Abstract

Purpose

There has been much recent interest in promoting gender equality in academic medicine. This study aims to analyze gender differences in rank, career duration, publication productivity and research funding among radiation oncologists at U.S. academic institutions.

Methods

For 82 domestic academic radiation oncology departments, the authors identified current faculty and recorded their academic rank, degree and gender. The authors recorded bibliographic metrics for physician faculty from a commercially available database (SCOPUS, Elsevier BV, Amsterdam, NL), including numbers of publications and h-indices. The authors then concatenated this data with National Institute of Health funding for each individual per Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (REPORTer). The authors performed descriptive and correlative analyses, stratifying by gender and rank.

Results

Of 1031 faculty, 293 (28%) women and 738 (72%) men, men had a higher median h-index (8 (0-59) versus 5 (0-39); P<.05) and publication number (26 (0-591) versus 13 (0-306); P<.05) overall, and were more likely to be senior faculty and receive NIH funding. However, after stratifying for rank, these differences were largely non-significant. On multivariate analysis, there were significant correlations between gender, career duration and academic position, and h-index (P<.01).

Conclusions

The determinants of a successful career in academic medicine are certainly multi-factorial, particularly in traditionally male-dominated fields. However, data from radiation oncologists show a systematic gender association withfewer women achieving senior faculty rank. However, women who achieve senior status have productivity metrics comparable to their male counterparts. This suggests early career development and mentorship of female faculty may narrow productivity disparities.

Over the last several decades, there has been an increase in the numbers of female medical students, residents and faculty1. Despite the demographic shift seen across many specialties, we have not seen increased representation of women in the field of radiation oncology, with women comprising 32% of all residents in 2011, a percentage that is unchanged compared to 20011. There remain potential overt and covert impositions which might deter optimization of female career opportunities in medical science. Several data regarding gender inequalities in publication rates2, salaries3, funding4,5 and career trajectories6,7 suggest that a gender-neutral, merit-based work environment remains an elusive goal. Further, recent data published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggest female scientists operate in environments where subtle but real biases cause female scientists to be at a systematic disadvantage compared to male counterparts8. This study, which received considerable attention in the mainstream media, showed both men and women were more likely to rate a candidate assigned a male name as more competent, more hirable, and worthy of a higher starting salary than a candidate with an identical resume assigned a female name8. Investigators in several fields of academic medicine have reported on the gender differentials in their specific specialties and have sought to ascertain the rationale for relative specialty selection differences as a function of gender9-12.

Introduction

Despite increasing interest, methods to recognize and quantify gender differences in traditionally male-dominated academic fields such as radiation oncology are still needed. We previously published data comparing bibliometric measures estimating scholarly activity among U.S. radiation oncology faculty13, using the Hirsch index (h-index)14. The h-index is a number calculated as the Npapers published by an individual having at least Ncitations14. For example, an individual with 10 papers each having 10 or more citations would have a calculated h-index of 10. The h-index not only represents quantity of academic output, but also quality, as an individual with 10 papers each having only 1 citation would have an h-index of 1. The h-index, which has been widely accepted since its introduction in 2005, has been implemented by several fields in medicine and academics to evaluate and compare scholarly productivity. It is now easily accessible through programs such as SCOPUS (Elsevier BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and Google Scholar. When evaluating academic productivity among radiation oncology faculty between 1996 and 2007, we previously noted women comprised 28% of faculty. Additionally, we found women had a significantly lower h-index than men overall12. Although a full discussion of the merits and deficiencies of the h-index is beyond the scope of this discussion, the inherent dependence of the h-index on time is a concern when using this metric to compare individuals. Those who have been conducting research longer will have the opportunity to publish more papers, and the longer a paper has been in press, the more opportunities it has to be cited. The m-index is a correction of the h-index for time (m = h/n, where h is the h-index, and n is the number of years since an author's first paper was published). The m-index has been described as a good predictor of future publication success but can also be used to compare productivity of those with different career durations14. In his original work describing both the h and n indices, Dr. Hirsch describes an m-index of about 1 to indicate a successful scientist, at least as it pertains to data from the physics and chemists from which the original index was conceived14. Consequently, in order to more rigorously evaluate potential gender differences across the career timeline in the field of academic radiation oncology, we have sought to characterize not only h-index and m-index, but also number of publications, NIH-reported research funding, as well as academic rank and career trajectory between 1996 and 2012 for male and female academic radiation oncologists. We believe the issue of gender differences within the field of radiation oncology is an informative example of the position of women in the greater academic medical community, particularly in traditionally male dominated fields. We hope these data will also serve as hypothesis generating for future research in early-career interventions in radiation oncology as well as the academic community at large.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion Criteria

We compiled a comprehensive list of 82 domestic radiation oncology residency-training institutions using the Association of Residents in Radiation Oncology (ARRO) Directory. We then accessed publically available departmental websites between February 14, 2012 and February 28, 2012 to obtain a list of 1031 current faculty as listed by the individual institutions. We included all clinical faculty with M.D., D.O. or M.D./D.O.-Ph.D credentials. When available, we collected demographic parameters including gender and academic rank. Academic rank was classified as professor and or chair, associate professor, assistant professor and other, which comprised clinical instructor, non-tenure track faculty or unspecified. A single collector [EBH] imputed gender from extant data.

Data Collection

Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study, as the data we analyzed were all publically available. For each faculty member, we performed a custom search using a commercial database (SCOPUS, Elsevier BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). We created a custom search string using the Author Search function and examined the resulting documents in a concerted effort to select all publications attributable to an individual during the study period (1996-2012). We used the Citation Tracker function to generate the bibliographic database-derived total number total number of publications, total number of citations, and h-index for each individual. A single data collector [EBH] performed the searches in a pre-determined interval between February 28, 2012 and March 28, 2012 to minimize temporal bias in data collection. The bibliographic database outputs included total number of publications, total number of citations and h-index. Additionally, we recorded date of first publication and utilized this as an approximate surrogate for inception of academic career. We calculated career duration as the year of first publication subtracted from 2012, and we calculated the m-index by dividing h-index by the career duration. Finally, we accessed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORTER) website and used a custom search for each faculty using the Principal Investigator function for all fiscal years. We then exported the resulting project data into a spreadsheet for analysis and cross correlation with the aforementioned rank and bibliometric data, using a concatenation function.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis to calculate the median and confidence interval for the total number of publications, h-index, m-index, Ph.D. status and NIH funding of the individual radiation oncology faculty as well as temporal metrics such as career duration as estimated from the year of first publication to 2012, date of first publication and date of first NIH funding. We stratified data by gender and academic rank and performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine which variables were best associated with h-index. Included candidate covariates were academic rank, gender, Ph.D. status and career duration. As Shapiro-Wilk test showed the data were not distributed normally, we performed post hoc statistical analysis using Man-Whitney-U test for between group comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS-based statistical software package JMP (Version 7; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 82 U.S. academic radiation oncology departments were identified with a total of 1031 current faculty included for analysis. Of current faculty, 293 (28%) were women and 738 (72%) were men.

Academic position

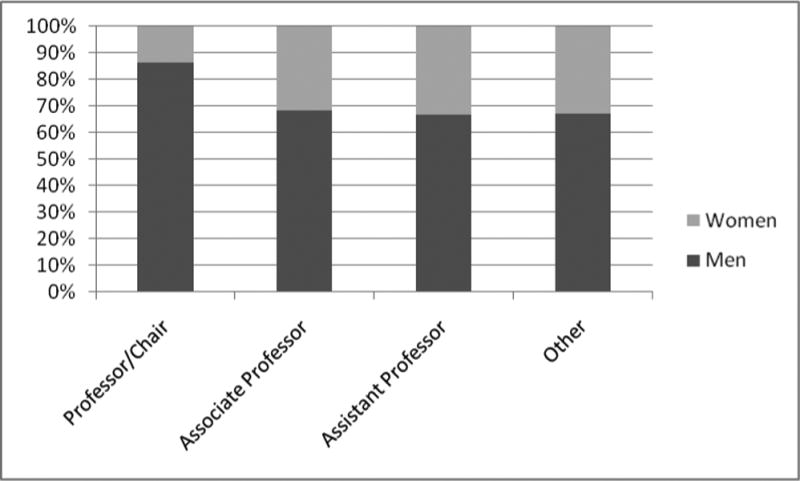

Overall, men were more likely to hold the rank of chair/professor with women not present in these higher academic echelons proportional to their presence in the field at large. Women comprised 30%, 33.3%, 32% and 13.9% of clinical instructor/other, assistant professors, associate professors and full professors/chairpersons, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Academic Position of Radiation Oncology Faculty by Gender.

Figure 1 provides the percentage of professor/chair, associate professor, assistant professor and other faculty (either clinical instructor, non-tenure track faculty, or unspecified) positions occupied by men and women for 1031 MD or MD/PhD faculty at 82 U.S. academic radiation oncology departments as determined by the accessing each individual's department website.

Number of publications, h-index and m-index

Men had a higher median number of publications overall; P<.001. The median number of publications was 26 (range 0-591) for men and 13 (range 0-306) for women. When stratified by academic rank, there were also significant differences between men and women in the same position, except for among assistant professors, where there was no difference. Among professor/chairpersons, the median number of publications was 116 (range 3-591) for men and 75.5 (range 7-258) for women; P=.008. Among Associate professors, the median number of publications was 38 (range 2-262) for men and 28 (range 2-306) for women; P=.037. Among faculty classified as other, the median number of publications was 10 (range 0-245) for men and 5.5 (range 0-53) for women; P=.012. Men also had a higher median h-index overall. The median h-index was 8 (range 0-59) for men and 5 (range 0-39) for women; P<.001. However, when stratified by academic rank, there was likewise no significant difference between men and women in the same position except for among faculty classified as other, in whom men had a median h-index of 4 (range 0-33) and women had a median h-index of 2 (0-17); P=.49. Finally, men also had a higher median m-index than women. The median m-index was 0.58 (range 0-3.23) for men and 0.47 (range 0-2.5) for women; P=.011. However, the m-index was no different when comparing men and women in the same academic rank (Table 1).

Table 1. Academic Productivity Metrics, Career Duration, and NIH Funding for Radiation Oncology Faculty by Gender and Academic Position.

| Gender | No (%) | No pubs (Median; range) | h-index (Median; range) | Career duration in Years (Median; range) | m-index (Median; range) | PhD No (%) | NIH funded No (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professor/Chair | 245 | ||||||

| Men | 211 (86.1) | 116; 3-591* | 23; 2-59 | 26; 5-54 | 1; 0.04-3.23 | 27 (13.2) | 84 (41.2) |

| Women | 34 (13.9) | 75.5; 7-258* | 20.5; 2-39 | 26; 7-42 | 0.74; 0.05-2.47 | 4 (11.8) | 12 (35.3) |

| Associate | 169 | ||||||

| Men | 115 (68) | 38; 2-262* | 12; 0-33 | 19; 2-52* | 0.54; 0-2.78 | 30 (25.6)* | 27 (23.1) |

| Women | 54 (32) | 28; 2-306* | 10; 1-35 | 16; 3-42* | 0.70; 0.03-2.33 | 5 (9.8)* | 11 (21.6) |

| Assistant | 411 | ||||||

| Men | 274 (66.7) | 9; 0-372 | 4; 0-40 | 10; 0-42* | 0.43; 0-1.92 | 52 (19.1)* | 24 (8.8) |

| Women | 137 (33.3) | 8; 0-104 | 3; 0-20 | 8; 0-46* | 0.43; 0-2.22 | 13 (9.6)* | 8 (5.9) |

| Other | 206 | ||||||

| Men | 138 (70) | 10; 0-245* | 4; 0-33* | 12.5; 0-45 | 0.36; 0-3 | 18 (12.4) | 8 (5.5) |

| Women | 68 (30) | 5.5; 0-53* | 2; 0-17* | 10; 0-33 | 0.29; 0-2.5 | 5 (6.9) | 1 (1.4) |

| Total | 1031 | ||||||

| Men | 738 (71.6) | 26; 0-591* | 8; 0-59* | 17; 0-54 | 0.58; 0-3.23* | 127 (17.2)* | 143 (19.3)* |

| Women | 293 (28.4) | 13; 0-306* | 5; 0-39* | 12; 0-46 | 0.47; 0-2.5* | 27 (9.2)* | 32 (10.9)* |

Table 1 provides the number of publications and h-index for 1031 MD or MD/PhD faculty at 82 U.S. academic radiation oncology departments as reported in SCOPUS (Elsevier BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The career duration was calculated by subtracting the year of first publication from 2012. M-index was calculated by dividing the h-index by career duration. Whether or not the individual had a PhD was determined from the individual's department website, and NIH funding status was determined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORTER) website.

P < .05

NIH funding

Overall, men were more likely to have received NIH funding than women (19.3% vs 10.9%; P<.05). However, once stratified by academic rank, there was no significant difference between men and women in the same position (Table 1).

Career Trajectory

Overall, male faculty had a longer median career duration than their female counterparts (17 (range 0-54) versus 12 (range 0-46) years, respectively; P<.05). Male assistant and associate professors also had longer median career durations than their female counterparts, 10 (range 0-42) versus 8 (range 0-46); P=.016, and 19 (range 2-52) versus 16 (range 3-42); P<0.001, respectively. On multivariate analysis, there were significant correlations between duration of career, gender, academic position and h-index (P<.01).

Highly Productive Women

After ranking all female radiation oncologists by h-index, we further analyzed the top 10% (No=30). The h-index of the most productive female faculty ranged from 19-39, median 26. The m-index ranged from 0.64 to 2.47, and the median was 1.02. Fifteen (50%) had received NIH funding, and they had career durations ranging from 9 to 42 years, median25.5 years. When examining the top 10% of men in our cohort after ranking by h-index (No=74), we found the h-index ranged from 30-59, and the median was 37. The m-index ranged from 0.83 to 3.23, and the median was 1.43. Thirty-three (44.6%) had received NIH funding, and they had career durations ranging from 11 to 41 years, median 26 years.

Discussion

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) reports that, in 2011, the percentage of female medical school applicants was 47%. Furthermore, the AAMC Women in U.S. Academic Medicine Statistics and Benchmarking Report for 2011-2012 reports the percentage of female residents increased from 39.2% in 2001 to 46.2% in 20111. Women made up 37% of academic faculty surveyed in 2011, but the distribution of women faculty was not evenly distributed among specialties. Obstetrics and gynecology had the highest percentage of female faculty in 2011-2012 (54%), and orthopedic surgery had the lowest (15%). Radiation oncology faculty numbers were not cited in this report, but the percentage of female radiation oncology residents remained stagnant at 32% from 2001 to 2011.

Our data suggest the percentage of female radiation oncology faculty did not change between 2007 (28%)13 and 2012 (28%). However, the total number of radiation oncology faculty did increase from 826 in 200713 to 1031 in 2012. Based on the 2009 ARRO directory, 33% of current residents in 2009 were women, so that means the number of women new hires at least remained reasonably proportionate to the number of women in the field. Additionally, the percentage of women in higher academic ranks likewise seems constant, with 33%, 26%, 23% and 17% of instructor, assistant professor, associate professor and full professor/chairperson positions, respectively, occupied by women as of 200713 and 30%, 33.3%, 32% and 13.9% of the same positions occupied by women in 2012. This suggests radiation oncology reasonably reflects academic medicine as a whole with women reported to occupy 53%, 43%, 32% and 20% of instructor, assistant professor, associate professor and full professor positions, respectively in 2011, compared to 47%, 36%, 24% and 13%, respectively in 20011.

There was an increase in the percentage of women members of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) to 27% in 2005. However, there still remains exceedingly low numbers of women chairpersons, ASTRO board members, past ASTRO presidents and ASTRO gold medal awardees15. This trend of unequal participation in academic leadership and productivity is not unique to radiation oncology. Studies have characterized gender differences across a wide variety of fields9-11, 16-19.

One factor considered in the hiring and promotion of academic faculty of both genders is publication productivity. Men published more papers than women in our cohort, and the difference persisted when comparing men and women in the professor/chair, associate professor, and other rankings. However, not all published papers make the same impact, which lead to the development of the h-index as an objective measure describing quality as well as quantity of publications to be used when considering promotion, acceptance into professional societies and allocation of funding resources14. There have been previous studies indicating a threshold h-index of 15 that exists as a breakpoint between junior and senior radiation oncology faculty13. Additionally, a more recent study identified a break point h-index of 10 that indicated likelihood of receiving NIH funding among academic radiologists20. It is thought that h-index is a better way to measure and compare publication productivity than simply evaluating the number of publications on a resume as it gives some insight into the relative impact and importance of the papers published. Our data suggest women have a lower h-index overall when compared to men, but there were fewer differences when comparing men and women in the same academic rank. This suggests that, although men may publish more papers than women within in given academic rank, women are publishing papers that generate sufficiently more citations as to have comparable h-indices. Additionally, as h-index is directly linked to career duration, the shorter career duration of women faculty compared to men likely contributes to this difference as well. In order to correct for the difference in career duration between men and women, we also calculated and compared the m-indices of men and women overall, and within each academic rank. As described above, the m index is calculated by dividing an individual's h-index by the years since their first publication. Overall, men had a higher m-index than women, which suggests that the difference observed in productivity is not due to career duration alone.Since male and female faculty had similar h- and m-indices when compared within the same academic rank, the overall differences are likely due to the larger proportion of men in senior level positions when compared to women.

It has been suggested that the importance of family and parenthood affects the trajectory of careers differently between men and women. One national survey-based study suggested women were more likely to perceive their institution as being “less family-friendly”21. A survey of surgeons reports that men are generally more likely than women to have children during residency and in their early career; however, most rely on their spouse for child care. Among men and women who had children, women were more likely to take leave from work (64 vs 12%). Additionally, although the reported working hours per week were similar for men and women in this study, women were more likely to spend over 20 hours per week on parenting and 80% of female respondents would consider a part time practice in order to spend more time with their families22, which would largely preclude them from entering a traditional academic tenure track . Thus, women wanting to start a family in residency in their early career are often at a disadvantage with regard to time away from work both during surrounding childbirth and because of child-rearing duties. One survey of surgeons suggested that pregnancies are more frequent and are tending to occur earlier during a woman's career, more than half of all women surgeons still delay childbearing until they complete training. A negative bias still exists on the part of co-residents and faculty towards becoming pregnant during training23, and this bias may follow female residents into their post-residency job search as they seek letters of recommendation or other forms of endorsement from individuals at their institution Additionally, when choosing an initial job, women with working spouses or with children may be more sensitive to geographic location, which may put them at a subtle disadvantage to men who can apply more broadly. Likewise, even during their careers, women may be more reluctant to move for a better opportunity. Although no formal study has been done to assess the effects of pregnancy and childrearing on the career trajectories of radiation oncologists, these are some mechanisms by which competing commitments to family can affect women even in traditionally “family-friendly” specialties such as dermatology, radiology and radiation oncology with more predictable hours and less overnight call. The effects may even be more subtle than that, with women working similar hours as men on the clock and spending more time on childrearing duties, they may be less likely to take on committee appointments, research projects or other responsibilities that would require an additional time commitment.

While some suggest the gender inequality in academic medicine, particularly among physician-scientists, is due to a preference of women to participate in clinical or teaching duties over research24, a more recent study demonstrated female K-award recipients were significantly less likely to receive R01 funding than their male counterparts, suggesting gender inequality exists even among those with a similar commitment to research4. A survey of radiology faculty reported similar rates of publication between men and women but with women receiving significantly less research funding. They reported men and women spent a similar amount of time performing clinical, teaching and research duties, but women were less likely to hold tenured positions, and were less likely to hold chair or vice-chair positions8. Additionally, as of 2011, only 15.9% of all editors-in-chief and only 17.5% of all editorial board members of the 60 major medical journals were women24. Women were also much less likely to hold leadership positions in professional societies25.

There is much interest in the role of mentoring in career advancement for academic physicians. There have been survey studies seeking to evaluate the role of mentorship at multiple steps in the so-called “pipeline” of future academic faculty. A systematic review published of 39 self-report surveys, one case control study and one cohort study reported less than half of all medical students and less than 20% of faculty had a mentor. They noted women perceived having greater difficulty finding a mentor than men and perceived a mentor of the same gender would be more understanding. Additionally, they emphasized the importance of mentorship for personal development, career guidance, career choice, including publication rates and grant success26. One survey of medical students noted female students were significantly more likely to choose surgery if they came from a school with more female faculty27. A case control study was performed in academic gynecologic oncology departments across 32 fellowship training institutions divided into high and low producing institutions. The higher producing group reported greater ease in identifying a mentor, a formal research mentor pairing program, as well as regularly scheduled research progress and feedback reports28. In traditionally male dominated fields such as radiation oncology where women comprise as minority of full professors, it may be particularly challenging for female faculty early in their careers to find senior mentors if a female mentor is desired.

Additionally, there is increasing attention being focused at the department, institution and national level on promoting women in leadership. For example, MD Anderson Cancer Center created an office in 2007 for Women Faculty Programs29. On the national level, the Hedwig van Ameringen Executive Institute for Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) Program for Women was established in 1995. Women completing this program appear to have significant benefits in terms of career progression30. It stands to reason that mentorship is vital for career advancement, and as more women enter the field and serve as mentors, we may see a positive feedback effect on the number of successful women academicians and a narrowing of the observed gender gap.

Regarding this study's strengths, the cohort examined includes all radiation oncology faculty from domestic academic institutions, yielding a large, comprehensive group of subjects. To increase homogeneity, productivity metrics including h-index were obtained by a single person (EBH) from a single database (SCOPUS). This database and its bibliometric citation software employed citation analysis back to 1996 to allow a thorough evaluation of the h-index of the faculty included in this study. There are several commercially and publically available databases commonly used to obtain productivity metrics such as the h-index. It is beyond the scope of this discussion to compare and contrast the pros and cons of all the options31, but we chose to use SCOPUS over the publically available Google Scholar due to its full Medline coverage and its author discrimination tools to help insure publications were being ascribed to the correct individual. Google Scholar also incorporates academic websites, pre-prints, and conference abstracts, which we did not desire for this analysis.

Among study limitations, elapsed time between publication and h-index data collection and publication is problematic. SCOPUS allows for collection of calculated h-index as well as publication and citation numbers; however, these estimates are subject to dynamic change and are updated frequently. Additionally, SCOPUS only includes articles published in 1996 or later when calculating the h-index. Therefore, those faculty members in the field for decades who were prolific in their early careers will have artificially low h-indices when compared to their total number of publications and citations.

The largest potential source for error inherent in the use of SCOPUS for data collection is authors' publications mistakenly being ascribed to another individual with the same or a very similar name or having publications mistakenly ascribed to them. We attempted to control for this by manually checking each publication ascribed to each faculty member as well as combining publications for authors who might have multiple entries in SCOPUS, due to having different institutional affiliations over the years.

Another related source of error is authors publishing under different names. This could particularly occur for women when changing a name after marriage or divorce. The number of publications and h-index may be artificially lower for female faculty for this reason. A similar problem that could occur in either gender is including a middle initial and/or suffix that was previously omitted, which could result in an incomplete list of publications generated by SCOPUS for an author search. As the practice of changing names due to marital events is a unique issue for women, we evaluated the rate of name changes in female radiation oncology faculty. We did this by performing a Google search for each female faculty using first and last name as well as current institution. When available, we accessed their curriculum vitae and noted whether or not they have previously published under a different name. We accessed curriculum vitae for a randomly selected 33% (n = 97) of the 293 female faculty included in our sample. Of those, we found 12 (12.4%) women had changed their name during their publication career. Of those who published under more than one name, we performed additional author searches in SCOPUS and merged the total number of publications attributable to a woman who published under more than one name. The h-index was impacted by name change in only 8 (8.2%) of those reviewed.

Conclusions

The determinants of a successful career in academic radiation oncology, as in other fields of academic medicine, are certainly multi-factorial. However, our data show a clear gender association with women having a lower probability of becoming senior radiation oncology faculty. It is encouraging that women who achieve senior faculty status have a mean h-index, m-index, number of publications, and NIH funding comparable to their male counterparts. These trends observed in the traditionally male-dominated, research-heavy field of radiation oncology can better inform discussions regarding gender imbalances in academic medicine as a whole. These results also suggest early career development and mentorship of female faculty may help to further diversify academic medicine and narrow productivity and career trajectory disparities. We do not suggest a system of quotas so that women are arbitrarily represented among senior faculty ranks equal to their proportion in the field of radiation oncology, but we do hope to spur discussion and further systematic action so that women with aspirations for senior faculty or leadership career paths have equal opportunity to attain them. The effect of mentorship on academic productivity, in particular, has spurred much interest and is the topic of upcoming studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: There were no sources of funding for this project.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this project not required by the institutional review board due to the publically available nature of the data analyzed.

Previous presentations: An earlier version of this paper was presented in part at the October 2012 annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology, Boston, MA.

Contributor Information

Dr. Emma B. Holliday, Second year radiation oncology resident at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas

Dr. Reshma Jagsi, Associate professor of radiation oncology and Associate Chair for Faculty Affairs in the Department of Radiation Oncology at The University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Dr. Lynn D. Wilson, Professor of therapeutic radiology and of dermatology as well as vice chairman, clinical director and residency training program director of therapeutic radiology at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut

Dr. Mehee Choi, Fifth year radiation oncology resident at Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois

Dr. Charles R. Thomas, Jr, Professor and chair of Radiation Medicine at Oregon Health & Science University Knight Cancer Institute in Portland, Oregon

Dr. Clifton. D. Fuller, Assistant professor of Radiation Oncology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. He has joint faculty appointment in the department of Radiation Medicine at Oregon Health & Science University Knight Cancer Institute in Portland, Oregon

References

- 1.Jolliff L, Leadley J, Coakley E, Sloane RA. Women in U.S. Academic Medicine and Science: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2011-2012. [Accessed 03/13/2013]; https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Women%20in%20U%20S%20%20Academic%20Medicine%20Statistics%20and%20Benchmarking%20Report%202011-20123.pdf.

- 2.Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey C, et al. The “gender gap” in authorship of academic medical literature – a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):281–287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, et al. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307(22):2410–2417. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, et al. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:804–811. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ley TJ, Hamilton BH. The gender gap in NIH grant applications. Science. 2008;322:1472–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.1165878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jagsi R, DeCastro R, Griffith KA, et al. Similarities and differences in the career trajectories of male and female career development award recipients. Acad Med. 2011;86:1415–1421. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182305aa6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shea JA, Stern DT, Klotman PE, et al. Career development of physician scientists: a survey of leaders in academic medicine. Am J Med. 2011;124(8):779–787. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J. Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students. PNAS 2012. 2012 Sep 17; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vydareny KH, Waldrop SM, Jackson JP, et al. Career advancement of men and women in academic radiology: is the playing field level? Acad Radiol. 2000;7:493–401. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumayer L, Kaiser S, Anderson K, et al. Perceptions of women medical students and their influence on career choice. Am J Surg. 2002;183(2):146–50. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson HC, Redfern N. Why do women reject surgical careers? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82(9 Suppl):290–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldwin K, Namdari S, Bowers A, et al. Factors affecting interest in orthopedics among female medical students: a prospective analysis. Orthopedics. 2001;34(12):e919–932. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20111021-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi M, Fuller CD, Thomas CR. Estimation of citation-based scholarly activity among radiation oncology faculty at domestic residency-training institutions: 1996-2007. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 2009;74(1):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16569–16572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagsi R, Tarbell NJ. Women in radiation oncology: time to break through the glass ceiling. J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3(12):901–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holden C. General contentment masks gender gap in first AAAS salary and job survey. Science. 2001;294(5541):393–411. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5541.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidhu R, Rajashekhar P, Lavin VL, et al. The gender imbalance in academic medicine: a study of female authorship in the United Kingdom. J R Soc Med. 2009;102(8):337–342. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.080378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guarin-Nieto E, Krugman SD. Gender disparity in women's health training at a family medicine residency program. Fam Med. 2010;42(2):100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhuge Y, Kaufman J, Simeone DM, et al. Is there still a glass ceiling for women in academic surgery? Ann Surg. 2011;253(4):637–643. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182111120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rezek I, McDonald RJ, Kallmes DF. Is the h-index predictive of greater NIH funding success among academic radiologists? Acad Radiol. 2011;18:1137–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pololi LH, Civian JT, Brennan RT, et al. Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2207-1. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayer KL, Ho HS, Goodnight JE., Jr Childbearing and childcare in surgery. Arch Surg. 2001;136(6):649–655. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner PT, Lumpkins K, Gabre J, et al. Pregnancy among women surgeons: trends over time. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):474–479. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amrein K, Langmann A, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, et al. Women underrepresented on editorial boards of 60 major medical journals. Gend Med. 2011;8(6):378–87. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morton MJ, Sonnad SS. Women on professional society and journal editorial boards. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(7):764–771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambujak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103–1115. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guelich JM, Singer BH, Castro MC. A gender gap in the next generation of physician-scientists: medical student interest and participation in research. J Investig Med. 2002;50:412–418. doi: 10.1136/jim-50-06-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen JG, Sherman AE, Kiet TK, et al. Characteristics of success in mentoring and research productivity – a case-control study of academic centers. Gynecologic Oncology. 2012;125:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Travis E, Wharton R, Simsek M, et al. Optimizing the advancement and recruitment of women faculty and leaders at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Poster presented at the 2008 AAMC Faculty Affairs Professional Development Conference; August 2008; [Accessed online 03/13/2013]. http://www.mdanderson.org/education-and-research/departments-programs-and-labs/programs-centers-institutes/women-faculty-programs/publications-and-reports/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dannels SA, Yamagata H, McDade SA, et al. Evaluating a leadership program: a comparative, longitudinal study to assess the impact of the Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) Program for Women. Academic Medicine. 2008;83(5):488–495. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816be551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bar-Ilan J. Which h-index? – A comparison of WoS, SCOPUS and Google Scholar. Scientometrics. 2008;74(2):257–271. [Google Scholar]