Abstract

Heparan sulfate is a highly sulfated polysaccharide that exhibits important physiological and pathological functions. The glucosamine residue of heparan sulfate can carry sulfo groups at the 2-N-, 3-O- and 6-O- positions, leading to diverse polysaccharide structures. 6-O-sulfation at the glucosamine residue contributes to a wide range of biological functions. Here, we report a method to control the positioning of 6-O-sulfo groups in oligosaccharides. This was achieved by synthesizing oligosaccharide backbones from a disaccharide building block utilizing glycosyltransferases followed by modifications using heparan sulfate N-sulfotransferase and 6-O-sulfotransferases. This method offers a viable approach preparing heparan sulfate oligosaccharides with precisely located 6-O-sulfo groups.

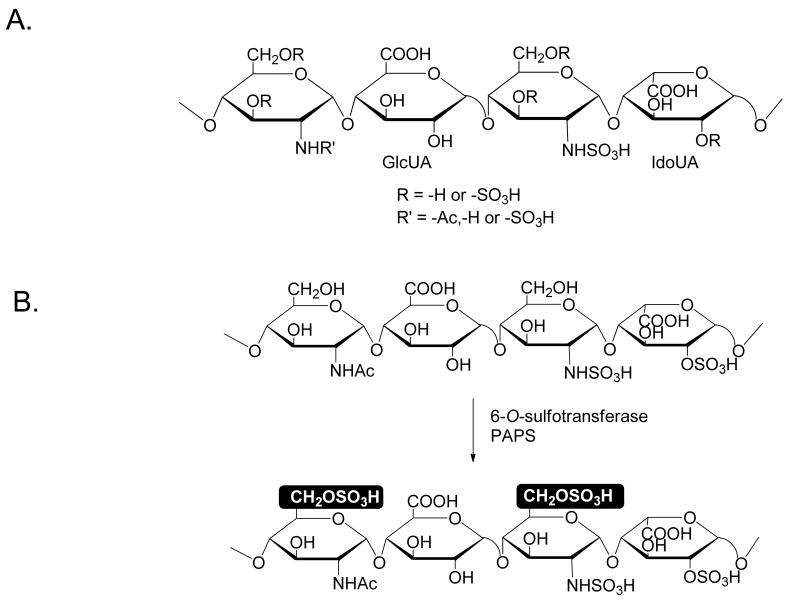

Heparan sulfate (HS) is a linear polysaccharide that is present on mammalian cell surfaces and in the extracellular matrix. HS is involved in numerous biological processes, including blood coagulation, wound healing, embryonic development and regulation of tumor growth, as well as in assisting viral and bacterial infections (1). The wide range of biological functions of HS attracts considerable interest in exploiting HS-based anticoagulant (2, 3), antiviral (4) and anticancer drugs (5). Heparin, a commonly used anticoagulant, is a highly sulfated form of HS. HS consists of repeating disaccharide units of glucosamine and glucuronic acid (GlcUA) or iduronic acid (IdoUA), both capable of carrying sulfo groups (Fig 1A). The positions of the sulfo groups and IdoUA dictate the functions of HS (6, 7).

Fig 1. Structure of HS and 6-O-sulfation of HS.

Panel A shows the chemical structure of heparan sulfate. The structures of glucuronic acid (GlcUA) and iduronic acid (IdoUA) are indicated. Panel B shows the enzymatic reaction catalyzed by 6-OST, where PAPS is a sulfo donor. The modification site is highlighted.

The biosynthesis of HS is accomplished by a complex pathway involving backbone elongation and multiple modification steps. HS polymerase is responsible for building the polysaccharide backbone, which contains repeating units of –GlcUA-GlcNAc-. The backbone is then modified by N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase (which has two separate domains that exhibit N-deacetylation and N-sulfation, respectively), C5-epimerase (which converts GlcUA to IdoUA), 2-O-sulfotransferase, 6-O-sulfotransferase (6-OST) and 3-O-sulfotransferase to produce the fully elaborated HS. Understanding this biosynthetic mechanism has advanced our ability to synthesize HS (8). Using HS sulfotransferases and C5-epimerase, we developed a method to synthesize HS polysaccharides (2, 9, 10) and oligosaccharides with defined structures (11). Previously, a method for positioning N-sulfo glucosamine and IdoUA2S residues was demonstrated (11). It is still unknown whether or not placing a 6-O-sulfo group in a given oligosaccharide is possible.

The 6-O-sulfo glucosamine unit is a common monosaccharide in HS. It has been found that the 6-O-sulfo glucosamine residue plays a critical role in numerous biological functions. For example, heparin carrying 6-O-sulfo groups exhibits anti-inflammatory effects by blocking the binding of HS to L- and P-selectins (12). The 6-O-sulfated glucosamine residue was also found to regulate the fibroblast growth factor-mediated signaling pathway by binding to the fibroblast growth factor receptor (13, 14). 6-OST-1 knockout mice were shown to exhibit numerous defects. Most of the mice died at the embryonic and perinatal stages. Those that survived were significantly smaller in size than the wild type (15). These observations underscore the essential role of HS 6-OSTs in developmental physiology. In Drosophila, the removal of 6-OST genes has no obvious phenotype, suggesting the complex roles of 6-O-sulfation in different organisms. Mutant strains of Drosophila have elevated levels of 2-O-sulfation in response to the loss of 6-OST(16).

Little is known about how 6-O-sulfation patterns are regulated. HS 6-OSTs, which are present in three isoforms including 6-OST-1, -2 and -3 (17), catalyze the transfer of a sulfo group to the C6 position of a glucosamine residue (GlcN) to form 6-O-sulfo glucosamine (Fig 1B). Furthermore, HS 6-O-sulfatases remove 6-O-sulfo groups from HS in vivo and remodel HS structures (18,19). 6-O-sulfation occurs predominantly at N-sulfo glucosamine (GlcNS) residues. However, in some cases, it can also occur at the GlcNAc residues. Unlike different 3-O-sulfotransferase isoforms, 6-OST isoforms appear to recognize the same substrates (20), suggesting that a different strategy will be needed to introduce a 6-O-sulfo group in a specific position.

In this article, we report the placement of a 6-O-sulfo group at specific oligosaccharides using an enzymatic approach. We demonstrated the feasibility of selectively introducing a 6-O-sulfo group using two distinct methods. First, by controlling the reaction time, we prepared partially 6-O-sulfated hexasaccharides although a mixture of two products was obtained. Second, we elongated the oligosaccharides already carrying 6-O-sulfo groups using glycosyltransferases. Our method provided a generic tool for synthesizing HS oligosaccharides with defined 6-O-sulfation patterns with which to elucidate the structure and activity relationship of HS. The results also aid our understanding of the substrate specificity of 6-OSTs.

Experimental Procedures

Expression and purification of HS biosynthetic enzymes

A total of five enzymes were employed for the synthesis of oligosaccharide substrates and for 6-O-sulfation, including N-acetyl d-glucosaminyl transferase from the E. coli K5 strain (KfiA), N-sulfotransferase (NST), 6-O-sulfotransferase 1 (6-OST-1), 6-O-sulfotransferase 3 (6-OST-3) and heparosan synthase-2 (PmHS2) from Pasteurella multocida. All of these enzymes were expressed in E. coli using different fusion proteins as described previously (2, 21, 22). For 6-OST-1 and 6-OST-3, maltose-binding fusion proteins were used, and the fusion proteins were purified by an amylose column (New England Biolab). For NST, a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein was prepared and purified by a glutathione Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) (21). PmHS2 was expressed as an N-terminal fusion protein with a 6 × His-tag using a PET-15b vector (Novagen) (11). The expression of KfiA was carried out in BL21 star (DE3) cells (Invitrogen) coexpressing the bacterial chaperone proteins, GroEL and GroES.

Synthesis of a fluorous-tagged disaccharide (GlcUA-AnMan-Rf) and tagged oligosaccharide substrates

A disaccharide (GlcUA-AnMannose) was prepared from nitrous acid degraded heparosan as previously described omitting the NaBH4 reduction step (22). The resultant disaccharide was dialyzed against water using a 1000 molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) membrane (Spectrum). To introduce a fluorous-tag, the disaccharide was incubated with 2 equivalents of 4-(1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluoropentyl) benzylamine hydrochloride (Fluorous Technologies) and NaBH3CN (10 equiv.) in MeOH overnight at room temperature. The resulting tagged disaccharide was purified by FluoroFlash column. Then, it was further purified by paper chromatography using Whatman 3 MM chromatography paper (Fisher) that was developed with 100% acetonitrile. Finally, the fluorous-tagged disaccharide (GlcUA-AnMan-Rf) was purified using a C18 column (0.46 × 25 cm, Thermo Scientific) under reverse phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) conditions. The column was eluted with a linear gradient from 90% solution A (0.1% TFA in water) to 50% solution A for 40 min at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, followed by an additional wash for 20 min with 100% solution B (0.1% TFA in acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The product was confirmed by electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry.

The fluorous-tagged hexasaccharides were synthesized from a fluorous-tagged disaccharide GlcUA-AnMan-Rf. To incorporate additional monosaccharides, we supplied the reaction mixture with either KfiA or PmHS2 and the appropriate UDP-monosaccharide donor. As a result, only one sugar residue was transferred to the backbone as described previously (11). A FluoroFlash column was used to separate the tagged oligosaccharides from the unreacted UDP-monosaccharides and enzymes. Briefly, fluorous silica gel (40 μm, Fluorous Technologies) was washed with water and eluted with methanol. The reaction cycle was repeated to prepare hexasaccharide substrates.

Preparation of UDP-GlcNTFA

UDP-GlcNTFA was synthesized using a chemoenzymatic approach as described previously (11). Briefly, 11 mg of GlcNH2-1-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 200 μL of anhydrous methanol and mixed with 60 μL of (C2H5)3N and 130 μ L S-ethyl trifluorothioacetate (Sigma-Aldrich). The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 24 h. The resultant GlcNTFA-1-phosphate was then converted to UDP-GlcNTFA using glucosamine-1-phosphate acetyltransferase/N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GlmU) in a buffer containing 46 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dithiothreitol, 2.5 mM UTP and 0.012 U/μL inorganic pyrophosphatase (Sigma-Aldrich). Recombinant GlmU was expressed in E. coli and purified by a Ni-Agarose column (22). The UDP-GlcNTFA was purified by removing proteins using centrifugal filters (10,000 MWCO, Millipore) followed by dialysis against water using a 1,000 MWCO membrane for 4 h. The product was confirmed by MS analysis. The concentration was determined by a quantitative analysis with PAMN-HPLC using UDP-GlcNAc as a standard.

Removal of the N-trifluoro group from GlcNTFA units

Various amounts of oligosaccharides (50 to 100 μg) were dried and re-suspended in a solution (500 μL) containing CH3OH, H2O and (C2H5)3N (v/v/v = 2:2:1). The reaction was incubated at 37 °C overnight. The samples were dried and reconstituted in H2O to recover de-N-trifluoroacetylated oligosaccharides.

Enzymatic preparation of N-sulfated and 6-O-sulfated oligosaccharides

For the N-sulfation step, the oligosaccharide substrate (20 to 30 μg) was incubated with NST (80 μg) and PAPS (2 equiv.) in 500 μL buffer containing 50 mM MES (pH 7.0) and 1% Triton X-100 overnight at 37 °C. After the reaction was incubated for 12 h, the sulfated oligosaccharide was purified by a C18 column (0.46 × 25 cm, Thermo Scientific) under reverse phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) conditions as described above. To prepare N-[35S]sulfated oligosaccharides, [35S]PAPS (1 to 5×106 cpm) was included in the reaction mixture. To prepare 6-O-sulfated oligosaccharides, a similar procedure was followed except for the replacement of NST with 6-OST-1 and 6-OST-3. The product was confirmed by electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry whenever sufficient amount of samples were prepared.

HPLC analysis

HPLC analyses of the oligosaccharides were carried out as previously described (2, 9,11).

Disaccharide analysis

The oligosaccharides were digested with a mixture of heparin lyases to yield disaccharides. The oligosaccharide (100,000 cpm) was incubated with a mixture of heparin lyase I, II, and III (each at about 20 μg) in 200 μL of 50 mM Na2HPO3, pH 7.0, at 37 °C for 48 h. Additional aliquots of heparin lyase I, II, III were added after 24 h. The recombinant heparin lyases were expressed and purified as described previously (23). The resultant disaccharides were analyzed using a reverse-phase ion pairing (RPIP)-HPLC method as described previously (24). The identities of the disaccharides were determined by coeluting with HS disaccharide standards (Seikagaku America).

Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis

MS analyses were performed on a Thermo LCQ-Deca. Oligosaccharides were dissolved in 1:1 MeOH/H2O in 10 mM ammonium hydroxide. A syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus) was used to introduce the sample via direct infusion (30 μL/min) into the instrument. Experiments were performed in negative ionization mode with a spray voltage of 3.8 kV and a capillary temperature of 200 °C (25). The automatic gain control was set to 1 × 107 for full scan MS and 2 × 107 for MS/MS experiments. For MS/MS experiments, the selection of each precursor ion was achieved using an isolation width of 3 Da and the activation energy was 45% normalized collision energy. The product ions in the MS/MS data were labeled according to Domon-Costello nomenclature (26). The MS and MS/MS data were acquired and processed using Xcalibur 1.3 software.

Results

Preparation of oligosaccharide substrates

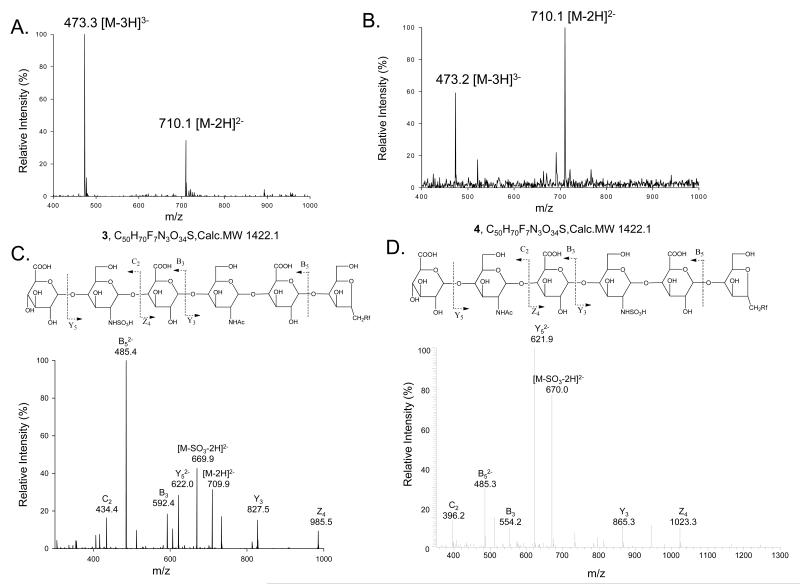

Four oligosaccharide substrates 1-4 were synthesized for this study (Table 1). These oligosaccharides were prepared from a fluorous-tagged disaccharide precursor using bacterial glycosyltransferases, KfiA and PmHS2, as described under Experimental Procedures. The fluorous tag enabled us to purify the products in a single step using a fluorous flush column. The structures of both trisaccharide 1 and tetrasaccharide 2 were confirmed by ESI-MS (Table 1). To prepare the N-sulfated hexasaccharide 3 and 4, we utilized UDP-GlcNTFA as a monosaccharide donor followed by base treatment and N-sulfotransferase modification as described in our prior publication (11). The ESI-MS analysis of both hexasaccharide 3 and 4 demonstrated that the hexasaccharides have molecular masses of 1422.5 and 1422.4, respectively. These molecular masses are very close to the calculated value of 1422.1, suggesting that both hexasaccharide 3 and 4 have six saccharide units and carry a single sulfo group (Fig 2A and 2B).

Table 1.

List of oligosaccharide substrates and products

| Compound | Structure | Calc. MW | Observed MW |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trisaccharide 1a | GlcNAc-GlcUA-AnMan-Rf | 828.7 | 828.6 |

| Tetrasaccharide 2 | GlcUA-GlcNAc-GlcUA- AnMan-Rf |

1004.8 | 1004.8 |

| Hexasaccharide 3b | GlcUA-GlcNS-GlcUA- GlcUAGlcNAc-GlcUA-AnMan-Rf |

1422.1 | 1422.5 |

| Hexasaccharide 4b | GlcUA-GlcNAc-GlcUAGlcNS- GlcUA-AnMan-Rf |

1422.1 | 1422.4 |

| Trisaccharide 5 | GlcNAc6S-GlcUA-AnMan-Rf | 908.7 | 908.6 |

| Tetrasaccharide 6 | GlcUA-GlcNAc6S-GlcUA- AnMan-Rf |

1084.2 | 1084.4 |

| Hexasaccharide 7 | GlcUA-GlcNS6S-GlcUA- GlcNAc6S-GlcUA-AnMan-Rf |

1582.3 | 1582.2 |

| Hexasaccharide 8 | GlcUA-GlcNAc-GlcUA- GlcNAc6s-GlcUA-AnMan-Rf |

1464.2 | 1463.4 |

| Hexasaccharide 9 | GlcUA-GkcNS-GlcUA- GlcNAc6S-GlcUA-AnMan-Rf |

1502.2 | 1501.8 |

Rf represents the fluorous tag.

Both Hexasaccharides 3 and 4 have an identical molecular mass. The location of the N-sulfo group in each hexasaccharide was determined by a tandem MS method as shown in Fig 2.

Fig 2. Structural characterization of N-sulfo hexasaccharide 3 and hexasaccharide 4.

Panel A shows the mass spectrometry spectrum of hexasaccharide 3. Panel B shows the mass spectrometry spectrum of hexasaccharide 4. Panel C shows MS/MS of hexasaccharide 3 (precursor ion selection at m/z 710.1). The fragmentation pattern is depicted at the top. Panel D shows MS/MS of hexasaccharide 4 (precursor ion selection at m/z 710.1). The fragmentation pattern is depicted at the top. The product ions in the MS/MS data were labeled according to Domon-Costello nomenclature (26).

The locations of the sulfo group in each hexasaccharide was determined using tandem MS (MS/MS) (Fig 2C and 2D). For hexasaccharide 3, a daughter ion with an m/z value of 827.5 was detected, which confirmed that the GlcNAc residue is the third residue from the reducing end (Fig 2C, Y3 fragment). We observed a daughter ion with an m/z value of 622.0, demonstrating that the GlcNS residue is the fifth residue from the reducing end (Fig 2D, Y 2-5 fragment). Likewise, for hexasaccharide 4, a daughter ion with an m/z value of 865.3 was observed, which confirmed that the GlcNS residue is the third residue from reducing end (Fig 2D, Y3 fragment).

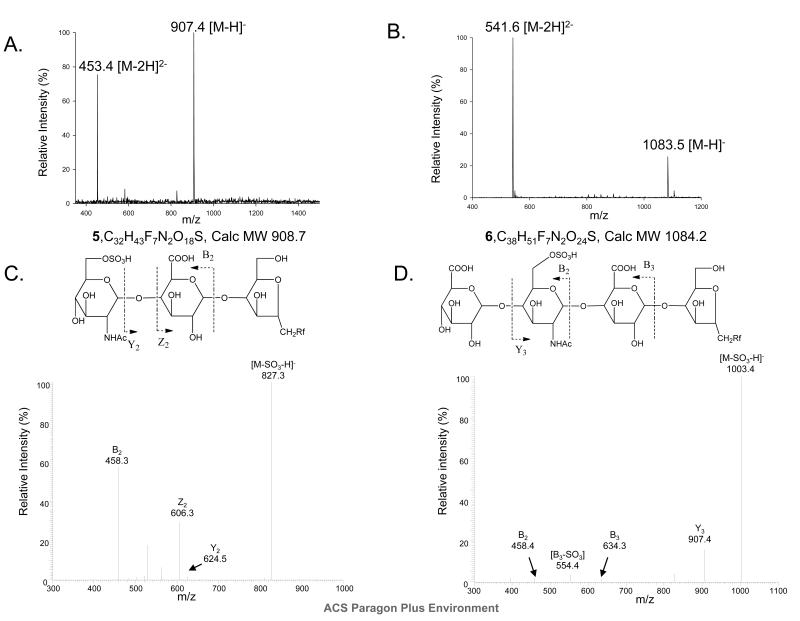

Synthesis of 6-O-sulfated trisaccharide and tetrasaccharide

Incubation of trisaccharide 1 with a mixture of 6-OST-1 and 6-OST-3 yielded 6-O-sulfated trisaccharide 5. Both ESI-MS analysis and tandem MS analysis confirmed the structure of the anticipated product (Fig 3A and 3C). The 6-O-sulfated tetrasacccharide 6 was prepared by incubating tetrasaccharide 2 with 6-OST-1 and 6-OST-3. Mass spectrometry analysis revealed the molecular mass of the 6-O-sulfated tetrasaccharide 6 to be 1084.8, which is close to the calculated mass of 1084.2 (Fig 3B). Tandem MS analysis confirmed the position of the GlcNAc6S residues in 6 (Fig 3D) from two characteristic daughter ions, Y3 (m/z, 907.4) and B2 (m/z, 458.4), which are products of the cleavage of internal glycosidic linkages. Our results demonstrated that the mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 are able to sulfate substrates as short as a trisaccharide. It should be noted that only ~40 % of the trisaccharide was converted to the 6-O-sulfated trisaccharide product even after extensive incubation, suggesting that the sulfation efficiency for a trisaccharide is low.

Fig 3. Structural characterization of 6-O-sulfo trisaccharide 5 and 6-O-sulfo tetrasaccharide 6.

Panel A shows the MS spectrum of 6-O-sulfo trisaccharide 5. Panel B shows the MS spectrum of 6-O-sulfo tetrasaccharide 6. Panel C shows MS/MS of 6-O-sulfo trisaccharide 5 (precursor ion selection at m/z 907.4). The fragmentation pattern is depicted at the top. Panel D shows MS/MS of 6-O-sulfo tetrasaccharide 6 (precursor ion selection at m/z 1083.5). The fragmentation pattern is depicted at the top. The product ions in the MS/MS data were labeled according to Domon-Costello nomenclature (26).

Synthesis of 6-O-sulfated hexasaccharide

We tested whether a mixture of 6-OST-1 and - 3 preferably sulfate GlcNS residues using a hexasaccharide model substrate (hexasaccharide 3, Table 1). Exhaustive incubation of the substrate with 6-OSTs resulted in a major product, hexasaccharide 7. Analysis of the product by ESI-MS revealed its molecular mass to be 1582.2, which is close to the calculated molecular mass (1582.3 Da) for a trisulfated hexasaccharide (Supplementary Fig 1), suggesting that the product carried two 6-O-sulfo groups. The structure of this 6-O-sulfated hexasaccharide was further confirmed by a disaccharide analysis as described below. Our results suggest that the enzymes do not distinguish GlcNAc and GlcNS residues with exhaustive incubation. To compare whether 6-OST-1 alone vs. a mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 produce similar sulfation products, we incubated the enzymes with hexasaccharide 3 under two different concentrations of the sulfo donor, PAPS (Supplementary Fig 2). Under a low concentration of PAPS (0.7 μM), both 6-OST-1 and the mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 yielded one major 35S-labeled hexsaccharide eluted at 35 min on DEAE-HPLC that is consistent with a singly 6-O-sulfated product; likewise, under a high concentration of PAPS (80 μM), the enzymes yielded a major 35S-labeled hexasaccharide eluted at 48 min on DEAE-HPLC that is consistent with the structure of hexasaccharide 7. Taken together, our data suggest that the substrate specificities of 6-OST-1 and the mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 are indistinguishable. Thus, a mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 was used to sulfate the oligosaccharides throughout the study unless otherwise is specified.

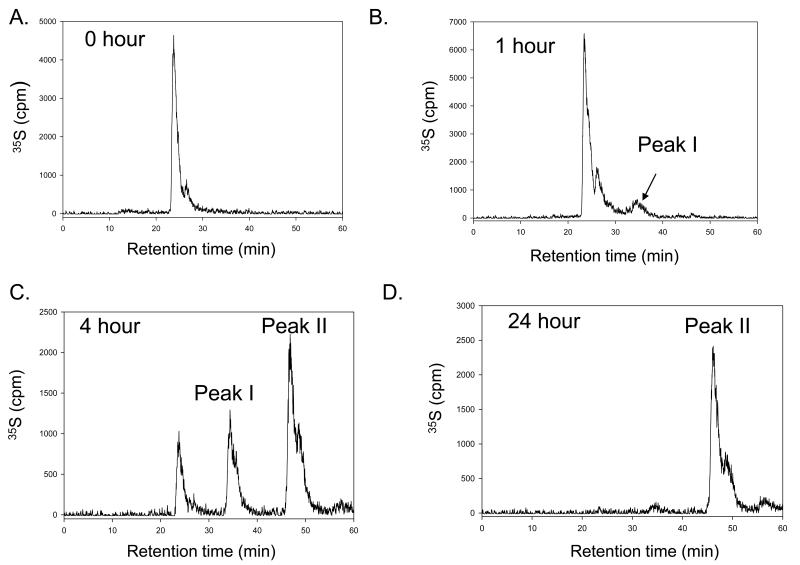

Next, we examined if selective 6-O-sulfation can be achieved under partial or limited sulfation conditions. To facilitate the detection, an N-[35S]sulfated hexasaccharide 3 was prepared, where a GlcNS residue is located closer to the nonreducing end. The 35S-labeled hexasaccharide was then modified by the mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 for various amounts of time. The 6-O-sulfated hexasaccharide products were then analyzed by a DEAE-HPLC column (Fig 4). The starting N-sulfated hexasaccharide 3 had a retention time of 24 min (Fig 4A). After a one-hour reaction time, a small but detectable 35S-labeled peak (Peak I) was observed at 35 min, suggesting that a 6-O-sulfated product was formed (Fig 4B). After four hours of reaction (Fig 4C), the intensity of Peak I increased, and another 35S-labeled peak (Peak II) emerged at 48 min, suggesting that the products contained two hexasaccharides carrying one and two 6-O-sulfo groups, respectively. After twenty-four hours of reaction (Fig 4D), only Peak II was observed, suggesting that the reaction was completed.

Fig 4. Preparation of 6-O-sulfo hexasaccharides with different reaction time.

Panel A shows the HPLC chromatogram of [N-35S]-labeled hexasaccharide 3 using a DEAE-HPLC column. Panel B shows the HPLC chromatogram of [N-35S]sulfo-labeled hexasaccharide 3 using a DEAE-HPLC column after a one-hour reaction time. Panel C shows the HPLC chromatogram of [N-35S]sulfo-labeled hexasaccharide 3 using a DEAE-HPLC column after a four-hour reaction time. Panel D shows the HPLC chromatogram of N-[35S]sulfo-labeled hexasaccharide 3 using a DEAE-HPLC column after 24 hours of reaction time.

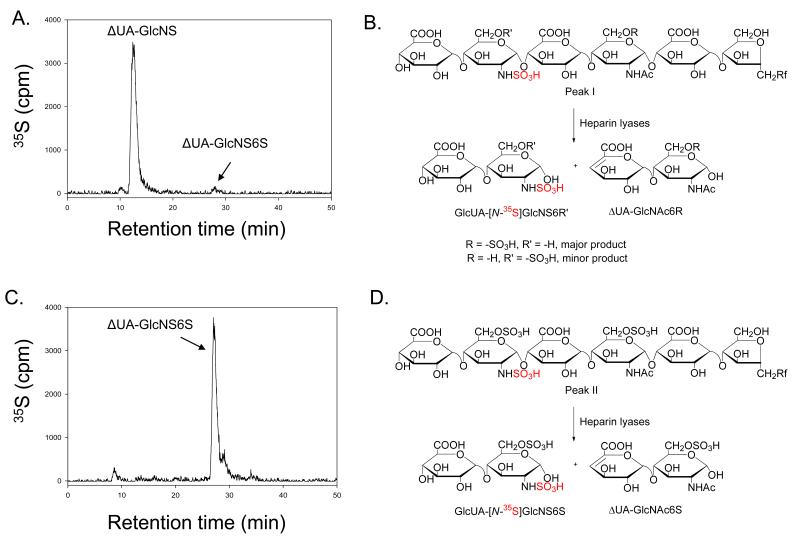

The structures of Peak I and Peak II were confirmed by disaccharide analysis. The result of the disaccharide analysis of Peak I revealed a single 35S-labeled disaccharide with a structure of μUA-[35S]GlcNS and a small but detectable amount of μUA-[N-35S]GlcNS6S (Fig 5A and 5B). This result suggests that the 6-O-sulfo group is predominantly absent on the GlcNS residue that is located closer to the nonreducing end, resulting in a nonradioactively-labeled disaccharide, μUA-GlcNAc6S. The results of the disaccharide analysis also suggest that Peak I is a mixture of two hexasaccharides carrying a single 6-O-sulfo group, and the 6-O-sulfo group is mainly on the residue that is closer to the reducing end, i.e. on the GlcNAc residue. As expected, the disaccharide analysis of Peak II (or hexasaccharide 7) confirmed the presence of a μUA-[N-35S]GlcNS6S product, consistent with our conclusion that Peak II carried two 6-O-sulfo groups (Fig 5C and 5D). Our data suggest that 6-OST-1 and 6-OST-3 kinetically prefer to sulfate the reducing end especially when a GlcNAc residue is located closer to the reducing end. We also conducted a disaccharide analysis of the 35S-labeled peak eluted at 35 min that resulted from the partial 6-O-sulfation of hexasaccharide 3 with 6-OST-1 alone (as shown in Supplementary Fig 2A). As when using a mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3, the 6-O-sulfo group was determined to be at the GlcNAc residue (data not shown).

Fig 5. Determination of the structures of 6-O-sulfo hexasaccharides.

Panel A shows the HPLC chromatogram of the disaccharide analysis of Peak I. The enzymatic reaction involved in the disaccharide analysis of Peak I is shown in Panel B. Panel C shows the HPLC chromatogram of the disaccharide analysis of Peak II. Panel D shows the reaction involved in the disaccharide analysis of Peak II. The radioactively labeled N-sulfo group is colored in red. The disaccharide products from heparin lyases degradation are shown in Panel B and D. The disaccharide analysis was performed on a C18-HPLC column under RPIP-HPLC conditions. The eluent was monitored by an on-line radioactive detector. Under these conditions, the nonradioactively labeled disaccharide (ΔUA-GlcNAc6R shown in Panel B and D) could not be detected.

To examine whether partial 6-O-sulfation occurs at a GlcNS residue located closer to the reducing end, we employed another hexasaccharide substrate (hexasaccharide 4). Unlike hexasaccharide 3, this substrate carries a GlcNS residue that is closer to the reducing end, and it was 35S-labeled at the N-sulfo position. Again, two 35S-labeled peaks, designated as Peaks III and IV, were observed at 35 and 48 min after four hours incubation with a mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 (Supplementary Fig 3A). The disaccharide analysis of Peak III revealed the presence of two disaccharides, μUA-[N-35S]GlcNS and μUA-[N-35S]GlcNS6S with a ratio of 1:2 (Supplementary Fig 3C). Our results suggest that Peak III is a mixture of two hexasaccharides: one hexasaccharide (the major product) carried the 6-O-sulfo group at the GlcNS residue, and another hexasaccharide (the minor product) carried the 6-O-sulfo group at the GlcNAc residue. Peak IV was expected to carry two 6-O-sulfo groups because it was eluted at around 48 min on DEAE-HPLC. The results of using hexasaccharide 4 as a substrate suggest that the mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 displayed a modest to minimal preference for the GlcNS residue when it is located closer to the reducing end.

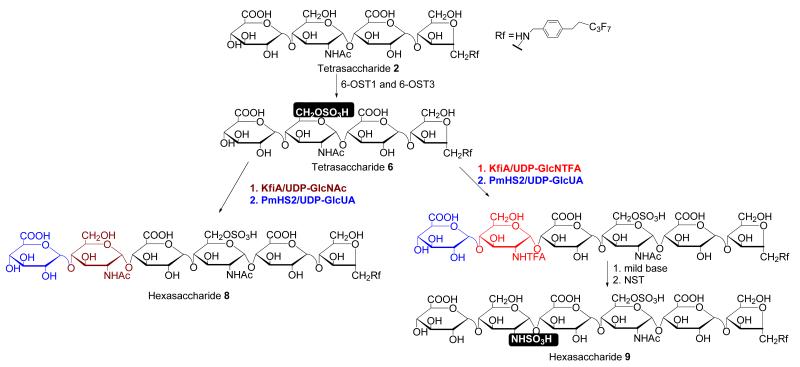

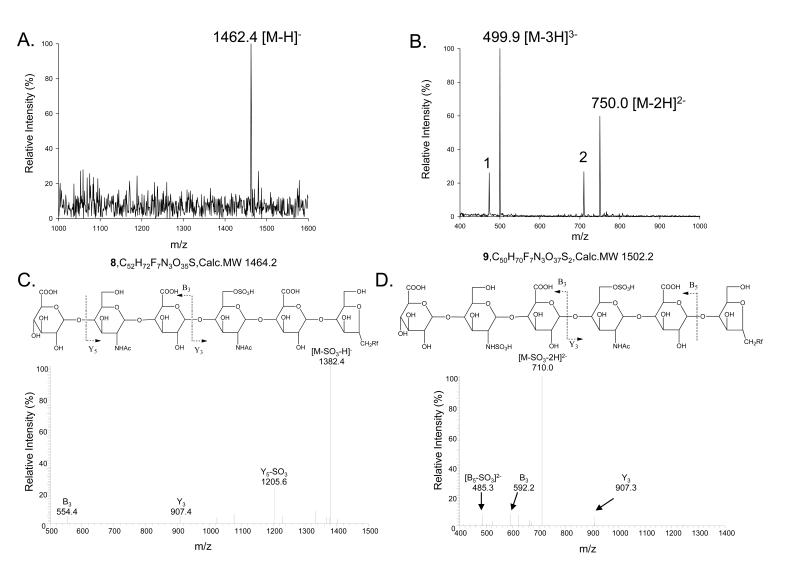

A strategy for preparing selectively 6-O-sulfated hexasaccharides

It is difficult to prepare a hexasaccharide that carries a single 6-O-sulfo group by partial sulfation using a mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 because a mixture of 6-O-sulfated products is obtained. We attempted to use an alternative strategy to achieve this goal. Taking the advantage of the fact that the mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 sulfate short oligosaccharide substrates, we exploited the possibility of elongating oligosaccharides carrying 6-O-sulfo groups by KfiA and PmHS2. We started with 6-O-sulfated tetrasaccharide 6 and elongated it to hexasaccharides using bacterial glycosyltransferases (Fig 6). To demonstrate the utility of this approach, two hexasaccharides (hexasaccharide 8 and 9) were synthesized, which differ at the glucosamine residue closer to the nonreducing end: hexasaccharide 8 has a GlcNAc, and hexasaccharide 9 has a GlcNS residue. The final structures of hexasaccharide 8 and 9 were determined by mass spectrometry. For example, ESI-MS analysis revealed the molecular mass of hexasaccharide 9 to be 1502.2 Da, equal to the calculated molecular mass (1502.2 Da) (Fig 7B). MS/MS analysis confirmed the position of the GlcNS residues in 9 (Fig 7D) from the two characteristic daughter ions, Y3(m/z, 907) and B3 (m/z, 592.3), which are products of the cleavage of an internal glycosidic linkage. Taken together, our results suggest that the elongation approach allowed us to prepare partially 6-O-sulfated hexasaccharides.

Fig 6. Scheme for the synthesis of monosulfated hexasaccharides 8 and 9.

Tetrasaccharide 2 was first 6-O-sulfated to yield the 6-O-sulfated tetrasaccharide. The tetrasaccharide was then elongated by KfiA and pmHS2 using different monosaccharide donors, UDP-GlcNAc and UDP-trifluoroacetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNTFA). To convert the GlcNTFA to a GlcNS in hexasaccharide 9, the hexasaccharide was subjected to mild base treatment followed by N-sulfation with NST.

Fig 7. Structural characterization of 6-O-sulfo hexasaccharides 8 and 9.

Panel A shows the mass spectrometry spectrum of hexasaccharide 8. Panel B shows the mass spectrometry spectrum of hexasaccharide 9. Additional molecular ions are labeled as 1 and 2, where 1 is 473.2 [M-SO3-3H]3− and 2 is 710.0 [M-SO3-2H]2−. Panel C shows MS/MS of hexasaccharide 8 (precursor ion selection at m/z 1462.4). The fragmentation pattern is depicted at the top. Panel D shows MS/MS of hexasaccharide 9 (precursor ion selection at m/z 750.0). The fragmentation pattern is depicted at the top. The product ions in the MS/MS data were labeled according to Domon-Costello nomenclature (26).

We noted that significant desulfation occurred for hexasaccharide 9 while it underwent the ESI-MS analysis. To eliminate the possibility that hexasaccharide 9 is a mixture, an N-35S-labeled hexasaccharide 9 was synthesized following an identical procedure. The 35S-labeled hexasaccharide 9 was eluted at 35 min on a DEAE-HPLC column (Supplementary Fig 4). This retention time is consistent with a hexasaccharide carrying an N-sulfo and a 6-O-sulfo group.

Discussion

The long-term goal of our research is to develop an enzyme-based method to synthesize heparin and structurally defined HS oligosaccharides. A method for selectively placing a 6-O-sulfo group represents an essential part of this initiative. 6-OST is present in three different isoforms (17, 27), and we have obtained purified recombinant 6-OST-1 and 6-OST-3 in large quantities using E. coli expression. Previously, Smeds and colleagues concluded that the three isoforms have no distinguishable substrate specificities (20). Although preparing fully sulfated oligosaccharides using a mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 has been accomplished by our lab (11), placing a 6-O-sulfo group in a specific position remained a challenge. In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of placing a 6-O-sulfo group within an oligosaccharide using a combination of bacterial glycosyl transferases and 6-OSTs. In our approach, we preassemble the 6-O-sulfo group on a tetrasaccharide. The 6-O-sulfated tetrasaccharide can be then elongated to a hexasaccharide with high efficiency. Our study used a mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3 to carry out most of the experiments because we did not detect any difference in substrate specificities between 6-OST-1 alone vs a mixture of 6-OST-1 and -3, although the mixture may provide higher 6-O-sulfation capacity to avoid incomplete 6-O-sulfation. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that subtle differences in substrate specificities among 6-OST isoforms exist at the polysaccharide level.

The results from our study also provide insights into the substrate specificities of 6-OSTs using synthetic oligosaccharide model substrates. As in previous reports, the enzymes were found to sulfate both GlcNAc and GlcNS residues (20). We observed that a trisaccharide is sufficiently long to serve as a sulfo group receptor. Furthermore, we observed that it is very difficult to obtain a hexasaccharide carrying a single 6-O-sulfo group simply by shortening the reaction time. Our results found that the combination of 6-OST-1 and -3 has a clear preference for sulfating the N-acetylated glucosamine residue closer to the reducing end of a hexasaccharide substrate. However, this preference was significantly reduced when this residue is replaced with a GlcNS residue. A report by Jemth and colleagues also demonstrated that 6-OSTs prefer to sulfate an internal glucosamine residue that is closer the reducing end using different oligosaccharide substrates (28).

In summary, we developed an enzyme-based method that can prepare oligosaccharides carrying fully 6-O-sulfo groups. Our method is also capable of introducing a single 6-O-sulfo group followed by elongation of the oligosaccharides using bacterial glycosyl transferases. By doing so, we are able to introduce a 6-O-sulfo group to a glucosamine located in the middle of a target oligosaccharide. Although the 6-O-sulfated tetrasaccharide has only been extended to hexasaccharides in the current study, it is possible to further extend it to larger oligosaccharides (22). However, our method is unable to introduce a 6-O-sulfo group at the glucosamine residue located closer to the nonreducing end when the reducing end glucosamine residues are devoid of 6-O-sulfation. It should be noted that HS 6-O-sulfatases remove 6-O-sulfo group from HS in vivo (18,19). It could be possible to modify fully 6-O-sulfated HS substrates by 6-O-sulfatases so that a 6-O-sulfo group remains at the glucosamine residue located at the nonreducing end. Given the important role of 6-O-sulfation for the function of HS, our method should provide a powerful tool to synthesize structurally defined oligosaccharides to probe the structure and activity relationship of HS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Yongmei Xu for comments on the HPLC analyses and disaccharide analyses and for providing the E. coli-expressed and purified 6-OST-1 and 6-OST-3. The authors also thank Elizabeth Pempe and Courtney Jones for critically reading the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- HS

heparan sulfate

- UDP

uridine 5′-diphosphate

- UTP

uridine 5′-triphosphate

- UDP-GlcNAc

UDP-N-acetylglucosamine

- UDP-GlcNTFA

UDP-N-trifluoroacetylglucosamine

- UDP-GlcUA

UDP-N-glucuronic acid

- GlcN-1-P

glucosamine-1-phosphate.

- GlmU

glucosamine-1-phosphate acetyltransferase/N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate uridyltransferase

- PAPS

3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate

Footnotes

This work is supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants AI50050, HL094463 and AI074775.

Supporting Information

Additional data for structural characterization of hexasaccharide 7, Peak III and Peak IV and purity determination of hexasaccharide 9 are presented under Supplementary Information, which is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Peterson SP, Frick A, Liu J. Designing of biologically active heparan sulfate and heparin using an enzyme-based approach. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:61–627. doi: 10.1039/b803795g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Chen J, Jones CL, Liu J. Using an enzymatic combinatorial approach to identify anticoagulant heparan sulfate structures. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Petitou M, van Boeckel CAA. A synthetic antithrombin III binding pentasaccharide is now a drug! What comes next? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3118–3133. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Baleux F, Loureiro-Morais L, Hersant Y, Clayette P, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Bonnaffe D, Lortat-Jacob H. A synthetic CD4-heparan sulfate glycoconjugate inhibits CCR5 and CXCR4 HIV-1 attachment and entry. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:743–748. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shriver Z, Raguram S, Sasisekharan R. Glycomics: A pathway to a class of new and improved therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:863–873. doi: 10.1038/nrd1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gama C, Tully SE, Sotogaku N, Clark PM, Rawat M, Vaidehi N, Goddard WA, Nishi A, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Sulfation patterns of glycosaminoglycans encode molecular recognition and activity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:467–473. doi: 10.1038/nchembio810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).de Paz JL, Seeberger PH. Deciphering the glycosaminoglycan code with the help of microarrays. Mol. Biosyst. 2008;4:707–711. doi: 10.1039/b802217h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Liu J, Pedersen LC. Anticoagulant heparan sulfate: Structural specificity and biosynthesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007;74:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0722-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Chen J, Avci FY, Muñoz EM, McDowell LM, Chen M, Pedersen LC, Zhang L, Linhardt RJ, Liu J. Enzymatically redesigning of biologically active heparan sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:42817–42825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504338200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zhang Z, McCallum SA, Xie J, Nieto L, Corzana F, Jiménez-Barbero J, Chen M, Liu J, Linhardt RJ. Solution structure of chemoenzymatically synthesized heparin and its precursors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12998–13007. doi: 10.1021/ja8026345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Liu R, Xu Y, Chen M, Weïwer M, Zhou X, Bridges AS, DeAngelis PL, Zhang Q, Linhardt RJ, Liu J. Chemoenzymatic design of heparan sulfate oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:34240–34249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wang L, Brown JR, Varki A, Esko JD. Heparin’s anti-inflammatory effects require glucosamine 6-O-sulfation and are mediated by blockade of L- and P-selectins. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:127–136. doi: 10.1172/JCI14996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lundin L, Larsson H, Kreuger J, Kanda S, Lindahl U, Salmivirta M, Claesson-Welsh L. Selectively desulfated heparin inhibits fibroblast growth factor-induced mitogenicity and angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:24653–24660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908930199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).McDowell LM, Frazier B, Studelska DR, Giljum K, Chen J, Liu J, Yu K, Ornitz DM, Zhang L. Inhibition or activation of Apert syndrome FGFRs (S252W) signaling by specific glycosaminoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6924–6930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Habuchi H, Nagai N, Sugaya N, Atsumi F, Stevens RL, Kimata K. Mice deficient in HS 6-O-sulfotransferase-1 exhibit defective heparan sulfate biosynthesis, abnormal placentation, and late embryonic lethality. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:15578–15588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kamimura K, Koyama T, Habuchi H, Ueda R, Masayuki M, Kimata K, Nakato H. Specific and flexible roles of heparan sulfate modifications in Drosophila FGF signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:773–778. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Habuchi H, Tanaka M, Habuchi O, Yoshida K, Suzuki H, Ban K, Kimata K. The occurence of three isoforms of heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase having different specificities for hexuronic acid adjacent to the targeted N-sulfoglucosamine. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:2859–2868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ai X, Do AT, Kusche-Gullberg M, Lindahl U, Lu K, Emerson CP., Jr. Substrate specificity and domain functions of extracellular heparan sulfate 6-O-endosulfatases, QSulf1 and QSulf2. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:4969–4976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ai X, Do AT, Lozynska O, Kusche-Gullberg M, Lindahl U, Emerson CP., Jr. QSulf1 remodels the 6-O sulfation states of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans to promote Wnt signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:341–351. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Smeds E, Habuchi H, Do A-T, Hjertson E, Grundberg H, Kimata K, Lindahl U, Kusche-Gullberg M. Substrate specificities of mouse heparan sulphate glucosaminyl 6-O-sulfotransferases. Biochem. J. 2003;372:371–380. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kakuta Y, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M, Pedersen LC. Crystal structure of the sulfotransferase domain of human heparan sulfate N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:10673–10676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Chen M, Bridges A, Liu J. Substrate specificities of recombinant N-acetyl-D-glucosaminyl transferase (KfiA) Biochemistry. 2006;45:12358–12365. doi: 10.1021/bi060844g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Duncan MB, Liu M, Fox C, Liu J. Characterization of the N-deacetylase domain from the heparan sulfate N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase 2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;339:1232–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Liu J, Shworak NW, Sinaÿ P, Schwartz JJ, Zhang L, Fritze LMS, Rosenberg RD. Expression of heparan sulfate D-glucosaminyl 3-O-sulfotransferase isoforms reveals novel substrate specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:5185–5192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Saad OM, Leary JA. Compositional analysis and quantification f heparin and heparan sulfate by electrospray ionization ion trap mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:2985–2995. doi: 10.1021/ac0340455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Domon B, Costello CE. A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugates. Glycoconj. J. 1988;5:397–409. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Habuchi H, Habuchi O, Kimata K. Sulfation pattern in glycosaminoglycan: does it have a code? Glycoconj. J. 2002;21:47–52. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000043747.87325.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Jemth P, Smeds E, Do A-T, Habuchi H, Kimata K, Lindahl U, Kusche-Gullberg M. Oligosaccharide library-based assessment of heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransfer substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:24371–24376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.