Abstract

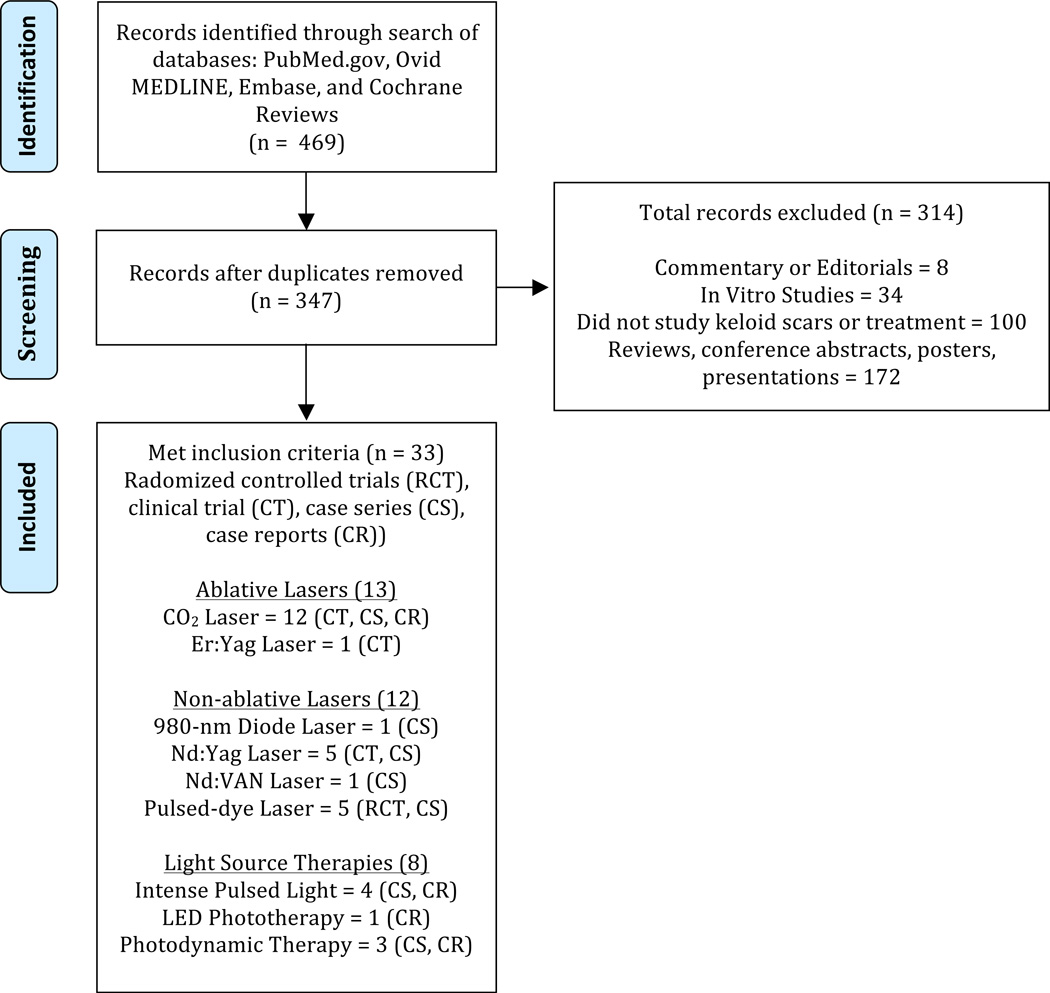

Keloids are an overgrowth of fibrotic tissue outside the original boundaries of an injury and occur secondary to defective wound healing. Keloids often have a functional, aesthetic, or psychosocial impact on patients as highlighted by quality-of-life studies. Our goal is to provide clinicians and scientists an overview of the data available on laser and light-based therapies for treatment of keloids, and highlight emerging light-based therapeutic technologies and the evidence available to support their use. We employed the following search strategy to identify the clinical evidence reported in the biomedical literature: in November 2012, we searched PubMed.gov, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Reviews (1980-present) for published randomized clinical trials, clinical studies, case series, and case reports related to the treatment of keloids. The search terms we utilized were ‘keloid(s)’ AND ‘laser’ OR ‘light-emitting diode’ OR ‘photodynamic therapy’ OR ‘intense pulsed light’ OR ‘low level light’ OR ‘phototherapy.’ Our search yielded 347 unique articles. Of these, 33 articles met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. We qualitatively conclude that laser and light-based treatment modalities may achieve favorable patient outcomes. Clinical studies using CO2 laser are more prevalent in current literature and a combination regimen may be an adequate ablative approach. Adding light-based treatments, such as LED phototherapy or photodynamic therapy, to laser treatment regimens may enhance patient outcomes. Lasers and other light-based technology have introduced new ways to manage keloids that may result in improved aesthetic and symptomatic outcomes and decreased keloid recurrence.

INTRODUCTION

Keloids are an overgrowth of fibrotic tissue outside the original boundaries of an injury and occur secondary to defective wound healing.1 Keloids vary in size, density, demarcation, and site. The exact pathogenesis of keloids is not elucidated and the lack of adequate animal models hinders keloid research.

Keloids often have a functional, aesthetic, or psychosocial impact on patients as highlighted by quality-of-life studies.2 Individuals of African, Hispanic, or Asian descent appear at increased risk for the development of keloids.3 It is estimated that 4.5–16.0% of people of African or Hispanic descent suffer from keloids or hypertrophic scars.3 In addition, keloid prevalence ranging from 0.3–0.6% has been reported in Taiwanese children.4,5

Treatments for keloids include surgical excision, intralesional or topical corticosteroids, other intralesional therapies: 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), bleomycin, and interferon, topical imiquimod, compression, cryotherapy, radiation, silicon sheeting, and laser or light-based therapies. Recurrence is common, even with combination therapy.1 Lasers and other light-based technology have introduced new ways to manage keloids that may result in improved aesthetic and symptomatic outcomes and decreased keloid recurrence. Laser and light-based therapies for keloids can be grouped into three categories: ablative lasers, non-ablative lasers, and non-coherent light sources.

Ablative lasers, such as the 2,940-nm erbium-doped: yttrium, aluminum, and garnet (Er:YAG) laser and the 10,600-nm carbon dioxide (CO2) laser, emit beams absorbed by water in skin resulting in local tissue destruction.6,7

Non-ablative lasers target hemoglobin or melanin. 585 or 595-nm pulsed-dye lasers (PDL) are non-ablative and the major chromophore is oxyhemoglobin.8 PDL also targets melanin, therefore, care must be taken to avoid pigmentary alterations.8 PDL is hypothesized to treat keloids by selective damage of blood vessels that supply the scar.9 The 980-nm diode laser targets hemoglobin and melanin.10 The 1064-nm neodymium-doped:yttrium, aluminum and garnet (Nd:YAG) laser and the 532-nm neodymium-doped:vanadate (Nd:Van) laser are hypothesized to primarily treat keloids by damaging deep dermal blood vessels.11 Nd:YAG may directly suppress fibroblast collagen expression.11,12 Therefore, it is plausible that non-ablative lasers may interact directly with and affect the biological function of keloidal fibroblasts.

Non-laser light sources are also used to treat keloids. These techniques include intense pulsed light therapy (IPL), light-emitting diode (LED) phototherapy, also known as low-level light therapy, and photodynamic therapy (PDT). These modalities utilize light energy that may cause keloid fibroblast functional modification.13–16 IPL emits non-coherent, broadband wavelength, pulsed light and targets pigmentation and vasculature.14 LED phototherapy is hypothesized to photomodulate mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase altering intracellular signaling.15 PDT requires application of a photosensitizer, commonly 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or methyl aminolevulinic acid (MAL), that is preferentially absorbed by highly vascularized or metabolically active tissue and converted to protoporphyrin IX (PpIX).16 Upon exposure to light, PpIX causes the generation of reactive oxygen species free radicals that have a cytotoxic effect.16 PDT may also cause alterations in extracellular matrix synthesis and degradation, and modulate cytokine and growth factor expression.13

Our goal is to provide clinicians and scientists an overview of the current data available on laser and light-based therapies for treatment of keloids in humans, and highlight emerging light-based therapeutic technologies and the basic science evidence available to support their use.

METHODS

Search Strategy

We employed the following search strategy to identify the clinical evidence reported in the biomedical literature: in November 2012, we searched PubMed.gov, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane Reviews (1980-present) for published randomized clinical trials (RCT), clinical studies, case series, and case reports related to the treatment of keloids. The search terms we utilized were ‘keloid(s)’ AND ‘laser’ OR ‘light-emitting diode’ OR ‘photodynamic therapy’ OR ‘intense pulsed light’ OR ‘low level light’ OR ‘phototherapy.’

Selection Procedure and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Published manuscripts, case series, case reports, and letters reporting on keloid treatment using ablative lasers, non-ablative lasers, photodynamic therapy, or light-based modalities from January 1980 to November 2012 were included. Only human studies and English language articles were included. Articles about other skin conditions or scar types, including those that focused on hypertrophic scars without addressing keloids, were excluded. Reviews, abstracts, posters, oral presentations, editorials, and studies that did not specifically evaluate or comment on the efficacy of the treatment modality were excluded.

RESULTS

Our search yielded 347 unique articles. Of these, 33 articles met our inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). We found 13 articles on ablative lasers: CO2 (12), Er:YAG (1). We found 12 articles on non-ablative lasers: 908-nm diode (1), Nd:YAG (5), Nd:Van (1), pulsed-dye laser (5). We found 8 articles on light source therapies: IPL (4), LED (1), PDT (3). Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 33 studies.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the search strategy listing the number of articles matching inclusion or exclusion criteria. Adapted from Moher et al.48

Table 2.

Summary of Laser and Light-based Treatment of Keloid Studies

| Study | Study Type | Outcome Measures | Intervention Methods / Parameters | Follow- up Period (months) |

Efficacy/Conclusion | Recurrence Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ablative Lasers – (13 articles) | ||||||

| Carbon Dioxide Laser (CO2) – (12 articles) | ||||||

| Apfelberg et al.22 | Case Series | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | 7–23 W. 0.2-mm to 1.0-mm spot size. Settings varied depending on patient’s individual keloid characteristics. | 10 to 22 | There were no long-term benefits of CO2 laser excision of keloids. | 88.8% (8/9) |

| Apfelberg et al.21 | Case Series | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | 10 W, 500 W/cm2 power density. 1-mm spot size. Some patients were previously treated with argon laser. | 6 | No improvement with CO2. | 100% (3/3) |

| Garg et al.28 | Clinical trial, non-blinded, no control. | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | Super pulse or continuous setting; 15 W power. 40 mg/ml triamcinolone acetonide injections immediately following laser surgery and again every 3 – 4 weeks for 6 months. | 6 | CO2 ablation, followed by monthly intralesional steroid for 6 months, is a satisfactory approach for keloid management. | 15.4% (2/13) if received regular intralesional steroids |

| Henderson et al.52 | Case Series | Clinical assessment of improvement. | Mixed case series of argon and CO2 cases. CO2 settings: 20 W Power, 500 W/cm2 power density. 2.0-mm spot size. Treated at 6- to 8-week intervals until improved. | 3 to 48 | 54.5% (48/82) rated as good or excellent improvement. | N/A |

| Kantor et al.53 | Case Series | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | 200–250 watts/cm2. Triamcinolone acetonide intralesional injections following surgery. | 2 to 40 | 25% (4/16) of patients showed hypertrophic scarring at follow-up without recurrence. | 75% (12/16) |

| Morosolli et al.24 | Case Report | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | Continuous setting; 7 W power; 2.5 W/cm2 power density; 0.8-mm spot. | 6 | No recurrence at follow-up | No recurrence |

| Nicoletti et al.26 | Case Series | Clinical assessment of improvement. | Super pulse mode at 5–8 Hz and 200–250 µs duration or 30 Hz and 300 µs duration. 3-mm spot size. | 12 | Clinical assessment and patient survey noted improvement in all keloids treated. | No recurrence |

| Norris et al.27 | Case Series | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | Continuous Mode. 8–14 W. 0.2-mm to 0.3-mm spot size. | Not Stated | 39.1% (9/23) responded to treatment with addition of intralesional steroids. | 56.5% (13/23) |

| Scrimali et al.54 | Case Series | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | 12 monthly treatments following surgical excision or intralesional steroids. 13 W of power, 8 SX of index and 40% coverage. (Generally, first treated with corticosteroid injection or surgical excision prior to CO2) | 12 | All patients had optimal results at follow-up and no hyper or hypopigmentation. | No recurrence |

| Scrimali et al.55 | Case Series | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | 6 monthly treatments following surgical excision. 13 W of power, 8 SX of index and 40% coverage. | 12 | All patients had optimal results at follow-up and no hyper or hypopigmentation. | No recurrence |

| Stern et al.56 | Retrospective | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | Continuous or 0.2-second pulse mode. Average intensity of 12 W. | 24 | Failed to demonstrate a lower recurrence rate | 73.9% (17/23) |

| Tenna et al.25 | Case Report | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | Settings not stated. 3-days following treatment. Utilized N-butyl cyanoacrylate glue post op. | 10 | Good results were obtained. All patients were satisfied with treatment. | N/A |

| Erbium-doped: Yttrium, Aluminum, and Garnet (Er:YAG) – (1 articles) | ||||||

| Wagner et al.9 | Clinical trial, non-blinded, no control. | Clinician assessment of improvement using Vancouver Scar Scale. | 3.0–4.0 J/cm2 thermal energy density. Spot size of 5-mm. Additional ablative energy at 1.0–3.0 J/cm2 depending on the thickness of the scar. | 12 | Reduction in redness, scar elevation, and hardness after treatment. | N/A |

| Non-ablative Lasers – (12 articles) | ||||||

| Diode Laser (980-nm) – (1 articles) | ||||||

| Kassab et al.12 | Case Series | Clinical assessment of improvement. | The laser pulses were delivered interstitially. Single repeated mode of 4 s duration; 5 W power; 20 J/cm2 energy density; 5–9 pulses were applied depending on keloid size and pigmentation. Following the laser session, 1 ml of 40 mg/ml triamcinolone acetonide. | 12 | After 12-month follow-up, 12/16 (25.0%) of patients showed 75.0% or greater reduction in original scar size. | N/A |

| Neodymium-doped: Yttrium, Aluminum and Garnet Laser (Nd:YAG) – (5 articles) | ||||||

| Abergel et al.33 | Case Series | Clinical assessment of improvement. | 70 W, 60 J/cm2 power density, 1 cm2 spot area. 1–2 week intervals between treatments. | 36 | Flattening and softening of lesions at follow-up. | N/A |

| Akaishi et al.36 | Clinical trial, non-blinded, no control. | Clinician assessment. | Hand-piece held 2–3 cm above the skin surface. 5-mm spot size; 14 J/cm2 energy density; 300 µs (0.3 ms) exposure time per pulse; repetition rate of 10 Hz (500 to 1000 pulses/cm2). Treated every 3–4 weeks with an average of 14.05 exposures per patient (range 5–49). | 6 to 10 | 36.4% (8/22) of patients demonstrated a clear reduction in the size of their lesions (less than 90% of the original area). | N/A |

| Apfelberg et al.35 | Case Series | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | Prior or following ND:Yag treatment, keloids were injected intralesionally with 1–3 mL of betamethasone. Topical 0.25% betamethasone following treatment. | 12 | 22.7% (5/22) showed persistent flattening of keloids or hypertrophic scars. | 63.6% (14/22) |

| Cho et al.37 | Case Series | Clinical assessment. Patient satisfaction survey. | 1.8–2.2 J/cm2, 7-mm spot size and 5–6 passes. 5–10 treatment sessions per patient. | 3 | Mean score for vascularity, pliability, and height showed improvement. | N/A |

| Sherman et al.34 | Case Series | Clinical assessment of improvement. | 20–70 W. 0.2–0.5 second bursts. | 3 to 6 | Flattening and softening of keloid. | N/A |

| Neodymium-doped: vanadate laser (Nd:Van) – (1 article) | ||||||

| Cassuto et al.38 | Case Series | Recurrence (clinical assessment). | 532-nm diode-pumped Nd:VAN laser; 6–7 J/ cm2 energy density; 2–3 ms pulse duration; 10 × 10-mm spot size. Treated every 4 weeks with an average of 8.5 treatments per patient. | 12 | All patients completed their treatment course and were followed-up for 1 year after the last treatment without any recurrence. | No recurrence |

| Pulsed-dye Laser (PDL) – (5 articles) | ||||||

| Alster et al.30 | Clinical trial, blinded, split scar control. | Clinical assessment of improvement. Impressions to measure topography. | Treated at 450 µs pulse duration; 5-mm spot size; 6.5–7.5 J/cm2 energy density. | 6 | All patients had improvement in clinical appearance. Significant improvement in erythema, scar height, and pliability. | N/A |

| Asilian et al.32 | Randomized clinical trial, single-blinded, split scar control. | Caliper measurement, erythema, and pliability. Patient self-assessment. | 5.0–7.5 J/cm2 energy density; 5-mm spot size; pulse duration 250 msec. Adjuvant treated with triamcinolone acetonide (TAC) and/or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). | 3 | TAC + 5-FU + PDL group had greatest improvement with 70.0–75.0% of patients had >50.0% improvement. | N/A |

| Connell et al.57 | Case Series | Clinical assessment. | 5 J/cm2 energy density; 5-mm spot size. 6 treatment sessions at 4-week intervals. 1–3 treatments at 6–8 week intervals. Followed by injection with 40 mg/ml methylprednisolone acetate. 6-week treatment intervals. | 12 | Mean improvement in scar elevation of 57.5% | N/A |

| Manuskiatti et al.31 | Randomized Clinical trial, split scar control. | Caliper measurement, colorimeter measurement, and pliability. Patient self-assessment. | Scars were irradiated with a 585 nm PDL. 5 J/cm2 energy density; 7-mm spot size. 6 treatment sessions at 4-week intervals. Combination and comparison groups were treated with triamcinolone acetonide and/or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). | 8 | Significant improvement was seen in all groups. Author suggests that treatment and combination therapy needs to be individualized based on patient goals. | N/A |

| Paquet et al.58 | Case Series | Clinical Assessment and spectroscopy of keloid erythema (redness). | 6–6.5 J/cm2 energy density; 7-mm spot size. 6 treatment sessions at 4-week intervals. 1–3 treatments at 6–8 week intervals. | Not Stated | Minimal effects on erythema of keloids. | N/A |

| Light source therapies – (8 articles) | ||||||

| Intense Pulsed Light (IPL) – (4 articles) | ||||||

| Erol et al.45 | Case series | Clinical assessment. Patient satisfaction. | No standardized treatment protocol. Cutoff filters of 550–590 nm; 30–40 J/cm2 energy density; 2.1–10 ms pulse duration; 10–40 ms pulse delays. Each patient received IPL therapy every 2–4 weeks with a minimum of six sessions. | Not Stated | Excellent improvement in 31.2% (34/109), good 25.7% (28/109), moderate 33.9% (37/109), and minimal in 9.1% (10/109). 76.7% (66/86) reported good treatment satisfaction. | N/A |

| Kontoes et al.16 | Case Series | Patient reporting was the primary measure of improvement. | No standardized treatment protocol. Utilized cutoff filters: 515, 550, 570, 590, 615, 645 nm; 22–50 J/cm2 energy density; 2.1–10 ms pulse duration; 10–40 ms pulse delay. In 56% of cases (19/34) IPL was combined with another treatment modality. | Not Stated | Of 24 patients with keloids, 83.3% (20/24) reported more than 50.0% reduction in the size and volume of the treated scar | N/A |

| Levenberg et al.43 | Case Report | Clinical assessment of length and width of keloid. | 5–10 J/cm2 energy density; 6 pulses with 10 ms pulse width at 30-second intervals; 8 weekly treatments. | 4 | 30% reduction in length and 60% decrease in width. | N/A |

| Perosino et al.44 | Case Report | Clinical assessment after treatment. | Cutoff filters 550–590 nm; 30–50 J/cm2 energy density; 3–5 ms pulse duration; 20–40 ms pulse delays. 5 treatments every 4–8 weeks. | Not Stated | Improvement of 80% considering size, margins, color, texture, contour, and bulk. | N/A |

| Light-Emitting Diode (LED) Phototherapy – (1 article) | ||||||

| Barolet et al.40 | Case Report | Quantitative measurements via in vivo 3D microtopography. Clinical assessment. | Daily 15 minute home treatment with non-thermal, non-ablative NIR LED 805 nm; 30 mW/cm2 power density; 2.5 cm treatment distance. Treated for 30 days following surgical revision or CO2 laser resurfacing of keloid scar. | 12 | Clinical improvements were deemed moderate to excellent with a significant regulation in scar height. | N/A |

| Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) – (3 articles) | ||||||

| Nie et al.46 | Case Report | Clinical assessment of size and erythema. | Topical MAL applied to keloid for 3 hours; irradiated with 633 nm LED. 5 sessions over 5 months. | 12 | Overall reduction in volume. | No recurrence |

| Tosa et al.49 | Case Series | Clinical assessment. | Topical ALA applied to keloid for 3 hours; irradiated with 633 nm LED. 5 sessions over 5 months. | Not Stated | 50.0% of patients showed complete; 10.0% of patients show > 50.0% improvement, 40.0% of patients showed <50.0% improvement. | N/A |

| Ud-Din et al.47 | Case Series | Recurrence (clinical assessment). Pain and pruritus scores. | Topical MAL applied to keloid for 3 hours; irradiated with 630 nm LED. Each patient received 3 treatments at weekly intervals. | 9 | Pain, pruritus, hemoglobin, and collagen levels were all decreased. Pliability increase. | 5.0% (1/20) |

DISCUSSION

Many of the articles were methodologically limited (no control-arm, non-blinded, non-randomized). The lack of double-blind RCTs is demonstrated in the following discussion and Table 1. The challenge of conducting double-blind RCTs for keloid laser treatment is the inherent difficulty in blinding patients and laser operators.

In the studies reviewed, keloid outcomes after treatment were sometimes measured using scar-rating systems, such as the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), or a modified version thereof. The VSS grades vascularity, thickness, pliability, and pigmentation.17 However, non-universal usage of this assessment scale limits the usefulness in comparing study outcomes. Other scar scales exist, but were not utilized in the studies we reviewed.17

Ablative laser treatment results in keloid tissue destruction and therefore recurrence rate is an appropriate outcome measure. Non-ablative lasers and light-based therapies alter keloid milieu and result in reduction in size, erythema, pliability, and symptomatology making clinical assessment of these parameters a more appropriate measure. In studies utilizing the same laser class, we found that differences in efficacy and/or recurrence were sometimes reported. These different outcome conclusions are likely due to variations in lasers, settings, and treatment protocols.

Ablative Lasers

Carbon Dioxide Laser

We identified 12 manuscripts on CO2 laser ablation of keloids. Three published case series showed little benefit to CO2 laser ablation monotherapy with recurrence rates of 88.8% (8/9), 92.3% (12/13), and 73.9% (17/23) within 2 years.18–20 One case reported CO2 ablation monotherapy effectively treating a keloid, however, recurrence was only assessed for 6 months.21

Another article described 7 keloids excised by CO2 laser followed by treatment every 5 days for 3 months with n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue that creates an occlusive pressure-dressing over the surgical site and is hypothesized to inhibit keloid regrowth.22 The investigators reported 100% patient satisfaction with treatment outcomes at a 1-year follow-up.22 Another case series of 50 patients treated with CO2 laser monotherapy followed by silicone-gel sheeting over the lesion resulted in long-term clinical and histological improvement at 12-month follow-up in all patients treated.23 Recurrence rates were not published for either study.

Several studies investigating CO2 ablation utilized adjuvant pharmacotherapy such as intralesional steroid injections. One case series reported 95.7% (22/23) of patients treated by CO2 monotherapy had recurrence, however, the length of the follow-up period was not reported.24 All 22 patients who had recurrence were treated with intralesional steroid injections and 40.9% (9/22) demonstrated no recurrence following combination CO2 and intralesional steroid injection therapy.24 In another study evaluating the effects of CO2 laser treatment followed by steroid injections, 35 Keloids from 28 patients were ablated using a CO2 laser and injected intralesionally with triamcinolone acetonide (TAC) 40 mg/ml at 0.050 ml/cm2 immediately following laser surgery and then again every 3 to 4 weeks for 6 months.25 Outcomes were evaluated at 6 months after the last intralesional steroid injection and of the 13 patients that completed the eight steroid injections protocol, 15.4% (2/13 patients) showed recurrence.25 Of the 10 patients with a total of 12 keloids who did not complete all eight steroid injection treatments, 75.0% (9/12 keloids) showed recurrence after 6 months, and 5 patients were lost to follow-up.25

CO2 laser monotherapy can ablate keloids but is associated with high rates of recurrence may be due to incomplete removal of keloidal fibroblasts. The authors hypothesize that CO2 monotherapy may in fact worsen keloids, however, there is no data in current literature to support this hypothesis. CO2 laser combined with adjuvant therapies, such as steroids or occlusive agents, holds promise for treatment of keloids without recurrence. Steroid injections may cause side effects, including telangiectasias, hypopigmentation, depigmentation, and atrophy.25 Of note, we found in our clinical experience that direct application of topical steroids to keloid scars immediately after fractionated CO2 treatment minimizes side effects associated with intralesional steroid treatment and evenly distributes the steroid to the desired tissues.

Erbium-doped:Yttrium, Aluminum, and Garnet Laser

Only one study evaluated Er:YAG laser ablation of keloids.7 In this non-blinded randomized trial, Er:YAG laser treatment of 21 patients, with or without silicone gel application, resulted in a decrease of 51.3% in redness, 50.0% in elevation, and 48.9% hardness of keloids; recurrence of keloids was not reported.7 Daily application of silicone gel did not improve the effect of Er:YAG laser therapy.7

Non-ablative Lasers

Pulsed-dye Laser

Our search found five articles on PDL treatment for keloids. Alster et al first reported successful treatments of scars with 585-nm PDL.26 By splitting each side of post-sternotomy scars in 16 patients into a treated or untreated group, they demonstrated that PDL monotherapy improved the erythema, height, pliability, and texture of both keloids and hypertrophic scars compared to the non-treated side of the same scar.26,27 Since then, PDL has become a common laser-based treatment option for keloids and other scars.8

Studies have investigated the use of PDL with adjuvants including topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and intralesional steroid injections. A RCT that compared the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic sternotomy scars using intralesional TAC or 5-FU, to PDL found significant flattening of the scars in the PDL group that was similar to the other treatment cohorts.28 In a single-blinded RCT, TAC + 5-FU + PDL combination therapy showed a greater response than TAC + 5-FU or TAC alone (5-FU monotherapy was not investigated).29 The authors found greater than 50.0% improvement in 70.0% of the TAC + 5-FU + PDL cohort indicating that a combination of intralesional therapy plus PDL is more efficacious for treatment of keloids than TAC alone.29

Based upon the strength of the reviewed studies, it is reasonable to conclude that PDL is an appropriate non-ablative option to enhance the cosmetic appearance and provide symptomatic relief for patients with keloid scars.8 Combination intralesional therapy plus PDL may be more effective than PDL monotherapy. PDL has an approximate 1.2 mm depth of penetration and efficacy in thicker keloids may be limited.16 PDL may also resolve scar-associated symptoms such as pruritus.8

Neodymium-doped:Yttrium, Aluminum and Garnet Laser

We identified five articles on Nd:YAG laser to treat keloids. Two case series both reported observing flattening and softening of keloids after Nd:YAG treatment, however, no objective measures were reported.30,31 Another case series reported that only 22.7% (5/22) showed persistent flattening of keloids or hypertrophic scars 12-months after Nd:YAG treatment.32 In a non-blinded clinical trial, 36.4% (8/22) of patients treated with Nd:YAG every 3 to 4 weeks had a reduction in the size of their scar (10% or greater reduction in size).33 Electron microscopy revealed that non-contact mode Nd:YAG does not cause discernible changes to vascular endothelial cells or fibroblasts, but may function by inducing plasma protein leakage or changes in the collagen fiber fascicles.33 In a case series 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG to treat 12 patients with keloids or hypertrophic scars resulted in significant improvement as measured by the VSS score.34

Nd:YAG lasers appear to improve the cosmetic appearance of keloids. Nd:YAG may be a superior non-ablative option compared to PDL to treat thicker keloids, as Nd:YAG penetrates deeper into the skin. Nd:YAG can also be used interstitially, in large keloids, by placing the bare laser fiber inside the keloid.11 This technique may not be useful to many practitioners as bare fiber Nd:YAG has limited commercial availability and the use of interstitial Nd:YAG is a delicate procedure because under-treating can lead to suboptimal results, and over-treating may lead to recurrence or worsening of the keloid.11

Neodymium-doped:Vanadate Laser

We found one study on 532-nm, frequency doubled, Nd:Van treatment of keloids. This case series described effective treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars in 37 patients treated with Nd:Van followed by silicone gel sheeting.35 Patients required an average of 8.5 treatments 4 weeks apart, but 0% (0/37) experienced recurrence at 1-year follow-up.35 These results are promising, however, limited commercial availability of Nd:Van laser hinders further study and clinical treatment of keloids using this modality.

980-nm diode Laser

One study evaluated interstitial 980-nm diode laser for the treatment of keloids.10 This case series reported that 980-nm diode laser and intralesional TAC combination therapy resulted in 75% (9/12) success rate at 12-month follow up (success characterized by the authors as greater than 75% reduction in scar size) and no worsening in 100% (12/12) patients at follow up.10 These results illustrate the need for further investigation of the use of 980-nm diode laser in the treatment of keloids.36

Non-coherent Light Source Therapies

Intense Pulsed Light

We found four papers on IPL treatment of keloids. A case report on IPL delivered eight treatments at weekly intervals resulting in reduction in the keloid length by 30% and width by 60%.37 Another report found five treatments of IPL improved size, margins, color, and texture.38

In a case series evaluating IPL in 24 patients with keloids, 83.3% (20/24) self-reported more than 50.0% reduction in the size and volume of the treated scar.14 This reporting method is susceptible to patient recall bias.14 Another case series evaluated IPL in 109 patients with hypertrophic scars or keloids. Each patient received IPL therapy every 2–4 weeks with a minimum of six sessions.39 Using clinical appearance, coloring, and scar height as measures of clinical improvement, the investigators reported excellent improvement in 31.2% (34/109) of patients, good in 25.7% (28/109), moderate in 33.9% (37/109), and minimal in 9.1% (10/109).39

These results are encouraging and further studies are needed. IPL may cause pigmentary alteration and burns and therefore caution is advised when treating skin types IV to VI.

Light-emitting Diode Phototherapy

We found one case series that evaluated the prophylactic use of LED phototherapy using near-infrared 805-nm light as a method to prevent or attenuate the development of hypertrophic scars or keloids in three patients that underwent surgical excision or CO2 laser ablation of keloids or hypertrophic scars.40 Following initial treatment, one scar from each patient was treated for 15-minutes daily for 30 days with a infrared LED device (805-nm at 30 mW/cm2) and showed significant improvement with no associated side effects as evidenced by improvements in VSS score, measurement of scar height by quantitative skin topography, and blinded clinical assessment of photographs.40 In vitro studies demonstrate that LED phototherapy, at both red and near-infrared wavelengths, can suppress fibroblast proliferation and may provide a mechanistic foundation for future treatment of keloids.41,42 The use of LED phototherapy as an adjunctive therapy may prove to be a safe, cost-effective, and convenient method for at-home care of keloid scars.

Photodynamic Therapy

PDT is an emerging treatment option for keloids. We found a total of three PDT studies; one study on ALA-PDT and two studies on MAL-PDT. A case report described 5 MAL-PDT treatments of a recurrent keloid that resulted in gradual reduction in keloid size and a significant reduction in overall volume.43 In a case series, keloids that received 3 treatments of topical MAL-PDT at weekly intervals showed no recurrence at 9-month follow-up and also showed significant improvement in pruitis, pain, pliability, and collagen and hemoglobin level measured by spectrophotometric intracutaneous analysis.44

A retrospective case series that described scar improvement (keloid vs. hypertrophic scar not defined) in pre- and post-treatment photographs of 6 patients treated for multiple non-melanoma skin cancers, showed an improvement in scarring following two or three treatments of ALA-PDT or MAL-PDT, but no improvement after one session.45 This study did not distinguish between ALA-PDT and MAL-PDT. These results suggest that the use of multiple PDT treatments may be important to achieve scar remodeling. Similar findings were reported in clinical study in which of 50% of patients (n=14)with keloids who were treated with ALA-PDT once monthly for 3 months, showed complete clearance.46

Although data is limited on PDT’s clinical efficacy in keloids, future development of new delivery methods, prodrugs, or combination therapy may make PDT an important technique for the management of keloids. Penetration depth is a limitation that may need to be addressed to effectively treat thick keloids with PDT, as ALA and MAL penetrate approximately 3 mm deep.47 PDT may be better utilized as adjuvant therapy following surgical excision as a prophylactic measure in patients predisposed to keloids; however, this needs to be studied.

Conclusion

We provided a focused review of the available data on laser and light-based therapies for treatment of keloids. Laser and light-based keloid therapy continues to evolve; however, conclusions on efficacy cannot be made due to the paucity of adequate studies. Fundamental keloid parameters such as size, location, and age of the keloid may have significant effect on outcomes and thus are valuable information to collect for future studies. The majority of the studies reviewed did not report these parameters. In addition, an overwhelming majority of identified studies are retrospective reports and therefore more RCT are warranted. Development of a universally accepted classification system to evaluate keloid scars and outcomes post-treatment may improve quality of studies and allow for better comparison across different studies. Qualitatively, it appears that laser and light-based treatment modalities may achieve favorable patient outcomes. In addition, clinical studies using CO2 laser are more prevalent in current literature and a combination regimen may be an adequate ablative approach. PDL plus adjuvant therapy may be an effective non-ablative laser regimen. Adding light-based treatments, such as LED phototherapy or photodynamic therapy, to laser treatment regimens may enhance patient outcomes.

When treating keloids, it is important to tailor therapy to the patient and practitioner. Patient skin type, downtime, and compliance to post-treatment care are key aspects that determine treatment regimen. Practitioner laser comfort level and laser access will define treatment protocols. We envision that translational research will continue to enhance our understanding of keloids and innovation in laser and light-based technology will lead to superior treatment outcomes.

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Bruce Abbott for his excellent technical assistance with conducting our search of the biomedical literature.

Funding Source: The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant number UL1 TR000002 and linked award TL1 TR000133. The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant number UL1 TR000002 and linked award KL2 TR000134. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R33AI080604. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None declared

References

- 1.Bayat A, McGrouther DA, Ferguson MW. Skin scarring. Bmj. 2003;326:88–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7380.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock O, Schmid-Ott G, Malewski P, et al. Quality of life of patients with keloid and hypertrophic scarring. Archives of dermatological research. 2006;297:433–438. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oluwasanmi JO. Keloids in the African. Clinics in plastic surgery. 1974;1:179–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang YC, Cheng YW, Lai CS, et al. Prevalence of childhood acne, ephelides, warts, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia areata and keloid in Kaohsiung County, Taiwan: a community-based clinical survey. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2007;21:643–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen GY, Cheng YW, Wang CY, et al. Prevalence of skin diseases among schoolchildren in Magong, Penghu, Taiwan: a community-based clinical survey. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi. 2008;107:21–29. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alster TS. Cutaneous resurfacing with CO2 and erbium: YAG lasers: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative considerations. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1999;103:619–632. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199902000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner JA, Paasch U, Bodendorf MO, et al. Treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars with the triple-mode Er:YAG laser: A pilot study. Medical Laser Application. 2011;26:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alster TS, Handrick C. Laser treatment of hypertrophic scars, keloids, and striae. Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2000;19:287–292. doi: 10.1053/sder.2000.18369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garden JM, Tan OT, Kerschmann R, et al. Effect of dye laser pulse duration on selective cutaneous vascular injury. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1986;87:653–657. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12456368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassab AN, El Kharbotly A. Management of ear lobule keloids using 980-nm diode laser. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:419–423. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philipp CM, Scharschmidt D, Berlien HP. Laser treatment of scars and keloids – How we do it. Medical Laser Application. 2008;23:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abergel RP, Meeker CA, Lam TS, et al. Control of connective tissue metabolism by lasers: recent developments and future prospects. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1984;11:1142–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nie Z. Is photodynamic therapy a solution for keloid? Giornale Italiano di Dermatologia e Venereologia. 2011;146:463–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kontoes PP, Marayiannis KV, Vlachos SP. The use of intense pulsed light in the treatment of scars. European Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2003;25:374–377. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(03)00218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang YY, Sharma SK, Carroll J, et al. Biphasic dose response in low level light therapy - an update. Dose-response : a publication of International Hormesis Society. 2011;9:602–618. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.11-009.Hamblin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu A, Moy RL, Ross EV, et al. Pulsed dye laser and pulsed dye laser-mediated photodynamic therapy in the treatment of dermatologic disorders. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.] 2012;38:351–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apfelberg DB, Maser MR, Lash H, et al. Preliminary results of argon and carbon dioxide laser treatment of keloid scars. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 1984;4:283–290. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900040309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apfelberg DB, Maser MR, White DN, et al. Failure of carbon dioxide laser excision of keloids. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 1989;9:382–388. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900090411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stern JC, Lucente FE. Carbon dioxide laser excision of earlobe keloids. A prospective study and critical analysis of existing data. Archives of Otolaryngology -- Head & Neck Surgery. 1989;115:1107–1111. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1989.01860330097026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morosolli AR, De Oliveira Moura Cardoso G, Murilo-Santos L, et al. Surgical treatment of earlobe keloid with CO2 laser radiation: case report and clinical standpoints. Journal of cosmetic and laser therapy : official publication of the European Society for Laser Dermatology. 2008;10:226–230. doi: 10.1080/14764170802307957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenna S, Aveta A, Filoni A, et al. A new carbon dioxide laser combined with cyanoacrylate glue to treat earlobe keloids. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2012;129:843e–844e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824a6207. author reply 4e–6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicoletti G, De Francesco F, Mele CM, et al. Clinical and histologic effects from CO(2) laser treatment of keloids. Lasers in medical science. 2012;28:957–964. doi: 10.1007/s10103-012-1178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris JE. The effect of carbon dioxide laser surgery on the recurrence of keloids. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1991;87:44–49. discussion 50-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg GA, Sao PP, Khopkar US. Effect of carbon dioxide laser ablation followed by intralesional steroids on keloids. Journal of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery. 2011;4:2–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.79176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alster TS, Kurban AK, Grove GL, et al. Alteration of argon laser-induced scars by the pulsed dye laser. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 1993;13:368–373. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900130314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of keloid sternotomy scars with 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser. Lancet. 1995;345:1198–1200. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91989-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE. Treatment response of keloidal and hypertrophic sternotomy scars: comparison among intralesional corticosteroid, 5-fluorouracil, and 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser treatments. Archives of dermatology. 2002;138:1149–1155. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.9.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asilian A, Darougheh A, Shariati F. New combination of triamcinolone, 5-Fluorouracil, and pulsed-dye laser for treatment of keloid and hypertrophic scars. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.] 2006;32:907–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abergel RP, Dwyer RM, Meeker CA. Laser treatment of keloids: A clinical trial and an in vitro study with Nd:YAG laser. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 1984;4:291–295. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900040310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherman R, Rosenfeld H. Experience with the Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of keloid scars. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 1988;21:231–235. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apfelberg DB, Smith T, Lash H, et al. Preliminary report on use of the neodymium-YAG laser in plastic surgery. Lasers in Surgery & Medicine. 1987;7:189–198. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900070210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akaishi S, Koike S, Dohi T, et al. Nd:YAG Laser Treatment of Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars. Eplasty. 2012;12:e1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho S, Lee J, Lee S, et al. Efficacy and safety of 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser with low fluence for keloids and hypertrophic scars. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2010;24:1070–1074. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cassuto DA, Scrimali L, Sirago P. Treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloids with an LBO laser (532 nm) and silicone gel sheeting. Journal of cosmetic and laser therapy : official publication of the European Society for Laser Dermatology. 2010;12:32–37. doi: 10.3109/14764170903453846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park TH, Chang CH. Letter regarding "Management of ear lobule keloids using 980-nm diode laser". Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levenberg A. Treatment of a mediastinoscopy-induced keloid with a pulsed light and heat energy device. Cosmetic Dermatology. 2004;17:445–447. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perosino E, Tati E. Case report: Treatment of keloid with Intense Pulsed Light. Journal of Plastic Dermatology. 2010;6:149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erol OO, Gurlek A, Agaoglu G, et al. Treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloids using intense pulsed light (IPL) Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2008;32:902–909. doi: 10.1007/s00266-008-9161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barolet D, Boucher A. Prophylactic low-level light therapy for the treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloids: a case series. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 2010;42:597–601. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lev-Tov H, Brody N, Siegel D, et al. Inhibition of Fibroblast Proliferation In Vitro Using Low-Level Infrared Light-Emitting Diodes. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.] 2012;39:422–425. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lev-Tov H, Siegel D, Brody N, et al. LED generated low level light therapy inhibits human skin fibroblast proliferation while maintaining cellular viability. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2012;132:S119. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nie Z, Bayat A, Behzad F, et al. Positive response of a recurrent keloid scar to topical methyl aminolevulinate-photodynamic therapy. Photodermatology, photoimmunology & photomedicine. 2010;26:330–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2010.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ud-Din S, Thomas G, Morris J, et al. Photodynamic therapy: an innovative approach to the treatment of keloid disease evaluated using subjective and objective non-invasive tools. Archives of dermatological research. 2012;305:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s00403-012-1295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakamoto FH, Izikson L, Tannous Z, et al. Surgical scar remodelling after photodynamic therapy using aminolaevulinic acid or its methylester: a retrospective, blinded study of patients with field cancerization. The British journal of dermatology. 2012;166:413–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tosa M, Murakami M, Iwakiri I, et al. Treatment of keloids with photodynamic therapy using 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA-PDT): a preliminary study. The second Japan scar workshop. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morton CA, McKenna KE, Rhodes LE. Guidelines for topical photodynamic therapy: update. The British journal of dermatology. 2008;159:1245–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open medicine : a peer-reviewed, independent, open-access journal. 2009;3:e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henderson DL, Cromwell TA, Mes LG. Argon and carbon dioxide laser treatment of hypertrophic and keloid scars. Lasers in Surgery & Medicine. 1984;3:271–277. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900030402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kantor GR, Wheeland RG, Bailin PL. Treatment of earlobe keloids with carbon dioxide laser excision: A report of 16 cases. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1985;11:1063–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1985.tb01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scrimali L, Lomeo G, Nolfo C, et al. Treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloids with a fractional CO2 laser: A personal experience. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2010;12:218–221. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2010.514924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scrimali L, Lomeo G, Tamburino S, et al. Laser CO2 versus radiotherapy in treatment of keloid scars. Journal of Cosmetic & Laser Therapy. 2012;14:94–97. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2012.671524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Connell PG, Harland CC. Treatment of keloid scars with pulsed dye laser and intralesional steroid. Journal of Cutaneous Laser Therapy. 2000;2:147–150. doi: 10.1080/14628830050516407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paquet P, Hermanns JF, Pierard GE. Effect of the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser for the treatment of keloids. Dermatologic Surgery. 2001;27:171–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]