyon C. Genetic pathways that regulate ageing in model organisms. Nature. 2000;408:255–62. doi: 10.1038/35041700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kampkötter A, Pielarski T, Rohrig R, Timpel C, Chovolou Y, Wätjen W, et al. The Ginkgo biloba extract EGb761 reduces stress sensitivity, ROS accumulation and expression of catalase and glutathione S-transferase 4 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:139–47. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Jie G, Zhang J, Zhao B. Significant longevity-extending effects of EGCG on Caenorhabditis elegans under stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandey R, Gupta S, Shukla V, Tandon S, Shukla V. Antiaging, antistress and ROS scavenging activity of crude extract of Ocimum sanctum (L.) in Caenorhabditis elegans (Maupas, 1900) Indian J Exp Biol. 2013;51:515–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao VH, Yu CW, Chu YJ, Li WH, Hsieh YC, Wang TT. Curcumin-mediated lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2011;132:480–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shukla V, Yadav D, Phulara SC, Gupta MM, Saikia SK, Pandey R. Longevity-promoting effects of 4-hydroxy-E-globularinin in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1848–56. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adome RO, Gachihi JW, Onegi B, Tamale J, Apio SO. The cardiotonic effect of the crude ethanolic extract of Nerium oleander in the isolated guinea pig hearts. Afr Health Sci. 2003;3:77–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luqman S, Srivastava S, Kumar R, Maurya AK, Chanda D. Experimental assessment of Moringa oleifera Leaf and Fruit for Its antistress, antioxidant, and scavenging potential using in vitro and in vivo assays. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/519084. 519084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Movalia D, Mishra S, Gajera F. Free radical scavenging activity of Randia dumetorum Lamk. fruits. Int Res J Pharm. 2010;1:122–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown MK, Evans JL, Luo Y. Beneficial effects of natural antioxidants EGCG and alpha-lipoic acid on life span and age-dependent behavioral declines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:620–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson MA, Shukitt-Hale B, Kalt W, Ingram DK, Joseph JA, Wolkow CA. Blueberry polyphenols increase lifespan and thermotolerance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2006;5:59–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lithgow GJ, White TM, Melov S, Johnson TE. Thermotolerance and extended life-span conferred by single-gene mutations and induced by thermal stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7540–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JV, Luo Y. Elevation of oxidative free radicals in Alzheimer's disease models can be attenuated by Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:287–300. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu YB, Dosanjh L, Lao L, Tan M, Shim BS, Luo Y. Cinnamomum cassia bark in two herbal formulas increases life span in Caenorhabditis elegans via insulin signaling and stress response pathways. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishii N, Fujii M, Hartman PS, Tsuda M, Yasuda K, Senoo-Matsuda N, et al. A mutation in succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b causes oxidative stress and ageing in nematodes. Nature. 1998;394:694–7. doi: 10.1038/29331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Royall JA, Ischiropoulos H. Evaluation of 2’,7’- dichlorofluorescin and dihydrorhodamine 123 as fluorescent probes for intracellular H2O2 in cultured endothelial cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;302:348–55. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]