Abstract

Background

A growing body of evidence indicates that statins decrease perioperative cardiovascular risk and that these drugs may be particularly efficacious in diabetes. Diabetes or hyperglycemia abolish the cardioprotective effects of ischemic preconditioning (IPC). We tested the hypothesis that simvastatin restores the beneficial effects of IPC during hyperglycemia through a nitric oxide (NO)-mediated mechanism.

Methods

Myocardial infarct size was measured in dogs (n=76) subjected to coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion in the presence or absence of hyperglycemia (300 mg/dl) with or without IPC in separate groups. Additional dogs received simvastatin (20 mg orally daily for 3 days) in the presence or absence of IPC and hyperglycemia. Other dogs were pretreated with N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME; 30 mg intracoronary) with or without IPC, hyperglycemia and simvastatin.

Results

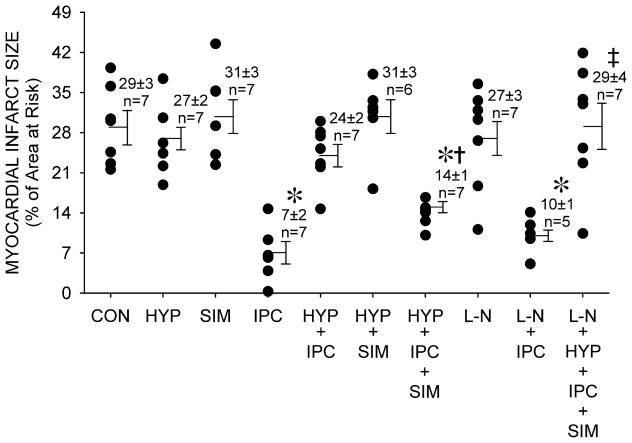

IPC significantly (P<0.05) reduced infarct size (n=7, 7±2%) as compared to control (n=7, 29±3%). Hyperglycemia (n=7), simvastatin (n=7) and L-NAME alone (n=7), and simvastatin with hyperglycemia (n=6) did not alter infarct size. Hyperglycemia (n=7, 24±2%), but not L-NAME (n=5, 10±1%), blocked the protective effects of IPC. Simvastatin restored the protective effects of IPC in the presence of hyperglycemia (n=7, 14±1%), and this beneficial action was blocked by L-NAME (n=7, 29±4%).

Conclusions

The results indicate that simvastatin restored the cardioprotective effects of IPC during hyperglycemia by NO-mediated signaling. The results also suggest that enhanced cardioprotective signaling could be a mechanism for statin-induced decreases in perioperative cardiovascular risk.

INTRODUCTION

The enzyme 3-hydroxyl-3-methylglutaryl (HMG) CoA reductase catalyzes the rate-limiting step in cholesterol synthesis. Inhibitors of this enzyme are collectively called “statins” and prevent the conversion of HMG CoA to mevalonic acid. Statins are commonly prescribed to reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, a major risk factor for coronary artery disease. The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study demonstrated marked reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and overall cardiovascular mortality in patients with hypercholesterolemia treated with this statin 1. More recent clinical trials confirmed these important results and further indicated that statins also protect against atherosclerotic disease in patients with normal cholesterol levels 2. Notably, statins appear to confer relatively greater cardiovascular benefits in diabetic patients as compared to those without the disease 3. The results of these and other studies have stimulated an intense interest in mechanisms responsible for the cardioprotective effects of statins that may occur independent of reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Increased availability of nitric oxide (NO), preservation of endothelial function, and antithrombotic and antiinflammatory effects are key mechanisms that may contribute to statin-induced protection 4.

Previous investigations demonstrated that diabetes and hyperglycemia impair NO availability and abolish the cardioprotective effects of ischemic preconditioning (IPC) 5,6, volatile anesthetic-induced preconditioning 7,8, and activation of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate-regulated potassium (KATP) channels 9. Whether endogenous cardioprotective signal transduction known to be disrupted by diabetes and hyperglycemia may be restored by pharmacological therapy is unknown. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that the HMG CoA inhibitor simvastatin restores the beneficial effects of IPC during hyperglycemia through a NO-mediated mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All experimental procedures and protocols used in this investigation were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Furthermore, all conformed to the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals 10 of the American Physiologic Society and were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 11.

General Preparation

Implantation of instruments has been previously described in detail 12. Briefly, mongrel dogs of either sex were anesthetized with sodium barbital (200 mg/kg) and sodium pentobarbital (15 mg/kg) and ventilated using positive pressure with an air and oxygen mixture after tracheal intubation. Arterial blood gases were maintained within a physiological range by adjustment of tidal volume and respiratory rate. Temperature was maintained with a heating blanket. A 7F, dual micromanometer-tipped catheter was inserted into the aorta and left ventricle (LV) for measurement of aortic and LV pressures and the maximum rate of increase of LV pressure (+dP/dtmax). Heparin-filled catheters were inserted into the left atrial appendage and the right femoral artery for administration of radioactive microspheres and withdrawal of reference blood flow samples, respectively. A catheter was also inserted in the right femoral vein for saline administration. A 1 cm segment of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was isolated immediately distal to the first diagonal branch, and a silk ligature was placed around the vessel for production of coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. Hemodynamics were continuously monitored on a polygraph during experimentation and digitized using a computer interfaced with an analog to digital converter.

Experimental Protocol

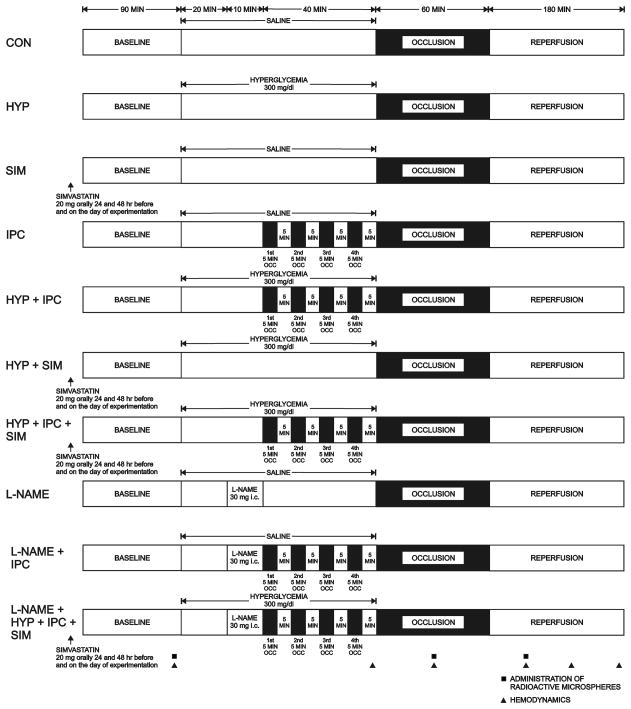

Baseline systemic hemodynamics were recorded 90 min after instrumentation was completed and calibrated. All dogs were subjected to a 60 min LAD occlusion followed by 3 h of reperfusion (Figure 1). In four experimental groups, dogs were randomly assigned to receive 0.9% saline or 15% dextrose in water to increase blood glucose concentrations to 300 mg/dl with or without IPC (four 5 min LAD occlusions interspersed with 5 min reperfusion conducted immediately before prolonged LAD occlusion). Additional groups of dogs pretreated with oral administration of simvastatin for 3 days (20 mg daily; 24 and 48 h before and on the day of experimentation) were studied in the presence or absence of IPC and hyperglycemia. This dose and duration of simvastatin exposure was based on evidence in the literature that short term statin use increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression 13. Three final groups of dogs received the NO synthase inhibitor N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) with or without IPC or the combination of IPC, hyperglycemia and simvastatin. L-NAME (30 mg) 14 was infused intracoronary (0.1 ml/min via a small catheter [PE-20]) over 10 min immediately before brief IPC stimuli. Regional myocardial blood flow was measured under baseline conditions, during LAD occlusion and after 1 h of reperfusion. Dogs were excluded from the analysis if: 1) intractable ventricular fibrillation occurred; or 2) subendocardial coronary collateral blood flow exceeded 0.15 ml/min/g 15.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the experimental protocol.

Measurement of Myocardial Infarct Size

At the end of each experiment, myocardial infarct size was measured as previously described in detail 5,16. Briefly, the LV area at risk for infarction (AAR) was separated from the normal area, and the two regions were incubated at 37° C for 20–30 min in 1% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride in 0.1 M phosphate buffer adjusted to pH 7.4. After overnight storage in 10% formaldehyde, infarcted and noninfarcted myocardium within the AAR were carefully separated and weighed. Infarct size was expressed as a percentage of the AAR.

Determination of Regional Myocardial Blood Flow

Carbonized plastic microspheres [15±2 μm (standard deviation) in diameter] labeled with 141Ce, 103Ru, or 95Nb were used to measure regional myocardial perfusion as previously described 17. Transmural tissue samples were selected from the ischemic region (distal to the LAD occlusion) and were subdivided into subepicardial, midmyocardial, and subendocardial layers of approximately equal thickness. Samples were weighed, placed in scintillation vials, and the activity of each isotope determined. Similarly, the activity of each isotope in the reference blood flow sample was assessed. Tissue blood flow ml/min/g was calculated as Qr x Cm/Cr where Qr = rate of withdrawal of the reference blood flow sample (ml/min); Cm = activity (cpm/g) of the myocardial tissue sample; and Cr = activity (cpm) of the reference blood flow sample. Transmural blood flow was considered as the average of subepicardial, midmyocardial and subendocardial blood flows.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of data within and between groups was performed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test. All data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). Each hemodynamic measurement in Table 1 (HR, MAP, LVSP, LVEDP, LV+dP/dt), blood glucose and transmural myocardial perfusion in the ischemic region were analyzed separately by repeated measures ANOVA. First an overall factorial model was fitted, and the presence of any group-, time- or group-time interaction effect was evaluated; the result of this analysis is presented with each table. The Huynh-Feldt correction for sphericity was used when testing the within animal effects. Whenever statistically significant effects (p<0.05) were found, we proceeded with more detailed post-hoc comparisons. Whenever significant interactions were found, each experimental group and each time point were analyzed separately. The type I error rate was controlled at 0.05 within each group and each time point by the use of the Student-Newman-Keuls test. While this application of the SNK test does not guarantee overall control of the type I error rate by itself, these tests were protected by the significant result of the global test.

Table 1.

Systemic Hemodynamics

| Reperfusion

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Preocclusion | 30 min CAO | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | |

| HR (beats/min) | ||||||

| CONTROL | 135±6 | 131±7 | 133±6 | 122±5 | 125±6 | 124±4 |

| HYP | 137±5 | 147±4 | 131±4 | 128±7 | 129±7 | 133±6 |

| SIM | 143±4 | 134±4* | 135±4* | 122±3* | 122±2* | 121±2* |

| IPC | 133±4 | 128±5 | 128±6 | 122±4 | 119±6* | 118±7* |

| HYP + IPC | 135±6 | 131±6 | 138±5 | 135±4 | 134±6 | 135±6 |

| HYP + SIM | 137±6 | 136±6 | 120±10 | 133±6 | 133±7 | 134±8 |

| HYP + IPC + SIM | 138±7 | 138±3 | 138±3 | 125±4* | 128±5 | 128±6 |

| L-NAME | 135±9 | 117±10* | 114±8* | 112±6* | 115±9* | 115±10* |

| L-NAME + IPC | 124±4 | 110±7 | 115±8 | 110±6 | 110±3 | 105±6* |

| L-NAME+HYP+IPC+SIM | 128±5 | 116±4* | 118±5* | 112±4* | 111±4* | 112±4* |

| MAP (mmHg) | ||||||

| CONTROL | 99±4 | 100±3 | 91±5 | 97±5 | 104±6 | 102±5 |

| HYP | 100±4 | 122±12* | 93±4 | 100±5 | 103±4 | 98±5 |

| SIM | 113±3 | 110±1 | 100±5* | 98±5* | 107±5 | 105±5 |

| IPC | 91±3 | 91±4 | 87±4 | 97±5 | 101±5 | 96±3 |

| HYP + IPC | 106±7 | 111±4 | 100±5 | 117±2 | 115±4 | 115±1 |

| HYP + SIM | 108±4 | 108±4 | 77±7* | 82±3* | 88±5* | 88±6* |

| HYP + IPC + SIM | 109±6 | 102±5 | 95±5 | 101±4 | 104±4 | 99±6 |

| L-NAME | 103±6 | 122±5* | 104±8 | 105±9 | 108±9 | 112±9 |

| L-NAME+IPC | 111±8 | 112±7 | 102±6 | 89±4* | 103±5 | 101±9 |

| L-NAME+HYP+IPC+SIM | 98±1 | 105±4 | 94±3 | 100±6 | 104±6 | 100±4 |

| LVSP (mmHg) | ||||||

| CONTROL | 110±5 | 111±4 | 97±5 | 101±6 | 112±5 | 109±5 |

| HYP | 115±5 | 137±13*† | 100±5 | 108±4 | 111±5 | 104±4 |

| SIM | 126±4 | 126±2 | 109±5* | 105±6* | 114±5 | 112±6* |

| IPC | 100±5 | 100±5 | 91±5 | 102±6 | 104±5 | 100±2 |

| HYP + IPC | 121±9 | 125±4 | 108±6 | 124±3 | 122±4 | 124±3 |

| HYP + SIM | 119±4 | 119±5 | 88±6* | 92±3* | 99±5* | 98±5* |

| HYP + IPC + SIM | 120±7 | 112±6 | 100±7* | 105±5 | 110±3 | 102±5* |

| L-NAME | 115±6 | 134±5* | 110±8 | 111±9 | 114±9 | 117±9 |

| L-NAME + IPC | 120±10 | 121±8 | 108±8 | 92±5* | 108±5 | 106±9 |

| L-NAME+HYP+IPC+SIM | 109±2 | 115±5 | 100±3 | 104±6 | 107±6 | 103±5 |

| LVEDP (mmHg) | ||||||

| CONTROL | 5±1 | 5±1 | 15±2* | 18±3* | 16±3* | 16±2* |

| HYP | 5±2 | 8±2 | 11±2 | 11±1 | 13±2* | 10±2 |

| SIM | 6±1 | 6±1 | 14±1* | 19±3* | 16±2* | 16±2* |

| IPC | 6±1 | 6±1 | 9±1 | 10±2* | 11±2* | 12±2* |

| HYP + IPC | 7±1 | 7±1 | 9±2 | 10±2 | 12±3 | 13±2* |

| HYP + SIM | 10±1 | 9±1 | 16±3* | 14±2* | 13±2 | 13±2 |

| HYP + IPC + SIM | 7±1 | 9±1 | 12±2 | 20±2* | 14±3 | 13±2 |

| L-NAME | 9±1 | 11±2 | 22±2*† | 18±1* | 21±4* | 20±4* |

| L-NAME + IPC | 6±2 | 10±2 | 13±3 | 16±3* | 15±4* | 16±3* |

| L-NAME+HYP+IPC+SIM | 8±1 | 7±1 | 12±1 | 14±2* | 16±2* | 15±2* |

| LV +dP/dtmax (mmHg/s) | ||||||

| CONTROL | 1860±200 | 1970±230 | 1540±140* | 1360±130* | 1350±110* | 1220±50* |

| HYP | 1870±130 | 2340±320* | 1520±90 | 1580±120 | 1540±70 | 1420±70 |

| SIM | 2170±110 | 2030±110 | 1720±130* | 1450±80* | 1500±80* | 1440±80* |

| IPC | 1680±130 | 1640±150 | 1600±140 | 1420±150* | 1280±90* | 1190±90* |

| HYP + IPC | 2090±190 | 2210±110 | 1950±100 | 1680±90* | 1540±100* | 1540±70* |

| HYP + SIM | 1750±60 | 1920±70 | 1390±150* | 1430±80* | 1470±90* | 1430±100* |

| HYP + IPC + SIM | 1970±160 | 1930±120 | 1770±100* | 1530±90* | 1520±90* | 1460±120* |

| L-NAME | 1780±130 | 1460±110* | 1230±100* | 1190±110* | 1240±100* | 1250±110* |

| L-NAME + IPC | 1840±300 | 1430±110 | 1460±110 | 1100±30* | 1170±40* | 1100±150* |

| L-NAME+HYP+IPC+SIM | 1740±110 | 1600±110 | 1360±100* | 1220±50* | 1160±50* | 1110±40* |

| Repeated Measures ANOVA Results for Systemic Hemodynamics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Group | Time | Group*Time |

| HR | F9,57 = 2.55, P = 0.0154 | F5,285 = 19.53, P <0.0001 | F45,285 = 1.64, P = 0.0298 |

| MAP | F9,57 = 2.38, P = 0.0234 | F5,285 = 13.68, P <0.0001 | F45,285 = 2.06, P = 0.0007 |

| LVSP | F9,53 = 2.52, P = 0.0175 | F5,265 = 23.42, P <0.0001 | F45,265 = 1.69, P = 0.0140 |

| LVEDP | F9,53 = 2.10, P = 0.0462 | F5,265 = 48.70, P <0.0001 | F45,265 = 1.69, P = 0.0521 |

| LV +dP/dtmax | F9,53 = 3.44, P = 0.0021 | F5,265 = 84.33, P <0.0001 | F45,265 = 1.63, P = 0.0210 |

Data are mean ± SEM

Significantly (p<0.05) different from baseline.

Significantly (p<0.05) different from the respective value in the CONTROL group.

CAO = coronary artery occlusion; HR = heart rate; MAP = mean aortic blood pressure; LVSP and LVEDP = left ventricular systolic and end-diastolic pressures, respectively; LV+dP/dtmax = maximal rate of increase of left ventricular pressure; IPC = ischemic preconditioning; HYP = hyperglycemia; SIM = simvastatin.

RESULTS

Seventy-six dogs were instrumented to obtain 67 successful experiments. Four dogs were excluded due to intractable ventricular fibrillation (1 in the simvastatin alone group; 1 in the L-NAME alone group; and 2 in the L-NAME+IPC group). Nine dogs were excluded because subendocardial collateral blood flow exceeded 0.15 ml/min/g (1 in the control group; 1 in the hyperglycemia alone group; 1 in the hyperglycemia+IPC group; 3 in the simvastatin alone group; and 3 in the L-NAME+IPC group).

Hemodynamics and Blood Glucose Concentrations

There were no differences in baseline hemodynamics among experimental groups (Table 1). Hyperglycemia increased mean arterial and LV systolic pressures and LV dP/dtmax before coronary occlusion. L-NAME caused transient increases in mean arterial and LV systolic pressures and decreases in heart rate and LV dP/dtmax. Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure increased to a greater extent during coronary occlusion in dogs pretreated with L-NAME as compared to 0.9% saline. There were no other significant differences in hemodynamics among groups during coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. There were no differences in baseline blood glucose concentrations among groups. Blood glucose concentrations (Table 2) were unchanged over time in dogs receiving 0.9% saline. Infusion of dextrose increased blood glucose concentration before coronary occlusion. Blood glucose concentrations returned to baseline values in hyperglycemic dogs during coronary occlusion and reperfusion. Blood glucose concentrations were modestly decreased during LAD occlusion and reperfusion in simvastatin-pretreated dogs in the absence of hyperglycemia.

Table 2.

Blood Glucose Concentrations (mg/dl)

| Reperfusion

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Preocclusion | 30 min CAO | 1 h | 3 h | |

| CONTROL | 83±6 | --- | 83±6 | 76±6 | 72±7 |

| HYP | 83±4 | 307±8* | 108±12* | 73±7 | 77±8 |

| SIM | 81±6 | --- | 68±4* | 60±3* | 56±3* |

| IPC | 71±7 | --- | 59±6 | 67±5 | 63±8 |

| HYP + IPC | 77±5 | 293±13* | 106±25 | 82±11 | 76±6 |

| HYP + SIM | 93±6 | 309±47* | 160±49 | 92±11 | 91±3 |

| HYP + IPC + SIM | 75±3 | 309±13* | 77±13 | 78±10 | 81±7 |

| L-NAME | 88±6 | --- | 72±7 | 86±15 | 76±7 |

| L-NAME + IPC | 74±7 | --- | 65±7 | 68±6 | 63±4 |

| L-NAME+HYP+IPC+ SIM | 78±3 | 313±16* | 85±10 | 63±8 | 74±3 |

| Repeated Measures ANOVA Results for Blood Glucose | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Group | Time | Group*Time |

| Blood Glucose | F7,38 = 15.86, P <0.0001 | F4,152 = 161.0, P <0.0001 | F28,152 = 14.89, P <0.0001 |

| Blood Glucose (without Preocclusion) | F9,46 = 2.66, P =0.0143 | F3,138 = 3.04, P = 0.0645 | F27,138 = 0.94, P = 0.5202 |

Data are mean±SEM

Significantly (p<0.05) different from baseline.

CAO = coronary artery occlusion; IPC = ischemic preconditioning; HYP = hyperglycemia; SIM = simvastatin.

Myocardial Infarct Size and Coronary Collateral Blood Flow

No differences in LV AAR were observed between groups (control: n=7, 41±1%; hyperglycemia alone: n=7, 36±2%; simvastatin alone: n=7, 36±2%; IPC alone: n=7, 43±3%; hyperglycemia+IPC: n=7, 33±3%; hyperglycemia+simvastatin: n=6, 36±2%; hyperglycemia+IPC+simvastatin: n=7, 39±2%; L-NAME alone: n=7, 37±3%; L-NAME+IPC: n=5, 35±4%; hyperglycemia+IPC+simvastatin+L-NAME: n=7, 37±2%). IPC significantly (P<0.05) reduced infarct size (7±2% of the LV AAR) as compared to control (29±3%; figure 2). Hyperglycemia, simvastatin, L-NAME alone, and hyperglycemia with simvastatin did not alter infarct size (27±2, 31±3, 27±3 and 31±3%, respectively). Hyperglycemia (24±2%), but not L-NAME (10±1%), blocked the protective effects of IPC. Simvastatin restored the protective effect of IPC in the presence of hyperglycemia (14±1%) and this beneficial effect was blocked by L-NAME (29±4%). Transmural myocardial blood flow was similar in each experimental group under baseline conditions (Table 3). LAD occlusion produced similar reductions in transmural myocardial perfusion. There were no differences in coronary collateral blood flow among groups.

Figure 2.

Myocardial infarct size expressed as a percentage of the left ventricular area at risk during control (CON) conditions, hyperglycemia (HYP), and simvastatin pretreatment (SIM) in the presence or absence of ischemic preconditioning (IPC) with or without N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-N). Data are mean±SEM. *Significantly (P<0.05) different from CON. †Significantly (P<0.05) different from HYP+IPC. ‡Significantly (P<0.05) different from HYP+IPC+SIM.

Table 3.

Transmural Myocardial Perfusion in the Ischemic (LAD) Region (ml/min/g)

| Baseline | 30 min CAO | 1 h reperfusion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL | 1.23±0.17 | 0.08±0.02* | 1.79±0.20* |

| HYP | 0.75±0.12 | 0.09±0.02* | 1.92±0.24* |

| SIM | 1.36±0.10 | 0.04±0.01* | 1.68±0.10* |

| IPC | 0.80±0.04 | 0.09±0.01* | 1.62±0.29* |

| HYP + IPC | 1.16±0.14 | 0.08±0.02* | 1.84±0.17* |

| HYP + SIM | 0.96±0.11 | 0.10±0.03* | 1.54±0.27* |

| HYP + IPC + SIM | 1.46±0.26 | 0.05±0.02* | 1.64±0.12 |

| L-NAME | 0.73±0.10 | 0.05±0.01* | 1.45±0.43* |

| L-NAME + IPC | 0.76±0.09 | 0.06±0.02* | 1.14±0.24 |

| L-NAME + HYP + IPC + SIM | 0.92±0.07 | 0.05±0.01* | 1.25±0.27 |

| Repeated Measures ANOVA Results for Transmural Myocardial Perfusion | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Group | Time | Group*Time |

| Myocardial Perfusion | F9,57 = 1.80, P=0.0878 | F2,114 = 245.36, P<0.0001 | F18,114= 1.57, P =0.0936 |

Data are mean±SEM

Significantly (p<0.05) different from baseline.

CAO = coronary artery occlusion; IPC = ischemic preconditioning; HYP = hyperglycemia; SIM = simvastatin.

DISCUSSION

Many of the adverse consequences of diabetes and hyperglycemia are thought to result from the combination of reduced NO activity and increased generation of reactive oxygen species 18. However, the potentially adverse interactions between hyperglycemia, NO and myocardial signal transduction responsible for protection against ischemic injury have not been fully defined. Ischemic preconditioning is a powerful endogenous mechanism that protects myocardium against infarction 19. Many diverse preconditioning stimuli are known to elicit protection of ischemic myocardium by activating common signal transduction pathways including membrane bound receptors, reactive oxygen species, intracellular kinases, regulatory G proteins, and mitochondrial KATP channels 20. NO derived from endothelial nitric oxide synthase has also been identified as a critical trigger of cardioprotection. Prolonged ischemia and reperfusion was associated with the loss of cardiac endothelial nitric oxide synthase protein, but IPC completely prevented this endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficit concomitant with enhanced nitric oxide synthase activity and intracellular cGMP concentration 21. Recovery of contractile function was enhanced and cGMP concentration increased by IPC in isolated rat hearts, and these actions were attenuated by nitric oxide synthase inhibitors or a guanylate cyclase inhibitor 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolol-[4,3-a]quinoxaline-1-one 22. Preconditioning with simulated ischemia also attenuated death of isolated cardiomyocytes, and this effect was blocked by the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-monomethyl-L-arginine monoacetate 23. The NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetyl-L, L-penicillamine mimicked preconditioning. This protection was also antagonized by 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolol-[4,3-a]quinoxaline-1-one 23.

Genetic models have demonstrated a role for endothelial nitric oxide synthase and NO during early IPC. Myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury was attenuated in mice with myocyte-specific overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase 24. In addition, infarct size was reduced in transgenic mice overexpressing either bovine or human endothelial nitric oxide synthase 25. These data are supported by findings indicating marked increases in infarct size in endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice 26. Additional intriguing results implicating an important role for endothelial nitric oxide synthase in cardioprotection were reported by Bell and Yellon 27 who demonstrated that endothelial nitric oxide synthase-derived NO reduced the threshold of preconditioning in endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice. Four cycles of brief ischemia and reperfusion were required to produce IPC and decrease infarct size, but a less intense preconditioning stimulus failed to protect the heart against infarction in this genetic deletion model 27. Thus, the contribution of NO to cardioprotection may be especially critical when the intensity of the IPC stimulus borders upon the threshold.

Investigations from our laboratory have demonstrated that experimentally-induced diabetes and exogenous hyperglycemia block reductions in infarct size after prolonged coronary occlusion and reperfusion in response to ischemia 5,6, volatile anesthetics 7,8, and the selective mitochondrial KATP channel agonist diazoxide 9. The present results confirm and extend these previous findings and demonstrate that a moderate degree of hyperglycemia abolishes myocardial protection produced by IPC. The results further indicate that the ability of IPC to reduce infarct size is restored by short-term administration of simvastatin during hyperglycemia. In addition, the current data indicate that these beneficial effects of simvastatin are dependent on nitric oxide synthase activity.

Statins exert beneficial effects independent of blood cholesterol-lowering action 4,28 in part by increasing NO bioavailability. Simvastatin upregulated endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression by post-transcriptional stabilization of endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA in human endothelial cells in the presence of oxidized low-density lipoprotein 29. A 29% increase in endothelial nitric oxide synthase protein was observed in coronary microvessels harvested from dogs chemically treated (2 wk) with oral simvastatin concomitant with enhanced basal and stimulated nitrate and nitrite production 30. Simvastatin also increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by stimulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation through activation of the prosurvival enzyme Akt (protein kinase) 31. In contrast to endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation by simvastatin, hyperglycemia appears to inhibit endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by enhancing N-acetylglucosamine modification and decreasing phosphorylation of the Akt phosphorylation site (ser1177) 32.

Statins have previously been shown to produce cardioprotective effects in vivo 13,33 and in vitro 34–36 Simvastatin improved recovery of contractile function and decreased polymorphonucleocyte accumulation in isolated rat hearts 35. Similar results were observed in intact mice 33 when statins were administered 18 h before ischemia and reperfusion. Perfusion of rat hearts with simvastatin before global ischemia and reperfusion also enhanced left ventricular function, increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase protein, endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA, and coronary effluent nitrite concentration, and reduced inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and ultrastructural mitochondrial injury 36. Moreover, chronic administration (5 days) of simvastatin markedly decreased infarct size and reduced neutrophil accumulation in a murine model of type 2 diabetes. These salutary actions occurred in the absence of change in serum cholesterol levels 13.

The present results extend these previous findings and demonstrate for the first time that simvastatin restores IPC-induced cardioprotection during moderate hyperglycemia. This protective effect of simvastatin occurred at a dose that alone did not alter infarct size and was dependent on NO. Thus, this beneficial action of simvastatin during hyperglycemia may be attributed to enhancement of NO signaling elicited by IPC and not to a non-specific effect. L-NAME also blocked the protection afforded by simvastatin during hyperglycemia, but nitric oxide synthase inhibition alone does not impair IPC during normoglycemia. These latter findings concur with the observations of Bell and Yellon 27 suggesting that endothelial nitric oxide synthase-derived NO may not be required for IPC if the ischemic stimulus is sufficiently robust. Our findings additionally suggest that NO may be recruited to play a more important role in IPC when endogenous signaling mechanisms are impaired by hyperglycemia. Our previous data have implicated such a relation between other signaling elements responsible for IPC and the severity of hyperglycemia. For example, the dose of the mitochondrial KATP channel agonist diazoxide required to produce pharmacological preconditioning against infarction was dependent on blood glucose concentrations in dogs 9. A higher dose of diazoxide was required to elicit protection during severe (600 mg/dl) as compared to moderate (300 mg/dl) hyperglycemia. Notably, NO modulates ion channel activity and enhances the activity of KATP channels 37. Taken together, these data suggest the hypothesis that NO may be recruited by statins to counteract a decrease in myocardial KATP channel activity during hyperglycemia. Additional investigation will be required to examine this hypothesis. A recent meta analysis demonstrated that statins markedly reduce the risk of perioperative death in patients undergoing cardiac, non-cardiac and vascular surgery 38. The relationship between perioperative risk reduction by statins and diabetes was not evaluated, however, and represents an important goal of future research.

The current results should be interpreted within the constraints of several potential limitations. Statins reduce plasma low-density lipoprotein concentrations, decrease production of reactive oxygen species, and diminish recruitment of inflammatory cells 4,28,39,40. We did not specifically measure low-density lipoprotein or total cholesterol in healthy dogs. However, a previous study indicated that blood cholesterol levels were unchanged after 5 days of simvastatin treatment in diabetic mice 13. Simvastatin, at a 4-fold higher dose, induced approximately a 15% reduction in cholesterol in dogs treated with this drug for 15 days 41. Thus, it appears unlikely that differences in blood lipid concentrations among groups accounts for the protective effect of simvastatin during hyperglycemia. Blood glucose concentrations were modestly reduced by simvastatin, and a direct relationship between infarct size and blood glucose concentration has been previously demonstrated 6,9. However, simvastatin alone did not affect infarct size as compared to control experiments, and blood glucose concentrations were not reduced by simvastatin after transient hyperglycemia. Thus, simvastatin-induced decreases in blood glucose concentration most likely fail to account for cardioprotection. The dose of simvastatin used in this investigation was based on a comparable dose in humans and on previous reports in the literature 33,35. We did not examine a dose-response relationship to simvastatin nor did we specifically evaluate the influence of chronic versus acute administration of simvastatin on myocardial injury in the presence or absence of hyperglycemia. Hyperglycemia and L-NAME alone produced brief hemodynamic effects that may have theoretically contributed to alterations in infarct size. However, no differences in systemic hemodynamics were observed between groups during coronary artery occlusion or reperfusion, and it is therefore unlikely that hemodynamics alone contributed substantially to the results. The area of the left ventricle at risk for infarction and coronary collateral blood flow are important determinants of the extent of myocardial infarction in dogs, but no differences in these variables were observed among groups that may account for the current findings.

In summary, the current results confirm that hyperglycemia abolishes reductions of myocardial infarct size in response to IPC. The findings further indicate that this deleterious response is abolished by simvastatin in an NO-dependent fashion. The current results also suggest that NO may not be required to elicit IPC in healthy dogs, but NO may instead be recruited by statins to enhance cardioprotection. The current findings lend further support to the hypothesis that statins reduce cardiovascular risk through mechanisms that are independent of reductions in blood cholesterol.

Summary Statement.

Hyperglycemia blocks the cardioprotective effects of ischemic preconditioning against myocardial infarction, but pretreatment with a statin restored protection during hyperglycemia. Statins are known to enhance nitric oxide and a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor abolished statin-induced protection.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants HL 063705 (to Dr. Kersten), GM 066730 (to Dr. Warltier), and HL 054820 (to Dr. Warltier) from the United States Public Health Service, Bethesda, Maryland.

The authors thank David Schwabe B.S.E.E., Department of Anesthesiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, for technical assistance and Nancy Just A.A., Department of Anesthesiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, for assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pyorala K, Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Faergeman O, Olsson AG, Thorgeirsson G. Cholesterol lowering with simvastatin improves prognosis of diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. A subgroup analysis of the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Diabetes Care. 1997;20:614–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefer AM, Scalia R, Lefer DJ. Vascular effects of HMG CoA-reductase inhibitors (statins) unrelated to cholesterol lowering: new concepts for cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:281–7. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kersten JR, Schmeling TJ, Orth KG, Pagel PS, Warltier DC. Acute hyperglycemia abolishes ischemic preconditioning in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H721–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kersten JR, Toller WG, Gross ER, Pagel PS, Warltier DC. Diabetes abolishes ischemic preconditioning: role of glucose, insulin, and osmolality. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1218–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kehl F, Krolikowski JG, Mraovic B, Pagel PS, Warltier DC, Kersten JR. Hyperglycemia prevents isoflurane-induced preconditioning against myocardial infarction. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:183–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200201000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka K, Kehl F, Gu W, Krolikowski JG, Pagel PS, Warltier DC, Kersten JR. Isoflurane-induced preconditioning is attenuated by diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2018–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01130.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kersten JR, Montgomery MW, Ghassemi T, Gross ER, Toller WG, Pagel PS, Warltier DC. Diabetes and hyperglycemia impair activation of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1744–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Medical Association; American Physiological Society. Guiding principles for research involving animals and human beings. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R281–3. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00279.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Commission of Life Sciences, National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals/Institute of Laboratory Animals Resources. 7. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kersten JR, Schmeling TJ, Hettrick DA, Pagel PS, Gross GJ, Warltier DC. Mechanism of myocardial protection by isoflurane. Role of adenosine triphosphate-regulated potassium (KATP) channels. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:794–807. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199610000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lefer DJ, Scalia R, Jones SP, Sharp BR, Hoffmeyer MR, Farvid AR, Gibson MF, Lefer AM. HMG-CoA reductase inhibition protects the diabetic myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Faseb J. 2001;15:1454–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0819fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamagawa K, Saito T, Oikawa Y, Maehara K, Yaoita H, Maruyama Y. Alterations of alpha-adrenergic modulations of coronary microvascular tone in dogs with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005;11:388–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross GJ, Auchampach JA. Role of ATP dependent potassium channels in myocardial ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1992;26:1011–6. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.11.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warltier DC, Zyvoloski MG, Gross GJ, Hardman HF, Brooks HL. Determination of experimental myocardial infarct size. J Pharmacol Methods. 1981;6:199–210. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(81)90109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domenech RJ, Hoffman JI, Noble MI, Saunders KB, Henson JR, Subijanto S. Total and regional coronary blood flow measured by radioactive microspheres in conscious and anesthetized dogs. Circ Res. 1969;25:581–96. doi: 10.1161/01.res.25.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ceriello A, Motz E. Is oxidative stress the pathogenic mechanism underlying insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease? The common soil hypothesis revisited. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:816–23. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000122852.22604.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–36. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross GJ, Peart JN. KATP channels and myocardial preconditioning: an update. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H921–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00421.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muscari C, Bonafe F, Gamberini C, Giordano E, Tantini B, Fattori M, Guarnieri C, Caldarera CM. Early preconditioning prevents the loss of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and enhances its activity in the ischemic/reperfused rat heart. Life Sci. 2004;74:1127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lochner A, Marais E, Genade S, Moolman JA. Nitric oxide: a trigger for classic preconditioning? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2752–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rakhit RD, Edwards RJ, Mockridge JW, Baydoun AR, Wyatt AW, Mann GE, Marber MS. Nitric oxide-induced cardioprotection in cultured rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1211–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunner F, Maier R, Andrew P, Wolkart G, Zechner R, Mayer B. Attenuation of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice with myocyte-specific overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00649-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones SP, Greer JJ, Kakkar AK, Ware PD, Turnage RH, Hicks M, van Haperen R, de Crom R, Kawashima S, Yokoyama M, Lefer DJ. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase overexpression attenuates myocardial reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H276–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00129.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones SP, Girod WG, Palazzo AJ, Granger DN, Grisham MB, Jourd’Heuil D, Huang PL, Lefer DJ. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury is exacerbated in absence of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H1567–73. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell RM, Yellon DM. The contribution of endothelial nitric oxide synthase to early ischaemic preconditioning: the lowering of the preconditioning threshold. An investigation in eNOS knockout mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;52:274–80. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller SJ. Emerging mechanisms for secondary cardioprotective effects of statins. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;52:5–7. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laufs U, La Fata V, Plutzky J, Liao JK. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors. Circulation. 1998;97:1129–35. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.12.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mital S, Zhang X, Zhao G, Bernstein RD, Smith CJ, Fulton DL, Sessa WC, Liao JK, Hintze TH. Simvastatin upregulates coronary vascular endothelial nitric oxide production in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2649–57. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kureishi Y, Luo Z, Shiojima I, Bialik A, Fulton D, Lefer DJ, Sessa WC, Walsh K. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin activates the protein kinase Akt and promotes angiogenesis in normocholesterolemic animals. Nat Med. 2000;6:1004–10. doi: 10.1038/79510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du XL, Edelstein D, Dimmeler S, Ju Q, Sui C, Brownlee M. Hyperglycemia inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by posttranslational modification at the Akt site. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1341–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI11235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones SP, Trocha SD, Lefer DJ. Pretreatment with simvastatin attenuates myocardial dysfunction after ischemia and chronic reperfusion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:2059–64. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.099509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell RM, Yellon DM. Atorvastatin, administered at the onset of reperfusion, and independent of lipid lowering, protects the myocardium by up-regulating a pro-survival pathway. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:508–15. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02816-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lefer AM, Campbell B, Shin YK, Scalia R, Hayward R, Lefer DJ. Simvastatin preserves the ischemic-reperfused myocardium in normocholesterolemic rat hearts. Circulation. 1999;100:178–84. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Napoli P, Antonio Taccardi A, Grilli A, Spina R, Felaco M, Barsotti A, De Caterina R. Simvastatin reduces reperfusion injury by modulating nitric oxide synthase expression: an ex vivo study in isolated working rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;51:283–93. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shinbo A, Iijima T. Potentiation by nitric oxide of the ATP-sensitive K+ current induced by K+ channel openers in guinea-pig ventricular cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1568–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hindler K, Shaw AD, Samuels J, Fulton S, Collard CD, Riedel B. Improved postoperative outcomes associated with preoperative statin therapy. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1260–72. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00027. quiz 1289–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cominacini L, Rigoni A, Pasini AF, Garbin U, Davoli A, Campagnola M, Pastorino AM, Lo Cascio V, Sawamura T. The binding of oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) to ox-LDL receptor-1 reduces the intracellular concentration of nitric oxide in endothelial cells through an increased production of superoxide. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13750–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao L, Harris NR, Granger DN. Oxidized low-density lipoproteins and microvascular responses to ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1996;271:H2508–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doebber TW, Kelly LJ, Zhou G, Meurer R, Biswas C, Li Y, Wu MS, Ippolito MC, Chao YS, Wang PR, Wright SD, Moller DE, Berger JP. MK-0767, a novel dual PPARalpha/gamma agonist, displays robust antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic activities. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:323–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]