Abstract

Due to the rarity of duodenal adenocarcinoma (DAC), the clinicopathologic features and prognostication data for DAC are limited. There are no published studies directly comparing the prognosis of DAC to ampullary adenocarcinoma (AA) and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) after resection. In this study, we examined the clinicopathologic features of 68 patients with DAC, 92 patients with AA and 126 patients with PDA, who underwent resection. Patient clinicopathologic and survival information were extracted from medical records. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) with two-sided significance level of 0.05. Patients with DAC had higher American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage than AA patients (P=0.001). Lymph node metastasis (P=0.013) and AJCC stage (P=0.02) correlated with overall survival in DAC patients. Patients with DAC or AA had lower frequencies of lymph node metastasis and positive margin and better survival than those with PDA (P<0.05). However, no differences in nodal metastasis, margin status or survival were observed between DAC patients and those with AA. Our study showed that lymph node metastasis and AJCC stage are important prognostic factors for overall survival in DAC patients. Patients with DAC had less frequent nodal metastasis and better prognosis than those with PDA. There was no significant difference in prognosis between DAC and AA.

Keywords: Duodenal adenocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer, ampullary adenocarcinoma, survival, prognosis

Introduction

Small bowel comprises over 75% of the length of digestive tract and more than 90% of its absorptive surface, yet tumors arising from it are extremely rare, accounting for less than 2% of all malignant tumors of digestive tract (1). Based on the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result Registry (SEER) data, the average age-adjusted incidences for adenocarcinoma of small intestine ranged from 4.5 to 12.2 per 1,000,000 population during 1973-2005, which were less than 2% of colorectal adenocarcinomas (1, 2). The rarity of small bowel adenocarcinoma has been attributed to microenvironmental factors such as increased transient time, low bacterial load, liquid chyme with less mechanical trauma, alkaline environment, well developed local IgA-mediated immune system, less endogenous reactive oxygen species and high cellular turnover (3). Recently, Goodman et al. reviewed 56,223 patients who diagnosed with all different types of small bowel tumors and found that the risk of small adenocarcinoma was higher in blacks and lower in Asian-Pacific Islanders compared to white (4). Although most of the small bowel adenocarcinomas are sporadic, a subset of small bowel adenocarcinoma is associated with hereditary or inflammatory conditions such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC), Crohn’s disease, and celiac disease (5-7).

Among the patients with adenocarcinoma of small bowel, duodenal adenocarcinoma (DAC) is more common (55%) than the adenocarcinoma of the jejunum (18%) and ileum (13%) (8). For patients who underwent surgical resection for DAC, the reported 5-year survival rates range from 18% to 71% (9-22). Lymph node metastasis, tumor size, location, the depth of tumor invasion, and metastases to regional and distant organs, have been reported to be important prognostication factors (9-13, 15, 16, 18-22). However, the findings of previous studies on prognostic factors of DAC are inconsistent. In addition, the direct comparison of the prognosis of DAC with other periampullary adenocarcinoma after surgical resection, such as the ampullary adenocarcinoma (AA) and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) has not been reported. Therefore we retrospectively reviewed the clininical and pathologic features of 68 patients with DAC who underwent curative surgical resection in our institution. The findings were correlated with the overall survival. In addition, we compared the overall survival of DAC to 92 patients with AA and 126 patients with PDA who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy at our institution during a same period of time. Our data showed that lymph node metastasis and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage are important prognostic factor for patients with DAC and that patients with DAC had similar survival to those with AA, but better prognosis than PDA.

Material and Method

Study population

The study population consisted of 68 consecutive patients with DAC who underwent surgical resection with curative intent at our institution from 1990-2011, including 22 DAC patients who received neoadjuvant therapy before surgery (35 males and 33 females with age ranging from 35 to 88 years and median age at diagnosis of 59 years), 92 patients with AA (55 males and 37 females with age ranging from 28 to 87 year and median age at diagnosis of 66 years) and 126 with PDA (76 males and 50 females with age ranging from 25 to 85 years and median age at diagnosis of 63.4 years), who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy at our institution during the same time period. For the diagnosis of AA, we used the criteria proposed by Adsay et al. and defined AA as a tumor epicentered in the lumen or walls of the distal ends of the common bile duct and/or pancreatic duct; at the “papilla of Vater”, or at the duodenal surface of the papilla (23). Patients with AA or PDA, who received any form of neoadjuvant therapy, were excluded from this retrospective study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Pathologic examination

The archival hematoxylin-and-eosin (H & E) stained slides from all cases were reviewed. All DAC cases were reviewed for the type of surgery, tumor location, tumor size, presence or absence of adenoma, differentiation, depth of invasion (pT stage), lymph node status (pN) and margin status. The pathologic stage grouping was determined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging Manual, 7th edition (24). Among all DAC patients, 28 patients had been evaluated for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal carcinoma (HNPCC) via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for microsatellite instability (MSI) and/or immunohistochemical analyses for MSI markers (18 tested by both molecular and immunohistochemistry and 10 by immunohistochemistry alone).

Statistical analysis

Patients’ clinical and follow up information was extracted from patients’ medical records and/or by review of the U.S. Social Security Index. Chi-square analysis or Fisher's exact tests were used to compare categorical data. Overall survival was calculated as the time from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or to last follow up if death did not occur. Overall survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences in association with clinicopathologic parameters. The prognostic significance of clinical and pathologic characteristics was determined by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis using a backward stepwise procedure. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 19 for Windows (Somers, NY). A two-sided significance level of 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Clinicopathologic features of duodenal adenocarcinoma compared to ampullary and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

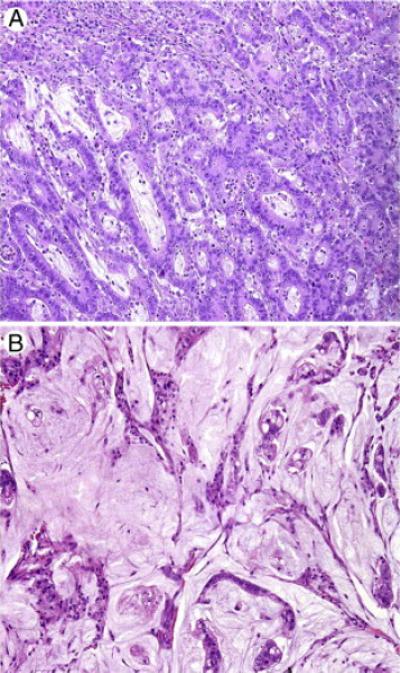

The patient demographic and pathologic features and stage information of the DAC, AA, and PDA are listed in Table 1. Among the 68 patients with DAC, 53 underwent pancreaticoduodenectomies, 11 underwent duodenojejunectomies, three underwent segmental duodenal resections and one underwent transduodenal resection. The tumor was located in the proximal (the first portion), periampullary (second portion) and distal (3rd and 4th portions) of the duodenum in 4 (6%), 40 (59%) and 24 (35%) respectively. Tumor size ranged from 0.3 to 7.4 cm (median: 3.5 cm); Tubulovillous adenoma was present in 24 patients (35%). Well, moderate, and poor differentiation of tumor was noted in 0, 50, and 18 patients, respectively, 12 (18%) of which had mucinous differentiation (Figure 1A & 1B). T1, T2, T3, and T4 tumor was present in 4 (5.9%), 13 (19.1%), 31 (45.6%), and 20 (29.4%) patients respectively. Lymph node metastasis was present in 33 (48.5%) patients. At the time of surgery, AJCC stage I, II, III and IV disease was present in 6 (8.8%), 25 (36.8%), 32 (47.1%), and 5 (7.4%) patients respectively. Majority of patients (46/68, 68%) did not receive neoadjuvant therapy (46 patients), while 22 patients (32%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation before surgical resection. Patients with DAC had higher AJCC stage than those with AA (P<0.001). Vast majority (95.2%) of the patients with PDA had stage II disease. Patients with PDA had more frequent lymph node metastasis and higher rate of positive resection margin than those with either DAC or AA (P<0.05). However there is no significant differences in lymph node metastasis or frequency of positive resection margin between the patients with DAC and those with AA (P>0.05). There was also no significant difference in tumor differentiation among these three groups of patients (P>0.05).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features of DACs compared with AAs and PDAs

| Parameters | DAC (n = 68) | AA (n = 92) | PDA (n = 126) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age<comma> y (range) | 59.0 (35-88) | 66 (28-87) | 63.4 (25-85) | > .05 |

| Sex | 0.45 | |||

| Male | 35 (51.5%) | 55 (59.8%) | 76 (60.3%) | |

| Female | 33 (48.5%) | 37 (40.2%) | 50 (39.7%) | |

| Differentiation | 0.07 | |||

| Well | 0 (0%) | 7 (7.6%) | 10 (7.9%) | |

| Moderate | 50 (73.5%) | 52 (56.5%) | 82 (65.1%) | |

| Poor | 18 (26.5%) | 33 (35.9%) | 34 (27.0%) | |

| Margin | .0001a | |||

| Negative | 66 (97.1%) | 86 (93.5%) | 100 (79.4%) | |

| Positive | 2 (2.9%) | 6 (6.5%) | 26 (20.6%) | |

| pT | ||||

| .0001a | T1 | 4 (5.9%) | 15 (16.3%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| T2 | 13 (19.1%) | 35 (38.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| T3 | 31 (45.6%) | 35 (38.0%) | 122 (96.8%) | |

| T4 | 20 (29.4%) | 7 (7.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Lymph nodes | .001a | |||

| Negative | 35 (51.5%) | 41 (44.6%) | 32 (25.4%) | |

| Positive | 33 (48.5%) | 51 (55.4%) | 94 (74.6%) | |

| AJCC stage | .0001a | |||

| I | 6 (8.8%) | 30 (32.6%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| II | 25 (36.8%) | 48 (52.2%) | 120 (95.2%) | |

| III | 32 (47.1%) | 14 (15.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| IV | 5 (7.4%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3.2%) |

Figure 1.

Representative micrographs showing a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (A) and a moderately differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma (B) of duodenum. Hematoxylin & eosin (H & E) stain, original magnification: 200×.

Among the 28 patients who were screened for HNPCC, 12 (43%) had high level of microsatellite instability (MSI-H), one was microsatellite instability low, and 15 were microsatellite stable. Three patients had clinical diagnosis of HNPCC: two patients with germline mutation of MSH2 gene and one patient with MLH1 germline mutation. Patients with MSI-H DAC had a trend of better survival than those whose tumors were MSS/MSI-L, but the difference was not significant (P=0.41, data not shown).

Survival analysis of duodenal adenocarcinoma

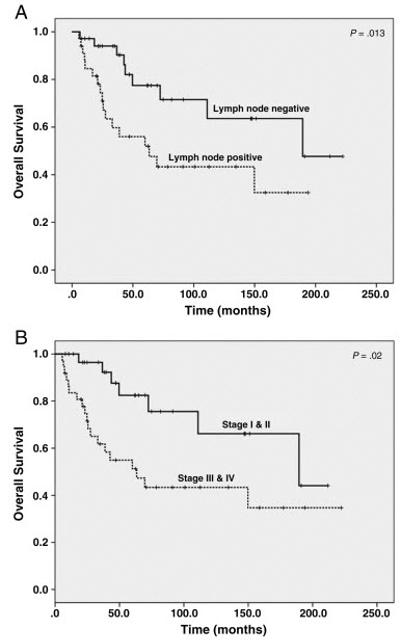

Follow-up information was available in all patients with DAC. The follow up time ranged from 6 to 222 months with the mean of 67 months. During the follow up, metastasis to liver, lung, peritoneum/mesentery, skin, ovary, and local recurrence developed in 6, 4, 3, 1, 1, and 6 patients, respectively. The median survival was 149.8 months and the mean survival was 131.0 ± 13.0 months. Overall 5-year survival was 55.9%. Lymph node metastasis and AJCC stage correlated with the overall survival (Figure 2A and 2B). However, there was no significant correlation between the survival and other clinicopathologic parameters, including gender, pathologic T stage, tumor differentiation, mucinous morphology, the presence of adenoma, size of tumor, site of duodenum involved, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and the type of surgery (Table 2). Multivariate survival analysis for DAC was not performed since the p value for the other clinicopathologic factors are not close to significant level (p>0.15).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of overall survival in patients with duodenal adenocarcinoma stratified by the lymph node metastasis (A) and AJCC stages (B). Patients with lymph node metastasis or AJCC stage III or IV disease had shorter overall survival than those who were negative for lymph metastasis or those who had AJCC stage I or II disease.

Table 2.

Univariate Cox regression analysis of overall survival in patients with DAC

| Characteristics | n | Overall survival | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female (ref) | 33 | 1 | |

| Male | 35 | 0.96 (0.44-2.08) | 0.91 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | |||

| No | 46 | 1 | |

| Yes | 22 | 1.74 (0.78-3.87) | 0.18 |

| Surgery type | |||

| Pancreaticoduodenetomy (ref) | 53 | 1 | |

| Other | 15 | 1.13 (0.42-3.04) | 0.81 |

| Tumor location | |||

| Proximal (ref) | 4 | 1 | |

| Periampullary | 40 | 2.37 (0.48-11.62) | 0.29 |

| Distal | 24 | 1.09 (0.45-2.63) | 0.85 |

| Mucinous histology | |||

| Nonmucinous (ref) | 56 | 1 | |

| Mucinous | 12 | 1.36 (0.74-2.49) | 0.32 |

| Presence of adenoma | |||

| No (ref) | 44 | 1 | |

| Yes | 24 | 1.21 (0.80-1.84) | 0.36 |

| Tumor size | 68 | 0.96 (0.76-1.22) | 0.76 |

| Margin | |||

| Negative (ref) | 66 | 1 | |

| Positive | 2 | 0.83 (0.31-2.27) | 0.72 |

| Tumor differentiation | |||

| Moderate (ref) | 50 | 1 | |

| Poor | 18 | 1.41 (0.61-3.25) | 0.42 |

| Pathologic tumor stage | |||

| pT1 and pT2 (ref) | 17 | 1 | |

| pT3 and pT4 | 51 | 1.59 (0.63-4.02) | 0.33 |

| Lymph nodes | |||

| Negative (ref) | 35 | 1 | |

| Positive | 33 | 2.55 (1.13-5.76) | .02a |

| AJCC stage | |||

| Stages I and II (ref) | 31 | 1 | |

| Stages III and IV | 37 | 2.87 (1.20-6.83) | .02a |

Comparison of survivals among patients with duodenal, ampullary and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

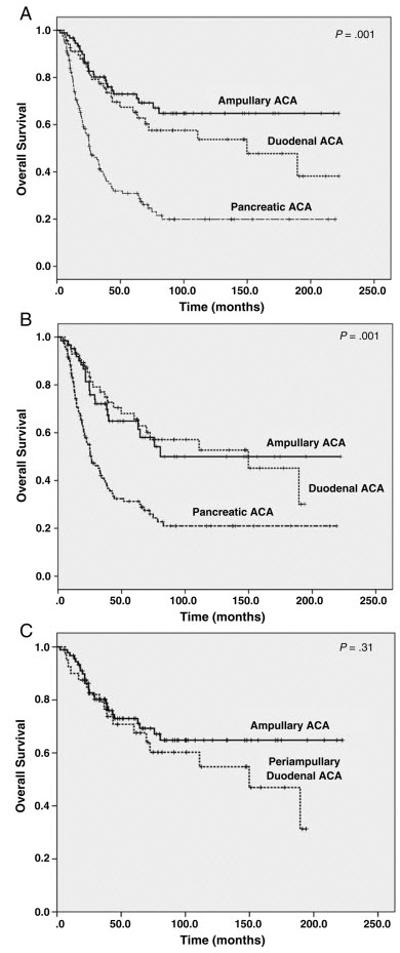

We compared the survival of patients with DAC to 92 patients with AA and 126 patients with PDA who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy during the same time period at our institution and received no neoadjuvant therapy. There was no significant difference in survival between DAC and AA in overall study population or those with stage II and stage III disease. However, patients with PDA had a shorter survival than either patients with DAC or those with AA (Figures 3A and 3B). There was also no significant difference in survival between the patients with periampullary DAC (N=40) and those with AA (p=0.31, Figure 3C). Since patients with DAC had higher AJCC stage compared to patients with AAs in our study population, we performed multivariate analysis to compare the survival between patients with DAC and those with AA. After adjusting the AJCC stage, no significant difference in survival between patients with DAC and those with AA were observed (p=0.55, Table 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of overall survival in patients with duodenal adenocarcinoma in comparison with ampullary adenocarcinoma and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma among all patients (A) and those with stages II and III only (B). Patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma had shorter overall survival than those with either duodenal adenocarcinoma or ampullary adenocarcinoma (p=0.001). However, there is no significant difference in overall survival between the patients with duodenal adenocarcinoma and those with ampullary adenocarcinoma (p>0.05).

C. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of overall survival in patients with periampullary duodenal adenocarcinoma (N=40) compared to ampullary adenocarcinoma (p=0.31).

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis to compare the overall survival in the patients with DAC and those with AA

| Characteristics | No. of patients | Overall survival | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Primary site | |||

| AA (ref) | 92 | 1 | |

| DAC | 68 | 0.83 (0.46-1.52) | 0.55 |

| AJCC stage | .01a | ||

| Stage I (ref) | 36 | 1 | |

| Stage II | 73 | 5.57 (1.69-18.39) | .005a |

| Stage III | 46 | 7.09 (2.09-24.03) | .002a |

| Stage IV | 5 | 11.49 (2.29-57.44) | .003a |

Discussion

In this study, we examined the clinicopathologic features of 68 patients with DAC who underwent surgical resection and correlated with the results with patient survival. We found that lymph node metastasis and AJCC stage correlated with the overall survival in patients with DAC. Our data also showed that patients with DAC had no significant difference in survival from those with AA after resection. However, patients with either DAC or AA had better survival than those with PDA after resection.

Primary adenocarcinoma of the duodenum is rare. Previous studies on the clinicopathologic parameters that are predictive of prognosis reported conflicting results and most of the previous studies lacked systematic pathologic examination. In this study, all the cases were reviewed for the type of surgery, tumor location, tumor size, differentiation, mucinous histology, presence or absence of adenoma, depth of invasion (pT stage), lymph node status, AJCC stage and margin status. Our data showed that lymph node metastasis and the AJCC stage were important prognostic factors in patients with DAC after resection. Consistent with our results is the recent study of 122 patients with resected DACs from a single institution by Poultsides et al, which showed that lymph node metastasis is the only independent predictor for overall survival by multivariate analysis. However, the AJCC stage was not examined in their analysis. Similarly, other studies also showed that lymph node metastasis or AJCC stage correlated with overall survival in patients with DAC (9-13, 15, 16, 18-21). Although some of the previous studies showed that the pT stage, tumor size, degree of differentiation, tumor location, type of surgery, or positive margin are predictive of overall survival in patients with DAC (9, 12, 15, 18-20, 22), we did not observe significant correlation between any of these factors and overall survival in our study population. The median survival in our patient population was 149.8 ± 53.0 months and the 5-year survival rate was 55.9%, which was better than 29% 5-year survival reported by Barnes et al. and 31% 5-year survival reported by Rose et al.(25, 26), but similar to 48% 5-year survival reported by Poutsides et al (22). This is due to the fact that only patients who underwent surgery with the intent to cure were included in our study and Poutsides’ study. In fact, the 5-year survival rates in patients who underwent curative surgery were 54% and 60% respectively in the studies by Barnes et al. and Rose et al. and both studies reported 0% 5-year survival in those with non-resected disease (25, 26). These data suggest that curative surgical resection improves the outcome in patients with DAC.

Comparison of the prognosis among the patients with DAC, AA and PDA after curative surgical resection has not been previously reported. In this study, we showed that patients with DAC had similar prognosis to those with AA after surgical resection. However, the survival of either DAC patients or patients with AA was significantly better those with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma despite of the lower disease stage in our PDA group (3.2% stage III/IV) compared to either DAC group (54.5% stage III/IV) or AA group (15.2% stage III/IV). Our data are consistent with the previous study which showed that patients with PDA have shorter survival than those with AA after surgical resection (27). These data highlight the more aggressive biological behavior of PDA.

Small bowel adenocarcinoma has been reported to be associated with other tumors, including carcinoma of the colorectum, prostate, female genital tract, and lung (28, 29). Twenty-two of our DAC patients had at least one other tumors including 10 colorectal, 2 breast, 1 endometrial, 2 renal cell carcinoma, 3 prostate cancer, 1 intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas, 1 gastric carcinoma, 1 melanoma, and 1 gastrointestinal stromal tumor. It is interesting that 12 (43%) of the 28 patients who had been tested for MSI status were MSI-high in our DAC patient population. Among them, only three patients had confirmed diagnosis of HNPCC. Patients with MSI-H DAC had a trend of better survival than those whose tumors were MSS/MSI-L, but the difference was not significant due to the limited number of patients. In a previous study, Overman et al. reported 35% of MSI-high tumor in their study of 54 patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma (30). One possible reason for the higher rate of MSI-high may be due to the selection bias for those patients who underwent MSI testing. None of our patients with either DAC or AAs had the diagnosis of FAP. Future study is needed to further examine the mechanism and correlation of MSI status in DAC patients.

In summary, our study showed that lymph node metastasis and AJCC stage correlate with the survival in patients with DAC after surgical resection. Patients with DAC have similar prognosis to those with AA, but better prognosis than those with PDA after surgical resection. The long survival for DAC observed in this study suggests that patients with DAC should be managed by surgical resection if possible.

Acknowledgement

Supported by G. S. Hogan Gastrointestinal Cancer Research Fund, the Khalifa Bin Zayed Al Nahyan Foundation, and the Kavanagh Family Foundation at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and the National Institutes of Health grant (1R21CA149544-01A1)

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest or funding to disclose

References

- 1.Schottenfeld D, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Vigneau FD. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of neoplasia in the small intestine. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overman MJ, Hu CY, Kopetz S, Abbruzzese JL, Wolff RA, Chang GJ. A population-based comparison of adenocarcinoma of the large and small intestine: insights into a rare disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1439–1445. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2173-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan SY, Morrison H. Epidemiology of cancer of the small intestine. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3:33–42. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v3.i3.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman MT, Matsuno RK, Shvetsov YB. Racial and ethnic variation in the incidence of small-bowel cancer subtypes in the United States, 1995-2008. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2013;56:441–448. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31826b9d0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green PHJB. Celiac disease and other precursors to small-bowel malignancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:625–639. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(02)00010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulmann KEC, Propping P, Schmiegel W. Small bowel cancer risk in Lynch syndrome. Gut. 2008;57:1629–1630. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.140657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aparicio T, Zaanan A, Svrcek M, Laurent-Puig P, Carrere N, Manfredi S, Locher C, Afchain P. Small bowel adenocarcinoma: Epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howe JR, Karnell LH, Menck HR, Scott-Conner C. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: review of the National Cancer Data Base, 1985-1995. Cancer. 1999;86:2693–2706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991215)86:12<2693::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouriel K, Adams JT. Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. American journal of surgery. 1984;147:66–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes G, Jr., Romero L, Hess KR, Curley SA. Primary adenocarcinoma of the duodenum: management and survival in 67 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:73–78. doi: 10.1007/BF02303544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaklamanos IG, Bathe OF, Franceschi D, Camarda C, Levi J, Livingstone AS. Extent of resection in the management of duodenal adenocarcinoma. American journal of surgery. 2000;179:37–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryder NM, Ko CY, Hines OJ, Gloor B, Reber HA. Primary duodenal adenocarcinoma: a 40-year experience. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1070–1074. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.9.1070. discussion 1074-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarela AI, Brennan MF, Karpeh MS, Klimstra D, Conlon KC. Adenocarcinoma of the duodenum: importance of accurate lymph node staging and similarity in outcome to gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:380–386. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alwmark A, Andersson A, Lasson A. Primary carcinoma of the duodenum. Annals of surgery. 1980;191:13–18. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198001000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowell JA, Rossi RL, Munson JL, Braasch JW. Primary adenocarcinoma of third and fourth portions of duodenum. Favorable prognosis after resection. Arch Surg. 1992;127:557–560. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420050081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delcore R, Thomas JH, Forster J, Hermreck AS. Improving resectability and survival in patients with primary duodenal carcinoma. American journal of surgery. 1993;166:626–630. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80668-3. discussion 630-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotman N, Pezet D, Fagniez PL, Cherqui D, Celicout B, Lointier P. Adenocarcinoma of the duodenum: factors influencing survival. French Association for Surgical Research. The British journal of surgery. 1994;81:83–85. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakaeen FG, Murr MM, Sarr MG, Thompson GB, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, Farley DR, van Heerden JA, Wiersema LM, Schleck CD, Donohue JH. What prognostic factors are important in duodenal adenocarcinoma? Arch Surg. 2000;135:635–641. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.6.635. discussion 641-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurtuk MG, Devata S, Brown KM, Oshima K, Aranha GV, Pickleman J, Shoup M. Should all patients with duodenal adenocarcinoma be considered for aggressive surgical resection? American journal of surgery. 2007;193:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.09.013. discussion 324-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han SL, Cheng J, Zhou HZ, Zeng QQ, Lan SH. The surgical treatment and outcome for primary duodenal adenocarcinoma. Journal of gastrointestinal cancer. 2011;41:243–247. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Struck A, Howard T, Chiorean EG, Clarke JM, Riffenburgh R, Cardenes HR. Non-ampullary duodenal adenocarcinoma: factors important for relapse and survival. Journal of surgical oncology. 2009;100:144–148. doi: 10.1002/jso.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poultsides GA, Huang LC, Cameron JL, Tuli R, Lan L, Hruban RH, Pawlik TM, Herman JM, Edil BH, Ahuja N, Choti MA, Wolfgang CL, Schulick RD. Duodenal adenocarcinoma: clinicopathologic analysis and implications for treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1928–1935. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2168-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adsay V, Ohike N, Tajiri T, Kim GE, Krasinskas A, Balci S, Bagci P, Basturk O, Bandyopadhyay S, Jang KT, Kooby DA, Maithel SK, Sarmiento J, Staley CA, Gonzalez RS, Kong SY, Goodman M. Ampullary region carcinomas: definition and site specific classification with delineation of four clinicopathologically and prognostically distinct subsets in an analysis of 249 cases. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2012;36:1592–1608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826399d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edge S, Byrd D, Compton C, Fritz A, Greene F, Trotti A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes G, Jr, Hess KR, Curley SA. Primary Adenocarcinoma of the Duodenum: Management and Survival in 67 Patients. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 1994;1:73–78. doi: 10.1007/BF02303544. RL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose DM, Hochwald SN, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF. Primary duodenal adenocarcinoma: a ten-year experience with 79 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatzaras I, George N, Muscarella P, Melvin WS, Ellison EC, Bloomston M. Predictors of survival in periampullary cancers following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:991–997. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0883-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neugut AI, Jacobson JS, Suh S, Mukherjee R, Arber N. The epidemiology of cancer of the small bowel. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:243–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veyrieres M, Baillet P, Hay JM, Fingerhut A, Bouillot JL, Julien M. Factors influencing long-term survival in 100 cases of small intestine primary adenocarcinoma. American journal of surgery. 1997;173:237–239. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)89599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Overman MJ, Pozadzides J, Kopetz S, Wen S, Abbruzzese JL, Wolff RA, Wang H. Immunophenotype and molecular characterisation of adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:144–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]