A clathrin heavy chain participates in Nod factor signal transduction and infection thread formation in the leguminous symbiosis with rhizobia.

Abstract

Mechanisms underlying nodulation factor signaling downstream of the nodulation factor receptors (NFRs) have not been fully characterized. In this study, clathrin heavy chain1 (CHC1) was shown to interact with the Rho-Like GTPase ROP6, an interaction partner of NFR5 in Lotus japonicus. The CHC1 gene was found to be expressed constitutively in all plant tissues and induced in Mesorhizobium loti-infected root hairs and nodule primordia. When expressed in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana, CHC1 and ROP6 were colocalized at the cell circumference and within cytoplasmic punctate structures. In M. loti-infected root hairs, the CHC protein was detected in cytoplasmic punctate structures near the infection pocket along the infection thread membrane and the plasma membrane of the host cells. Transgenic plants expressing the CHC1-Hub domain, a dominant negative effector of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, were found to suppress early nodulation gene expression and impair M. loti infection, resulting in reduced nodulation. Treatment with tyrphostin A23, an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis of plasma membrane cargoes, had a similar effect on down-regulation of early nodulation genes. These findings show an important role of clathrin in the leguminous symbiosis with rhizobia.

The establishment of symbiotic relationships requires a complex molecular dialog between legumes and nitrogen-fixing rhizobia. Flavonoids released by legume roots trigger the synthesis and secretion of rhizobial nodulation factors (NFs), which are recognized by legume roots to activate a symbiosis signaling pathway that allows the rhizobia to enter root hairs and pass through the plant-derived infection threads (ITs). Eventually, rhizobia are released from ITs into symbiosomes of infected cells within the highly specialized plant organ, the root nodule. NF perception by root cells is mediated by two lysin motif-family receptor kinases, nodulation factor receptor1 (NFR1) and NFR5 in Lotus japonicus and Nod Factor Perception and Lysin motif domain-containing receptor-like kinase3 (LYK3) in Medicago truncatula (Limpens et al., 2003; Madsen et al., 2003; Radutoiu et al., 2003; Smit et al., 2007). NFR1 and NFR5 are required for the earliest physiological and cell responses to NFs, such as membrane depolarization, Ca2+ oscillations, and root hair deformation. Downstream of NFR1/NFR5 receptors, a series of genes has been identified to be required for successful nodulation. These genes play roles in NF signal transduction, transcription regulation, cytoskeleton rearrangement, cell wall degradation, and hormone homeostasis (Desbrosses and Stougaard, 2011; Oldroyd et al., 2011; Oldroyd, 2013). Two recent reports have shown that NFR1 and NFR5 interact with each other at the plasma membrane (Madsen et al., 2011) and that the two receptors could directly bind NFs at nanomolar concentrations, which is consistent with the concentration range of NFs required for the activation of symbiotic signaling responses (Broghammer et al., 2012). These studies have led to an NF ligand recognition model, which is also supported by the altered specificity of NF recognition in host plants through coexpression of L. japonicus NFR1 and NFR5 in M. truncatula (Radutoiu et al., 2007).

Endocytosis, a well-studied process in animal cells, is essential for regulation of protein and lipid compositions of the plasma membrane and removal of cargoes from the extracellular space. Endocytosis also occurs in plant cells, regulating plant growth and development as well as hormonal signaling and communication with the environment (Dhonukshe et al., 2007; Robert et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Sharfman et al., 2011; Adam et al., 2012). As in animal cells, clathrin-mediated endocytosis in plants takes place through clathrin-coated vesicles, which can be observed in highly active plant cells, such as the growing pollen tube and root hairs (Dhonukshe et al., 2007). Clathrin-coated vesicles are formed at the plasma membrane, where specific types of cargoes are recognized and packaged for internalization. The clathrin triskelion is composed of three clathrin H chains (CHCs) each binding to a single clathrin light chain (CLC) in the Hub domain. Clathrin triskelia can further interact, forming a polyhedral lattice that surrounds the vesicle (McMahon and Boucrot, 2011). The Hub domain comprises about 600 amino acid residues at the C terminus and is involved in mediating CHC self-assembly and association with CLCs (Liu et al., 1995; Ybe et al., 1999). Thus, overexpression of the Hub domain can have an inhibitory effect on clathrin-mediated endocytosis through competitive binding with the light chains or forming improper clathrin triskelia (Pérez-Gómez and Moore, 2007).

Endocytosis has been suggested to play a role in endosymbiosis between legumes and rhizobia. Electron microscopy studies have revealed the occurrence of numerous coated pits as well as smooth and coated vesicles along the IT membrane (Robertson and Lyttleton, 1982). NFs have been detected inside the root hairs, along ITs, and in the cytoplasm of infected root cells, suggesting that some aspects of the NF signaling pathway may proceed through an endocytosis process (Philip-Hollingsworth et al., 1997; Timmers et al., 1998). The M. truncatula flotillin-like proteins, FLOT2 and FLOT4, have been localized in the membrane microdomain and found to be required for IT initiation and nodule development (Haney and Long, 2010). Flotillins belong to a family of lipid raft-associated integral membrane proteins and are involved in a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway in mammalian cells (Glebov et al., 2006). This further highlights the importance of endocytic pathways in the evolution of IT-mediated entry of symbiotic bacteria. However, direct evidence for the regulation of the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis by clathrin-mediated endocytosis has not been reported.

We have previously identified the small Rho-like GTPase6 (ROP6) as an interacting protein of the NFR NFR5 (Ke et al., 2012). ROP GTPases in plants are known for their roles in the regulation of the cytoskeleton and vesicular trafficking (Nagawa et al., 2010). Here, we report CHC1 as an interactor of ROP6 and propose that clathrin-mediated endocytosis participates in the early stages of the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis.

RESULTS

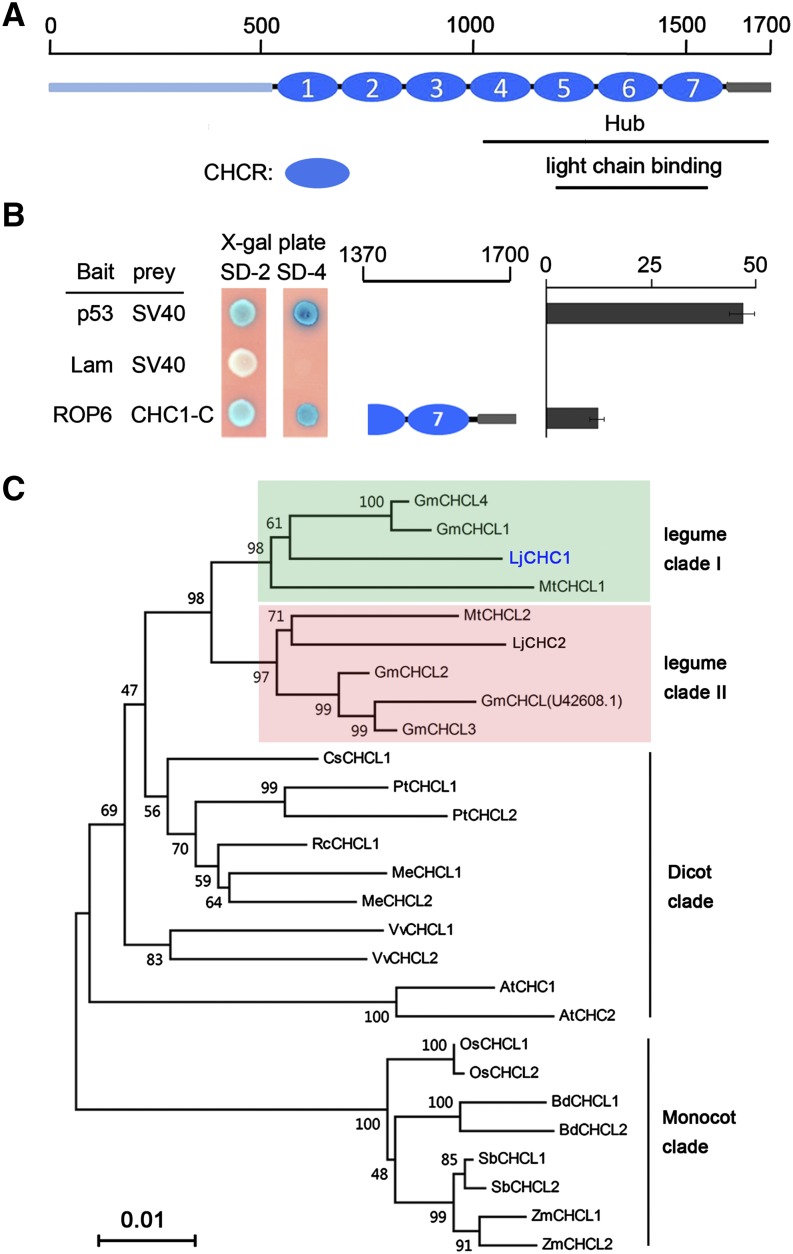

Identification of CHC1 as an Interactor of ROP6 in the Yeast Two-Hybrid System

Using ROP6 as bait to screen an L. japonicus root complementary DNA (cDNA) library for interaction proteins, we isolated four independent clones, which all were derived from the same gene encoding the CHC1 in L. japonicus (Fig. 1B). The isolated cDNA clones encode a C-terminal region of CHC1 consisting of only the last one and one-half of the clathrin heavy chain repeat (CHCR). LjCHC1 is present on chromosome 2 (chr2.CM0002.400.r2.m), and there is a paralogous gene on chromosome 6 (chr6.CM0302.70.r2.m) designated as LjCHC2. The full-length CHC1 cDNA contains a 5,103-bp open reading frame encoding a peptide of 1,700 amino acids with a molecular mass of 192.4 kD. Like other CHCs, CHC1 has multiple subdomains starting with an N-terminal domain and followed by linker, distal leg, knee, proximal leg, and trimerization domains (Ybe et al., 1999). The N-terminal domain folds into a seven-bladed β-propeller structure. The other domains form a superhelix of short α-helices composed of the smaller structural module CHCRs (Smith and Pearse, 1999). Seven CHCRs are presented in both CHC1 and CHC2 (Fig. 1A). CHC proteins are highly conserved among plant species (see sequence information in Supplemental Table S1), having an amino acid identity of over 90%. Two clades of CHC proteins can be clearly distinguished in legume plants, and only one clade can be distinguished in nonlegumes (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Identification of CHC1 as an interactor of ROP6. A, Schematic illustration of functional domains of CHC1. The full-length CHC1 has 1,700 amino acids. CHC1-Hub and light-chain BDs are indicated at the corresponding regions. Blue circles indicate the seven CHCR motifs. B, Isolation of CHC1 as an interactor of ROP6. Interacting colonies encoded the C-terminal 331 amino acids of CHC1. The interaction was strong as indicated by the β-galactosidase activity assay. Values represent means ± se of interaction strength of three individual colonies of each interaction combination. Combinations of p53/SV40 and lam/SV40 served as positive and negative controls, respectively. C, Phylogenetic tree of plant clathrin heavy chain-like proteins (CHCLs). Clades containing LjCHC1 and LjCHC2 are indicated by green and pink shades, respectively. There are two CHC clades in legumes and only one in nonlegumes. Bootstrap values (%) obtained from 1,000 trials were marked at the branch nodes. SD/-2, SD/-Trp/-Leu; SD/-4, SD/-Trp/Leu/-His/-Ade.

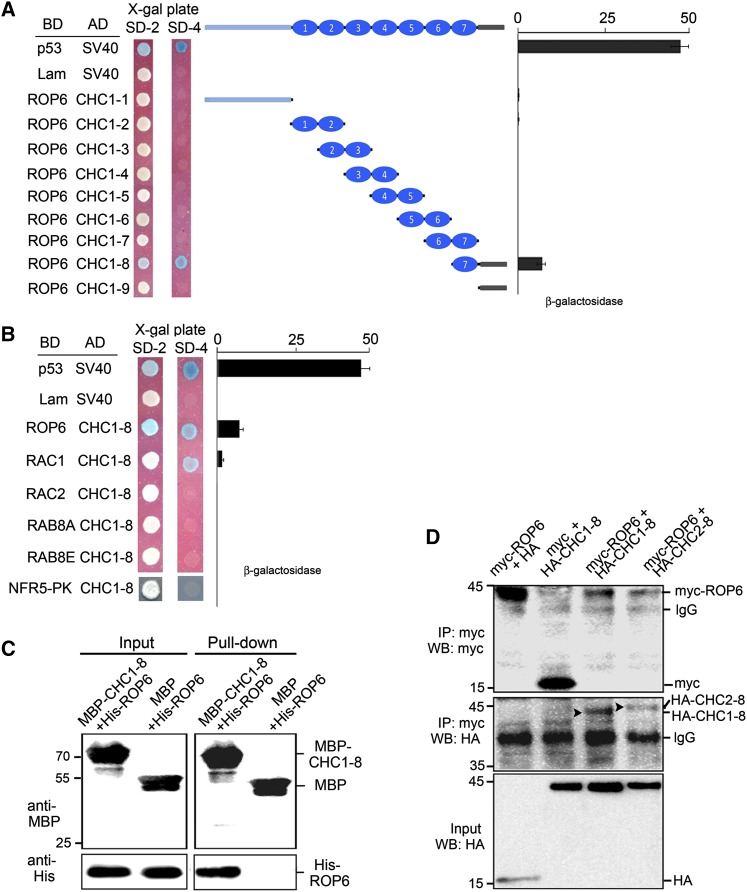

Requirement of CHCR7 for the Interaction with ROP6

The four initial CHC1 clones isolated from the library screen contained only a partial CHCR6, a complete CHCR7 motif, and a C-terminal tail (Fig. 1B). To test if other CHCRs might also mediate the interaction with ROP6, we performed interaction tests in the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) two-hybrid system. A series of truncated proteins of CHC1 fused to the Gal4 activation domain (AD) were expressed in yeast cells. These proteins were tested for the interaction with ROP6 fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain (BD; Fig. 2A). The interactions were quantitatively measured by the β-galactosidase activity assay. The results showed that the only clone that interacted with ROP6 was CHC1-8, which contained a complete CHCR7 and a C-terminal tail (Fig. 2A), suggesting that other CHCR motifs are not required for the interaction with ROP6.

Figure 2.

Interaction between CHC1 and ROP6. A, Dissection of functional domains of CHC1 required for interaction with ROP6. A series of truncated CHC1 proteins was tested for interaction with ROP6. The interaction strength was assessed by the β-galactosidase activity either on plates containing X-gal (80 μg mL−1; SD/-2/X-gal and SD/-4/X-gal) or by quantification assay. Values represent means ± se of interaction strength of three individual colonies of each interaction combination. Combinations of p53/SV40 and lam/SV40 served as positive and negative controls, respectively. B, Specificity of the interaction between CHC1 and ROP6. Homologs of ROP6 from L. japonicus were tested for potential interactions with CHC1-8. LjRAC1 showed weak interaction with ROP6. C, In vitro protein-protein interaction assay between CHC1-8 and ROP6. The positions of His-ROP6, MBP, and MBP-CHC1-8 are indicated. Proteins retained on the affinity resins were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with HRP-conjugated anti-MBP antibody (top) or anti-His antibody (bottom). D, Coimmunoprecipitation of CHC1-8 and ROP6. Myc-tagged ROP6 and HA-tagged CHC1-8 or CHC2-8 proteins were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells. The combinations of ROP6 with the empty HA tag and CHC1-8 with empty myc tag served as negative controls. The input samples were probed with anti-HA antibody (bottom). Antimyc antibody was used for immunoprecipitation. The protein products were analyzed on western blots (WBs) using HRP-conjugated antimyc antibody (top) or anti-HA antibody (middle). SD/-2, SD/-Trp/-Leu; SD/-4, SD/-Trp/Leu/-His/-Ade.

To assess the specificity of the CHC1/ROP6 interaction, we used other known small GTPases from L. japonicus (LjRAC1, LjRAC2, LjRAB8A, and LjRAB8E; Supplemental Fig. S1; Borg et al., 1997) to replace ROP6. The results showed that RAC2, RAB8A, and RAB8E do not interact with CHC1, whereas the interaction between RAC1 and CHC1 is very weak (Fig. 2B), suggesting a specific interaction between CHC1 and ROP6. In yeast cells, CHC1-8 was not able to interact with the protein kinase domain of NFR5 (NFR5-PK; Fig. 2B). The interaction between CHC1 and ROP6 was also confirmed by swapping the BD and AD domains of Gal4 between the interaction partners (Supplemental Fig. S2A). It is worth noting that the weak interaction between RAC1 and CHC1-8 (Fig. 2B) disappeared when the BD and the AD domains were swapped (Supplemental Fig. S2A). For all positive interactions in the yeast two-hybrid system, we performed appropriate controls that would eliminate potential self-activation of the bait vectors (Supplemental Fig. S2B). All recombinant proteins were expressed properly in yeast cells as shown by western-blot analysis (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Thus, failed interactions were not caused by the lack of protein expression.

Interaction between CHC1 and ROP6 in Vitro and in Planta

The interaction between CHC1 and ROP6 was confirmed by in vitro protein pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation assays. CHC1-8 was expressed as a recombinant protein fused to the C terminus of maltose binding protein (MBP) and was pulled down on amylose resins. Purified His-tagged ROP6 protein was then incubated with MBP-CHC1-8 absorbed on amylose resins. MBP alone was used as a negative control. As shown in Figure 2C, ROP6 was pulled down on the MBP-CHC1-8 resins, suggesting a protein-protein interaction between CHC1 and ROP6.

For comparison of CHC1 and CHC2, we also expressed hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged CHC2-8 that contained a similar peptide region of CHC2 as in CHC1-8. For coimmunoprecipitation assays, HA-tagged CHC1-8 and CHC2-8 were coexpressed with myc-tagged ROP6 in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Proteins precipitated with the myc antibody were detected using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-HA antibody. The results showed that both CHC1 and CHC2 interact with ROP6 (Fig. 2D). No interactions were detected in the controls that coexpressed either CHC1 and the empty vector or the empty vector and ROP6.

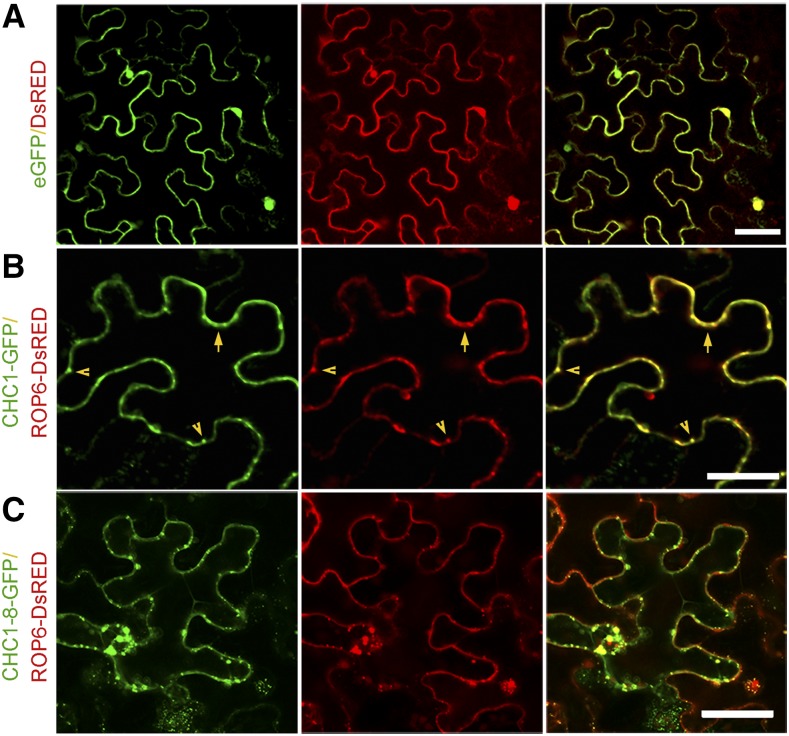

Competition of CLC with ROP6 for Binding of CHC1

The CHC-Hub domain (corresponding to residues 1,088–1,700 in CHC1) can self-trimerize and bind CLC (Fig. 1A). Deletion mutagenesis of the Hub fragment revealed that the shortest region for CLC binding is the residues 1,213 to 1,522 of bovine CHC (Liu et al., 1995), corresponding to residues 1,227 to 1,537 of LjCHC1 (Fig. 1A). This CLC binding site overlaps with the interacting region of CHC1 with ROP6. We asked if CLC had a competitive effect on the interaction of CHC1 with ROP6. To test the possible effect of light-chain binding to the interaction of CHC1/ROP6, we cloned LjCLC1 and LjCLC2, which were derived from the gene loci LjT24M21.40.r2.a and chr3.CM0160.80.r2.m, respectively. The results showed that both CLCs interacted with CHC1-8 (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. S2C). Because CLC1 interacted with CHC1 more intensively, it was used further for testing competitive binding of CHC1-8 with ROP6 in vitro. For this, ROP6 protein was first pulled down on amylose resins containing MBP-CHC1-8. The resulting MBP-CHC1-8-ROP6 complex was incubated with different concentrations of CLC1. When the concentration of CLC1 was increased, the amount of ROP6 on the resins was reduced, suggesting that CLC1 proteins may compete for binding to CHC1.

Figure 3.

Competition of CLC with ROP6 for binding with CHC1. A, CHC1-8 interacted with CLCs CLC1 and CLC2. B, Competitive displacement of ROP6 from CHC1-8 by CLC1. The amount of His-ROP6 retained on MBP-CHC1-8 resins decreased as the concentration of His-CLC1 increased. Arrowhead indicates MBP-CHC1-8 protein purified with MBP resins. As positive controls, purified His-CLC1 and His-ROP6 were loaded to the right two lanes of the gel, showing the sites of CLC and ROP6 in western-blot analysis.

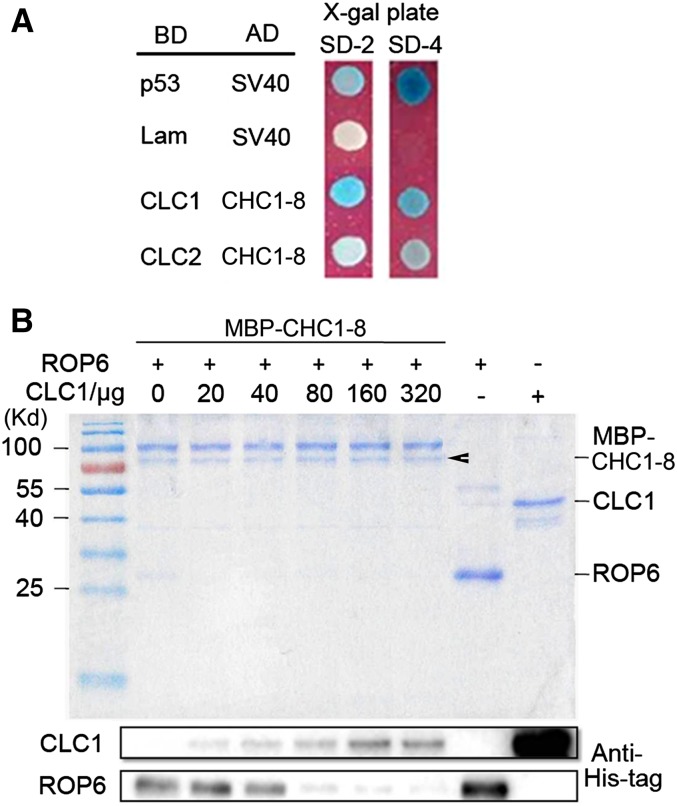

Colocalization of CHC1 and ROP6

We coexpressed Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein (DsRED)-tagged ROP6 with GFP-tagged CHC1 in N. benthamiana leaf cells. ROP6-DsRED was colocalized with CHC1-GFP at the cell circumference and within punctate structures adjacent to the plasma membrane (Fig. 4B). We then replaced CHC1-GFP with a truncated CHC1-8-GFP, which presented a stronger fluorescence signal. When ROP6-DsRED was coexpressed with CHC1-8-GFP, ROP6 could better colocalize with CHC1-8 (Fig. 4C). Fusion proteins expressed in N. benthamiana leaves were detected by western-blot analysis (Supplemental Fig. S3B).

Figure 4.

Subcellular colocalization of CHC1 and ROP6 in N. benthamiana cells. Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells harboring appropriate plasmids were used to infect N. benthamiana leaf cells. The GFP (left) and DsRED (center) fluorescence images were merged. Colocalization signals are shown in yellow (right). A, Nuclear and cytoplasm localizations of free enhanced GFP (eGFP) and DsRED expressed from the control vector. B and C, Colocalization at the cell circumference (arrows) and within punctate structures (arrowheads) of CHC1-GFP and ROP6-DsRED (B) or CHC1-8-GFP and ROP6-DsRED (C). Bars = 50 μm.

Subcellular Localization of CHC1 in Mesorhizobium loti-Infected Cells

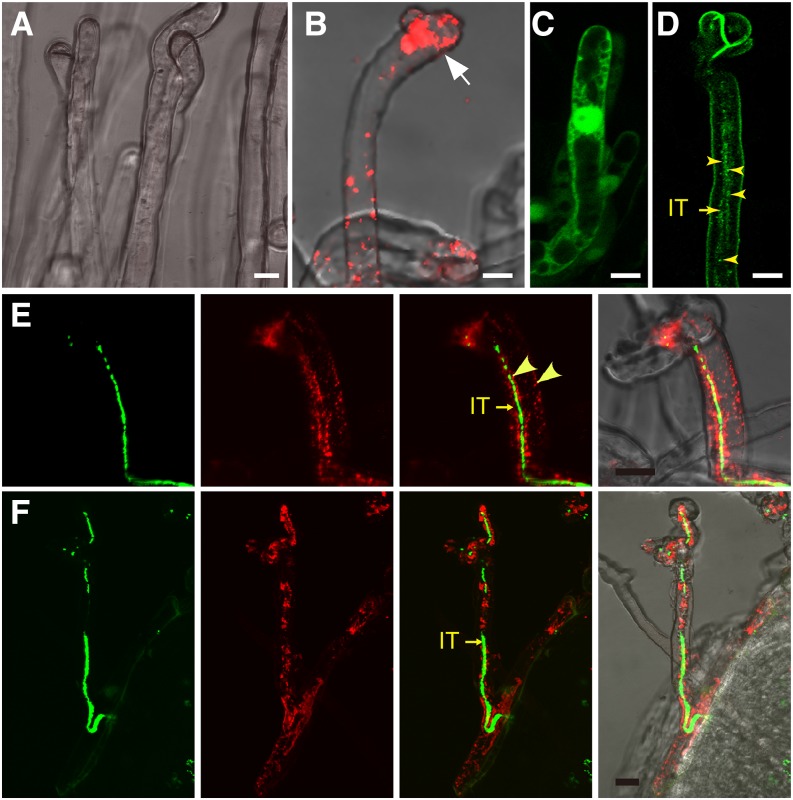

Early electron microscopy studies have shown the presence of vesicles along the ITs in infected root hairs (Robertson and Lyttleton, 1982). We performed in situ immunolocalization using CHC antibody that reacted with both LjCHC1 and LjCHC2 by western-blot analysis (Supplemental Fig. S3C). CHC proteins were found at the cytosolic punctate structures. They presumably corresponded to the endocytic vesicles and endosomes, which were present abundantly in the infection pocket (IP; Fig. 5B) and surrounding the ITs (Fig. 5, E and F). The immunofluorescence signal was stronger in the infected root hairs than in noninfected root hairs, indicating an elevated level of CHC proteins in infected root hairs (Fig. 5F). This is consistent with the enhanced gene expression of CHC1 as indicated by the promoter-GUS assay (Fig. 6L; Supplemental Fig. S4I). The control analyzed in the absence of the primary antibody showed no fluorescence signals (Fig. 5A). These data suggest a role of clathrin in the early symbiotic signal exchange during the initiation and development of ITs. We also expressed 35S:CHC1-GFP in transgenic L. japonicus hairy roots, which revealed a localization pattern similar to that observed by immunolocalization (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Subcellular localization of CHC1 in M. loti-infected cells. A, B, E, and F, Roots of L. japonicus were inoculated with M. loti constitutively expressing GFP (green channel). Seven dpi, the roots were collected and reacted with anti-CHC antibody followed by detection using second antibody labeled with Cy3 (red channel). The root sample that was analyzed in the absence of the primary antibody served as the negative control (A). Cytoplasmic punctate structures were found in the IP (white arrow in B), surrounding the IT, and at the plasma membrane of the infected root hair (arrowheads in E). ITs filled with GFP-labeled rhizobial cells (green) are indicated by arrows (E and F). C and D, Green fluorescence was found in the nucleus and cytoplasm of the root hair expressing free enhanced GFP (C) and the punctate structures surrounding the IT in the root hair expressing 35S:CHC1-GFP (D). Bars = 10 μm.

Figure 6.

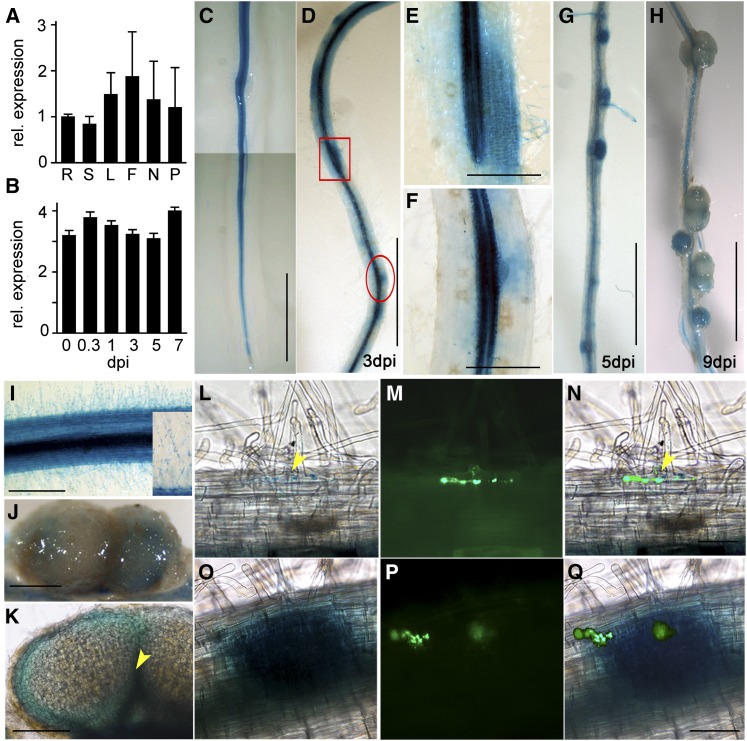

Temporal and spatial expression of LjCHC1. A, qRT-PCR assay showing constitutive expression of CHC1 in various tissues of the plant. Total RNA was extracted from roots (Rs), stems (Ss), leaves (Ls), flowers (Fs), nodules (Ns), and pods (Ps) of wild-type L. japonicus plants. RNA was also isolated from roots inoculated 6 h (or 0.3 d) and 1, 3, 5, and 7 dpi with M. loti. Roots before inoculation (0 dpi) served as a control. Relative expression levels (rel. expression) of CHC1 were measured by qRT-PCR. Means ± se of three biological repeats are presented. B, qRT-PCR assay showed no induced expression of CHC1 in roots after M. loti inoculation. C to H, Histochemical GUS staining of stable transgenic plants expressing LjCHC1pro:GUS. Plant tissues were stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-glucuronic acid for less than 4 h to avoid nonspecific staining. Constitutive and high expression of CHC1 was observed in roots (C) and root hairs (I). High levels of GUS staining were observed in the cortical region of roots (D), nodule primordia (G), and developing nodules (H) 3, 5, and 9 dpi. Magnified longitudinal section of the boxed region in D showing expression of CHC1 in root hairs of the rhizobial infected region (E). CHC1 expression was also elevated in the dividing cortical cells that eventually develop to nodule primordia (E). Magnified longitudinal section of the circled region in D shows high expression of CHC1 in the lateral root primordia (F). J and K, In mature nodules, the expression of CHC1 was restricted to the vascular tissues (arrowhead). L to N, CHC1 was expressed in a root hair cell where an IT was developed (L). The presence of ITs was indicated by GFP, which was expressed constitutively by an M. loti strain MAFF303099 (M). Superimposed image (N) of L and M. O to Q, CHC1 was expressed in dividing cortical cells before rhizobial cells were released from the ITs (O). The ITs were visualized by the GFP fluorescence (P). Superimposed image (Q) of O and P. Bars = 10 mm (in C, D, G, and H) and 1 mm (in E, F, J, K, N, and Q.

Temporal and Spatial Expression of LjCHC1

We extracted RNA from various plant organs, including roots infected with M. loti, and measured the expression levels of LjCHC1 by quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR. CHC1 was found to be constitutively and highly expressed in roots, stems, leaves, flower, and nodules, suggesting a housekeeping role of this gene in plant growth and development (Fig. 6A). After inoculation with M. loti, the expression levels of CHC1 in roots were not altered significantly (Fig. 6B). Some specific expression patterns that are closely related to symbiotic interactions cannot be found by testing RNA levels of whole-root tissues. Thus, we generated stable transgenic L. japonicus lines expressing the reporter GUS gene under the control of the native CHC1 promoter. The expression of CHC1 was high in stigmas, stamens, and pods (Supplemental Fig. S4), implying an important role of CHC1 in plant reproduction. In uninoculated roots, CHC1 was uniformly expressed in roots and root hairs (Fig. 6I). After inoculation with M. loti, CHC1 was highly expressed in the root hairs and epidermal cells surrounding the infection sites (Fig. 6, E and L–N; Supplemental Fig. S4). During nodule development, CHC1 was highly expressed in dividing cortical cells and the vascular system of the root (Fig. 6E; Supplemental Fig. S4). It is notable that the expression of CHC1 was highly enhanced in dividing cortical cells before rhizobia entered these cells (Fig. 6, O–Q). In fully developed nodules, CHC1 expression was reduced and restricted to the vascular tissues and uninfected cortical cells (Fig. 6, H, J, and K).

Impaired Nodule Development by Expression of CHC1-Hub in Stable Transgenic Plants

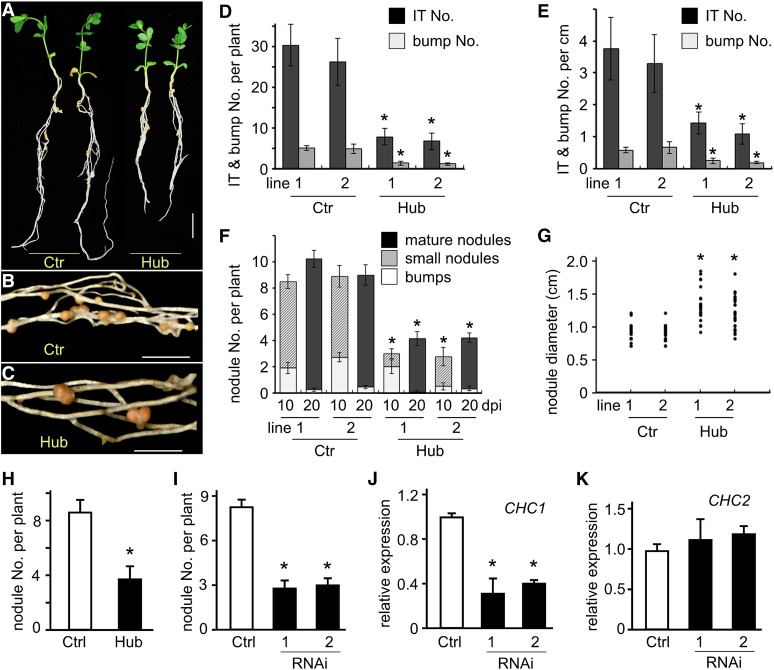

Seven stable transgenic L. japonicus plants expressing the CHC1-Hub domain under the enhanced Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter were generated and characterized. Plants transformed with the pCAMBIA1301 empty vector served as a control. All T1 transgenic lines exhibited impaired reproductive capacity (Supplemental Fig. S5). This is consistent with the proposed role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in pollen tube growth and embryogenesis (Zhao et al., 2010; Kitakura et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2013). As a result, very limited amounts of transgenic seeds could be obtained from these transgenic plants. The expression of CHC1-Hub in transgenic plants was confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR (Supplemental Fig. S6D). Two independent T1 transgenic lines, CHC1-Hub lines 1 and 2, and 10 to 20 plants were chosen for characterization of the root and nodule development. Root length was reduced by approximately 50% in CHC1-Hub lines compared with the control 3 d after seedlings were transplanted to vermiculite before rhizobial inoculation (Supplemental Fig. S6, A and B). The root hairs in CHC1-Hub lines were nearly 2-fold longer than those of the control (Supplemental Fig. S6C). The nodule number of CHC1-Hub lines was significantly lower than that of the control at both 10 (n = 10, 11, 10, and 12 for control lines 1 and 2 and Hub lines 1 and 2, respectively) and 20 (n = 24, 18, 12, and 12 for control lines 1 and 2 and Hub lines 1 and 2, respectively) d postinoculation (dpi; Fig. 7, A and F). The nodule diameter was increased from 0.91 cm in the control to 1.26 cm in CHC1-Hub lines at 20 dpi (Fig. 7, B, C, and G), probably as a result of the reduced nodule number in CHC1-Hub lines.

Figure 7.

Effect of CHC1-Hub expression and CHC1-RNA interference (RNAi) on rhizobial infection and nodulation. Stable transgenic plants (Hub) of L. japonicus expressing CaMV 35S:CHC1-Hub were generated by A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Transgenic plants expressing the empty vector served as a control (Ctr). Two representative lines from each group are characterized. Values in D to F represent means ± se of 10 to 20 plants. A, Plants were growing in nitrogen-free soil for 20 dpi with M. loti. Note that the CHC1-Hub plants were smaller and formed fewer nodules compared with the control. Bar = 10 mm. B and C, The CHC1-Hub plants formed fewer but larger nodules (C) than the control plants (B). D and E, The numbers of ITs and bumps per plant (D) and per centimeter of root (E) were significantly lower (P < 0.001) in the CHC1-Hub lines than the control plants when observed 7 dpi with M. loti. F, The number of nodules per plant was reduced significantly (P < 0.001) in the CHC1-Hub lines compared with the control plants 10 and 20 dpi with M. loti. G, Nodule diameter (centimeters) was significantly larger (P < 0.001) in the CHC1-Hub lines than the control plants. The diameters of 40 randomly selected nodules from 10 plants per transgenic line were recorded. H, Nodule number per plant on transgenic hairy roots expressing the empty vector (n = 41) and 35S:CHC1-Hub (n = 35) 3 weeks after inoculation with M. loti. I, Nodule number per plant on transgenic hairy roots expressing the empty vector (n = 33), CHC1-RNAi-1 (n = 28), and CHC1-RNAi-2 (n = 26) 3 weeks after inoculation with M. loti. J and K, Reduction of the CHC1 but not CHC2 transcript in transgenic hairy roots expressing either CHC1-RNAi-1 or CHC1-RNAi-2 construct. Ctrl, Control; *, statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) between treatments and controls as determined by Student’s t test.

Reduction in Rhizobial Infection Events by Expression of CHC1-Hub in Stable Transgenic Plants

We also tested whether decreased nodulation was a result of defective rhizobial infection in CHC1-Hub transgenic lines. Ten individual plants of each line were inoculated with rhizobia constitutively expressing GFP and observed 7 d after inoculation. The results showed that, although rhizobia could normally infect root hairs of CHC1-Hub lines, the numbers of ITs and bumps per plant were significantly reduced (Fig. 7D). Additional examination on the frequencies of infection initiation and densities of IPs in the CHC1-Hub line 1 revealed a similar defect in rhizobial infection in this Hub line (Supplemental Fig. S7B). Because the roots of CHC1-Hub transgenic lines were shorter than the control expressing the empty vector, we compared the numbers of IPs, ITs, and bumps per centimeter of roots. The result showed that the densities of IPs, ITs, and bumps were also significantly reduced by CHC1-Hub expression (Fig. 7E; Supplemental Fig. S7C), suggesting that the impaired symbiosis phenotype was not caused directly by the reduced root length of CHC1-Hub lines. In conclusion, expression of CHC1-Hub had deleterious effects on not only root development but also, rhizobial infection and IT growth, which ultimately led to reduction in the numbers of ITs and nodules per plant.

Reduction in Nodule Numbers by Expression of CHC1-Hub and CHC1 RNA interference in Transgenic Hairy Roots

To avoid the lethal effect of CHC1-Hub expression on reproduction of transgenic plants, we generated a chimeric plant with transformed roots attached to an untransformed shoot (Kumagai and Kouchi, 2003; Limpens et al., 2004). CHC1-Hub was expressed under the enhanced CaMV 35S promoter in transgenic L. japonicus hairy roots. After hairy roots were generated, a root tip of 2 to 3 mm was excised for GUS staining. Two GUS-positive hairy roots were preserved on each plant, and all of the GUS-negative hairy roots were removed. Nodule numbers were recorded 3 weeks after the transgenic plants were transplanted to the nitrogen-free growth soil and inoculated with M. loti. The nodule number in hairy roots expressing CHC1-Hub (n = 35) was reduced by about 50% compared with the control hairy roots expressing the empty vector (n = 41; Fig. 7H). We also examined the suppressive effect of CHC1 expression on nodulation by expressing two RNAi constructs targeting the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) region (RNAi-1) and the 3′-UTR region (RNAi-2) of the CHC1 mRNA. Hairy roots from four individual transgenic plants expressing empty or RNAi vectors were randomly selected for total RNA isolation and qRT-PCR assay. The mRNA levels of CHC1 in transgenic hairy roots were reduced by over 60% as measured by qRT-PCR, whereas CHC2 mRNA was not affected by the expression of CHC1 RNAi (Fig. 7, J and K). The results showed similar reduction in nodule numbers by approximately 60% in CHC1-RNAi-1 (n = 28) and CHC1-RNAi-2 (n = 26) roots (Fig. 7I). The observation of the reduction in nodule number by expression of CHC1-Hub and CHC1-RNAi could be reproduced in repetitive experiments, avoiding the variation of the hairy root system.

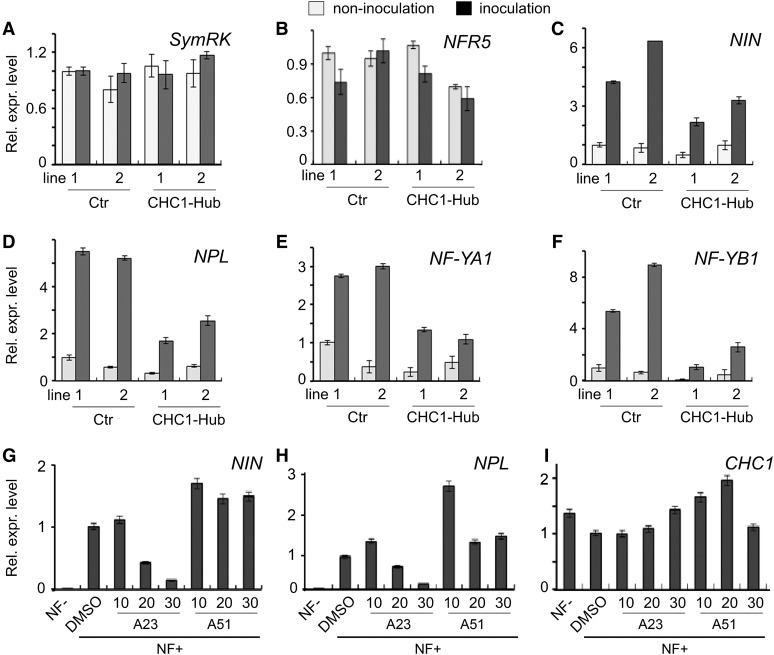

Suppression of Early Nodulation Genes by Expression of CHC1-Hub

We further tested whether the expression of early nodulation genes, including NODULE INCEPTION (NIN), nodulation pectate lyase (NPL) nuclear factor-YA1 (NF-YA1), and NF-YB1, was affected in CHC1-Hub transgenic lines. Symbiosis Receptor-like Kinase (SymRK) gene and NFR5 are known to be expressed constitutively during the nodulation process (Stracke et al., 2002) and were used as controls in this work. NIN is a transcription regulator that acts early in rhizobial infection and nodule initiation (Schauser et al., 1999). NPL is a nodulation pectate lyase that is required for rhizobia to penetrate the cell wall and initiate formation of ITs (Xie et al., 2012). NF-YA1 and NF-YB1 are two subunits of the NF-Y, which are expressed in root nodule primordia and play an important role in cortical cell division (Soyano et al., 2013). Total RNA was extracted from roots 2.5 dpi, and qRT-PCR was performed to measure the expression levels of each gene. The results showed that all of the selected genes, except SymRK and NFR5 (Fig. 8, A and B), were induced by rhizobial inoculation as expected (Fig. 8, C–F). The expression levels of NIN, NPL, NF-YA1, and NF-YB1 were suppressed by CHC1-Hub expression (Fig. 8, C–F), which was consistent with the results that CHC1-Hub impaired IT initiation and nodulation. We also used tyrphostin A23 (A23), an inhibitor of cargo recruitment into clathrin-coated vesicles from the plasma membrane (Dhonukshe et al., 2007; Irani and Russinova, 2009), to test if clathrin-mediated endocytosis played a role in the induction of early nodulation genes. Tyrphostin A51 (A51), a biologically inactive structural analog, was used as a negative control. Pretreatment of roots with the inhibitor reduced the induction of early nodulation genes in response to a treatment with NF (Fig. 8, G–I) but did not influence the background expression of these genes in roots without NF treatment (Supplemental Fig. S8). At high concentration (30 μm) of A23, the NF-triggered up-regulation of early nodulation genes was blocked. These results indicate the NF-triggered gene induction is dependent on clathrin-mediated endocytosis of plasma membrane proteins.

Figure 8.

Effect of CHC1-Hub expression and the endocytosis inhibitor tyrphostin A23 on early nodulation gene expression. A to F, Suppressive expression of the early nodulation genes NIN, NPL, NF-YA1, and NF-YB1 (C–F) in stable transgenic lines expressing CHC1-Hub. RNA was isolated from roots of four to six plants for each line. Two transgenic lines of the control expressing the empty vector (Ctr) and two transgenic lines expressing CHC1-Hub were compared for the relative expression levels of genes. Plants were grown in the presence (black) or absence (gray) of M. loti for 2.5 d. Constitutive expression of SymRK and NFR5 during nodulation served as control genes (A and B). Relative expression levels were normalized against the internal control of the ATPase gene. G to I, Suppressive effect of the endocytosis inhibitor tyrphostin A23 (A23) on the expression of NIN and NPL. The constitutive expression of the CHC1 gene served as a control. Tyrphostin A51 (A51), a structural analog with no biological activity on endocytosis, served as a negative control. L. japonicus seedlings were treated with 10, 20, and 30 μm A23 or A51 followed by application of a crude NF extract to induce the early nodulation genes. Treatment of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a solvent for A23 and A51, and seedlings without NF treatment (NF−) served as controls. Values were calculated relative to the DMSO control. The inhibition of early nodulation gene expression by A23 was similar in another experimental replicate. Bars represent sds for three technical replicates. Rel. expr. level, Relative expression level.

Phenotypes of chc+/− Heterozygous Plants

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) contains two CHC genes that are partially redundant, and the double-mutant chc1/chc2 showed gametophytic lethality (Kitakura et al., 2011). We obtained two L. japonicus mutant lines, P0665 and 30013963, both of which contained a transposon insertion in the exon of CHC1 (Supplemental Fig. S9; Fukai et al., 2012; Urbański et al., 2012). Heterozygous chc1+/− plants exhibited severe defects in reproduction. The pods of P0665 chc1+/− mutant plants were shorter and contained fewer seeds than those of the wild-type lines (Supplemental Fig. S8C). This reproductive phenotype was similar to that of CHC1-Hub transgenic lines (Supplemental Fig. S5). No homozygous seedlings were identified from 96 progenies of P0665 chc1+/− mutant plants, implying lethality in gametogenesis or seed development. Although the chc1+/− heterozygous plants exhibited severe defects in reproduction, no vegetative growth and altered nodulation phenotype were observed for the chc1+/− heterozygous plants (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

LjCHC1 Is a Conserved Protein with a Unique Role in Symbiosis

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is a very well-conserved process in animal and plant cells and involves highly homologous protein components, including CHC, CLC, adaptor protein complex2, and the eight-core component protein complex, TPLATE (Pérez-Gómez and Moore, 2007; Kitakura et al., 2011; Di Rubbo et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013a, Gadeyne et al., 2014). CHCs are highly conserved (>90% similarity) in the plant kingdom. Phylogenetic analysis showed the existence of two conserved clades of CHCs in legume plants but only one in nonlegumes (Fig. 1C). It is possible that paralogs of CHCs in legume plants may partially evolve to carry out a unique feature of leguminosae (for instance, symbiotic relationships with rhizobia). LjCHC1 and LjCHC2 share 93% identity in the CHC1-8/CHC2-8 region. ROP6 was found to interact with both CHC1 and CHC2 in plant cells as shown in the coimmunoprecipitation assay, suggesting that there may be functional redundancy between CHC1 and CHC2 in association with ROP6. The peptide region responsible for the interaction with ROP6 was mapped to the C terminus of LjCHC1 containing a CHCR7 and the C-terminal tail (Fig. 2A). It has been shown that the N-terminal domain of CHC is a seven-blade β-propeller and critical for the interaction with multiple adaptor molecules (Smith and Pearse, 1999). The N-terminal domain is oriented toward the plasma membrane in coated pits and responsible for adaptor-receptor recruitment to the coated pits. However, ROP6 interacts with the C-terminal region, which overlaps with the CLC binding site (Figs. 2A and 3A; Supplemental Fig. S2A). The competition analysis in vitro showed that CLC1 competitively inhibits the interaction between ROP6 and CHC1 by direct interaction with CHC1 (Fig. 3B). CLC has been shown to be required in vivo for efficient trimerization and clathrin assembly (Huang et al., 1997). In addition, CHC1 did not interact directly with NFR5 in yeast cells (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. S2A). We also examined the formation of a possible heterotrimeric complex of NFR5, ROP6, and CHC1 at the plasma membrane. These three proteins were coexpressed in N. benthamiana cells, and coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed. Preliminary data on the coimmunoprecipitation assays did not suggest the formation of such a trimeric protein complex (data not shown). Therefore, ROP6 probably does not participate in the assembly of the clathrin lattice complex that is destined to general clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Instead, ROP6 may play a role in recruiting CHC1 monomer from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane, thereby promoting endocytosis of plasma membrane proteins. ROP6 is ultimately removed from the clathrin complex through competition of the binding site with CLC1. This hypothesis is also partially supported by the colocalization analysis of ROP6 and CHC1 that showed the colocalization of the two proteins at the cell circumference as well as the punctate structures in the cytoplasm or the vicinity of the plasma membrane (Fig. 4, B and C). ROP proteins are Rho-like GTPases that control multiple developmental processes in plants (Li et al., 2001). They have previously been reported as regulators for clathrin-dependent endocytosis of auxin efflux carriers PIN-FORMED (PIN) proteins at the plasma membrane in Arabidopsis (Chen et al., 2012; Nagawa et al., 2012). The signaling module auxin-AUXIN BINDING PROTEIN1-ROP6/ROP-interactive CRIB motif-containing protein1-clathrin-PIN1/PIN2 has been proposed as a shared component of the feedback regulation of auxin transport during both root and aerial development. Whether ROPs regulate clathrin-mediated endocytosis of PINs through direct interaction with CHC in Arabidopsis has not been tested. The nodule sizes were larger in CHC1-Hub plants than in the control (Fig. 7G), which could be simply a consequence of the reduced number of nodules in CHC1-Hub plants. Another possible explanation is that the auxin pathway may be altered in the nodules (Suzaki et al., 2012, 2013), because the redistribution of the auxin efflux carrier PINs is known to be mediated by clathrin (Dhonukshe et al., 2007).

LjCHC1 Is Required for Reproduction and Symbiosis

Clathrin has been known to be required for plant growth, development, and reproduction (Zhao et al., 2010; Kitakura et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2013). The chc1+/− heterozygous mutant lines characterized in this work exhibited normal plant growth and development but had defects in reproduction. No homozygous seeds could be obtained, suggesting that CHC1 is required for plant reproduction. Stable transgenic plants expressing CHC1-Hub, a dominant negative form that has widely been used to interfere with clathrin-mediate endocytosis, also exhibited similar reproductive defects as well as other nonsymbiotic phenotypes (Supplemental Figs. S5 and S6). Promoter-GUS analysis of CHC1pro:GUS (Supplemental Fig. S4, A–F) also supported the observation of requirements of CHC1 in plant growth and reproduction. In addition to the conserved nonsymbiotic phenotypes, plants expressing CHC1-Hub also triggered prominent symbiotic defects in nodulation. The CHC1-Hub plants formed fewer IPs, ITs, and nodules (Fig. 7; Supplemental Fig. S7). This conclusion is also supported by the high expression of the CHC1 gene in M. loti-infected root hairs and the in situ immunolocalization of CHC in IPs and surrounding ITs (Figs. 5 and 6L; Supplemental Fig. S4I). The expression of early nodulation genes, including NIN, NPL, NF-YA1, and NF-YB1, was found to be suppressed in the CHC1-Hub plants (Fig. 8, C–F), indicating a crucial role of CHC1 in the NF signaling pathway and nodule development. A role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in induction of NF-responsive genes is also directly supported by the chemical inhibition assay (Fig. 8, G and H). Tyrphostins are Tyr analogs developed as inhibitors of Tyr kinases. Tyrphostin A23 but not other tyrphostins, such as A51, is able to inhibit the clathrin-mediated pathway in plants. Therefore, A51 is usually used as a negative control for the treatment of A23. However, it increased the expression of NIN and NPL upon inoculation with NF (Fig. 8, G and H). The results could be reproduced by several experimental replicates, suggesting a potential effect of A51 on plant cells that had not been found before. It also cannot be entirely excluded that A23 may also affect other processes. However, the suppressed expression of NF-responsive genes (NIN and NPL) together with the CHC1-Hub effects on IT initiation implicate the involvement of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in the leguminous symbiosis with rhizobia.

Internalization of Plasma Membrane Proteins in Plants

Endocytosis is an essential process by which eukaryotic cells internalize exogenous material or signaling molecules at the cell surface. In plant cells, clathrin-dependent endocytosis constitutes the predominant pathway for constitutive internalization of plasma membrane proteins (Dhonukshe et al., 2007). Endocytosis-mediated signaling of receptors has been described for several plant receptors, including BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE1 (Kinoshita et al., 2005), FLAGELLIN-SENSING2 (Chinchilla et al., 2007), CLAVATA1 (Ohyama et al., 2009), and the fungal elicitor ethylene-inducing xylanase receptor2 (Ron and Avni, 2004; Bar and Avni, 2009). A potential link between NFR5 and clathrin implies the possibility of endocytosis of NFRs. Similar implication was also reported in the vesicle-like localization of LYK3 (an ortholog of NFR1) protein (Moling et al., 2014). However, both need to be shown in additional research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Bacterial Strains

Plants of Lotus japonicus (Handberg and Stougaard, 1992; Kawaguchi et al., 2005) ‘Miyakojima MG-20’ used for nodulation assays were grown in a mixed soil medium containing perlite and vermiculite at a 1:1 volume ratio supplied with a one-half-strength Broughton and Dilworth (B&D) nitrogen-free medium in growth cabinets with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle at 22°C ± 1°C. L. japonicus ecotype Gifu-129 mutant seeds P0665 and 30013963 were provided by the Japanese National BioResource Project (http://www.legumebase.brc.miyazaki-u.ac.jp/) and the Centre for Carbohydrate Recognition and Signaling (http://users-mb.au.dk/pmgrp/), respectively. Plants of Nicotiana benthamiana were grown in nutrient soil in growth chambers with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle at 26°C. Plants were inoculated with Mesorhizobium loti strain MAFF303099, which constitutively expresses GFP.

Plant Transformation and N. benthamiana Leaf Infiltration

Hairy root transformation with Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain LBA1334 was performed as described previously (Wang et al., 2013b). The hygromycin gene in vector pCAMBIA1302 was substituted by the GUS gene, generating pCAMBIA1302GUS. The GUS marker in vectors pCAMBIA1301 and pCAMBIA1302GUS was used for selection of transgenic hairy roots. Stable transformation of L. japonicus was carried using hypocotyls and cotyledons as the explants materials. In brief, explants excised from L. japonicus MG20 seedlings were infected with Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 harboring proper constructs. Generated calli were screened for hygromycin resistance, and the regenerated plants (T0) were grown to harvest the T1 seeds. More than 10 independent T0 transgenic lines were generated, and plants with identical phenotype were selected and propagated further. T1 seedlings produced genetic segregation, and a small piece of cotyledon from every seedling was removed for GUS staining. GUS-positive seedlings were transplanted and used for subsequent investigation on IT formation, nodulation, and gene regulation.

For infiltration of N. benthamiana leaves, fresh A. tumefaciens strain EHA105 carrying proper constructs was grown in Luria-Bertani medium containing 10 mm MES-KOH (pH 6.0) and 40 μm acetosyringone overnight until optical density at 600 nm ≥ 1.0. A. tumefaciens cells were collected and suspended in infiltration buffer (10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm MES-KOH, pH 6.0, and 200 μm acetosyringone). The cells were incubated at room temperature for 4 h before infiltration. For coexpression of proteins, equal amounts of two or three A. tumefaciens trains harboring proper constructs were mixed and used for infiltration. Leaves were observed 36 to 48 h after infiltration using a confocal laser-scanning microscope.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

The full-length cDNA of ROP6 (GenBank accession no. ADY16660.1) was amplified by PCR and inserted into the EcoRI/SalI sites of the vector pGBKT7 for expressing the bait protein GAL4-DNA binding domain (BD)::ROP6. Screening of interaction clones was carried out according to the procedures described previously (Zhu et al., 2008). To test protein-protein interactions in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cells, a BD construct plasmid and an AD construct plasmid were transformed to yeast strains Y187 and AH109, respectively. After mating of the two yeast strains, colonies grown on SD/-Trp/-Leu plates were transferred to SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside acid (X-gal; SD/-4/X-gal) and SD/-Trp/-Leu/X-gal (SD/-2/X-gal) plates for confirmation of protein-protein interactions. The strength of interaction was evaluated in three colonies of each interaction group by measuring β-galactosidase activity and presented as the average values of three replicates.

Plasmid Construction

To produce fusion proteins with the GAL4-DNA BD, cDNAs encoding ROP6, CLC1, CLC2, RAC1, RAC2, RAB8A, RAB8E, CHC1-7, CHC1-8, CHC1-9, and NFR5-PK were amplified by PCR. The amplified fragments were cloned into the proper sites of pGBKT7. To produce fusion proteins with the GAL4 AD, cDNAs encoding the CHC1 truncated forms (from CHC1-1 to CHC1-9), ROP6, CLC1, CLC2, RAC1, RAC2, RAB8A, RAB8E, and NFR5-PK were amplified and cloned into the proper sites of pGADT7. For coimmunoprecipitation analysis, the ROP6 cDNA without the stop codon was amplified and cloned into the SalI/SmaI site of pVYNE for expressing ROP6-(myc)-VN. The truncated CHC1-8 (1,428–1,700 amino acids) and CHC2-8 (1,429—1,702 amino acids) fragments were amplified and cloned into the SalI/SmaI site of pSCYCE-R for expressing SCCR-(HA)-CHC1-8 and SCCR-(HA)-CHC2-8. These constructs were introduced to A. tumefaciens EHA105 for infiltration. For in vitro interaction and competition assays, the CHC1-8 cDNA fragment was introduced into the EcoRI/SalI site of pMAL-c2X for expression of MBP-CHC1-8. The ROP6 and CLC1 cDNAs were amplified and inserted into EcoRI/XhoI site of pET28a for expression of His-tagged ROP6 and CLC1 recombinant proteins. For gene knockdown analyses, a 157-bp 5′-UTR (RNAi-1) and a 125-bp 3′-UTR (RNAi-2) fragments of CHC1 were amplified from L. japonicus total cDNA. The forward primers contained PstI-SmaI sites, and the reverse primers had SalI-BamHI sites. Amplified products were digested and ligated into the SmaI/BamHI site and then, the PstI/XbaI site of pCAMBIA1301-35S-int-T7. The resulting constructs containing a sense and an antisense CHC1 mRNA interrupted by an intron were driven by the CaMV 35S promoter. For expression of the dominant negative form of CHC1, the cDNA encoding CHC1-Hub was placed behind the enhanced CaMV 35S promoter. The whole expression unit was then cloned to the HindIII site of pCAMBIA1301, which contained both GUS and hygromycin selection markers for A. rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation and A. tumefaciens-mediated stable transformation. For subcellular localization, the full-length CHC1 coding sequence was obtained by primers that corresponded to the 5′- and 3′-UTRs, which were unique between CHC1 and CHC2. Using the PCR products as the template, the full-length CHC1 was reamplified and cloned to the NcoI/SpeI site of pCAMBIA1302GUS. For colocalization study, the ROP6 cDNA was cloned into the NcoI/SpeI site of pC1302GUS-DsRED, and the CHC1-8 fragment was cloned into the NcoI/SpeI site of pC1302. For promoter-GUS reporter analysis, a 2-kb LjCHC1 promoter fragment was amplified from MG20 genomic DNA and placed to pMD18-T (Takara). The fragment between the SalI and SmaI sites was then inserted upstream of the GUS gene in the binary vector pCAMBIA1391Z. All constructs together with primers, restriction enzyme cleavage sites, and short descriptions are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

In Vitro Protein-Protein Interactions

To assay the interactions of CHC1 with ROP6 and CLC1 in vitro, MBP-tagged CHC1-8 was absorbed to amylose resins and then incubated with 20 μg of purified ROP6 or CLC1 protein in 1 mL of interaction buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm NaCl, 50 mm KCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm MgCl2, and 5% [v/v] glycerol, pH 7.4) on ice for 1 h with gentle shaking. The suspension (100 μL) was mixed with SDS loading buffer and used as the input sample. After discarding the supernatant, amylose resins were washed 10 times each with 1 mL of interaction buffer. Retained proteins were eluted in 1× SDS loading buffer and separated on an SDS-PAGE gel. Subsequent immunoblotting of pull-downed proteins was carried out by HRP-conjugated anti-MBP and antipoly-His antibodies. These experiments were performed at least three times with identical or similar results. His-tagged ROP6 and CLC1 were purified using nickel-agarose beads (Qiagen).

Coimmunoprecipitation Analysis

Myc-tagged ROP6 and HA-tagged CHC1-8 or CHC2-8 were expressed from bimolecular fluorescence complementation vectors pVYNE and pSCYCE-R, the former containing an myc tag and the latter having an HA tag (Waadt et al., 2008). ROP6 protein was coexpressed with CHC1-8 or CHC2-8 in N. benthamiana leaves through coinfiltration of two A. tumefaciens strains EHA105 harboring proper constructs. Three days after infiltration, N. benthamiana leaves were powdered in liquid nitrogen, and proteins were extracted by a 1:1 g mL−1 volume ratio of leaf to homogenization buffer. The homogenization buffer contained 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 10% (w/v) Suc, and 1.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) added before use. Samples were incubated on ice for 20 min and centrifuged at 13,000g at 4°C two times for 20 min each. The supernatant (600 μL) was first subjected to preclearing by incubation for 30 min at 4°C with gentle rotation with 30 μL of protein A/G magnetic beads (L00277; GenScript), which were prewashed three times with washing buffer containing 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100. After magnetic separation, 30 μL of eluate was mixed with SDS loading buffer and used as the input sample control. For immunoprecipitation, antimyc antibody (1:100) was added to the eluate and incubated for 2 h at 4°C with gentle rotation. After that, 40 μL of washed protein A/G magnetic beads were added to the eluate and incubated for 2 h at 4°C with gentle rotation followed by magnetic separation. The unbound extract was discarded, and the beads were washed three times with washing buffer. The beads were resuspended in 100 μL of 1× SDS loading buffer and boiled for 10 min at 100°C to dissociate the immunocomplexes from the beads followed by magnetic separation of the beads. The resulting eluate was used for protein separation by SDS-PAGE and western-blot analysis using HRP-conjugated antimyc and anti-HA antibodies (Promoter Biotechnology Ltd.).

In Vitro Protein Competition Analysis

MBP-CHC1-8 bound to amylose resins was incubated with 20 μg of purified His-ROP6 protein in 1 mL of interaction buffer with gentle shaking for 1 h. After washing three times, six aliquots of amylose resins containing the MBP-CHC1-8/ROP6 complex were incubated with different concentrations (0, 20, 40, 80, 160, and 320 µg) of CLC1 protein in l mL of interaction buffer for 1 h. After washing seven times, retained proteins on amylose resins were eluted in SDS loading buffer and separated on an SDS-PAGE gel. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, and a similar gel with identical input was used for western-blot analysis using an HRP-conjugated antipoly-His antibody. The in vitro protein competition analysis was performed three times with identical results.

In Situ Immunolocalization

Roots of L. japonicus were fixed in 1% (w/v) freshly depolymerized paraformaldehyde in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, for 30 min at 4°C. After washing three times for 5 min each, roots were blocked in 1× PBS containing 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 2 h and then incubated with a 50-fold diluted anti-CHC polyclonal antibody overnight at 4°C in 1× PBS containing 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100. The anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody labeled with cyanine dye (Cy3) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promoter Biotechnology Ltd.). A control root sample was performed in the absence of the primary antibody. The anti-CHC polyclonal antibody, generated against a conserved peptide (FNELISLMESGLGLERAHMG; Wang et al., 2013a) that is present in AtCHC, LjCHC1, and LjCHC2, was provided by Jianwei Pan.

Analysis of Gene Expression

Total RNAs were isolated from L. japonicus plants using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Primescript RT Reagent Kit (Takara) was used to eliminate genomic contamination of total RNAs and synthesize first strand cDNAs. qRT-PCR was performed using the SYBR Select Master Mix (ABI) reagent. All PCR reactions were performed using an ABI ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System under the standard cycling mode: 2 min at 50°C for uracil-DNA glycosylase activation and 2 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. All of the expression levels were analyzed and normalized using Adenyl pyrophosphatase (ATPase) gene (AW719841), which is constitutively expressed in L. japonicus. For the expression assay of early nodulation genes in transgenic plants, seeds were germinated on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog (without Suc) plates for 5 d. Then, seedlings were transplanted to soil medium containing perlite and vermiculite at a 1:1 volume for a 4-d growth followed by inoculation with M. loti for 2.5 d. Roots were harvested for total RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis.

GUS Staining

Roots were washed with water and incubated in GUS staining solution [100 mm NaPO4 buffer, pH 7.0, 0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100, 0.1% [w/v] N-laurylsarcosine, 10 mm EDTA, 1 mm K3Fe(CN)6, 1 mm K4Fe(CN)6, and 0.5 mg mL−1 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-glucuronic acid] for 2 to 4 h at 37°C. For GUS staining of leaf, flower, and pod samples, the tissues were degassed under vacuum for 5 min and then incubated in the GUS solution for 6 h followed by washing with 75% (v/v) ethanol.

Treatment with Endocytosis Inhibitors

Swollen seeds were spread on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog (without Suc) plates. Plates were placed upside down for 30 to 40 h at 22°C in the dark for hypocotyl elongation (approximately 1 cm). Seeds were then transferred to one-half-strength B&D medium (1.2% [w/v] agar, pH 6.8) for 3 d of growth for root elongation (approximately 3–4 cm) and cotyledon expansion in closed plastic containers vertically placed in a greenhouse. Seedlings of four to six plants for each sample were immersed in 4 mL of liquid one-half-strength B&D medium containing various concentrations (10, 20, and 30 μm) of inhibitors (A23 or A51 dissolved in DMSO as stock solutions at concentrations of 10, 20, and 30 mm) for 6 h in the dark in six-well tissue culture dishes. An equal volume of DMSO was used as a solvent control. After that, the diluted (1:100,000) crude extracts of NF were added to the medium to induce gene expression for another 12 h at 22°C in the dark. Plants immersed in one-half-strength B&D medium for 18 h without any treatment served as a negative control (NF−). Crude extracts of NFs (1 mL) were prepared from 1 L of liquid culture of M. loti R7A (OD = 1.0) carrying plasmid pMP2112 as described previously (Cárdenas et al., 1995; Miwa et al., 2006). Treated plants were harvested for total RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis. As a control for A23 and A51 without NF treatment, seedlings treated with A23, A51, or DMSO for 6 h and seedlings without any treatments were harvested and used for qRT-PCR analysis.

Microscopic Analysis

Microscopic analysis was performed using an Olympus FV1000 confocal laser-scanning fluorescence microscope. For the subcellular localization and colocalization analyses, GFP fluorescence was excited at 488 nm, and the emission was detected at 505 to 535 nm. DsRED and Cy3 fluorescence was excited at 559 nm, and emission wavelengths were detected at 560 to 615 nm for DsRED and 560 to 650 nm for Cy3. Z projections of root hairs were reconstructed using more than 20 images taken at increments of 2 μm.

Identification of L. japonicus Mutants

Genomic DNAs were isolated from individual mutant plants and used for PCR amplification of 5 min at 95°C and 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 45 s at 72°C followed by 6 min at 72°C. Primer designs were performed as described previously (Fukai et al., 2012; Urbański et al., 2012).

Phylogenetic Analysis

Conserved motifs of CHC1 were predicted by the domain annotation tool of SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/). Full-length CHC protein sequences were aligned using Clustal X, and the alignment was used to generate the phylogenetic tree using the minimum evolution method of MEGA4.0. Sequence information used for phylogenetic analysis is listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Sequence data from this article can be found under the following GenBank accession numbers: KJ184306 for CHC1, KJ184309 for CHC2, KJ184307 for CLC1, and KJ184308 for CLC2. Other sequences cited in this article have the following accession numbers: UniProtKB O04369.1 for RAC1, UniProtKB Q40220.1 for RAC2, GenBank CAA98172.1 for RAB8A, CAA98176.1 for RAB8E, and ADY16660.1 for ROP6.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Amino acid sequence alignment of ROP6 homologs from L. japonicus.

Supplemental Figure S2. Protein-protein interactions in yeast cells and in in vitro pull-down assays.

Supplemental Figure S3. Western-blot analysis of proteins expressed in yeast cells, N. benthamiana, and L. japonicus.

Supplemental Figure S4. Tissue-specific expression of CHC1 by promoter-GUS analysis.

Supplemental Figure S5. Impaired seed development in transgenic plants expressing CHC1-Hub

Supplemental Figure S6. Root phenotypes of transgenic plants of L. japonicus expressing CHC1-Hub.

Supplemental Figure S7. Effects of CHC1-Hub expression on rhizobial infection in L. japonicus.

Supplemental Figure S8. Control samples for A23 and A51 without NF treatment.

Supplemental Figure S9. Defects in reproduction in chc1+/− heterozygous plants.

Supplemental Table S1. Database accession numbers of plant CHC sequences.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers and constructs used in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Allen Downie (John Innes Centre) for providing M. loti strain R7A carrying pMP2112, Jianwei Pan (Zhejiang Normal University) for providing anti-CHC polyclonal antibody, and the Japanese National BioResource Project and the Centre for Carbohydrate Recognition and Signaling for providing the Lotus Retrotransposon1 chc1-1 (P0665) and chc1-2 (30013963) mutant seeds.

Glossary

- AD

activation domain

- BD

binding domain

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- dpi

days postinoculation

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- IP

infection pocket

- IT

infection thread

- NF

nodulation factor

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- qRT

quantitative reverse transcription

- UTR

untranslated region

- X-gal

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside acid

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program grant no. 2010CB126502), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31170224, 30900096, and 31370278), the National Doctoral Fund of the Ministry of Education (grant no. 20130146130003), and the State Key Laboratory of Agricultural Microbiology (grant no. AMLKF200804).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Adam T, Bouhidel K, Der C, Robert F, Najid A, Simon-Plas F, Leborgne-Castel N (2012) Constitutive expression of clathrin hub hinders elicitor-induced clathrin-mediated endocytosis and defense gene expression in plant cells. FEBS Lett 586: 3293–3298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar M, Avni A (2009) EHD2 inhibits ligand-induced endocytosis and signaling of the leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein LeEix2. Plant J 59: 600–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg S, Brandstrup B, Jensen TJ, Poulsen C (1997) Identification of new protein species among 33 different small GTP-binding proteins encoded by cDNAs from Lotus japonicus, and expression of corresponding mRNAs in developing root nodules. Plant J 11: 237–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broghammer A, Krusell L, Blaise M, Sauer J, Sullivan JT, Maolanon N, Vinther M, Lorentzen A, Madsen EB, Jensen KJ, et al. (2012) Legume receptors perceive the rhizobial lipochitin oligosaccharide signal molecules by direct binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 13859–13864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas L, Domínguez J, Quinto C, López-Lara IM, Lugtenberg BJ, Spaink HP, Rademaker GJ, Haverkamp J, Thomas-Oates JE (1995) Isolation, chemical structures and biological activity of the lipo-chitin oligosaccharide nodulation signals from Rhizobium etli. Plant Mol Biol 29: 453–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Irani NG, Friml J (2011) Clathrin-mediated endocytosis: the gateway into plant cells. Curr Opin Plant Biol 14: 674–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Naramoto S, Robert S, Tejos R, Löfke C, Lin D, Yang Z, Friml J (2012) ABP1 and ROP6 GTPase signaling regulate clathrin-mediated endocytosis in Arabidopsis roots. Curr Biol 22: 1326–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla D, Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Kemmerling B, Nürnberger T, Jones JD, Felix G, Boller T (2007) A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature 448: 497–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbrosses GJ, Stougaard J (2011) Root nodulation: a paradigm for how plant-microbe symbiosis influences host developmental pathways. Cell Host Microbe 10: 348–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonukshe P, Aniento F, Hwang I, Robinson DG, Mravec J, Stierhof YD, Friml J (2007) Clathrin-mediated constitutive endocytosis of PIN auxin efflux carriers in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 17: 520–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rubbo S, Irani NG, Kim SY, Xu ZY, Gadeyne A, Dejonghe W, Vanhoutte I, Persiau G, Eeckhout D, Simon S, et al. (2013) The clathrin adaptor complex AP-2 mediates endocytosis of BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE1 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 2986–2997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukai E, Soyano T, Umehara Y, Nakayama S, Hirakawa H, Tabata S, Sato S, Hayashi M (2012) Establishment of a Lotus japonicus gene tagging population using the exon-targeting endogenous retrotransposon LORE1. Plant J 69: 720–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadeyne A, Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Vanneste S, Di Rubbo S, Zauber H, Vanneste K, Van Leene J, De Winne N, Eeckhout D, Persiau G, et al. (2014) The TPLATE adaptor complex drives clathrin-mediated endocytosis in plants. Cell 156: 691–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glebov OO, Bright NA, Nichols BJ (2006) Flotillin-1 defines a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol 8: 46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handberg K, Stougaard J (1992) Lotus japonicus, an autogamous, diploid legume species for classical and molecular genetics. Plant J 2: 487–496 [Google Scholar]

- Haney CH, Long SR (2010) Plant flotillins are required for infection by nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 478–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang KM, Gullberg L, Nelson KK, Stefan CJ, Blumer K, Lemmon SK (1997) Novel functions of clathrin light chains: clathrin heavy chain trimerization is defective in light chain-deficient yeast. J Cell Sci 110: 899–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irani NG, Russinova E (2009) Receptor endocytosis and signaling in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 653–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi M, Pedrosa-Harand A, Yano K, Hayashi M, Murooka Y, Saito K, Nagata T, Namai K, Nishida H, Shibata D, et al. (2005) Lotus burttii takes a position of the third corner in the lotus molecular genetics triangle. DNA Res 12: 69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke D, Fang Q, Chen C, Zhu H, Chen T, Chang X, Yuan S, Kang H, Ma L, Hong Z, et al. (2012) The small GTPase ROP6 interacts with NFR5 and is involved in nodule formation in Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol 159: 131–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Xu ZY, Song K, Kim DH, Kang H, Reichardt I, Sohn EJ, Friml J, Juergens G, Hwang I (2013) Adaptor protein complex 2-mediated endocytosis is crucial for male reproductive organ development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 2970–2985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Caño-Delgado A, Seto H, Hiranuma S, Fujioka S, Yoshida S, Chory J (2005) Binding of brassinosteroids to the extracellular domain of plant receptor kinase BRI1. Nature 433: 167–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitakura S, Vanneste S, Robert S, Löfke C, Teichmann T, Tanaka H, Friml J (2011) Clathrin mediates endocytosis and polar distribution of PIN auxin transporters in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 1920–1931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai H, Kouchi H (2003) Gene silencing by expression of hairpin RNA in Lotus japonicus roots and root nodules. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 16: 663–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Shen JJ, Zheng ZL, Lin Y, Yang Z (2001) The Rop GTPase switch controls multiple developmental processes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 126: 670–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens E, Franken C, Smit P, Willemse J, Bisseling T, Geurts R (2003) LysM domain receptor kinases regulating rhizobial Nod factor-induced infection. Science 302: 630–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens E, Ramos J, Franken C, Raz V, Compaan B, Franssen H, Bisseling T, Geurts R (2004) RNA interference in Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed roots of Arabidopsis and Medicago truncatula. J Exp Bot 55: 983–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SH, Wong ML, Craik CS, Brodsky FM (1995) Regulation of clathrin assembly and trimerization defined using recombinant triskelion hubs. Cell 83: 257–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EB, Antolín-Llovera M, Grossmann C, Ye J, Vieweg S, Broghammer A, Krusell L, Radutoiu S, Jensen ON, Stougaard J, et al. (2011) Autophosphorylation is essential for the in vivo function of the Lotus japonicus Nod factor receptor 1 and receptor-mediated signalling in cooperation with Nod factor receptor 5. Plant J 65: 404–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EB, Madsen LH, Radutoiu S, Olbryt M, Rakwalska M, Szczyglowski K, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, et al. (2003) A receptor kinase gene of the LysM type is involved in legume perception of rhizobial signals. Nature 425: 637–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon HT, Boucrot E (2011) Molecular mechanism and physiological functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12: 517–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa H, Sun J, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA (2006) Analysis of Nod-factor-induced calcium signaling in root hairs of symbiotically defective mutants of Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19: 914–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moling S, Pietraszewska-Bogiel A, Postma M, Fedorova E, Hink MA, Limpens E, Gadella TW, Bisseling T (2014) Nod factor receptors form heteromeric complexes and are essential for intracellular infection in Medicago nodules. Plant Cell 26: 4188–4199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagawa S, Xu T, Lin D, Dhonukshe P, Zhang X, Friml J, Scheres B, Fu Y, Yang Z (2012) ROP GTPase-dependent actin microfilaments promote PIN1 polarization by localized inhibition of clathrin-dependent endocytosis. PLoS Biol 10: e1001299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagawa S, Xu T, Yang Z (2010) RHO GTPase in plants: conservation and invention of regulators and effectors. Small GTPases 1: 78–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama K, Shinohara H, Ogawa-Ohnishi M, Matsubayashi Y (2009) A glycopeptide regulating stem cell fate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Chem Biol 5: 578–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GE. (2013) Speak, friend, and enter: signalling systems that promote beneficial symbiotic associations in plants. Nat Rev Microbiol 11: 252–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd GE, Murray JD, Poole PS, Downie JA (2011) The rules of engagement in the legume-rhizobial symbiosis. Annu Rev Genet 45: 119–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Gómez J, Moore I (2007) Plant endocytosis: it is clathrin after all. Curr Biol 17: R217–R219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip-Hollingsworth S, Dazzo FB, Hollingsworth RI (1997) Structural requirements of Rhizobium chitolipooligosaccharides for uptake and bioactivity in legume roots as revealed by synthetic analogs and fluorescent probes. J Lipid Res 38: 1229–1241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Felle HH, Umehara Y, Grønlund M, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Sandal N, et al. (2003) Plant recognition of symbiotic bacteria requires two LysM receptor-like kinases. Nature 425: 585–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Jurkiewicz A, Fukai E, Quistgaard EM, Albrektsen AS, James EK, Thirup S, Stougaard J (2007) LysM domains mediate lipochitin-oligosaccharide recognition and Nfr genes extend the symbiotic host range. EMBO J 26: 3923–3935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert S, Kleine-Vehn J, Barbez E, Sauer M, Paciorek T, Baster P, Vanneste S, Zhang J, Simon S, Čovanová M, et al. (2010) ABP1 mediates auxin inhibition of clathrin-dependent endocytosis in Arabidopsis. Cell 143: 111–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JG, Lyttleton P (1982) Coated and smooth vesicles in the biogenesis of cell walls, plasma membranes, infection threads and peribacteroid membranes in root hairs and nodules of white clover. J Cell Sci 58: 63–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron M, Avni A (2004) The receptor for the fungal elicitor ethylene-inducing xylanase is a member of a resistance-like gene family in tomato. Plant Cell 16: 1604–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauser L, Roussis A, Stiller J, Stougaard J (1999) A plant regulator controlling development of symbiotic root nodules. Nature 402: 191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharfman M, Bar M, Ehrlich M, Schuster S, Melech-Bonfil S, Ezer R, Sessa G, Avni A (2011) Endosomal signaling of the tomato leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein LeEix2. Plant J 68: 413–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit P, Limpens E, Geurts R, Fedorova E, Dolgikh E, Gough C, Bisseling T (2007) Medicago LYK3, an entry receptor in rhizobial nodulation factor signaling. Plant Physiol 145: 183–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, Pearse BM (1999) Clathrin: anatomy of a coat protein. Trends Cell Biol 9: 335–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyano T, Kouchi H, Hirota A, Hayashi M (2013) Nodule inception directly targets NF-Y subunit genes to regulate essential processes of root nodule development in Lotus japonicus. PLoS Genet 9: e1003352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke S, Kistner C, Yoshida S, Mulder L, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J, Szczyglowski K, et al. (2002) A plant receptor-like kinase required for both bacterial and fungal symbiosis. Nature 417: 959–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki T, Ito M, Kawaguchi M (2013) Genetic basis of cytokinin and auxin functions during root nodule development. Front Plant Sci 4: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki T, Yano K, Ito M, Umehara Y, Suganuma N, Kawaguchi M (2012) Positive and negative regulation of cortical cell division during root nodule development in Lotus japonicus is accompanied by auxin response. Development 139: 3997–4006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers AC, Auriac MC, de Billy F, Truchet G (1998) Nod factor internalization and microtubular cytoskeleton changes occur concomitantly during nodule differentiation in alfalfa. Development 125: 339–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbański DF, Małolepszy A, Stougaard J, Andersen SU (2012) Genome-wide LORE1 retrotransposon mutagenesis and high-throughput insertion detection in Lotus japonicus. Plant J 69: 731–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waadt R, Schmidt LK, Lohse M, Hashimoto K, Bock R, Kudla J (2008) Multicolor bimolecular fluorescence complementation reveals simultaneous formation of alternative CBL/CIPK complexes in planta. Plant J 56: 505–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Yan X, Chen Q, Jiang N, Fu W, Ma B, Liu J, Li C, Bednarek SY, Pan J (2013a) Clathrin light chains regulate clathrin-mediated trafficking, auxin signaling, and development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 499–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Zhu H, Jin L, Chen T, Wang L, Kang H, Hong Z, Zhang Z (2013b) Splice variants of the SIP1 transcripts play a role in nodule organogenesis in Lotus japonicus. Plant Mol Biol 82: 97–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F, Murray JD, Kim J, Heckmann AB, Edwards A, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA (2012) Legume pectate lyase required for root infection by rhizobia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 633–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybe JA, Brodsky FM, Hofmann K, Lin K, Liu SH, Chen L, Earnest TN, Fletterick RJ, Hwang PK (1999) Clathrin self-assembly is mediated by a tandemly repeated superhelix. Nature 399: 371–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yan A, Feijó JA, Furutani M, Takenawa T, Hwang I, Fu Y, Yang Z (2010) Phosphoinositides regulate clathrin-dependent endocytosis at the tip of pollen tubes in Arabidopsis and tobacco. Plant Cell 22: 4031–4044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Chen T, Zhu M, Fang Q, Kang H, Hong Z, Zhang Z (2008) A novel ARID DNA-binding protein interacts with SymRK and is expressed during early nodule development in Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol 148: 337–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.